User login

Clinical Case-Viewing Sessions in Dermatology: The Patient Perspective

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

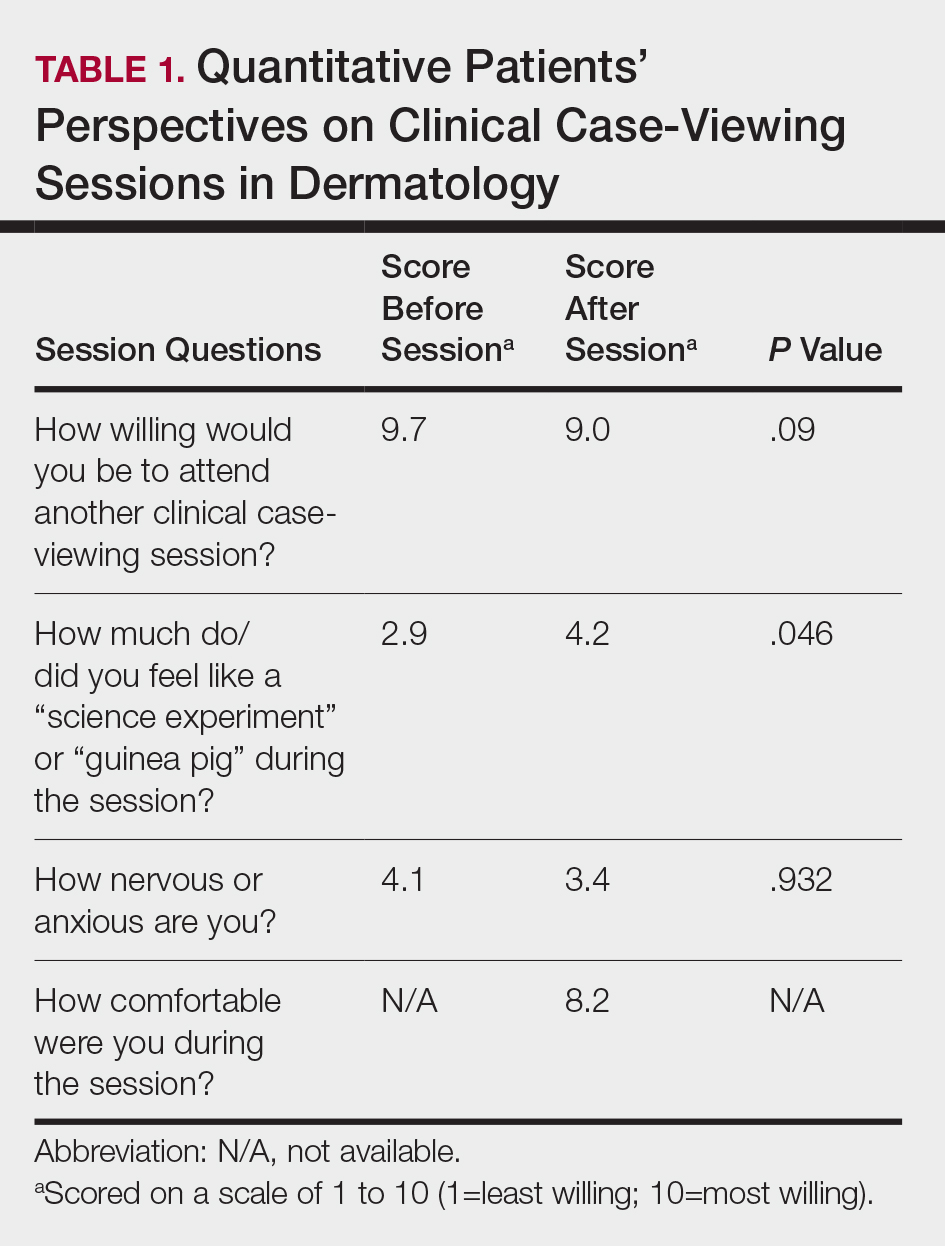

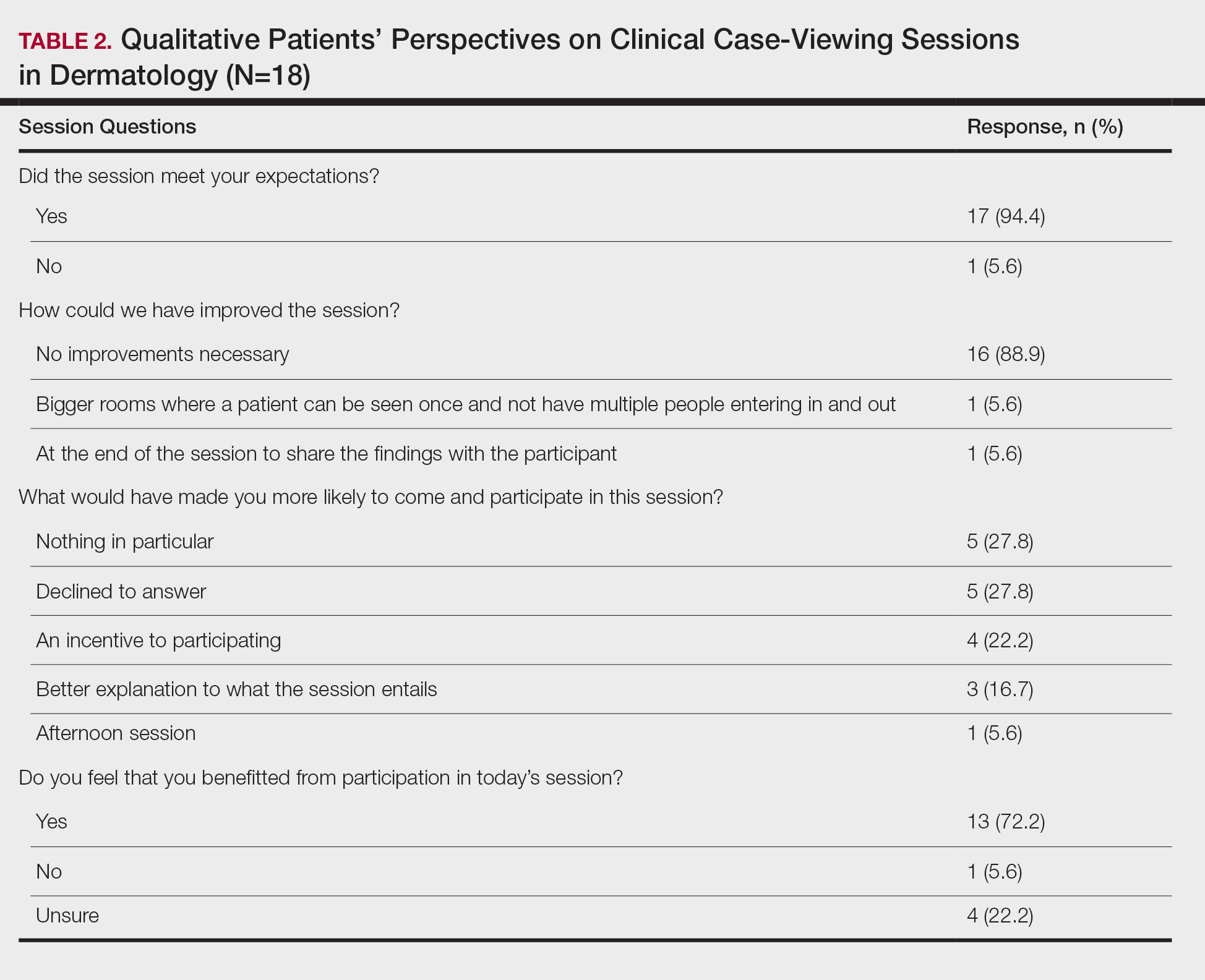

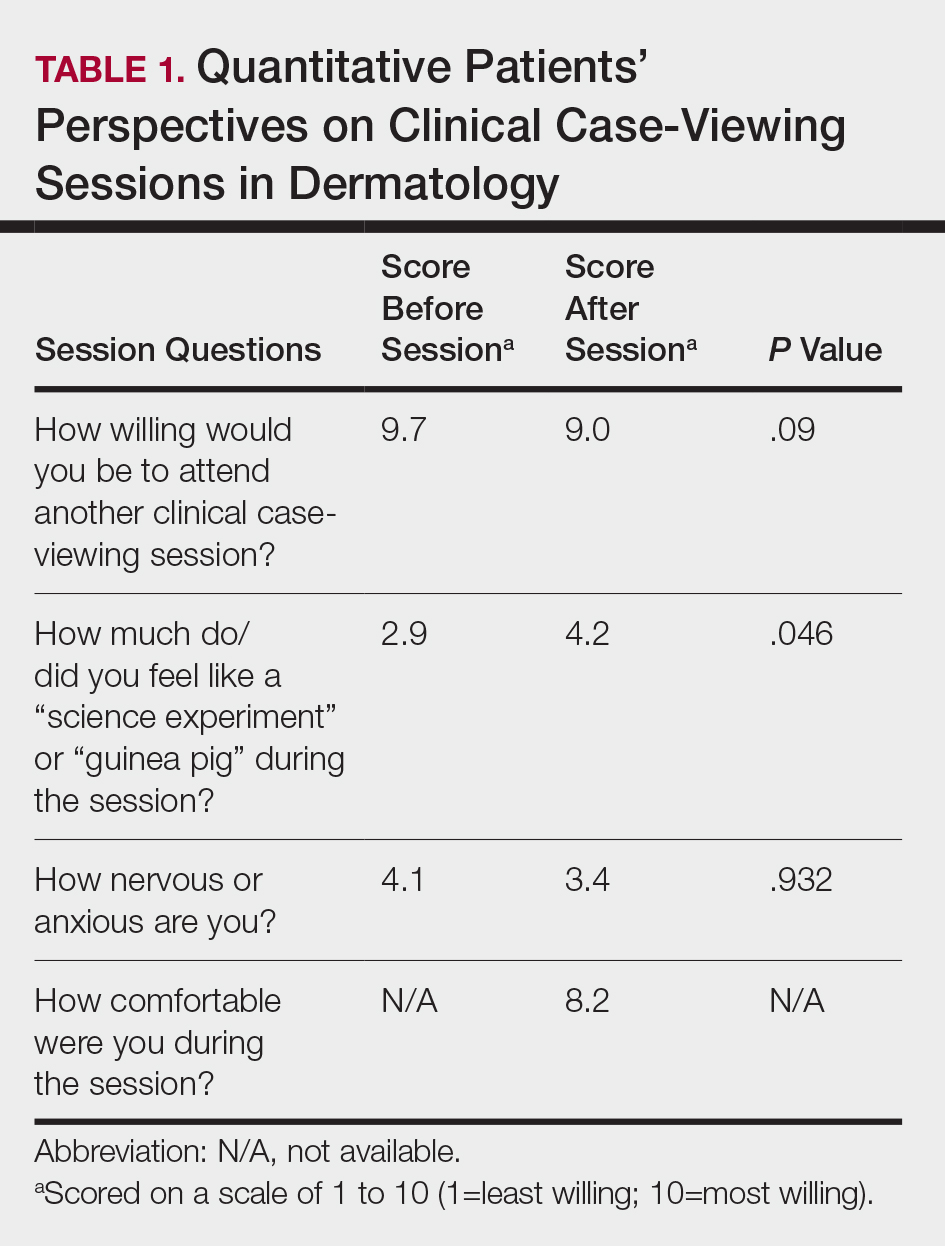

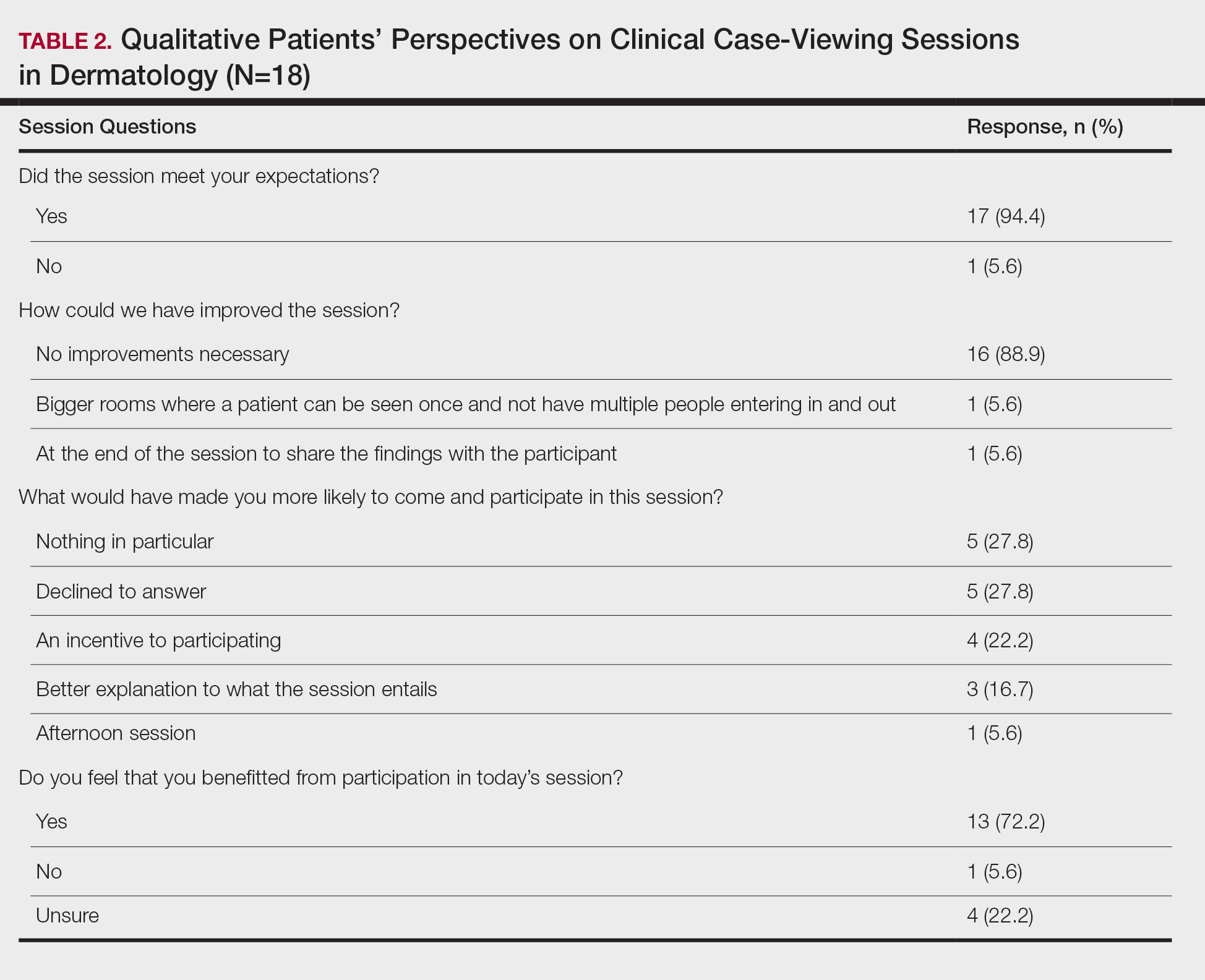

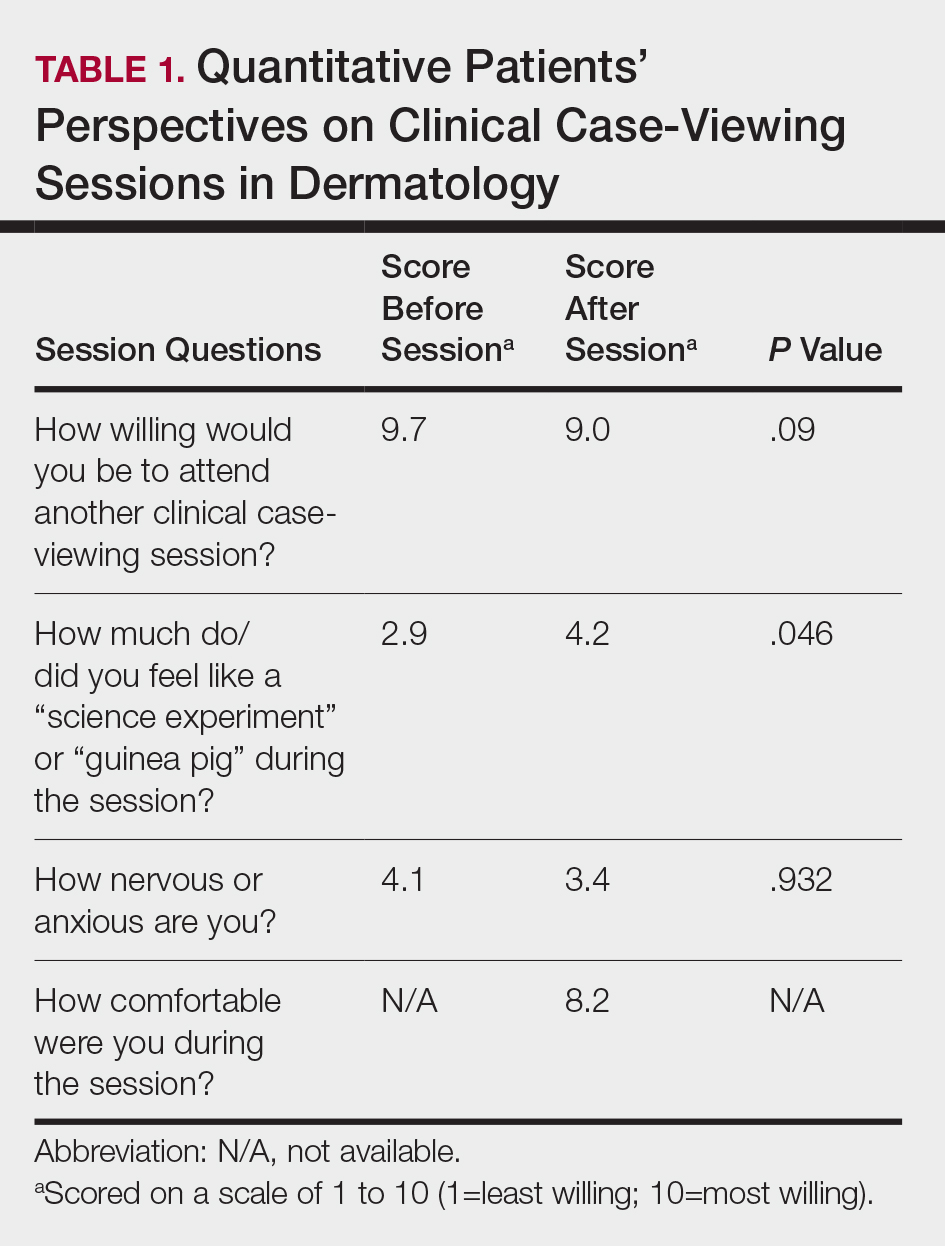

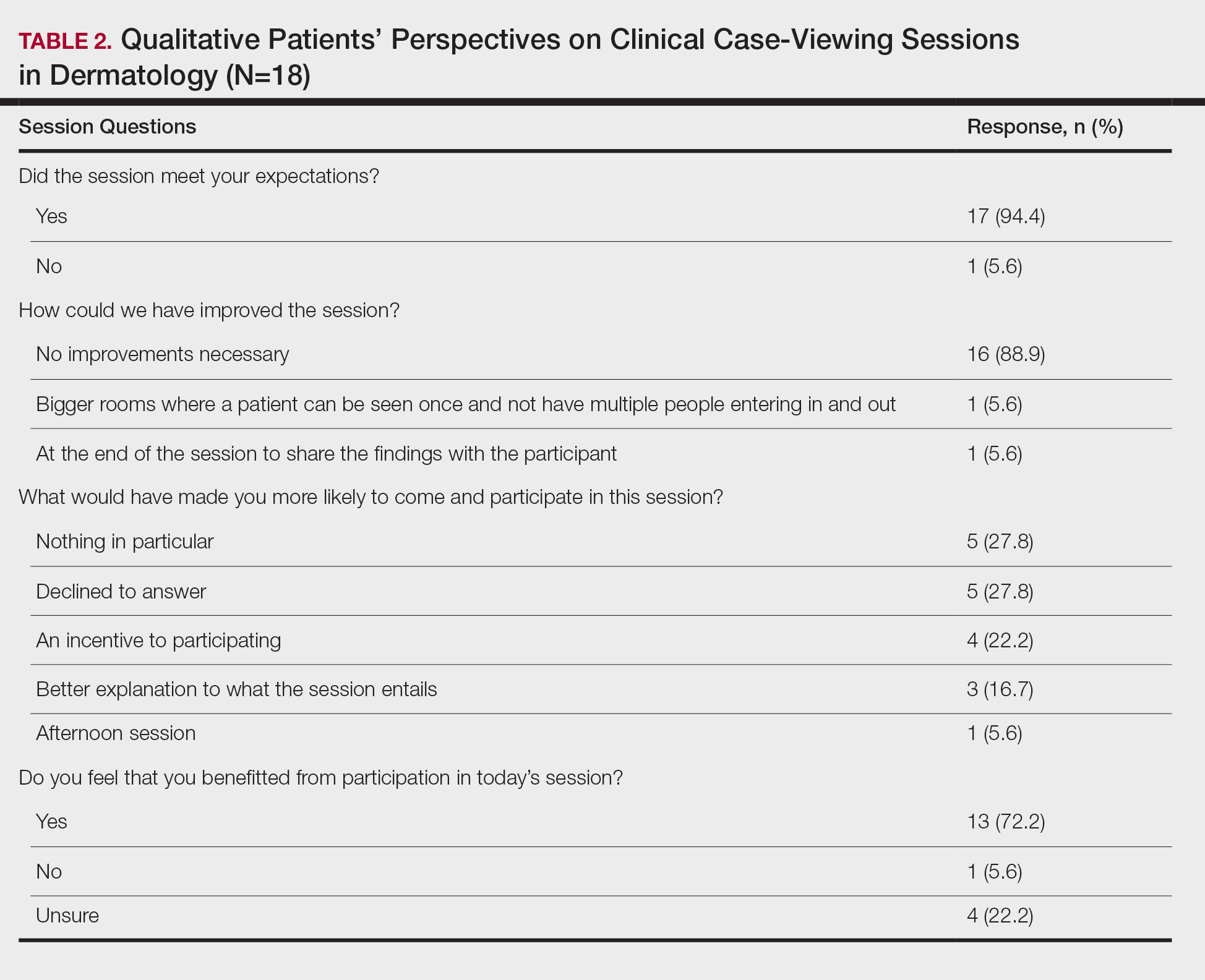

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

Practice Points

- Patient willingness to attend dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions is relatively unchanged before and after the session.

- Participants generally consider CCV sessions to be a positive experience.

A decade of telemedicine policy has advanced in just 2 weeks

The rapid spread of , which he’d never used.

But as soon as he learned that telehealth regulations had been relaxed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and that reimbursement had been broadened, Dr. Desai, a dermatologist in private practice and his staff began to mobilize.

“Kaboom! We made the decision to start doing it,” he said in an interview. “We drafted a consent form, uploaded it to our website, called patients, changed our voice greeting, and got clarity on insurance coverage. We’ve been flying by the seat of our pants.”

“I’m doing it because I don’t have a choice at this point,” said Dr. Desai, who is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors and its coronavirus task force. “I’m very worried about continuing to be able to meet our payroll expenses for staff and overhead to keep the office open.”

“Flying by the seat of our pants” to see patients virtually

Dermatologists have long been considered pioneers in telemedicine. They have, since the 1990s, capitalized on the visual nature of the specialty to diagnose and treat skin diseases by incorporating photos, videos, and virtual-patient visits. But the pandemic has forced the hands of even holdouts like Dr. Desai, who clung to in-person consults because of confusion related to HIPAA compliance issues and the sense that teledermatology “really dehumanizes patient interaction” for him.

