User login

Microbiome Impacts Vaccine Responses

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

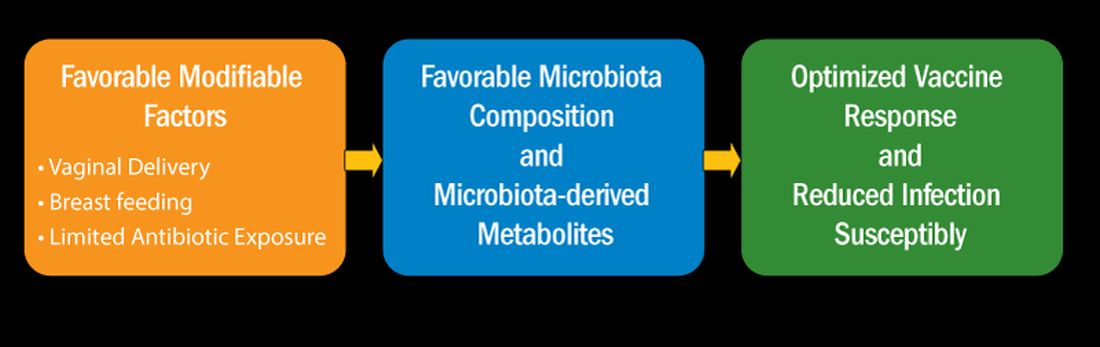

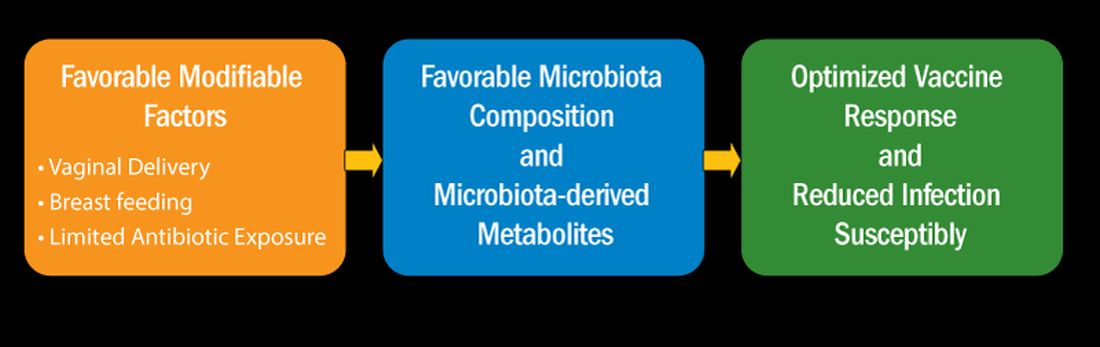

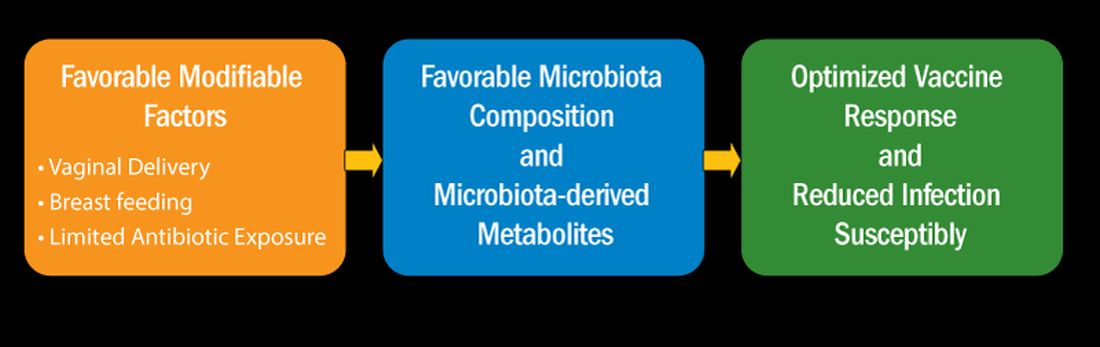

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

HPV Vaccine Shown to Be Highly Effective in Girls Years Later

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Breakthrough Drug Whose Full Promise Remains Unrealized

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.

