User login

Good for profits, good for patients: A new form of medical visits

Ten patients smiled and waved out on the computer monitor, as Jacob Mirsky, MD, greeted each one, asked them to introduce themselves, and inquired as to how each was doing with their stress reduction tactics.

The attendees of the online session had been patients at in-person group visits at the Massachusetts General Hospital Revere HealthCare Center. But those in-person group sessions, known as shared medical appointments (SMAs), were shut down when COVID-19 arrived.

“Our group patients have been missing the sessions,” said Dr. Mirsky, a general internist who codirects the center’s group visit program. The online sessions, called virtual SMAs (V-SMAs), work well with COVID-19 social distancing.

In the group sessions, Dr. Mirsky reads a standardized message that addresses privacy concerns during the session. For the next 60-90 minutes, “we ask them to talk about what has gone well for them and what they are struggling with,” he said. “Then I answer their questions using materials in a PowerPoint to address key points, such as reducing salt for high blood pressure or interpreting blood sugar levels for diabetes.

“I try to end group sessions with one area of focus,” Dr. Mirsky said. “In the stress reduction group, this could be meditation. In the diabetes group, it could be a discussion on weight loss.” Then the program’s health coach goes over some key concepts on behavior change and invites participants to contact her after the session.

“The nice thing is that these virtual sessions are fully reimbursable by all of our insurers in Massachusetts,” Dr. Mirsky said. Through evaluation and management (E/M) codes, each patient in a group visit is paid the same as a patient in an individual visit with the same level of complexity.

Dr. Mirsky writes a note in the chart about each patient who was in the group session. “This includes information about the specific patient, such as the history and physical, and information about the group meeting,” he said. In the next few months, the center plans to put its other group sessions online – on blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and insomnia.

Attracting doctors who hadn’t done groups before

said Marianne Sumego, MD, director of the Cleveland Clinic’s SMA program, which began 21 years ago.

In this era of COVID-19, group visits have either switched to V-SMAs or halted. However, the COVID-19 crisis has given group visits a second wind. Some doctors who never used SMAs before are now trying out this new mode of patient engagement,

Many of the 100 doctors using SMAs at the Cleveland Clinic have switched over to V-SMAs for now, and the new mode is also attracting colleagues who are new to SMAs, she said.

“When doctors started using telemedicine, virtual group visits started making sense to them,” Dr. Sumego said. “This is a time of a great deal of experimentation in practice design.”

Indeed, V-SMAs have eliminated some problems that had discouraged doctors from trying SMAs, said Amy Wheeler, MD, a general internist who founded the Revere SMA program and codirects it with Dr. Mirsky.

V-SMAs eliminate the need for a large space to hold sessions and reduce the number of staff needed to run sessions, Dr. Wheeler said. “Virtual group visits can actually be easier to use than in-person group visits.”

Dr. Sumego believes small practices in particular will take up V-SMAs because they are easier to run than regular SMAs. “Necessity drives change,” she said. “Across the country everyone is looking at the virtual group model.”

Group visits can help your bottom line

Medicare and many private payers cover group visits. In most cases, they tend to pay the same rate as for an individual office visit. As with telehealth, Medicare and many other payers are temporarily reimbursing for virtual visits at the same rate as for real visits.

Not all payers have a stated policy about covering SMAs, and physicians have to ask. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, for example, has not published any coding rules on SMAs. But in response to a query by the American Academy of Family Physicians, CMS said it would allow use of CPT codes for E/M services for individual patients.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina is one of the few payers with a clearly stated policy on its website. Like Medicare, the insurer accepts E/M codes, and it requires that patients’ attendance must be voluntary; they must be established patients; and the visit must be specific to a disease or condition, although several conditions are allowed.

Dr. Mirsky said his group uses the same E/M level – 99213 – for all of his SMA patients. “Since a regular primary care visit is usually billed at a level 3 or 4, depending on how many topics are covered, we chose level 3 for groups, because the group session deals with just one topic.”

One challenge for billing for SMAs is that most health insurers require patients to provide a copay for each visit, which can discourage patients in groups that meet frequently, says Wayne Dysinger, MD, founder of Lifestyle Medical Solutions, a two-physician primary care practice in Riverside, Calif.

But Dr. Dysinger, who has been using SMAs for 5 years, usually doesn’t have to worry about copays because much of his work is capitated and doesn’t require a copay.

Also, some of Dr. Dysinger’s SMA patients are in direct primary care, in which the patients pay an $18 monthly membership fee. Other practices may charge a flat out-of-pocket fee.

How group visits operate

SMAs are based on the observation that patients with the same condition generally ask their doctor the same questions, and rather than repeat the answers each time, why not provide them to a group?

Dr. Wheeler said trying to be more efficient with her time was the primary reason she became interested in SMAs a dozen years ago. “I was trying to squeeze the advice patients needed into a normal patient visit, and it wasn’t working. When I tried to tell them everything they needed to know, I’d run behind for the rest of my day’s visits.”

She found she was continually repeating the same conversation with patients, but these talks weren’t detailed enough to be effective. “When my weight loss patients came back for the next appointment, they had not made the recommended changes in lifestyle. I started to realize how complicated weight loss was.” So Dr. Wheeler founded the SMA program at the Revere Center.

Doctors enjoy the patient interaction

Some doctors who use SMAs talk about how connected they feel with their patients. “For me, the group sessions are the most gratifying part of the week,” Dr. Dysinger says. “I like to see the patients interacting with me and with each other, and watch their health behavior change over time.”

“These groups have a great deal of energy,” he said. “They have a kind of vulnerability that is very raw, very human. People make commitments to meet goals. Will they meet them or not?”

Dr. Dysinger’s enthusiasm has been echoed by other doctors. In a study of older patients, physicians who used SMAs were more satisfied with care than physicians who relied on standard one-to-one interactions. In another study, the researchers surmised that, in SMAs, doctors learn from their patients how they can better meet their needs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks SMAs are widely applicable in primary care. He estimates that 80%-85% of appointments at a primary care practice involve chronic diseases, and this type of patient is a good fit for group visits. SMAs typically treat patients with diabetes, asthma, arthritis, and obesity.

Dr. Sumego said SMAs are used for specialty care at Cleveland Clinic, such as to help patients before and after bariatric surgery. SMAs have also been used to treat patients with ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, cancer, HIV, menopause, insomnia, and stress, according to one report.

Dr. Dysinger, who runs a small practice, organizes his group sessions somewhat differently. He doesn’t organize his groups around conditions like diabetes, but instead his groups focus on four “pillars” of lifestyle medicine: nourishment, movement, resilience (involving sleep and stress), and connectedness.

Why patients like group visits

Feeling part of a whole is a major draw for many patients. “Patients seem to like committing to something bigger than just themselves,” Dr. Wheeler said. “They enjoy the sense of community that groups have, the joy of supporting one another.”

“It’s feeling that you’re not alone,” Dr. Mirsky said. “When a patient struggling with diabetes hears how hard it is for another patient, it validates their experience and gives them someone to connect with. There is a positive peer pressure.”

