User login

Needs of Veterans With Personality Disorder Diagnoses in Community-Based Mental Health Care

Needs of Veterans With Personality Disorder Diagnoses in Community-Based Mental Health Care

Personality disorders (PDs) are enduring patterns of internal experience and behavior that differ from cultural norms and expectations, are inflexible and pervasive, have their onset in adolescence or early adulthood, and lead to distress or impairment. Ten PDs are included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition): paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive.1 These disorders impose a high burden on patients, families, health care systems, and broader economic systems.2,3 Up to 1 in 7 persons in the community and 50% of those receiving outpatient mental health treatment experience a PD.4,5 These conditions are associated with an increased risk of adverse events, including suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, homelessness, substance use, underemployment, relational issues, and high utilization of psychiatric services.6-9 PDs are routinely underassessed, underdocumented, and undertreated in clinical settings, and consistently receive less research funding than other, less prevalent forms of psychopathology. 10-12 As a result, there is limited understanding of clinical needs of individuals experiencing PDs.

MILITARY VETERANS WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Underacknowledgment of PDs and their associated difficulties may be especially pronounced in veteran populations. Due to longstanding etiological theories that implicate childhood trauma and adolescent onset in pathology development, PDs are traditionally considered pre-existing conditions or developmental abnormalities by the US Department of Defense and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a result, PDs are therefore deemed incompatible with military service and ineligible for service-connected disability benefits.13-15 Such determinations allowed PD pathology to be used as grounds for discharge for 26,000 service members from 2001 to 2007, or 2.6% of total enlisted discharges during that period.13,15,16

Despite this structural discrimination, recent research suggests veterans may be more likely to experience PD pathology than the general population.17 For example, a 2021 epidemiological survey in a community-based veteran sample found elevated rates of borderline, antisocial, and schizotypal PDs (6%-13%).6 In contrast, only 0.8% to 5.0% of veteran electronic health records (EHRs) have a documented PD diagnosis.8,18,19 Such elevations in PD pathology within veteran samples imply either a disproportionately high prevalence among enlistees (and therefore missed during recruitment procedures) or onset following military service, possibly due to exposure to traumatic events and/ or occupational stress.17 Due to the relative infancy of research in this area and a lack of longitudinal studies, etiology and course of illness for personality pathology in veterans remains largely unclear.

Structural underacknowledgment of PDs among military personnel has contributed to their underrepresentation in research on veteran populations. PD-focused research with veterans is rare, despite a rapid increase in broader empirical attention paid to these conditions in nonveteran samples.20 A recent meta-analysis of veterans with PDs identified 27 studies that included basic prevalence statistics. PDs were rarely a primary focus for these studies, and most were limited to veterans seen in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) settings.17 The literature also paints a bleak picture, suggesting veterans who experience PDs are at higher risk for suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, and homelessness. They also tend to experience more severe comorbid psychopathological symptoms and more often use high-intensity mental health services (eg, care within emergency departments or psychiatric inpatient settings) than veterans without PD pathology.6,8,18,19,21 However, PD pathology does not appear to impede the effectiveness of treatment for veterans.22-24 The implications of PD pathology on broader psychosocial functioning and health care needs certify a need for additional research that examines patterns of personality pathology, particularly in veterans outside the VHA.

METHODS

This study aims to enhance understanding of veterans affected by PDs and offer insight and guidance for treatment of these conditions in federal and nonfederal treatment settings. Previous research has been largely limited to VHA care-receiving samples; the longstanding stigma against PDs by the US military and VA may contribute to biased diagnosis and documentation of PDs in these settings. A large sample of veterans receiving community-based mental health care was therefore used to explore aims of the current study. This study specifically examined demographic patterns, diagnostic comorbidity, psychosocial outcomes, and treatment care settings among veterans with and without a PD diagnosis. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that veterans with a PD diagnosis would have more severe mental health comorbidities, poorer psychosocial outcomes, and receive care in higher intensity settings relative to veterans without a diagnosis.

Data for the sample were drawn from the Mental Health Client-Level Data, a publicly available national dataset of nearly 7 million patients who received mental health treatment services provided or funded through state mental health agencies in 2022.25 The analytic sample included about 2.5 million patients for whom veteran status and data around the presence or absence of a PD diagnosis were available. Of these patients, 104,198 were identified as veterans. Veteran patients were identified as predominantly male (63%), White (71%), non-Hispanic (90%), and never married (54%).

Measures

The parent dataset included demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome information reported by treatment facilities to individual state administrative systems for each patient who received services. To protect patient privacy, only nonprotected health information is included, and efforts were made throughout compilation of the parent dataset to ensure patient privacy (eg, limiting detail of information disseminated for public access). Because the parent dataset does not include protected health information, studies using these data are considered exempt from institutional review board oversight.

Demographic information. This study reviewed veteran status, sex, race, ethnicity, age, education, and marital status. Veteran status was defined by whether the patient was aged ≥ 18 years and had previously served (but was not currently serving) in the military. Patients with a history of service in the National Guard or Military Reserves were only classified as veterans if they had been called or ordered to active duty while serving. Sex was operationalized dichotomously as male or female; no patients were identified as intersex, transgender, or other gender identities.

Clinical information. Up to 3 mental health diagnoses were reported for each patient and included the following disorders: personality, trauma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity, stressor, anxiety, conduct, delirium/dementia, bipolar, depressive, oppositional defiant, pervasive developmental, schizophrenia or other psychotic, and alcohol or substance use. Mental health diagnosis categories were generated for the parent dataset by grouping diagnostic codes corresponding to each category. To protect patient privacy, more detailed diagnostic information was not available as part of the parent dataset. Although the American Psychiatric Association recognizes 10 distinct PDs, the exact nature of PD diagnoses was not included within the parent dataset. PD diagnoses were coded to reflect the presence or absence of any such diagnosis.

A substance use problem designation was also provided for patients according to various identification methods, including substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis, substance use screening results, enrollment in a substance use program, substance use survey, service claims information, and other related sources of information. A severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance designation was provided for patients meeting state definitions of these designations. Context(s) of service provision were coded as inpatient state psychiatric hospital, community-based program, residential treatment center, judicial institution, or other psychiatric inpatient setting.

Psychosocial outcome information. Patient employment and residential status were also included in analyses. Each reflected status at the time of discharge from services or end of reporting period; employment status was only provided for patients receiving treatment in community-based programs.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and X2 analyses were used to compare demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome variables between patients with and without PD diagnoses. These analyses were calculated for both the 104,198 veterans and the 2,222,306 nonveterans aged ≥ 18 years in the dataset. Given the sample size, a conservative α of .01 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

