User login

Climate Change, Climate Anxiety, Climate Hope

Clinical Case: Sol is a 10 year-old cisgender White girl who appears sad at her annual well visit. On further inquiry she describes that her father is angry that there is no snow, her mother keeps talking about the forests disappearing, and local flooding closed down her favorite family restaurant for good. She is worried “the planet is in trouble and there’s nothing we can do” so much that she gets stomachaches when she thinks about it.

Climate Anxiety

Climate change is a complex phenomenon that has been subject to decades of political disagreement. Lobbying by groups like the fossil fuel industry, state legislation to implement recycling, oil spills and pollution disasters, and outspoken icons like former US Vice President Al Gore and Swedish activist Greta Thunberg have kept the climate crisis a hot topic. What was once a slow burn has begun to boil as climate-related disasters occur — wildfires, droughts, floods, and increasingly powerful and frequent severe weather events — alongside increasing temperatures globally. With heroic efforts, the UN-convened Paris Agreement was adopted by 196 nations in 2015 with ambitious goals to reduce global greenhouse emissions and limit Earth’s rising temperature.1 Yet doomsday headlines on this topic remain a regular occurrence.

Between sensationalized news coverage, political controversy, and international disasters, it is no wonder some youth are overwhelmed. .2 Direct effects could include a family losing their home to flooding or wildfires, resulting in post-traumatic stress symptoms or an anxiety disorder. Indirect effects might include a drought that results in loss of agricultural income leading to a forced migration, family stress and/or separation, and disordered substance use.

Add to these direct and indirect effects the cultural and media pressures, such as frequent debate about the consequences of failure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030,3 and youth can encounter a sense of existential dread that intersects squarely with their developmental trajectory. “Climate anxiety,” also called eco-anxiety or solastalgia, refers to “distress about climate change and its impacts on the landscape and human existence.”4 Eco-anxiety is not a formal psychiatric diagnosis and is not found in the DSM-5-TR.

In practice, existential climate-centered fears range from worrying about what to do to help with the climate crisis all the way to being overwhelmed about humanity’s future to the point of dysfunction. Some argue that this is not pathological, but rather a practical response to real-world phenomena.5 An international survey of youth found 59% were “very or extremely” worried about climate change with a mix of associated emotions, and almost half described eco-anxiety as something that affects their daily functioning.6 The climate crisis often amplifies the inequities already experienced by youth from historically marginalized groups.

Managing Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety presents with many of the typical features of other anxieties. These include worries that cycle repetitively and intrusively through the mind, somatic distress such as headaches or stomachaches, and avoidance of things that remind one of the uncertainty and distress associated with climate change. Because the climate crisis is so global and complex, hopelessness and fatigue are not uncommon.

However, climate anxiety can often be ameliorated with the typical approaches to treating anxiety. Borrowing from cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based interventions, many recommendations have been offered to help with eco-anxiety. External validation of youth’s concerns and fears is a starting point that might build a teen’s capacity to tolerate distressing emotions about global warming.

Once reactions to climate change are acknowledged and accepted, space is created for reflection. This might include a balance of hope and pragmatic action. For example, renewable energy sources have made up an increasing share of the market over time with the world adding 50% more renewable capacity in 2023.7 Seventy-two percent of Americans acknowledge global warming, 75% feel schools should teach about consequences and solutions for global warming, and 79% support investment in renewable energy.8

Climate activism itself has been shown to buffer climate anxiety, particularly when implemented collectively rather than individually.4 Nature connectedness, or cognitive and emotional connections with nature, not only has many direct mental health benefits, but is also associated with climate activism.9 Many other integrative interventions can improve well-being while reducing ecological harm. Nutrition, physical activity, mindfulness, and sleep are youth mental health interventions with a strong evidence base that also reduce the carbon footprint and pollution attributable to psychiatric pharmaceuticals. Moreover, these climate-friendly interventions can improve family-connectedness, thus boosting resilience.

Without needing to become eco-warriors, healthcare providers can model sustainable practices while caring for patients. This might include having more plants in the office, recycling and composting at work, adding solar panels to the rooftop, or joining local parks prescription programs (see mygreendoctor.org, a nonprofit owned by the Florida Medical Association).

Next Steps

Sol is relieved to hear that many kids her age share her family’s concerns. A conversation about how to manage distressing emotions and physical feelings leads to a referral for brief cognitive behavioral interventions. Her parents join your visit to hear her concerns. They want to begin a family plan for climate action. You recommend the books How to Change Everything: The Young Human’s Guide to Protecting the Planet and Each Other by Naomi Klein and The Parents’ Guide to Climate Revolution: 100 Ways to Build a Fossil-Free Future, Raise Empowered Kids, and Still Get a Good Night’s Sleep by Mary DeMocker.

Dr. Rosenfeld is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Maizland L. Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements.

2. van Nieuwenhuizen A et al. The effects of climate change on child and adolescent mental health: Clinical considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021 Dec 7;23(12):88. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01296-y.

3. Window to Reach Climate Goals ‘Rapidly Closing’, UN Report Warns. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/09/1140527.

4. Schwartz SEO et al. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr Psychol. 2022 Feb 28:1-14. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6.

5. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12:7836. doi: 10.3390/su12197836.

6. Hickman C et al. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Dec;5(12):e863-e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

7. IEA (2021), Global Energy Review 2021, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021/renewables.

8. Marlon J et al. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2023. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/.

9. Thomson EE, Roach SP. The Relationships Among Nature Connectedness, Climate Anxiety, Climate Action, Climate Knowledge, and Mental Health. Front Psychol. 2023 Nov 15:14:1241400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1241400.

Clinical Case: Sol is a 10 year-old cisgender White girl who appears sad at her annual well visit. On further inquiry she describes that her father is angry that there is no snow, her mother keeps talking about the forests disappearing, and local flooding closed down her favorite family restaurant for good. She is worried “the planet is in trouble and there’s nothing we can do” so much that she gets stomachaches when she thinks about it.

Climate Anxiety

Climate change is a complex phenomenon that has been subject to decades of political disagreement. Lobbying by groups like the fossil fuel industry, state legislation to implement recycling, oil spills and pollution disasters, and outspoken icons like former US Vice President Al Gore and Swedish activist Greta Thunberg have kept the climate crisis a hot topic. What was once a slow burn has begun to boil as climate-related disasters occur — wildfires, droughts, floods, and increasingly powerful and frequent severe weather events — alongside increasing temperatures globally. With heroic efforts, the UN-convened Paris Agreement was adopted by 196 nations in 2015 with ambitious goals to reduce global greenhouse emissions and limit Earth’s rising temperature.1 Yet doomsday headlines on this topic remain a regular occurrence.

Between sensationalized news coverage, political controversy, and international disasters, it is no wonder some youth are overwhelmed. .2 Direct effects could include a family losing their home to flooding or wildfires, resulting in post-traumatic stress symptoms or an anxiety disorder. Indirect effects might include a drought that results in loss of agricultural income leading to a forced migration, family stress and/or separation, and disordered substance use.

Add to these direct and indirect effects the cultural and media pressures, such as frequent debate about the consequences of failure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030,3 and youth can encounter a sense of existential dread that intersects squarely with their developmental trajectory. “Climate anxiety,” also called eco-anxiety or solastalgia, refers to “distress about climate change and its impacts on the landscape and human existence.”4 Eco-anxiety is not a formal psychiatric diagnosis and is not found in the DSM-5-TR.