Many programs, including Dr. Wheeler’s and Dr. Mirsky’s in Boston, allow patients to drop in and out of sessions, rather than attending one course all the way through. But even under this format, Dr. Wheeler said that patients often tend to stick together. “At the end of a session, one patient asks another: ‘Which session do you want to go to next?’ ” she said.

Patients also learn from each other in SMAs. Patients exchange experiences and share advice they may not have had the chance to get during an individual visit.

The group dynamic can make it easier for some patients to reveal sensitive information, said Dr. Dysinger. “In these groups, people feel free to talk about their bowel movements, or about having to deal with the influence of a parent on their lives,” Dr. Dysinger said. “The sessions can have the feel of an [Alcoholics Anonymous] meeting, but they’re firmly grounded in medicine.”

Potential downsides of virtual group visits

SMAs and VSMAs may not work for every practice. Some small practices may not have enough patients to organize a group visit around a particular condition – even a common one like diabetes. In a presentation before the Society of General Internal Medicine, a physician from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, warned that it may be difficult for a practice to fill diabetes group visits every year.

Additionally, some patients don’t want to talk about personal matters in a group. “They may not want to reveal certain things about themselves,” Dr. Mirsky said. “So I tell the group that if there is anything that anyone wants to talk about in private, I’m available.”

Another drawback of SMAs is that more experienced patients may have to slog through information they already know, which is a particular problem when patients can drop in and out of sessions. Dr. Mirsky noted that “what often ends up happening is that the experienced participant helps the newcomer.”

Finally, confidentially is a big concern in a group session. “In a one-on-one visit, you can go into details about the patient’s health, and even bring up an entry in the chart,” Dr. Wheeler said. “But in a group visit, you can’t raise any personal details about a patient unless the patient brings it up first.”

SMA patients sign confidentiality agreements in which they agree not to talk about other patients outside the session. Ensuring confidentiality becomes more complicated in virtual group visits, because someone located in the room near a participant could overhear the conversation. For this reason, patients in V-SMAs are advised to use headphones or, at a minimum, close the door to the room they are in.

