User login

Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: Prevention and management

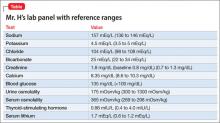

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

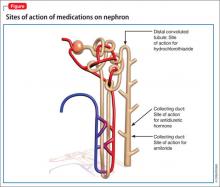

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

Mr. H, age 33, was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder 9 years ago. For the past year, his mood symptoms have been well controlled with lithium 300 mg, 3 times a day, and olanzapine, 20 mg/d. He presents to the outpatient clinic for a routine visit complaining of insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and increased thirst. He also notes that his tremor has become more prominent over the last few weeks. Concerned about his symptoms, Mr. H’s clinician orders a comprehensive laboratory panel (Table).

Upon further questioning, Mr. H’s physician determines that his insomnia is caused by nocturnal urination, which is consistent with fluid and electrolyte imbalances seen in Mr. H’s laboratory panel. Mr. H is diagnosed with lithium-induced diabetes insipidus.

Although lithium’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is known that lithium can negatively affect the kidneys.1,2 Typically, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates water permeability in the collecting duct of the nephron, allowing water to be reabsorbed through simple diffusion in the kidney’s collecting duct (Figure).3 Chronic lithium use reduces or desensitizes the kidney’s ability to respond to ADH. Resistance to ADH occurs when lithium accumulates in the cells of the collecting duct and inhibits ADH’s ability to increase water permeability. This inhibition can cause some of Mr. H’s symptoms, such as polydipsia and polyuria, and is estimated to occur in approximately 40% of patients receiving long-term lithium therapy.4,5

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) begins with a history of the patient’s symptoms and ordering lab tests.5 The next step involves a water restriction test, also known as a thirst test, to measure the patient’s ability to concentrate his or her urine. Baseline serum osmolality and electrolytes are compared with new values obtained after completing the water restriction test. Healthy people will have a 2-to-4-fold increase in urine osmolality compared with patients who have NDI. The last step includes administering desmopressin and differentiates between central diabetes insipidus and NDI.6

After desmopressin use, patients who have central diabetes insipidus will have a >50% increase in urine osmolality, whereas patients who have NDI will have <10% increase in urine osmolality. This distinction is important because patients with central diabetes insipidus might have more severe disease and might not benefit from measures commonly used for lithium-induced NDI.7

Prevention and management

Lithium-induced NDI is thought to be dose-dependent and may be prevented by using the lowest effective dose of lithium for an individual patient. It is important that patients taking lithium receive basic electrolyte, hematologic, liver function, renal function, and thyroid function tests at baseline and every 6 to 12 months after the lithium regimen is stable. Additionally, lithium levels should be monitored frequently. The frequency of these tests may range from twice weekly to every 3 to 4 months or longer, depending on the patient’s condition. This monitoring allows the prescriber to quickly identify emerging adverse effects.

Patients with impaired renal function and those with a urine output >3 liters a day are more susceptible to NDI and require monitoring every 3 months. Also, instruct patients to monitor their urine output and educate them about the dangers of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and the signs and symptoms of NDI, such as excessive thirst and urination.1,2

When a patient experiences lithium-induced NDI, re-evaluate treatment and dosage, including simplifying the dosing regimen or switching to once-daily dosing, usually at bedtime. Once-daily dosing results in a lower overall lithium trough, which might allow the kidneys more “drug-free” time.4,5 Additionally, 12-hour lithium levels are approximately 20% higher with once-daily monitoring; continued monitoring is needed during this switch. Patients who have a moderate or severe form of lithium-induced NDI may need to discontinue lithium altogether. There are several options for treating lithium-induced NDI in patients who need to take lithium. Closely monitor kidney function and lithium routinely with these strategies.

Amiloride. This potassium-sparing diuretic minimizes accumulation of lithium by inhibiting collecting duct sodium channels. Studies have shown that amiloride can decrease mean urine volume, increase urine osmolality, and improve the kidneys’ ability to respond to exogenous arginine vasopressin.8

Thiazide diuretics produce mild sodium depletion, which decreases the distal tubule delivery of sodium, therefore increasing water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Hydrochlorothiazide has been shown to reduce urine output by >50% in patients with NDI on a sodium-restricted diet. Hydrochlorothiazide use requires careful monitoring of potassium and lithium levels. Use of a thiazide diuretic also might warrant decreasing the lithium dose by as much as 50% to prevent toxicity.9,10

Low-sodium diet plus hydrochlorothiazide. This route provides another option to decrease urine output during lithium-induced NDI. A reduction in urine output has been shown to be directly proportional to a decrease in salt intake and excretion. Restricting sodium to <2.3 g/d is an appropriate goal for many patients to prevent reoccurring symptoms, which is more than the 3 g/d average that most Americans consume. Potassium and lithium levels must be monitored closely.9

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs’ ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis prevents prostaglandins from antagonizing actions of ADH in the kidney. The result is increased urine concentration via the actions of ADH. Indomethacin has a greater effect than ibuprofen in increasing ADH’s actions on the kidney. Use of concomitant NSAIDs with lithium requires close monitoring of renal function tests.11

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

1. Ecelbarger CA. Lithium treatment and remodeling of the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F37-38.

2. Christensen BM, Kim YH, Kwon TH, et al. Lithium treatment induces a marked proliferation of primarily principal cells in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(1):F39-48.

3. Francis SG, Gardner DG. Basic and clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003:154-158.

4. Stone KA. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1999;12(1):43-47.

5. Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(5):270-276.

6. Wesche D, Deen PM, Knoers NV. Congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: the current state of affairs. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(12):2183-2204.

7. Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:754-759,782-783.

8. Batlle DC, von Riotte AB, Gaviria M, et al. Amelioration of polyuria by amiloride in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):408-414.

9. Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41(11):1988-1997.

10. Kim GH, Lee JW, Oh YK, et al. Antidiuretic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with upregulation of aquaporin-2, Na-Cl co-transporter, and epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(11):2836-2843.

11. Libber S, Harrison H, Spector D. Treatment of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):305-311.

A teen who is wasting away

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

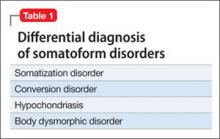

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

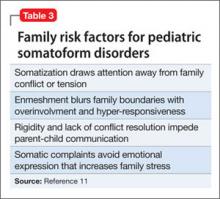

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

HIV: How to provide compassionate care

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

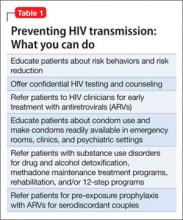

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.