In practice, existential climate-centered fears range from worrying about what to do to help with the climate crisis all the way to being overwhelmed about humanity’s future to the point of dysfunction. Some argue that this is not pathological, but rather a practical response to real-world phenomena.5 An international survey of youth found 59% were “very or extremely” worried about climate change with a mix of associated emotions, and almost half described eco-anxiety as something that affects their daily functioning.6 The climate crisis often amplifies the inequities already experienced by youth from historically marginalized groups.

Managing Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety presents with many of the typical features of other anxieties. These include worries that cycle repetitively and intrusively through the mind, somatic distress such as headaches or stomachaches, and avoidance of things that remind one of the uncertainty and distress associated with climate change. Because the climate crisis is so global and complex, hopelessness and fatigue are not uncommon.

However, climate anxiety can often be ameliorated with the typical approaches to treating anxiety. Borrowing from cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based interventions, many recommendations have been offered to help with eco-anxiety. External validation of youth’s concerns and fears is a starting point that might build a teen’s capacity to tolerate distressing emotions about global warming.

Once reactions to climate change are acknowledged and accepted, space is created for reflection. This might include a balance of hope and pragmatic action. For example, renewable energy sources have made up an increasing share of the market over time with the world adding 50% more renewable capacity in 2023.7 Seventy-two percent of Americans acknowledge global warming, 75% feel schools should teach about consequences and solutions for global warming, and 79% support investment in renewable energy.8

Climate activism itself has been shown to buffer climate anxiety, particularly when implemented collectively rather than individually.4 Nature connectedness, or cognitive and emotional connections with nature, not only has many direct mental health benefits, but is also associated with climate activism.9 Many other integrative interventions can improve well-being while reducing ecological harm. Nutrition, physical activity, mindfulness, and sleep are youth mental health interventions with a strong evidence base that also reduce the carbon footprint and pollution attributable to psychiatric pharmaceuticals. Moreover, these climate-friendly interventions can improve family-connectedness, thus boosting resilience.

Without needing to become eco-warriors, healthcare providers can model sustainable practices while caring for patients. This might include having more plants in the office, recycling and composting at work, adding solar panels to the rooftop, or joining local parks prescription programs (see mygreendoctor.org, a nonprofit owned by the Florida Medical Association).

Next Steps

Sol is relieved to hear that many kids her age share her family’s concerns. A conversation about how to manage distressing emotions and physical feelings leads to a referral for brief cognitive behavioral interventions. Her parents join your visit to hear her concerns. They want to begin a family plan for climate action. You recommend the books How to Change Everything: The Young Human’s Guide to Protecting the Planet and Each Other by Naomi Klein and The Parents’ Guide to Climate Revolution: 100 Ways to Build a Fossil-Free Future, Raise Empowered Kids, and Still Get a Good Night’s Sleep by Mary DeMocker.

Dr. Rosenfeld is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Maizland L. Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements.

2. van Nieuwenhuizen A et al. The effects of climate change on child and adolescent mental health: Clinical considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021 Dec 7;23(12):88. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01296-y.

3. Window to Reach Climate Goals ‘Rapidly Closing’, UN Report Warns. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/09/1140527.

4. Schwartz SEO et al. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr Psychol. 2022 Feb 28:1-14. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6.

5. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12:7836. doi: 10.3390/su12197836.

6. Hickman C et al. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Dec;5(12):e863-e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

7. IEA (2021), Global Energy Review 2021, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021/renewables.

8. Marlon J et al. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2023. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/.

9. Thomson EE, Roach SP. The Relationships Among Nature Connectedness, Climate Anxiety, Climate Action, Climate Knowledge, and Mental Health. Front Psychol. 2023 Nov 15:14:1241400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1241400.

Clinical Case: Sol is a 10 year-old cisgender White girl who appears sad at her annual well visit. On further inquiry she describes that her father is angry that there is no snow, her mother keeps talking about the forests disappearing, and local flooding closed down her favorite family restaurant for good. She is worried “the planet is in trouble and there’s nothing we can do” so much that she gets stomachaches when she thinks about it.

Climate Anxiety

Climate change is a complex phenomenon that has been subject to decades of political disagreement. Lobbying by groups like the fossil fuel industry, state legislation to implement recycling, oil spills and pollution disasters, and outspoken icons like former US Vice President Al Gore and Swedish activist Greta Thunberg have kept the climate crisis a hot topic. What was once a slow burn has begun to boil as climate-related disasters occur — wildfires, droughts, floods, and increasingly powerful and frequent severe weather events — alongside increasing temperatures globally. With heroic efforts, the UN-convened Paris Agreement was adopted by 196 nations in 2015 with ambitious goals to reduce global greenhouse emissions and limit Earth’s rising temperature.1 Yet doomsday headlines on this topic remain a regular occurrence.

Between sensationalized news coverage, political controversy, and international disasters, it is no wonder some youth are overwhelmed. .2 Direct effects could include a family losing their home to flooding or wildfires, resulting in post-traumatic stress symptoms or an anxiety disorder. Indirect effects might include a drought that results in loss of agricultural income leading to a forced migration, family stress and/or separation, and disordered substance use.

Add to these direct and indirect effects the cultural and media pressures, such as frequent debate about the consequences of failure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030,3 and youth can encounter a sense of existential dread that intersects squarely with their developmental trajectory. “Climate anxiety,” also called eco-anxiety or solastalgia, refers to “distress about climate change and its impacts on the landscape and human existence.”4 Eco-anxiety is not a formal psychiatric diagnosis and is not found in the DSM-5-TR.

In practice, existential climate-centered fears range from worrying about what to do to help with the climate crisis all the way to being overwhelmed about humanity’s future to the point of dysfunction. Some argue that this is not pathological, but rather a practical response to real-world phenomena.5 An international survey of youth found 59% were “very or extremely” worried about climate change with a mix of associated emotions, and almost half described eco-anxiety as something that affects their daily functioning.6 The climate crisis often amplifies the inequities already experienced by youth from historically marginalized groups.

Managing Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety presents with many of the typical features of other anxieties. These include worries that cycle repetitively and intrusively through the mind, somatic distress such as headaches or stomachaches, and avoidance of things that remind one of the uncertainty and distress associated with climate change. Because the climate crisis is so global and complex, hopelessness and fatigue are not uncommon.

However, climate anxiety can often be ameliorated with the typical approaches to treating anxiety. Borrowing from cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based interventions, many recommendations have been offered to help with eco-anxiety. External validation of youth’s concerns and fears is a starting point that might build a teen’s capacity to tolerate distressing emotions about global warming.

Once reactions to climate change are acknowledged and accepted, space is created for reflection. This might include a balance of hope and pragmatic action. For example, renewable energy sources have made up an increasing share of the market over time with the world adding 50% more renewable capacity in 2023.7 Seventy-two percent of Americans acknowledge global warming, 75% feel schools should teach about consequences and solutions for global warming, and 79% support investment in renewable energy.8

Climate activism itself has been shown to buffer climate anxiety, particularly when implemented collectively rather than individually.4 Nature connectedness, or cognitive and emotional connections with nature, not only has many direct mental health benefits, but is also associated with climate activism.9 Many other integrative interventions can improve well-being while reducing ecological harm. Nutrition, physical activity, mindfulness, and sleep are youth mental health interventions with a strong evidence base that also reduce the carbon footprint and pollution attributable to psychiatric pharmaceuticals. Moreover, these climate-friendly interventions can improve family-connectedness, thus boosting resilience.

