User login

Pandemic poses new challenges for rural doctors

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

Revamping mentorship in medicine

Why the current system fails underrepresented physicians — and tips to improve it

Mentoring is often promoted as an organizational practice to promote diversity and inclusion. New or established group members who want to further their careers look for a mentor to guide them toward success within a system by amplifying their strengths and accomplishments and defending and promoting them when necessary. But how can mentoring work if there isn’t a mentor?

For underrepresented groups or marginalized physicians, it too often looks as if there are no mentors who understand the struggles of being a racial or ethnic minority group member or mentors who are even cognizant of those struggles. Mentoring is a practice that occurs within the overarching systems of practice groups, academic departments, hospitals, medicine, and society at large. These systems frequently carry the legacies of bias, discrimination, and exclusion. The mentoring itself that takes place within a biased system risks perpetuating institutional bias, exclusion, or a sense of unworthiness in the mentee. It is stressful for any person with a minority background or even a minority interest to feel that there’s no one to emulate in their immediate working environment. When that is the case, a natural question follows: “Do I even belong here?”

Before departments and psychiatric practices turn to old, surface-level solutions like using mentorship to appear more welcoming to underrepresented groups, leaders must explicitly evaluate their track record of mentorship within their system and determine whether mentorship has been used to protect the status quo or move the culture forward. As mentorship is inherently an imbalanced relationship, there must be department- or group-level reflection about the diversity of mentors and also their examinations of mentors’ own preconceived notions of who will make a “good” mentee.

At the most basic level, leaders can examine whether there are gaps in who is mentored and who is not. Other parts of mentoring relationships should also be examined: a) How can mentoring happen if there is a dearth of underrepresented groups in the department? b) What type of mentoring style is favored? Do departments/groups look for a natural fit between mentor and mentee or are they matched based on interests, ideals, and goals? and c) How is the worthiness for mentorship determined?

One example is the fraught process of evaluating “worthiness” among residents. Prospective mentors frequently divide trainees unofficially into a top-tier candidates, middle-tier performers who may be overlooked, and a bottom tier who are avoided when it comes to mentorship. Because this division is informal and usually based on extremely early perceptions of trainees’ aptitude and openness, the process can be subject to an individual mentor’s conscious and unconscious bias, which then plays a large role in perpetuating systemic racism. When it comes to these informal but often rigid divisions, it can be hard to fall from the top when mentees are buoyed by good will, frequent opportunities to shine, and the mentor’s reputation. Likewise,

Below are three recommendations to consider for improving mentorship within departments:

1) Consider opportunities for senior mentors and potential mentees to interact with one another outside of assigned duties so that some mentorship relationships can be formed organically.

2) Review when mentorship relationships have been ineffective or unsuccessful versus productive and useful for both participants.

3) Increase opportunities for adjunct or former faculty who remain connected to the institution to also be mentors. This approach would open up more possibilities and could increase the diversity of available mentors.

If mentorship is to be part of the armamentarium for promoting equity within academia and workplaces alike, it must be examined and changed to meet the new reality.

Dr. Posada is assistant clinical professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University in Washington. She also serves as staff physician at George Washington Medical Faculty Associates, also in Washington. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Forrester is consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship training director at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Why the current system fails underrepresented physicians — and tips to improve it

Why the current system fails underrepresented physicians — and tips to improve it

Mentoring is often promoted as an organizational practice to promote diversity and inclusion. New or established group members who want to further their careers look for a mentor to guide them toward success within a system by amplifying their strengths and accomplishments and defending and promoting them when necessary. But how can mentoring work if there isn’t a mentor?

For underrepresented groups or marginalized physicians, it too often looks as if there are no mentors who understand the struggles of being a racial or ethnic minority group member or mentors who are even cognizant of those struggles. Mentoring is a practice that occurs within the overarching systems of practice groups, academic departments, hospitals, medicine, and society at large. These systems frequently carry the legacies of bias, discrimination, and exclusion. The mentoring itself that takes place within a biased system risks perpetuating institutional bias, exclusion, or a sense of unworthiness in the mentee. It is stressful for any person with a minority background or even a minority interest to feel that there’s no one to emulate in their immediate working environment. When that is the case, a natural question follows: “Do I even belong here?”

Before departments and psychiatric practices turn to old, surface-level solutions like using mentorship to appear more welcoming to underrepresented groups, leaders must explicitly evaluate their track record of mentorship within their system and determine whether mentorship has been used to protect the status quo or move the culture forward. As mentorship is inherently an imbalanced relationship, there must be department- or group-level reflection about the diversity of mentors and also their examinations of mentors’ own preconceived notions of who will make a “good” mentee.

At the most basic level, leaders can examine whether there are gaps in who is mentored and who is not. Other parts of mentoring relationships should also be examined: a) How can mentoring happen if there is a dearth of underrepresented groups in the department? b) What type of mentoring style is favored? Do departments/groups look for a natural fit between mentor and mentee or are they matched based on interests, ideals, and goals? and c) How is the worthiness for mentorship determined?

One example is the fraught process of evaluating “worthiness” among residents. Prospective mentors frequently divide trainees unofficially into a top-tier candidates, middle-tier performers who may be overlooked, and a bottom tier who are avoided when it comes to mentorship. Because this division is informal and usually based on extremely early perceptions of trainees’ aptitude and openness, the process can be subject to an individual mentor’s conscious and unconscious bias, which then plays a large role in perpetuating systemic racism. When it comes to these informal but often rigid divisions, it can be hard to fall from the top when mentees are buoyed by good will, frequent opportunities to shine, and the mentor’s reputation. Likewise,

Below are three recommendations to consider for improving mentorship within departments:

1) Consider opportunities for senior mentors and potential mentees to interact with one another outside of assigned duties so that some mentorship relationships can be formed organically.

2) Review when mentorship relationships have been ineffective or unsuccessful versus productive and useful for both participants.

3) Increase opportunities for adjunct or former faculty who remain connected to the institution to also be mentors. This approach would open up more possibilities and could increase the diversity of available mentors.

If mentorship is to be part of the armamentarium for promoting equity within academia and workplaces alike, it must be examined and changed to meet the new reality.

Dr. Posada is assistant clinical professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University in Washington. She also serves as staff physician at George Washington Medical Faculty Associates, also in Washington. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Forrester is consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship training director at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Mentoring is often promoted as an organizational practice to promote diversity and inclusion. New or established group members who want to further their careers look for a mentor to guide them toward success within a system by amplifying their strengths and accomplishments and defending and promoting them when necessary. But how can mentoring work if there isn’t a mentor?

For underrepresented groups or marginalized physicians, it too often looks as if there are no mentors who understand the struggles of being a racial or ethnic minority group member or mentors who are even cognizant of those struggles. Mentoring is a practice that occurs within the overarching systems of practice groups, academic departments, hospitals, medicine, and society at large. These systems frequently carry the legacies of bias, discrimination, and exclusion. The mentoring itself that takes place within a biased system risks perpetuating institutional bias, exclusion, or a sense of unworthiness in the mentee. It is stressful for any person with a minority background or even a minority interest to feel that there’s no one to emulate in their immediate working environment. When that is the case, a natural question follows: “Do I even belong here?”