Given its high cost, rules restricting a patient to only one course of sofosbuvir-based therapy also surfaced. Although treatment with first-generation protease inhibitors carried a hefty price of $161,813.49 per sustained virologic response (SVR), compared with $66,000-$100,000 for 12 weeks of all-oral therapy, its uptake was low and limited by side effects and comorbid conditions. All-oral treatment appeared to have few medical barriers, leading payers to find ways to slow utilization. These restrictions are now gradually being eliminated.

Because of high SVR rates and few contraindications to therapy, most patients who gained access to treatment achieved cure. This included patients who had previously not responded to treatment and prioritized those with more advanced disease.

This quickly led to a significant shift in the population in need of treatment. Prior to 2013, many patients with HCV had advanced disease and did not respond to prior treatment options. After uptake of all-oral therapy, individuals in need were typically treatment naive without advanced disease.

This shift also added new psychosocial dimensions, as many of the newly infected individuals were struggling with active substance abuse. HCV treatment providers needed to change, with increasing recruitment of advanced practice providers, primary care physicians, and addiction medication specialists.

Progress, but Far From Reaching Targets

Fast-forward to 2023.

Ten years after FDA approval, 13.2 million individuals infected with HCV have been treated globally, 82% with sofosbuvir-based regimens and most in lower-middle-income countries. This is absolutely cause for celebration, but not complacency.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined elimination of HCV as 90% reduction in new cases of infection, 90% diagnosis of those infected, 80% of eligible individuals treated, and 65% reduction of deaths by 2030.

Despite all the success thus far, the CDA Foundation estimates that the WHO elimination targets will not be achieved until after the year 2050. They also note that in 2020, over 50 million individuals were infected with HCV, of which only 20% were diagnosed and 1% annually treated.

The HCV care cascade, by which the patient journeys from screening to cure, is complicated, and a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible. Reflex testing (an automatic transition to HCV polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing in the lab for those who are HCV antibody positive) has significantly improved diagnosis. However, communicating these results and linking a patient to curative therapy remain significant obstacles.

Models and real-life experience show that multiple strategies can be successful. They include leveraging the electronic medical record, simplified treatment algorithms, test-and-treat strategies (screening high-risk populations with a point-of-care test that allows treatment initiation at the same visit), and co-localizing HCV screening and treatment with addiction services and relinkage programs (finding those who are already diagnosed and linking them to treatment).

In addition, focusing on populations at high risk for HCV infection — such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and incarcerated individuals — allows for better resource utilization.

Though daunting, HCV elimination is not impossible. There are several examples of success, including in the countries of Georgia and Iceland. Although, comparatively, the United States remains behind the curve, the White House has asked Congress for $11 billion to fund HCV elimination domestically.

As we await action at the national level, clinicians are reminded that there are several things we can do in caring for patients with HCV:

- A one-time HCV screening is recommended in all individuals aged 18 or older, including pregnant people with each pregnancy.

- HCV antibody testing with reflex to PCR should be used as the screening test.

- Pan-genotypic all-oral therapy is recommended for patients with HCV. Cure rates are greater than 95%, and there are few contraindications to treatment.

- Most people are eligible for simplified treatment algorithms that allow minimal on-treatment monitoring.

Without increased screening and linkage to curative therapy, we will not meet the WHO goals for HCV elimination.

Dr. Reau is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a regular contributor to this news organization. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as educational chair of the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels. She disclosed ties with AbbVie, Gilead, Arbutus, Intercept, and Salix.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.

Given its high cost, rules restricting a patient to only one course of sofosbuvir-based therapy also surfaced. Although treatment with first-generation protease inhibitors carried a hefty price of $161,813.49 per sustained virologic response (SVR), compared with $66,000-$100,000 for 12 weeks of all-oral therapy, its uptake was low and limited by side effects and comorbid conditions. All-oral treatment appeared to have few medical barriers, leading payers to find ways to slow utilization. These restrictions are now gradually being eliminated.