Without needing to become eco-warriors, healthcare providers can model sustainable practices while caring for patients. This might include having more plants in the office, recycling and composting at work, adding solar panels to the rooftop, or joining local parks prescription programs (see mygreendoctor.org, a nonprofit owned by the Florida Medical Association).

Next Steps

Sol is relieved to hear that many kids her age share her family’s concerns. A conversation about how to manage distressing emotions and physical feelings leads to a referral for brief cognitive behavioral interventions. Her parents join your visit to hear her concerns. They want to begin a family plan for climate action. You recommend the books How to Change Everything: The Young Human’s Guide to Protecting the Planet and Each Other by Naomi Klein and The Parents’ Guide to Climate Revolution: 100 Ways to Build a Fossil-Free Future, Raise Empowered Kids, and Still Get a Good Night’s Sleep by Mary DeMocker.

Dr. Rosenfeld is associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

1. Maizland L. Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements.

2. van Nieuwenhuizen A et al. The effects of climate change on child and adolescent mental health: Clinical considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021 Dec 7;23(12):88. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01296-y.

3. Window to Reach Climate Goals ‘Rapidly Closing’, UN Report Warns. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/09/1140527.

4. Schwartz SEO et al. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr Psychol. 2022 Feb 28:1-14. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6.

5. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12:7836. doi: 10.3390/su12197836.

6. Hickman C et al. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Dec;5(12):e863-e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

7. IEA (2021), Global Energy Review 2021, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021/renewables.

8. Marlon J et al. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2023. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/.

9. Thomson EE, Roach SP. The Relationships Among Nature Connectedness, Climate Anxiety, Climate Action, Climate Knowledge, and Mental Health. Front Psychol. 2023 Nov 15:14:1241400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1241400.

Similar Outcomes With Labetalol, Nifedipine for Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy

Treatment for chronic hypertension in pregnancy with labetalol showed no significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes, compared with treatment with nifedipine, new research indicates.

The open-label, multicenter, randomized CHAP (Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy) trial showed that treating mild chronic hypertension was better than delaying treatment until severe hypertension developed, but still unclear was whether, or to what extent, the choice of first-line treatment affected outcomes.

Researchers, led by Ayodeji A. Sanusi, MD, MPH, with the Division of Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, conducted a secondary analysis of CHAP to compare the primary treatments. Mild chronic hypertension in the study was defined as blood pressure of 140-159/90-104 mmHg before 20 weeks of gestation.

Three Comparisons

Three comparisons were performed in 2292 participants based on medications prescribed at enrollment: 720 (31.4%) received labetalol; 417 (18.2%) initially received nifedipine; and 1155 (50.4%) had standard care. Labetalol was compared with standard care; nifedipine was compared with standard care; and labetalol was compared with nifedipine.

The primary outcome was occurrence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features; preterm birth before 35 weeks of gestation; placental abruption; or fetal or neonatal death. The key secondary outcome was a small-for-gestational age neonate. Researchers also compared adverse effects between groups.

Among the results were the following:

- The primary outcome occurred in 30.1% in the labetalol group; 31.2% in the nifedipine group; and 37% in the standard care group.

- Risk of the primary outcome was lower among those receiving treatment. For labetalol vs standard care, the adjusted relative risk (RR) was 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.72-0.94. For nifedipine vs standard care, the adjusted RR was 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99. There was no significant difference in risk when labetalol was compared with nifedipine (adjusted RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.82-1.18).

- There were no significant differences in numbers of small-for-gestational age neonates or serious adverse events between those who received labetalol and those using nifedipine.

Any adverse events were significantly more common with nifedipine, compared with labetalol (35.7% vs 28.3%, P = .009), and with nifedipine, compared with standard care (35.7% vs 26.3%, P = .0003). Adverse event rates were not significantly higher with labetalol when compared with standard care (28.3% vs 26.3%, P = .34). The most frequently reported adverse events were headache, medication intolerance, dizziness, nausea, dyspepsia, neonatal jaundice, and vomiting.

“Thus, labetalol compared with nifedipine appeared to have fewer adverse events and to be better tolerated,” the authors write. They note that labetalol, a third-generation mixed alpha- and beta-adrenergic antagonist, is contraindicated for those who have obstructive pulmonary disease and nifedipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is contraindicated in people with tachycardia.

The authors write that their results align with other studies that have not found differences between labetalol and nifedipine. “[O]ur findings support the use of either labetalol or nifedipine as initial first-line agents for the management of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and other perinatal outcomes with no increased risk of fetal harm,” the authors write.

Dr. Sanusi reports no relevant financial relationships. Full coauthor disclosures are available with the full text of the paper.

Treatment for chronic hypertension in pregnancy with labetalol showed no significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes, compared with treatment with nifedipine, new research indicates.

The open-label, multicenter, randomized CHAP (Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy) trial showed that treating mild chronic hypertension was better than delaying treatment until severe hypertension developed, but still unclear was whether, or to what extent, the choice of first-line treatment affected outcomes.

Researchers, led by Ayodeji A. Sanusi, MD, MPH, with the Division of Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, conducted a secondary analysis of CHAP to compare the primary treatments. Mild chronic hypertension in the study was defined as blood pressure of 140-159/90-104 mmHg before 20 weeks of gestation.

Three Comparisons

Three comparisons were performed in 2292 participants based on medications prescribed at enrollment: 720 (31.4%) received labetalol; 417 (18.2%) initially received nifedipine; and 1155 (50.4%) had standard care. Labetalol was compared with standard care; nifedipine was compared with standard care; and labetalol was compared with nifedipine.

The primary outcome was occurrence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features; preterm birth before 35 weeks of gestation; placental abruption; or fetal or neonatal death. The key secondary outcome was a small-for-gestational age neonate. Researchers also compared adverse effects between groups.

Among the results were the following:

- The primary outcome occurred in 30.1% in the labetalol group; 31.2% in the nifedipine group; and 37% in the standard care group.

- Risk of the primary outcome was lower among those receiving treatment. For labetalol vs standard care, the adjusted relative risk (RR) was 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.72-0.94. For nifedipine vs standard care, the adjusted RR was 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99. There was no significant difference in risk when labetalol was compared with nifedipine (adjusted RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.82-1.18).

- There were no significant differences in numbers of small-for-gestational age neonates or serious adverse events between those who received labetalol and those using nifedipine.

Any adverse events were significantly more common with nifedipine, compared with labetalol (35.7% vs 28.3%, P = .009), and with nifedipine, compared with standard care (35.7% vs 26.3%, P = .0003). Adverse event rates were not significantly higher with labetalol when compared with standard care (28.3% vs 26.3%, P = .34). The most frequently reported adverse events were headache, medication intolerance, dizziness, nausea, dyspepsia, neonatal jaundice, and vomiting.

“Thus, labetalol compared with nifedipine appeared to have fewer adverse events and to be better tolerated,” the authors write. They note that labetalol, a third-generation mixed alpha- and beta-adrenergic antagonist, is contraindicated for those who have obstructive pulmonary disease and nifedipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is contraindicated in people with tachycardia.

The authors write that their results align with other studies that have not found differences between labetalol and nifedipine. “[O]ur findings support the use of either labetalol or nifedipine as initial first-line agents for the management of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and other perinatal outcomes with no increased risk of fetal harm,” the authors write.

