User login

Clinical Research in Early Career Academic Medicine

Conducting clinical research as an early career gastroenterologist can take on many forms and has varying definitions of success. This article focuses on key factors to consider and should be supplemented with mentorship tailored to personal interests, goals, and institutional criteria for success. In this article, we will discuss selected high-yield topics that assist in early-career research. We will briefly discuss 1. Defining your niche, 2. Collaboration, 3. Visibility, 4. Time management, 5. Funding, 6. Receiving mentorship, and 7. Providing mentorship. We will conclude with discussing several authors’ experience in the research lab of the first author (FELD Lab – Fostering Equity in Liver and Digestive disease).

Defining Your Niche

Defining your niche is an essential component of an early career, as when academicians must transition from a trainee, who is supporting the research of an established mentor, to defining their own subspeciality area of investigation. Early-career academics should build on their prior work, but should also explore their own passions and skill set to define what will be unique about their research program and contributions to the field. Of course, positioning oneself at the intersection of two or more seemingly unrelated fields opens much opportunity for large impact but comes at a cost of identifying mentorship and justifying the niche to funders.

Collaboration

Fostering a collaborative environment is essential for early-career physician-researchers. One effective approach is to establish collaboration circles with other early career academics. Expanding research endeavors beyond a single institution to a multi-center framework enriches both scope and impact. This collaborative approach not only amplifies the depth of research but also facilitates peer mentorship and sponsorship. Participation in such networks can significantly enhance scholarly output and broaden professional reach during this critical phase of academic progression. Furthermore, prioritizing the promotion of colleagues within these networks is crucial. Proactive sponsorship opportunities, such as inviting peers to present at institutional seminars, strengthen both individual and collective academic visibility.

Collaboration is also essential to foster between trainees involved in early-career investigators’ work. An interconnected lab environment ensures that trainees remain informed about concurrent projects, thereby fostering a culture of shared knowledge and optimized productivity. Encouraging trainees to spearhead research aligned with their interests, under mentor guidance, nurtures independent inquiry and leadership. By establishing explicit roles, responsibilities, and authorship agreements at the outset of collaborative projects, early career mentors can avoid future conflicts and preserve a collaborative culture within the lab. This structured approach cultivates a supportive ecosystem, advancing both individual and collective research achievements.

Visibility

Establishing visibility and developing name recognition are crucial components of career advancement for early-career academic physicians. By clearly defining their areas of expertise, faculty can position themselves as leaders within their discipline. Active participation in professional societies, both at the local and national level, engagement with interest groups, and frequent contributions to educational events can be effective strategies for gaining recognition. Leveraging social media platforms can be helpful in enhancing visibility by facilitating connections and promoting research to a broader audience.

Moreover, research visibility plays a vital role in academic promotion. A strong publication record, reflected by an increasing h-index, demonstrates the impact and relevance of one’s research. Self-citation, when appropriate, can reinforce the continuity and progression of scholarly contributions. While publishing in high-impact journals is desirable, adaptability in resubmitting to other journals following rejections ensures that research remains visible and accessible. It also clearly establishes by whom the work was first done, before someone else investigates the line of inquiry. Through a combination of strategic engagement and publication efforts, early-career physicians can effectively build their professional reputation and advance their academic careers.

Time Management

Time management is essential for any research, and particularly in early career when efficiency in clinical care duties is still being gained. Securing protected time for research is essential to develop a niche, build connections (both institutionally and beyond their institutions), and demonstrate productivity that can be utilized to support future grant efforts.

Similarly, using protected time efficiently is required. Without organization and planning, research time can be spent with scattered meetings and responding to various tasks that do not directly support your research. It is helpful to be introspective about the time of the day you are most productive in your research efforts and blocking off that time to focus on research tasks and minimizing distractions. Blocking monthly time for larger scale thinking and planning is also important. Weekly lab and individual one-on-one meetings also support time management for trainees and lab members, to ensure efficiency and progress. Additionally, robust clinical support is essential to ensure that research time remains protected and patient care moves forward. When negotiating for positions, and in regular meetings thereafter, it is important to advocate for sufficient clinical staffing such that non-physician tasks can be appropriately delegated to another member of the care team.

