User login

HCV-infected people who inject drugs also have substantial alcohol use

Curing hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection without addressing the high rate of alcohol use disorder in many patients may undermine the benefits of treatment to long-term liver health, according to the results of a large cohort study.

Because excess alcohol use is known to accelerate liver disease progression, researchers Risha Irvin, MD, and her colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined the prevalence of alcohol use in HCV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID). Their study examined the prevalence and associated correlates of alcohol use (Addictive Behaviors 2019;96:56-61).

They followed a large cohort of 1,623 HCV-antibody positive PWID from 2005 to 2013 from the AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience (ALIVE) study. They characterized alcohol use with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. Multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimated equations was used to examine sociodemographic, clinical, and substance use correlates of alcohol use.

At baseline, the median age was 47 years, 67% were men, 81% were black, and 34% were HIV positive. The majority (60%) reported injection drug use in the prior 6 months, while 46% reported noninjection cocaine or heroin, 31% reported street-acquired prescription drugs, and 22% reported marijuana use in the same time period. According to the AUDIT-C results, 41% of the patients reported no alcohol use, 21% reported moderate alcohol use, and 38% reported heavy alcohol use at their baseline visit.

The factors that were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use included male sex, black race, income of $5,000 or less, a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (range 0-60) score of 23 or greater, being homeless, being incarcerated, marijuana use, use of street-acquired prescription drugs, noninjection cocaine/heroin, injection drug use, and cigarette smoking. In a model that included the composite summary variable for substance use intensity, one drug type (adjusted odds ratio, 1.92), two drug types (AOR, 2.93), and three drug types (AOR, 3.65) were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use.

“While clinicians are undoubtedly concerned about any level of alcohol use in the setting of HCV infection due to the acceleration of liver fibrosis, there is particular concern for individuals with heavy alcohol use and their increased risk for cirrhosis and liver failure even after HCV cure. Without intervention, alcohol use will persist after HCV is cured with the potential to undermine the benefit of HCV cure. Therefore, our data point to the need to invest in and develop programs that effectively address alcohol use and co-occurring substance use in this population of PWID with HCV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Irvin R et al. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;96:56-61.

Curing hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection without addressing the high rate of alcohol use disorder in many patients may undermine the benefits of treatment to long-term liver health, according to the results of a large cohort study.

Because excess alcohol use is known to accelerate liver disease progression, researchers Risha Irvin, MD, and her colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined the prevalence of alcohol use in HCV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID). Their study examined the prevalence and associated correlates of alcohol use (Addictive Behaviors 2019;96:56-61).

They followed a large cohort of 1,623 HCV-antibody positive PWID from 2005 to 2013 from the AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience (ALIVE) study. They characterized alcohol use with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. Multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimated equations was used to examine sociodemographic, clinical, and substance use correlates of alcohol use.

At baseline, the median age was 47 years, 67% were men, 81% were black, and 34% were HIV positive. The majority (60%) reported injection drug use in the prior 6 months, while 46% reported noninjection cocaine or heroin, 31% reported street-acquired prescription drugs, and 22% reported marijuana use in the same time period. According to the AUDIT-C results, 41% of the patients reported no alcohol use, 21% reported moderate alcohol use, and 38% reported heavy alcohol use at their baseline visit.

The factors that were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use included male sex, black race, income of $5,000 or less, a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (range 0-60) score of 23 or greater, being homeless, being incarcerated, marijuana use, use of street-acquired prescription drugs, noninjection cocaine/heroin, injection drug use, and cigarette smoking. In a model that included the composite summary variable for substance use intensity, one drug type (adjusted odds ratio, 1.92), two drug types (AOR, 2.93), and three drug types (AOR, 3.65) were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use.

“While clinicians are undoubtedly concerned about any level of alcohol use in the setting of HCV infection due to the acceleration of liver fibrosis, there is particular concern for individuals with heavy alcohol use and their increased risk for cirrhosis and liver failure even after HCV cure. Without intervention, alcohol use will persist after HCV is cured with the potential to undermine the benefit of HCV cure. Therefore, our data point to the need to invest in and develop programs that effectively address alcohol use and co-occurring substance use in this population of PWID with HCV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Irvin R et al. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;96:56-61.

Curing hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection without addressing the high rate of alcohol use disorder in many patients may undermine the benefits of treatment to long-term liver health, according to the results of a large cohort study.

Because excess alcohol use is known to accelerate liver disease progression, researchers Risha Irvin, MD, and her colleagues from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, examined the prevalence of alcohol use in HCV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID). Their study examined the prevalence and associated correlates of alcohol use (Addictive Behaviors 2019;96:56-61).