Because of high SVR rates and few contraindications to therapy, most patients who gained access to treatment achieved cure. This included patients who had previously not responded to treatment and prioritized those with more advanced disease.

This quickly led to a significant shift in the population in need of treatment. Prior to 2013, many patients with HCV had advanced disease and did not respond to prior treatment options. After uptake of all-oral therapy, individuals in need were typically treatment naive without advanced disease.

This shift also added new psychosocial dimensions, as many of the newly infected individuals were struggling with active substance abuse. HCV treatment providers needed to change, with increasing recruitment of advanced practice providers, primary care physicians, and addiction medication specialists.

Progress, but Far From Reaching Targets

Fast-forward to 2023.

Ten years after FDA approval, 13.2 million individuals infected with HCV have been treated globally, 82% with sofosbuvir-based regimens and most in lower-middle-income countries. This is absolutely cause for celebration, but not complacency.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined elimination of HCV as 90% reduction in new cases of infection, 90% diagnosis of those infected, 80% of eligible individuals treated, and 65% reduction of deaths by 2030.

Despite all the success thus far, the CDA Foundation estimates that the WHO elimination targets will not be achieved until after the year 2050. They also note that in 2020, over 50 million individuals were infected with HCV, of which only 20% were diagnosed and 1% annually treated.

The HCV care cascade, by which the patient journeys from screening to cure, is complicated, and a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible. Reflex testing (an automatic transition to HCV polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing in the lab for those who are HCV antibody positive) has significantly improved diagnosis. However, communicating these results and linking a patient to curative therapy remain significant obstacles.

Models and real-life experience show that multiple strategies can be successful. They include leveraging the electronic medical record, simplified treatment algorithms, test-and-treat strategies (screening high-risk populations with a point-of-care test that allows treatment initiation at the same visit), and co-localizing HCV screening and treatment with addiction services and relinkage programs (finding those who are already diagnosed and linking them to treatment).

In addition, focusing on populations at high risk for HCV infection — such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and incarcerated individuals — allows for better resource utilization.

Though daunting, HCV elimination is not impossible. There are several examples of success, including in the countries of Georgia and Iceland. Although, comparatively, the United States remains behind the curve, the White House has asked Congress for $11 billion to fund HCV elimination domestically.

As we await action at the national level, clinicians are reminded that there are several things we can do in caring for patients with HCV:

- A one-time HCV screening is recommended in all individuals aged 18 or older, including pregnant people with each pregnancy.

- HCV antibody testing with reflex to PCR should be used as the screening test.

- Pan-genotypic all-oral therapy is recommended for patients with HCV. Cure rates are greater than 95%, and there are few contraindications to treatment.

- Most people are eligible for simplified treatment algorithms that allow minimal on-treatment monitoring.

Without increased screening and linkage to curative therapy, we will not meet the WHO goals for HCV elimination.

Dr. Reau is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a regular contributor to this news organization. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as educational chair of the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels. She disclosed ties with AbbVie, Gilead, Arbutus, Intercept, and Salix.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.

Given its high cost, rules restricting a patient to only one course of sofosbuvir-based therapy also surfaced. Although treatment with first-generation protease inhibitors carried a hefty price of $161,813.49 per sustained virologic response (SVR), compared with $66,000-$100,000 for 12 weeks of all-oral therapy, its uptake was low and limited by side effects and comorbid conditions. All-oral treatment appeared to have few medical barriers, leading payers to find ways to slow utilization. These restrictions are now gradually being eliminated.

Because of high SVR rates and few contraindications to therapy, most patients who gained access to treatment achieved cure. This included patients who had previously not responded to treatment and prioritized those with more advanced disease.

This quickly led to a significant shift in the population in need of treatment. Prior to 2013, many patients with HCV had advanced disease and did not respond to prior treatment options. After uptake of all-oral therapy, individuals in need were typically treatment naive without advanced disease.

This shift also added new psychosocial dimensions, as many of the newly infected individuals were struggling with active substance abuse. HCV treatment providers needed to change, with increasing recruitment of advanced practice providers, primary care physicians, and addiction medication specialists.

