User login

For MD-IQ use only

Asymptomatic Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Nevus Comedonicus

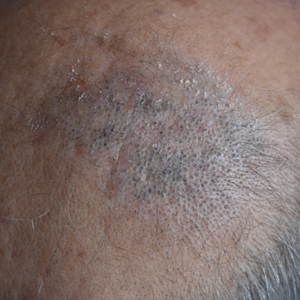

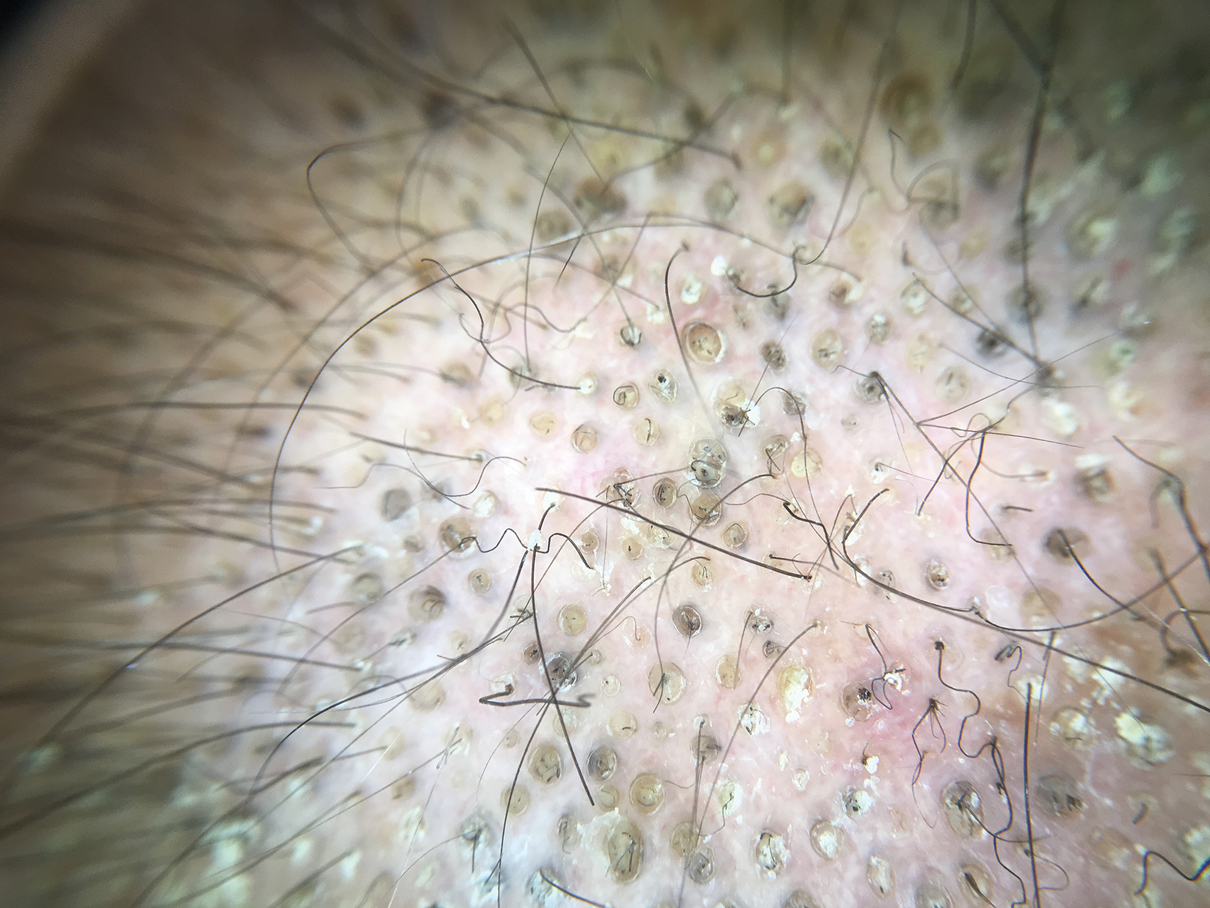

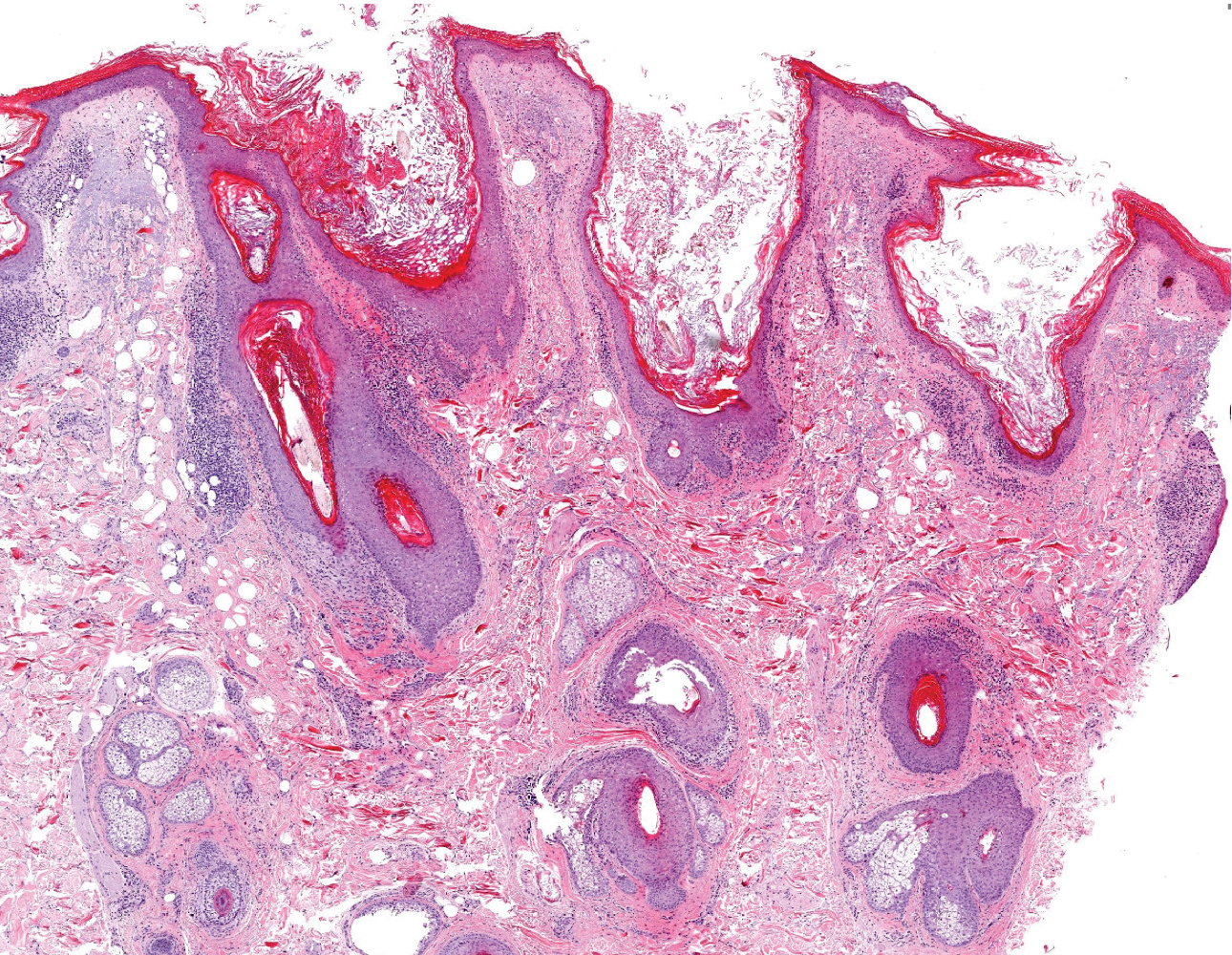

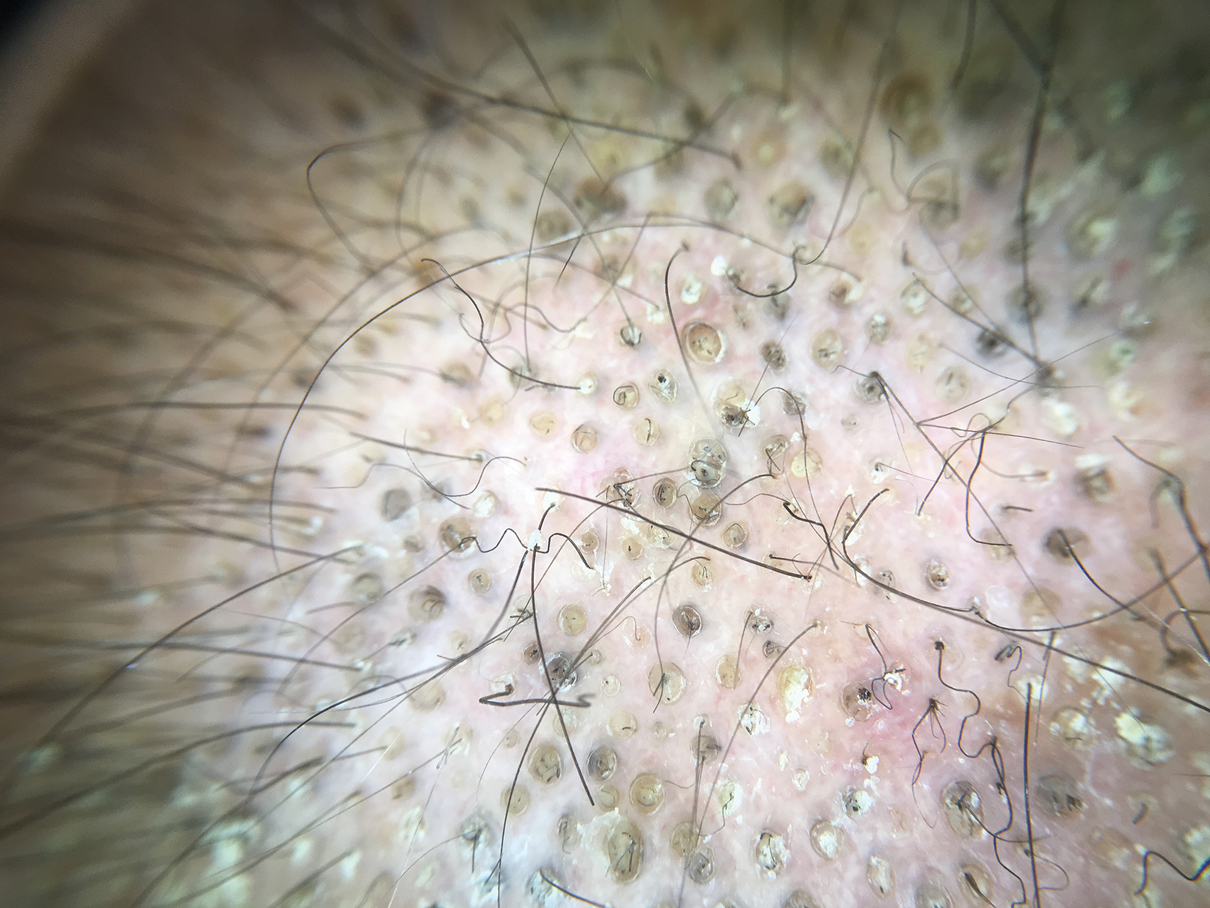

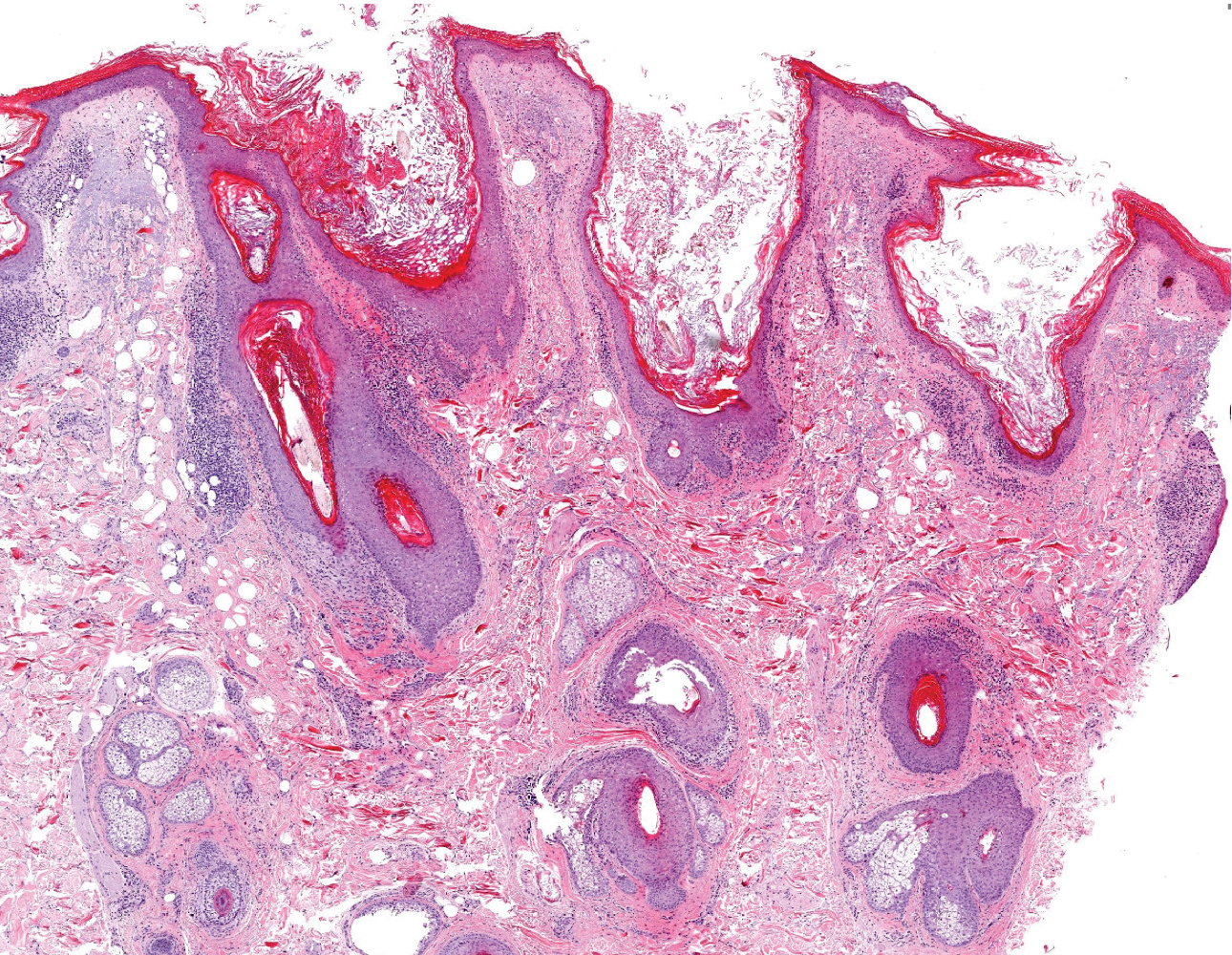

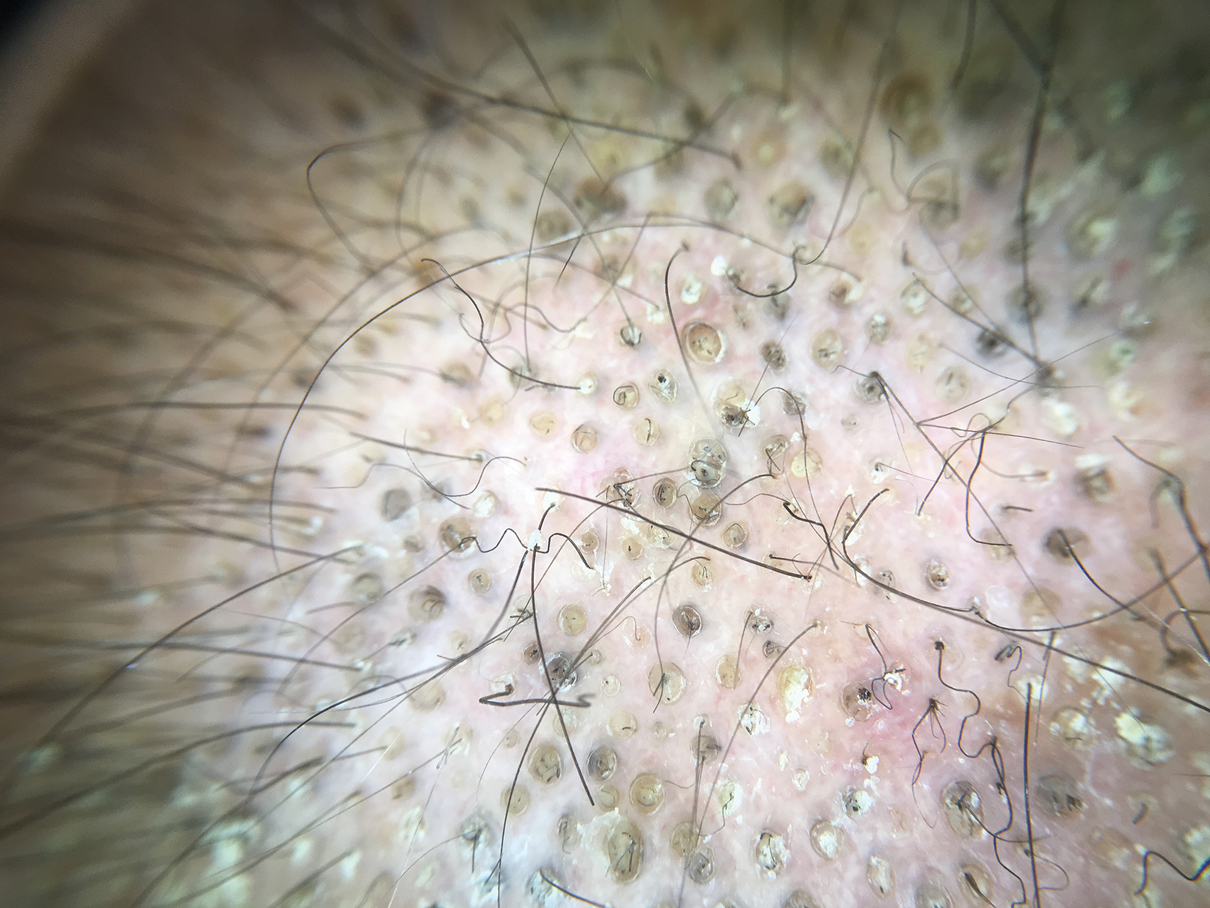

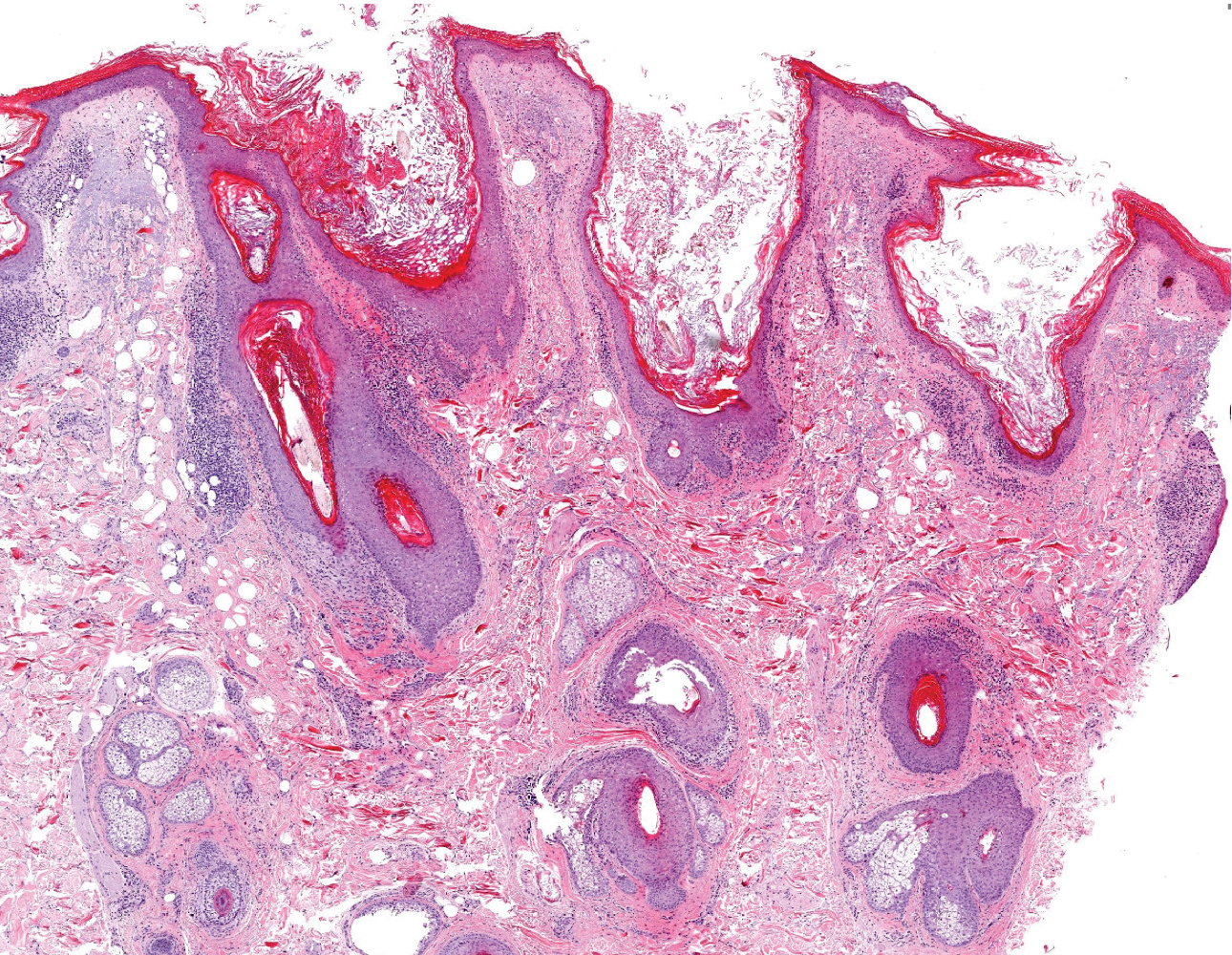

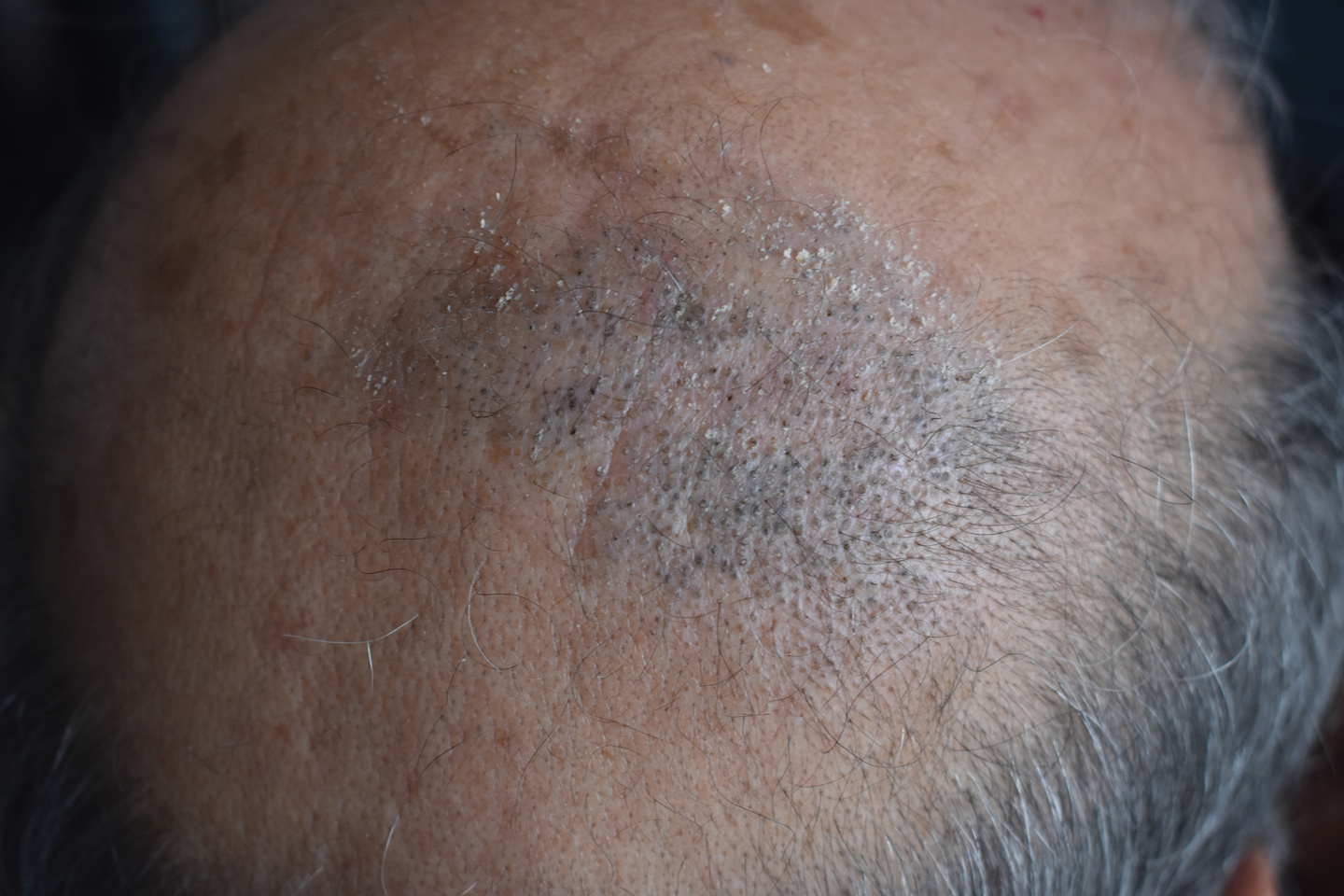

Dermoscopy showed multiple dilated follicular openings plugged with keratinous material (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed dilated follicular infundibula with dilation and orthokeratotic plugging (Figure 2). Routine laboratory tests including complete blood cell count and blood chemistry were within reference range. Thus, on the basis of clinical, dermoscopy, and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of nevus comedonicus (NC) was made. The patient refused treatment for cosmetic reasons.

Nevus comedonicus is a rare hamartoma first described by Kofmann1 in 1895. It is thought to be a developmental defect of the pilosebaceous unit; the resulting structure is unable to produce mature hairs, matrix cells, or sebaceous glands and is capable only of forming soft keratin.2 Clinically, it is characterized by closely grouped papules with hyperkeratotic plugs that mimic comedones. It has a