User login

Novel oral testosterone replacement therapy headed to FDA

Marius Pharmaceuticals has submitted a new drug application (NDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for Kyzatrex, an oral testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).

With this NDA, the company is seeking approval for Kyzatrex as a treatment for adult men with primary and secondary hypogonadism, also known as testosterone deficiency. Marius has requested a priority review that, if accepted, would result in an anticipated 6-month review period.

Current treatment options for hypogonadal men consist of therapies with safety concerns, such as cardiovascular and metabolic risks, that make patient adherence to treatment very low.

Kyzatrex is a novel oral formulation of testosterone undecanoate administered twice daily in a soft gelatin capsule.

“TRT remains a therapeutic challenge because there are worrisome and conflicting data related to increased cardiovascular disease risk, which has special relevance to high-risk diabetic populations,” Paul S. Jellinger, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization. Furthermore, “injectable depot testosterone may be associated with peak supraphysiological levels and a substantial increase in hemoglobin. Topical testosterone offers more stable levels without a peak and trough, but in some men achieving physiologic levels may be difficult.”

The NDA is supported by results from a 6-month treatment extension of the pivotal phase 3 MRS-TU-2019 study (NCT04467697). Final results from this study have not been presented, but the company wrote in a press release that the results will be published some time in 2021.

They further reported that Kyzatrex was well tolerated by patients, with more than 96% of study participants completing 90 days of treatment in the pivotal phase 3 study. Study patients achieved average testosterone levels in the normal range.

Across the pooled phase 3 trials, the most frequent treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was hypertension, and no serious TEAEs were considered treatment related.

“We are extremely proud to have generated compelling efficacy and safety data in our phase 3 trials,” said Om Dhingra, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Marius. “We look forward to continuing to work collaboratively with the FDA on the review of our application, and if approved, Kyzatrex has the potential to become the standard of care for the treatment of primary and secondary hypogonadism globally.”

“An oral [testosterone] preparation with steady state physiologic levels would be a welcome addition to our choices for therapy assuming, of course, the absence of adverse effects,” explained Dr. Jellinger. “However, the greater challenge of testosterone therapy is the appropriate selection of those suited for testosterone replacement therapy.”

The company also plans to submit a marketing authorization application with the European Medicines Agency in the first half of 2022.

Marius Pharmaceuticals has submitted a new drug application (NDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for Kyzatrex, an oral testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).

With this NDA, the company is seeking approval for Kyzatrex as a treatment for adult men with primary and secondary hypogonadism, also known as testosterone deficiency. Marius has requested a priority review that, if accepted, would result in an anticipated 6-month review period.

Current treatment options for hypogonadal men consist of therapies with safety concerns, such as cardiovascular and metabolic risks, that make patient adherence to treatment very low.

Kyzatrex is a novel oral formulation of testosterone undecanoate administered twice daily in a soft gelatin capsule.

“TRT remains a therapeutic challenge because there are worrisome and conflicting data related to increased cardiovascular disease risk, which has special relevance to high-risk diabetic populations,” Paul S. Jellinger, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization. Furthermore, “injectable depot testosterone may be associated with peak supraphysiological levels and a substantial increase in hemoglobin. Topical testosterone offers more stable levels without a peak and trough, but in some men achieving physiologic levels may be difficult.”

The NDA is supported by results from a 6-month treatment extension of the pivotal phase 3 MRS-TU-2019 study (NCT04467697). Final results from this study have not been presented, but the company wrote in a press release that the results will be published some time in 2021.

They further reported that Kyzatrex was well tolerated by patients, with more than 96% of study participants completing 90 days of treatment in the pivotal phase 3 study. Study patients achieved average testosterone levels in the normal range.

Across the pooled phase 3 trials, the most frequent treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was hypertension, and no serious TEAEs were considered treatment related.

“We are extremely proud to have generated compelling efficacy and safety data in our phase 3 trials,” said Om Dhingra, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Marius. “We look forward to continuing to work collaboratively with the FDA on the review of our application, and if approved, Kyzatrex has the potential to become the standard of care for the treatment of primary and secondary hypogonadism globally.”

“An oral [testosterone] preparation with steady state physiologic levels would be a welcome addition to our choices for therapy assuming, of course, the absence of adverse effects,” explained Dr. Jellinger. “However, the greater challenge of testosterone therapy is the appropriate selection of those suited for testosterone replacement therapy.”

The company also plans to submit a marketing authorization application with the European Medicines Agency in the first half of 2022.

Marius Pharmaceuticals has submitted a new drug application (NDA) to the Food and Drug Administration for Kyzatrex, an oral testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).

With this NDA, the company is seeking approval for Kyzatrex as a treatment for adult men with primary and secondary hypogonadism, also known as testosterone deficiency. Marius has requested a priority review that, if accepted, would result in an anticipated 6-month review period.

Current treatment options for hypogonadal men consist of therapies with safety concerns, such as cardiovascular and metabolic risks, that make patient adherence to treatment very low.

Kyzatrex is a novel oral formulation of testosterone undecanoate administered twice daily in a soft gelatin capsule.

“TRT remains a therapeutic challenge because there are worrisome and conflicting data related to increased cardiovascular disease risk, which has special relevance to high-risk diabetic populations,” Paul S. Jellinger, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami, told this news organization. Furthermore, “injectable depot testosterone may be associated with peak supraphysiological levels and a substantial increase in hemoglobin. Topical testosterone offers more stable levels without a peak and trough, but in some men achieving physiologic levels may be difficult.”

The NDA is supported by results from a 6-month treatment extension of the pivotal phase 3 MRS-TU-2019 study (NCT04467697). Final results from this study have not been presented, but the company wrote in a press release that the results will be published some time in 2021.

They further reported that Kyzatrex was well tolerated by patients, with more than 96% of study participants completing 90 days of treatment in the pivotal phase 3 study. Study patients achieved average testosterone levels in the normal range.

Across the pooled phase 3 trials, the most frequent treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was hypertension, and no serious TEAEs were considered treatment related.

“We are extremely proud to have generated compelling efficacy and safety data in our phase 3 trials,” said Om Dhingra, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Marius. “We look forward to continuing to work collaboratively with the FDA on the review of our application, and if approved, Kyzatrex has the potential to become the standard of care for the treatment of primary and secondary hypogonadism globally.”

“An oral [testosterone] preparation with steady state physiologic levels would be a welcome addition to our choices for therapy assuming, of course, the absence of adverse effects,” explained Dr. Jellinger. “However, the greater challenge of testosterone therapy is the appropriate selection of those suited for testosterone replacement therapy.”

The company also plans to submit a marketing authorization application with the European Medicines Agency in the first half of 2022.

Theory of Planned Behavior Provides A Theoretical Explanation For Enhanced Behavior Change With Genetic-Based Lifestyle Interventions

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a widely accepted theory used to help predict human lifestyle-related behaviors.

Design. Pragmatic, cluster, randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. This study took place at the East Elgin Family Health Team, a primary care clinic in Aylmer, Ontario, Canada. Recruitment occurred between April 2017 and September 2018, with staggered intervention cohorts occurring from May 2017 to September 2019. Participants enrolled in a weight management program at the clinic were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, >18 years of age, English-speaking, willing to undergo genetic testing, having access to a computer with internet at least 1 day per week, and not seeing another health care provider for weight loss advice outside of the study. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy and lactation. All participants provided written informed consent.

Interventions. At baseline, weight management program cohorts (average cohort size was 14 participants) were randomized (1:1) to receive either the standard population-based intervention (Group Lifestyle Balance, or GLB) or a modified GLB intervention, which included the provision of lifestyle genomics (LGx) information and advice (GLB+LGx). Both interventions aimed to assist participants with weight management and healthy lifestyle change, with particular focus on nutrition and physical activity (PA). Interventions were 12 months long, consisting of 23 group-based sessions and 3 one-on-one sessions with a registered dietitian after 3, 6, and 12 months (all sessions were face-to-face). To improve intervention adherence, participants were given reminder calls for their one-on-one appointments and for the start of their program. A sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome indicating that a total of 74 participants were needed (n = 37 per group) for this trial. By September 2019, this sample size was exceeded with 10 randomized groups (n = 140).

