User login

Infection control protects hospital staff from COVID-19, study shows

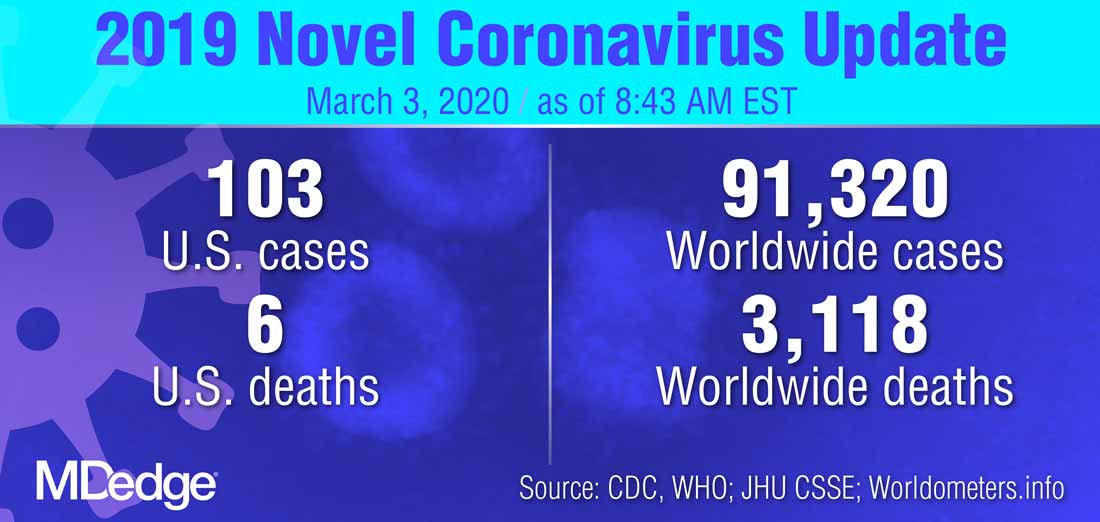

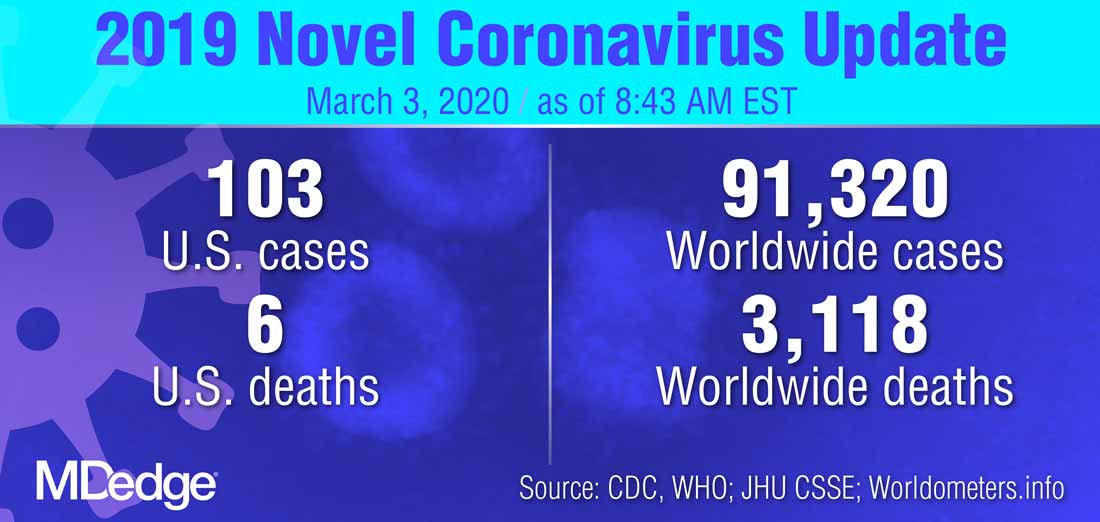

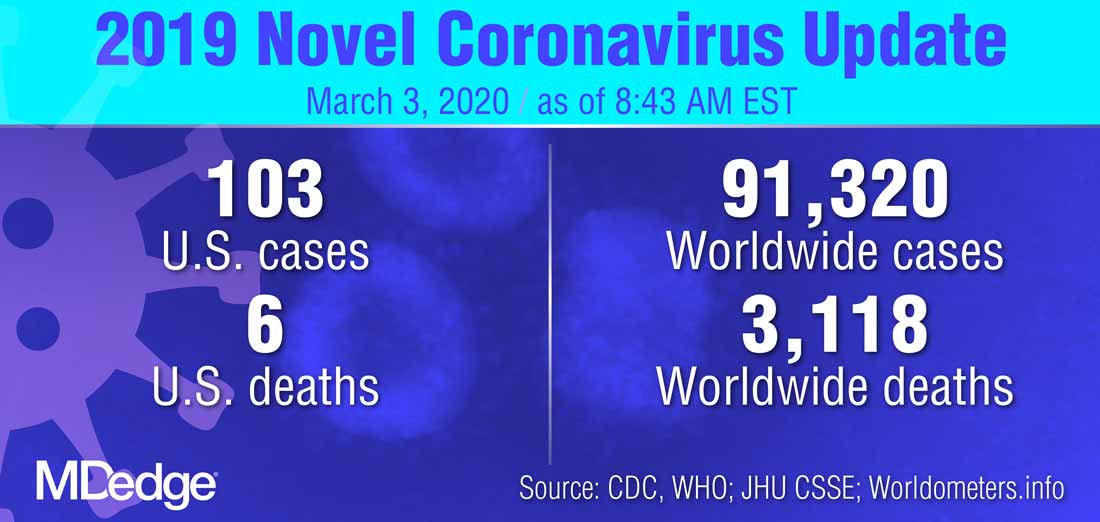

Hospital-related infections have been widely reported during the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, with healthcare professionals bearing a disproportionate risk. However, a proactive response in Hong Kong’s public hospital system appears to have bucked this trend and successfully protected both patients and staff from SARS-CoV-2, according to a study published online today in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

During the first 42 days of the outbreak, the 43 hospitals in the network tested 1275 suspected cases and treated 42 patients with confirmed COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Yet, there were no nosocomial infections or infections among healthcare personnel, report Vincent C.C. Cheng, MD, FRCPath, the hospital’s infection control officer, and colleagues.

Cheng and colleagues note that 11 out of 413 healthcare workers who treat patients with confirmed infections had unprotected exposure and were in quarantine for 14 days, but none became ill.

In comparison, they note, the 2003 SARS outbreak saw almost 60% of nosocomial cases occurring in healthcare workers.

Proactive bundle

The Hong Kong success story may be due to a stepped-up proactive bundle of measures that included enhanced laboratory surveillance, early airborne infection isolation, and rapid-turnaround molecular diagnostics. Other strategies included staff forums and one-on-one discussions about infection control, employee training in protective equipment use, hand-hygiene compliance enforcement, and contact tracing for workers with unprotected exposure.

In addition, surgical masks were provided for all healthcare workers, patients, and visitors to clinical areas, a practice previously associated with reduced in-hospital transmission during influenza outbreaks, the authors note.

Hospitals also mandated use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs), such as endotracheal intubation, open suctioning, and high-flow oxygen use, as AGPs had been linked to nosocomial transmission to healthcare workers during the 2003 SARS outbreak.

The infection control measures, which were part of a preparedness plan developed after the SARS outbreak, were initiated on December 31, when the first reports of a cluster of infections came from Wuhan, China.

As the outbreak evolved, the Hong Kong hospitals quickly widened the epidemiologic criteria for screening, from initially including only those who had been to a wet market in Wuhan within 14 days of symptom onset, to eventually including anyone who had been to Hubei province, been in a medical facility in mainland China, or in contact with a known case.

All suspected cases were sent to an airborne-infection isolation room (AIIR) or a ward with at least a meter of space between patients.

“Appropriate hospital infection control measures could prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” the authors write. “Vigilance in hand hygiene practice, wearing of surgical mask in the hospital, and appropriate use of PPE in patient care, especially [when] performing AGPs, are the key infection control measures to prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 even before the availability of effective antiviral agents and vaccine.”

Asked for his perspective on the report, Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chairman of the department of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, said that apart from the widespread issuing of surgical masks to workers, patients, and visitors, the measures taken in Hong Kong are not different from standard infection-control practices in American hospitals. Glatt, who is also a hospital epidemiologist, said it was unclear how much impact the masks would have.

“Although the infection control was impressive, I don’t see any evidence of a difference in care,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Could zero infection transmission be achieved in the more far-flung and variable settings of hospitals across the United States? “The ability to get zero transmission is only possible if people adhere to the strictest infection-control guidelines,” Glatt said. “That is clearly the goal, and it will take time to see if our existing strict guidelines are sufficient to maintain zero or close to zero contamination and transmission rates in our hospitals.”

Rather than looking to change US practices, he stressed adherence to widely established tenets of care. “It’s critically important to keep paying close attention to the basics, to the simple blocking and tackling, and to identify which patients are at risk, and therefore, when workers need protective equipment,” he said.

“Follow the recommended standards,” continued Glatt, who is also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and did not participate in this study.

In a finding from an ancillary pilot experiment, the Hong Kong researchers found exhaled air from a patient with a moderate coronavirus load showed no evidence of the virus, whether the patient was breathing normally or heavily, speaking, or coughing. And spot tests around the room detected the virus in just one location.

“We may not be able to make a definite conclusion based on the analysis of a single patient,” the authors write. “However, it may help to reassure our staff that the exhaled air may be rapidly diluted inside the AIIR with 12 air changes per hour, or probably the SARS-CoV-2 may not be predominantly transmitted by [the] airborne route.”

However, a recent Singapore study showed widespread environmental contamination by SARS-CoV-2 through respiratory droplets and fecal shedding, underlining the need for strict adherence to environmental and hand hygiene. Post-cleaning samples tested negative, suggesting that standard decontamination practices are effective.