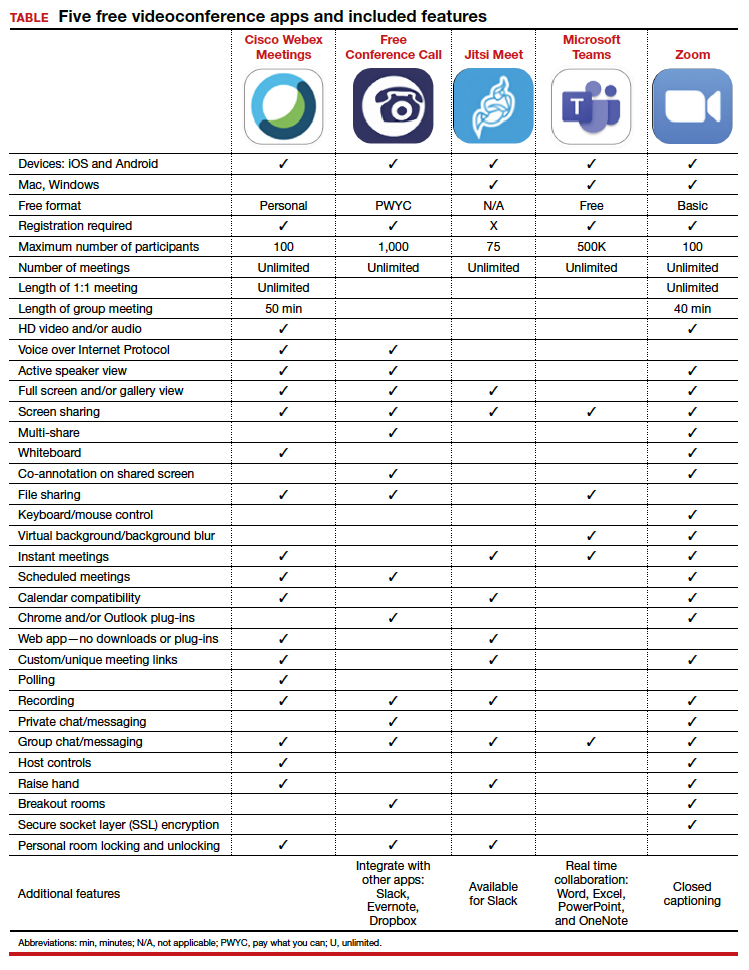

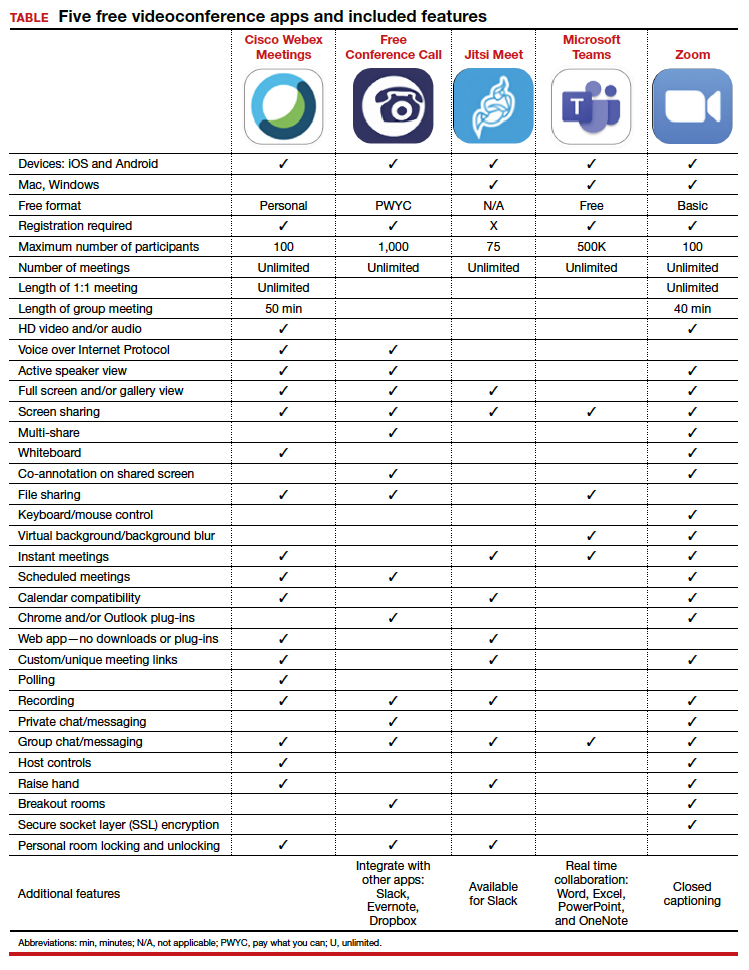

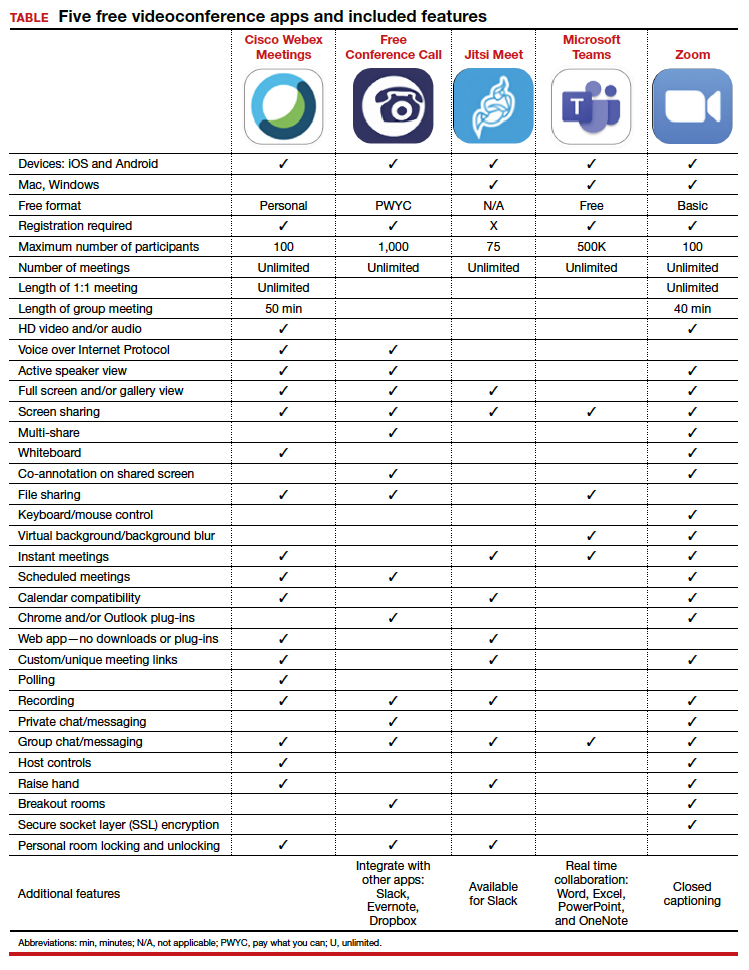

To address privacy concerns, Zoom encrypts its data, but some privacy breeches have been reported, and a U.S. senator has been looking into Zoom’s privacy vulnerabilities.

Transferring groups to virtual groups

It took the COVID-19 crisis for most doctors to take up virtual SMAs. Dr. Sumego said that the Cleveland Clinic started virtual SMAs more than a year ago, but most other groups operating SMAs were apparently not providing them virtually before COVID-19 started.

Dr. Dysinger said he tried virtual SMAs in 2017 but dropped them because the technology – using Zoom – was challenging at the time, and his staff and most patients were resistant. “Only three to five people were attending the virtual sessions, and the meetings took place in the evening, which was hard on the staff.”

“When COVID-19 first appeared, our initial response was to try to keep the in-person group and add social distancing to it, but that wasn’t workable, so very quickly we shifted to Zoom meetings,” Dr. Dysinger said. “We had experience with Zoom already, and the Zoom technology had improved and was easier to use. COVID-19 forced it all forward.”

Are V-SMAs effective? While there have been many studies showing the effectiveness of in-person SMAs, there have been very few on V-SMAs. One 2018 study of obesity patients found that those attending in-person SMAs lost somewhat more weight than those in V-SMAs.

As with telemedicine, some patients have trouble with the technology of V-SMAs. Dr. Dysinger said 5%-10% of his SMA patients don’t make the switch over to V-SMAs – mainly because of problems in adapting to the technology – but the rest are happy. “We’re averaging 10 people per meeting, and as many as 20.”

Getting comfortable with group visits

Dealing with group visits takes a very different mindset than what doctors normally have, Dr. Wheeler said. “It took me 6-8 months to feel comfortable enough with group sessions to do them myself,” she recalled. “This was a very different way to practice, compared to the one-on-one care I was trained to give patients. Others may find the transition easier, though.

“Doctors are used to being in control of the patient visit, but the exchange in a group visit is more fluid,” Dr. Wheeler said. “Patients offer their own opinions, and this sends the discussion off on a tangent that is often quite useful. As doctors, we have to learn when to let these tangents continue, and know when the discussion might have to be brought back to the theme at hand. Often it’s better not to intercede.”

Do doctors need training to conduct SMAs? Patients in group visits reported worse communication with physicians than those in individual visits, according to a 2014 study. The authors surmised that the doctors needed to learn how to talk to groups and suggested that they get some training.

The potential staying power of V-SMAs post COVID?

Once the COVID-19 crisis is over, Medicare is scheduled to no longer provide the same level of reimbursement for virtual sessions as for real sessions. Dr. Mirsky anticipates a great deal of resistance to this change from thousands of physicians and patients who have become comfortable with telehealth, including virtual SMAs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks V-SMAs will continue. “When COVID-19 clears and we can go back to in-person groups, we expect to keep some virtual groups. People have already come to accept and value virtual groups.”

Dr. Wheeler sees virtual groups playing an essential role post COVID-19, when practices have to get back up to speed. “Virtual group visits could make it easier to deal with a large backlog of patients who couldn’t be seen up until now,” she said. “And virtual groups will be the only way to see patients who are still reluctant to meet in a group.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ten patients smiled and waved out on the computer monitor, as Jacob Mirsky, MD, greeted each one, asked them to introduce themselves, and inquired as to how each was doing with their stress reduction tactics.

The attendees of the online session had been patients at in-person group visits at the Massachusetts General Hospital Revere HealthCare Center. But those in-person group sessions, known as shared medical appointments (SMAs), were shut down when COVID-19 arrived.

“Our group patients have been missing the sessions,” said Dr. Mirsky, a general internist who codirects the center’s group visit program. The online sessions, called virtual SMAs (V-SMAs), work well with COVID-19 social distancing.

In the group sessions, Dr. Mirsky reads a standardized message that addresses privacy concerns during the session. For the next 60-90 minutes, “we ask them to talk about what has gone well for them and what they are struggling with,” he said. “Then I answer their questions using materials in a PowerPoint to address key points, such as reducing salt for high blood pressure or interpreting blood sugar levels for diabetes.

“I try to end group sessions with one area of focus,” Dr. Mirsky said. “In the stress reduction group, this could be meditation. In the diabetes group, it could be a discussion on weight loss.” Then the program’s health coach goes over some key concepts on behavior change and invites participants to contact her after the session.

“The nice thing is that these virtual sessions are fully reimbursable by all of our insurers in Massachusetts,” Dr. Mirsky said. Through evaluation and management (E/M) codes, each patient in a group visit is paid the same as a patient in an individual visit with the same level of complexity.

Dr. Mirsky writes a note in the chart about each patient who was in the group session. “This includes information about the specific patient, such as the history and physical, and information about the group meeting,” he said. In the next few months, the center plans to put its other group sessions online – on blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and insomnia.

Attracting doctors who hadn’t done groups before

said Marianne Sumego, MD, director of the Cleveland Clinic’s SMA program, which began 21 years ago.