Progress, but Far From Reaching Targets

Fast-forward to 2023.

Ten years after FDA approval, 13.2 million individuals infected with HCV have been treated globally, 82% with sofosbuvir-based regimens and most in lower-middle-income countries. This is absolutely cause for celebration, but not complacency.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined elimination of HCV as 90% reduction in new cases of infection, 90% diagnosis of those infected, 80% of eligible individuals treated, and 65% reduction of deaths by 2030.

Despite all the success thus far, the CDA Foundation estimates that the WHO elimination targets will not be achieved until after the year 2050. They also note that in 2020, over 50 million individuals were infected with HCV, of which only 20% were diagnosed and 1% annually treated.

The HCV care cascade, by which the patient journeys from screening to cure, is complicated, and a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible. Reflex testing (an automatic transition to HCV polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing in the lab for those who are HCV antibody positive) has significantly improved diagnosis. However, communicating these results and linking a patient to curative therapy remain significant obstacles.

Models and real-life experience show that multiple strategies can be successful. They include leveraging the electronic medical record, simplified treatment algorithms, test-and-treat strategies (screening high-risk populations with a point-of-care test that allows treatment initiation at the same visit), and co-localizing HCV screening and treatment with addiction services and relinkage programs (finding those who are already diagnosed and linking them to treatment).

In addition, focusing on populations at high risk for HCV infection — such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and incarcerated individuals — allows for better resource utilization.

Though daunting, HCV elimination is not impossible. There are several examples of success, including in the countries of Georgia and Iceland. Although, comparatively, the United States remains behind the curve, the White House has asked Congress for $11 billion to fund HCV elimination domestically.

As we await action at the national level, clinicians are reminded that there are several things we can do in caring for patients with HCV:

- A one-time HCV screening is recommended in all individuals aged 18 or older, including pregnant people with each pregnancy.

- HCV antibody testing with reflex to PCR should be used as the screening test.

- Pan-genotypic all-oral therapy is recommended for patients with HCV. Cure rates are greater than 95%, and there are few contraindications to treatment.

- Most people are eligible for simplified treatment algorithms that allow minimal on-treatment monitoring.

Without increased screening and linkage to curative therapy, we will not meet the WHO goals for HCV elimination.

Dr. Reau is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a regular contributor to this news organization. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as educational chair of the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels. She disclosed ties with AbbVie, Gilead, Arbutus, Intercept, and Salix.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Five Bold Predictions for Long COVID in 2024

With a number of large-scale clinical trials underway and researchers on the hunt for new therapies, long COVID scientists are hopeful that this is the year patients — and doctors who care for them — will finally see improvements in treating their symptoms.

Here are five bold predictions — all based on encouraging research — that could happen in 2024. At the very least, they are promising signs of progress against a debilitating and frustrating disease.

#1: We’ll gain a better understanding of each long COVID phenotype

This past year, a wide breadth of research began showing that long COVID can be defined by a number of different disease phenotypes that present a range of symptoms.

Researchers identified four clinical phenotypes: Chronic fatigue-like syndrome, headache, and memory loss; respiratory syndrome, which includes cough and difficulty breathing; chronic pain; and neurosensorial syndrome, which causes an altered sense of taste and smell.

Identifying specific diagnostic criteria for each phenotype would lead to better health outcomes for patients instead of treating them as if it were a “one-size-fits-all disease,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the long COVID program at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, California.

Ultimately, she hopes that this year her patients will receive treatments based on the type of long COVID they’re personally experiencing, and the symptoms they have, leading to improved health outcomes and more rapid relief.

“Many new medications are focused on different pathways of long COVID, and the challenge becomes which drug is the right drug for each treatment,” said Dr. Viswanathan.

#2: Monoclonal antibodies may change the game

We’re starting to have a better understanding that what’s been called “viral persistence” as a main cause of long COVID may potentially be treated with monoclonal antibodies. These are antibodies produced by cloning unique white blood cells to target the circulating spike proteins in the blood that hang out in viral reservoirs and cause the immune system to react as if it’s still fighting acute COVID-19.