Dr. Sanusi reports no relevant financial relationships. Full coauthor disclosures are available with the full text of the paper.

Treatment for chronic hypertension in pregnancy with labetalol showed no significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes, compared with treatment with nifedipine, new research indicates.

The open-label, multicenter, randomized CHAP (Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy) trial showed that treating mild chronic hypertension was better than delaying treatment until severe hypertension developed, but still unclear was whether, or to what extent, the choice of first-line treatment affected outcomes.

Researchers, led by Ayodeji A. Sanusi, MD, MPH, with the Division of Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, conducted a secondary analysis of CHAP to compare the primary treatments. Mild chronic hypertension in the study was defined as blood pressure of 140-159/90-104 mmHg before 20 weeks of gestation.

Three Comparisons

Three comparisons were performed in 2292 participants based on medications prescribed at enrollment: 720 (31.4%) received labetalol; 417 (18.2%) initially received nifedipine; and 1155 (50.4%) had standard care. Labetalol was compared with standard care; nifedipine was compared with standard care; and labetalol was compared with nifedipine.

The primary outcome was occurrence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features; preterm birth before 35 weeks of gestation; placental abruption; or fetal or neonatal death. The key secondary outcome was a small-for-gestational age neonate. Researchers also compared adverse effects between groups.

Among the results were the following:

- The primary outcome occurred in 30.1% in the labetalol group; 31.2% in the nifedipine group; and 37% in the standard care group.

- Risk of the primary outcome was lower among those receiving treatment. For labetalol vs standard care, the adjusted relative risk (RR) was 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.72-0.94. For nifedipine vs standard care, the adjusted RR was 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99. There was no significant difference in risk when labetalol was compared with nifedipine (adjusted RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.82-1.18).

- There were no significant differences in numbers of small-for-gestational age neonates or serious adverse events between those who received labetalol and those using nifedipine.

Any adverse events were significantly more common with nifedipine, compared with labetalol (35.7% vs 28.3%, P = .009), and with nifedipine, compared with standard care (35.7% vs 26.3%, P = .0003). Adverse event rates were not significantly higher with labetalol when compared with standard care (28.3% vs 26.3%, P = .34). The most frequently reported adverse events were headache, medication intolerance, dizziness, nausea, dyspepsia, neonatal jaundice, and vomiting.

“Thus, labetalol compared with nifedipine appeared to have fewer adverse events and to be better tolerated,” the authors write. They note that labetalol, a third-generation mixed alpha- and beta-adrenergic antagonist, is contraindicated for those who have obstructive pulmonary disease and nifedipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is contraindicated in people with tachycardia.

The authors write that their results align with other studies that have not found differences between labetalol and nifedipine. “[O]ur findings support the use of either labetalol or nifedipine as initial first-line agents for the management of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and other perinatal outcomes with no increased risk of fetal harm,” the authors write.

Dr. Sanusi reports no relevant financial relationships. Full coauthor disclosures are available with the full text of the paper.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Which Surgeries Drive the Most Opioid Prescriptions in Youth?

TOPLINE:

according to a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers analyzed national commercial and Medicaid claims from December 2020 to November 2021 in children aged 0-21 years.

- More than 200,000 procedures were included in the study.

- For each type of surgery, researchers calculated the total amount of opioids given within 3 days of discharge, measured in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs).

TAKEAWAY:

- In children up to age 11 years, three procedures accounted for 59.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (50.3%), open treatment of upper extremity fracture (5.3%), and removal of deep implants (3.5%).

- In patients aged 12-21 years, three procedures accounted for 33.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (12.7%), knee arthroscopy (12.6%), and analgesia after cesarean delivery (7.8%).

- Refill rates for children were all 1% or less.

- Refill rates for adolescents ranged from 2.3% to 9.6%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Targeting these procedures in opioid stewardship initiatives could help minimize the risks of opioid prescribing while maintaining effective postoperative pain control,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, and was published in Pediatrics

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers analyzed opioids prescribed only after major surgeries. The sources of data used in the analysis may not fully represent all pediatric patients.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chua reported consulting fees from the US Department of Justice and the Benter Foundation outside the submitted work. Other authors reported a variety of financial interests, including consulting for the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

according to a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers analyzed national commercial and Medicaid claims from December 2020 to November 2021 in children aged 0-21 years.

- More than 200,000 procedures were included in the study.

- For each type of surgery, researchers calculated the total amount of opioids given within 3 days of discharge, measured in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs).

TAKEAWAY:

- In children up to age 11 years, three procedures accounted for 59.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (50.3%), open treatment of upper extremity fracture (5.3%), and removal of deep implants (3.5%).

- In patients aged 12-21 years, three procedures accounted for 33.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (12.7%), knee arthroscopy (12.6%), and analgesia after cesarean delivery (7.8%).

- Refill rates for children were all 1% or less.

- Refill rates for adolescents ranged from 2.3% to 9.6%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Targeting these procedures in opioid stewardship initiatives could help minimize the risks of opioid prescribing while maintaining effective postoperative pain control,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, and was published in Pediatrics

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers analyzed opioids prescribed only after major surgeries. The sources of data used in the analysis may not fully represent all pediatric patients.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chua reported consulting fees from the US Department of Justice and the Benter Foundation outside the submitted work. Other authors reported a variety of financial interests, including consulting for the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

according to a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers analyzed national commercial and Medicaid claims from December 2020 to November 2021 in children aged 0-21 years.

- More than 200,000 procedures were included in the study.

- For each type of surgery, researchers calculated the total amount of opioids given within 3 days of discharge, measured in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs).

TAKEAWAY:

- In children up to age 11 years, three procedures accounted for 59.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (50.3%), open treatment of upper extremity fracture (5.3%), and removal of deep implants (3.5%).

- In patients aged 12-21 years, three procedures accounted for 33.1% of MMEs: Tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (12.7%), knee arthroscopy (12.6%), and analgesia after cesarean delivery (7.8%).

- Refill rates for children were all 1% or less.

- Refill rates for adolescents ranged from 2.3% to 9.6%.

IN PRACTICE:

“Targeting these procedures in opioid stewardship initiatives could help minimize the risks of opioid prescribing while maintaining effective postoperative pain control,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, and was published in Pediatrics

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers analyzed opioids prescribed only after major surgeries. The sources of data used in the analysis may not fully represent all pediatric patients.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chua reported consulting fees from the US Department of Justice and the Benter Foundation outside the submitted work. Other authors reported a variety of financial interests, including consulting for the pharmaceutical industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neurofilament Light Chain Detects Early Chemotherapy-Related Neurotoxicity

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found Nfl levels increased in cancer patients following a first infusion of the medication paclitaxel and corresponded to neuropathy severity 6-12 months post-treatment, suggesting the blood protein may provide an early CIPN biomarker.

“Nfl after a single cycle could detect axonal degeneration,” said lead investigator Masarra Joda, a researcher and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in Australia. She added that “quantification of Nfl may provide a clinically useful marker of emerging neurotoxicity in patients vulnerable to CIPN.”

The findings were presented at the Peripheral Nerve Society (PNS) 2024 annual meeting.

Common, Burdensome Side Effect

A common side effect of chemotherapy, CIPN manifests as sensory neuropathy and causes degeneration of the peripheral axons. A protein biomarker of axonal degeneration, Nfl has previously been investigated as a way of identifying patients at risk of CIPN.

