User login

Many physicians live within their means and save, survey shows

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, half are under the million dollars and about half believe in living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Along with that somewhat prudent lifestyle comes savings, with

Those habits may help some navigate the financial upheaval in medicine brought about by COVID-19.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.

The authors of the report note that by some estimates, primary care offices have seen a 55% drop in revenue because of the pandemic, and specialists have been hard hit with the suspension of most elective procedures.

Primary care offices are seeing fewer patients and are limiting hours, and some offices have been forced to close. Others have stemmed the losses by introducing telemedicine options.

Before COVID-19, average incomes had continued to rise – this year to $243,000 (a 2.5% boost from last year’s $237,000) for primary care physicians and $346,000 for specialists (a 1.5% rise from last year’s $341,000).

About half of physicians (42%) reported a net worth of $1 million to $5 million, and 8% reported a net worth of more than $5 million. Fifty percent of physicians had a net worth of less than $1 million.

Those figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%).

Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000.

Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

43% live below their means

Asked about habits regarding saving, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Half said they live at their means, and 7% said they live above their means.

Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., recommends in the report trying to save 20% of annual gross salary.

More than a third of physicians who responded (39%) said they put more than $2,000/month into tax-deferred retirement or college savings, but Dr. Greenwald acknowledged that this may become more challenging.

“Many have seen the employer match in their retirement plans reduced or eliminated through the end of 2020, with what comes in 2021 as yet undefined,” he said.

A smaller percentage (26%) answered that they put more than $2,000 a month into a taxable retirement or college savings account each month.

Home size by specialty

Mortgages on a primary residence were the top reasons for debt (63%), followed by car loans (37%), personal education loans (26%), and credit card balances (25%).

Half of specialists and 61% of primary care physicians live in homes with up to 3,000 square feet. Only 7% of PCPs and 12% of specialists live in homes with 5000 square feet or more.

At 22%, plastic surgeons and orthopedists were the most likely groups to have houses with the largest square footage, according to the survey.

About one in four physicians in five specialties (urology, cardiology, plastic surgery, otolaryngology, and critical care) reported that they had mortgages of more than $500,000.

Standard financial advice, the report authors note, is that a mortgage should take up no more than 28% of monthly gross income.

Another large source of debt came from student loans. Close to 80% of graduating medical students have educational debt. The average balance for graduating students in 2018 was $196,520, the report authors state.

Those in physical medicine/rehabilitation and family medicine were most likely to still be paying off student debt (34% said they were). Conversely, half as many nephrologists and rheumatologists (15%) and gastroenterologists (14%) reported that they were paying off educational debt.

Only 11% of physicians said they were currently free of any debt.

Most physicians in the survey (72%) reported that they had not experienced a significant financial loss in the past year.

For those who did experience such a loss, the top reason given was related to a bad investment or the stock market (9%).

Cost-cutting strategies

Revenue reduction will likely lead to spending less this year as the pandemic challenges continue.

Survey respondents offered their most effective cost-cutting strategies.

A hospitalist said, “Half of every bonus goes into the investment account, no matter how much.”

“We add an extra amount to the principal of our monthly mortgage payment,” an internist said.

A pediatrician offered, “I bring my lunch to work every day and don’t eat in restaurants often.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, half are under the million dollars and about half believe in living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Along with that somewhat prudent lifestyle comes savings, with

Those habits may help some navigate the financial upheaval in medicine brought about by COVID-19.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.

The authors of the report note that by some estimates, primary care offices have seen a 55% drop in revenue because of the pandemic, and specialists have been hard hit with the suspension of most elective procedures.

Primary care offices are seeing fewer patients and are limiting hours, and some offices have been forced to close. Others have stemmed the losses by introducing telemedicine options.

Before COVID-19, average incomes had continued to rise – this year to $243,000 (a 2.5% boost from last year’s $237,000) for primary care physicians and $346,000 for specialists (a 1.5% rise from last year’s $341,000).

About half of physicians (42%) reported a net worth of $1 million to $5 million, and 8% reported a net worth of more than $5 million. Fifty percent of physicians had a net worth of less than $1 million.

Those figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%).

Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000.

Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

43% live below their means

Asked about habits regarding saving, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Half said they live at their means, and 7% said they live above their means.

Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., recommends in the report trying to save 20% of annual gross salary.

More than a third of physicians who responded (39%) said they put more than $2,000/month into tax-deferred retirement or college savings, but Dr. Greenwald acknowledged that this may become more challenging.

“Many have seen the employer match in their retirement plans reduced or eliminated through the end of 2020, with what comes in 2021 as yet undefined,” he said.

A smaller percentage (26%) answered that they put more than $2,000 a month into a taxable retirement or college savings account each month.

Home size by specialty

Mortgages on a primary residence were the top reasons for debt (63%), followed by car loans (37%), personal education loans (26%), and credit card balances (25%).

Half of specialists and 61% of primary care physicians live in homes with up to 3,000 square feet. Only 7% of PCPs and 12% of specialists live in homes with 5000 square feet or more.

At 22%, plastic surgeons and orthopedists were the most likely groups to have houses with the largest square footage, according to the survey.

About one in four physicians in five specialties (urology, cardiology, plastic surgery, otolaryngology, and critical care) reported that they had mortgages of more than $500,000.

Standard financial advice, the report authors note, is that a mortgage should take up no more than 28% of monthly gross income.

Another large source of debt came from student loans. Close to 80% of graduating medical students have educational debt. The average balance for graduating students in 2018 was $196,520, the report authors state.

Those in physical medicine/rehabilitation and family medicine were most likely to still be paying off student debt (34% said they were). Conversely, half as many nephrologists and rheumatologists (15%) and gastroenterologists (14%) reported that they were paying off educational debt.

Only 11% of physicians said they were currently free of any debt.

Most physicians in the survey (72%) reported that they had not experienced a significant financial loss in the past year.

