User login

Skin Cancer Education in the Medical School Curriculum

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

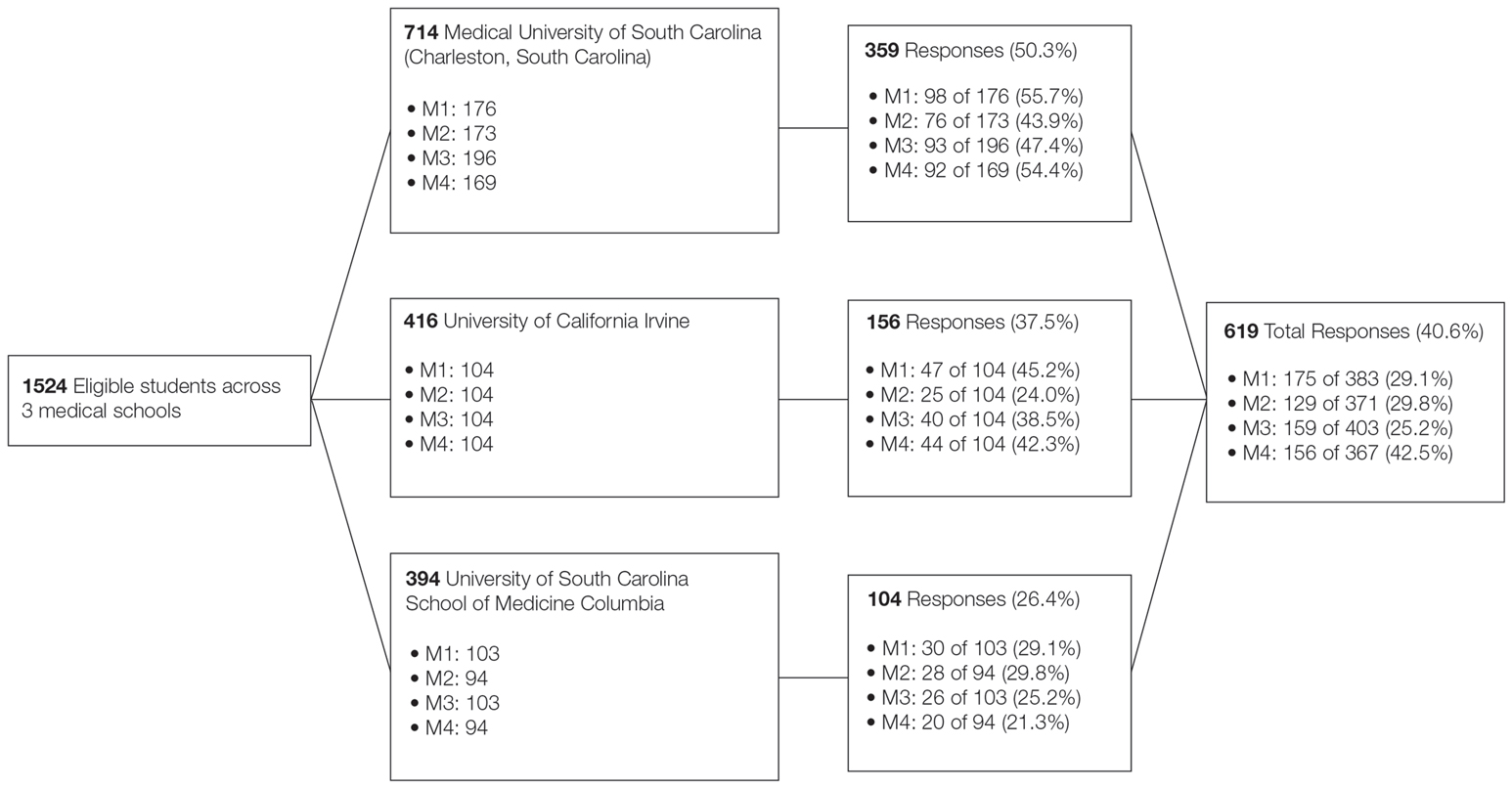

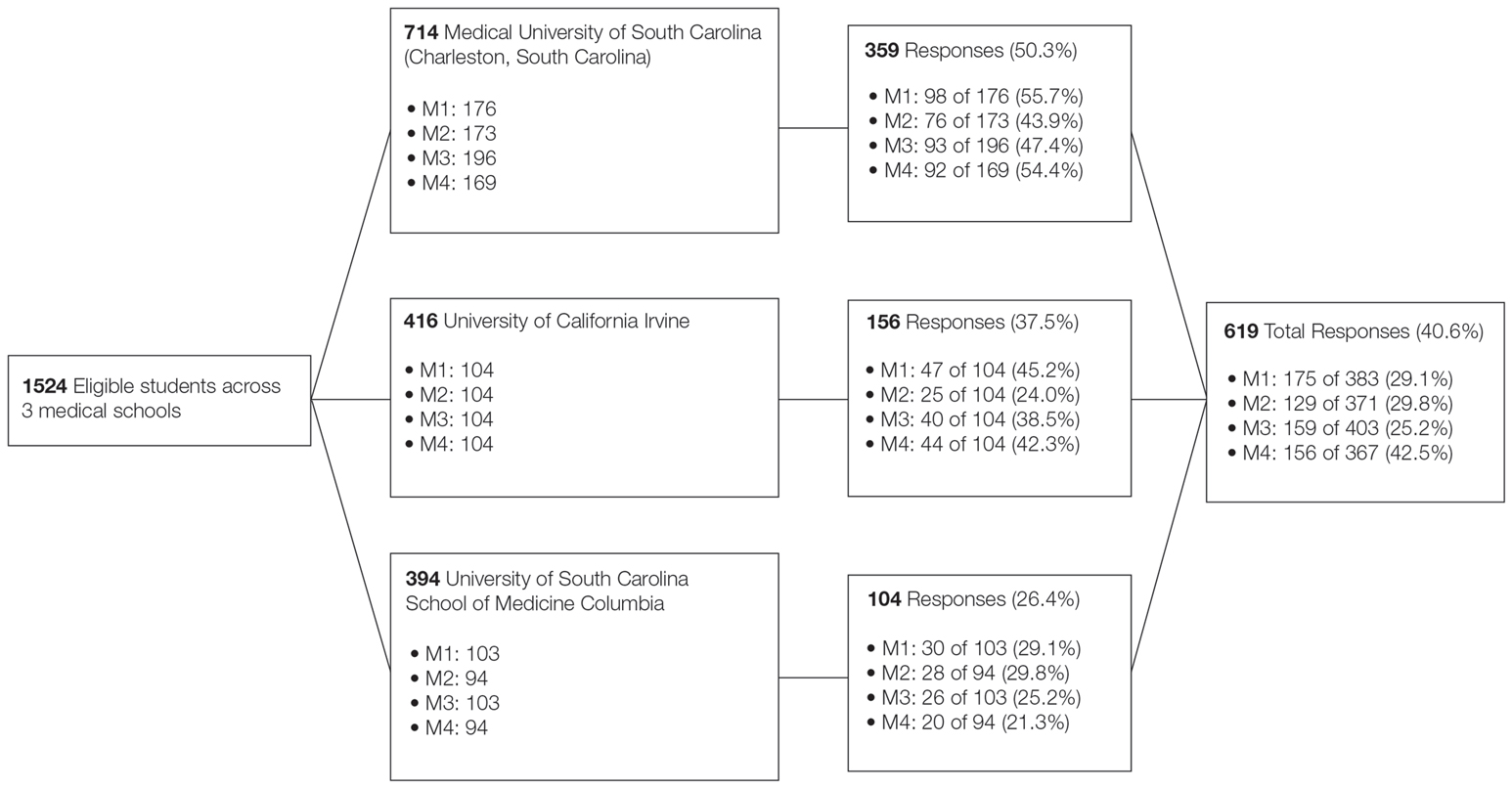

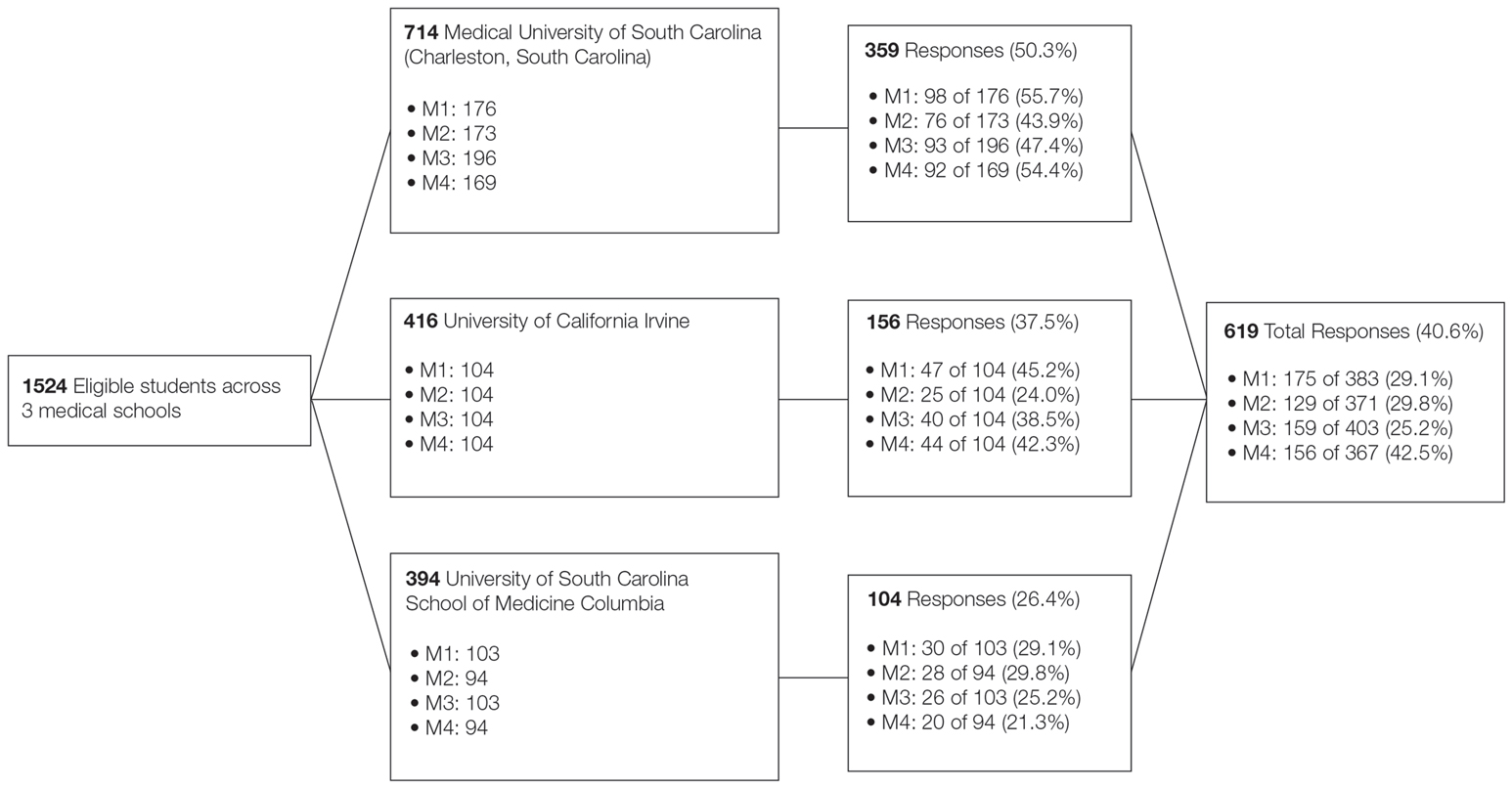

