User login

Antifungal drug appears safe for pregnancy

Treatment with the according to results from a large registry study in Denmark.

Physicians have been reluctant to prescribe the drug during pregnancy because of the limited safety data. The drug has not been associated with any signs of fetal toxicity in animal studies, but only one study – in 54 pregnancies – has examined the issue in humans and did not identify an increased fetal risk, according to Niklas Worm Andersson, MD, of the department of clinical pharmacology, Copenhagen University Hospital at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, and coauthors.

The retrospective, nationwide cohort study analyzed exposure to oral and tropical terbinafine in a large pregnancy registry and found no increase in the risk of major malformations or spontaneous abortions in exposed versus unexposed pregnancies. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

Still, these results fell short of certainty, the authors noted. “Although our results may provide reassurance for pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine by reporting no overall increased risk of major malformations, we cannot exclude a potential increased risk of a specific malformation,” they wrote.

“To our knowledge, this is by far the largest, most statistically rigorous study in the literature regarding this topic,” Jenny E. Murase, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary Kathryn Abel, a medical student at UCSF, wrote in an accompanying editorial. They described the study as “a substantial contribution to the nearly absent literature regarding the use of terbinafine during pregnancy. Among the antifungal medications, it is possible that terbinafine is the safest one currently available for use in pregnancy, particularly of the oral formulations.”

However, since asymptomatic onychomycosis “is typically a cosmetic, rather than medical, concern, waiting until after pregnancy to initiate therapy is reasonable. ... It is important to acknowledge the uncertainty in this field and question the appropriateness of treating non–life-threatening diseases during pregnancy and lactation,” they wrote.

The Danish researchers drew from a registry of 1,650,649 pregnancies between 1997 and 2016, which included 891 pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine, and 3,174 exposed to topical terbinafine. Matched outcome analyses compared the exposed pregnancies with up to 40,650 controls unexposed during pregnancy.

Propensity-matched comparisons showed no increased risk of major malformations for oral terbinafine exposure versus no exposure (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-1.62) or topical exposure versus no exposure (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.44). There was also no difference in oral versus topical exposure (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.61-2.29).

With respect to spontaneous abortions, there was no significant association with oral terbinafine (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.86-1.32) or topical terbinafine (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.88-1.21), compared with unexposed pregnancies, or oral over topical terbinafine-exposed pregnancies (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.84-1.70).

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted in a Danish population, and the data relied on filled prescriptions for determining exposure, which did not account for adherence. Residual confounding is possible because of the retrospective nature of the study, the authors pointed out.

No source of funding was disclosed. One of the authors has received grants and personal fees from Novartis. Dr. Murase has received fees from Sanofi Genzyme, Dermira, UCB, Regeneron, Ferndale, and UpToDate.

SOURCES: Andersson NW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0142; Murase JE, Abel MK. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.5036.

Treatment with the according to results from a large registry study in Denmark.

Physicians have been reluctant to prescribe the drug during pregnancy because of the limited safety data. The drug has not been associated with any signs of fetal toxicity in animal studies, but only one study – in 54 pregnancies – has examined the issue in humans and did not identify an increased fetal risk, according to Niklas Worm Andersson, MD, of the department of clinical pharmacology, Copenhagen University Hospital at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, and coauthors.

The retrospective, nationwide cohort study analyzed exposure to oral and tropical terbinafine in a large pregnancy registry and found no increase in the risk of major malformations or spontaneous abortions in exposed versus unexposed pregnancies. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

Still, these results fell short of certainty, the authors noted. “Although our results may provide reassurance for pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine by reporting no overall increased risk of major malformations, we cannot exclude a potential increased risk of a specific malformation,” they wrote.

“To our knowledge, this is by far the largest, most statistically rigorous study in the literature regarding this topic,” Jenny E. Murase, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary Kathryn Abel, a medical student at UCSF, wrote in an accompanying editorial. They described the study as “a substantial contribution to the nearly absent literature regarding the use of terbinafine during pregnancy. Among the antifungal medications, it is possible that terbinafine is the safest one currently available for use in pregnancy, particularly of the oral formulations.”

However, since asymptomatic onychomycosis “is typically a cosmetic, rather than medical, concern, waiting until after pregnancy to initiate therapy is reasonable. ... It is important to acknowledge the uncertainty in this field and question the appropriateness of treating non–life-threatening diseases during pregnancy and lactation,” they wrote.

The Danish researchers drew from a registry of 1,650,649 pregnancies between 1997 and 2016, which included 891 pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine, and 3,174 exposed to topical terbinafine. Matched outcome analyses compared the exposed pregnancies with up to 40,650 controls unexposed during pregnancy.

Propensity-matched comparisons showed no increased risk of major malformations for oral terbinafine exposure versus no exposure (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-1.62) or topical exposure versus no exposure (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.44). There was also no difference in oral versus topical exposure (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.61-2.29).

With respect to spontaneous abortions, there was no significant association with oral terbinafine (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.86-1.32) or topical terbinafine (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.88-1.21), compared with unexposed pregnancies, or oral over topical terbinafine-exposed pregnancies (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.84-1.70).