For those who did experience such a loss, the top reason given was related to a bad investment or the stock market (9%).

Cost-cutting strategies

Revenue reduction will likely lead to spending less this year as the pandemic challenges continue.

Survey respondents offered their most effective cost-cutting strategies.

A hospitalist said, “Half of every bonus goes into the investment account, no matter how much.”

“We add an extra amount to the principal of our monthly mortgage payment,” an internist said.

A pediatrician offered, “I bring my lunch to work every day and don’t eat in restaurants often.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, half are under the million dollars and about half believe in living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Along with that somewhat prudent lifestyle comes savings, with

Those habits may help some navigate the financial upheaval in medicine brought about by COVID-19.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic.

The authors of the report note that by some estimates, primary care offices have seen a 55% drop in revenue because of the pandemic, and specialists have been hard hit with the suspension of most elective procedures.

Primary care offices are seeing fewer patients and are limiting hours, and some offices have been forced to close. Others have stemmed the losses by introducing telemedicine options.

Before COVID-19, average incomes had continued to rise – this year to $243,000 (a 2.5% boost from last year’s $237,000) for primary care physicians and $346,000 for specialists (a 1.5% rise from last year’s $341,000).

About half of physicians (42%) reported a net worth of $1 million to $5 million, and 8% reported a net worth of more than $5 million. Fifty percent of physicians had a net worth of less than $1 million.

Those figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%).

Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000.

Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

43% live below their means

Asked about habits regarding saving, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Half said they live at their means, and 7% said they live above their means.

Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., recommends in the report trying to save 20% of annual gross salary.

More than a third of physicians who responded (39%) said they put more than $2,000/month into tax-deferred retirement or college savings, but Dr. Greenwald acknowledged that this may become more challenging.

“Many have seen the employer match in their retirement plans reduced or eliminated through the end of 2020, with what comes in 2021 as yet undefined,” he said.

A smaller percentage (26%) answered that they put more than $2,000 a month into a taxable retirement or college savings account each month.

Home size by specialty

Mortgages on a primary residence were the top reasons for debt (63%), followed by car loans (37%), personal education loans (26%), and credit card balances (25%).

Half of specialists and 61% of primary care physicians live in homes with up to 3,000 square feet. Only 7% of PCPs and 12% of specialists live in homes with 5000 square feet or more.

At 22%, plastic surgeons and orthopedists were the most likely groups to have houses with the largest square footage, according to the survey.

About one in four physicians in five specialties (urology, cardiology, plastic surgery, otolaryngology, and critical care) reported that they had mortgages of more than $500,000.

Standard financial advice, the report authors note, is that a mortgage should take up no more than 28% of monthly gross income.

Another large source of debt came from student loans. Close to 80% of graduating medical students have educational debt. The average balance for graduating students in 2018 was $196,520, the report authors state.

Those in physical medicine/rehabilitation and family medicine were most likely to still be paying off student debt (34% said they were). Conversely, half as many nephrologists and rheumatologists (15%) and gastroenterologists (14%) reported that they were paying off educational debt.

Only 11% of physicians said they were currently free of any debt.

Most physicians in the survey (72%) reported that they had not experienced a significant financial loss in the past year.

For those who did experience such a loss, the top reason given was related to a bad investment or the stock market (9%).

Cost-cutting strategies

Revenue reduction will likely lead to spending less this year as the pandemic challenges continue.

Survey respondents offered their most effective cost-cutting strategies.

A hospitalist said, “Half of every bonus goes into the investment account, no matter how much.”

“We add an extra amount to the principal of our monthly mortgage payment,” an internist said.

A pediatrician offered, “I bring my lunch to work every day and don’t eat in restaurants often.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Telehealth and medical liability