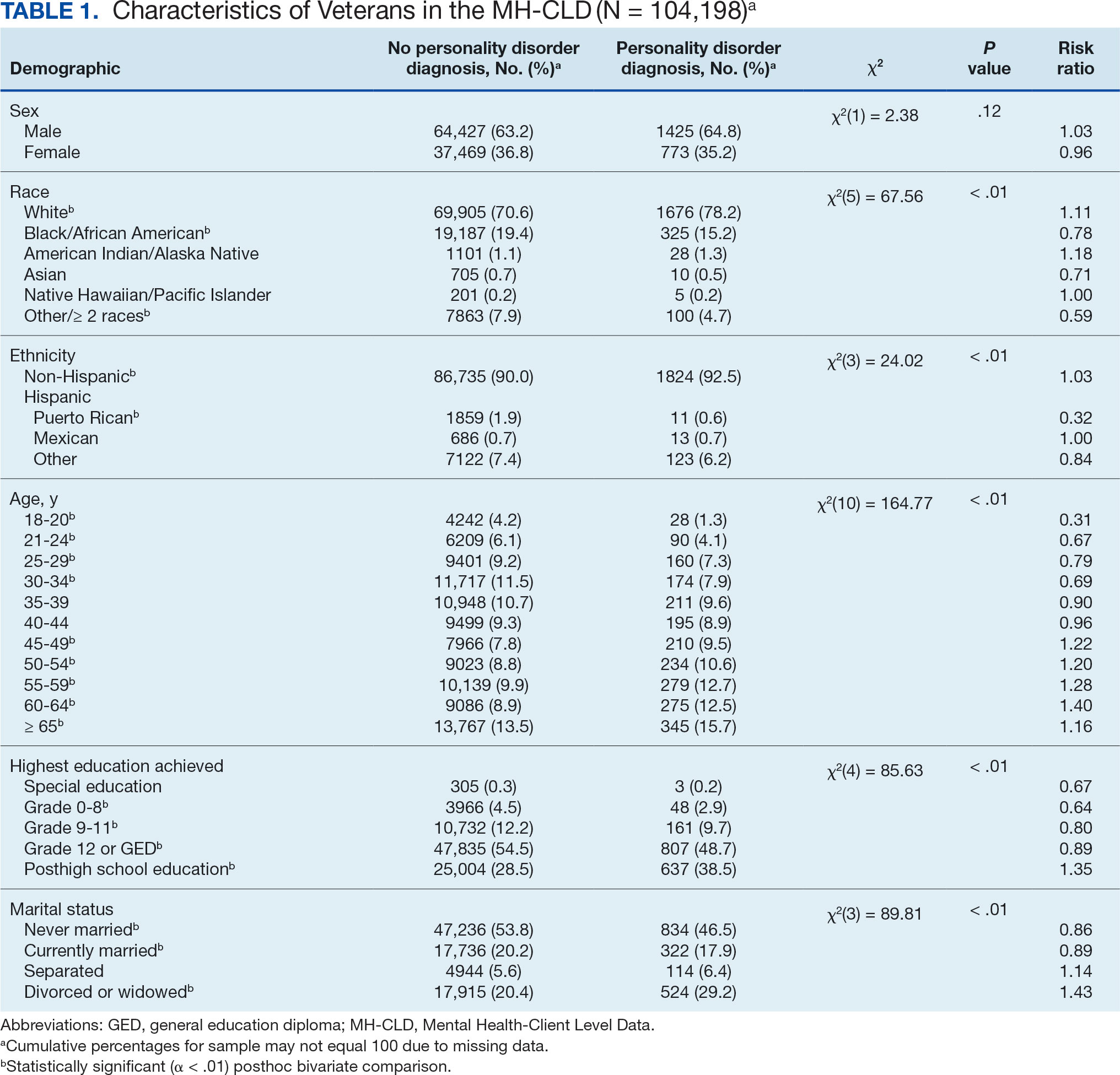

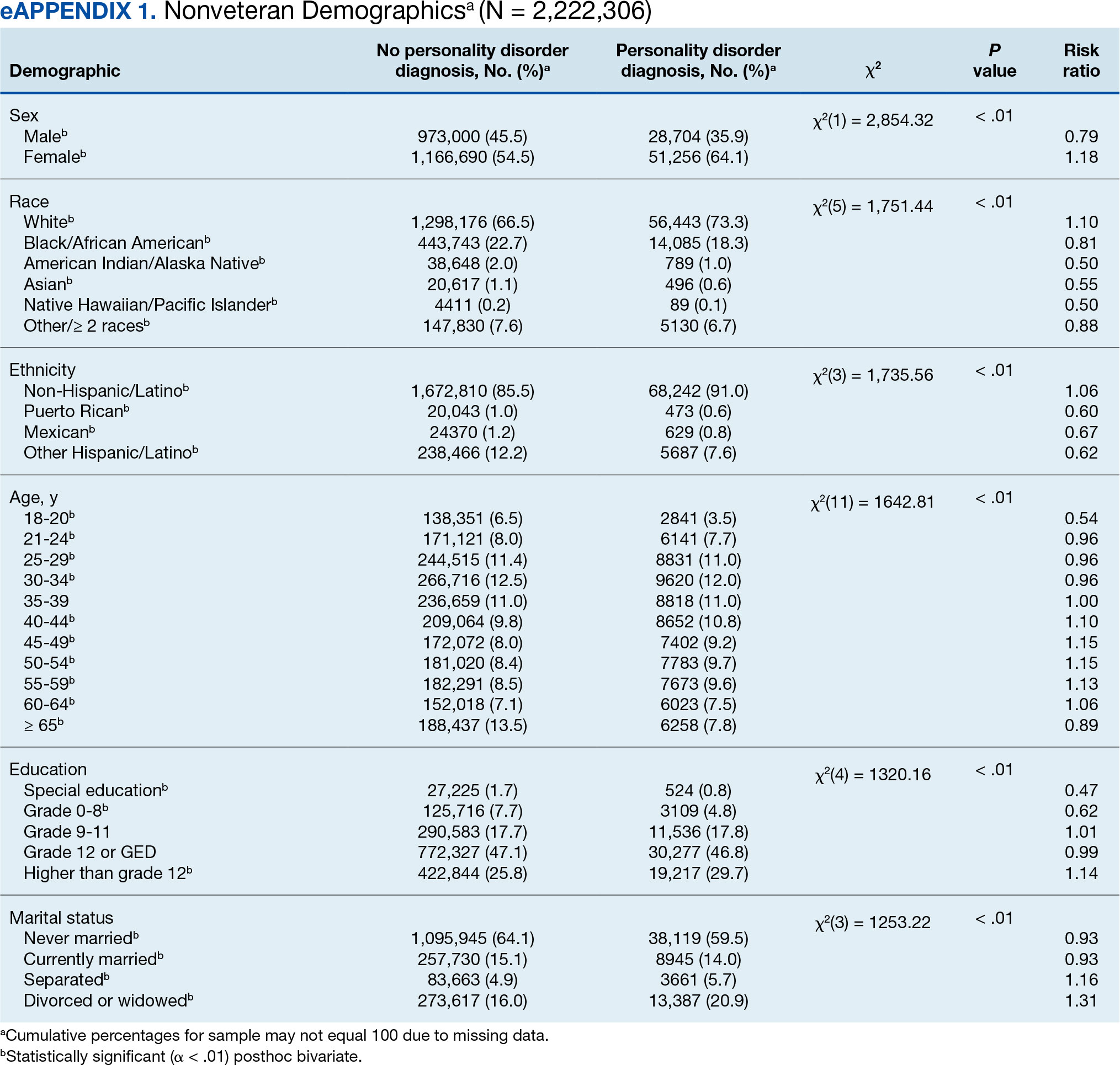

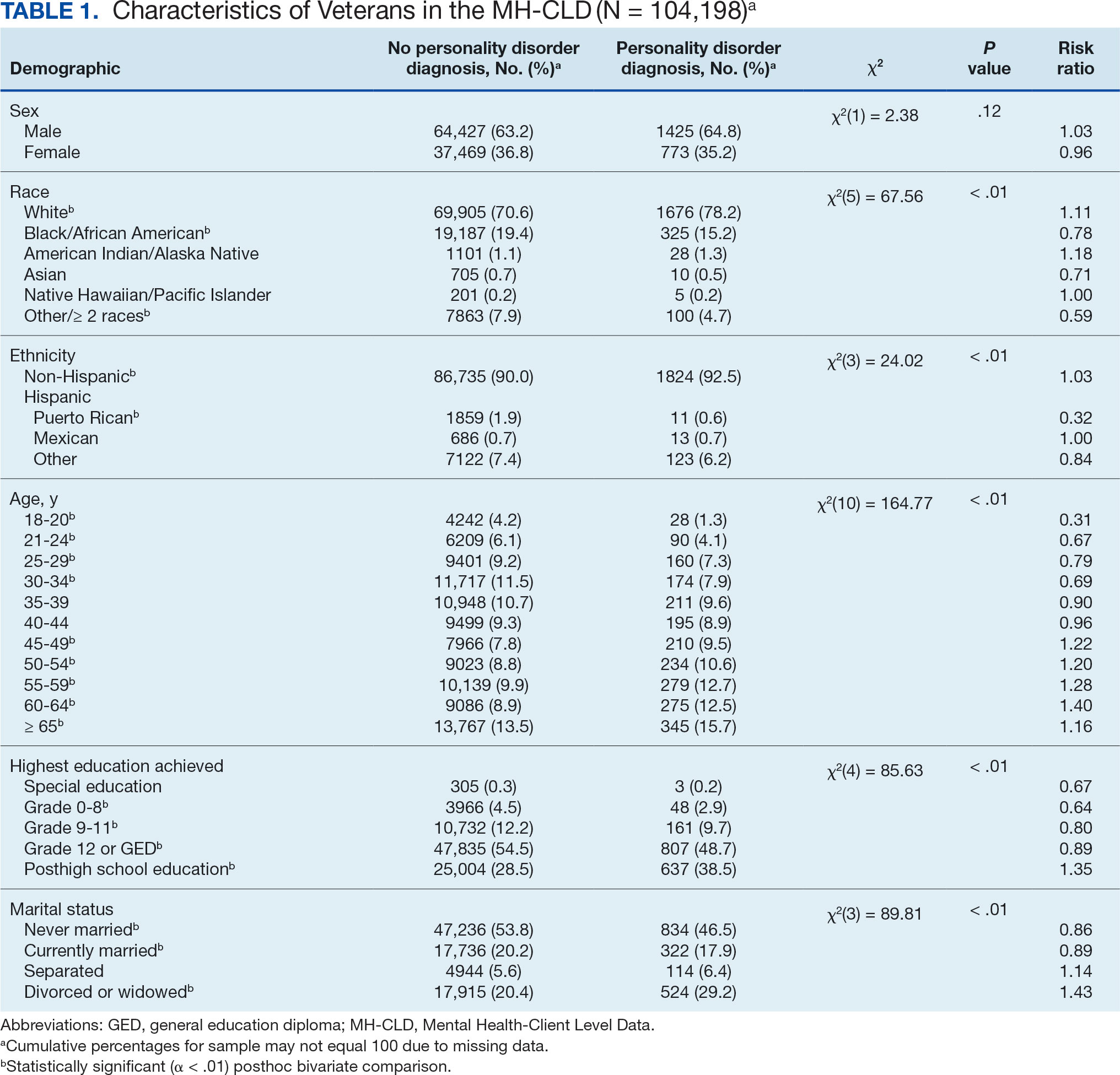

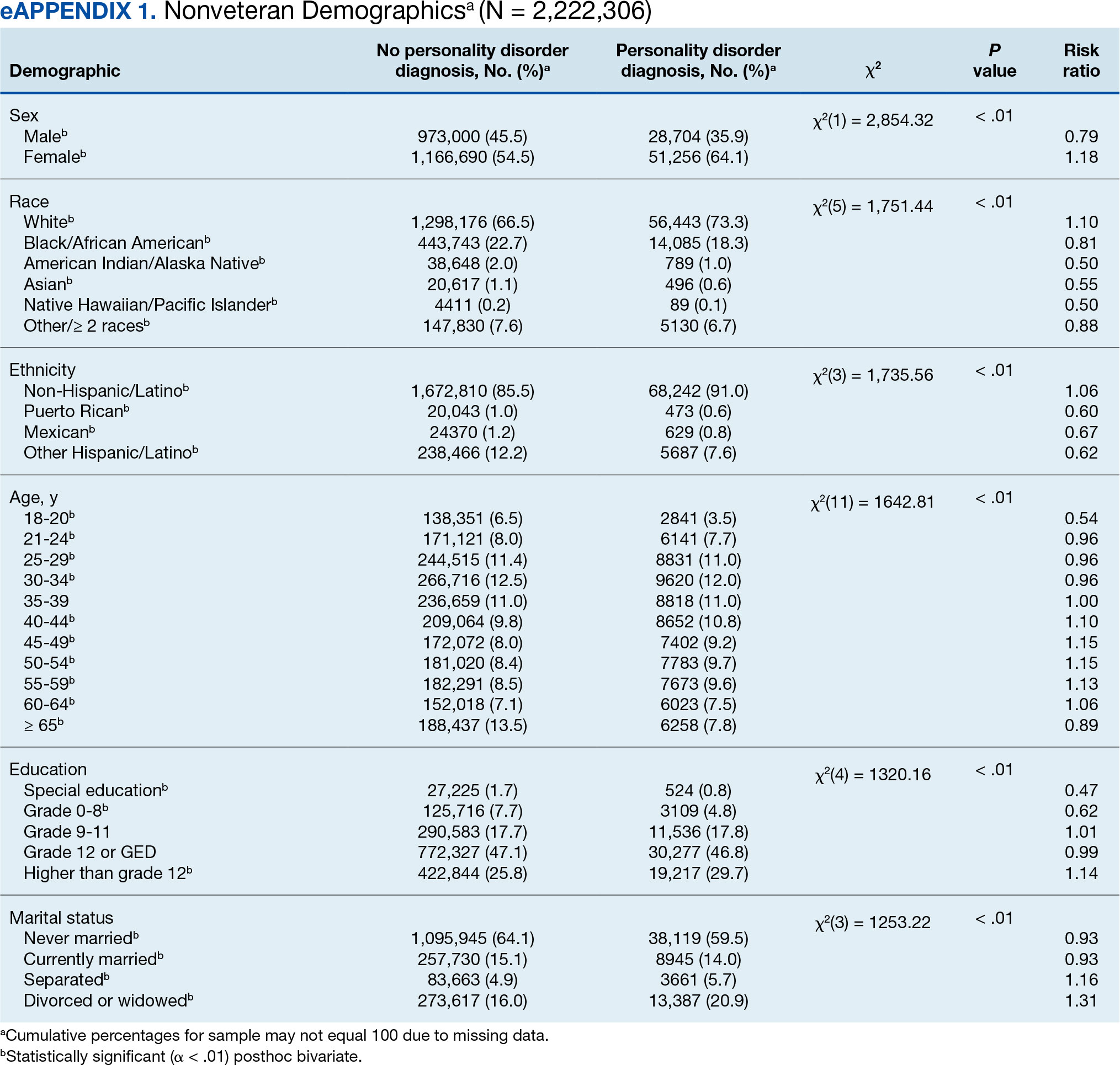

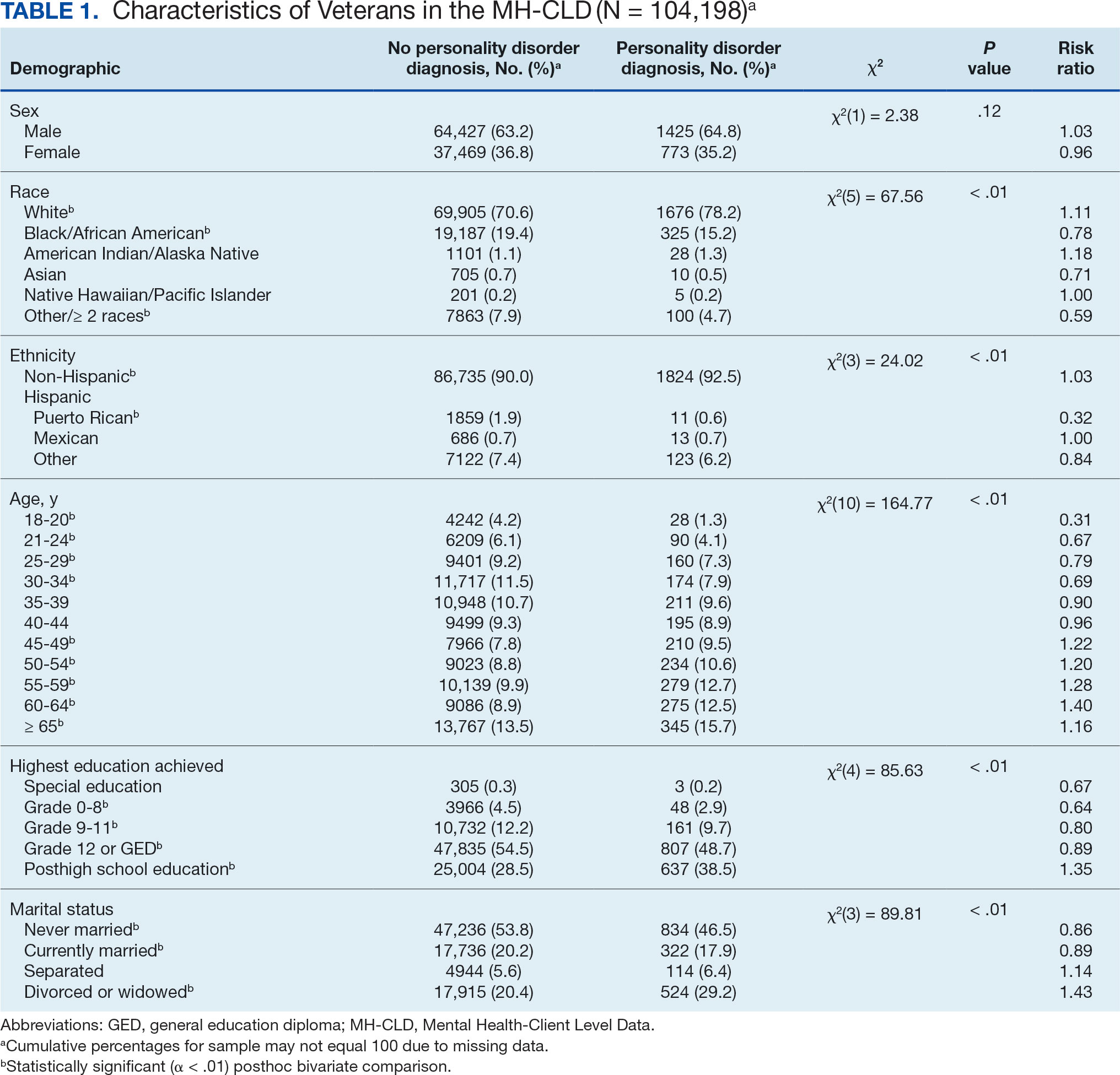

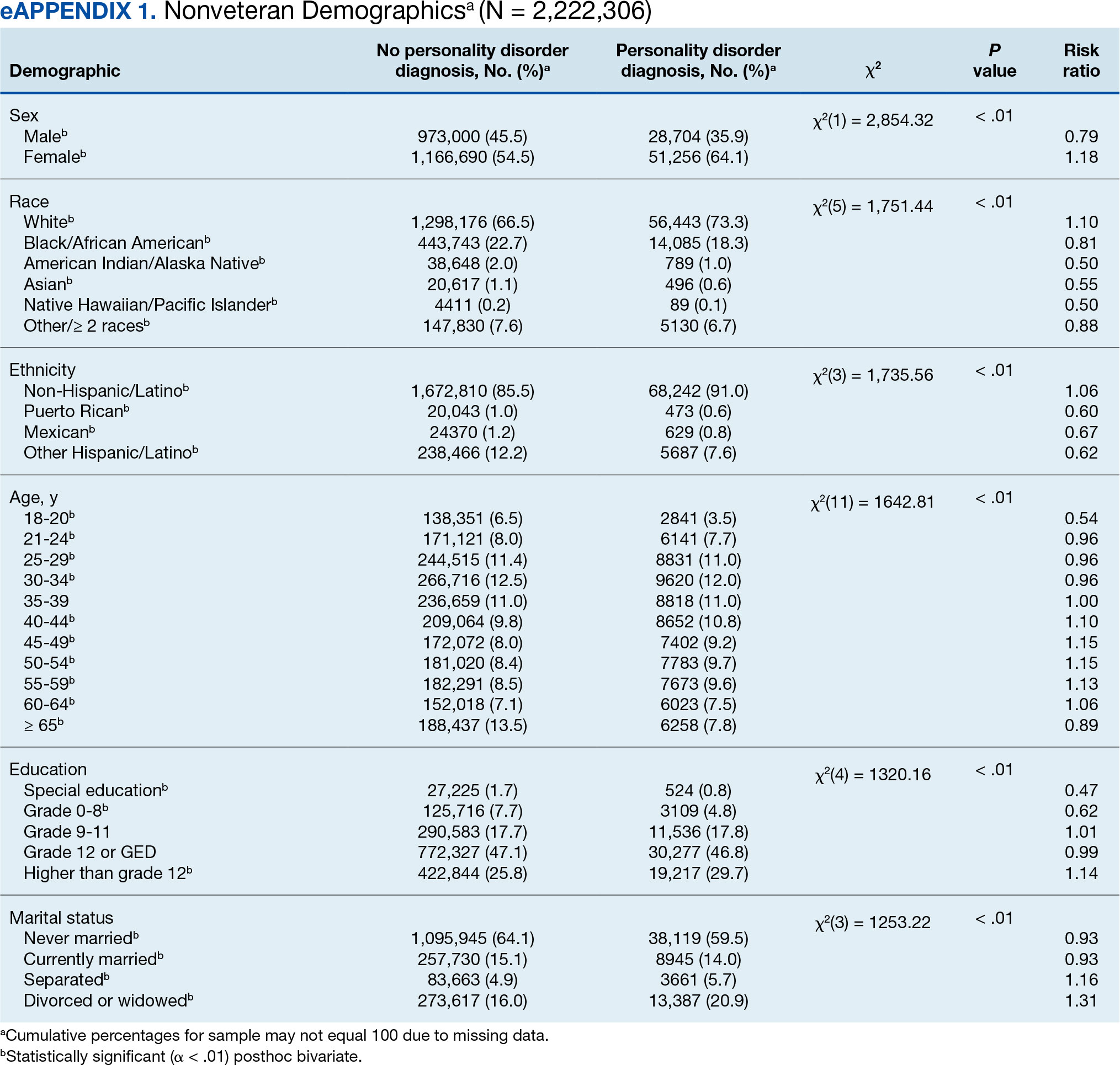

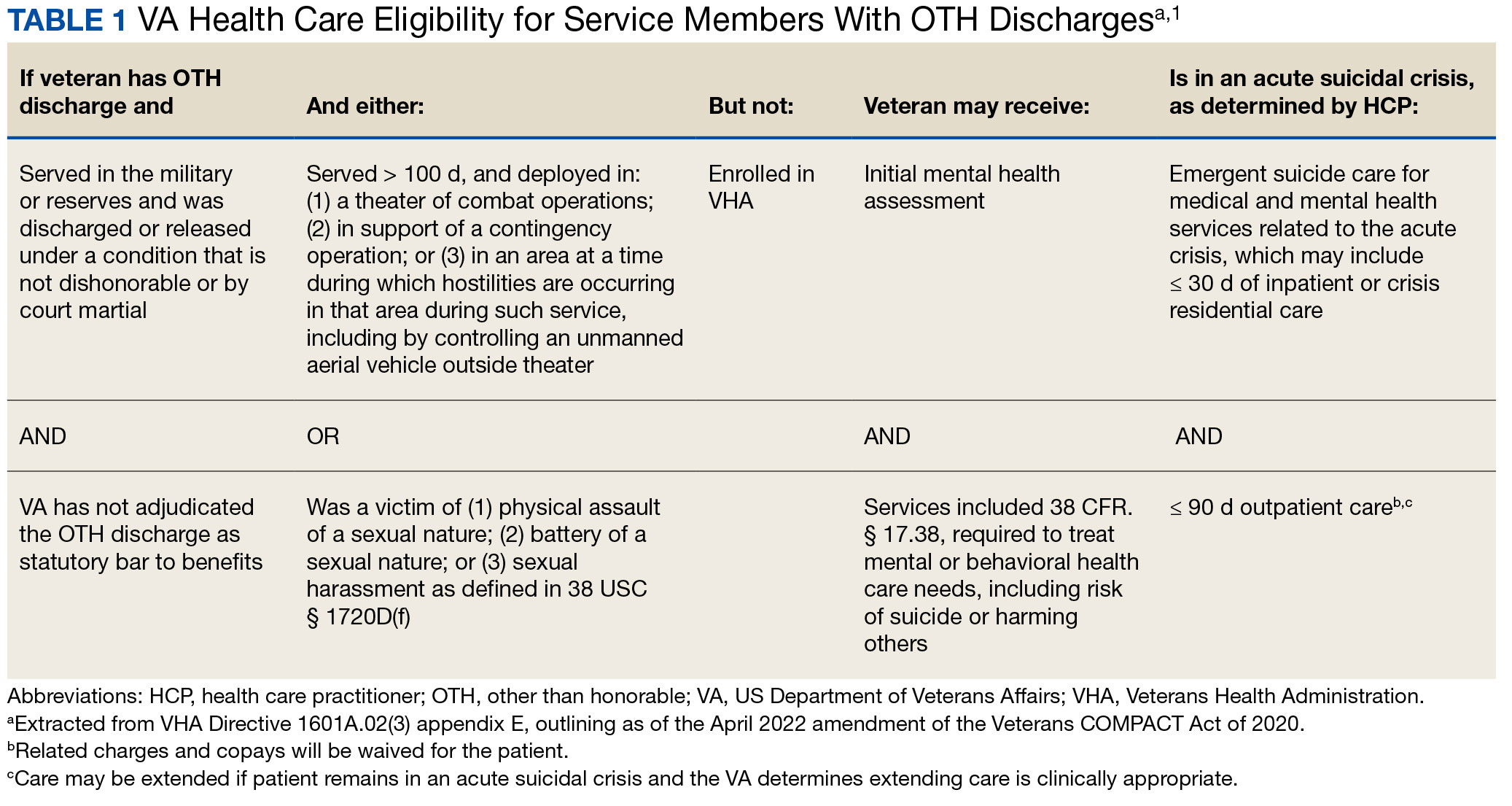

In this sample of persons receiving state-funded mental health care, veterans were significantly less likely than nonveterans to have a documented PD diagnosis (2.1% vs 3.6%, X2 [1] = 647.49; P < .01). PD diagnoses were more common among White (risk ratio [RR], 1.11), non-Hispanic (RR, 1.03) veterans who were in middle to late adulthood (RR, 1.16-1.40), more educated (RR, 1.35), and divorced or widowed (RR, 1.43), and less common among Black/African American (RR, 0.78) or Puerto Rican (RR, 0.32) veterans who were in early adulthood (RR, 0.31-0.79), less educated (RR, 0.64-0.89), and currently married (RR, 0.89) or never married (RR, 0.86). Veteran men and women were equally likely to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 1.03) (Table 1). Among nonveterans, men were less likely than women to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.79), and PD diagnoses were most common among persons in middle adulthood (RR, 1.06-1.15) (eAppendix 1).

