User login

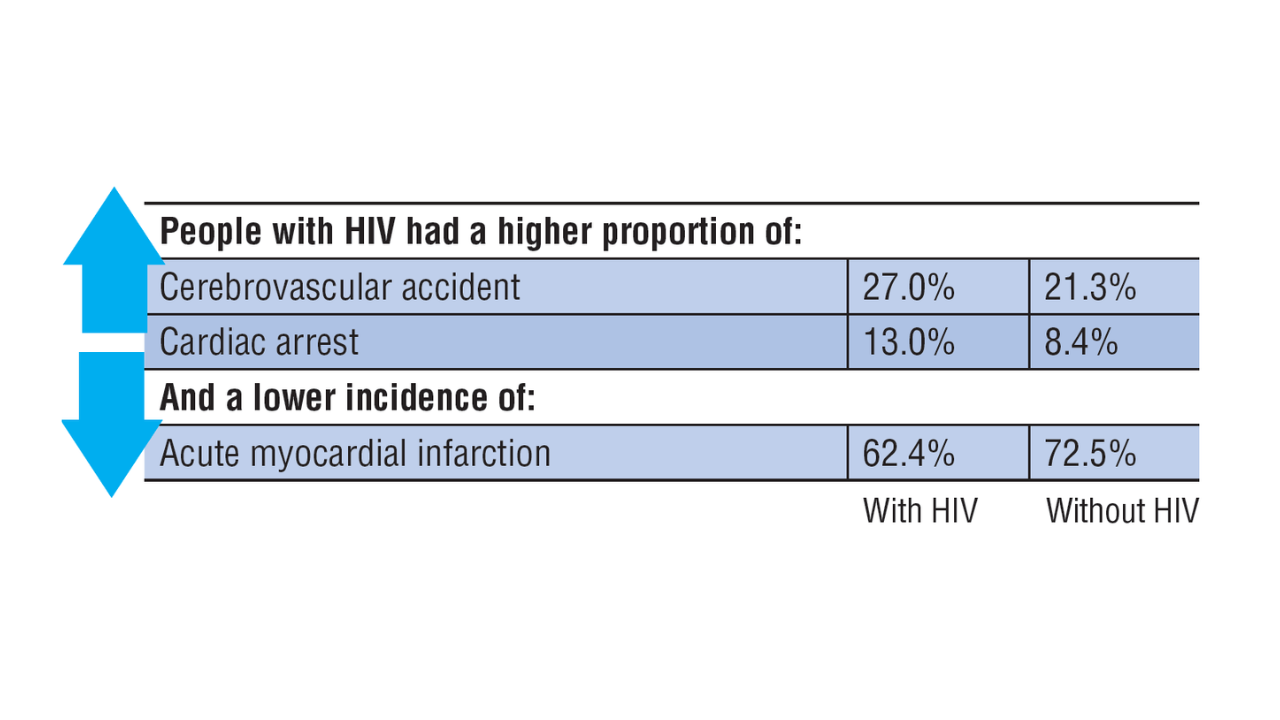

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

- Varley CD, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(6):1571-1579. doi:10.1093/cid/

ciae025 Hicks WL, et al. HIV Med. 2025;26(2):218-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.13724