Smaller-scale studies have already shown promising results. A January 2024 study published in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine followed three patients who completely recovered from long COVID after taking monoclonal antibodies. “Remission occurred despite dissimilar past histories, sex, age, and illness duration,” wrote the study authors.

Larger clinical trials are underway at the University of California, San Francisco, California, to test targeted monoclonal antibodies. If the results of the larger study show that monoclonal antibodies are beneficial, then it could be a game changer for a large swath of patients around the world, said David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

“The idea is that the downstream damage caused by viral persistence will resolve itself once you wipe out the virus,” said Dr. Putrino.

#3: Paxlovid could prove effective for long COVID

The US Food and Drug Administration granted approval for Paxlovid last May for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults at a high risk for severe disease. The medication is made up of two drugs packaged together. The first, nirmatrelvir, works by blocking a key enzyme required for virus replication. The second, ritonavir, is an antiviral that’s been used in patients with HIV and helps boost levels of antivirals in the body.

In a large-scale trial headed up by Dr. Putrino and his team, the oral antiviral is being studied for use in the post-viral stage in patients who test negative for acute COVID-19 but have persisting symptoms of long COVID.

Similar to monoclonal antibodies, the idea is to quell viral persistence. If patients have long COVID because they can’t clear SAR-CoV-2 from their bodies, Paxlovid could help. But unlike monoclonal antibodies that quash the virus, Paxlovid stops the virus from replicating. It’s a different mechanism with the same end goal.

It’s been a controversial treatment because it’s life-changing for some patients and ineffective for others. In addition, it can cause a range of side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and an impaired sense of taste. The goal of the trial is to see which patients with long COVID are most likely to benefit from the treatment.

#4: Anti-inflammatories like metformin could prove useful

Many of the inflammatory markers persistent in patients with long COVID were similarly present in patients with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, according to a July 2023 study published in JAMA.

The hope is that anti-inflammatory medications may be used to reduce inflammation causing long COVID symptoms. But drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis like abatacept and infliximabcan also have serious side effects, including increased risk for infection, flu-like symptoms, and burning of the skin.

“Powerful anti-inflammatories can change a number of pathways in the immune system,” said Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. Anti-inflammatories hold promise but, Dr. McComsey said, “some are more toxic with many side effects, so even if they work, there’s still a question about who should take them.”

Still, other anti-inflammatories that could work don’t have as many side effects. For example, a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases found that the diabetes drug metformin reduced a patient’s risk for long COVID up to 40% when the drug was taken during the acute stage.

Metformin, compared to other anti-inflammatories (also known as immune modulators), is an inexpensive and widely available drug with relatively few side effects compared with other medications.

#5: Serotonin levels — and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — may be keys to unlocking long COVID

One of the most groundbreaking studies of the year came last November. A study published in the journal Cell found lower circulating serotonin levels in patents with long COVID than in those who did not have the condition. The study also found that the SSRI fluoxetine improved cognitive function in rat models infected with the virus.

Researchers found that the reduction in serotonin levels was partially caused by the body’s inability to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactivated blood platelets may also have played a role.

Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, California, hopes to take the finding a step further, investigating whether increased serotonin levels in patients with long COVID will lead to improvements in symptoms.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said last month in an interview with this news organization.

If patients show an improvement in symptoms, then the next step is looking into whether SSRIs boost serotonin levels in patients and, as a result, reduce their symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With a number of large-scale clinical trials underway and researchers on the hunt for new therapies, long COVID scientists are hopeful that this is the year patients — and doctors who care for them — will finally see improvements in treating their symptoms.

Here are five bold predictions — all based on encouraging research — that could happen in 2024. At the very least, they are promising signs of progress against a debilitating and frustrating disease.

#1: We’ll gain a better understanding of each long COVID phenotype

This past year, a wide breadth of research began showing that long COVID can be defined by a number of different disease phenotypes that present a range of symptoms.