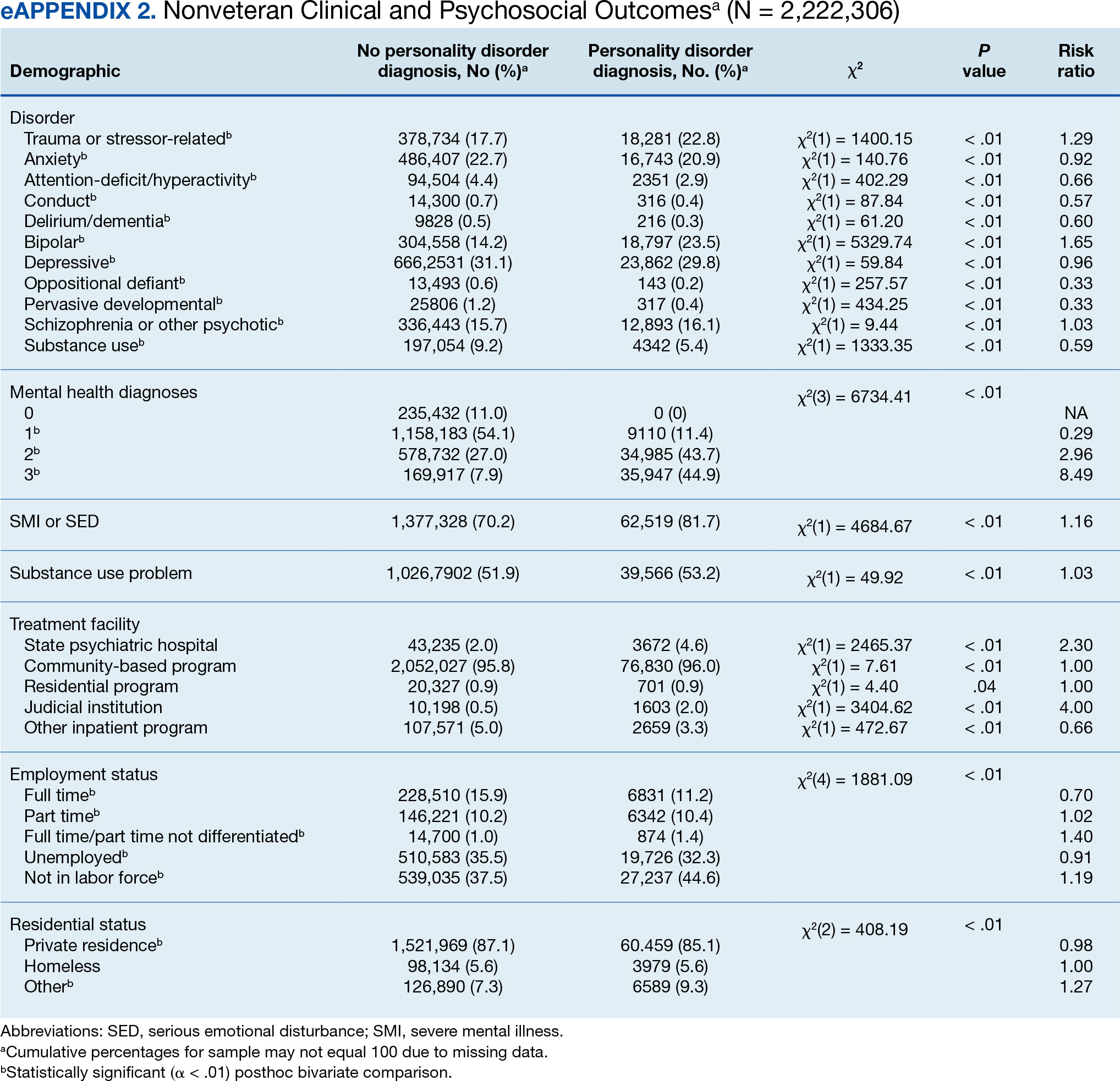

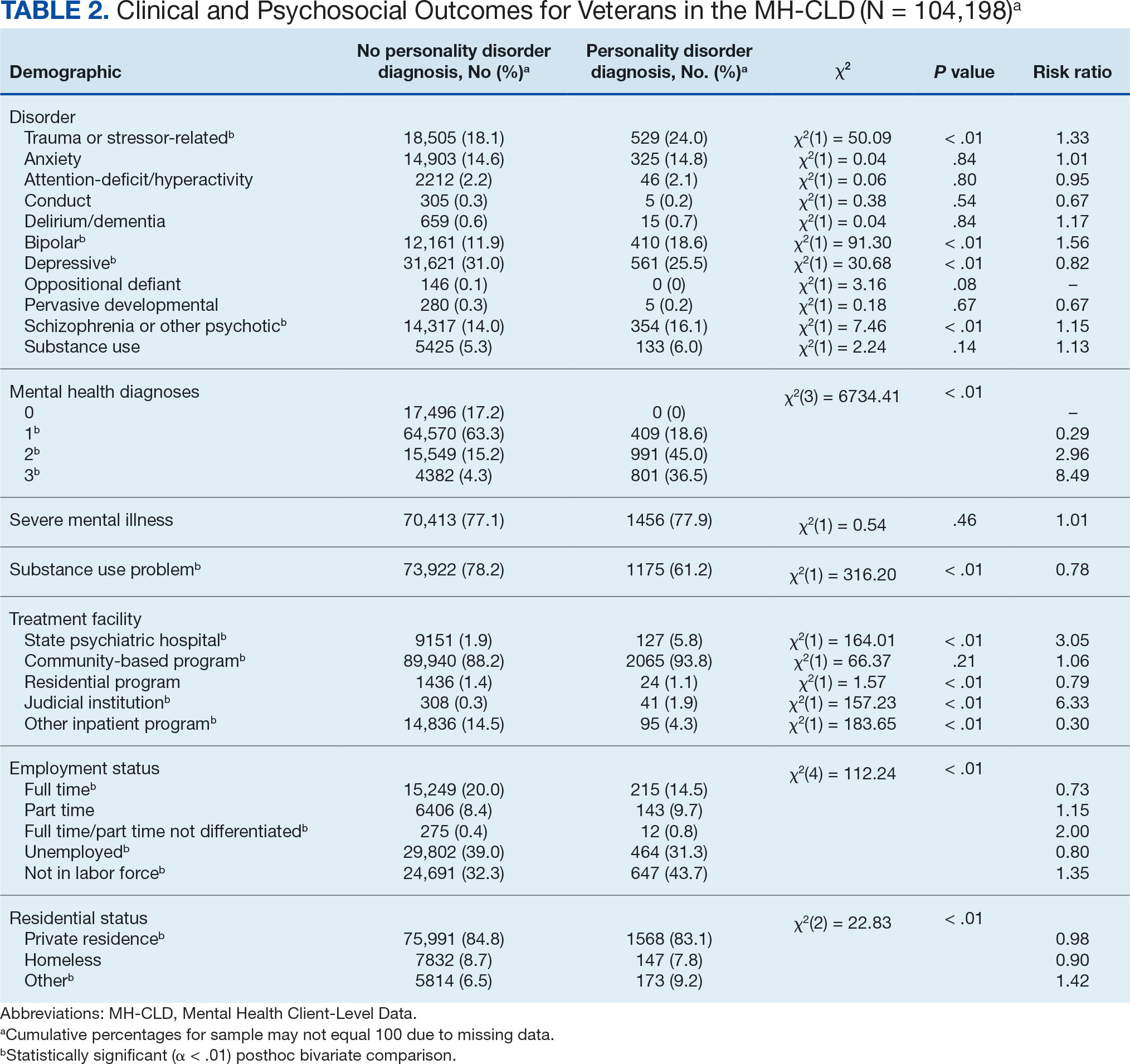

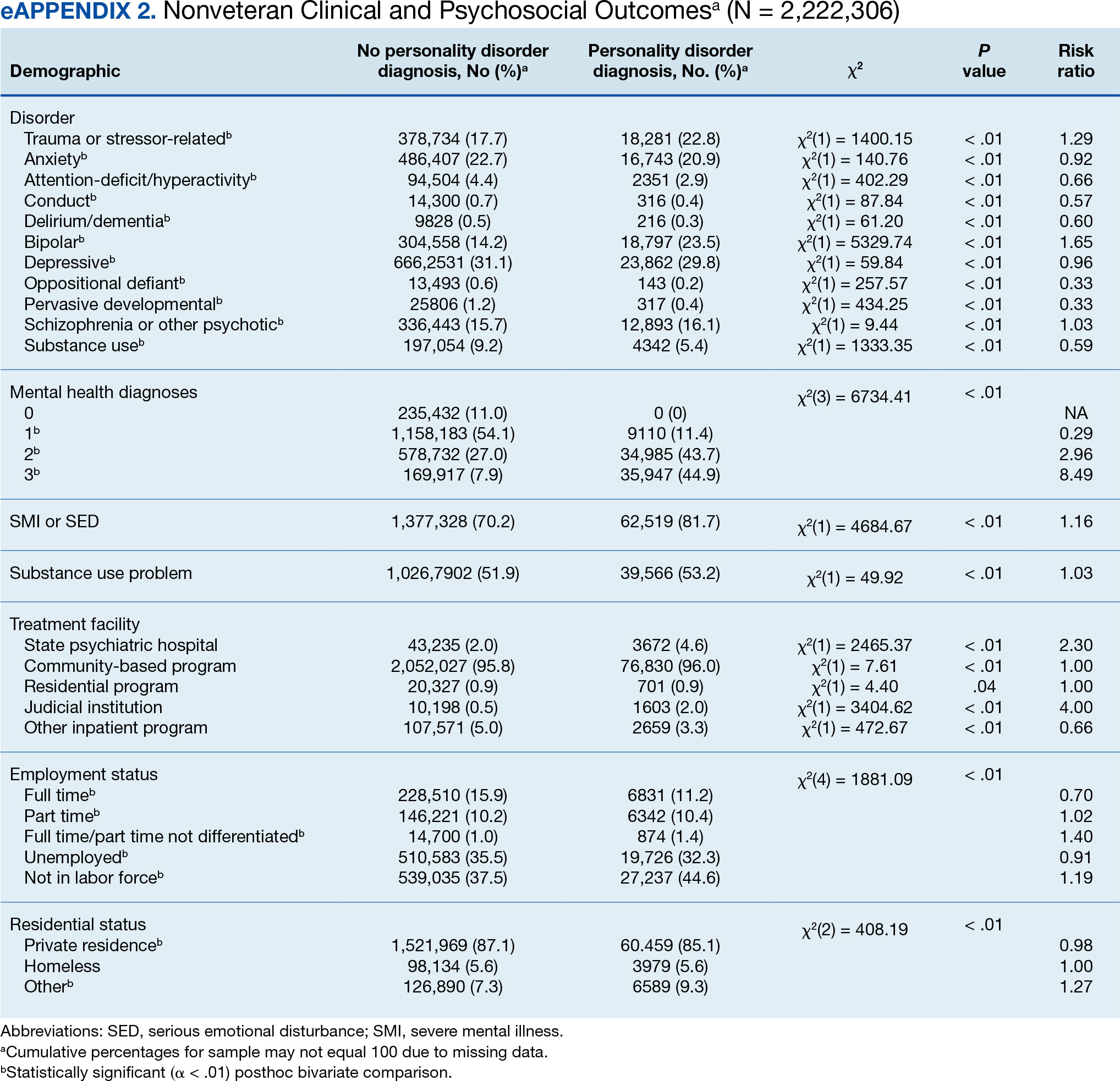

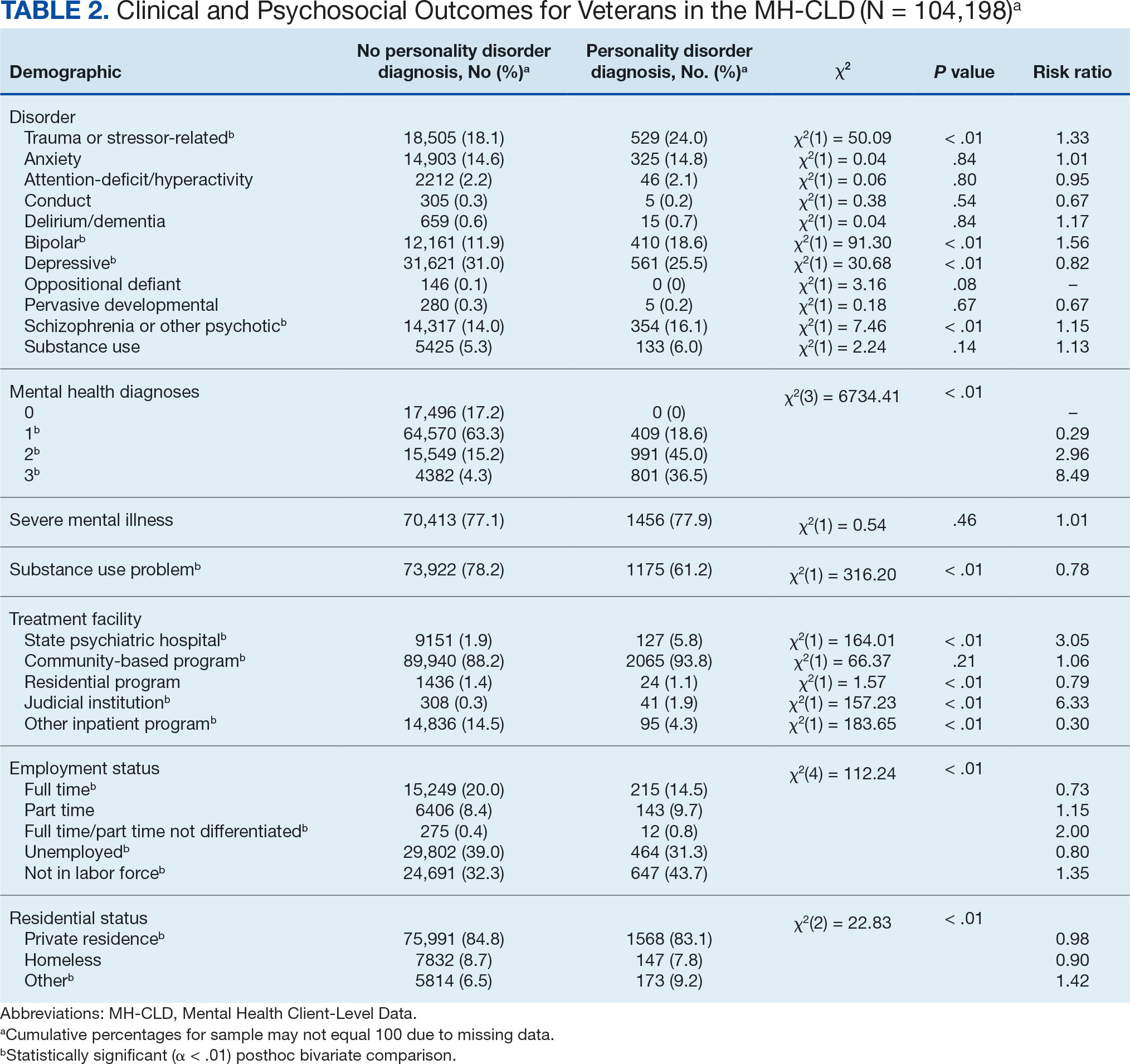

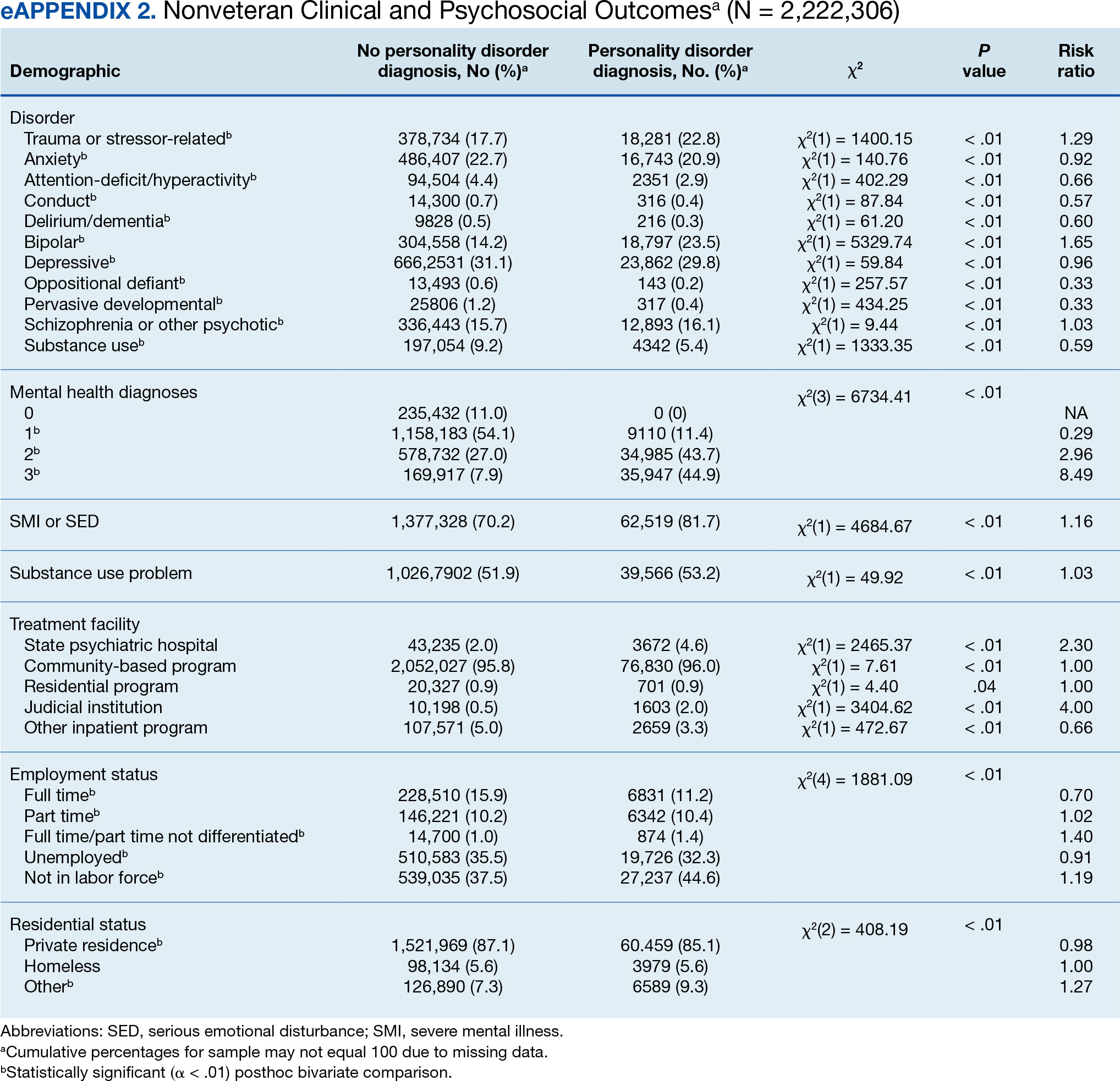

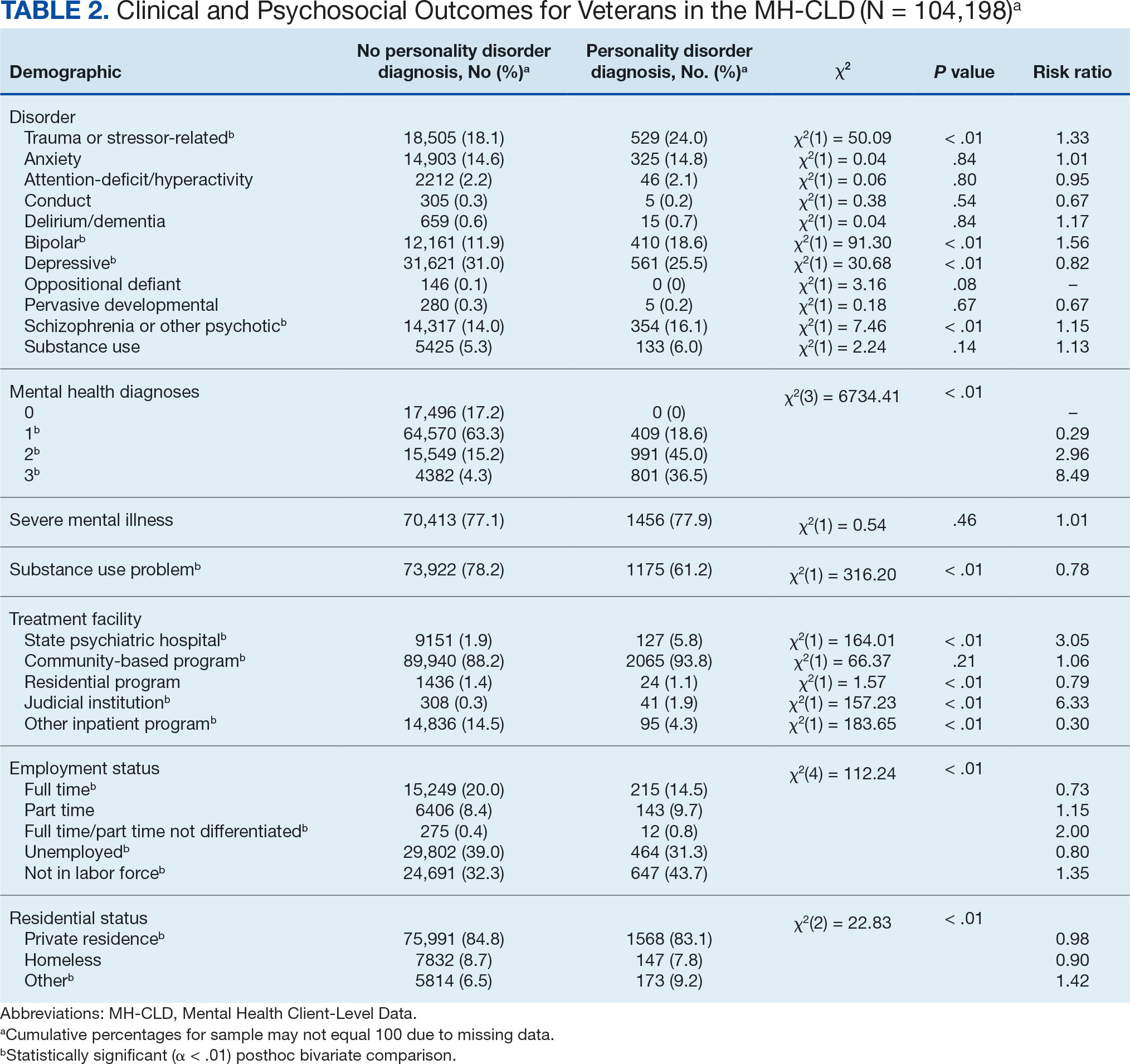

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were more likely than those without a diagnosis to have more diagnoses (RR, 2.96-8.49) and to have comorbid trauma or related stressor (RR, 1.33), or bipolar (RR, 1.56) or psychotic (RR, 1.15) disorder diagnoses, but less likely to have comorbid depressive disorder (RR, 0.82). Although veterans with and without a PD diagnosis were similarly likely to have a comorbid SUD (RR, 1.13), those with a PD diagnosis were significantly less likely to be assigned a substance use problem designation (RR, 0.78). PD diagnosis was also more common among veterans who received services in state psychiatric hospitals (RR, 3.05), community-based clinics (RR, 1.06), and judicial institutions (RR, 6.33) and less common among those who received services in other psychiatric inpatient settings (RR, 0.30). No differences were observed for residential treatment settings (RR, 0.79). Among nonveterans, a PD diagnosis was associated with slightly greater odds of a substance use designation (RR, 1.03) (eAppendix 2).

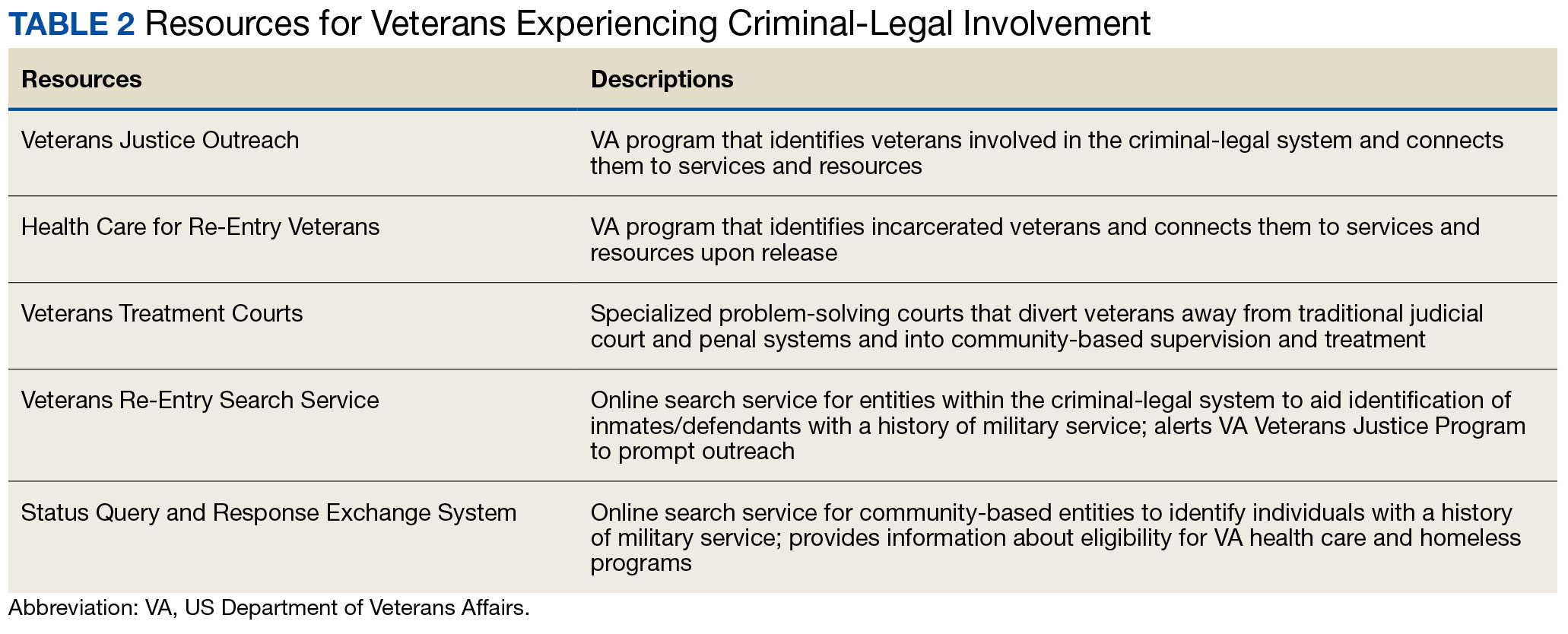

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also less likely to have full-time employment (RR, 0.73) and more likely to have undifferentiated employment (RR, 2.00) or to be removed from the labor force (RR, 1.35). Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also more likely to reside in nontraditional living conditions (RR, 1.42) and less likely to be residing in a private residence (RR, 0.98), compared with those without PD diagnosis. The rates of homelessness were similar for veterans with and without a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.90) (Table 2). These patterns were similar among nonveterans.