Funding

Securing adequate funding poses a significant challenge for all early-career physician-scientists, particularly because of the discrepancy between National Institutes of Health salary caps and the higher average salaries in academic gastroenterology. This financial gap can deter physicians from pursuing research-intensive careers altogether and can derail early investigators who do not obtain funding rapidly. To overcome this, early-career investigators may need to adopt flexible strategies, such as accepting a lower salary that aligns with grant funding limits or funneling incentive or bonus pay to research accounts. Alternatively, they can advocate for institutional support to bridge the salary gap, ensuring their research efforts remain financially viable.

Institutions committed to fostering research excellence may offer supplemental funding or bridge programs to retain talented physician-scientists, thereby mitigating the financial strain and encouraging long-term engagement in research. Regular meetings to review salary and support sources, including philanthropy, foundation grants, and other streams, should be undertaken with leadership to align the researcher’s timeline and available funding. If career development funding appears untenable, consideration of multi–principal investigator R01s or equivalent with senior established investigators can be a promising path.

Receiving Mentorship

Effective mentorship for early-career physician-scientists should be approached through a team-based model that leverages both internal and external mentors. Internal mentors, familiar with the specific culture, expectations, and advancement pathways of the institution, can provide invaluable guidance on navigating institutional metrics for success, such as promotion criteria, grant acquisition, and clinical-research balance. External mentors, on the other hand, bring a broader perspective by offering innovative career development strategies and solutions derived from experiences at their home institutions. This multimodal mentorship model ensures a well-rounded approach to professional growth.

All national gastroenterology societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, offer structured early-career mentorship programs designed to connect emerging researchers with experienced leaders in the field (see below). These programs typically require a formal application process and are highly regarded for their exceptional quality and impact. Participation in such initiatives can significantly enhance career development by expanding networks, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and providing tailored guidance that complements institutional support. Integrating both internal and external mentorship opportunities ensures a robust and dynamic foundation for long-term success in academic medicine.

- AGA Career Compass (https://gastro.org/fellows-and-early-career/mentoring/)

- ACG Early Career Leadership Program (https://gi.org/acg-institute/early-career-leadership-program/)

- AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (https://gastro.org/news/applications-now-being-accepted-for-the-2024-aga-aasld-academic-skills-workshop/)

- AASLD Women’s Initiative Committee Leadership Program (https://www.aasld.org/promoting-leadership-potential-women-hepatology)

- Scrubs n Heels Mentorship Matrix (https://scrubsandheels.com/matrix/)

Providing Mentorship

The trainee authors on this manuscript describe in this section what has been helpful for them as mentees in the FELD research lab.

Student doctor Nguyen describes her experience as a lab member and things she finds most helpful as a medical student in the lab:

- Upon joining the team, a one-to-one meeting to discuss trainee’s personal and professional goals, and availability, was crucial to building the mentor-mentee relationship. Establishing this meaningful mentorship early on clarified expectations on both sides, built trust, and increased motivation. As a trainee, it is essential for me to see how my work aligns with a long-term goal and to receive ample guidance throughout the process.

- One of the most impactful experiences has been joining informal lunch sessions where trainees discussed data collection protocols and exchanged insights. In doing so, Dr. Feld has cultivated a lab culture that encourages curiosity, constructive feedback, and collaborative learning.

- To increase productivity, our team of trainees created a useful group message thread where we coordinated more sessions to collaborate. This coordination formed stronger relationships between team members and fostered a sense of shared purpose.

Dr. Cooper, a third year internal medicine resident, describes her experience as both a research mentee and a mentor to the junior trainees: “As a resident pursuing a career in academic gastroenterology and hepatology, I have found three key elements to be most helpful: intentional mentorship, structured meetings, and leadership development.”

- Intentional mentorship: Prior to joining the lab, I met with Dr. Feld to discuss my research experience and my goals. She took the time to understand these within the context of my training timeline and tailored project opportunities that aligned with my interests and were both feasible and impactful for my next steps. This intentional approach not only fostered a productive research experience but also established a mentor-mentee relationship built on genuine care for my growth and development.

- Regular meetings: Frequent lab meetings promote accountability, teamwork, and shared problem-solving skills. The open exchange of ideas fosters collaboration and joint problem solving to elevate the quality of our research. They are also an opportunity to observe key decision-making points during the research process and have been a great way to learn more about solid methodology.

- Supervised leadership: I have had ample time to lead discussions and coordinate projects among the junior trainees. These monitored leadership experiences promote project management skills, mentorship, and team dynamic awareness while maintaining the safety net of senior guidance. This model helped me transition from a trainee supporting others’ research to a more independent role, contributing to multi-disciplinary projects while mentoring junior members.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many exciting opportunities and notable barriers exist to establishing a clinical research laboratory in the early career. While excellence in each of the areas outlined may evolve, some aspects will come easier than others and with time, persistence, and a bit of luck, the research world will be a better place because of your contributions!

