User login

The professional advancement of drug and device innovation

I often say that there are both “guardrail” days and very good days when it comes to the ins and outs of health care builds and product launches. The process is much like starting down the path of a country road in the middle of a blizzard—unless you have dependable wipers and a good defrost system, that path can get murky very quickly. With this article I hope to offer my counsel to inventors, featuring a few of my prior launches as well as case studies of health care launches I was not involved with, and sharing the lessons learned and hurdles that were overcome. I encourage all entrepreneurs to act on their ideas because, in the world of health care startups, the only failure is not acting on an invention.

Case study 1: Cerezyme

Today, Cerezyme is indicated for patients with Gaucher, which is a lysosomal storage disorder. Cerezyme’s first-generation product, called Ceredase, was a human tissue-derived protein that we extracted from human placentas. At the time, the concept of moving this program forward was denied by the Board of Directors because they said that even if you could collect enough placentas to make the enzyme, it would be too expensive to manufacture. In fact, early scale-up modeling for manufacturing the protein demonstrated that Genzyme would need 4 tons of placentas per Gaucher patient per year.

Gaucher is a severe, early-onset disease that has a significant negative outcome for patients. Patients with Gaucher are in dire need of treatment. Genzyme went forward with the Ceredase program by financing it through the families of patients with the disease, by starting an LLC separate from the business and funding the initial clinical trial and the development of the protein through the families of Gaucher patients. That approach was a successful endeavor. A great example of a creative capital structure to advance a program.

This was in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and at the height of the AIDS challenge. Genzyme based the manufacturing in Lille, France, and we cryopreserved placentas in the United States and Europe and shipped them to Lille to be processed into therapy. Genzyme eventually received approval for Ceredase from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. At the height of the placenta collection, we were gathering about 10% to 15% of the placentas in the United States and 30% to 40% of the placentas in Europe. Resources supply became an issue until we developed a recombinant form of the protein, accomplished by using a manufacturing system called a CHO cell line.

This is a very good success story: If this invention was not pursued, Gaucher patients would not benefit from the treatment today. In addition, there are a plethora of patients with different lysosomal storage disorders treated with additional proteins that have been aided by us going through the entire development, manufacturing, and global commercialization process. We figured out how to manufacture and deliver the treatment, working through multiple countries’ political systems, and today the therapy is paid for by insurance and government systems on a worldwide basis.

Continue to: Case study 2...

Case study 2: ThinPrep

I like to use the approval of ThinPrep as an example of avoiding a false negative—a stoppage in the development of the product or drug for the wrong reasons. False negatives, in my mind, occur when you are developing a technology and you run into issues during the clinical phase and/or with FDA approval, or with a technical failure or you run out of capital prior to knowing whether or not the innovation actually works. In the case of ThinPrep, a poorly run clinical trial almost resulted in a false negative.

The company at the time was Cytyc, and an initial clinical study presented to the FDA yielded a neutral-negative outcome. The FDA said that there were not enough data to show the differentiation from the current Pap smear standard of care.

The founders of the company at that time had inherited the study protocol from a prior leadership team, so they had to finish the trial with the initial protocol. Given the FDA’s advisement, they developed a new trial. It took the persistence of these two founders, who mortgaged their homes and spent their personal dollars to take this through the next wave of clinical development. In the end it was successful. The revised clinical trial yielded an approval for ThinPrep, which is now considered a standard of care.

The use of ThinPrep reduced cervical cancer deaths by 40% from preapproval. The challenging path from clinical development to eventual commercial launch and physician leadership in advancing patient care makes the story of ThinPrep a great example of not allowing an early false negative of a poorly designed and run clinical trial stop important innovation.

Case study 3: Cologuard

The development of Cologuard is a case study demonstrating that, sometimes, when your first attempt does not work, you need to have the persistence to raise additional capital and/or use a slightly different technical approach. The approval story of Cologuard is important to share because it is an important cancer screening diagnostic, using DNA from stool samples to test for colon cancer, giving access to important colon cancer screening to many patients. Currently, caregivers are only scraping the surface with Cologuard’s ability to screen the population. There are many more patients that need access to the test, and I believe they will get it in the years ahead.

Cologuard went through a first- and second-generational technical failure. They could not get the test’s specificity and sensitivity to be at the level of a screening tool; there were too many false-positive results. With the third iteration came the technical breakthrough, and a very large, expensive study was conducted—one the leadership team was criticized for. However, that study yielded the data that achieved a New England Journal of Medicine article, and reimbursement support across the country. The combination of the right technical team and the right leadership team, who planned a proper commercial launch, with a CEO that supported the extensive clinical study, has resulted in the fourth generation of Cologuard—an important breakthrough offering a very useful new standard of care in colon cancer detection and screening.

Continue to: Pearls for moving your innovations forward...

Pearls for moving your innovations forward

Because of my experience in undergoing health care start-ups, and contributing to several of those advancements of innovation, many inventors approach me for advice on their paths from idea to full-concept company. Here are a few of my lessons learned.

Consider purpose, not financial gain, first and foremost. Financial gain is typically the by-product or outcome of a standard-of-care breakthrough for inventors, but it’s a very hard road. Pursue your invention for advancing patient care and moving a new standard of care forward in health care versus financial gain at the end.

