User login

First recommendations for cancer screening in myositis issued

AT ACR 2022

PHILADELPHIA – The first consensus screening guidelines for patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) provide recommendations on risk stratification for individuals, basic and enhanced screening protocols, and screening frequency.

The recommendations, issued by the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS), stratify cancer risk for individual patients into low, intermediate, or high categories based on the IIM disease subtype, autoantibody status, and clinical features, reported Alexander Oldroyd, PhD, MSc, MBChB of the University of Manchester, England.

“There’s a big unmet need for cancer screening. One in four adults with myositis has cancer, either 3 years before or after a diagnosis of myositis. It’s one of the leading causes of death in these patients, and they’re overwhelmingly diagnosed at a late stage, so we need standardized approaches to get early diagnosis,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said in an interview that the guideline is a welcome development for rheumatologists. Dr. Kolasinski moderated the session where Dr. Oldroyd described the guideline, but she was not involved in its formulation.

“I think that we all have wondered for a very long time: What is the optimal cancer screening for myositis patients? We all worry that the onset of their diseases is associated with a coincident cancer, or that they will develop it soon,” she said.

Dr. Oldroyd emphasized that all patients with myositis have elevated risk for cancer compared with the general population and that the guideline categories of low, intermediate, and high are relative only to patients with IIM.

International consensus

The data on which the recommendations are based come from a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dr. Oldroyd and colleagues of 69 studies on cancer risk factors and 9 on IIM-specific cancer screening.

The authors of that paper found that the dermatomyositis subtype, older age, male sex, dysphagia, cutaneous ulceration and antitranscriptional intermediary factor-1 gamma (anti-TIF1-gamma) positivity were associated with significantly increased risk of cancer.

In contrast, polymyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis subtypes, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial lung disease, very high serum creatine kinase or lactate dehydrogenase levels, and positivity for anti-Jo1 or anti-EJ antibodies were associated with significantly reduced risk of cancer.

The consensus recommendations were developed with anonymous contributions from 75 expert participants in 22 countries, with additional input from 3 patient partners.

Do this

The guideline lists 18 recommendations, of which 13 are strong and 5 are conditional.

An example of a strong recommendation is number 3, based on a moderate level of evidences:

“All adult IIM patients, irrespective of cancer risk, should continue to participate in country/region-specific age and sex appropriate cancer screening programs,” the guideline recommends.

Patients with verified inclusion body myositis or juvenile-onset IIM do not, however, require routine screening for myositis-associated cancer, the guideline says (recommendations 1 and 2).

There are also recommendations that all adults with new-onset IIM be tested for myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies to assist in stratifying patients by risk category.

The guideline divides screening recommendations into basic and enhanced. The basic screening should include a comprehensive history and physical exam, complete blood count, liver functions tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rates/plasma viscosity, serum protein electrophoresis, urinalysis, and chest x-ray.

Adults with IIM who are determined to be at low risk for IIM-related cancer should have basic cancer screening at the time of IIM diagnosis. Adults with intermediate risk should undergo both basic and enhanced screening at the time of IIM diagnosis, and those with high risk should undergo enhanced screening at the time of myositis diagnosis, with basic screening annually for 3 years, the recommendations say.

Consider doing this

Conditional recommendations (“clinicians should consider ...”) include the use of PET/CT for adults at high risk for cancer when an underlying cancer has not been detected at the time of IIM diagnosis. They also include a single screening test for anti-TIF1-gamma positive dermatomyositis patients whose disease onset was after age 40 and who have at least one additional risk factor.

Also conditionally recommended are upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy for patients at high risk when an underlying cancer is not found at the time of IIM diagnosis, nasoendoscopy in geographical regions with elevated risk for nasopharyngeal cancers, and screening for all IIM patients with red-flag symptoms or clinical features of cancer, including unexplained weight loss, family history of cancer, smoking, unexplained fever, or night sweats.

Guided steps

“I think clinicians have a lot of questions such as, ‘well, what should I do, when should I do it?’ These are important clinical questions, and we need guidance about this. We need to balance comprehensiveness with cost-effectiveness, and we need expert opinion about what steps we should take now and which should we take later,” Dr. Kolasinski said.

The guideline development process was supported by the University of Manchester, IMACS, National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), National Institutes of Health, National Health Service Northern Care Alliance, The Myositis Association, Myositis UK, University of Pittsburgh, Versus Arthritis, and the Center for Musculoskeletal Research. Dr. Oldroyd and Dr. Kolasinski reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ACR 2022

PHILADELPHIA – The first consensus screening guidelines for patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) provide recommendations on risk stratification for individuals, basic and enhanced screening protocols, and screening frequency.

The recommendations, issued by the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS), stratify cancer risk for individual patients into low, intermediate, or high categories based on the IIM disease subtype, autoantibody status, and clinical features, reported Alexander Oldroyd, PhD, MSc, MBChB of the University of Manchester, England.

“There’s a big unmet need for cancer screening. One in four adults with myositis has cancer, either 3 years before or after a diagnosis of myositis. It’s one of the leading causes of death in these patients, and they’re overwhelmingly diagnosed at a late stage, so we need standardized approaches to get early diagnosis,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said in an interview that the guideline is a welcome development for rheumatologists. Dr. Kolasinski moderated the session where Dr. Oldroyd described the guideline, but she was not involved in its formulation.

“I think that we all have wondered for a very long time: What is the optimal cancer screening for myositis patients? We all worry that the onset of their diseases is associated with a coincident cancer, or that they will develop it soon,” she said.

Dr. Oldroyd emphasized that all patients with myositis have elevated risk for cancer compared with the general population and that the guideline categories of low, intermediate, and high are relative only to patients with IIM.

International consensus

The data on which the recommendations are based come from a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dr. Oldroyd and colleagues of 69 studies on cancer risk factors and 9 on IIM-specific cancer screening.

The authors of that paper found that the dermatomyositis subtype, older age, male sex, dysphagia, cutaneous ulceration and antitranscriptional intermediary factor-1 gamma (anti-TIF1-gamma) positivity were associated with significantly increased risk of cancer.

In contrast, polymyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis subtypes, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial lung disease, very high serum creatine kinase or lactate dehydrogenase levels, and positivity for anti-Jo1 or anti-EJ antibodies were associated with significantly reduced risk of cancer.

The consensus recommendations were developed with anonymous contributions from 75 expert participants in 22 countries, with additional input from 3 patient partners.

Do this

The guideline lists 18 recommendations, of which 13 are strong and 5 are conditional.

An example of a strong recommendation is number 3, based on a moderate level of evidences:

“All adult IIM patients, irrespective of cancer risk, should continue to participate in country/region-specific age and sex appropriate cancer screening programs,” the guideline recommends.

Patients with verified inclusion body myositis or juvenile-onset IIM do not, however, require routine screening for myositis-associated cancer, the guideline says (recommendations 1 and 2).

There are also recommendations that all adults with new-onset IIM be tested for myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies to assist in stratifying patients by risk category.

The guideline divides screening recommendations into basic and enhanced. The basic screening should include a comprehensive history and physical exam, complete blood count, liver functions tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rates/plasma viscosity, serum protein electrophoresis, urinalysis, and chest x-ray.

Adults with IIM who are determined to be at low risk for IIM-related cancer should have basic cancer screening at the time of IIM diagnosis. Adults with intermediate risk should undergo both basic and enhanced screening at the time of IIM diagnosis, and those with high risk should undergo enhanced screening at the time of myositis diagnosis, with basic screening annually for 3 years, the recommendations say.