The 5 randomized standard GLB groups followed the established GLB program curriculum comprising population-based information and advice while focusing on following a calorie-controlled, moderate-fat (25% of calories) nutrition plan with at least 150 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity PA. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting outlining population-based targets, including acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges for protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

The 5 randomized modified GLB+LGx groups followed a modified GLB program curriculum in which participants were given genetic-based information and advice, which differed from the advice given to the standard GLB group, while focusing on following a calorie-controlled nutrition plan. The nutrition and PA targets were personalized based on their individual genetic variation. For example, participants with the AA variant of FTO (rs9939609) were advised to engage in at least 30 to 60 minutes of PA daily 6 days per week, with muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days per week, rather than receiving the standard population-based advice to aim for 150 minutes weekly of PA with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activity. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting, which outlined genetic-based information and advice related to protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

Measures and analysis. Change in the TPB components (attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control) were measured via a TPB questionnaire at 5 time points: baseline (2-week run-in period), immediately after the first group session (where participants received a summary report of either population-based or genetic-based recommendations depending on group assignment), and after 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were measured on a Likert scale from 1 through 7. Self-reported measures of actual behavioral control (including annual household income, perceptions about events arising in one’s day-to-day life that suddenly take up one’s free time, perceptions about the frequency of feeling ill or tired, and highest achieved level of education) were collected via survey questions and assessed on a Likert scale of 1 through 7. Stage of change was also measured, based on the Transtheoretical Model, using a Likert scale of 1 through 6.

Linear mixed models were used to conduct within- and between-group analyses using SPSS version 26.0, while controlling for measures of actual behavioral control. All analyses were intention-to-treat by originally assigned groups, with mean value imputation conducted for missing data. A Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used. For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and trending towards significance at P = 0.05–0.06.

Main results. Participants consisted of primarily middle-age, middle-income, Caucasian females. Baseline attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA for weight management were generally positive, and participants perceived that undergoing genetic testing would assist with weight management. Participants had overall neutral subjective norms related to friends and family consuming a healthy diet and engaging in PA, but perceived that their friends, family, and health care team (HCT) believed it was important for them to achieve their nutrition and PA recommendations. Participants overall also perceived that their HCT believed genetic testing could assist with weight management. Baseline measures of perceived behavioral control were overall neutral, with baseline stage of change between “motivation” and “action” (short-term; <3 months).

In within-group analyses, significant improvements (P < 0.05) in attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA recommendations for weight management, subjective norms related to both friends and family consuming a healthy diet, and perceived behavioral control in changing PA/dietary intake and managing weight tended to be short-term in the GLB group and long-term for the GLB+LGx group. In all cases of between-group differences for changes in TPB components, the GLB group exhibited reductions in scores, whereas the GLB+LGx group exhibited increases or improvements. Between-group differences (short-term and long-term) in several measures of subjective norms were observed. For example, after 3 months, significant between-group differences were observed in changes in perception that friends believed LGx would help with weight management (P = 0.024). After 12 months, between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed in changes in perception that family members believed genetic testing would help with weight management (P = 0.05). Significant between-group differences and differences trending towards significance were also observed at 12 months for changes in perception that family believed it was important for the participant to achieve the PA recommendations (P = 0.049) and nutrition recommendations (P = 0.05). Between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed at 3 months in attitudes towards the effectiveness of LGx for weight management (P = 0.06). There were no significant between-group differences observed in changes in perceived behavioral control.

Conclusion. Results from this study support the hypothesis that the TPB can help provide a theoretical explanation for why genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice can lead to improvements in lifestyle behavior change.

Commentary

Because health behaviors are critical in areas such as prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, it is important to describe and understand what drives these behaviors.1 Theories are important tools in this effort as they aim to explain and predict health behavior and are used in the design and evaluation of interventions.1 The TPB is one of the most widely accepted behavior change theories and posits that attitudes, subjective norms (or social pressures and behaviors), and perceived behavioral control are significant predictors of an individual’s intention to engage in behaviors.2 TPB has been highlighted in the literature as a validated theory for predicting nutrition and PA intentions and resulting behaviors.3,4

Motivating lifestyle behavior change in clinical practice can be challenging, but some studies have demonstrated how providing genetic information and advice (or lifestyle genomics) can help motivate changes in nutrition and PA among patients.5-7 Because this has yet to be explained using the TPB, this study is an important contribution to the literature as it aimed to determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the TPB. Briefly, results from within-group analyses in this study demonstrated that the provision of genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice (via the GLB+LGx intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change, more so over the long-term, while population-based advice (via the standard GLB intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change over the short-term (eg, attitudes towards dietary fat intake, perceptions that friends and family consume a healthy diet, and perceptions about the impact of genetic-based advice for weight management). In addition, between-group differences in subjective norms observed at 12 months suggested that social pressures and norms may be influencing long-term changes in lifestyle habits.

While key strengths of this study include its pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial design, 12-month intervention duration, and intent-to-treat analyses, there are some study limitations, which are acknowledged by the authors. Generalizability is limited to the demographic characteristics of the study population (ie, middle-aged, middle-income, Caucasian females enrolled in a lifestyle change weight management program). Thus, replication of the study is needed in more diverse study populations and with health-related outcomes beyond weight management. In addition, as the authors indicate, future research should ensure the inclusion of theory-based questionnaires in genetic-based intervention studies assessing lifestyle behavior change to elucidate theory-based mechanisms of change.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Population-based research has consistently indicated that nutrition interventions typically impact short-term dietary changes. Confronting the challenge of long-term adherence to nutrition and PA recommendations requires an understanding of factors impacting long-term motivation and behavior change. With increased attention on and research into genetically tailored lifestyle advice (or lifestyle genomics), it is important for clinical practitioners to be familiar with the evidence supporting these approaches. In addition, this research highlights the need to consider individual factors (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) that may predict successful change in lifestyle habits when providing nutrition and PA recommendations, whether population-based or genetically tailored.

—Katrina F. Mateo, PhD, MPH

1. Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP. Theory-based health behavior change: Developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:698-716.

2. Ajzen I. The Theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1113-1127.

3. McDermott MS, Oliver M, Simnadis T, et al. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015;81:150-156.

4. McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5:97-144.

5. Hietaranta-Luoma H-L, Tahvonen R, Iso-Touru T, et al A. An intervention study of individual, APOE genotype-based dietary and physical-activity advice: impact on health behavior. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2014;7:161-174.

6. Nielsen DE, El-Sohemy A. Disclosure of genetic information and change in dietary intake: a randomized controlled trial. DeAngelis MM, ed. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112665.

7. Egglestone C, Morris A, O’Brien A. Effect of direct‐to‐consumer genetic tests on health behaviour and anxiety: a survey of consumers and potential consumers. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:565-575.

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a widely accepted theory used to help predict human lifestyle-related behaviors.

Design. Pragmatic, cluster, randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. This study took place at the East Elgin Family Health Team, a primary care clinic in Aylmer, Ontario, Canada. Recruitment occurred between April 2017 and September 2018, with staggered intervention cohorts occurring from May 2017 to September 2019. Participants enrolled in a weight management program at the clinic were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, >18 years of age, English-speaking, willing to undergo genetic testing, having access to a computer with internet at least 1 day per week, and not seeing another health care provider for weight loss advice outside of the study. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy and lactation. All participants provided written informed consent.