They followed a large cohort of 1,623 HCV-antibody positive PWID from 2005 to 2013 from the AIDS Linked to the Intravenous Experience (ALIVE) study. They characterized alcohol use with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. Multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimated equations was used to examine sociodemographic, clinical, and substance use correlates of alcohol use.

At baseline, the median age was 47 years, 67% were men, 81% were black, and 34% were HIV positive. The majority (60%) reported injection drug use in the prior 6 months, while 46% reported noninjection cocaine or heroin, 31% reported street-acquired prescription drugs, and 22% reported marijuana use in the same time period. According to the AUDIT-C results, 41% of the patients reported no alcohol use, 21% reported moderate alcohol use, and 38% reported heavy alcohol use at their baseline visit.

The factors that were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use included male sex, black race, income of $5,000 or less, a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (range 0-60) score of 23 or greater, being homeless, being incarcerated, marijuana use, use of street-acquired prescription drugs, noninjection cocaine/heroin, injection drug use, and cigarette smoking. In a model that included the composite summary variable for substance use intensity, one drug type (adjusted odds ratio, 1.92), two drug types (AOR, 2.93), and three drug types (AOR, 3.65) were significantly associated with heavy alcohol use.

“While clinicians are undoubtedly concerned about any level of alcohol use in the setting of HCV infection due to the acceleration of liver fibrosis, there is particular concern for individuals with heavy alcohol use and their increased risk for cirrhosis and liver failure even after HCV cure. Without intervention, alcohol use will persist after HCV is cured with the potential to undermine the benefit of HCV cure. Therefore, our data point to the need to invest in and develop programs that effectively address alcohol use and co-occurring substance use in this population of PWID with HCV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Irvin R et al. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;96:56-61.

FROM ADDICTIVE BEHAVIORS

Too many blood cultures ordered for pediatric SSTIs

SEATTLE – Blood cultures were ordered for over half of pediatric skin infection encounters across 38 children’s hospitals, with rates varying from about 20% to 80% between hospitals, according to a review of almost 50,000 encounters in the Pediatric Health Information System database.

It was a surprising finding, because current guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America do not recommend blood cultures as part of the routine evaluation of uncomplicated pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs), meaning infections in children who are otherwise healthy without neutropenia or other complicating factors.

Just 0.6% of the cultures were positive in the review, and it’s likely some of those were caused by contamination. After adjustment for demographics, complex chronic conditions, and severity of illness, culture draws were associated with a 20% increase in hospital length of stay (LOS), hospital costs, and 30-day readmission rates.

“Our data provide more evidence that [routine] blood cultures for children with SSTI represents low-value practice and should be avoided,” said lead investigator John Stephens, MD, a pediatrics professor and hospitalist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Stephens became curious about how common the practice was across hospitals after he and a friend penned an article about the issue for the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do for No Reason” series. The single-center studies they reviewed showed similarly high rates of both testing and negative cultures (J Hosp Med. 2018 Jul;13[7]:496-9).

Dr. Stephens and his team queried the Pediatric Health Information System database for encounters in children aged 2 months to 18 years with the diagnostic code 383, “cellulitis and other skin infections,” from 2012 to 2017, during which time “there really wasn’t a change” in IDSA guidance, he noted. Transfers, encounters with ICU care, and immunocompromised children were excluded.

Hospital admissions were included in the review if they had an additional code for erysipelas, cellulitis, impetigo, or other localized skin infection. The rate of positive cultures was inferred from subsequent codes for bacteremia or septicemia.

Across 49,291 encounters, the median rate of blood culture for skin infection was 51.6%, with tremendous variation between hospitals. With blood cultures, the hospital LOS was about 1.9 days, the hospital cost was $4,030, and the 30-day readmission rate was 1.3%. Without cultures, LOS was 1.6 days, the cost was $3,291, and the readmission rate was 1%.

Although infrequent, it’s likely that positive cultures triggered additional work-up, time in the hospital, and other measures, which might help account for the increase in LOS and costs.

As for why blood testing was so common, especially in some hospitals, “I think it’s just institutional culture. No amount of clinical variation in patient population could explain” a 20%-80% “variation across hospitals. It’s really just ingrained habits,” Dr. Stephens said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

“The rate of positive blood culture was really low, and the association was for higher cost and utilization. I think this really reinforces the IDSA guidelines. We need to focus on quality improvement efforts to do this better,” he said, noting that he hopes to do so at his own institution.

“I’d also like to know more on the positives. In the single center studies, we know more than half of them are contaminants. Often, there’s more contamination than true positives,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Instead of routine blood culture, Dr. Stephens recommended in his article to send pus for a Gram stain and culture and sensitivity, while noting that blood cultures remain reasonable for complicated infections, immunocompromised patients, and neonates.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Stephens didn’t report any disclosures.