The goal of the current study was to identify the potential link between Nfl with neurophysiological markers of axon degeneration in patients receiving the neurotoxin chemotherapy paclitaxel.

The study included 93 cancer patients. All were assessed at the beginning, middle, and end of treatment. CIPN was assessed using blood samples of Nfl and the Total Neuropathy Score (TNS), the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) neuropathy scale, and patient-reported measures using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Module (EORTC-CIPN20).

Axonal degeneration was measured with neurophysiological tests including sural nerve compound sensory action potential (CSAP) for the lower limbs, and sensory median nerve CSAP, as well as stimulus threshold testing, for the upper limbs.

Almost all of study participants (97%) were female. The majority (66%) had breast cancer and 30% had gynecological cancer. Most (73%) were receiving a weekly regimen of paclitaxel, and the remainder were treated with taxanes plus platinum once every 3 weeks. By the end of treatment, 82% of the patients had developed CIPN, which was mild in 44% and moderate/severe in 38%.

Nfl levels increased significantly from baseline to after the first dose of chemotherapy (P < .001), “highlighting that nerve damage occurs from the very beginning of treatment,” senior investigator Susanna Park, PhD, told this news organization.

In addition, “patients with higher Nfl levels after a single paclitaxel treatment had greater neuropathy at the end of treatment (higher EORTC scores [P ≤ .026], and higher TNS scores [P ≤ .00]),” added Dr. Park, who is associate professor at the University of Sydney.

“Importantly, we also looked at long-term outcomes beyond the end of chemotherapy, because chronic neuropathy produces a significant burden in cancer survivors,” said Dr. Park.

“Among a total of 44 patients who completed the 6- to 12-month post-treatment follow-up, NfL levels after a single treatment were linked to severity of nerve damage quantified with neurophysiological tests, and greater Nfl levels at mid-treatment were correlated with worse patient and neurologically graded neuropathy at 6-12 months.”

Dr. Park said the results suggest that NfL may provide a biomarker of long-term axon damage and that Nfl assays “may enable clinicians to evaluate the risk of long-term toxicity early during paclitaxel treatment to hopefully provide clinically significant information to guide better treatment titration.”

Currently, she said, CIPN is a prominent cause of dose reduction and early chemotherapy cessation.

“For example, in early breast cancer around 25% of patients experience a dose reduction due to the severity of neuropathy symptoms.” But, she said, “there is no standardized way of identifying which patients are at risk of long-term neuropathy and therefore, may benefit more from dose reduction. In this setting, a biomarker such as Nfl could provide oncologists with more information about the risk of long-term toxicity and take that into account in dose decision-making.”

For some cancers, she added, there are multiple potential therapy options.

“A biomarker such as NfL could assist in determining risk-benefit profile in terms of switching to alternate therapies. However, further studies will be needed to fully define the utility of NfL as a biomarker of paclitaxel neuropathy.”

Promising Research

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Maryam Lustberg, MD, associate professor, director of the Center for Breast Cancer at Smilow Cancer Hospital and Yale Cancer Center, and chief of Breast Medical Oncology at Yale Cancer Center, in New Haven, Connecticut, said the study “builds on a body of work previously reported by others showing that neurofilament light chains as detected in the blood can be associated with early signs of neurotoxic injury.”

She added that the research “is promising, since existing clinical and patient-reported measures tend to under-detect chemotherapy-induced neuropathy until more permanent injury might have occurred.”

Dr. Lustberg, who is immediate past president of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, said future studies are needed before Nfl testing can be implemented in routine practice, but that “early detection will allow earlier initiation of supportive care strategies such as physical therapy and exercise, as well as dose modifications, which may be helpful for preventing permanent damage and improving quality of life.”

The investigators and Dr. Lustberg report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT PNS 2024

First-line Canakinumab Without Steroids Shows Effectiveness for Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

VIENNA — The interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) canakinumab provided control of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) without the use of glucocorticoids for up to a year in most study participants after three monthly injections.

In this study of 20 patients with newly diagnosed sJIA treated off glucocorticoids, fever was controlled after a single injection in all patients, and 16 patients reached the primary outcome of remission after three injections, said Gerd Horneff, MD, PhD, Asklepios Children’s Hospital, Sankt Augustin, Germany.

Results of this open-label study, called CANAKINUMAB FIRST, were presented as late-breaking findings at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2024 Annual Meeting.

“Steroid-free, first-line treatment with canakinumab led to sustained responses in most patients, with a considerable number achieving remission,” said Dr. Horneff, adding that the observation in this group is ongoing.

Building on Earlier Data

The efficacy of canakinumab was previously reported in anecdotal experiences and one small patient series published 10 years ago. Dr. Horneff noted that he has offered this drug off label to patients with challenging cases.

The objective was to evaluate canakinumab as a first-line monotherapy administered in the absence of glucocorticoids. The study was open to children aged 2-18 years with active sJIA/juvenile Still disease confirmed with published criteria. All were naive to biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as well as steroids.

The median age of the children was 8.4 years. A total of 60% were men. The median disease duration at the time of entry was 1.2 months. Most had fever (95%) and rash (80%) with high levels of inflammatory markers at baseline. The mean number of painful joints was 3.1, and the mean number of systemic manifestations was 2.8. No patient was without any systemic involvement, but four of the patients did not have any painful joints.

At enrollment, patients were scheduled to receive three injections of canakinumab at monthly intervals during an active treatment phase, after which they entered an observation phase lasting 40 weeks. In the event of nonresponse or flares in either phase, they were transitioned to usual care.

Symptoms Resolve After Single Injection

After the first injection, active joint disease and all systemic manifestations resolved in 16 (80%) of the 20 patients. Joint activity and systemic manifestations also remained controlled after the second and third injections in 16 of the 20 patients.

One patient in this series achieved inactive disease after a single injection but developed what appeared to be a treatment-related allergic reaction. He received no further treatment and was excluded from the study, although he is being followed separately.

“According to sJADAS [systemic JIA Disease Activity Score] criteria at month 3, 14 had inactive disease, three had minimal disease activity, and one patient had moderate disease activity,” Dr. Horneff said.

At week 24, or 3 months after the last injection, there was still no joint activity in 16 patients. Systemic manifestations remained controlled in 13 patients, but 1 patient by this point had a flare. Another flare occurred after this point, and other patients have not yet completed the 52-week observation period.

“Of the 10 patients who remained in the study and have completed the 52-week observation period, eight have had a drug-free remission,” Dr. Horneff said.

MAS Event Observed in One Patient

In addition to the allergic skin reaction, which was considered probably related to the study drug, there were three flares, one of which was a macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) event. The MAS occurred 8 weeks after the last injection, but it was managed successfully.

Of 30 infections that developed during the observation period, 18 involved the upper airway. All were treated successfully. There were also two injection-site reactions and one case of cytopenia.

Among the studies planned for follow-up, investigators will examine genomic and gene activation in relation to disease activity and the effect of canakinumab.

Comoderator of the abstract session and chair of the EULAR 2024 Abstract Selection Committee, Christian Dejaco, MD, PhD, a consultant rheumatologist and associate professor at the Medical University of Graz in Graz, Austria, suggested that these are highly encouraging data for a disease that does not currently have any approved therapies. Clearly, larger studies with a longer follow-up period are needed, but he pointed out that phase 3 trials in a rare disease like sJIA are challenging.

