User login

For MD-IQ use only

COVID-19 pandemic dictates reconsideration of pemphigus therapy

The Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Together with physicians from the Mayo Clinic, Alexandria (Egypt) University, and Tehran (Iran) University, she recently published updated expert guidance for treatment of this severe, potentially fatal mucocutaneous autoimmune blistering disease, in a letter to the editor in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. She presented some of the key recommendations at AAD 2020.

First off, rituximab (Rituxan), the only Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris and a biologic considered first-line therapy prepandemic, is ill-advised during the COVID-19 era. Its mechanism of benefit is through B-cell depletion. This is an irreversible effect, and reconstitution of B-cell immunity takes 6-12 months. The absence of this immunologic protection for such a long time poses potentially serious problems for pemphigus patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Also, the opportunity to administer intravenous infusions of the biologic becomes unpredictable during pandemic surges, when limitations on nonemergent medical care may be necessary, noted Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, both in Sydney.

“We have taken the approach of postponing rituximab infusions temporarily, with the aim of delaying peak patient immunosuppression during peak COVID-19 incidence to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes,” Dr. Murrell and coauthors wrote in the letter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jun;82[6]:e235-6).

The other traditional go-to therapy for pemphigus is corticosteroids. They’re effective, fast acting, and relatively inexpensive. But their nonselective immunosuppressive action boosts infection risk in general, and more specifically it increases the risk of developing severe forms of COVID-19 should a patient become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“A basic therapeutic principle with particular importance during the pandemic is that glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, should be tapered to the lowest effective dose. In active COVID-19 infection, immunosuppressive steroid-sparing medications should be discontinued when possible, although glucocorticoid cessation often cannot be considered due to risk for adrenal insufficiency,” the authors continued.

“Effective as adjuvant treatment in both pemphigus and COVID-19,intravenous immunoglobulin supports immunity and therefore may be useful in this setting,” they wrote. It’s not immunosuppressive, and, they noted, there’s good-quality evidence from a Japanese randomized, double-blind, controlled trial that a 5-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin is effective therapy for pemphigus (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Apr;60[4]:595-603).

Moreover, intravenous immunoglobulin is also reportedly effective in severe COVID-19 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102.).

Another option is to consider enrolling a patient with moderate or severe pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in the ongoing pivotal phase 3, international, double-blind, placebo-controlled PEGASUS trial of rilzabrutinib, a promising oral reversible Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The medication has a short half-life and a self-limited immunomodulatory effect. Moreover, the trial is set up for remote patient visits on an outpatient basis via teledermatology, so the 65-week study can continue despite the pandemic. Both newly diagnosed and relapsing patients are eligible for the trial, headed by Dr. Murrell. At AAD 2020 she reported encouraging results from a phase 2b trial of rilzabrutinib.

She is a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the PEGASUS trial, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

The Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Together with physicians from the Mayo Clinic, Alexandria (Egypt) University, and Tehran (Iran) University, she recently published updated expert guidance for treatment of this severe, potentially fatal mucocutaneous autoimmune blistering disease, in a letter to the editor in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. She presented some of the key recommendations at AAD 2020.

First off, rituximab (Rituxan), the only Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris and a biologic considered first-line therapy prepandemic, is ill-advised during the COVID-19 era. Its mechanism of benefit is through B-cell depletion. This is an irreversible effect, and reconstitution of B-cell immunity takes 6-12 months. The absence of this immunologic protection for such a long time poses potentially serious problems for pemphigus patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Also, the opportunity to administer intravenous infusions of the biologic becomes unpredictable during pandemic surges, when limitations on nonemergent medical care may be necessary, noted Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, both in Sydney.

“We have taken the approach of postponing rituximab infusions temporarily, with the aim of delaying peak patient immunosuppression during peak COVID-19 incidence to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes,” Dr. Murrell and coauthors wrote in the letter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jun;82[6]:e235-6).

The other traditional go-to therapy for pemphigus is corticosteroids. They’re effective, fast acting, and relatively inexpensive. But their nonselective immunosuppressive action boosts infection risk in general, and more specifically it increases the risk of developing severe forms of COVID-19 should a patient become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“A basic therapeutic principle with particular importance during the pandemic is that glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, should be tapered to the lowest effective dose. In active COVID-19 infection, immunosuppressive steroid-sparing medications should be discontinued when possible, although glucocorticoid cessation often cannot be considered due to risk for adrenal insufficiency,” the authors continued.

“Effective as adjuvant treatment in both pemphigus and COVID-19,intravenous immunoglobulin supports immunity and therefore may be useful in this setting,” they wrote. It’s not immunosuppressive, and, they noted, there’s good-quality evidence from a Japanese randomized, double-blind, controlled trial that a 5-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin is effective therapy for pemphigus (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Apr;60[4]:595-603).

Moreover, intravenous immunoglobulin is also reportedly effective in severe COVID-19 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102.).

Another option is to consider enrolling a patient with moderate or severe pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in the ongoing pivotal phase 3, international, double-blind, placebo-controlled PEGASUS trial of rilzabrutinib, a promising oral reversible Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The medication has a short half-life and a self-limited immunomodulatory effect. Moreover, the trial is set up for remote patient visits on an outpatient basis via teledermatology, so the 65-week study can continue despite the pandemic. Both newly diagnosed and relapsing patients are eligible for the trial, headed by Dr. Murrell. At AAD 2020 she reported encouraging results from a phase 2b trial of rilzabrutinib.

She is a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the PEGASUS trial, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

The Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Together with physicians from the Mayo Clinic, Alexandria (Egypt) University, and Tehran (Iran) University, she recently published updated expert guidance for treatment of this severe, potentially fatal mucocutaneous autoimmune blistering disease, in a letter to the editor in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. She presented some of the key recommendations at AAD 2020.

First off, rituximab (Rituxan), the only Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris and a biologic considered first-line therapy prepandemic, is ill-advised during the COVID-19 era. Its mechanism of benefit is through B-cell depletion. This is an irreversible effect, and reconstitution of B-cell immunity takes 6-12 months. The absence of this immunologic protection for such a long time poses potentially serious problems for pemphigus patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Also, the opportunity to administer intravenous infusions of the biologic becomes unpredictable during pandemic surges, when limitations on nonemergent medical care may be necessary, noted Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales and head of dermatology at St. George University Hospital, both in Sydney.

“We have taken the approach of postponing rituximab infusions temporarily, with the aim of delaying peak patient immunosuppression during peak COVID-19 incidence to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes,” Dr. Murrell and coauthors wrote in the letter (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jun;82[6]:e235-6).

The other traditional go-to therapy for pemphigus is corticosteroids. They’re effective, fast acting, and relatively inexpensive. But their nonselective immunosuppressive action boosts infection risk in general, and more specifically it increases the risk of developing severe forms of COVID-19 should a patient become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“A basic therapeutic principle with particular importance during the pandemic is that glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, should be tapered to the lowest effective dose. In active COVID-19 infection, immunosuppressive steroid-sparing medications should be discontinued when possible, although glucocorticoid cessation often cannot be considered due to risk for adrenal insufficiency,” the authors continued.

“Effective as adjuvant treatment in both pemphigus and COVID-19,intravenous immunoglobulin supports immunity and therefore may be useful in this setting,” they wrote. It’s not immunosuppressive, and, they noted, there’s good-quality evidence from a Japanese randomized, double-blind, controlled trial that a 5-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin is effective therapy for pemphigus (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Apr;60[4]:595-603).

Moreover, intravenous immunoglobulin is also reportedly effective in severe COVID-19 (Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102.).

Another option is to consider enrolling a patient with moderate or severe pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in the ongoing pivotal phase 3, international, double-blind, placebo-controlled PEGASUS trial of rilzabrutinib, a promising oral reversible Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The medication has a short half-life and a self-limited immunomodulatory effect. Moreover, the trial is set up for remote patient visits on an outpatient basis via teledermatology, so the 65-week study can continue despite the pandemic. Both newly diagnosed and relapsing patients are eligible for the trial, headed by Dr. Murrell. At AAD 2020 she reported encouraging results from a phase 2b trial of rilzabrutinib.

She is a consultant to Principia Biopharma, sponsor of the PEGASUS trial, and has received institutional research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM AAD 20

PD-1 Signaling in Extramammary Paget Disease

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

Resident Pearls

- Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, while secondary EMPD is an extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.

- Surgical margin clearance in EMPD often is problematic, with high recurrence rates indicating the need for additional treatment modalities.

- Programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD. Further studies and clinical trials are needed to test the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD.

How to not miss something

It’s a mad, mad, mad world. In California, we seem bent on swelling our curve. We’d just begun bringing our patients back into the office. We felt safe, back to business. Then air raid sirens again. Retreat to the Underground. Minimize waiting room waiting, convert to telephone and video. Do what we can to protect our patients and people.

As doctors, we’ve gotten proficient at being triage nurses, examining each appointment request, and sorting who should be seen in person and who could be cared for virtually. We do it for every clinic now.

My 11 a.m. patient last Thursday was an 83-year-old Filipino man with at least a 13-year history of hand dermatitis (based on his long electronic medical record). He had plenty of betamethasone refills. There were even photos of his large, brown hands in his chart. Grandpa hands, calloused by tending his garden and scarred from fixing bikes, building sheds, and doing oil changes for any nephew or niece who asked. The most recent uploads showed a bit of fingertip fissuring, some lichenified plaques. Not much different than they looked after planting persimmon trees a decade ago. I called him early that morning to offer a phone appointment. Perhaps I could save him from venturing out.

“I see that you have an appointment with me in a few hours. If you’d like, I might be able to help you by phone instead.” “Oh, thank you, doc,” he replied. “It’s so kind of you to call. But doc, I think maybe it is better if I come in to see you.” “Are you sure?” “Oh, yes. I will be careful.”

He checked in at 10:45. When I walked into the room he was wearing a face mask and a face shield – good job! He also had a cane and U.S. Navy Destroyer hat. And on the bottom left of his plastic shield was a sticker decal of a U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer, dress blue insignia. His hands looked just like the photos: no purpura, plenty of lentigines. Fissures, calluses, lichenified plaques. I touched them. In the unaffected areas, his skin was remarkably soft. What stories these hands told. “I was 20 years in the Navy, doc,” he said. “I would have stayed longer but my wife, who’s younger, wanted me back home.” He talked about his nine grandchildren, some of whom went on to join the navy too – but as officers, he noted with pride. Now he spends his days caring for his wife; she has dementia. He can’t stay long because she’s in the waiting room and is likely to get confused if alone for too long.

We quickly reviewed good hand care. I ordered clobetasol ointment. He was pleased; that seemed to work years ago and he was glad to have it again.

So, why did he need to come in? Clearly I could have done this remotely. “Thank you so much for seeing me, doc,” as he stood to walk out. “Proper inspections have to be done in person, right?” Yes, I thought. Otherwise, you might miss something.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It’s a mad, mad, mad world. In California, we seem bent on swelling our curve. We’d just begun bringing our patients back into the office. We felt safe, back to business. Then air raid sirens again. Retreat to the Underground. Minimize waiting room waiting, convert to telephone and video. Do what we can to protect our patients and people.

As doctors, we’ve gotten proficient at being triage nurses, examining each appointment request, and sorting who should be seen in person and who could be cared for virtually. We do it for every clinic now.

My 11 a.m. patient last Thursday was an 83-year-old Filipino man with at least a 13-year history of hand dermatitis (based on his long electronic medical record). He had plenty of betamethasone refills. There were even photos of his large, brown hands in his chart. Grandpa hands, calloused by tending his garden and scarred from fixing bikes, building sheds, and doing oil changes for any nephew or niece who asked. The most recent uploads showed a bit of fingertip fissuring, some lichenified plaques. Not much different than they looked after planting persimmon trees a decade ago. I called him early that morning to offer a phone appointment. Perhaps I could save him from venturing out.

“I see that you have an appointment with me in a few hours. If you’d like, I might be able to help you by phone instead.” “Oh, thank you, doc,” he replied. “It’s so kind of you to call. But doc, I think maybe it is better if I come in to see you.” “Are you sure?” “Oh, yes. I will be careful.”

He checked in at 10:45. When I walked into the room he was wearing a face mask and a face shield – good job! He also had a cane and U.S. Navy Destroyer hat. And on the bottom left of his plastic shield was a sticker decal of a U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer, dress blue insignia. His hands looked just like the photos: no purpura, plenty of lentigines. Fissures, calluses, lichenified plaques. I touched them. In the unaffected areas, his skin was remarkably soft. What stories these hands told. “I was 20 years in the Navy, doc,” he said. “I would have stayed longer but my wife, who’s younger, wanted me back home.” He talked about his nine grandchildren, some of whom went on to join the navy too – but as officers, he noted with pride. Now he spends his days caring for his wife; she has dementia. He can’t stay long because she’s in the waiting room and is likely to get confused if alone for too long.

We quickly reviewed good hand care. I ordered clobetasol ointment. He was pleased; that seemed to work years ago and he was glad to have it again.

So, why did he need to come in? Clearly I could have done this remotely. “Thank you so much for seeing me, doc,” as he stood to walk out. “Proper inspections have to be done in person, right?” Yes, I thought. Otherwise, you might miss something.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It’s a mad, mad, mad world. In California, we seem bent on swelling our curve. We’d just begun bringing our patients back into the office. We felt safe, back to business. Then air raid sirens again. Retreat to the Underground. Minimize waiting room waiting, convert to telephone and video. Do what we can to protect our patients and people.

As doctors, we’ve gotten proficient at being triage nurses, examining each appointment request, and sorting who should be seen in person and who could be cared for virtually. We do it for every clinic now.

My 11 a.m. patient last Thursday was an 83-year-old Filipino man with at least a 13-year history of hand dermatitis (based on his long electronic medical record). He had plenty of betamethasone refills. There were even photos of his large, brown hands in his chart. Grandpa hands, calloused by tending his garden and scarred from fixing bikes, building sheds, and doing oil changes for any nephew or niece who asked. The most recent uploads showed a bit of fingertip fissuring, some lichenified plaques. Not much different than they looked after planting persimmon trees a decade ago. I called him early that morning to offer a phone appointment. Perhaps I could save him from venturing out.

“I see that you have an appointment with me in a few hours. If you’d like, I might be able to help you by phone instead.” “Oh, thank you, doc,” he replied. “It’s so kind of you to call. But doc, I think maybe it is better if I come in to see you.” “Are you sure?” “Oh, yes. I will be careful.”

He checked in at 10:45. When I walked into the room he was wearing a face mask and a face shield – good job! He also had a cane and U.S. Navy Destroyer hat. And on the bottom left of his plastic shield was a sticker decal of a U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer, dress blue insignia. His hands looked just like the photos: no purpura, plenty of lentigines. Fissures, calluses, lichenified plaques. I touched them. In the unaffected areas, his skin was remarkably soft. What stories these hands told. “I was 20 years in the Navy, doc,” he said. “I would have stayed longer but my wife, who’s younger, wanted me back home.” He talked about his nine grandchildren, some of whom went on to join the navy too – but as officers, he noted with pride. Now he spends his days caring for his wife; she has dementia. He can’t stay long because she’s in the waiting room and is likely to get confused if alone for too long.

We quickly reviewed good hand care. I ordered clobetasol ointment. He was pleased; that seemed to work years ago and he was glad to have it again.

So, why did he need to come in? Clearly I could have done this remotely. “Thank you so much for seeing me, doc,” as he stood to walk out. “Proper inspections have to be done in person, right?” Yes, I thought. Otherwise, you might miss something.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Creating a student-staffed family call line to alleviate clinical burden

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

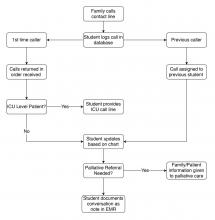

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

AGA News

Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-Wash.) leads prior authorization reform

As a member of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, which has jurisdiction over the Medicare program, Rep. DelBene has worked closely with the American Gastroenterological Association.

When Rep. DelBene was first elected to Congress in 2012, we met with her to share AGA’s policy priorities. We knew instantly that we had a voice for many of our issues. Rep. DelBene started her career as a young investigator before continuing her education and launching a career in the biotechnology industry. From her firsthand experience, she understands the need for investments in National Institutes of Health research and for access to and coverage of colorectal cancer screenings since a member of her family had the disease.

Since Rep. DelBene has been in office, she has taken the lead on several policy priorities affecting our profession, including patient access and protections and regulatory relief. Rep. DelBene is the lead Democratic sponsor of H.R. 3107, the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act, legislation that would streamline prior authorization in Medicare Advantage plans. The legislation hit a milestone of securing 218 cosponsors in the House, which is a majority of the members. We look forward to continuing to work with Rep. DelBene on advancing AGA’s policy priorities.

Featured microbiome investigator: Josephine Ni, MD

We’re checking in with a rising star in microbiome research: Dr. Josephine Ni from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dr. Ni is an instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and 2017 recipient of the AGA–Takeda Pharmaceuticals Research Scholar Award in IBD from the AGA Research Foundation.

Congrats to Dr. Ni! While Dr. Ni’s AGA Research Scholar Award concludes at the end of June 2020, we’re proud to share that she has secured two significant grants to continue her work: an NIH KO8 grant and a Burroughs Welcome Fund Award. We catch up with Dr. Ni in the Q&A below.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

I am interested in better understanding bacterial colonization of the healthy and inflamed intestinal tract; specifically, my current research focuses on characterizing the role of biofilm formation on intestinal colonization.

What effect do you hope your research will have on patients?

I hope that my work on understanding intestinal colonization will allow us to engineer the microbiota in predictable ways, which will pave the way to exclude enteropathogens, deliver specific compounds, and prevent dysbiosis.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?