In this era of COVID-19, group visits have either switched to V-SMAs or halted. However, the COVID-19 crisis has given group visits a second wind. Some doctors who never used SMAs before are now trying out this new mode of patient engagement,

Many of the 100 doctors using SMAs at the Cleveland Clinic have switched over to V-SMAs for now, and the new mode is also attracting colleagues who are new to SMAs, she said.

“When doctors started using telemedicine, virtual group visits started making sense to them,” Dr. Sumego said. “This is a time of a great deal of experimentation in practice design.”

Indeed, V-SMAs have eliminated some problems that had discouraged doctors from trying SMAs, said Amy Wheeler, MD, a general internist who founded the Revere SMA program and codirects it with Dr. Mirsky.

V-SMAs eliminate the need for a large space to hold sessions and reduce the number of staff needed to run sessions, Dr. Wheeler said. “Virtual group visits can actually be easier to use than in-person group visits.”

Dr. Sumego believes small practices in particular will take up V-SMAs because they are easier to run than regular SMAs. “Necessity drives change,” she said. “Across the country everyone is looking at the virtual group model.”

Group visits can help your bottom line

Medicare and many private payers cover group visits. In most cases, they tend to pay the same rate as for an individual office visit. As with telehealth, Medicare and many other payers are temporarily reimbursing for virtual visits at the same rate as for real visits.

Not all payers have a stated policy about covering SMAs, and physicians have to ask. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, for example, has not published any coding rules on SMAs. But in response to a query by the American Academy of Family Physicians, CMS said it would allow use of CPT codes for E/M services for individual patients.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina is one of the few payers with a clearly stated policy on its website. Like Medicare, the insurer accepts E/M codes, and it requires that patients’ attendance must be voluntary; they must be established patients; and the visit must be specific to a disease or condition, although several conditions are allowed.

Dr. Mirsky said his group uses the same E/M level – 99213 – for all of his SMA patients. “Since a regular primary care visit is usually billed at a level 3 or 4, depending on how many topics are covered, we chose level 3 for groups, because the group session deals with just one topic.”

One challenge for billing for SMAs is that most health insurers require patients to provide a copay for each visit, which can discourage patients in groups that meet frequently, says Wayne Dysinger, MD, founder of Lifestyle Medical Solutions, a two-physician primary care practice in Riverside, Calif.

But Dr. Dysinger, who has been using SMAs for 5 years, usually doesn’t have to worry about copays because much of his work is capitated and doesn’t require a copay.

Also, some of Dr. Dysinger’s SMA patients are in direct primary care, in which the patients pay an $18 monthly membership fee. Other practices may charge a flat out-of-pocket fee.

How group visits operate

SMAs are based on the observation that patients with the same condition generally ask their doctor the same questions, and rather than repeat the answers each time, why not provide them to a group?

Dr. Wheeler said trying to be more efficient with her time was the primary reason she became interested in SMAs a dozen years ago. “I was trying to squeeze the advice patients needed into a normal patient visit, and it wasn’t working. When I tried to tell them everything they needed to know, I’d run behind for the rest of my day’s visits.”

She found she was continually repeating the same conversation with patients, but these talks weren’t detailed enough to be effective. “When my weight loss patients came back for the next appointment, they had not made the recommended changes in lifestyle. I started to realize how complicated weight loss was.” So Dr. Wheeler founded the SMA program at the Revere Center.

Doctors enjoy the patient interaction

Some doctors who use SMAs talk about how connected they feel with their patients. “For me, the group sessions are the most gratifying part of the week,” Dr. Dysinger says. “I like to see the patients interacting with me and with each other, and watch their health behavior change over time.”

“These groups have a great deal of energy,” he said. “They have a kind of vulnerability that is very raw, very human. People make commitments to meet goals. Will they meet them or not?”

Dr. Dysinger’s enthusiasm has been echoed by other doctors. In a study of older patients, physicians who used SMAs were more satisfied with care than physicians who relied on standard one-to-one interactions. In another study, the researchers surmised that, in SMAs, doctors learn from their patients how they can better meet their needs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks SMAs are widely applicable in primary care. He estimates that 80%-85% of appointments at a primary care practice involve chronic diseases, and this type of patient is a good fit for group visits. SMAs typically treat patients with diabetes, asthma, arthritis, and obesity.

Dr. Sumego said SMAs are used for specialty care at Cleveland Clinic, such as to help patients before and after bariatric surgery. SMAs have also been used to treat patients with ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, cancer, HIV, menopause, insomnia, and stress, according to one report.

Dr. Dysinger, who runs a small practice, organizes his group sessions somewhat differently. He doesn’t organize his groups around conditions like diabetes, but instead his groups focus on four “pillars” of lifestyle medicine: nourishment, movement, resilience (involving sleep and stress), and connectedness.

Why patients like group visits

Feeling part of a whole is a major draw for many patients. “Patients seem to like committing to something bigger than just themselves,” Dr. Wheeler said. “They enjoy the sense of community that groups have, the joy of supporting one another.”

“It’s feeling that you’re not alone,” Dr. Mirsky said. “When a patient struggling with diabetes hears how hard it is for another patient, it validates their experience and gives them someone to connect with. There is a positive peer pressure.”

Many programs, including Dr. Wheeler’s and Dr. Mirsky’s in Boston, allow patients to drop in and out of sessions, rather than attending one course all the way through. But even under this format, Dr. Wheeler said that patients often tend to stick together. “At the end of a session, one patient asks another: ‘Which session do you want to go to next?’ ” she said.

Patients also learn from each other in SMAs. Patients exchange experiences and share advice they may not have had the chance to get during an individual visit.

The group dynamic can make it easier for some patients to reveal sensitive information, said Dr. Dysinger. “In these groups, people feel free to talk about their bowel movements, or about having to deal with the influence of a parent on their lives,” Dr. Dysinger said. “The sessions can have the feel of an [Alcoholics Anonymous] meeting, but they’re firmly grounded in medicine.”

Potential downsides of virtual group visits

SMAs and VSMAs may not work for every practice. Some small practices may not have enough patients to organize a group visit around a particular condition – even a common one like diabetes. In a presentation before the Society of General Internal Medicine, a physician from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, warned that it may be difficult for a practice to fill diabetes group visits every year.

Additionally, some patients don’t want to talk about personal matters in a group. “They may not want to reveal certain things about themselves,” Dr. Mirsky said. “So I tell the group that if there is anything that anyone wants to talk about in private, I’m available.”

Another drawback of SMAs is that more experienced patients may have to slog through information they already know, which is a particular problem when patients can drop in and out of sessions. Dr. Mirsky noted that “what often ends up happening is that the experienced participant helps the newcomer.”

Finally, confidentially is a big concern in a group session. “In a one-on-one visit, you can go into details about the patient’s health, and even bring up an entry in the chart,” Dr. Wheeler said. “But in a group visit, you can’t raise any personal details about a patient unless the patient brings it up first.”

SMA patients sign confidentiality agreements in which they agree not to talk about other patients outside the session. Ensuring confidentiality becomes more complicated in virtual group visits, because someone located in the room near a participant could overhear the conversation. For this reason, patients in V-SMAs are advised to use headphones or, at a minimum, close the door to the room they are in.