Because of the limited number of cases, “it will be difficult to conduct a placebo-controlled trial,” he pointed out. However, he hopes this study will provide the basis for larger studies and sufficient data to lead to an indication for this therapy.

In the meantime, he also believes that these data are likely to support empirical use in a difficult disease, even in advance of formal regulatory approval.

“We heard that canakinumab is already being used off label in JIA, and these data might encourage more of that,” he said.

Dr. Horneff reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobe. Dr. Dejaco reported no potential conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA — The interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) canakinumab provided control of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) without the use of glucocorticoids for up to a year in most study participants after three monthly injections.

In this study of 20 patients with newly diagnosed sJIA treated off glucocorticoids, fever was controlled after a single injection in all patients, and 16 patients reached the primary outcome of remission after three injections, said Gerd Horneff, MD, PhD, Asklepios Children’s Hospital, Sankt Augustin, Germany.

Results of this open-label study, called CANAKINUMAB FIRST, were presented as late-breaking findings at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2024 Annual Meeting.

“Steroid-free, first-line treatment with canakinumab led to sustained responses in most patients, with a considerable number achieving remission,” said Dr. Horneff, adding that the observation in this group is ongoing.

Building on Earlier Data

The efficacy of canakinumab was previously reported in anecdotal experiences and one small patient series published 10 years ago. Dr. Horneff noted that he has offered this drug off label to patients with challenging cases.

The objective was to evaluate canakinumab as a first-line monotherapy administered in the absence of glucocorticoids. The study was open to children aged 2-18 years with active sJIA/juvenile Still disease confirmed with published criteria. All were naive to biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as well as steroids.