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Data Trends 2025: HIV

Pedunculated Pink Papule on the Nose

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

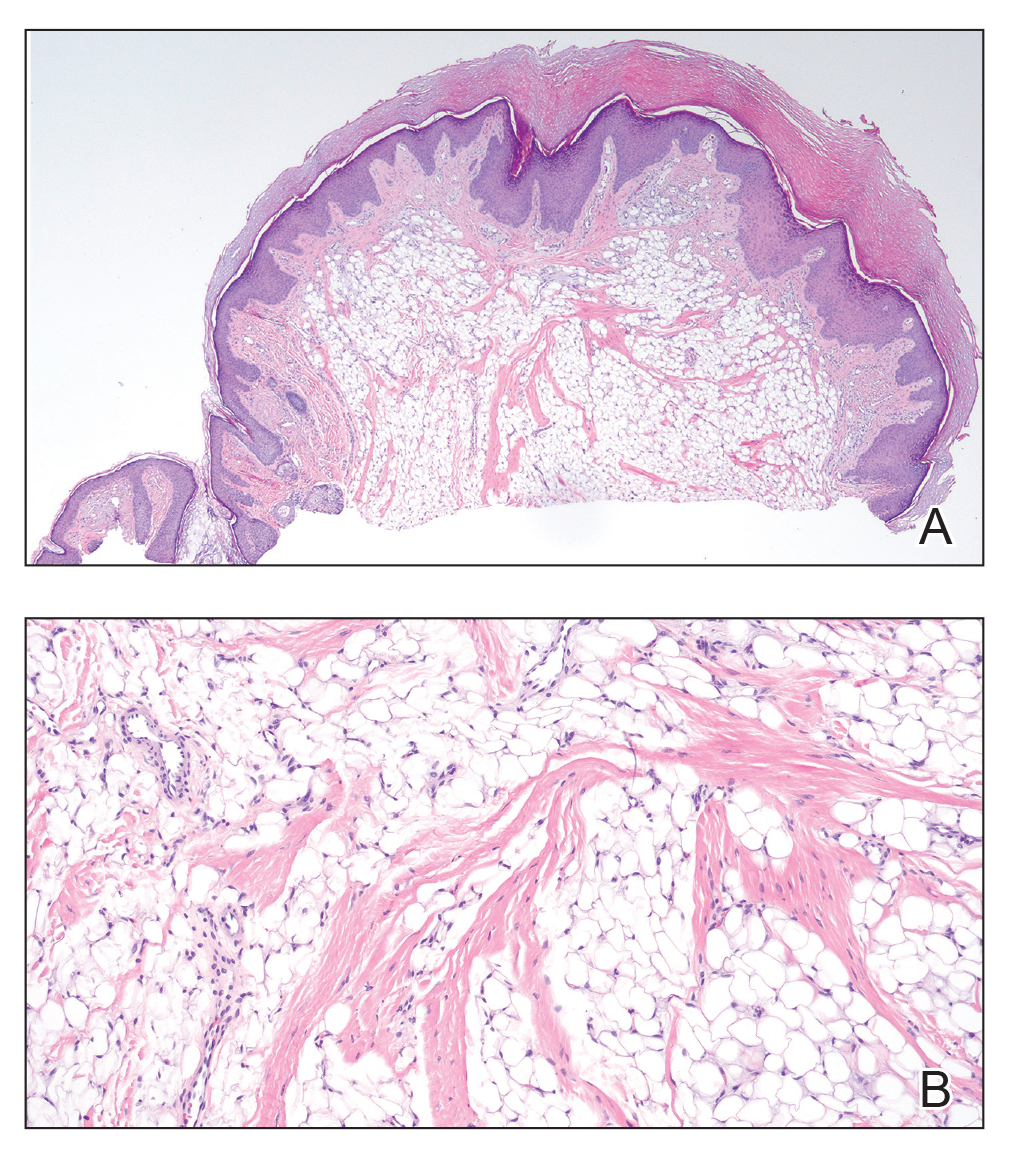

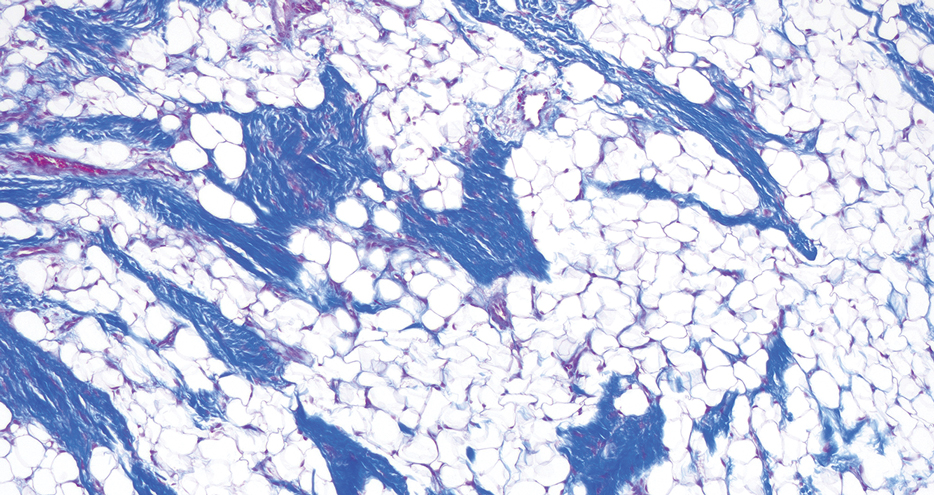

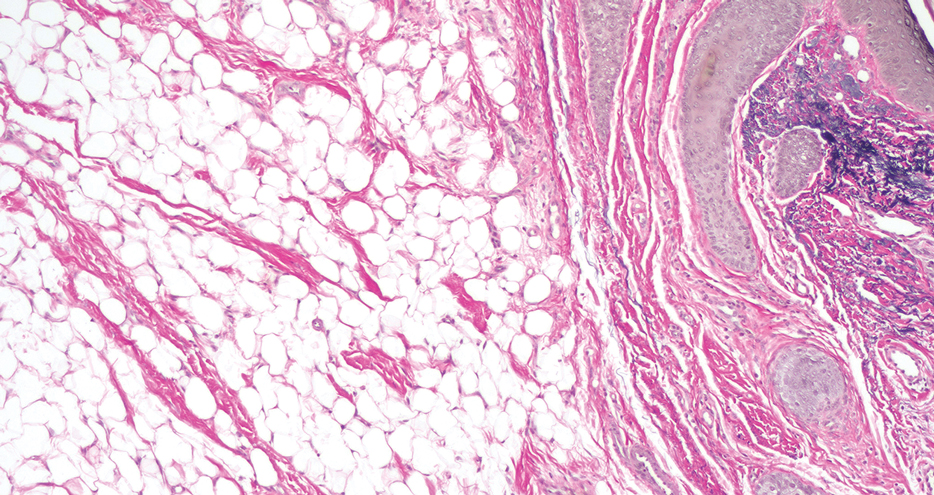

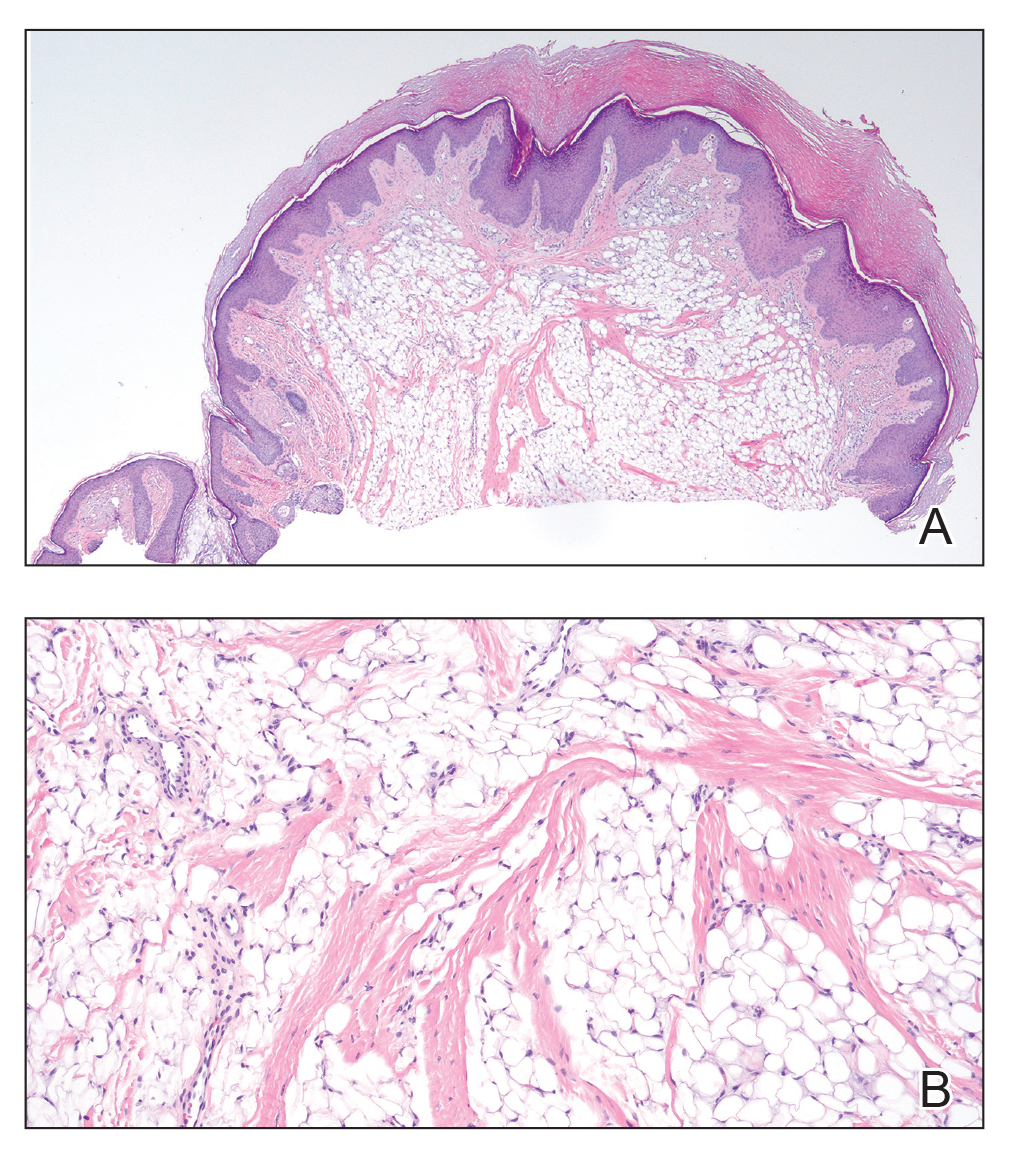

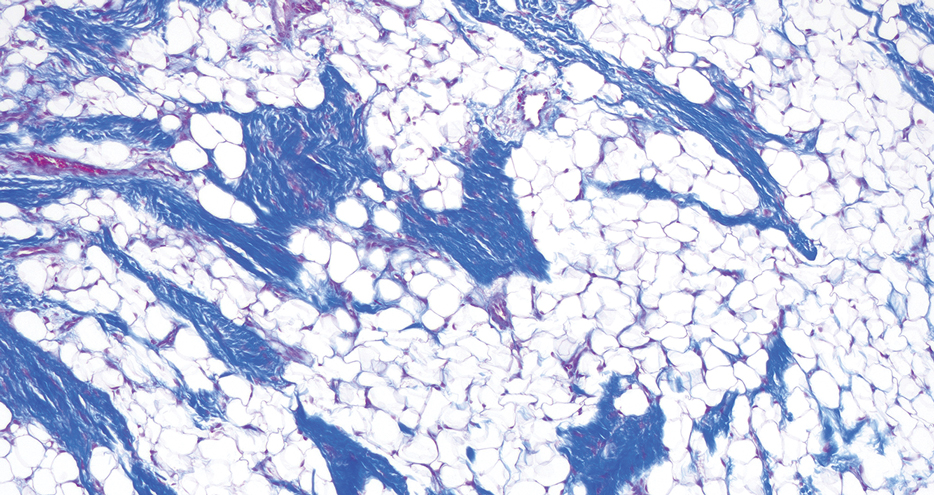

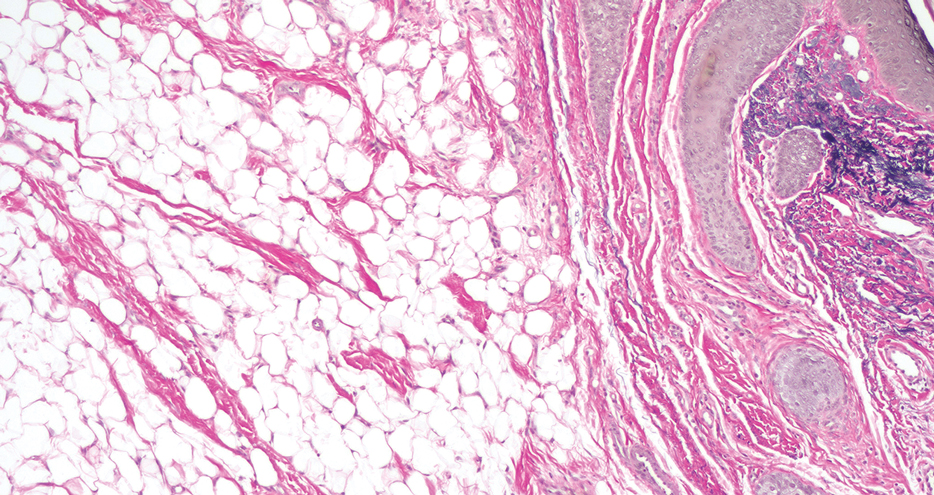

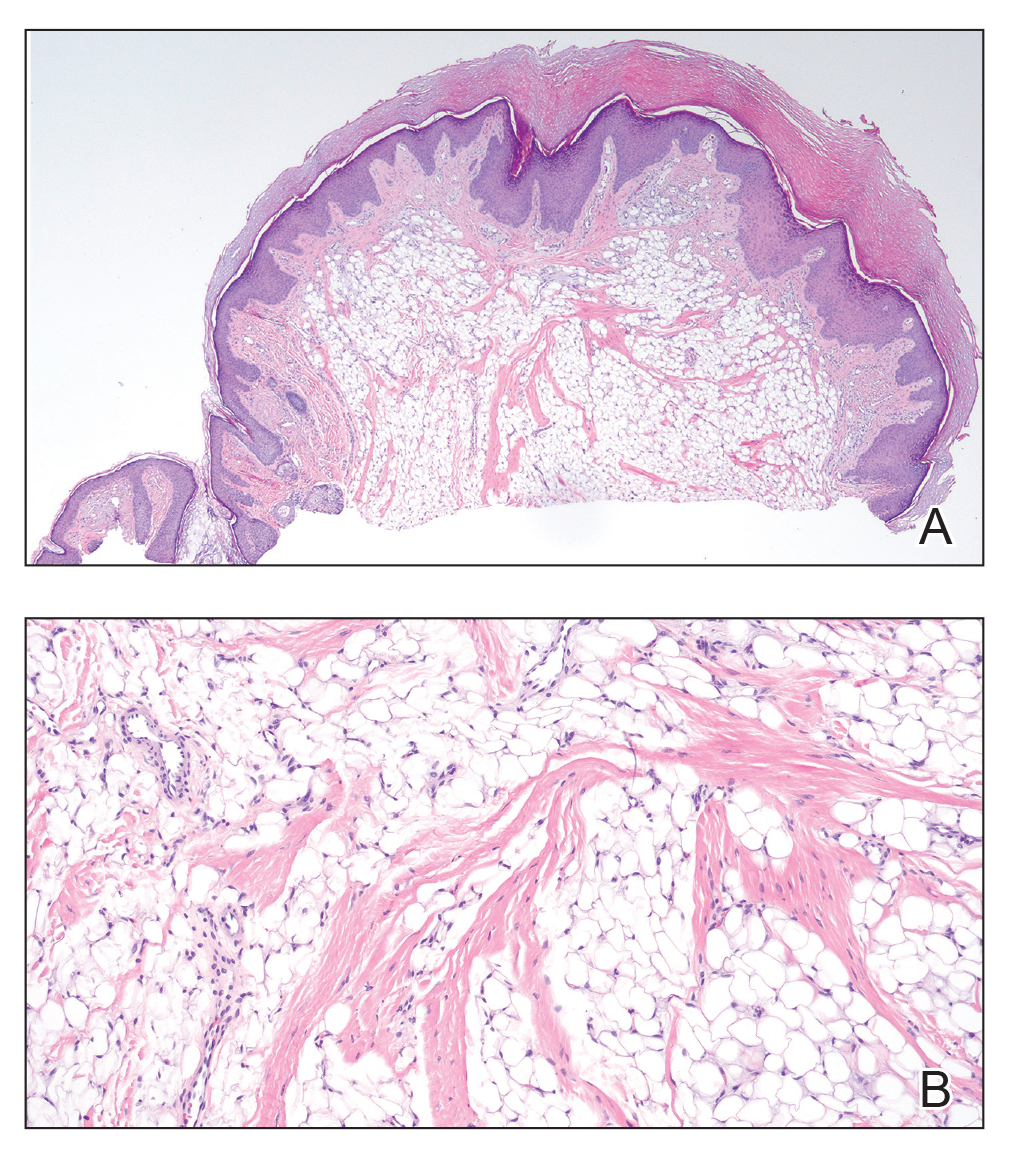

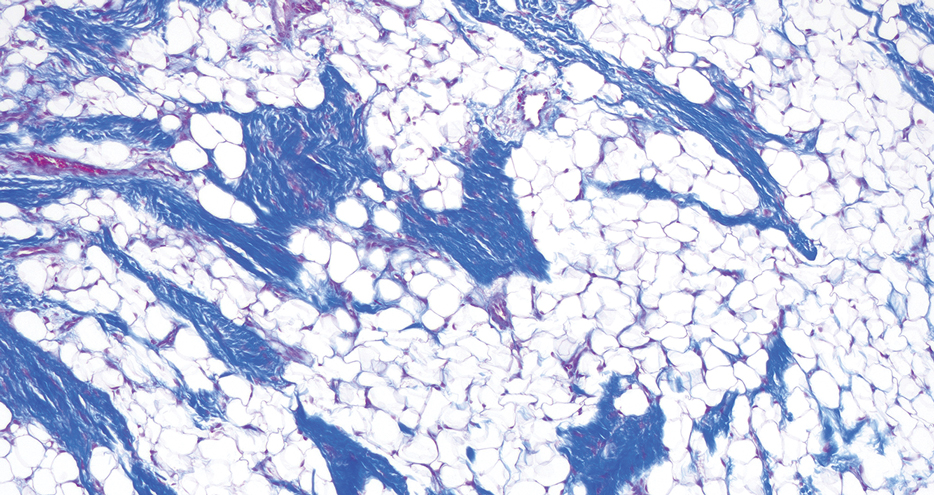

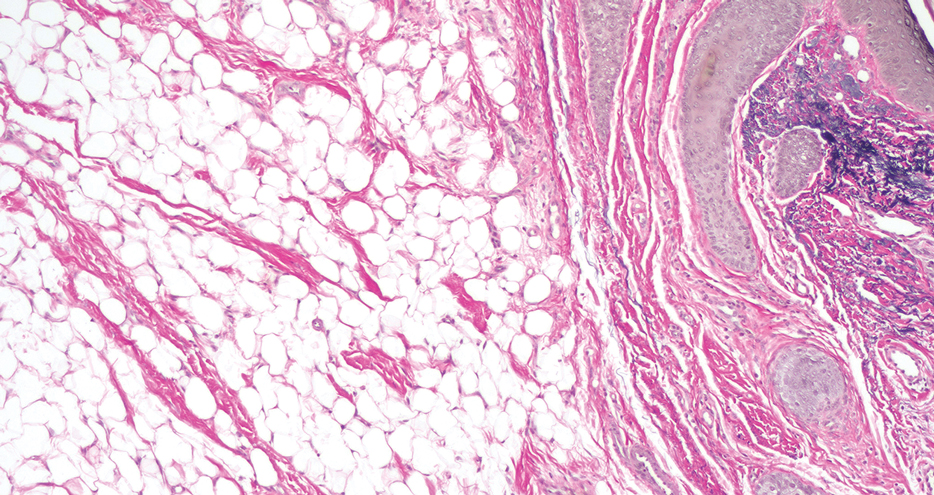

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.

- Han XC, Zheng LQ, Shang XL. Dendritic fibromyxolipoma on the nasal tip in an old patient. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7064-7067.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pedunculated Lipofibroma

Histopathology confirmed a pedunculated/polypoid lesion with intradermal lobules of adipocytes/mature adipose tissue admixed with connective tissue bundles and vascular ectasias. Overlying epidermal acanthosis with slight papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis was present (Figure 1). Masson trichrome staining highlighted admixed collagen bundles (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson staining showed marked reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). Immunostaining was negative for smooth muscle actin and desmin. A diagnosis of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose was made based on both clinical and histopathologic findings.

Pedunculated lipofibroma (or solitary lipofibroma) is the solitary form of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS).7 First described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle1 in 1921, NLCS is an uncommon benign hamartomatous cutaneous lesion/connective tissue nevus that also has a classic multiple form.1-13 The etiology of NLCS remains unclear, but several theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including deposition of adipocytes secondary to degenerative changes in dermal connective tissue, focal/local heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and derivation from differentiating lipoblasts (preadipose tissue) originating from precursor vascular or perivascular cells.2-13

Pedunculated lipofibroma usually develops during the third to sixth decades of life and manifests as a single cutaneous lesion with a smooth surface, often on a non–pelvic girdle location.7-13 No particular predilection sites are noted, with lesions reported on the arm, axilla, back, upper thigh, knee, and sole.5,12 There are rare reports of this type of NLCS on the ear, scalp, forehead, or eyelid.7-11

In the classic form of NLCS, multiple cutaneous lesions are present at birth or develop within the first 2 to 3 decades of life.2-6 Lesions consist of soft, nontender, pedunculated, flesh-colored or yellowish papules and nodules with a verrucoid or cerebriform surface that may later coalesce to form plaques.2-6 Predilection sites include the pelvic girdle, buttocks, sacral and coccygeal regions, and upper posterior thighs, with a linear or zosteriform pattern of distribution.2-6 Rarely, the classic form can arise in elderly patients and/or at an atypical anatomic location (eg, clitoris,3 shoulder,5 thorax,5 abdomen5) and can demonstrate extension of lesions across the midline.4 Rare cases of classic NLCS on the scalp2 and face3-6 have been reported, including lesions localized to the nose3 and chin4 and others extending from the right mandible to the neck5 and right lower lip to the submandibular/posteriorateral cervical region.6 In some cases, lesions clinically resemble plane xanthoma4 and localized scleroderma.6

Adotama et al13 proposed a set of clinical features to differentiate classic NLCS, pedunculated lipofibroma (solitary NLCS), and fibroepithelial polyp with adipocytes (distinguished by their furrowed surface, hyperpigmentation, and anatomic predilection for the neck and axilla). Lesions are asymptomatic in both forms of NLCS.2-13 Family history or predominant sex involvement have not been reported in either clinical type.2-13 Reported associations with NLCS include a number of endocrinologic conditions including diabetes.7 Other coexisting skin findings can include café-au-lait macules, leukodermic (white) spots, overlying hypertrichosis, comedolike alterations, angiokeratoma, hemangioma, and folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma.4 None of these were evident in our patient.

Lesions from both types of NLCS are indistinguishable on histopathology, characterized by the presence of a central core of ectopic mature adipocytes in the papillary/reticular dermis.2-13 Additional light microscopic features (some seen in our case) have been described, including thickened collagen bundles, reduction of elastic fibers, increased numbers of fibroblasts and/or mast cells, increased (small-vessel) vascularity, focal mucin deposition/myxoid degeneration, a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, attenuation of adnexal structures, and abnormalities of the epidermis (eg, surface ulceration).2-13

Prior to biopsy, the differential diagnosis in our patient included angiofibroma, pyogenic granuloma, and basal cell carcinoma given the exophytic, pink, papular appearance of the lesion; however, the histopathologic differential diagnosis included angiofibroma, angiomyolipoma, lymphangioma, nevus sebaceus, and spindle cell lipoma (SCL). In angiofibroma, a dermal proliferation of stellate fibroblasts, dilated blood vessels, and collagenous stroma are seen. Cutaneous angiomyolipoma demonstrates smooth muscle bundles in addition to thickened blood vessels and variable proportions of mature adipocytes. Lymphangioma is characterized by dilated lymph channels lined by flat endothelial cells. Nevus sebaceus shows superficial immature and abnormally formed pilosebaceous units, with epidermal papillomatosis.

Rare cases of SCL on the nose have been described.14 Similar to pedunculated lipofibroma, reported examples demonstrate mature univacuolar adipocytes with thick collagen fibers and bland uniform spindle cells. Unlike the lesion seen in our patient, nasal SCL may be clinically mobile and typically is localized to the subcutaneous tissue, although dermal tumors also occur.14 Variably reported histopathologic findings in nasal SCL include circumscription/encapsulation, spindle cells arranged in short fascicles with nuclear palisading, a myxoid/mucinous interstitial matrix, and/or multinucleated giant cells—all light microscopic features that were not identified in our case; however, variable proportions of adipocytic, fibrous, and myxoid components among reported examples of SCL on the nose14 can make distinction from pedunculated lipofibroma difficult, as both are benign lipomatous tumor variants.

Clinically, pedunculated lipofibroma may be confused with more common benign cutaneous lesions and must be distinguished from other fibrolipomatous lesions on the nose. Specifically, the differential diagnosis includes benign cutaneous papillomas such as acrochordon, angiofibroma, melanocytic nevi, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceus, lymphangioma, and eccrine poroma.7-13 These all can be readily excluded on histopathology. Pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose, as in our patient, must be distinguished from fibrolipoma15 and dendritic myxofibrolipoma.16 Fibrolipoma is a subcutaneous proliferation of mature adipose tissue and fibrous tissue and comprises 1.6% of all facial lipomas reported worldwide.15 Dendritic myxofibrolipoma is a recently described benign soft-tissue tumor characterized by an admixture of mature adipose tissue, spindle and stellate cells, and an abundant myxoid stroma with prominent collagenization.16

Treatment of pedunculated lipofibroma on the nose is not indicated except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple surgical excision would be considered satisfactory. Following biopsy, no further treatment was pursued in our patient.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.

- Han XC, Zheng LQ, Shang XL. Dendritic fibromyxolipoma on the nasal tip in an old patient. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7064-7067.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Uber einen naevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linken Glutaalgegend. Arch Derm Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Chanoki M, Isukos S, Suzuki S, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of the scalp. Cutis. 1989;43:143-144.

- Sáez Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Martin M, Carnerero A, et al. Naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the nose. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:751-752.

- Hassab-El-Naby HMM, Rageh MA. Adult-onset nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis mimicking plane xanthoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:10-11.

- Park HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the face. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:435-437.

- Ioannidou DJ, Stefanidou MP, Panayiotides JG, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (Hoffman-Zurhelle) with localized scleroderma like appearance. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:54-57.

- Nogita T, Wong TY, Hidano A, et al. Pedunculated lipofibroma. a clinicopathologic study of thirty-two cases supporting a simplified nomenclature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 pt 1):235-240.

- Sawada Y. Solitary nevus lipomatosus superficialis on the forehead. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16:356-358.

- Knoth W. Uber Naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis Hoffmann-Zurhelle und uber Naevus naevocellularis partim lipomatodes. Dermatologica. 1962;125:161.

- Weitzner S. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis of scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:540-542.

- Kaw P, Carlson A, Meyer DR. Nevus lipomatosus (pedunculated lipofibroma) of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:74-76.

- Vano-Galvan S, Moreno C, Vano-Galvan E, et al. Solitary naevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis on the sole. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:353-354.

- Adotama P, Hutson SD, Rieder EA, et al. Revisiting solitary pedunculated lipofibromas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156:954-957.

- Kubin ME, Lantto U, Lindgren O, et al. A rare, recurrent spindle cell lipoma of the nose. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00571.

- Jung SN, Shin JW, Kwon H, et al. Fibrolipoma of the tip of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:555-556.

- Han XC, Zheng LQ, Shang XL. Dendritic fibromyxolipoma on the nasal tip in an old patient. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7064-7067.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a 6-mm, firm, pink, nonulcerated, nonmobile papule on the right nasal side wall of 1 year’s duration. It had grown slowly and was asymptomatic with no tenderness or bleeding. No other skin lesions were noted on physical examination, and her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. A shave biopsy was performed.