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted in a Danish population, and the data relied on filled prescriptions for determining exposure, which did not account for adherence. Residual confounding is possible because of the retrospective nature of the study, the authors pointed out.

No source of funding was disclosed. One of the authors has received grants and personal fees from Novartis. Dr. Murase has received fees from Sanofi Genzyme, Dermira, UCB, Regeneron, Ferndale, and UpToDate.

SOURCES: Andersson NW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0142; Murase JE, Abel MK. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.5036.

Treatment with the according to results from a large registry study in Denmark.

Physicians have been reluctant to prescribe the drug during pregnancy because of the limited safety data. The drug has not been associated with any signs of fetal toxicity in animal studies, but only one study – in 54 pregnancies – has examined the issue in humans and did not identify an increased fetal risk, according to Niklas Worm Andersson, MD, of the department of clinical pharmacology, Copenhagen University Hospital at Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg, and coauthors.

The retrospective, nationwide cohort study analyzed exposure to oral and tropical terbinafine in a large pregnancy registry and found no increase in the risk of major malformations or spontaneous abortions in exposed versus unexposed pregnancies. The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

Still, these results fell short of certainty, the authors noted. “Although our results may provide reassurance for pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine by reporting no overall increased risk of major malformations, we cannot exclude a potential increased risk of a specific malformation,” they wrote.

“To our knowledge, this is by far the largest, most statistically rigorous study in the literature regarding this topic,” Jenny E. Murase, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and Mary Kathryn Abel, a medical student at UCSF, wrote in an accompanying editorial. They described the study as “a substantial contribution to the nearly absent literature regarding the use of terbinafine during pregnancy. Among the antifungal medications, it is possible that terbinafine is the safest one currently available for use in pregnancy, particularly of the oral formulations.”

However, since asymptomatic onychomycosis “is typically a cosmetic, rather than medical, concern, waiting until after pregnancy to initiate therapy is reasonable. ... It is important to acknowledge the uncertainty in this field and question the appropriateness of treating non–life-threatening diseases during pregnancy and lactation,” they wrote.

The Danish researchers drew from a registry of 1,650,649 pregnancies between 1997 and 2016, which included 891 pregnancies exposed to oral terbinafine, and 3,174 exposed to topical terbinafine. Matched outcome analyses compared the exposed pregnancies with up to 40,650 controls unexposed during pregnancy.

Propensity-matched comparisons showed no increased risk of major malformations for oral terbinafine exposure versus no exposure (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-1.62) or topical exposure versus no exposure (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.81-1.44). There was also no difference in oral versus topical exposure (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.61-2.29).

With respect to spontaneous abortions, there was no significant association with oral terbinafine (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.86-1.32) or topical terbinafine (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.88-1.21), compared with unexposed pregnancies, or oral over topical terbinafine-exposed pregnancies (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.84-1.70).

The study is limited by the fact that it was conducted in a Danish population, and the data relied on filled prescriptions for determining exposure, which did not account for adherence. Residual confounding is possible because of the retrospective nature of the study, the authors pointed out.

No source of funding was disclosed. One of the authors has received grants and personal fees from Novartis. Dr. Murase has received fees from Sanofi Genzyme, Dermira, UCB, Regeneron, Ferndale, and UpToDate.

SOURCES: Andersson NW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0142; Murase JE, Abel MK. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.5036.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

HIV free 30 months after stem cell transplant, is the London patient cured?

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

FROM CROI 2020

Testosterone therapy linked to CV risk in men with HIV

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

Men with HIV are likely prone to the same cardiovascular risks from testosterone therapy as other men, according to new research.

There’s no reason to think they weren’t, but it hadn’t been demonstrated until now, and men with HIV are already at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. The take-home message is that “it would be prudent for clinicians to monitor closely for cardiovascular risk factors and recommend intervention to lower cardiovascular risk among men with HIV on or considering testosterone therapy,” lead investigator Sabina Haberlen, PhD, an assistant scientist in the infectious disease epidemiology division of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in a poster that was presented as part of the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Testosterone therapy is common among middle-aged and older men with HIV to counter the hypogonadism associated with infection. The investigators turned to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study – a 30-year, four-city study of HIV-1 infection in men who have sex with men – to gauge its effect.

The 300 men in the study had a baseline coronary CT angiogram in 2010-2013 and a repeat study a mean of 4.5 years later. They had no history of coronary interventions or kidney dysfunction at baseline and were aged 40-70 years, with a median age of 51 years. About 70% reported never using testosterone, 8% were former users before entering the study, 7% started using testosterone between the two CTs, and 15% entered the study on testosterone and stayed on it.

Adjusting for age, race, cardiovascular risk factors, baseline serum testosterone levels, and other potential confounders, the risk of significant coronary artery calcium (CAC) progression was 2 times greater among continuous users (P = .03) and 2.4 times greater among new users (P = .01), compared with former users, who the investigators used as a control group because, at some point, they too had indications for testosterone replacement and so were more medically similar than never users.

The risk of noncalcified plaque volume progression was also more than twice as high among ongoing users, and elevated, although not significantly so, among ongoing users.

In short, “our findings are similar to those on subclinical atherosclerotic progression” in trials of older men in the general population on testosterone replacement, Dr. Haberlen said.