SEATTLE – Blood cultures were ordered for over half of pediatric skin infection encounters across 38 children’s hospitals, with rates varying from about 20% to 80% between hospitals, according to a review of almost 50,000 encounters in the Pediatric Health Information System database.

It was a surprising finding, because current guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America do not recommend blood cultures as part of the routine evaluation of uncomplicated pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs), meaning infections in children who are otherwise healthy without neutropenia or other complicating factors.

Just 0.6% of the cultures were positive in the review, and it’s likely some of those were caused by contamination. After adjustment for demographics, complex chronic conditions, and severity of illness, culture draws were associated with a 20% increase in hospital length of stay (LOS), hospital costs, and 30-day readmission rates.

“Our data provide more evidence that [routine] blood cultures for children with SSTI represents low-value practice and should be avoided,” said lead investigator John Stephens, MD, a pediatrics professor and hospitalist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Stephens became curious about how common the practice was across hospitals after he and a friend penned an article about the issue for the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do for No Reason” series. The single-center studies they reviewed showed similarly high rates of both testing and negative cultures (J Hosp Med. 2018 Jul;13[7]:496-9).

Dr. Stephens and his team queried the Pediatric Health Information System database for encounters in children aged 2 months to 18 years with the diagnostic code 383, “cellulitis and other skin infections,” from 2012 to 2017, during which time “there really wasn’t a change” in IDSA guidance, he noted. Transfers, encounters with ICU care, and immunocompromised children were excluded.

Hospital admissions were included in the review if they had an additional code for erysipelas, cellulitis, impetigo, or other localized skin infection. The rate of positive cultures was inferred from subsequent codes for bacteremia or septicemia.

Across 49,291 encounters, the median rate of blood culture for skin infection was 51.6%, with tremendous variation between hospitals. With blood cultures, the hospital LOS was about 1.9 days, the hospital cost was $4,030, and the 30-day readmission rate was 1.3%. Without cultures, LOS was 1.6 days, the cost was $3,291, and the readmission rate was 1%.

Although infrequent, it’s likely that positive cultures triggered additional work-up, time in the hospital, and other measures, which might help account for the increase in LOS and costs.

As for why blood testing was so common, especially in some hospitals, “I think it’s just institutional culture. No amount of clinical variation in patient population could explain” a 20%-80% “variation across hospitals. It’s really just ingrained habits,” Dr. Stephens said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

“The rate of positive blood culture was really low, and the association was for higher cost and utilization. I think this really reinforces the IDSA guidelines. We need to focus on quality improvement efforts to do this better,” he said, noting that he hopes to do so at his own institution.

“I’d also like to know more on the positives. In the single center studies, we know more than half of them are contaminants. Often, there’s more contamination than true positives,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Instead of routine blood culture, Dr. Stephens recommended in his article to send pus for a Gram stain and culture and sensitivity, while noting that blood cultures remain reasonable for complicated infections, immunocompromised patients, and neonates.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Stephens didn’t report any disclosures.

SEATTLE – Blood cultures were ordered for over half of pediatric skin infection encounters across 38 children’s hospitals, with rates varying from about 20% to 80% between hospitals, according to a review of almost 50,000 encounters in the Pediatric Health Information System database.

It was a surprising finding, because current guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America do not recommend blood cultures as part of the routine evaluation of uncomplicated pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs), meaning infections in children who are otherwise healthy without neutropenia or other complicating factors.

Just 0.6% of the cultures were positive in the review, and it’s likely some of those were caused by contamination. After adjustment for demographics, complex chronic conditions, and severity of illness, culture draws were associated with a 20% increase in hospital length of stay (LOS), hospital costs, and 30-day readmission rates.

“Our data provide more evidence that [routine] blood cultures for children with SSTI represents low-value practice and should be avoided,” said lead investigator John Stephens, MD, a pediatrics professor and hospitalist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Stephens became curious about how common the practice was across hospitals after he and a friend penned an article about the issue for the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do for No Reason” series. The single-center studies they reviewed showed similarly high rates of both testing and negative cultures (J Hosp Med. 2018 Jul;13[7]:496-9).

Dr. Stephens and his team queried the Pediatric Health Information System database for encounters in children aged 2 months to 18 years with the diagnostic code 383, “cellulitis and other skin infections,” from 2012 to 2017, during which time “there really wasn’t a change” in IDSA guidance, he noted. Transfers, encounters with ICU care, and immunocompromised children were excluded.

Hospital admissions were included in the review if they had an additional code for erysipelas, cellulitis, impetigo, or other localized skin infection. The rate of positive cultures was inferred from subsequent codes for bacteremia or septicemia.

