User login

For MD-IQ use only

Brain imaging gives new insight into hoarding disorder

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a neuroimaging study, investigators led by Taro Mizobe, department of neuropsychiatry, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, compared brain scans of individuals with and without HD.

Results showed that compared with healthy family members, participants with HD had anatomically widespread abnormalities in WM tracts.

In particular, a broad range of alterations were found in frontal WM related to HD symptom severity, as well as cortical regions involved in cognitive dysfunction.

“The finding of a characteristic association between alterations in the prefrontal WM tract, which connects cortical regions involved in cognitive function and the severity of hoarding symptoms, could provide new insights into the neurobiological basis of HD,” the researchers write.

The findings were published online Jan. 18 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Limited information to date

“Although there are no clear neurobiological models of HD, several neuroimaging studies have found specific differences in specific brain regions” between patients with and without HD, the investigators write.

Structural MRI studies and voxel-based morphometry have shown larger volumes of gray matter in several regions of the brain in patients with HD. However, there have been no reports on alterations in the WM tracts – and studies of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms have yielded only “limited information” regarding WM tracts, the researchers note.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have yielded “inconsistent” findings, “therefore little is known about the microstructure of WM in the brains of patients with HD,” they add.

The current study was designed “to investigate microstructural alterations in the WM tracts of individuals with HD” by using tract-based spatial statistics – a model typically used for whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis of DTI measures.

DTI neuroimaging can assess the microstructure of WM. In the current study, the investigators focused on the three measures yielded by DTI: fractional anisotropy (FA), which is an index of overall WM integrity; axial diffusivity (AD); and radial diffusivity (RD).

Participants underwent MRI and DTI scans. Brain images of 25 individuals with hoarding disorder (mean age, 43 years; 64% women; 96% right-handed) were compared with those of 36 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and handedness.

Participants with HD had higher scores on the Hamilton Rating Scales for depression and anxiety than those without HD (P < .001 for both).

Of the patients with HD, 10 were taking psychiatric medications such as antidepressants, tranquilizers, or nonstimulant agents for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Most (n = 18) were concurrently diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The researchers also conducted a post hoc analysis of regions of interest “to detect correlations with clinical features.”

Microstructural alterations

Compared with healthy controls, patients with hoarding disorder showed decreased FA and increased RD in anatomically widespread WM tracts.

Decreased FA areas included the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), left uncinate fasciculus, left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF), left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), left corticospinal tract, and left anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).

Increased RD areas included the bilateral SLF, right IFOF, bilateral anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior corona radiata, right ATR, left posterior thalamic radiation, right external capsule, and right ALIC.

Post hoc analyses of “regions of interest,” revealed “significant negative correlation” between the severity of hoarding symptoms and FA, particularly in the left anterior limb of the internal capsule, and a positive correlation between HD symptom severity and radial diffusivity in the right anterior thalamic radiation.

Those with HD also showed “a broad range of alterations” in the frontal WM tracts, including the frontothalamic circuit, frontoparietal network, and frontolimbic pathway.

“We found anatomically widespread decreases in FA and increases in WD in many major WM tracts and correlations between the severity of hoarding symptoms and DTI parameters (FA and RD) in the left ALIC and right ATR, which is part of the frontothalamic circuit,” the investigators write.

These findings “suggest that patients with HD have microstructural alterations in the prefrontal WM tracts,” they add.

First study

The researchers say that, to their knowledge, this is the first study to find major abnormalities in WM tracts within the brain and correlations between DTI indexes and clinical features in patients with HD.

The frontothalamic circuit is “thought to play an important role in executive functions, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making,” the investigators write.

Previous research implied that frontothalamic circuit–related cognitive functions are “impaired in patients with HD” and suggested that these impairments “underlie hoarding symptoms such as acquiring, saving, and cluttering relevant to HD.”

The decreased FA in the left SLF “reflects alterations in WM in the frontoparietal network in these patients and may be associated with cognitive impairments, such as task switching and inhibition, as shown in previous studies,” the researchers write.

Additionally, changes in FA and RD often “indicate myelin pathology,” which suggest that HD pathophysiology “may include abnormalities of myelination.”

However, the investigators cite several study limitations, including the “relatively small” sample size, which kept the DTI analysis from being “robust.” Moreover, many patients with HD had comorbid psychiatric disorders, which have also been associated with microstructural abnormalities in WM, the researchers note.

Novel approach

Commenting for this news organization, Michael Stevens, PhD, director, CNDLAB, Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, and adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., said the study “provides useful new clues for understanding HD neurobiology” because of its novel approach in assessing microstructural properties of major WM tracts.

The study’s “main contribution is to identify specific WM pathways between brain regions as worth looking at closely in the future. Some of these regions already have been implicated by brain function neuroimaging as abnormal in patients who compulsively hoard,” said Dr. Stevens, who was not involved in the research.

He noted that, when WM pathway integrity is affected, “it is thought to have an impact on how well information is communicated” between the brain regions.

“So once these specific findings are replicated in a separate study, they hopefully can guide researchers to ask new questions to learn exactly how these WM tracts might contribute to hoarding behavior,” Dr. Stevens said.

The study had no specific funding. The investigators and Dr. Stevens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #14 for the ObGyn

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Endocrine Society and others to FDA: Restrict BPA

The chemical is used to make plastics in items such as food containers, pitchers, and inner linings of metal products. Small amounts of BPA can leak into food and beverages.

The petition points to a December 2021 report by the European Food Safety Authority titled: “Re-evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs,” which summarizes evidence gathered since 2013.

It concludes that “there is a health concern from BPA exposure for all age groups.” Specific concerns include harm to the immune system and male and female reproductive systems.