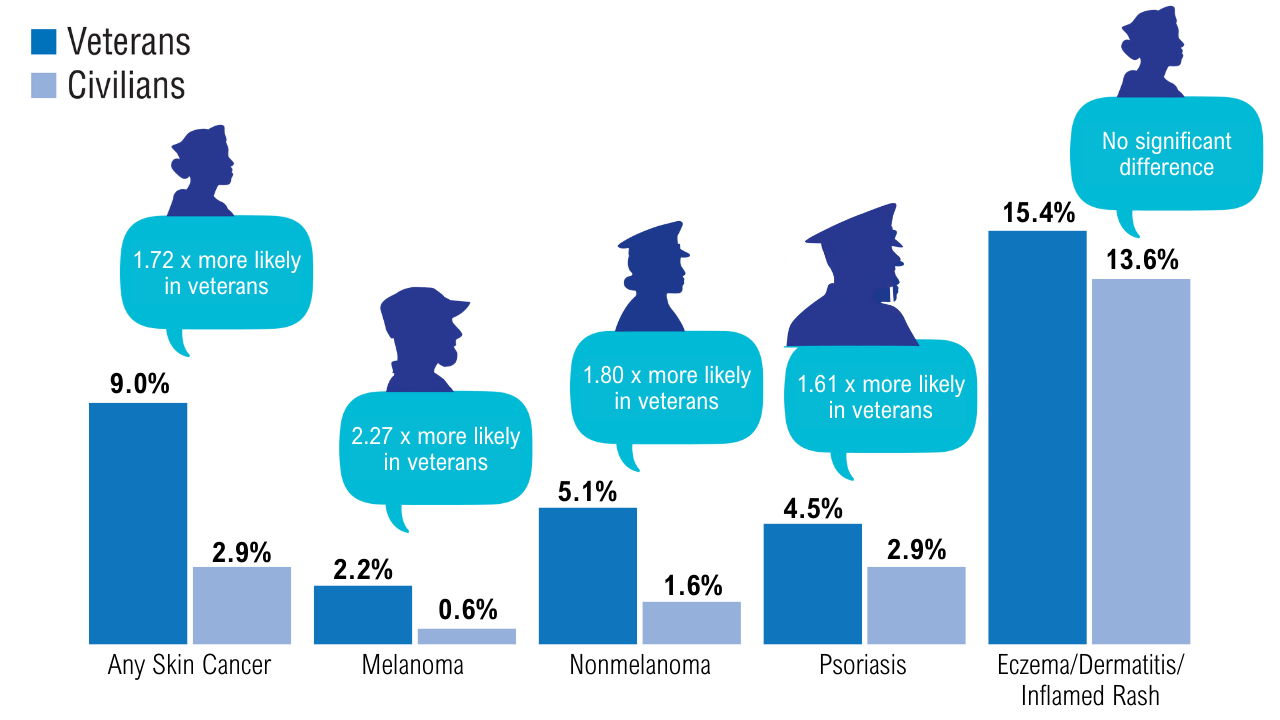

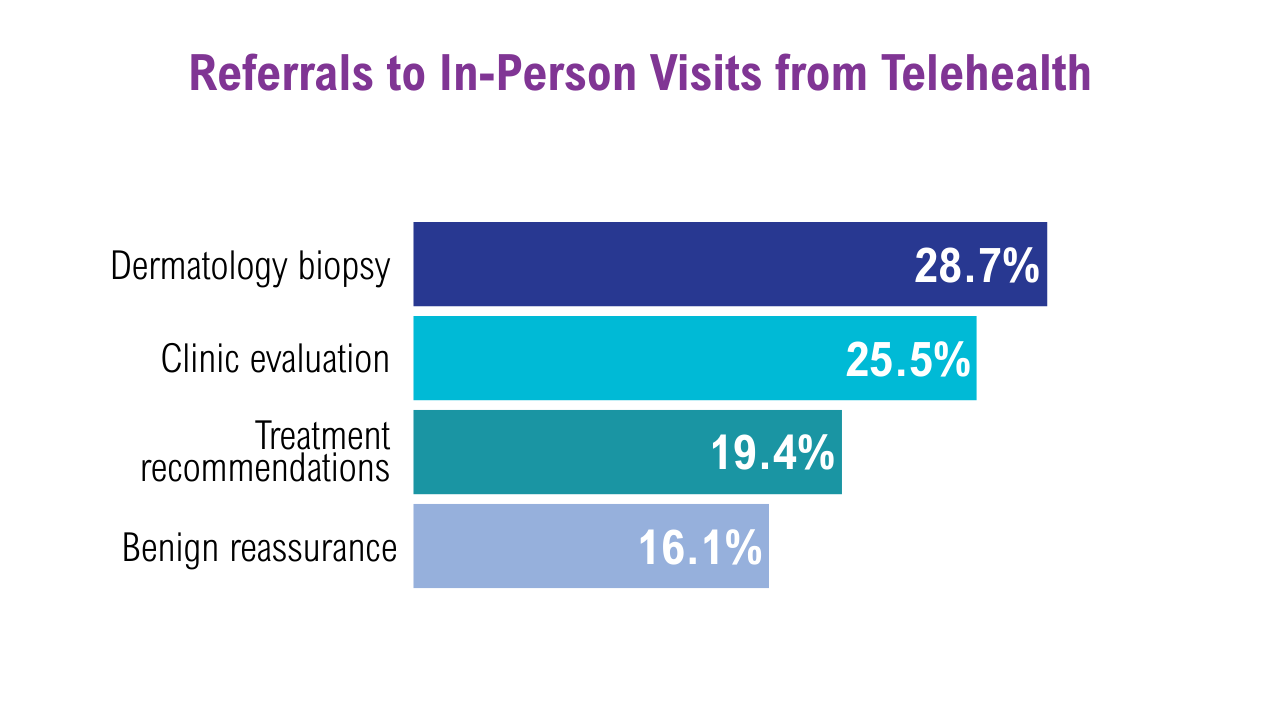

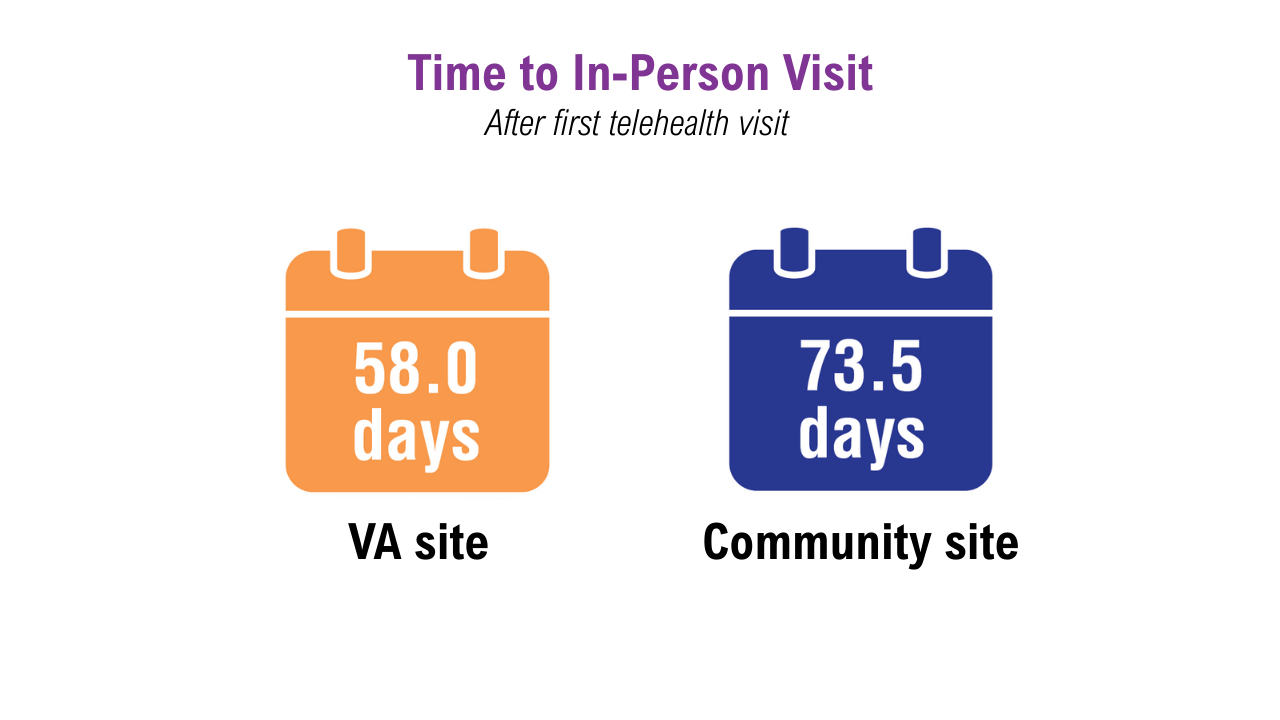

Data Trends 2025: Dermatology

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Rezaei SJ, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol. 2024.3043

- Singal A, Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2023;55(2):2267425. doi:10.1080/07853890.2023.2267425

- Reese R, et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2024;35(1):2402912. doi:10.1080/09546634.2024.2402912

- Wallace MM, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(5):1411-1417. doi:10.1089/tmj.2022.0528

- Russell A, et al. Mil Med. 2024;189(11-12):e2374-e2381. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae139

Salahuddin T, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(7):e862-e864. doi:10.1111/jdv.18964

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Rezaei SJ, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol. 2024.3043

- Singal A, Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2023;55(2):2267425. doi:10.1080/07853890.2023.2267425

- Reese R, et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2024;35(1):2402912. doi:10.1080/09546634.2024.2402912

- Wallace MM, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(5):1411-1417. doi:10.1089/tmj.2022.0528

- Russell A, et al. Mil Med. 2024;189(11-12):e2374-e2381. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae139

Salahuddin T, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(7):e862-e864. doi:10.1111/jdv.18964

- Rezaei SJ, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160(10):1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol. 2024.3043

- Singal A, Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2023;55(2):2267425. doi:10.1080/07853890.2023.2267425

- Reese R, et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2024;35(1):2402912. doi:10.1080/09546634.2024.2402912

- Wallace MM, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(5):1411-1417. doi:10.1089/tmj.2022.0528

- Russell A, et al. Mil Med. 2024;189(11-12):e2374-e2381. doi:10.1093/milmed/usae139

Salahuddin T, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(7):e862-e864. doi:10.1111/jdv.18964

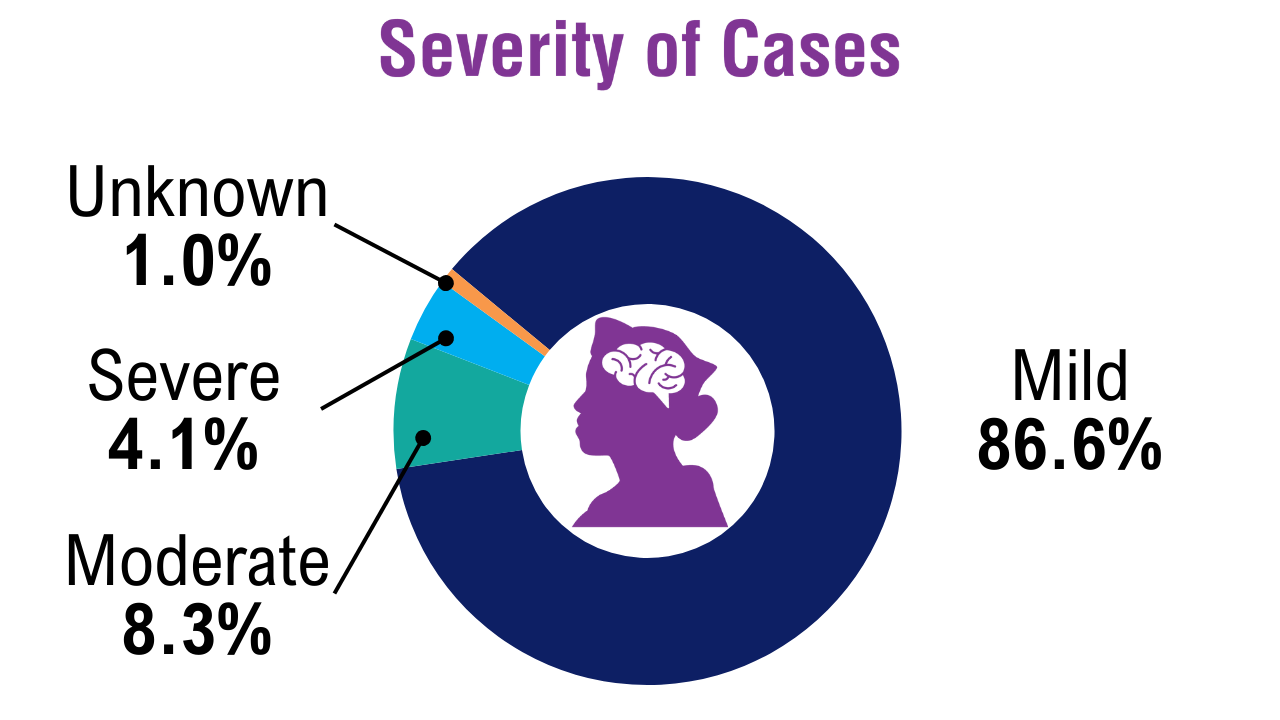

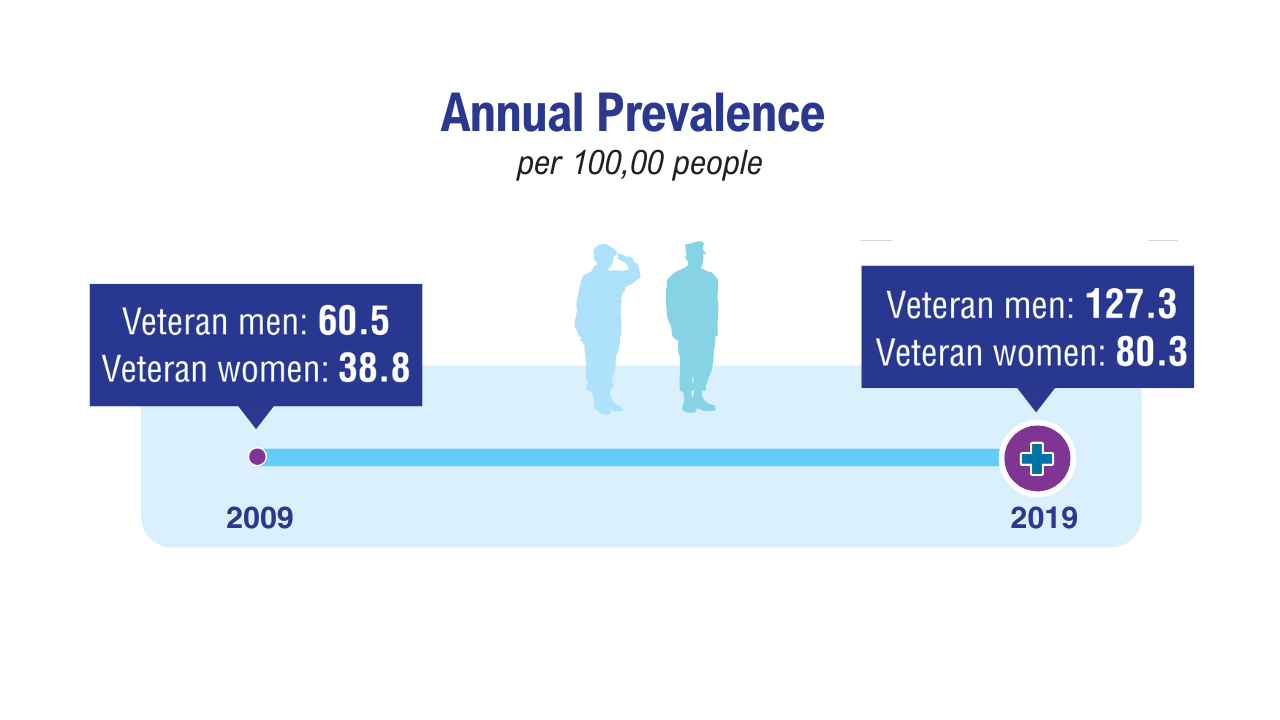

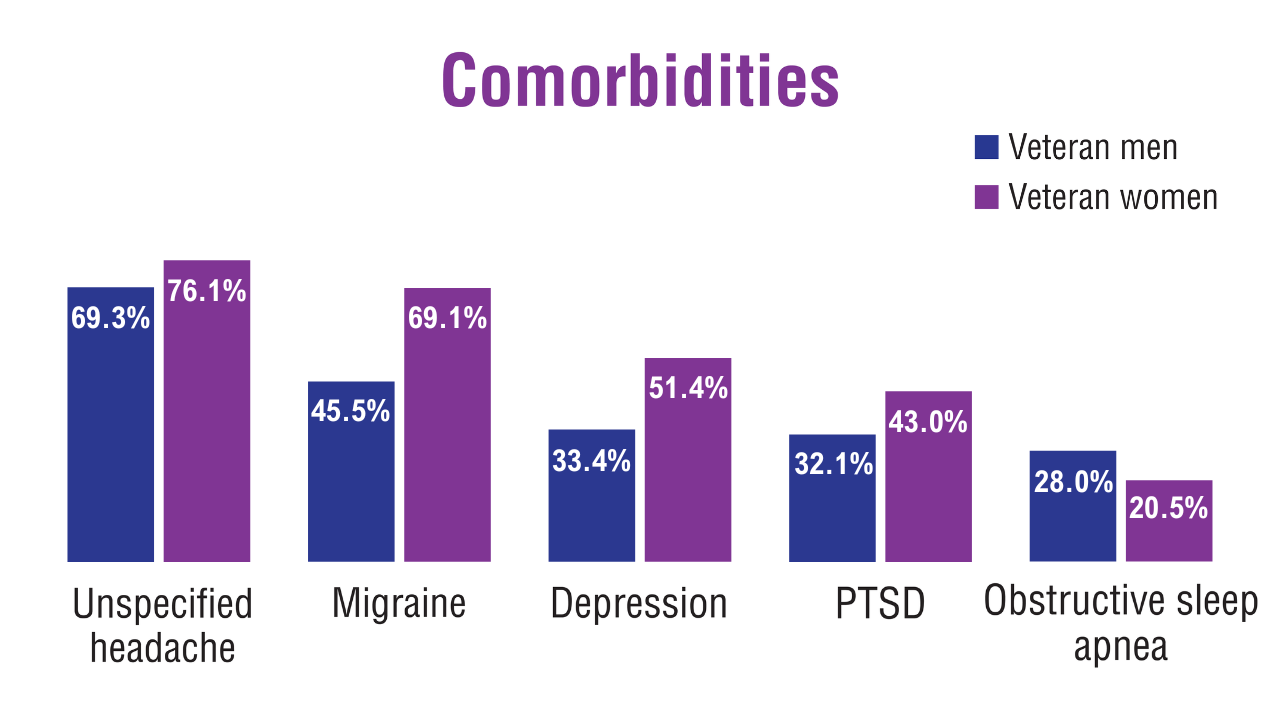

Data Trends 2025: Neurology

Data Trends 2025: Neurology

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Lin C, et al. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1392721. Published 2024 Mar 12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1392721

- Defense Medical Surveillance System, Theater Medical Data Store provided by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Prepared by the Traumatic Brain Injury Center of Excellence. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Center-of-Excellence/DODTBI-Worldwide-Numbers

- Karr JE, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2025;106(4):537-547. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2024.11.010

- Howard JT, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2025;12(3):1745-1756. doi:10.1007/s40615-024-02004-1

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- Roghani A, et al. Epilepsia. 2024;65(8):2255-2269. doi:10.1111/epi.18026

- Herbert MS, et al. Headache. 2025;65(3):430-438. doi:10.1111/head.14815

- Fleming NH, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;82:105372. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.105372

- Silveira SL, et al. CNS Spectr. 2024;29(6):1-8. doi:10.1017/S1092852924002165

- Whiteneck G, et al. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2024;39(5):E462-E469. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000952

Seng EK, et al. Headache. 2024;64(10):1273-1284. doi:10.1111/head.14842

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Lin C, et al. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1392721. Published 2024 Mar 12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1392721

- Defense Medical Surveillance System, Theater Medical Data Store provided by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Prepared by the Traumatic Brain Injury Center of Excellence. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Center-of-Excellence/DODTBI-Worldwide-Numbers

- Karr JE, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2025;106(4):537-547. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2024.11.010

- Howard JT, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2025;12(3):1745-1756. doi:10.1007/s40615-024-02004-1

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- Roghani A, et al. Epilepsia. 2024;65(8):2255-2269. doi:10.1111/epi.18026

- Herbert MS, et al. Headache. 2025;65(3):430-438. doi:10.1111/head.14815

- Fleming NH, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;82:105372. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.105372

- Silveira SL, et al. CNS Spectr. 2024;29(6):1-8. doi:10.1017/S1092852924002165

- Whiteneck G, et al. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2024;39(5):E462-E469. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000952

Seng EK, et al. Headache. 2024;64(10):1273-1284. doi:10.1111/head.14842

- Lin C, et al. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1392721. Published 2024 Mar 12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1392721

- Defense Medical Surveillance System, Theater Medical Data Store provided by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Prepared by the Traumatic Brain Injury Center of Excellence. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Center-of-Excellence/DODTBI-Worldwide-Numbers