Determine whether your invention is a product or a company, or potentially, not capitalizable at all. Figure this out early. Analyze your idea to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and the market dynamics to support a new product. Can the development path be defined very clearly to raise capital? Is your innovation a big enough breakthrough in the market with several current products to actually make a difference in patient outcomes (and eventually achieve product reimbursement)? The creation of a company may be the right strategy if the innovation can support a differentiated enough breakthrough where you can actually support all the infrastructure to build the business. If you find that the market is not there to support and develop your idea to eventual success, backing off early is important to preserve invested capital.

Protect early. Is your invention patentable, or has someone else already thought of the idea? What kind of patent(s) are appropriate? Where, geographically, do you want to protect your invention? Find a good patent attorney in your local area, early in the process, to help you answer all of these critical questions. Patents are expensive to file and maintain, but it is not expensive to do a literature search to find out if your idea is novel. A provisional patent, which would be your first step, is an important cost-effective step.

Capital is out there. If your invention or idea deserves capital, it is available. I will address raising capital in more detail in the next section.

Consider regulatory and manufacturing as achievable hurdles. Inventors often get tripped up here, considering the regulatory hurdles and manufacturing too challenging and abandoning their ideas because the risk is too great. Regulatory and manufacturing are very important aspects of health care standard-of-care builds. Cutting corners is not an option. That said, regulatory and manufacturing should not stop you. Challenges often can be worked through as long as the clinical need is there, and the clinical data support bringing that technology forward.

Consider corporate partnerships. I am a fan of corporate partners. But which ones should you target, and when and why? Corporate partnerships can bring significant capital, which is great, but there is enough investor capital out there that you should not pursue a corporate partner just for capital. The main benefit of a corporate partner is enterprise intellect. They typically know more about the field that you are entering than the investors or a small company leadership team.

Establish and listen to advisors. When thinking about who to trust, research their track record. Advisors who have gone through this process before, and specifically in your product area, are important to have access to.

Persistence is key. I have observed a tremendous “compression of innovation” in the health care areas that I have been involved with—human tissue-derived proteins, robotic surgery, stem cell therapy, and digital health (which is still in its infancy). For each of these breakthrough categories, early on, it appeared that it couldn’t be done. However, after the first 2 or 3 major breakthroughs in each one of these areas, a compression of innovation occurred. For instance, after approximately 15 years of protein development, we came out with the recombinant manufacturing systems for proteins. Very quickly, within 10 years, there were more than 70 proteins on the market. The persistence of the inventors to overcome early obstacles in each of these health care areas was critical to future success in each area.

Continue to: Raising capital...

Raising capital

There are different investors who specialize in different types of investment opportunities. The first phase of raising capital is the seed round—where there is typically early data, or even no data and just a concept. From this seed round forward, there is less risk as you develop your technology; thus, there are different investors that support different stages of development and that specialize in different types of investing. It is important to target the right investors and raise enough capital to be able to go achieve multiple operational milestones. Otherwise, when you go through your first round of capital, or the Series A or B financing rounds, there may not be a set of investors out there to fund the company moving forward. Health care investors will make it known that they invest in certain rounds of capital. You can determine who those investors are by doing a search online.

A mistake health care inventors can make is not taking enough capital from investors, because they are concerned about dilution. I advise investors not to focus on dilution but rather on, how big can you make “the pie” (value of the company) worth? The entire process is about bringing a true product through to a new standard-of-care curve.

Trust is the most important thing to earn with investors, and there is zero tolerance for a lack of trust. Share your vision as the inventor with investors, who want to know where this category could be in the next 5 or 10 years. Clinical data will always win, and health care investors and industry leaders should be focused on executing the most robust clinical data to demonstrate the clearest potential clinical outcome. Investors will follow a good plan that has been developed to achieve FDA approval, successful commercialization or “go to market” launch, and eventual reimbursement to support a true standard-of-care change.

Failure is defined by inaction

The 3 case studies that I have shared were success stories because the ideas and inventions were acted upon. When I was at Genzyme, we built the company up to more than $1 billion in revenue. We commercialized proteins in over 50 countries. Most importantly, many patients benefited from the innovation. If you have an invention and an idea, act on it—and surround yourself with great people in every discipline. Having the right people and team is extremely important. ●

I often say that there are both “guardrail” days and very good days when it comes to the ins and outs of health care builds and product launches. The process is much like starting down the path of a country road in the middle of a blizzard—unless you have dependable wipers and a good defrost system, that path can get murky very quickly. With this article I hope to offer my counsel to inventors, featuring a few of my prior launches as well as case studies of health care launches I was not involved with, and sharing the lessons learned and hurdles that were overcome. I encourage all entrepreneurs to act on their ideas because, in the world of health care startups, the only failure is not acting on an invention.

Case study 1: Cerezyme

Today, Cerezyme is indicated for patients with Gaucher, which is a lysosomal storage disorder. Cerezyme’s first-generation product, called Ceredase, was a human tissue-derived protein that we extracted from human placentas. At the time, the concept of moving this program forward was denied by the Board of Directors because they said that even if you could collect enough placentas to make the enzyme, it would be too expensive to manufacture. In fact, early scale-up modeling for manufacturing the protein demonstrated that Genzyme would need 4 tons of placentas per Gaucher patient per year.