Average American exposed to 5,000 times the safe level of BPA

The EFSA established a new “tolerable daily intake” of BPA of 0.04 ng/kg of body weight per day. By contrast, in 2014 the FDA estimated that the mean BPA intake for the U.S. population older than 2 years was 200 ng/kg bw/day and that the 90th percentile for BPA intake was 500 ng/kg of body weight per day.

“Using FDA’s own exposure estimates, the average American is exposed to more than 5000 times the safe level of 0.04 ng BPA/kg [body weight per day] set by the EFSA expert panel. Without a doubt, these values constitute a high health risk and support the conclusion that uses of BPA are not safe ... Given the magnitude of the overexposure, we request an expedited review by FDA,” the petition reads.

In addition to the Endocrine Society, which has long warned about the dangers of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, other signatories to the petition include the Environmental Defense Fund, Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, Clean Water Action/Clean Water Fund, Consumer Reports, Environmental Working Group, Healthy Babies Bright Futures, and the former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program.

In a statement, Endocrine Society BPA expert Heather Patisaul, PhD, of North Carolina University, Raleigh, said the report’s findings “are extremely concerning and prove the point that even very low levels of BPA exposure can be harmful and lead to issues with reproductive health, breast cancer risk, behavior, and metabolism.”

“The FDA needs to acknowledge the science behind endocrine-disrupting chemicals and act accordingly to protect public health,” she urged.

The FDA is expected to decide within the next few days whether to open a docket to accept comments.

A final decision could take 6 months or longer, an Endocrine Society spokesperson told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chemical is used to make plastics in items such as food containers, pitchers, and inner linings of metal products. Small amounts of BPA can leak into food and beverages.

The petition points to a December 2021 report by the European Food Safety Authority titled: “Re-evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs,” which summarizes evidence gathered since 2013.

It concludes that “there is a health concern from BPA exposure for all age groups.” Specific concerns include harm to the immune system and male and female reproductive systems.

Average American exposed to 5,000 times the safe level of BPA

The EFSA established a new “tolerable daily intake” of BPA of 0.04 ng/kg of body weight per day. By contrast, in 2014 the FDA estimated that the mean BPA intake for the U.S. population older than 2 years was 200 ng/kg bw/day and that the 90th percentile for BPA intake was 500 ng/kg of body weight per day.

“Using FDA’s own exposure estimates, the average American is exposed to more than 5000 times the safe level of 0.04 ng BPA/kg [body weight per day] set by the EFSA expert panel. Without a doubt, these values constitute a high health risk and support the conclusion that uses of BPA are not safe ... Given the magnitude of the overexposure, we request an expedited review by FDA,” the petition reads.

In addition to the Endocrine Society, which has long warned about the dangers of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, other signatories to the petition include the Environmental Defense Fund, Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, Clean Water Action/Clean Water Fund, Consumer Reports, Environmental Working Group, Healthy Babies Bright Futures, and the former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program.

In a statement, Endocrine Society BPA expert Heather Patisaul, PhD, of North Carolina University, Raleigh, said the report’s findings “are extremely concerning and prove the point that even very low levels of BPA exposure can be harmful and lead to issues with reproductive health, breast cancer risk, behavior, and metabolism.”

“The FDA needs to acknowledge the science behind endocrine-disrupting chemicals and act accordingly to protect public health,” she urged.

The FDA is expected to decide within the next few days whether to open a docket to accept comments.

A final decision could take 6 months or longer, an Endocrine Society spokesperson told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The chemical is used to make plastics in items such as food containers, pitchers, and inner linings of metal products. Small amounts of BPA can leak into food and beverages.

The petition points to a December 2021 report by the European Food Safety Authority titled: “Re-evaluation of the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs,” which summarizes evidence gathered since 2013.

It concludes that “there is a health concern from BPA exposure for all age groups.” Specific concerns include harm to the immune system and male and female reproductive systems.

Average American exposed to 5,000 times the safe level of BPA

The EFSA established a new “tolerable daily intake” of BPA of 0.04 ng/kg of body weight per day. By contrast, in 2014 the FDA estimated that the mean BPA intake for the U.S. population older than 2 years was 200 ng/kg bw/day and that the 90th percentile for BPA intake was 500 ng/kg of body weight per day.

“Using FDA’s own exposure estimates, the average American is exposed to more than 5000 times the safe level of 0.04 ng BPA/kg [body weight per day] set by the EFSA expert panel. Without a doubt, these values constitute a high health risk and support the conclusion that uses of BPA are not safe ... Given the magnitude of the overexposure, we request an expedited review by FDA,” the petition reads.

In addition to the Endocrine Society, which has long warned about the dangers of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, other signatories to the petition include the Environmental Defense Fund, Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, Clean Water Action/Clean Water Fund, Consumer Reports, Environmental Working Group, Healthy Babies Bright Futures, and the former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program.

In a statement, Endocrine Society BPA expert Heather Patisaul, PhD, of North Carolina University, Raleigh, said the report’s findings “are extremely concerning and prove the point that even very low levels of BPA exposure can be harmful and lead to issues with reproductive health, breast cancer risk, behavior, and metabolism.”

“The FDA needs to acknowledge the science behind endocrine-disrupting chemicals and act accordingly to protect public health,” she urged.

The FDA is expected to decide within the next few days whether to open a docket to accept comments.

A final decision could take 6 months or longer, an Endocrine Society spokesperson told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

2022 Update on fertility

In this Update, the authors discuss 2 important areas that impact fertility. First, with in vitro fertilization (IVF), successful implantation that leads to live birth requires a normal embryo and a receptive endometrium. While research using advanced molecular array technology has resulted in a clinical test to identify the optimal window of implantation, recent evidence has questioned its clinical effectiveness. Second, recognizing the importance of endometriosis—a common disease with high burden that causes pain, infertility, and other symptoms—the World Health Organization (WHO) last year published an informative fact sheet that highlights the diagnosis, treatment options, and challenges of this significant disease.