Consider doing this

Conditional recommendations (“clinicians should consider ...”) include the use of PET/CT for adults at high risk for cancer when an underlying cancer has not been detected at the time of IIM diagnosis. They also include a single screening test for anti-TIF1-gamma positive dermatomyositis patients whose disease onset was after age 40 and who have at least one additional risk factor.

Also conditionally recommended are upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy for patients at high risk when an underlying cancer is not found at the time of IIM diagnosis, nasoendoscopy in geographical regions with elevated risk for nasopharyngeal cancers, and screening for all IIM patients with red-flag symptoms or clinical features of cancer, including unexplained weight loss, family history of cancer, smoking, unexplained fever, or night sweats.

Guided steps

“I think clinicians have a lot of questions such as, ‘well, what should I do, when should I do it?’ These are important clinical questions, and we need guidance about this. We need to balance comprehensiveness with cost-effectiveness, and we need expert opinion about what steps we should take now and which should we take later,” Dr. Kolasinski said.

The guideline development process was supported by the University of Manchester, IMACS, National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), National Institutes of Health, National Health Service Northern Care Alliance, The Myositis Association, Myositis UK, University of Pittsburgh, Versus Arthritis, and the Center for Musculoskeletal Research. Dr. Oldroyd and Dr. Kolasinski reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ACR 2022

PHILADELPHIA – The first consensus screening guidelines for patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) provide recommendations on risk stratification for individuals, basic and enhanced screening protocols, and screening frequency.

The recommendations, issued by the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS), stratify cancer risk for individual patients into low, intermediate, or high categories based on the IIM disease subtype, autoantibody status, and clinical features, reported Alexander Oldroyd, PhD, MSc, MBChB of the University of Manchester, England.

“There’s a big unmet need for cancer screening. One in four adults with myositis has cancer, either 3 years before or after a diagnosis of myositis. It’s one of the leading causes of death in these patients, and they’re overwhelmingly diagnosed at a late stage, so we need standardized approaches to get early diagnosis,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said in an interview that the guideline is a welcome development for rheumatologists. Dr. Kolasinski moderated the session where Dr. Oldroyd described the guideline, but she was not involved in its formulation.

“I think that we all have wondered for a very long time: What is the optimal cancer screening for myositis patients? We all worry that the onset of their diseases is associated with a coincident cancer, or that they will develop it soon,” she said.

Dr. Oldroyd emphasized that all patients with myositis have elevated risk for cancer compared with the general population and that the guideline categories of low, intermediate, and high are relative only to patients with IIM.

International consensus

The data on which the recommendations are based come from a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dr. Oldroyd and colleagues of 69 studies on cancer risk factors and 9 on IIM-specific cancer screening.

The authors of that paper found that the dermatomyositis subtype, older age, male sex, dysphagia, cutaneous ulceration and antitranscriptional intermediary factor-1 gamma (anti-TIF1-gamma) positivity were associated with significantly increased risk of cancer.

In contrast, polymyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis subtypes, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial lung disease, very high serum creatine kinase or lactate dehydrogenase levels, and positivity for anti-Jo1 or anti-EJ antibodies were associated with significantly reduced risk of cancer.

The consensus recommendations were developed with anonymous contributions from 75 expert participants in 22 countries, with additional input from 3 patient partners.

Do this

The guideline lists 18 recommendations, of which 13 are strong and 5 are conditional.

An example of a strong recommendation is number 3, based on a moderate level of evidences:

“All adult IIM patients, irrespective of cancer risk, should continue to participate in country/region-specific age and sex appropriate cancer screening programs,” the guideline recommends.

Patients with verified inclusion body myositis or juvenile-onset IIM do not, however, require routine screening for myositis-associated cancer, the guideline says (recommendations 1 and 2).

There are also recommendations that all adults with new-onset IIM be tested for myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibodies to assist in stratifying patients by risk category.

The guideline divides screening recommendations into basic and enhanced. The basic screening should include a comprehensive history and physical exam, complete blood count, liver functions tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rates/plasma viscosity, serum protein electrophoresis, urinalysis, and chest x-ray.

Adults with IIM who are determined to be at low risk for IIM-related cancer should have basic cancer screening at the time of IIM diagnosis. Adults with intermediate risk should undergo both basic and enhanced screening at the time of IIM diagnosis, and those with high risk should undergo enhanced screening at the time of myositis diagnosis, with basic screening annually for 3 years, the recommendations say.

Consider doing this

Conditional recommendations (“clinicians should consider ...”) include the use of PET/CT for adults at high risk for cancer when an underlying cancer has not been detected at the time of IIM diagnosis. They also include a single screening test for anti-TIF1-gamma positive dermatomyositis patients whose disease onset was after age 40 and who have at least one additional risk factor.

Also conditionally recommended are upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy for patients at high risk when an underlying cancer is not found at the time of IIM diagnosis, nasoendoscopy in geographical regions with elevated risk for nasopharyngeal cancers, and screening for all IIM patients with red-flag symptoms or clinical features of cancer, including unexplained weight loss, family history of cancer, smoking, unexplained fever, or night sweats.

Guided steps

“I think clinicians have a lot of questions such as, ‘well, what should I do, when should I do it?’ These are important clinical questions, and we need guidance about this. We need to balance comprehensiveness with cost-effectiveness, and we need expert opinion about what steps we should take now and which should we take later,” Dr. Kolasinski said.

The guideline development process was supported by the University of Manchester, IMACS, National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), National Institutes of Health, National Health Service Northern Care Alliance, The Myositis Association, Myositis UK, University of Pittsburgh, Versus Arthritis, and the Center for Musculoskeletal Research. Dr. Oldroyd and Dr. Kolasinski reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Treating deadly disease in utero called ‘revolutionary’ advance

The successful treatment of Pompe disease in utero for the first time may be the start of a new chapter for fetal therapy, researchers said.

A report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine describes in utero enzyme-replacement therapy (ERT) for infantile-onset Pompe disease.

The patient, now a toddler, is thriving, according to the researchers. Her parents previously had children with the same disorder who died.

“This treatment expands the repertoire of fetal therapies in a new direction,” Tippi MacKenzie, MD, a pediatric surgeon with University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospitals and a coauthor of the report, said in a news release. “As new treatments become available for children with genetic conditions, we are developing protocols to apply them before birth.”

Dr. MacKenzie codirects the University of California, San Francisco’s center for maternal-fetal precision medicine and directs the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research.

Pompe disease is caused by mutations in a gene that makes acid alpha-glucosidase. With limited amounts of this enzyme, dangerous amounts of glycogen accumulate in the body. Babies with infantile-onset disease typically have enlarged hearts and die by age 2 years.

The condition, which occurs in an estimated 1 in 40,000 births, is one of several early-onset lysosomal storage disorders. Patients with these diseases “are ideal candidates for prenatal therapy because organ damage starts in utero,” the researchers said.

Newborn screening can lead to early initiation of treatment with recombinant enzymes, “but this strategy does not completely prevent irreversible organ damage,” the authors said.

The patient in the new report received six prenatal ERT treatments at the Ottawa Hospital and is receiving postnatal enzyme therapy at CHEO, a pediatric hospital and research center in Ottawa.

Investigators administered alglucosidase alfa through the umbilical vein. They delivered the first infusion to the fetus at 24 weeks 5 days of gestation. They continued providing infusions at 2-week intervals through 34 weeks 5 days of gestation.

She is doing well at age 16 months, with normal cardiac and motor function, and is meeting developmental milestones, according to the news release.