Gaucher is a severe, early-onset disease that has a significant negative outcome for patients. Patients with Gaucher are in dire need of treatment. Genzyme went forward with the Ceredase program by financing it through the families of patients with the disease, by starting an LLC separate from the business and funding the initial clinical trial and the development of the protein through the families of Gaucher patients. That approach was a successful endeavor. A great example of a creative capital structure to advance a program.

This was in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and at the height of the AIDS challenge. Genzyme based the manufacturing in Lille, France, and we cryopreserved placentas in the United States and Europe and shipped them to Lille to be processed into therapy. Genzyme eventually received approval for Ceredase from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. At the height of the placenta collection, we were gathering about 10% to 15% of the placentas in the United States and 30% to 40% of the placentas in Europe. Resources supply became an issue until we developed a recombinant form of the protein, accomplished by using a manufacturing system called a CHO cell line.

This is a very good success story: If this invention was not pursued, Gaucher patients would not benefit from the treatment today. In addition, there are a plethora of patients with different lysosomal storage disorders treated with additional proteins that have been aided by us going through the entire development, manufacturing, and global commercialization process. We figured out how to manufacture and deliver the treatment, working through multiple countries’ political systems, and today the therapy is paid for by insurance and government systems on a worldwide basis.

Continue to: Case study 2...

Case study 2: ThinPrep

I like to use the approval of ThinPrep as an example of avoiding a false negative—a stoppage in the development of the product or drug for the wrong reasons. False negatives, in my mind, occur when you are developing a technology and you run into issues during the clinical phase and/or with FDA approval, or with a technical failure or you run out of capital prior to knowing whether or not the innovation actually works. In the case of ThinPrep, a poorly run clinical trial almost resulted in a false negative.

The company at the time was Cytyc, and an initial clinical study presented to the FDA yielded a neutral-negative outcome. The FDA said that there were not enough data to show the differentiation from the current Pap smear standard of care.

The founders of the company at that time had inherited the study protocol from a prior leadership team, so they had to finish the trial with the initial protocol. Given the FDA’s advisement, they developed a new trial. It took the persistence of these two founders, who mortgaged their homes and spent their personal dollars to take this through the next wave of clinical development. In the end it was successful. The revised clinical trial yielded an approval for ThinPrep, which is now considered a standard of care.

The use of ThinPrep reduced cervical cancer deaths by 40% from preapproval. The challenging path from clinical development to eventual commercial launch and physician leadership in advancing patient care makes the story of ThinPrep a great example of not allowing an early false negative of a poorly designed and run clinical trial stop important innovation.

Case study 3: Cologuard

The development of Cologuard is a case study demonstrating that, sometimes, when your first attempt does not work, you need to have the persistence to raise additional capital and/or use a slightly different technical approach. The approval story of Cologuard is important to share because it is an important cancer screening diagnostic, using DNA from stool samples to test for colon cancer, giving access to important colon cancer screening to many patients. Currently, caregivers are only scraping the surface with Cologuard’s ability to screen the population. There are many more patients that need access to the test, and I believe they will get it in the years ahead.

Cologuard went through a first- and second-generational technical failure. They could not get the test’s specificity and sensitivity to be at the level of a screening tool; there were too many false-positive results. With the third iteration came the technical breakthrough, and a very large, expensive study was conducted—one the leadership team was criticized for. However, that study yielded the data that achieved a New England Journal of Medicine article, and reimbursement support across the country. The combination of the right technical team and the right leadership team, who planned a proper commercial launch, with a CEO that supported the extensive clinical study, has resulted in the fourth generation of Cologuard—an important breakthrough offering a very useful new standard of care in colon cancer detection and screening.

Continue to: Pearls for moving your innovations forward...

Pearls for moving your innovations forward

Because of my experience in undergoing health care start-ups, and contributing to several of those advancements of innovation, many inventors approach me for advice on their paths from idea to full-concept company. Here are a few of my lessons learned.

Consider purpose, not financial gain, first and foremost. Financial gain is typically the by-product or outcome of a standard-of-care breakthrough for inventors, but it’s a very hard road. Pursue your invention for advancing patient care and moving a new standard of care forward in health care versus financial gain at the end.

Determine whether your invention is a product or a company, or potentially, not capitalizable at all. Figure this out early. Analyze your idea to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and the market dynamics to support a new product. Can the development path be defined very clearly to raise capital? Is your innovation a big enough breakthrough in the market with several current products to actually make a difference in patient outcomes (and eventually achieve product reimbursement)? The creation of a company may be the right strategy if the innovation can support a differentiated enough breakthrough where you can actually support all the infrastructure to build the business. If you find that the market is not there to support and develop your idea to eventual success, backing off early is important to preserve invested capital.

Protect early. Is your invention patentable, or has someone else already thought of the idea? What kind of patent(s) are appropriate? Where, geographically, do you want to protect your invention? Find a good patent attorney in your local area, early in the process, to help you answer all of these critical questions. Patents are expensive to file and maintain, but it is not expensive to do a literature search to find out if your idea is novel. A provisional patent, which would be your first step, is an important cost-effective step.

Capital is out there. If your invention or idea deserves capital, it is available. I will address raising capital in more detail in the next section.

Consider regulatory and manufacturing as achievable hurdles. Inventors often get tripped up here, considering the regulatory hurdles and manufacturing too challenging and abandoning their ideas because the risk is too great. Regulatory and manufacturing are very important aspects of health care standard-of-care builds. Cutting corners is not an option. That said, regulatory and manufacturing should not stop you. Challenges often can be worked through as long as the clinical need is there, and the clinical data support bringing that technology forward.