Across 49,291 encounters, the median rate of blood culture for skin infection was 51.6%, with tremendous variation between hospitals. With blood cultures, the hospital LOS was about 1.9 days, the hospital cost was $4,030, and the 30-day readmission rate was 1.3%. Without cultures, LOS was 1.6 days, the cost was $3,291, and the readmission rate was 1%.

Although infrequent, it’s likely that positive cultures triggered additional work-up, time in the hospital, and other measures, which might help account for the increase in LOS and costs.

As for why blood testing was so common, especially in some hospitals, “I think it’s just institutional culture. No amount of clinical variation in patient population could explain” a 20%-80% “variation across hospitals. It’s really just ingrained habits,” Dr. Stephens said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

“The rate of positive blood culture was really low, and the association was for higher cost and utilization. I think this really reinforces the IDSA guidelines. We need to focus on quality improvement efforts to do this better,” he said, noting that he hopes to do so at his own institution.

“I’d also like to know more on the positives. In the single center studies, we know more than half of them are contaminants. Often, there’s more contamination than true positives,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Instead of routine blood culture, Dr. Stephens recommended in his article to send pus for a Gram stain and culture and sensitivity, while noting that blood cultures remain reasonable for complicated infections, immunocompromised patients, and neonates.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Stephens didn’t report any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

DRC Ebola epidemic continues unabated despite international response

, “currently the outbreak continues at the same pace, so we don’t see evidence of slowing,” according to Henry Walke, MD, director of the Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections and Incident Manager, 2018 CDC Ebola Response, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

He added that new cases of Ebola have been seen in Goma, which is outside the initial outbreak area. Goma is the largest city in the eastern part of the DRC and a major trading port.

Dr. Walke made his remarks in a telephone media briefing Aug. 1 by the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services outlining the current state of the U.S. response to the outbreak.

He described the efforts of the CDC to provide support to the DRC both from Atlanta and in the field. These efforts included support for vaccination activities in DRC’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces for the population and for at-risk health-care workers in the DRC and neighboring countries. In addition, the United States is involved in the testing of experimental therapeutics and vaccines in the DRC in an effort to aid in this and future outbreaks.

“There are no cases of Ebola in the United States,” said Dr. Walke, and the CDC believes the risk to the United States from the outbreak is low. He cited the limited number of travelers from DRC. “There [are] about 16,000 from the DRC to the U.S. on an annual basis, and only about 100 from Goma itself. There aren’t direct flights and we have at the Goma airport both entry and exit screening.”

According to a World Health Organization report, this Ebola outbreak is the second deadliest on record and has killed 1,750 people out of around 2,518 confirmed cases as of July 23.

Efforts to control the epidemic are severely hampered by civil unrest in the area, public mistrust of the government and health care workers, and a comparative lack of international aid compared to previous Ebola outbreaks.

, “currently the outbreak continues at the same pace, so we don’t see evidence of slowing,” according to Henry Walke, MD, director of the Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections and Incident Manager, 2018 CDC Ebola Response, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

He added that new cases of Ebola have been seen in Goma, which is outside the initial outbreak area. Goma is the largest city in the eastern part of the DRC and a major trading port.

Dr. Walke made his remarks in a telephone media briefing Aug. 1 by the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services outlining the current state of the U.S. response to the outbreak.

He described the efforts of the CDC to provide support to the DRC both from Atlanta and in the field. These efforts included support for vaccination activities in DRC’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces for the population and for at-risk health-care workers in the DRC and neighboring countries. In addition, the United States is involved in the testing of experimental therapeutics and vaccines in the DRC in an effort to aid in this and future outbreaks.

“There are no cases of Ebola in the United States,” said Dr. Walke, and the CDC believes the risk to the United States from the outbreak is low. He cited the limited number of travelers from DRC. “There [are] about 16,000 from the DRC to the U.S. on an annual basis, and only about 100 from Goma itself. There aren’t direct flights and we have at the Goma airport both entry and exit screening.”

According to a World Health Organization report, this Ebola outbreak is the second deadliest on record and has killed 1,750 people out of around 2,518 confirmed cases as of July 23.

Efforts to control the epidemic are severely hampered by civil unrest in the area, public mistrust of the government and health care workers, and a comparative lack of international aid compared to previous Ebola outbreaks.

, “currently the outbreak continues at the same pace, so we don’t see evidence of slowing,” according to Henry Walke, MD, director of the Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections and Incident Manager, 2018 CDC Ebola Response, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

He added that new cases of Ebola have been seen in Goma, which is outside the initial outbreak area. Goma is the largest city in the eastern part of the DRC and a major trading port.