In fact, as of 2017, only 15% of the nation’s 11,000 or so dermatologists had implemented telehealth into their practices, according to an AAD practice survey. In the wake of COVID-19, however, that percentage has likely more than tripled, experts estimate.

Now, dermatologists are assuming the mantle of educators for other specialists who never considered telehealth before in-person visits became fraught with concerns about the spread of the virus. And some are publishing guidelines for colleagues on how to prioritize teledermatology to stem transmission and conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and hospital beds.

User-friendly technology and the relaxed telehealth restrictions have made it fairly simple for patients and physicians to connect. Facetime and other once-prohibited platforms are all currently permissible, although physicians are encouraged to notify patients about potential privacy risks, according to an AAD teledermatology tool kit.

Teledermatology innovators

“We’ve moved 10 years in telemedicine policy in 2 weeks,” said Karen Edison, MD, of the University of Missouri, Columbia. “The federal government has really loosened the reins.”

At least half of all dermatologists in the United States have adopted telehealth since the pandemic emerged, she estimated. And most, like Dr. Desai, have done so in just the last several weeks.

“You can do about 90% of what you need to do as a dermatologist using the technology,” said Dr. Edison, who launched the first dermatology Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, or ECHO, program in the Midwest. That telehealth model was originally developed to connect rural general practitioners with specialists at academic medical centers or large health systems.

“People are used to taking pictures with their phones. In some ways, this crisis may change the face of our specialty,” she said in an interview.

“As we’re all practicing social distancing, I think physicians and patients are rethinking how we can access healthcare without pursuing traditional face-to-face interactions,” said Ivy Lee, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who is past chair of the AAD telemedicine task force and current chair of the teledermatology committee at the American Telemedicine Association. “Virtual health and telemedicine fit perfectly with that.”

Even before the pandemic, the innovative ways dermatologists were using telehealth were garnering increasing acclaim. All four clinical groups short-listed for dermatology team of the year at the BMJ Awards 2020 employed telehealth to improve patient services in the United Kingdom.

In the United States, dermatologists are joining forces to boost understanding of how telehealth can protect patients and clinicians from some of the ravages of the virus.

The Society of Dermatology Hospitalists has developed an algorithm – built on experiences its members have had caring for hospitalized patients with acute dermatologic conditions – to provide a “logical way” to triage telemedicine consults in multiple hospital settings during the coronavirus crisis, said President-Elect Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Telemedicine consultation is prioritized and patients at high risk for COVID-19 exposure are identified so that exposure time and resource use are limited and patient and staff safety are maximized.

“We want to empower our colleagues in community hospitals to play a role in safely providing care for patients in need but to be mindful about preserving resources,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who reported that the algorithm will be published imminently.

“If you don’t have to see a patient in person and can offer recommendations through telederm, you don’t need to put on a gown, gloves, mask, or goggles,” she said in an interview. “If you’re unable to assess photos, then of course you’ll use the appropriate protective wear, but it will be better if you can obtain the same result” without having to do so.

Sharing expertise

After the first week of tracking data to gauge the effectiveness of the algorithm at Massachusetts General, Dr. Kroshinsky said she is buoyed.

Of the 35 patients assessed electronically – all of whom would previously have been seen in person – only 4 ended up needing a subsequent in-person consult, she reported.

“It’s worked out great,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who noted that the pandemic is a “nice opportunity” to test different telehealth platforms and improve quality down the line. “We never had to use any excessive PPE, beyond what was routine, and the majority of patients were able to be staffed remotely. All patients had successful outcomes.”

With telehealth more firmly established in dermatology than in most other specialties, dermatologists are now helping clinicians in other fields who are rapidly ramping up their own telemedicine offerings.

These might include obstetrics and gynecology or “any medical specialty where they need to do checkups with their patients and don’t want them coming in for nonemergent visits,” said Carrie L. Kovarik, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

In addition to fielding many recent calls and emails from physicians seeking guidance on telehealth, Dr. Kovarik, Dr. Lee, and colleagues have published the steps required to integrate the technology into outpatient practices.

“Now that there’s a time for broad implementation, our colleagues are looking to us for help and troubleshooting advice,” said Dr. Kovarik, who is also a member of the AAD COVID-19 response task force.

Various specialties “lend themselves to telehealth, depending on how image- or data-dependent they are,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “But all specialists thinking of limiting or shutting down their practices are thinking about how they can provide continuity of care without exposing patients or staff to the risk of contracting the coronavirus.”

After-COVID goals

In his first week of virtual patient consults, Dr. Desai said he saw about 50 patients, which is still far fewer than the 160-180 he sees in person during a normal week.

“The problem is that patients don’t really want to do telehealth. You’d think it would be a good option,” he said, “but patients hesitate because they don’t really know how to use their device.” Some have instead rescheduled in-person appointments for months down the line.

Although telehealth has enabled Dr. Desai to readily assess patients with acne, hair loss, psoriasis, rashes, warts, and eczema, he’s concerned that necessary procedures, such as biopsies and dermoscopies, could be dangerously delayed. It’s also hard to assess the texture and thickness of certain skin lesions in photos or videos, he said.

“I’m trying to stay optimistic that this will get better and we’re able to move back to taking care of patients the way we need to,” he said.

Like Dr. Desai, other dermatologists who’ve implemented telemedicine during the pandemic have largely been swayed by the relaxed CMS regulations. “It’s made all the difference,” Dr. Kovarik said. “It has brought down the anxiety level and decreased questions about platforms and concentrated them on how to code the visits.”

And although it’s difficult to envision post-COVID medical practice in the thick of the pandemic, dermatologists expect the current strides in telemedicine will stick.

“I’m hoping that telehealth use isn’t dialed back all the way to baseline” after the pandemic eases, Dr. Kovarik said. “The cat’s out of the bag, and now that it is, hopefully it won’t be put back in.”

“If there’s a silver lining to this,” Dr. Kroshinsky said, “I hope it’s that we’ll be able to innovate around health care in a fashion we wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The rapid spread of , which he’d never used.

But as soon as he learned that telehealth regulations had been relaxed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and that reimbursement had been broadened, Dr. Desai, a dermatologist in private practice and his staff began to mobilize.

“Kaboom! We made the decision to start doing it,” he said in an interview. “We drafted a consent form, uploaded it to our website, called patients, changed our voice greeting, and got clarity on insurance coverage. We’ve been flying by the seat of our pants.”

“I’m doing it because I don’t have a choice at this point,” said Dr. Desai, who is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors and its coronavirus task force. “I’m very worried about continuing to be able to meet our payroll expenses for staff and overhead to keep the office open.”

“Flying by the seat of our pants” to see patients virtually

Dermatologists have long been considered pioneers in telemedicine. They have, since the 1990s, capitalized on the visual nature of the specialty to diagnose and treat skin diseases by incorporating photos, videos, and virtual-patient visits. But the pandemic has forced the hands of even holdouts like Dr. Desai, who clung to in-person consults because of confusion related to HIPAA compliance issues and the sense that teledermatology “really dehumanizes patient interaction” for him.

In fact, as of 2017, only 15% of the nation’s 11,000 or so dermatologists had implemented telehealth into their practices, according to an AAD practice survey. In the wake of COVID-19, however, that percentage has likely more than tripled, experts estimate.