Endometrial receptivity array and the quest for optimal endometrial preparation prior to embryo transfer in IVF

Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

A successful pregnancy requires optimal crosstalk between the embryo and the endometrium. Over the past several decades, research efforts to improve IVF outcomes have been focused mainly on the embryo factor and methods to improve embryo selection, such as extended culture to blastocyst, time-lapse imaging (morphokinetic assessment), and more notably, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). However, the other half of the equation, the endometrium, has not garnered the attention that it deserves. Effort has therefore been renewed to optimize the endometrial factor by better diagnosing and treating various forms of endometrial dysfunction that could lead to infertility in general and lack of success with IVF and euploid embryo transfers in particular.

Historical background on endometrial function

Progesterone has long been recognized as the main effector that transforms the estrogen-primed endometrium into a receptive state that results in successful embryo implantation. Progesterone exposure is required at appropriate levels and duration before the endometrium becomes receptive to the embryo. If implantation does not occur soon after the endometrium has attained receptive status (7–10 days after ovulation), further progesterone exposure results in progression of endometrial changes that no longer permit successful implantation.

As early as the 1950s, “luteal phase deficiency” was defined as due to inadequate progesterone secretion and resulted in a short luteal phase. In the 1970s, histologic “dating” of the endometrium became the gold standard for diagnosing luteal phase defects; this relied on a classic histologic appearance of secretory phase endometrium and its changes throughout the luteal phase. Subsequently, however, results of prospective randomized controlled trials published in 2004 cast significant doubt on the accuracy and reproducibility of these endometrial biopsies and did not show any clinical diagnostic benefit or correlation with pregnancy outcomes.

21st century advances: Endometrial dating 2.0

A decade later, with the advancement of molecular biology tools such as microarray technology, researchers were able to study endometrial gene expression patterns at different stages of the menstrual cycle. They identified different phases of endometrial development with molecular profiles, or “signatures,” for the luteal phase, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, and uterine fibroids.

In 2013, researchers in Spain introduced a diagnostic test called endometrial receptivity array (ERA) with the stated goal of being able to temporally define the receptive endometrium and identify prereceptive as well as postreceptive states.1 In other words, instead of the histologic dating of the endometrium used in the 1970s, it represented “molecular dating” of the endometrium. Although the initial studies were conducted among women who experienced prior unsuccessful embryo transfers (the so-called recurrent implantation failure, or RIF), the test’s scope was subsequently expanded to include any individual planning on a frozen embryo transfer (FET), regardless of any prior attempts. The term personalized embryo transfer (pET) was coined to suggest the ability to define the best time (up to hours) for embryo transfers on an individual basis. Despite lack of independent validation studies, ERA was then widely adopted by many clinicians (and requested by some patients) with the hope of improving IVF outcomes.

However, not unlike many other novel innovations in assisted reproductive technology, ERA regrettably did not withstand the test of time. Three independent studies in 2021, 1 randomized clinical trial and 2 observational cohort studies, did not show any benefit with regard to implantation rates, pregnancy rates, or live birth rates when ERA was performed in the general infertility population.2-4

Continue to: Study results...

Study results

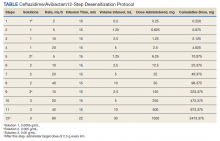

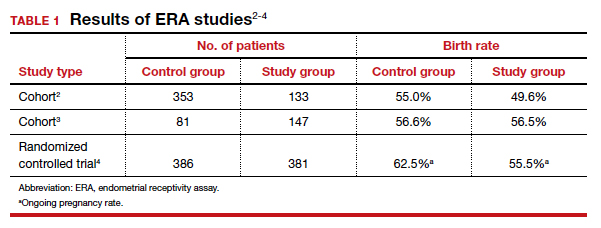

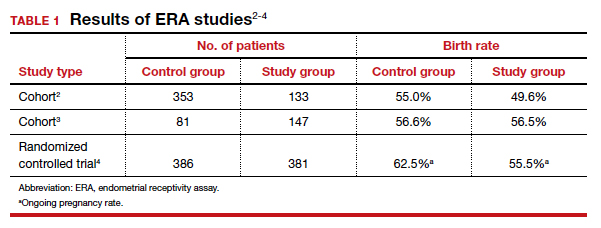

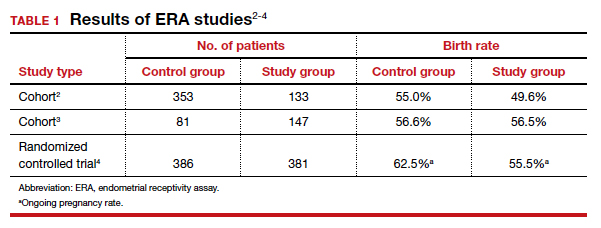

The cohort study that matched 133 ERA patients with 353 non-ERA patients showed live birth rates of 49.62% for the ERA group and 54.96% for the non-ERA group (odds ratio [OR], 0.8074; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5424–1.2018).2 Of note, no difference occurred between subgroups based on the prior number of FETs or the receptivity status (TABLE 1).

Another cohort study from the University of California, Los Angeles, published in 2021 analyzed 228 single euploid FET cycles.3 This study did not show any benefit for routine ERA testing, with a live birth rate of 56.6% in the non-ERA group and 56.5% in the ERA group.

Still, the most convincing evidence for the lack of benefit from routine ERA was noted from the results of the randomized clinical trial.4 A total of 767 patients were randomly allocated, 381 to the ERA group and 386 to the control group. There was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups. Perhaps more important, even after limiting the analysis to individuals with a nonreceptive ERA result, there was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups: 62.5% in the control group (default timing of transfer) and 55.5% in the study group (transfer timing adjusted based on ERA) (rate ratio [RR], 0.9; 95% CI, 0.70–1.14).