About half the subjects were white, 41% were at high risk for cardiovascular disease, 91% were on antiretroviral therapy, and 81% had undetectable HIV viral loads. Median total testosterone was 606 ng/dL. CAC progression was defined by incident CAC, at least a 10 Agatston unit/year increase if the baseline CAC score was 1-100, and a 10% or more annual increase if the baseline score was above 100.

Lower baseline serum testosterone was also associated with an increased risk of CAC progression, although not progression of noncalcified plaques.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Haberlen didn’t report any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Haberlen S et al. CROI 2020, Abstract 662.

FROM CROI 2020

Descovy safety no match for cost savings with generic Truvada, study says

Economically, the modest safety benefit of tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (Descovy) for HIV preexposure prophylaxis won’t justify paying thousands of dollars more for it when tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (Truvada) becomes available as a generic in a year or so, according to a population level cost-effectiveness analysis presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers held a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Those benefits will translate to a health savings worth only a few hundred dollars over the likely generic price, said investigators led by Rochelle Walensky, MD, and infectious disease physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

In a press statement, Gilead, which makes both medications, said it “strongly believes that the analysis ... is flawed, leading to inaccurate conclusions that severely underestimate the value of Descovy. The method and validation of the models, incomplete clinical data analyzed and the assumptions around potential pricing associated with a generic alternative to Truvada ... are inadequate to enable a sufficiently robust analysis.”

The company did not go into details about what exactly might have been off about the analysis.

Approved in Oct. 2019, tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (also known as F/TAF) is the first new option for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) since tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (F/TDF) was approved in 2012; F/TDF is going off patent soon.

Amid a robust marketing campaign, the new medication has already captured 25% of the PrEP market, and Gilead expects up to 45% of patients to switch to F/TAF before generic F/TDF becomes available.

That worries the investigators. “At the current FSS [Federal Supply Schedule] price of $16,600 per year,” a nationwide PrEP program that uses F/TAF “would consume the entire $900.8 million federal budget for HIV prevention several times over ... If branded F/TAF drives out generic F/TDF,” rates of PrEP coverage “could decrease, and F/TAF could end up causing more avoidable HIV transmissions” than it prevents. “Given the very small, albeit statistically significant, differences in surrogate [safety] markers, without evidence of clinical significance, there is no urgency and no reason to switch PrEP regimens now,” they said. Both medications were equally effective in preventing HIV transmission in Gilead’s head-to-head phase 3 trial, but there was an a mean of about a 4 mL/min difference in estimated glomerular filtration rate at week 48 and about a 2% difference in hip and spine density at week 96, both favoring F/TAF. Marketing highlights those differences.

The investigators wanted to see how much they are worth, so they estimated savings from a possibly lower rate of bone fractures and renal failure with F/TAF and juxtaposed it with its cost and the anticipated cost of generic F/TDF at half-price, $8,300/patient-year.

They gave F/TAF the benefit of the doubt, skewing their model toward maximal harm and cost from F/TDF toxicity, and omitting the cost of increased lipid levels, weight gain, and other possible F/TAF adverse events.

In the end, they concluded that “the improved safety of F/TAF is worth no more than an additional $370 per person per year” over generic F/TDF based on toxicity differences. “

The team calculated that F/TAF would prevent a maximum of 2,101 fractures and 25 cases of end-stage renal disease among 123,610 U.S. men who have sex with men treated for 5 years. That translated to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of more than $7 million per quality-adjusted life-year, far above the $100,000 threshold considered acceptable in the United States.

“In the presence of a generic alternative, the current price of F/TAF would have to be reduced by over $7,900/year for F/TAF to satisfy generally accepted standards of societal value. If F/TDF can achieve the 75% price reduction that is commonly observed when generic competition ensues (that is, a cost of $4,150/year), the F/TAF price would need to be no higher than $4,520 to demonstrate value on the basis of cost-effectiveness,” the investigators said.

For older patients at unusually high risk for renal disease or bone-related adverse events, the switch from F/TDF to F/TAF would have greater clinical effect and benefit. Even in this population, however, it would be difficult to defend a price greater than $800 over the cost of the generic alternative,” they said.

“The message seems clear that the current cost of F/TAF does not justify wholesale conversion to F/TAF as the first-line agent for all PrEP-eligible patients,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, and Wendy Armstrong, MD, infectious disease professors at Emory University, Atlanta, in an editorial. “For PrEP-eligible persons at low risk for fracture and renal disease, it is very hard to justify use of F/TAF knowing that F/TDF will soon be generic” (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M20-0799).

“Successful PrEP scale-up in other countries was made possible by drug costs that are less than $100/month in most countries. In the United States, without drastic reductions in the cost of PrEP, which may be achievable with generic F/TDF ... we will fail to avert otherwise preventable new HIV transmissions,” they said.

The study was simultaneously published online (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478).

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Massachusetts General Hospital. The investigators and editorialists didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCE: Walensky RP et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478.