Before departments and psychiatric practices turn to old, surface-level solutions like using mentorship to appear more welcoming to underrepresented groups, leaders must explicitly evaluate their track record of mentorship within their system and determine whether mentorship has been used to protect the status quo or move the culture forward. As mentorship is inherently an imbalanced relationship, there must be department- or group-level reflection about the diversity of mentors and also their examinations of mentors’ own preconceived notions of who will make a “good” mentee.

At the most basic level, leaders can examine whether there are gaps in who is mentored and who is not. Other parts of mentoring relationships should also be examined: a) How can mentoring happen if there is a dearth of underrepresented groups in the department? b) What type of mentoring style is favored? Do departments/groups look for a natural fit between mentor and mentee or are they matched based on interests, ideals, and goals? and c) How is the worthiness for mentorship determined?

One example is the fraught process of evaluating “worthiness” among residents. Prospective mentors frequently divide trainees unofficially into a top-tier candidates, middle-tier performers who may be overlooked, and a bottom tier who are avoided when it comes to mentorship. Because this division is informal and usually based on extremely early perceptions of trainees’ aptitude and openness, the process can be subject to an individual mentor’s conscious and unconscious bias, which then plays a large role in perpetuating systemic racism. When it comes to these informal but often rigid divisions, it can be hard to fall from the top when mentees are buoyed by good will, frequent opportunities to shine, and the mentor’s reputation. Likewise,

Below are three recommendations to consider for improving mentorship within departments:

1) Consider opportunities for senior mentors and potential mentees to interact with one another outside of assigned duties so that some mentorship relationships can be formed organically.

2) Review when mentorship relationships have been ineffective or unsuccessful versus productive and useful for both participants.

3) Increase opportunities for adjunct or former faculty who remain connected to the institution to also be mentors. This approach would open up more possibilities and could increase the diversity of available mentors.

If mentorship is to be part of the armamentarium for promoting equity within academia and workplaces alike, it must be examined and changed to meet the new reality.

Dr. Posada is assistant clinical professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University in Washington. She also serves as staff physician at George Washington Medical Faculty Associates, also in Washington. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Forrester is consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship training director at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Smart health devices – promises and pitfalls

What needs to be done before the data deluge hits the office

Hurricane Sally recently crossed the Gulf of Mexico and landed with torrential rainfalls along the Alabama coast. A little rainfall is important for crops; too much leads to devastation. As physicians, we need data in order to help manage patients’ illnesses and to help to keep them healthy. Our fear though is that too much data provided too quickly may have the opposite effect.

Personal monitoring devices

When I bought my first Fitbit 7 years ago, I was enamored with the technology. The Fitbit was little more than a step tracker, yet I proudly wore its black rubber strap on my wrist. It was my first foray into wearable technology, and it felt quite empowering to have an objective way to track my fitness beyond just using my bathroom scale. Now less than a decade later, that Fitbit looks archaic in comparison with the wrist-top technology currently available.

As I write this, the world’s largest technology company is in the process of releasing its sixth-generation Apple Watch. In addition to acting as a smartphone, this new device, which is barely larger than a postage stamp, offers GPS-based movement tracking, the ability to detect falls, continuous heart rate monitoring, a built-in EKG capable of diagnosing atrial fibrillation, and an oxygen saturation sensor. These features weren’t added thoughtlessly. Apple is marketing this as a health-focused device, with their primary advertising campaign claiming that “the future of health is on your wrist,” and they aren’t the only company making this play.

Along with Apple, Samsung, Withings, Fitbit, and other companies continue to bring products to market that monitor our activity and provide new insights into our health. Typically linked to smartphone-based apps, these devices record all of their measurements for later review, while software helps interpret the findings to make them actionable. From heart rate tracking to sleep analysis, these options now provide access to volumes of data that promise to improve our wellness and change our lives. Of course, those promises will only be fulfilled if our behavior is altered as a consequence of having more detailed information. Whether that will happen remains to be seen.

Health system–linked devices

Major advancements in medical monitoring technology are now enabling physicians to get much deeper insight into their patients’ health status. Internet-connected scales, blood pressure cuffs, and exercise equipment offer the ability to upload information into patient portals and integrate that information into EHRs. New devices provide access to information that previously was impossible to obtain. For example, wearable continuous blood glucose monitors, such as the FreeStyle Libre or DexCom’s G6, allow patients and physicians to follow blood sugar readings 24 hours a day. This provides unprecedented awareness of diabetes control and relieves the pain and inconvenience of finger sticks and blood draws. It also aids with compliance because patients don’t need to remember to check their sugar levels on a schedule.

Other compliance-boosting breakthroughs, such as Bluetooth-enabled asthma inhalers and cellular-connected continuous positive airway pressure machines, assist patients with managing chronic respiratory conditions. Many companies are developing technologies to manage acute conditions as well. One such company, an on-demand telemedicine provider called TytoCare, has developed a $299 suite of instruments that includes a digital stethoscope, thermometer, and camera-based otoscope. In concert with a virtual visit, their providers can remotely use these tools to examine and assess sick individuals. This virtual “laying on of hands” may have sounded like science fiction and likely would have been rejected by patients just a few years ago. Now it is becoming commonplace and will soon be an expectation of many seeking care.

But if we are to be successful, everyone must acknowledge that this revolution in health care brings many challenges along with it. One of those is the deluge of data that connected devices provide.

Information overload

There is such a thing as “too much of a good thing.” Described by journalist David Shenk as “data smog” in his 1997 book of the same name, the idea is clear: There is only so much information we can assimilate.

Even after years of using EHRs and with government-implemented incentives that promote “meaningful use,” physicians are still struggling with EHRs. Additionally, many have expressed frustration with the connectedness that EHRs provide and lament their inability to ever really “leave the office.” As more and more data become available to physicians, the challenge of how to assimilate and act on those data will continue to grow. The addition of patient-provided health statistics will only make information overload worse, with clinicians will feeling an ever-growing burden to know, understand, and act on this information.

Unless we develop systems to sort, filter, and prioritize the flow of information, there is potential for liability from not acting on the amount of virtual information doctors receive. This new risk for already fatigued and overburdened physicians combined with an increase in the amount of virtual information at doctors’ fingertips may lead to the value of patient data being lost.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

What needs to be done before the data deluge hits the office

What needs to be done before the data deluge hits the office

Hurricane Sally recently crossed the Gulf of Mexico and landed with torrential rainfalls along the Alabama coast. A little rainfall is important for crops; too much leads to devastation. As physicians, we need data in order to help manage patients’ illnesses and to help to keep them healthy. Our fear though is that too much data provided too quickly may have the opposite effect.

Personal monitoring devices

When I bought my first Fitbit 7 years ago, I was enamored with the technology. The Fitbit was little more than a step tracker, yet I proudly wore its black rubber strap on my wrist. It was my first foray into wearable technology, and it felt quite empowering to have an objective way to track my fitness beyond just using my bathroom scale. Now less than a decade later, that Fitbit looks archaic in comparison with the wrist-top technology currently available.