predilection for the face, neck, and trunk area. Nevertheless, scalp involvement rarely has been reported in the literature.2-4 Nevus comedonicus usually appears at birth or during childhood and generally is asymptomatic; however, an inflammatory variant of NC with cyst formation and recurrent infections also has been described.5 Moreover, a syndromic variant was reported and characterized by a combination of NC with ocular, skeletal, or neurological defects.5 Most lesions grow proportionately with age and usually stabilize by late adolescence.2 Our patient's plaque increased in size with age. No triggering factors were found. Although NC usually has a benign course, squamous cell carcinoma arising in NC has been reported.6 Consequently, routine surveillance is necessary.

Diagnosis often is easily made by considering the characteristic morphology of the lesions and the early age of its appearance. However, in atypical NC presentations, acne, seborrheic keratosis, porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, Favre-Racouchot syndrome, or familial dyskeratotic comedones should be considered. Dermoscopy has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of NC. Typical dermoscopy findings are numerous circular and barrel-shaped homogenous areas in light and dark brown shades with remarkable keratin plugs.7,8

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is a variant of mycosis fungoides characterized by hair follicle invasion of mature, CD4+, small, lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei.9 Patients may present with grouped follicular papules that preferentially involve the head and neck area. It typically occurs in adults but occasionally may affect children. Histopathology is characterized by the presence of folliculotropic infiltrates with variable infiltration of the follicular epithelium, often with sparing of the epidermis. Familial dyskeratotic comedones, rare autosomal-dominant genodermatoses, clinically are characterized by symmetrically scattered comedonelike hyperkeratotic papules. These lesions appear around puberty and show a predilection for the trunk, arms, and face. Histopathology reveals craterlike invaginations filled with keratinous material and evidence of dyskeratosis. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus is a rare adnexal hamartoma with eccrine differentiation. It is characterized by asymptomatic grouped keratotic papules and plaques. The lesions usually present at birth or in childhood and favor the palms and soles. Widespread involvement along Blaschko lines also can occur. Cornoid lamella involving an eccrine duct is the characteristic histopathologic feature of this condition.9

Treatment of NC is essentially reserved for cosmetic reasons or when there are complications such as discomfort or infection. Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical retinoids, and keratolytic agents such as ammonium lactate or salicylic acid.10 The use of oral isotretinoin is controversial.2 Surgical excision is useful for localized lesions. Nevus comedonicus, especially occurring at unusual sites such as the scalp, is uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to reach a diagnosis.

- Kofmann S. Ein fall von seltener localisation und verbreitiing von comedonen. Arch Derm Syph. 1895;32:177-178.

- Sikorski D, Parker J, Shwayder T. A boy with an unusual scalp birthmark. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:670-672.

- Ghaninezhad H, Ehsani AH, Mansoori P, et al. Naevus comedonicus of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:184-185.

- Kikkeri N, Priyanka R, Parshawanath H. Nevus comedonicus on scalp: a rare site. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22.

- Walling HW, Swick BL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in nevus comedonicus. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:144-146.

- Kamin´ska-Winciorek G, S´piewak R. Dermoscopy on nevus comedonicus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:252-254.

- Vora R, Kota R, Sheth N. Dermoscopy of nevus comedonicus. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:388.