Researchers identified four clinical phenotypes: Chronic fatigue-like syndrome, headache, and memory loss; respiratory syndrome, which includes cough and difficulty breathing; chronic pain; and neurosensorial syndrome, which causes an altered sense of taste and smell.

Identifying specific diagnostic criteria for each phenotype would lead to better health outcomes for patients instead of treating them as if it were a “one-size-fits-all disease,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the long COVID program at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, California.

Ultimately, she hopes that this year her patients will receive treatments based on the type of long COVID they’re personally experiencing, and the symptoms they have, leading to improved health outcomes and more rapid relief.

“Many new medications are focused on different pathways of long COVID, and the challenge becomes which drug is the right drug for each treatment,” said Dr. Viswanathan.

#2: Monoclonal antibodies may change the game

We’re starting to have a better understanding that what’s been called “viral persistence” as a main cause of long COVID may potentially be treated with monoclonal antibodies. These are antibodies produced by cloning unique white blood cells to target the circulating spike proteins in the blood that hang out in viral reservoirs and cause the immune system to react as if it’s still fighting acute COVID-19.

Smaller-scale studies have already shown promising results. A January 2024 study published in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine followed three patients who completely recovered from long COVID after taking monoclonal antibodies. “Remission occurred despite dissimilar past histories, sex, age, and illness duration,” wrote the study authors.

Larger clinical trials are underway at the University of California, San Francisco, California, to test targeted monoclonal antibodies. If the results of the larger study show that monoclonal antibodies are beneficial, then it could be a game changer for a large swath of patients around the world, said David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

“The idea is that the downstream damage caused by viral persistence will resolve itself once you wipe out the virus,” said Dr. Putrino.

#3: Paxlovid could prove effective for long COVID

The US Food and Drug Administration granted approval for Paxlovid last May for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults at a high risk for severe disease. The medication is made up of two drugs packaged together. The first, nirmatrelvir, works by blocking a key enzyme required for virus replication. The second, ritonavir, is an antiviral that’s been used in patients with HIV and helps boost levels of antivirals in the body.

In a large-scale trial headed up by Dr. Putrino and his team, the oral antiviral is being studied for use in the post-viral stage in patients who test negative for acute COVID-19 but have persisting symptoms of long COVID.

Similar to monoclonal antibodies, the idea is to quell viral persistence. If patients have long COVID because they can’t clear SAR-CoV-2 from their bodies, Paxlovid could help. But unlike monoclonal antibodies that quash the virus, Paxlovid stops the virus from replicating. It’s a different mechanism with the same end goal.

It’s been a controversial treatment because it’s life-changing for some patients and ineffective for others. In addition, it can cause a range of side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and an impaired sense of taste. The goal of the trial is to see which patients with long COVID are most likely to benefit from the treatment.

#4: Anti-inflammatories like metformin could prove useful

Many of the inflammatory markers persistent in patients with long COVID were similarly present in patients with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, according to a July 2023 study published in JAMA.

The hope is that anti-inflammatory medications may be used to reduce inflammation causing long COVID symptoms. But drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis like abatacept and infliximabcan also have serious side effects, including increased risk for infection, flu-like symptoms, and burning of the skin.

“Powerful anti-inflammatories can change a number of pathways in the immune system,” said Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. Anti-inflammatories hold promise but, Dr. McComsey said, “some are more toxic with many side effects, so even if they work, there’s still a question about who should take them.”

Still, other anti-inflammatories that could work don’t have as many side effects. For example, a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases found that the diabetes drug metformin reduced a patient’s risk for long COVID up to 40% when the drug was taken during the acute stage.

Metformin, compared to other anti-inflammatories (also known as immune modulators), is an inexpensive and widely available drug with relatively few side effects compared with other medications.

#5: Serotonin levels — and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — may be keys to unlocking long COVID

One of the most groundbreaking studies of the year came last November. A study published in the journal Cell found lower circulating serotonin levels in patents with long COVID than in those who did not have the condition. The study also found that the SSRI fluoxetine improved cognitive function in rat models infected with the virus.