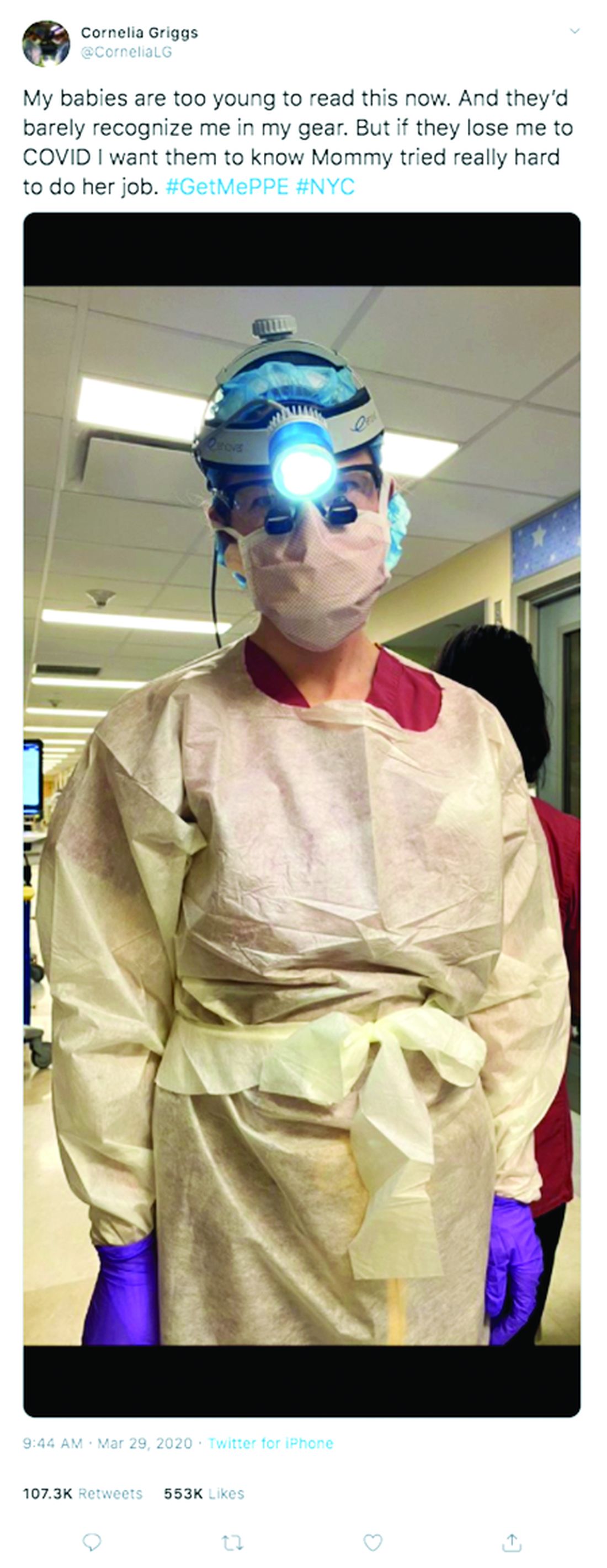

Now, dermatologists are assuming the mantle of educators for other specialists who never considered telehealth before in-person visits became fraught with concerns about the spread of the virus. And some are publishing guidelines for colleagues on how to prioritize teledermatology to stem transmission and conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and hospital beds.

User-friendly technology and the relaxed telehealth restrictions have made it fairly simple for patients and physicians to connect. Facetime and other once-prohibited platforms are all currently permissible, although physicians are encouraged to notify patients about potential privacy risks, according to an AAD teledermatology tool kit.

Teledermatology innovators

“We’ve moved 10 years in telemedicine policy in 2 weeks,” said Karen Edison, MD, of the University of Missouri, Columbia. “The federal government has really loosened the reins.”

At least half of all dermatologists in the United States have adopted telehealth since the pandemic emerged, she estimated. And most, like Dr. Desai, have done so in just the last several weeks.

“You can do about 90% of what you need to do as a dermatologist using the technology,” said Dr. Edison, who launched the first dermatology Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, or ECHO, program in the Midwest. That telehealth model was originally developed to connect rural general practitioners with specialists at academic medical centers or large health systems.

“People are used to taking pictures with their phones. In some ways, this crisis may change the face of our specialty,” she said in an interview.

“As we’re all practicing social distancing, I think physicians and patients are rethinking how we can access healthcare without pursuing traditional face-to-face interactions,” said Ivy Lee, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who is past chair of the AAD telemedicine task force and current chair of the teledermatology committee at the American Telemedicine Association. “Virtual health and telemedicine fit perfectly with that.”

Even before the pandemic, the innovative ways dermatologists were using telehealth were garnering increasing acclaim. All four clinical groups short-listed for dermatology team of the year at the BMJ Awards 2020 employed telehealth to improve patient services in the United Kingdom.

In the United States, dermatologists are joining forces to boost understanding of how telehealth can protect patients and clinicians from some of the ravages of the virus.

The Society of Dermatology Hospitalists has developed an algorithm – built on experiences its members have had caring for hospitalized patients with acute dermatologic conditions – to provide a “logical way” to triage telemedicine consults in multiple hospital settings during the coronavirus crisis, said President-Elect Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Telemedicine consultation is prioritized and patients at high risk for COVID-19 exposure are identified so that exposure time and resource use are limited and patient and staff safety are maximized.

“We want to empower our colleagues in community hospitals to play a role in safely providing care for patients in need but to be mindful about preserving resources,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who reported that the algorithm will be published imminently.

“If you don’t have to see a patient in person and can offer recommendations through telederm, you don’t need to put on a gown, gloves, mask, or goggles,” she said in an interview. “If you’re unable to assess photos, then of course you’ll use the appropriate protective wear, but it will be better if you can obtain the same result” without having to do so.

Sharing expertise

After the first week of tracking data to gauge the effectiveness of the algorithm at Massachusetts General, Dr. Kroshinsky said she is buoyed.

Of the 35 patients assessed electronically – all of whom would previously have been seen in person – only 4 ended up needing a subsequent in-person consult, she reported.

“It’s worked out great,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who noted that the pandemic is a “nice opportunity” to test different telehealth platforms and improve quality down the line. “We never had to use any excessive PPE, beyond what was routine, and the majority of patients were able to be staffed remotely. All patients had successful outcomes.”

With telehealth more firmly established in dermatology than in most other specialties, dermatologists are now helping clinicians in other fields who are rapidly ramping up their own telemedicine offerings.

These might include obstetrics and gynecology or “any medical specialty where they need to do checkups with their patients and don’t want them coming in for nonemergent visits,” said Carrie L. Kovarik, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

In addition to fielding many recent calls and emails from physicians seeking guidance on telehealth, Dr. Kovarik, Dr. Lee, and colleagues have published the steps required to integrate the technology into outpatient practices.

“Now that there’s a time for broad implementation, our colleagues are looking to us for help and troubleshooting advice,” said Dr. Kovarik, who is also a member of the AAD COVID-19 response task force.

Various specialties “lend themselves to telehealth, depending on how image- or data-dependent they are,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “But all specialists thinking of limiting or shutting down their practices are thinking about how they can provide continuity of care without exposing patients or staff to the risk of contracting the coronavirus.”

After-COVID goals

In his first week of virtual patient consults, Dr. Desai said he saw about 50 patients, which is still far fewer than the 160-180 he sees in person during a normal week.

“The problem is that patients don’t really want to do telehealth. You’d think it would be a good option,” he said, “but patients hesitate because they don’t really know how to use their device.” Some have instead rescheduled in-person appointments for months down the line.

Although telehealth has enabled Dr. Desai to readily assess patients with acne, hair loss, psoriasis, rashes, warts, and eczema, he’s concerned that necessary procedures, such as biopsies and dermoscopies, could be dangerously delayed. It’s also hard to assess the texture and thickness of certain skin lesions in photos or videos, he said.

“I’m trying to stay optimistic that this will get better and we’re able to move back to taking care of patients the way we need to,” he said.

Like Dr. Desai, other dermatologists who’ve implemented telemedicine during the pandemic have largely been swayed by the relaxed CMS regulations. “It’s made all the difference,” Dr. Kovarik said. “It has brought down the anxiety level and decreased questions about platforms and concentrated them on how to code the visits.”

And although it’s difficult to envision post-COVID medical practice in the thick of the pandemic, dermatologists expect the current strides in telemedicine will stick.

“I’m hoping that telehealth use isn’t dialed back all the way to baseline” after the pandemic eases, Dr. Kovarik said. “The cat’s out of the bag, and now that it is, hopefully it won’t be put back in.”

“If there’s a silver lining to this,” Dr. Kroshinsky said, “I hope it’s that we’ll be able to innovate around health care in a fashion we wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The rapid spread of , which he’d never used.