As I write this, the world’s largest technology company is in the process of releasing its sixth-generation Apple Watch. In addition to acting as a smartphone, this new device, which is barely larger than a postage stamp, offers GPS-based movement tracking, the ability to detect falls, continuous heart rate monitoring, a built-in EKG capable of diagnosing atrial fibrillation, and an oxygen saturation sensor. These features weren’t added thoughtlessly. Apple is marketing this as a health-focused device, with their primary advertising campaign claiming that “the future of health is on your wrist,” and they aren’t the only company making this play.

Along with Apple, Samsung, Withings, Fitbit, and other companies continue to bring products to market that monitor our activity and provide new insights into our health. Typically linked to smartphone-based apps, these devices record all of their measurements for later review, while software helps interpret the findings to make them actionable. From heart rate tracking to sleep analysis, these options now provide access to volumes of data that promise to improve our wellness and change our lives. Of course, those promises will only be fulfilled if our behavior is altered as a consequence of having more detailed information. Whether that will happen remains to be seen.

Health system–linked devices

Major advancements in medical monitoring technology are now enabling physicians to get much deeper insight into their patients’ health status. Internet-connected scales, blood pressure cuffs, and exercise equipment offer the ability to upload information into patient portals and integrate that information into EHRs. New devices provide access to information that previously was impossible to obtain. For example, wearable continuous blood glucose monitors, such as the FreeStyle Libre or DexCom’s G6, allow patients and physicians to follow blood sugar readings 24 hours a day. This provides unprecedented awareness of diabetes control and relieves the pain and inconvenience of finger sticks and blood draws. It also aids with compliance because patients don’t need to remember to check their sugar levels on a schedule.

Other compliance-boosting breakthroughs, such as Bluetooth-enabled asthma inhalers and cellular-connected continuous positive airway pressure machines, assist patients with managing chronic respiratory conditions. Many companies are developing technologies to manage acute conditions as well. One such company, an on-demand telemedicine provider called TytoCare, has developed a $299 suite of instruments that includes a digital stethoscope, thermometer, and camera-based otoscope. In concert with a virtual visit, their providers can remotely use these tools to examine and assess sick individuals. This virtual “laying on of hands” may have sounded like science fiction and likely would have been rejected by patients just a few years ago. Now it is becoming commonplace and will soon be an expectation of many seeking care.

But if we are to be successful, everyone must acknowledge that this revolution in health care brings many challenges along with it. One of those is the deluge of data that connected devices provide.

Information overload

There is such a thing as “too much of a good thing.” Described by journalist David Shenk as “data smog” in his 1997 book of the same name, the idea is clear: There is only so much information we can assimilate.

Even after years of using EHRs and with government-implemented incentives that promote “meaningful use,” physicians are still struggling with EHRs. Additionally, many have expressed frustration with the connectedness that EHRs provide and lament their inability to ever really “leave the office.” As more and more data become available to physicians, the challenge of how to assimilate and act on those data will continue to grow. The addition of patient-provided health statistics will only make information overload worse, with clinicians will feeling an ever-growing burden to know, understand, and act on this information.

Unless we develop systems to sort, filter, and prioritize the flow of information, there is potential for liability from not acting on the amount of virtual information doctors receive. This new risk for already fatigued and overburdened physicians combined with an increase in the amount of virtual information at doctors’ fingertips may lead to the value of patient data being lost.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Hurricane Sally recently crossed the Gulf of Mexico and landed with torrential rainfalls along the Alabama coast. A little rainfall is important for crops; too much leads to devastation. As physicians, we need data in order to help manage patients’ illnesses and to help to keep them healthy. Our fear though is that too much data provided too quickly may have the opposite effect.

Personal monitoring devices

When I bought my first Fitbit 7 years ago, I was enamored with the technology. The Fitbit was little more than a step tracker, yet I proudly wore its black rubber strap on my wrist. It was my first foray into wearable technology, and it felt quite empowering to have an objective way to track my fitness beyond just using my bathroom scale. Now less than a decade later, that Fitbit looks archaic in comparison with the wrist-top technology currently available.

As I write this, the world’s largest technology company is in the process of releasing its sixth-generation Apple Watch. In addition to acting as a smartphone, this new device, which is barely larger than a postage stamp, offers GPS-based movement tracking, the ability to detect falls, continuous heart rate monitoring, a built-in EKG capable of diagnosing atrial fibrillation, and an oxygen saturation sensor. These features weren’t added thoughtlessly. Apple is marketing this as a health-focused device, with their primary advertising campaign claiming that “the future of health is on your wrist,” and they aren’t the only company making this play.

Along with Apple, Samsung, Withings, Fitbit, and other companies continue to bring products to market that monitor our activity and provide new insights into our health. Typically linked to smartphone-based apps, these devices record all of their measurements for later review, while software helps interpret the findings to make them actionable. From heart rate tracking to sleep analysis, these options now provide access to volumes of data that promise to improve our wellness and change our lives. Of course, those promises will only be fulfilled if our behavior is altered as a consequence of having more detailed information. Whether that will happen remains to be seen.

Health system–linked devices

Major advancements in medical monitoring technology are now enabling physicians to get much deeper insight into their patients’ health status. Internet-connected scales, blood pressure cuffs, and exercise equipment offer the ability to upload information into patient portals and integrate that information into EHRs. New devices provide access to information that previously was impossible to obtain. For example, wearable continuous blood glucose monitors, such as the FreeStyle Libre or DexCom’s G6, allow patients and physicians to follow blood sugar readings 24 hours a day. This provides unprecedented awareness of diabetes control and relieves the pain and inconvenience of finger sticks and blood draws. It also aids with compliance because patients don’t need to remember to check their sugar levels on a schedule.

Other compliance-boosting breakthroughs, such as Bluetooth-enabled asthma inhalers and cellular-connected continuous positive airway pressure machines, assist patients with managing chronic respiratory conditions. Many companies are developing technologies to manage acute conditions as well. One such company, an on-demand telemedicine provider called TytoCare, has developed a $299 suite of instruments that includes a digital stethoscope, thermometer, and camera-based otoscope. In concert with a virtual visit, their providers can remotely use these tools to examine and assess sick individuals. This virtual “laying on of hands” may have sounded like science fiction and likely would have been rejected by patients just a few years ago. Now it is becoming commonplace and will soon be an expectation of many seeking care.

But if we are to be successful, everyone must acknowledge that this revolution in health care brings many challenges along with it. One of those is the deluge of data that connected devices provide.

Information overload

There is such a thing as “too much of a good thing.” Described by journalist David Shenk as “data smog” in his 1997 book of the same name, the idea is clear: There is only so much information we can assimilate.

Even after years of using EHRs and with government-implemented incentives that promote “meaningful use,” physicians are still struggling with EHRs. Additionally, many have expressed frustration with the connectedness that EHRs provide and lament their inability to ever really “leave the office.” As more and more data become available to physicians, the challenge of how to assimilate and act on those data will continue to grow. The addition of patient-provided health statistics will only make information overload worse, with clinicians will feeling an ever-growing burden to know, understand, and act on this information.