This work was partly supported by the Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Ministry of Education of China. The authors and Glatt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital-related infections have been widely reported during the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, with healthcare professionals bearing a disproportionate risk. However, a proactive response in Hong Kong’s public hospital system appears to have bucked this trend and successfully protected both patients and staff from SARS-CoV-2, according to a study published online today in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

During the first 42 days of the outbreak, the 43 hospitals in the network tested 1275 suspected cases and treated 42 patients with confirmed COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Yet, there were no nosocomial infections or infections among healthcare personnel, report Vincent C.C. Cheng, MD, FRCPath, the hospital’s infection control officer, and colleagues.

Cheng and colleagues note that 11 out of 413 healthcare workers who treat patients with confirmed infections had unprotected exposure and were in quarantine for 14 days, but none became ill.

In comparison, they note, the 2003 SARS outbreak saw almost 60% of nosocomial cases occurring in healthcare workers.

Proactive bundle

The Hong Kong success story may be due to a stepped-up proactive bundle of measures that included enhanced laboratory surveillance, early airborne infection isolation, and rapid-turnaround molecular diagnostics. Other strategies included staff forums and one-on-one discussions about infection control, employee training in protective equipment use, hand-hygiene compliance enforcement, and contact tracing for workers with unprotected exposure.

In addition, surgical masks were provided for all healthcare workers, patients, and visitors to clinical areas, a practice previously associated with reduced in-hospital transmission during influenza outbreaks, the authors note.

Hospitals also mandated use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs), such as endotracheal intubation, open suctioning, and high-flow oxygen use, as AGPs had been linked to nosocomial transmission to healthcare workers during the 2003 SARS outbreak.

The infection control measures, which were part of a preparedness plan developed after the SARS outbreak, were initiated on December 31, when the first reports of a cluster of infections came from Wuhan, China.

As the outbreak evolved, the Hong Kong hospitals quickly widened the epidemiologic criteria for screening, from initially including only those who had been to a wet market in Wuhan within 14 days of symptom onset, to eventually including anyone who had been to Hubei province, been in a medical facility in mainland China, or in contact with a known case.

All suspected cases were sent to an airborne-infection isolation room (AIIR) or a ward with at least a meter of space between patients.

“Appropriate hospital infection control measures could prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” the authors write. “Vigilance in hand hygiene practice, wearing of surgical mask in the hospital, and appropriate use of PPE in patient care, especially [when] performing AGPs, are the key infection control measures to prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 even before the availability of effective antiviral agents and vaccine.”

Asked for his perspective on the report, Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chairman of the department of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, said that apart from the widespread issuing of surgical masks to workers, patients, and visitors, the measures taken in Hong Kong are not different from standard infection-control practices in American hospitals. Glatt, who is also a hospital epidemiologist, said it was unclear how much impact the masks would have.

“Although the infection control was impressive, I don’t see any evidence of a difference in care,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Could zero infection transmission be achieved in the more far-flung and variable settings of hospitals across the United States? “The ability to get zero transmission is only possible if people adhere to the strictest infection-control guidelines,” Glatt said. “That is clearly the goal, and it will take time to see if our existing strict guidelines are sufficient to maintain zero or close to zero contamination and transmission rates in our hospitals.”

Rather than looking to change US practices, he stressed adherence to widely established tenets of care. “It’s critically important to keep paying close attention to the basics, to the simple blocking and tackling, and to identify which patients are at risk, and therefore, when workers need protective equipment,” he said.

“Follow the recommended standards,” continued Glatt, who is also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and did not participate in this study.

In a finding from an ancillary pilot experiment, the Hong Kong researchers found exhaled air from a patient with a moderate coronavirus load showed no evidence of the virus, whether the patient was breathing normally or heavily, speaking, or coughing. And spot tests around the room detected the virus in just one location.

“We may not be able to make a definite conclusion based on the analysis of a single patient,” the authors write. “However, it may help to reassure our staff that the exhaled air may be rapidly diluted inside the AIIR with 12 air changes per hour, or probably the SARS-CoV-2 may not be predominantly transmitted by [the] airborne route.”

However, a recent Singapore study showed widespread environmental contamination by SARS-CoV-2 through respiratory droplets and fecal shedding, underlining the need for strict adherence to environmental and hand hygiene. Post-cleaning samples tested negative, suggesting that standard decontamination practices are effective.

This work was partly supported by the Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Ministry of Education of China. The authors and Glatt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital-related infections have been widely reported during the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, with healthcare professionals bearing a disproportionate risk. However, a proactive response in Hong Kong’s public hospital system appears to have bucked this trend and successfully protected both patients and staff from SARS-CoV-2, according to a study published online today in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

During the first 42 days of the outbreak, the 43 hospitals in the network tested 1275 suspected cases and treated 42 patients with confirmed COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Yet, there were no nosocomial infections or infections among healthcare personnel, report Vincent C.C. Cheng, MD, FRCPath, the hospital’s infection control officer, and colleagues.

Cheng and colleagues note that 11 out of 413 healthcare workers who treat patients with confirmed infections had unprotected exposure and were in quarantine for 14 days, but none became ill.

In comparison, they note, the 2003 SARS outbreak saw almost 60% of nosocomial cases occurring in healthcare workers.

Proactive bundle

The Hong Kong success story may be due to a stepped-up proactive bundle of measures that included enhanced laboratory surveillance, early airborne infection isolation, and rapid-turnaround molecular diagnostics. Other strategies included staff forums and one-on-one discussions about infection control, employee training in protective equipment use, hand-hygiene compliance enforcement, and contact tracing for workers with unprotected exposure.

In addition, surgical masks were provided for all healthcare workers, patients, and visitors to clinical areas, a practice previously associated with reduced in-hospital transmission during influenza outbreaks, the authors note.

Hospitals also mandated use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs), such as endotracheal intubation, open suctioning, and high-flow oxygen use, as AGPs had been linked to nosocomial transmission to healthcare workers during the 2003 SARS outbreak.

The infection control measures, which were part of a preparedness plan developed after the SARS outbreak, were initiated on December 31, when the first reports of a cluster of infections came from Wuhan, China.

As the outbreak evolved, the Hong Kong hospitals quickly widened the epidemiologic criteria for screening, from initially including only those who had been to a wet market in Wuhan within 14 days of symptom onset, to eventually including anyone who had been to Hubei province, been in a medical facility in mainland China, or in contact with a known case.

All suspected cases were sent to an airborne-infection isolation room (AIIR) or a ward with at least a meter of space between patients.

“Appropriate hospital infection control measures could prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” the authors write. “Vigilance in hand hygiene practice, wearing of surgical mask in the hospital, and appropriate use of PPE in patient care, especially [when] performing AGPs, are the key infection control measures to prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 even before the availability of effective antiviral agents and vaccine.”

Asked for his perspective on the report, Aaron E. Glatt, MD, chairman of the department of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, said that apart from the widespread issuing of surgical masks to workers, patients, and visitors, the measures taken in Hong Kong are not different from standard infection-control practices in American hospitals. Glatt, who is also a hospital epidemiologist, said it was unclear how much impact the masks would have.

“Although the infection control was impressive, I don’t see any evidence of a difference in care,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Could zero infection transmission be achieved in the more far-flung and variable settings of hospitals across the United States? “The ability to get zero transmission is only possible if people adhere to the strictest infection-control guidelines,” Glatt said. “That is clearly the goal, and it will take time to see if our existing strict guidelines are sufficient to maintain zero or close to zero contamination and transmission rates in our hospitals.”

Rather than looking to change US practices, he stressed adherence to widely established tenets of care. “It’s critically important to keep paying close attention to the basics, to the simple blocking and tackling, and to identify which patients are at risk, and therefore, when workers need protective equipment,” he said.

“Follow the recommended standards,” continued Glatt, who is also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and did not participate in this study.

In a finding from an ancillary pilot experiment, the Hong Kong researchers found exhaled air from a patient with a moderate coronavirus load showed no evidence of the virus, whether the patient was breathing normally or heavily, speaking, or coughing. And spot tests around the room detected the virus in just one location.

“We may not be able to make a definite conclusion based on the analysis of a single patient,” the authors write. “However, it may help to reassure our staff that the exhaled air may be rapidly diluted inside the AIIR with 12 air changes per hour, or probably the SARS-CoV-2 may not be predominantly transmitted by [the] airborne route.”

However, a recent Singapore study showed widespread environmental contamination by SARS-CoV-2 through respiratory droplets and fecal shedding, underlining the need for strict adherence to environmental and hand hygiene. Post-cleaning samples tested negative, suggesting that standard decontamination practices are effective.

This work was partly supported by the Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; and the Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Ministry of Education of China. The authors and Glatt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

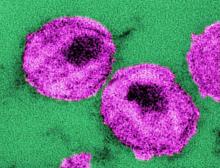

Monthly injection therapy for HIV found noninferior to daily oral dosing

Two international phase 3 randomized trials of according to reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine after Oral Induction for HIV-1 Infection (FLAIR) study and the Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for Maintenance of HIV-1 Suppression (ATLAS) study looked at a separate facet of the use of a monthly therapeutic injection as a replacement for daily oral HIV therapy.

The FLAIR trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02938520) was a phase 3, randomized, open-label study in which adults with HIV-1 infection who had not previously received antiretroviral therapy were given 20 weeks of daily oral induction therapy with dolutegravir–abacavir–lamivudine. Those patients with an HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter after 16 weeks were then randomly assigned (1:1) to continue their current oral therapy or switch to oral cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for 1 month followed by monthly intramuscular injections of long-acting cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor.