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the rate and correlates of PD diagnosis among a large, community-based sample of veterans receiving state-funded mental health care. About 2% of veterans in this sample had a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, with higher education, divorced or widowed, also diagnosed with trauma-related, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in state psychiatric hospital, community-based clinic, or judicial system settings.

The observed rate of PD diagnosis in this study aligns with what is typically observed in VHA EHRs.8,18,19 However, the rate is notably lower than prevalence estimates for psychiatric outpatient settings (about 50%) and in meta-analyses of prevalence among veterans (0.8%-23% for each of the 10 PDs).4,17,26 Longstanding stigma against PDs may contribute to underdiagnosis. For example, many clinicians are concerned that documentation or disclosure of a PD will interfere with the patient’s ability to access treatment due to stigma and discrimination.27,28 These fears are not unfounded; even among clinicians, PDs are commonly considered untreatable, and many individuals with PDs are denied access to evidence-based treatments due to the diagnosis.29 In a 2016 survey of community psychiatrists, nearly 1 in 4 reported that they avoid taking patients with a borderline PD diagnosis in their caseloads.28 To date, no studies have been conducted to explore clinicians’ willingness to accept patients with other PDs or, specifically, among veterans.

Despite such widespread stigma, research suggests clinicians' negative attitudes toward PDs can be decreased through antistigma campaigns.30 However, it remains unclear if such efforts also contribute to an increase in clinicians’ willingness to document PD diagnoses. Without accurate identification and documentation, the field’s understanding of PDs will remain limited.