Interventions. At baseline, weight management program cohorts (average cohort size was 14 participants) were randomized (1:1) to receive either the standard population-based intervention (Group Lifestyle Balance, or GLB) or a modified GLB intervention, which included the provision of lifestyle genomics (LGx) information and advice (GLB+LGx). Both interventions aimed to assist participants with weight management and healthy lifestyle change, with particular focus on nutrition and physical activity (PA). Interventions were 12 months long, consisting of 23 group-based sessions and 3 one-on-one sessions with a registered dietitian after 3, 6, and 12 months (all sessions were face-to-face). To improve intervention adherence, participants were given reminder calls for their one-on-one appointments and for the start of their program. A sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome indicating that a total of 74 participants were needed (n = 37 per group) for this trial. By September 2019, this sample size was exceeded with 10 randomized groups (n = 140).

The 5 randomized standard GLB groups followed the established GLB program curriculum comprising population-based information and advice while focusing on following a calorie-controlled, moderate-fat (25% of calories) nutrition plan with at least 150 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity PA. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting outlining population-based targets, including acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges for protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

The 5 randomized modified GLB+LGx groups followed a modified GLB program curriculum in which participants were given genetic-based information and advice, which differed from the advice given to the standard GLB group, while focusing on following a calorie-controlled nutrition plan. The nutrition and PA targets were personalized based on their individual genetic variation. For example, participants with the AA variant of FTO (rs9939609) were advised to engage in at least 30 to 60 minutes of PA daily 6 days per week, with muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days per week, rather than receiving the standard population-based advice to aim for 150 minutes weekly of PA with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activity. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting, which outlined genetic-based information and advice related to protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

Measures and analysis. Change in the TPB components (attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control) were measured via a TPB questionnaire at 5 time points: baseline (2-week run-in period), immediately after the first group session (where participants received a summary report of either population-based or genetic-based recommendations depending on group assignment), and after 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were measured on a Likert scale from 1 through 7. Self-reported measures of actual behavioral control (including annual household income, perceptions about events arising in one’s day-to-day life that suddenly take up one’s free time, perceptions about the frequency of feeling ill or tired, and highest achieved level of education) were collected via survey questions and assessed on a Likert scale of 1 through 7. Stage of change was also measured, based on the Transtheoretical Model, using a Likert scale of 1 through 6.

Linear mixed models were used to conduct within- and between-group analyses using SPSS version 26.0, while controlling for measures of actual behavioral control. All analyses were intention-to-treat by originally assigned groups, with mean value imputation conducted for missing data. A Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used. For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and trending towards significance at P = 0.05–0.06.

Main results. Participants consisted of primarily middle-age, middle-income, Caucasian females. Baseline attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA for weight management were generally positive, and participants perceived that undergoing genetic testing would assist with weight management. Participants had overall neutral subjective norms related to friends and family consuming a healthy diet and engaging in PA, but perceived that their friends, family, and health care team (HCT) believed it was important for them to achieve their nutrition and PA recommendations. Participants overall also perceived that their HCT believed genetic testing could assist with weight management. Baseline measures of perceived behavioral control were overall neutral, with baseline stage of change between “motivation” and “action” (short-term; <3 months).

In within-group analyses, significant improvements (P < 0.05) in attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA recommendations for weight management, subjective norms related to both friends and family consuming a healthy diet, and perceived behavioral control in changing PA/dietary intake and managing weight tended to be short-term in the GLB group and long-term for the GLB+LGx group. In all cases of between-group differences for changes in TPB components, the GLB group exhibited reductions in scores, whereas the GLB+LGx group exhibited increases or improvements. Between-group differences (short-term and long-term) in several measures of subjective norms were observed. For example, after 3 months, significant between-group differences were observed in changes in perception that friends believed LGx would help with weight management (P = 0.024). After 12 months, between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed in changes in perception that family members believed genetic testing would help with weight management (P = 0.05). Significant between-group differences and differences trending towards significance were also observed at 12 months for changes in perception that family believed it was important for the participant to achieve the PA recommendations (P = 0.049) and nutrition recommendations (P = 0.05). Between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed at 3 months in attitudes towards the effectiveness of LGx for weight management (P = 0.06). There were no significant between-group differences observed in changes in perceived behavioral control.

Conclusion. Results from this study support the hypothesis that the TPB can help provide a theoretical explanation for why genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice can lead to improvements in lifestyle behavior change.

Commentary

Because health behaviors are critical in areas such as prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, it is important to describe and understand what drives these behaviors.1 Theories are important tools in this effort as they aim to explain and predict health behavior and are used in the design and evaluation of interventions.1 The TPB is one of the most widely accepted behavior change theories and posits that attitudes, subjective norms (or social pressures and behaviors), and perceived behavioral control are significant predictors of an individual’s intention to engage in behaviors.2 TPB has been highlighted in the literature as a validated theory for predicting nutrition and PA intentions and resulting behaviors.3,4

Motivating lifestyle behavior change in clinical practice can be challenging, but some studies have demonstrated how providing genetic information and advice (or lifestyle genomics) can help motivate changes in nutrition and PA among patients.5-7 Because this has yet to be explained using the TPB, this study is an important contribution to the literature as it aimed to determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the TPB. Briefly, results from within-group analyses in this study demonstrated that the provision of genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice (via the GLB+LGx intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change, more so over the long-term, while population-based advice (via the standard GLB intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change over the short-term (eg, attitudes towards dietary fat intake, perceptions that friends and family consume a healthy diet, and perceptions about the impact of genetic-based advice for weight management). In addition, between-group differences in subjective norms observed at 12 months suggested that social pressures and norms may be influencing long-term changes in lifestyle habits.

While key strengths of this study include its pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial design, 12-month intervention duration, and intent-to-treat analyses, there are some study limitations, which are acknowledged by the authors. Generalizability is limited to the demographic characteristics of the study population (ie, middle-aged, middle-income, Caucasian females enrolled in a lifestyle change weight management program). Thus, replication of the study is needed in more diverse study populations and with health-related outcomes beyond weight management. In addition, as the authors indicate, future research should ensure the inclusion of theory-based questionnaires in genetic-based intervention studies assessing lifestyle behavior change to elucidate theory-based mechanisms of change.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Population-based research has consistently indicated that nutrition interventions typically impact short-term dietary changes. Confronting the challenge of long-term adherence to nutrition and PA recommendations requires an understanding of factors impacting long-term motivation and behavior change. With increased attention on and research into genetically tailored lifestyle advice (or lifestyle genomics), it is important for clinical practitioners to be familiar with the evidence supporting these approaches. In addition, this research highlights the need to consider individual factors (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) that may predict successful change in lifestyle habits when providing nutrition and PA recommendations, whether population-based or genetically tailored.

—Katrina F. Mateo, PhD, MPH

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a widely accepted theory used to help predict human lifestyle-related behaviors.

Design. Pragmatic, cluster, randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. This study took place at the East Elgin Family Health Team, a primary care clinic in Aylmer, Ontario, Canada. Recruitment occurred between April 2017 and September 2018, with staggered intervention cohorts occurring from May 2017 to September 2019. Participants enrolled in a weight management program at the clinic were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, >18 years of age, English-speaking, willing to undergo genetic testing, having access to a computer with internet at least 1 day per week, and not seeing another health care provider for weight loss advice outside of the study. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy and lactation. All participants provided written informed consent.

Interventions. At baseline, weight management program cohorts (average cohort size was 14 participants) were randomized (1:1) to receive either the standard population-based intervention (Group Lifestyle Balance, or GLB) or a modified GLB intervention, which included the provision of lifestyle genomics (LGx) information and advice (GLB+LGx). Both interventions aimed to assist participants with weight management and healthy lifestyle change, with particular focus on nutrition and physical activity (PA). Interventions were 12 months long, consisting of 23 group-based sessions and 3 one-on-one sessions with a registered dietitian after 3, 6, and 12 months (all sessions were face-to-face). To improve intervention adherence, participants were given reminder calls for their one-on-one appointments and for the start of their program. A sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome indicating that a total of 74 participants were needed (n = 37 per group) for this trial. By September 2019, this sample size was exceeded with 10 randomized groups (n = 140).