At week 48, an HIV-1 RNA level of 50 copies per milliliter or higher was found in 6 of 283 patients (2.1%) who received the long-acting therapy and in 7 of 283 (2.5%) who received oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint. An HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 was found in 93.6% of patients who received long-acting therapy and in 93.3% who received oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority, according to the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Injection site reactions were reported in 86% of the long-acting therapy patients, 4 of whom withdrew from the trial for injection-related reasons. Grade 3 or higher adverse events and events that met liver-related stopping criteria occurred in 11% and 2%, respectively, of those who received long-acting therapy and in 4% and 1% of those who received oral therapy.

An assessment of treatment satisfaction at 48 weeks showed that 91% of the patients who switched to long-acting therapy preferred it to their daily oral therapy.

The ATLAS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02951052) was a phase 3, open-label, multicenter, noninferiority trial involving patients who had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter for at least 6 months while taking standard oral antiretroviral therapy. These patients were randomized (308 in each group) to the long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine injection therapy or daily oral therapy.

At 48 weeks, HIV-1 RNA levels of 50 copies per milliliter or higher were found in five participants (1.6%) receiving long-acting therapy and in three (1.0%) receiving oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint, according to a study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 occurred in 92.5% of patients on long-acting therapy and in 95.5% of those receiving oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority for this endpoint. Three patients in the long-acting therapy group had virologic failure, compared with four participants who received oral therapy.

Adverse events were more common in the long-acting–therapy group and included injection-site pain, which occurred in 231 recipients (75%) of long-acting therapy. This was mild or moderate in most cases, according to the authors. However, 1% of the participants in this group withdrew because of it. Overall, serious adverse events were reported in no more than 5% of participants in each group.

Together, the ATLAS and the FLAIR trials show that long-acting intramuscular injection therapy is noninferior to oral therapy as both an early regimen for HIV treatment, as well as for later, maintenance dosing. The use of long-acting therapy may improve patient adherence to treatment, according to both sets of study authors.

The ATLAS and FLAIR trials were funded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen. The authors of both studies reported ties to pharmaceutical associations, and some authors are employees of the two funding sources.

SOURCE: Orkin C et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909512 and Swindells S et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904398.

Two international phase 3 randomized trials of according to reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine after Oral Induction for HIV-1 Infection (FLAIR) study and the Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for Maintenance of HIV-1 Suppression (ATLAS) study looked at a separate facet of the use of a monthly therapeutic injection as a replacement for daily oral HIV therapy.

The FLAIR trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02938520) was a phase 3, randomized, open-label study in which adults with HIV-1 infection who had not previously received antiretroviral therapy were given 20 weeks of daily oral induction therapy with dolutegravir–abacavir–lamivudine. Those patients with an HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter after 16 weeks were then randomly assigned (1:1) to continue their current oral therapy or switch to oral cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for 1 month followed by monthly intramuscular injections of long-acting cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor.

At week 48, an HIV-1 RNA level of 50 copies per milliliter or higher was found in 6 of 283 patients (2.1%) who received the long-acting therapy and in 7 of 283 (2.5%) who received oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint. An HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 was found in 93.6% of patients who received long-acting therapy and in 93.3% who received oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority, according to the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Injection site reactions were reported in 86% of the long-acting therapy patients, 4 of whom withdrew from the trial for injection-related reasons. Grade 3 or higher adverse events and events that met liver-related stopping criteria occurred in 11% and 2%, respectively, of those who received long-acting therapy and in 4% and 1% of those who received oral therapy.

An assessment of treatment satisfaction at 48 weeks showed that 91% of the patients who switched to long-acting therapy preferred it to their daily oral therapy.

The ATLAS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02951052) was a phase 3, open-label, multicenter, noninferiority trial involving patients who had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter for at least 6 months while taking standard oral antiretroviral therapy. These patients were randomized (308 in each group) to the long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine injection therapy or daily oral therapy.

At 48 weeks, HIV-1 RNA levels of 50 copies per milliliter or higher were found in five participants (1.6%) receiving long-acting therapy and in three (1.0%) receiving oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint, according to a study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 occurred in 92.5% of patients on long-acting therapy and in 95.5% of those receiving oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority for this endpoint. Three patients in the long-acting therapy group had virologic failure, compared with four participants who received oral therapy.

Adverse events were more common in the long-acting–therapy group and included injection-site pain, which occurred in 231 recipients (75%) of long-acting therapy. This was mild or moderate in most cases, according to the authors. However, 1% of the participants in this group withdrew because of it. Overall, serious adverse events were reported in no more than 5% of participants in each group.

Together, the ATLAS and the FLAIR trials show that long-acting intramuscular injection therapy is noninferior to oral therapy as both an early regimen for HIV treatment, as well as for later, maintenance dosing. The use of long-acting therapy may improve patient adherence to treatment, according to both sets of study authors.

The ATLAS and FLAIR trials were funded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen. The authors of both studies reported ties to pharmaceutical associations, and some authors are employees of the two funding sources.

SOURCE: Orkin C et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909512 and Swindells S et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904398.

Two international phase 3 randomized trials of according to reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine after Oral Induction for HIV-1 Infection (FLAIR) study and the Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for Maintenance of HIV-1 Suppression (ATLAS) study looked at a separate facet of the use of a monthly therapeutic injection as a replacement for daily oral HIV therapy.

The FLAIR trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02938520) was a phase 3, randomized, open-label study in which adults with HIV-1 infection who had not previously received antiretroviral therapy were given 20 weeks of daily oral induction therapy with dolutegravir–abacavir–lamivudine. Those patients with an HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter after 16 weeks were then randomly assigned (1:1) to continue their current oral therapy or switch to oral cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for 1 month followed by monthly intramuscular injections of long-acting cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor.

At week 48, an HIV-1 RNA level of 50 copies per milliliter or higher was found in 6 of 283 patients (2.1%) who received the long-acting therapy and in 7 of 283 (2.5%) who received oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint. An HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 was found in 93.6% of patients who received long-acting therapy and in 93.3% who received oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority, according to the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Injection site reactions were reported in 86% of the long-acting therapy patients, 4 of whom withdrew from the trial for injection-related reasons. Grade 3 or higher adverse events and events that met liver-related stopping criteria occurred in 11% and 2%, respectively, of those who received long-acting therapy and in 4% and 1% of those who received oral therapy.

An assessment of treatment satisfaction at 48 weeks showed that 91% of the patients who switched to long-acting therapy preferred it to their daily oral therapy.

The ATLAS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02951052) was a phase 3, open-label, multicenter, noninferiority trial involving patients who had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter for at least 6 months while taking standard oral antiretroviral therapy. These patients were randomized (308 in each group) to the long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine injection therapy or daily oral therapy.

At 48 weeks, HIV-1 RNA levels of 50 copies per milliliter or higher were found in five participants (1.6%) receiving long-acting therapy and in three (1.0%) receiving oral therapy, which met the criterion for noninferiority for the primary endpoint, according to a study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

HIV-1 RNA levels of less than 50 copies per milliliter at week 48 occurred in 92.5% of patients on long-acting therapy and in 95.5% of those receiving oral therapy, which also met the criterion for noninferiority for this endpoint. Three patients in the long-acting therapy group had virologic failure, compared with four participants who received oral therapy.

Adverse events were more common in the long-acting–therapy group and included injection-site pain, which occurred in 231 recipients (75%) of long-acting therapy. This was mild or moderate in most cases, according to the authors. However, 1% of the participants in this group withdrew because of it. Overall, serious adverse events were reported in no more than 5% of participants in each group.

Together, the ATLAS and the FLAIR trials show that long-acting intramuscular injection therapy is noninferior to oral therapy as both an early regimen for HIV treatment, as well as for later, maintenance dosing. The use of long-acting therapy may improve patient adherence to treatment, according to both sets of study authors.

The ATLAS and FLAIR trials were funded by ViiV Healthcare and Janssen. The authors of both studies reported ties to pharmaceutical associations, and some authors are employees of the two funding sources.

SOURCE: Orkin C et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909512 and Swindells S et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904398.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

What’s Eating You? Human Body Lice (Pediculus humanus corporis)