- Karr JE, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2025;106(4):537-547. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2024.11.010

- Howard JT, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2025;12(3):1745-1756. doi:10.1007/s40615-024-02004-1

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- Roghani A, et al. Epilepsia. 2024;65(8):2255-2269. doi:10.1111/epi.18026

- Herbert MS, et al. Headache. 2025;65(3):430-438. doi:10.1111/head.14815

- Fleming NH, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;82:105372. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2023.105372

- Silveira SL, et al. CNS Spectr. 2024;29(6):1-8. doi:10.1017/S1092852924002165

- Whiteneck G, et al. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2024;39(5):E462-E469. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000952

Seng EK, et al. Headache. 2024;64(10):1273-1284. doi:10.1111/head.14842

Data Trends 2025: Neurology

Data Trends 2025: Neurology

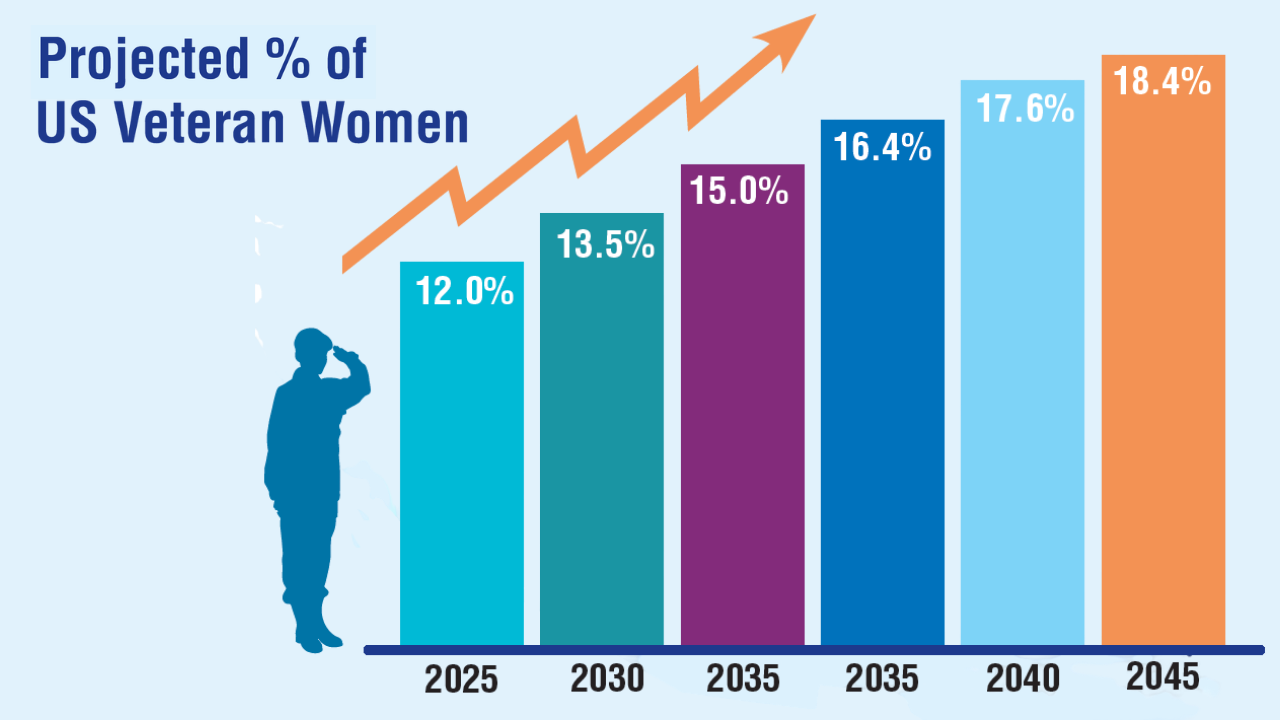

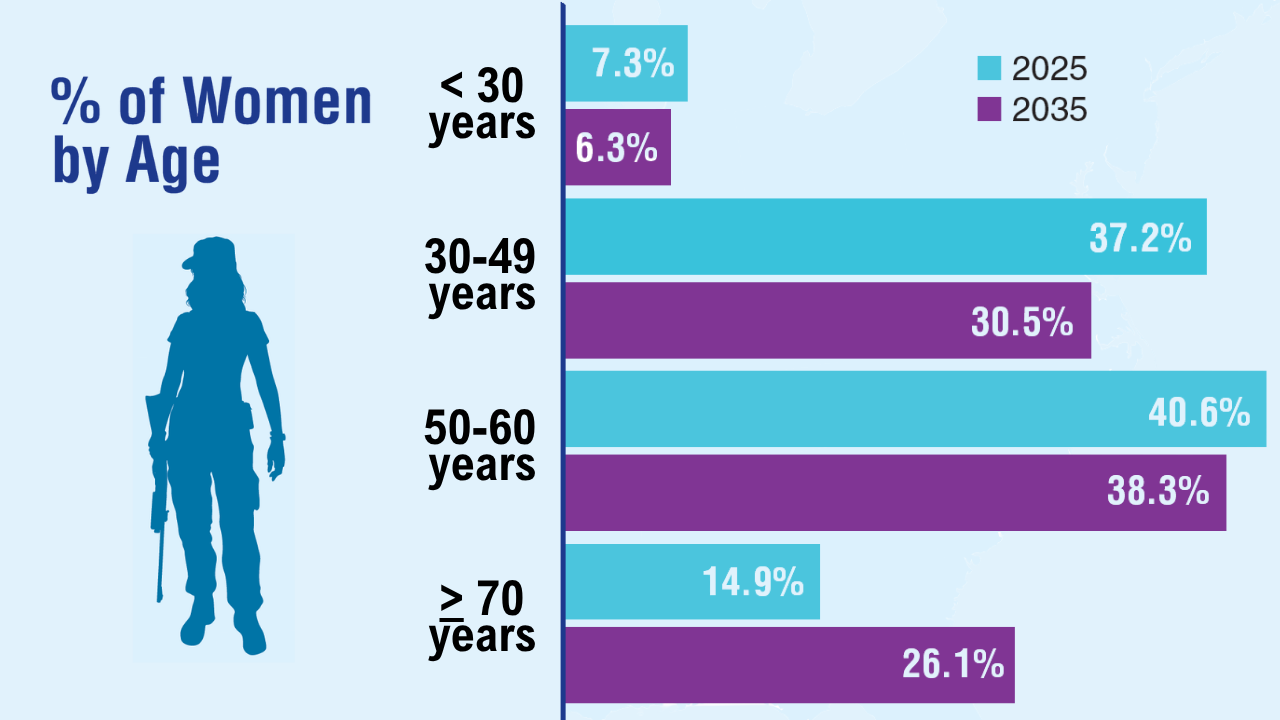

Data Trends 2025: Women's Health

Data Trends 2025: Women's Health

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Women Veterans Health Care: Facts and Statistics. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published 2022. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 5: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics and Utilization, Including Type, Modality, and Source of Care. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2024. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/VHA-Source-book-V5-FINAL.pdf

- Goldstein KM, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e256372. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2025.6372

- Sheahan KL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl 3):791-798. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07585-3

- Adams RE, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1-10. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01183-z

- Haskell SG, et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(2):267-271. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1262

- VHA Directive 1330.01(1): Health Care Services for Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs; February 15, 2023. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10576

- VHA Directive 1115(1): Military Sexual Trauma (MST) Program. US Department of Veterans Affairs; May 8, 2018. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=6432

- Marshall V, et al. Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(2):150-157. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.10.005

- Washington DL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):655-661. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z

- Hadlandsmyth K, et al. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(8):1311-1319. doi:10.1002/ejp.2258

- Military Sexual Trauma Fact Sheet–VA Mental Health. US Department of Veterans Affairs. May 1, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/mst_general_factsheet.pdf

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population Tables: the nation, age/sex. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp

- Serving Her Country: Exploring the Characteristics of Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.data.va.gov/stories/s/Women-Veterans-in-2023/wci3-yrsv/

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care: Final Report. February 2024. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/publications-and-reports.asp

- Iverson KM, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2435-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05240-y

- Spinelli S, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(suppl 3):837-841. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07577-3

- Carlson K, et al. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated January 22,2025. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/

Monteith LL, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(11-12):7578-7601. doi:10.1177/08862605221145725

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Women Veterans Health Care: Facts and Statistics. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published 2022. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 5: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics and Utilization, Including Type, Modality, and Source of Care. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2024. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/VHA-Source-book-V5-FINAL.pdf

- Goldstein KM, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e256372. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2025.6372

- Sheahan KL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl 3):791-798. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07585-3

- Adams RE, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1-10. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01183-z

- Haskell SG, et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(2):267-271. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1262

- VHA Directive 1330.01(1): Health Care Services for Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs; February 15, 2023. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10576

- VHA Directive 1115(1): Military Sexual Trauma (MST) Program. US Department of Veterans Affairs; May 8, 2018. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=6432

- Marshall V, et al. Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(2):150-157. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.10.005

- Washington DL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):655-661. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z

- Hadlandsmyth K, et al. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(8):1311-1319. doi:10.1002/ejp.2258

- Military Sexual Trauma Fact Sheet–VA Mental Health. US Department of Veterans Affairs. May 1, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/mst_general_factsheet.pdf

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population Tables: the nation, age/sex. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp

- Serving Her Country: Exploring the Characteristics of Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.data.va.gov/stories/s/Women-Veterans-in-2023/wci3-yrsv/

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care: Final Report. February 2024. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/publications-and-reports.asp

- Iverson KM, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2435-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05240-y

- Spinelli S, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(suppl 3):837-841. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07577-3

- Carlson K, et al. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated January 22,2025. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/

Monteith LL, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(11-12):7578-7601. doi:10.1177/08862605221145725

- Women Veterans Health Care: Facts and Statistics. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published 2022. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 5: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics and Utilization, Including Type, Modality, and Source of Care. US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2024. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/VHA-Source-book-V5-FINAL.pdf

- Goldstein KM, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e256372. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2025.6372

- Sheahan KL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl 3):791-798. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07585-3

- Adams RE, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1-10. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01183-z

- Haskell SG, et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(2):267-271. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1262

- VHA Directive 1330.01(1): Health Care Services for Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs; February 15, 2023. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10576

- VHA Directive 1115(1): Military Sexual Trauma (MST) Program. US Department of Veterans Affairs; May 8, 2018. Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=6432

- Marshall V, et al. Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(2):150-157. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.10.005

- Washington DL, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):655-661. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z

- Hadlandsmyth K, et al. Eur J Pain. 2024;28(8):1311-1319. doi:10.1002/ejp.2258

- Military Sexual Trauma Fact Sheet–VA Mental Health. US Department of Veterans Affairs. May 1, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/mst_general_factsheet.pdf

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population Tables: the nation, age/sex. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp

- Serving Her Country: Exploring the Characteristics of Women Veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.data.va.gov/stories/s/Women-Veterans-in-2023/wci3-yrsv/

- Gasperi M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e242299. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.2299

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care: Final Report. February 2024. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/publications-and-reports.asp

- Iverson KM, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2435-2442. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05240-y

- Spinelli S, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(suppl 3):837-841. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07577-3

- Carlson K, et al. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated January 22,2025. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/

Monteith LL, et al. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(11-12):7578-7601. doi:10.1177/08862605221145725

Data Trends 2025: Women's Health

Data Trends 2025: Women's Health

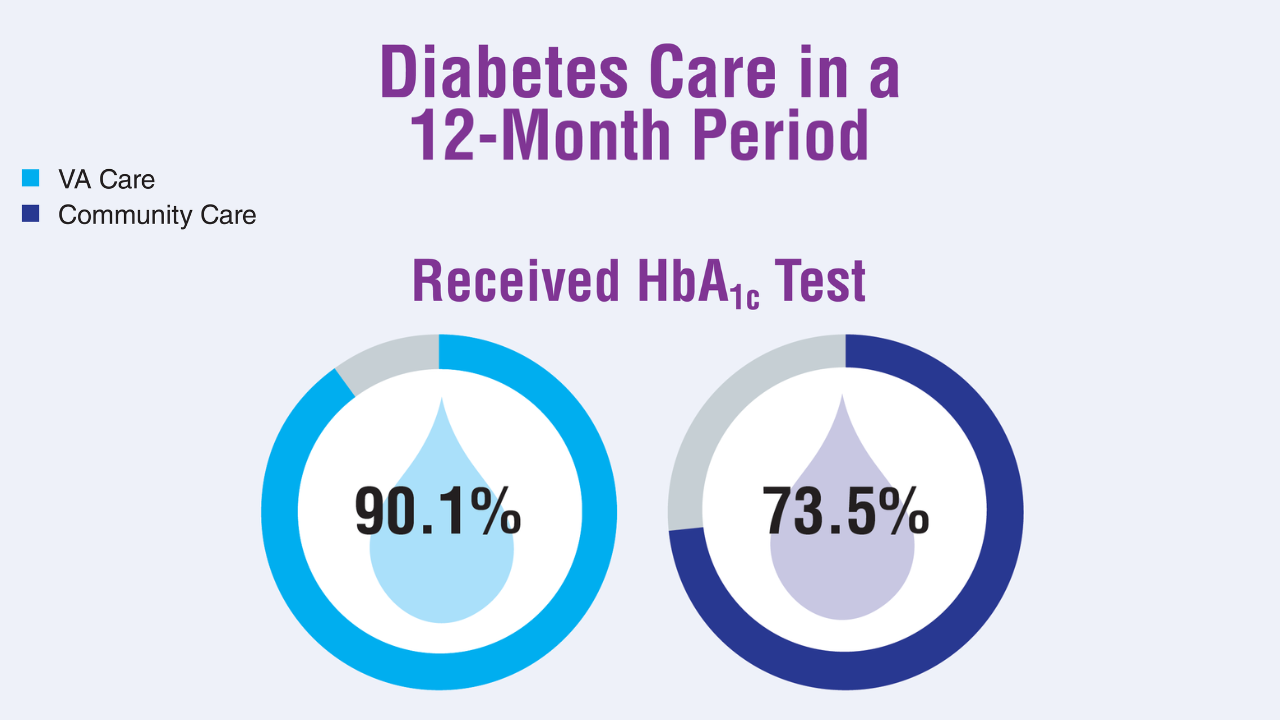

Data Trends 2025: Diabetes

Diabetes

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA improving diabetes care with patient generated health data. VA News. March 12, 2025. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://news.va.gov/138644/va-diabetes-care-with-patient-generated-data/

2. Diabetes basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/index.html

3. Hua S, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(11):1978-1984. doi:10.2337/dc24-0892

4. Lipska KJ, et al. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2024;26(12):908-917. doi:10.1089/dia.2024.0152

5. Yoon J, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2025;40(3):647-653. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08968-4

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA improving diabetes care with patient generated health data. VA News. March 12, 2025. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://news.va.gov/138644/va-diabetes-care-with-patient-generated-data/

2. Diabetes basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/index.html

3. Hua S, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(11):1978-1984. doi:10.2337/dc24-0892

4. Lipska KJ, et al. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2024;26(12):908-917. doi:10.1089/dia.2024.0152

5. Yoon J, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2025;40(3):647-653. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08968-4

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA improving diabetes care with patient generated health data. VA News. March 12, 2025. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://news.va.gov/138644/va-diabetes-care-with-patient-generated-data/

2. Diabetes basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/index.html

3. Hua S, et al. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(11):1978-1984. doi:10.2337/dc24-0892

4. Lipska KJ, et al. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2024;26(12):908-917. doi:10.1089/dia.2024.0152

5. Yoon J, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2025;40(3):647-653. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08968-4