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

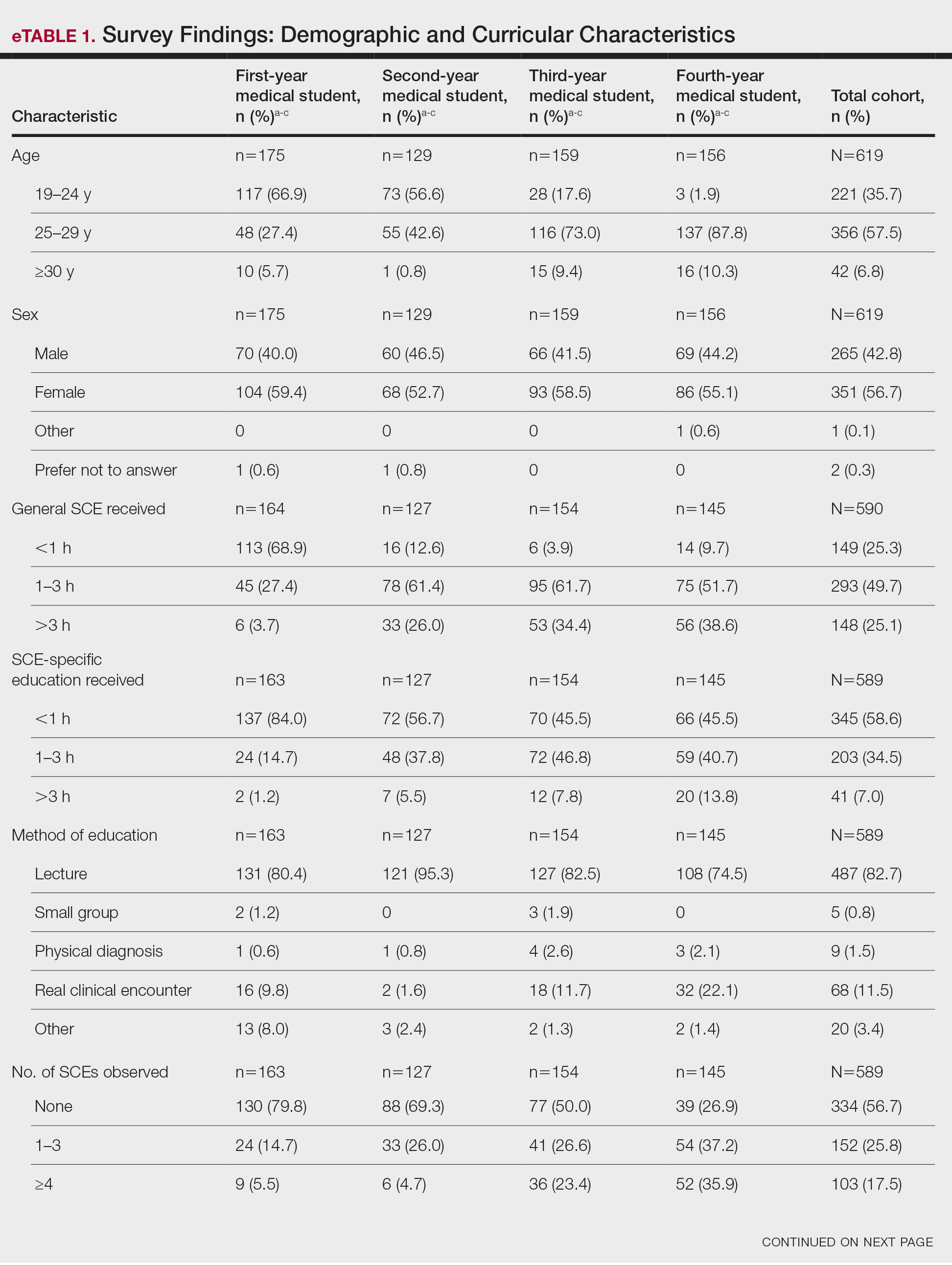

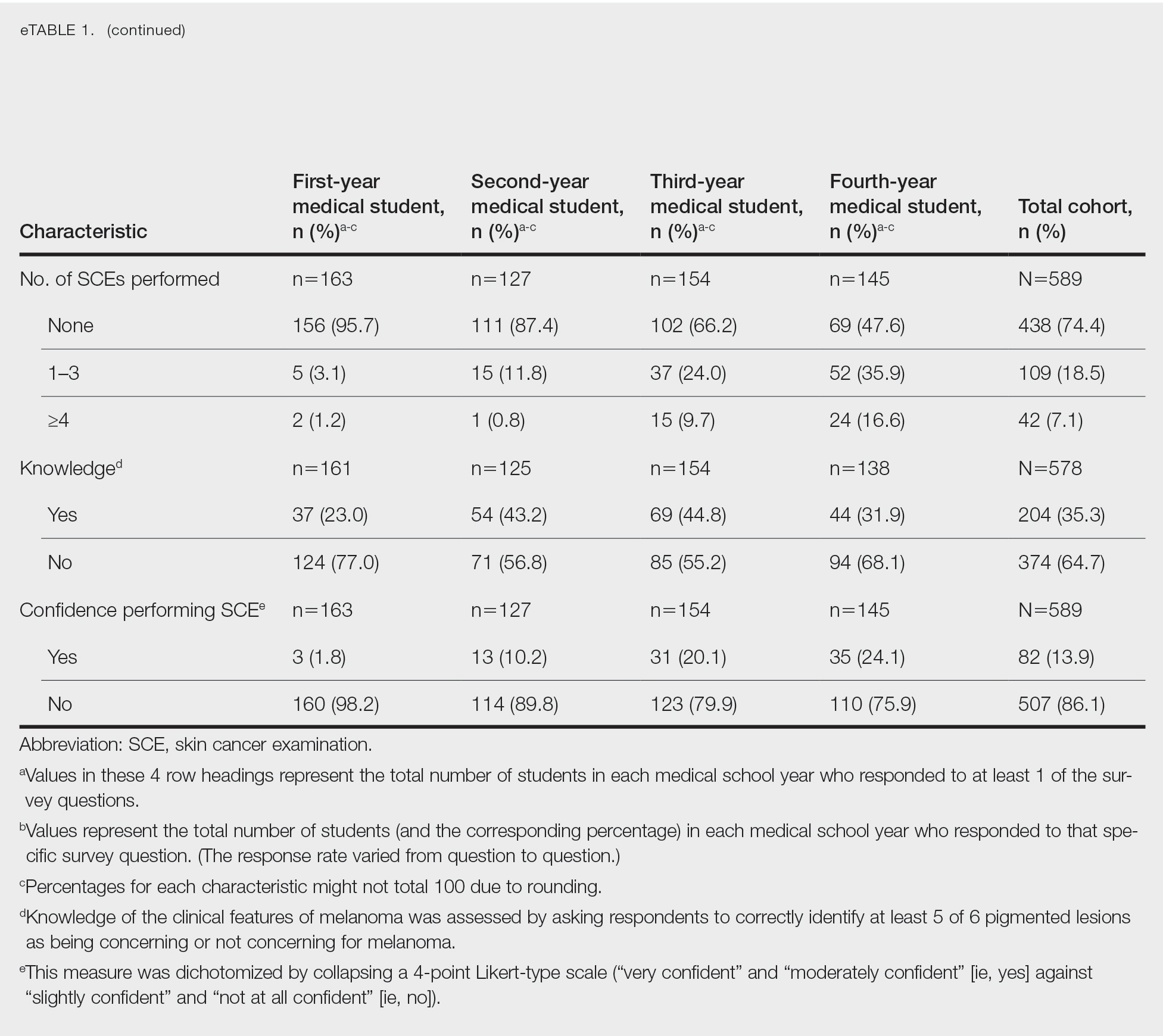

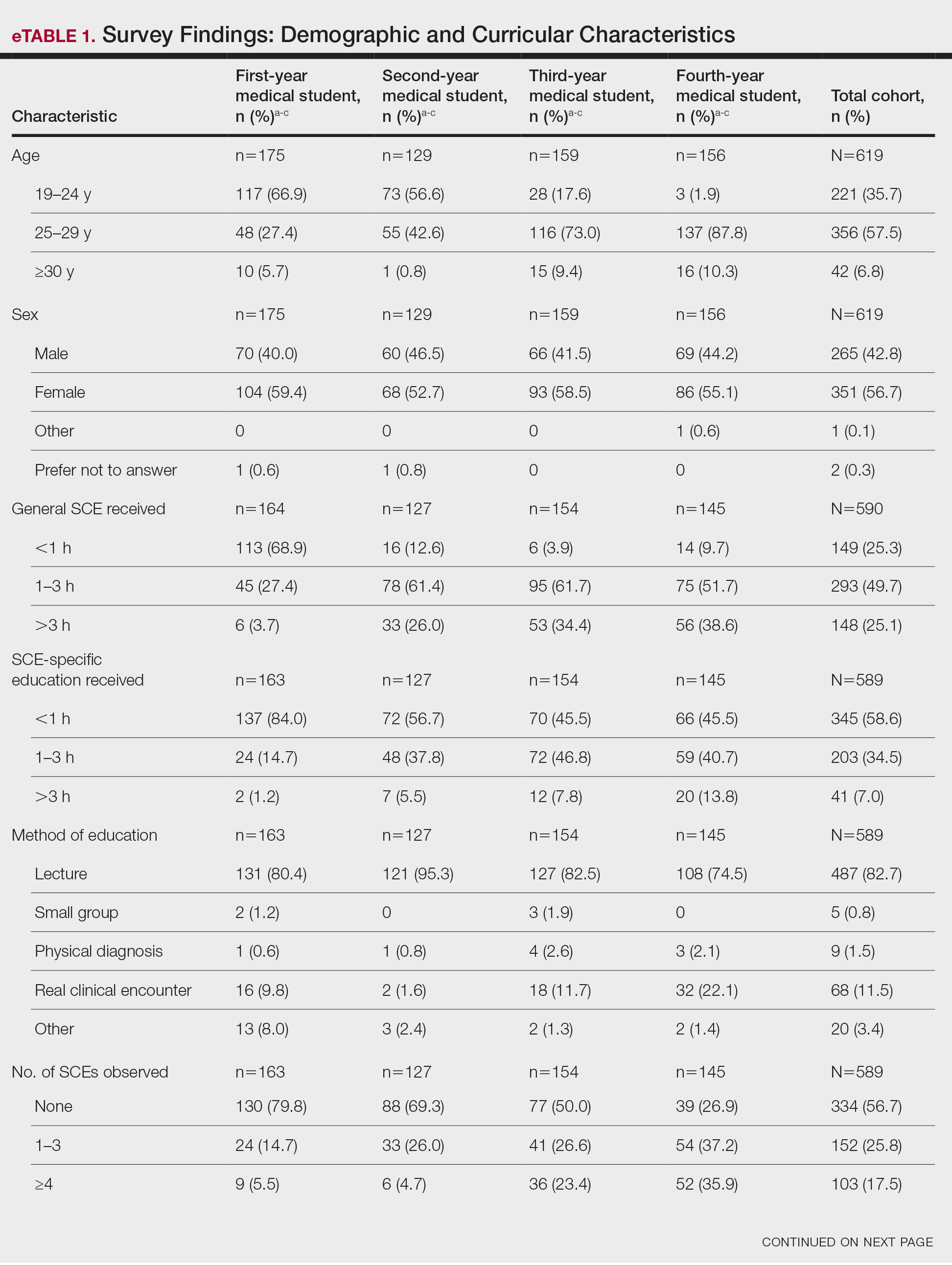

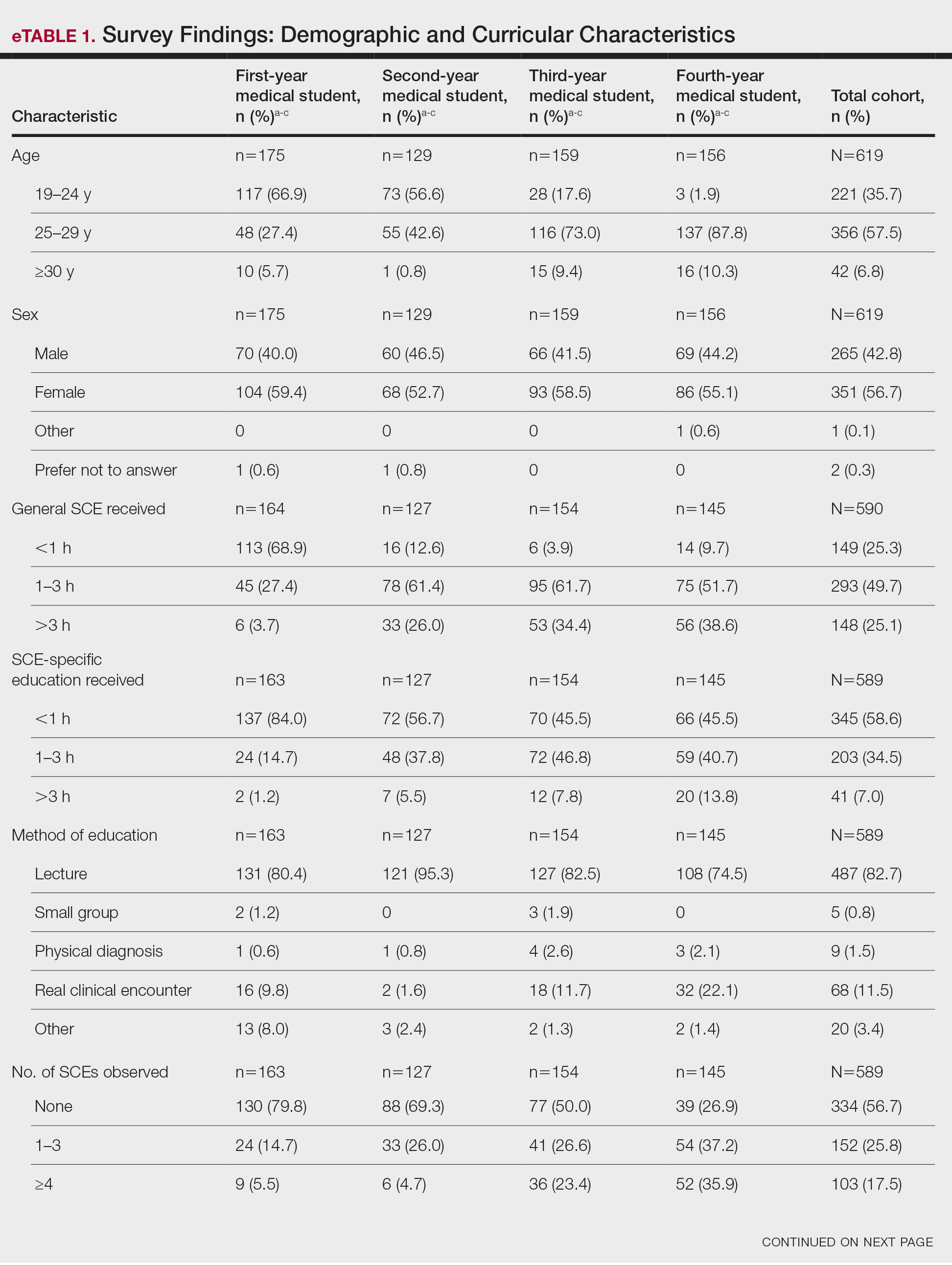

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