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

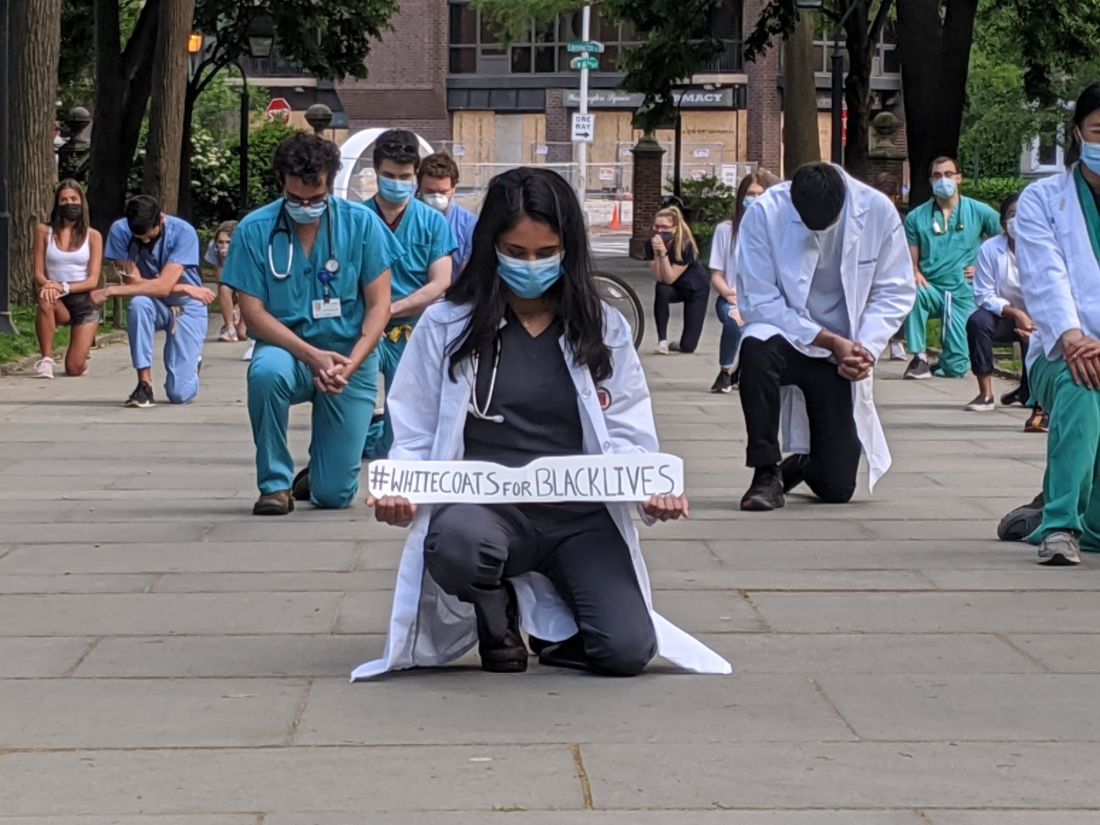

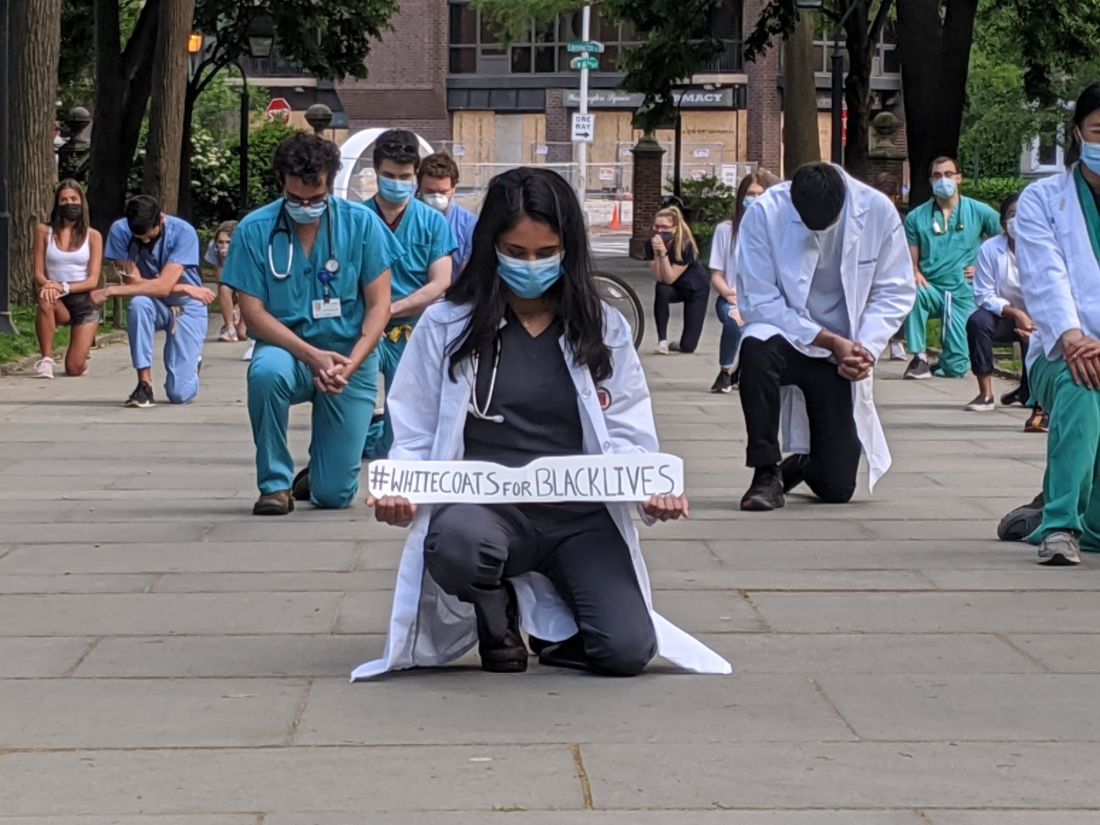

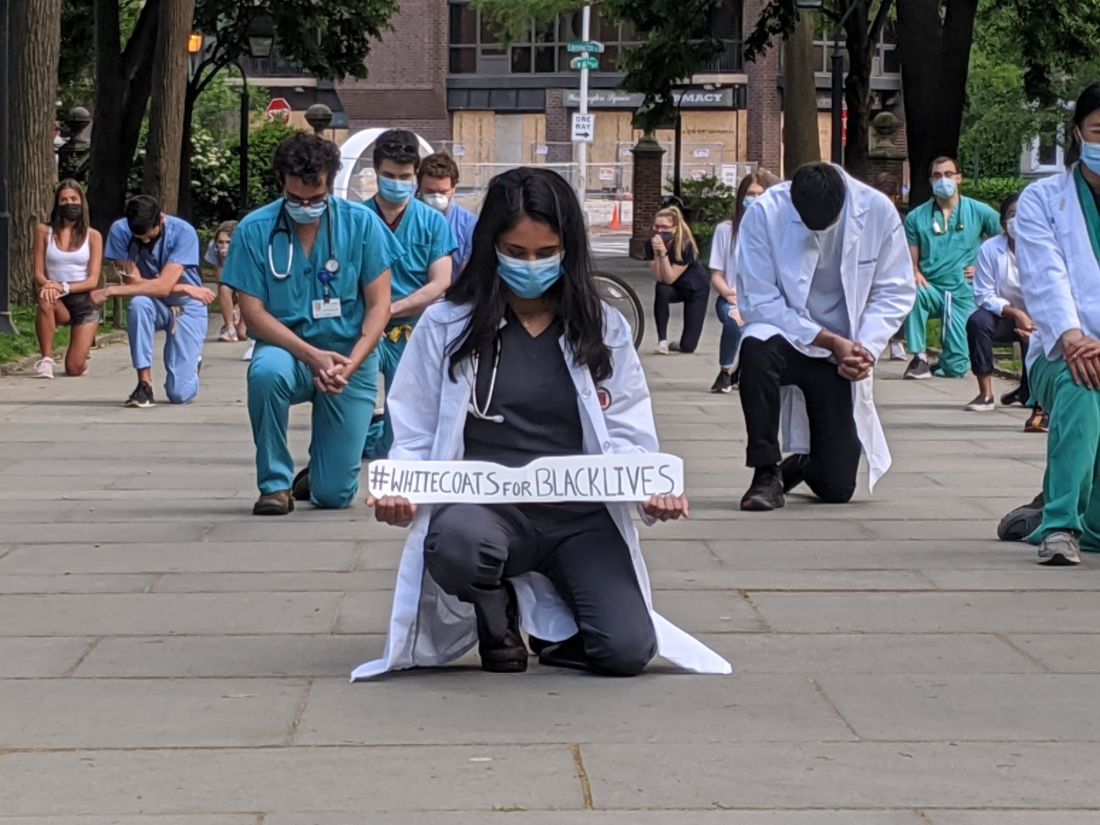

Hashtag medicine: #ShareTheMicNowMed highlights Black female physicians on social media

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s official: COVID-19 was bad for the health care business

COVID-19 took a huge cut of clinicians’ business in March and April

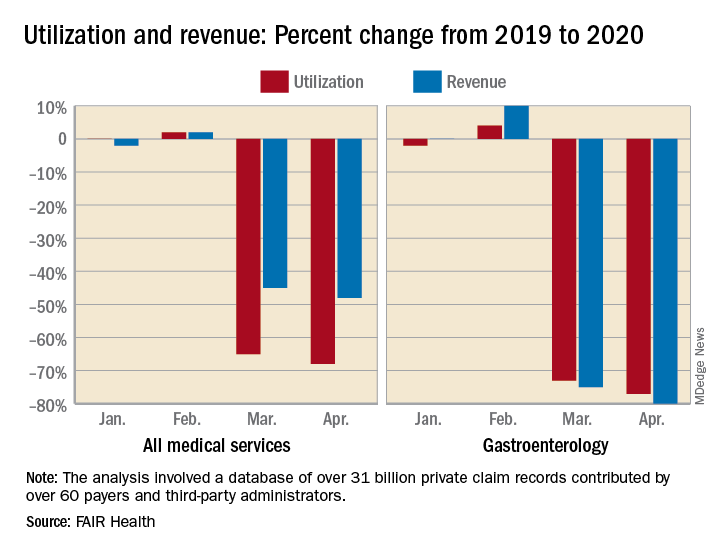

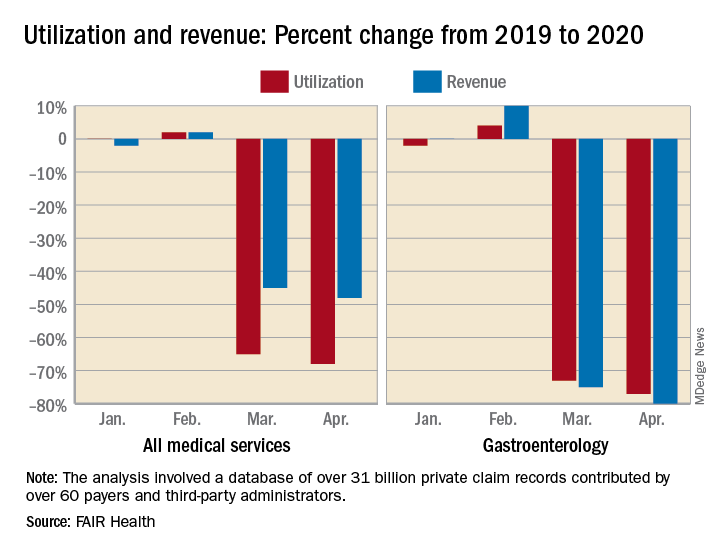

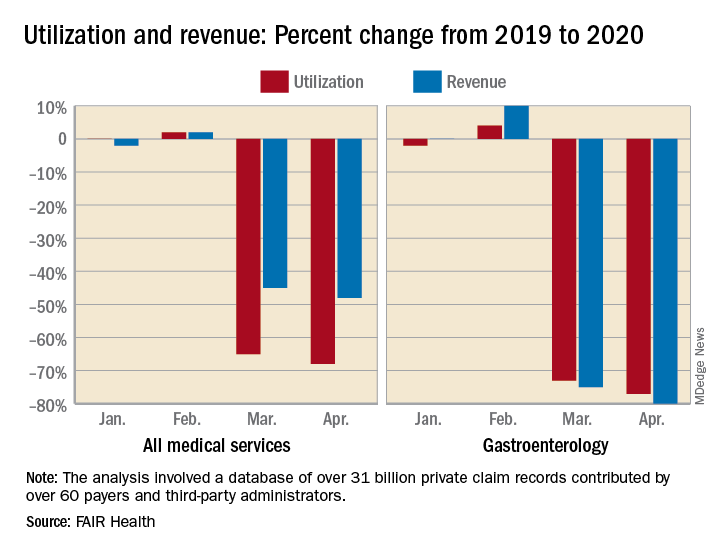

In the first 2 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care professionals experienced sharp drops in both utilization and revenue, according to an analysis of the nation’s largest collection of private health care claims data.

For the months of March and April 2020, use of medical professional services dropped by 65% and 68%, respectively, compared with last year, and estimated revenue fell by 45% and 48%, FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 billion claim records, said in a new report.

For the Northeast states – the epicenter of the pandemic in March and April – patient volume was down by 60% in March and 80% in April, while revenue fell by 55% in March and 79% in April, the organization said.

For this analysis, “a professional service was defined as any service provided by an individual (e.g., physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) instead of being billed by a facility,” FAIR Health noted. Figures for 2019 were adjusted using the Consumer Price Index.

The size of the pandemic-related decreases in utilization and income varied by specialty. Of the seven specialties included in the study, oral surgery was hit the hardest, followed by gastroenterology, cardiology, orthopedics, dermatology, adult primary care, and pediatric primary care, FAIR Health said.

