User login

You and the skeptical patient: Who’s the doctor here?

“I spoke to him on many occasions about the dangers of COVID, but he just didn’t believe me,” said Dr. Hood, an internist in Lexington, Ky. “He just didn’t give me enough time to help him. He waited to let me know he was ill with COVID and took days to pick up the medicine. Unfortunately, he then passed away.”

The rise of the skeptical patient

It can be extremely frustrating for doctors when patients question or disbelieve their physician’s medical advice and explanations. And many physicians resent the amount of time they spend trying to explain or make their case, especially during a busy day. But patients’ skepticism about the validity of some treatments seems to be increasing.

“Patients are now more likely to have their own medical explanation for their complaint than they used to, and that can be bad for their health,” Dr. Hood said.

Dr. Hood sees medical cynicism as part of Americans’ growing distrust of experts, leveraged by easy access to the internet. “When people Google, they tend to look for support of their opinions, rather than arrive at a fully educated decision.”

Only about half of patients believe their physicians “provide fair and accurate treatment information all or most of the time,” according to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center.

Patients’ distrust has become more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, said John Schumann, MD, an internist with Oak Street Health, a practice with more than 500 physicians and other providers in 20 states, treating almost exclusively Medicare patients.

“The skeptics became more entrenched during the pandemic,” said Dr. Schumann, who is based in Tulsa, Okla. “They may think the COVID vaccines were approved too quickly, or believe the pandemic itself is a hoax.”

“There’s a lot of antiscience rhetoric now,” Dr. Schumann added. “I’d say about half of my patients are comfortable with science-based decisions and the other half are not.”

What are patients mistrustful about?

Patients’ suspicions of certain therapies began long before the pandemic. In dermatology, for example, some patients refuse to take topical steroids, said Steven R. Feldman, MD, a dermatologist in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“Their distrust is usually based on anecdotal stories they read about,” he noted. “Patients in other specialties are dead set against vaccinations.”

In addition to refusing treatments and inoculations, some patients ask for questionable regimens mentioned in the news. “Some patients have demanded hydroxychloroquine or Noromectin, drugs that are unproven in the treatment of COVID,” Dr. Schumann said. “We refuse to prescribe them.”

Dr. Hood said patients’ reluctance to follow medical advice can often be based on cost. “I have a patient who was more willing to save $20 than to save his life. But when the progression of his test results fit my predictions, he became more willing to take treatments. I had to wait for the opportune moment to convince him.”

Many naysayer patients keep their views to themselves, and physicians may be unaware that the patients are stonewalling. A 2006 study estimated that about 10%-16% of primary care patients actively resist medical authority.

Dr. Schumann cited patients who don’t want to hear an upsetting diagnosis. “Some patients might refuse to take a biopsy to see if they have cancer because they don’t want to know,” he said. “In many cases, they simply won’t get the biopsy and won’t tell the doctor that they didn’t.”

Sometimes skeptics’ arguments have merit

Some patients’ concerns can be valid, such as when they refuse to go on statins, said Zain Hakeem, DO, a physician in Austin, Tex.

“In some cases, I feel that statins are not necessary,” he said. “The science on statins for primary prevention is not strong, although they should be used for exceedingly high-risk patients.”

Certain patients, especially those with chronic conditions, do a great deal of research, using legitimate sources on the Web, and their research is well supported.

However, these patients can be overconfident in their conclusions. Several studies have shown that with just a little experience, people can replace beginners’ caution with a false sense of competence.

For example, “Patients may not weigh the risks correctly,” Dr. Hakeem said. “They can be more concerned about the risk of having their colon perforated during a colonoscopy, while the risk of cancer if they don’t have a colonoscopy is much higher.”

Some highly successful people may be more likely to trust their own medical instincts. When Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003, he put off surgery for 9 months while he tried to cure his disease with a vegan diet, acupuncture, herbs, bowel cleansings, and other remedies he read about. He died in 2011. Some experts believe that delay hastened his death.

Of course, not all physicians’ diagnoses or treatments are correct. One study indicated doctors’ diagnostic error rate could be as high as 15%. And just as patients can be overconfident in their conclusions, so can doctors. Another study found that physicians’ stated confidence in their diagnosis was only slightly affected by the inaccuracy of that diagnosis or the difficulty of the case.

Best ways to deal with cynical patients

Patients’ skepticism can frustrate doctors, reduce the efficiency of care delivery, and interfere with recovery. What can doctors do to deal with these problems?

1. Build the patient’s trust in you. “Getting patients to adhere to your advice involves making sure they feel they have a caring doctor whom they trust,” Dr. Feldman said.

“I want to show patients that I am entirely focused on them,” he added. “For example, I may rush to the door of the exam room from my last appointment, but I open the door very slowly and deliberately, because I want the patient to see that I won’t hurry with them.”

2. Spend time with the patient. Familiarity builds trust. Dr. Schumann said doctors at Oak Street Health see their patients an average of six to eight times a year, an unusually high number. “The more patients see their physicians, the more likely they are to trust them.”

3. Keep up to date. “I make sure I’m up to date with the literature, and I try to present a truthful message,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, my research showed that inflammation played a strong role in developing complications from COVID, so I wrote a detailed treatment protocol aimed at the inflammation and the immune response, which has been very effective.”

4. Confront patients tactfully. Patients who do research on the Web don’t want to be scolded, Dr. Feldman said. In fact, he praises them, even if he doesn’t agree with their findings. “I might say: ‘What a relief to finally find patients who’ve taken the time to educate themselves before coming here.’ ”

Dr. Feldman is careful not to dispute patients’ conclusions. “Debating the issues is not an effective approach to get patients to trust you. The last thing you want to tell a patient is: ‘Listen to me! I’m an expert.’ People just dig in.”

However, it does help to give patients feedback. “I’m a big fan of patients arguing with me,” Dr. Hakeem said. “It means you can straighten out misunderstandings and improve decision-making.”

5. Explain your reasoning. “You need to communicate clearly and show them your thinking,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, I’ll explain why a patient has a strong risk for heart attack.”

6. Acknowledge uncertainties. “The doctor may present the science as far more certain than it is,” Dr. Hakeem said. “If you don’t acknowledge the uncertainties, you could break the patient’s trust in you.”

7. Don’t use a lot of numbers. “Data is not a good tool to convince patients,” Dr. Feldman said. “The human brain isn’t designed to work that way.”

If you want to use numbers to show clinical risk, Dr. Hakeem advisd using natural frequencies, such as 10 out of 10,000, which is less confusing to the patient than the equivalent percentage of 0.1%.

It can be helpful to refer to familiar concepts. One way to understand a risk is to compare it with risks in daily life, such as the dangers of driving or falling in the shower, Dr. Hakeem added.

Dr. Feldman often refers to another person’s experience when presenting his medical advice. “I might say to the patient: ‘You remind me of another patient I had. They were sitting in the same chair you’re sitting in. They did really well on this drug, and I think it’s probably the best choice for you, too.’ ”

8. Adopt shared decision-making. This approach involves empowering the patient to become an equal partner in medical decisions. The patient is given information through portals and is encouraged to do research. Critics, however, say that most patients don’t want this degree of empowerment and would rather depend on the doctor’s advice.

Conclusion

It’s often impossible to get through to a skeptical patient, which can be disheartening for doctors. “Physicians want to do what is best for the patient, so when the patient doesn’t listen, they may take it personally,” Dr. Hood said. “But you always have to remember, the patient is the one with disease, and it’s up to the patient to open the door.”

Still, some skeptical patients ultimately change their minds. Dr. Schumann said patients who initially declined the COVID vaccine eventually decided to get it. “It often took them more than a year. but it’s never too late.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I spoke to him on many occasions about the dangers of COVID, but he just didn’t believe me,” said Dr. Hood, an internist in Lexington, Ky. “He just didn’t give me enough time to help him. He waited to let me know he was ill with COVID and took days to pick up the medicine. Unfortunately, he then passed away.”