Dr. Feld is assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology and physician executive of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging for the department of medicine at the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Chan Medical School, Worcester. Ms. Nguyen is a medical student at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Cooper is a resident physician at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Rabinowitz is an attending physician in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass. Dr. Uchida is codirector of the Multidisciplinary Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Clinic at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City.

Conducting clinical research as an early career gastroenterologist can take on many forms and has varying definitions of success. This article focuses on key factors to consider and should be supplemented with mentorship tailored to personal interests, goals, and institutional criteria for success. In this article, we will discuss selected high-yield topics that assist in early-career research. We will briefly discuss 1. Defining your niche, 2. Collaboration, 3. Visibility, 4. Time management, 5. Funding, 6. Receiving mentorship, and 7. Providing mentorship. We will conclude with discussing several authors’ experience in the research lab of the first author (FELD Lab – Fostering Equity in Liver and Digestive disease).

Defining Your Niche

Defining your niche is an essential component of an early career, as when academicians must transition from a trainee, who is supporting the research of an established mentor, to defining their own subspeciality area of investigation. Early-career academics should build on their prior work, but should also explore their own passions and skill set to define what will be unique about their research program and contributions to the field. Of course, positioning oneself at the intersection of two or more seemingly unrelated fields opens much opportunity for large impact but comes at a cost of identifying mentorship and justifying the niche to funders.

Collaboration

Fostering a collaborative environment is essential for early-career physician-researchers. One effective approach is to establish collaboration circles with other early career academics. Expanding research endeavors beyond a single institution to a multi-center framework enriches both scope and impact. This collaborative approach not only amplifies the depth of research but also facilitates peer mentorship and sponsorship. Participation in such networks can significantly enhance scholarly output and broaden professional reach during this critical phase of academic progression. Furthermore, prioritizing the promotion of colleagues within these networks is crucial. Proactive sponsorship opportunities, such as inviting peers to present at institutional seminars, strengthen both individual and collective academic visibility.

Collaboration is also essential to foster between trainees involved in early-career investigators’ work. An interconnected lab environment ensures that trainees remain informed about concurrent projects, thereby fostering a culture of shared knowledge and optimized productivity. Encouraging trainees to spearhead research aligned with their interests, under mentor guidance, nurtures independent inquiry and leadership. By establishing explicit roles, responsibilities, and authorship agreements at the outset of collaborative projects, early career mentors can avoid future conflicts and preserve a collaborative culture within the lab. This structured approach cultivates a supportive ecosystem, advancing both individual and collective research achievements.

Visibility

Establishing visibility and developing name recognition are crucial components of career advancement for early-career academic physicians. By clearly defining their areas of expertise, faculty can position themselves as leaders within their discipline. Active participation in professional societies, both at the local and national level, engagement with interest groups, and frequent contributions to educational events can be effective strategies for gaining recognition. Leveraging social media platforms can be helpful in enhancing visibility by facilitating connections and promoting research to a broader audience.

Moreover, research visibility plays a vital role in academic promotion. A strong publication record, reflected by an increasing h-index, demonstrates the impact and relevance of one’s research. Self-citation, when appropriate, can reinforce the continuity and progression of scholarly contributions. While publishing in high-impact journals is desirable, adaptability in resubmitting to other journals following rejections ensures that research remains visible and accessible. It also clearly establishes by whom the work was first done, before someone else investigates the line of inquiry. Through a combination of strategic engagement and publication efforts, early-career physicians can effectively build their professional reputation and advance their academic careers.

Time Management

Time management is essential for any research, and particularly in early career when efficiency in clinical care duties is still being gained. Securing protected time for research is essential to develop a niche, build connections (both institutionally and beyond their institutions), and demonstrate productivity that can be utilized to support future grant efforts.

Similarly, using protected time efficiently is required. Without organization and planning, research time can be spent with scattered meetings and responding to various tasks that do not directly support your research. It is helpful to be introspective about the time of the day you are most productive in your research efforts and blocking off that time to focus on research tasks and minimizing distractions. Blocking monthly time for larger scale thinking and planning is also important. Weekly lab and individual one-on-one meetings also support time management for trainees and lab members, to ensure efficiency and progress. Additionally, robust clinical support is essential to ensure that research time remains protected and patient care moves forward. When negotiating for positions, and in regular meetings thereafter, it is important to advocate for sufficient clinical staffing such that non-physician tasks can be appropriately delegated to another member of the care team.

