User login

A new model of care to return holism to family medicine

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

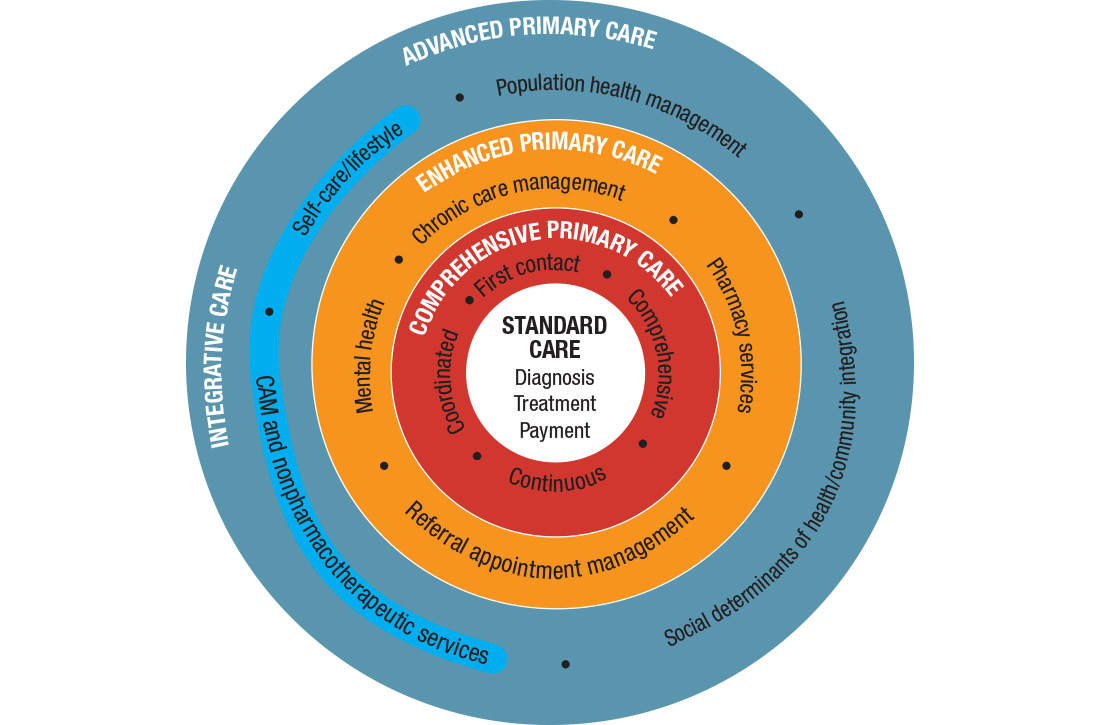

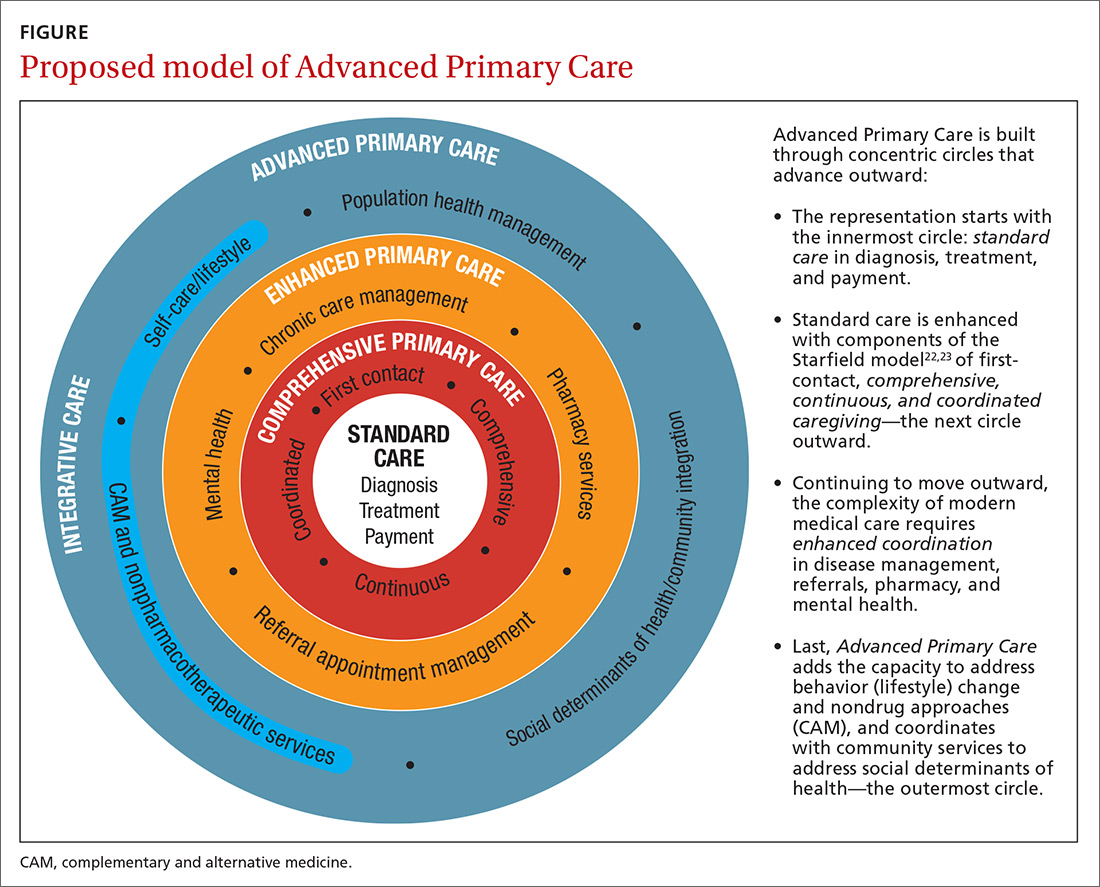

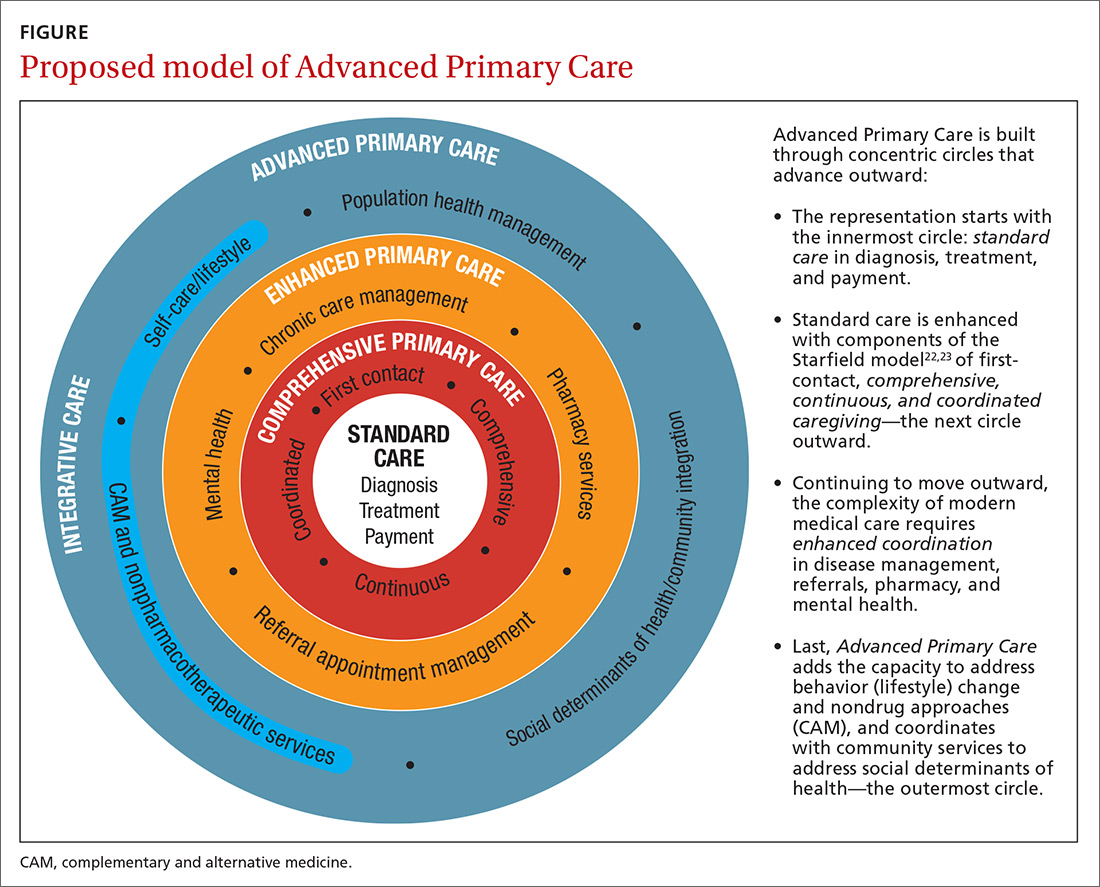

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; [email protected].

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; [email protected].

Here is our problem: Family medicine has allowed itself, and its patients, to be picked apart by the forces of reductionism and a system that profits from the sick and suffering. We have lost sight of our purpose and our vision to care for the whole person. We have lost our way as healers.

The result is not only a decline in the specialty of family medicine as a leader in primary care but declining value and worsening outcomes in health care overall. We need to get our mojo back. We can do this by focusing less on trying to be all things to all people at all times, and more on creating better models for preventing, managing, and reversing chronic disease. This means providing health care that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

I call this model Advanced Primary Care, or APC (FIGURE). In this article, I describe exemplars of APC from across the United States. I also provide tools to help you recover its central feature, holism—care of the whole person in mind, body, community, and spirit—in your practice, thus returning us to the core purpose of family medicine.

Holism is central to family medicine

More than 40 years ago, psychiatrist George Engel, MD, published a seminal article in Science that inspired a radical vision of how health care should be practiced.1 Called the biopsychosocial model, it stated what, in some ways, is obvious: Human beings are complex organisms embedded in complex environments made up of distinct, yet interacting, dimensions. These dimensions included physical, psychological, and social components. Engel’s radical proposition was that these dimensions are definable and measurable and that good medicine cannot afford to ignore any of them.

Engel’s assertion that good medicine requires holism was a clarion call during a time of rapidly expanding knowledge and subspecialization. That call was the inspiration for a new medical specialty called family medicine, which dared to proclaim that the best way to heal was to care for the whole person within the context of that person’s emotional and social environment. Family medicine reinvigorated primary care and grew rapidly, becoming a preeminent primary care specialty in the United States.

Continue to : Reductionism is relentless

Reductionism is relentless

But the forces of medicine were—and still are—driving relentlessly the other way. The science of the small and particular (reductionism), with dazzling technology and exploding subspecialty knowledge, and backed by powerful economic drivers, rewards health care for pulling the patient and the medical profession apart. We pay more to those who treat small parts of a person over a short period than to those who attend to the whole person over the lifetime.