The rise of the skeptical patient

It can be extremely frustrating for doctors when patients question or disbelieve their physician’s medical advice and explanations. And many physicians resent the amount of time they spend trying to explain or make their case, especially during a busy day. But patients’ skepticism about the validity of some treatments seems to be increasing.

“Patients are now more likely to have their own medical explanation for their complaint than they used to, and that can be bad for their health,” Dr. Hood said.

Dr. Hood sees medical cynicism as part of Americans’ growing distrust of experts, leveraged by easy access to the internet. “When people Google, they tend to look for support of their opinions, rather than arrive at a fully educated decision.”

Only about half of patients believe their physicians “provide fair and accurate treatment information all or most of the time,” according to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center.

Patients’ distrust has become more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, said John Schumann, MD, an internist with Oak Street Health, a practice with more than 500 physicians and other providers in 20 states, treating almost exclusively Medicare patients.

“The skeptics became more entrenched during the pandemic,” said Dr. Schumann, who is based in Tulsa, Okla. “They may think the COVID vaccines were approved too quickly, or believe the pandemic itself is a hoax.”

“There’s a lot of antiscience rhetoric now,” Dr. Schumann added. “I’d say about half of my patients are comfortable with science-based decisions and the other half are not.”

What are patients mistrustful about?

Patients’ suspicions of certain therapies began long before the pandemic. In dermatology, for example, some patients refuse to take topical steroids, said Steven R. Feldman, MD, a dermatologist in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“Their distrust is usually based on anecdotal stories they read about,” he noted. “Patients in other specialties are dead set against vaccinations.”

In addition to refusing treatments and inoculations, some patients ask for questionable regimens mentioned in the news. “Some patients have demanded hydroxychloroquine or Noromectin, drugs that are unproven in the treatment of COVID,” Dr. Schumann said. “We refuse to prescribe them.”

Dr. Hood said patients’ reluctance to follow medical advice can often be based on cost. “I have a patient who was more willing to save $20 than to save his life. But when the progression of his test results fit my predictions, he became more willing to take treatments. I had to wait for the opportune moment to convince him.”

Many naysayer patients keep their views to themselves, and physicians may be unaware that the patients are stonewalling. A 2006 study estimated that about 10%-16% of primary care patients actively resist medical authority.

Dr. Schumann cited patients who don’t want to hear an upsetting diagnosis. “Some patients might refuse to take a biopsy to see if they have cancer because they don’t want to know,” he said. “In many cases, they simply won’t get the biopsy and won’t tell the doctor that they didn’t.”

Sometimes skeptics’ arguments have merit

Some patients’ concerns can be valid, such as when they refuse to go on statins, said Zain Hakeem, DO, a physician in Austin, Tex.

“In some cases, I feel that statins are not necessary,” he said. “The science on statins for primary prevention is not strong, although they should be used for exceedingly high-risk patients.”

Certain patients, especially those with chronic conditions, do a great deal of research, using legitimate sources on the Web, and their research is well supported.

However, these patients can be overconfident in their conclusions. Several studies have shown that with just a little experience, people can replace beginners’ caution with a false sense of competence.

For example, “Patients may not weigh the risks correctly,” Dr. Hakeem said. “They can be more concerned about the risk of having their colon perforated during a colonoscopy, while the risk of cancer if they don’t have a colonoscopy is much higher.”

Some highly successful people may be more likely to trust their own medical instincts. When Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003, he put off surgery for 9 months while he tried to cure his disease with a vegan diet, acupuncture, herbs, bowel cleansings, and other remedies he read about. He died in 2011. Some experts believe that delay hastened his death.

Of course, not all physicians’ diagnoses or treatments are correct. One study indicated doctors’ diagnostic error rate could be as high as 15%. And just as patients can be overconfident in their conclusions, so can doctors. Another study found that physicians’ stated confidence in their diagnosis was only slightly affected by the inaccuracy of that diagnosis or the difficulty of the case.

Best ways to deal with cynical patients

Patients’ skepticism can frustrate doctors, reduce the efficiency of care delivery, and interfere with recovery. What can doctors do to deal with these problems?

1. Build the patient’s trust in you. “Getting patients to adhere to your advice involves making sure they feel they have a caring doctor whom they trust,” Dr. Feldman said.

“I want to show patients that I am entirely focused on them,” he added. “For example, I may rush to the door of the exam room from my last appointment, but I open the door very slowly and deliberately, because I want the patient to see that I won’t hurry with them.”

2. Spend time with the patient. Familiarity builds trust. Dr. Schumann said doctors at Oak Street Health see their patients an average of six to eight times a year, an unusually high number. “The more patients see their physicians, the more likely they are to trust them.”

3. Keep up to date. “I make sure I’m up to date with the literature, and I try to present a truthful message,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, my research showed that inflammation played a strong role in developing complications from COVID, so I wrote a detailed treatment protocol aimed at the inflammation and the immune response, which has been very effective.”

4. Confront patients tactfully. Patients who do research on the Web don’t want to be scolded, Dr. Feldman said. In fact, he praises them, even if he doesn’t agree with their findings. “I might say: ‘What a relief to finally find patients who’ve taken the time to educate themselves before coming here.’ ”

Dr. Feldman is careful not to dispute patients’ conclusions. “Debating the issues is not an effective approach to get patients to trust you. The last thing you want to tell a patient is: ‘Listen to me! I’m an expert.’ People just dig in.”

However, it does help to give patients feedback. “I’m a big fan of patients arguing with me,” Dr. Hakeem said. “It means you can straighten out misunderstandings and improve decision-making.”

5. Explain your reasoning. “You need to communicate clearly and show them your thinking,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, I’ll explain why a patient has a strong risk for heart attack.”

6. Acknowledge uncertainties. “The doctor may present the science as far more certain than it is,” Dr. Hakeem said. “If you don’t acknowledge the uncertainties, you could break the patient’s trust in you.”

7. Don’t use a lot of numbers. “Data is not a good tool to convince patients,” Dr. Feldman said. “The human brain isn’t designed to work that way.”

If you want to use numbers to show clinical risk, Dr. Hakeem advisd using natural frequencies, such as 10 out of 10,000, which is less confusing to the patient than the equivalent percentage of 0.1%.

It can be helpful to refer to familiar concepts. One way to understand a risk is to compare it with risks in daily life, such as the dangers of driving or falling in the shower, Dr. Hakeem added.

Dr. Feldman often refers to another person’s experience when presenting his medical advice. “I might say to the patient: ‘You remind me of another patient I had. They were sitting in the same chair you’re sitting in. They did really well on this drug, and I think it’s probably the best choice for you, too.’ ”

8. Adopt shared decision-making. This approach involves empowering the patient to become an equal partner in medical decisions. The patient is given information through portals and is encouraged to do research. Critics, however, say that most patients don’t want this degree of empowerment and would rather depend on the doctor’s advice.

Conclusion

It’s often impossible to get through to a skeptical patient, which can be disheartening for doctors. “Physicians want to do what is best for the patient, so when the patient doesn’t listen, they may take it personally,” Dr. Hood said. “But you always have to remember, the patient is the one with disease, and it’s up to the patient to open the door.”

Still, some skeptical patients ultimately change their minds. Dr. Schumann said patients who initially declined the COVID vaccine eventually decided to get it. “It often took them more than a year. but it’s never too late.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I spoke to him on many occasions about the dangers of COVID, but he just didn’t believe me,” said Dr. Hood, an internist in Lexington, Ky. “He just didn’t give me enough time to help him. He waited to let me know he was ill with COVID and took days to pick up the medicine. Unfortunately, he then passed away.”

The rise of the skeptical patient

It can be extremely frustrating for doctors when patients question or disbelieve their physician’s medical advice and explanations. And many physicians resent the amount of time they spend trying to explain or make their case, especially during a busy day. But patients’ skepticism about the validity of some treatments seems to be increasing.

“Patients are now more likely to have their own medical explanation for their complaint than they used to, and that can be bad for their health,” Dr. Hood said.