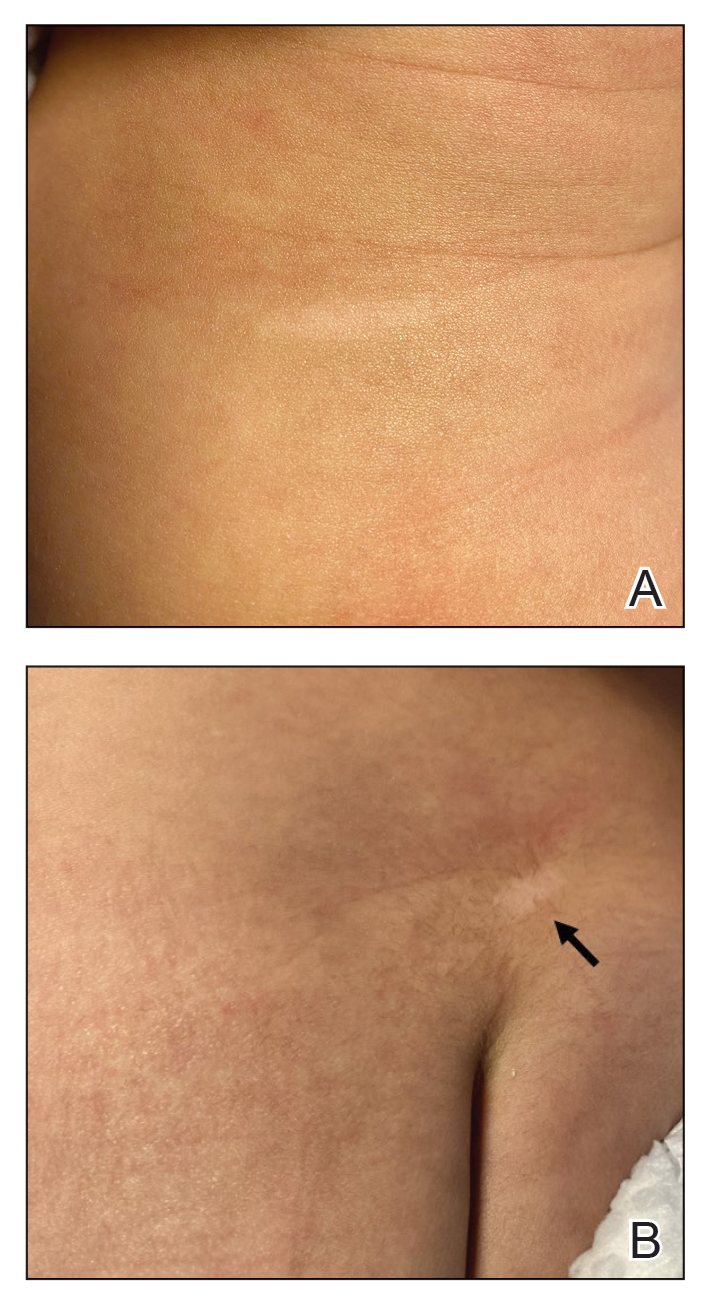

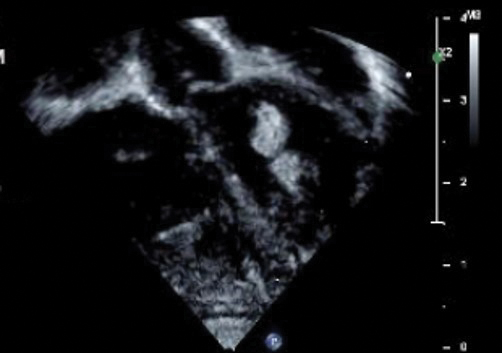

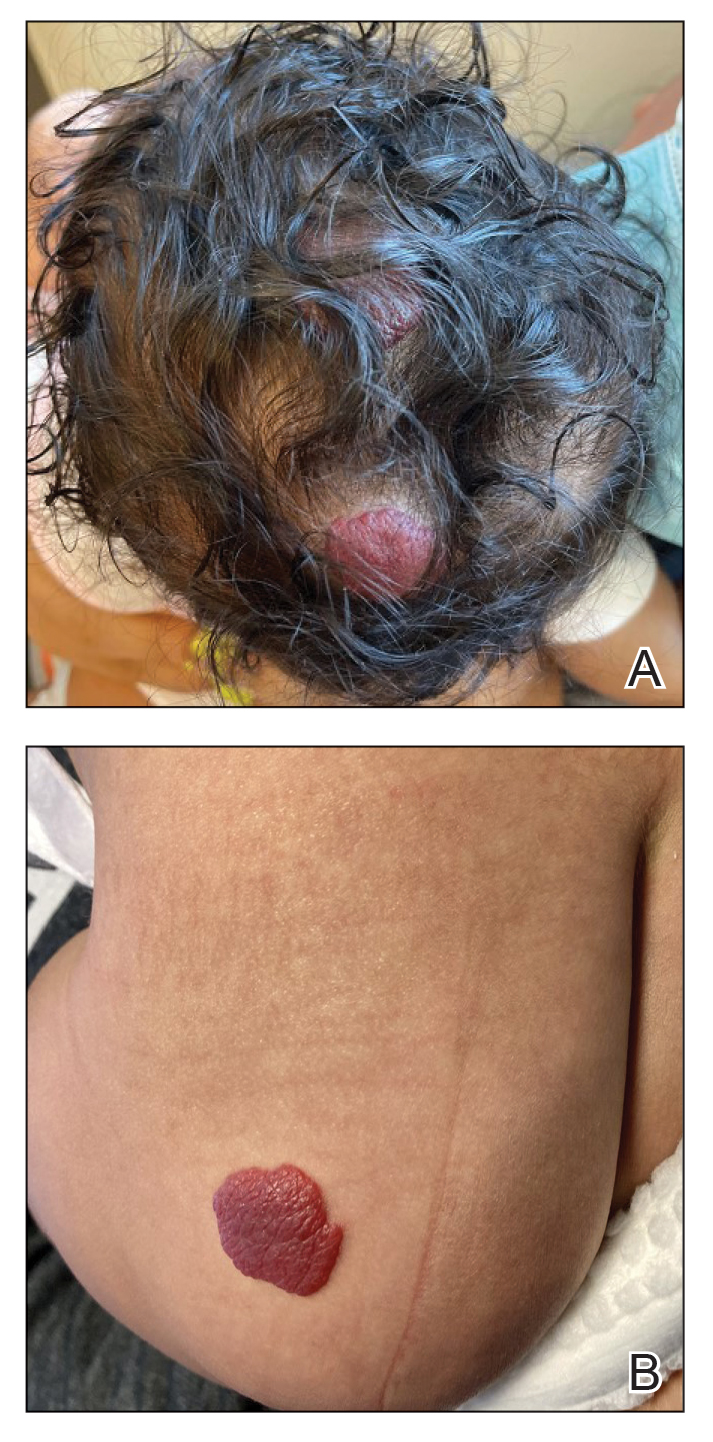

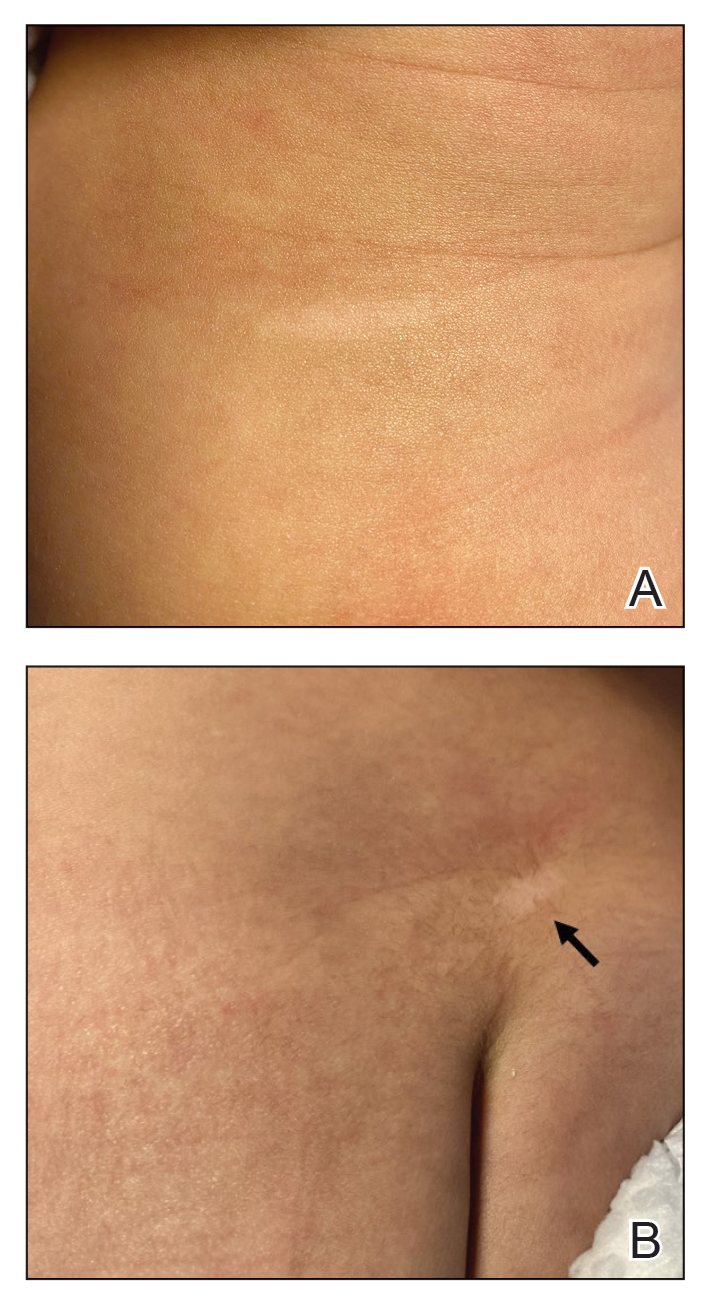

The median age of the children was 8.4 years. A total of 60% were men. The median disease duration at the time of entry was 1.2 months. Most had fever (95%) and rash (80%) with high levels of inflammatory markers at baseline. The mean number of painful joints was 3.1, and the mean number of systemic manifestations was 2.8. No patient was without any systemic involvement, but four of the patients did not have any painful joints.

At enrollment, patients were scheduled to receive three injections of canakinumab at monthly intervals during an active treatment phase, after which they entered an observation phase lasting 40 weeks. In the event of nonresponse or flares in either phase, they were transitioned to usual care.

Symptoms Resolve After Single Injection

After the first injection, active joint disease and all systemic manifestations resolved in 16 (80%) of the 20 patients. Joint activity and systemic manifestations also remained controlled after the second and third injections in 16 of the 20 patients.

One patient in this series achieved inactive disease after a single injection but developed what appeared to be a treatment-related allergic reaction. He received no further treatment and was excluded from the study, although he is being followed separately.

“According to sJADAS [systemic JIA Disease Activity Score] criteria at month 3, 14 had inactive disease, three had minimal disease activity, and one patient had moderate disease activity,” Dr. Horneff said.

At week 24, or 3 months after the last injection, there was still no joint activity in 16 patients. Systemic manifestations remained controlled in 13 patients, but 1 patient by this point had a flare. Another flare occurred after this point, and other patients have not yet completed the 52-week observation period.

“Of the 10 patients who remained in the study and have completed the 52-week observation period, eight have had a drug-free remission,” Dr. Horneff said.

MAS Event Observed in One Patient

In addition to the allergic skin reaction, which was considered probably related to the study drug, there were three flares, one of which was a macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) event. The MAS occurred 8 weeks after the last injection, but it was managed successfully.

Of 30 infections that developed during the observation period, 18 involved the upper airway. All were treated successfully. There were also two injection-site reactions and one case of cytopenia.

Among the studies planned for follow-up, investigators will examine genomic and gene activation in relation to disease activity and the effect of canakinumab.

Comoderator of the abstract session and chair of the EULAR 2024 Abstract Selection Committee, Christian Dejaco, MD, PhD, a consultant rheumatologist and associate professor at the Medical University of Graz in Graz, Austria, suggested that these are highly encouraging data for a disease that does not currently have any approved therapies. Clearly, larger studies with a longer follow-up period are needed, but he pointed out that phase 3 trials in a rare disease like sJIA are challenging.

Because of the limited number of cases, “it will be difficult to conduct a placebo-controlled trial,” he pointed out. However, he hopes this study will provide the basis for larger studies and sufficient data to lead to an indication for this therapy.

In the meantime, he also believes that these data are likely to support empirical use in a difficult disease, even in advance of formal regulatory approval.

“We heard that canakinumab is already being used off label in JIA, and these data might encourage more of that,” he said.

Dr. Horneff reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobe. Dr. Dejaco reported no potential conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA — The interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) canakinumab provided control of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) without the use of glucocorticoids for up to a year in most study participants after three monthly injections.