Today, family medicine—for all of its common sense, scientific soundness, connectedness to patients, and demonstrated value—struggles to survive.2-6 The holistic vision of Engel is declining. The struggle in primary care is that its holistic vision gets co-opted by specialized medical science—and then it desperately attempts to apply those small and specialized tools to the care of patients in their wholeness. Holism is largely dead in health care, and everyone pays the consequences.7

Health care is losing its value

The damage from this decline in holism is not just to primary care but to the value of health care in general. Most medical care being delivered today—comprising diagnosis, treatment, and payment (the innermost circle of the FIGURE)—is not producing good health.8 Only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care.9 The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life, including those related to food, movement, sleep, stress, and substance use.10 Increasingly, it is the economic and social determinants of health that influence this behavior and have a greater impact on health and lifespan than physiology or genes.11 The same social determinants of health also influence patients’ ability to obtain medical care and pursue a meaningful life.12

The result of this decline in holism and in the value of health care in general has been a relentless rise in the cost of medical care13-15 and the need for social services; declining life expectancy16,17 and quality of life18; growing patient dissatisfaction; and burnout in providers.19,20 Health care has become, as investor and business leader Warren Buffet remarked, the “tapeworm” of the economy and a major contributor to growing disparities in health and well-being between the haves and have-nots.21 Engel’s prediction that good medicine cannot afford to ignore holism has come to pass.

3-step solution:Return to whole-person care

Family medicine needs to return to whole-person care, but it can do so only if it attends to, and effectively delivers on, the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease and the enhancement of health and well-being. This can happen only if family medicine stops trying to be all things to all people at all times and, instead, focuses on what matters to the patient as a person.

Continue to: This means that the core...

This means that the core interaction in family medicine must be to assess the whole person—mind, body, social, spirit—and help that person make changes that improve his/her/their health and well-being based on his/her/their individualized needs and social context. In other words, family medicine needs to deliver a holistic model of APC that is person centered, relationship based, recovery focused, and paid for comprehensively.

How does one get from “standard” primary care of today (the innermost circle of the FIGURE) to a framework that truly delivers on the promise of healing? I propose 3 steps to return holism to family medicine.

STEP 1: Start with comprehensive, coordinated primary care. We know that this works. Starfield and others demonstrated this 2 decades ago, defining and devising what we know as quality primary care—characterized by first-contact care, comprehensive primary care (CPC), continuous care, and coordinated care.22 This type of primary care improves outcomes, lowers costs, and is satisfying to patients and providers.23 The physician cares for the patient throughout that person’s entire life cycle and provides all evidence-based services needed to prevent and treat common conditions. Comprehensive primary care is positioned in the first circle outward from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

As medicine has become increasingly complex and subspecialized, however, the ability to coordinate care is often frayed, adding cost and reducing quality.24-26 Today, comprehensive primary care needs enhanced coordination. At a minimum, this means coordinating services for:

- chronic disease management (outpatient and inpatient transitions and emergency department use)

- referral (specialists and tests)

- pharmacy services (including delivery and patient education support).

An example of a primary care system that meets these requirements is the Catalyst Health Network in central Texas, which supplies coordination services to more than 1000 comprehensive primary care practices and 1.5 million patients.27 The Catalyst Network makes money for those practices, saves money in the system, enhances patient and provider satisfaction, and improves population health in the community.27 I call this enhanced primary care (EPC), shown in the second circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

STEP 2: Add integrative medicine and mental health. EPC improves fragmented care but does not necessarily address a patient’s underlying determinants of healing. We know that health behaviors such as smoking cessation, avoidance of alcohol and drug abuse, improved diet, physical activity, sleep, and stress management contribute 40% to 60% of a person’s and a population’s health.10 In addition, evidence shows that behavioral health services, along with lifestyle change support, can even reverse many chronic diseases seen in primary care, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, depression, and substance abuse.28,29

Continue to: Therefore, we need to add...

Therefore, we need to add routine mental health services and nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches (eg, complementary and alternative medicine) to primary care.30 Doing so requires that behavioral change and self-care become a central feature of the doctor–patient dialogue and team skills31 and be added to primary care.30,31 I call this integrative primary care (IPC), shown on the left side in the third circle out from the innermost circle of the FIGURE.

An example of IPC is Whole Health, an initiative of the US Veteran’s Health Administration. Whole Health empowers and informs a person-centered approach and integrates it into the delivery of routine care.32 Evaluation of Whole Health implementation, which involved more than 130,000 veterans followed for 2 years, found a net overall reduction in the total cost of care of 20%—saving nearly $650 million or, on average, more than $4500 per veteran.33

STEP 3: Address social determinants of health. Primary care will not fully be part of the solution for producing health and well-being unless it becomes instrumental in addressing the social determinants of health (SDH), defined as “… conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”34 These determinants include not only basic needs, such as housing, food, safety, and transportation (ie, social needs), but also what are known as structural determinants, such as income, education, language, and racial and ethnic bias. Health care cannot solve all of these social ills,but it is increasingly being called on to be the nexus of coordination for services that address these needs when they affect health outcomes.35,36

Examples of health systems that provide for social needs include the free “food prescription” program of Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System, for patients with diabetes who do not have the resources to pay for food.37 This approach improves blood glucose control by patients and saves money on medications and other interventions. Similarly, Kaiser Permanente has experimented with housing vouchers for homeless patients,and most Federally Qualified Health Centers provide bus or other transportation tickets to patients for their appointments and free or discounted tests and specialty care.38

Implementing whole-person care for all

I propose that we make APC the central focus of family medicine. This model would comprise CPC, plus EPC, IPC, and community coordination to address SDH. This is expressed as:

CPC + EPC + IPC + SDH = APC

Continue to: APC would mean...