Dr. Hood sees medical cynicism as part of Americans’ growing distrust of experts, leveraged by easy access to the internet. “When people Google, they tend to look for support of their opinions, rather than arrive at a fully educated decision.”

Only about half of patients believe their physicians “provide fair and accurate treatment information all or most of the time,” according to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center.

Patients’ distrust has become more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, said John Schumann, MD, an internist with Oak Street Health, a practice with more than 500 physicians and other providers in 20 states, treating almost exclusively Medicare patients.

“The skeptics became more entrenched during the pandemic,” said Dr. Schumann, who is based in Tulsa, Okla. “They may think the COVID vaccines were approved too quickly, or believe the pandemic itself is a hoax.”

“There’s a lot of antiscience rhetoric now,” Dr. Schumann added. “I’d say about half of my patients are comfortable with science-based decisions and the other half are not.”

What are patients mistrustful about?

Patients’ suspicions of certain therapies began long before the pandemic. In dermatology, for example, some patients refuse to take topical steroids, said Steven R. Feldman, MD, a dermatologist in Winston-Salem, N.C.

“Their distrust is usually based on anecdotal stories they read about,” he noted. “Patients in other specialties are dead set against vaccinations.”

In addition to refusing treatments and inoculations, some patients ask for questionable regimens mentioned in the news. “Some patients have demanded hydroxychloroquine or Noromectin, drugs that are unproven in the treatment of COVID,” Dr. Schumann said. “We refuse to prescribe them.”

Dr. Hood said patients’ reluctance to follow medical advice can often be based on cost. “I have a patient who was more willing to save $20 than to save his life. But when the progression of his test results fit my predictions, he became more willing to take treatments. I had to wait for the opportune moment to convince him.”

Many naysayer patients keep their views to themselves, and physicians may be unaware that the patients are stonewalling. A 2006 study estimated that about 10%-16% of primary care patients actively resist medical authority.

Dr. Schumann cited patients who don’t want to hear an upsetting diagnosis. “Some patients might refuse to take a biopsy to see if they have cancer because they don’t want to know,” he said. “In many cases, they simply won’t get the biopsy and won’t tell the doctor that they didn’t.”

Sometimes skeptics’ arguments have merit

Some patients’ concerns can be valid, such as when they refuse to go on statins, said Zain Hakeem, DO, a physician in Austin, Tex.

“In some cases, I feel that statins are not necessary,” he said. “The science on statins for primary prevention is not strong, although they should be used for exceedingly high-risk patients.”

Certain patients, especially those with chronic conditions, do a great deal of research, using legitimate sources on the Web, and their research is well supported.

However, these patients can be overconfident in their conclusions. Several studies have shown that with just a little experience, people can replace beginners’ caution with a false sense of competence.

For example, “Patients may not weigh the risks correctly,” Dr. Hakeem said. “They can be more concerned about the risk of having their colon perforated during a colonoscopy, while the risk of cancer if they don’t have a colonoscopy is much higher.”

Some highly successful people may be more likely to trust their own medical instincts. When Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003, he put off surgery for 9 months while he tried to cure his disease with a vegan diet, acupuncture, herbs, bowel cleansings, and other remedies he read about. He died in 2011. Some experts believe that delay hastened his death.

Of course, not all physicians’ diagnoses or treatments are correct. One study indicated doctors’ diagnostic error rate could be as high as 15%. And just as patients can be overconfident in their conclusions, so can doctors. Another study found that physicians’ stated confidence in their diagnosis was only slightly affected by the inaccuracy of that diagnosis or the difficulty of the case.

Best ways to deal with cynical patients

Patients’ skepticism can frustrate doctors, reduce the efficiency of care delivery, and interfere with recovery. What can doctors do to deal with these problems?

1. Build the patient’s trust in you. “Getting patients to adhere to your advice involves making sure they feel they have a caring doctor whom they trust,” Dr. Feldman said.

“I want to show patients that I am entirely focused on them,” he added. “For example, I may rush to the door of the exam room from my last appointment, but I open the door very slowly and deliberately, because I want the patient to see that I won’t hurry with them.”

2. Spend time with the patient. Familiarity builds trust. Dr. Schumann said doctors at Oak Street Health see their patients an average of six to eight times a year, an unusually high number. “The more patients see their physicians, the more likely they are to trust them.”

3. Keep up to date. “I make sure I’m up to date with the literature, and I try to present a truthful message,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, my research showed that inflammation played a strong role in developing complications from COVID, so I wrote a detailed treatment protocol aimed at the inflammation and the immune response, which has been very effective.”

4. Confront patients tactfully. Patients who do research on the Web don’t want to be scolded, Dr. Feldman said. In fact, he praises them, even if he doesn’t agree with their findings. “I might say: ‘What a relief to finally find patients who’ve taken the time to educate themselves before coming here.’ ”

Dr. Feldman is careful not to dispute patients’ conclusions. “Debating the issues is not an effective approach to get patients to trust you. The last thing you want to tell a patient is: ‘Listen to me! I’m an expert.’ People just dig in.”

However, it does help to give patients feedback. “I’m a big fan of patients arguing with me,” Dr. Hakeem said. “It means you can straighten out misunderstandings and improve decision-making.”

5. Explain your reasoning. “You need to communicate clearly and show them your thinking,” Dr. Hood said. “For instance, I’ll explain why a patient has a strong risk for heart attack.”

6. Acknowledge uncertainties. “The doctor may present the science as far more certain than it is,” Dr. Hakeem said. “If you don’t acknowledge the uncertainties, you could break the patient’s trust in you.”

7. Don’t use a lot of numbers. “Data is not a good tool to convince patients,” Dr. Feldman said. “The human brain isn’t designed to work that way.”

If you want to use numbers to show clinical risk, Dr. Hakeem advisd using natural frequencies, such as 10 out of 10,000, which is less confusing to the patient than the equivalent percentage of 0.1%.

It can be helpful to refer to familiar concepts. One way to understand a risk is to compare it with risks in daily life, such as the dangers of driving or falling in the shower, Dr. Hakeem added.

Dr. Feldman often refers to another person’s experience when presenting his medical advice. “I might say to the patient: ‘You remind me of another patient I had. They were sitting in the same chair you’re sitting in. They did really well on this drug, and I think it’s probably the best choice for you, too.’ ”

8. Adopt shared decision-making. This approach involves empowering the patient to become an equal partner in medical decisions. The patient is given information through portals and is encouraged to do research. Critics, however, say that most patients don’t want this degree of empowerment and would rather depend on the doctor’s advice.

Conclusion

It’s often impossible to get through to a skeptical patient, which can be disheartening for doctors. “Physicians want to do what is best for the patient, so when the patient doesn’t listen, they may take it personally,” Dr. Hood said. “But you always have to remember, the patient is the one with disease, and it’s up to the patient to open the door.”

Still, some skeptical patients ultimately change their minds. Dr. Schumann said patients who initially declined the COVID vaccine eventually decided to get it. “It often took them more than a year. but it’s never too late.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sepsis transition program may lower mortality in patients discharged to post-acute care

Sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care facilities are at high risk for mortality and hospital readmission, according to Nicholas Colucciello, MD, and few interventions have been shown to reduce these adverse outcomes.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues compared the effects of a Sepsis Transition And Recovery (STAR) program versus Usual Care (UC) alone on 30-day mortality and hospital readmission among sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), Dr. Colucciello, a primary care physician in Toledo, Ohio, presented data suggesting that

Study of IMPACTS

The study was a secondary analysis of patients from the IMPACTS (Improving Morbidity During Post-Acute Care Transitions for Sepsis) randomized clinical trial, focusing only on those patients who were discharged to a post-acute care facility. IMPACTS evaluated the effectiveness of STAR, a post-sepsis transition program using nurse navigators to deliver best-practice post-sepsis care during and after hospitalization, Dr. Colucciello said. The interventions included comorbidity monitoring, medication review, evaluation for new impairments/symptoms, and goals of care assessment.