ERA usefulness is unsupported in general infertility population

The studies discussed collectively suggest with a high degree of certainty that there is no indication for routine ERA testing in the general infertility population prior to frozen embryo transfers.

Although these studies all were conducted in the general infertility population and did not specifically evaluate the performance of ERA in women with recurrent pregnancy loss or recurrent implantation failure, it is important to acknowledge that if ERA were truly able to define the window of receptivity, one would expect a lower implantation rate if the embryos were transferred outside of the window suggested by the ERA. This was not the case in these studies, as they all showed equivalent pregnancy rates in the control (nonadjusted) groups even when ERA suggested a nonreceptive status.

This observation seriously questions the validity of ERA regarding its ability to temporally define the window of receptivity. On the other hand, as stated earlier, there is still a possibility for ERA to be beneficial for a small subgroup of patients whose window of receptivity may not be as wide as expected in the general population. The challenging question would be how best to identify the particular group with a narrow, or displaced, window of receptivity.

The optimal timing for implantation of a normal embryo requires a receptive endometrium. The endometrial biopsy was used widely for many years before research showed it was not clinically useful. More recently, the endometrial receptivity array has been suggested to help time the frozen embryo transfer. Unfortunately, recent studies have shown that this test is not clinically useful for the general infertility population.

Continue to: WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and...

WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and highlights need to address diagnosis and treatment for women’s reproductive health

World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room /fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

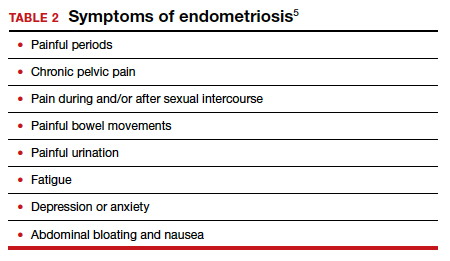

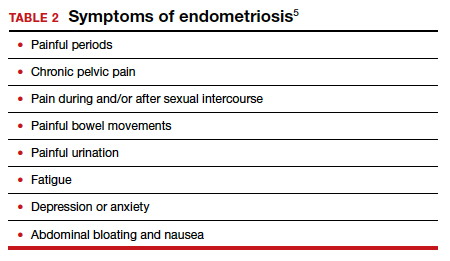

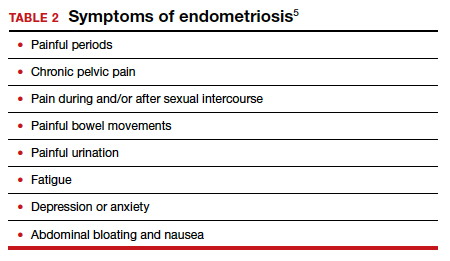

The WHO published its first fact sheet on endometriosis in March 2021, recognizing endometriosis as a severe disease that affects almost 190 million women with life-impacting pain, infertility, other symptoms, and especially with chronic, significant emotional sequelae (TABLE 2).5 The disease’s variable and broad symptoms result in a lack of awareness and diagnosis by both women and health care providers, especially in low- and middle-income countries and in disadvantaged populations in developed countries. Increased awareness to promote earlier diagnosis, improved training for better management, expanded research for greater understanding, and policies that increase access to quality care are needed to ensure the reproductive health and rights of tens of millions of women with endometriosis.

Endometriosis characteristics and symptoms

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of tissue resembling endometrium outside the uterus, where it causes a chronic inflammatory reaction that may result in the formation of scar tissue. Endometriotic lesions may be superficial, cystic ovarian endometriomas, or deep lesions, causing a myriad of pain and related symptoms.6.7

Chronic pain may occur because pain centers in the brain become hyperresponsive over time (central sensitization); this can occur at any point throughout the life course of endometriosis, even when endometriosis lesions are no longer visible. Sometimes, endometriosis is asymptomatic. In addition, endometriosis can cause infertility through anatomic distortion and inflammatory, endocrinologic, and other pathways.

The origins of endometriosis are thought to be multifactorial and include retrograde menstruation, cellular metaplasia, and/or stem cells that spread through blood and lymphatic vessels. Endometriosis is estrogen dependent, but lesion growth also is affected by altered or impaired immunity, localized complex hormonal influences, genetics, and possibly environmental contaminants.

Impact on public health and reproductive rights

Endometriosis has significant social, public health, and economic implications. It can decrease quality of life and prevent girls and women from attending work or school.8 Painful sex can affect sexual health. The WHO states that, “Addressing endometriosis will empower those affected by it, by supporting their human right to the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being.”5

At present, no known way is available to prevent or cure endometriosis. Early diagnosis and treatment, however, may slow or halt its natural progression and associated symptoms.

Diagnostic steps and treatment options

Early suspicion of endometriosis is the most important factor, followed by a careful history of menstrual symptoms and chronic pelvic pain, early referral to specialists for ultrasonography or other imaging, and sometimes surgical or laparoscopic visualization. Empirical treatment can be begun without histologic or laparoscopic confirmation.

Endometriosis can be treated with medications and/or surgery depending on symptoms, lesions, desired outcome, and patient choice.5,6 Common therapies include contraceptive steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and analgesics. Medical treatments focus on either lowering estrogen or increasing progesterone levels.

Surgery can remove endometriosis lesions, adhesions, and scar tissue. However, success in reducing pain symptoms and increasing pregnancy rates often depends on the extent of disease.