Consider corporate partnerships. I am a fan of corporate partners. But which ones should you target, and when and why? Corporate partnerships can bring significant capital, which is great, but there is enough investor capital out there that you should not pursue a corporate partner just for capital. The main benefit of a corporate partner is enterprise intellect. They typically know more about the field that you are entering than the investors or a small company leadership team.

Establish and listen to advisors. When thinking about who to trust, research their track record. Advisors who have gone through this process before, and specifically in your product area, are important to have access to.

Persistence is key. I have observed a tremendous “compression of innovation” in the health care areas that I have been involved with—human tissue-derived proteins, robotic surgery, stem cell therapy, and digital health (which is still in its infancy). For each of these breakthrough categories, early on, it appeared that it couldn’t be done. However, after the first 2 or 3 major breakthroughs in each one of these areas, a compression of innovation occurred. For instance, after approximately 15 years of protein development, we came out with the recombinant manufacturing systems for proteins. Very quickly, within 10 years, there were more than 70 proteins on the market. The persistence of the inventors to overcome early obstacles in each of these health care areas was critical to future success in each area.

Continue to: Raising capital...

Raising capital

There are different investors who specialize in different types of investment opportunities. The first phase of raising capital is the seed round—where there is typically early data, or even no data and just a concept. From this seed round forward, there is less risk as you develop your technology; thus, there are different investors that support different stages of development and that specialize in different types of investing. It is important to target the right investors and raise enough capital to be able to go achieve multiple operational milestones. Otherwise, when you go through your first round of capital, or the Series A or B financing rounds, there may not be a set of investors out there to fund the company moving forward. Health care investors will make it known that they invest in certain rounds of capital. You can determine who those investors are by doing a search online.

A mistake health care inventors can make is not taking enough capital from investors, because they are concerned about dilution. I advise investors not to focus on dilution but rather on, how big can you make “the pie” (value of the company) worth? The entire process is about bringing a true product through to a new standard-of-care curve.

Trust is the most important thing to earn with investors, and there is zero tolerance for a lack of trust. Share your vision as the inventor with investors, who want to know where this category could be in the next 5 or 10 years. Clinical data will always win, and health care investors and industry leaders should be focused on executing the most robust clinical data to demonstrate the clearest potential clinical outcome. Investors will follow a good plan that has been developed to achieve FDA approval, successful commercialization or “go to market” launch, and eventual reimbursement to support a true standard-of-care change.

Failure is defined by inaction

The 3 case studies that I have shared were success stories because the ideas and inventions were acted upon. When I was at Genzyme, we built the company up to more than $1 billion in revenue. We commercialized proteins in over 50 countries. Most importantly, many patients benefited from the innovation. If you have an invention and an idea, act on it—and surround yourself with great people in every discipline. Having the right people and team is extremely important. ●

I often say that there are both “guardrail” days and very good days when it comes to the ins and outs of health care builds and product launches. The process is much like starting down the path of a country road in the middle of a blizzard—unless you have dependable wipers and a good defrost system, that path can get murky very quickly. With this article I hope to offer my counsel to inventors, featuring a few of my prior launches as well as case studies of health care launches I was not involved with, and sharing the lessons learned and hurdles that were overcome. I encourage all entrepreneurs to act on their ideas because, in the world of health care startups, the only failure is not acting on an invention.

Case study 1: Cerezyme

Today, Cerezyme is indicated for patients with Gaucher, which is a lysosomal storage disorder. Cerezyme’s first-generation product, called Ceredase, was a human tissue-derived protein that we extracted from human placentas. At the time, the concept of moving this program forward was denied by the Board of Directors because they said that even if you could collect enough placentas to make the enzyme, it would be too expensive to manufacture. In fact, early scale-up modeling for manufacturing the protein demonstrated that Genzyme would need 4 tons of placentas per Gaucher patient per year.

Gaucher is a severe, early-onset disease that has a significant negative outcome for patients. Patients with Gaucher are in dire need of treatment. Genzyme went forward with the Ceredase program by financing it through the families of patients with the disease, by starting an LLC separate from the business and funding the initial clinical trial and the development of the protein through the families of Gaucher patients. That approach was a successful endeavor. A great example of a creative capital structure to advance a program.

This was in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and at the height of the AIDS challenge. Genzyme based the manufacturing in Lille, France, and we cryopreserved placentas in the United States and Europe and shipped them to Lille to be processed into therapy. Genzyme eventually received approval for Ceredase from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. At the height of the placenta collection, we were gathering about 10% to 15% of the placentas in the United States and 30% to 40% of the placentas in Europe. Resources supply became an issue until we developed a recombinant form of the protein, accomplished by using a manufacturing system called a CHO cell line.

This is a very good success story: If this invention was not pursued, Gaucher patients would not benefit from the treatment today. In addition, there are a plethora of patients with different lysosomal storage disorders treated with additional proteins that have been aided by us going through the entire development, manufacturing, and global commercialization process. We figured out how to manufacture and deliver the treatment, working through multiple countries’ political systems, and today the therapy is paid for by insurance and government systems on a worldwide basis.

Continue to: Case study 2...