“Over one-third of sepsis survivors are discharged to post-acute care as they are not stable enough to go home,” said Dr. Colucciello, and among these patients there is a high risk for mortality and hospital readmission.

Dr. Colucciello and his colleagues randomly assigned patients hospitalized with sepsis and deemed high risk for post-discharge readmission or mortality to either STAR or usual care. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day readmission and mortality, which was assessed from the electronic health record and social security death master file.

Of the 175 (21%) IMPACTS patients discharged to post-acute care facilities, 143 (82%) were sent to skilled nursing facilities, and 12 (7%) were sent to long-term acute care hospitals. The remaining 20 patients (11%) were sent to inpatient rehabilitation. A total of 88 of these patients received the STAR intervention and 87 received usual care.

Suggestive results

The study showed that the composite primary endpoint occurred in 26 (30.6%) patients in the usual care group versus 18 (20.7%) patients in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –9.9% (95% CI, –22.9 to 3.1), according to Dr. Colucciello. As individual factors, 30-day all-cause mortality was 8.2% in the UC group, compared with 5.8% in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –2.5% (95% CI, –10.1 to 5.0) and the 30-day all-cause readmission was 27.1% in the UC group, compared with 17.2% in the STAR program, for a risk difference of –9.8% (95% CI, –22.2 to 2.5). On average, patients receiving UC experienced 26.5 hospital-free days, compared with 27.4 hospital-free days in the STAR group, he added.

The biggest limitation of the study was the fact that it was underpowered to detect statistically significant differences, despite the suggestive results, said Dr. Colucciello. However, he added: “This secondary analysis of the IMPACTS randomized trial found that the STAR intervention may decrease 30-day mortality and readmission rates among sepsis patients discharged to a post-acute care facility,” he concluded.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care facilities are at high risk for mortality and hospital readmission, according to Nicholas Colucciello, MD, and few interventions have been shown to reduce these adverse outcomes.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues compared the effects of a Sepsis Transition And Recovery (STAR) program versus Usual Care (UC) alone on 30-day mortality and hospital readmission among sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), Dr. Colucciello, a primary care physician in Toledo, Ohio, presented data suggesting that

Study of IMPACTS

The study was a secondary analysis of patients from the IMPACTS (Improving Morbidity During Post-Acute Care Transitions for Sepsis) randomized clinical trial, focusing only on those patients who were discharged to a post-acute care facility. IMPACTS evaluated the effectiveness of STAR, a post-sepsis transition program using nurse navigators to deliver best-practice post-sepsis care during and after hospitalization, Dr. Colucciello said. The interventions included comorbidity monitoring, medication review, evaluation for new impairments/symptoms, and goals of care assessment.

“Over one-third of sepsis survivors are discharged to post-acute care as they are not stable enough to go home,” said Dr. Colucciello, and among these patients there is a high risk for mortality and hospital readmission.

Dr. Colucciello and his colleagues randomly assigned patients hospitalized with sepsis and deemed high risk for post-discharge readmission or mortality to either STAR or usual care. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day readmission and mortality, which was assessed from the electronic health record and social security death master file.

Of the 175 (21%) IMPACTS patients discharged to post-acute care facilities, 143 (82%) were sent to skilled nursing facilities, and 12 (7%) were sent to long-term acute care hospitals. The remaining 20 patients (11%) were sent to inpatient rehabilitation. A total of 88 of these patients received the STAR intervention and 87 received usual care.

Suggestive results

The study showed that the composite primary endpoint occurred in 26 (30.6%) patients in the usual care group versus 18 (20.7%) patients in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –9.9% (95% CI, –22.9 to 3.1), according to Dr. Colucciello. As individual factors, 30-day all-cause mortality was 8.2% in the UC group, compared with 5.8% in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –2.5% (95% CI, –10.1 to 5.0) and the 30-day all-cause readmission was 27.1% in the UC group, compared with 17.2% in the STAR program, for a risk difference of –9.8% (95% CI, –22.2 to 2.5). On average, patients receiving UC experienced 26.5 hospital-free days, compared with 27.4 hospital-free days in the STAR group, he added.

The biggest limitation of the study was the fact that it was underpowered to detect statistically significant differences, despite the suggestive results, said Dr. Colucciello. However, he added: “This secondary analysis of the IMPACTS randomized trial found that the STAR intervention may decrease 30-day mortality and readmission rates among sepsis patients discharged to a post-acute care facility,” he concluded.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care facilities are at high risk for mortality and hospital readmission, according to Nicholas Colucciello, MD, and few interventions have been shown to reduce these adverse outcomes.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues compared the effects of a Sepsis Transition And Recovery (STAR) program versus Usual Care (UC) alone on 30-day mortality and hospital readmission among sepsis survivors discharged to post-acute care.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), Dr. Colucciello, a primary care physician in Toledo, Ohio, presented data suggesting that

Study of IMPACTS

The study was a secondary analysis of patients from the IMPACTS (Improving Morbidity During Post-Acute Care Transitions for Sepsis) randomized clinical trial, focusing only on those patients who were discharged to a post-acute care facility. IMPACTS evaluated the effectiveness of STAR, a post-sepsis transition program using nurse navigators to deliver best-practice post-sepsis care during and after hospitalization, Dr. Colucciello said. The interventions included comorbidity monitoring, medication review, evaluation for new impairments/symptoms, and goals of care assessment.

“Over one-third of sepsis survivors are discharged to post-acute care as they are not stable enough to go home,” said Dr. Colucciello, and among these patients there is a high risk for mortality and hospital readmission.

Dr. Colucciello and his colleagues randomly assigned patients hospitalized with sepsis and deemed high risk for post-discharge readmission or mortality to either STAR or usual care. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day readmission and mortality, which was assessed from the electronic health record and social security death master file.

Of the 175 (21%) IMPACTS patients discharged to post-acute care facilities, 143 (82%) were sent to skilled nursing facilities, and 12 (7%) were sent to long-term acute care hospitals. The remaining 20 patients (11%) were sent to inpatient rehabilitation. A total of 88 of these patients received the STAR intervention and 87 received usual care.

Suggestive results

The study showed that the composite primary endpoint occurred in 26 (30.6%) patients in the usual care group versus 18 (20.7%) patients in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –9.9% (95% CI, –22.9 to 3.1), according to Dr. Colucciello. As individual factors, 30-day all-cause mortality was 8.2% in the UC group, compared with 5.8% in the STAR group, for a risk difference of –2.5% (95% CI, –10.1 to 5.0) and the 30-day all-cause readmission was 27.1% in the UC group, compared with 17.2% in the STAR program, for a risk difference of –9.8% (95% CI, –22.2 to 2.5). On average, patients receiving UC experienced 26.5 hospital-free days, compared with 27.4 hospital-free days in the STAR group, he added.

The biggest limitation of the study was the fact that it was underpowered to detect statistically significant differences, despite the suggestive results, said Dr. Colucciello. However, he added: “This secondary analysis of the IMPACTS randomized trial found that the STAR intervention may decrease 30-day mortality and readmission rates among sepsis patients discharged to a post-acute care facility,” he concluded.

Dr. Colucciello and colleagues report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CHEST 2022

Sepsis predictor tool falls short in emergency setting

Use of a sepsis predictor made little difference in time to antibiotic administration for septic patients in the emergency department, based on data from more than 200 patients.

“One of the big problems with sepsis is the lack of current tools for early and accurate diagnoses,” said Daniel Burgin, MD, an internal medicine resident at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The EPIC Sepsis Model (ESM) was designed to help facilitate earlier detection of sepsis and speed time to the start of antibiotics, but its effectiveness has not been well studied, Dr. Burgin said.

In Dr. Burgin’s facility, the ESM is mainly driven by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and blood pressure and is calculated every 15 minutes; the system triggers a best-practice advisory if needed, with an alert that sepsis may be suspected.