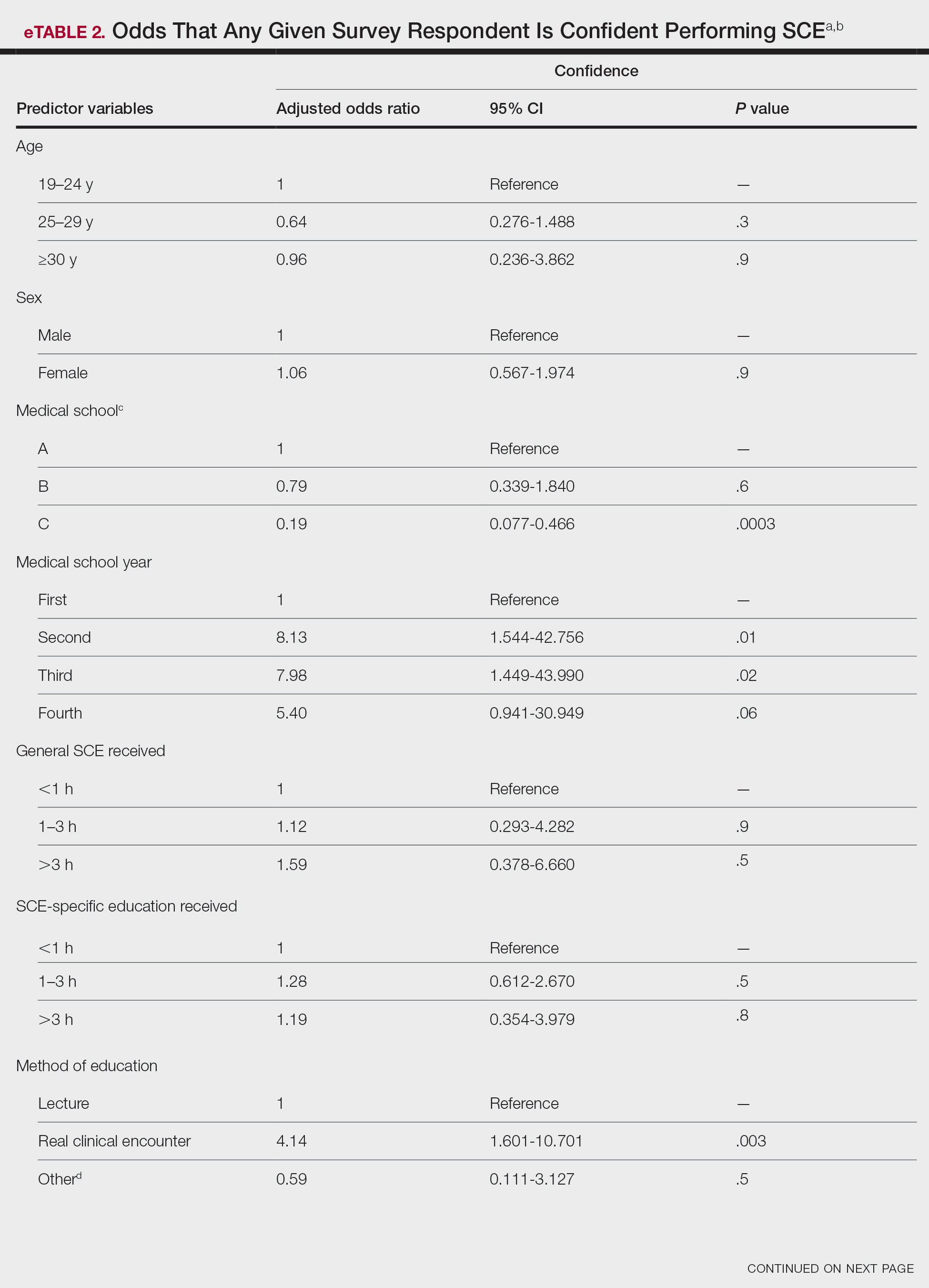

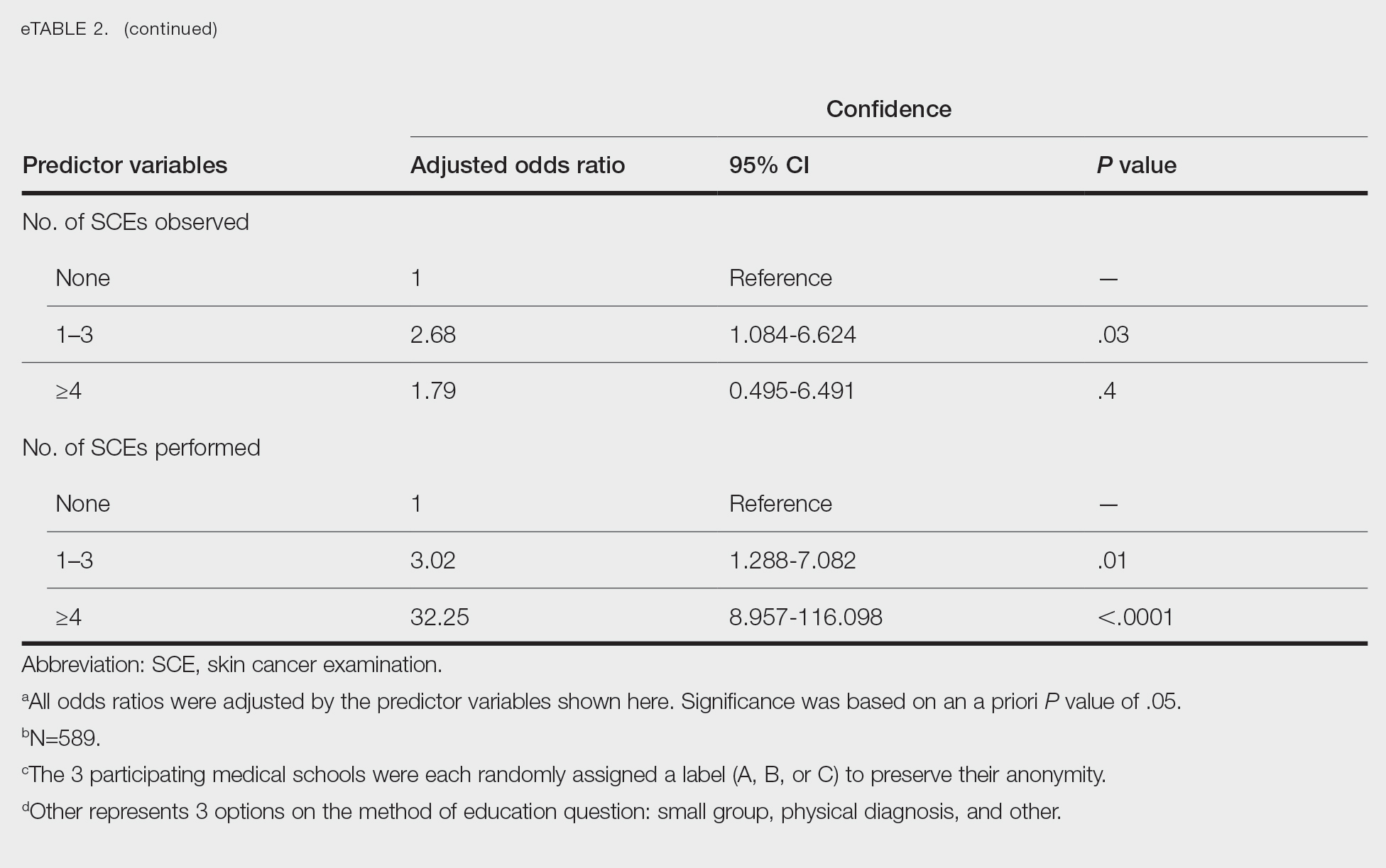

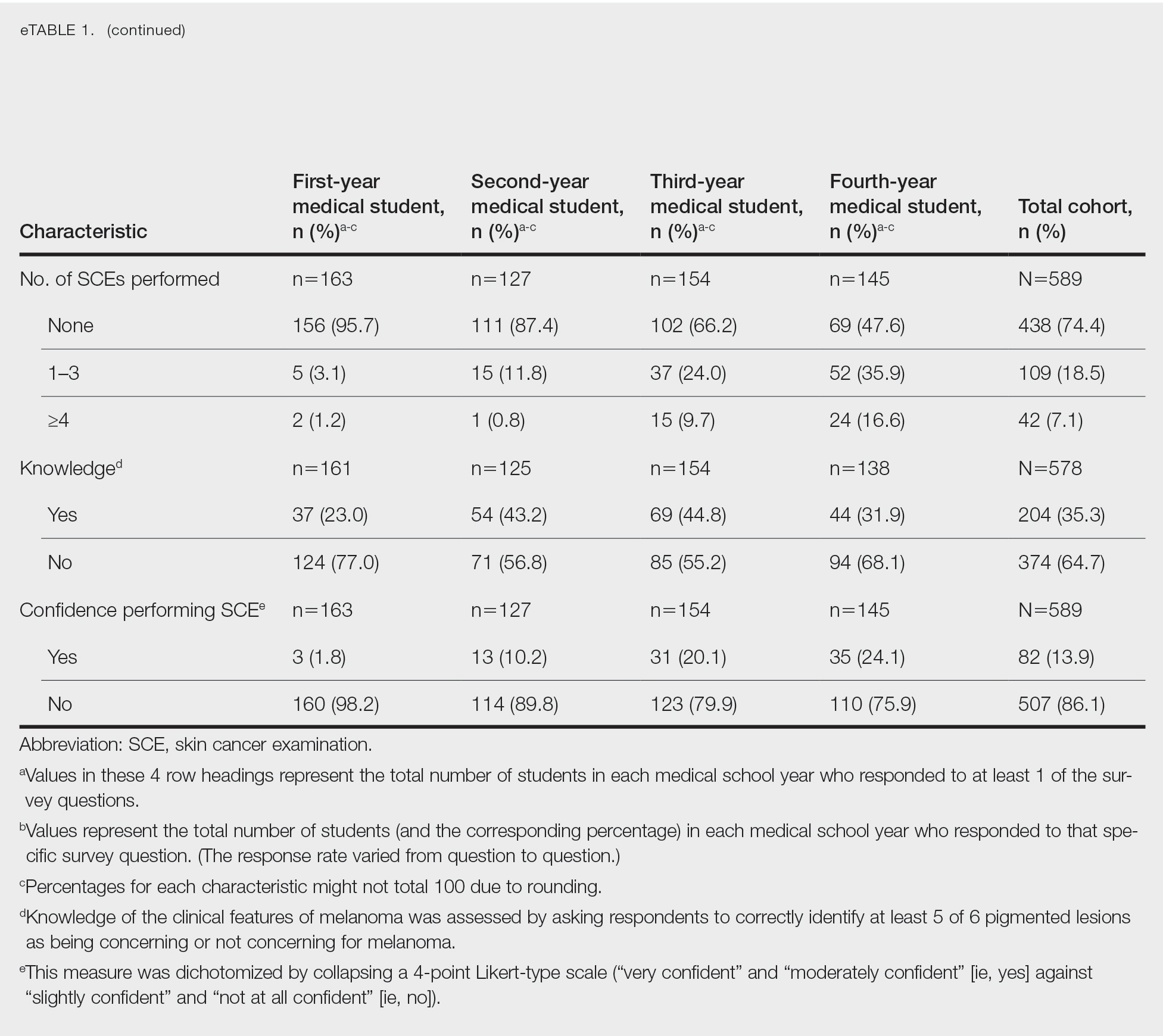

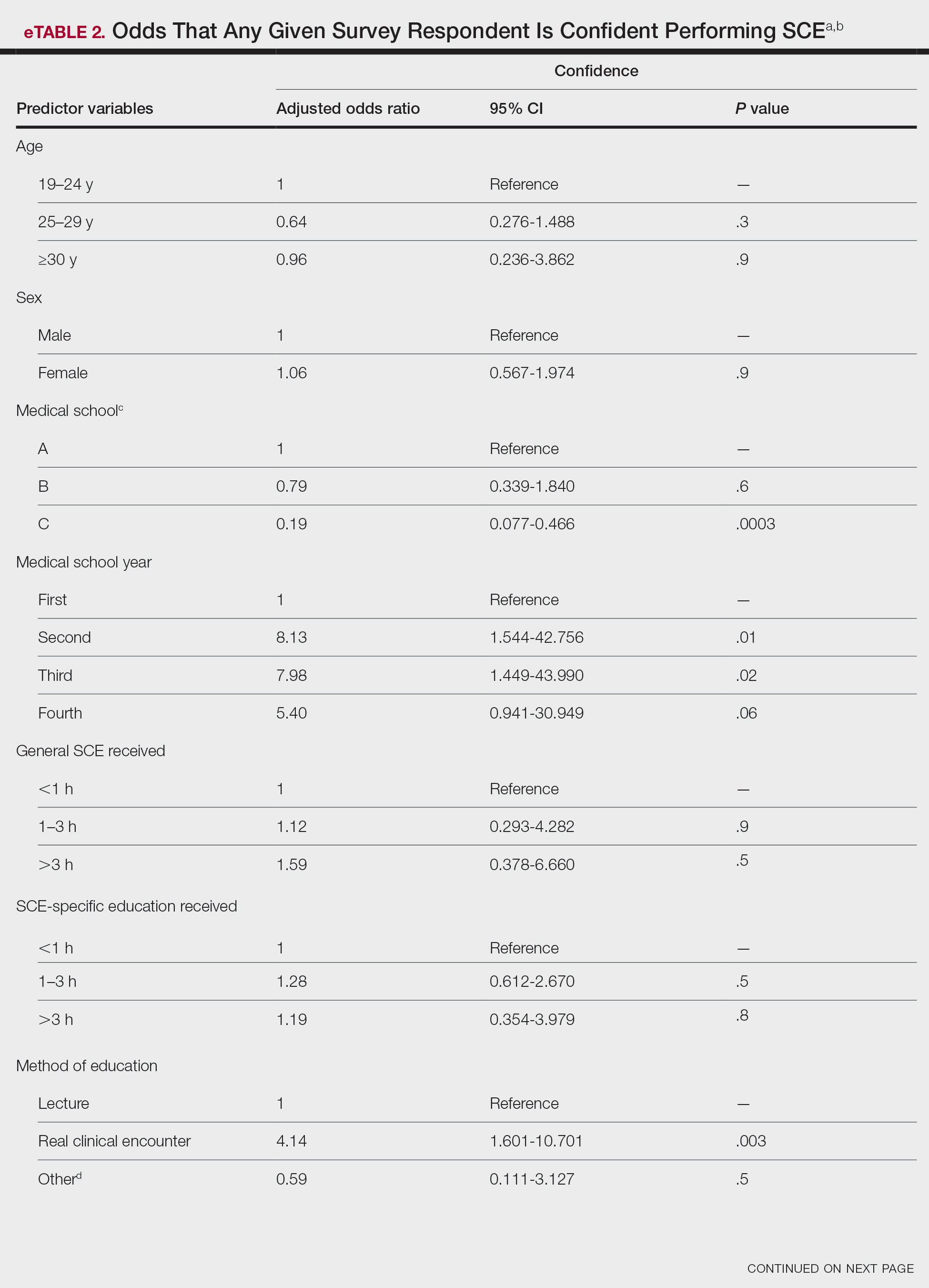

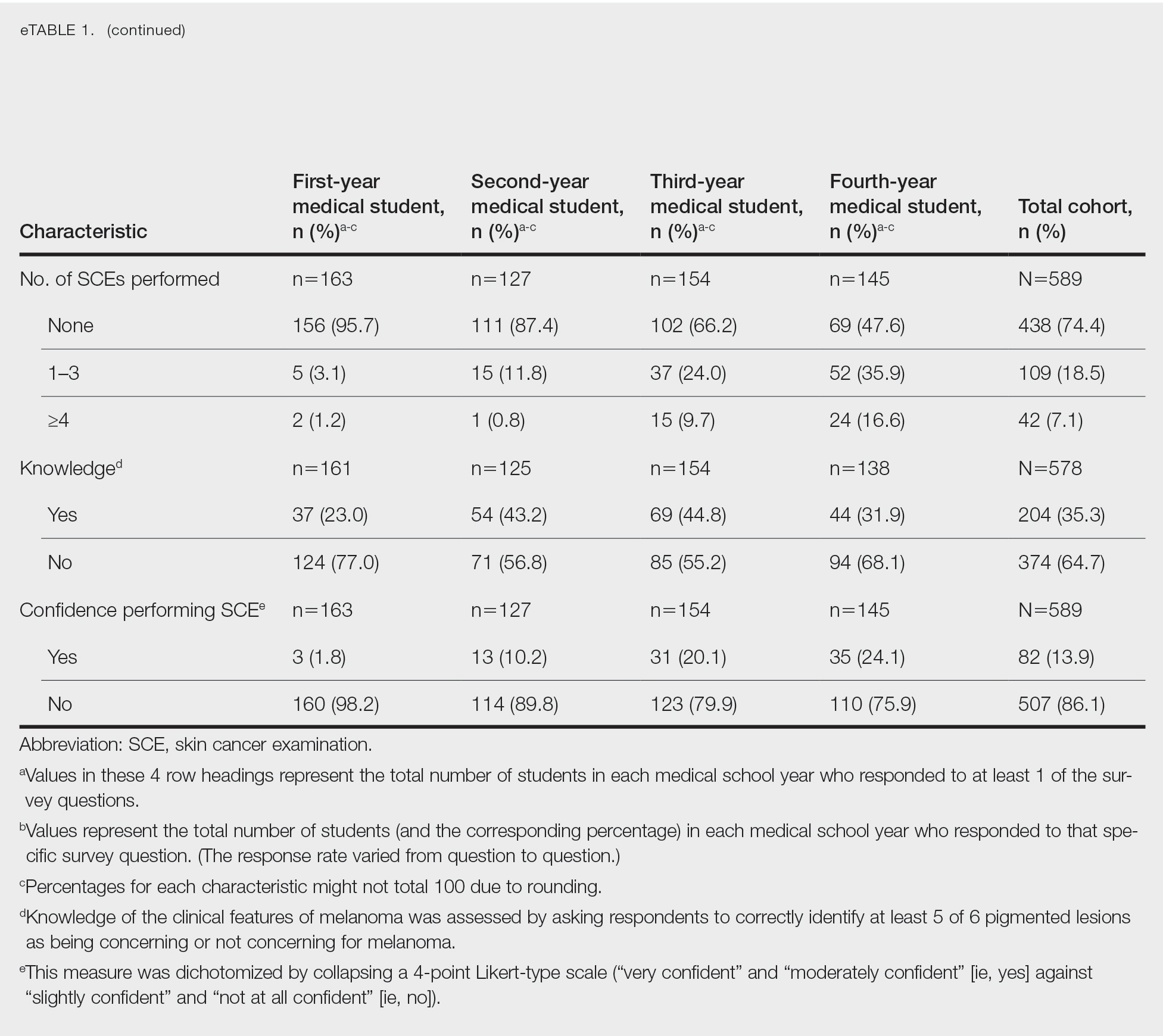

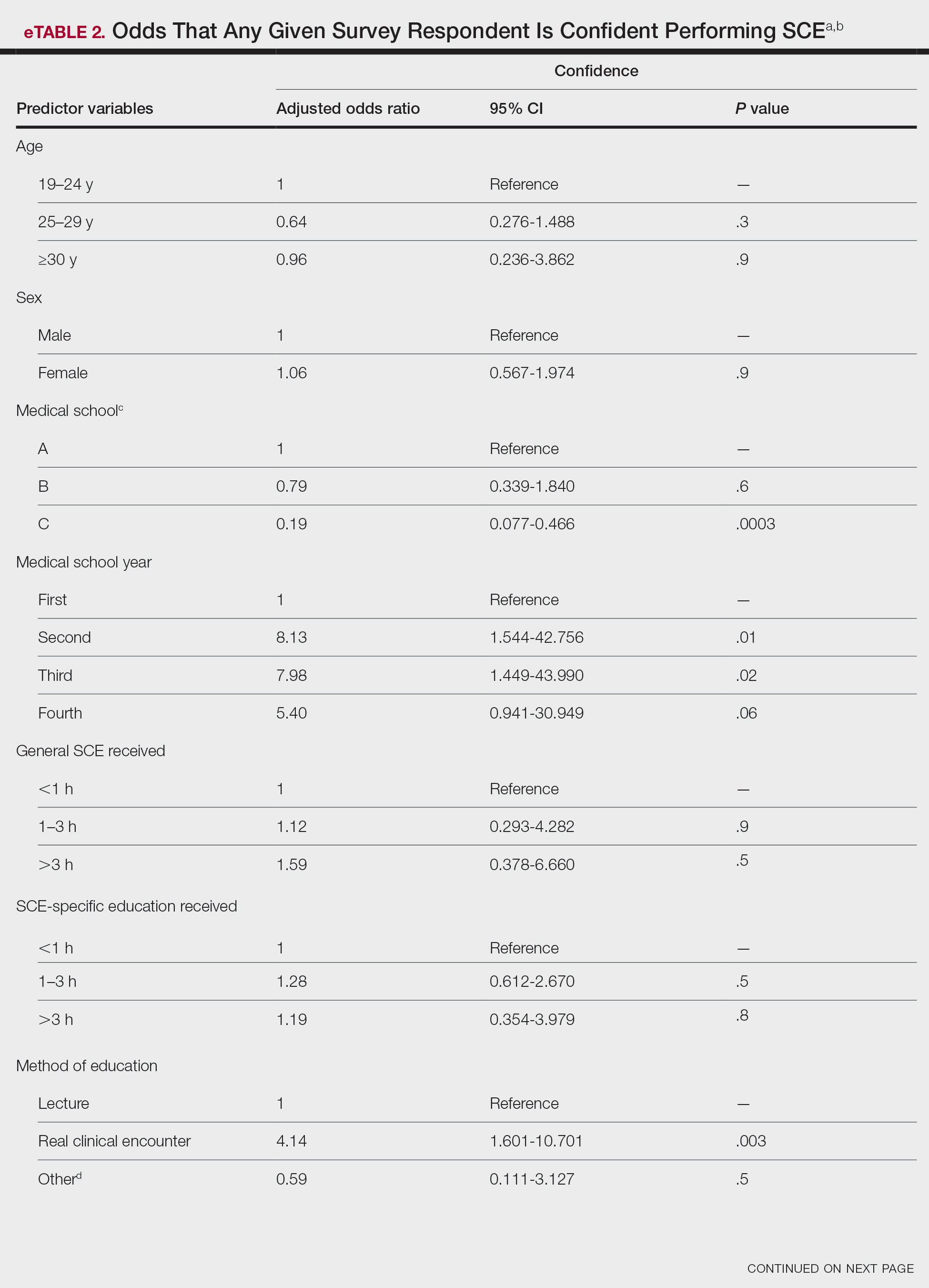