After experiencing a 2% drop in utilization this January and an increase of 4% in February, compared with 2019, gastroenterology saw corresponding drops of 73% in March and 77% in April. Estimated revenue for the specialty was flat in January and rose by 10% in February, but plummeted by 75% in March and 80% in April, the FAIR Health data show.

In cardiology, patient volume from 2019 to 2020 looked like this: Down by 4% in January, up 5% in February, down by 62% in March, and down by 71% in April. The earnings numbers tell a similar story: Down by 2% in January, up by 15% in February, down by 57% in March, and down by 73% in April, the organization reported.

Dermatology did the best among the non–primary care specialties, but that was just a relative success. Utilization still dropped by 62% and 68% in March and April of 2020, compared with last year, and revenue declined by 50% in March and 59% in April, FAIR Health said.

For adult primary care, the utilization numbers were similar, but revenue took a somewhat smaller hit. Patient volume from 2019 to 2020 was fairly steady in January and February, then nosedived in March (down 60%) and April (down 68%). Earnings were up initially, rising 1% in January and 2% in February, but fell 47% in March and 54% in April, FAIR Health said.

Pediatric primary care, it appears, may have been buoyed somewhat by its younger patients. The specialty as a whole saw utilization tumble by 52% in March and 58% in April, but revenue dropped by just 32% and 35%, respectively, according to the report.

A little extra data diving showed that the figures for preventive care visits for patients aged 0-4 years in March and April were –2% and 0% for volume and –2% and 1% for revenue. Meanwhile, the volume of immunizations only dropped by 14% and 10% and vaccine-related revenue slipped by just 7% and 2%, FAIR Health noted.

“Across many specialties from January to April 2020, office or other outpatient [evaluation and management] visits became more common relative to other procedures. ... This may have been due in part to the fact that many of these E&M services could be rendered via telehealth,” FAIR Health said.

Telehealth, however, was no panacea, the report explained: “Even when medical practices have continued to function via telehealth, many have experienced lower reimbursements for telehealth visits than for in-person visits and more time educating patients on how to use the technology.”

COVID-19 took a huge cut of clinicians’ business in March and April

COVID-19 took a huge cut of clinicians’ business in March and April

In the first 2 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care professionals experienced sharp drops in both utilization and revenue, according to an analysis of the nation’s largest collection of private health care claims data.

For the months of March and April 2020, use of medical professional services dropped by 65% and 68%, respectively, compared with last year, and estimated revenue fell by 45% and 48%, FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 billion claim records, said in a new report.

For the Northeast states – the epicenter of the pandemic in March and April – patient volume was down by 60% in March and 80% in April, while revenue fell by 55% in March and 79% in April, the organization said.

For this analysis, “a professional service was defined as any service provided by an individual (e.g., physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) instead of being billed by a facility,” FAIR Health noted. Figures for 2019 were adjusted using the Consumer Price Index.

The size of the pandemic-related decreases in utilization and income varied by specialty. Of the seven specialties included in the study, oral surgery was hit the hardest, followed by gastroenterology, cardiology, orthopedics, dermatology, adult primary care, and pediatric primary care, FAIR Health said.

After experiencing a 2% drop in utilization this January and an increase of 4% in February, compared with 2019, gastroenterology saw corresponding drops of 73% in March and 77% in April. Estimated revenue for the specialty was flat in January and rose by 10% in February, but plummeted by 75% in March and 80% in April, the FAIR Health data show.

In cardiology, patient volume from 2019 to 2020 looked like this: Down by 4% in January, up 5% in February, down by 62% in March, and down by 71% in April. The earnings numbers tell a similar story: Down by 2% in January, up by 15% in February, down by 57% in March, and down by 73% in April, the organization reported.

Dermatology did the best among the non–primary care specialties, but that was just a relative success. Utilization still dropped by 62% and 68% in March and April of 2020, compared with last year, and revenue declined by 50% in March and 59% in April, FAIR Health said.

For adult primary care, the utilization numbers were similar, but revenue took a somewhat smaller hit. Patient volume from 2019 to 2020 was fairly steady in January and February, then nosedived in March (down 60%) and April (down 68%). Earnings were up initially, rising 1% in January and 2% in February, but fell 47% in March and 54% in April, FAIR Health said.

Pediatric primary care, it appears, may have been buoyed somewhat by its younger patients. The specialty as a whole saw utilization tumble by 52% in March and 58% in April, but revenue dropped by just 32% and 35%, respectively, according to the report.

A little extra data diving showed that the figures for preventive care visits for patients aged 0-4 years in March and April were –2% and 0% for volume and –2% and 1% for revenue. Meanwhile, the volume of immunizations only dropped by 14% and 10% and vaccine-related revenue slipped by just 7% and 2%, FAIR Health noted.

“Across many specialties from January to April 2020, office or other outpatient [evaluation and management] visits became more common relative to other procedures. ... This may have been due in part to the fact that many of these E&M services could be rendered via telehealth,” FAIR Health said.

Telehealth, however, was no panacea, the report explained: “Even when medical practices have continued to function via telehealth, many have experienced lower reimbursements for telehealth visits than for in-person visits and more time educating patients on how to use the technology.”

In the first 2 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care professionals experienced sharp drops in both utilization and revenue, according to an analysis of the nation’s largest collection of private health care claims data.

For the months of March and April 2020, use of medical professional services dropped by 65% and 68%, respectively, compared with last year, and estimated revenue fell by 45% and 48%, FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 billion claim records, said in a new report.

For the Northeast states – the epicenter of the pandemic in March and April – patient volume was down by 60% in March and 80% in April, while revenue fell by 55% in March and 79% in April, the organization said.

For this analysis, “a professional service was defined as any service provided by an individual (e.g., physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) instead of being billed by a facility,” FAIR Health noted. Figures for 2019 were adjusted using the Consumer Price Index.