The successful treatment involved collaboration among the University of California, San Francisco, where researchers are conducting a clinical trial of this treatment approach; CHEO and the Ottawa Hospital; and Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Under normal circumstances, the patient’s family would have traveled to Benioff Children’s Hospitals fetal treatment center to participate in the clinical trial, but COVID-19 restrictions led the researchers to deliver the therapy to Ottawa as part of the trial.

The University of California, San Francisco, has received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to treat Pompe disease and several other lysosomal storage disorders in utero as part of a phase 1 clinical trial with 10 patients. The other diseases are mucopolysaccharidosis types 1, 2, 4a, 6, and 7; Gaucher disease types 2 and 3; and Wolman disease.

Patients with Pompe disease might typically be diagnosed clinically at age 3-6 months, said study coauthor Paul Harmatz, MD, with the University of California, San Francisco. With newborn screening, the disease might be diagnosed at 1 week. But intervening before birth may be optimal, Dr. Harmatz said.

Fetal treatment appears to be “revolutionary at this point,” Dr. Harmatz said.

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi Genzyme provided the enzyme for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The successful treatment of Pompe disease in utero for the first time may be the start of a new chapter for fetal therapy, researchers said.

A report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine describes in utero enzyme-replacement therapy (ERT) for infantile-onset Pompe disease.

The patient, now a toddler, is thriving, according to the researchers. Her parents previously had children with the same disorder who died.

“This treatment expands the repertoire of fetal therapies in a new direction,” Tippi MacKenzie, MD, a pediatric surgeon with University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospitals and a coauthor of the report, said in a news release. “As new treatments become available for children with genetic conditions, we are developing protocols to apply them before birth.”

Dr. MacKenzie codirects the University of California, San Francisco’s center for maternal-fetal precision medicine and directs the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research.

Pompe disease is caused by mutations in a gene that makes acid alpha-glucosidase. With limited amounts of this enzyme, dangerous amounts of glycogen accumulate in the body. Babies with infantile-onset disease typically have enlarged hearts and die by age 2 years.

The condition, which occurs in an estimated 1 in 40,000 births, is one of several early-onset lysosomal storage disorders. Patients with these diseases “are ideal candidates for prenatal therapy because organ damage starts in utero,” the researchers said.

Newborn screening can lead to early initiation of treatment with recombinant enzymes, “but this strategy does not completely prevent irreversible organ damage,” the authors said.

The patient in the new report received six prenatal ERT treatments at the Ottawa Hospital and is receiving postnatal enzyme therapy at CHEO, a pediatric hospital and research center in Ottawa.

Investigators administered alglucosidase alfa through the umbilical vein. They delivered the first infusion to the fetus at 24 weeks 5 days of gestation. They continued providing infusions at 2-week intervals through 34 weeks 5 days of gestation.

She is doing well at age 16 months, with normal cardiac and motor function, and is meeting developmental milestones, according to the news release.

The successful treatment involved collaboration among the University of California, San Francisco, where researchers are conducting a clinical trial of this treatment approach; CHEO and the Ottawa Hospital; and Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Under normal circumstances, the patient’s family would have traveled to Benioff Children’s Hospitals fetal treatment center to participate in the clinical trial, but COVID-19 restrictions led the researchers to deliver the therapy to Ottawa as part of the trial.

The University of California, San Francisco, has received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to treat Pompe disease and several other lysosomal storage disorders in utero as part of a phase 1 clinical trial with 10 patients. The other diseases are mucopolysaccharidosis types 1, 2, 4a, 6, and 7; Gaucher disease types 2 and 3; and Wolman disease.

Patients with Pompe disease might typically be diagnosed clinically at age 3-6 months, said study coauthor Paul Harmatz, MD, with the University of California, San Francisco. With newborn screening, the disease might be diagnosed at 1 week. But intervening before birth may be optimal, Dr. Harmatz said.

Fetal treatment appears to be “revolutionary at this point,” Dr. Harmatz said.

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi Genzyme provided the enzyme for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The successful treatment of Pompe disease in utero for the first time may be the start of a new chapter for fetal therapy, researchers said.

A report published online in the New England Journal of Medicine describes in utero enzyme-replacement therapy (ERT) for infantile-onset Pompe disease.

The patient, now a toddler, is thriving, according to the researchers. Her parents previously had children with the same disorder who died.

“This treatment expands the repertoire of fetal therapies in a new direction,” Tippi MacKenzie, MD, a pediatric surgeon with University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospitals and a coauthor of the report, said in a news release. “As new treatments become available for children with genetic conditions, we are developing protocols to apply them before birth.”

Dr. MacKenzie codirects the University of California, San Francisco’s center for maternal-fetal precision medicine and directs the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research.

Pompe disease is caused by mutations in a gene that makes acid alpha-glucosidase. With limited amounts of this enzyme, dangerous amounts of glycogen accumulate in the body. Babies with infantile-onset disease typically have enlarged hearts and die by age 2 years.

The condition, which occurs in an estimated 1 in 40,000 births, is one of several early-onset lysosomal storage disorders. Patients with these diseases “are ideal candidates for prenatal therapy because organ damage starts in utero,” the researchers said.

Newborn screening can lead to early initiation of treatment with recombinant enzymes, “but this strategy does not completely prevent irreversible organ damage,” the authors said.

The patient in the new report received six prenatal ERT treatments at the Ottawa Hospital and is receiving postnatal enzyme therapy at CHEO, a pediatric hospital and research center in Ottawa.

Investigators administered alglucosidase alfa through the umbilical vein. They delivered the first infusion to the fetus at 24 weeks 5 days of gestation. They continued providing infusions at 2-week intervals through 34 weeks 5 days of gestation.

She is doing well at age 16 months, with normal cardiac and motor function, and is meeting developmental milestones, according to the news release.

The successful treatment involved collaboration among the University of California, San Francisco, where researchers are conducting a clinical trial of this treatment approach; CHEO and the Ottawa Hospital; and Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Under normal circumstances, the patient’s family would have traveled to Benioff Children’s Hospitals fetal treatment center to participate in the clinical trial, but COVID-19 restrictions led the researchers to deliver the therapy to Ottawa as part of the trial.

The University of California, San Francisco, has received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to treat Pompe disease and several other lysosomal storage disorders in utero as part of a phase 1 clinical trial with 10 patients. The other diseases are mucopolysaccharidosis types 1, 2, 4a, 6, and 7; Gaucher disease types 2 and 3; and Wolman disease.

Patients with Pompe disease might typically be diagnosed clinically at age 3-6 months, said study coauthor Paul Harmatz, MD, with the University of California, San Francisco. With newborn screening, the disease might be diagnosed at 1 week. But intervening before birth may be optimal, Dr. Harmatz said.

Fetal treatment appears to be “revolutionary at this point,” Dr. Harmatz said.