Diabetes

Diabetes

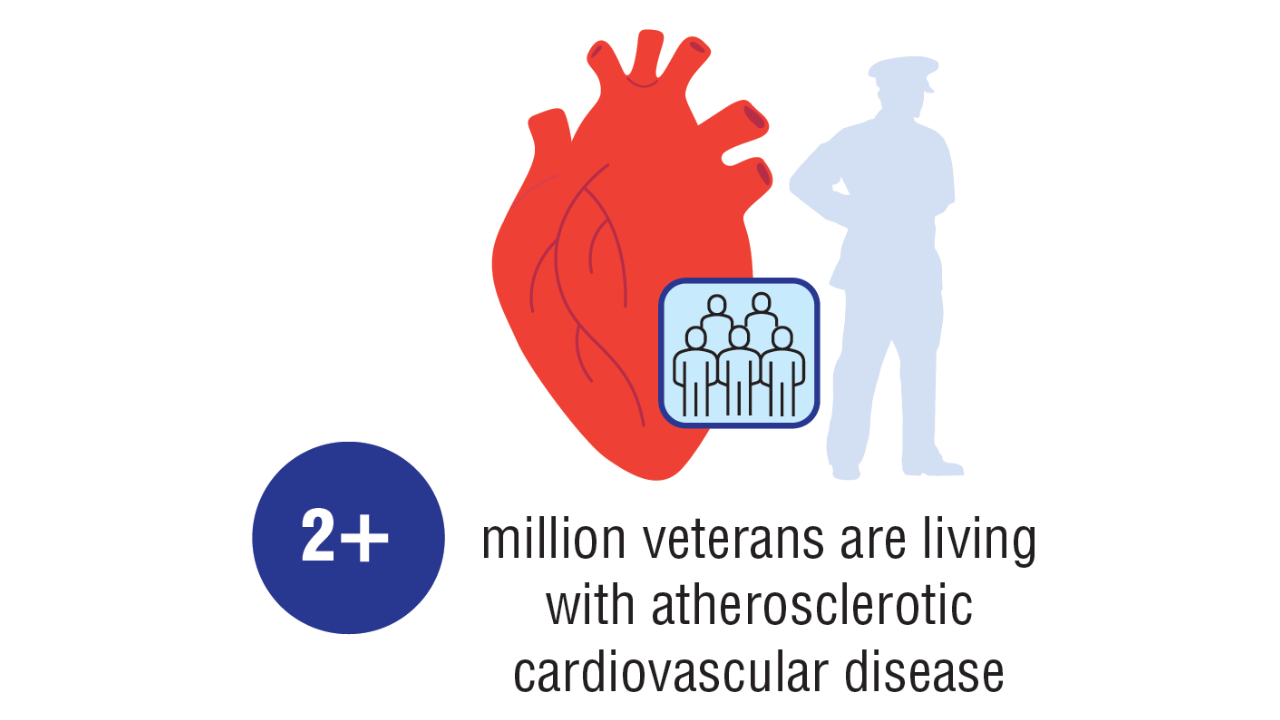

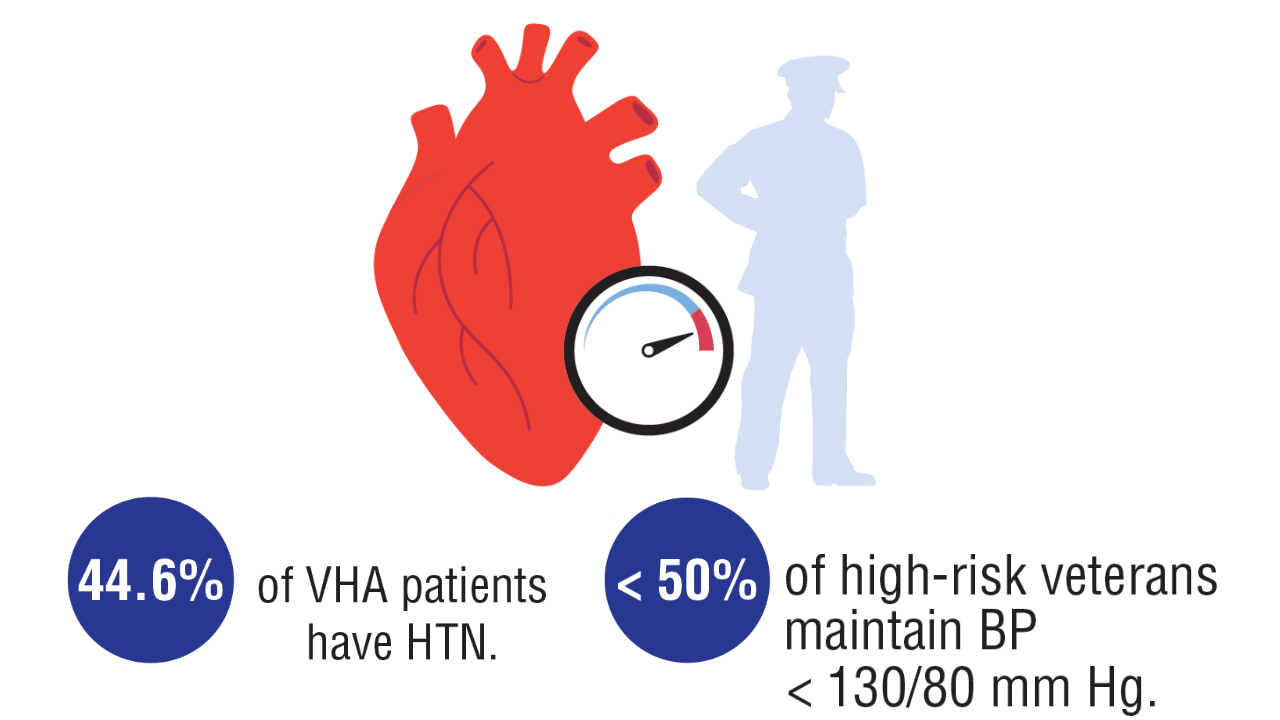

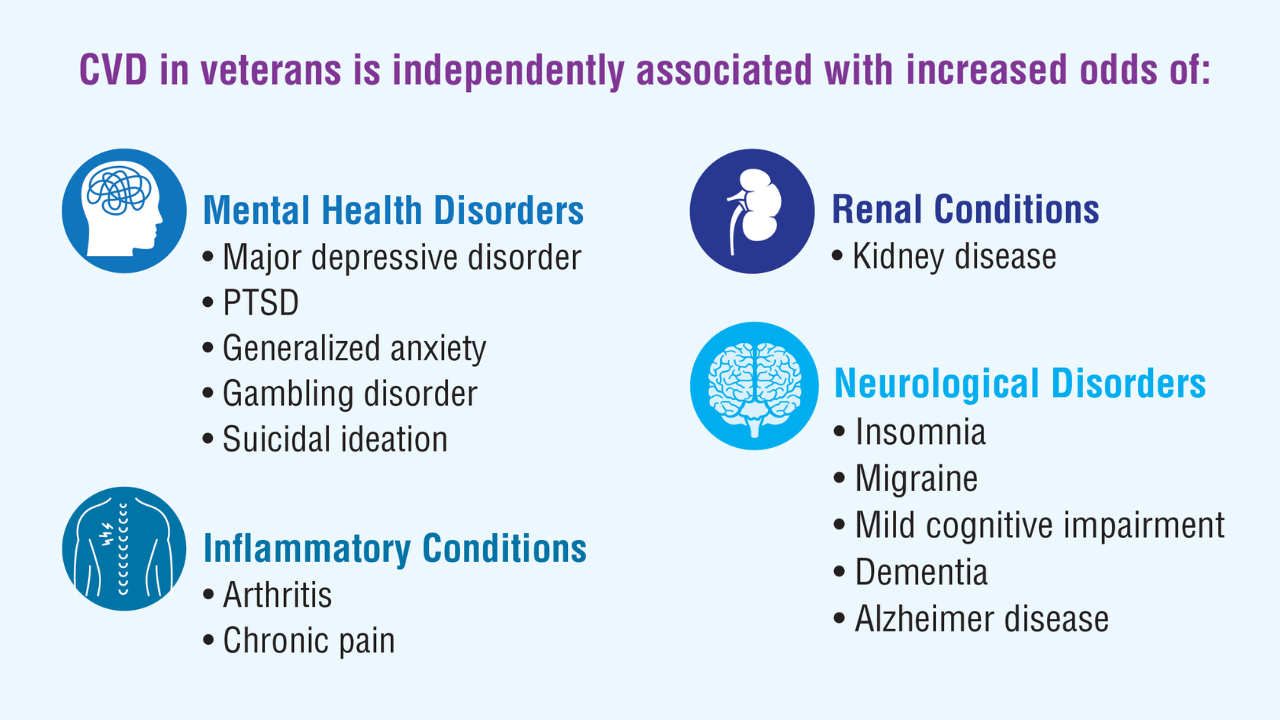

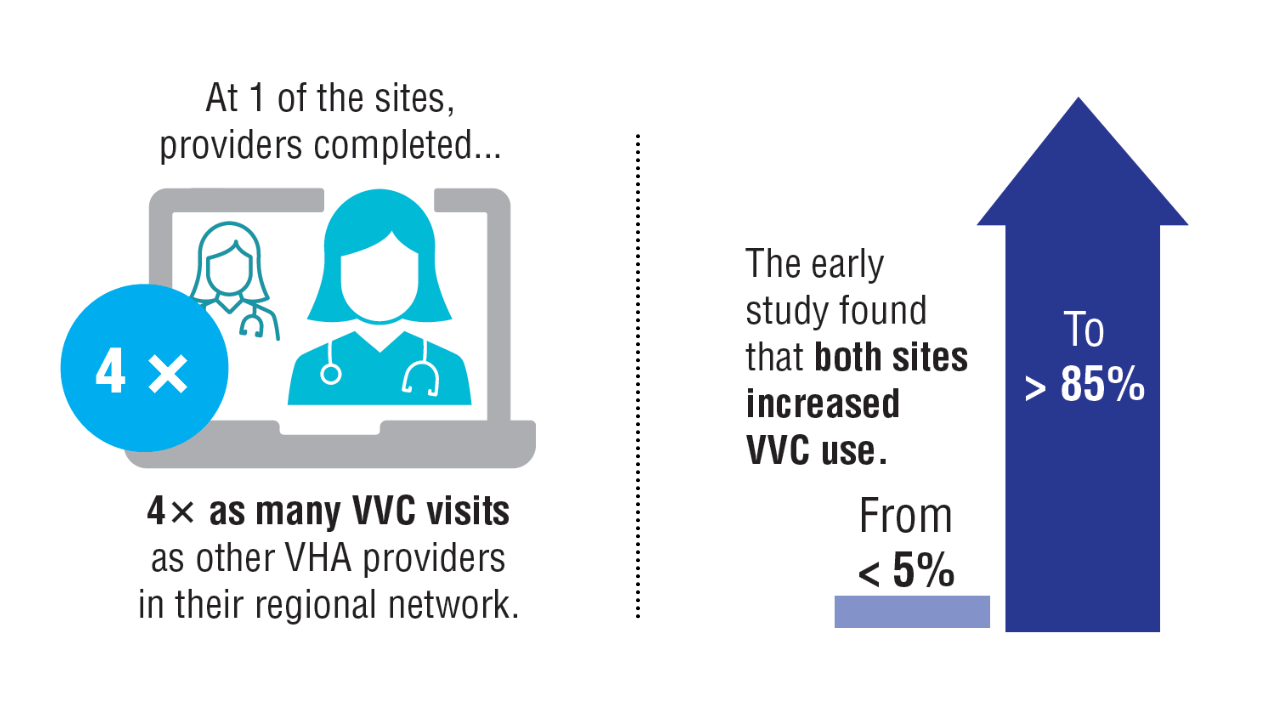

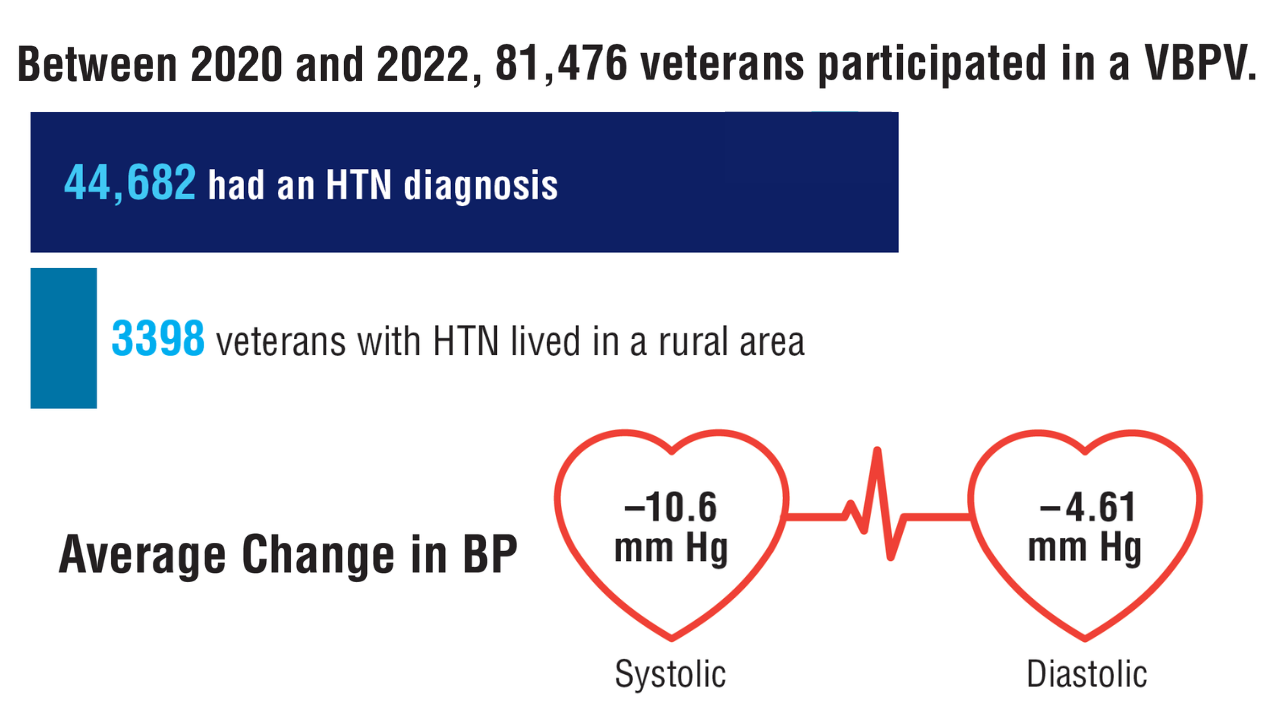

Data Trends 2025: Cardiology

Data Trends 2025: Cardiology

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Almuwaqqat Z, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243062. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3062

- Carrico M, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(4):1006-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2023.0269

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. National veteran health equity report 2021. September 2022:177-179. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/NVHER_2021_Report_508_Conformant.pdf

- New program for veterans with cholesterol, associated cardiovascular disease [press release]. American Heart Association. March 21, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/new-program-for-veterans-with-high-cholesterol-associated-cardiovascular-disease

Washington DL, et al. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. February 2024. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/Rates_of_Hypertension_by_Race_or_Ethnicity.pdf

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

- Almuwaqqat Z, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243062. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3062

- Carrico M, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(4):1006-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2023.0269

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. National veteran health equity report 2021. September 2022:177-179. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/NVHER_2021_Report_508_Conformant.pdf

- New program for veterans with cholesterol, associated cardiovascular disease [press release]. American Heart Association. March 21, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/new-program-for-veterans-with-high-cholesterol-associated-cardiovascular-disease

Washington DL, et al. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. February 2024. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/Rates_of_Hypertension_by_Race_or_Ethnicity.pdf

- Almuwaqqat Z, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243062. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3062

- Carrico M, et al. Telemed J E Health. 2024;30(4):1006-1012. doi:10.1089/tmj.2023.0269

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. National veteran health equity report 2021. September 2022:177-179. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/NVHER_2021_Report_508_Conformant.pdf

- New program for veterans with cholesterol, associated cardiovascular disease [press release]. American Heart Association. March 21, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/new-program-for-veterans-with-high-cholesterol-associated-cardiovascular-disease

Washington DL, et al. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Health Equity. February 2024. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/docs/Rates_of_Hypertension_by_Race_or_Ethnicity.pdf