The 5 randomized standard GLB groups followed the established GLB program curriculum comprising population-based information and advice while focusing on following a calorie-controlled, moderate-fat (25% of calories) nutrition plan with at least 150 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity PA. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting outlining population-based targets, including acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges for protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

The 5 randomized modified GLB+LGx groups followed a modified GLB program curriculum in which participants were given genetic-based information and advice, which differed from the advice given to the standard GLB group, while focusing on following a calorie-controlled nutrition plan. The nutrition and PA targets were personalized based on their individual genetic variation. For example, participants with the AA variant of FTO (rs9939609) were advised to engage in at least 30 to 60 minutes of PA daily 6 days per week, with muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days per week, rather than receiving the standard population-based advice to aim for 150 minutes weekly of PA with at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening activity. Participants were also provided with a 1-page summary report of their nutrition and PA guidelines at the first group meeting, which outlined genetic-based information and advice related to protein, total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, sodium, calories, snacking, and PA.

Measures and analysis. Change in the TPB components (attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control) were measured via a TPB questionnaire at 5 time points: baseline (2-week run-in period), immediately after the first group session (where participants received a summary report of either population-based or genetic-based recommendations depending on group assignment), and after 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were measured on a Likert scale from 1 through 7. Self-reported measures of actual behavioral control (including annual household income, perceptions about events arising in one’s day-to-day life that suddenly take up one’s free time, perceptions about the frequency of feeling ill or tired, and highest achieved level of education) were collected via survey questions and assessed on a Likert scale of 1 through 7. Stage of change was also measured, based on the Transtheoretical Model, using a Likert scale of 1 through 6.

Linear mixed models were used to conduct within- and between-group analyses using SPSS version 26.0, while controlling for measures of actual behavioral control. All analyses were intention-to-treat by originally assigned groups, with mean value imputation conducted for missing data. A Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used. For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and trending towards significance at P = 0.05–0.06.

Main results. Participants consisted of primarily middle-age, middle-income, Caucasian females. Baseline attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA for weight management were generally positive, and participants perceived that undergoing genetic testing would assist with weight management. Participants had overall neutral subjective norms related to friends and family consuming a healthy diet and engaging in PA, but perceived that their friends, family, and health care team (HCT) believed it was important for them to achieve their nutrition and PA recommendations. Participants overall also perceived that their HCT believed genetic testing could assist with weight management. Baseline measures of perceived behavioral control were overall neutral, with baseline stage of change between “motivation” and “action” (short-term; <3 months).

In within-group analyses, significant improvements (P < 0.05) in attitudes towards the effectiveness of nutrition and PA recommendations for weight management, subjective norms related to both friends and family consuming a healthy diet, and perceived behavioral control in changing PA/dietary intake and managing weight tended to be short-term in the GLB group and long-term for the GLB+LGx group. In all cases of between-group differences for changes in TPB components, the GLB group exhibited reductions in scores, whereas the GLB+LGx group exhibited increases or improvements. Between-group differences (short-term and long-term) in several measures of subjective norms were observed. For example, after 3 months, significant between-group differences were observed in changes in perception that friends believed LGx would help with weight management (P = 0.024). After 12 months, between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed in changes in perception that family members believed genetic testing would help with weight management (P = 0.05). Significant between-group differences and differences trending towards significance were also observed at 12 months for changes in perception that family believed it was important for the participant to achieve the PA recommendations (P = 0.049) and nutrition recommendations (P = 0.05). Between-group differences trending towards significance were also observed at 3 months in attitudes towards the effectiveness of LGx for weight management (P = 0.06). There were no significant between-group differences observed in changes in perceived behavioral control.

Conclusion. Results from this study support the hypothesis that the TPB can help provide a theoretical explanation for why genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice can lead to improvements in lifestyle behavior change.

Commentary

Because health behaviors are critical in areas such as prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, it is important to describe and understand what drives these behaviors.1 Theories are important tools in this effort as they aim to explain and predict health behavior and are used in the design and evaluation of interventions.1 The TPB is one of the most widely accepted behavior change theories and posits that attitudes, subjective norms (or social pressures and behaviors), and perceived behavioral control are significant predictors of an individual’s intention to engage in behaviors.2 TPB has been highlighted in the literature as a validated theory for predicting nutrition and PA intentions and resulting behaviors.3,4

Motivating lifestyle behavior change in clinical practice can be challenging, but some studies have demonstrated how providing genetic information and advice (or lifestyle genomics) can help motivate changes in nutrition and PA among patients.5-7 Because this has yet to be explained using the TPB, this study is an important contribution to the literature as it aimed to determine the impact of providing genetically tailored and population-based lifestyle advice for weight management on key constructs of the TPB. Briefly, results from within-group analyses in this study demonstrated that the provision of genetically tailored lifestyle information and advice (via the GLB+LGx intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change, more so over the long-term, while population-based advice (via the standard GLB intervention) tended to impact antecedents of behavior change over the short-term (eg, attitudes towards dietary fat intake, perceptions that friends and family consume a healthy diet, and perceptions about the impact of genetic-based advice for weight management). In addition, between-group differences in subjective norms observed at 12 months suggested that social pressures and norms may be influencing long-term changes in lifestyle habits.

While key strengths of this study include its pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial design, 12-month intervention duration, and intent-to-treat analyses, there are some study limitations, which are acknowledged by the authors. Generalizability is limited to the demographic characteristics of the study population (ie, middle-aged, middle-income, Caucasian females enrolled in a lifestyle change weight management program). Thus, replication of the study is needed in more diverse study populations and with health-related outcomes beyond weight management. In addition, as the authors indicate, future research should ensure the inclusion of theory-based questionnaires in genetic-based intervention studies assessing lifestyle behavior change to elucidate theory-based mechanisms of change.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Population-based research has consistently indicated that nutrition interventions typically impact short-term dietary changes. Confronting the challenge of long-term adherence to nutrition and PA recommendations requires an understanding of factors impacting long-term motivation and behavior change. With increased attention on and research into genetically tailored lifestyle advice (or lifestyle genomics), it is important for clinical practitioners to be familiar with the evidence supporting these approaches. In addition, this research highlights the need to consider individual factors (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) that may predict successful change in lifestyle habits when providing nutrition and PA recommendations, whether population-based or genetically tailored.

—Katrina F. Mateo, PhD, MPH

1. Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP. Theory-based health behavior change: Developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:698-716.

2. Ajzen I. The Theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1113-1127.

3. McDermott MS, Oliver M, Simnadis T, et al. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015;81:150-156.

4. McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5:97-144.

5. Hietaranta-Luoma H-L, Tahvonen R, Iso-Touru T, et al A. An intervention study of individual, APOE genotype-based dietary and physical-activity advice: impact on health behavior. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2014;7:161-174.

6. Nielsen DE, El-Sohemy A. Disclosure of genetic information and change in dietary intake: a randomized controlled trial. DeAngelis MM, ed. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112665.

7. Egglestone C, Morris A, O’Brien A. Effect of direct‐to‐consumer genetic tests on health behaviour and anxiety: a survey of consumers and potential consumers. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:565-575.

1. Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP. Theory-based health behavior change: Developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:698-716.

2. Ajzen I. The Theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1113-1127.

3. McDermott MS, Oliver M, Simnadis T, et al. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med (Baltim). 2015;81:150-156.

4. McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5:97-144.

5. Hietaranta-Luoma H-L, Tahvonen R, Iso-Touru T, et al A. An intervention study of individual, APOE genotype-based dietary and physical-activity advice: impact on health behavior. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2014;7:161-174.

6. Nielsen DE, El-Sohemy A. Disclosure of genetic information and change in dietary intake: a randomized controlled trial. DeAngelis MM, ed. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112665.