In this study of 20 patients with newly diagnosed sJIA treated off glucocorticoids, fever was controlled after a single injection in all patients, and 16 patients reached the primary outcome of remission after three injections, said Gerd Horneff, MD, PhD, Asklepios Children’s Hospital, Sankt Augustin, Germany.

Results of this open-label study, called CANAKINUMAB FIRST, were presented as late-breaking findings at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2024 Annual Meeting.

“Steroid-free, first-line treatment with canakinumab led to sustained responses in most patients, with a considerable number achieving remission,” said Dr. Horneff, adding that the observation in this group is ongoing.

Building on Earlier Data

The efficacy of canakinumab was previously reported in anecdotal experiences and one small patient series published 10 years ago. Dr. Horneff noted that he has offered this drug off label to patients with challenging cases.

The objective was to evaluate canakinumab as a first-line monotherapy administered in the absence of glucocorticoids. The study was open to children aged 2-18 years with active sJIA/juvenile Still disease confirmed with published criteria. All were naive to biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs as well as steroids.

The median age of the children was 8.4 years. A total of 60% were men. The median disease duration at the time of entry was 1.2 months. Most had fever (95%) and rash (80%) with high levels of inflammatory markers at baseline. The mean number of painful joints was 3.1, and the mean number of systemic manifestations was 2.8. No patient was without any systemic involvement, but four of the patients did not have any painful joints.

At enrollment, patients were scheduled to receive three injections of canakinumab at monthly intervals during an active treatment phase, after which they entered an observation phase lasting 40 weeks. In the event of nonresponse or flares in either phase, they were transitioned to usual care.

Symptoms Resolve After Single Injection

After the first injection, active joint disease and all systemic manifestations resolved in 16 (80%) of the 20 patients. Joint activity and systemic manifestations also remained controlled after the second and third injections in 16 of the 20 patients.

One patient in this series achieved inactive disease after a single injection but developed what appeared to be a treatment-related allergic reaction. He received no further treatment and was excluded from the study, although he is being followed separately.

“According to sJADAS [systemic JIA Disease Activity Score] criteria at month 3, 14 had inactive disease, three had minimal disease activity, and one patient had moderate disease activity,” Dr. Horneff said.

At week 24, or 3 months after the last injection, there was still no joint activity in 16 patients. Systemic manifestations remained controlled in 13 patients, but 1 patient by this point had a flare. Another flare occurred after this point, and other patients have not yet completed the 52-week observation period.

“Of the 10 patients who remained in the study and have completed the 52-week observation period, eight have had a drug-free remission,” Dr. Horneff said.

MAS Event Observed in One Patient

In addition to the allergic skin reaction, which was considered probably related to the study drug, there were three flares, one of which was a macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) event. The MAS occurred 8 weeks after the last injection, but it was managed successfully.

Of 30 infections that developed during the observation period, 18 involved the upper airway. All were treated successfully. There were also two injection-site reactions and one case of cytopenia.

Among the studies planned for follow-up, investigators will examine genomic and gene activation in relation to disease activity and the effect of canakinumab.

Comoderator of the abstract session and chair of the EULAR 2024 Abstract Selection Committee, Christian Dejaco, MD, PhD, a consultant rheumatologist and associate professor at the Medical University of Graz in Graz, Austria, suggested that these are highly encouraging data for a disease that does not currently have any approved therapies. Clearly, larger studies with a longer follow-up period are needed, but he pointed out that phase 3 trials in a rare disease like sJIA are challenging.

Because of the limited number of cases, “it will be difficult to conduct a placebo-controlled trial,” he pointed out. However, he hopes this study will provide the basis for larger studies and sufficient data to lead to an indication for this therapy.

In the meantime, he also believes that these data are likely to support empirical use in a difficult disease, even in advance of formal regulatory approval.

“We heard that canakinumab is already being used off label in JIA, and these data might encourage more of that,” he said.

Dr. Horneff reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobe. Dr. Dejaco reported no potential conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EULAR 2024

Oncology Mergers Are on the Rise. How Can Independent Practices Survive?

When he completed his fellowship at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Moshe Chasky, MD, joined a small five-person practice that rented space from the city’s Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. The arrangement seemed to work well for the hospital and the small practice, which remained independent.

Within 10 years, the hospital sought to buy the practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

But the oncologists at Alliance did not want to join Jefferson.

The hospital eventually entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient oncology/hematology services at three Jefferson Health–Northeast hospitals and stripped Dr. Chasky and his colleagues of their privileges at those facilities, Medscape Medical News reported last year.

said Jeff Patton, MD, CEO of OneOncology, a management services organization.

A 2020 report from the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), for instance, tracked mergers, acquisitions, and closures in the community oncology setting and found the number of practices acquired by hospitals, known as vertical integration, nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020.

“Some hospitals are pretty predatory in their approach,” Dr. Patton said. If hospitals have their own oncology program, “they’ll employ the referring doctors and then discourage them or prevent them from referring patients to our independent practices that are not owned by the hospital.”

Still, in the face of growing pressure to join hospitals, some community oncology practices are finding ways to survive and maintain their independence.

A Growing Trend

The latest data continue to show a clear trend: Consolidation in oncology is on the rise.

A 2024 study revealed that the pace of consolidation seems to be increasing.

The analysis found that, between 2015 and 2022, the number of medical oncologists increased by 14% and the number of medical oncologists per practice increased by 40%, while the number of practices decreased by 18%.

While about 44% of practices remain independent, the percentage of medical oncologists working in practices with more than 25 clinicians has increased from 34% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. By 2022, the largest 102 practices in the United States employed more than 40% of all medical oncologists.

“The rate of consolidation seems to be rapid,” study coauthor Parsa Erfani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained.

Consolidation appears to breed more consolidation. The researchers found, for instance, that markets with greater hospital consolidation and more hospital beds per capita were more likely to undergo consolidation in oncology.

Consolidation may be higher in these markets “because hospitals or health systems are buying up oncology practices or conversely because oncology practices are merging to compete more effectively with larger hospitals in the area,” Dr. Erfani told this news organization.

Mergers among independent practices, known as horizontal integration, have also been on the rise, according to the 2020 COA report. These mergers can help counter pressures from hospitals seeking to acquire community practices as well as prevent practices and their clinics from closing.

Although Dr. Erfani’s research wasn’t designed to determine the factors behind consolidation, he and his colleagues point to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program as potential drivers of this trend.

The ACA encouraged consolidation as a way to improve efficiency and created the need for ever-larger information systems to collect and report quality data. But these data collection and reporting requirements have become increasingly difficult for smaller practices to take on.

The 340B Program, however, may be a bigger contributing factor to consolidation. Created in 1992, the 340B Program allows qualifying hospitals and clinics that treat low-income and uninsured patients to buy outpatient prescription drugs at a 25%-50% discount.

Hospitals seeking to capitalize on the margins possible under the 340B Program will “buy all the referring physicians in a market so that the medical oncology group is left with little choice but to sell to the hospital,” said Dr. Patton.

“Those 340B dollars are worth a lot to hospitals,” said David A. Eagle, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with New York Cancer & Blood Specialists and past president of COA. The program “creates an appetite for nonprofit hospitals to want to grow their medical oncology programs,” he told this news organization.

Declining Medicare reimbursement has also hit independent practices hard.