Economically, the modest safety benefit of tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (Descovy) for HIV preexposure prophylaxis won’t justify paying thousands of dollars more for it when tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (Truvada) becomes available as a generic in a year or so, according to a population level cost-effectiveness analysis presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers held a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Those benefits will translate to a health savings worth only a few hundred dollars over the likely generic price, said investigators led by Rochelle Walensky, MD, and infectious disease physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

In a press statement, Gilead, which makes both medications, said it “strongly believes that the analysis ... is flawed, leading to inaccurate conclusions that severely underestimate the value of Descovy. The method and validation of the models, incomplete clinical data analyzed and the assumptions around potential pricing associated with a generic alternative to Truvada ... are inadequate to enable a sufficiently robust analysis.”

The company did not go into details about what exactly might have been off about the analysis.

Approved in Oct. 2019, tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (also known as F/TAF) is the first new option for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) since tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (F/TDF) was approved in 2012; F/TDF is going off patent soon.

Amid a robust marketing campaign, the new medication has already captured 25% of the PrEP market, and Gilead expects up to 45% of patients to switch to F/TAF before generic F/TDF becomes available.

That worries the investigators. “At the current FSS [Federal Supply Schedule] price of $16,600 per year,” a nationwide PrEP program that uses F/TAF “would consume the entire $900.8 million federal budget for HIV prevention several times over ... If branded F/TAF drives out generic F/TDF,” rates of PrEP coverage “could decrease, and F/TAF could end up causing more avoidable HIV transmissions” than it prevents. “Given the very small, albeit statistically significant, differences in surrogate [safety] markers, without evidence of clinical significance, there is no urgency and no reason to switch PrEP regimens now,” they said. Both medications were equally effective in preventing HIV transmission in Gilead’s head-to-head phase 3 trial, but there was an a mean of about a 4 mL/min difference in estimated glomerular filtration rate at week 48 and about a 2% difference in hip and spine density at week 96, both favoring F/TAF. Marketing highlights those differences.

The investigators wanted to see how much they are worth, so they estimated savings from a possibly lower rate of bone fractures and renal failure with F/TAF and juxtaposed it with its cost and the anticipated cost of generic F/TDF at half-price, $8,300/patient-year.

They gave F/TAF the benefit of the doubt, skewing their model toward maximal harm and cost from F/TDF toxicity, and omitting the cost of increased lipid levels, weight gain, and other possible F/TAF adverse events.

In the end, they concluded that “the improved safety of F/TAF is worth no more than an additional $370 per person per year” over generic F/TDF based on toxicity differences. “

The team calculated that F/TAF would prevent a maximum of 2,101 fractures and 25 cases of end-stage renal disease among 123,610 U.S. men who have sex with men treated for 5 years. That translated to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of more than $7 million per quality-adjusted life-year, far above the $100,000 threshold considered acceptable in the United States.

“In the presence of a generic alternative, the current price of F/TAF would have to be reduced by over $7,900/year for F/TAF to satisfy generally accepted standards of societal value. If F/TDF can achieve the 75% price reduction that is commonly observed when generic competition ensues (that is, a cost of $4,150/year), the F/TAF price would need to be no higher than $4,520 to demonstrate value on the basis of cost-effectiveness,” the investigators said.

For older patients at unusually high risk for renal disease or bone-related adverse events, the switch from F/TDF to F/TAF would have greater clinical effect and benefit. Even in this population, however, it would be difficult to defend a price greater than $800 over the cost of the generic alternative,” they said.

“The message seems clear that the current cost of F/TAF does not justify wholesale conversion to F/TAF as the first-line agent for all PrEP-eligible patients,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, and Wendy Armstrong, MD, infectious disease professors at Emory University, Atlanta, in an editorial. “For PrEP-eligible persons at low risk for fracture and renal disease, it is very hard to justify use of F/TAF knowing that F/TDF will soon be generic” (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M20-0799).

“Successful PrEP scale-up in other countries was made possible by drug costs that are less than $100/month in most countries. In the United States, without drastic reductions in the cost of PrEP, which may be achievable with generic F/TDF ... we will fail to avert otherwise preventable new HIV transmissions,” they said.

The study was simultaneously published online (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478).

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Massachusetts General Hospital. The investigators and editorialists didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCE: Walensky RP et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478.

Economically, the modest safety benefit of tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (Descovy) for HIV preexposure prophylaxis won’t justify paying thousands of dollars more for it when tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (Truvada) becomes available as a generic in a year or so, according to a population level cost-effectiveness analysis presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers held a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

Those benefits will translate to a health savings worth only a few hundred dollars over the likely generic price, said investigators led by Rochelle Walensky, MD, and infectious disease physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

In a press statement, Gilead, which makes both medications, said it “strongly believes that the analysis ... is flawed, leading to inaccurate conclusions that severely underestimate the value of Descovy. The method and validation of the models, incomplete clinical data analyzed and the assumptions around potential pricing associated with a generic alternative to Truvada ... are inadequate to enable a sufficiently robust analysis.”

The company did not go into details about what exactly might have been off about the analysis.

Approved in Oct. 2019, tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine (also known as F/TAF) is the first new option for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) since tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine (F/TDF) was approved in 2012; F/TDF is going off patent soon.

Amid a robust marketing campaign, the new medication has already captured 25% of the PrEP market, and Gilead expects up to 45% of patients to switch to F/TAF before generic F/TDF becomes available.