But as soon as he learned that telehealth regulations had been relaxed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and that reimbursement had been broadened, Dr. Desai, a dermatologist in private practice and his staff began to mobilize.

“Kaboom! We made the decision to start doing it,” he said in an interview. “We drafted a consent form, uploaded it to our website, called patients, changed our voice greeting, and got clarity on insurance coverage. We’ve been flying by the seat of our pants.”

“I’m doing it because I don’t have a choice at this point,” said Dr. Desai, who is a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors and its coronavirus task force. “I’m very worried about continuing to be able to meet our payroll expenses for staff and overhead to keep the office open.”

“Flying by the seat of our pants” to see patients virtually

Dermatologists have long been considered pioneers in telemedicine. They have, since the 1990s, capitalized on the visual nature of the specialty to diagnose and treat skin diseases by incorporating photos, videos, and virtual-patient visits. But the pandemic has forced the hands of even holdouts like Dr. Desai, who clung to in-person consults because of confusion related to HIPAA compliance issues and the sense that teledermatology “really dehumanizes patient interaction” for him.

In fact, as of 2017, only 15% of the nation’s 11,000 or so dermatologists had implemented telehealth into their practices, according to an AAD practice survey. In the wake of COVID-19, however, that percentage has likely more than tripled, experts estimate.

Now, dermatologists are assuming the mantle of educators for other specialists who never considered telehealth before in-person visits became fraught with concerns about the spread of the virus. And some are publishing guidelines for colleagues on how to prioritize teledermatology to stem transmission and conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and hospital beds.

User-friendly technology and the relaxed telehealth restrictions have made it fairly simple for patients and physicians to connect. Facetime and other once-prohibited platforms are all currently permissible, although physicians are encouraged to notify patients about potential privacy risks, according to an AAD teledermatology tool kit.

Teledermatology innovators

“We’ve moved 10 years in telemedicine policy in 2 weeks,” said Karen Edison, MD, of the University of Missouri, Columbia. “The federal government has really loosened the reins.”

At least half of all dermatologists in the United States have adopted telehealth since the pandemic emerged, she estimated. And most, like Dr. Desai, have done so in just the last several weeks.

“You can do about 90% of what you need to do as a dermatologist using the technology,” said Dr. Edison, who launched the first dermatology Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, or ECHO, program in the Midwest. That telehealth model was originally developed to connect rural general practitioners with specialists at academic medical centers or large health systems.

“People are used to taking pictures with their phones. In some ways, this crisis may change the face of our specialty,” she said in an interview.

“As we’re all practicing social distancing, I think physicians and patients are rethinking how we can access healthcare without pursuing traditional face-to-face interactions,” said Ivy Lee, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who is past chair of the AAD telemedicine task force and current chair of the teledermatology committee at the American Telemedicine Association. “Virtual health and telemedicine fit perfectly with that.”

Even before the pandemic, the innovative ways dermatologists were using telehealth were garnering increasing acclaim. All four clinical groups short-listed for dermatology team of the year at the BMJ Awards 2020 employed telehealth to improve patient services in the United Kingdom.

In the United States, dermatologists are joining forces to boost understanding of how telehealth can protect patients and clinicians from some of the ravages of the virus.

The Society of Dermatology Hospitalists has developed an algorithm – built on experiences its members have had caring for hospitalized patients with acute dermatologic conditions – to provide a “logical way” to triage telemedicine consults in multiple hospital settings during the coronavirus crisis, said President-Elect Daniela Kroshinsky, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Telemedicine consultation is prioritized and patients at high risk for COVID-19 exposure are identified so that exposure time and resource use are limited and patient and staff safety are maximized.

“We want to empower our colleagues in community hospitals to play a role in safely providing care for patients in need but to be mindful about preserving resources,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who reported that the algorithm will be published imminently.

“If you don’t have to see a patient in person and can offer recommendations through telederm, you don’t need to put on a gown, gloves, mask, or goggles,” she said in an interview. “If you’re unable to assess photos, then of course you’ll use the appropriate protective wear, but it will be better if you can obtain the same result” without having to do so.

Sharing expertise

After the first week of tracking data to gauge the effectiveness of the algorithm at Massachusetts General, Dr. Kroshinsky said she is buoyed.

Of the 35 patients assessed electronically – all of whom would previously have been seen in person – only 4 ended up needing a subsequent in-person consult, she reported.

“It’s worked out great,” said Dr. Kroshinsky, who noted that the pandemic is a “nice opportunity” to test different telehealth platforms and improve quality down the line. “We never had to use any excessive PPE, beyond what was routine, and the majority of patients were able to be staffed remotely. All patients had successful outcomes.”

With telehealth more firmly established in dermatology than in most other specialties, dermatologists are now helping clinicians in other fields who are rapidly ramping up their own telemedicine offerings.

These might include obstetrics and gynecology or “any medical specialty where they need to do checkups with their patients and don’t want them coming in for nonemergent visits,” said Carrie L. Kovarik, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

In addition to fielding many recent calls and emails from physicians seeking guidance on telehealth, Dr. Kovarik, Dr. Lee, and colleagues have published the steps required to integrate the technology into outpatient practices.

“Now that there’s a time for broad implementation, our colleagues are looking to us for help and troubleshooting advice,” said Dr. Kovarik, who is also a member of the AAD COVID-19 response task force.

Various specialties “lend themselves to telehealth, depending on how image- or data-dependent they are,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “But all specialists thinking of limiting or shutting down their practices are thinking about how they can provide continuity of care without exposing patients or staff to the risk of contracting the coronavirus.”

After-COVID goals

In his first week of virtual patient consults, Dr. Desai said he saw about 50 patients, which is still far fewer than the 160-180 he sees in person during a normal week.

“The problem is that patients don’t really want to do telehealth. You’d think it would be a good option,” he said, “but patients hesitate because they don’t really know how to use their device.” Some have instead rescheduled in-person appointments for months down the line.

Although telehealth has enabled Dr. Desai to readily assess patients with acne, hair loss, psoriasis, rashes, warts, and eczema, he’s concerned that necessary procedures, such as biopsies and dermoscopies, could be dangerously delayed. It’s also hard to assess the texture and thickness of certain skin lesions in photos or videos, he said.

“I’m trying to stay optimistic that this will get better and we’re able to move back to taking care of patients the way we need to,” he said.

Like Dr. Desai, other dermatologists who’ve implemented telemedicine during the pandemic have largely been swayed by the relaxed CMS regulations. “It’s made all the difference,” Dr. Kovarik said. “It has brought down the anxiety level and decreased questions about platforms and concentrated them on how to code the visits.”

And although it’s difficult to envision post-COVID medical practice in the thick of the pandemic, dermatologists expect the current strides in telemedicine will stick.

“I’m hoping that telehealth use isn’t dialed back all the way to baseline” after the pandemic eases, Dr. Kovarik said. “The cat’s out of the bag, and now that it is, hopefully it won’t be put back in.”

“If there’s a silver lining to this,” Dr. Kroshinsky said, “I hope it’s that we’ll be able to innovate around health care in a fashion we wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Brutal’ plan to restrict palliative radiation during pandemic

A major comprehensive cancer center at the epicenter of the New York City COVID-19 storm is preparing to scale back palliative radiation therapy (RT), anticipating a focus on only oncologic emergencies.

“We’re not there yet, but we’re anticipating when the time comes in the next few weeks that we will have a system in place so we are able to handle it,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

Yang and an expert panel of colleagues reviewed high-impact evidence, prior systematic reviews, and national guidelines to compile a set of recommendations for triage and shortened palliative rRT at their center, should the need arise.

The recommendations on palliative radiotherapy for oncologic emergencies in the setting of COVID-19 appear in a preprint version in Advances in Radiation Oncology, released by the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

Yang says the recommendations are a careful balance between the risk of COVID-19 exposure of staff and patients with the potential morbidity of delaying treatment.