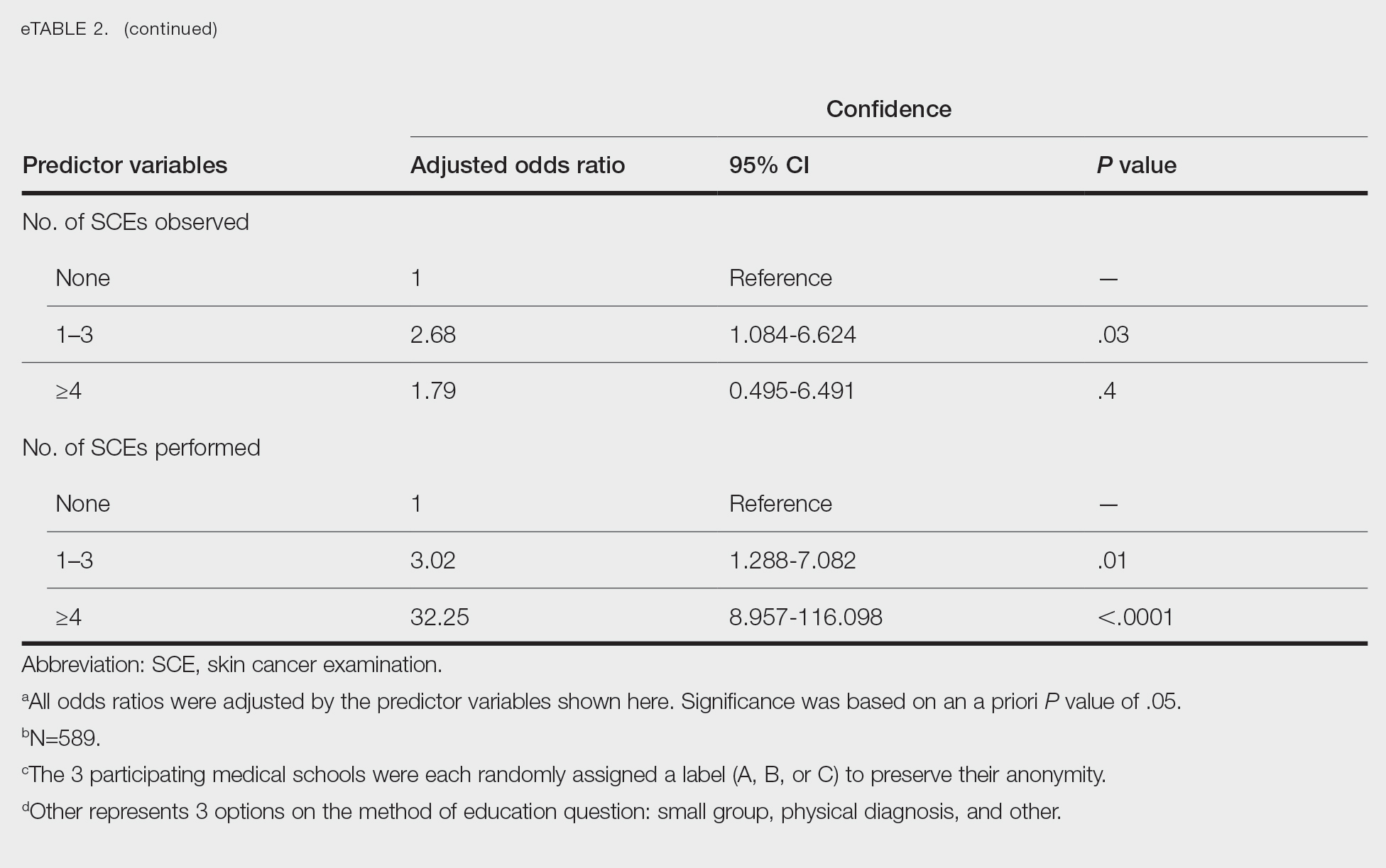

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

To the Editor:

Skin cancer represents a notable health care burden of rising incidence.1-3 Nondermatologist health care providers play a key role in skin cancer screening through the use of skin cancer examination (SCE)1,4; however, several factors including poor diagnostic accuracy, low confidence, and lack of training have contributed to limited use of the SCE by these providers.4,5 Therefore, it is important to identify and implement changes in the medical school curriculum that can facilitate improved use of SCE in clinical practice. We sought to examine factors in the medical school curriculum that influence skin cancer education.