APC would mean health for the whole person and for all people. Again, the FIGURE shows how this model, encompassing the entire third circle out from the center circle, could be created from current models of care.

How do we pay for this? We already do—and way too much. The problem is not lack of money in the health care system but how it is organized and distributed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are developing value-based payment models to help cover this type of care,39 but payers cannot pay for something if it is unavailable.

Can family physicians deliver APC? I believe they can, and have given a few examples here to show how this is already happening. To help primary care providers start to deliver APC in their system, my team and I have built the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note Toolkit to use in daily practice.40 These and other tools are being used by a number of large hospital systems and health care networks around the country. (You can download the HOPE Note Toolkit, at no cost, at https://drwaynejonas.com/resources/hope-note/.)

Whatever we call this new type of primary care, it needs to care for the whole person and to be available to all. It finds expression in these assertions:

- We cannot ignore an essential part of what a human being is and expect them to heal or become whole.

- We cannot ignore essential people in our communities and expect our costs to go down or our compassion to go up.

- We need to stop allowing family medicine to be co-opted by reductionism and its profits.

In sum, we need a new vision of primary care—like Engel’s holistic vision in the 1970s—to motivate us, and we need to return to fundamental concepts of how healing works in medicine.41

CORRESPONDENCE

Wayne B. Jonas, MD, Samueli Integrative Health Programs, 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 617, Alexandria, VA 22314; [email protected].

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2. Schwartz MD, Durning S, Linzer M, et al. Changes in medical students’ views of internal medicine careers from 1990 to 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:744-749.

3. Bronchetti ET, Christensen GS, Hoynes HW. Local food prices, SNAP purchasing power, and child health. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2018. www.nber.org/papers/w24762?mc_cid=8c7211d34b&mc_eid=fbbc7df813. Accessed November 24, 2020.

4. Federal Student Aid, US Department of Education. Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). 2018. https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/repay-loans/forgiveness-cancellation/public-service. Accessed November 24, 2020.

5. Aten B, Figueroa E, Martin T. Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005-2009. WP2011-03. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; April 2011. www.bea.gov/system/files/papers/WP2011-3.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

6. Aten BH, Figueroa EB, Martin TM. Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce; August 2012. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/08%20August/0812_regional_price_parities.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

7. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293-299.

8. Panel on Understanding Cross-national Health Differences Among High-income Countries, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. The National Academies Press; 2013.

9. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, et al. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:129-135.

10. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

11. Roeder A. Zip code better predictor of health than genetic code. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Web site. News release. August 4, 2014. www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/features/zip-code-better-predictor-of-health-than-genetic-code/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

12. US health map. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; March 13, 2018. www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/us-health-map. Accessed November 24, 2020.

13. Highfill T. Comparing estimates of U.S. health care expenditures by medical condition, 2000-2012. Survey of Current Business. 2016;1-5. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/3%20March/0316_comparing_u.s._health_care_expenditures_by_medical_condition.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

14. Waters H, Graf M. The Costs of Chronic Disease in the US. Washington, DC: Milken Institute; August 2018. https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/reports-pdf/ChronicDiseases-HighRes-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

15. Meyer H. Health care spending will hit 19.4% of GDP in the next decade, CMS projects. Modern Health care. February 20, 2019. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190220/NEWS/190229989/healthcare-spending-will-hit-19-4-of-gdp-in-the-next-decade-cms-projects. Accessed November 24, 2020.

16. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322:1996-2016.

17. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506-514.

18. Zack MM, Moriarty DG, Stroup DF, et al. Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:493-505.

19. Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer, MB, et al. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. Research letter. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:856-858.

20. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529.

21. Buffett: Health care is a tapeworm on the economic system. CNBC Squawk Box. February 26, 2018. www.cnbc.com/video/2018/02/26/buffett-health-care-is-a-tapeworm-on-the-economic-system.html. Accessed November 24, 2020.

22. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992.

23. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

24. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US); 2001.

25. Burton R. Health policy brief: improving care transitions. Health Affairs. September 13, 2012. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120913.327236/full/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

26. Toulany A, Stukel TA, Kurdyak P, et al. Association of primary care continuity with outcomes following transition to adult care for adolescents with severe mental illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198415.

27. Helping communities thrive. Catalyst Health Network Web site. www.catalysthealthnetwork.com/. Accessed November 24, 2020.

28. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171.

29. Scherger JE. Lean and Fit: A Doctor’s Journey to Healthy Nutrition and Greater Wellness. 2nd ed. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing; 2016.

30. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al; . Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:514-530.

31. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207-214.

32. What is whole health? Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs. October 13, 2020. www.va.gov/patientcenteredcare/explore/about-whole-health.asp. Accessed November 25, 2020.

33. COVER Commission. Creating options for veterans’ expedited recovery. Final report. Washington, DC: US Veterans Administration. January 24, 2020. www.va.gov/COVER/docs/COVER-Commission-Final-Report-2020-01-24.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

34. Social determinants of health. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. HealthyPeople.gov Web site. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 24, 2020.

35. Breslin E, Lambertino A. Medicaid and social determinants of health: adjusting payment and measuring health outcomes. Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, State Health and Value Strategies Program Web site. July 2017. www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/SHVS_SocialDeterminants_HMA_July2017.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

36. James CV. Actively addressing social determinants of health will help us achieve health equity. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. April 26, 2019. www.cms.gov/blog/actively-addressing-social-determinants-health-will-help-us-achieve-health-equity. Accessed November 24, 2020.