Case study 2: ThinPrep

I like to use the approval of ThinPrep as an example of avoiding a false negative—a stoppage in the development of the product or drug for the wrong reasons. False negatives, in my mind, occur when you are developing a technology and you run into issues during the clinical phase and/or with FDA approval, or with a technical failure or you run out of capital prior to knowing whether or not the innovation actually works. In the case of ThinPrep, a poorly run clinical trial almost resulted in a false negative.

The company at the time was Cytyc, and an initial clinical study presented to the FDA yielded a neutral-negative outcome. The FDA said that there were not enough data to show the differentiation from the current Pap smear standard of care.

The founders of the company at that time had inherited the study protocol from a prior leadership team, so they had to finish the trial with the initial protocol. Given the FDA’s advisement, they developed a new trial. It took the persistence of these two founders, who mortgaged their homes and spent their personal dollars to take this through the next wave of clinical development. In the end it was successful. The revised clinical trial yielded an approval for ThinPrep, which is now considered a standard of care.

The use of ThinPrep reduced cervical cancer deaths by 40% from preapproval. The challenging path from clinical development to eventual commercial launch and physician leadership in advancing patient care makes the story of ThinPrep a great example of not allowing an early false negative of a poorly designed and run clinical trial stop important innovation.

Case study 3: Cologuard

The development of Cologuard is a case study demonstrating that, sometimes, when your first attempt does not work, you need to have the persistence to raise additional capital and/or use a slightly different technical approach. The approval story of Cologuard is important to share because it is an important cancer screening diagnostic, using DNA from stool samples to test for colon cancer, giving access to important colon cancer screening to many patients. Currently, caregivers are only scraping the surface with Cologuard’s ability to screen the population. There are many more patients that need access to the test, and I believe they will get it in the years ahead.

Cologuard went through a first- and second-generational technical failure. They could not get the test’s specificity and sensitivity to be at the level of a screening tool; there were too many false-positive results. With the third iteration came the technical breakthrough, and a very large, expensive study was conducted—one the leadership team was criticized for. However, that study yielded the data that achieved a New England Journal of Medicine article, and reimbursement support across the country. The combination of the right technical team and the right leadership team, who planned a proper commercial launch, with a CEO that supported the extensive clinical study, has resulted in the fourth generation of Cologuard—an important breakthrough offering a very useful new standard of care in colon cancer detection and screening.

Continue to: Pearls for moving your innovations forward...

Pearls for moving your innovations forward

Because of my experience in undergoing health care start-ups, and contributing to several of those advancements of innovation, many inventors approach me for advice on their paths from idea to full-concept company. Here are a few of my lessons learned.

Consider purpose, not financial gain, first and foremost. Financial gain is typically the by-product or outcome of a standard-of-care breakthrough for inventors, but it’s a very hard road. Pursue your invention for advancing patient care and moving a new standard of care forward in health care versus financial gain at the end.

Determine whether your invention is a product or a company, or potentially, not capitalizable at all. Figure this out early. Analyze your idea to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and to make sure it is sound and truly novel. Analyze the competition and the market dynamics to support a new product. Can the development path be defined very clearly to raise capital? Is your innovation a big enough breakthrough in the market with several current products to actually make a difference in patient outcomes (and eventually achieve product reimbursement)? The creation of a company may be the right strategy if the innovation can support a differentiated enough breakthrough where you can actually support all the infrastructure to build the business. If you find that the market is not there to support and develop your idea to eventual success, backing off early is important to preserve invested capital.

Protect early. Is your invention patentable, or has someone else already thought of the idea? What kind of patent(s) are appropriate? Where, geographically, do you want to protect your invention? Find a good patent attorney in your local area, early in the process, to help you answer all of these critical questions. Patents are expensive to file and maintain, but it is not expensive to do a literature search to find out if your idea is novel. A provisional patent, which would be your first step, is an important cost-effective step.

Capital is out there. If your invention or idea deserves capital, it is available. I will address raising capital in more detail in the next section.

Consider regulatory and manufacturing as achievable hurdles. Inventors often get tripped up here, considering the regulatory hurdles and manufacturing too challenging and abandoning their ideas because the risk is too great. Regulatory and manufacturing are very important aspects of health care standard-of-care builds. Cutting corners is not an option. That said, regulatory and manufacturing should not stop you. Challenges often can be worked through as long as the clinical need is there, and the clinical data support bringing that technology forward.

Consider corporate partnerships. I am a fan of corporate partners. But which ones should you target, and when and why? Corporate partnerships can bring significant capital, which is great, but there is enough investor capital out there that you should not pursue a corporate partner just for capital. The main benefit of a corporate partner is enterprise intellect. They typically know more about the field that you are entering than the investors or a small company leadership team.

Establish and listen to advisors. When thinking about who to trust, research their track record. Advisors who have gone through this process before, and specifically in your product area, are important to have access to.

Persistence is key. I have observed a tremendous “compression of innovation” in the health care areas that I have been involved with—human tissue-derived proteins, robotic surgery, stem cell therapy, and digital health (which is still in its infancy). For each of these breakthrough categories, early on, it appeared that it couldn’t be done. However, after the first 2 or 3 major breakthroughs in each one of these areas, a compression of innovation occurred. For instance, after approximately 15 years of protein development, we came out with the recombinant manufacturing systems for proteins. Very quickly, within 10 years, there were more than 70 proteins on the market. The persistence of the inventors to overcome early obstacles in each of these health care areas was critical to future success in each area.