Researchers found that the reduction in serotonin levels was partially caused by the body’s inability to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactivated blood platelets may also have played a role.

Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, California, hopes to take the finding a step further, investigating whether increased serotonin levels in patients with long COVID will lead to improvements in symptoms.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said last month in an interview with this news organization.

If patients show an improvement in symptoms, then the next step is looking into whether SSRIs boost serotonin levels in patients and, as a result, reduce their symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With a number of large-scale clinical trials underway and researchers on the hunt for new therapies, long COVID scientists are hopeful that this is the year patients — and doctors who care for them — will finally see improvements in treating their symptoms.

Here are five bold predictions — all based on encouraging research — that could happen in 2024. At the very least, they are promising signs of progress against a debilitating and frustrating disease.

#1: We’ll gain a better understanding of each long COVID phenotype

This past year, a wide breadth of research began showing that long COVID can be defined by a number of different disease phenotypes that present a range of symptoms.

Researchers identified four clinical phenotypes: Chronic fatigue-like syndrome, headache, and memory loss; respiratory syndrome, which includes cough and difficulty breathing; chronic pain; and neurosensorial syndrome, which causes an altered sense of taste and smell.

Identifying specific diagnostic criteria for each phenotype would lead to better health outcomes for patients instead of treating them as if it were a “one-size-fits-all disease,” said Nisha Viswanathan, MD, director of the long COVID program at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, California.

Ultimately, she hopes that this year her patients will receive treatments based on the type of long COVID they’re personally experiencing, and the symptoms they have, leading to improved health outcomes and more rapid relief.

“Many new medications are focused on different pathways of long COVID, and the challenge becomes which drug is the right drug for each treatment,” said Dr. Viswanathan.

#2: Monoclonal antibodies may change the game

We’re starting to have a better understanding that what’s been called “viral persistence” as a main cause of long COVID may potentially be treated with monoclonal antibodies. These are antibodies produced by cloning unique white blood cells to target the circulating spike proteins in the blood that hang out in viral reservoirs and cause the immune system to react as if it’s still fighting acute COVID-19.

Smaller-scale studies have already shown promising results. A January 2024 study published in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine followed three patients who completely recovered from long COVID after taking monoclonal antibodies. “Remission occurred despite dissimilar past histories, sex, age, and illness duration,” wrote the study authors.

Larger clinical trials are underway at the University of California, San Francisco, California, to test targeted monoclonal antibodies. If the results of the larger study show that monoclonal antibodies are beneficial, then it could be a game changer for a large swath of patients around the world, said David F. Putrino, PhD, who runs the long COVID clinic at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

“The idea is that the downstream damage caused by viral persistence will resolve itself once you wipe out the virus,” said Dr. Putrino.

#3: Paxlovid could prove effective for long COVID

The US Food and Drug Administration granted approval for Paxlovid last May for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults at a high risk for severe disease. The medication is made up of two drugs packaged together. The first, nirmatrelvir, works by blocking a key enzyme required for virus replication. The second, ritonavir, is an antiviral that’s been used in patients with HIV and helps boost levels of antivirals in the body.

In a large-scale trial headed up by Dr. Putrino and his team, the oral antiviral is being studied for use in the post-viral stage in patients who test negative for acute COVID-19 but have persisting symptoms of long COVID.

Similar to monoclonal antibodies, the idea is to quell viral persistence. If patients have long COVID because they can’t clear SAR-CoV-2 from their bodies, Paxlovid could help. But unlike monoclonal antibodies that quash the virus, Paxlovid stops the virus from replicating. It’s a different mechanism with the same end goal.

It’s been a controversial treatment because it’s life-changing for some patients and ineffective for others. In addition, it can cause a range of side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and an impaired sense of taste. The goal of the trial is to see which patients with long COVID are most likely to benefit from the treatment.

#4: Anti-inflammatories like metformin could prove useful

Many of the inflammatory markers persistent in patients with long COVID were similarly present in patients with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, according to a July 2023 study published in JAMA.