That worries the investigators. “At the current FSS [Federal Supply Schedule] price of $16,600 per year,” a nationwide PrEP program that uses F/TAF “would consume the entire $900.8 million federal budget for HIV prevention several times over ... If branded F/TAF drives out generic F/TDF,” rates of PrEP coverage “could decrease, and F/TAF could end up causing more avoidable HIV transmissions” than it prevents. “Given the very small, albeit statistically significant, differences in surrogate [safety] markers, without evidence of clinical significance, there is no urgency and no reason to switch PrEP regimens now,” they said. Both medications were equally effective in preventing HIV transmission in Gilead’s head-to-head phase 3 trial, but there was an a mean of about a 4 mL/min difference in estimated glomerular filtration rate at week 48 and about a 2% difference in hip and spine density at week 96, both favoring F/TAF. Marketing highlights those differences.

The investigators wanted to see how much they are worth, so they estimated savings from a possibly lower rate of bone fractures and renal failure with F/TAF and juxtaposed it with its cost and the anticipated cost of generic F/TDF at half-price, $8,300/patient-year.

They gave F/TAF the benefit of the doubt, skewing their model toward maximal harm and cost from F/TDF toxicity, and omitting the cost of increased lipid levels, weight gain, and other possible F/TAF adverse events.

In the end, they concluded that “the improved safety of F/TAF is worth no more than an additional $370 per person per year” over generic F/TDF based on toxicity differences. “

The team calculated that F/TAF would prevent a maximum of 2,101 fractures and 25 cases of end-stage renal disease among 123,610 U.S. men who have sex with men treated for 5 years. That translated to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of more than $7 million per quality-adjusted life-year, far above the $100,000 threshold considered acceptable in the United States.

“In the presence of a generic alternative, the current price of F/TAF would have to be reduced by over $7,900/year for F/TAF to satisfy generally accepted standards of societal value. If F/TDF can achieve the 75% price reduction that is commonly observed when generic competition ensues (that is, a cost of $4,150/year), the F/TAF price would need to be no higher than $4,520 to demonstrate value on the basis of cost-effectiveness,” the investigators said.

For older patients at unusually high risk for renal disease or bone-related adverse events, the switch from F/TDF to F/TAF would have greater clinical effect and benefit. Even in this population, however, it would be difficult to defend a price greater than $800 over the cost of the generic alternative,” they said.

“The message seems clear that the current cost of F/TAF does not justify wholesale conversion to F/TAF as the first-line agent for all PrEP-eligible patients,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, and Wendy Armstrong, MD, infectious disease professors at Emory University, Atlanta, in an editorial. “For PrEP-eligible persons at low risk for fracture and renal disease, it is very hard to justify use of F/TAF knowing that F/TDF will soon be generic” (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M20-0799).

“Successful PrEP scale-up in other countries was made possible by drug costs that are less than $100/month in most countries. In the United States, without drastic reductions in the cost of PrEP, which may be achievable with generic F/TDF ... we will fail to avert otherwise preventable new HIV transmissions,” they said.

The study was simultaneously published online (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478).

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Massachusetts General Hospital. The investigators and editorialists didn’t have any industry disclosures.

SOURCE: Walensky RP et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.7326/M19-3478.