Continue to: Raising capital...

Raising capital

There are different investors who specialize in different types of investment opportunities. The first phase of raising capital is the seed round—where there is typically early data, or even no data and just a concept. From this seed round forward, there is less risk as you develop your technology; thus, there are different investors that support different stages of development and that specialize in different types of investing. It is important to target the right investors and raise enough capital to be able to go achieve multiple operational milestones. Otherwise, when you go through your first round of capital, or the Series A or B financing rounds, there may not be a set of investors out there to fund the company moving forward. Health care investors will make it known that they invest in certain rounds of capital. You can determine who those investors are by doing a search online.

A mistake health care inventors can make is not taking enough capital from investors, because they are concerned about dilution. I advise investors not to focus on dilution but rather on, how big can you make “the pie” (value of the company) worth? The entire process is about bringing a true product through to a new standard-of-care curve.

Trust is the most important thing to earn with investors, and there is zero tolerance for a lack of trust. Share your vision as the inventor with investors, who want to know where this category could be in the next 5 or 10 years. Clinical data will always win, and health care investors and industry leaders should be focused on executing the most robust clinical data to demonstrate the clearest potential clinical outcome. Investors will follow a good plan that has been developed to achieve FDA approval, successful commercialization or “go to market” launch, and eventual reimbursement to support a true standard-of-care change.

Failure is defined by inaction

The 3 case studies that I have shared were success stories because the ideas and inventions were acted upon. When I was at Genzyme, we built the company up to more than $1 billion in revenue. We commercialized proteins in over 50 countries. Most importantly, many patients benefited from the innovation. If you have an invention and an idea, act on it—and surround yourself with great people in every discipline. Having the right people and team is extremely important. ●

How ObGyns can best work with radiologists to optimize screening for patients with dense breasts

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

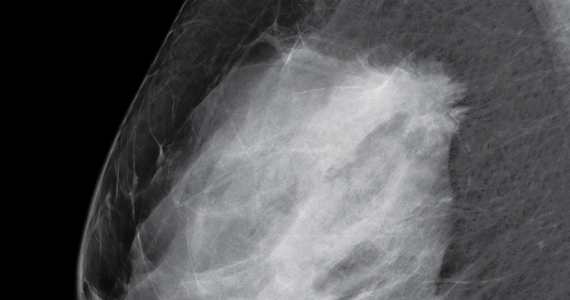

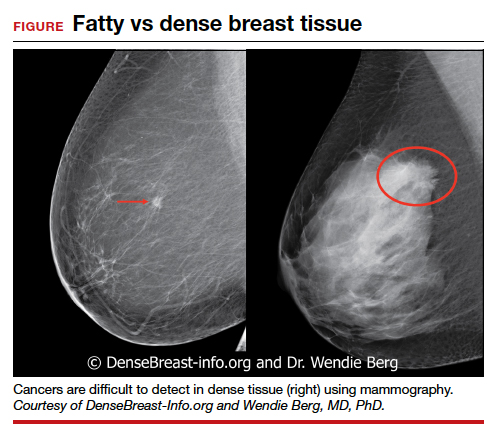

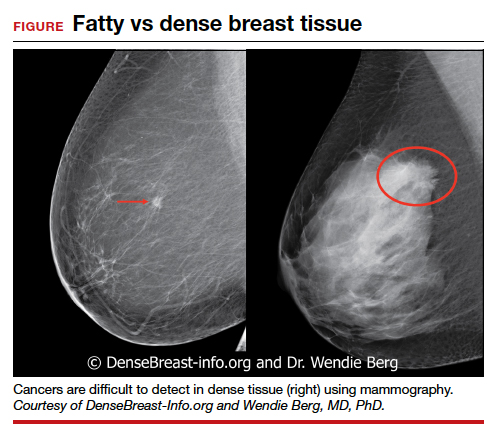

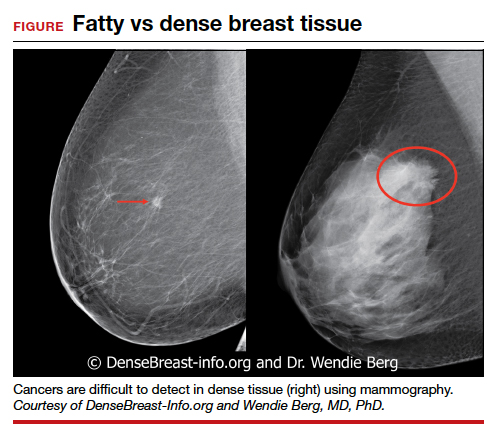

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Bharucha PP, Chiu KE, Francois FM, et al. Genetic testing and screening recommendations for patients with hereditary breast cancer. RadioGraphics. 2020;40:913-936.

- Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327-2333.

- Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3230-3235.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 625: management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:166]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750-751.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.

Since I practice at a large academic medical center, I have the opportunity to refer patients to our Breast Cancer Genetics Program because I may be limited on time for counseling in the office and do not want to miss salient details. With all of the information I have ascertained about the patient, I am able to determine and encourage appropriate screening and assure insurance coverage for adjunctive breast MRI when appropriate.

Continue to: Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost...