For infertility due to endometriosis, treatment options include laparoscopic surgical removal of endometriosis, ovarian stimulation with intrauterine insemination (IUI), and IVF. Multidisciplinary treatment addressing different symptoms and overall health often requires referral to pain experts and other specialists.9

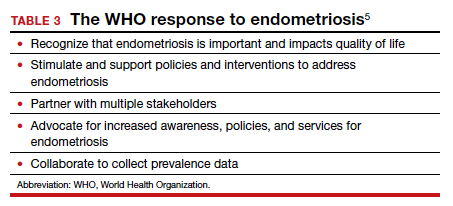

The WHO perspective on endometriosis

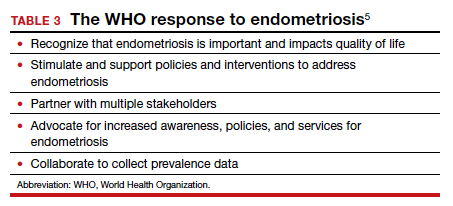

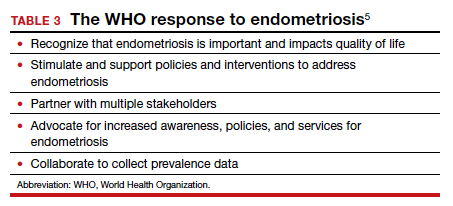

Recognizing the importance of endometriosis and its impact on people’s sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being, the WHO is taking action to improve awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis (TABLE 3).5 ●

Endometriosis is now recognized as a disease with significant burden for women everywhere. Widespread lack of awareness of presenting symptoms and management options means that all women’s health care clinicians need to become better informed about endometriosis so they can improve the quality of care they provide.

- Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Díaz-Gimeno P, et al. The endometrial receptivity array for diagnosis and personalized embryo transfer as a treatment for patients with repeated implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:818-824.

- Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

- Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

- Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail /endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-1256.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:315-324.

- Nnoaham K, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366-373.e8.

- Carey ET, Till SR, As-Sanie S. Pharmacological management of chronic pelvic pain in women. Drugs. 2017;77:285-301.

In this Update, the authors discuss 2 important areas that impact fertility. First, with in vitro fertilization (IVF), successful implantation that leads to live birth requires a normal embryo and a receptive endometrium. While research using advanced molecular array technology has resulted in a clinical test to identify the optimal window of implantation, recent evidence has questioned its clinical effectiveness. Second, recognizing the importance of endometriosis—a common disease with high burden that causes pain, infertility, and other symptoms—the World Health Organization (WHO) last year published an informative fact sheet that highlights the diagnosis, treatment options, and challenges of this significant disease.

Endometrial receptivity array and the quest for optimal endometrial preparation prior to embryo transfer in IVF

Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

A successful pregnancy requires optimal crosstalk between the embryo and the endometrium. Over the past several decades, research efforts to improve IVF outcomes have been focused mainly on the embryo factor and methods to improve embryo selection, such as extended culture to blastocyst, time-lapse imaging (morphokinetic assessment), and more notably, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). However, the other half of the equation, the endometrium, has not garnered the attention that it deserves. Effort has therefore been renewed to optimize the endometrial factor by better diagnosing and treating various forms of endometrial dysfunction that could lead to infertility in general and lack of success with IVF and euploid embryo transfers in particular.

Historical background on endometrial function

Progesterone has long been recognized as the main effector that transforms the estrogen-primed endometrium into a receptive state that results in successful embryo implantation. Progesterone exposure is required at appropriate levels and duration before the endometrium becomes receptive to the embryo. If implantation does not occur soon after the endometrium has attained receptive status (7–10 days after ovulation), further progesterone exposure results in progression of endometrial changes that no longer permit successful implantation.

As early as the 1950s, “luteal phase deficiency” was defined as due to inadequate progesterone secretion and resulted in a short luteal phase. In the 1970s, histologic “dating” of the endometrium became the gold standard for diagnosing luteal phase defects; this relied on a classic histologic appearance of secretory phase endometrium and its changes throughout the luteal phase. Subsequently, however, results of prospective randomized controlled trials published in 2004 cast significant doubt on the accuracy and reproducibility of these endometrial biopsies and did not show any clinical diagnostic benefit or correlation with pregnancy outcomes.

21st century advances: Endometrial dating 2.0

A decade later, with the advancement of molecular biology tools such as microarray technology, researchers were able to study endometrial gene expression patterns at different stages of the menstrual cycle. They identified different phases of endometrial development with molecular profiles, or “signatures,” for the luteal phase, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, and uterine fibroids.

In 2013, researchers in Spain introduced a diagnostic test called endometrial receptivity array (ERA) with the stated goal of being able to temporally define the receptive endometrium and identify prereceptive as well as postreceptive states.1 In other words, instead of the histologic dating of the endometrium used in the 1970s, it represented “molecular dating” of the endometrium. Although the initial studies were conducted among women who experienced prior unsuccessful embryo transfers (the so-called recurrent implantation failure, or RIF), the test’s scope was subsequently expanded to include any individual planning on a frozen embryo transfer (FET), regardless of any prior attempts. The term personalized embryo transfer (pET) was coined to suggest the ability to define the best time (up to hours) for embryo transfers on an individual basis. Despite lack of independent validation studies, ERA was then widely adopted by many clinicians (and requested by some patients) with the hope of improving IVF outcomes.

However, not unlike many other novel innovations in assisted reproductive technology, ERA regrettably did not withstand the test of time. Three independent studies in 2021, 1 randomized clinical trial and 2 observational cohort studies, did not show any benefit with regard to implantation rates, pregnancy rates, or live birth rates when ERA was performed in the general infertility population.2-4

Continue to: Study results...

Study results

The cohort study that matched 133 ERA patients with 353 non-ERA patients showed live birth rates of 49.62% for the ERA group and 54.96% for the non-ERA group (odds ratio [OR], 0.8074; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5424–1.2018).2 Of note, no difference occurred between subgroups based on the prior number of FETs or the receptivity status (TABLE 1).

Another cohort study from the University of California, Los Angeles, published in 2021 analyzed 228 single euploid FET cycles.3 This study did not show any benefit for routine ERA testing, with a live birth rate of 56.6% in the non-ERA group and 56.5% in the ERA group.