Data Trends 2025: Cardiology

Data Trends 2025: Cardiology

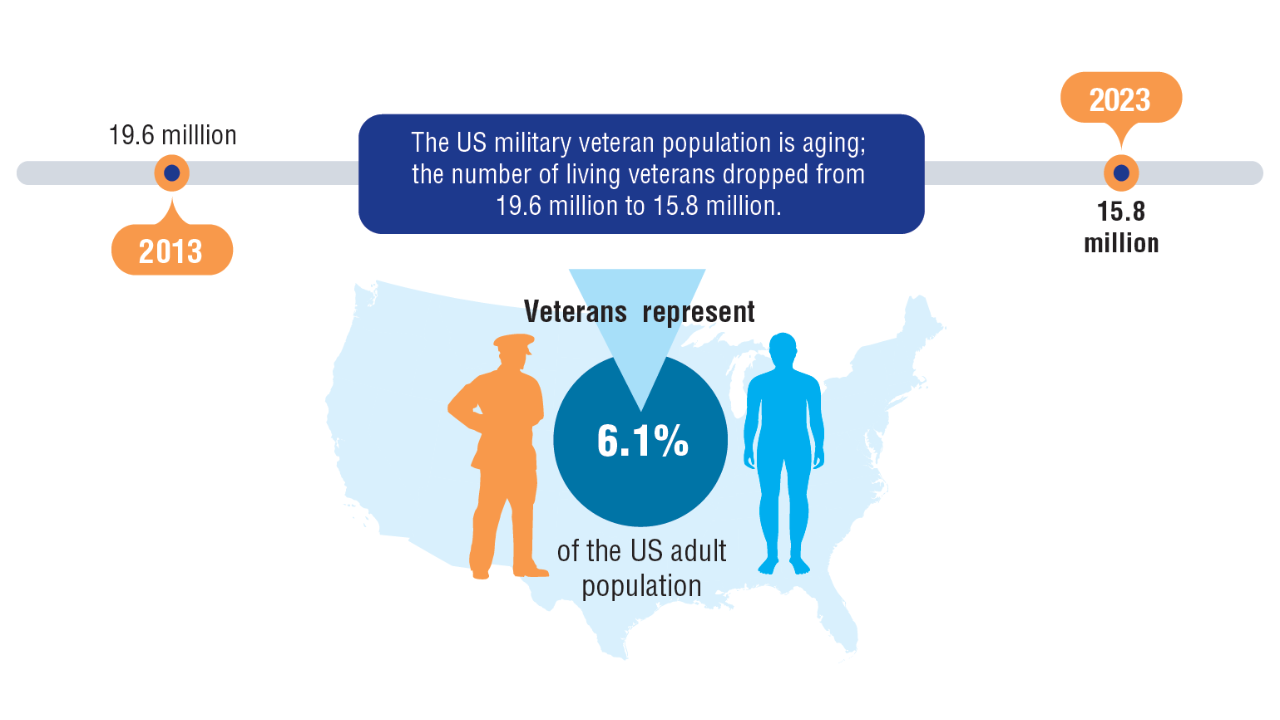

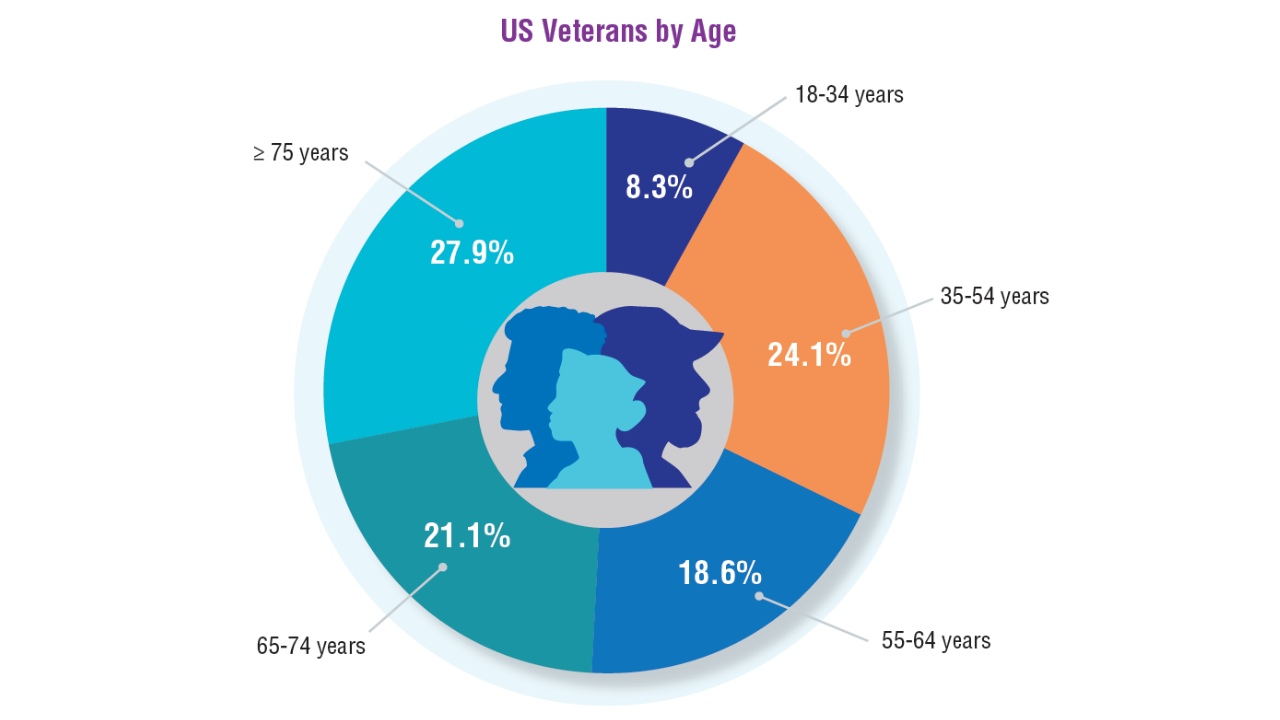

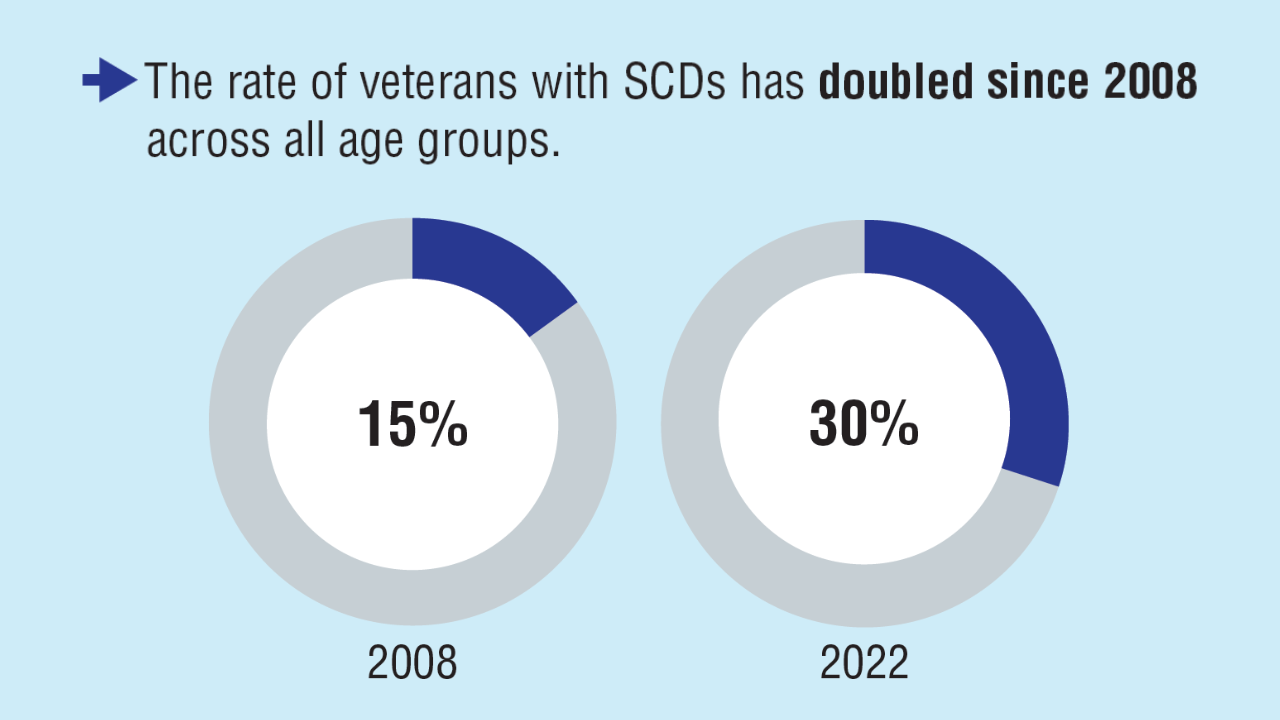

Data Trends 2025: Veteran Health at a Glance

Veteran Health at a Glance

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. United States Census Bureau. Veterans Day 2024: November 11 [press release]. October 16, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/

facts-for-features/2024/veterans-day.html

2. American Community Survey, 2023: ACS 1-year estimates subject tables:S2101 veteran status. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://data.

census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S2101

3. Vespa J, Carter C. Trends in veteran disability status and service-connected disability: 2008-2022. ACS-58. United States Census Bureau. November 6, 2024. Accessed

April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2024/acs/acs-58.html

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2024. Accessed June 9, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2024-abr.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2023-abr.pdf

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2022. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2022-abr.pdf

7. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. ACS-54. United States Census Bureau. July 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/

content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

8. A profile of older US veterans. National Council on Aging. November 6, 2019. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.ncoa.org/article/a-profile-of-older-us-veterans/

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

Click here to view more from Federal Health Care Data Trends 2025.

1. United States Census Bureau. Veterans Day 2024: November 11 [press release]. October 16, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/

facts-for-features/2024/veterans-day.html

2. American Community Survey, 2023: ACS 1-year estimates subject tables:S2101 veteran status. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://data.

census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S2101

3. Vespa J, Carter C. Trends in veteran disability status and service-connected disability: 2008-2022. ACS-58. United States Census Bureau. November 6, 2024. Accessed

April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2024/acs/acs-58.html

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2024. Accessed June 9, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2024-abr.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2023-abr.pdf

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2022. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2022-abr.pdf

7. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. ACS-54. United States Census Bureau. July 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/

content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

8. A profile of older US veterans. National Council on Aging. November 6, 2019. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.ncoa.org/article/a-profile-of-older-us-veterans/

1. United States Census Bureau. Veterans Day 2024: November 11 [press release]. October 16, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/

facts-for-features/2024/veterans-day.html

2. American Community Survey, 2023: ACS 1-year estimates subject tables:S2101 veteran status. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://data.

census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S2101

3. Vespa J, Carter C. Trends in veteran disability status and service-connected disability: 2008-2022. ACS-58. United States Census Bureau. November 6, 2024. Accessed

April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2024/acs/acs-58.html

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2024. Accessed June 9, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2024-abr.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2023-abr.pdf

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration. Annual benefits report fiscal year 2022. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.benefits.va.gov/

REPORTS/abr/docs/2022-abr.pdf

7. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. ACS-54. United States Census Bureau. July 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.census.gov/

content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

8. A profile of older US veterans. National Council on Aging. November 6, 2019. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.ncoa.org/article/a-profile-of-older-us-veterans/

Veteran Health at a Glance

Veteran Health at a Glance

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

PRACTICE POINTS

- Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of acquired hyperpigmentation and should be evaluated after metabolic or endocrine causes are ruled out.

- Belumosudil for chronic graft-vs-host disease can induce rapid-onset diffuse bronzing hyperpigmentation, even in the absence of other systemic or laboratory abnormalities.

- Treatment entails discontinuation of the offending agent and limitation of exacerbating factors such as sun exposure.

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

Enhancing Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Patient Education, Communication, and Anxiety Management

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS)—developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s—is the gold standard for treating various cutaneous malignancies. It provides maximal conservation of uninvolved tissues while producing higher cure rates compared to wide local excision.1,2

We sought to assess the various characteristics that impact patient satisfaction to help Mohs surgeons incorporate relatively simple yet clinically significant practices into their patient encounters. We conducted a systematic literature search of peer-reviewed PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from database inception through November 2023 using the terms Mohs micrographic surgery and patient satisfaction. Among the inclusion criteria were studies involving participants having undergone MMS, with objective assessments on patient-reported satisfaction or preferences related to patient education, communication, anxiety-alleviating measures, or QOL in MMS. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet these criteria, were outdated and no longer clinically relevant, or measured unalterable factors with no significant impact on how Mohs surgeons could change clinical practice. Of the 157 nonreplicated studies identified, 34 met inclusion criteria.