In the current study, veterans with PD diagnoses tended to present with more complex and severe psychiatric comorbidities compared to veterans without such diagnoses. Observed comorbidity of PDs (particularly borderline PD) with trauma-related and bipolar disorders is well established.8 Conversely, co-occurring personality and psychotic disorders—which comprise 16% of veterans with a PD diagnosis in the sample in this study—are not consistently examined in the literature. A 2022 examination of veterans receiving VHA care suggested 12% and 13% of those with a PD diagnosis documented in their EHR also had documented schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, respectively. PD diagnoses were associated with 6.88- and 9.80-fold increases in risk for comorbid schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder diagnoses, respectively.8 Similarly, a recent longitudinal study of nearly 2 million Swedish individuals suggested borderline PD is specifically associated with a > 24-times greater risk of having a comorbid psychotic disorder.31 It is therefore possible that the comorbidity between personality and psychotic disorders is quite common despite its relative lack of attention in empirical research.

Veterans with PD diagnoses in this study were also more likely to experience substandard housing, employment challenges, and receive treatment through judicial institutions than those without a PD diagnosis. Such findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the substantial psychosocial challenges associated with PD diagnosis, even after controlling for comorbid conditions.7,9 Veterans with PDs may benefit from specialized case management and support to facilitate stable housing and employment and to mitigate the risk of judicial involvement. Some research suggests veterans with PDs may be less likely to gain competitive employment after participating in VA therapeutic and supportive employment services programs, suggesting standard programming may be less suitable for this population.32 Similarly, other research suggests individuals with PDs may benefit more from specialized, intensive services than standard clinical case management.33 Future research may therefore benefit from clarifying the degree to which adaptations to standard programming could yield beneficial effects for persons with PD diagnoses.

Implications

Cumulatively, the results of this study attest to the necessity for transdiagnostic treatment planning that includes close collaboration between psychotherapeutic, pharmacological, and case management services. Some psychotherapy models for PDs, such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which includes a combination of group skills training, individual therapy, as-needed phone coaching, and therapist consultation, may be successfully adapted to include this collaboration.34-36 However, implementation of such comprehensive programming often requires extensive clinician training and coordination of resources, which poses implementation challenges.37-39 In 2021, the VHA began large-scale implementation of PD-specific psychotherapy for veterans with recent suicidal self-directed violence and borderline PD, including DBT, though to date results remain unclear.40 Generalist approaches, such as good psychiatric management (GPM), which emphasizes emotional validation, practical problem solving, realistic goal setting, and relationship functioning within the context of standard care appointments, may be more easily implemented in community care settings due to lesser training and resource requirements and can also be adapted to include needed elements of care coordination.41,42 Both DBT and GPM were initially developed for the treatment of borderline PD. Although DBT has also demonstrated some effectiveness in the treatment of antisocial PD, potential applications of DBT and GPM to other PDs remain largely underdeveloped.43-46

There are no widely accepted medications for the treatment of PDs. Pharmacotherapy for these conditions typically consists of individualized approaches informed by personal experience that attempt to balance targeting of specific symptoms while minimizing polypharmacy and potential risks (eg, overdose or addiction).47,48 Despite this, pharmacotherapy is often considered a necessary component in the treatment of bipolar and psychotic disorders, both common comorbidities of PDs found in veterans in this study.49,50 Careful consideration of complex comorbidities and pharmacotherapy needs is warranted in the treatment of veterans with PDs. Future research may benefit from clarifying clinical guidelines around pharmacotherapy, particularly for observed comorbidities of PDs to trauma, bipolar, and psychotic disorders.

It is important to note the discrepancies in the results of this study surrounding patient substance use. The results suggest a negligible or inverse association between the likelihood of a PD diagnosis and difficulties with substance use among the veterans in this study. However, the unexpectedly low rate of SUD diagnoses (< 6%) suggests that they were likely underdocumented. Research suggests a strong association between personality and SUDs in both veteran and civilian samples.6,51 Results suggesting a lower prevalence of substance use difficulties among treatment-seeking veterans with PDs should be interpreted with great caution.

Demographically, PD diagnoses were more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, and aged ≥ 45 years, and less common among veterans who were Black/ African American, mixed/unspecified race, Puerto Rican or other non-Mexican Hispanic ethnicity, or aged < 35 years. No significant sex-based differences were observed. These patterns are consistent with research suggesting individuals who identify as Black may be less likely than individuals who identify as White to report PD symptoms, meet criteria for a PD, and have a PD diagnosed even when it is warranted.52

The findings observed in this study with respect to age, however, are notably inconsistent with the literature. Previous research typically suggests a negative association between age and PD pathology; however, a 2020 review of PDs in older adults by Penders et al suggests a prevalence of 11% to 15% in this population.53,54 Research into PDs most often focuses on adolescent and early adulthood developmental periods, limiting insight into the phenomenology of PDs in middle to late adulthood.55 Further, most research into PDs among geriatric populations has focused on psychometric assessment rather than practical treatment guidance.54 However, in this study, elevated risk for PD diagnoses was salient throughout middle to late adulthood among veterans; similar, albeit less pronounced patterns were also observed for elevated risk of PD diagnosis in middle adulthood among nonveterans. Such findings suggest clarifying the phenomenology and treatment needs of individuals with PDs in middle to late adulthood may have particularly salient implications for the mental health care of veterans affected by these conditions. As the veteran population advances in age, these needs will present unique challenges if health care systems are unprepared to effectively address them.

Limitations

This study is characterized by several strengths, most notably its use of a large dataset recently collected on a national scale. Few studies outside of the VHA system include samples of > 100,000 treatment-seeking veterans collected on a national scale. Nevertheless, results should be understood within the context of several methodological limitations. However, the dataset was limited to the first 3 diagnoses documented in patients’ EHRs, and many patients had no listed diagnoses. Patients with complex comorbidities may have > 3 diagnoses; for these individuals, data provided an incomplete picture of clinical presentation. This is especially relevant for individuals with PDs, who tend to meet criteria for a range of comorbid conditions.8,10 The now dated practice of listing PDs on Axis II also increases the chance of clinicians listing PDs after conditions traditionally listed on Axis I (eg, major depressive disorder) in patient charts.56 This study’s inclusion of only the first 3 listed diagnoses likely underestimated true PD diagnosis prevalence.

The results of this study must be interpreted as reflecting the prevalence and correlates of receiving a PD diagnosis rather than meeting diagnostic criteria for a PD. Relatedly, PD diagnoses were reported as a single construct, limiting insight into prevalence and correlates of individual PD diagnoses (eg, borderline vs paranoid PDs). Meta-analyses estimates suggest PD prevalence among veterans is likely much higher than observed in this study.17 Stigma continues to discourage clinicians from documenting and disclosing PD diagnoses even when warranted.27,28 Continued research should aim to clarify conditions (eg, patient presentation, stigma, or institutional culture) contributing to documentation of PD diagnoses. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, results cannot speak to longitudinal treatment outcomes or prognosis of persons receiving a PD diagnosis.

Despite its large sample size and national representation, the sampling strategy of this study could have contributed to idiosyncrasies in the dataset. Restriction of data to the persons receiving state-funded mental health services introduces a notable bias to the composition of the sample, which is likely comprised of a disproportionately high number of Medicaid recipients, students, and individuals with chronic illnesses and underrepresentation of persons who pay for mental health services using private insurance or private pay arrangements. As such, although socioeconomic information was not provided within this dataset, one can presume a generally lower socioeconomic status among study participants compared to the community at large. This study also included a proportionally small sample of veterans (3.6% compared to about 6.2% in the broader US population), suggesting veterans may have been underrepresented or underidentified in surveyed mental health care settings.57 This study also did not include data around service in active-duty military, national guard, or military reserves; a greater proportion of the sample likely had a history of military service than was represented by veteran status designation. Further, the proportionally high sample of individuals with severe mental illness suggests a likely overrepresentation of such conditions in surveyed settings.

Institutional differences in the practice of assigning diagnoses likely limited statistical power to detect potentially meaningful associations and effects. Structural influences, such as stigma and institutional culture, may have notable effects on documentation practices, particularly for PDs. Future research should aim to replicate observed associations using more controlled diagnostic procedures.

Lastly, even with the use of a more conservative α and a focus on effect sizes to guide interpretation of results, use of multiple bivariate analyses can be presumed to have increased the likelihood of type I error. Given the limited prior research in this area, an exploratory approach to statistical analysis was considered warranted to maximize opportunity for identifying areas in need of additional empirical attention. Continued research using more conservative statistical approaches (eg, multivariate analyses) is needed to determine replicability and generalizability of observed results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of PD diagnoses in a national sample of veterans receiving community-based, state-funded mental health care. About 2% received a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses most common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, also diagnosed with trauma-based, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in a state psychiatric hospital or judicial system setting. The results attest to a necessity for transdiagnostic treatment planning and care coordination for this population, with particular attention to psychosocial stressors.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

- Hastrup LH, Jennum P, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J, Simonsen E. Societal costs of borderline personality disorders: a matched-controlled nationwide study of patients and spouses. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(5):458-467. doi:10.1111/acps.13094

- Sveen CA, Pedersen G, Ulvestad DA, Zahl KE, Wilberg T, Kvarstein EH. Societal costs of personality disorders: a cross-sectional multicenter study of treatment-seeking patients in mental health services in Norway. J Clin Psychol. 2023;79(8):1752-1769. doi:10.1002/jclp.23504

- Beckwith H, Moran PF, Reilly J. Personality disorder prevalence in psychiatric outpatients: a systematic literature review. Personal Ment Health. 2014;8(2):91-101. doi:10.1002/pmh.1252

- Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc. 2017.09.001

- Edwards ER, Barnes S, Govindarajulu U, Geraci J, Tsai J. Mental health and substance use patterns associated with lifetime suicide attempt, incarceration, and homelessness: a latent class analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. veterans. Psychol Serv. 2021;18(4):619-631. doi:10.1037/ser0000488

- Moran P, Romaniuk H, Coffey C, et al. The influence of personality disorder on the future mental health and social adjustment of young adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):636-645. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30029-3

- Nelson SM, Griffin CA, Hein TC, Bowersox N, McCarthy JF. Personality disorder and suicide risk among patients in the Veterans Affairs health system. Personal Disord. 2022;13(6):563-571. doi:10.1037/per0000521

- Skodol AE. Impact of personality pathology on psychosocial functioning. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21;33-38. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.006

- Tyrer P, Reed GM, Crawford MJ. Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):717-726. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61995-4

- Fitzpatrick S, Goss S, Di Bartolomeo A, Varma S, Tissera T, Earle E. Follow the money: is borderline personality disorder research underfunded in Canada? Can Psychol. 2024;65(1):46-57. doi:10.1037/cap0000375

- Zimmerman M, Gazarian D. Is research on borderline personality disorder underfunded by the National Institute of Health? Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(3):941-944. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.021

- Leroux TC. U.S. military discharges and pre-existing personality disorders: a health policy review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(6):748-755. doi:10.1007/s10488-014-0611-z

- Monahan MC, Keener JK. Fitness-for-duty evaluations. In Kennedy CH, Zillmer EA, eds. Military Psychology: Clinical and Operational Applications. 2nd ed. Guilford Publications; 2012:25-49.

- Hearing Before the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 111th Congress 2nd Sess (2010). Personality disorder discharges: impact on veterans benefits. Accessed March 4, 2025. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg61755/html/CHRG-111hhrg61755.htm

- Ader M, Cuthbert R, Hoechst K, Simon EH, Strassburger Z, Wishnie M. Casting troops aside: the United States military’s illegal personality disorder discharge problem. Vietnam Veterans of America. March 2012. Accessed February 28, 2025. https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/Clinics/VLSC_CastingTroopsAside.pdf

- Edwards ER, Tran H, Wrobleski J, Rabhan Y, Yin J, Chiodi C, Goodman M, Geraci J. Prevalence of personality disorders across veteran samples: A meta-analysis. J Pers Disord. 2022;36(3):339-358. doi:10.1521/ pedi.2022.36.3.339

- Holliday R, Desai A, Edwards E, Borges L. Personal i ty disorder diagnosis among just ice -involved veterans: an investigation of VA-using veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211(5):402-406 doi:10.1097/ NMD.0000000000001627

- McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935-1942. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302737

- Liu Y, Chen C, Zhou Y, Zhang N, Liu S. Twenty years of research on borderline personality disorder: a scientometric analysis of hotspots, bursts, and research trends. Front Psych. 2024;15:1361535. doi:10.3389/ fpsyt.2024.1361535

- Williams R, Holliday R, Clem M, Anderson E, Morris EE, Surís A. Borderline personality disorder and military sexual trauma: analysis of previous traumatization and current psychiatric presentation. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32(15):2223-2236. doi:10.1177/0886260515596149

- Holder N, Holliday R, Pai A, Surís A. Role of borderline personality disorder in the treatment of military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive processing therapy. Behav Med. 2017;43(3):184-190. doi:10.1080/08964289.2016.1276430

- Ralevski E, Ball S, Nich C, Limoncelli D, Petrakis I. The impact of personality disorders on alcohol-use outcomes in a pharmacotherapy trial for alcohol dependence and comorbid Axis I disorders. Am J Addict. 2007;16(6):443- 449. doi:10.1080/10550490701643336

- Walter KH, Bolte TA, Owens GP, Chard KM. The impact of personality disorders on treatment outcome for veterans in a posttraumatic stress disorder residential treatment program. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):576-584. doi:10.1007/s10608-011-9393-8

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. Mental health client-level data (MH-CLD), 2022. Accessed February 28, 2025. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/mental-health-client-level-data-2022-mh-cld-2022-ds0001

- Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1911-1918. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1911

- Campbell K, Clarke KA, Massey D, Lakeman R. Borderline personality disorder: To diagnose or not to diagnose? That is the question. Int J Mental Health Nurs. 2020;29(5):972-981. doi:10.1111/inm.12737

- Sisti D, Segal AG, Siegel AM, Johnson R, Gunderson J. Diagnosing, disclosing, and documenting borderline personality disorder: a survey of psychiatrists’ practices. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(6):848-856. doi:10.1521/ pedi_2015_29_228

- Klein P, Fairweather AK, Lawn S. Structural stigma and its impact on healthcare for borderline personality disorder: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2022;16(1):48. doi:10.1186/s13033-022-00558-3

- Knaak S, Szeto AC, Fitch K, Modgill G, Patten S. Stigma towards borderline personality disorder: effectiveness and generalizability of an anti-stigma program for healthcare providers using a pre-post randomized design. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2015;2:9. doi:10.1186/s40479-015-0030-0

- Tate AE, Sahlin H, Liu S, et al. Borderline personality disorder: associations with psychiatric disorders, somatic illnesses, trauma, and adverse behaviors. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2514-2521. doi:10.1038/s41380- 022-01503-z

- Abraham KM, Yosef M, Resnick SG, Zivin K. Competitive employment outcomes among veterans in VHA Therapeutic and Supported Employment Services programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(9)938-946. doi:10.1176/appi. ps201600412

- Frisman LK, Mueser KT, Covell NH, et al. Use of integrated dual disorder treatment via Assertive Community Treatment versus clinical case management for persons with co-occurring disorders and antisocial personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(11):822-828. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181beac52

- Edwards ER, Kober H, Rinne GR, Griffin SA, Axelrod S, Cooney EB. Skills]homework completion and phone coaching as predictors of therapeutic change and outcomes in completers of a DBT intensive outpatient programme. Psychol Psychother. 2021;94(3):504-522. doi:10.1111/papt.12325

- Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67(1):13-26. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):475-482.doi:10.1001 /jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

- Carmel A, Rose ML, Fruzzetti AE. Barriers and solutions to implementing dialectical behavior therapy in a public behavioral health system. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(5):608-614. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0504-6

- Decker SE, Matthieu MM, Smith BN, Landes SJ. Barriers and facilitators to dialectical behavior therapy skills groups in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2024;189(5-6):1055-1063. doi:10.1093/milmed/ usad123

- Landes SJ, Rodriguez AL, Smith BN, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and benefits of implementation of dialectical behavior therapy in routine care: results from a national program evaluation survey in the Veterans Health Administration. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(4):832-844. doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0465-5

- Walker J, Betthauser LM, Green K, Landes SJ, Stacy M. Suicide Prevention 2.0 Clinical Telehealth Program: Evidence- Based Treatment in the Veterans Health Administration. April 28, 2024. Accessed February 28, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFsDzkg0SR0

- Gunderson J, Masland S, Choi-Kain L. Good psychiatric management: a review. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:127- 131. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.12.006

- Kramer U. Good-enough therapy: a review of the empirical basis of good psychiatric management. Am J Psychother. 2025;78(1): 11-15. doi:10.1176/appi .psychotherapy.20230041

- Visdómine-Lozano JC. Contextualist perspectives in the treatment of antisocial behaviors and offending: a comparative review of FAP, ACT, DBT, and MDT. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23(1):241-254. doi:10.1177/1524838020939509

- Drago A, Marogna C, Jørgen Søgaard H. A review of characteristics and treatments of the avoidant personality disorder. Could the DBT be an option? Int J Psychol Psychoanal. 2016;2(1):013.