Unless we develop systems to sort, filter, and prioritize the flow of information, there is potential for liability from not acting on the amount of virtual information doctors receive. This new risk for already fatigued and overburdened physicians combined with an increase in the amount of virtual information at doctors’ fingertips may lead to the value of patient data being lost.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

More female specialists, but gender gap persists in pay, survey finds

More female physicians are becoming specialists, a Medscape survey finds, and five specialties have seen particularly large increases during the last 5 years.

Obstetrician/gynecologists and pediatricians had the largest female representation at 58% and those percentages were both up from 50% in 2015, according to the Medscape Female Physician Compensation Report 2020.

Rheumatology saw a dramatic jump in numbers of women from 29% in 2015 to 54% now. Dermatology increased from 32% to 49%, and family medicine rose from 35% to 43% during that time.

Specialist pay gap narrows slightly

The gender gap was the same this year in primary care — women made 25% less ($212,000 vs. $264,000).

The gap in specialists narrowed slightly. Women made 31% less this year ($286,000 vs $375,000) instead of the 33% less reported in last year’s survey, a difference of $89,000 this year.

The gender pay gap was consistent across all race and age groups and was consistent in responses about net worth. Whereas 57% of male physicians had a net worth of $1 million or more, only 40% of female physicians did. Twice as many male physicians as female physicians had a net worth of more than $5 million (10% vs. 5%).

“Many physicians expect the gender pay gap to narrow in the coming years,” John Prescott, MD, chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said in an interview.

“Yet, it is a challenging task, requiring an institutional commitment to transparency, cross-campus collaboration, ongoing communication, dedicated resources, and enlightened leadership,” he said.

Female physicians working in office-based, solo practices made the most overall at $290,000; women in outpatient settings made the least at $223,000.

The survey included more than 4,500 responses. The responses were collected during the early part of the year and do not reflect changes in income expected from the COVID-19 pandemic.

An analysis in Health Affairs, for instance, predicted that primary care practices would lose $67,774 in gross revenue per full-time-equivalent physician in calendar year 2020 because of the pandemic.

Most physicians did not experience a significant financial loss in 2019, but COVID-19 may, at least temporarily, change those answers in next year’s report, physicians predicted.

Women more likely than men to live above their means

More women this year (39%) said they live below their means than answered that way last year (31%). Female physicians were more likely to say they lived above their means than were their male counterparts (8% vs. 6%).

Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., says aiming for putting away 20% of total gross salary is a good financial goal.

Women in this year’s survey spent about 7% less time seeing patients than did their male counterparts (35.9 hours a week vs. 38.8). The average for all physicians was 37.8 hours a week. Add the 15.6 average hours per week physicians spend on paperwork, and they are putting in 53-hour workweeks on average overall.

Asked what parts of their job they found most rewarding, women were more likely than were men to say “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31% vs. 25%). They were less likely than were men to answer that the most rewarding part was “being very good at what I do/finding answers/diagnoses” (22% vs. 25%) or “making good money at a job I like” (9% vs. 13%).

Most female physicians — and physicians overall — said they would choose medicine again. But two specialties saw a substantial increase in that answer.

This year, 79% of those in physical medicine and rehabilitation said they would choose medicine again (compared with 66% last year) and 84% of gastroenterologists answered that way (compared with 76% in 2019).

Psychiatrists, however, were in the group least likely to say they would choose their specialty again along with those in internal medicine, family medicine, and diabetes and endocrinology.

Female physicians in orthopedics, radiology, and dermatology were most likely to choose their specialties again (91% - 92%).

Female physicians were less likely to use physician assistants in their practices than were their male colleagues (31% vs. 38%) but more likely to use NPs (52% vs. 50%). More than a third (38%) of male and female physicians reported they use neither.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

More female physicians are becoming specialists, a Medscape survey finds, and five specialties have seen particularly large increases during the last 5 years.

Obstetrician/gynecologists and pediatricians had the largest female representation at 58% and those percentages were both up from 50% in 2015, according to the Medscape Female Physician Compensation Report 2020.

Rheumatology saw a dramatic jump in numbers of women from 29% in 2015 to 54% now. Dermatology increased from 32% to 49%, and family medicine rose from 35% to 43% during that time.

Specialist pay gap narrows slightly

The gender gap was the same this year in primary care — women made 25% less ($212,000 vs. $264,000).

The gap in specialists narrowed slightly. Women made 31% less this year ($286,000 vs $375,000) instead of the 33% less reported in last year’s survey, a difference of $89,000 this year.

The gender pay gap was consistent across all race and age groups and was consistent in responses about net worth. Whereas 57% of male physicians had a net worth of $1 million or more, only 40% of female physicians did. Twice as many male physicians as female physicians had a net worth of more than $5 million (10% vs. 5%).

“Many physicians expect the gender pay gap to narrow in the coming years,” John Prescott, MD, chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said in an interview.

“Yet, it is a challenging task, requiring an institutional commitment to transparency, cross-campus collaboration, ongoing communication, dedicated resources, and enlightened leadership,” he said.

Female physicians working in office-based, solo practices made the most overall at $290,000; women in outpatient settings made the least at $223,000.

The survey included more than 4,500 responses. The responses were collected during the early part of the year and do not reflect changes in income expected from the COVID-19 pandemic.

An analysis in Health Affairs, for instance, predicted that primary care practices would lose $67,774 in gross revenue per full-time-equivalent physician in calendar year 2020 because of the pandemic.

Most physicians did not experience a significant financial loss in 2019, but COVID-19 may, at least temporarily, change those answers in next year’s report, physicians predicted.

Women more likely than men to live above their means

More women this year (39%) said they live below their means than answered that way last year (31%). Female physicians were more likely to say they lived above their means than were their male counterparts (8% vs. 6%).

Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., says aiming for putting away 20% of total gross salary is a good financial goal.

Women in this year’s survey spent about 7% less time seeing patients than did their male counterparts (35.9 hours a week vs. 38.8). The average for all physicians was 37.8 hours a week. Add the 15.6 average hours per week physicians spend on paperwork, and they are putting in 53-hour workweeks on average overall.

Asked what parts of their job they found most rewarding, women were more likely than were men to say “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31% vs. 25%). They were less likely than were men to answer that the most rewarding part was “being very good at what I do/finding answers/diagnoses” (22% vs. 25%) or “making good money at a job I like” (9% vs. 13%).

Most female physicians — and physicians overall — said they would choose medicine again. But two specialties saw a substantial increase in that answer.

This year, 79% of those in physical medicine and rehabilitation said they would choose medicine again (compared with 66% last year) and 84% of gastroenterologists answered that way (compared with 76% in 2019).

Psychiatrists, however, were in the group least likely to say they would choose their specialty again along with those in internal medicine, family medicine, and diabetes and endocrinology.

Female physicians in orthopedics, radiology, and dermatology were most likely to choose their specialties again (91% - 92%).

Female physicians were less likely to use physician assistants in their practices than were their male colleagues (31% vs. 38%) but more likely to use NPs (52% vs. 50%). More than a third (38%) of male and female physicians reported they use neither.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

More female physicians are becoming specialists, a Medscape survey finds, and five specialties have seen particularly large increases during the last 5 years.