A voluntary electronic survey was distributed through class email and social media to all medical student classes at 4 medical schools (Figure). Responses were collected between March 2 and April 20, 2020. Survey items assessed demographics and curricular factors that influence skin cancer education.

Knowledge of the clinical features of melanoma was assessed by asking participants to correctly identify at least 5 of 6 pigmented lesions as concerning or not concerning for melanoma. Confidence in performing the SCE—the primary outcome—was measured by dichotomizing a 4-point Likert-type scale (“very confident” and “moderately confident” against “slightly confident” and “not at all confident”).

Logistic regression was used to examine curricular factors associated with confidence; descriptive statistics were used for remaining analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Prior to analysis, responses from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville were excluded because the response rate was less than 20%.

The survey was distributed to 1524 students; 619 (40.6%) answered at least 1 question, with a variable response rate to each item (eTable 1). Most respondents were female (351 [56.7%]); 438 (70.8%) were White.

Most respondents said that they received 3 hours or less of general skin cancer (74.9%) or SCE-specific (93.0%) education by the end of their fourth year of medical training. Lecture was the most common method of instruction. Education was provided most often by dermatologists (48.6%), followed by general practice physicians (21.2%). Numerous (26.9%) fourth-year respondents reported that they had never observed SCE; even more (47.6%) had never performed SCE. Almost half of second- and third-year students (43.2% and 44.8%, respectively) considered themselves knowledgeable about the clinical features of melanoma, but only 31.9% of fourth-year students considered themselves knowledgeable.

Only 24.1% of fourth-year students reported confidence performing SCE (eTable 1). Students who received most of their instruction through real clinical encounters were 4.14 times more likely to be confident performing SCE than students who had been given lecture-based learning. Students who performed 1 to 3 SCE or 4 or more SCE were 3.02 and 32.25 times, respectively, more likely to be confident than students who had never performed SCE (eTable 2).

Consistent with a recent study,6 our results reflect the discrepancy between the burden and education of skin cancer. This is especially demonstrated by our cohort’s low confidence in performing SCE, a metric associated with both intention to perform and actual performance of SCE in practice.4,5 We also observed a downward trend in knowledge among students who were about to enter residency, potentially indicating the need for longitudinal training.

Given curricular time constraints, it is essential that medical schools implement changes in learning that will have the greatest impact. Although our results strongly support the efficacy of hands-on clinical training, exposure to dermatology in the second half of medical school training is limited nationwide.6 Concentrated efforts to increase clinical exposure might help prepare future physicians in all specialties to combat the burden of this disease.

Limitations of our study include the potential for selection and recall biases. Although our survey spanned multiple institutions in different regions of the United States, results might not be universally representative.

Acknowledgments—We thank Dirk Elston, MD, and Amy Wahlquist, MS (both from Charleston, South Carolina), who helped facilitate the survey on which our research is based. We also acknowledge the assistance of Philip Carmon, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Julie Flugel (Columbia, South Carolina); Algimantas Simpson, MD (Columbia, South Carolina); Nathan Jasperse, MD (Irvine, California); Jeremy Teruel, MD (Charleston, South Carolina); Alan Snyder, MD, MSCR (Charleston, South Carolina); John Bosland (Charleston, South Carolina); and Daniel Spangler (Greenville, South Carolina).

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036

- Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:57-64. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. Contribution of health care factors to the burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1151-1160.e21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.006

- Garg A, Wang J, Reddy SB, et al; Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. Curricular factors associated with medical students’ practice of the skin cancer examination: an educational enhancement initiative by the Integrated Skin Exam Consortium. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:850-855. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8723

- Oliveria SA, Heneghan MK, Cushman LF, et al. Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:39-44. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.414

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0006

Practice Points

- Nondermatologist practitioners play a notable role in mitigating the health care burden of skin cancer by screening with the skin cancer examination.

- Exposure to the skin cancer examination should occur during medical school prior to graduates’ entering diverse specialties.

- Most medical students received relatively few hours of skin cancer education, and many never performed or even observed a skin cancer examination prior to graduating medical school.

- Increasing hands-on training and clinical exposure during medical school is imperative to adequately prepare future physicians.

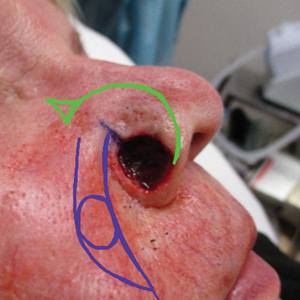

Field Cancerization in Dermatology: Updates on Treatment Considerations and Emerging Therapies

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

Pick your sunscreen carefully: 75% don’t pass muster

Just in time for Memorial Day outings, a new report on sunscreens is out.

The news isn’t all sunny. , a nonprofit research and advocacy group that just issued its 16th annual Guide to Sunscreens.

In response, dermatologists, including the president of the American Academy of Dermatology, say that although some concerns have been raised about the safety of some sunscreen ingredients, sunscreens themselves remain an important tool in the fight against skin cancer. According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, 1 in 5 Americans will get skin cancer by age 70. Melanoma, the most deadly, has a 5-year survival rate of 99% if caught early.

2022 report

Overall, the Environmental Working Group found that about 1 in 4 sunscreens, or about 500 products, met their standards for providing adequate sun protection and avoiding ingredients linked to known health harms. Products meant for babies and children did slightly better, with about 1 in 3 meeting the standards. The group evaluated mineral sunscreens, also called physical sunscreens, and non-mineral sunscreens, also called chemical sunscreens. Mineral sunscreens contain zinc oxide or titanium dioxide and sit on the skin to deflect the sun’s rays. Chemical sunscreens, with ingredients such as oxybenzone or avobenzone, are partially absorbed into the skin.

Among the group’s concerns:

- The use of oxybenzone in the non-mineral sunscreens. About 30% of the non-mineral sunscreens have it, says Carla Burns, senior director for cosmetic science for the Environmental Working Group. Oxybenzone is a potential hormone disrupter and a skin sensitizer that may harm children and adults, she says. Some progress has been made, as the group found oxybenzone in 66% of the non-mineral sunscreens it reviewed in 2019. (The FDA is seeking more information on oxybenzone and many other sunscreen ingredients.)

- Contamination of sunscreens with benzene, which has been linked to leukemia and other blood disorders, according to the National Cancer Institute. But industry experts stress that that chemical is found in trace amounts in personal care products and does not pose a safety concern. “Benzene is a chemical that is ubiquitous in the environment and not an intentionally added ingredient in personal care products. People worldwide are exposed daily to benzene from indoor and outdoor sources, including air, drinking water, and food and beverages,” the Personal Care Products Council, an industry group, said in a statement.

- Protection from ultraviolet A (UVA) rays is often inadequate, according to research published last year by the Environmental Working Group.

Products on the ‘best’ list

The Environmental Working Group found that 282 recreational sunscreens met its criteria. Among them:

- Coral Safe Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Neutrogena Sheer Zinc Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Mad Hippie Facial Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

The group chose 86 non-mineral sunscreens as better options, including:

- Alba Botanica Hawaiian Sunscreen Lotion, Aloe Vera, SPF 30

- Banana Boat Sport Ultra Sunscreen Stick, SPF 50+

- Black Girl Sunscreen Melanin Boosting Moisturizing Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

And 70 sunscreens made the kids’ best list, including:

- True Baby Everyday Play Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

- Sun Biologic Kids’ Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30+

- Kiss My Face Organic Kids’ Defense Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

Industry response, FDA actions

In a statement, Alexandra Kowcz, chief scientist at the Personal Care Products Council, pointed out that “as part of a daily safe-sun regimen, sunscreen products help prevent sunburn and reduce skin cancer risk. It is unfortunate that as Americans spend more time outdoors, the Environmental Working Group’s (EWG) 2022 Guide to Sunscreens resorts to fear-mongering with misleading information that could keep consumers from using sunscreens altogether.”

The FDA has asked for more information about certain ingredients to further evaluate products, she says, and industry is working with the agency. The FDA says it is attempting to improve the quality, safety and effectiveness of over-the-counter sunscreen products. In September, 2021, the FDA issued a proposal for regulating OTC sunscreen products, as required under the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act. The effective date for the final order can’t be earlier than September 2022, the CARES Act says.

Dermatologists weigh in

“Every time something like this gets published, my patients come in hysterical,” says Michele Green, MD, a New York City dermatologist who reviewed the report for WebMD. She acknowledges that more research is needed on some sunscreen ingredients. “We really do not know the long-term consequence of oxybenzone,” she says.