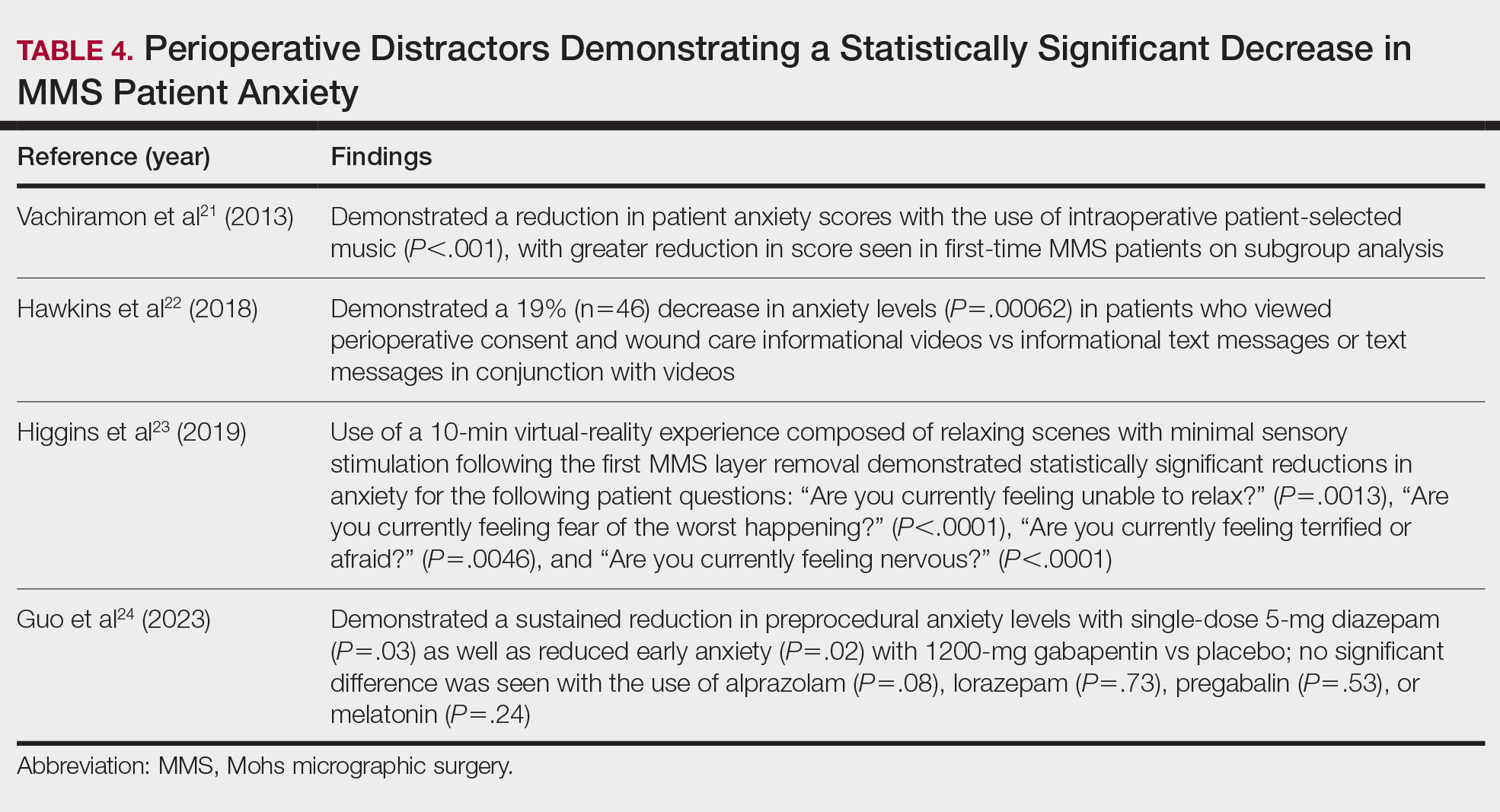

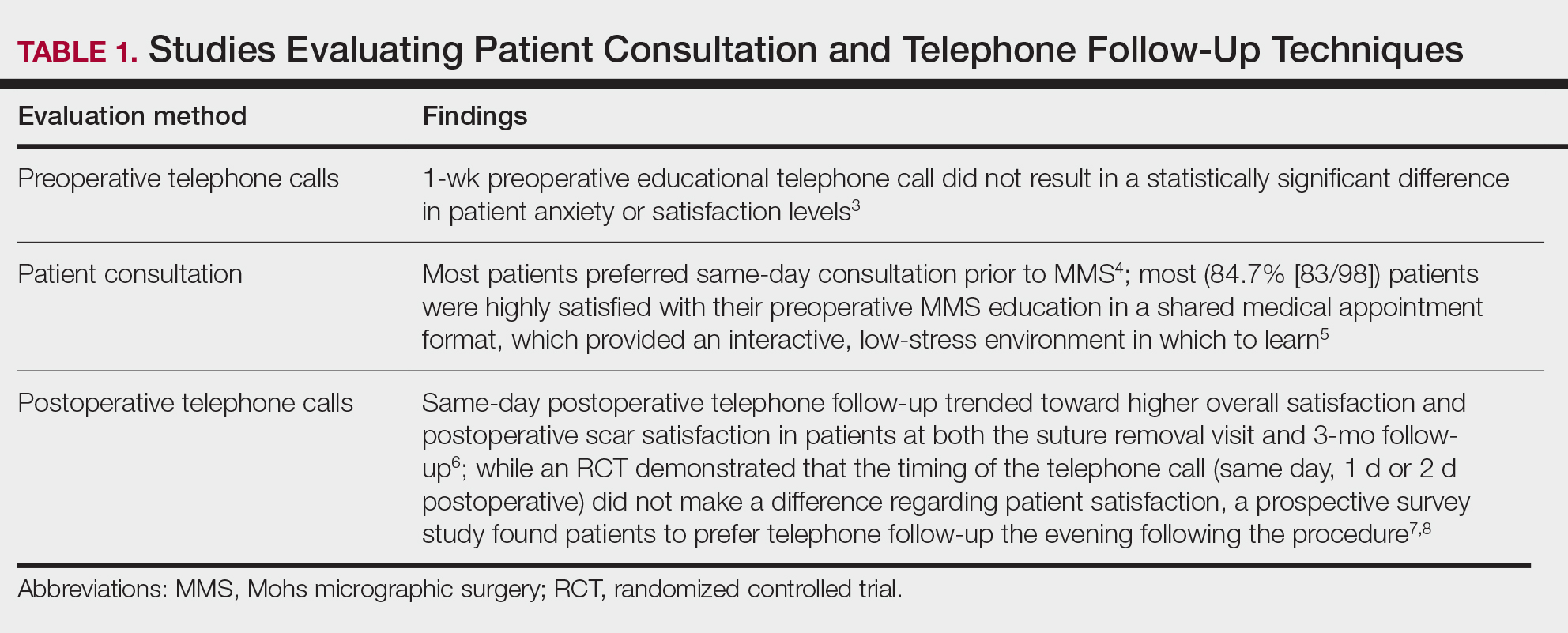

Perioperative Patient Communication and Education Techniques

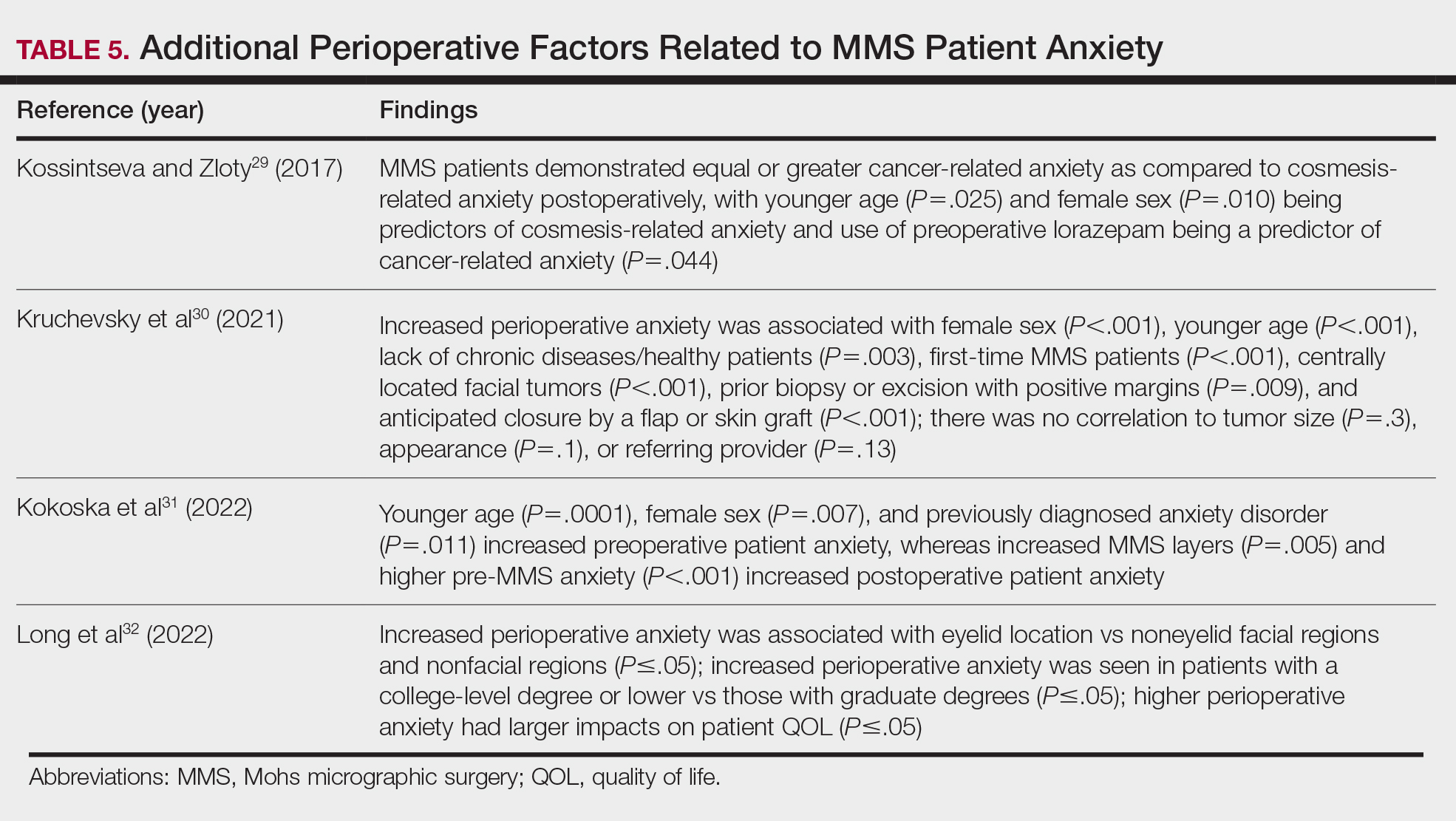

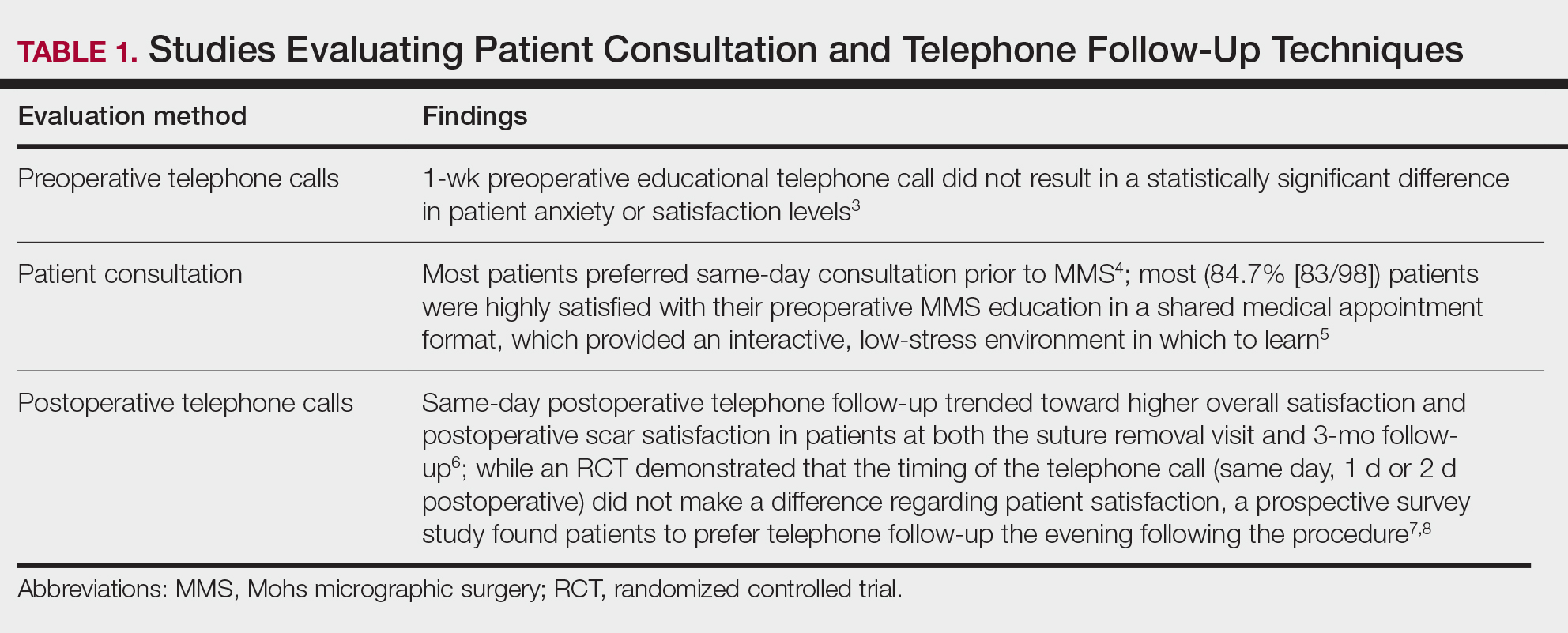

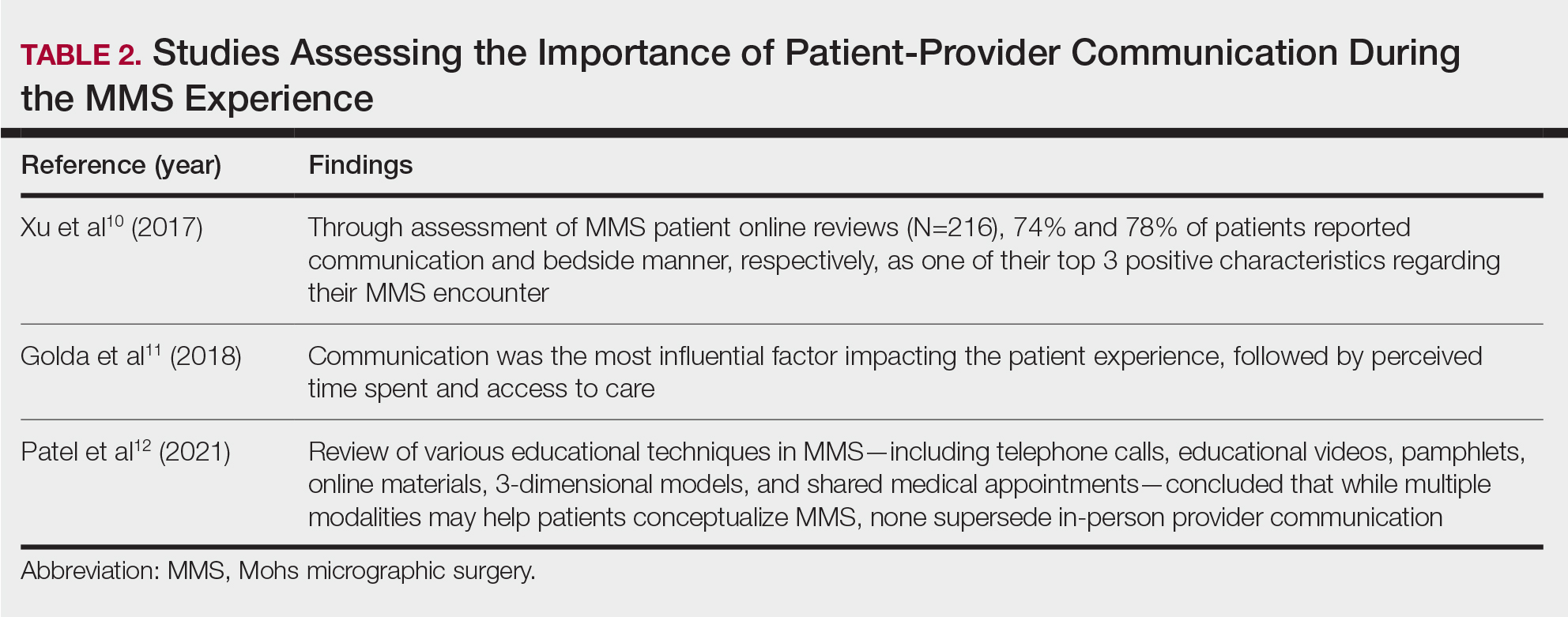

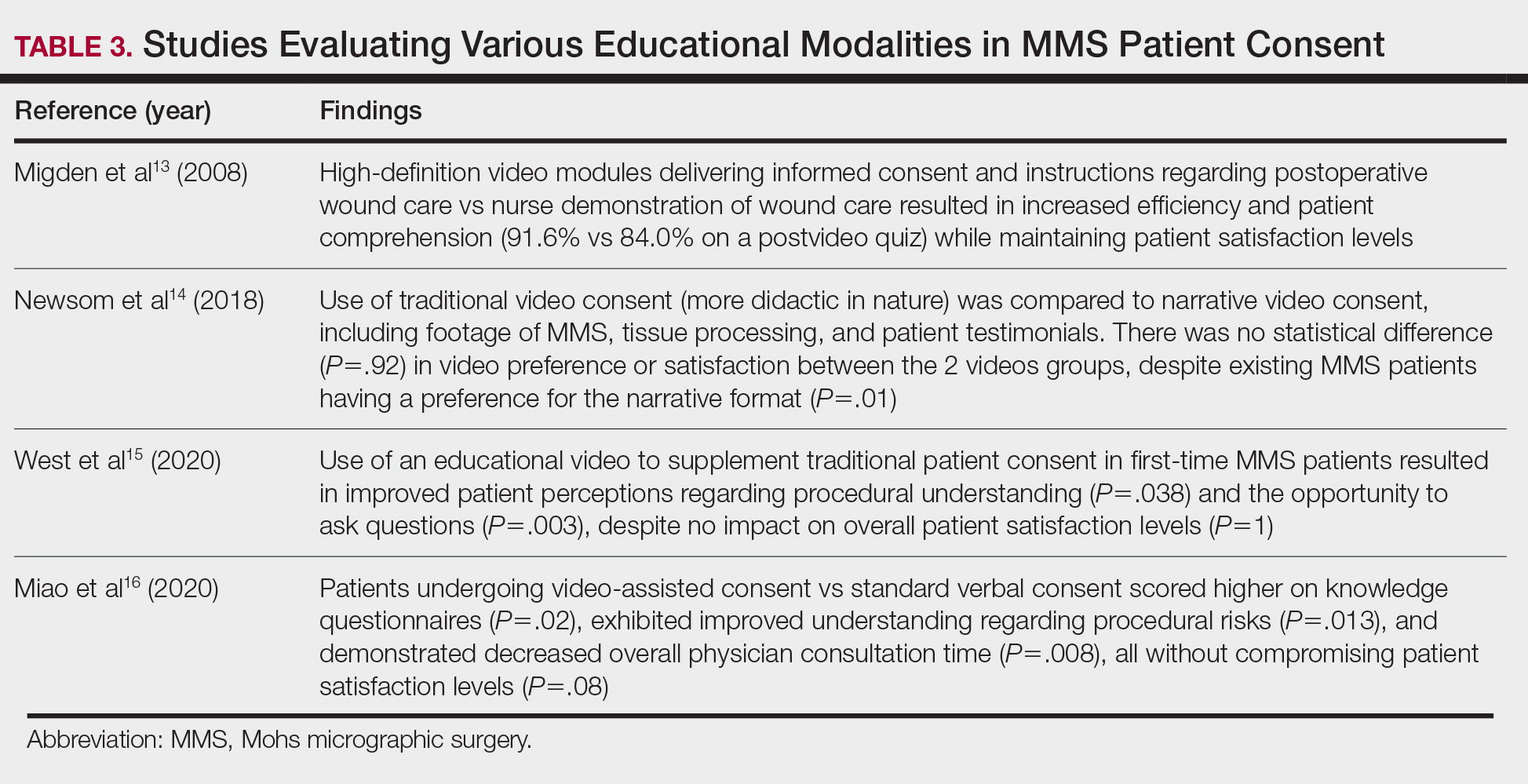

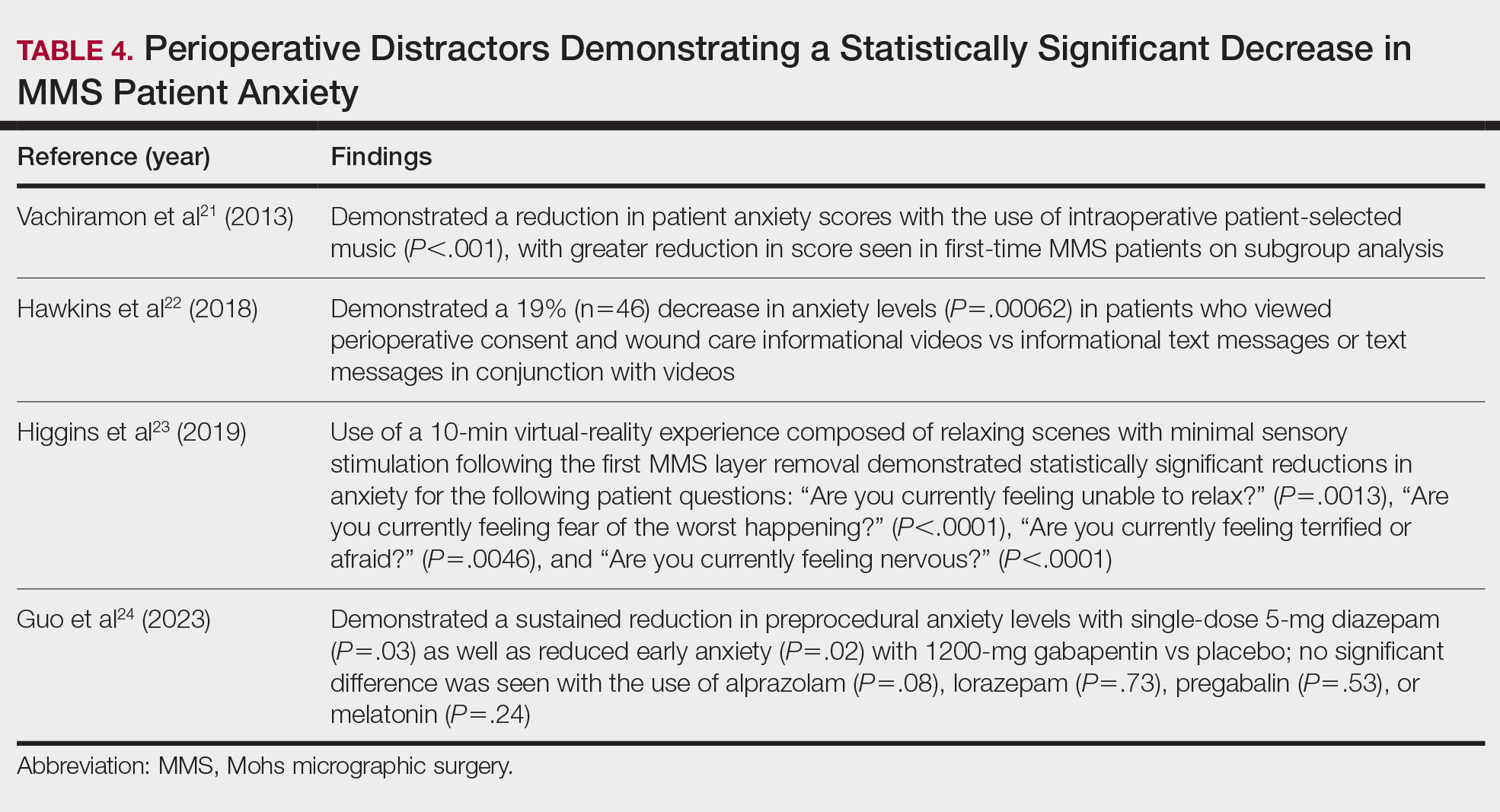

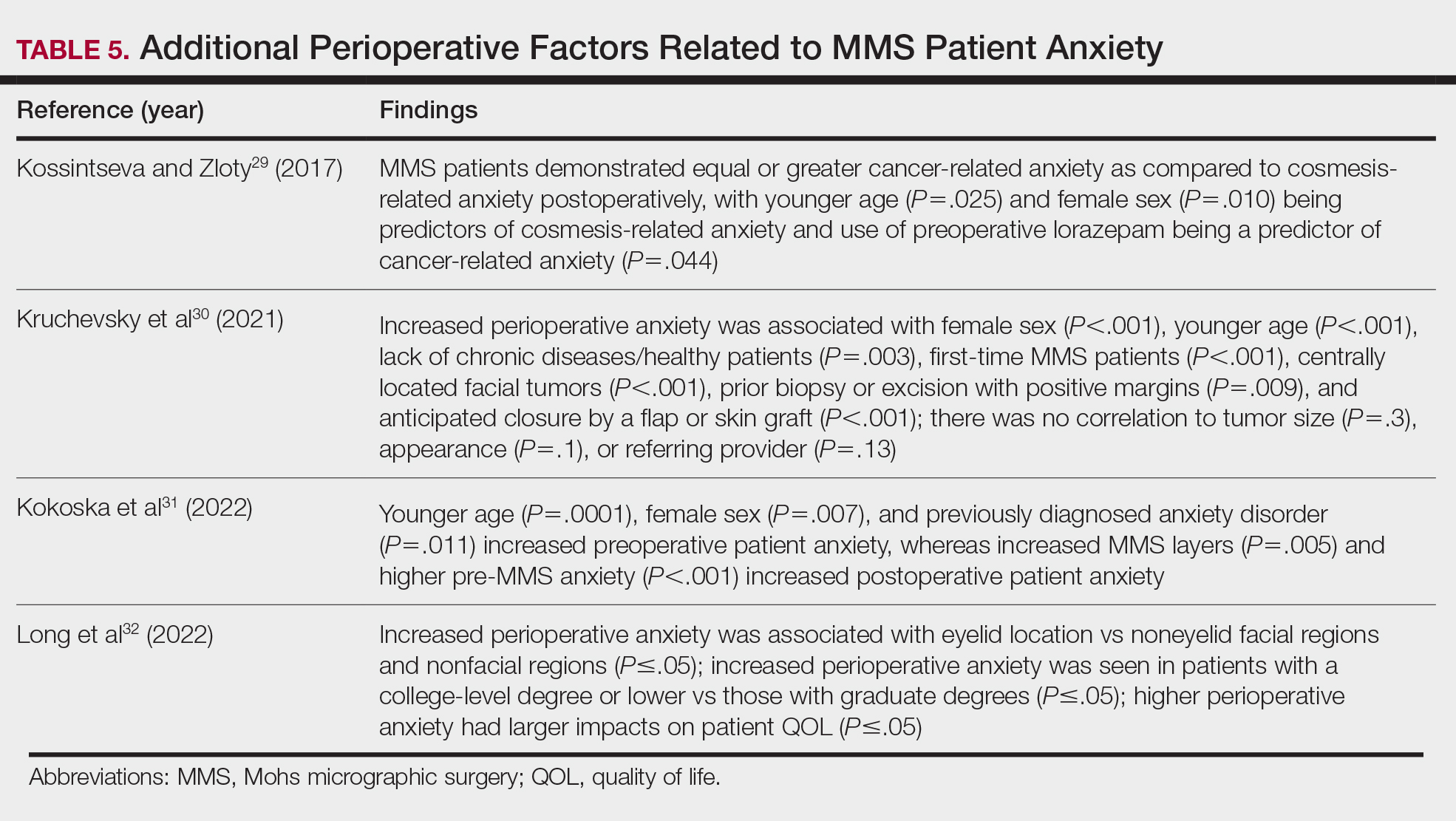

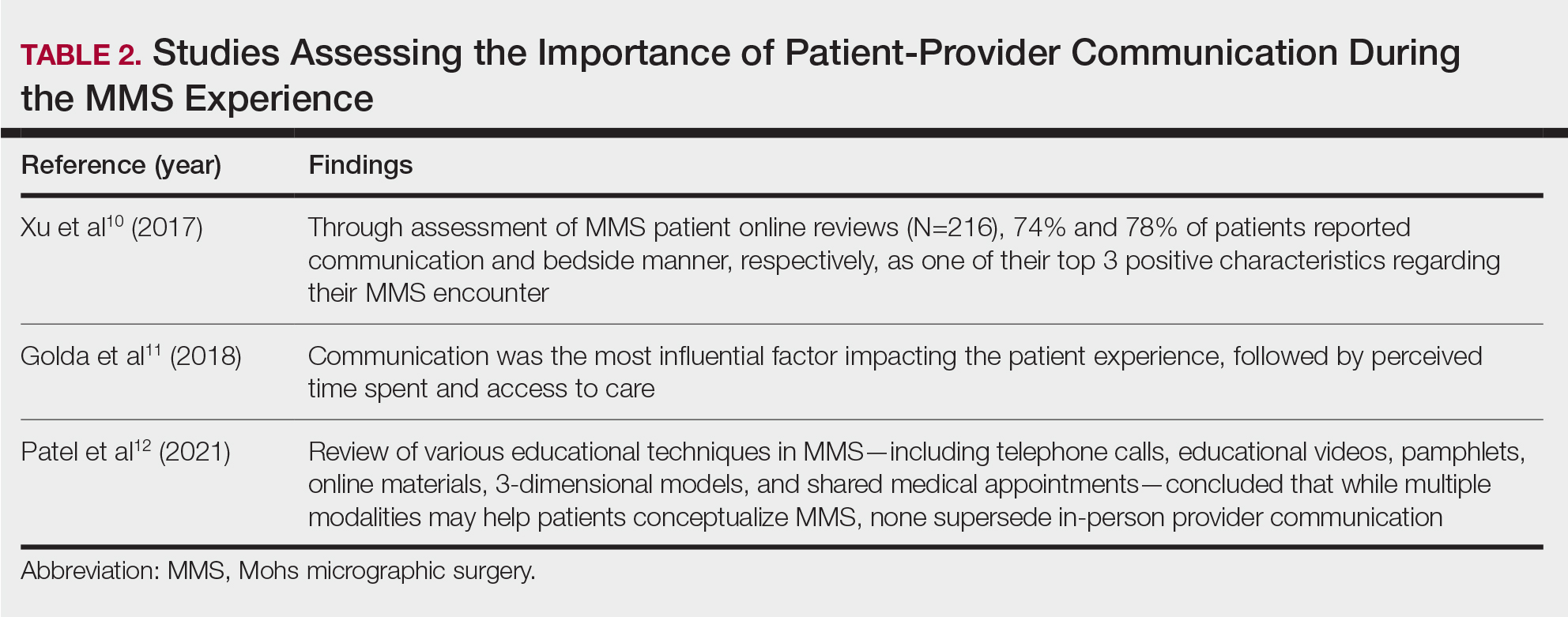

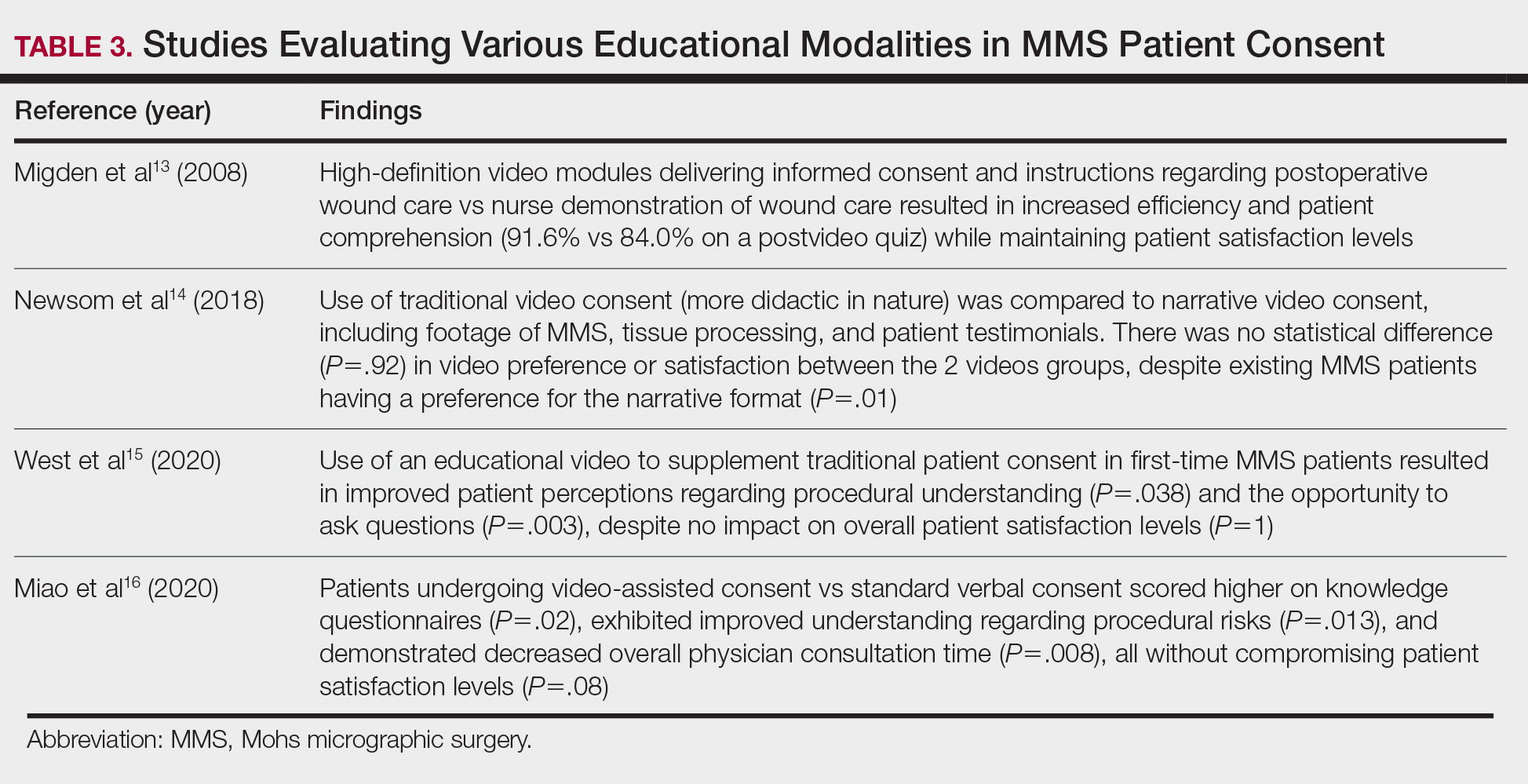

Perioperative Patient Communication—Many studies have evaluated the impact of perioperative patient-provider communication and education on patient satisfaction in those undergoing MMS. Studies focusing on preoperative and postoperative telephone calls, patient consultation formats, and patient-perceived impact of such communication modalities have been well documented (Table 1).3-8 The importance of the patient follow-up after MMS was further