Obstetrician/gynecologists and pediatricians had the largest female representation at 58% and those percentages were both up from 50% in 2015, according to the Medscape Female Physician Compensation Report 2020.

Rheumatology saw a dramatic jump in numbers of women from 29% in 2015 to 54% now. Dermatology increased from 32% to 49%, and family medicine rose from 35% to 43% during that time.

Specialist pay gap narrows slightly

The gender gap was the same this year in primary care — women made 25% less ($212,000 vs. $264,000).

The gap in specialists narrowed slightly. Women made 31% less this year ($286,000 vs $375,000) instead of the 33% less reported in last year’s survey, a difference of $89,000 this year.

The gender pay gap was consistent across all race and age groups and was consistent in responses about net worth. Whereas 57% of male physicians had a net worth of $1 million or more, only 40% of female physicians did. Twice as many male physicians as female physicians had a net worth of more than $5 million (10% vs. 5%).

“Many physicians expect the gender pay gap to narrow in the coming years,” John Prescott, MD, chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, said in an interview.

“Yet, it is a challenging task, requiring an institutional commitment to transparency, cross-campus collaboration, ongoing communication, dedicated resources, and enlightened leadership,” he said.

Female physicians working in office-based, solo practices made the most overall at $290,000; women in outpatient settings made the least at $223,000.

The survey included more than 4,500 responses. The responses were collected during the early part of the year and do not reflect changes in income expected from the COVID-19 pandemic.

An analysis in Health Affairs, for instance, predicted that primary care practices would lose $67,774 in gross revenue per full-time-equivalent physician in calendar year 2020 because of the pandemic.

Most physicians did not experience a significant financial loss in 2019, but COVID-19 may, at least temporarily, change those answers in next year’s report, physicians predicted.

Women more likely than men to live above their means

More women this year (39%) said they live below their means than answered that way last year (31%). Female physicians were more likely to say they lived above their means than were their male counterparts (8% vs. 6%).

Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minn., says aiming for putting away 20% of total gross salary is a good financial goal.

Women in this year’s survey spent about 7% less time seeing patients than did their male counterparts (35.9 hours a week vs. 38.8). The average for all physicians was 37.8 hours a week. Add the 15.6 average hours per week physicians spend on paperwork, and they are putting in 53-hour workweeks on average overall.

Asked what parts of their job they found most rewarding, women were more likely than were men to say “gratitude/relationships with patients” (31% vs. 25%). They were less likely than were men to answer that the most rewarding part was “being very good at what I do/finding answers/diagnoses” (22% vs. 25%) or “making good money at a job I like” (9% vs. 13%).

Most female physicians — and physicians overall — said they would choose medicine again. But two specialties saw a substantial increase in that answer.

This year, 79% of those in physical medicine and rehabilitation said they would choose medicine again (compared with 66% last year) and 84% of gastroenterologists answered that way (compared with 76% in 2019).

Psychiatrists, however, were in the group least likely to say they would choose their specialty again along with those in internal medicine, family medicine, and diabetes and endocrinology.

Female physicians in orthopedics, radiology, and dermatology were most likely to choose their specialties again (91% - 92%).

Female physicians were less likely to use physician assistants in their practices than were their male colleagues (31% vs. 38%) but more likely to use NPs (52% vs. 50%). More than a third (38%) of male and female physicians reported they use neither.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 Screening and Testing Among Patients With Neurologic Dysfunction: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