Funding

Securing adequate funding poses a significant challenge for all early-career physician-scientists, particularly because of the discrepancy between National Institutes of Health salary caps and the higher average salaries in academic gastroenterology. This financial gap can deter physicians from pursuing research-intensive careers altogether and can derail early investigators who do not obtain funding rapidly. To overcome this, early-career investigators may need to adopt flexible strategies, such as accepting a lower salary that aligns with grant funding limits or funneling incentive or bonus pay to research accounts. Alternatively, they can advocate for institutional support to bridge the salary gap, ensuring their research efforts remain financially viable.

Institutions committed to fostering research excellence may offer supplemental funding or bridge programs to retain talented physician-scientists, thereby mitigating the financial strain and encouraging long-term engagement in research. Regular meetings to review salary and support sources, including philanthropy, foundation grants, and other streams, should be undertaken with leadership to align the researcher’s timeline and available funding. If career development funding appears untenable, consideration of multi–principal investigator R01s or equivalent with senior established investigators can be a promising path.

Receiving Mentorship

Effective mentorship for early-career physician-scientists should be approached through a team-based model that leverages both internal and external mentors. Internal mentors, familiar with the specific culture, expectations, and advancement pathways of the institution, can provide invaluable guidance on navigating institutional metrics for success, such as promotion criteria, grant acquisition, and clinical-research balance. External mentors, on the other hand, bring a broader perspective by offering innovative career development strategies and solutions derived from experiences at their home institutions. This multimodal mentorship model ensures a well-rounded approach to professional growth.

All national gastroenterology societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, offer structured early-career mentorship programs designed to connect emerging researchers with experienced leaders in the field (see below). These programs typically require a formal application process and are highly regarded for their exceptional quality and impact. Participation in such initiatives can significantly enhance career development by expanding networks, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and providing tailored guidance that complements institutional support. Integrating both internal and external mentorship opportunities ensures a robust and dynamic foundation for long-term success in academic medicine.

- AGA Career Compass (https://gastro.org/fellows-and-early-career/mentoring/)

- ACG Early Career Leadership Program (https://gi.org/acg-institute/early-career-leadership-program/)

- AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (https://gastro.org/news/applications-now-being-accepted-for-the-2024-aga-aasld-academic-skills-workshop/)

- AASLD Women’s Initiative Committee Leadership Program (https://www.aasld.org/promoting-leadership-potential-women-hepatology)

- Scrubs n Heels Mentorship Matrix (https://scrubsandheels.com/matrix/)

Providing Mentorship

The trainee authors on this manuscript describe in this section what has been helpful for them as mentees in the FELD research lab.

Student doctor Nguyen describes her experience as a lab member and things she finds most helpful as a medical student in the lab:

- Upon joining the team, a one-to-one meeting to discuss trainee’s personal and professional goals, and availability, was crucial to building the mentor-mentee relationship. Establishing this meaningful mentorship early on clarified expectations on both sides, built trust, and increased motivation. As a trainee, it is essential for me to see how my work aligns with a long-term goal and to receive ample guidance throughout the process.

- One of the most impactful experiences has been joining informal lunch sessions where trainees discussed data collection protocols and exchanged insights. In doing so, Dr. Feld has cultivated a lab culture that encourages curiosity, constructive feedback, and collaborative learning.

- To increase productivity, our team of trainees created a useful group message thread where we coordinated more sessions to collaborate. This coordination formed stronger relationships between team members and fostered a sense of shared purpose.

Dr. Cooper, a third year internal medicine resident, describes her experience as both a research mentee and a mentor to the junior trainees: “As a resident pursuing a career in academic gastroenterology and hepatology, I have found three key elements to be most helpful: intentional mentorship, structured meetings, and leadership development.”

- Intentional mentorship: Prior to joining the lab, I met with Dr. Feld to discuss my research experience and my goals. She took the time to understand these within the context of my training timeline and tailored project opportunities that aligned with my interests and were both feasible and impactful for my next steps. This intentional approach not only fostered a productive research experience but also established a mentor-mentee relationship built on genuine care for my growth and development.