FROM CROI 2020

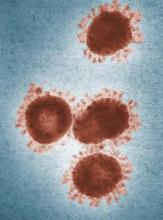

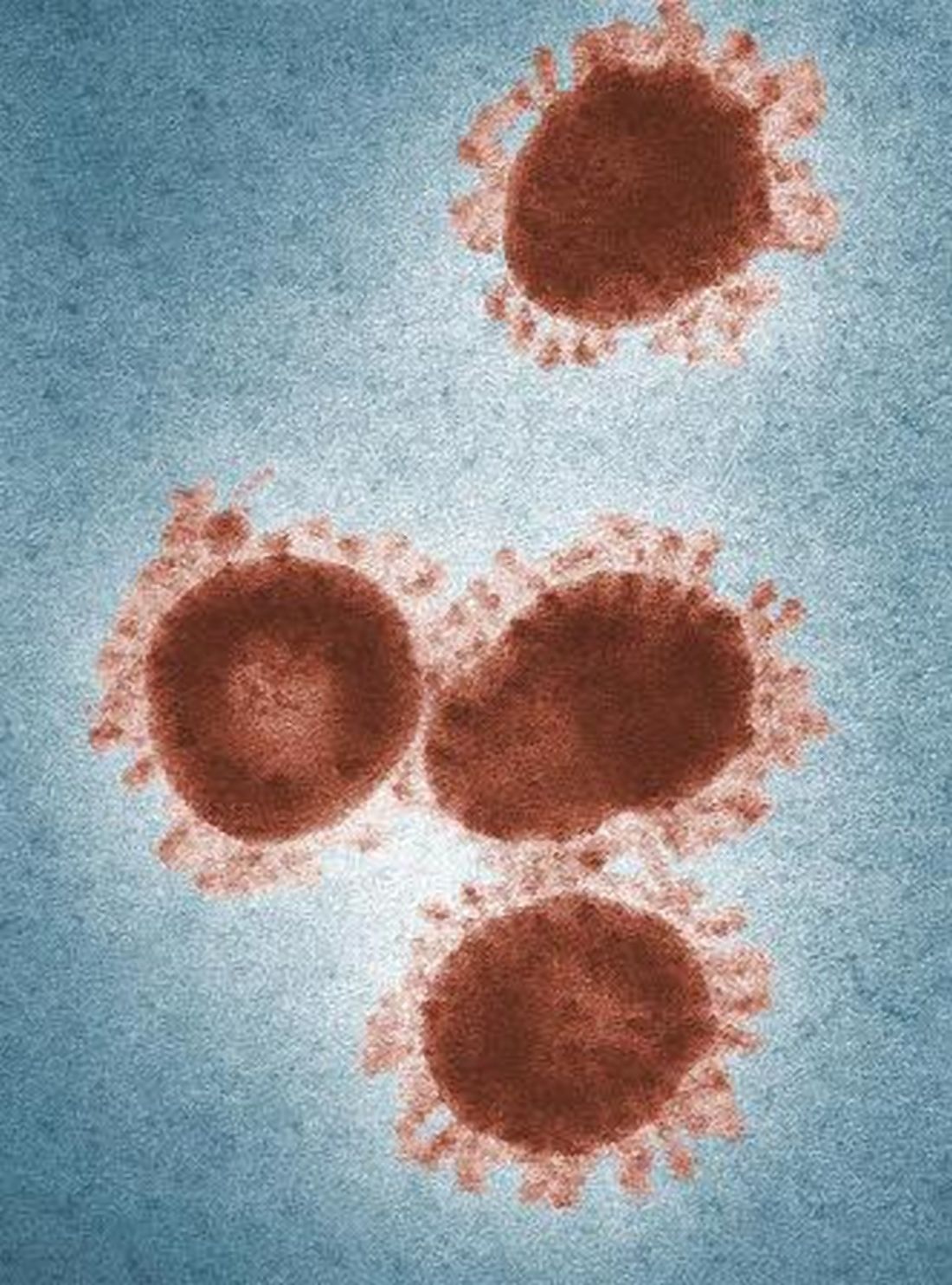

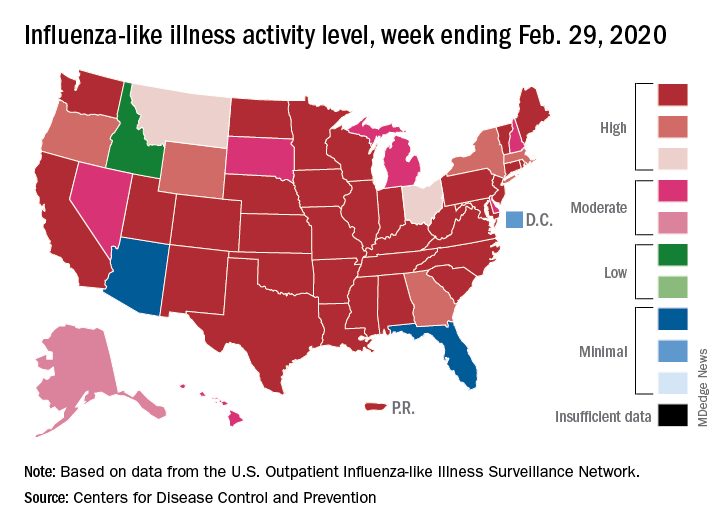

Some infected patients could show COVID-19 symptoms after quarantine

Although a 14-day quarantine after exposure to novel coronavirus is “well supported” by evidence, some infected individuals will not become symptomatic until after that period, according to authors of a recent analysis published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Most individuals infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) will develop symptoms by day 12 of the infection, which is within the 14-day period of active monitoring currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the authors wrote.

However, an estimated 101 out of 10,000 cases could become symptomatic after the end of that 14-day monitoring period, they cautioned.

“Our analyses do not preclude that estimate from being higher,” said the investigators, led by Stephen A. Lauer, PhD, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

The analysis, based on 181 confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that were documented outside of the outbreak epicenter, Wuhan, China, makes “more conservative assumptions” about the window of symptom onset and potential for continued exposure, compared with analyses in previous studies, the researchers wrote.

The estimated incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 in the 181-patient study was a median of 5.1 days, which is comparable with previous estimates based on COVID-19 cases outside of Wuhan and consistent with other known human coronavirus diseases, such as SARS, which had a reported mean incubation period of 5 days, Dr. Lauer and colleagues noted.

Symptoms developed within 11.5 days for 97.5% of patients in the study.

Whether it’s acceptable to have 101 out of 10,000 cases becoming symptomatic beyond the recommended quarantine window depends on two factors, according to the authors. The first is the expected infection risk in the population that is being monitored, and the second is “judgment about the cost of missing cases,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Aaron Eli Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, N.Y., said that in practical terms, the results suggest that the majority of patients with COVID-19 will be identified within 14 days, with an “outside chance” of an infected individual leaving quarantine and transmitting virus for a short period of time before becoming symptomatic.

“I think the proper message to give those patients [who are asymptomatic upon leaving quarantine] is, ‘after 14 days, we’re pretty sure you’re out of the woods, but should you get any symptoms, immediately requarantine yourself and seek medical care,” he said.