To address privacy concerns, Zoom encrypts its data, but some privacy breeches have been reported, and a U.S. senator has been looking into Zoom’s privacy vulnerabilities.

Transferring groups to virtual groups

It took the COVID-19 crisis for most doctors to take up virtual SMAs. Dr. Sumego said that the Cleveland Clinic started virtual SMAs more than a year ago, but most other groups operating SMAs were apparently not providing them virtually before COVID-19 started.

Dr. Dysinger said he tried virtual SMAs in 2017 but dropped them because the technology – using Zoom – was challenging at the time, and his staff and most patients were resistant. “Only three to five people were attending the virtual sessions, and the meetings took place in the evening, which was hard on the staff.”

“When COVID-19 first appeared, our initial response was to try to keep the in-person group and add social distancing to it, but that wasn’t workable, so very quickly we shifted to Zoom meetings,” Dr. Dysinger said. “We had experience with Zoom already, and the Zoom technology had improved and was easier to use. COVID-19 forced it all forward.”

Are V-SMAs effective? While there have been many studies showing the effectiveness of in-person SMAs, there have been very few on V-SMAs. One 2018 study of obesity patients found that those attending in-person SMAs lost somewhat more weight than those in V-SMAs.

As with telemedicine, some patients have trouble with the technology of V-SMAs. Dr. Dysinger said 5%-10% of his SMA patients don’t make the switch over to V-SMAs – mainly because of problems in adapting to the technology – but the rest are happy. “We’re averaging 10 people per meeting, and as many as 20.”

Getting comfortable with group visits

Dealing with group visits takes a very different mindset than what doctors normally have, Dr. Wheeler said. “It took me 6-8 months to feel comfortable enough with group sessions to do them myself,” she recalled. “This was a very different way to practice, compared to the one-on-one care I was trained to give patients. Others may find the transition easier, though.

“Doctors are used to being in control of the patient visit, but the exchange in a group visit is more fluid,” Dr. Wheeler said. “Patients offer their own opinions, and this sends the discussion off on a tangent that is often quite useful. As doctors, we have to learn when to let these tangents continue, and know when the discussion might have to be brought back to the theme at hand. Often it’s better not to intercede.”

Do doctors need training to conduct SMAs? Patients in group visits reported worse communication with physicians than those in individual visits, according to a 2014 study. The authors surmised that the doctors needed to learn how to talk to groups and suggested that they get some training.

The potential staying power of V-SMAs post COVID?

Once the COVID-19 crisis is over, Medicare is scheduled to no longer provide the same level of reimbursement for virtual sessions as for real sessions. Dr. Mirsky anticipates a great deal of resistance to this change from thousands of physicians and patients who have become comfortable with telehealth, including virtual SMAs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks V-SMAs will continue. “When COVID-19 clears and we can go back to in-person groups, we expect to keep some virtual groups. People have already come to accept and value virtual groups.”

Dr. Wheeler sees virtual groups playing an essential role post COVID-19, when practices have to get back up to speed. “Virtual group visits could make it easier to deal with a large backlog of patients who couldn’t be seen up until now,” she said. “And virtual groups will be the only way to see patients who are still reluctant to meet in a group.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ten patients smiled and waved out on the computer monitor, as Jacob Mirsky, MD, greeted each one, asked them to introduce themselves, and inquired as to how each was doing with their stress reduction tactics.

The attendees of the online session had been patients at in-person group visits at the Massachusetts General Hospital Revere HealthCare Center. But those in-person group sessions, known as shared medical appointments (SMAs), were shut down when COVID-19 arrived.

“Our group patients have been missing the sessions,” said Dr. Mirsky, a general internist who codirects the center’s group visit program. The online sessions, called virtual SMAs (V-SMAs), work well with COVID-19 social distancing.

In the group sessions, Dr. Mirsky reads a standardized message that addresses privacy concerns during the session. For the next 60-90 minutes, “we ask them to talk about what has gone well for them and what they are struggling with,” he said. “Then I answer their questions using materials in a PowerPoint to address key points, such as reducing salt for high blood pressure or interpreting blood sugar levels for diabetes.

“I try to end group sessions with one area of focus,” Dr. Mirsky said. “In the stress reduction group, this could be meditation. In the diabetes group, it could be a discussion on weight loss.” Then the program’s health coach goes over some key concepts on behavior change and invites participants to contact her after the session.

“The nice thing is that these virtual sessions are fully reimbursable by all of our insurers in Massachusetts,” Dr. Mirsky said. Through evaluation and management (E/M) codes, each patient in a group visit is paid the same as a patient in an individual visit with the same level of complexity.

Dr. Mirsky writes a note in the chart about each patient who was in the group session. “This includes information about the specific patient, such as the history and physical, and information about the group meeting,” he said. In the next few months, the center plans to put its other group sessions online – on blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and insomnia.

Attracting doctors who hadn’t done groups before

said Marianne Sumego, MD, director of the Cleveland Clinic’s SMA program, which began 21 years ago.

In this era of COVID-19, group visits have either switched to V-SMAs or halted. However, the COVID-19 crisis has given group visits a second wind. Some doctors who never used SMAs before are now trying out this new mode of patient engagement,

Many of the 100 doctors using SMAs at the Cleveland Clinic have switched over to V-SMAs for now, and the new mode is also attracting colleagues who are new to SMAs, she said.

“When doctors started using telemedicine, virtual group visits started making sense to them,” Dr. Sumego said. “This is a time of a great deal of experimentation in practice design.”

Indeed, V-SMAs have eliminated some problems that had discouraged doctors from trying SMAs, said Amy Wheeler, MD, a general internist who founded the Revere SMA program and codirects it with Dr. Mirsky.

V-SMAs eliminate the need for a large space to hold sessions and reduce the number of staff needed to run sessions, Dr. Wheeler said. “Virtual group visits can actually be easier to use than in-person group visits.”

Dr. Sumego believes small practices in particular will take up V-SMAs because they are easier to run than regular SMAs. “Necessity drives change,” she said. “Across the country everyone is looking at the virtual group model.”

Group visits can help your bottom line

Medicare and many private payers cover group visits. In most cases, they tend to pay the same rate as for an individual office visit. As with telehealth, Medicare and many other payers are temporarily reimbursing for virtual visits at the same rate as for real visits.

Not all payers have a stated policy about covering SMAs, and physicians have to ask. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, for example, has not published any coding rules on SMAs. But in response to a query by the American Academy of Family Physicians, CMS said it would allow use of CPT codes for E/M services for individual patients.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina is one of the few payers with a clearly stated policy on its website. Like Medicare, the insurer accepts E/M codes, and it requires that patients’ attendance must be voluntary; they must be established patients; and the visit must be specific to a disease or condition, although several conditions are allowed.

Dr. Mirsky said his group uses the same E/M level – 99213 – for all of his SMA patients. “Since a regular primary care visit is usually billed at a level 3 or 4, depending on how many topics are covered, we chose level 3 for groups, because the group session deals with just one topic.”

One challenge for billing for SMAs is that most health insurers require patients to provide a copay for each visit, which can discourage patients in groups that meet frequently, says Wayne Dysinger, MD, founder of Lifestyle Medical Solutions, a two-physician primary care practice in Riverside, Calif.