Epidemiology and Transmission

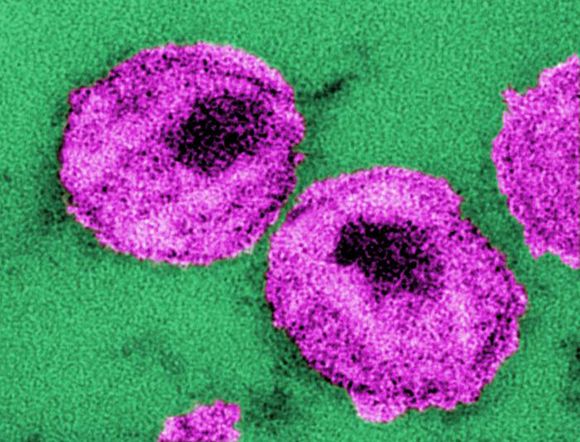

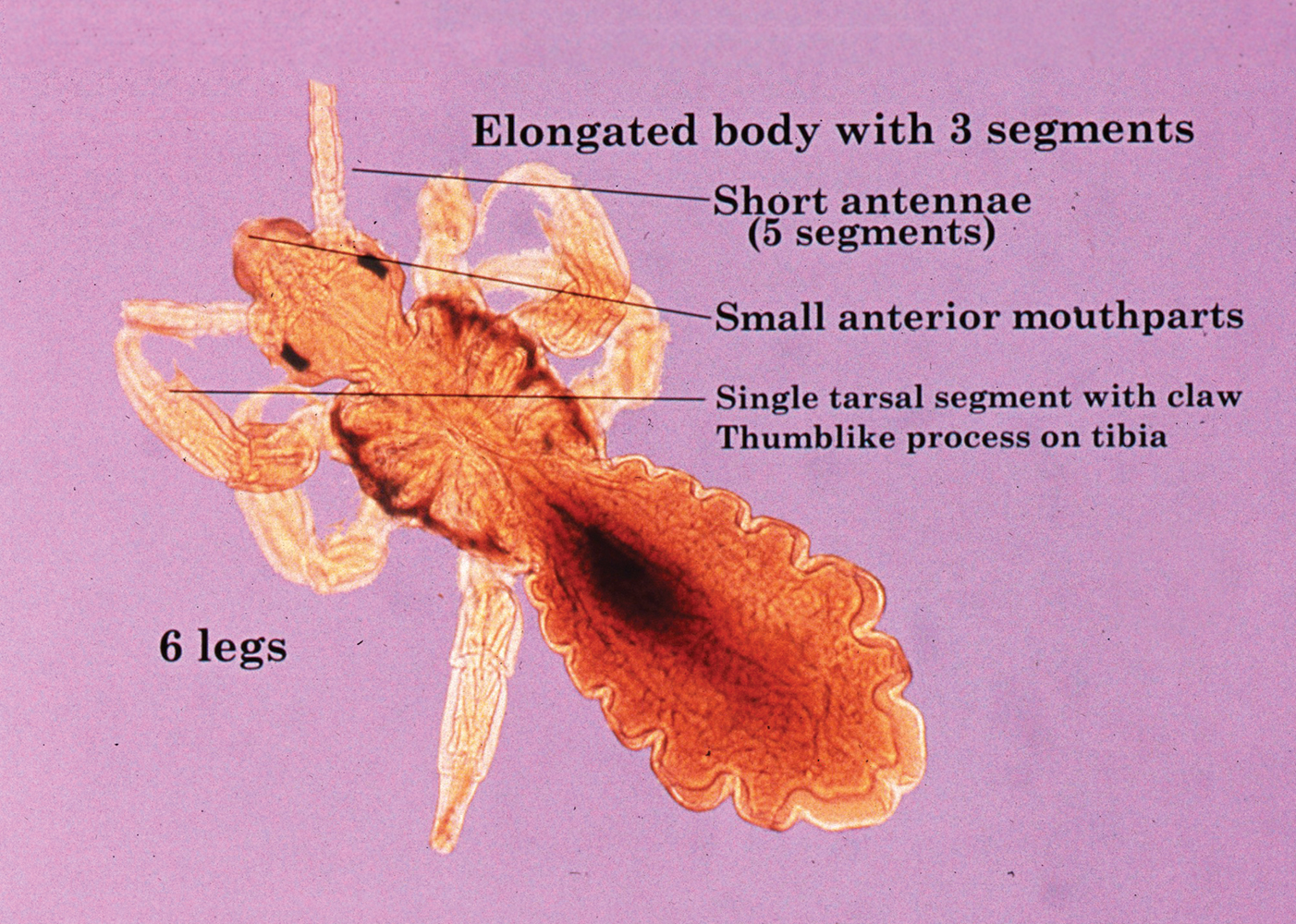

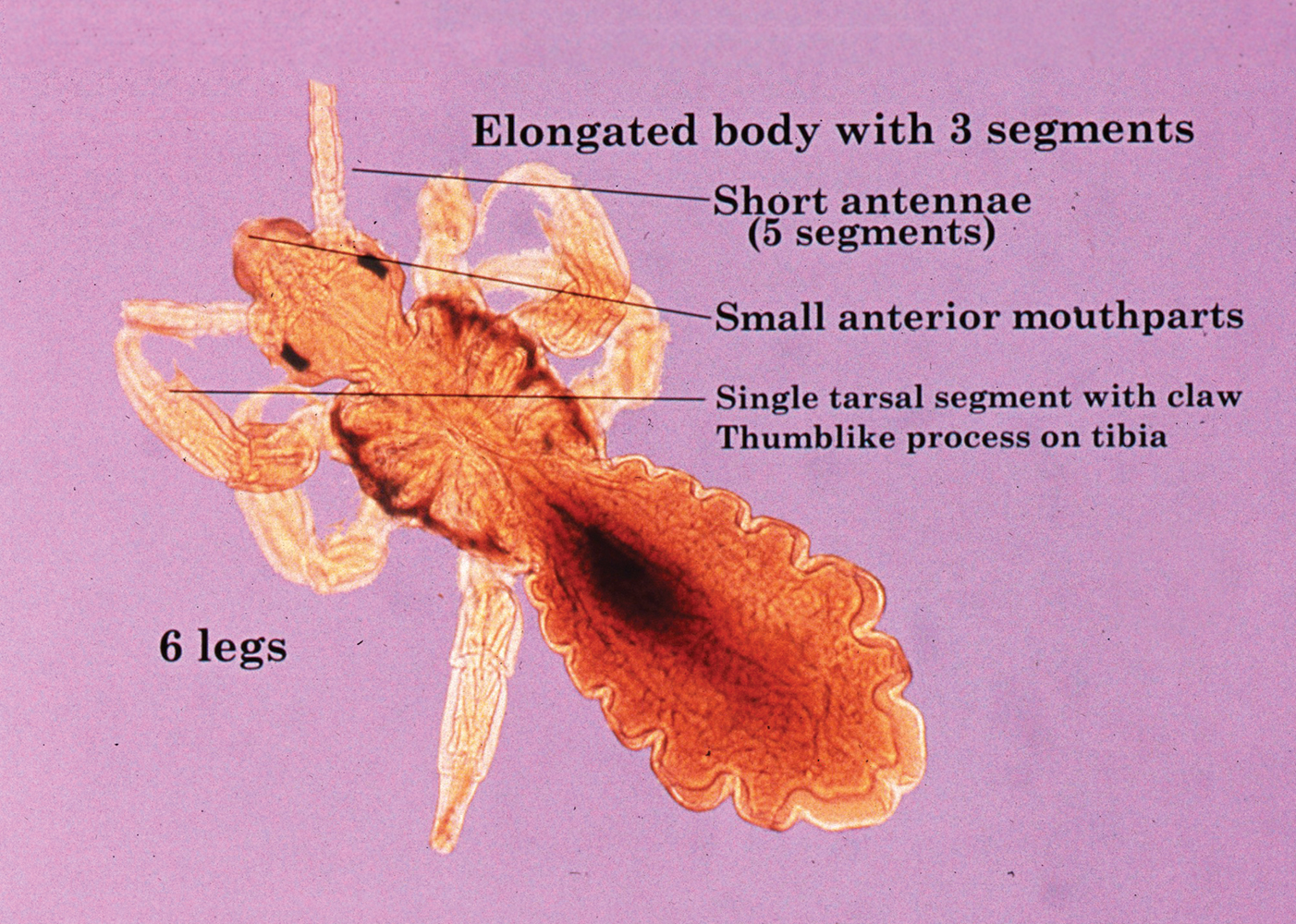

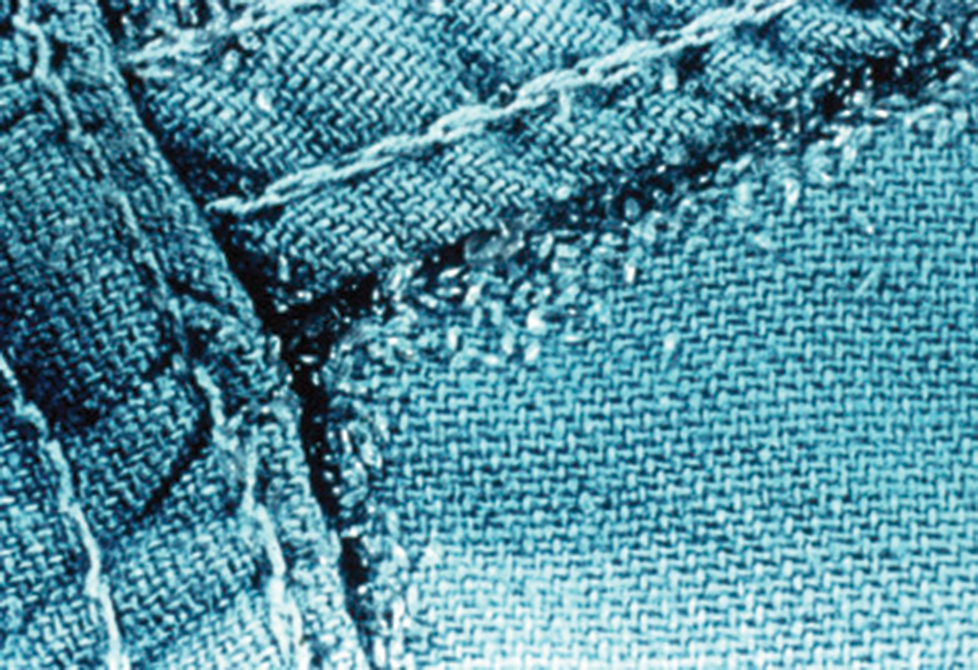

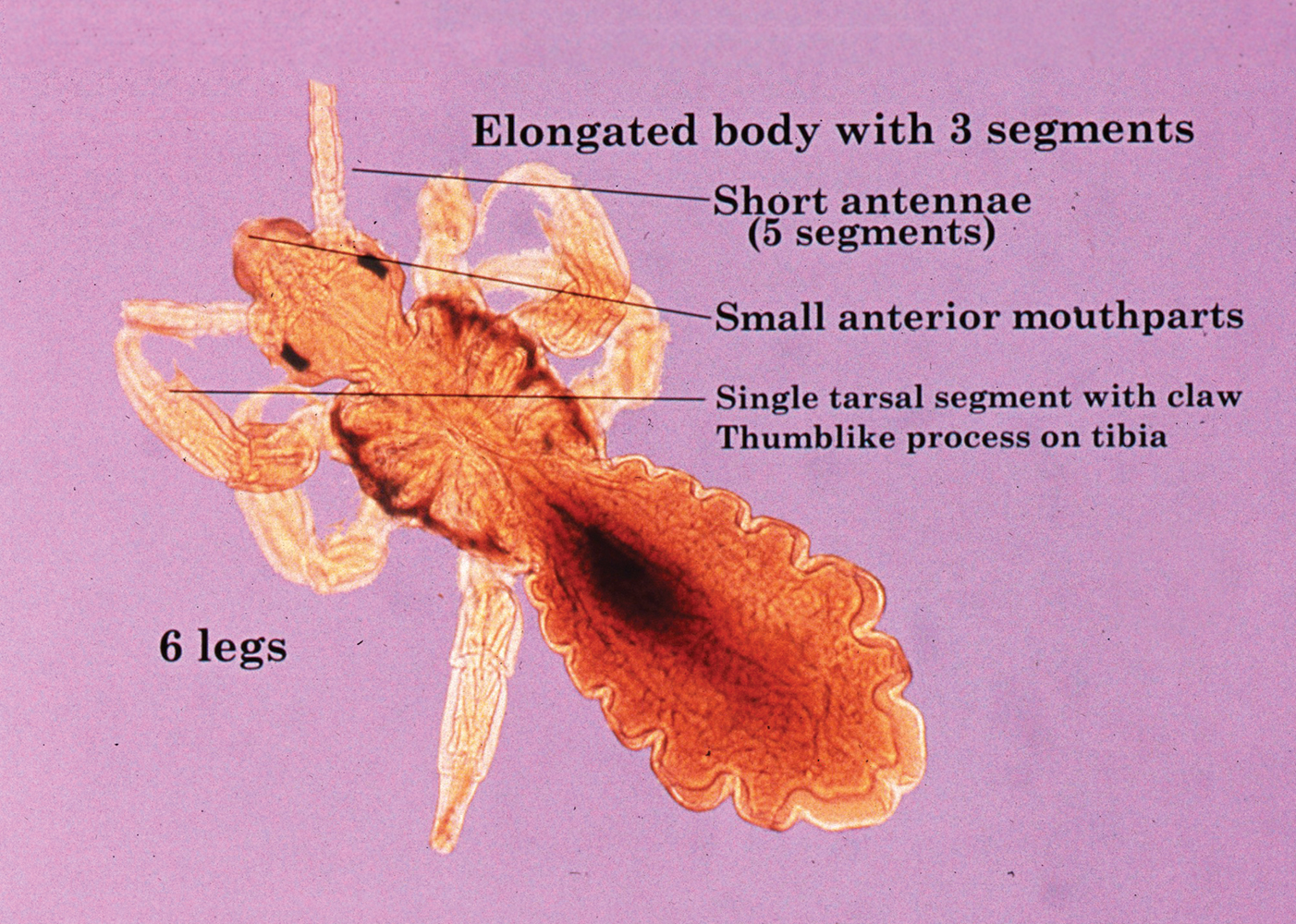

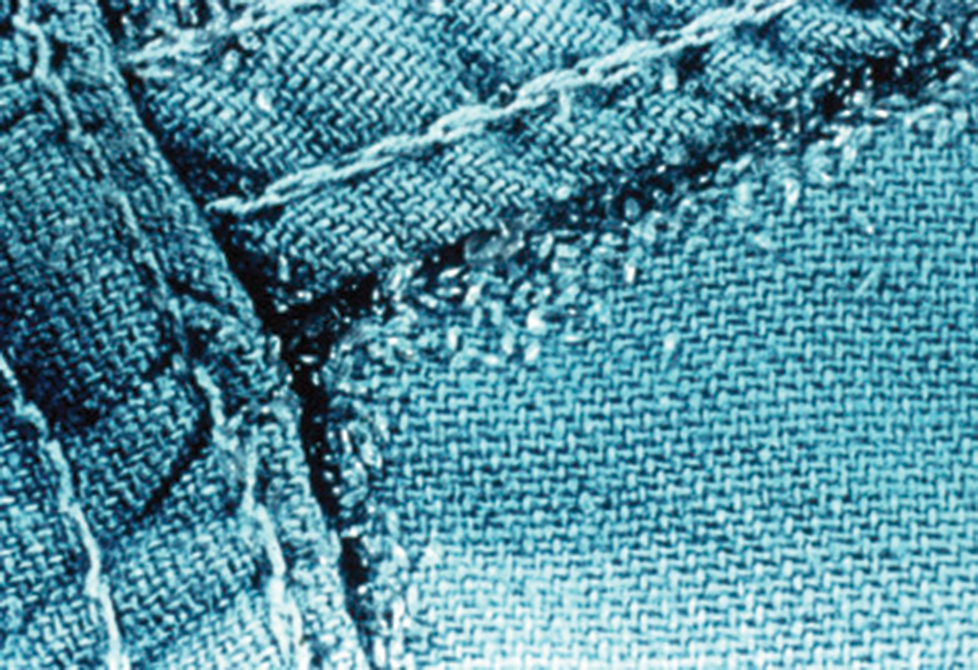

Pediculus humanus corporis, commonly known as the human body louse, is one in a family of 3 ectoparasites of the same suborder that also encompasses pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) and head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). Adults are approximately 2 mm in size, with the same life cycle as head lice (Figure 1). They require blood meals roughly 5 times per day and cannot survive longer than 2 days without feeding.1 Although similar in structure to head lice, body lice differ behaviorally in that they do not reside on their human host’s body; instead, they infest the host’s clothing, localizing to seams (Figure 2), and migrate to the host for blood meals. In fact, based on this behavior, genetic analysis of early human body lice has been used to postulate when clothing was first used by humans as well as to determine early human migration patterns.2,3

Although clinicians in developed countries may be less familiar with body lice compared to their counterparts, body lice nevertheless remain a global health concern in impoverished, densely populated areas, as well as in homeless populations due to poor hygiene. Transmission frequently occurs via physical contact with an affected individual and his/her personal items (eg, linens) via fomites.4,5 Body louse infestation is more prevalent in homeless individuals who sleep outside vs in shelters; a history of pubic lice and lack of regular bathing have been reported as additional risk factors.6 Outbreaks have been noted in the wake of natural disasters, in the setting of political upheavals, and in refugee camps, as well as in individuals seeking political asylum.7 Unlike head and pubic lice, body lice can serve as vectors for infectious diseases including Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), Bartonella quintana (trench fever), and Yersinia pestis (plague).5,8,9 Several Acinetobacter species were isolated from nearly one-third of collected body louse specimens in a French study.10 Additionally, serology for B quintana was found to be positive in up to 30% of cases in one United States urban homeless population.4

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often present with generalized pruritus, usually considerably more severe than with P humanus capitis, with lesions concentrated on the trunk.11 In addition to often impetiginized, self-inflicted excoriations, feeding sites may present as erythematous macules (Figure 3), papules, or papular urticaria with a central hemorrhagic punctum. Extensive infestation also can manifest as the colloquial vagabond disease, characterized by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and thickening of the involved skin. Remarkably, patients also may present with considerable iron-deficiency anemia secondary to high parasite load and large volume blood feeding. Multiple case reports have demonstrated associated morbidity.12-14 The differential diagnosis for pediculosis may include scabies, lichen simplex chronicus, and eczematous dermatitis, though the clinician should prudently consider whether both scabies and pediculosis may be present, as coexistence is possible.4,15