- Regular meetings: Frequent lab meetings promote accountability, teamwork, and shared problem-solving skills. The open exchange of ideas fosters collaboration and joint problem solving to elevate the quality of our research. They are also an opportunity to observe key decision-making points during the research process and have been a great way to learn more about solid methodology.

- Supervised leadership: I have had ample time to lead discussions and coordinate projects among the junior trainees. These monitored leadership experiences promote project management skills, mentorship, and team dynamic awareness while maintaining the safety net of senior guidance. This model helped me transition from a trainee supporting others’ research to a more independent role, contributing to multi-disciplinary projects while mentoring junior members.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many exciting opportunities and notable barriers exist to establishing a clinical research laboratory in the early career. While excellence in each of the areas outlined may evolve, some aspects will come easier than others and with time, persistence, and a bit of luck, the research world will be a better place because of your contributions!

Dr. Feld is assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology and physician executive of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging for the department of medicine at the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Chan Medical School, Worcester. Ms. Nguyen is a medical student at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Cooper is a resident physician at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Rabinowitz is an attending physician in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass. Dr. Uchida is codirector of the Multidisciplinary Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Clinic at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City.

Conducting clinical research as an early career gastroenterologist can take on many forms and has varying definitions of success. This article focuses on key factors to consider and should be supplemented with mentorship tailored to personal interests, goals, and institutional criteria for success. In this article, we will discuss selected high-yield topics that assist in early-career research. We will briefly discuss 1. Defining your niche, 2. Collaboration, 3. Visibility, 4. Time management, 5. Funding, 6. Receiving mentorship, and 7. Providing mentorship. We will conclude with discussing several authors’ experience in the research lab of the first author (FELD Lab – Fostering Equity in Liver and Digestive disease).

Defining Your Niche

Defining your niche is an essential component of an early career, as when academicians must transition from a trainee, who is supporting the research of an established mentor, to defining their own subspeciality area of investigation. Early-career academics should build on their prior work, but should also explore their own passions and skill set to define what will be unique about their research program and contributions to the field. Of course, positioning oneself at the intersection of two or more seemingly unrelated fields opens much opportunity for large impact but comes at a cost of identifying mentorship and justifying the niche to funders.

Collaboration

Fostering a collaborative environment is essential for early-career physician-researchers. One effective approach is to establish collaboration circles with other early career academics. Expanding research endeavors beyond a single institution to a multi-center framework enriches both scope and impact. This collaborative approach not only amplifies the depth of research but also facilitates peer mentorship and sponsorship. Participation in such networks can significantly enhance scholarly output and broaden professional reach during this critical phase of academic progression. Furthermore, prioritizing the promotion of colleagues within these networks is crucial. Proactive sponsorship opportunities, such as inviting peers to present at institutional seminars, strengthen both individual and collective academic visibility.

Collaboration is also essential to foster between trainees involved in early-career investigators’ work. An interconnected lab environment ensures that trainees remain informed about concurrent projects, thereby fostering a culture of shared knowledge and optimized productivity. Encouraging trainees to spearhead research aligned with their interests, under mentor guidance, nurtures independent inquiry and leadership. By establishing explicit roles, responsibilities, and authorship agreements at the outset of collaborative projects, early career mentors can avoid future conflicts and preserve a collaborative culture within the lab. This structured approach cultivates a supportive ecosystem, advancing both individual and collective research achievements.

Visibility

Establishing visibility and developing name recognition are crucial components of career advancement for early-career academic physicians. By clearly defining their areas of expertise, faculty can position themselves as leaders within their discipline. Active participation in professional societies, both at the local and national level, engagement with interest groups, and frequent contributions to educational events can be effective strategies for gaining recognition. Leveraging social media platforms can be helpful in enhancing visibility by facilitating connections and promoting research to a broader audience.

Moreover, research visibility plays a vital role in academic promotion. A strong publication record, reflected by an increasing h-index, demonstrates the impact and relevance of one’s research. Self-citation, when appropriate, can reinforce the continuity and progression of scholarly contributions. While publishing in high-impact journals is desirable, adaptability in resubmitting to other journals following rejections ensures that research remains visible and accessible. It also clearly establishes by whom the work was first done, before someone else investigates the line of inquiry. Through a combination of strategic engagement and publication efforts, early-career physicians can effectively build their professional reputation and advance their academic careers.

Time Management

Time management is essential for any research, and particularly in early career when efficiency in clinical care duties is still being gained. Securing protected time for research is essential to develop a niche, build connections (both institutionally and beyond their institutions), and demonstrate productivity that can be utilized to support future grant efforts.