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Sanofi Genzyme provided the enzyme for the patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in an Infant

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

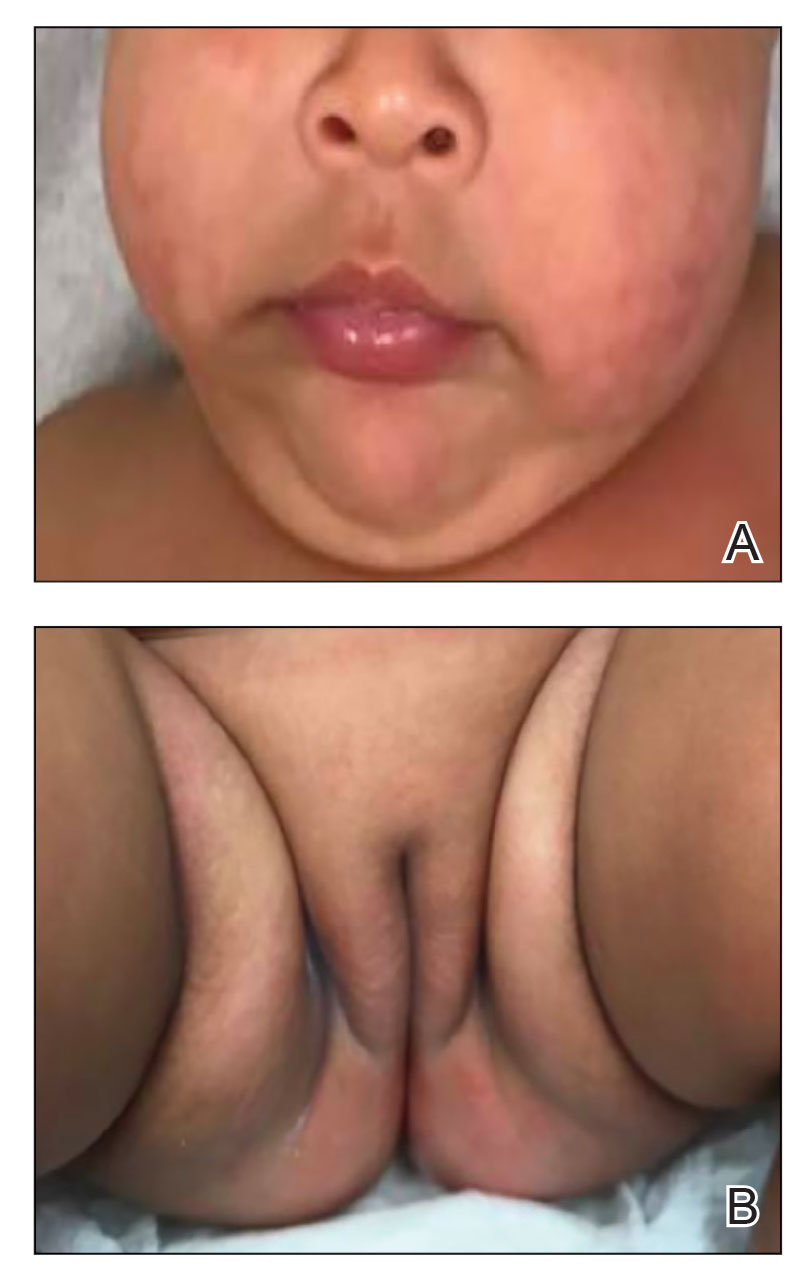

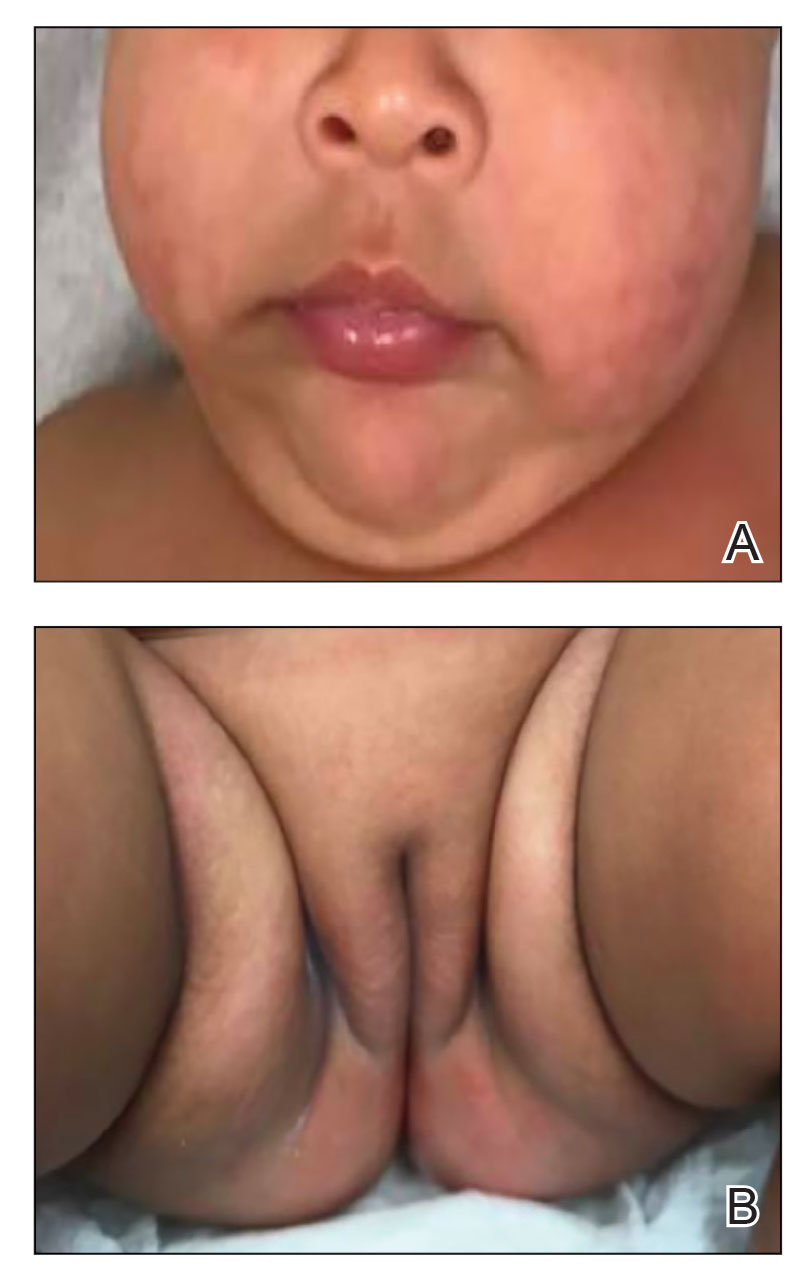

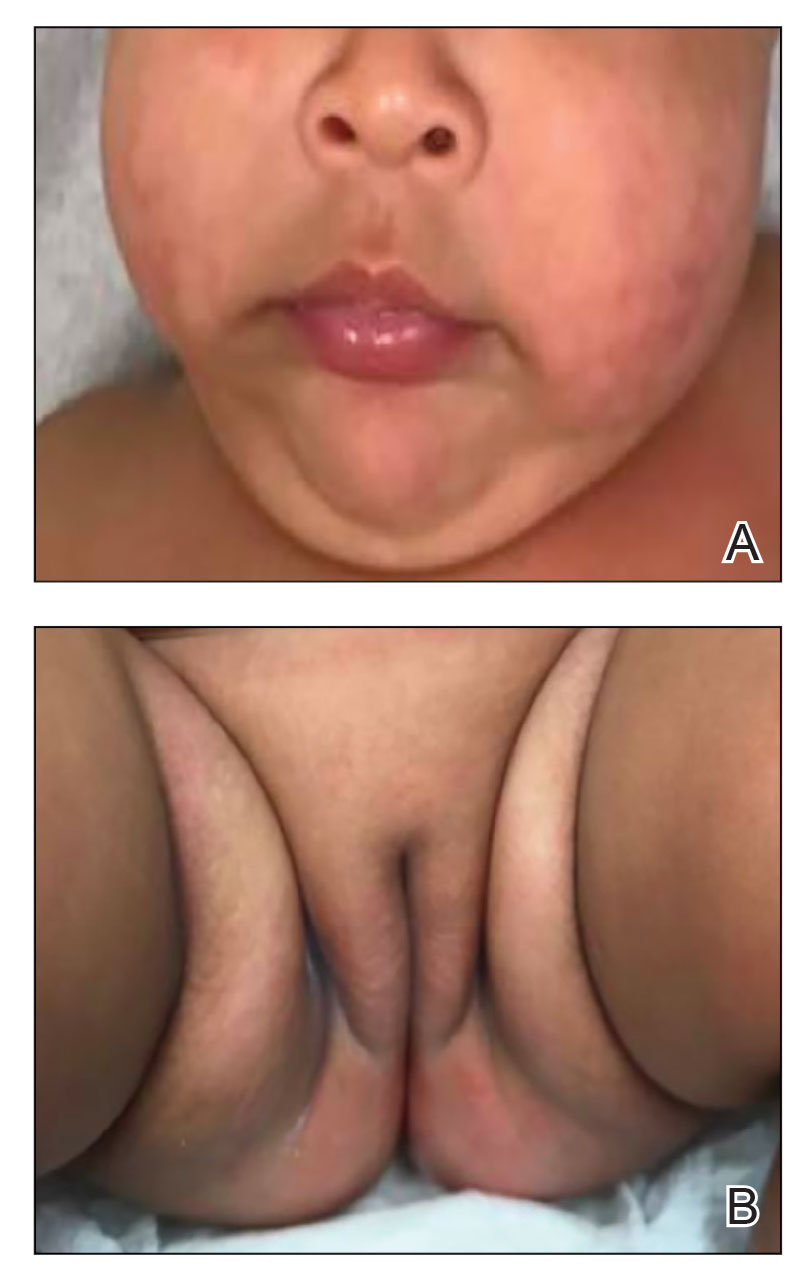

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

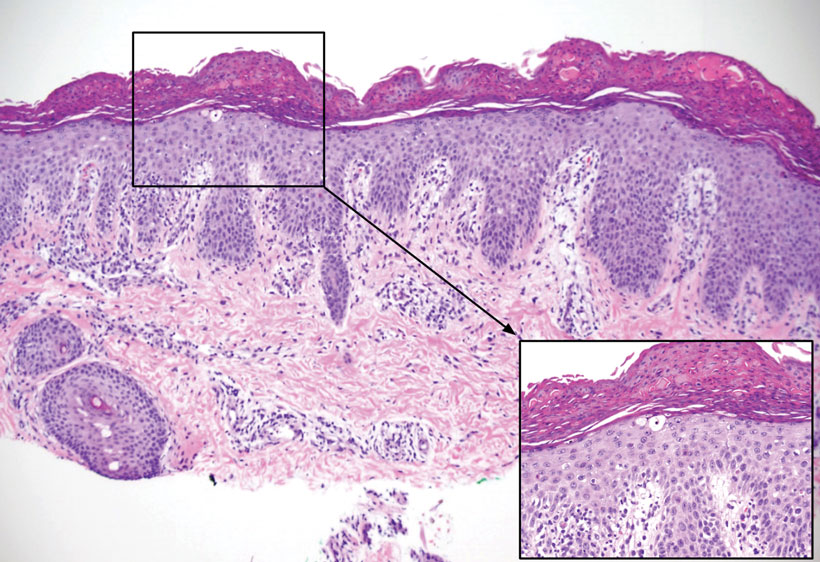

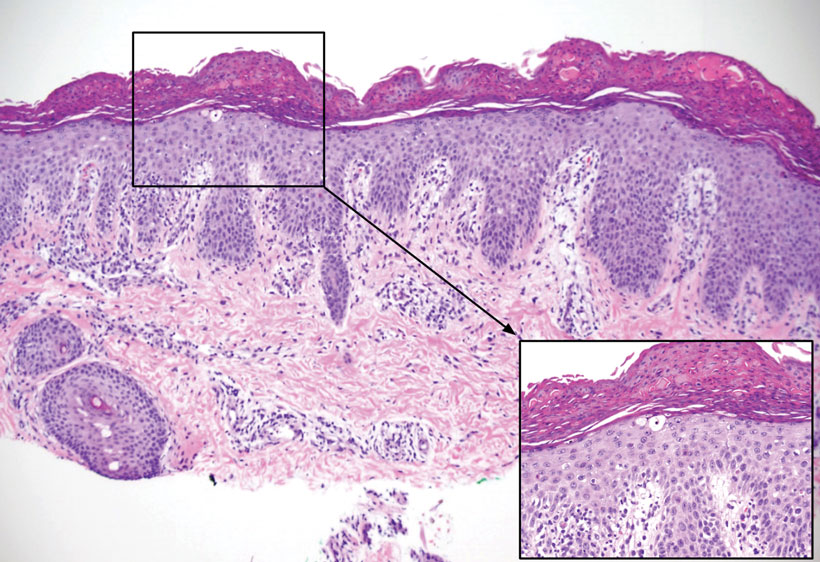

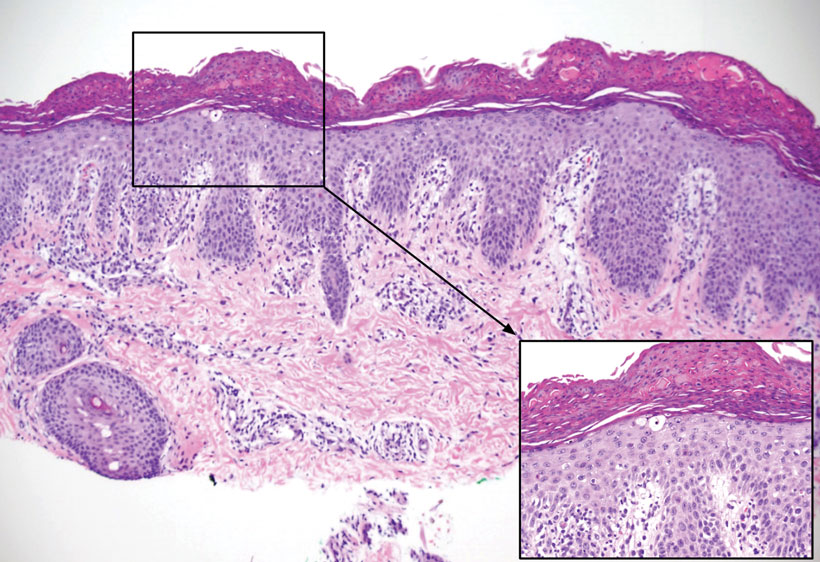

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare disorder of zinc metabolism that typically presents in infancy.1 Although it is clinically characterized by acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, only 20% of cases present with this triad.2 Zinc deficiency in AE can either be acquired or inborn (congenital). Acquired forms can occur from dietary inadequacy or malabsorption, whereas genetic causes are related to an autosomal-recessive disorder affecting zinc transporters.1 We report a case of a 3-month-old female infant with acquired AE who was successfully treated with zinc supplementation over the course of 3 weeks.

Case Report

A 3-month-old female infant presented to the emergency department with a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She was born full term with no birth complications. The patient’s mother reported that the rash started on the cheeks, then enlarged and spread to the neck, back, and perineum. The patient also had been having diarrhea during this time. She previously had received mupirocin and cephalexin with no response to treatment. Maternal history was negative for lupus, and the mother’s diet consisted of a variety of foods but not many vegetables. The patient was exclusively breastfed, and there was no pertinent history of similar rashes occurring in other family members.

Physical examination revealed the patient had annular and polycyclic, hyperkeratotic, crusted papules and plaques on the cheeks, neck, back, and axillae, as well as the perineum/groin and perianal regions (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis at the time included neonatal lupus, zinc deficiency, and syphilis. Relevant laboratory testing and a shave biopsy of the left axilla were obtained.