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be reached by visualizing adult lice, nymphs, or viable nits on the body or more commonly within inner clothing seams; nits also fluoresce under Wood light.15 Although dermoscopy has proven useful for increased sensitivity and differentiation between viable and hatched nits, the insects also can be viewed with the unaided eye.16

Treatment: New Concerns and Strategies

The mainstay of treatment for body lice has long consisted of thorough washing and drying of all clothing and linens in a hot dryer. Treatment can be augmented with the addition of pharmacotherapy, plus antibiotics as warranted for louse-borne disease. Pharmacologic intervention often is used in cases of mass infestation and is similar to head lice.

Options for head lice include topical permethrin, malathion, lindane, spinosad, benzyl alcohol, and ivermectin. Pyrethroids, derived from the chrysanthemum, generally are considered safe for human use with a side-effect profile limited to irritation and allergy17; however, neurotoxicity and leukemia are clinical concerns, with an association more recently shown between large-volume use of pyrethroids and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.18,19 Use of lindane is not recommended due to a greater potential for central nervous system neurotoxicity, manifested by seizures, with repeated large surface application. Malathion is problematic due to the risk for mucosal irritation, flammability of some formulations, and theoretical organophosphate poisoning, as its mechanism of action involves inhibition of acetylcholinesterase.15 However, in the context of head lice treatment, a randomized controlled trial reported no incidence of acetylcholinesterase inhibition.20 Spinosad, manufactured from the soil bacterium Saccharopolyspora spinosa, functions similarly by interfering with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and also carries a risk for skin irritation.21 Among all the treatment options, we prefer benzyl alcohol, particularly in the context of resistance, as it is effective via a physical mechanism of action and lacks notable neurotoxic effects to the host. Use of benzyl alcohol is approved for patients as young as 6 months; it functions by asphyxiating the lice via paralysis of the respiratory spiracle with occlusion by inert ingredients. Itching, episodic numbness, and scalp or mucosal irritation are possible complications of treatment.22

Treatment resistance of body lice has increased in recent years, warranting exploration of additional management strategies. Moreover, developing resistance to lindane and malathion has been reported.23 Resistance to pyrethroids has been attributed to mutations in a voltage-gated sodium channel, one of which was universally present in the sampling of a single population.24 A randomized controlled trial showed that off-label oral ivermectin 400 μg/kg was superior to malathion lotion 0.5% in difficult-to-treat cases of head lice25; utility of oral ivermectin also has been reported in body lice.26 In vitro studies also have shown promise for pursuing synergistic treatment of body lice with both ivermectin and antibiotics.27

A novel primary prophylaxis approach for at-risk homeless individuals recently utilized permethrin-impregnated underwear. Although the intervention provided short-term infestation improvement, longer-term use did not show improvement from placebo and also increased prevalence of permethrin-resistant haplotypes.2

- Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571.

- Kittler R, Kayser M, Stoneking M. Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1414-1417.