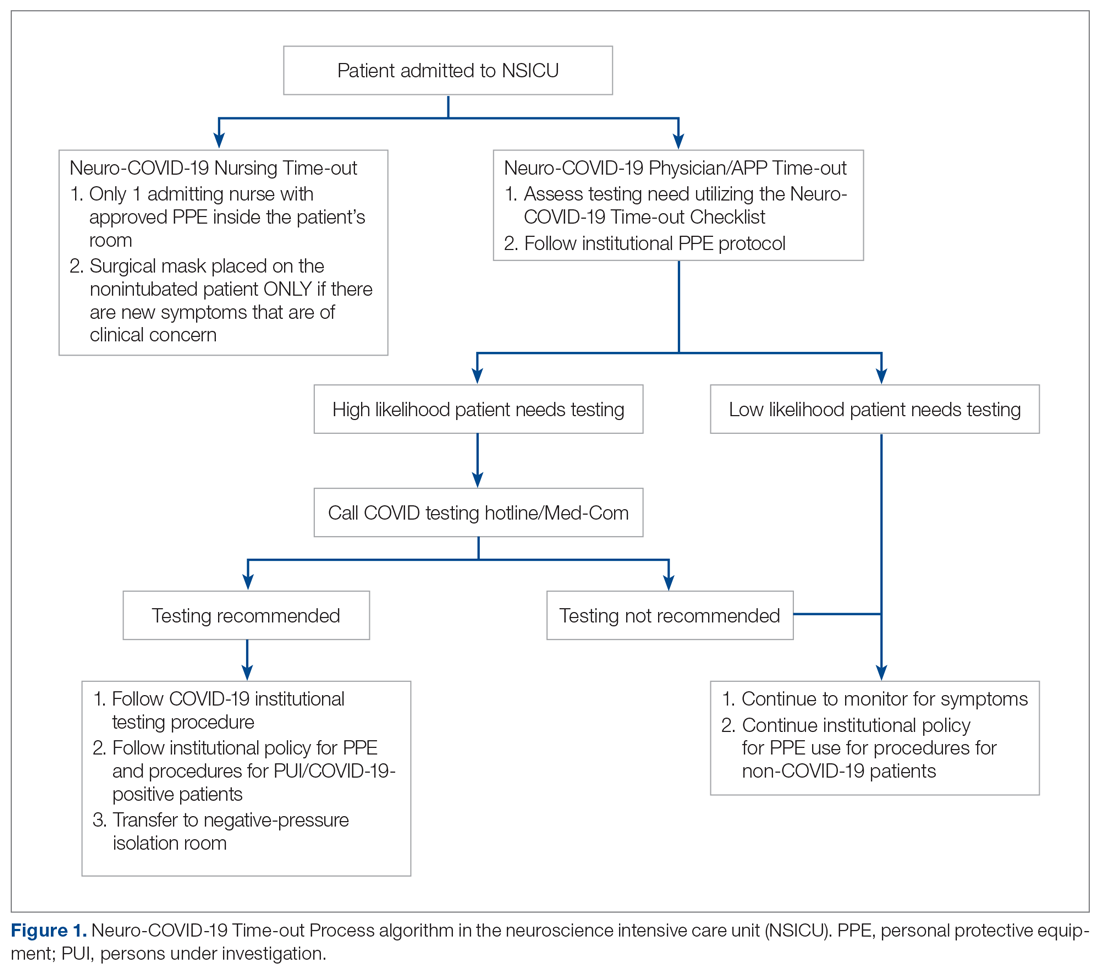

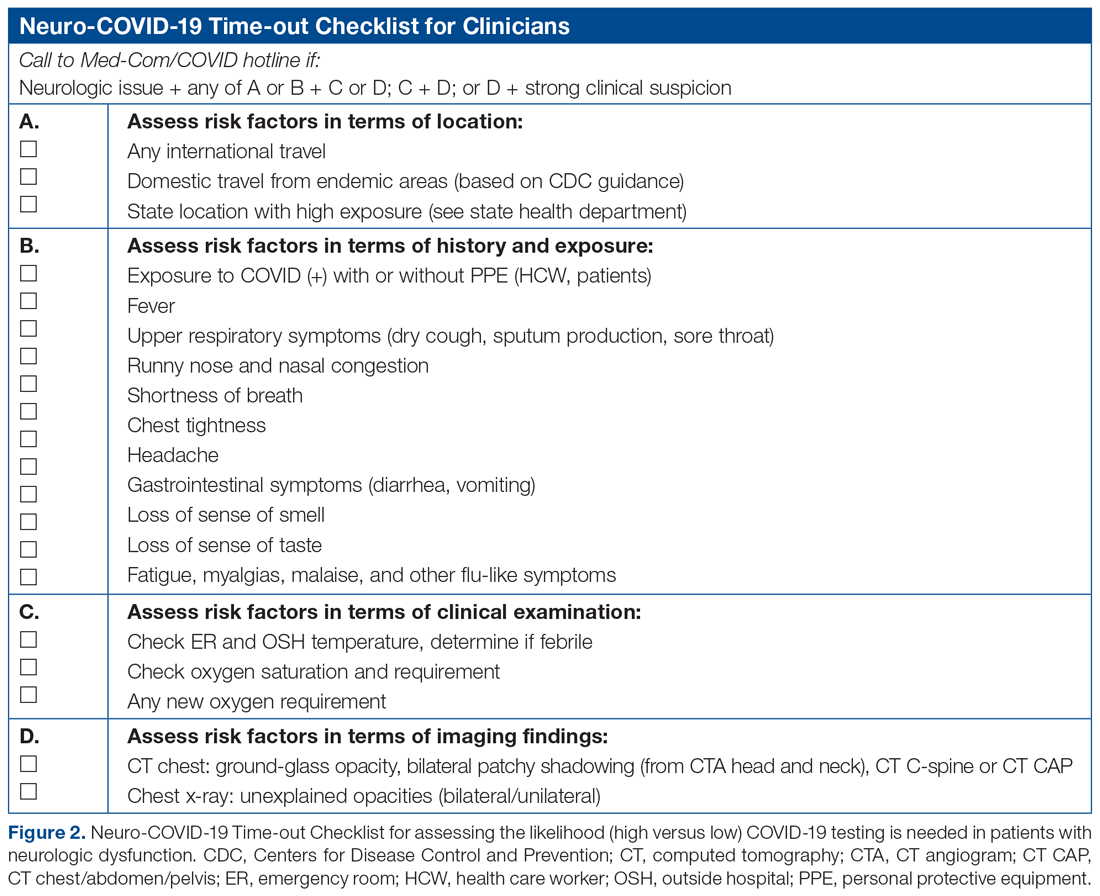

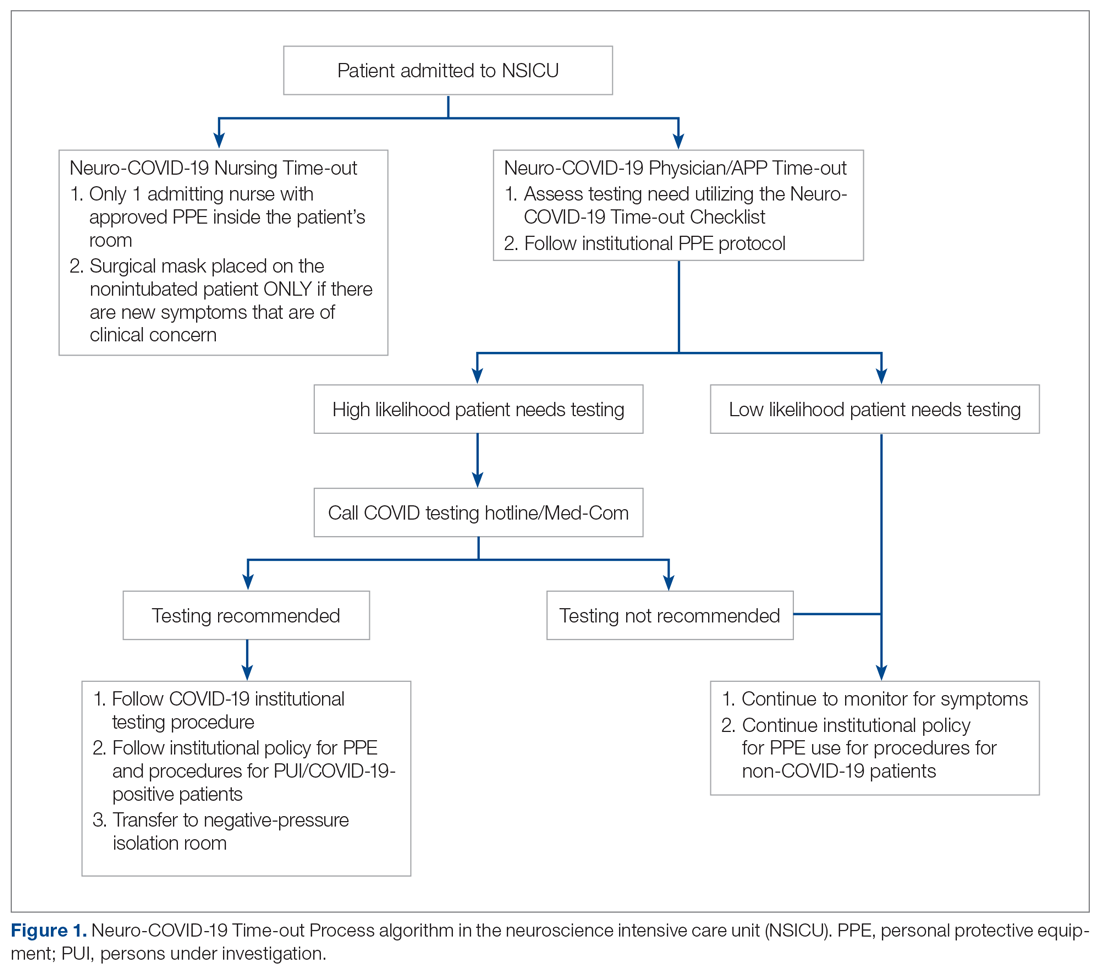

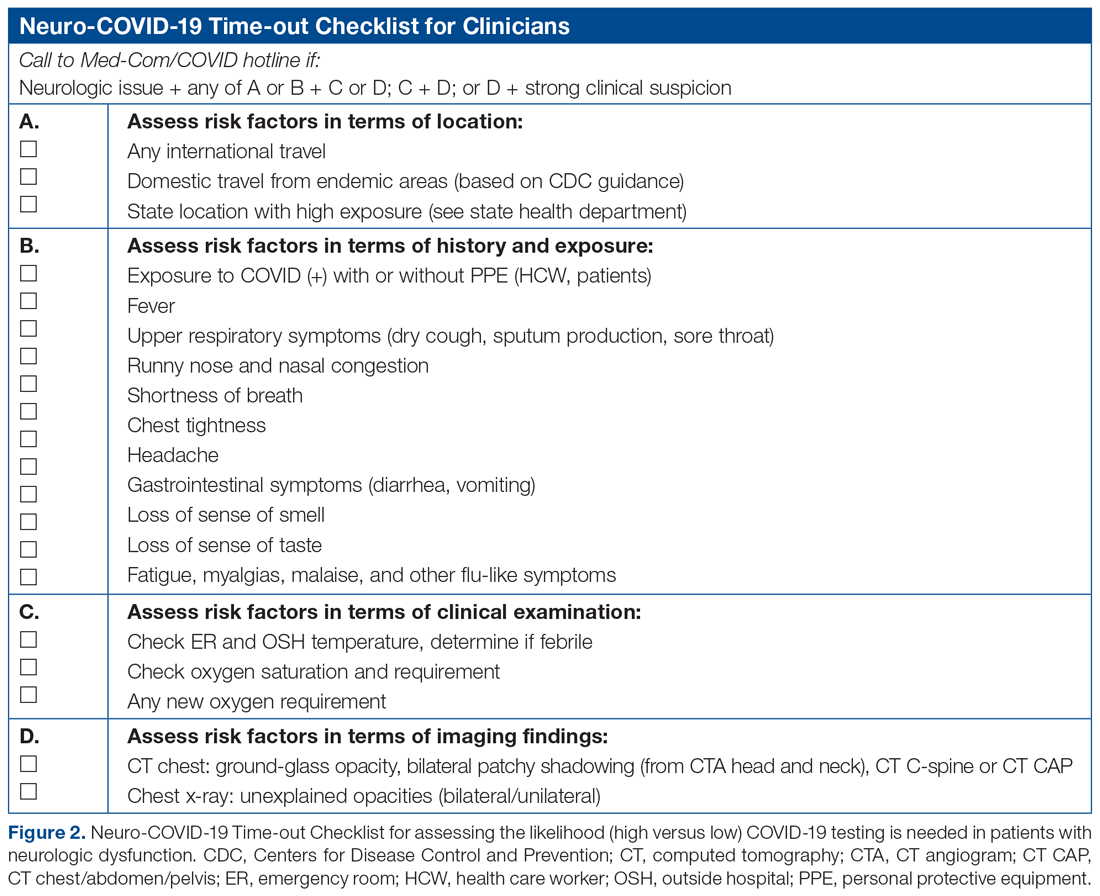