Still, the most convincing evidence for the lack of benefit from routine ERA was noted from the results of the randomized clinical trial.4 A total of 767 patients were randomly allocated, 381 to the ERA group and 386 to the control group. There was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups. Perhaps more important, even after limiting the analysis to individuals with a nonreceptive ERA result, there was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups: 62.5% in the control group (default timing of transfer) and 55.5% in the study group (transfer timing adjusted based on ERA) (rate ratio [RR], 0.9; 95% CI, 0.70–1.14).

ERA usefulness is unsupported in general infertility population

The studies discussed collectively suggest with a high degree of certainty that there is no indication for routine ERA testing in the general infertility population prior to frozen embryo transfers.

Although these studies all were conducted in the general infertility population and did not specifically evaluate the performance of ERA in women with recurrent pregnancy loss or recurrent implantation failure, it is important to acknowledge that if ERA were truly able to define the window of receptivity, one would expect a lower implantation rate if the embryos were transferred outside of the window suggested by the ERA. This was not the case in these studies, as they all showed equivalent pregnancy rates in the control (nonadjusted) groups even when ERA suggested a nonreceptive status.

This observation seriously questions the validity of ERA regarding its ability to temporally define the window of receptivity. On the other hand, as stated earlier, there is still a possibility for ERA to be beneficial for a small subgroup of patients whose window of receptivity may not be as wide as expected in the general population. The challenging question would be how best to identify the particular group with a narrow, or displaced, window of receptivity.

The optimal timing for implantation of a normal embryo requires a receptive endometrium. The endometrial biopsy was used widely for many years before research showed it was not clinically useful. More recently, the endometrial receptivity array has been suggested to help time the frozen embryo transfer. Unfortunately, recent studies have shown that this test is not clinically useful for the general infertility population.

Continue to: WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and...

WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and highlights need to address diagnosis and treatment for women’s reproductive health

World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room /fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

The WHO published its first fact sheet on endometriosis in March 2021, recognizing endometriosis as a severe disease that affects almost 190 million women with life-impacting pain, infertility, other symptoms, and especially with chronic, significant emotional sequelae (TABLE 2).5 The disease’s variable and broad symptoms result in a lack of awareness and diagnosis by both women and health care providers, especially in low- and middle-income countries and in disadvantaged populations in developed countries. Increased awareness to promote earlier diagnosis, improved training for better management, expanded research for greater understanding, and policies that increase access to quality care are needed to ensure the reproductive health and rights of tens of millions of women with endometriosis.

Endometriosis characteristics and symptoms

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of tissue resembling endometrium outside the uterus, where it causes a chronic inflammatory reaction that may result in the formation of scar tissue. Endometriotic lesions may be superficial, cystic ovarian endometriomas, or deep lesions, causing a myriad of pain and related symptoms.6.7

Chronic pain may occur because pain centers in the brain become hyperresponsive over time (central sensitization); this can occur at any point throughout the life course of endometriosis, even when endometriosis lesions are no longer visible. Sometimes, endometriosis is asymptomatic. In addition, endometriosis can cause infertility through anatomic distortion and inflammatory, endocrinologic, and other pathways.

The origins of endometriosis are thought to be multifactorial and include retrograde menstruation, cellular metaplasia, and/or stem cells that spread through blood and lymphatic vessels. Endometriosis is estrogen dependent, but lesion growth also is affected by altered or impaired immunity, localized complex hormonal influences, genetics, and possibly environmental contaminants.

Impact on public health and reproductive rights

Endometriosis has significant social, public health, and economic implications. It can decrease quality of life and prevent girls and women from attending work or school.8 Painful sex can affect sexual health. The WHO states that, “Addressing endometriosis will empower those affected by it, by supporting their human right to the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being.”5

At present, no known way is available to prevent or cure endometriosis. Early diagnosis and treatment, however, may slow or halt its natural progression and associated symptoms.

Diagnostic steps and treatment options

Early suspicion of endometriosis is the most important factor, followed by a careful history of menstrual symptoms and chronic pelvic pain, early referral to specialists for ultrasonography or other imaging, and sometimes surgical or laparoscopic visualization. Empirical treatment can be begun without histologic or laparoscopic confirmation.

Endometriosis can be treated with medications and/or surgery depending on symptoms, lesions, desired outcome, and patient choice.5,6 Common therapies include contraceptive steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and analgesics. Medical treatments focus on either lowering estrogen or increasing progesterone levels.

Surgery can remove endometriosis lesions, adhesions, and scar tissue. However, success in reducing pain symptoms and increasing pregnancy rates often depends on the extent of disease.

For infertility due to endometriosis, treatment options include laparoscopic surgical removal of endometriosis, ovarian stimulation with intrauterine insemination (IUI), and IVF. Multidisciplinary treatment addressing different symptoms and overall health often requires referral to pain experts and other specialists.9

The WHO perspective on endometriosis

Recognizing the importance of endometriosis and its impact on people’s sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being, the WHO is taking action to improve awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis (TABLE 3).5 ●

Endometriosis is now recognized as a disease with significant burden for women everywhere. Widespread lack of awareness of presenting symptoms and management options means that all women’s health care clinicians need to become better informed about endometriosis so they can improve the quality of care they provide.

In this Update, the authors discuss 2 important areas that impact fertility. First, with in vitro fertilization (IVF), successful implantation that leads to live birth requires a normal embryo and a receptive endometrium. While research using advanced molecular array technology has resulted in a clinical test to identify the optimal window of implantation, recent evidence has questioned its clinical effectiveness. Second, recognizing the importance of endometriosis—a common disease with high burden that causes pain, infertility, and other symptoms—the World Health Organization (WHO) last year published an informative fact sheet that highlights the diagnosis, treatment options, and challenges of this significant disease.