Consider how you order patients’ screening to reduce barriers and cost

4. How would you suggest reducing barriers when referring patients for supplemental screening, such as MRI for high-risk women or ultrasound for those with dense breasts? Would you prefer it if such screening could be performed without additional script/referral? How does insurance coverage factor in?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I would love for a screening mammogram with possible ultrasound, on one script, to be the norm. One of the centers that I work with accepts a script written this way. Further, when a patient receives screening at a freestanding facility as opposed to a hospital, the fee for the supplemental screening may be lower because they do not add on a facility fee.

Dr. Albright: We have an order in our electronic health record that allows for screening mammography but adds on diagnostic mammography/bilateral ultrasonography, if indicated by imaging. I am mostly ordering that option now for all of my screening patients; rarely have I had issues with insurance accepting that script. As for when ordering an MRI, I always try to ensure that I have done the patient’s personal risk assessment and included that lifetime breast cancer risk on the order. If the risk is 20% or higher, I typically do not have any insurance coverage issues. If I am ordering MRI as supplemental screening, I typically order the “Fast MRI” protocol that our center offers. This order incurs a $299 out-of-pocket cost for the patient. Any patient with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts on mammography should have this option, but it requires patient education, discussion with the provider, and an additional cost. I definitely think that insurers need to consider covering supplemental screening, since breast density is reportable in a majority of the US states and will soon be the national standard.

Pearls for guiding patients

5. How do you discuss breast density and the need for supplemental screening with your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I strongly feel that my patients need to know when a screening test has limited ability to do its job. This is the case with dense breasts. Visuals help; when discussing breast density, I like the images supplied by DenseBreast-info.org (FIGURE). I explain the two implications of dense tissue:

- First, dense tissue makes it harder to visualize cancers in the breast—the denser the breasts, the less likely the radiologist can pick up a cancer, so mammographic sensitivity for extremely dense breasts can be as low as 25% to 50%.

- Second, high breast density adds to the risk of developing breast cancer. I explain that supplemental screening will pick up additional cancers in women with dense breasts. For example, breast ultrasound will pick up about 2-3/1000 additional breast cancers per year and MRI or molecular breast imaging (MBI) will pick up much more, perhaps 10/1000.

MRI is more invasive than an ultrasound and uses gadolinium, and MBI has more radiation. Supplemental screening is not endorsed by ACOG’s most recent Committee Opinion from 2017; 4 however, patients may choose to have it done. This is where shared-decision making is important.

I strongly recommend that all women’s health care providers complete the CME course on the DenseBreast-info.org website. “ Breast Density: Why It Matters ” is a certified educational program for referring physicians that helps health care professionals learn about breast density, its associated risks, and how best to guide patients regarding breast cancer screening.

Continue to: Dr. Albright...

Dr. Albright: When I discuss breast density, I make sure that patients understand that their mammogram determines the density of their breast tissue. I review that in the higher density categories (heterogeneously dense or extremely dense), there is a higher risk of missing cancer, and that these categories are also associated with a higher risk of breast cancer. I also discuss the potential need for supplemental screening, for which my institution primarily offers Fast MRI. However, we can offer breast ultrasonography instead as an option, especially for those concerned about gadolinium exposure. Our center offers either of these supplemental screenings at a cost of $299. I also review the lack of coverage for supplemental screening by some insurance carriers, as both providers and patients may need to advocate for insurer coverage of adjunct studies.

Educational resources

6. What reference materials, illustrations, or other tools do you use to educate your patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: I frequently use handouts printed from the DenseBreast-info.org website, and there is now a brand new patient fact sheet that I have just started using. I also have an example of breast density categories from fatty replaced to extremely dense on my computer, and I am putting it on a new smart board.

Dr. Albright: The extensive resources available at DenseBreast-info.org can improve both patient and provider knowledge of these important issues, so I suggest patients visit that website, and I use many of the images and visuals to help explain breast density. I even use the materials from the website for educating my resident trainees on breast health and screening. ●

Nearly 16,000 children (up to age 19 years) face cancer-related treatment every year.1 For girls and young women, undergoing chest radiotherapy puts them at higher risk for secondary breast cancer. In fact, they have a 30% chance of developing such cancer by age 50—a risk that is similar to women with a BRCA1 mutation.2 Therefore, current recommendations for breast cancer screening among those who have undergone childhood chest radiation (≥20 Gy) are to begin annual mammography, with adjunct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), at age 25 years (or 8 years after chest radiotherapy).3

To determine the benefits and risks of these recommendations, as well as of similar strategies, Yeh and colleagues performed simulation modeling using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and two CISNET (Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network) models.4 For their study they targeted a cohort of female childhood cancer survivors having undergone chest radiotherapy and evaluated breast cancer screening with the following strategies:

- mammography plus MRI, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74

- MRI alone, starting at ages 25, 30, or 35 years and continuing to age 74.