7. Egglestone C, Morris A, O’Brien A. Effect of direct‐to‐consumer genetic tests on health behaviour and anxiety: a survey of consumers and potential consumers. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:565-575.

20-year-old man • sudden-onset chest pain • worsening pain with cough and exertion • Dx?

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 3-day history of nonradiating chest pain located at the center of his chest. Past medical history included idiopathic neonatal giant-cell hepatitis and subsequent liver transplant at 1 month of age; he had been followed by the transplant team without rejection or infection and was in otherwise good health prior to the chest pain.

On the day of symptom onset, he was walking inside his house and fell to his knees with a chest pain described as “a punch” to the center of the chest that lasted for a few seconds. He was able to continue his daily activities without limitation despite a constant, squeezing, centrally located chest pain. The pain worsened with cough and exertion.

A few hours later, he went to an urgent care center for evaluation. There, he reported, his chest radiograph and electrocardiogram (EKG) results were normal and he was given a diagnosis of musculoskeletal chest pain. Over the next 3 days, his chest pain persisted but did not worsen. He was taking 500 mg of naproxen every 8 hours with no improvement. No other acute or chronic medications were being taken. He had no significant family history. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

On physical exam, his vital statistics included a height of 6’4”; weight, 261 lb; body mass index, 31.8; temperature, 98.7 °F; blood pressure, 134/77 mm Hg; heart rate, 92 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 96%. Throughout the exam, he demonstrated no acute distress, appeared well, and was talkative; however, he reported having a “constant, squeezing” chest pain that did not worsen with palpation of the chest. The rest of his physical exam was unremarkable.

Although he reported that his EKG and chest radiograph were normal 3 days prior, repeat chest radiograph and EKG were ordered due to his unexplained, active chest pain and the lack of immediate access to the prior results.