Her advice: If her patients have melasma (a skin condition with brown patches on the face), she advises them to use both a chemical and a mineral sunscreen. “I don’t tell my patients in general not to use the chemical [sunscreens].”

For children, she says, the mineral sunscreens may be preferred. On her own children, who are teens, she uses the mineral sunscreens, due to possible concern about hormone disruption.

In a statement, Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the American Academy of Dermatology, says that “sunscreen is an important part of a comprehensive sun protection strategy.”

Besides a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher for exposed skin, the academy recommends seeking shade and wearing sun-protective clothing to reduce skin cancer risk.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Just in time for Memorial Day outings, a new report on sunscreens is out.

The news isn’t all sunny. , a nonprofit research and advocacy group that just issued its 16th annual Guide to Sunscreens.

In response, dermatologists, including the president of the American Academy of Dermatology, say that although some concerns have been raised about the safety of some sunscreen ingredients, sunscreens themselves remain an important tool in the fight against skin cancer. According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, 1 in 5 Americans will get skin cancer by age 70. Melanoma, the most deadly, has a 5-year survival rate of 99% if caught early.

2022 report

Overall, the Environmental Working Group found that about 1 in 4 sunscreens, or about 500 products, met their standards for providing adequate sun protection and avoiding ingredients linked to known health harms. Products meant for babies and children did slightly better, with about 1 in 3 meeting the standards. The group evaluated mineral sunscreens, also called physical sunscreens, and non-mineral sunscreens, also called chemical sunscreens. Mineral sunscreens contain zinc oxide or titanium dioxide and sit on the skin to deflect the sun’s rays. Chemical sunscreens, with ingredients such as oxybenzone or avobenzone, are partially absorbed into the skin.

Among the group’s concerns:

- The use of oxybenzone in the non-mineral sunscreens. About 30% of the non-mineral sunscreens have it, says Carla Burns, senior director for cosmetic science for the Environmental Working Group. Oxybenzone is a potential hormone disrupter and a skin sensitizer that may harm children and adults, she says. Some progress has been made, as the group found oxybenzone in 66% of the non-mineral sunscreens it reviewed in 2019. (The FDA is seeking more information on oxybenzone and many other sunscreen ingredients.)

- Contamination of sunscreens with benzene, which has been linked to leukemia and other blood disorders, according to the National Cancer Institute. But industry experts stress that that chemical is found in trace amounts in personal care products and does not pose a safety concern. “Benzene is a chemical that is ubiquitous in the environment and not an intentionally added ingredient in personal care products. People worldwide are exposed daily to benzene from indoor and outdoor sources, including air, drinking water, and food and beverages,” the Personal Care Products Council, an industry group, said in a statement.

- Protection from ultraviolet A (UVA) rays is often inadequate, according to research published last year by the Environmental Working Group.

Products on the ‘best’ list

The Environmental Working Group found that 282 recreational sunscreens met its criteria. Among them:

- Coral Safe Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Neutrogena Sheer Zinc Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Mad Hippie Facial Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

The group chose 86 non-mineral sunscreens as better options, including:

- Alba Botanica Hawaiian Sunscreen Lotion, Aloe Vera, SPF 30

- Banana Boat Sport Ultra Sunscreen Stick, SPF 50+

- Black Girl Sunscreen Melanin Boosting Moisturizing Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

And 70 sunscreens made the kids’ best list, including:

- True Baby Everyday Play Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

- Sun Biologic Kids’ Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30+

- Kiss My Face Organic Kids’ Defense Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

Industry response, FDA actions

In a statement, Alexandra Kowcz, chief scientist at the Personal Care Products Council, pointed out that “as part of a daily safe-sun regimen, sunscreen products help prevent sunburn and reduce skin cancer risk. It is unfortunate that as Americans spend more time outdoors, the Environmental Working Group’s (EWG) 2022 Guide to Sunscreens resorts to fear-mongering with misleading information that could keep consumers from using sunscreens altogether.”

The FDA has asked for more information about certain ingredients to further evaluate products, she says, and industry is working with the agency. The FDA says it is attempting to improve the quality, safety and effectiveness of over-the-counter sunscreen products. In September, 2021, the FDA issued a proposal for regulating OTC sunscreen products, as required under the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act. The effective date for the final order can’t be earlier than September 2022, the CARES Act says.

Dermatologists weigh in

“Every time something like this gets published, my patients come in hysterical,” says Michele Green, MD, a New York City dermatologist who reviewed the report for WebMD. She acknowledges that more research is needed on some sunscreen ingredients. “We really do not know the long-term consequence of oxybenzone,” she says.

Her advice: If her patients have melasma (a skin condition with brown patches on the face), she advises them to use both a chemical and a mineral sunscreen. “I don’t tell my patients in general not to use the chemical [sunscreens].”

For children, she says, the mineral sunscreens may be preferred. On her own children, who are teens, she uses the mineral sunscreens, due to possible concern about hormone disruption.

In a statement, Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the American Academy of Dermatology, says that “sunscreen is an important part of a comprehensive sun protection strategy.”

Besides a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of 30 or higher for exposed skin, the academy recommends seeking shade and wearing sun-protective clothing to reduce skin cancer risk.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Just in time for Memorial Day outings, a new report on sunscreens is out.

The news isn’t all sunny. , a nonprofit research and advocacy group that just issued its 16th annual Guide to Sunscreens.

In response, dermatologists, including the president of the American Academy of Dermatology, say that although some concerns have been raised about the safety of some sunscreen ingredients, sunscreens themselves remain an important tool in the fight against skin cancer. According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, 1 in 5 Americans will get skin cancer by age 70. Melanoma, the most deadly, has a 5-year survival rate of 99% if caught early.

2022 report

Overall, the Environmental Working Group found that about 1 in 4 sunscreens, or about 500 products, met their standards for providing adequate sun protection and avoiding ingredients linked to known health harms. Products meant for babies and children did slightly better, with about 1 in 3 meeting the standards. The group evaluated mineral sunscreens, also called physical sunscreens, and non-mineral sunscreens, also called chemical sunscreens. Mineral sunscreens contain zinc oxide or titanium dioxide and sit on the skin to deflect the sun’s rays. Chemical sunscreens, with ingredients such as oxybenzone or avobenzone, are partially absorbed into the skin.

Among the group’s concerns:

- The use of oxybenzone in the non-mineral sunscreens. About 30% of the non-mineral sunscreens have it, says Carla Burns, senior director for cosmetic science for the Environmental Working Group. Oxybenzone is a potential hormone disrupter and a skin sensitizer that may harm children and adults, she says. Some progress has been made, as the group found oxybenzone in 66% of the non-mineral sunscreens it reviewed in 2019. (The FDA is seeking more information on oxybenzone and many other sunscreen ingredients.)

- Contamination of sunscreens with benzene, which has been linked to leukemia and other blood disorders, according to the National Cancer Institute. But industry experts stress that that chemical is found in trace amounts in personal care products and does not pose a safety concern. “Benzene is a chemical that is ubiquitous in the environment and not an intentionally added ingredient in personal care products. People worldwide are exposed daily to benzene from indoor and outdoor sources, including air, drinking water, and food and beverages,” the Personal Care Products Council, an industry group, said in a statement.

- Protection from ultraviolet A (UVA) rays is often inadequate, according to research published last year by the Environmental Working Group.

Products on the ‘best’ list

The Environmental Working Group found that 282 recreational sunscreens met its criteria. Among them:

- Coral Safe Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Neutrogena Sheer Zinc Mineral Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

- Mad Hippie Facial Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

The group chose 86 non-mineral sunscreens as better options, including:

- Alba Botanica Hawaiian Sunscreen Lotion, Aloe Vera, SPF 30

- Banana Boat Sport Ultra Sunscreen Stick, SPF 50+

- Black Girl Sunscreen Melanin Boosting Moisturizing Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

And 70 sunscreens made the kids’ best list, including:

- True Baby Everyday Play Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30+

- Sun Biologic Kids’ Sunscreen Stick, SPF 30+

- Kiss My Face Organic Kids’ Defense Sunscreen Lotion, SPF 30

Industry response, FDA actions

In a statement, Alexandra Kowcz, chief scientist at the Personal Care Products Council, pointed out that “as part of a daily safe-sun regimen, sunscreen products help prevent sunburn and reduce skin cancer risk. It is unfortunate that as Americans spend more time outdoors, the Environmental Working Group’s (EWG) 2022 Guide to Sunscreens resorts to fear-mongering with misleading information that could keep consumers from using sunscreens altogether.”

The FDA has asked for more information about certain ingredients to further evaluate products, she says, and industry is working with the agency. The FDA says it is attempting to improve the quality, safety and effectiveness of over-the-counter sunscreen products. In September, 2021, the FDA issued a proposal for regulating OTC sunscreen products, as required under the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act. The effective date for the final order can’t be earlier than September 2022, the CARES Act says.

Dermatologists weigh in

“Every time something like this gets published, my patients come in hysterical,” says Michele Green, MD, a New York City dermatologist who reviewed the report for WebMD. She acknowledges that more research is needed on some sunscreen ingredients. “We really do not know the long-term consequence of oxybenzone,” she says.