- Wang NS, Meola T, Orlow SJ, et al. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:582-586.

- Ferrari B, Taliercio V, Restrepo P, et al. Nevus comedonicus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:216-219

The Diagnosis: Nevus Comedonicus

Dermoscopy showed multiple dilated follicular openings plugged with keratinous material (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed dilated follicular infundibula with dilation and orthokeratotic plugging (Figure 2). Routine laboratory tests including complete blood cell count and blood chemistry were within reference range. Thus, on the basis of clinical, dermoscopy, and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of nevus comedonicus (NC) was made. The patient refused treatment for cosmetic reasons.

Nevus comedonicus is a rare hamartoma first described by Kofmann1 in 1895. It is thought to be a developmental defect of the pilosebaceous unit; the resulting structure is unable to produce mature hairs, matrix cells, or sebaceous glands and is capable only of forming soft keratin.2 Clinically, it is characterized by closely grouped papules with hyperkeratotic plugs that mimic comedones. It has a predilection for the face, neck, and trunk area. Nevertheless, scalp involvement rarely has been reported in the literature.2-4 Nevus comedonicus usually appears at birth or during childhood and generally is asymptomatic; however, an inflammatory variant of NC with cyst formation and recurrent infections also has been described.5 Moreover, a syndromic variant was reported and characterized by a combination of NC with ocular, skeletal, or neurological defects.5 Most lesions grow proportionately with age and usually stabilize by late adolescence.2 Our patient's plaque increased in size with age. No triggering factors were found. Although NC usually has a benign course, squamous cell carcinoma arising in NC has been reported.6 Consequently, routine surveillance is necessary.

Diagnosis often is easily made by considering the characteristic morphology of the lesions and the early age of its appearance. However, in atypical NC presentations, acne, seborrheic keratosis, porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, Favre-Racouchot syndrome, or familial dyskeratotic comedones should be considered. Dermoscopy has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of NC. Typical dermoscopy findings are numerous circular and barrel-shaped homogenous areas in light and dark brown shades with remarkable keratin plugs.7,8

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is a variant of mycosis fungoides characterized by hair follicle invasion of mature, CD4+, small, lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei.9 Patients may present with grouped follicular papules that preferentially involve the head and neck area. It typically occurs in adults but occasionally may affect children. Histopathology is characterized by the presence of folliculotropic infiltrates with variable infiltration of the follicular epithelium, often with sparing of the epidermis. Familial dyskeratotic comedones, rare autosomal-dominant genodermatoses, clinically are characterized by symmetrically scattered comedonelike hyperkeratotic papules. These lesions appear around puberty and show a predilection for the trunk, arms, and face. Histopathology reveals craterlike invaginations filled with keratinous material and evidence of dyskeratosis. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus is a rare adnexal hamartoma with eccrine differentiation. It is characterized by asymptomatic grouped keratotic papules and plaques. The lesions usually present at birth or in childhood and favor the palms and soles. Widespread involvement along Blaschko lines also can occur. Cornoid lamella involving an eccrine duct is the characteristic histopathologic feature of this condition.9

Treatment of NC is essentially reserved for cosmetic reasons or when there are complications such as discomfort or infection. Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical retinoids, and keratolytic agents such as ammonium lactate or salicylic acid.10 The use of oral isotretinoin is controversial.2 Surgical excision is useful for localized lesions. Nevus comedonicus, especially occurring at unusual sites such as the scalp, is uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to reach a diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Comedonicus

Dermoscopy showed multiple dilated follicular openings plugged with keratinous material (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed dilated follicular infundibula with dilation and orthokeratotic plugging (Figure 2). Routine laboratory tests including complete blood cell count and blood chemistry were within reference range. Thus, on the basis of clinical, dermoscopy, and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of nevus comedonicus (NC) was made. The patient refused treatment for cosmetic reasons.

Nevus comedonicus is a rare hamartoma first described by Kofmann1 in 1895. It is thought to be a developmental defect of the pilosebaceous unit; the resulting structure is unable to produce mature hairs, matrix cells, or sebaceous glands and is capable only of forming soft keratin.2 Clinically, it is characterized by closely grouped papules with hyperkeratotic plugs that mimic comedones. It has a predilection for the face, neck, and trunk area. Nevertheless, scalp involvement rarely has been reported in the literature.2-4 Nevus comedonicus usually appears at birth or during childhood and generally is asymptomatic; however, an inflammatory variant of NC with cyst formation and recurrent infections also has been described.5 Moreover, a syndromic variant was reported and characterized by a combination of NC with ocular, skeletal, or neurological defects.5 Most lesions grow proportionately with age and usually stabilize by late adolescence.2 Our patient's plaque increased in size with age. No triggering factors were found. Although NC usually has a benign course, squamous cell carcinoma arising in NC has been reported.6 Consequently, routine surveillance is necessary.

Diagnosis often is easily made by considering the characteristic morphology of the lesions and the early age of its appearance. However, in atypical NC presentations, acne, seborrheic keratosis, porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus, folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, Favre-Racouchot syndrome, or familial dyskeratotic comedones should be considered. Dermoscopy has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of NC. Typical dermoscopy findings are numerous circular and barrel-shaped homogenous areas in light and dark brown shades with remarkable keratin plugs.7,8

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is a variant of mycosis fungoides characterized by hair follicle invasion of mature, CD4+, small, lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei.9 Patients may present with grouped follicular papules that preferentially involve the head and neck area. It typically occurs in adults but occasionally may affect children. Histopathology is characterized by the presence of folliculotropic infiltrates with variable infiltration of the follicular epithelium, often with sparing of the epidermis. Familial dyskeratotic comedones, rare autosomal-dominant genodermatoses, clinically are characterized by symmetrically scattered comedonelike hyperkeratotic papules. These lesions appear around puberty and show a predilection for the trunk, arms, and face. Histopathology reveals craterlike invaginations filled with keratinous material and evidence of dyskeratosis. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus is a rare adnexal hamartoma with eccrine differentiation. It is characterized by asymptomatic grouped keratotic papules and plaques. The lesions usually present at birth or in childhood and favor the palms and soles. Widespread involvement along Blaschko lines also can occur. Cornoid lamella involving an eccrine duct is the characteristic histopathologic feature of this condition.9

Treatment of NC is essentially reserved for cosmetic reasons or when there are complications such as discomfort or infection. Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical retinoids, and keratolytic agents such as ammonium lactate or salicylic acid.10 The use of oral isotretinoin is controversial.2 Surgical excision is useful for localized lesions. Nevus comedonicus, especially occurring at unusual sites such as the scalp, is uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to reach a diagnosis.

- Kofmann S. Ein fall von seltener localisation und verbreitiing von comedonen. Arch Derm Syph. 1895;32:177-178.

- Sikorski D, Parker J, Shwayder T. A boy with an unusual scalp birthmark. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:670-672.

- Ghaninezhad H, Ehsani AH, Mansoori P, et al. Naevus comedonicus of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:184-185.

- Kikkeri N, Priyanka R, Parshawanath H. Nevus comedonicus on scalp: a rare site. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22.

- Walling HW, Swick BL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in nevus comedonicus. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:144-146.

- Kamin´ska-Winciorek G, S´piewak R. Dermoscopy on nevus comedonicus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:252-254.

- Vora R, Kota R, Sheth N. Dermoscopy of nevus comedonicus. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:388.

- Wang NS, Meola T, Orlow SJ, et al. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:582-586.

- Ferrari B, Taliercio V, Restrepo P, et al. Nevus comedonicus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:216-219

- Kofmann S. Ein fall von seltener localisation und verbreitiing von comedonen. Arch Derm Syph. 1895;32:177-178.