Study coauthor Kyra H. Grantz, a doctoral graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that extending a quarantine beyond 14 days might be considered in the highest-risk scenarios, though the benefits of doing so would have to be weighed against the costs to public health and to the individuals under quarantine.

“Our estimate of the incubation period definitely supports the 14-day recommendation that the CDC has been using,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Grantz emphasized that the estimate of 101 out of 10,000 cases developing symptoms after day 14 of active monitoring – representing the 99th percentile of cases – assumes the “most conservative, worst-case scenario” in a population that is fully infected.

“If you’re looking at a following a cohort of 1,000 people whom you think may have been exposed, only a certain percentage will be infected, and only a certain percentage of those will even develop symptoms – before we get to this idea of how many people would we miss,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Four authors reported disclosures related to those entities, and the remaining five reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lauer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 9. doi:10.1101/2020.02.02.20020016.

Although a 14-day quarantine after exposure to novel coronavirus is “well supported” by evidence, some infected individuals will not become symptomatic until after that period, according to authors of a recent analysis published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Most individuals infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) will develop symptoms by day 12 of the infection, which is within the 14-day period of active monitoring currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the authors wrote.

However, an estimated 101 out of 10,000 cases could become symptomatic after the end of that 14-day monitoring period, they cautioned.

“Our analyses do not preclude that estimate from being higher,” said the investigators, led by Stephen A. Lauer, PhD, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

The analysis, based on 181 confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that were documented outside of the outbreak epicenter, Wuhan, China, makes “more conservative assumptions” about the window of symptom onset and potential for continued exposure, compared with analyses in previous studies, the researchers wrote.

The estimated incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 in the 181-patient study was a median of 5.1 days, which is comparable with previous estimates based on COVID-19 cases outside of Wuhan and consistent with other known human coronavirus diseases, such as SARS, which had a reported mean incubation period of 5 days, Dr. Lauer and colleagues noted.

Symptoms developed within 11.5 days for 97.5% of patients in the study.

Whether it’s acceptable to have 101 out of 10,000 cases becoming symptomatic beyond the recommended quarantine window depends on two factors, according to the authors. The first is the expected infection risk in the population that is being monitored, and the second is “judgment about the cost of missing cases,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Aaron Eli Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, N.Y., said that in practical terms, the results suggest that the majority of patients with COVID-19 will be identified within 14 days, with an “outside chance” of an infected individual leaving quarantine and transmitting virus for a short period of time before becoming symptomatic.

“I think the proper message to give those patients [who are asymptomatic upon leaving quarantine] is, ‘after 14 days, we’re pretty sure you’re out of the woods, but should you get any symptoms, immediately requarantine yourself and seek medical care,” he said.

Study coauthor Kyra H. Grantz, a doctoral graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that extending a quarantine beyond 14 days might be considered in the highest-risk scenarios, though the benefits of doing so would have to be weighed against the costs to public health and to the individuals under quarantine.

“Our estimate of the incubation period definitely supports the 14-day recommendation that the CDC has been using,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Grantz emphasized that the estimate of 101 out of 10,000 cases developing symptoms after day 14 of active monitoring – representing the 99th percentile of cases – assumes the “most conservative, worst-case scenario” in a population that is fully infected.

“If you’re looking at a following a cohort of 1,000 people whom you think may have been exposed, only a certain percentage will be infected, and only a certain percentage of those will even develop symptoms – before we get to this idea of how many people would we miss,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Four authors reported disclosures related to those entities, and the remaining five reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lauer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 9. doi:10.1101/2020.02.02.20020016.

Although a 14-day quarantine after exposure to novel coronavirus is “well supported” by evidence, some infected individuals will not become symptomatic until after that period, according to authors of a recent analysis published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Most individuals infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) will develop symptoms by day 12 of the infection, which is within the 14-day period of active monitoring currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the authors wrote.

However, an estimated 101 out of 10,000 cases could become symptomatic after the end of that 14-day monitoring period, they cautioned.

“Our analyses do not preclude that estimate from being higher,” said the investigators, led by Stephen A. Lauer, PhD, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore.

The analysis, based on 181 confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that were documented outside of the outbreak epicenter, Wuhan, China, makes “more conservative assumptions” about the window of symptom onset and potential for continued exposure, compared with analyses in previous studies, the researchers wrote.

The estimated incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 in the 181-patient study was a median of 5.1 days, which is comparable with previous estimates based on COVID-19 cases outside of Wuhan and consistent with other known human coronavirus diseases, such as SARS, which had a reported mean incubation period of 5 days, Dr. Lauer and colleagues noted.

Symptoms developed within 11.5 days for 97.5% of patients in the study.

Whether it’s acceptable to have 101 out of 10,000 cases becoming symptomatic beyond the recommended quarantine window depends on two factors, according to the authors. The first is the expected infection risk in the population that is being monitored, and the second is “judgment about the cost of missing cases,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Aaron Eli Glatt, MD, chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, N.Y., said that in practical terms, the results suggest that the majority of patients with COVID-19 will be identified within 14 days, with an “outside chance” of an infected individual leaving quarantine and transmitting virus for a short period of time before becoming symptomatic.