The size of the pandemic-related decreases in utilization and income varied by specialty. Of the seven specialties included in the study, oral surgery was hit the hardest, followed by gastroenterology, cardiology, orthopedics, dermatology, adult primary care, and pediatric primary care, FAIR Health said.

After experiencing a 2% drop in utilization this January and an increase of 4% in February, compared with 2019, gastroenterology saw corresponding drops of 73% in March and 77% in April. Estimated revenue for the specialty was flat in January and rose by 10% in February, but plummeted by 75% in March and 80% in April, the FAIR Health data show.

In cardiology, patient volume from 2019 to 2020 looked like this: Down by 4% in January, up 5% in February, down by 62% in March, and down by 71% in April. The earnings numbers tell a similar story: Down by 2% in January, up by 15% in February, down by 57% in March, and down by 73% in April, the organization reported.

Dermatology did the best among the non–primary care specialties, but that was just a relative success. Utilization still dropped by 62% and 68% in March and April of 2020, compared with last year, and revenue declined by 50% in March and 59% in April, FAIR Health said.

For adult primary care, the utilization numbers were similar, but revenue took a somewhat smaller hit. Patient volume from 2019 to 2020 was fairly steady in January and February, then nosedived in March (down 60%) and April (down 68%). Earnings were up initially, rising 1% in January and 2% in February, but fell 47% in March and 54% in April, FAIR Health said.

Pediatric primary care, it appears, may have been buoyed somewhat by its younger patients. The specialty as a whole saw utilization tumble by 52% in March and 58% in April, but revenue dropped by just 32% and 35%, respectively, according to the report.

A little extra data diving showed that the figures for preventive care visits for patients aged 0-4 years in March and April were –2% and 0% for volume and –2% and 1% for revenue. Meanwhile, the volume of immunizations only dropped by 14% and 10% and vaccine-related revenue slipped by just 7% and 2%, FAIR Health noted.

“Across many specialties from January to April 2020, office or other outpatient [evaluation and management] visits became more common relative to other procedures. ... This may have been due in part to the fact that many of these E&M services could be rendered via telehealth,” FAIR Health said.

Telehealth, however, was no panacea, the report explained: “Even when medical practices have continued to function via telehealth, many have experienced lower reimbursements for telehealth visits than for in-person visits and more time educating patients on how to use the technology.”

Fighting COVID and police brutality, medical teams take to streets to treat protesters

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.

“I am working full time and basically being at the protest after getting straight off of work,” said Butler, who is black. That’s tiring, she added, but so is being a black woman in America.

After going out as a medic on her own, she soon met other volunteers. Together they used text-message chains to organize their efforts. One night, she responded to a man who had been shot with a rubber bullet in the chest; she said his torso had turned blue and purple from the impact. She also provided aid after a shooting near the protest left someone in critical condition.

“It’s hard, but bills need to be paid and justice needs to be served,” she said.

The street medic movement traces its roots, in part, to the 1960s protests, as well as the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party. Denver Action Medic Network offers a 20-hour training course that prepares them to treat patients in conflicts with police and large crowds; a four-hour session is offered to medical professionals as “bridge” training.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, the Denver Action Medic Network has added new training guidelines: Don’t go to protests if sick or in contact with those who are infected; wear a mask; give people lots of space and use hand sanitizer. Jordan Garcia, a 39-year-old medic for over 20 years who works with the network of veteran street medics, said they also warn medics about the increased risk of transmission because of protesters coughing from tear gas, and urge them to get tested for the virus after the protests.

The number of volunteer medics swelled after George Floyd’s May 25 killing in Minneapolis. In Denver alone, at least 40 people reached out to the Denver Action Medic Network for training.

On June 3, Dr. Rupa Marya, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California,San Francisco, and the co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition, which runs street medic training in the Bay Area, hosted a national webinar attended by over 3,000 medical professionals to provide the bridge training to be a street medic. In her online bio, Marya describes the coalition as “an organization of over 450 health workers committed to structural change” in addressing health problems.

“When we see suffering, that’s where we go,” Marya said. “And right now that suffering is happening on the streets.”

In the recent Denver protests, street medics responded to major head, face and eye injuries among protesters from what are sometimes described as “kinetic impact projectiles” or “less-than-lethal” bullets shot at protesters, along with tear-gas and flash-bang stun grenade canisters that either hit them or exploded in their faces.

Garcia, who by day works for an immigrant rights nonprofit, said that these weapons are not designed to be shot directly at people.

“We’re seeing police use these less-lethal weapons in lethal ways, and that is pretty upsetting,” Garcia said about the recent protests.

Denver police Chief Paul Pazen promised to make changes, including banning chokeholds and requiring SWAT teams to turn on their body cameras. Last week, a federal judge also issued a temporary injunction to stop Denver police from using tear gas and other less-than-lethal weapons in response to a class action lawsuit, in which a medic stated he was shot multiple times by police with pepper balls while treating patients. (Last week in North Carolina police were recorded destroying medic stations.)

Denver street medic Kevin Connell, a 30-year-old emergency room nurse, said he was hit with pepper balls in the back of his medic vest – which was clearly marked by red crosses – while treating a patient. He showed up to the Denver protests every night he did not have to work, he said, wearing a Kevlar medic vest, protective goggles and a homemade gas mask fashioned from a water bottle. As a member of the Denver Action Medic Network, Connell also served at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota in a dispute over the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I mean, as bad as it sounds, it was only tear gas, pepper balls and rubber bullets that were being fired on us,” Connell said of his recent experience in Denver. “When I was at Standing Rock, they were using high-powered water hoses even when it was, like, freezing cold. … So I think the police here had a little bit more restraint.”

Still, first-time street medic Aj Mossman, a 31-year-old Denver emergency medical technician studying for nursing school, was shocked to be tear-gassed and struck in the back of the leg with a flash grenade while treating a protester on May 30. Mossman still has a large leg bruise.