Similarly, using protected time efficiently is required. Without organization and planning, research time can be spent with scattered meetings and responding to various tasks that do not directly support your research. It is helpful to be introspective about the time of the day you are most productive in your research efforts and blocking off that time to focus on research tasks and minimizing distractions. Blocking monthly time for larger scale thinking and planning is also important. Weekly lab and individual one-on-one meetings also support time management for trainees and lab members, to ensure efficiency and progress. Additionally, robust clinical support is essential to ensure that research time remains protected and patient care moves forward. When negotiating for positions, and in regular meetings thereafter, it is important to advocate for sufficient clinical staffing such that non-physician tasks can be appropriately delegated to another member of the care team.

Funding

Securing adequate funding poses a significant challenge for all early-career physician-scientists, particularly because of the discrepancy between National Institutes of Health salary caps and the higher average salaries in academic gastroenterology. This financial gap can deter physicians from pursuing research-intensive careers altogether and can derail early investigators who do not obtain funding rapidly. To overcome this, early-career investigators may need to adopt flexible strategies, such as accepting a lower salary that aligns with grant funding limits or funneling incentive or bonus pay to research accounts. Alternatively, they can advocate for institutional support to bridge the salary gap, ensuring their research efforts remain financially viable.

Institutions committed to fostering research excellence may offer supplemental funding or bridge programs to retain talented physician-scientists, thereby mitigating the financial strain and encouraging long-term engagement in research. Regular meetings to review salary and support sources, including philanthropy, foundation grants, and other streams, should be undertaken with leadership to align the researcher’s timeline and available funding. If career development funding appears untenable, consideration of multi–principal investigator R01s or equivalent with senior established investigators can be a promising path.

Receiving Mentorship

Effective mentorship for early-career physician-scientists should be approached through a team-based model that leverages both internal and external mentors. Internal mentors, familiar with the specific culture, expectations, and advancement pathways of the institution, can provide invaluable guidance on navigating institutional metrics for success, such as promotion criteria, grant acquisition, and clinical-research balance. External mentors, on the other hand, bring a broader perspective by offering innovative career development strategies and solutions derived from experiences at their home institutions. This multimodal mentorship model ensures a well-rounded approach to professional growth.

All national gastroenterology societies, including the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, offer structured early-career mentorship programs designed to connect emerging researchers with experienced leaders in the field (see below). These programs typically require a formal application process and are highly regarded for their exceptional quality and impact. Participation in such initiatives can significantly enhance career development by expanding networks, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and providing tailored guidance that complements institutional support. Integrating both internal and external mentorship opportunities ensures a robust and dynamic foundation for long-term success in academic medicine.

- AGA Career Compass (https://gastro.org/fellows-and-early-career/mentoring/)

- ACG Early Career Leadership Program (https://gi.org/acg-institute/early-career-leadership-program/)

- AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (https://gastro.org/news/applications-now-being-accepted-for-the-2024-aga-aasld-academic-skills-workshop/)

- AASLD Women’s Initiative Committee Leadership Program (https://www.aasld.org/promoting-leadership-potential-women-hepatology)

- Scrubs n Heels Mentorship Matrix (https://scrubsandheels.com/matrix/)

Providing Mentorship

The trainee authors on this manuscript describe in this section what has been helpful for them as mentees in the FELD research lab.

Student doctor Nguyen describes her experience as a lab member and things she finds most helpful as a medical student in the lab:

- Upon joining the team, a one-to-one meeting to discuss trainee’s personal and professional goals, and availability, was crucial to building the mentor-mentee relationship. Establishing this meaningful mentorship early on clarified expectations on both sides, built trust, and increased motivation. As a trainee, it is essential for me to see how my work aligns with a long-term goal and to receive ample guidance throughout the process.

- One of the most impactful experiences has been joining informal lunch sessions where trainees discussed data collection protocols and exchanged insights. In doing so, Dr. Feld has cultivated a lab culture that encourages curiosity, constructive feedback, and collaborative learning.

- To increase productivity, our team of trainees created a useful group message thread where we coordinated more sessions to collaborate. This coordination formed stronger relationships between team members and fostered a sense of shared purpose.

Dr. Cooper, a third year internal medicine resident, describes her experience as both a research mentee and a mentor to the junior trainees: “As a resident pursuing a career in academic gastroenterology and hepatology, I have found three key elements to be most helpful: intentional mentorship, structured meetings, and leadership development.”