Dr. Walke made his remarks in a telephone media briefing Aug. 1 by the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services outlining the current state of the U.S. response to the outbreak.

He described the efforts of the CDC to provide support to the DRC both from Atlanta and in the field. These efforts included support for vaccination activities in DRC’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces for the population and for at-risk health-care workers in the DRC and neighboring countries. In addition, the United States is involved in the testing of experimental therapeutics and vaccines in the DRC in an effort to aid in this and future outbreaks.

“There are no cases of Ebola in the United States,” said Dr. Walke, and the CDC believes the risk to the United States from the outbreak is low. He cited the limited number of travelers from DRC. “There [are] about 16,000 from the DRC to the U.S. on an annual basis, and only about 100 from Goma itself. There aren’t direct flights and we have at the Goma airport both entry and exit screening.”

According to a World Health Organization report, this Ebola outbreak is the second deadliest on record and has killed 1,750 people out of around 2,518 confirmed cases as of July 23.

Efforts to control the epidemic are severely hampered by civil unrest in the area, public mistrust of the government and health care workers, and a comparative lack of international aid compared to previous Ebola outbreaks.

REPORTING FROM A MEDIA BRIEFING BY HHS

Decreasing Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: An Interprofessional Approach to Antibiotic Stewardship

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

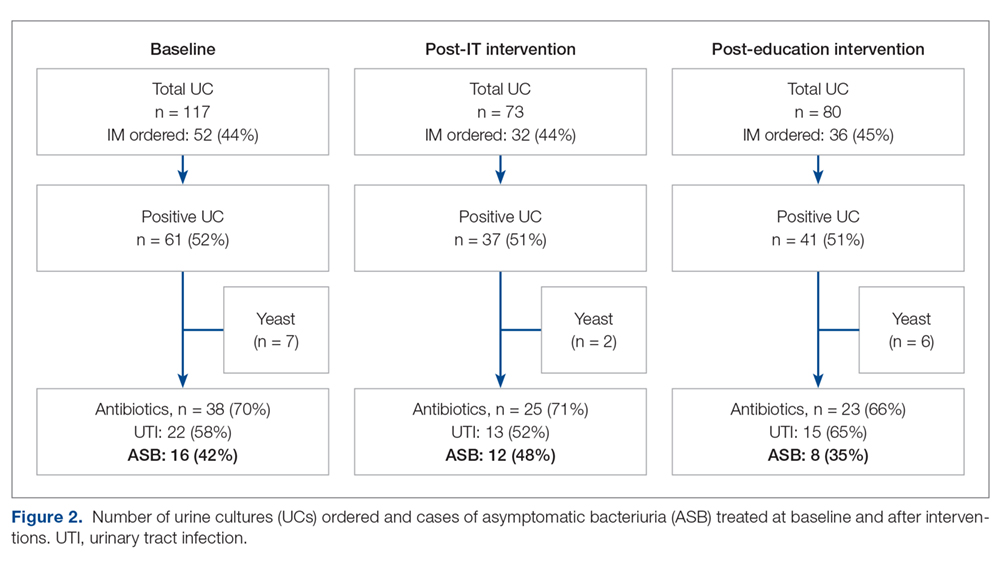

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

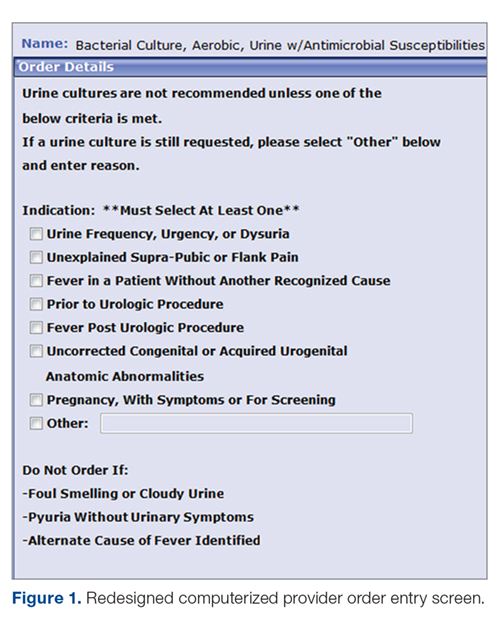

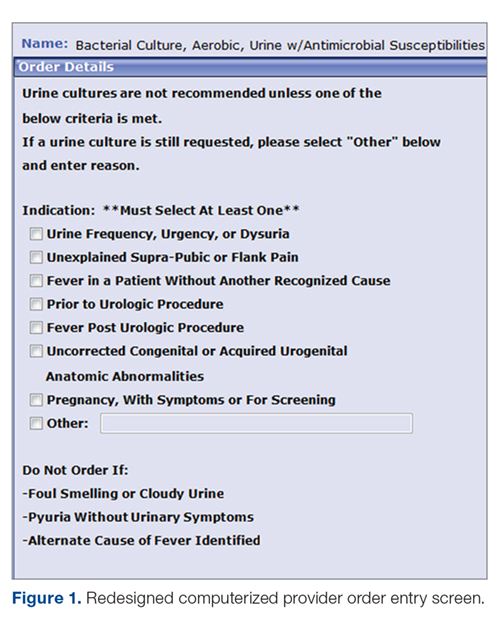

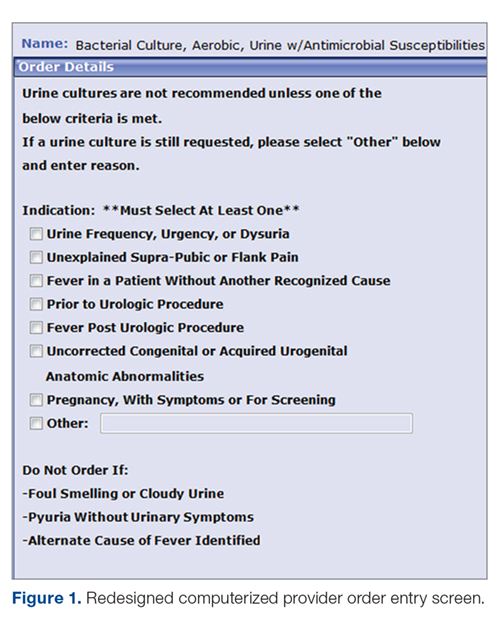

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

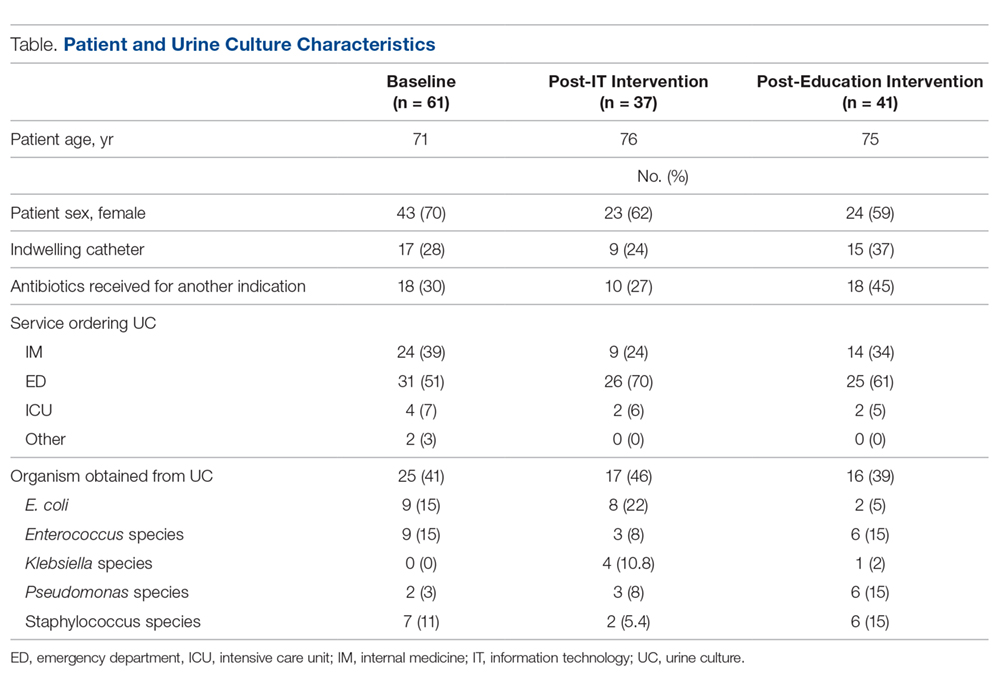

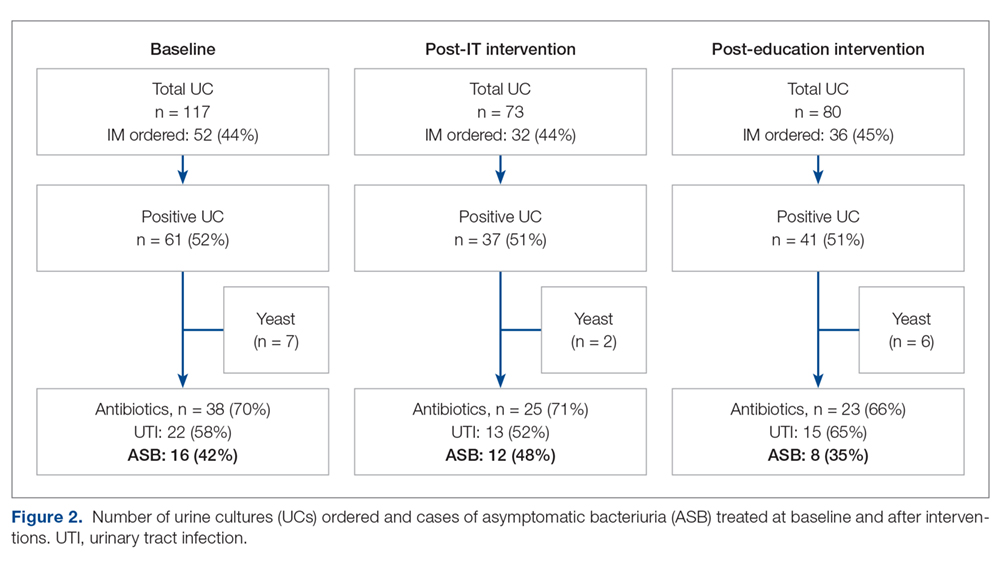

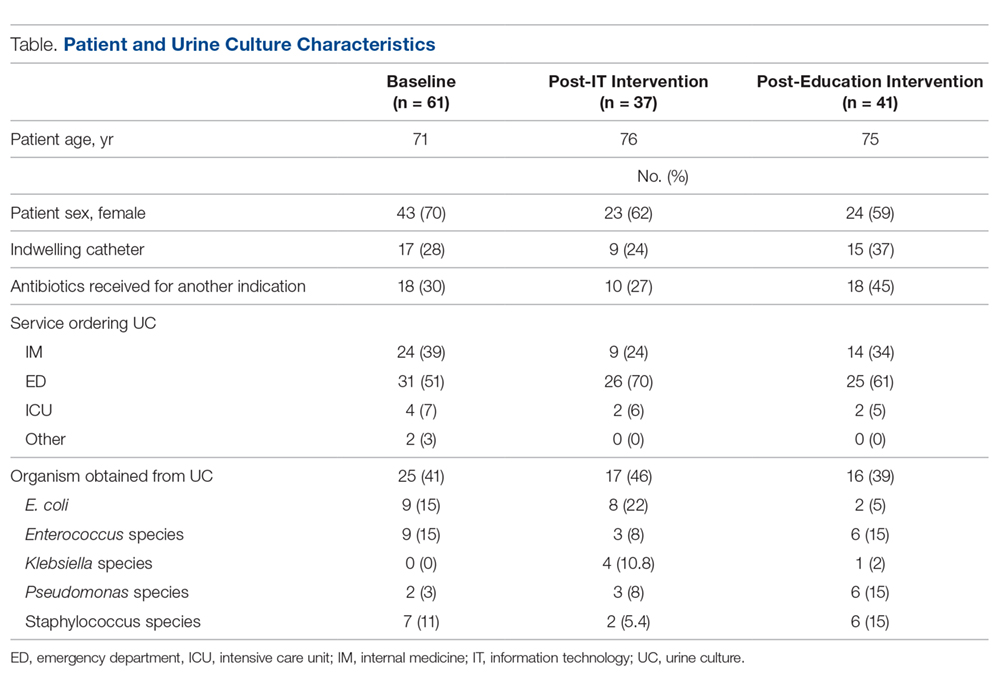

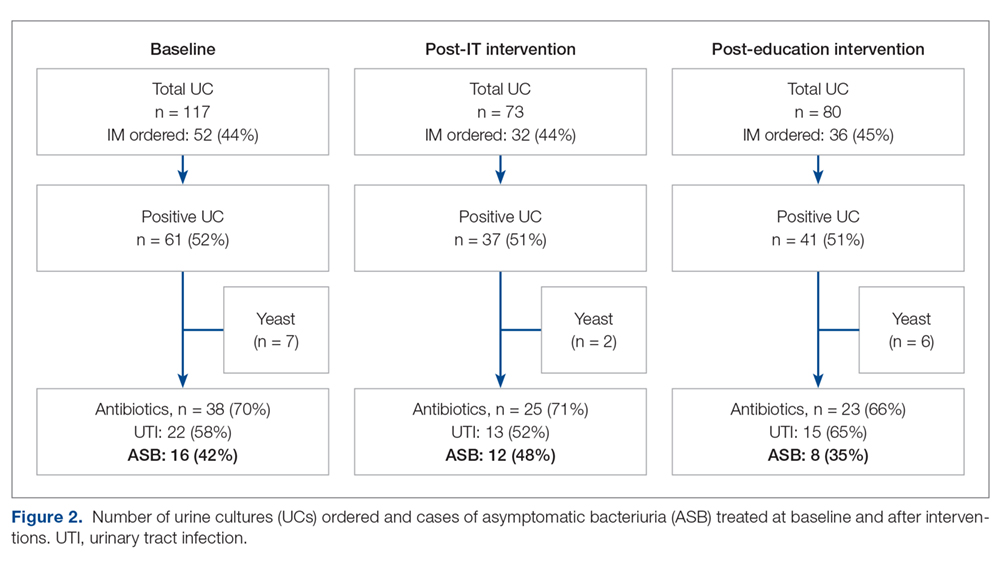

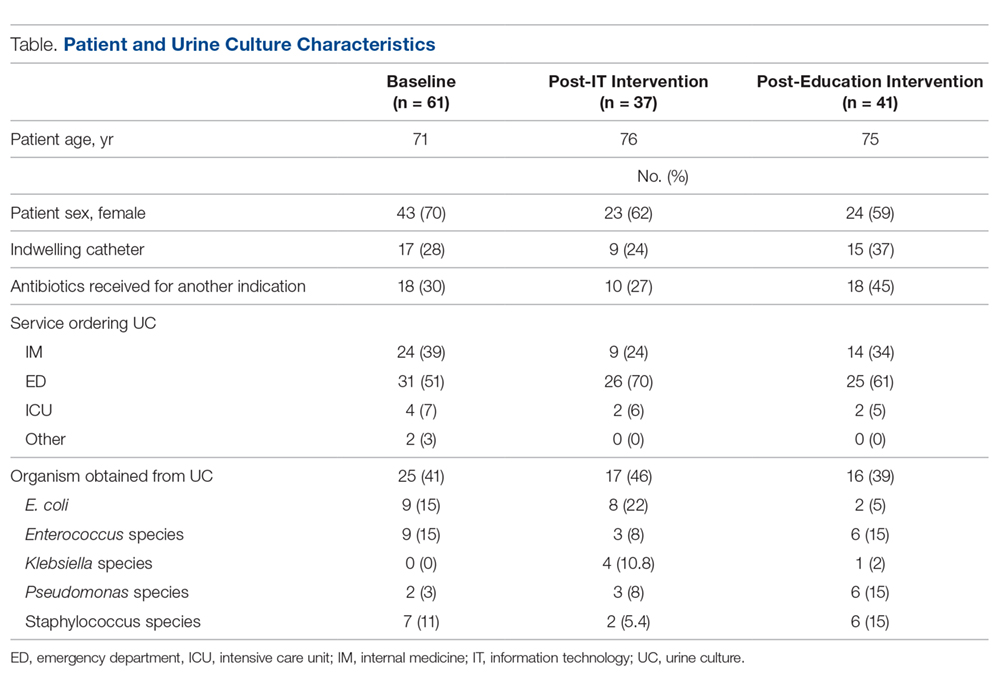

Results

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–75.

2. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1120-1127.

3. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332.

4. Trautner BW. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when the treatment is worse than the disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;9:85-93.

5. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096.