Pertinent laboratory findings included a low zinc level (23 μg/dL [reference range, 26–141 μg/dL]), low alkaline phosphatase level (74 U/L [reference range, 94–486 U/L]), and thrombocytosis (826×109/L [reference range, 150–400×109/L). Results for antinuclear antibody and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A and B antibody testing were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test was nonreactive. Histologic examination revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia with overlying confluent parakeratosis, focal spongiosis, multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and mitotic figures (Figure 2). Ballooning was evident in focal cells in the subcorneal region in addition to an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils.

The patient was given a 10-mg/mL suspension of elemental zinc and was advised to take 1 mL (10 mg) by mouth twice daily with food. This dosage equated to 3 mg/kg/d. On follow-up 3 weeks later, the skin began to clear (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory testing showed an increase in zinc (114 μg/dL) and alkaline phosphatase levels (313 U/L). The patient was able to discontinue the zinc supplementation, and follow-up during the next year revealed no recurrence.

Comment

Etiology of AE—Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first identified in 1942 as an acral rash associated with diarrhea3; in 1973, Barnes and Moynahan4 discovered zinc deficiency as a causal agent for these findings. The causes of AE are further subclassified as either an acquired or inborn etiology. Congenital causes commonly are seen in infants within the first few months of life, whereas acquired forms are seen at any age. Acquired forms in infants can occur from failure of the mother to secrete zinc in breast milk, low maternal serum zinc levels, or other reasons causing low nutritional intake. A single mutation in the SLC30A2 gene has been found to markedly reduce zinc concentrations in breast milk, thus causing zinc deficiency in breastfed infants.5 Other acquired forms can be caused by malabsorption, sometimes after surgery such as intestinal bypass or from intravenous nutrition without sufficient zinc.1 The congenital form of AE is an autosomal-recessive disorder occurring from mutations in the SLC39A4 gene located on band 8q24.3. Affected individuals have a decreased ability to absorb zinc in the small intestine because of defects in zinc transporters ZIP and ZnT.6 Based on our patient’s laboratory findings and history, it is believed that the zinc deficiency was acquired, as the condition normalized with repletion and has not required any supplementation in the year of follow-up. In addition, the absence of a pertinent family history supported an acquired diagnosis, which has various etiologies, whereas the congenital form primarily is a genetic disease.

Management—Treatment of AE includes supplementation with oral elemental zinc; however, there are scant evidence-based recommendations on the exact dose of zinc to be given. Generally, the recommended amount is 3 mg/kg/d.8 For individuals with the congenital form of AE, lifelong zinc supplementation is additionally recommended.9 It is important to recognize this presentation because the patient can develop worsening irritability, severe diarrhea, nail dystrophy, hair loss, immune dysfunction, and numerous ophthalmic disorders if left untreated. Acute zinc toxicity due to excess administration is rare, with symptoms of nausea and vomiting occurring with dosages of 50 to 100 mg/d. Additionally, dosages of up to 70 mg twice weekly have been provided without any toxic effect.10 In our case, 3 mg/kg/d of oral zinc supplementation proved to be effective in resolving the patient’s symptoms of acquired zinc deficiency.

Differential Diagnosis—It is important to note that deficiencies of other nutrients may present as an AE-like eruption called acrodermatitis dysmetabolica (AD). Both diseases may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea; however, AD is associated with inborn errors of metabolism. There have been cases that describe AD in patients with a zinc deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids.11,12 It is important to consider AD in the differential diagnosis of an AE eruption, especially in the context of a metabolic disorder, as it may affect the treatment plan. One case described the dermatitis of AD as not responding to zinc supplementation alone, while another described improvement after increasing an isoleucine supplementation dose.11,12

Other considerations in the differential diagnoses include AE-like conditions such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and essential fatty acid deficiency. An AE-like condition may present with the triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. However, unlike in true AE, zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels tend to be normal in these conditions. Other features seen in AE-like conditions depend on the underlying cause but often include failure to thrive, neurologic defects, ophthalmic abnormalities, and metabolic abnormalities.13

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Danbolt N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:37-40.

- Barnes PM, Moynahan EJ. Zinc deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica: multiple dietary intolerance treated with synthetic diet. Proc R Soc Med. 1973;66:327-329.

- Lee S, Zhou Y, Gill DL, et al. A genetic variant in SLC30A2 causes breast dysfunction during lactation by inducing ER stress, oxidative stress and epithelial barrier defects. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3542.

- Kaur S, Sangwan A, Sahu P, et al. Clinical variants of acrodermatitis enteropathica and its co-relation with genetics. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2016;17:35-37.

- Dela Rosa KM, James WD. Acrodermatitis enteropathica workup. Medscape. Updated June 4, 2021. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1102575-workup#showall

- Ngan V, Gangakhedkar A, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. DermNet. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica/

- Ranugha P, Sethi P, Veeranna S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: the need for sustained high dose zinc supplementation. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1w9002sr.

- Larson CP, Roy SK, Khan AI, et al. Zinc treatment to under-five children: applications to improve child survival and reduce burden of disease. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:356-365.

- Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000;27:604-608.

- Flores K, Chikowski R, Morrell DS. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica in an infant with maple syrup urine disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:651-654.

- Jones L, Oakley A. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like conditions. DermNet. Accessed August 30, 2022. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/acrodermatitis-enteropathica-like-conditions

Practice Points

- Although clinically characterized by the triad of acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea, most cases of acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) present with only partial features of this syndrome.

- Low levels of zinc-dependent enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase may support the diagnosis of AE.

Gene ‘cut-and-paste’ treatment could offer hope for inherited immune system diseases

An “exciting” new gene-editing strategy means those born with a rare inherited disease of the immune system could be treated by repairing a fault in their cells.

CTLA-4 is a protein produced by T cells that helps to control the activity of the immune system. Most people carry two working copies of the gene responsible for producing CTLA-4, but those who have only one functional copy produce too little of the protein to sufficiently regulate the immune system.

For patients with the condition, CTLA-4 insufficiency causes regulatory T cells to function abnormally, leading to severe autoimmunity. The authors explained that the condition also affects effector T cells and thereby “hampers their immune system’s ‘memory,’ ” meaning patients can “struggle to fight off recurring infections by the same viruses and bacteria.” In some cases, it can also lead to lymphomas.

Gene editing to ‘cut’ out faulty genes and ‘paste’ in ‘corrected’ ones

The research, published in Science Translational Medicine, and led by scientists from University College London, demonstrated in human cells and in mice that the cell fault can be repaired.

The scientists used “cut-and-paste” gene-editing techniques. First, they used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to target the faulty gene in human T cells taken from patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency, and then snip the faulty CTLA-4 gene in two. Then, to repair the errors a corrected sequence of DNA – delivered to the cell using a modified virus – was pasted over the faulty part of the gene using a cellular DNA repair mechanism known as homology-directed repair.

The authors explained that this allowed them to “preserve” important sequences within the CTLA-4 gene – known as the intron – that allow it to be switched on and off by the cell only when needed.

The outcome was “restored levels of CTLA-4 in the cells to those seen in healthy T cells,” the authors said.

Claire Booth, PhD, Mahboubian professor of gene therapy and pediatric immunology, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, and co–senior author, said that it was “really exciting” to think about taking this treatment forward to patients. “If we can improve their symptoms and reduce their risk of getting lymphoproliferative disease this will be a major step forward.”