To assess the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, Dr. Burgin and colleagues reviewed data from 226 adult patients who presented to a single emergency department between February 2019 and June 2019. All patients presented with at least two criteria for SIRS. An ESM threshold of 6 was designed to trigger a set of orders to guide providers on a treatment plan that included antibiotics.

The researchers compared times to the ordering and the administration of antibiotics for patients with ESM scores of 6 or higher vs. less than 6 within 6 hours of triage in the ED. A total of 109 patients (48.2%) received antibiotics in the ED. Of these, 71 (74.5%) had ESM less than 6 and 38 (40.6%) had ESM of 6 or higher. The times from triage to antibiotics ordered and administered was significantly less in patients with ESM of 6 or higher (90.5 minutes vs. 131.5 minutes; 136 minutes vs. 186 minutes, respectively; P = .011 for both).

A total of 188 patients were evaluated for infection, and 86 met Sepsis-2 criteria based on physician chart review. These patients were significantly more likely than those not meeting the Sepsis-2 criteria to receive antibiotics in the ED (76.7% vs. 22.8%; P <.001).

Another 21 patients met criteria for Sepsis-3 based on a physician panel. Although all 21 received antibiotics, 5 did not receive them within 6 hours of triage in the ED, Dr. Burgin said. The median times to ordering and administration of antibiotics for Sepsis-3 patients with an ESM of 6 or higher were –5 and 38.5 (interquartile range), respectively.

“We hope that the ESM would prompt providers to start the order [for antibiotics],” Dr. Burgin said in his presentation. However, the researchers found no consistent patterns, and in many cases the ESM alerts occurred after the orders had been initiated, he noted.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center; the implementation of the EPIC tool is hospital specific, said Dr. Burgin. However, the results suggest that he said.

“While this research proved useful in assessing the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, more research is needed to understand how to operationalize predictive analytics,” Dr. Burgin said of the study findings. “The goal is to find the balance between early identification of sepsis and timely antimicrobial therapy and the potential harm of overalerting treatment teams.”

The study was supported in part by Cytovale, a sepsis diagnostics company. Several coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Cytovale. Dr. Burgin reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of a sepsis predictor made little difference in time to antibiotic administration for septic patients in the emergency department, based on data from more than 200 patients.

“One of the big problems with sepsis is the lack of current tools for early and accurate diagnoses,” said Daniel Burgin, MD, an internal medicine resident at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The EPIC Sepsis Model (ESM) was designed to help facilitate earlier detection of sepsis and speed time to the start of antibiotics, but its effectiveness has not been well studied, Dr. Burgin said.

In Dr. Burgin’s facility, the ESM is mainly driven by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and blood pressure and is calculated every 15 minutes; the system triggers a best-practice advisory if needed, with an alert that sepsis may be suspected.

To assess the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, Dr. Burgin and colleagues reviewed data from 226 adult patients who presented to a single emergency department between February 2019 and June 2019. All patients presented with at least two criteria for SIRS. An ESM threshold of 6 was designed to trigger a set of orders to guide providers on a treatment plan that included antibiotics.

The researchers compared times to the ordering and the administration of antibiotics for patients with ESM scores of 6 or higher vs. less than 6 within 6 hours of triage in the ED. A total of 109 patients (48.2%) received antibiotics in the ED. Of these, 71 (74.5%) had ESM less than 6 and 38 (40.6%) had ESM of 6 or higher. The times from triage to antibiotics ordered and administered was significantly less in patients with ESM of 6 or higher (90.5 minutes vs. 131.5 minutes; 136 minutes vs. 186 minutes, respectively; P = .011 for both).

A total of 188 patients were evaluated for infection, and 86 met Sepsis-2 criteria based on physician chart review. These patients were significantly more likely than those not meeting the Sepsis-2 criteria to receive antibiotics in the ED (76.7% vs. 22.8%; P <.001).

Another 21 patients met criteria for Sepsis-3 based on a physician panel. Although all 21 received antibiotics, 5 did not receive them within 6 hours of triage in the ED, Dr. Burgin said. The median times to ordering and administration of antibiotics for Sepsis-3 patients with an ESM of 6 or higher were –5 and 38.5 (interquartile range), respectively.

“We hope that the ESM would prompt providers to start the order [for antibiotics],” Dr. Burgin said in his presentation. However, the researchers found no consistent patterns, and in many cases the ESM alerts occurred after the orders had been initiated, he noted.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center; the implementation of the EPIC tool is hospital specific, said Dr. Burgin. However, the results suggest that he said.

“While this research proved useful in assessing the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, more research is needed to understand how to operationalize predictive analytics,” Dr. Burgin said of the study findings. “The goal is to find the balance between early identification of sepsis and timely antimicrobial therapy and the potential harm of overalerting treatment teams.”

The study was supported in part by Cytovale, a sepsis diagnostics company. Several coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Cytovale. Dr. Burgin reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of a sepsis predictor made little difference in time to antibiotic administration for septic patients in the emergency department, based on data from more than 200 patients.

“One of the big problems with sepsis is the lack of current tools for early and accurate diagnoses,” said Daniel Burgin, MD, an internal medicine resident at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The EPIC Sepsis Model (ESM) was designed to help facilitate earlier detection of sepsis and speed time to the start of antibiotics, but its effectiveness has not been well studied, Dr. Burgin said.

In Dr. Burgin’s facility, the ESM is mainly driven by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and blood pressure and is calculated every 15 minutes; the system triggers a best-practice advisory if needed, with an alert that sepsis may be suspected.

To assess the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, Dr. Burgin and colleagues reviewed data from 226 adult patients who presented to a single emergency department between February 2019 and June 2019. All patients presented with at least two criteria for SIRS. An ESM threshold of 6 was designed to trigger a set of orders to guide providers on a treatment plan that included antibiotics.

The researchers compared times to the ordering and the administration of antibiotics for patients with ESM scores of 6 or higher vs. less than 6 within 6 hours of triage in the ED. A total of 109 patients (48.2%) received antibiotics in the ED. Of these, 71 (74.5%) had ESM less than 6 and 38 (40.6%) had ESM of 6 or higher. The times from triage to antibiotics ordered and administered was significantly less in patients with ESM of 6 or higher (90.5 minutes vs. 131.5 minutes; 136 minutes vs. 186 minutes, respectively; P = .011 for both).

A total of 188 patients were evaluated for infection, and 86 met Sepsis-2 criteria based on physician chart review. These patients were significantly more likely than those not meeting the Sepsis-2 criteria to receive antibiotics in the ED (76.7% vs. 22.8%; P <.001).

Another 21 patients met criteria for Sepsis-3 based on a physician panel. Although all 21 received antibiotics, 5 did not receive them within 6 hours of triage in the ED, Dr. Burgin said. The median times to ordering and administration of antibiotics for Sepsis-3 patients with an ESM of 6 or higher were –5 and 38.5 (interquartile range), respectively.

“We hope that the ESM would prompt providers to start the order [for antibiotics],” Dr. Burgin said in his presentation. However, the researchers found no consistent patterns, and in many cases the ESM alerts occurred after the orders had been initiated, he noted.

The study findings were limited by the use of data from a single center; the implementation of the EPIC tool is hospital specific, said Dr. Burgin. However, the results suggest that he said.

“While this research proved useful in assessing the impact of ESM on time to antibiotics, more research is needed to understand how to operationalize predictive analytics,” Dr. Burgin said of the study findings. “The goal is to find the balance between early identification of sepsis and timely antimicrobial therapy and the potential harm of overalerting treatment teams.”

The study was supported in part by Cytovale, a sepsis diagnostics company. Several coauthors disclosed financial relationships with Cytovale. Dr. Burgin reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CHEST 2022

Climate change: Commentary in four dermatology journals calls for emergency action

“moving beyond merely discussing skin-related impacts” and toward prioritizing both patient and planetary health.