6. The Joint Commission. Prepublication Requirements: New antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jun 22, 2016. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP-CAH_Antimicrobial_Prepub.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2019.

7. Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 16, 2016. CMS-3295-P

8. Hartley SE, Kuhn L, Valley S, et al. Evaluating a hospitalist-based intervention to decrease unnecessary antimicrobial use in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1044-1051.

9. Pavese P, Saurel N, Labarere J, et al. Does an educational session with an infectious diseases physician reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy for inpatients with positive urine culture results? A controlled before-and-after study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:596-599.

10. Kelley D, Aaronson P, Poon E, et al. Evaluation of an antimicrobial stewardship approach to minimize overuse of antibiotics in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:193-195.

11. Chowdhury F, Sarkar K, Branche A, et al. Preventing the inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria at a community teaching hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012;2.

12. Bonnal C, Baune B, Mion M, et al. Bacteriuria in a geriatric hospital: impact of an antibiotic improvement program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:605-609.

13. Linares LA, Thornton DJ, Strymish J, et al. Electronic memorandum decreases unnecessary antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria and culture-negative pyuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:644-648.

14. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, et al. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271-276.

15. Redwood R, Knobloch MJ, Pellegrini DC, et al. Reducing unnecessary culturing: a systems approach to evaluating urine culture ordering and collection practices among nurses in two acute care settings. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:4.

16. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e51–e7.

17. Flokas ME, Andreatos N, Alevizakos M, et al. Inappropriate management of asymptomatic patients with positive urine cultures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:1-10.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

Results

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

Results

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–75.

2. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1120-1127.

3. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332.

4. Trautner BW. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when the treatment is worse than the disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;9:85-93.