In addition, the researchers were also able to improve symptoms of the disease in mice with CTLA-4 insufficiency by giving them injections of gene-edited T cells.

Technique may help tackle many conditions

The current standard treatment for CTLA-4 insufficiency is a bone marrow transplant to replace the stem cells responsible for producing T cells. However, “transplants are risky” and require high doses of chemotherapy and many weeks in hospital, the authors explained. “Older patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency are typically not well enough to tolerate the transplant procedure.”

Dr. Booth highlighted that the approach has many “positive aspects”. By correcting the patient’s T cells, “we think it can improve many of the symptoms of the disease”, she said, and added that this new approach is much less toxic than a bone marrow transplant. “Collecting the T cells is easier and correcting the T cells is easier. With this approach the amount of time in hospital the patients would need would be far less.”

Emma Morris, PhD, professor of clinical cell and gene therapy and director of UCL’s division of infection and immunity, and co–senior author, said: “Genes that play critical roles in controlling immune responses are not switched on all the time and are very tightly regulated. The technique we have used allows us to leave the natural (endogenous) mechanisms controlling gene expression intact, at the same time as correcting the mistake in the gene itself.”

The researchers explained that, although CTLA-4 insufficiency is rare, the gene editing therapy could be a proof of principle of their approach that could be adapted to tackle other conditions.

“It’s a way of correcting genetic mutations that could potentially be applicable for other diseases,” suggested Dr. Morris. “The bigger picture is it allows us to correct genes that are dysregulated or overactive, but also allows us to understand much more about gene expression and gene regulation.”

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Association for Moleculary Pathology, the Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and the UCLH/UCL NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Morris is a founder sharehold of Quell Therapeutics and has received honoraria from Orchard Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Booth has performed ad hoc consulting in the past 3 years for SOBI and Novartis and educational material production for SOBI and Chiesi. A patent on the intronic gene editing approach has been filed in the UK. The other authors declared that they have no completing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

An “exciting” new gene-editing strategy means those born with a rare inherited disease of the immune system could be treated by repairing a fault in their cells.

CTLA-4 is a protein produced by T cells that helps to control the activity of the immune system. Most people carry two working copies of the gene responsible for producing CTLA-4, but those who have only one functional copy produce too little of the protein to sufficiently regulate the immune system.

For patients with the condition, CTLA-4 insufficiency causes regulatory T cells to function abnormally, leading to severe autoimmunity. The authors explained that the condition also affects effector T cells and thereby “hampers their immune system’s ‘memory,’ ” meaning patients can “struggle to fight off recurring infections by the same viruses and bacteria.” In some cases, it can also lead to lymphomas.

Gene editing to ‘cut’ out faulty genes and ‘paste’ in ‘corrected’ ones

The research, published in Science Translational Medicine, and led by scientists from University College London, demonstrated in human cells and in mice that the cell fault can be repaired.

The scientists used “cut-and-paste” gene-editing techniques. First, they used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to target the faulty gene in human T cells taken from patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency, and then snip the faulty CTLA-4 gene in two. Then, to repair the errors a corrected sequence of DNA – delivered to the cell using a modified virus – was pasted over the faulty part of the gene using a cellular DNA repair mechanism known as homology-directed repair.

The authors explained that this allowed them to “preserve” important sequences within the CTLA-4 gene – known as the intron – that allow it to be switched on and off by the cell only when needed.

The outcome was “restored levels of CTLA-4 in the cells to those seen in healthy T cells,” the authors said.

Claire Booth, PhD, Mahboubian professor of gene therapy and pediatric immunology, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, and co–senior author, said that it was “really exciting” to think about taking this treatment forward to patients. “If we can improve their symptoms and reduce their risk of getting lymphoproliferative disease this will be a major step forward.”

In addition, the researchers were also able to improve symptoms of the disease in mice with CTLA-4 insufficiency by giving them injections of gene-edited T cells.

Technique may help tackle many conditions

The current standard treatment for CTLA-4 insufficiency is a bone marrow transplant to replace the stem cells responsible for producing T cells. However, “transplants are risky” and require high doses of chemotherapy and many weeks in hospital, the authors explained. “Older patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency are typically not well enough to tolerate the transplant procedure.”

Dr. Booth highlighted that the approach has many “positive aspects”. By correcting the patient’s T cells, “we think it can improve many of the symptoms of the disease”, she said, and added that this new approach is much less toxic than a bone marrow transplant. “Collecting the T cells is easier and correcting the T cells is easier. With this approach the amount of time in hospital the patients would need would be far less.”

Emma Morris, PhD, professor of clinical cell and gene therapy and director of UCL’s division of infection and immunity, and co–senior author, said: “Genes that play critical roles in controlling immune responses are not switched on all the time and are very tightly regulated. The technique we have used allows us to leave the natural (endogenous) mechanisms controlling gene expression intact, at the same time as correcting the mistake in the gene itself.”

The researchers explained that, although CTLA-4 insufficiency is rare, the gene editing therapy could be a proof of principle of their approach that could be adapted to tackle other conditions.

“It’s a way of correcting genetic mutations that could potentially be applicable for other diseases,” suggested Dr. Morris. “The bigger picture is it allows us to correct genes that are dysregulated or overactive, but also allows us to understand much more about gene expression and gene regulation.”

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Association for Moleculary Pathology, the Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and the UCLH/UCL NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Morris is a founder sharehold of Quell Therapeutics and has received honoraria from Orchard Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Booth has performed ad hoc consulting in the past 3 years for SOBI and Novartis and educational material production for SOBI and Chiesi. A patent on the intronic gene editing approach has been filed in the UK. The other authors declared that they have no completing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

An “exciting” new gene-editing strategy means those born with a rare inherited disease of the immune system could be treated by repairing a fault in their cells.

CTLA-4 is a protein produced by T cells that helps to control the activity of the immune system. Most people carry two working copies of the gene responsible for producing CTLA-4, but those who have only one functional copy produce too little of the protein to sufficiently regulate the immune system.

For patients with the condition, CTLA-4 insufficiency causes regulatory T cells to function abnormally, leading to severe autoimmunity. The authors explained that the condition also affects effector T cells and thereby “hampers their immune system’s ‘memory,’ ” meaning patients can “struggle to fight off recurring infections by the same viruses and bacteria.” In some cases, it can also lead to lymphomas.

Gene editing to ‘cut’ out faulty genes and ‘paste’ in ‘corrected’ ones

The research, published in Science Translational Medicine, and led by scientists from University College London, demonstrated in human cells and in mice that the cell fault can be repaired.

The scientists used “cut-and-paste” gene-editing techniques. First, they used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to target the faulty gene in human T cells taken from patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency, and then snip the faulty CTLA-4 gene in two. Then, to repair the errors a corrected sequence of DNA – delivered to the cell using a modified virus – was pasted over the faulty part of the gene using a cellular DNA repair mechanism known as homology-directed repair.

The authors explained that this allowed them to “preserve” important sequences within the CTLA-4 gene – known as the intron – that allow it to be switched on and off by the cell only when needed.

The outcome was “restored levels of CTLA-4 in the cells to those seen in healthy T cells,” the authors said.

Claire Booth, PhD, Mahboubian professor of gene therapy and pediatric immunology, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, and co–senior author, said that it was “really exciting” to think about taking this treatment forward to patients. “If we can improve their symptoms and reduce their risk of getting lymphoproliferative disease this will be a major step forward.”

In addition, the researchers were also able to improve symptoms of the disease in mice with CTLA-4 insufficiency by giving them injections of gene-edited T cells.