37. Geisinger receives “Innovation in Advancing Health Equity” award. Geisinger Health Web site. April 24, 2018. www.geisinger.org/health-plan/news-releases/2018/04/23/19/28/geisinger-receives-innovation-in-advancing-health-equity-award. Accessed November 24, 2020.

38. Bresnick J. Kaiser Permanente launches full-network social determinants program. HealthITAnalytics Web site. May 6, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/kaiser-permanente-launches-full-network-social-determinants-program. Accessed November 25, 2020.

39. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC). Physician and other health Professional services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. March 2016: 115-117. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-4-physician-and-other-health-professional-services-march-2016-report-.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

40. Jonas W. Helping patients with chronic diseases and conditions heal with the HOPE Note: integrative primary care case study. https://drwaynejonas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CS_HOPE-Note_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

41. Jonas W. How Healing Works. Berkley, CA: Lorena Jones Books; 2018.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

❯ Build care teams into your practice so that you integrate “what matters” into the center of the clinical encounter. C

❯ Add practice approaches that help patients engage in healthy lifestyles and that remove social and economic barriers for improving health and well-being. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Home visits: A practical approach

CASE

Mr. A is a 30-year-old man with neurofibromatosis and myelopathy with associated quadriplegia, complicated by dysphasia and chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring a tracheostomy. He is cared for at home by his very competent mother but requires regular visits with his medical providers for assistance with his complex care needs. Due to logistical challenges, he had been receiving regular home visits even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

After estimating the risk of exposure to the patient, Mr. A’s family and his physician’s office staff scheduled a home visit. Before the appointment, the doctor conducted a virtual visit with the patient and family members to screen for COVID-19 infection, which proved negative. The doctor arranged a visit to coincide with Mr. A’s regular appointment with the home health nurse. He invited the patient’s social worker to attend, as well.

The providers donned masks, face shields, and gloves before entering the home. Mr. A’s temperature was checked and was normal. The team completed a physical exam, assessed the patient’s current needs, and refilled prescriptions. The doctor, nurse, and social worker met afterward in the family’s driveway to coordinate plans for the patient’s future care.

This encounter allowed a vulnerable patient with special needs to have access to care while reducing his risk of undesirable exposure. Also, his health care team’s provision of care in the home setting reduced Mr. A’s anxiety and that of his family members.

Home visits have long been an integral part of what it means to be a family physician. In 1930, roughly 40% of all patient-physician encounters in the United States occurred in patients’ homes. By 1980, this number had dropped to < 1%.1 Still, a 1994 survey of American doctors in 3 primary care specialties revealed that 63% of family physicians, more than the other 2 specialties, still made house calls.2 A 2016 analysis of Medicare claims data showed that between 2006 and 2011, only 5% of American doctors overall made house calls on Medicare recipients, but interestingly, the total number of home visits was increasing.3

This resurgence of interest in home health care is due in part to the increasing number of homebound patients in America, which exceeds the number of those in nursing homes.4 Further, a growing body of evidence indicates that home visits improve patient outcomes. And finally, many family physicians whose work lives have been centered around a busy office or hospital practice have found satisfaction in once again seeing patients in their own homes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has of course presented unique challenges—and opportunities, too—for home visits, which we discuss at the end of the article.

Why aren’t more of us making home visits?

For most of us, the decision not to make home visits is simply a matter of time and money. Although Medicare reimbursement for a home visit is typically about 150% that of a comparable office visit,5 it’s difficult, if not impossible, to make 2 home visits in the time you could see 3 patients in the office. So, economically it’s a net loss. Furthermore, we tend to feel less comfortable in our patients’ homes than in our offices. We have less control outside our own environment, and what happens away from our office is often less predictable—sometimes to the point that we may be concerned for our safety.

Continue to: So why make home visits at all?

So why make home visits at all?

First and foremost, home visits improve patient outcomes. This is most evident in our more vulnerable patients: newborns and the elderly, those who have been recently hospitalized, and those at risk because of their particular home situation. Multiple studies have shown that, for elders, home visits reduce functional decline, nursing home admissions, and mortality by around 25% to 33%.6-8 For those at risk of abuse, a recent systematic review showed that home visits reduce intimate partner violence and child abuse.9 Another systematic review demonstrated that patients with diabetes who received home visits vs usual care were more likely to show improvements in quality of life.10 These patients were also more likely to have lower HbA1c levels and lower systolic blood pressure readings.10 A few caveats apply to these studies:

- all of them targeted “vulnerable” patients

- most studies enlisted interdisciplinary teams and had regular team meetings

- most findings reached significance only after multiple home visits.

A further reason for choosing to become involved in home care is that it builds relationships, understanding, and empathy with our patients. “There is deep symbolism in the home visit.... It says, ‘I care enough about you to leave my power base … to come and see you on your own ground.’”11 And this benefit is 2-way; we also grow to understand and appreciate our patients better, especially if they are different from us culturally or socioeconomically.

Home visits allow the medical team to see challenges the patient has grown accustomed to, and perhaps ones that the patient has deemed too insignificant to mention. For the patient, home visits foster a strong sense of trust with the individual doctor and our health delivery network, and they decrease the need to seek emergency services. Finally, it has been demonstrated that provider satisfaction improves when home visits are incorporated into the work week.12

What is the role of community health workers in home-based care?