The following night, Mossman, who uses the pronoun they, brought more protective gear, but said they are still having difficulty processing what felt like a war zone.

“I thought I understood what my black friends went through. I thought I understood what the black community went through,” said Mossman, who is white. “But I had absolutely no idea how violent the police were and how little they cared about who they hurt.”

For Butler, serving as a medic with others from various walks of life was inspiring. “They’re also out there to protect black and brown bodies. And that’s amazing,” she said. “That’s just a beautiful sight.”

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, which is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.

“I am working full time and basically being at the protest after getting straight off of work,” said Butler, who is black. That’s tiring, she added, but so is being a black woman in America.

After going out as a medic on her own, she soon met other volunteers. Together they used text-message chains to organize their efforts. One night, she responded to a man who had been shot with a rubber bullet in the chest; she said his torso had turned blue and purple from the impact. She also provided aid after a shooting near the protest left someone in critical condition.

“It’s hard, but bills need to be paid and justice needs to be served,” she said.

The street medic movement traces its roots, in part, to the 1960s protests, as well as the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party. Denver Action Medic Network offers a 20-hour training course that prepares them to treat patients in conflicts with police and large crowds; a four-hour session is offered to medical professionals as “bridge” training.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, the Denver Action Medic Network has added new training guidelines: Don’t go to protests if sick or in contact with those who are infected; wear a mask; give people lots of space and use hand sanitizer. Jordan Garcia, a 39-year-old medic for over 20 years who works with the network of veteran street medics, said they also warn medics about the increased risk of transmission because of protesters coughing from tear gas, and urge them to get tested for the virus after the protests.

The number of volunteer medics swelled after George Floyd’s May 25 killing in Minneapolis. In Denver alone, at least 40 people reached out to the Denver Action Medic Network for training.

On June 3, Dr. Rupa Marya, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California,San Francisco, and the co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition, which runs street medic training in the Bay Area, hosted a national webinar attended by over 3,000 medical professionals to provide the bridge training to be a street medic. In her online bio, Marya describes the coalition as “an organization of over 450 health workers committed to structural change” in addressing health problems.

“When we see suffering, that’s where we go,” Marya said. “And right now that suffering is happening on the streets.”

In the recent Denver protests, street medics responded to major head, face and eye injuries among protesters from what are sometimes described as “kinetic impact projectiles” or “less-than-lethal” bullets shot at protesters, along with tear-gas and flash-bang stun grenade canisters that either hit them or exploded in their faces.

Garcia, who by day works for an immigrant rights nonprofit, said that these weapons are not designed to be shot directly at people.

“We’re seeing police use these less-lethal weapons in lethal ways, and that is pretty upsetting,” Garcia said about the recent protests.

Denver police Chief Paul Pazen promised to make changes, including banning chokeholds and requiring SWAT teams to turn on their body cameras. Last week, a federal judge also issued a temporary injunction to stop Denver police from using tear gas and other less-than-lethal weapons in response to a class action lawsuit, in which a medic stated he was shot multiple times by police with pepper balls while treating patients. (Last week in North Carolina police were recorded destroying medic stations.)

Denver street medic Kevin Connell, a 30-year-old emergency room nurse, said he was hit with pepper balls in the back of his medic vest – which was clearly marked by red crosses – while treating a patient. He showed up to the Denver protests every night he did not have to work, he said, wearing a Kevlar medic vest, protective goggles and a homemade gas mask fashioned from a water bottle. As a member of the Denver Action Medic Network, Connell also served at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota in a dispute over the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I mean, as bad as it sounds, it was only tear gas, pepper balls and rubber bullets that were being fired on us,” Connell said of his recent experience in Denver. “When I was at Standing Rock, they were using high-powered water hoses even when it was, like, freezing cold. … So I think the police here had a little bit more restraint.”

Still, first-time street medic Aj Mossman, a 31-year-old Denver emergency medical technician studying for nursing school, was shocked to be tear-gassed and struck in the back of the leg with a flash grenade while treating a protester on May 30. Mossman still has a large leg bruise.

The following night, Mossman, who uses the pronoun they, brought more protective gear, but said they are still having difficulty processing what felt like a war zone.

“I thought I understood what my black friends went through. I thought I understood what the black community went through,” said Mossman, who is white. “But I had absolutely no idea how violent the police were and how little they cared about who they hurt.”

For Butler, serving as a medic with others from various walks of life was inspiring. “They’re also out there to protect black and brown bodies. And that’s amazing,” she said. “That’s just a beautiful sight.”

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, which is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.

“I am working full time and basically being at the protest after getting straight off of work,” said Butler, who is black. That’s tiring, she added, but so is being a black woman in America.

After going out as a medic on her own, she soon met other volunteers. Together they used text-message chains to organize their efforts. One night, she responded to a man who had been shot with a rubber bullet in the chest; she said his torso had turned blue and purple from the impact. She also provided aid after a shooting near the protest left someone in critical condition.

“It’s hard, but bills need to be paid and justice needs to be served,” she said.

The street medic movement traces its roots, in part, to the 1960s protests, as well as the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party. Denver Action Medic Network offers a 20-hour training course that prepares them to treat patients in conflicts with police and large crowds; a four-hour session is offered to medical professionals as “bridge” training.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, the Denver Action Medic Network has added new training guidelines: Don’t go to protests if sick or in contact with those who are infected; wear a mask; give people lots of space and use hand sanitizer. Jordan Garcia, a 39-year-old medic for over 20 years who works with the network of veteran street medics, said they also warn medics about the increased risk of transmission because of protesters coughing from tear gas, and urge them to get tested for the virus after the protests.

The number of volunteer medics swelled after George Floyd’s May 25 killing in Minneapolis. In Denver alone, at least 40 people reached out to the Denver Action Medic Network for training.