But Dr. Dysinger, who has been using SMAs for 5 years, usually doesn’t have to worry about copays because much of his work is capitated and doesn’t require a copay.

Also, some of Dr. Dysinger’s SMA patients are in direct primary care, in which the patients pay an $18 monthly membership fee. Other practices may charge a flat out-of-pocket fee.

How group visits operate

SMAs are based on the observation that patients with the same condition generally ask their doctor the same questions, and rather than repeat the answers each time, why not provide them to a group?

Dr. Wheeler said trying to be more efficient with her time was the primary reason she became interested in SMAs a dozen years ago. “I was trying to squeeze the advice patients needed into a normal patient visit, and it wasn’t working. When I tried to tell them everything they needed to know, I’d run behind for the rest of my day’s visits.”

She found she was continually repeating the same conversation with patients, but these talks weren’t detailed enough to be effective. “When my weight loss patients came back for the next appointment, they had not made the recommended changes in lifestyle. I started to realize how complicated weight loss was.” So Dr. Wheeler founded the SMA program at the Revere Center.

Doctors enjoy the patient interaction

Some doctors who use SMAs talk about how connected they feel with their patients. “For me, the group sessions are the most gratifying part of the week,” Dr. Dysinger says. “I like to see the patients interacting with me and with each other, and watch their health behavior change over time.”

“These groups have a great deal of energy,” he said. “They have a kind of vulnerability that is very raw, very human. People make commitments to meet goals. Will they meet them or not?”

Dr. Dysinger’s enthusiasm has been echoed by other doctors. In a study of older patients, physicians who used SMAs were more satisfied with care than physicians who relied on standard one-to-one interactions. In another study, the researchers surmised that, in SMAs, doctors learn from their patients how they can better meet their needs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks SMAs are widely applicable in primary care. He estimates that 80%-85% of appointments at a primary care practice involve chronic diseases, and this type of patient is a good fit for group visits. SMAs typically treat patients with diabetes, asthma, arthritis, and obesity.

Dr. Sumego said SMAs are used for specialty care at Cleveland Clinic, such as to help patients before and after bariatric surgery. SMAs have also been used to treat patients with ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, cancer, HIV, menopause, insomnia, and stress, according to one report.

Dr. Dysinger, who runs a small practice, organizes his group sessions somewhat differently. He doesn’t organize his groups around conditions like diabetes, but instead his groups focus on four “pillars” of lifestyle medicine: nourishment, movement, resilience (involving sleep and stress), and connectedness.

Why patients like group visits

Feeling part of a whole is a major draw for many patients. “Patients seem to like committing to something bigger than just themselves,” Dr. Wheeler said. “They enjoy the sense of community that groups have, the joy of supporting one another.”

“It’s feeling that you’re not alone,” Dr. Mirsky said. “When a patient struggling with diabetes hears how hard it is for another patient, it validates their experience and gives them someone to connect with. There is a positive peer pressure.”

Many programs, including Dr. Wheeler’s and Dr. Mirsky’s in Boston, allow patients to drop in and out of sessions, rather than attending one course all the way through. But even under this format, Dr. Wheeler said that patients often tend to stick together. “At the end of a session, one patient asks another: ‘Which session do you want to go to next?’ ” she said.

Patients also learn from each other in SMAs. Patients exchange experiences and share advice they may not have had the chance to get during an individual visit.

The group dynamic can make it easier for some patients to reveal sensitive information, said Dr. Dysinger. “In these groups, people feel free to talk about their bowel movements, or about having to deal with the influence of a parent on their lives,” Dr. Dysinger said. “The sessions can have the feel of an [Alcoholics Anonymous] meeting, but they’re firmly grounded in medicine.”

Potential downsides of virtual group visits

SMAs and VSMAs may not work for every practice. Some small practices may not have enough patients to organize a group visit around a particular condition – even a common one like diabetes. In a presentation before the Society of General Internal Medicine, a physician from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, warned that it may be difficult for a practice to fill diabetes group visits every year.

Additionally, some patients don’t want to talk about personal matters in a group. “They may not want to reveal certain things about themselves,” Dr. Mirsky said. “So I tell the group that if there is anything that anyone wants to talk about in private, I’m available.”

Another drawback of SMAs is that more experienced patients may have to slog through information they already know, which is a particular problem when patients can drop in and out of sessions. Dr. Mirsky noted that “what often ends up happening is that the experienced participant helps the newcomer.”

Finally, confidentially is a big concern in a group session. “In a one-on-one visit, you can go into details about the patient’s health, and even bring up an entry in the chart,” Dr. Wheeler said. “But in a group visit, you can’t raise any personal details about a patient unless the patient brings it up first.”

SMA patients sign confidentiality agreements in which they agree not to talk about other patients outside the session. Ensuring confidentiality becomes more complicated in virtual group visits, because someone located in the room near a participant could overhear the conversation. For this reason, patients in V-SMAs are advised to use headphones or, at a minimum, close the door to the room they are in.

To address privacy concerns, Zoom encrypts its data, but some privacy breeches have been reported, and a U.S. senator has been looking into Zoom’s privacy vulnerabilities.

Transferring groups to virtual groups

It took the COVID-19 crisis for most doctors to take up virtual SMAs. Dr. Sumego said that the Cleveland Clinic started virtual SMAs more than a year ago, but most other groups operating SMAs were apparently not providing them virtually before COVID-19 started.

Dr. Dysinger said he tried virtual SMAs in 2017 but dropped them because the technology – using Zoom – was challenging at the time, and his staff and most patients were resistant. “Only three to five people were attending the virtual sessions, and the meetings took place in the evening, which was hard on the staff.”

“When COVID-19 first appeared, our initial response was to try to keep the in-person group and add social distancing to it, but that wasn’t workable, so very quickly we shifted to Zoom meetings,” Dr. Dysinger said. “We had experience with Zoom already, and the Zoom technology had improved and was easier to use. COVID-19 forced it all forward.”

Are V-SMAs effective? While there have been many studies showing the effectiveness of in-person SMAs, there have been very few on V-SMAs. One 2018 study of obesity patients found that those attending in-person SMAs lost somewhat more weight than those in V-SMAs.

As with telemedicine, some patients have trouble with the technology of V-SMAs. Dr. Dysinger said 5%-10% of his SMA patients don’t make the switch over to V-SMAs – mainly because of problems in adapting to the technology – but the rest are happy. “We’re averaging 10 people per meeting, and as many as 20.”

Getting comfortable with group visits

Dealing with group visits takes a very different mindset than what doctors normally have, Dr. Wheeler said. “It took me 6-8 months to feel comfortable enough with group sessions to do them myself,” she recalled. “This was a very different way to practice, compared to the one-on-one care I was trained to give patients. Others may find the transition easier, though.

“Doctors are used to being in control of the patient visit, but the exchange in a group visit is more fluid,” Dr. Wheeler said. “Patients offer their own opinions, and this sends the discussion off on a tangent that is often quite useful. As doctors, we have to learn when to let these tangents continue, and know when the discussion might have to be brought back to the theme at hand. Often it’s better not to intercede.”