- Sikorski D, Parker J, Shwayder T. A boy with an unusual scalp birthmark. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:670-672.

- Ghaninezhad H, Ehsani AH, Mansoori P, et al. Naevus comedonicus of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:184-185.

- Kikkeri N, Priyanka R, Parshawanath H. Nevus comedonicus on scalp: a rare site. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:105.

- Happle R. The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1-22.

- Walling HW, Swick BL. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in nevus comedonicus. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:144-146.

- Kamin´ska-Winciorek G, S´piewak R. Dermoscopy on nevus comedonicus: a case report and review of the literature. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:252-254.

- Vora R, Kota R, Sheth N. Dermoscopy of nevus comedonicus. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:388.

- Wang NS, Meola T, Orlow SJ, et al. Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:582-586.

- Ferrari B, Taliercio V, Restrepo P, et al. Nevus comedonicus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:216-219

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with an asymptomatic plaque on the scalp that had been present since childhood. The size of the plaque gradually progressed initially but had notably increased in size in the last 6 months. There was no association with trauma or irritation. There was no family history of similar lesions. Physical examination revealed a 3.0×2.5-cm plaque on the vertex of the scalp consisting of aggregated pits plugged with keratinous material resembling comedones. There were no lesions elsewhere on the body. Dermoscopy and a 4-mm punch biopsy were performed.

Is your job performance being evaluated for the wrong factors?

Most physicians get an annual performance review, and may be either elated, disappointed, or confused with their rating.

But some physicians say the right factors aren’t being evaluated or, in many cases, the performance measures promote efforts that are counterproductive.

“Bonuses are a behaviorist approach,” said Richard Gunderman, MD, professor in the schools of medicine, liberal arts, and philanthropy at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “The presumption is that people will change if they get some money – that they will do what the incentive wants them to do and refrain from what it doesn’t want them to do.”

Dr. Gunderman said this often means just going through the motions to get the bonus, and not sharing goals that only the administration cares about. “The goals might be to lower costs, ensure compliance with regulations or billing requirements, or make patterns of care more uniform. These are not changes that are well tailored to what patients want or how doctors think.”

The bonus is a central feature of the annual review. Merritt Hawkins, the physician search firm, reported that 75% of the physician jobs that it searches for involve some kind of production bonus. Bonuses often make up at least 5% of total compensation, but they can be quite hefty in some specialties.

Having to fulfill measures that they’re not excited about can lead physicians to feel disengaged from their work, Dr. Gunderman said. And this disengagement can contribute to physician burnout, which has climbed to very high rates in recent years.

A 2018 paper by two physician leadership experts explored this problem with bonuses. “A growing consensus [of experts] suggests that quality-incentive pay isn’t paying the dividends first envisioned,” they wrote.

The problem is that the measurements tied to a bonus represent an extrinsic motivation – involving goals that doctors don’t really believe in. Instead, physicians need to be intrinsically motivated. They need to be inspired “to manage their own lives,” “to get better at something,” and “to be a part of a larger cause,” they wrote.

How to develop a better review process

“The best way to motivate improved performance is through purpose and mission,” said Robert Pearl, MD, former CEO of the Permanente Medical Group in California and now a lecturer on strategy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The review process, Dr. Pearl said, should inspire physicians to do better. The doctors should be asking themselves: “How well did we do in helping maximize the health of all of our patients? And how well did we do in avoiding medical errors, preventing complications, meeting the needs of our patients, and achieving superior quality outcomes?”

When he was CEO of Permanente, the huge physician group that works exclusively for health maintenance organization Kaiser, Dr. Pearl and fellow leaders revamped the review system that all Permanente physicians undergo.

First, the Permanente executives provided all physicians with everyone’s patient-satisfaction data, including their own. That way, each physician could compare performance with others and assess strengths and weaknesses. Then Permanente offered educational programs so that physicians could get help in meeting their goals.

“This approach helped improve quality of care, patient satisfaction, and fulfillment of physicians,” Dr. Pearl said. Kaiser Permanente earned the highest health plan member satisfaction rating by J.D. Power and higher rankings by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Permanente does not base the bonus on relative value units but on performance measures that are carefully balanced to avoid too much focus on certain measures. “There needs to be an array of quality measures because doctors deal with a complex set of problems,” Dr. Pearl said. For example, a primary care physician at Permanente is assessed on about 30 different measures.

Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration. Dr. Pearl said.

Although Permanente physicians are compared with each other, they are not pitted against each other but rather are asked to collaborate. “Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration,” he said. “They can teach each other. You can be good at some things, and your colleague can be good at others.”

Permanente still has one-on-one yearly evaluations, but much of the assessment work is done in monthly meetings within each department. “There, small groups of doctors look at their data and discuss how each of them can improve,” Dr. Pearl noted.

The 360-degree review is valuable but has some problems

Physicians should be getting a lot more feedback about their behavior than they are actually getting, according to Milton Hammerly, MD, chief medical officer at QualChoice Health Insurance in Little Rock, Ark.

“After residency, you get very little feedback on your work,” said Dr. Hammerly, who used to work for a hospital system. “Annual reviews for physicians focus almost exclusively on outcomes, productivity, and quality metrics, but not on people skills, what is called ‘emotional intelligence.’ ”

Dr. Hammerly said he saw the consequence of this lack of education when he was vice president for medical affairs at the hospital system. He was constantly dealing with physicians who exhibited serious disruptive behavior and had to be disciplined. “If only they had gotten a little help earlier on,” he noted.

Dr. Hammerly said that 360-degree evaluations, which are common in corporations but rarely used for physicians, could benefit the profession. He discovered the 360-degree evaluation when it was used for him at QualChoice, and he has been a fan ever since.

The approach involves collecting evaluations of you from your boss, your peers, and from people who work for you. That is, from 360 degrees around you. These people are asked to rate your strengths and weaknesses in a variety of competencies. In this way, you get feedback from all of your work relationships, not just from your boss.

Ideally, the evaluators are anonymous, and the subject works with a facilitator to process the information. But 360-degree evaluations can be done in all kinds of ways.

Critics of the 360-degree evaluations say the usual anonymity of evaluators allows them to be too harsh. Also, evaluators may be too subjective: What they say about you says more about their own perspective than anything about you.

But many people think 360-degree evaluations are at least going in the right direction, because they focus on people skills rather than just meeting metrics.

Robert Centor, MD, an internist in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of the performance measures committee of the American College of Physicians, said the best way to improve performance is to have conversations about your work with colleagues on the department level. “For example, 20 doctors could meet to discuss a certain issue, such as the need for more vaccinations. That doesn’t have to get rewarded with a bonus payment.”

Dr. Pearl said that “doctors need feedback from their colleagues. Without feedback, how else do you get better? You can only improve if you can know how you’re performing, compared to others.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians get an annual performance review, and may be either elated, disappointed, or confused with their rating.

But some physicians say the right factors aren’t being evaluated or, in many cases, the performance measures promote efforts that are counterproductive.

“Bonuses are a behaviorist approach,” said Richard Gunderman, MD, professor in the schools of medicine, liberal arts, and philanthropy at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “The presumption is that people will change if they get some money – that they will do what the incentive wants them to do and refrain from what it doesn’t want them to do.”

Dr. Gunderman said this often means just going through the motions to get the bonus, and not sharing goals that only the administration cares about. “The goals might be to lower costs, ensure compliance with regulations or billing requirements, or make patterns of care more uniform. These are not changes that are well tailored to what patients want or how doctors think.”

The bonus is a central feature of the annual review. Merritt Hawkins, the physician search firm, reported that 75% of the physician jobs that it searches for involve some kind of production bonus. Bonuses often make up at least 5% of total compensation, but they can be quite hefty in some specialties.