On June 3, Dr. Rupa Marya, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California,San Francisco, and the co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition, which runs street medic training in the Bay Area, hosted a national webinar attended by over 3,000 medical professionals to provide the bridge training to be a street medic. In her online bio, Marya describes the coalition as “an organization of over 450 health workers committed to structural change” in addressing health problems.

“When we see suffering, that’s where we go,” Marya said. “And right now that suffering is happening on the streets.”

In the recent Denver protests, street medics responded to major head, face and eye injuries among protesters from what are sometimes described as “kinetic impact projectiles” or “less-than-lethal” bullets shot at protesters, along with tear-gas and flash-bang stun grenade canisters that either hit them or exploded in their faces.

Garcia, who by day works for an immigrant rights nonprofit, said that these weapons are not designed to be shot directly at people.

“We’re seeing police use these less-lethal weapons in lethal ways, and that is pretty upsetting,” Garcia said about the recent protests.

Denver police Chief Paul Pazen promised to make changes, including banning chokeholds and requiring SWAT teams to turn on their body cameras. Last week, a federal judge also issued a temporary injunction to stop Denver police from using tear gas and other less-than-lethal weapons in response to a class action lawsuit, in which a medic stated he was shot multiple times by police with pepper balls while treating patients. (Last week in North Carolina police were recorded destroying medic stations.)

Denver street medic Kevin Connell, a 30-year-old emergency room nurse, said he was hit with pepper balls in the back of his medic vest – which was clearly marked by red crosses – while treating a patient. He showed up to the Denver protests every night he did not have to work, he said, wearing a Kevlar medic vest, protective goggles and a homemade gas mask fashioned from a water bottle. As a member of the Denver Action Medic Network, Connell also served at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota in a dispute over the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I mean, as bad as it sounds, it was only tear gas, pepper balls and rubber bullets that were being fired on us,” Connell said of his recent experience in Denver. “When I was at Standing Rock, they were using high-powered water hoses even when it was, like, freezing cold. … So I think the police here had a little bit more restraint.”

Still, first-time street medic Aj Mossman, a 31-year-old Denver emergency medical technician studying for nursing school, was shocked to be tear-gassed and struck in the back of the leg with a flash grenade while treating a protester on May 30. Mossman still has a large leg bruise.

The following night, Mossman, who uses the pronoun they, brought more protective gear, but said they are still having difficulty processing what felt like a war zone.

“I thought I understood what my black friends went through. I thought I understood what the black community went through,” said Mossman, who is white. “But I had absolutely no idea how violent the police were and how little they cared about who they hurt.”

For Butler, serving as a medic with others from various walks of life was inspiring. “They’re also out there to protect black and brown bodies. And that’s amazing,” she said. “That’s just a beautiful sight.”

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, which is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Money worries during COVID-19? Six tips to keep your finances afloat

Even before Atlanta had an official shelter-in-place order, patients at the private plastic surgery practice of Nicholas Jones, MD, began canceling and rescheduled planned procedures.

After a few weeks, Dr. Jones, aged 40 years, stopped seeing patients entirely, but as a self-employed independent contractor, that means he’d lost most of his income. Dr. Jones still makes some money via a wound care job at a local nursing home, but he’s concerned that job may also be eliminated.

“I’m not hurting yet,” he said. “But I’m preparing for the worst possible scenario.”

In preparation, he and his fiancé have cut back on extraneous expenses like Uber Eats, magazine subscriptions, and streaming music services. Even though he has a 6-month emergency fund, Jones has reached out to utility companies, mortgage lenders, and student loan servicers to find out about any programs they offer to people who’ve suffered financially from the coronavirus crisis.

He’s also considered traveling to one of the COVID-19 epicenters – he has family in New Orleans and Chicago – to work in a hospital there. Jones has trauma experience and is double-boarded in general and plastic surgery.

“I could provide relief to those in need and also float through this troubled time with some financial relief,” he said.

Whereas much of the world’s attention has been on physicians who are on the front line and working around the clock in hospitals to help COVID-19 patients, thousands of other physicians are experiencing the opposite phenomenon – a slowdown or even stoppage of work (and income) altogether.

Even among those practices that remain open, the number of patients has declined as people avoid going to the office unless they absolutely have to.

At the same time, doctors in two-income households may have a spouse experiencing a job loss or income decline. Nearly 10 million Americans applied for unemployment benefits in the last 2 weeks of March, the largest number on record.

Still, while there’s uncertainty around how long the coronavirus crisis will last, experts agree that at some point America will return to a “new normal” and business operations will begin to reopen. For physicians experiencing a reduction in income who, like Jones, have an emergency fund with a few months’ worth of expenses, now’s the time to tap into it. (Or if you still have income, now’s the time to focus on growing that emergency fund to give yourself an even bigger safety net.)

If you’re among the more than half of Americans with less than 6 months of expenses saved for a rainy day, here’s how to stay afloat in the near term:

Cut back on expenses

Some household spending has naturally tapered off for many families because social distancing restrictions reduce spending on eating out, travel, and other leisure activities. But this is also an opportunity to look for other ways to reduce spending. Look through your credit card bills to see whether there are recurring payments you can cut, such as a payment to a gym that’s temporarily closed or a monthly subscription box that you don’t need.

Some gyms are not allowing membership termination right now, but it pays to ask. If a service you’re not using won’t facilitate the cancellation, call your credit card company to dispute and stop the charges, and report them to the Better Business Bureau.

You should also stop contributing to nonemergency savings accounts such as your retirement fund or your children’s college funds.

“A lot of people are hesitant to stop their automatic savings if they’ve been maxing out their 401(k) contribution or 529 accounts,” says Andrew Musbach, a certified financial planner and cofounder of MD Wealth Management in Chelsea, Mich. “But if you’re thinking long term, the reality is that missing a couple of months won’t make or break a plan. Cutting back on the amount you’re saving in the short term will increase your cash flow and is a good way to make ends meet.”

Take advantage of regulatory changes