Dermatologists must make emissions-saving changes in everyday practice, for instance, and the specialty must enlist key stakeholders in public health, nonprofits, and industry – that is, pharmaceutical and medical supply companies – in finding solutions to help mitigate and adapt to climate change, wrote Eva Rawlings Parker, MD, and Markus D. Boos, MD, PhD.

“We have an ethical imperative to act,” they wrote. “The time is now for dermatologists and our medical societies to collectively rise to meet this crisis.”

Their commentary was published online in the International Journal of Dermatology , Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, British Journal of Dermatology, and Pediatric Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Parker, assistant professor of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that she and Dr. Boos, associate professor in the division of dermatology and department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, were motivated to write the editorial upon finding that dermatology was not represented among more than 230 medical journals that published an editorial in September 2021 calling for emergency action to limit global warming and protect health. In addition to the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, the copublishing journals represented numerous specialties, from nursing and pediatrics, to cardiology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology.

The editorial was not published in any dermatology journals, Dr. Parker said. “It was incredibly disappointing for me along with many of my colleagues who advocate for climate action because we realized it was a missed opportunity for dermatology to align with other medical specialties and be on the forefront of leading climate action to protect health.”

‘A threat multiplier’

The impact of climate change on skin disease is “an incredibly important part of our conversation as dermatologists because many cutaneous diseases are climate sensitive and we’re often seeing the effects of climate change every day in our clinical practices,” Dr. Parker said.

In fact, the impact on skin disease needs to be explored much further through more robust research funding, so that dermatology can better understand not only the incidence and severity of climate-induced changes in skin diseases – including and beyond atopic dermatitis, acne, and psoriasis – but also the mechanisms and pathophysiology involved, she said.

However, the impacts are much broader, she and Dr. Boos, a pediatric dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, maintain in their commentary. “An essential concept to broker among dermatologists is that the impacts of climate change extend well beyond skin disease by also placing broad pressure” on infrastructure, the economy, financial markets, global supply chains, food and water insecurity, and more, they wrote, noting the deep inequities of climate change.

Climate change is a “threat multiplier for public health, equity, and health systems,” the commentary says. “The confluence of these climate-related pressures should sound alarm bells as they place enormous jeopardy on the practice of dermatology across all scales and regions.”

Health care is among the most carbon-intensive service sectors worldwide, contributing to almost 5% of greenhouse gas emissions globally, the commentary says. And nationally, of the estimated greenhouse gas emissions from the United States, the health care sector contributes 10%, Dr. Parker said in the interview, referring to a 2016 report.

In addition, according to a 2019 report, the United States is the top contributor to health care’s global climate footprint, contributing 27% of health care’s global emissions, Dr. Parker noted.

In their commentary, she and Dr. Boos wrote that individually and practice wide, dermatologists can impact decarbonization through measures such as virtual attendance at medical meetings and greater utilization of telehealth services. Reductions in carbon emissions were demonstrated for virtual isotretinoin follow-up visits in a recent study, and these savings could be extrapolated to other routine follow-up visits for conditions such as rosacea, monitoring of biologics in patients with well-controlled disease, and postoperative wound checks, they said.

But when it comes to measures such as significantly reducing packaging and waste and “curating supply chains to make them more sustainable,” it is medical societies that have the “larger voice and broader relationship with the pharmaceutical industry” and with medical supply manufacturers and distributors, Dr. Parker explained in the interview, noting the potential for reducing the extensive amount of packaging used for drug samples.

Dr. Parker cochairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, which was established several years ago, and Dr. Boos is a member of the group’s executive committee.

AAD actions

In its 2018 Position Statement on Climate and Health, the American Academy of Dermatology resolved to raise awareness of the effects of climate change on the skin and educate patients about this, and to “work with other medical societies in ongoing and future efforts to educate the public and mitigate the effects of climate change on global health.”

Asked about the commentary’s call for more collaboration with industry and other stakeholders – and the impact that organized dermatology can have on planetary health – Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the AAD, said in an email that the AAD is “first and foremost an organization focused on providing gold-standard educational resources for dermatologists.”

The academy recognizes that “there are many dermatologic consequences of climate change that will increasingly affect our patients and challenge our membership,” and it has provided education on climate change in forums such as articles, podcasts, and sessions at AAD meetings, said Dr. Kaufmann, clinical professor in the department of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Regarding collaboration with other societies, he said that the AAD’s “focus to date has been on how to provide our members with educational resources to understand and prepare for how climate change may impact their practices and the dermatologic health of their patients,” he said.

The AAD has also sought to address its own carbon footprint and improve sustainability of its operations, including taking steps to reduce plastic and paper waste at its educational events, and to eliminate plastic waste associated with mailing resources like its member magazine, Dr. Kaufmann noted.

And in keeping with the Academy pledge – also articulated in the 2018 position statement – to support and facilitate dermatologists’ efforts to decrease their carbon footprint “in a cost effective (or cost-saving) manner,” Dr. Kaufmann said that the AAD has been offering a program called My Green Doctor as a free benefit of membership.

‘Be part of the solution’

In an interview, Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said her practice did an audit of their surgical area and found ways to increase the use of paper-packaged gauze – and decrease use of gauze in hard plastic containers – and otherwise decrease the amount of disposables, all of which take “huge amounts of resources” to create.

In the process, “we found significant savings,” she said. “Little things can turn out, in the long run, to be big things.”

Asked about the commentary, Dr. Maloney, who is involved in the AAD’s climate change resource group, said “the message is that yes, we need to be aware of the diseases affected by climate change. But our greater imperative is to be part of the solution and not part of the problem as far as doing things that affect climate change.”

Organized dermatology needs to broaden its advocacy, she said. “I don’t want us to stop advocating for things for our patients, but I do want us to start advocating for the world ... If we don’t try to [mitigate] climate change, we won’t have patients to advocate for.”

Dr. Parker, an associate editor of The Journal of Climate Change and Health, and Dr. Boos declared no conflicts of interest and no funding source for their commentary. Dr. Maloney said she has no conflicts of interest.

“moving beyond merely discussing skin-related impacts” and toward prioritizing both patient and planetary health.

Dermatologists must make emissions-saving changes in everyday practice, for instance, and the specialty must enlist key stakeholders in public health, nonprofits, and industry – that is, pharmaceutical and medical supply companies – in finding solutions to help mitigate and adapt to climate change, wrote Eva Rawlings Parker, MD, and Markus D. Boos, MD, PhD.

“We have an ethical imperative to act,” they wrote. “The time is now for dermatologists and our medical societies to collectively rise to meet this crisis.”

Their commentary was published online in the International Journal of Dermatology , Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, British Journal of Dermatology, and Pediatric Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Parker, assistant professor of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that she and Dr. Boos, associate professor in the division of dermatology and department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, were motivated to write the editorial upon finding that dermatology was not represented among more than 230 medical journals that published an editorial in September 2021 calling for emergency action to limit global warming and protect health. In addition to the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, the copublishing journals represented numerous specialties, from nursing and pediatrics, to cardiology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology.

The editorial was not published in any dermatology journals, Dr. Parker said. “It was incredibly disappointing for me along with many of my colleagues who advocate for climate action because we realized it was a missed opportunity for dermatology to align with other medical specialties and be on the forefront of leading climate action to protect health.”

‘A threat multiplier’

The impact of climate change on skin disease is “an incredibly important part of our conversation as dermatologists because many cutaneous diseases are climate sensitive and we’re often seeing the effects of climate change every day in our clinical practices,” Dr. Parker said.

In fact, the impact on skin disease needs to be explored much further through more robust research funding, so that dermatology can better understand not only the incidence and severity of climate-induced changes in skin diseases – including and beyond atopic dermatitis, acne, and psoriasis – but also the mechanisms and pathophysiology involved, she said.

However, the impacts are much broader, she and Dr. Boos, a pediatric dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, maintain in their commentary. “An essential concept to broker among dermatologists is that the impacts of climate change extend well beyond skin disease by also placing broad pressure” on infrastructure, the economy, financial markets, global supply chains, food and water insecurity, and more, they wrote, noting the deep inequities of climate change.