Endometrial receptivity array and the quest for optimal endometrial preparation prior to embryo transfer in IVF

Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

A successful pregnancy requires optimal crosstalk between the embryo and the endometrium. Over the past several decades, research efforts to improve IVF outcomes have been focused mainly on the embryo factor and methods to improve embryo selection, such as extended culture to blastocyst, time-lapse imaging (morphokinetic assessment), and more notably, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). However, the other half of the equation, the endometrium, has not garnered the attention that it deserves. Effort has therefore been renewed to optimize the endometrial factor by better diagnosing and treating various forms of endometrial dysfunction that could lead to infertility in general and lack of success with IVF and euploid embryo transfers in particular.

Historical background on endometrial function

Progesterone has long been recognized as the main effector that transforms the estrogen-primed endometrium into a receptive state that results in successful embryo implantation. Progesterone exposure is required at appropriate levels and duration before the endometrium becomes receptive to the embryo. If implantation does not occur soon after the endometrium has attained receptive status (7–10 days after ovulation), further progesterone exposure results in progression of endometrial changes that no longer permit successful implantation.

As early as the 1950s, “luteal phase deficiency” was defined as due to inadequate progesterone secretion and resulted in a short luteal phase. In the 1970s, histologic “dating” of the endometrium became the gold standard for diagnosing luteal phase defects; this relied on a classic histologic appearance of secretory phase endometrium and its changes throughout the luteal phase. Subsequently, however, results of prospective randomized controlled trials published in 2004 cast significant doubt on the accuracy and reproducibility of these endometrial biopsies and did not show any clinical diagnostic benefit or correlation with pregnancy outcomes.

21st century advances: Endometrial dating 2.0

A decade later, with the advancement of molecular biology tools such as microarray technology, researchers were able to study endometrial gene expression patterns at different stages of the menstrual cycle. They identified different phases of endometrial development with molecular profiles, or “signatures,” for the luteal phase, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, and uterine fibroids.

In 2013, researchers in Spain introduced a diagnostic test called endometrial receptivity array (ERA) with the stated goal of being able to temporally define the receptive endometrium and identify prereceptive as well as postreceptive states.1 In other words, instead of the histologic dating of the endometrium used in the 1970s, it represented “molecular dating” of the endometrium. Although the initial studies were conducted among women who experienced prior unsuccessful embryo transfers (the so-called recurrent implantation failure, or RIF), the test’s scope was subsequently expanded to include any individual planning on a frozen embryo transfer (FET), regardless of any prior attempts. The term personalized embryo transfer (pET) was coined to suggest the ability to define the best time (up to hours) for embryo transfers on an individual basis. Despite lack of independent validation studies, ERA was then widely adopted by many clinicians (and requested by some patients) with the hope of improving IVF outcomes.

However, not unlike many other novel innovations in assisted reproductive technology, ERA regrettably did not withstand the test of time. Three independent studies in 2021, 1 randomized clinical trial and 2 observational cohort studies, did not show any benefit with regard to implantation rates, pregnancy rates, or live birth rates when ERA was performed in the general infertility population.2-4

Continue to: Study results...

Study results

The cohort study that matched 133 ERA patients with 353 non-ERA patients showed live birth rates of 49.62% for the ERA group and 54.96% for the non-ERA group (odds ratio [OR], 0.8074; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5424–1.2018).2 Of note, no difference occurred between subgroups based on the prior number of FETs or the receptivity status (TABLE 1).

Another cohort study from the University of California, Los Angeles, published in 2021 analyzed 228 single euploid FET cycles.3 This study did not show any benefit for routine ERA testing, with a live birth rate of 56.6% in the non-ERA group and 56.5% in the ERA group.

Still, the most convincing evidence for the lack of benefit from routine ERA was noted from the results of the randomized clinical trial.4 A total of 767 patients were randomly allocated, 381 to the ERA group and 386 to the control group. There was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups. Perhaps more important, even after limiting the analysis to individuals with a nonreceptive ERA result, there was no difference in ongoing pregnancy rates between the 2 groups: 62.5% in the control group (default timing of transfer) and 55.5% in the study group (transfer timing adjusted based on ERA) (rate ratio [RR], 0.9; 95% CI, 0.70–1.14).

ERA usefulness is unsupported in general infertility population

The studies discussed collectively suggest with a high degree of certainty that there is no indication for routine ERA testing in the general infertility population prior to frozen embryo transfers.

Although these studies all were conducted in the general infertility population and did not specifically evaluate the performance of ERA in women with recurrent pregnancy loss or recurrent implantation failure, it is important to acknowledge that if ERA were truly able to define the window of receptivity, one would expect a lower implantation rate if the embryos were transferred outside of the window suggested by the ERA. This was not the case in these studies, as they all showed equivalent pregnancy rates in the control (nonadjusted) groups even when ERA suggested a nonreceptive status.

This observation seriously questions the validity of ERA regarding its ability to temporally define the window of receptivity. On the other hand, as stated earlier, there is still a possibility for ERA to be beneficial for a small subgroup of patients whose window of receptivity may not be as wide as expected in the general population. The challenging question would be how best to identify the particular group with a narrow, or displaced, window of receptivity.

The optimal timing for implantation of a normal embryo requires a receptive endometrium. The endometrial biopsy was used widely for many years before research showed it was not clinically useful. More recently, the endometrial receptivity array has been suggested to help time the frozen embryo transfer. Unfortunately, recent studies have shown that this test is not clinically useful for the general infertility population.

Continue to: WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and...