- Drali R, Mumcuoglu KY, Yesilyurt G, et al. Studies of ancient lice reveal unsuspected past migrations of vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:623-625.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J. Epidermal parasitic skin diseases: a neglected category of poverty-associated plagues. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:152-159.

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Detrez MA, et al. Prevalence of scabies and Pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112.

- Hytonen J, Khawaja T, Gronroos JO, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever in Finland in two asylum seekers from Somalia. APMIS. 2017;125:59-62.

- Nordmann T, Feldt T, Bosselmann M, et al. Outbreak of louse-borne relapsing fever among urban dwellers in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia, from July to November 2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1599-1602.

- Louni M, Mana N, Bitam I, et al. Body lice of homeless people reveal the presence of several emerging bacterial pathogens in northern Algeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006397.

- Candy K, Amanzougaghene N, Izri A, et al. Molecular survey of head and body lice, Pediculus humanus, in France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018;18:243-251.

Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2018. - Nara A, Nagai H, Yamaguchi R, et al. An unusual autopsy case of lethal hypothermia exacerbated by body lice-induced severe anemia. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:765-769.

- Althomali SA, Alzubaidi LM, Alkhaldi DM. Severe iron deficiency anaemia associated with heavy lice infestation in a young woman [published online November 5, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-212207.

- Hau V, Muhi-Iddin N. A ghost covered in lice: a case of severe blood loss with long-standing heavy pediculosis capitis infestation [published online December 19, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-206623.

- Diaz JH. Lice (Pediculosis). In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2020:3482-3486.

- Martins LG, Bernardes Filho F, Quaresma MV, et al. Dermoscopy applied to pediculosis corporis diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:513-514.

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:E1355-E1365.

- Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM. Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides: critical review and future research needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:123-136.

- Ding G, Shi R, Gao Y, et al. Pyrethroid pesticide exposure and risk of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia in Shanghai. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:13480-13487.

- Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, et al. A randomized, investigator-blinded, time-ranging study of the comparative efficacy of 0.5% malathion gel versus Ovide Lotion (0.5% malathion) or Nix Crème Rinse (1% permethrin) used as labeled, for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:405-411.

- McCormack PL. Spinosad: in pediculosis capitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:349-353.

- Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:19-24.

- Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:965-974

- Drali R, Benkouiten S, Badiaga S, et al. Detection of a knockdown resistance mutation associated with permethrin resistance in the body louse Pediculus humanus corporis by use of melting curve analysis genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2229-2233.

- Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:896-905.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476.

- Sangaré AK, Doumbo OK, Raoult D. Management and treatment of human lice [published online July 27, 2016]. Biomed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/8962685.

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279.

Epidemiology and Transmission

Pediculus humanus corporis, commonly known as the human body louse, is one in a family of 3 ectoparasites of the same suborder that also encompasses pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) and head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). Adults are approximately 2 mm in size, with the same life cycle as head lice (Figure 1). They require blood meals roughly 5 times per day and cannot survive longer than 2 days without feeding.1 Although similar in structure to head lice, body lice differ behaviorally in that they do not reside on their human host’s body; instead, they infest the host’s clothing, localizing to seams (Figure 2), and migrate to the host for blood meals. In fact, based on this behavior, genetic analysis of early human body lice has been used to postulate when clothing was first used by humans as well as to determine early human migration patterns.2,3

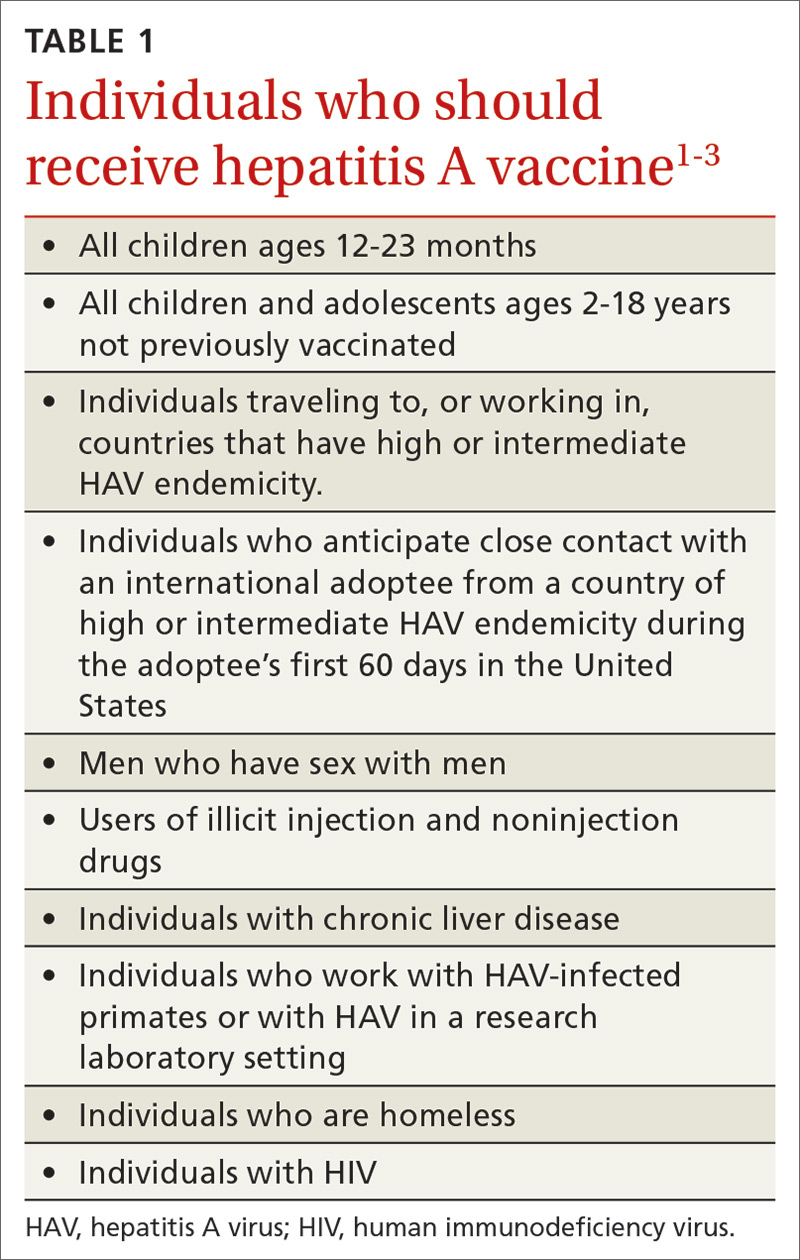

Although clinicians in developed countries may be less familiar with body lice compared to their counterparts, body lice nevertheless remain a global health concern in impoverished, densely populated areas, as well as in homeless populations due to poor hygiene. Transmission frequently occurs via physical contact with an affected individual and his/her personal items (eg, linens) via fomites.4,5 Body louse infestation is more prevalent in homeless individuals who sleep outside vs in shelters; a history of pubic lice and lack of regular bathing have been reported as additional risk factors.6 Outbreaks have been noted in the wake of natural disasters, in the setting of political upheavals, and in refugee camps, as well as in individuals seeking political asylum.7 Unlike head and pubic lice, body lice can serve as vectors for infectious diseases including Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), Bartonella quintana (trench fever), and Yersinia pestis (plague).5,8,9 Several Acinetobacter species were isolated from nearly one-third of collected body louse specimens in a French study.10 Additionally, serology for B quintana was found to be positive in up to 30% of cases in one United States urban homeless population.4

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often present with generalized pruritus, usually considerably more severe than with P humanus capitis, with lesions concentrated on the trunk.11 In addition to often impetiginized, self-inflicted excoriations, feeding sites may present as erythematous macules (Figure 3), papules, or papular urticaria with a central hemorrhagic punctum. Extensive infestation also can manifest as the colloquial vagabond disease, characterized by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and thickening of the involved skin. Remarkably, patients also may present with considerable iron-deficiency anemia secondary to high parasite load and large volume blood feeding. Multiple case reports have demonstrated associated morbidity.12-14 The differential diagnosis for pediculosis may include scabies, lichen simplex chronicus, and eczematous dermatitis, though the clinician should prudently consider whether both scabies and pediculosis may be present, as coexistence is possible.4,15

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be reached by visualizing adult lice, nymphs, or viable nits on the body or more commonly within inner clothing seams; nits also fluoresce under Wood light.15 Although dermoscopy has proven useful for increased sensitivity and differentiation between viable and hatched nits, the insects also can be viewed with the unaided eye.16

Treatment: New Concerns and Strategies

The mainstay of treatment for body lice has long consisted of thorough washing and drying of all clothing and linens in a hot dryer. Treatment can be augmented with the addition of pharmacotherapy, plus antibiotics as warranted for louse-borne disease. Pharmacologic intervention often is used in cases of mass infestation and is similar to head lice.