- Intentional mentorship: Prior to joining the lab, I met with Dr. Feld to discuss my research experience and my goals. She took the time to understand these within the context of my training timeline and tailored project opportunities that aligned with my interests and were both feasible and impactful for my next steps. This intentional approach not only fostered a productive research experience but also established a mentor-mentee relationship built on genuine care for my growth and development.

- Regular meetings: Frequent lab meetings promote accountability, teamwork, and shared problem-solving skills. The open exchange of ideas fosters collaboration and joint problem solving to elevate the quality of our research. They are also an opportunity to observe key decision-making points during the research process and have been a great way to learn more about solid methodology.

- Supervised leadership: I have had ample time to lead discussions and coordinate projects among the junior trainees. These monitored leadership experiences promote project management skills, mentorship, and team dynamic awareness while maintaining the safety net of senior guidance. This model helped me transition from a trainee supporting others’ research to a more independent role, contributing to multi-disciplinary projects while mentoring junior members.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many exciting opportunities and notable barriers exist to establishing a clinical research laboratory in the early career. While excellence in each of the areas outlined may evolve, some aspects will come easier than others and with time, persistence, and a bit of luck, the research world will be a better place because of your contributions!

Dr. Feld is assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology and physician executive of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging for the department of medicine at the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Chan Medical School, Worcester. Ms. Nguyen is a medical student at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Cooper is a resident physician at UMass Chan Medical School. Dr. Rabinowitz is an attending physician in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Mass. Dr. Uchida is codirector of the Multidisciplinary Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Clinic at the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City.