Climate change is a “threat multiplier for public health, equity, and health systems,” the commentary says. “The confluence of these climate-related pressures should sound alarm bells as they place enormous jeopardy on the practice of dermatology across all scales and regions.”

Health care is among the most carbon-intensive service sectors worldwide, contributing to almost 5% of greenhouse gas emissions globally, the commentary says. And nationally, of the estimated greenhouse gas emissions from the United States, the health care sector contributes 10%, Dr. Parker said in the interview, referring to a 2016 report.

In addition, according to a 2019 report, the United States is the top contributor to health care’s global climate footprint, contributing 27% of health care’s global emissions, Dr. Parker noted.

In their commentary, she and Dr. Boos wrote that individually and practice wide, dermatologists can impact decarbonization through measures such as virtual attendance at medical meetings and greater utilization of telehealth services. Reductions in carbon emissions were demonstrated for virtual isotretinoin follow-up visits in a recent study, and these savings could be extrapolated to other routine follow-up visits for conditions such as rosacea, monitoring of biologics in patients with well-controlled disease, and postoperative wound checks, they said.

But when it comes to measures such as significantly reducing packaging and waste and “curating supply chains to make them more sustainable,” it is medical societies that have the “larger voice and broader relationship with the pharmaceutical industry” and with medical supply manufacturers and distributors, Dr. Parker explained in the interview, noting the potential for reducing the extensive amount of packaging used for drug samples.

Dr. Parker cochairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, which was established several years ago, and Dr. Boos is a member of the group’s executive committee.

AAD actions

In its 2018 Position Statement on Climate and Health, the American Academy of Dermatology resolved to raise awareness of the effects of climate change on the skin and educate patients about this, and to “work with other medical societies in ongoing and future efforts to educate the public and mitigate the effects of climate change on global health.”

Asked about the commentary’s call for more collaboration with industry and other stakeholders – and the impact that organized dermatology can have on planetary health – Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the AAD, said in an email that the AAD is “first and foremost an organization focused on providing gold-standard educational resources for dermatologists.”

The academy recognizes that “there are many dermatologic consequences of climate change that will increasingly affect our patients and challenge our membership,” and it has provided education on climate change in forums such as articles, podcasts, and sessions at AAD meetings, said Dr. Kaufmann, clinical professor in the department of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Regarding collaboration with other societies, he said that the AAD’s “focus to date has been on how to provide our members with educational resources to understand and prepare for how climate change may impact their practices and the dermatologic health of their patients,” he said.

The AAD has also sought to address its own carbon footprint and improve sustainability of its operations, including taking steps to reduce plastic and paper waste at its educational events, and to eliminate plastic waste associated with mailing resources like its member magazine, Dr. Kaufmann noted.

And in keeping with the Academy pledge – also articulated in the 2018 position statement – to support and facilitate dermatologists’ efforts to decrease their carbon footprint “in a cost effective (or cost-saving) manner,” Dr. Kaufmann said that the AAD has been offering a program called My Green Doctor as a free benefit of membership.

‘Be part of the solution’

In an interview, Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said her practice did an audit of their surgical area and found ways to increase the use of paper-packaged gauze – and decrease use of gauze in hard plastic containers – and otherwise decrease the amount of disposables, all of which take “huge amounts of resources” to create.

In the process, “we found significant savings,” she said. “Little things can turn out, in the long run, to be big things.”

Asked about the commentary, Dr. Maloney, who is involved in the AAD’s climate change resource group, said “the message is that yes, we need to be aware of the diseases affected by climate change. But our greater imperative is to be part of the solution and not part of the problem as far as doing things that affect climate change.”

Organized dermatology needs to broaden its advocacy, she said. “I don’t want us to stop advocating for things for our patients, but I do want us to start advocating for the world ... If we don’t try to [mitigate] climate change, we won’t have patients to advocate for.”

Dr. Parker, an associate editor of The Journal of Climate Change and Health, and Dr. Boos declared no conflicts of interest and no funding source for their commentary. Dr. Maloney said she has no conflicts of interest.

“moving beyond merely discussing skin-related impacts” and toward prioritizing both patient and planetary health.

Dermatologists must make emissions-saving changes in everyday practice, for instance, and the specialty must enlist key stakeholders in public health, nonprofits, and industry – that is, pharmaceutical and medical supply companies – in finding solutions to help mitigate and adapt to climate change, wrote Eva Rawlings Parker, MD, and Markus D. Boos, MD, PhD.

“We have an ethical imperative to act,” they wrote. “The time is now for dermatologists and our medical societies to collectively rise to meet this crisis.”

Their commentary was published online in the International Journal of Dermatology , Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, British Journal of Dermatology, and Pediatric Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Parker, assistant professor of dermatology at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said that she and Dr. Boos, associate professor in the division of dermatology and department of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, were motivated to write the editorial upon finding that dermatology was not represented among more than 230 medical journals that published an editorial in September 2021 calling for emergency action to limit global warming and protect health. In addition to the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, the copublishing journals represented numerous specialties, from nursing and pediatrics, to cardiology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology.

The editorial was not published in any dermatology journals, Dr. Parker said. “It was incredibly disappointing for me along with many of my colleagues who advocate for climate action because we realized it was a missed opportunity for dermatology to align with other medical specialties and be on the forefront of leading climate action to protect health.”

‘A threat multiplier’

The impact of climate change on skin disease is “an incredibly important part of our conversation as dermatologists because many cutaneous diseases are climate sensitive and we’re often seeing the effects of climate change every day in our clinical practices,” Dr. Parker said.

In fact, the impact on skin disease needs to be explored much further through more robust research funding, so that dermatology can better understand not only the incidence and severity of climate-induced changes in skin diseases – including and beyond atopic dermatitis, acne, and psoriasis – but also the mechanisms and pathophysiology involved, she said.

However, the impacts are much broader, she and Dr. Boos, a pediatric dermatologist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, maintain in their commentary. “An essential concept to broker among dermatologists is that the impacts of climate change extend well beyond skin disease by also placing broad pressure” on infrastructure, the economy, financial markets, global supply chains, food and water insecurity, and more, they wrote, noting the deep inequities of climate change.

Climate change is a “threat multiplier for public health, equity, and health systems,” the commentary says. “The confluence of these climate-related pressures should sound alarm bells as they place enormous jeopardy on the practice of dermatology across all scales and regions.”

Health care is among the most carbon-intensive service sectors worldwide, contributing to almost 5% of greenhouse gas emissions globally, the commentary says. And nationally, of the estimated greenhouse gas emissions from the United States, the health care sector contributes 10%, Dr. Parker said in the interview, referring to a 2016 report.

In addition, according to a 2019 report, the United States is the top contributor to health care’s global climate footprint, contributing 27% of health care’s global emissions, Dr. Parker noted.

In their commentary, she and Dr. Boos wrote that individually and practice wide, dermatologists can impact decarbonization through measures such as virtual attendance at medical meetings and greater utilization of telehealth services. Reductions in carbon emissions were demonstrated for virtual isotretinoin follow-up visits in a recent study, and these savings could be extrapolated to other routine follow-up visits for conditions such as rosacea, monitoring of biologics in patients with well-controlled disease, and postoperative wound checks, they said.

But when it comes to measures such as significantly reducing packaging and waste and “curating supply chains to make them more sustainable,” it is medical societies that have the “larger voice and broader relationship with the pharmaceutical industry” and with medical supply manufacturers and distributors, Dr. Parker explained in the interview, noting the potential for reducing the extensive amount of packaging used for drug samples.

Dr. Parker cochairs the American Academy of Dermatology’s Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, which was established several years ago, and Dr. Boos is a member of the group’s executive committee.

AAD actions

In its 2018 Position Statement on Climate and Health, the American Academy of Dermatology resolved to raise awareness of the effects of climate change on the skin and educate patients about this, and to “work with other medical societies in ongoing and future efforts to educate the public and mitigate the effects of climate change on global health.”