The hope is that anti-inflammatory medications may be used to reduce inflammation causing long COVID symptoms. But drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis like abatacept and infliximabcan also have serious side effects, including increased risk for infection, flu-like symptoms, and burning of the skin.

“Powerful anti-inflammatories can change a number of pathways in the immune system,” said Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, Ohio. Anti-inflammatories hold promise but, Dr. McComsey said, “some are more toxic with many side effects, so even if they work, there’s still a question about who should take them.”

Still, other anti-inflammatories that could work don’t have as many side effects. For example, a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases found that the diabetes drug metformin reduced a patient’s risk for long COVID up to 40% when the drug was taken during the acute stage.

Metformin, compared to other anti-inflammatories (also known as immune modulators), is an inexpensive and widely available drug with relatively few side effects compared with other medications.

#5: Serotonin levels — and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) — may be keys to unlocking long COVID

One of the most groundbreaking studies of the year came last November. A study published in the journal Cell found lower circulating serotonin levels in patents with long COVID than in those who did not have the condition. The study also found that the SSRI fluoxetine improved cognitive function in rat models infected with the virus.

Researchers found that the reduction in serotonin levels was partially caused by the body’s inability to absorb tryptophan, an amino acid that’s a precursor to serotonin. Overactivated blood platelets may also have played a role.

Michael Peluso, MD, an assistant research professor of infectious medicine at the UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, California, hopes to take the finding a step further, investigating whether increased serotonin levels in patients with long COVID will lead to improvements in symptoms.

“What we need now is a good clinical trial to see whether altering levels of serotonin in people with long COVID will lead to symptom relief,” Dr. Peluso said last month in an interview with this news organization.

If patients show an improvement in symptoms, then the next step is looking into whether SSRIs boost serotonin levels in patients and, as a result, reduce their symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

DoxyPEP: A New Option to Prevent Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to have a significant impact on the lives of adolescents and young adults. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) 2021 surveillance report, rates of gonorrhea and syphilis in the United States were at their highest since the early 1990s. Chlamydia, one of the most common STIs, had a peak rate in 2019, but more recent rates may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, those 15-24 years of age accounted for 58.5% of all chlamydia infections, 40.4% of all gonorrhea infections, and 18.3% of all syphilis infections in the US.

While pediatricians should discuss sexual health and STI screening with all their adolescent and young adult patients, LGBTQ+ youth are disproportionately impacted by STIs. For example, cisgender men who have sex with men have significantly higher rates of HIV, gonorrhea, and syphilis. These disparities are likely related to unequal access to care, systemic homophobia/transphobia, stigma, and differences in sexual networks and are even more pronounced for those with intersectional minoritized identities such as LGBTQ+ youth of color.1

In the past 12 years, there have been significant advances in HIV prevention methods, including the approval and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis or “PrEP” (a medication regimen that is taken on an ongoing basis to provide highly effective protection against HIV infection) and more widespread use of post-exposure prophylaxis or “PEP” (a medication regimen taken for 1 month after a potential exposure to HIV to prevent HIV from establishing an ongoing infection) outside of the medical setting. While these interventions have the potential to decrease rates of HIV infection, they do not prevent any other STIs.2-3

The current strategies to prevent bacterial STIs include discussions of sexual practices, counseling on risk reduction strategies such as decreased number of partners and condom use, routine screening in those at risk every 3-12 months, and timely diagnosis and treatment of infections in patients and their partners to avoid further transmission.4 Given the increasing rates of bacterial STIs (gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis), additional biomedical prevention methods are greatly needed.

Doxycycline as post-exposure prophylaxis

Doxycycline is a tetracycline antibiotic effective against a wide range of bacteria and is commonly used in the treatment of acne, skin infections, Lyme disease, and STIs, and can also be used in the treatment and prevention of malaria.5 For STIs, doxycycline is currently the recommended treatment for chlamydia and is also an alternate therapy for syphilis in nonpregnant patients when penicillin is not accessible or in those with severe penicillin allergy.4 This medication is often well tolerated with the most common side effects including gastrointestinal irritation and photosensitivity. Doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy due to its potential impact on tooth and bone development.5