THE DIAGNOSIS

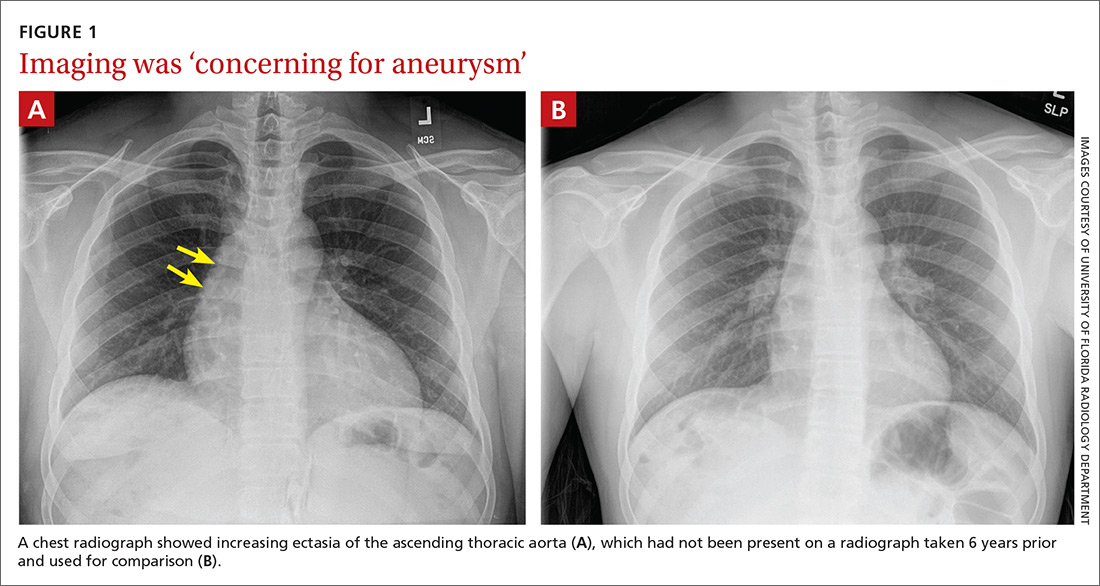

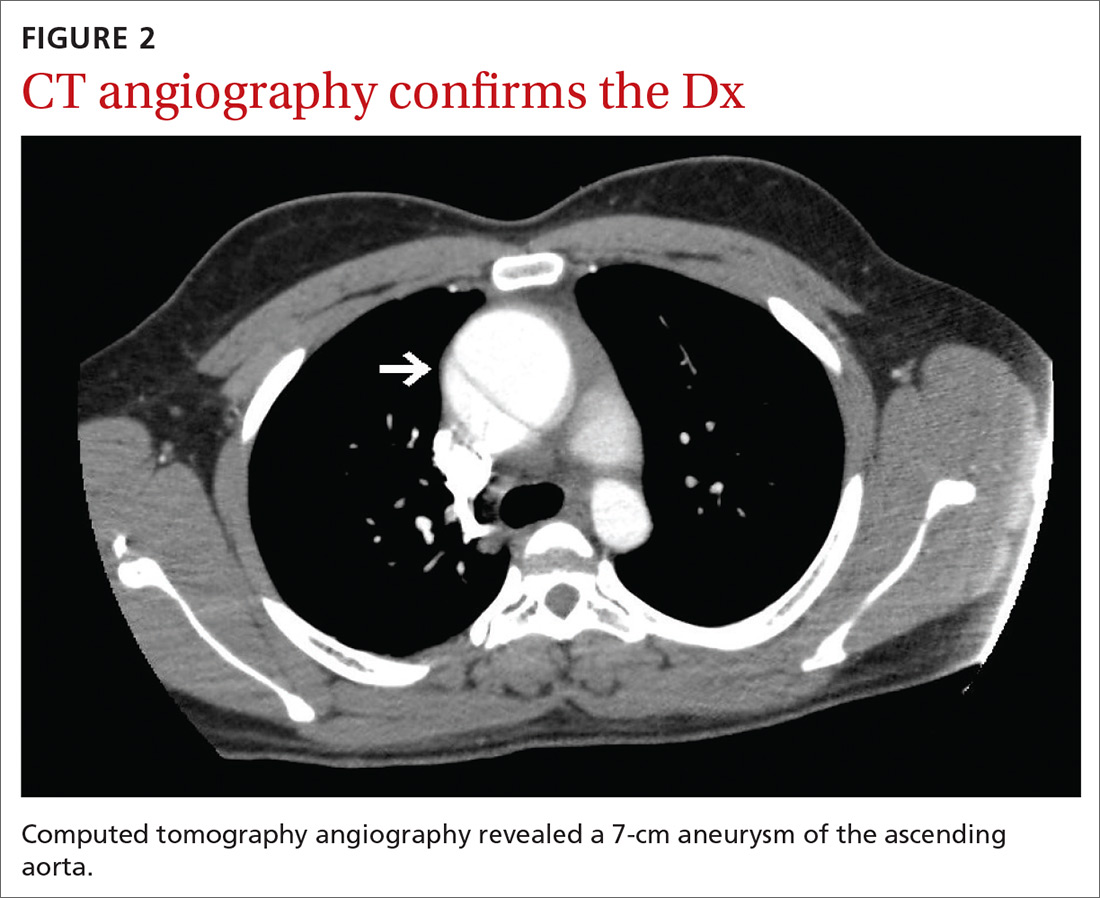

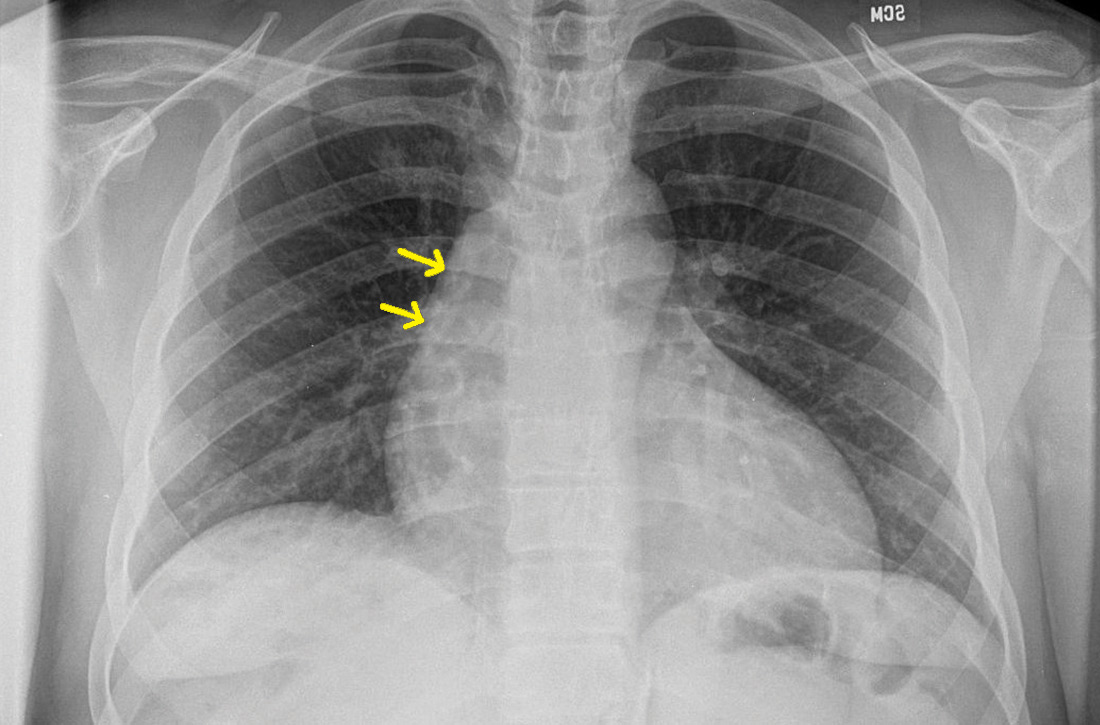

The chest radiograph (FIGURE 1A) showed a “mildly ectatic ascending thoracic aorta” that had increased since a chest radiograph from 6 years prior (FIGURE 1B) and “was concerning for an aneurysm.” Computed tomography (CT) angiography (FIGURE 2) then confirmed a 7-cm aneurysm of the ascending aorta, with findings suggestive of a retrograde ascending aortic dissection.

DISCUSSION

The average age of a patient with acute aortic dissection (AAD) is 63 years; only 7% occur in people younger than 40.1 AAD is often accompanied by a predisposing risk factor such as a connective tissue disease, bicuspid aortic valve, longstanding hypertension, trauma, or larger aortic dimensions.2,3 Younger patients are more likely to have predisposing risk factors of Marfan syndrome, prior aortic surgery, or a bicuspid aortic valve.3

Continue to: A literature review did not reveal...

A literature review did not reveal any known correlation between the patient’s history of giant-cell hepatitis or antirejection therapy with thoracic aortic dissection. Furthermore, liver transplant is not known to be a specific risk factor for AAD in pediatric patients or outside the immediate postoperative period. Therefore, there were no known predisposing risk factors for AAD in our patient.

The most common clinical feature of AAD is chest pain, which occurs in 75% of patients.1 Other clinical symptoms include hypertension and diaphoresis.2,4 However, classic clinical findings are not always displayed, making the diagnosis difficult.2,4 The classical description of “tearing pain” is seen in only 51% of patients, and 5% to 15% of patients present without any pain.1

Commonly missed or misdiagnosed. The diagnosis of AAD has been missed during the initial exam in 38% of patients.4 As seen in our case, symptoms may be initially diagnosed as musculoskeletal chest pain. Based on symptoms, AAD can be incorrectly diagnosed as an acute myocardial infarction or vascular embolization.2,4

Every hour after symptom onset, the mortality rate of untreated AAD increases 1% to 2%,with no difference based on age.3,4 Different reports have shown mortality rates between 7% and 30%.4

Effective imaging is crucial to the diagnosis and treatment of AAD, given the occurrence of atypical presentation, missed diagnosis, and high mortality rate.4 A chest radiograph will show a widened mediastinum, but the preferred diagnostic tests are a CT or transthoracic echocardiogram.2,4 Once the diagnosis of AAD is confirmed, an aortic angiogram is the preferred test to determine the extent of the dissection prior to surgical treatment.2

Continue to: Classification dictates treatment

Classification dictates treatment. AAD is classified based on where the dissection of the aorta occurs. If the dissection involves the ascending aorta, it is classified as a type A AAD and should immediately be treated with emergent surgery in order to prevent complications including myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade, and aortic rupture.2,4,5 If the dissection is limited to the descending aorta, it is classified as a type B AAD and can be medically managed by controlling pain and lowering blood pressure; if symptoms persist, surgical management may be required.2 After hospital discharge, AAD patients are followed closely with medical therapy, serial imaging, and reoperation if necessary.4

Our patient underwent emergent surgery for aortic root/ascending aortic replacement with a mechanical valve. He tolerated the procedure well. Surgical tissue pathology of the aortic segment showed a wall of elastic vessel with medial degeneration and dissection, and the tissue pathology of the aorta leaflets showed valvular tissue with myxoid degeneration.

THE TAKEAWAY

It is critical to keep AAD in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with acute onset of chest pain, as AAD often has an atypical presentation and can easily be misdiagnosed. Effective imaging is crucial to diagnosis, and immediate treatment is essential to patient survival.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rachel A. Reedy, PA, University of Florida, Department of General Pediatrics, 7046 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32608; [email protected]

1. Pineault J, Ouimet D, Pichette V, Vallée M. A case of aortic dissection in a young adult: a refresher of the literature of this “great masquerader.” Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:889-893.

2. Agabegi SS, Agabegi ElD, Ring AC. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In: Jackson A, ed. Step-up to Medicine. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:54-55.

3. Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, et al. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665-669.

4. Tsai TT, Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:149-159.

5. Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, et al. Role of age in acute type A aortic dissection outcome: Report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:784-789.

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 3-day history of nonradiating chest pain located at the center of his chest. Past medical history included idiopathic neonatal giant-cell hepatitis and subsequent liver transplant at 1 month of age; he had been followed by the transplant team without rejection or infection and was in otherwise good health prior to the chest pain.

On the day of symptom onset, he was walking inside his house and fell to his knees with a chest pain described as “a punch” to the center of the chest that lasted for a few seconds. He was able to continue his daily activities without limitation despite a constant, squeezing, centrally located chest pain. The pain worsened with cough and exertion.

A few hours later, he went to an urgent care center for evaluation. There, he reported, his chest radiograph and electrocardiogram (EKG) results were normal and he was given a diagnosis of musculoskeletal chest pain. Over the next 3 days, his chest pain persisted but did not worsen. He was taking 500 mg of naproxen every 8 hours with no improvement. No other acute or chronic medications were being taken. He had no significant family history. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

On physical exam, his vital statistics included a height of 6’4”; weight, 261 lb; body mass index, 31.8; temperature, 98.7 °F; blood pressure, 134/77 mm Hg; heart rate, 92 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 96%. Throughout the exam, he demonstrated no acute distress, appeared well, and was talkative; however, he reported having a “constant, squeezing” chest pain that did not worsen with palpation of the chest. The rest of his physical exam was unremarkable.

Although he reported that his EKG and chest radiograph were normal 3 days prior, repeat chest radiograph and EKG were ordered due to his unexplained, active chest pain and the lack of immediate access to the prior results.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The chest radiograph (FIGURE 1A) showed a “mildly ectatic ascending thoracic aorta” that had increased since a chest radiograph from 6 years prior (FIGURE 1B) and “was concerning for an aneurysm.” Computed tomography (CT) angiography (FIGURE 2) then confirmed a 7-cm aneurysm of the ascending aorta, with findings suggestive of a retrograde ascending aortic dissection.