- Finch EF, Choi-Kain LW, Iliakis EA, Eisen JL, Pinto A. Good psychiatric management for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2021;8:160-171. doi:10.1007/s40473-021-00239-4

- Miller TW, Kraus RF. Modified dialectical behavior therapy and problem solving for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Journal Contemp Psychother. 2007;37:79-85. doi:10.1007/s10879-006-9039-4

- Bozzatello P, Rocca P, De Rosa ML, Bellino S. Current and emerging medications for borderline personality disorder: is pharmacotherapy alone enough? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(1):47-61.doi:10.1080/14656566 .2019.1686482

- Sand P, Derviososki E, Kollia S, Strand J, Di Leone F. Psychiatrists’ perspectives on prescription decisions for patients with personality disorders. J Pers Disord. 2024;38(3):225-240. doi:10.1521/pedi.2024.38.3.225

- Kane JM, Leucht S, Carpenter D, Docherty JP; Expert Consensus Panel for Optimizing Pharmacologic Treatment of Psychotic Disorders. The expert consensus guideline series. Optimizing pharmacologic treatment of psychotic disorders. Introduction: Methods, commentary, and summary. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 Suppl 12:5-19.

- Nierenberg AA, Agustini B, Köhler-Forsberg O, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder: a review. JAMA. 2023;330(14):1370-1380. doi:10.1001 /jama.2023.18588

- Köck P, Walter M. Personality disorder and substance use disorder–an update. Ment Health Prev. 2018;12:82- 89. doi:10.1016/J.MHP.2018.10.003

- Garb HN. Race bias and gender bias in the diagnosis of psychological disorders. Clin Psych Rev. 2021;90:102087. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102087

- Debast I, van Alphen SPJ, Rossi G, et al. Personality traits and personality disorders in late middle and old age: do they remain stable? A literature review. Clin Gerontol. 2014;37(3):253-271.doi:10.1080/07317115 .2014.885917

- Penders KAP, Peeters IGP, Metsemakers JFM, van Alphen SPJ. Personality disorders in older adults: a review of epidemiology, assessment, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(3):1-14. doi:10.1007/s11920-020- 1133-x

- Videler AC, Hutsebaut J, Schulkens JEM, Sobczak S, van Alphen SPJ. A life span perspective on borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(7) :1-8. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1040-1

- Wakefield JC. DSM-5 and the general definition of personality disorder. Clin Soc Work J. 2013;41(2):168-183. doi:10.1007/s10615-012-0402-5

- US Census Bureau. 2022 American Community Survey 1-year. Accessed February 28, 2025. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2022.S2101?q=Veterans&y=2022comparison

Personality disorders (PDs) are enduring patterns of internal experience and behavior that differ from cultural norms and expectations, are inflexible and pervasive, have their onset in adolescence or early adulthood, and lead to distress or impairment. Ten PDs are included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition): paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive.1 These disorders impose a high burden on patients, families, health care systems, and broader economic systems.2,3 Up to 1 in 7 persons in the community and 50% of those receiving outpatient mental health treatment experience a PD.4,5 These conditions are associated with an increased risk of adverse events, including suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, homelessness, substance use, underemployment, relational issues, and high utilization of psychiatric services.6-9 PDs are routinely underassessed, underdocumented, and undertreated in clinical settings, and consistently receive less research funding than other, less prevalent forms of psychopathology. 10-12 As a result, there is limited understanding of clinical needs of individuals experiencing PDs.

MILITARY VETERANS WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Underacknowledgment of PDs and their associated difficulties may be especially pronounced in veteran populations. Due to longstanding etiological theories that implicate childhood trauma and adolescent onset in pathology development, PDs are traditionally considered pre-existing conditions or developmental abnormalities by the US Department of Defense and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a result, PDs are therefore deemed incompatible with military service and ineligible for service-connected disability benefits.13-15 Such determinations allowed PD pathology to be used as grounds for discharge for 26,000 service members from 2001 to 2007, or 2.6% of total enlisted discharges during that period.13,15,16

Despite this structural discrimination, recent research suggests veterans may be more likely to experience PD pathology than the general population.17 For example, a 2021 epidemiological survey in a community-based veteran sample found elevated rates of borderline, antisocial, and schizotypal PDs (6%-13%).6 In contrast, only 0.8% to 5.0% of veteran electronic health records (EHRs) have a documented PD diagnosis.8,18,19 Such elevations in PD pathology within veteran samples imply either a disproportionately high prevalence among enlistees (and therefore missed during recruitment procedures) or onset following military service, possibly due to exposure to traumatic events and/ or occupational stress.17 Due to the relative infancy of research in this area and a lack of longitudinal studies, etiology and course of illness for personality pathology in veterans remains largely unclear.

Structural underacknowledgment of PDs among military personnel has contributed to their underrepresentation in research on veteran populations. PD-focused research with veterans is rare, despite a rapid increase in broader empirical attention paid to these conditions in nonveteran samples.20 A recent meta-analysis of veterans with PDs identified 27 studies that included basic prevalence statistics. PDs were rarely a primary focus for these studies, and most were limited to veterans seen in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) settings.17 The literature also paints a bleak picture, suggesting veterans who experience PDs are at higher risk for suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, and homelessness. They also tend to experience more severe comorbid psychopathological symptoms and more often use high-intensity mental health services (eg, care within emergency departments or psychiatric inpatient settings) than veterans without PD pathology.6,8,18,19,21 However, PD pathology does not appear to impede the effectiveness of treatment for veterans.22-24 The implications of PD pathology on broader psychosocial functioning and health care needs certify a need for additional research that examines patterns of personality pathology, particularly in veterans outside the VHA.

METHODS

This study aims to enhance understanding of veterans affected by PDs and offer insight and guidance for treatment of these conditions in federal and nonfederal treatment settings. Previous research has been largely limited to VHA care-receiving samples; the longstanding stigma against PDs by the US military and VA may contribute to biased diagnosis and documentation of PDs in these settings. A large sample of veterans receiving community-based mental health care was therefore used to explore aims of the current study. This study specifically examined demographic patterns, diagnostic comorbidity, psychosocial outcomes, and treatment care settings among veterans with and without a PD diagnosis. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that veterans with a PD diagnosis would have more severe mental health comorbidities, poorer psychosocial outcomes, and receive care in higher intensity settings relative to veterans without a diagnosis.

Data for the sample were drawn from the Mental Health Client-Level Data, a publicly available national dataset of nearly 7 million patients who received mental health treatment services provided or funded through state mental health agencies in 2022.25 The analytic sample included about 2.5 million patients for whom veteran status and data around the presence or absence of a PD diagnosis were available. Of these patients, 104,198 were identified as veterans. Veteran patients were identified as predominantly male (63%), White (71%), non-Hispanic (90%), and never married (54%).

Measures

The parent dataset included demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome information reported by treatment facilities to individual state administrative systems for each patient who received services. To protect patient privacy, only nonprotected health information is included, and efforts were made throughout compilation of the parent dataset to ensure patient privacy (eg, limiting detail of information disseminated for public access). Because the parent dataset does not include protected health information, studies using these data are considered exempt from institutional review board oversight.

Demographic information. This study reviewed veteran status, sex, race, ethnicity, age, education, and marital status. Veteran status was defined by whether the patient was aged ≥ 18 years and had previously served (but was not currently serving) in the military. Patients with a history of service in the National Guard or Military Reserves were only classified as veterans if they had been called or ordered to active duty while serving. Sex was operationalized dichotomously as male or female; no patients were identified as intersex, transgender, or other gender identities.

Clinical information. Up to 3 mental health diagnoses were reported for each patient and included the following disorders: personality, trauma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity, stressor, anxiety, conduct, delirium/dementia, bipolar, depressive, oppositional defiant, pervasive developmental, schizophrenia or other psychotic, and alcohol or substance use. Mental health diagnosis categories were generated for the parent dataset by grouping diagnostic codes corresponding to each category. To protect patient privacy, more detailed diagnostic information was not available as part of the parent dataset. Although the American Psychiatric Association recognizes 10 distinct PDs, the exact nature of PD diagnoses was not included within the parent dataset. PD diagnoses were coded to reflect the presence or absence of any such diagnosis.

A substance use problem designation was also provided for patients according to various identification methods, including substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis, substance use screening results, enrollment in a substance use program, substance use survey, service claims information, and other related sources of information. A severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance designation was provided for patients meeting state definitions of these designations. Context(s) of service provision were coded as inpatient state psychiatric hospital, community-based program, residential treatment center, judicial institution, or other psychiatric inpatient setting.

Psychosocial outcome information. Patient employment and residential status were also included in analyses. Each reflected status at the time of discharge from services or end of reporting period; employment status was only provided for patients receiving treatment in community-based programs.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and X2 analyses were used to compare demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome variables between patients with and without PD diagnoses. These analyses were calculated for both the 104,198 veterans and the 2,222,306 nonveterans aged ≥ 18 years in the dataset. Given the sample size, a conservative α of .01 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