supported by a retrospective study concluding that 88.7% (86/97) of patients regarded follow-up visits as important, and 80% (77/97) desired additional follow-up 3 months after MMS.9 Additional studies have highlighted the importance of thorough and open perioperative patient-provider communication during MMS (Table 2).10-12

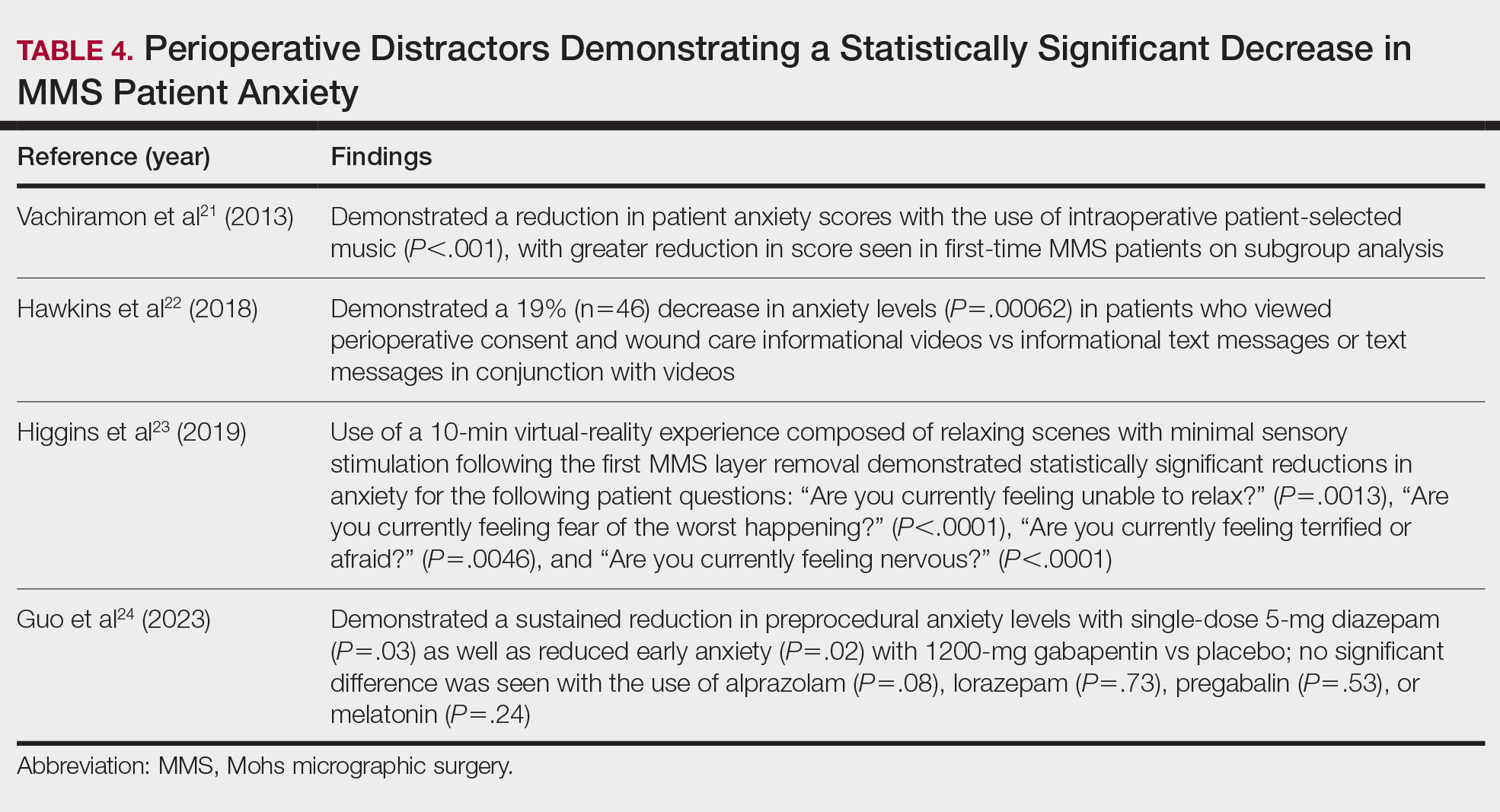

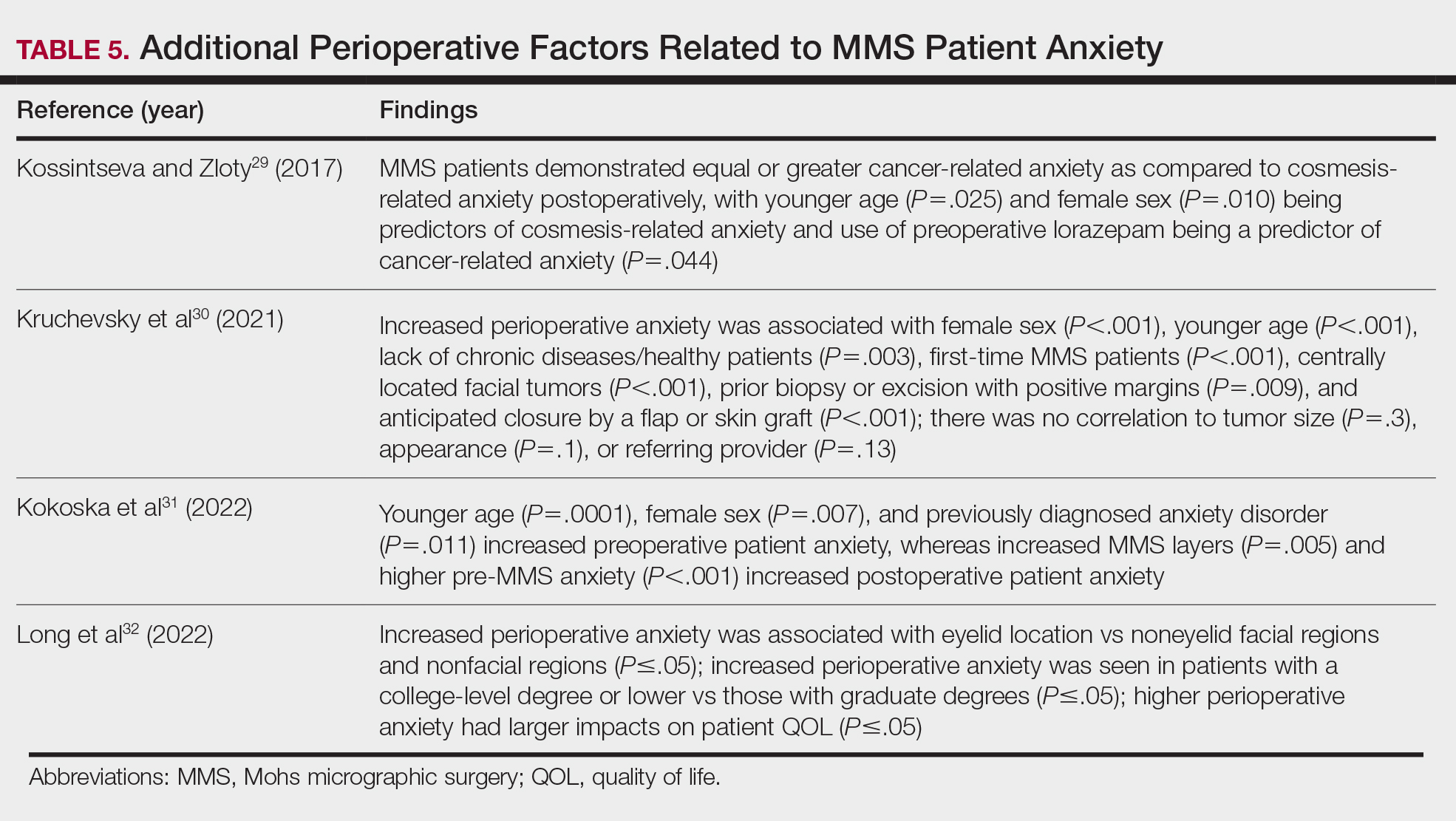

Patient-Education Techniques—Many studies have assessed the use of visual models to aid in patient education on MMS, specifically the preprocedural consent process (Table 3).13-16 Additionally, 2 randomized controlled trials assessing the use of at-home and same-day in-office preoperative educational videos concluded that these interventions increased patient knowledge and confidence regarding procedural risks and benefits, with no statistically significant differences in patient anxiety or satisfaction.17,18