Options for head lice include topical permethrin, malathion, lindane, spinosad, benzyl alcohol, and ivermectin. Pyrethroids, derived from the chrysanthemum, generally are considered safe for human use with a side-effect profile limited to irritation and allergy17; however, neurotoxicity and leukemia are clinical concerns, with an association more recently shown between large-volume use of pyrethroids and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.18,19 Use of lindane is not recommended due to a greater potential for central nervous system neurotoxicity, manifested by seizures, with repeated large surface application. Malathion is problematic due to the risk for mucosal irritation, flammability of some formulations, and theoretical organophosphate poisoning, as its mechanism of action involves inhibition of acetylcholinesterase.15 However, in the context of head lice treatment, a randomized controlled trial reported no incidence of acetylcholinesterase inhibition.20 Spinosad, manufactured from the soil bacterium Saccharopolyspora spinosa, functions similarly by interfering with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and also carries a risk for skin irritation.21 Among all the treatment options, we prefer benzyl alcohol, particularly in the context of resistance, as it is effective via a physical mechanism of action and lacks notable neurotoxic effects to the host. Use of benzyl alcohol is approved for patients as young as 6 months; it functions by asphyxiating the lice via paralysis of the respiratory spiracle with occlusion by inert ingredients. Itching, episodic numbness, and scalp or mucosal irritation are possible complications of treatment.22

Treatment resistance of body lice has increased in recent years, warranting exploration of additional management strategies. Moreover, developing resistance to lindane and malathion has been reported.23 Resistance to pyrethroids has been attributed to mutations in a voltage-gated sodium channel, one of which was universally present in the sampling of a single population.24 A randomized controlled trial showed that off-label oral ivermectin 400 μg/kg was superior to malathion lotion 0.5% in difficult-to-treat cases of head lice25; utility of oral ivermectin also has been reported in body lice.26 In vitro studies also have shown promise for pursuing synergistic treatment of body lice with both ivermectin and antibiotics.27

A novel primary prophylaxis approach for at-risk homeless individuals recently utilized permethrin-impregnated underwear. Although the intervention provided short-term infestation improvement, longer-term use did not show improvement from placebo and also increased prevalence of permethrin-resistant haplotypes.2

Epidemiology and Transmission

Pediculus humanus corporis, commonly known as the human body louse, is one in a family of 3 ectoparasites of the same suborder that also encompasses pubic lice (Phthirus pubis) and head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). Adults are approximately 2 mm in size, with the same life cycle as head lice (Figure 1). They require blood meals roughly 5 times per day and cannot survive longer than 2 days without feeding.1 Although similar in structure to head lice, body lice differ behaviorally in that they do not reside on their human host’s body; instead, they infest the host’s clothing, localizing to seams (Figure 2), and migrate to the host for blood meals. In fact, based on this behavior, genetic analysis of early human body lice has been used to postulate when clothing was first used by humans as well as to determine early human migration patterns.2,3

Although clinicians in developed countries may be less familiar with body lice compared to their counterparts, body lice nevertheless remain a global health concern in impoverished, densely populated areas, as well as in homeless populations due to poor hygiene. Transmission frequently occurs via physical contact with an affected individual and his/her personal items (eg, linens) via fomites.4,5 Body louse infestation is more prevalent in homeless individuals who sleep outside vs in shelters; a history of pubic lice and lack of regular bathing have been reported as additional risk factors.6 Outbreaks have been noted in the wake of natural disasters, in the setting of political upheavals, and in refugee camps, as well as in individuals seeking political asylum.7 Unlike head and pubic lice, body lice can serve as vectors for infectious diseases including Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), Bartonella quintana (trench fever), and Yersinia pestis (plague).5,8,9 Several Acinetobacter species were isolated from nearly one-third of collected body louse specimens in a French study.10 Additionally, serology for B quintana was found to be positive in up to 30% of cases in one United States urban homeless population.4

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often present with generalized pruritus, usually considerably more severe than with P humanus capitis, with lesions concentrated on the trunk.11 In addition to often impetiginized, self-inflicted excoriations, feeding sites may present as erythematous macules (Figure 3), papules, or papular urticaria with a central hemorrhagic punctum. Extensive infestation also can manifest as the colloquial vagabond disease, characterized by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and thickening of the involved skin. Remarkably, patients also may present with considerable iron-deficiency anemia secondary to high parasite load and large volume blood feeding. Multiple case reports have demonstrated associated morbidity.12-14 The differential diagnosis for pediculosis may include scabies, lichen simplex chronicus, and eczematous dermatitis, though the clinician should prudently consider whether both scabies and pediculosis may be present, as coexistence is possible.4,15

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be reached by visualizing adult lice, nymphs, or viable nits on the body or more commonly within inner clothing seams; nits also fluoresce under Wood light.15 Although dermoscopy has proven useful for increased sensitivity and differentiation between viable and hatched nits, the insects also can be viewed with the unaided eye.16

Treatment: New Concerns and Strategies

The mainstay of treatment for body lice has long consisted of thorough washing and drying of all clothing and linens in a hot dryer. Treatment can be augmented with the addition of pharmacotherapy, plus antibiotics as warranted for louse-borne disease. Pharmacologic intervention often is used in cases of mass infestation and is similar to head lice.

Options for head lice include topical permethrin, malathion, lindane, spinosad, benzyl alcohol, and ivermectin. Pyrethroids, derived from the chrysanthemum, generally are considered safe for human use with a side-effect profile limited to irritation and allergy17; however, neurotoxicity and leukemia are clinical concerns, with an association more recently shown between large-volume use of pyrethroids and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.18,19 Use of lindane is not recommended due to a greater potential for central nervous system neurotoxicity, manifested by seizures, with repeated large surface application. Malathion is problematic due to the risk for mucosal irritation, flammability of some formulations, and theoretical organophosphate poisoning, as its mechanism of action involves inhibition of acetylcholinesterase.15 However, in the context of head lice treatment, a randomized controlled trial reported no incidence of acetylcholinesterase inhibition.20 Spinosad, manufactured from the soil bacterium Saccharopolyspora spinosa, functions similarly by interfering with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and also carries a risk for skin irritation.21 Among all the treatment options, we prefer benzyl alcohol, particularly in the context of resistance, as it is effective via a physical mechanism of action and lacks notable neurotoxic effects to the host. Use of benzyl alcohol is approved for patients as young as 6 months; it functions by asphyxiating the lice via paralysis of the respiratory spiracle with occlusion by inert ingredients. Itching, episodic numbness, and scalp or mucosal irritation are possible complications of treatment.22

Treatment resistance of body lice has increased in recent years, warranting exploration of additional management strategies. Moreover, developing resistance to lindane and malathion has been reported.23 Resistance to pyrethroids has been attributed to mutations in a voltage-gated sodium channel, one of which was universally present in the sampling of a single population.24 A randomized controlled trial showed that off-label oral ivermectin 400 μg/kg was superior to malathion lotion 0.5% in difficult-to-treat cases of head lice25; utility of oral ivermectin also has been reported in body lice.26 In vitro studies also have shown promise for pursuing synergistic treatment of body lice with both ivermectin and antibiotics.27

A novel primary prophylaxis approach for at-risk homeless individuals recently utilized permethrin-impregnated underwear. Although the intervention provided short-term infestation improvement, longer-term use did not show improvement from placebo and also increased prevalence of permethrin-resistant haplotypes.2

- Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571.

- Kittler R, Kayser M, Stoneking M. Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1414-1417.

- Drali R, Mumcuoglu KY, Yesilyurt G, et al. Studies of ancient lice reveal unsuspected past migrations of vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:623-625.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J. Epidermal parasitic skin diseases: a neglected category of poverty-associated plagues. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:152-159.

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Detrez MA, et al. Prevalence of scabies and Pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112.

- Hytonen J, Khawaja T, Gronroos JO, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever in Finland in two asylum seekers from Somalia. APMIS. 2017;125:59-62.

- Nordmann T, Feldt T, Bosselmann M, et al. Outbreak of louse-borne relapsing fever among urban dwellers in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia, from July to November 2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1599-1602.

- Louni M, Mana N, Bitam I, et al. Body lice of homeless people reveal the presence of several emerging bacterial pathogens in northern Algeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006397.

- Candy K, Amanzougaghene N, Izri A, et al. Molecular survey of head and body lice, Pediculus humanus, in France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018;18:243-251.

Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2018. - Nara A, Nagai H, Yamaguchi R, et al. An unusual autopsy case of lethal hypothermia exacerbated by body lice-induced severe anemia. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:765-769.

- Althomali SA, Alzubaidi LM, Alkhaldi DM. Severe iron deficiency anaemia associated with heavy lice infestation in a young woman [published online November 5, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-212207.

- Hau V, Muhi-Iddin N. A ghost covered in lice: a case of severe blood loss with long-standing heavy pediculosis capitis infestation [published online December 19, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-206623.

- Diaz JH. Lice (Pediculosis). In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2020:3482-3486.

- Martins LG, Bernardes Filho F, Quaresma MV, et al. Dermoscopy applied to pediculosis corporis diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:513-514.

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:E1355-E1365.

- Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM. Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides: critical review and future research needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:123-136.

- Ding G, Shi R, Gao Y, et al. Pyrethroid pesticide exposure and risk of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia in Shanghai. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:13480-13487.

- Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, et al. A randomized, investigator-blinded, time-ranging study of the comparative efficacy of 0.5% malathion gel versus Ovide Lotion (0.5% malathion) or Nix Crème Rinse (1% permethrin) used as labeled, for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:405-411.

- McCormack PL. Spinosad: in pediculosis capitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:349-353.

- Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:19-24.

- Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:965-974

- Drali R, Benkouiten S, Badiaga S, et al. Detection of a knockdown resistance mutation associated with permethrin resistance in the body louse Pediculus humanus corporis by use of melting curve analysis genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2229-2233.

- Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:896-905.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476.

- Sangaré AK, Doumbo OK, Raoult D. Management and treatment of human lice [published online July 27, 2016]. Biomed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/8962685.

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279.

- Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571.

- Kittler R, Kayser M, Stoneking M. Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1414-1417.

- Drali R, Mumcuoglu KY, Yesilyurt G, et al. Studies of ancient lice reveal unsuspected past migrations of vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:623-625.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J. Epidermal parasitic skin diseases: a neglected category of poverty-associated plagues. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:152-159.

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Detrez MA, et al. Prevalence of scabies and Pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112.

- Hytonen J, Khawaja T, Gronroos JO, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever in Finland in two asylum seekers from Somalia. APMIS. 2017;125:59-62.

- Nordmann T, Feldt T, Bosselmann M, et al. Outbreak of louse-borne relapsing fever among urban dwellers in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia, from July to November 2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1599-1602.

- Louni M, Mana N, Bitam I, et al. Body lice of homeless people reveal the presence of several emerging bacterial pathogens in northern Algeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006397.

- Candy K, Amanzougaghene N, Izri A, et al. Molecular survey of head and body lice, Pediculus humanus, in France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018;18:243-251.

Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2018. - Nara A, Nagai H, Yamaguchi R, et al. An unusual autopsy case of lethal hypothermia exacerbated by body lice-induced severe anemia. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:765-769.

- Althomali SA, Alzubaidi LM, Alkhaldi DM. Severe iron deficiency anaemia associated with heavy lice infestation in a young woman [published online November 5, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-212207.

- Hau V, Muhi-Iddin N. A ghost covered in lice: a case of severe blood loss with long-standing heavy pediculosis capitis infestation [published online December 19, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-206623.

- Diaz JH. Lice (Pediculosis). In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2020:3482-3486.

- Martins LG, Bernardes Filho F, Quaresma MV, et al. Dermoscopy applied to pediculosis corporis diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:513-514.

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:E1355-E1365.

- Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM. Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides: critical review and future research needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:123-136.

- Ding G, Shi R, Gao Y, et al. Pyrethroid pesticide exposure and risk of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia in Shanghai. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:13480-13487.

- Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, et al. A randomized, investigator-blinded, time-ranging study of the comparative efficacy of 0.5% malathion gel versus Ovide Lotion (0.5% malathion) or Nix Crème Rinse (1% permethrin) used as labeled, for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:405-411.

- McCormack PL. Spinosad: in pediculosis capitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:349-353.

- Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:19-24.

- Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:965-974

- Drali R, Benkouiten S, Badiaga S, et al. Detection of a knockdown resistance mutation associated with permethrin resistance in the body louse Pediculus humanus corporis by use of melting curve analysis genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2229-2233.

- Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:896-905.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476.

- Sangaré AK, Doumbo OK, Raoult D. Management and treatment of human lice [published online July 27, 2016]. Biomed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/8962685.

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279.

Practice Points

- Body lice reside in clothing, particularly folds and seams, and migrate to the host for blood meals. To evaluate for infestation, the clinician should not only look at the skin but also closely examine the patient’s clothing. Clothes also are a target for treatment via washing in hot water.

- Due to observed and theoretical adverse effects of other chemical treatments, benzyl alcohol is the authors’ choice for treatment of head lice.

- Oral ivermectin is a promising future treatment for body lice.

In a public health crisis, obstetric collaboration is mission-critical

With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) monopolizing the news cycle, fear and misinformation are at an all-time high. Public health officials and physicians are accelerating education outreach to the public to address misinformation, and identify and care for patients who may have been exposed to the virus.

In times of public health crises, pregnant women have unique and pressing concerns about their personal health and the health of their unborn children. While not often mentioned in major news coverage, obstetricians play a critical role during health crises because of their uniquely personal role with patients during all stages of pregnancy, providing this vulnerable population with the most up-to-date information and following the latest guidelines for recommended care.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is breaking unfamiliar new ground. We know that pregnant women are at higher risk for viral infection – annually, influenza is a grim reminder that pregnant women are more immunocompromised than the general public – but we do not yet have data to confirm or refute that pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to COVID-19 than the rest of the adult population. We also do not know enough about COVID-19 transmission, including whether the virus can cross the transplacental barrier to affect a fetus, or whether it can be transmitted through breast milk.

As private practice community obstetricians work to protect their patients during this public health crisis, Ob hospitalists can play an important role in supporting them in the provision of patient care.

First, Ob hospitalists are highly-trained specialists who can help ensure that pregnant patients who seek care at the hospital – either with viral symptoms or with separate pregnancy-related concerns – are protected during triage until the treating community obstetrician can take the reins.

When a pregnant woman presents at a hospital, in most cases she will bypass the ED and instead be sent directly to the labor and delivery (L&D) unit. During a viral outbreak, there are two major concerns with this approach. For one thing, it means an immunocompromised woman is being sent through the hospital to get to L&D, and along the path, is exposed to every airborne pathogen in the facility (and, if she is already infected, exposes others along the way). In addition, in hospitals without an Ob hospitalist on site, the patient generally is not immediately triaged by a physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner upon arrival because those clinicians are not consistently on site in L&D.

In times of viral pandemics, new approaches are warranted. For hospitals with contracted L&D management with hospitalists, hospitalists work closely with department heads to implement protocols loosely based on the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) model established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Just as the ESI algorithm guides clinical stratification of patients, in times of reported viral outbreaks, L&D should consider triage of all pregnant women at higher levels of acuity, regardless of presentation status. In particular, if they show clinical symptoms, they should be masked, accompanied to the L&D unit by protected personnel, separated from other patients in areas of forced proximity such as hallways and elevators, and triaged in a secure single-patient room with a closed door (ideally at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas).

If the patient has traveled to an area of outbreak, reports exposure to travelers who have visited high-risk areas, has had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, or exhibits any clinical symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, fatigue, etc.), her care management should adhere to standing hospital emergency protocols. Following consultation with the assigned community obstetrician, the Ob hospitalist and hospital staff should contact their local/state health departments immediately for all cases of patients who show symptoms to determine if the patient meets requirements for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. The state/local health department will work with clinicians to collect, store, and ship clinical specimens appropriately. Very ill patients may need to be treated in an intensive care setting where respiratory status can be closely monitored.

At Ob Hospitalist Group, our body of evidence from our large national footprint has informed the development of standard sets of protocols for delivery complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as a cesarean section reduction toolkit to combat medically unnecessary cesarean sections. OB hospitalists therefore can assist with refining COVID-19 protocols specifically for the L&D setting, using evidence-based data to tailor protocols to address public health emergencies as they evolve.

The second way that Ob hospitalists can support their colleagues is by covering L&D 24/7 so that community obstetricians can focus on other pressing medical needs. From our experience with other outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza, we anticipate that obstetricians in private practice likely will have their hands full juggling a regular patient load, fielding calls from concerned patients, and caring for infected or ill patients who are being treated in an outpatient setting. Adding to that plate the need to rush to the hospital to clinically assess a patient for COVID-19 or for a delivery only compounds stress and exhaustion. At Ob Hospitalist Group, our hospitalist programs provide coverage and support to community obstetricians until they can arrive at the hospital or when the woman has no assigned obstetrician, reducing the pressure on community obstetricians to rush through their schedules.

Diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies are collaborating with public health officials to expedite diagnostic testing staff, hospital treatment capacity, vaccines, and even early therapies that may help to minimize severity. But right now, as clinicians work to protect their vulnerable patients, a close collaboration between community obstetricians and Ob hospitalists will help to keep patients and health care personnel safe and healthy – a goal that should apply not only to public health crises, but to the provision of maternal care every day.

Dr. Simon is chief medical officer at Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG), is a board-certified ob.gyn., and former head of the department of obstetrics and gynecology for a U.S. hospital. He has no relevant conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) monopolizing the news cycle, fear and misinformation are at an all-time high. Public health officials and physicians are accelerating education outreach to the public to address misinformation, and identify and care for patients who may have been exposed to the virus.

In times of public health crises, pregnant women have unique and pressing concerns about their personal health and the health of their unborn children. While not often mentioned in major news coverage, obstetricians play a critical role during health crises because of their uniquely personal role with patients during all stages of pregnancy, providing this vulnerable population with the most up-to-date information and following the latest guidelines for recommended care.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is breaking unfamiliar new ground. We know that pregnant women are at higher risk for viral infection – annually, influenza is a grim reminder that pregnant women are more immunocompromised than the general public – but we do not yet have data to confirm or refute that pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to COVID-19 than the rest of the adult population. We also do not know enough about COVID-19 transmission, including whether the virus can cross the transplacental barrier to affect a fetus, or whether it can be transmitted through breast milk.

As private practice community obstetricians work to protect their patients during this public health crisis, Ob hospitalists can play an important role in supporting them in the provision of patient care.

First, Ob hospitalists are highly-trained specialists who can help ensure that pregnant patients who seek care at the hospital – either with viral symptoms or with separate pregnancy-related concerns – are protected during triage until the treating community obstetrician can take the reins.

When a pregnant woman presents at a hospital, in most cases she will bypass the ED and instead be sent directly to the labor and delivery (L&D) unit. During a viral outbreak, there are two major concerns with this approach. For one thing, it means an immunocompromised woman is being sent through the hospital to get to L&D, and along the path, is exposed to every airborne pathogen in the facility (and, if she is already infected, exposes others along the way). In addition, in hospitals without an Ob hospitalist on site, the patient generally is not immediately triaged by a physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner upon arrival because those clinicians are not consistently on site in L&D.

In times of viral pandemics, new approaches are warranted. For hospitals with contracted L&D management with hospitalists, hospitalists work closely with department heads to implement protocols loosely based on the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) model established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Just as the ESI algorithm guides clinical stratification of patients, in times of reported viral outbreaks, L&D should consider triage of all pregnant women at higher levels of acuity, regardless of presentation status. In particular, if they show clinical symptoms, they should be masked, accompanied to the L&D unit by protected personnel, separated from other patients in areas of forced proximity such as hallways and elevators, and triaged in a secure single-patient room with a closed door (ideally at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas).

If the patient has traveled to an area of outbreak, reports exposure to travelers who have visited high-risk areas, has had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, or exhibits any clinical symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, fatigue, etc.), her care management should adhere to standing hospital emergency protocols. Following consultation with the assigned community obstetrician, the Ob hospitalist and hospital staff should contact their local/state health departments immediately for all cases of patients who show symptoms to determine if the patient meets requirements for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. The state/local health department will work with clinicians to collect, store, and ship clinical specimens appropriately. Very ill patients may need to be treated in an intensive care setting where respiratory status can be closely monitored.

At Ob Hospitalist Group, our body of evidence from our large national footprint has informed the development of standard sets of protocols for delivery complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as a cesarean section reduction toolkit to combat medically unnecessary cesarean sections. OB hospitalists therefore can assist with refining COVID-19 protocols specifically for the L&D setting, using evidence-based data to tailor protocols to address public health emergencies as they evolve.