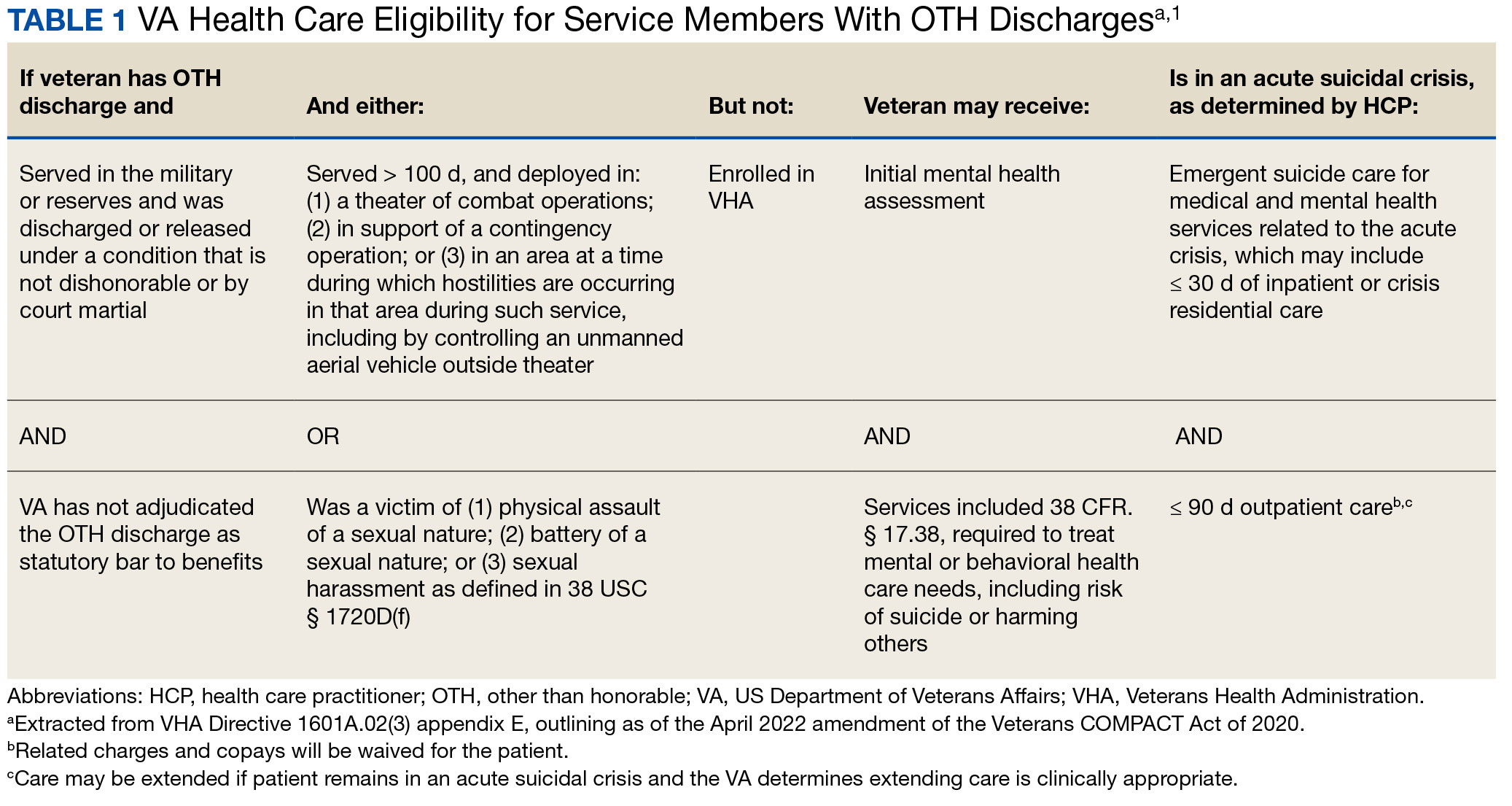

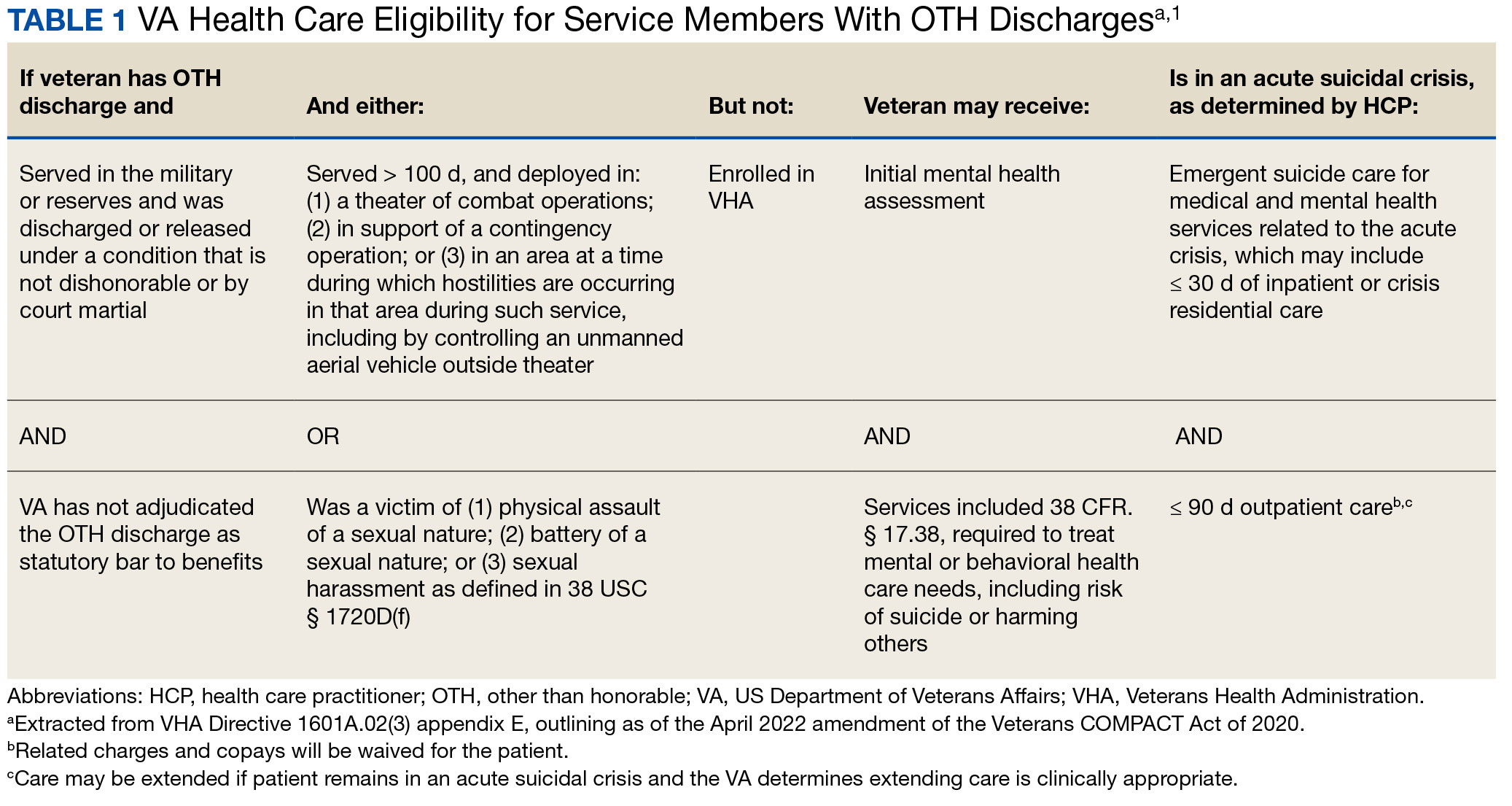

In this sample of persons receiving state-funded mental health care, veterans were significantly less likely than nonveterans to have a documented PD diagnosis (2.1% vs 3.6%, X2 [1] = 647.49; P < .01). PD diagnoses were more common among White (risk ratio [RR], 1.11), non-Hispanic (RR, 1.03) veterans who were in middle to late adulthood (RR, 1.16-1.40), more educated (RR, 1.35), and divorced or widowed (RR, 1.43), and less common among Black/African American (RR, 0.78) or Puerto Rican (RR, 0.32) veterans who were in early adulthood (RR, 0.31-0.79), less educated (RR, 0.64-0.89), and currently married (RR, 0.89) or never married (RR, 0.86). Veteran men and women were equally likely to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 1.03) (Table 1). Among nonveterans, men were less likely than women to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.79), and PD diagnoses were most common among persons in middle adulthood (RR, 1.06-1.15) (eAppendix 1).

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were more likely than those without a diagnosis to have more diagnoses (RR, 2.96-8.49) and to have comorbid trauma or related stressor (RR, 1.33), or bipolar (RR, 1.56) or psychotic (RR, 1.15) disorder diagnoses, but less likely to have comorbid depressive disorder (RR, 0.82). Although veterans with and without a PD diagnosis were similarly likely to have a comorbid SUD (RR, 1.13), those with a PD diagnosis were significantly less likely to be assigned a substance use problem designation (RR, 0.78). PD diagnosis was also more common among veterans who received services in state psychiatric hospitals (RR, 3.05), community-based clinics (RR, 1.06), and judicial institutions (RR, 6.33) and less common among those who received services in other psychiatric inpatient settings (RR, 0.30). No differences were observed for residential treatment settings (RR, 0.79). Among nonveterans, a PD diagnosis was associated with slightly greater odds of a substance use designation (RR, 1.03) (eAppendix 2).

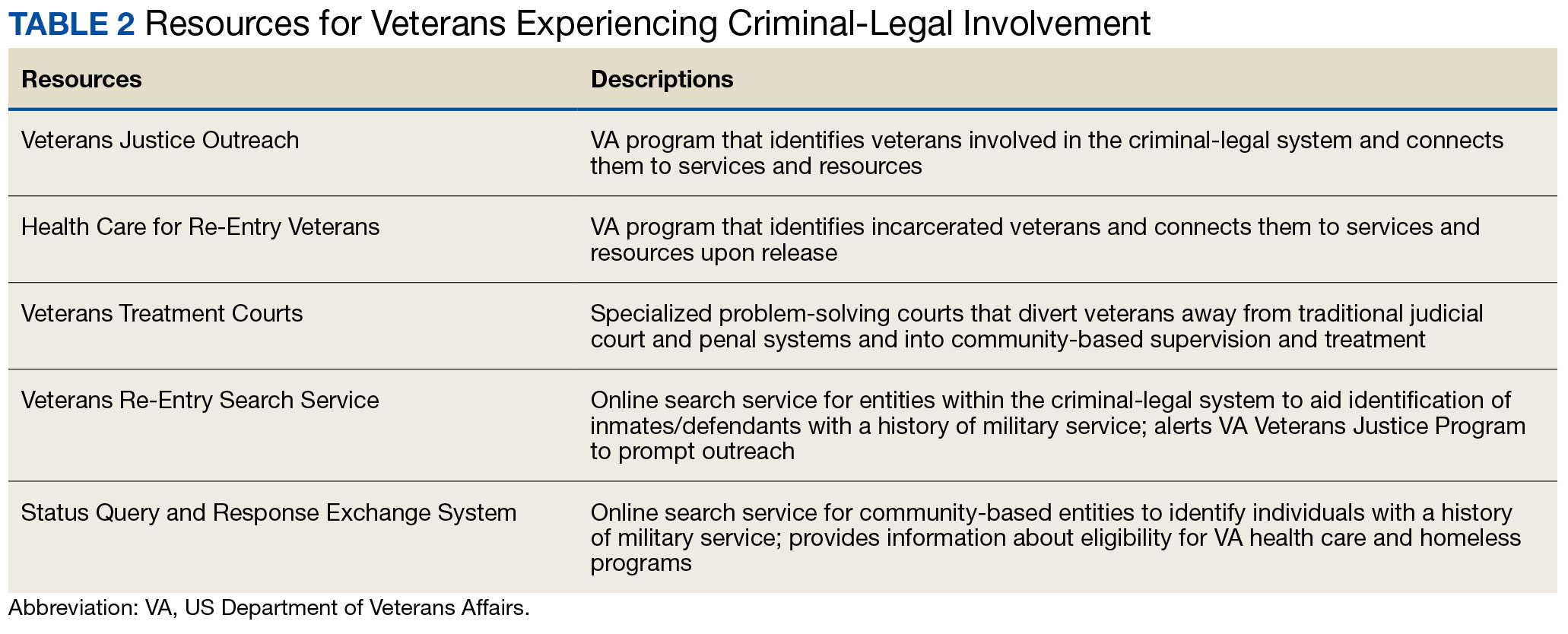

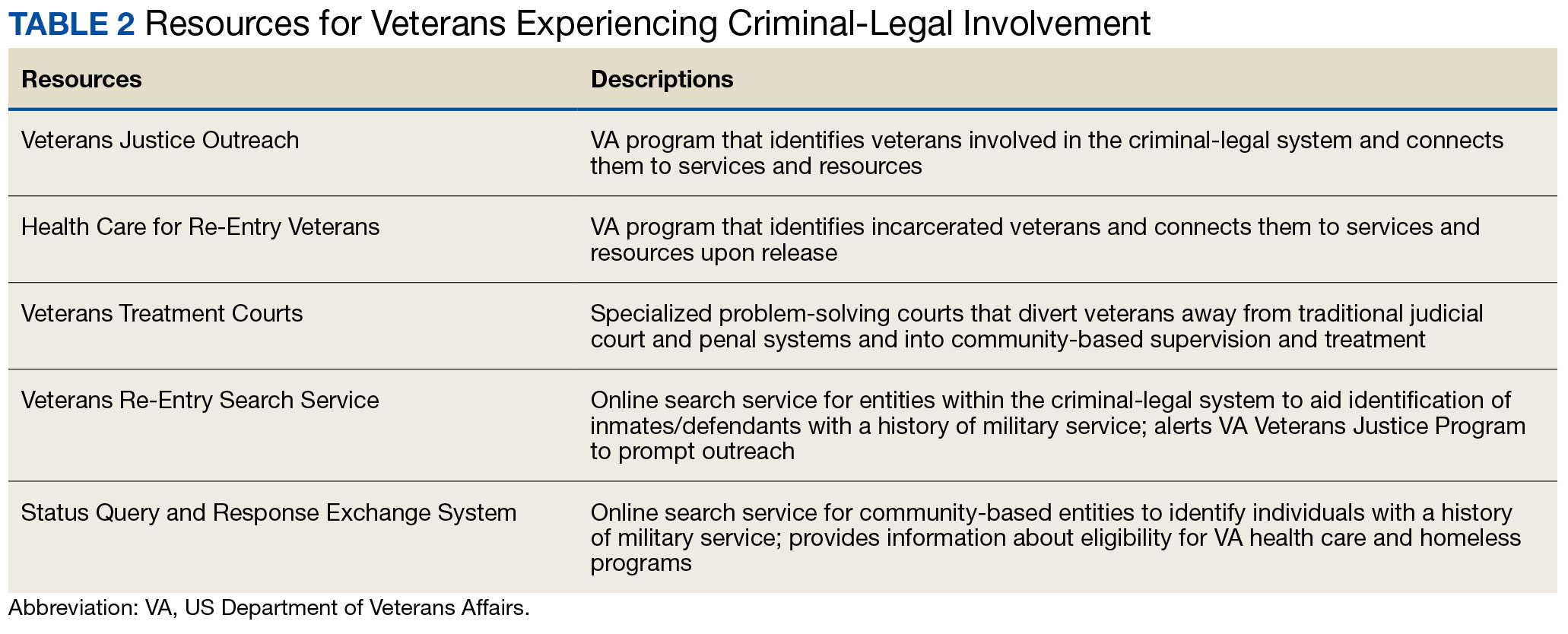

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also less likely to have full-time employment (RR, 0.73) and more likely to have undifferentiated employment (RR, 2.00) or to be removed from the labor force (RR, 1.35). Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also more likely to reside in nontraditional living conditions (RR, 1.42) and less likely to be residing in a private residence (RR, 0.98), compared with those without PD diagnosis. The rates of homelessness were similar for veterans with and without a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.90) (Table 2). These patterns were similar among nonveterans.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the rate and correlates of PD diagnosis among a large, community-based sample of veterans receiving state-funded mental health care. About 2% of veterans in this sample had a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, with higher education, divorced or widowed, also diagnosed with trauma-related, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in state psychiatric hospital, community-based clinic, or judicial system settings.

The observed rate of PD diagnosis in this study aligns with what is typically observed in VHA EHRs.8,18,19 However, the rate is notably lower than prevalence estimates for psychiatric outpatient settings (about 50%) and in meta-analyses of prevalence among veterans (0.8%-23% for each of the 10 PDs).4,17,26 Longstanding stigma against PDs may contribute to underdiagnosis. For example, many clinicians are concerned that documentation or disclosure of a PD will interfere with the patient’s ability to access treatment due to stigma and discrimination.27,28 These fears are not unfounded; even among clinicians, PDs are commonly considered untreatable, and many individuals with PDs are denied access to evidence-based treatments due to the diagnosis.29 In a 2016 survey of community psychiatrists, nearly 1 in 4 reported that they avoid taking patients with a borderline PD diagnosis in their caseloads.28 To date, no studies have been conducted to explore clinicians’ willingness to accept patients with other PDs or, specifically, among veterans.

Despite such widespread stigma, research suggests clinicians' negative attitudes toward PDs can be decreased through antistigma campaigns.30 However, it remains unclear if such efforts also contribute to an increase in clinicians’ willingness to document PD diagnoses. Without accurate identification and documentation, the field’s understanding of PDs will remain limited.

In the current study, veterans with PD diagnoses tended to present with more complex and severe psychiatric comorbidities compared to veterans without such diagnoses. Observed comorbidity of PDs (particularly borderline PD) with trauma-related and bipolar disorders is well established.8 Conversely, co-occurring personality and psychotic disorders—which comprise 16% of veterans with a PD diagnosis in the sample in this study—are not consistently examined in the literature. A 2022 examination of veterans receiving VHA care suggested 12% and 13% of those with a PD diagnosis documented in their EHR also had documented schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, respectively. PD diagnoses were associated with 6.88- and 9.80-fold increases in risk for comorbid schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder diagnoses, respectively.8 Similarly, a recent longitudinal study of nearly 2 million Swedish individuals suggested borderline PD is specifically associated with a > 24-times greater risk of having a comorbid psychotic disorder.31 It is therefore possible that the comorbidity between personality and psychotic disorders is quite common despite its relative lack of attention in empirical research.

Veterans with PD diagnoses in this study were also more likely to experience substandard housing, employment challenges, and receive treatment through judicial institutions than those without a PD diagnosis. Such findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the substantial psychosocial challenges associated with PD diagnosis, even after controlling for comorbid conditions.7,9 Veterans with PDs may benefit from specialized case management and support to facilitate stable housing and employment and to mitigate the risk of judicial involvement. Some research suggests veterans with PDs may be less likely to gain competitive employment after participating in VA therapeutic and supportive employment services programs, suggesting standard programming may be less suitable for this population.32 Similarly, other research suggests individuals with PDs may benefit more from specialized, intensive services than standard clinical case management.33 Future research may therefore benefit from clarifying the degree to which adaptations to standard programming could yield beneficial effects for persons with PD diagnoses.

Implications

Cumulatively, the results of this study attest to the necessity for transdiagnostic treatment planning that includes close collaboration between psychotherapeutic, pharmacological, and case management services. Some psychotherapy models for PDs, such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which includes a combination of group skills training, individual therapy, as-needed phone coaching, and therapist consultation, may be successfully adapted to include this collaboration.34-36 However, implementation of such comprehensive programming often requires extensive clinician training and coordination of resources, which poses implementation challenges.37-39 In 2021, the VHA began large-scale implementation of PD-specific psychotherapy for veterans with recent suicidal self-directed violence and borderline PD, including DBT, though to date results remain unclear.40 Generalist approaches, such as good psychiatric management (GPM), which emphasizes emotional validation, practical problem solving, realistic goal setting, and relationship functioning within the context of standard care appointments, may be more easily implemented in community care settings due to lesser training and resource requirements and can also be adapted to include needed elements of care coordination.41,42 Both DBT and GPM were initially developed for the treatment of borderline PD. Although DBT has also demonstrated some effectiveness in the treatment of antisocial PD, potential applications of DBT and GPM to other PDs remain largely underdeveloped.43-46

There are no widely accepted medications for the treatment of PDs. Pharmacotherapy for these conditions typically consists of individualized approaches informed by personal experience that attempt to balance targeting of specific symptoms while minimizing polypharmacy and potential risks (eg, overdose or addiction).47,48 Despite this, pharmacotherapy is often considered a necessary component in the treatment of bipolar and psychotic disorders, both common comorbidities of PDs found in veterans in this study.49,50 Careful consideration of complex comorbidities and pharmacotherapy needs is warranted in the treatment of veterans with PDs. Future research may benefit from clarifying clinical guidelines around pharmacotherapy, particularly for observed comorbidities of PDs to trauma, bipolar, and psychotic disorders.