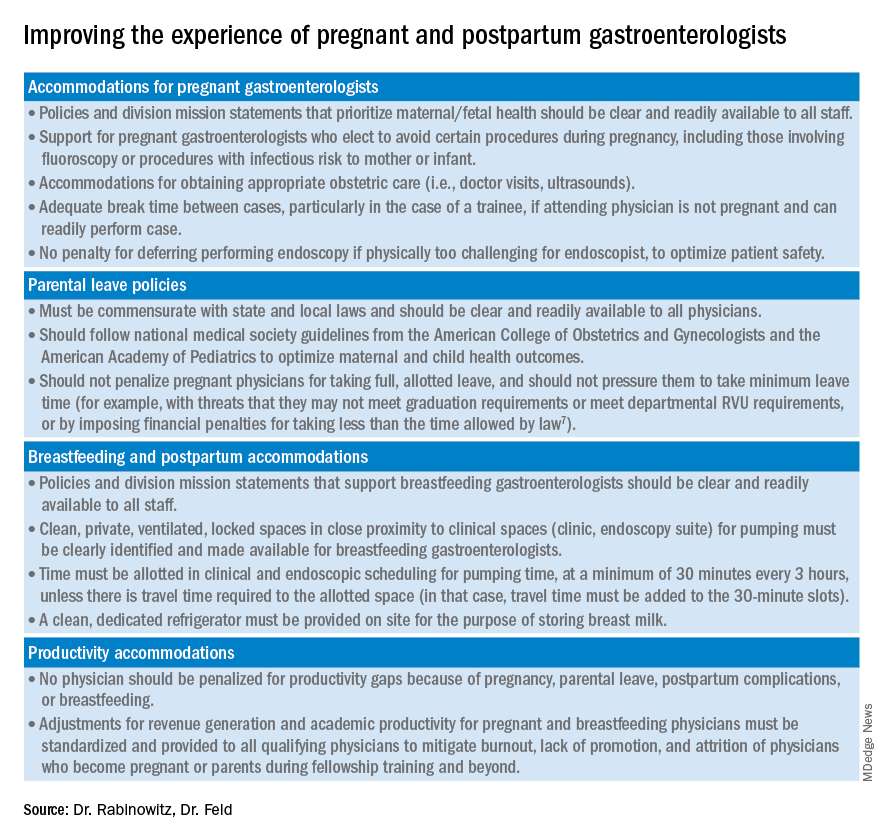

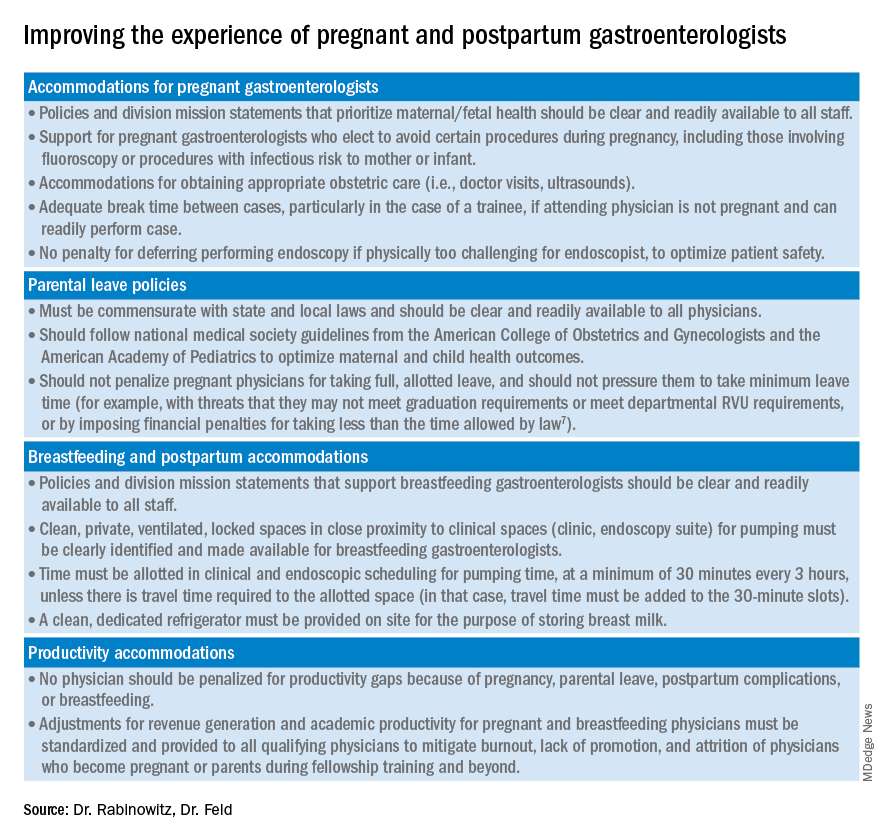

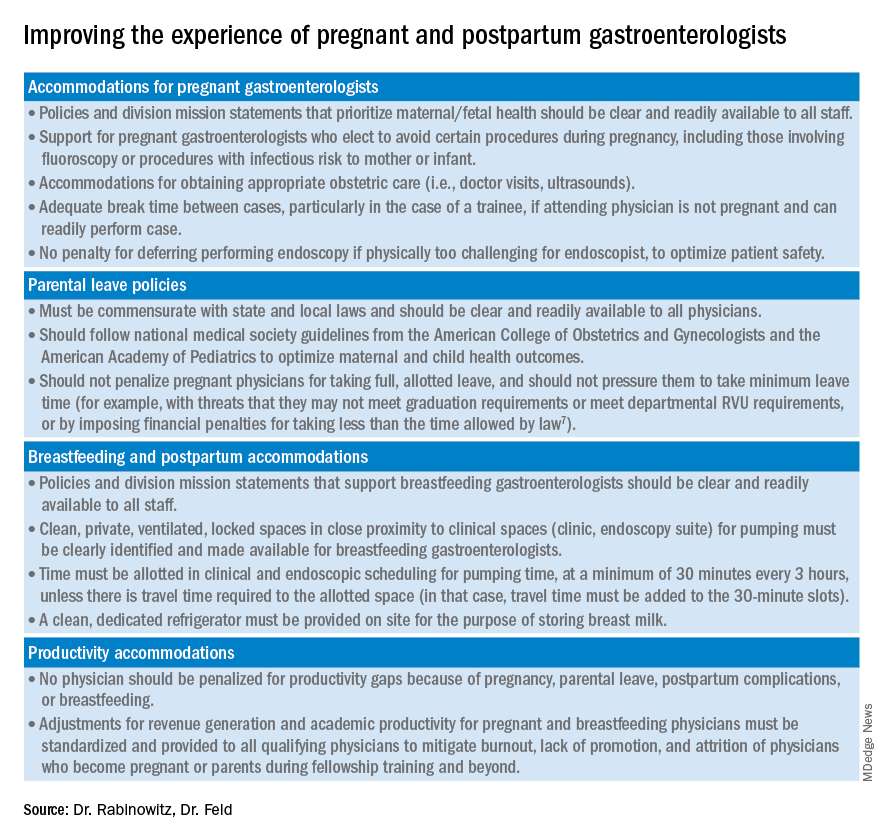

Progress still needed for pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.