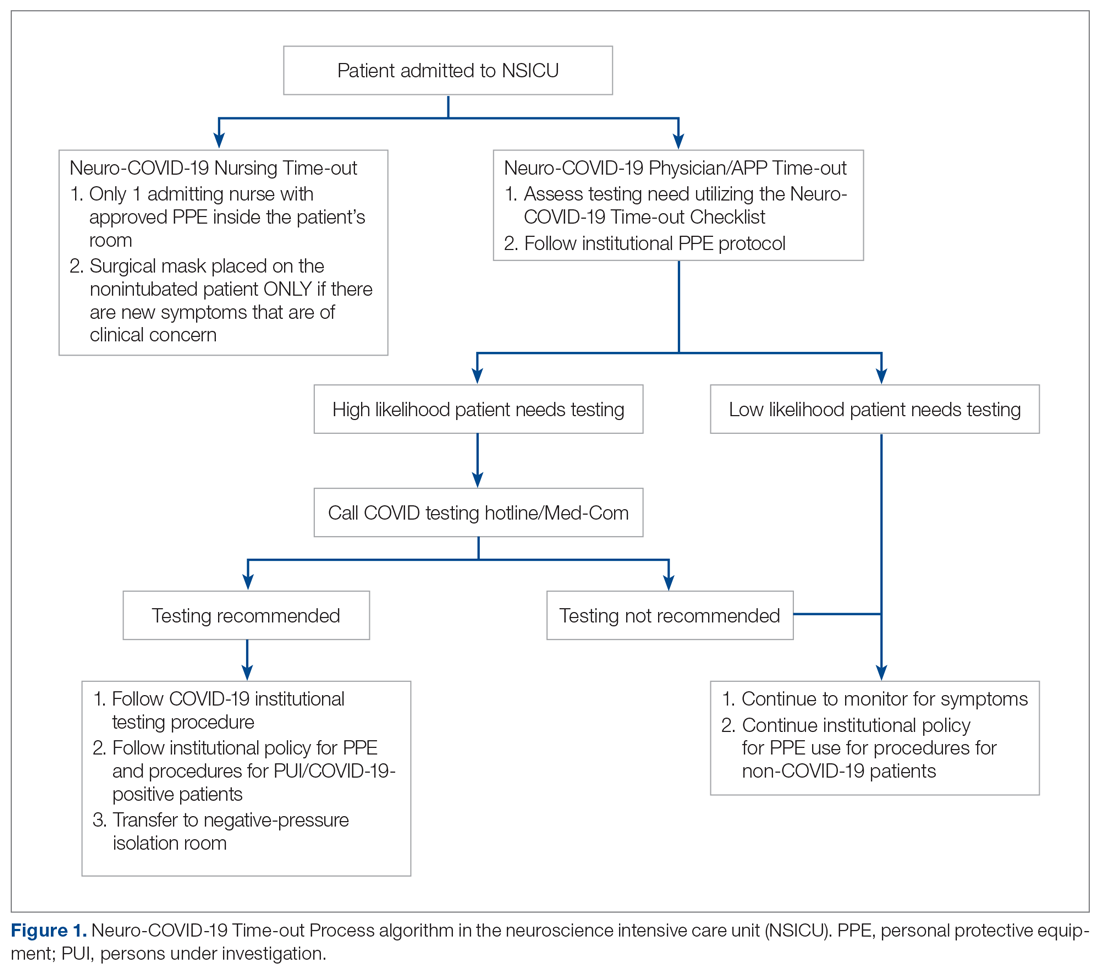

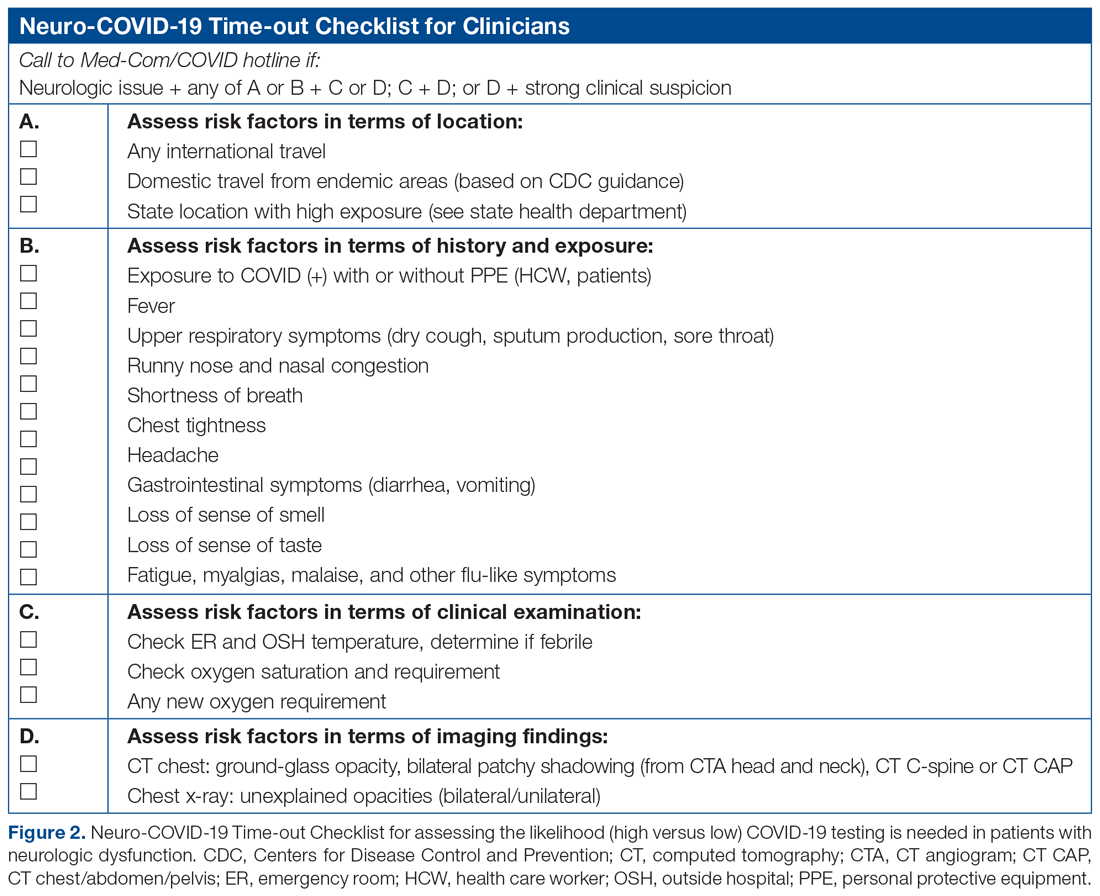

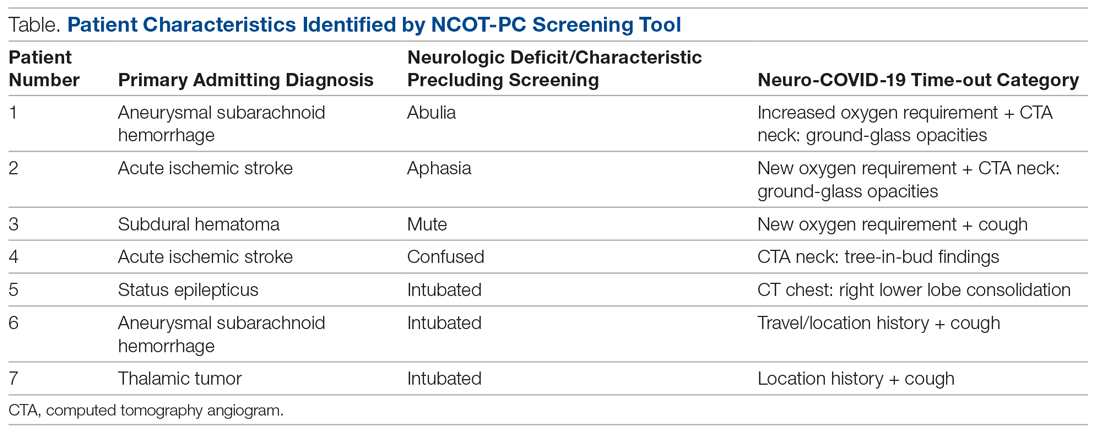

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