Asked about the commentary’s call for more collaboration with industry and other stakeholders – and the impact that organized dermatology can have on planetary health – Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the AAD, said in an email that the AAD is “first and foremost an organization focused on providing gold-standard educational resources for dermatologists.”

The academy recognizes that “there are many dermatologic consequences of climate change that will increasingly affect our patients and challenge our membership,” and it has provided education on climate change in forums such as articles, podcasts, and sessions at AAD meetings, said Dr. Kaufmann, clinical professor in the department of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Regarding collaboration with other societies, he said that the AAD’s “focus to date has been on how to provide our members with educational resources to understand and prepare for how climate change may impact their practices and the dermatologic health of their patients,” he said.

The AAD has also sought to address its own carbon footprint and improve sustainability of its operations, including taking steps to reduce plastic and paper waste at its educational events, and to eliminate plastic waste associated with mailing resources like its member magazine, Dr. Kaufmann noted.

And in keeping with the Academy pledge – also articulated in the 2018 position statement – to support and facilitate dermatologists’ efforts to decrease their carbon footprint “in a cost effective (or cost-saving) manner,” Dr. Kaufmann said that the AAD has been offering a program called My Green Doctor as a free benefit of membership.

‘Be part of the solution’

In an interview, Mary E. Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, said her practice did an audit of their surgical area and found ways to increase the use of paper-packaged gauze – and decrease use of gauze in hard plastic containers – and otherwise decrease the amount of disposables, all of which take “huge amounts of resources” to create.

In the process, “we found significant savings,” she said. “Little things can turn out, in the long run, to be big things.”

Asked about the commentary, Dr. Maloney, who is involved in the AAD’s climate change resource group, said “the message is that yes, we need to be aware of the diseases affected by climate change. But our greater imperative is to be part of the solution and not part of the problem as far as doing things that affect climate change.”

Organized dermatology needs to broaden its advocacy, she said. “I don’t want us to stop advocating for things for our patients, but I do want us to start advocating for the world ... If we don’t try to [mitigate] climate change, we won’t have patients to advocate for.”

Dr. Parker, an associate editor of The Journal of Climate Change and Health, and Dr. Boos declared no conflicts of interest and no funding source for their commentary. Dr. Maloney said she has no conflicts of interest.

The marked contrast in pandemic outcomes between Japan and the United States

This article was originally published Oct. 8 on Medscape Editor-In-Chief Eric Topol’s “Ground Truths” column on Substack.

Over time it has the least cumulative deaths per capita of any major country in the world. That’s without a zero-Covid policy or any national lockdowns, which is why I have not included China as a comparator.

Before we get into that data, let’s take a look at the age pyramids for Japan and the United States. The No. 1 risk factor for death from COVID-19 is advanced age, and you can see that in Japan about 25% of the population is age 65 and older, whereas in the United States that proportion is substantially reduced at 15%. Sure there are differences in comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes, but there is also the trade-off of a much higher population density in Japan.

Besides masks, which were distributed early on by the government to the population in Japan, there was the “Avoid the 3Cs” cluster-busting strategy, widely disseminated in the spring of 2020, leveraging Pareto’s 80-20 principle, long before there were any vaccines available. For a good portion of the pandemic, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan maintained a strict policy for border control, which while hard to quantify, may certainly have contributed to its success.

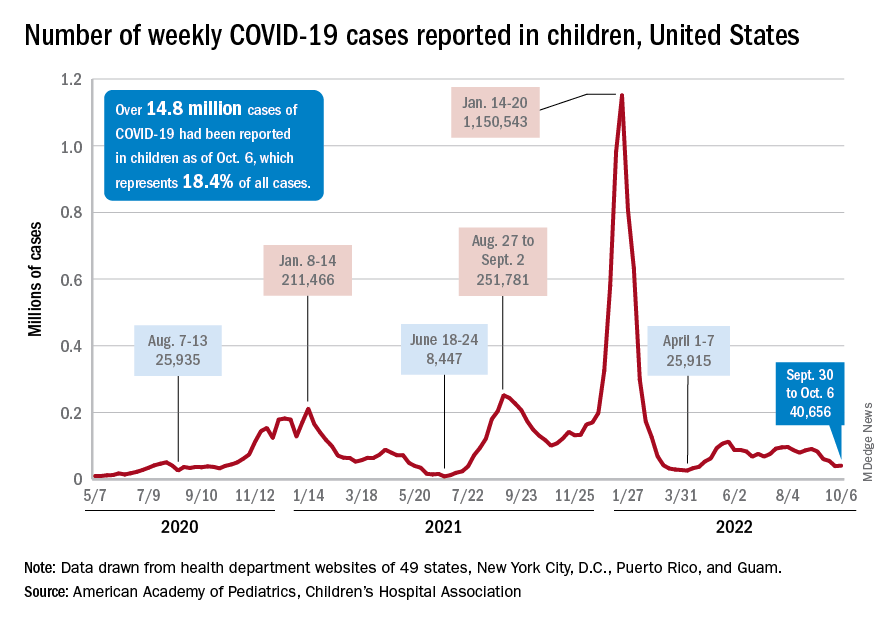

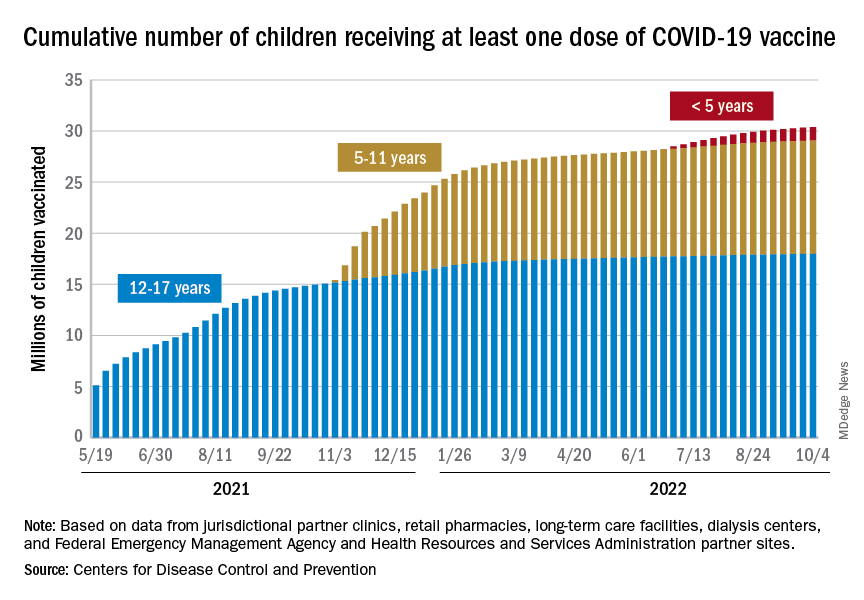

Besides these factors, once vaccines became available, Japan got the population with the primary series to 83% rapidly, even after getting a late start by many months compared with the United States, which has peaked at 68%. That’s a big gap.

But that gap got much worse when it came to boosters. Ninety-five percent of Japanese eligible compared with 40.8% of Americans have had a booster shot. Of note, that 95% in Japan pertains to the whole population. In the United States the percentage of people age 65 and older who have had two boosters is currently only 42%. I’ve previously reviewed the important lifesaving impact of two boosters among people age 65 and older from five independent studies during Omicron waves throughout the world.

Now let’s turn to cumulative fatalities in the two countries. There’s a huge, nearly ninefold difference, per capita. Using today’s Covid-19 Dashboard, there are cumulatively 45,533 deaths in Japan and 1,062,560 American deaths. That translates to 1 in 2,758 people in Japan compared with 1 in 315 Americans dying of COVID.

And if we look at excess mortality instead of confirmed COVID deaths, that enormous gap doesn’t change.

Obviously it would be good to have data for other COVID outcomes, such as hospitalizations, ICUs, and Long COVID, but they are not accessible.