DISCUSSION

The average age of a patient with acute aortic dissection (AAD) is 63 years; only 7% occur in people younger than 40.1 AAD is often accompanied by a predisposing risk factor such as a connective tissue disease, bicuspid aortic valve, longstanding hypertension, trauma, or larger aortic dimensions.2,3 Younger patients are more likely to have predisposing risk factors of Marfan syndrome, prior aortic surgery, or a bicuspid aortic valve.3

Continue to: A literature review did not reveal...

A literature review did not reveal any known correlation between the patient’s history of giant-cell hepatitis or antirejection therapy with thoracic aortic dissection. Furthermore, liver transplant is not known to be a specific risk factor for AAD in pediatric patients or outside the immediate postoperative period. Therefore, there were no known predisposing risk factors for AAD in our patient.

The most common clinical feature of AAD is chest pain, which occurs in 75% of patients.1 Other clinical symptoms include hypertension and diaphoresis.2,4 However, classic clinical findings are not always displayed, making the diagnosis difficult.2,4 The classical description of “tearing pain” is seen in only 51% of patients, and 5% to 15% of patients present without any pain.1

Commonly missed or misdiagnosed. The diagnosis of AAD has been missed during the initial exam in 38% of patients.4 As seen in our case, symptoms may be initially diagnosed as musculoskeletal chest pain. Based on symptoms, AAD can be incorrectly diagnosed as an acute myocardial infarction or vascular embolization.2,4

Every hour after symptom onset, the mortality rate of untreated AAD increases 1% to 2%,with no difference based on age.3,4 Different reports have shown mortality rates between 7% and 30%.4

Effective imaging is crucial to the diagnosis and treatment of AAD, given the occurrence of atypical presentation, missed diagnosis, and high mortality rate.4 A chest radiograph will show a widened mediastinum, but the preferred diagnostic tests are a CT or transthoracic echocardiogram.2,4 Once the diagnosis of AAD is confirmed, an aortic angiogram is the preferred test to determine the extent of the dissection prior to surgical treatment.2

Continue to: Classification dictates treatment

Classification dictates treatment. AAD is classified based on where the dissection of the aorta occurs. If the dissection involves the ascending aorta, it is classified as a type A AAD and should immediately be treated with emergent surgery in order to prevent complications including myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade, and aortic rupture.2,4,5 If the dissection is limited to the descending aorta, it is classified as a type B AAD and can be medically managed by controlling pain and lowering blood pressure; if symptoms persist, surgical management may be required.2 After hospital discharge, AAD patients are followed closely with medical therapy, serial imaging, and reoperation if necessary.4

Our patient underwent emergent surgery for aortic root/ascending aortic replacement with a mechanical valve. He tolerated the procedure well. Surgical tissue pathology of the aortic segment showed a wall of elastic vessel with medial degeneration and dissection, and the tissue pathology of the aorta leaflets showed valvular tissue with myxoid degeneration.

THE TAKEAWAY

It is critical to keep AAD in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with acute onset of chest pain, as AAD often has an atypical presentation and can easily be misdiagnosed. Effective imaging is crucial to diagnosis, and immediate treatment is essential to patient survival.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rachel A. Reedy, PA, University of Florida, Department of General Pediatrics, 7046 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32608; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 20-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 3-day history of nonradiating chest pain located at the center of his chest. Past medical history included idiopathic neonatal giant-cell hepatitis and subsequent liver transplant at 1 month of age; he had been followed by the transplant team without rejection or infection and was in otherwise good health prior to the chest pain.

On the day of symptom onset, he was walking inside his house and fell to his knees with a chest pain described as “a punch” to the center of the chest that lasted for a few seconds. He was able to continue his daily activities without limitation despite a constant, squeezing, centrally located chest pain. The pain worsened with cough and exertion.

A few hours later, he went to an urgent care center for evaluation. There, he reported, his chest radiograph and electrocardiogram (EKG) results were normal and he was given a diagnosis of musculoskeletal chest pain. Over the next 3 days, his chest pain persisted but did not worsen. He was taking 500 mg of naproxen every 8 hours with no improvement. No other acute or chronic medications were being taken. He had no significant family history. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

On physical exam, his vital statistics included a height of 6’4”; weight, 261 lb; body mass index, 31.8; temperature, 98.7 °F; blood pressure, 134/77 mm Hg; heart rate, 92 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 96%. Throughout the exam, he demonstrated no acute distress, appeared well, and was talkative; however, he reported having a “constant, squeezing” chest pain that did not worsen with palpation of the chest. The rest of his physical exam was unremarkable.

Although he reported that his EKG and chest radiograph were normal 3 days prior, repeat chest radiograph and EKG were ordered due to his unexplained, active chest pain and the lack of immediate access to the prior results.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The chest radiograph (FIGURE 1A) showed a “mildly ectatic ascending thoracic aorta” that had increased since a chest radiograph from 6 years prior (FIGURE 1B) and “was concerning for an aneurysm.” Computed tomography (CT) angiography (FIGURE 2) then confirmed a 7-cm aneurysm of the ascending aorta, with findings suggestive of a retrograde ascending aortic dissection.

DISCUSSION

The average age of a patient with acute aortic dissection (AAD) is 63 years; only 7% occur in people younger than 40.1 AAD is often accompanied by a predisposing risk factor such as a connective tissue disease, bicuspid aortic valve, longstanding hypertension, trauma, or larger aortic dimensions.2,3 Younger patients are more likely to have predisposing risk factors of Marfan syndrome, prior aortic surgery, or a bicuspid aortic valve.3

Continue to: A literature review did not reveal...

A literature review did not reveal any known correlation between the patient’s history of giant-cell hepatitis or antirejection therapy with thoracic aortic dissection. Furthermore, liver transplant is not known to be a specific risk factor for AAD in pediatric patients or outside the immediate postoperative period. Therefore, there were no known predisposing risk factors for AAD in our patient.

The most common clinical feature of AAD is chest pain, which occurs in 75% of patients.1 Other clinical symptoms include hypertension and diaphoresis.2,4 However, classic clinical findings are not always displayed, making the diagnosis difficult.2,4 The classical description of “tearing pain” is seen in only 51% of patients, and 5% to 15% of patients present without any pain.1

Commonly missed or misdiagnosed. The diagnosis of AAD has been missed during the initial exam in 38% of patients.4 As seen in our case, symptoms may be initially diagnosed as musculoskeletal chest pain. Based on symptoms, AAD can be incorrectly diagnosed as an acute myocardial infarction or vascular embolization.2,4

Every hour after symptom onset, the mortality rate of untreated AAD increases 1% to 2%,with no difference based on age.3,4 Different reports have shown mortality rates between 7% and 30%.4

Effective imaging is crucial to the diagnosis and treatment of AAD, given the occurrence of atypical presentation, missed diagnosis, and high mortality rate.4 A chest radiograph will show a widened mediastinum, but the preferred diagnostic tests are a CT or transthoracic echocardiogram.2,4 Once the diagnosis of AAD is confirmed, an aortic angiogram is the preferred test to determine the extent of the dissection prior to surgical treatment.2

Continue to: Classification dictates treatment

Classification dictates treatment. AAD is classified based on where the dissection of the aorta occurs. If the dissection involves the ascending aorta, it is classified as a type A AAD and should immediately be treated with emergent surgery in order to prevent complications including myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade, and aortic rupture.2,4,5 If the dissection is limited to the descending aorta, it is classified as a type B AAD and can be medically managed by controlling pain and lowering blood pressure; if symptoms persist, surgical management may be required.2 After hospital discharge, AAD patients are followed closely with medical therapy, serial imaging, and reoperation if necessary.4

Our patient underwent emergent surgery for aortic root/ascending aortic replacement with a mechanical valve. He tolerated the procedure well. Surgical tissue pathology of the aortic segment showed a wall of elastic vessel with medial degeneration and dissection, and the tissue pathology of the aorta leaflets showed valvular tissue with myxoid degeneration.