Community health workers (CHWs), defined as “frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community they serve,”13 can be an integral part of the home-based care team. Although CHWs have variable amounts of formal training, they have a unique perspective on local health beliefs and practices, which can assist the home-care team in providing culturally competent health care services and reduce health care costs.

In a study of children with asthma in Seattle, Washington, patients were randomized to a group that had 4 home visits by CHWs and a group that received usual care. The group that received home visits demonstrated more asthma symptom–free days, improved quality-of-life scores, and fewer urgent care visits.14 Furthermore, the intervention was estimated to save approximately $1300 per patient, resulting in a return on investment of 190%. Similarly, in a study comparing inappropriate emergency department (ED) visits between children who received CHW visits and those who did not, patients in the intervention group were significantly less likely to visit the ED for ambulatory complaints (18.2% vs 35.1%; P = .004).15

Continue to: What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

What is the role of social workersin home-based care?

Social workers can help meet the complex medical and biopsychosocial needs of the homebound population.16 A study by Cohen et al based in Israel concluded that homebound participants had a significantly higher risk for mortality, higher rates of depression, and difficulty completing instrumental activities of daily living when compared with their non-homebound counterparts.17

The Mount Sinai (New York) Visiting Doctors Program (MSVD) is a home-based care team that uses social workers to meet the needs of their complex patients.18 The social workers in the MSVD program provide direct counseling, make referrals to government and community resources, and monitor caregiver burden. Using a combination of measurement tools to assess caregiver burden, Ornstein et al demonstrated that the MSVD program led to a decrease in unmet needs and in caregiver burden.19,20 Caregiver burnout can be assessed using the Caregiver Burden Inventory, a validated 24-item questionnaire.21

What electronic tools are availableto monitor patients at home?

Although expensive in terms of both dollars and personnel time, telemonitoring allows home care providers to receive real-time, updated information regarding their patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One systematic review showed that although telemonitoring of patients with COPD improved quality of life and decreased COPD exacerbations, it did not reduce the risk of hospitalization and, therefore, did not reduce health care costs.22 Telemonitoring in COPD can include transmission of data about spirometry parameters, weight, temperature, blood pressure, sputum color, and 6-minute walk distance.23,24

Congestive heart failure (CHF). A 2010 Cochrane review found that telemonitoring of patients with CHF reduced all-cause mortality (risk ratio [RR] = 0.66; P < .0001).25 The Telemedical Interventional Management in Heart Failure II (TIM-HF2) trial,conducted from 2013 to 2017, compared usual care for CHF patients with care incorporating daily transmission of body weight, blood pressure, heart rate, electrocardiogram tracings, pulse oximetry, and self-rated health status.26 This study showed that the average number of days lost per year due to hospital admission was less in the telemonitoring group than in the usual care group (17.8 days vs. 24.2 days; P = .046). All-cause mortality was also reduced in the telemonitoring group (hazard ratio = 0.70; P = .028).

Continue to: What role do “home hospitals” play?

What role do “home hospitals” play?

Home hospitals provide acute or subacute treatment in a patient’s home for a condition that would normally require hospitalization.27 In a meta-analysis of 61 studies evaluating the effectiveness of home hospitals, this option was more likely to reduce mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 0.81; P = .008) and to reduce readmission rates (OR = 0.75; P = .02).28 In a study of 455 older adults, Leff et al found that hospital-at-home was associated with a shorter length of stay (3.2 vs. 4.9 days; P = .004) and that the mean cost was lower for hospital-at-home vs traditional hospital care.29

However, a 2016 Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials comparing hospital-at-home with traditional hospital care showed that while care in a hospital-at-home may decrease formal costs, if costs for caregivers are taken into account, any difference in cost may disappear.30

Although the evidence for cost saving is variable, hospital-at-home admission has been shown to reduce the likelihood of living in a residential care facility at 6 months (RR = 0.35; P < .0001).30 Further, the same Cochrane review showed that admission avoidance may increase patient satisfaction with the care provided.30

Finally, a recent randomized trial in a Boston-area hospital system showed that patients cared for in hospital-at-home were significantly less likely to be readmitted within 30 days and that adjusted cost was about two-thirds the cost of traditional hospital care.31

What is the physician’s rolein home health care?

While home health care is a team effort, the physician has several crucial roles. First, he or she must make the determination that home care is appropriate and feasible for a particular patient. Appropriate, meaning there is evidence that this patient is likely to benefit from home care. Feasible, meaning there are resources available in the community and family to safely care for the patient at home. “Often a house call will serve as the first step in developing a home-based-management plan.”32

Continue to: Second, the physician serves...

Second, the physician serves an important role in directing and coordinating the team of professionals involved. This primarily means helping the team to communicate with one another. Before home visits begin, the physician’s office should reach out not only to the patient and family, but also to any other health care personnel involved in the patient’s home care. Otherwise, many of the health care providers involved will never have face-to-face interaction with the physician. Creation of the coordinated health team minimizes duplication and miscommunication; it also builds a valuable bond.

How does one go about making a home visit?

Scheduling. What often works best in a busy practice is to schedule home visits for the end of the workday or to devote an entire afternoon to making home visits to several patients in one locale. Also important is scheduling times, if possible, when important family members or other caregivers are at home or when other members of the home care team can accompany you.