They found that both strategies reduced the risk of breast cancer in the targeted cohort but that screening beginning at the earliest ages prevented most deaths. No screening at all was associated with a 10% to 11% lifetime risk of breast cancer, but mammography plus MRI beginning at age 25 reduced that risk by 56% to 71% depending on the model. Screening with MRI alone reduced mortality risk by 56% to 62%. When considering cost per quality adjusted life-year gained, the researchers found that screening beginning at age 30 to be the most cost-effective.4

Yeh and colleagues addressed concerns with mammography and radiation. Although they said the associated amount of radiation exposure is small, the use of mammography in women younger than age 30 is controversial—and not recommended by the American Cancer Society or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.5,6

Bottom line. Yeh and colleagues conclude that MRI screening, with or without mammography, beginning between the ages of 25 and 30 should be emphasized in screening guidelines. They note the importance of insurance coverage for MRI in those at risk for breast cancer due to childhood radiation exposure.4

References

- National Cancer Institute. How common is cancer in children? https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescentcancers-fact-sheet#how-common-is-cancer-in-children. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2217- 2223.

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. http:// www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:331-341.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75-89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2020.

If your ObGyn practices are anything like ours, every time there is news coverage of a study regarding mammography or about efforts to pass a breast density inform law, your phone rings with patient calls. In fact, every density inform law enacted in the United States, except for in Illinois, directs patients to their referring provider—generally their ObGyn—to discuss the screening and risk implications of dense breast tissue.

The steady increased awareness of breast density means that we, as ObGyns and other primary care providers (PCPs), have additional responsibilities in managing the breast health of our patients. This includes guiding discussions with patients about what breast density means and whether supplemental screening beyond mammography might be beneficial.

As members of the Medical Advisory Board for DenseBreast-info.org (an online educational resource dedicated to providing breast density information to patients and health care professionals), we are aware of the growing body of evidence demonstrating improved detection of early breast cancer using supplemental screening in dense breasts. However, we know that there is confusion among clinicians about how and when to facilitate tailored screening for women with dense breasts or other breast cancer risk factors. Here we answer 6 questions focusing on how to navigate patient discussions around the topic and the best way to collaborate with radiologists to improve breast care for patients.

Play an active role

1. What role should ObGyns and PCPs play in women’s breast health?

Elizabeth Etkin-Kramer, MD: I am a firm believer that ObGyns and all women’s health providers should be able to assess their patients’ risk of breast cancer and explain the process for managing this risk with their patients. This explanation includes the clinical implications of breast density and when supplemental screening should be employed. It is also important for providers to know when to offer genetic testing and when a patient’s personal or family history indicates supplemental screening with breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

DaCarla M. Albright, MD: I absolutely agree that PCPs, ObGyns, and family practitioners should spend the time to be educated about breast density and supplemental screening options. While the exact role providers play in managing patients’ breast health may vary depending on the practice type or location, the need for knowledge and comfort when talking with patients to help them make informed decisions is critical. Breast health and screening, including the importance of breast density, happen to be a particular interest of mine. I have participated in educational webinars, invited lectures, and breast cancer awareness media events on this topic in the past.

Continue to: Join forces with imaging centers...

Join forces with imaging centers

2. How can ObGyns and radiologists collaborate most effectively to use screening results to personalize breast care for patients?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important to have a close relationship with the radiologists that read our patients’ mammograms. We need to be able to easily contact the radiologist and quickly get clarification on a patient’s report or discuss next steps. Imaging centers should consider running outreach programs to educate their referring providers on how to risk assess, with this assessment inclusive of breast density. Dinner lectures or grand round meetings are effective to facilitate communication between the radiology community and the ObGyn community. Finally, as we all know, supplemental screening is often subject to copays and deductibles per insurance coverage. If advocacy groups, who are working to eliminate these types of costs, cannot get insurers to waive these payments, we need a less expensive self-pay option.

Dr. Albright: I definitely have and encourage an open line of communication between my practice and breast radiology, as well as our breast surgeons and cancer center to set up consultations as needed. We also invite our radiologists as guests to monthly practice meetings or grand rounds within our department to further improve access and open communication, as this environment is one in which greater provider education on density and adjunctive screening can be achieved.

Know when to refer a high-risk patient

3. Most ObGyns routinely collect family history and perform formal risk assessment. What do you need to know about referring patients to a high-risk program?

Dr. Etkin-Kramer: It is important as ObGyns to be knowledgeable about breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for cancer susceptibility genes. Our patients expect that of us. I am comfortable doing risk assessment in my office, but I sometimes refer to other specialists in the community if the patient needs additional counseling. For risk assessment, I look at family and personal history, breast density, and other factors that might lead me to believe the patient might carry a hereditary cancer susceptibility gene, including Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.1 When indicated, I check lifetime as well as short-term (5- to 10-year) risk, usually using Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) or Tyrer-Cuzick/International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) models, as these include breast density.

I discuss risk-reducing medications. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends these agents if my patient’s 5-year risk of breast cancer is 1.67% or greater, and I strongly recommend chemoprevention when the patient’s 5-year BCSC risk exceeds 3%, provided likely benefits exceed risks.2,3 I discuss adding screening breast MRI if lifetime risk by Tyrer-Cuzick exceeds 20%. (Note that Gail and BCSC models are not recommended to be used to determine risk for purposes of supplemental screening with MRI as they do not consider paternal family history nor age of relatives at diagnosis.)

Dr. Albright: ObGyns should be able to ascertain a pertinent history and identify patients at risk for breast cancer based on their personal history, family history, and breast imaging/biopsy history, if relevant. We also need to improve our discussions of supplemental screening for patients who have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breast tissue. I sense that some ObGyns may rely heavily on the radiologist to suggest supplemental screening, but patients actually look to ObGyns as their providers to have this knowledge and give them direction.