“Everyone is conscious of decisions about whether patients need treatment now or can wait,” he told Medscape Medical News. “It’s a juggling act every single day, but by having this guideline in place, when we face the situation where we do have to make decisions, is helpful.”

The document aims to enable swift decisions based on best practice, including a three-tiered system prioritizing only “clinically urgent cases, in which delaying treatment would result in compromised outcomes or serious morbidity.”

“It’s brutal, that’s the only word for it. Not that I disagree with it,” commented Padraig Warde, MB BCh, professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Toronto, and radiation oncologist, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Like many places, Toronto is not yet experiencing the COVID-19 burden of New York City, but Warde says the MSKCC guideline is useful for everyone. “Other centers should review it and see how they could deal with resource limitations,” he said. “It’s sobering and sad, but if you don’t have the staff to treat all patients, which particular patients do you choose to treat?”

In a nutshell, the MSKCC recommendations defines Tier 1 patients as having oncologic emergencies that require palliative RT, including “cord compression, symptomatic brain metastases requiring whole-brain radiotherapy, life-threatening tumor bleeding, and malignant airway obstruction.”

According to the decision-making guideline, patients in Tiers 2 and 3 would have their palliative RT delayed. This would include Tier 2 patients whose needs are not classified as emergencies, but who have either symptomatic disease for which RT is usually the standard of care or asymptomatic disease for which RT is recommended “to prevent imminent functional deficits.” Tier 3 would be symptomatic or asymptomatic patients for whom RT is “one of the effective treatment options.”

“Rationing is always very difficult because as physicians you always want to do everything you can for your patients but we really have to strike the balance on when to do what, said Yang. The plan that he authored anticipates both reduced availability of radiation therapists as well as aggressive attempts to limit patients’ infection exposure.

“If a patient’s radiation is being considered for delay due to COVID-19, other means are utilized to achieve the goal of palliation in the interim, and in addition to the tier system, this decision is also made on a case-by-case basis with departmental discussion on the risks and benefits,” he explained.

“There are layers of checks and balances for these decisions...Obviously for oncologic emergencies, radiation will be implemented. However for less urgent situations, bringing them into the hospital when there are other ways to achieve the same goal, potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 is higher than the benefit we would be able to provide.”

The document also recommends shorter courses of RT when radiation is deemed appropriate.

“We have good evidence showing shorter courses of radiation can effectively treat the goal of palliation compared to longer courses of radiation,” he explained. “Going through this pandemic actually forces radiation oncologists in the United States to put that evidence into practice. It’s not suboptimal care in the sense that we are achieving the same goal — palliation. This paper is to remind people there are equally effective courses of palliation we can be using.”

“[There’s] nothing like a crisis to get people to do the right thing,” commented Louis Potters, MD, professor and chair of radiation medicine at the Feinstein Institutes, the research arm of Northwell Health, New York’s largest healthcare provider.

Northwell Health has been at the epicenter of the New York outbreak of COVID-19. Potters writes on an ASTRO blog that, as of March 26, Northwell Health “has diagnosed 4399 positive COVID-19 patients, which is about 20% of New York state and 1.2% of all cases in the world. All cancer surgery was discontinued as of March 20 and all of our 23 hospitals are seeing COVID-19 admissions, and ICU care became the primary focus of the entire system. As of today, we have reserved one floor in two hospitals for non-COVID care such as trauma. That’s it.”

Before the crisis, radiation medicine at Northwell consisted of eight separate locations treating on average 280 EBRT cases a day, not including SBRT/SRS and brachytherapy cases. “That of course was 3 weeks ago,” he notes.

Commenting on the recommendations from the MSKCC group, Potters told Medscape Medical News that the primary goal “was to document what are acceptable alternatives for accelerated care.”

“Ironically, these guidelines represent best practices with evidence that — in a non–COVID-19 world — make sense for the majority of patients requiring palliative radiotherapy,” he said.

Potters said there has been hesitance to transition to shorter radiation treatments for several reasons.

“Historically, palliative radiotherapy has been delivered over 2 to 4 weeks with good results. And, as is typical in medicine, the transition to shorter course care is slowed by financial incentives to protract care,” he explained.

“In a value-based future where payment is based on outcomes, this transition to shorter care will evolve very quickly. But given the current COVID-19 crisis, and the risk to patients and staff, the incentive for shorter treatment courses has been thrust upon us and the MSKCC outline helps to define how to do this safely and with evidence-based expected efficacy.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A major comprehensive cancer center at the epicenter of the New York City COVID-19 storm is preparing to scale back palliative radiation therapy (RT), anticipating a focus on only oncologic emergencies.

“We’re not there yet, but we’re anticipating when the time comes in the next few weeks that we will have a system in place so we are able to handle it,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

Yang and an expert panel of colleagues reviewed high-impact evidence, prior systematic reviews, and national guidelines to compile a set of recommendations for triage and shortened palliative rRT at their center, should the need arise.

The recommendations on palliative radiotherapy for oncologic emergencies in the setting of COVID-19 appear in a preprint version in Advances in Radiation Oncology, released by the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

Yang says the recommendations are a careful balance between the risk of COVID-19 exposure of staff and patients with the potential morbidity of delaying treatment.

“Everyone is conscious of decisions about whether patients need treatment now or can wait,” he told Medscape Medical News. “It’s a juggling act every single day, but by having this guideline in place, when we face the situation where we do have to make decisions, is helpful.”

The document aims to enable swift decisions based on best practice, including a three-tiered system prioritizing only “clinically urgent cases, in which delaying treatment would result in compromised outcomes or serious morbidity.”

“It’s brutal, that’s the only word for it. Not that I disagree with it,” commented Padraig Warde, MB BCh, professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Toronto, and radiation oncologist, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Like many places, Toronto is not yet experiencing the COVID-19 burden of New York City, but Warde says the MSKCC guideline is useful for everyone. “Other centers should review it and see how they could deal with resource limitations,” he said. “It’s sobering and sad, but if you don’t have the staff to treat all patients, which particular patients do you choose to treat?”

In a nutshell, the MSKCC recommendations defines Tier 1 patients as having oncologic emergencies that require palliative RT, including “cord compression, symptomatic brain metastases requiring whole-brain radiotherapy, life-threatening tumor bleeding, and malignant airway obstruction.”

According to the decision-making guideline, patients in Tiers 2 and 3 would have their palliative RT delayed. This would include Tier 2 patients whose needs are not classified as emergencies, but who have either symptomatic disease for which RT is usually the standard of care or asymptomatic disease for which RT is recommended “to prevent imminent functional deficits.” Tier 3 would be symptomatic or asymptomatic patients for whom RT is “one of the effective treatment options.”

“Rationing is always very difficult because as physicians you always want to do everything you can for your patients but we really have to strike the balance on when to do what, said Yang. The plan that he authored anticipates both reduced availability of radiation therapists as well as aggressive attempts to limit patients’ infection exposure.

“If a patient’s radiation is being considered for delay due to COVID-19, other means are utilized to achieve the goal of palliation in the interim, and in addition to the tier system, this decision is also made on a case-by-case basis with departmental discussion on the risks and benefits,” he explained.

“There are layers of checks and balances for these decisions...Obviously for oncologic emergencies, radiation will be implemented. However for less urgent situations, bringing them into the hospital when there are other ways to achieve the same goal, potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 is higher than the benefit we would be able to provide.”

The document also recommends shorter courses of RT when radiation is deemed appropriate.

“We have good evidence showing shorter courses of radiation can effectively treat the goal of palliation compared to longer courses of radiation,” he explained. “Going through this pandemic actually forces radiation oncologists in the United States to put that evidence into practice. It’s not suboptimal care in the sense that we are achieving the same goal — palliation. This paper is to remind people there are equally effective courses of palliation we can be using.”

“[There’s] nothing like a crisis to get people to do the right thing,” commented Louis Potters, MD, professor and chair of radiation medicine at the Feinstein Institutes, the research arm of Northwell Health, New York’s largest healthcare provider.