Having to fulfill measures that they’re not excited about can lead physicians to feel disengaged from their work, Dr. Gunderman said. And this disengagement can contribute to physician burnout, which has climbed to very high rates in recent years.

A 2018 paper by two physician leadership experts explored this problem with bonuses. “A growing consensus [of experts] suggests that quality-incentive pay isn’t paying the dividends first envisioned,” they wrote.

The problem is that the measurements tied to a bonus represent an extrinsic motivation – involving goals that doctors don’t really believe in. Instead, physicians need to be intrinsically motivated. They need to be inspired “to manage their own lives,” “to get better at something,” and “to be a part of a larger cause,” they wrote.

How to develop a better review process

“The best way to motivate improved performance is through purpose and mission,” said Robert Pearl, MD, former CEO of the Permanente Medical Group in California and now a lecturer on strategy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The review process, Dr. Pearl said, should inspire physicians to do better. The doctors should be asking themselves: “How well did we do in helping maximize the health of all of our patients? And how well did we do in avoiding medical errors, preventing complications, meeting the needs of our patients, and achieving superior quality outcomes?”

When he was CEO of Permanente, the huge physician group that works exclusively for health maintenance organization Kaiser, Dr. Pearl and fellow leaders revamped the review system that all Permanente physicians undergo.

First, the Permanente executives provided all physicians with everyone’s patient-satisfaction data, including their own. That way, each physician could compare performance with others and assess strengths and weaknesses. Then Permanente offered educational programs so that physicians could get help in meeting their goals.

“This approach helped improve quality of care, patient satisfaction, and fulfillment of physicians,” Dr. Pearl said. Kaiser Permanente earned the highest health plan member satisfaction rating by J.D. Power and higher rankings by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Permanente does not base the bonus on relative value units but on performance measures that are carefully balanced to avoid too much focus on certain measures. “There needs to be an array of quality measures because doctors deal with a complex set of problems,” Dr. Pearl said. For example, a primary care physician at Permanente is assessed on about 30 different measures.

Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration. Dr. Pearl said.

Although Permanente physicians are compared with each other, they are not pitted against each other but rather are asked to collaborate. “Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration,” he said. “They can teach each other. You can be good at some things, and your colleague can be good at others.”

Permanente still has one-on-one yearly evaluations, but much of the assessment work is done in monthly meetings within each department. “There, small groups of doctors look at their data and discuss how each of them can improve,” Dr. Pearl noted.

The 360-degree review is valuable but has some problems

Physicians should be getting a lot more feedback about their behavior than they are actually getting, according to Milton Hammerly, MD, chief medical officer at QualChoice Health Insurance in Little Rock, Ark.

“After residency, you get very little feedback on your work,” said Dr. Hammerly, who used to work for a hospital system. “Annual reviews for physicians focus almost exclusively on outcomes, productivity, and quality metrics, but not on people skills, what is called ‘emotional intelligence.’ ”

Dr. Hammerly said he saw the consequence of this lack of education when he was vice president for medical affairs at the hospital system. He was constantly dealing with physicians who exhibited serious disruptive behavior and had to be disciplined. “If only they had gotten a little help earlier on,” he noted.

Dr. Hammerly said that 360-degree evaluations, which are common in corporations but rarely used for physicians, could benefit the profession. He discovered the 360-degree evaluation when it was used for him at QualChoice, and he has been a fan ever since.

The approach involves collecting evaluations of you from your boss, your peers, and from people who work for you. That is, from 360 degrees around you. These people are asked to rate your strengths and weaknesses in a variety of competencies. In this way, you get feedback from all of your work relationships, not just from your boss.

Ideally, the evaluators are anonymous, and the subject works with a facilitator to process the information. But 360-degree evaluations can be done in all kinds of ways.

Critics of the 360-degree evaluations say the usual anonymity of evaluators allows them to be too harsh. Also, evaluators may be too subjective: What they say about you says more about their own perspective than anything about you.

But many people think 360-degree evaluations are at least going in the right direction, because they focus on people skills rather than just meeting metrics.

Robert Centor, MD, an internist in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of the performance measures committee of the American College of Physicians, said the best way to improve performance is to have conversations about your work with colleagues on the department level. “For example, 20 doctors could meet to discuss a certain issue, such as the need for more vaccinations. That doesn’t have to get rewarded with a bonus payment.”

Dr. Pearl said that “doctors need feedback from their colleagues. Without feedback, how else do you get better? You can only improve if you can know how you’re performing, compared to others.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians get an annual performance review, and may be either elated, disappointed, or confused with their rating.

But some physicians say the right factors aren’t being evaluated or, in many cases, the performance measures promote efforts that are counterproductive.

“Bonuses are a behaviorist approach,” said Richard Gunderman, MD, professor in the schools of medicine, liberal arts, and philanthropy at Indiana University, Indianapolis. “The presumption is that people will change if they get some money – that they will do what the incentive wants them to do and refrain from what it doesn’t want them to do.”

Dr. Gunderman said this often means just going through the motions to get the bonus, and not sharing goals that only the administration cares about. “The goals might be to lower costs, ensure compliance with regulations or billing requirements, or make patterns of care more uniform. These are not changes that are well tailored to what patients want or how doctors think.”

The bonus is a central feature of the annual review. Merritt Hawkins, the physician search firm, reported that 75% of the physician jobs that it searches for involve some kind of production bonus. Bonuses often make up at least 5% of total compensation, but they can be quite hefty in some specialties.

Having to fulfill measures that they’re not excited about can lead physicians to feel disengaged from their work, Dr. Gunderman said. And this disengagement can contribute to physician burnout, which has climbed to very high rates in recent years.

A 2018 paper by two physician leadership experts explored this problem with bonuses. “A growing consensus [of experts] suggests that quality-incentive pay isn’t paying the dividends first envisioned,” they wrote.

The problem is that the measurements tied to a bonus represent an extrinsic motivation – involving goals that doctors don’t really believe in. Instead, physicians need to be intrinsically motivated. They need to be inspired “to manage their own lives,” “to get better at something,” and “to be a part of a larger cause,” they wrote.

How to develop a better review process

“The best way to motivate improved performance is through purpose and mission,” said Robert Pearl, MD, former CEO of the Permanente Medical Group in California and now a lecturer on strategy at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The review process, Dr. Pearl said, should inspire physicians to do better. The doctors should be asking themselves: “How well did we do in helping maximize the health of all of our patients? And how well did we do in avoiding medical errors, preventing complications, meeting the needs of our patients, and achieving superior quality outcomes?”

When he was CEO of Permanente, the huge physician group that works exclusively for health maintenance organization Kaiser, Dr. Pearl and fellow leaders revamped the review system that all Permanente physicians undergo.

First, the Permanente executives provided all physicians with everyone’s patient-satisfaction data, including their own. That way, each physician could compare performance with others and assess strengths and weaknesses. Then Permanente offered educational programs so that physicians could get help in meeting their goals.

“This approach helped improve quality of care, patient satisfaction, and fulfillment of physicians,” Dr. Pearl said. Kaiser Permanente earned the highest health plan member satisfaction rating by J.D. Power and higher rankings by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Permanente does not base the bonus on relative value units but on performance measures that are carefully balanced to avoid too much focus on certain measures. “There needs to be an array of quality measures because doctors deal with a complex set of problems,” Dr. Pearl said. For example, a primary care physician at Permanente is assessed on about 30 different measures.

Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration. Dr. Pearl said.