It is important to note the discrepancies in the results of this study surrounding patient substance use. The results suggest a negligible or inverse association between the likelihood of a PD diagnosis and difficulties with substance use among the veterans in this study. However, the unexpectedly low rate of SUD diagnoses (< 6%) suggests that they were likely underdocumented. Research suggests a strong association between personality and SUDs in both veteran and civilian samples.6,51 Results suggesting a lower prevalence of substance use difficulties among treatment-seeking veterans with PDs should be interpreted with great caution.

Demographically, PD diagnoses were more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, and aged ≥ 45 years, and less common among veterans who were Black/ African American, mixed/unspecified race, Puerto Rican or other non-Mexican Hispanic ethnicity, or aged < 35 years. No significant sex-based differences were observed. These patterns are consistent with research suggesting individuals who identify as Black may be less likely than individuals who identify as White to report PD symptoms, meet criteria for a PD, and have a PD diagnosed even when it is warranted.52

The findings observed in this study with respect to age, however, are notably inconsistent with the literature. Previous research typically suggests a negative association between age and PD pathology; however, a 2020 review of PDs in older adults by Penders et al suggests a prevalence of 11% to 15% in this population.53,54 Research into PDs most often focuses on adolescent and early adulthood developmental periods, limiting insight into the phenomenology of PDs in middle to late adulthood.55 Further, most research into PDs among geriatric populations has focused on psychometric assessment rather than practical treatment guidance.54 However, in this study, elevated risk for PD diagnoses was salient throughout middle to late adulthood among veterans; similar, albeit less pronounced patterns were also observed for elevated risk of PD diagnosis in middle adulthood among nonveterans. Such findings suggest clarifying the phenomenology and treatment needs of individuals with PDs in middle to late adulthood may have particularly salient implications for the mental health care of veterans affected by these conditions. As the veteran population advances in age, these needs will present unique challenges if health care systems are unprepared to effectively address them.

Limitations

This study is characterized by several strengths, most notably its use of a large dataset recently collected on a national scale. Few studies outside of the VHA system include samples of > 100,000 treatment-seeking veterans collected on a national scale. Nevertheless, results should be understood within the context of several methodological limitations. However, the dataset was limited to the first 3 diagnoses documented in patients’ EHRs, and many patients had no listed diagnoses. Patients with complex comorbidities may have > 3 diagnoses; for these individuals, data provided an incomplete picture of clinical presentation. This is especially relevant for individuals with PDs, who tend to meet criteria for a range of comorbid conditions.8,10 The now dated practice of listing PDs on Axis II also increases the chance of clinicians listing PDs after conditions traditionally listed on Axis I (eg, major depressive disorder) in patient charts.56 This study’s inclusion of only the first 3 listed diagnoses likely underestimated true PD diagnosis prevalence.

The results of this study must be interpreted as reflecting the prevalence and correlates of receiving a PD diagnosis rather than meeting diagnostic criteria for a PD. Relatedly, PD diagnoses were reported as a single construct, limiting insight into prevalence and correlates of individual PD diagnoses (eg, borderline vs paranoid PDs). Meta-analyses estimates suggest PD prevalence among veterans is likely much higher than observed in this study.17 Stigma continues to discourage clinicians from documenting and disclosing PD diagnoses even when warranted.27,28 Continued research should aim to clarify conditions (eg, patient presentation, stigma, or institutional culture) contributing to documentation of PD diagnoses. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, results cannot speak to longitudinal treatment outcomes or prognosis of persons receiving a PD diagnosis.

Despite its large sample size and national representation, the sampling strategy of this study could have contributed to idiosyncrasies in the dataset. Restriction of data to the persons receiving state-funded mental health services introduces a notable bias to the composition of the sample, which is likely comprised of a disproportionately high number of Medicaid recipients, students, and individuals with chronic illnesses and underrepresentation of persons who pay for mental health services using private insurance or private pay arrangements. As such, although socioeconomic information was not provided within this dataset, one can presume a generally lower socioeconomic status among study participants compared to the community at large. This study also included a proportionally small sample of veterans (3.6% compared to about 6.2% in the broader US population), suggesting veterans may have been underrepresented or underidentified in surveyed mental health care settings.57 This study also did not include data around service in active-duty military, national guard, or military reserves; a greater proportion of the sample likely had a history of military service than was represented by veteran status designation. Further, the proportionally high sample of individuals with severe mental illness suggests a likely overrepresentation of such conditions in surveyed settings.

Institutional differences in the practice of assigning diagnoses likely limited statistical power to detect potentially meaningful associations and effects. Structural influences, such as stigma and institutional culture, may have notable effects on documentation practices, particularly for PDs. Future research should aim to replicate observed associations using more controlled diagnostic procedures.

Lastly, even with the use of a more conservative α and a focus on effect sizes to guide interpretation of results, use of multiple bivariate analyses can be presumed to have increased the likelihood of type I error. Given the limited prior research in this area, an exploratory approach to statistical analysis was considered warranted to maximize opportunity for identifying areas in need of additional empirical attention. Continued research using more conservative statistical approaches (eg, multivariate analyses) is needed to determine replicability and generalizability of observed results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of PD diagnoses in a national sample of veterans receiving community-based, state-funded mental health care. About 2% received a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses most common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, also diagnosed with trauma-based, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in a state psychiatric hospital or judicial system setting. The results attest to a necessity for transdiagnostic treatment planning and care coordination for this population, with particular attention to psychosocial stressors.

Personality disorders (PDs) are enduring patterns of internal experience and behavior that differ from cultural norms and expectations, are inflexible and pervasive, have their onset in adolescence or early adulthood, and lead to distress or impairment. Ten PDs are included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition): paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, histrionic, narcissistic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive.1 These disorders impose a high burden on patients, families, health care systems, and broader economic systems.2,3 Up to 1 in 7 persons in the community and 50% of those receiving outpatient mental health treatment experience a PD.4,5 These conditions are associated with an increased risk of adverse events, including suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, homelessness, substance use, underemployment, relational issues, and high utilization of psychiatric services.6-9 PDs are routinely underassessed, underdocumented, and undertreated in clinical settings, and consistently receive less research funding than other, less prevalent forms of psychopathology. 10-12 As a result, there is limited understanding of clinical needs of individuals experiencing PDs.

MILITARY VETERANS WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Underacknowledgment of PDs and their associated difficulties may be especially pronounced in veteran populations. Due to longstanding etiological theories that implicate childhood trauma and adolescent onset in pathology development, PDs are traditionally considered pre-existing conditions or developmental abnormalities by the US Department of Defense and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a result, PDs are therefore deemed incompatible with military service and ineligible for service-connected disability benefits.13-15 Such determinations allowed PD pathology to be used as grounds for discharge for 26,000 service members from 2001 to 2007, or 2.6% of total enlisted discharges during that period.13,15,16

Despite this structural discrimination, recent research suggests veterans may be more likely to experience PD pathology than the general population.17 For example, a 2021 epidemiological survey in a community-based veteran sample found elevated rates of borderline, antisocial, and schizotypal PDs (6%-13%).6 In contrast, only 0.8% to 5.0% of veteran electronic health records (EHRs) have a documented PD diagnosis.8,18,19 Such elevations in PD pathology within veteran samples imply either a disproportionately high prevalence among enlistees (and therefore missed during recruitment procedures) or onset following military service, possibly due to exposure to traumatic events and/ or occupational stress.17 Due to the relative infancy of research in this area and a lack of longitudinal studies, etiology and course of illness for personality pathology in veterans remains largely unclear.

Structural underacknowledgment of PDs among military personnel has contributed to their underrepresentation in research on veteran populations. PD-focused research with veterans is rare, despite a rapid increase in broader empirical attention paid to these conditions in nonveteran samples.20 A recent meta-analysis of veterans with PDs identified 27 studies that included basic prevalence statistics. PDs were rarely a primary focus for these studies, and most were limited to veterans seen in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) settings.17 The literature also paints a bleak picture, suggesting veterans who experience PDs are at higher risk for suicide attempt and death by suicide, criminal-legal involvement, and homelessness. They also tend to experience more severe comorbid psychopathological symptoms and more often use high-intensity mental health services (eg, care within emergency departments or psychiatric inpatient settings) than veterans without PD pathology.6,8,18,19,21 However, PD pathology does not appear to impede the effectiveness of treatment for veterans.22-24 The implications of PD pathology on broader psychosocial functioning and health care needs certify a need for additional research that examines patterns of personality pathology, particularly in veterans outside the VHA.

METHODS

This study aims to enhance understanding of veterans affected by PDs and offer insight and guidance for treatment of these conditions in federal and nonfederal treatment settings. Previous research has been largely limited to VHA care-receiving samples; the longstanding stigma against PDs by the US military and VA may contribute to biased diagnosis and documentation of PDs in these settings. A large sample of veterans receiving community-based mental health care was therefore used to explore aims of the current study. This study specifically examined demographic patterns, diagnostic comorbidity, psychosocial outcomes, and treatment care settings among veterans with and without a PD diagnosis. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that veterans with a PD diagnosis would have more severe mental health comorbidities, poorer psychosocial outcomes, and receive care in higher intensity settings relative to veterans without a diagnosis.

Data for the sample were drawn from the Mental Health Client-Level Data, a publicly available national dataset of nearly 7 million patients who received mental health treatment services provided or funded through state mental health agencies in 2022.25 The analytic sample included about 2.5 million patients for whom veteran status and data around the presence or absence of a PD diagnosis were available. Of these patients, 104,198 were identified as veterans. Veteran patients were identified as predominantly male (63%), White (71%), non-Hispanic (90%), and never married (54%).

Measures

The parent dataset included demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome information reported by treatment facilities to individual state administrative systems for each patient who received services. To protect patient privacy, only nonprotected health information is included, and efforts were made throughout compilation of the parent dataset to ensure patient privacy (eg, limiting detail of information disseminated for public access). Because the parent dataset does not include protected health information, studies using these data are considered exempt from institutional review board oversight.

Demographic information. This study reviewed veteran status, sex, race, ethnicity, age, education, and marital status. Veteran status was defined by whether the patient was aged ≥ 18 years and had previously served (but was not currently serving) in the military. Patients with a history of service in the National Guard or Military Reserves were only classified as veterans if they had been called or ordered to active duty while serving. Sex was operationalized dichotomously as male or female; no patients were identified as intersex, transgender, or other gender identities.

Clinical information. Up to 3 mental health diagnoses were reported for each patient and included the following disorders: personality, trauma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity, stressor, anxiety, conduct, delirium/dementia, bipolar, depressive, oppositional defiant, pervasive developmental, schizophrenia or other psychotic, and alcohol or substance use. Mental health diagnosis categories were generated for the parent dataset by grouping diagnostic codes corresponding to each category. To protect patient privacy, more detailed diagnostic information was not available as part of the parent dataset. Although the American Psychiatric Association recognizes 10 distinct PDs, the exact nature of PD diagnoses was not included within the parent dataset. PD diagnoses were coded to reflect the presence or absence of any such diagnosis.

A substance use problem designation was also provided for patients according to various identification methods, including substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis, substance use screening results, enrollment in a substance use program, substance use survey, service claims information, and other related sources of information. A severe mental illness or serious emotional disturbance designation was provided for patients meeting state definitions of these designations. Context(s) of service provision were coded as inpatient state psychiatric hospital, community-based program, residential treatment center, judicial institution, or other psychiatric inpatient setting.

Psychosocial outcome information. Patient employment and residential status were also included in analyses. Each reflected status at the time of discharge from services or end of reporting period; employment status was only provided for patients receiving treatment in community-based programs.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and X2 analyses were used to compare demographic, clinical, and psychosocial outcome variables between patients with and without PD diagnoses. These analyses were calculated for both the 104,198 veterans and the 2,222,306 nonveterans aged ≥ 18 years in the dataset. Given the sample size, a conservative α of .01 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

In this sample of persons receiving state-funded mental health care, veterans were significantly less likely than nonveterans to have a documented PD diagnosis (2.1% vs 3.6%, X2 [1] = 647.49; P < .01). PD diagnoses were more common among White (risk ratio [RR], 1.11), non-Hispanic (RR, 1.03) veterans who were in middle to late adulthood (RR, 1.16-1.40), more educated (RR, 1.35), and divorced or widowed (RR, 1.43), and less common among Black/African American (RR, 0.78) or Puerto Rican (RR, 0.32) veterans who were in early adulthood (RR, 0.31-0.79), less educated (RR, 0.64-0.89), and currently married (RR, 0.89) or never married (RR, 0.86). Veteran men and women were equally likely to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 1.03) (Table 1). Among nonveterans, men were less likely than women to have a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.79), and PD diagnoses were most common among persons in middle adulthood (RR, 1.06-1.15) (eAppendix 1).

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were more likely than those without a diagnosis to have more diagnoses (RR, 2.96-8.49) and to have comorbid trauma or related stressor (RR, 1.33), or bipolar (RR, 1.56) or psychotic (RR, 1.15) disorder diagnoses, but less likely to have comorbid depressive disorder (RR, 0.82). Although veterans with and without a PD diagnosis were similarly likely to have a comorbid SUD (RR, 1.13), those with a PD diagnosis were significantly less likely to be assigned a substance use problem designation (RR, 0.78). PD diagnosis was also more common among veterans who received services in state psychiatric hospitals (RR, 3.05), community-based clinics (RR, 1.06), and judicial institutions (RR, 6.33) and less common among those who received services in other psychiatric inpatient settings (RR, 0.30). No differences were observed for residential treatment settings (RR, 0.79). Among nonveterans, a PD diagnosis was associated with slightly greater odds of a substance use designation (RR, 1.03) (eAppendix 2).

Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also less likely to have full-time employment (RR, 0.73) and more likely to have undifferentiated employment (RR, 2.00) or to be removed from the labor force (RR, 1.35). Veterans with a PD diagnosis were also more likely to reside in nontraditional living conditions (RR, 1.42) and less likely to be residing in a private residence (RR, 0.98), compared with those without PD diagnosis. The rates of homelessness were similar for veterans with and without a PD diagnosis (RR, 0.90) (Table 2). These patterns were similar among nonveterans.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the rate and correlates of PD diagnosis among a large, community-based sample of veterans receiving state-funded mental health care. About 2% of veterans in this sample had a PD diagnosis, with diagnoses more common among veterans who were White, non-Hispanic, aged ≥ 45 years, with higher education, divorced or widowed, also diagnosed with trauma-related, bipolar, and/or psychotic disorders, underemployed, nontraditionally housed, and receiving treatment in state psychiatric hospital, community-based clinic, or judicial system settings.

The observed rate of PD diagnosis in this study aligns with what is typically observed in VHA EHRs.8,18,19 However, the rate is notably lower than prevalence estimates for psychiatric outpatient settings (about 50%) and in meta-analyses of prevalence among veterans (0.8%-23% for each of the 10 PDs).4,17,26 Longstanding stigma against PDs may contribute to underdiagnosis. For example, many clinicians are concerned that documentation or disclosure of a PD will interfere with the patient’s ability to access treatment due to stigma and discrimination.27,28 These fears are not unfounded; even among clinicians, PDs are commonly considered untreatable, and many individuals with PDs are denied access to evidence-based treatments due to the diagnosis.29 In a 2016 survey of community psychiatrists, nearly 1 in 4 reported that they avoid taking patients with a borderline PD diagnosis in their caseloads.28 To date, no studies have been conducted to explore clinicians’ willingness to accept patients with other PDs or, specifically, among veterans.

Despite such widespread stigma, research suggests clinicians' negative attitudes toward PDs can be decreased through antistigma campaigns.30 However, it remains unclear if such efforts also contribute to an increase in clinicians’ willingness to document PD diagnoses. Without accurate identification and documentation, the field’s understanding of PDs will remain limited.