Technique may help tackle many conditions

The current standard treatment for CTLA-4 insufficiency is a bone marrow transplant to replace the stem cells responsible for producing T cells. However, “transplants are risky” and require high doses of chemotherapy and many weeks in hospital, the authors explained. “Older patients with CTLA-4 insufficiency are typically not well enough to tolerate the transplant procedure.”

Dr. Booth highlighted that the approach has many “positive aspects”. By correcting the patient’s T cells, “we think it can improve many of the symptoms of the disease”, she said, and added that this new approach is much less toxic than a bone marrow transplant. “Collecting the T cells is easier and correcting the T cells is easier. With this approach the amount of time in hospital the patients would need would be far less.”

Emma Morris, PhD, professor of clinical cell and gene therapy and director of UCL’s division of infection and immunity, and co–senior author, said: “Genes that play critical roles in controlling immune responses are not switched on all the time and are very tightly regulated. The technique we have used allows us to leave the natural (endogenous) mechanisms controlling gene expression intact, at the same time as correcting the mistake in the gene itself.”

The researchers explained that, although CTLA-4 insufficiency is rare, the gene editing therapy could be a proof of principle of their approach that could be adapted to tackle other conditions.

“It’s a way of correcting genetic mutations that could potentially be applicable for other diseases,” suggested Dr. Morris. “The bigger picture is it allows us to correct genes that are dysregulated or overactive, but also allows us to understand much more about gene expression and gene regulation.”

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Association for Moleculary Pathology, the Medical Research Council, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and the UCLH/UCL NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Morris is a founder sharehold of Quell Therapeutics and has received honoraria from Orchard Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Booth has performed ad hoc consulting in the past 3 years for SOBI and Novartis and educational material production for SOBI and Chiesi. A patent on the intronic gene editing approach has been filed in the UK. The other authors declared that they have no completing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Goodbye ‘diabetes insipidus’, hello ‘AVP-D’ and ‘AVP-R’

An international group representing leading endocrinology associations has recommended that the name “diabetes insipidus” – which in some cases has led to harm – be changed to eliminate confusion with “diabetes mellitus” and to reflect the former condition’s pathophysiology.

The new proposed names are arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D) for central (also called “cranial”) etiologies and arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R) for nephrogenic (kidney) etiologies.

“What we’re proposing is to rename the disease according to the pathophysiology that defines it,” statement co-author Joseph G. Verbalis, MD, professor of medicine and chief of endocrinology and metabolism at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization.

The statement advises that henceforth the new names be used in manuscripts and the medical literature while keeping the old names in parentheses during a transition period, as in “AVP-deficiency (cranial diabetes insipidus)” and “AVP-resistance (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus).”

The condition formerly known as diabetes insipidus is relatively rare, occurring in about 1 person per 10-15,000 population. It is caused by either deficient production or resistance in the kidney to the hormone AVP, normally produced by the hypothalamus and stored in the pituitary gland. AVP, also called antidiuretic hormone, regulates the body’s water level and urine production by the kidney.

Both etiologies lead to extreme thirst and excessive production of urine. Common causes of the deficiency include head trauma or brain tumor, while resistance in the kidney is often congenital. It is currently treated with a synthetic form of AVP called desmopressin and fluid replacement.

What’s in a name?

The proposal to change the name by the Working Group for Renaming Diabetes Insipidus is endorsed by The Endocrine Society, European Society of Endocrinology, Pituitary Society, Society for Endocrinology, European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology, Endocrine Society of Australia, Brazilian Endocrine Society, and Japanese Endocrine Society and is under review by several other societies. It was published as a position statement in several of those society’s journals, with more to follow.

Historically, the word “diabetes,” a Greek word meaning “siphon,” was used in the 1st and 2nd century BC to describe excess flow of urine. The Latin word “mellitus” or “honey” was added in the late 17th century to describe the sweetness of the urine in the dysglycemic condition.

A century later, the Latin word “insipidus,” meaning insipid or tasteless, was coined to distinguish between the two types of polyuria, the position statement details.

In the late 19th to early 20th century, the vasopressor and antidiuretic actions of posterior pituitary extracts were discovered and used to treat people with both the central and nephrogenic etiologies, which were also recognized around that time, yet the name “diabetes insipidus” has persisted.

“From a historical perspective, the name is perfectly appropriate. At the time it was identified, and it was realized that it was different from diabetes mellitus, that was a perfectly appropriate terminology based on what was known in the late 19th century – but not now. It has persisted through the years simply because in medicine there’s a lot of inertia for change ... It’s just always been called that. If there’s not a compelling reason to change a name, generally there’s no move to change it,” Dr. Verbalis observed.

‘Dramatic cases of patient mismanagement’ due to name confusion

Unfortunately, the urgency for the change arose from tragedy. In 2009, a 22-year-old man was admitted to the orthopedics department of a London teaching hospital for a hip replacement. Despite his known panhypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus, the nurses continually checked his blood glucose but didn’t give him desmopressin or sufficient fluids. Laboratory testing showed normal glucose, but his serum sodium was 149 mmol/L. The morning after his operation, he had a fatal cardiac arrest with a serum sodium of 169 mmol/L.

“The nurses thought he had diabetes mellitus ... So that was death due to failure to recognize that diabetes insipidus is not diabetes mellitus,” Dr. Verbalis said. “If he had been admitted to endocrinology, this wouldn’t have happened. But he was admitted to orthopedics. Non-endocrinologists are not so aware of diabetes insipidus, because it is a rare disease.”

In 2016, National Health Service England issued a patient safety alert about the “risk of severe harm or death when desmopressin is omitted or delayed in patients with cranial diabetes insipidus,” citing at least four incidents within the prior 7 years where omission of desmopressin had resulted in severe dehydration and death, with another 76 cases of omission or delay that were acted on before the patients became critically ill.

Further impetus for the name change came from the results of an anonymous web-based survey of 1,034 adult and pediatric patients with central diabetes insipidus conducted between August 2021 and February 2022. Overall, 80% reported encountering situations in which their condition had been confused with diabetes mellitus by health care professionals, and 85% supported renaming the disease.

There was some divergence in opinion as to what the new name(s) should be, but clear agreement that the term “diabetes” should not be part of it.

“We’ve only become recently aware that there are dramatic cases of patient mismanagement due to the confusion caused by the word ‘diabetes.’ We think patients should have a voice. If a legitimate patient survey says over 80% think this name should be changed, then I think we as endocrinologists need to pay attention to that,” Dr. Verbalis said.

But while endocrinologists are the ones who see these patients the most often, Dr. Verbalis said a main aim of the position statement “is really to change the mindset of non-endocrinologist doctors and nurses and other health care professionals that this is not diabetes mellitus. It’s a totally different disease. And if we give it a totally different name, then I think they will better recognize that.”

As to how long Dr. Verbalis thinks it will take for the new names to catch on, he pointed out that it’s taken about a decade for the rheumatology field to fully adopt the name “granulomatosis with polyangiitis” as a replacement for “Wegener’s granulomatosis” after the eponymous physician’s Nazi ties were revealed.

“So we’re not anticipating that this is going to change terminology tomorrow. It’s a long process. We just wanted to get the process started,” he said.

Dr. Verbalis has reported consulting for Otsuka.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An international group representing leading endocrinology associations has recommended that the name “diabetes insipidus” – which in some cases has led to harm – be changed to eliminate confusion with “diabetes mellitus” and to reflect the former condition’s pathophysiology.

The new proposed names are arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D) for central (also called “cranial”) etiologies and arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R) for nephrogenic (kidney) etiologies.