User login

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

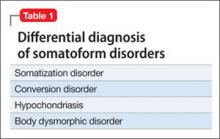

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

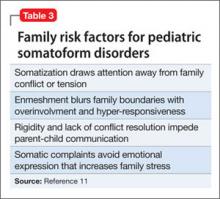

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.

Children who live with a mother with chronic illness are at risk of developing psychosomatic disorders.9 Cassandra’s mother had fibromyalgia and chronic pain with symptoms of headache, weakness, and muscle pain and frequent medical office visits and tests without definitive results or symptom relief. Although Cassandra did not live with her mother, Cassandra’s somatization symptoms may be a result of modeling or observational learning within her family.9 Cassandra may have unconsciously adopted her mother’s symptoms and behaviors as a way to cope with stress and gain attention to her needs.

Cassandra’s negative affect, sensitivity to change, and lack of resiliency were further risk factors for developing a somatoform illness.10 She resisted and would not follow through with physical therapy. Krisnakumar10 also reported that an inability to persist in completing tasks is a risk factor for somatoform disorder. Family dynamics of problematic parental interactions also played a role in her somatoform disorder (Table 3).11

OUTCOME: Foster care, improvement

Cassandra receives weekly CBT and biweekly medication monitoring and demonstrates a moderate improvement in mood with less negativity and irritability. Her anxiety symptoms gradually respond to treatment. However, her emotional gains are not matched with improvement in her physical functioning or participation in physical therapy. Cassandra does not recover her muscular strength or control and shows little improvement in her physical capacity and independence.

After 3 months of treatment, Cassandra does not make sufficient progress or actively participate in treatment. Because her father continues to interfere with the treatment plan and does not receive treatment himself, CPS obtains a court order to prevent her father from directing her medical care and telling her treating physicians which tests to order.

Because these interventions do not improve her treatment response, Cassandra is removed from her parents’ care and placed in a therapeutic foster care home, thereby improving her independence and chances for recovery. After 3 months in foster care, she more actively participates in her physical rehabilitation. Water therapy, with the buoyancy and support in water, helps her regain muscle strength and control of her lower extremities.

Bottom Line

Patients with conversion disorder present with functional impairment and physical symptoms without clear physiological causes. Parents have a strong influence on the presentation and course of conversion disorder in children and adolescents. Parents’ mental and physical illnesses are independent risk factors for childhood somatoform disorders. Evaluation of parents’ psychological and psychiatric state is essential to determine intervention.

Related Resource

- Seltzer WJ. Conversion disorder in childhood and adolescence: a familial/cultural approach. Family Systems Medicine. 1985;3(3):261-280.

Drug Brand Names

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosure

Dr. Leipsic reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

1. Wyllie E, Glazer JP, Benbadis S, et al. Psychiatric features of children and adolescents with pseudoseizures. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):244-248.

2. Salmon P, Al-Marzooqi SM, Baker G, et al. Childhood family dysfunction and associated abuse in patients with nonepileptic seizures: towards a casual model. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):695-700.

3. Manschreck T. Delusional disorder and shared psychotic disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 1243-1264.

4. Meadow R. Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343-345.

5. Campo JV, Fritsch SL. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994; 33(9):1223-1235.

6. Campo JV, Fritz G. A management model for pediatric somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(6):467-476.

7. Silver LB. Conversion disorder with pseudoseizures in adolescence: a stress reaction to unrecognized and untreated learning disabilities. J Am Accad Child Psychiatry. 1982; 21(5):508-512.

8. AlperK,DevinskyO,PerrineK,etal.Nonepilepticseizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993; 43(10):1950-1953.

9. Jamison RN, Walker LS. Illness behavior in children of chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(4): 329-342.

10. Krisnakumar P, Sumesh P, Mathews L. Tempermental traits associated with conversion disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(10):895-899.

11. Minuchin S, Rosman BL, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia nervosa in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.