User login

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

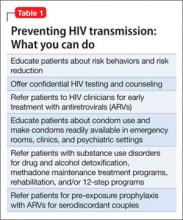

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.