THE TAKEAWAY

It is critical to keep AAD in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with acute onset of chest pain, as AAD often has an atypical presentation and can easily be misdiagnosed. Effective imaging is crucial to diagnosis, and immediate treatment is essential to patient survival.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rachel A. Reedy, PA, University of Florida, Department of General Pediatrics, 7046 SW Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32608; [email protected]

1. Pineault J, Ouimet D, Pichette V, Vallée M. A case of aortic dissection in a young adult: a refresher of the literature of this “great masquerader.” Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:889-893.

2. Agabegi SS, Agabegi ElD, Ring AC. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In: Jackson A, ed. Step-up to Medicine. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:54-55.

3. Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, et al. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665-669.

4. Tsai TT, Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:149-159.

5. Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, et al. Role of age in acute type A aortic dissection outcome: Report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:784-789.

1. Pineault J, Ouimet D, Pichette V, Vallée M. A case of aortic dissection in a young adult: a refresher of the literature of this “great masquerader.” Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:889-893.

2. Agabegi SS, Agabegi ElD, Ring AC. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In: Jackson A, ed. Step-up to Medicine. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:54-55.

3. Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, et al. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665-669.

4. Tsai TT, Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:149-159.

5. Trimarchi S, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, et al. Role of age in acute type A aortic dissection outcome: Report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:784-789.

Can viscous fiber lower glycemic markers in type 2 diabetes?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 57-year-old man who was given a diagnosis of T2D a year ago presents for an office visit. His hemoglobin A1C level at diagnosis was 8.3%. He is otherwise healthy and has been adhering well to a plan of metformin 1000 mg twice daily, regular exercise, and a low-carbohydrate diet you recommended. His most recent hemoglobin A1C is 7.3%. He is pleased with his progress, so he is discouraged when you tell him that he is not yet at goal. He asks if there are other things that he can do to further lower his hemoglobin A1C. What can you recommend for him?

According to the National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 34.1 million US adults ≥ 18 years of age (13% of the adult population) have diabetes, 50% of whom have a hemoglobin A1C > 7%. The report also states that approximately 88 million US adults—more than one-third of the population—have prediabetes.2

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) estimated that diabetes-related health care costs in the United States for 2017 totaled $237 billion, an increase of 26% from 2012. More than $30 billion of this expense comes directly from diabetes medications; the remainder of these costs are related to lost wages, clinic visits, hospitalizations, and treatment for diabetic complications and comorbidities. After controlling for age and gender, medical expenditures for people with diabetes are 2.3 times higher than for those without diabetes.3

The 2019

STUDY SUMMARY

Effect on A1C exceeded the FDA threshold for new drugs

This systematic review and meta-analysis searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify randomized controlled trials that studied the effects of viscous fiber supplementation on glycemic control in patients with T2D. Eligible studies included those that: (1) had a duration ≥ 3 weeks; (2) allowed isolation of the viscous fiber effects; and (3) reported at least 1 of the following glycemic measures: hemoglobin A1C (n = 1148 patients), fasting glucose (n = 1394), fasting insulin (n = 228),

Data were pooled using the generic inverse variance method and expressed as mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed and quantified (Cochran Q and I2 statistics, respectively). I2 ≥ 50% indicates substantial heterogeneity. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to evaluate the overall strength of evidence.

Twenty-eight eligible studies were compared. The median age of included patients was 60 years. The median dose of viscous fiber was 13.1 g/d (range, 2.55-21). Viscous fiber type varied between the studies and included psyllium, guar gum, β-glucan, and konjac, and was consumed in powder, tablet, capsule, and limited food-based forms (in 1 of the included studies). The median trial duration was 8 weeks, with 11 trials lasting ≥ 12 weeks.

Continue to: The study found...

The study found moderate-grade evidence that, when added to standard of care, viscous fiber supplementation reduced hemoglobin A1C (MD = –0.58%; 95% CI, –0.88 to –0.28; P = .0002; I2 = 91%), fasting glucose (MD = –14.8 mg/dL; 95% CI, –23.8 to –5.58; P = .001; I2 = 92%), and HOMA-IR (MD = –1.89; 95% CI, –3.45 to –0.33; P = .02; I2 = 94%) compared with control. The effect on hemoglobin A1C exceeds the ≥ 0.3% threshold established by the US Food and Drug Administration for new antihyperglycemic drug development. There was no significant effect on fasting insulin or fructosamine, although the sample size for fructosamine was small. No significant evidence of a dose-dependent response effect was found. The studies had substantial heterogeneity. No evaluation of potential or real harm was noted in the analysis.

WHAT’S NEW

Potential glycemic benefit without large dietary increase

The glucose-lowering effects of increased fiber intake have often been hypothesized, but this meta-analysis is the first to focus specifically on the effect of viscous fiber supplements in patients with T2D. Prior meta-analyses, including those cited in the 2019 ADA recommendations mentioned above, included primarily whole-food dietary sources of fiber in the treatment arms and generally had more modest effects on outcomes.4,6,7

By focusing on viscous fiber supplements, this study isolated the effect of these supplements vs fiber-rich dietary changes. It illustrates a greater potential benefit with supplements than whole-food dietary sources of fiber, and at a lower dose of fiber than was seen in prior studies without requiring substantial increases in caloric intake. Viscous fiber supplementation is a potential adjunct to the usual evidence-based standards of care for glycemic control in patients with T2D.

CAVEATS

Limited study durations may raise uncertainty about long-term benefits

This meta-analysis does have its limitations. The heterogeneity among the studies analyzed makes it difficult to establish a single recommendation regarding dose, type, and brand of fiber to be used. Only 11 of the 28 studies lasted longer than 12 weeks, with a median duration of 8 weeks, making any long-term effects on hemoglobin A1C unknown. No adverse effects or reactions were described to evaluate safety and tolerability of the viscous fiber supplementation. No patient-oriented outcomes were reported.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Patients may not be eager to supplement with viscous fiber

The biggest challenge to implementation is patient compliance. Some forms of supplemental fiber are less palatable than others and may cause unpleasant gastrointestinal adverse effects, which may be an impediment for some patients. Cost may also be an issue for some patients. Diabetes medications can be expensive; however, they are often covered, at least partially, by medical insurance. Over-the-counter supplements are unlikely to be covered for most patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Jovanovski E, Khayyat R, Zurbau A, et al. Should viscous fiber supplements be considered in diabetes control? Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled tria ls. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:755-766. Published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1604.

2. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2020.

3. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:917-928.

4. Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:731-754.

5. American Diabetes Association. 5. Lifestyle management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S46-S60.

6. Post RE, Mainous AG III, King DE, et al. Dietary fiber for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:16-23.

7. Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Augustin LSA, et al. Effect of legumes as part of a low glycemic index diet on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1653-1660.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 57-year-old man who was given a diagnosis of T2D a year ago presents for an office visit. His hemoglobin A1C level at diagnosis was 8.3%. He is otherwise healthy and has been adhering well to a plan of metformin 1000 mg twice daily, regular exercise, and a low-carbohydrate diet you recommended. His most recent hemoglobin A1C is 7.3%. He is pleased with his progress, so he is discouraged when you tell him that he is not yet at goal. He asks if there are other things that he can do to further lower his hemoglobin A1C. What can you recommend for him?

According to the National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 34.1 million US adults ≥ 18 years of age (13% of the adult population) have diabetes, 50% of whom have a hemoglobin A1C > 7%. The report also states that approximately 88 million US adults—more than one-third of the population—have prediabetes.2

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) estimated that diabetes-related health care costs in the United States for 2017 totaled $237 billion, an increase of 26% from 2012. More than $30 billion of this expense comes directly from diabetes medications; the remainder of these costs are related to lost wages, clinic visits, hospitalizations, and treatment for diabetic complications and comorbidities. After controlling for age and gender, medical expenditures for people with diabetes are 2.3 times higher than for those without diabetes.3

The 2019

STUDY SUMMARY

Effect on A1C exceeded the FDA threshold for new drugs