Northwell Health has been at the epicenter of the New York outbreak of COVID-19. Potters writes on an ASTRO blog that, as of March 26, Northwell Health “has diagnosed 4399 positive COVID-19 patients, which is about 20% of New York state and 1.2% of all cases in the world. All cancer surgery was discontinued as of March 20 and all of our 23 hospitals are seeing COVID-19 admissions, and ICU care became the primary focus of the entire system. As of today, we have reserved one floor in two hospitals for non-COVID care such as trauma. That’s it.”

Before the crisis, radiation medicine at Northwell consisted of eight separate locations treating on average 280 EBRT cases a day, not including SBRT/SRS and brachytherapy cases. “That of course was 3 weeks ago,” he notes.

Commenting on the recommendations from the MSKCC group, Potters told Medscape Medical News that the primary goal “was to document what are acceptable alternatives for accelerated care.”

“Ironically, these guidelines represent best practices with evidence that — in a non–COVID-19 world — make sense for the majority of patients requiring palliative radiotherapy,” he said.

Potters said there has been hesitance to transition to shorter radiation treatments for several reasons.

“Historically, palliative radiotherapy has been delivered over 2 to 4 weeks with good results. And, as is typical in medicine, the transition to shorter course care is slowed by financial incentives to protract care,” he explained.

“In a value-based future where payment is based on outcomes, this transition to shorter care will evolve very quickly. But given the current COVID-19 crisis, and the risk to patients and staff, the incentive for shorter treatment courses has been thrust upon us and the MSKCC outline helps to define how to do this safely and with evidence-based expected efficacy.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A major comprehensive cancer center at the epicenter of the New York City COVID-19 storm is preparing to scale back palliative radiation therapy (RT), anticipating a focus on only oncologic emergencies.

“We’re not there yet, but we’re anticipating when the time comes in the next few weeks that we will have a system in place so we are able to handle it,” Jonathan Yang, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

Yang and an expert panel of colleagues reviewed high-impact evidence, prior systematic reviews, and national guidelines to compile a set of recommendations for triage and shortened palliative rRT at their center, should the need arise.

The recommendations on palliative radiotherapy for oncologic emergencies in the setting of COVID-19 appear in a preprint version in Advances in Radiation Oncology, released by the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

Yang says the recommendations are a careful balance between the risk of COVID-19 exposure of staff and patients with the potential morbidity of delaying treatment.

“Everyone is conscious of decisions about whether patients need treatment now or can wait,” he told Medscape Medical News. “It’s a juggling act every single day, but by having this guideline in place, when we face the situation where we do have to make decisions, is helpful.”

The document aims to enable swift decisions based on best practice, including a three-tiered system prioritizing only “clinically urgent cases, in which delaying treatment would result in compromised outcomes or serious morbidity.”

“It’s brutal, that’s the only word for it. Not that I disagree with it,” commented Padraig Warde, MB BCh, professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Toronto, and radiation oncologist, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Like many places, Toronto is not yet experiencing the COVID-19 burden of New York City, but Warde says the MSKCC guideline is useful for everyone. “Other centers should review it and see how they could deal with resource limitations,” he said. “It’s sobering and sad, but if you don’t have the staff to treat all patients, which particular patients do you choose to treat?”

In a nutshell, the MSKCC recommendations defines Tier 1 patients as having oncologic emergencies that require palliative RT, including “cord compression, symptomatic brain metastases requiring whole-brain radiotherapy, life-threatening tumor bleeding, and malignant airway obstruction.”

According to the decision-making guideline, patients in Tiers 2 and 3 would have their palliative RT delayed. This would include Tier 2 patients whose needs are not classified as emergencies, but who have either symptomatic disease for which RT is usually the standard of care or asymptomatic disease for which RT is recommended “to prevent imminent functional deficits.” Tier 3 would be symptomatic or asymptomatic patients for whom RT is “one of the effective treatment options.”

“Rationing is always very difficult because as physicians you always want to do everything you can for your patients but we really have to strike the balance on when to do what, said Yang. The plan that he authored anticipates both reduced availability of radiation therapists as well as aggressive attempts to limit patients’ infection exposure.

“If a patient’s radiation is being considered for delay due to COVID-19, other means are utilized to achieve the goal of palliation in the interim, and in addition to the tier system, this decision is also made on a case-by-case basis with departmental discussion on the risks and benefits,” he explained.

“There are layers of checks and balances for these decisions...Obviously for oncologic emergencies, radiation will be implemented. However for less urgent situations, bringing them into the hospital when there are other ways to achieve the same goal, potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 is higher than the benefit we would be able to provide.”

The document also recommends shorter courses of RT when radiation is deemed appropriate.

“We have good evidence showing shorter courses of radiation can effectively treat the goal of palliation compared to longer courses of radiation,” he explained. “Going through this pandemic actually forces radiation oncologists in the United States to put that evidence into practice. It’s not suboptimal care in the sense that we are achieving the same goal — palliation. This paper is to remind people there are equally effective courses of palliation we can be using.”

“[There’s] nothing like a crisis to get people to do the right thing,” commented Louis Potters, MD, professor and chair of radiation medicine at the Feinstein Institutes, the research arm of Northwell Health, New York’s largest healthcare provider.

Northwell Health has been at the epicenter of the New York outbreak of COVID-19. Potters writes on an ASTRO blog that, as of March 26, Northwell Health “has diagnosed 4399 positive COVID-19 patients, which is about 20% of New York state and 1.2% of all cases in the world. All cancer surgery was discontinued as of March 20 and all of our 23 hospitals are seeing COVID-19 admissions, and ICU care became the primary focus of the entire system. As of today, we have reserved one floor in two hospitals for non-COVID care such as trauma. That’s it.”

Before the crisis, radiation medicine at Northwell consisted of eight separate locations treating on average 280 EBRT cases a day, not including SBRT/SRS and brachytherapy cases. “That of course was 3 weeks ago,” he notes.

Commenting on the recommendations from the MSKCC group, Potters told Medscape Medical News that the primary goal “was to document what are acceptable alternatives for accelerated care.”

“Ironically, these guidelines represent best practices with evidence that — in a non–COVID-19 world — make sense for the majority of patients requiring palliative radiotherapy,” he said.

Potters said there has been hesitance to transition to shorter radiation treatments for several reasons.

“Historically, palliative radiotherapy has been delivered over 2 to 4 weeks with good results. And, as is typical in medicine, the transition to shorter course care is slowed by financial incentives to protract care,” he explained.

“In a value-based future where payment is based on outcomes, this transition to shorter care will evolve very quickly. But given the current COVID-19 crisis, and the risk to patients and staff, the incentive for shorter treatment courses has been thrust upon us and the MSKCC outline helps to define how to do this safely and with evidence-based expected efficacy.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advice from the front lines: How cancer centers can cope with COVID-19

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

No staff COVID-19 diagnoses after plan at Chinese cancer center

Short-term results

No staff members or patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 after “strict protective measures” for screening and managing patients were implemented at the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing, according to a report published online April 1 in JAMA Oncology.

However, the time period for the analysis, which included nearly 3000 patients, was short — only about 3 weeks (February 12 to March 3). Also, Beijing is more than 1100 kilometers from Wuhan, the center of the Chinese outbreak of COVID-19.

The Beijing cancer hospital implemented a multipronged safety plan in February in order to “avoid COVID-19 related nosocomial cross-infection between patients and medical staff,” explain the authors, led by medical oncologist Zhijie Wang, MD.

Notably, “all of the measures taken in China are actively being implemented and used in major oncology centers in the United States,” Robert Carlson, MD, chief executive officer, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), told Medscape Medical News.

John Greene, MD, section chief, Infectious Disease and Tropical Medicine, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, pointed out that the Chinese safety plan, which is full of “good measures,” is being largely used at his center. However, he observed that one tool — doing a temperature check at the hospital front door — is not well supported by most of the literature. “It gives good optics and looks like you are doing the most you possibly can, but scientifically it may not be as effective [as other screening measures],” he said.

The Chinese plan consists of four broad elements

First, the above-mentioned on-site temperature tests are performed at the entrances of the hospital, outpatient clinic, and wards. Contact and travel histories related to the Wuhan epidemic area are also established and recorded.