“I think the proper message to give those patients [who are asymptomatic upon leaving quarantine] is, ‘after 14 days, we’re pretty sure you’re out of the woods, but should you get any symptoms, immediately requarantine yourself and seek medical care,” he said.

Study coauthor Kyra H. Grantz, a doctoral graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that extending a quarantine beyond 14 days might be considered in the highest-risk scenarios, though the benefits of doing so would have to be weighed against the costs to public health and to the individuals under quarantine.

“Our estimate of the incubation period definitely supports the 14-day recommendation that the CDC has been using,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Grantz emphasized that the estimate of 101 out of 10,000 cases developing symptoms after day 14 of active monitoring – representing the 99th percentile of cases – assumes the “most conservative, worst-case scenario” in a population that is fully infected.

“If you’re looking at a following a cohort of 1,000 people whom you think may have been exposed, only a certain percentage will be infected, and only a certain percentage of those will even develop symptoms – before we get to this idea of how many people would we miss,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Four authors reported disclosures related to those entities, and the remaining five reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lauer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 9. doi:10.1101/2020.02.02.20020016.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Some individuals who are infected with the novel coronavirus could become symptomatic after the active 14-day quarantine period.

Major finding: The median incubation period was 5.1 days, with 97.5% of patients developing symptoms within 11.5 days, implying that 101 of every 10,000 cases (99th percentile) would develop symptoms beyond the quarantine period.

Study details: Analysis of 181 confirmed COVID-19 cases identified outside of the outbreak epicenter, Wuhan, China.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Four authors reported disclosures related to those entities, and the remaining five reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lauer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 9. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.02.20020016.

Rotavirus vaccination is not a risk factor for type 1 diabetes

published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Previous findings from a number of studies have indicated a possible association between rotavirus and type 1 diabetes, according to Jason M. Glanz, PhD, and colleagues. “Epidemiologic data suggest an association between gastrointestinal infection and incidence of type 1 diabetes in children followed from birth to age 10 years. Given these findings, it is biologically plausible that live, attenuated rotavirus vaccine could either increase or decrease the risk for type 1 diabetes in early childhood,” they wrote.

To examine the association between rotavirus vaccination and the incidence of type 1 diabetes in a cohort of U.S. children, Dr. Glanz, a senior investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institute for Health Research in Aurora, and colleagues retrospectively analyzed data from seven health care organizations that participate in the Vaccine Safety Datalink.

The researchers identified children born between 2006 and 2014 who had continuous enrollment from age 6 weeks to 2 years. They excluded children with a medical contraindication to vaccination or fewer than two well-child visits by age 12 months. They followed children until a type 1 diabetes diagnosis, disenrollment, or Dec. 31, 2017. The researchers adjusted for sex, birth year, mother’s age, birth weight, gestational age, and race or ethnicity.

The cohort included 386,937 children who were followed up a median of 5.4 years for a total person-time follow-up of 2,253,879 years. In all, 386,937 children (93.1%) were fully exposed to rotavirus vaccination; 15,765 (4.1%) were partially exposed to rotavirus vaccination, meaning that they received some, but not all, vaccine doses; and 11,003 (2.8%) were unexposed to rotavirus vaccination but had received all other recommended vaccines.

There were 464 cases of type 1 diabetes in the cohort, with an incidence rate of 20 cases per 100,000 person-years in the fully exposed group, 31.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in the partially exposed group, and 22.4 cases per 100,000 person-years in the unexposed group.

The incidence of type 1 diabetes was not significantly different across the rotavirus vaccine–exposure groups. The researchers reported that, compared with children unexposed to rotavirus vaccination, the adjusted hazard ratio for children fully exposed to rotavirus vaccination was 1.03 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-1.72), and for those partially exposed to the vaccination, it was 1.50 (95% CI, 0.81-2.77).

“Since licensure, rotavirus vaccination has been associated with a reduction in morbidity and mortality due to rotavirus infection in the United States and worldwide. ... Although rotavirus vaccination may not prevent type 1 diabetes, these results should provide additional reassurance to the public that rotavirus vaccination can be safely administered to infants,” they wrote.

The limited follow-up duration and relatively small proportion of patients unexposed to rotavirus vaccination are limitations of the study, the authors noted.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Several authors reported having received grants from the CDC. One author received grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and another from pharmaceutical companies not involved in the study.

SOURCE: Glanz JM et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6324.

published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Previous findings from a number of studies have indicated a possible association between rotavirus and type 1 diabetes, according to Jason M. Glanz, PhD, and colleagues. “Epidemiologic data suggest an association between gastrointestinal infection and incidence of type 1 diabetes in children followed from birth to age 10 years. Given these findings, it is biologically plausible that live, attenuated rotavirus vaccine could either increase or decrease the risk for type 1 diabetes in early childhood,” they wrote.

To examine the association between rotavirus vaccination and the incidence of type 1 diabetes in a cohort of U.S. children, Dr. Glanz, a senior investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institute for Health Research in Aurora, and colleagues retrospectively analyzed data from seven health care organizations that participate in the Vaccine Safety Datalink.