Do doctors need training to conduct SMAs? Patients in group visits reported worse communication with physicians than those in individual visits, according to a 2014 study. The authors surmised that the doctors needed to learn how to talk to groups and suggested that they get some training.

The potential staying power of V-SMAs post COVID?

Once the COVID-19 crisis is over, Medicare is scheduled to no longer provide the same level of reimbursement for virtual sessions as for real sessions. Dr. Mirsky anticipates a great deal of resistance to this change from thousands of physicians and patients who have become comfortable with telehealth, including virtual SMAs.

Dr. Dysinger thinks V-SMAs will continue. “When COVID-19 clears and we can go back to in-person groups, we expect to keep some virtual groups. People have already come to accept and value virtual groups.”

Dr. Wheeler sees virtual groups playing an essential role post COVID-19, when practices have to get back up to speed. “Virtual group visits could make it easier to deal with a large backlog of patients who couldn’t be seen up until now,” she said. “And virtual groups will be the only way to see patients who are still reluctant to meet in a group.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who refuse to wear masks: Responses that won’t get you sued

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?

Someone who is injured in a public place may sue the owner for negligence if the owner knew or should have known of a danger and didn’t do anything about it. For example, individuals have sued grocery stores successfully after they slipped on a banana peel and fell. If, say, the banana peel was black, that indicates that it had been there for a while, and judges have found that the store management should have known about it and removed it.

Compare the banana peel scenario with the scenario where most news outlets and health departments are telling people, every day, to wear masks while in indoor public spaces, yet owners of a medical practice or facility allow individuals who are not wearing masks to sit in their waiting room. If an individual who was also in the waiting room with the unmasked individual develops COVID-19 2 days later, the ill individual may sue the medical practice for negligence for not removing the unmasked individual.

What about the individual’s responsibility to move away from the person not wearing a mask? That is the aspect of this scenario that attorneys and experts could argue about, for days, in a court case. But to go back to the banana peel case, one could argue that a customer in a grocery store should be looking out for banana peels on the floor and avoid them, yet courts have assigned liability to grocery stores when customers slip and fall.

Let’s review the four elements of negligence which a plaintiff would need to prove:

- Duty: Obligation of one person to another

- Breach: Improper act or omission, in the context of proper behavior to avoid imposing undue risks of harm to other persons and their property

- Damage

- Causation: That the act or omission caused the harm

Those who run medical offices and facilities have a duty to provide reasonably safe public spaces. Unmasked individuals are a risk to others nearby, so the “breach” element is satisfied if a practice fails to impose safety measures. Causation could be proven, or at least inferred, if contact tracing of an individual with COVID-19 showed that the only contact likely to have exposed the ill individual to the virus was an unmasked individual in a medical practice’s waiting room, especially if the unmasked individual was COVID-19 positive before, during, or shortly after the visit to the practice.

What about patient abandonment?

“Patient abandonment” is the legal term for terminating the physician-patient relationship in such a manner that the patient is denied necessary medical care. It is a form of negligence.

Refusing to see a patient unless the patient wears a mask is not denying care, in this attorney’s view, but rather establishing reasonable conditions for getting care. The patient simply needs to put on a mask.

What about the patient who refuses to wear a mask for medical reasons? There are exceptions in most of the governors’ orders for individuals with medical conditions that preclude covering nose and mouth with a mask. A medical office is the perfect place to test an individual’s ability or inability to breathe well while wearing a mask. “Put the mask on and we’ll see how you do” is a reasonable response. Monitor the patient visually and apply a pulse oximeter with mask off and mask on.

One physician recently wrote about measuring her own oxygen levels while wearing four different masks for 5 minutes each, with no change in breathing.

Editor’s note: Read more about mask exemptions in a Medscape interview with pulmonologist Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association.

What are some practical tips?

Assuming that a patient is not in acute distress, options in this scenario include:

- Send the patient home and offer a return visit if masked or when the pandemic is over.

- Offer a telehealth visit, with the patient at home.

What if the unmasked person is not a patient but the companion of a patient? What if the individual refusing to wear a mask is an employee? In neither of these two hypotheticals is there a basis for legal action against a practice whose policy requires that everyone wear masks on the premises.

A companion who arrives without a mask should leave the office. An employee who refuses to mask up could be sent home. If the employee has a disability covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, then the practice may need to make reasonable accommodations so that the employee works in a room alone if unable to work from home.

Those who manage medical practices should check the websites of the state health department and medical societies at least weekly, to see whether the agencies have issued guidance. For example, the Texas Medical Association has issued limited guidance.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician leadership: Racial disparities and racism. Where do we go from here?

The destructive toll COVID-19 has caused worldwide is devastating. In the United States, the disproportionate deaths of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people due to structural racism, amplified by economic adversity, is unacceptable. Meanwhile, the continued murder of Black people by those sworn to protect the public is abhorrent and can no longer be ignored. Black lives matter. These crises have rightly gripped our attention, and should galvanize physicians individually and collectively to use our privileged voices and relative power for justice. We must strive for engaged, passionate, and innovative leadership deliberately aimed toward antiracism and equity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the vast inequities in our country. It has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities. It also has demonstrated clearly that we are all connected—one large community, interdependent yet rife with differential power, privilege, and oppression. We must address these racial disparities—not only in the name of justice and good health for all but also because it is a moral and ethical imperative for us as physicians—and SARS-CoV-2 clearly shows us that it is in the best interest of everyone to do so.

First step: A deep dive look at systemic racism

What is first needed is an examination and acknowledgement by medicine and health care at large of the deeply entrenched roots of systemic and institutional racism in our profession and care systems, and their disproportionate and unjust impact on the health and livelihood of communities of color. The COVID-19 pandemic is only a recent example that highlights the perpetuation of a system that harms people of color. Racism, sexism, gender discrimination, economic and social injustice, religious persecution, and violence against women and children are age-old. We have yet to see health care institutions implement system-wide intersectional and antiracist practices to address them. Mandatory implicit bias training, policies for inclusion and diversity, and position statements are necessary first steps; however, they are not a panacea. They are insufficient to create the bold changes we need. The time for words has long passed. It is time to listen, to hear the cries of anguish and outrage, to examine our privileged position, to embrace change and discomfort, and most importantly to act, and to lead in dismantling the structures around us that perpetuate racial inequity.

How can we, as physicians and leaders, join in action and make an impact?

Dr. Camara Jones, past president of the American Public Health Association, describes 3 levels of racism:

- structural or systemic

- individual or personally mediated

- internalized.

Interventions at each level are important if we are to promote equity in health and health care. This framework can help us think about the following strategic initiatives.

Continue to: 1. Commit to becoming an antiracist and engage in independent study...

1. Commit to becoming antiracist and engage in independent study. This is an important first step as it will form the foundations for interventions—one cannot facilitate change without understanding the matter at hand. This step also may be the most personally challenging step forcing all of us to wrestle with discomfort, sadness, fear, guilt, and a host of other emotional responses. Remember that great change has never been born out of comfort, and the discomfort physicians may experience while unlearning racism and learning antiracism pales in comparison to what communities of color experience daily. We must actively work to unlearn the racist and anti-Black culture that is so deeply woven into every aspect of our existence.