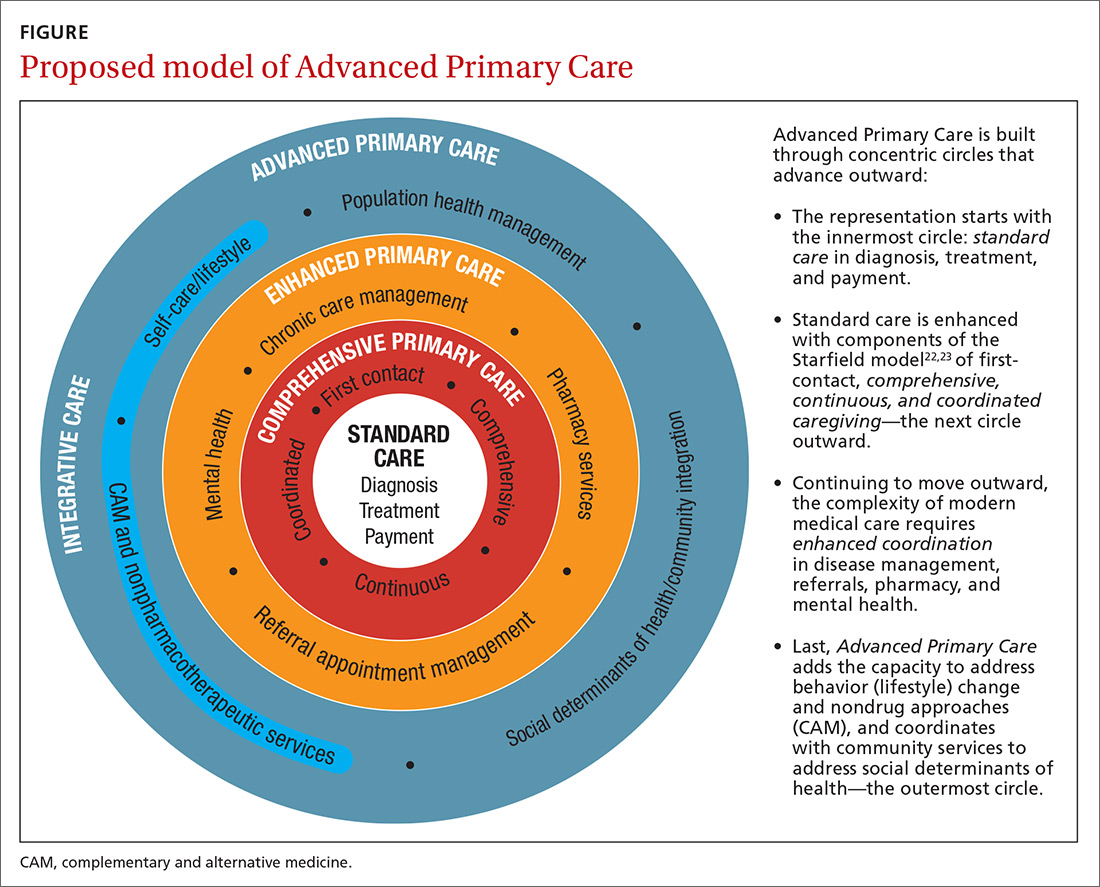

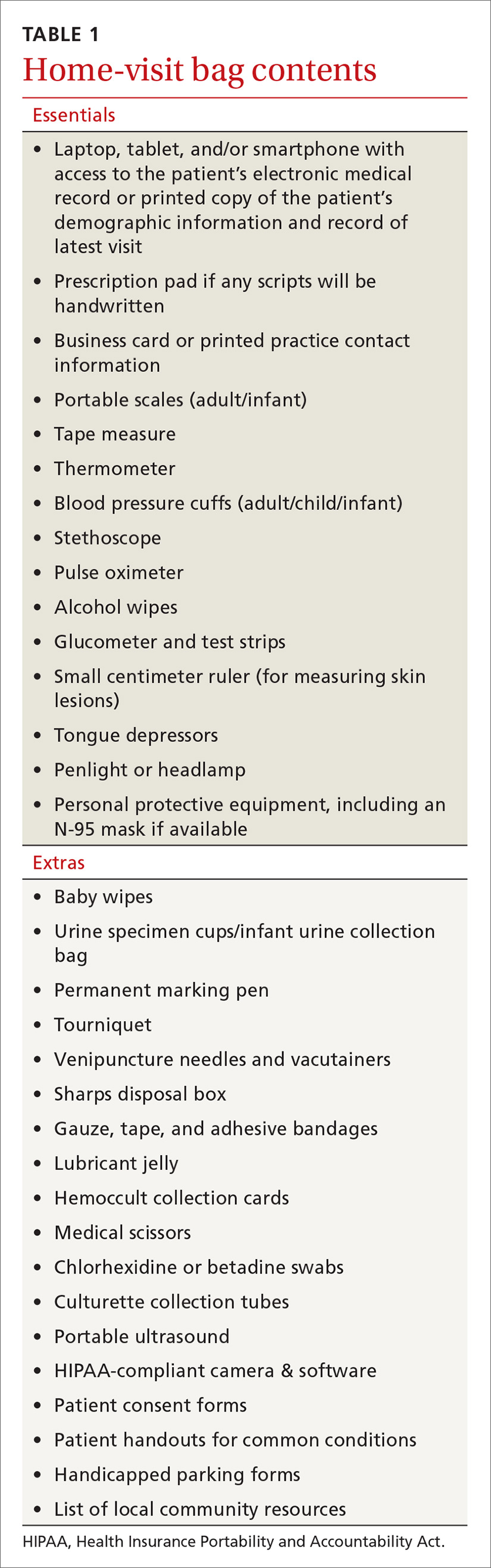

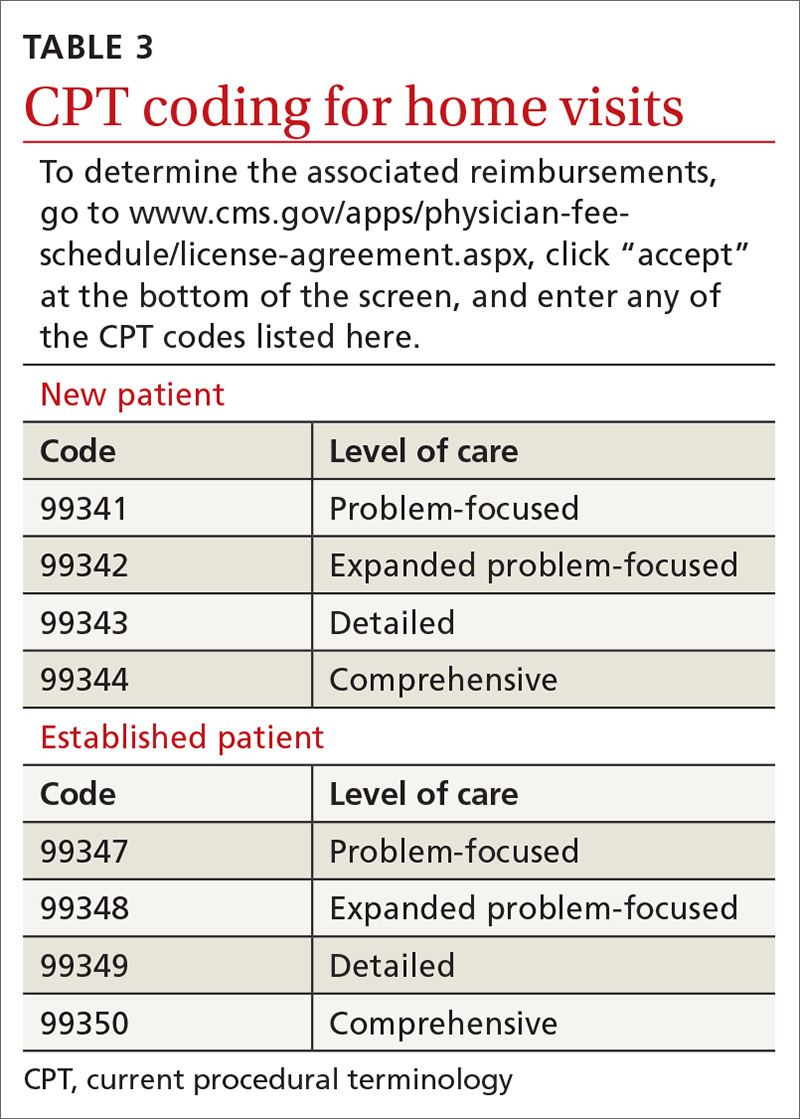

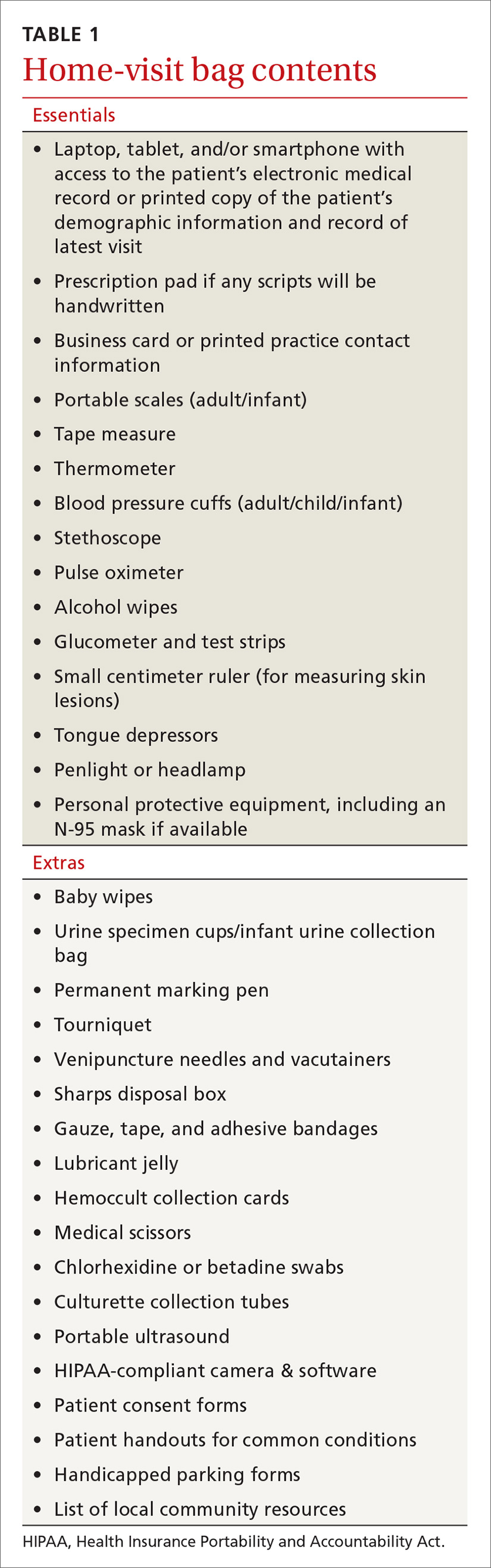

What to bring along. Carry a “home visit bag” that includes equipment you’re likely to need and that is not available away from your office. A minimally equipped visit bag would include different-sized blood pressure cuffs, a glucometer, a pulse oximeter, thermometers, and patient education materials. Other suggested contents are listed in TABLE 1.