WHO raises awareness of endometriosis burden and highlights need to address diagnosis and treatment for women’s reproductive health

World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room /fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

The WHO published its first fact sheet on endometriosis in March 2021, recognizing endometriosis as a severe disease that affects almost 190 million women with life-impacting pain, infertility, other symptoms, and especially with chronic, significant emotional sequelae (TABLE 2).5 The disease’s variable and broad symptoms result in a lack of awareness and diagnosis by both women and health care providers, especially in low- and middle-income countries and in disadvantaged populations in developed countries. Increased awareness to promote earlier diagnosis, improved training for better management, expanded research for greater understanding, and policies that increase access to quality care are needed to ensure the reproductive health and rights of tens of millions of women with endometriosis.

Endometriosis characteristics and symptoms

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of tissue resembling endometrium outside the uterus, where it causes a chronic inflammatory reaction that may result in the formation of scar tissue. Endometriotic lesions may be superficial, cystic ovarian endometriomas, or deep lesions, causing a myriad of pain and related symptoms.6.7

Chronic pain may occur because pain centers in the brain become hyperresponsive over time (central sensitization); this can occur at any point throughout the life course of endometriosis, even when endometriosis lesions are no longer visible. Sometimes, endometriosis is asymptomatic. In addition, endometriosis can cause infertility through anatomic distortion and inflammatory, endocrinologic, and other pathways.

The origins of endometriosis are thought to be multifactorial and include retrograde menstruation, cellular metaplasia, and/or stem cells that spread through blood and lymphatic vessels. Endometriosis is estrogen dependent, but lesion growth also is affected by altered or impaired immunity, localized complex hormonal influences, genetics, and possibly environmental contaminants.

Impact on public health and reproductive rights

Endometriosis has significant social, public health, and economic implications. It can decrease quality of life and prevent girls and women from attending work or school.8 Painful sex can affect sexual health. The WHO states that, “Addressing endometriosis will empower those affected by it, by supporting their human right to the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being.”5

At present, no known way is available to prevent or cure endometriosis. Early diagnosis and treatment, however, may slow or halt its natural progression and associated symptoms.

Diagnostic steps and treatment options

Early suspicion of endometriosis is the most important factor, followed by a careful history of menstrual symptoms and chronic pelvic pain, early referral to specialists for ultrasonography or other imaging, and sometimes surgical or laparoscopic visualization. Empirical treatment can be begun without histologic or laparoscopic confirmation.

Endometriosis can be treated with medications and/or surgery depending on symptoms, lesions, desired outcome, and patient choice.5,6 Common therapies include contraceptive steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and analgesics. Medical treatments focus on either lowering estrogen or increasing progesterone levels.

Surgery can remove endometriosis lesions, adhesions, and scar tissue. However, success in reducing pain symptoms and increasing pregnancy rates often depends on the extent of disease.

For infertility due to endometriosis, treatment options include laparoscopic surgical removal of endometriosis, ovarian stimulation with intrauterine insemination (IUI), and IVF. Multidisciplinary treatment addressing different symptoms and overall health often requires referral to pain experts and other specialists.9

The WHO perspective on endometriosis

Recognizing the importance of endometriosis and its impact on people’s sexual and reproductive health, quality of life, and overall well-being, the WHO is taking action to improve awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis (TABLE 3).5 ●

Endometriosis is now recognized as a disease with significant burden for women everywhere. Widespread lack of awareness of presenting symptoms and management options means that all women’s health care clinicians need to become better informed about endometriosis so they can improve the quality of care they provide.

- Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Díaz-Gimeno P, et al. The endometrial receptivity array for diagnosis and personalized embryo transfer as a treatment for patients with repeated implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:818-824.

- Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

- Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

- Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail /endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-1256.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:315-324.

- Nnoaham K, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366-373.e8.

- Carey ET, Till SR, As-Sanie S. Pharmacological management of chronic pelvic pain in women. Drugs. 2017;77:285-301.

- Ruiz-Alonso M, Blesa D, Díaz-Gimeno P, et al. The endometrial receptivity array for diagnosis and personalized embryo transfer as a treatment for patients with repeated implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:818-824.

- Bergin K, Eliner Y, Duvall DW Jr, et al. The use of propensity score matching to assess the benefit of the endometrial receptivity analysis in frozen embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:396-403.

- Riestenberg C, Kroener L, Quinn M, et al. Routine endometrial receptivity array in first embryo transfer cycles does not improve live birth rate. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1001-1006.

- Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing live birth from single euploid frozen blastocyst transfer using standardized timing versus timing by endometrial receptivity analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(suppl):e101.

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis fact sheet. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail /endometriosis. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-1256.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:315-324.

- Nnoaham K, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366-373.e8.

- Carey ET, Till SR, As-Sanie S. Pharmacological management of chronic pelvic pain in women. Drugs. 2017;77:285-301.

3D no-compression breast imaging, new STI treatment resources

Koning 3D Breast CT

Koning expects to submit trial data for their ongoing screening study to the FDA in Q1 2022.

For more information, visit https://www.koninghealth.com/en/

New STI treatment resources

Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set (HEDIS) measures are performance improvement measures used for health plans to track various dimensions of care. In 2019, the HEDIS measure for chlamydia screening showed that commercial and Medicaid health plans had an average 52% screening rate among sexually active 16- to 24-year-old women. In an effort to increase screening rates among young women, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has implemented opt-out, or universal screening, for chlamydia. In order to aid clinicians in implementing this opt-out screening into their practices, the American Sexual Health Association and the National Chlamydia Coalition created resources that offer guidance, including using normalizing language with patients to explain the screening strategy. Providers can access these resources online (http://chlamydiacoalition.org/opt-out-screening/). Videos are offered and include case examples of how to speak with patients about universal screening, and printable documents are included that expand on ways that practices can improve screening rates.

For more information, visit http://chlamydiacoalition.org/opt-out-screening/.

Koning 3D Breast CT

Koning expects to submit trial data for their ongoing screening study to the FDA in Q1 2022.

For more information, visit https://www.koninghealth.com/en/

New STI treatment resources