Learn the history that was not given to us as kids in school. Read the brilliant literary works of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx artists and scholars on dismantling racism. Expand our vocabulary and knowledge of core concepts in racism, racial justice, and equity. Examine and reflect on our day-to-day practices. Be vocal in our commitment to antiracism—the time has passed for staying silent. If you are white, facilitate conversations about race with your white colleagues; the inherent power of racism relegates it to an issue that can never be on the table, but it is time to dismantle that power. Learn what acts of meaningful and intentional alliances are and when we need to give up power or privilege to a person of color. We also need to recognize that we as physicians, while leaders in many spaces, are not leaders in the powerful racial justice grassroots movements. We should learn from these movements, follow their lead, and use our privilege to uplift racial justice in our settings.

2. Embrace the current complexities with empathy and humility, finding ways to exercise our civic responsibility to the public with compassion. During the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen the devastation that social isolation, job loss, and illness can create. Suddenly those who could never have imagined themselves without food are waiting hours in their cars for food bank donations or are finding empty shelves in stores. Those who were not safe at home were suddenly imprisoned indefinitely in unsafe situations. Those who were comfortable, well-insured, and healthy are facing an invisible health threat, insecurity, fear, anxiety, and loss. Additionally, our civic institutions are failing. Those of us who always took our right to vote for granted are being forced to stand in hours’-long lines to exercise that right; while those who have been systematically disenfranchised are enduring even greater threats to their constitutional right to exercise their political power, disallowing them to speak for their families and communities and to vote for the justice they deserve. This may be an opportunity to stop blaming victims and recognize the toll that structural and systemic contributions to inequity have created over generations.

3. Meaningfully engage with and advocate for patients. In health and health care, we must begin to engage with the communities we serve and truly listen to their needs, desires, and barriers to care, and respond accordingly. Policies that try to address the social determinants of health without that engagement, and without the acknowledgement of the structural issues that cause them, however well-intentioned, are unlikely to accomplish their goals. We need to advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens. To execute this, we need to:

- ask why clinic and hospital practices are built the way they are and how to make them more reflexive and responsive to individual patient’s needs

- examine what the disproportionate impacts might be on different groups of patients from a systems-level

- be ready to dismantle and/or rebuild something that is exacerbating disparate outcomes and experiences

- advocate for change that is built upon the narratives of patients and their communities.

We should include patients in the creation of hospital policies and guidelines in order to shift power toward them and to be transparent about how the system operates in order to facilitate trust and collaboration that centers patients and communities in the systems created to serve them.

Continue to: 4. Intentionally repair and build trust...

4. Intentionally repair and build trust. To create a safe environment, we must repair what we have broken and earn the trust of communities by uplifting their voices and redistributing our power to them in changing the systems and structures that have, for generations, kept Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people oppressed. Building trust requires first owning our histories of colonization, genocide, and slavery—now turned mass incarceration, debasement, and exploitation—that has existed for centuries. We as physicians need to do an honest examination of how we have eroded the trust of the very communities we care for since our profession’s creation. We need to acknowledge, as a white-dominant profession, the medical experimentation on and exploitation of Black and Brown bodies, and how this formed the foundation for a very valid deep distrust and fear of the medical establishment. We need to recognize how our inherent racial biases continue to feed this distrust, like when we don’t treat patients’ pain adequately or make them feel like we believe and listen to their needs and concerns. We must acknowledge our complicity in perpetuating the racial inequities in health, again highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Increase Black, Indigenous, and Latinx representation in physician and other health care professions’ workforce. Racism impacts not only patients but also our colleagues of color. The lack of racial diversity is a symptom of racism and a representation of the continued exclusion and devaluing of physicians of color. We must recognize this legacy of exclusion and facilitate intentional recruitment, retention, inclusion, and belonging of people of color into our workforce. Tokenism, the act of symbolically including one or few people from underrepresented groups, has been a weapon used by our workforce against physicians of color, resulting in isolation, “othering,” demoralization, and other deleterious impacts. We need to reverse this history and diversify our training programs and workforce to ensure justice in our own community.

6. Design multifaceted interventions. Multilevel problems require multilevel solutions. Interventions targeted solely at one level, while helpful, are unlikely to result in the larger scale changes our society needs to implement if we are to eradicate the impact of racism on health. We have long known that it is not just “preexisting conditions” or “poor” individual behaviors that lead to negative and disparate health outcomes—these are impacted by social and structural determinants much larger and more deleterious than that. It is critically important that we allocate and redistribute resources to create safe and affordable housing; childcare and preschool facilities; healthy, available, and affordable food; equitable and affordable educational opportunities; and a clean environment to support the health of all communities—not only those with the highest tax base. It is imperative that we strive to understand the lives of our fellow human beings who have been subjected to intergenerational social injustices and oppressions that have continued to place them at the margins of society. We need to center the lived experiences of communities of color in the design of multilevel interventions, especially Black and Indigenous communities. While we as physicians cannot individually impact education, economic, or food/environment systems, we can use our power to advocate for providing resources for the patients we care for and can create strategies within the health care system to address these needs in order to achieve optimal health. Robust and equitable social structures are the foundations for health, and ensuring equitable access to them is critical to reducing disparities.

Commit to lead

We must commit to unlearning our internalized racism, rebuilding relationships with communities of color, and engaging in antiracist practices. As a profession dedicated to healing, we have an obligation to be leaders in advocating for these changes, and dismantling the inequitable structure of our health care system.

Our challenge now is to articulate solutions. While antiracism should be informed by the lived experiences of communities of color, the work of antiracism is not their responsibility. In fact, it is the responsibility of our white-dominated systems and institutions to change.

There are some solutions that are easier to enumerate because they have easily measurable outcomes or activities, such as:

- collecting data transparently

- identifying inequities in access, treatment, and care

- conducting rigorous root cause analysis of those barriers to care

- increasing diverse racial and gender representation on decision-making bodies, from board rooms to committees, from leadership teams to research participants

- redistribute power by paving the way for underrepresented colleagues to participate in clinical, administrative, educational, executive, and health policy spaces

- mentoring new leaders who come from marginalized communities.

Every patient deserves our expertise and access to high-quality care. We should review our patient panels to ensure we are taking steps personally to be just and eliminate disparities, and we should monitor the results of those efforts.

Continue to: Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”...

Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”

There are other solutions, perhaps those that would be more effective on a larger scale, which may be harder to measure using our traditional ways of inquiry or measurement. Solutions that may create discomfort, anger, or fear for those who have held their power or positions for a long time. We need to begin to engage in developing, cultivating, and valuing innovative strategies that produce equally valid knowledge, evidence, and solutions without engaging in a randomized controlled trial. We need to reinvent the way inquiry, investigation, and implementation are done, and utilize novel, justice-informed strategies that include real-world evidence to produce results that are applicable to all (not just those willing to participate in sponsored trials). Only then will we be able to provide equitable health outcomes for all.