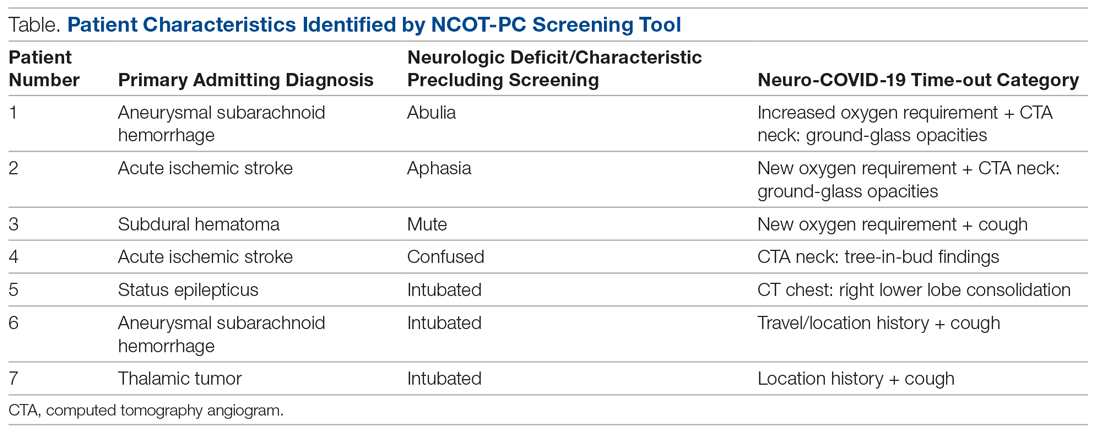

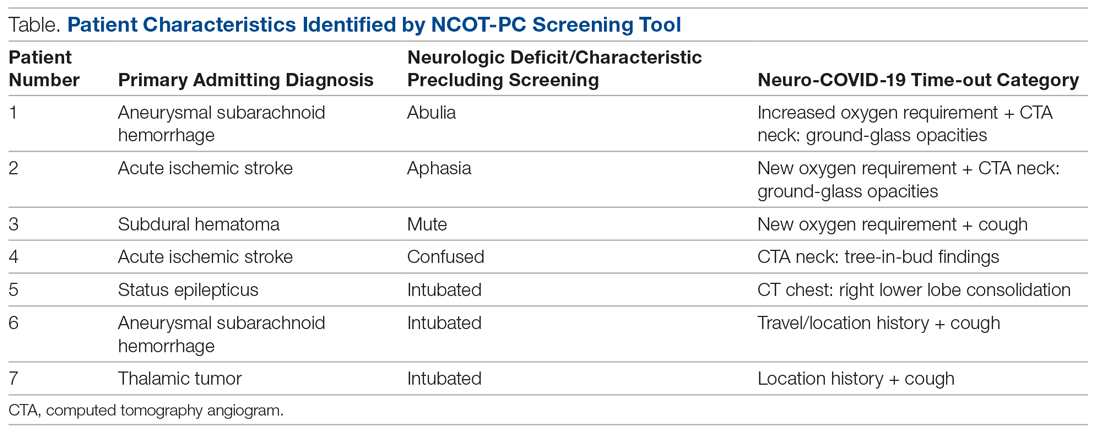

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions