User login

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

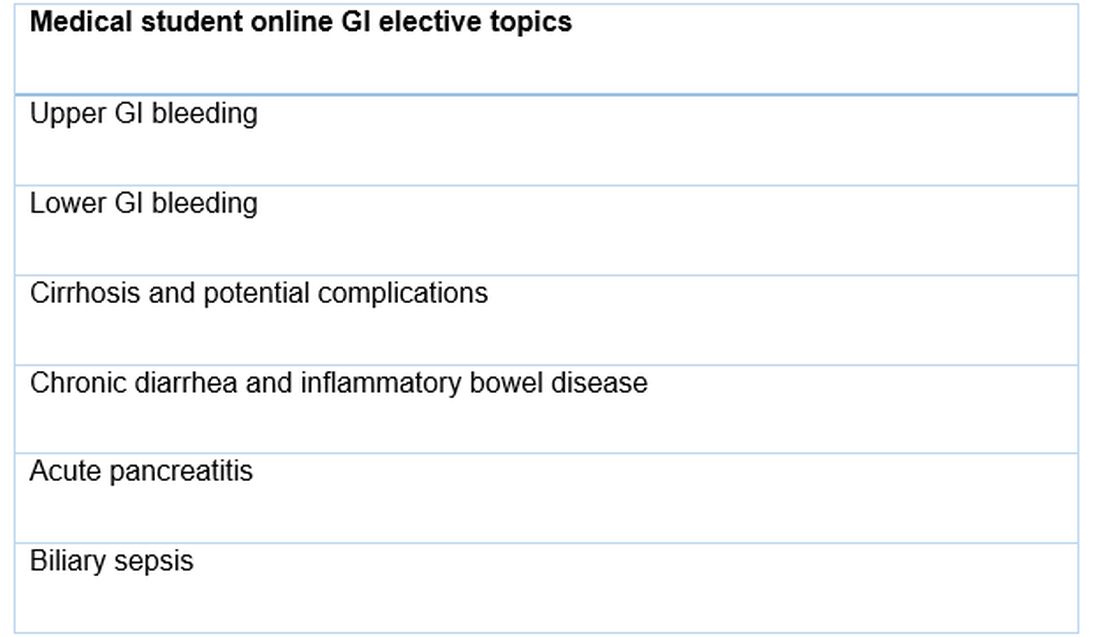

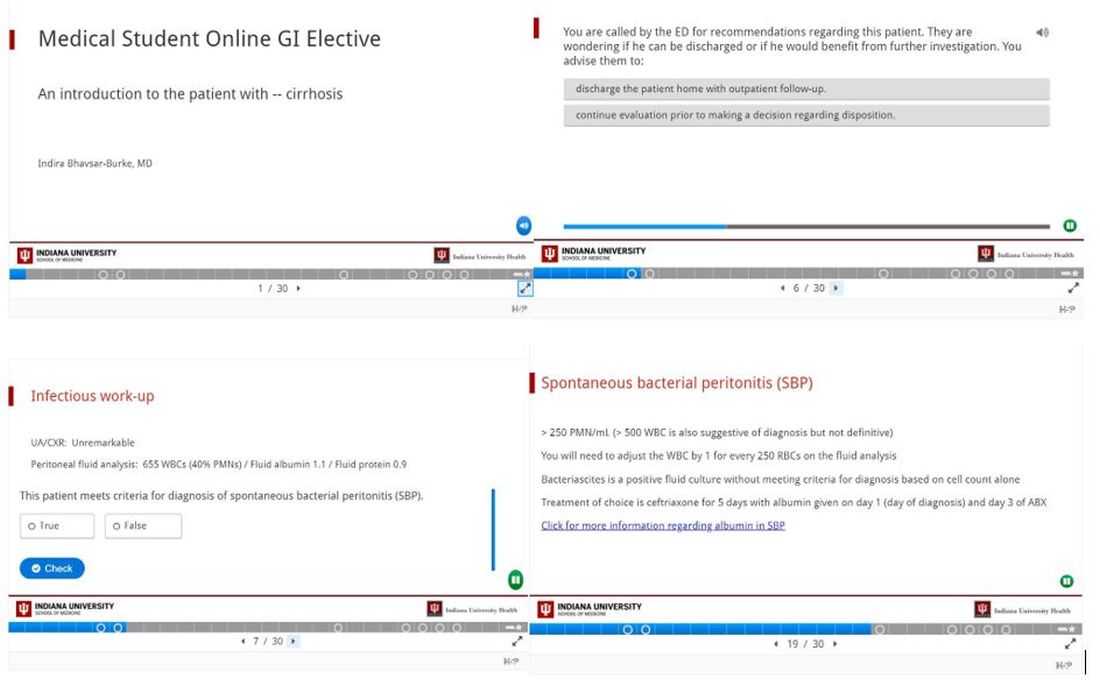

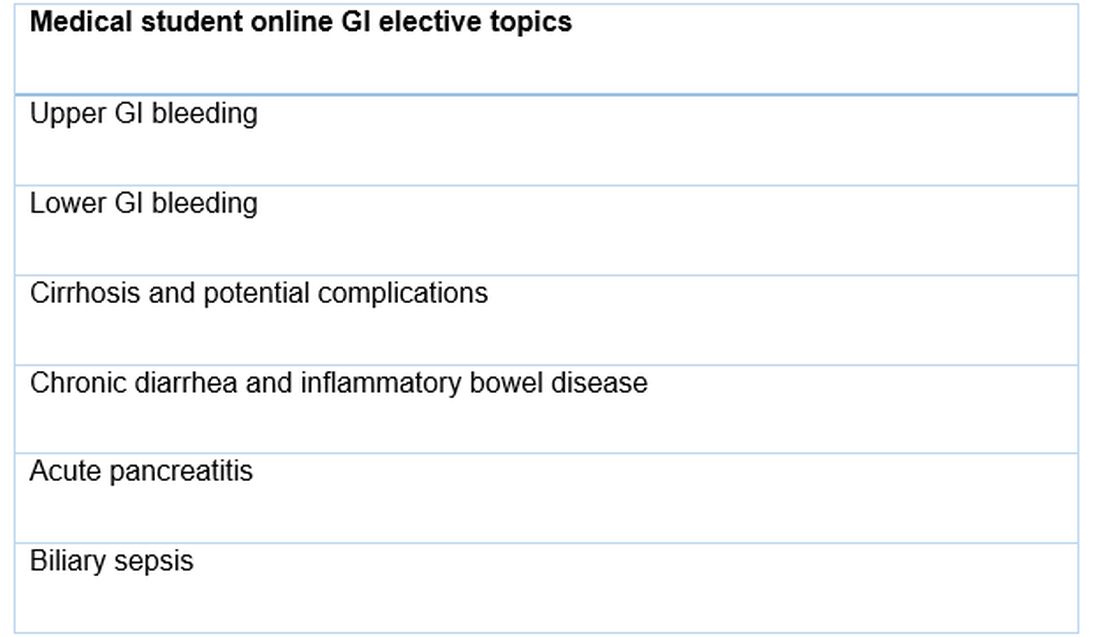

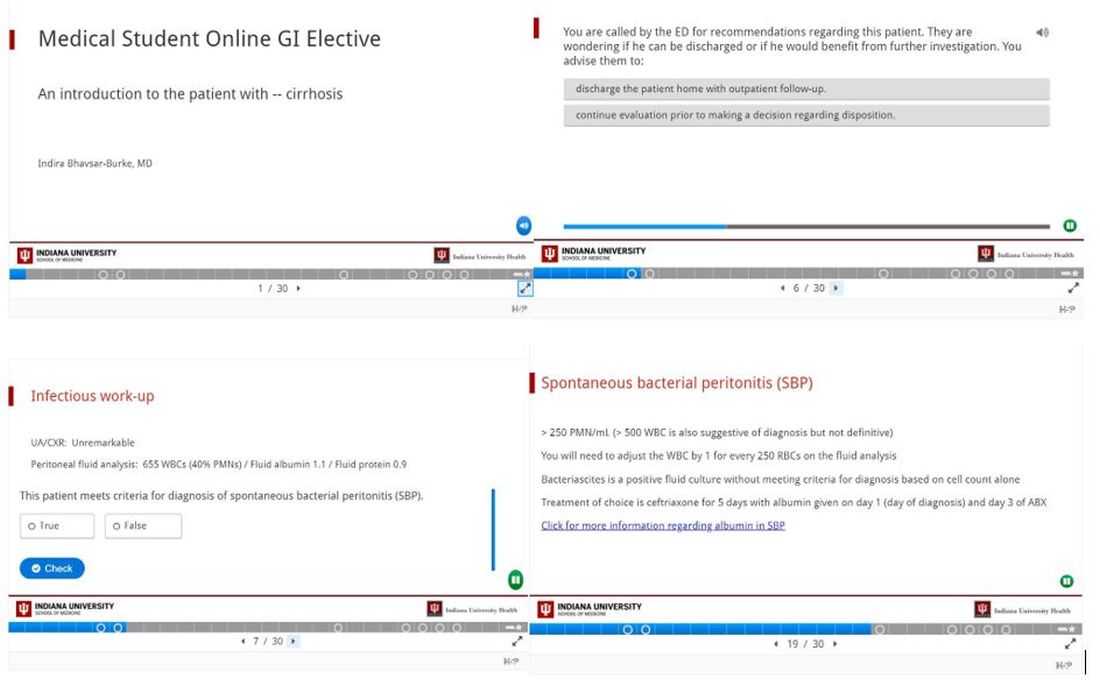

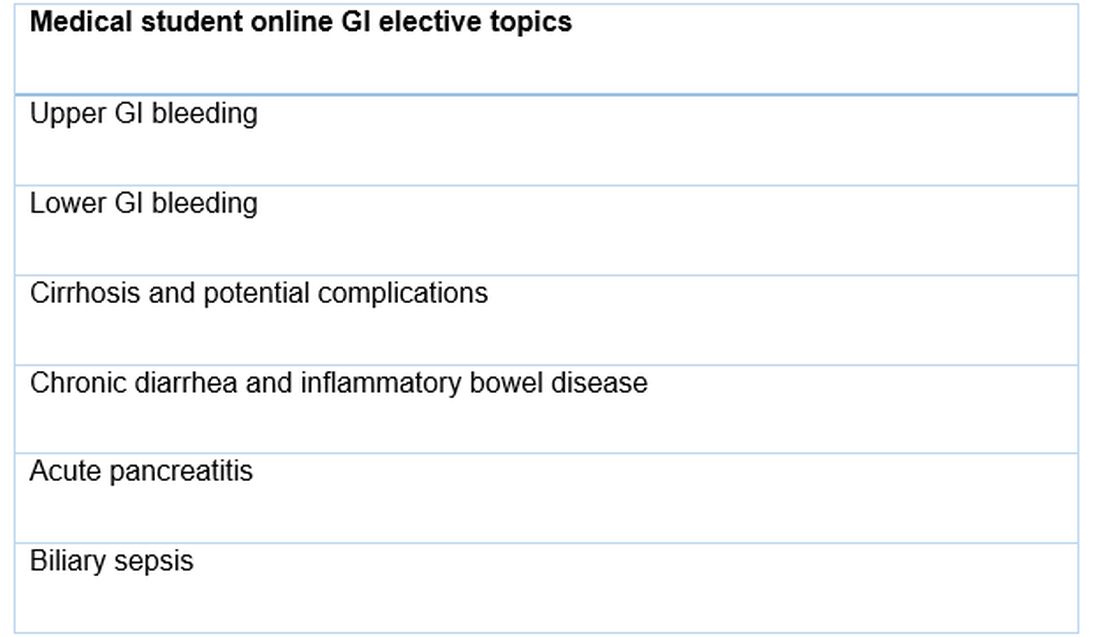

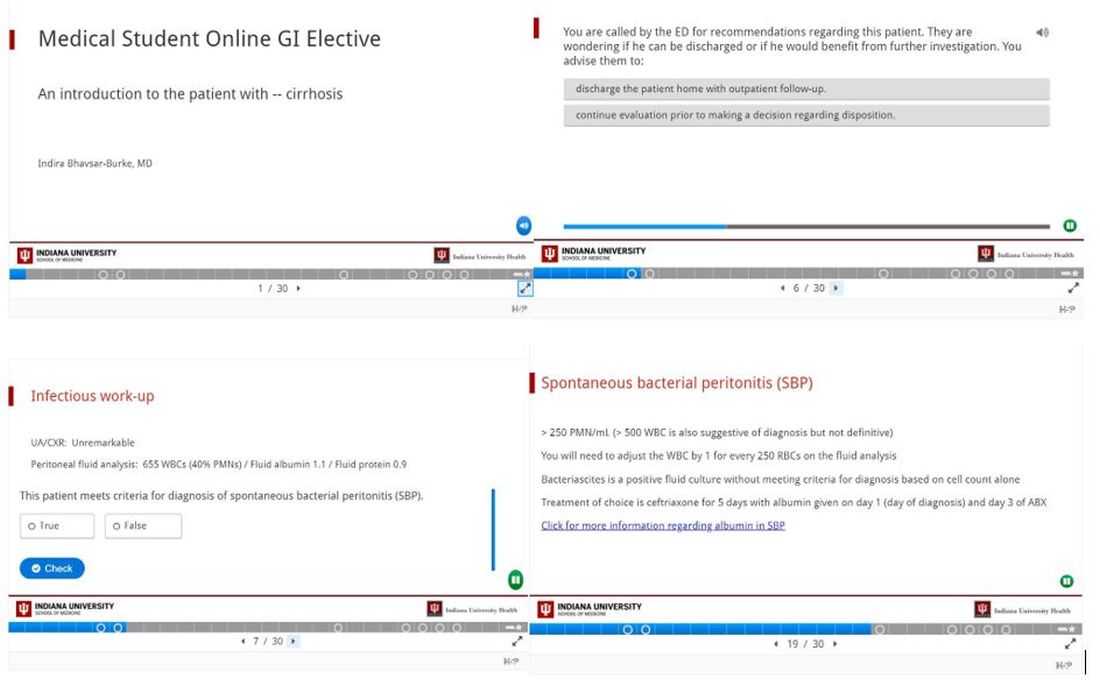

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.