Although Permanente physicians are compared with each other, they are not pitted against each other but rather are asked to collaborate. “Physicians are more likely to be successful when you emphasize collaboration,” he said. “They can teach each other. You can be good at some things, and your colleague can be good at others.”

Permanente still has one-on-one yearly evaluations, but much of the assessment work is done in monthly meetings within each department. “There, small groups of doctors look at their data and discuss how each of them can improve,” Dr. Pearl noted.

The 360-degree review is valuable but has some problems

Physicians should be getting a lot more feedback about their behavior than they are actually getting, according to Milton Hammerly, MD, chief medical officer at QualChoice Health Insurance in Little Rock, Ark.

“After residency, you get very little feedback on your work,” said Dr. Hammerly, who used to work for a hospital system. “Annual reviews for physicians focus almost exclusively on outcomes, productivity, and quality metrics, but not on people skills, what is called ‘emotional intelligence.’ ”

Dr. Hammerly said he saw the consequence of this lack of education when he was vice president for medical affairs at the hospital system. He was constantly dealing with physicians who exhibited serious disruptive behavior and had to be disciplined. “If only they had gotten a little help earlier on,” he noted.

Dr. Hammerly said that 360-degree evaluations, which are common in corporations but rarely used for physicians, could benefit the profession. He discovered the 360-degree evaluation when it was used for him at QualChoice, and he has been a fan ever since.

The approach involves collecting evaluations of you from your boss, your peers, and from people who work for you. That is, from 360 degrees around you. These people are asked to rate your strengths and weaknesses in a variety of competencies. In this way, you get feedback from all of your work relationships, not just from your boss.

Ideally, the evaluators are anonymous, and the subject works with a facilitator to process the information. But 360-degree evaluations can be done in all kinds of ways.

Critics of the 360-degree evaluations say the usual anonymity of evaluators allows them to be too harsh. Also, evaluators may be too subjective: What they say about you says more about their own perspective than anything about you.

But many people think 360-degree evaluations are at least going in the right direction, because they focus on people skills rather than just meeting metrics.

Robert Centor, MD, an internist in Birmingham, Ala., and a member of the performance measures committee of the American College of Physicians, said the best way to improve performance is to have conversations about your work with colleagues on the department level. “For example, 20 doctors could meet to discuss a certain issue, such as the need for more vaccinations. That doesn’t have to get rewarded with a bonus payment.”

Dr. Pearl said that “doctors need feedback from their colleagues. Without feedback, how else do you get better? You can only improve if you can know how you’re performing, compared to others.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Lessons learned as a gastroenterologist on social media

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

Study highlights benefits of integrating dermatology into oncology centers

, according to the results of a retrospective study of 208 adults treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, or affiliated sites.

The benefits of prophylactic treatment for treatment-related skin rash in cancer patients are well established, based largely on the Skin Toxicity Evaluation Protocol With Panitumumab (STEPP) trial published in 2012, which led to the development of guidelines for preventing and managing skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFRi) treatment, wrote Zizi Yu of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors. However, they added, “awareness of and adherence to these guidelines among oncology clinicians are thus far poorly understood.” They pointed out that 90% of patients treated with an EGFRi develop cutaneous toxicities, which can affect quality of life, increase the risk of infection, and require dose modification, interruption, or discontinuation of treatment.

In the study, published in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers compared adherence to protocols at Dana-Farber before and after the 2014-2015 initiation of a Skin Toxicities from Anticancer Therapies (STAT) program at Dana-Farber established in 2014 by the department of dermatology.

The study population included 208 adult cancer patients with colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer, or cutaneous squamous cell cancer, treated with at least one dose of cetuximab (Erbitux); the average age of the patients was 62 years and the majority were men. Most had stage IV disease. The STAT program included the integration of 9 oncodermatologists in the head and neck, genitourinary, and cutaneous oncology clinics for 7 of 10 cancer treatment sessions per week, as well as the creation of urgent access time slots in oncodermatology clinics for 10 of 10 sessions per week.

Overall, significantly more patients were treated prophylactically for skin toxicity at the start of cetuximab treatment in 2017 vs. 2012 (47% vs. 25%, P less than .001) after the initiation of a dermatology protocol.

In addition, the preemptive use of tetracycline increased significantly from 45% to 71% (P = .02) between the two time periods, as did the use of topical corticosteroids (from 7% to 57%, P less than .001), while the use of topical antibiotics decreased from 79% to 43% (P = .02). Rates of dose changes or interruptions were significantly lower among those on prophylaxis (5% vs. 19%, P =.01), a 79% lower risk. Patients treated prophylactically were 94% less likely to need a first rescue treatment and 74% less likely to need a second rescue treatment for rash.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, use of data from a single institution, and incomplete documentation of some patients, the researchers noted. However, the results “highlight the value of integrating dermatologic care and education into oncology centers by increasing adherence to evidence-based prophylaxis protocols for rash and appropriate treatment agent selection, which may minimize toxicity-associated chemotherapy interruptions and improve quality of life,” they concluded.

“As novel cancer treatment options for patients continue to develop, and as patients with cancer live longer, the spectrum and prevalence of dermatologic toxic effects will continue to expand,” Bernice Y. Kwong, MD, director of the supportive dermato-oncology program at Stanford (Calif.) University, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Dermatologists have a critical and growing opportunity and role to engage in multidisciplinary efforts to provide expert guidance to best manage these cutaneous adverse events to achieve the best outcome for patients with cancer,” she said.

Although the prophylaxis rates at Dana-Farber improved after the establishment of the oncodermatology program, they remained relatively low, “underscoring an opportunity to improve on how to teach, execute, and improve access to oncodermatologic care for patients with cancer,” said Dr. Kwong. Knowledge gaps in the nature of skin toxicity for newer cancer drugs poses another challenge for skin toxicity management in these patients, she added.

However, “timely and consistent access to dermatologic expertise in oncology practices is critical to prevent unnecessary discontinuation of life-saving anticancer therapy, especially as multiple studies have demonstrated that anticancer therapy–associated skin toxicity may be associated with a positive response to anticancer therapy,” she emphasized.

Ms. Yu and one coauthor had no financial conflicts to disclose, the two other authors had several disclosures, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Kwong disclosed serving as a consultant for Genentech and Oncoderm and serving on the advisory board for Kyowa Kirin.

SOURCE: Yu Z et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 July 1. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1795. Kwong BY. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1794.

, according to the results of a retrospective study of 208 adults treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, or affiliated sites.

The benefits of prophylactic treatment for treatment-related skin rash in cancer patients are well established, based largely on the Skin Toxicity Evaluation Protocol With Panitumumab (STEPP) trial published in 2012, which led to the development of guidelines for preventing and managing skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFRi) treatment, wrote Zizi Yu of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors. However, they added, “awareness of and adherence to these guidelines among oncology clinicians are thus far poorly understood.” They pointed out that 90% of patients treated with an EGFRi develop cutaneous toxicities, which can affect quality of life, increase the risk of infection, and require dose modification, interruption, or discontinuation of treatment.

In the study, published in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers compared adherence to protocols at Dana-Farber before and after the 2014-2015 initiation of a Skin Toxicities from Anticancer Therapies (STAT) program at Dana-Farber established in 2014 by the department of dermatology.

The study population included 208 adult cancer patients with colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer, or cutaneous squamous cell cancer, treated with at least one dose of cetuximab (Erbitux); the average age of the patients was 62 years and the majority were men. Most had stage IV disease. The STAT program included the integration of 9 oncodermatologists in the head and neck, genitourinary, and cutaneous oncology clinics for 7 of 10 cancer treatment sessions per week, as well as the creation of urgent access time slots in oncodermatology clinics for 10 of 10 sessions per week.