User login

Consider C. difficile early in children with cancer with GI symptoms

Children with cancer are at increased risk of potentially life-threatening Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI), and Brianna Murphy, DO, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

CDI are characterized by diarrhea, fever, and loss of appetite. The clinical features are caused by the release of toxins A and B by this gram-positive bacterium. In pediatric groups, CDI are a leading cause of antibiotic-associated gastric illness. This in turn can lead to a protracted stay in hospital and increases risk of mortality. The rising incidence in the United States over the last 2 decades prompted Dr. Murphy, a pediatric hematology oncology fellow working at the department of pediatric research at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to investigate further. A search of the literature found limited information regarding CDI and pediatric oncology patients.

Recognized factors for contracting CDI include the presence of other illnesses, a weakened immune system because of drugs or disease, enteral nutrition, usage of medicines such as proton pump inhibitors which decrease gastric acid production, and classically, treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics.

Dr. Murphy’s study included patients aged 1-18 years, all of whom had a cancer diagnosis and a positive stool culture for C. difficile. Presenting symptoms were three or more loose stools per day or acute onset ileus. The study evaluated data for the years 2000-2017 and included 11,366 children; 207 CDI (0.98%) cases were identified among pediatric oncology patients during the study period. This compares with historical data showing an incidence of 0.14% among hospitalized children in general.

Malignancy data were then subdivided into three groups: hematologic, nonneural solid tumors (NNST), and neural tumors. Hematologic malignancies had a CDI prevalence higher than the average for oncologic patients at 5.4%. Inside this group those suffering with acute myeloid leukemia had a rate of 10.5%. In the NNST and neural tumor groups, CDI rates were lower and closer to the overall average.

Dr. Murphy then looked at her patient population in more detail. Poor clinical outcomes (PCOs) were defined as severe, refractory, recurrent, or multiple infections. Severe CDI included features such as toxic megacolon, gastrointestinal perforation, or need for surgical intervention. Refractory CDI were defined as continuation of symptoms beyond 7 days of appropriate therapy, and recurrent CDI were classed as reinfection within 8 weeks of a previous CDI. Ultimately, 51% of patients in this study died. Patients with severe CDI experienced increased mortality (P = .02). There was no difference shown when looking at the type of cancer, age, gender, or patient ethnicity.

Next, Dr. Murphy looked for associations. Hematologic and biochemical testing identified that elevated creatinine was statistically associated with the likelihood of PCOs, compared with leukocytosis and neutropenia, particularly in the NNST group. Treatment modality also was studied. Here radiation therapy was the only treatment shown to increase PCOs in patients with CDI. One-fifth (22%) of radiation therapy recipients experienced multiple CDI, compared with 12% of the total population.

In commenting on her paper, Louis Bent, MD, from the Netherlands raised the issue of deaths in septic patients. What was the origin of the responsible organism, for example from the GI tract or from central lines, and were patients receiving appropriate antibiotic treatment?

Dr. Kelly responded that sepsis was generally believed to occur as a result of infection with mixed bacterial translocation through the bowel wall, notably Escherichia coli. Patients were usually on a cocktail of antibiotics targeting CDI, but also other infections illustrating the serious nature of the situation.

Dr. Murphy had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Children with cancer are at increased risk of potentially life-threatening Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI), and Brianna Murphy, DO, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

CDI are characterized by diarrhea, fever, and loss of appetite. The clinical features are caused by the release of toxins A and B by this gram-positive bacterium. In pediatric groups, CDI are a leading cause of antibiotic-associated gastric illness. This in turn can lead to a protracted stay in hospital and increases risk of mortality. The rising incidence in the United States over the last 2 decades prompted Dr. Murphy, a pediatric hematology oncology fellow working at the department of pediatric research at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to investigate further. A search of the literature found limited information regarding CDI and pediatric oncology patients.

Recognized factors for contracting CDI include the presence of other illnesses, a weakened immune system because of drugs or disease, enteral nutrition, usage of medicines such as proton pump inhibitors which decrease gastric acid production, and classically, treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics.

Dr. Murphy’s study included patients aged 1-18 years, all of whom had a cancer diagnosis and a positive stool culture for C. difficile. Presenting symptoms were three or more loose stools per day or acute onset ileus. The study evaluated data for the years 2000-2017 and included 11,366 children; 207 CDI (0.98%) cases were identified among pediatric oncology patients during the study period. This compares with historical data showing an incidence of 0.14% among hospitalized children in general.

Malignancy data were then subdivided into three groups: hematologic, nonneural solid tumors (NNST), and neural tumors. Hematologic malignancies had a CDI prevalence higher than the average for oncologic patients at 5.4%. Inside this group those suffering with acute myeloid leukemia had a rate of 10.5%. In the NNST and neural tumor groups, CDI rates were lower and closer to the overall average.

Dr. Murphy then looked at her patient population in more detail. Poor clinical outcomes (PCOs) were defined as severe, refractory, recurrent, or multiple infections. Severe CDI included features such as toxic megacolon, gastrointestinal perforation, or need for surgical intervention. Refractory CDI were defined as continuation of symptoms beyond 7 days of appropriate therapy, and recurrent CDI were classed as reinfection within 8 weeks of a previous CDI. Ultimately, 51% of patients in this study died. Patients with severe CDI experienced increased mortality (P = .02). There was no difference shown when looking at the type of cancer, age, gender, or patient ethnicity.

Next, Dr. Murphy looked for associations. Hematologic and biochemical testing identified that elevated creatinine was statistically associated with the likelihood of PCOs, compared with leukocytosis and neutropenia, particularly in the NNST group. Treatment modality also was studied. Here radiation therapy was the only treatment shown to increase PCOs in patients with CDI. One-fifth (22%) of radiation therapy recipients experienced multiple CDI, compared with 12% of the total population.

In commenting on her paper, Louis Bent, MD, from the Netherlands raised the issue of deaths in septic patients. What was the origin of the responsible organism, for example from the GI tract or from central lines, and were patients receiving appropriate antibiotic treatment?

Dr. Kelly responded that sepsis was generally believed to occur as a result of infection with mixed bacterial translocation through the bowel wall, notably Escherichia coli. Patients were usually on a cocktail of antibiotics targeting CDI, but also other infections illustrating the serious nature of the situation.

Dr. Murphy had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Children with cancer are at increased risk of potentially life-threatening Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI), and Brianna Murphy, DO, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

CDI are characterized by diarrhea, fever, and loss of appetite. The clinical features are caused by the release of toxins A and B by this gram-positive bacterium. In pediatric groups, CDI are a leading cause of antibiotic-associated gastric illness. This in turn can lead to a protracted stay in hospital and increases risk of mortality. The rising incidence in the United States over the last 2 decades prompted Dr. Murphy, a pediatric hematology oncology fellow working at the department of pediatric research at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to investigate further. A search of the literature found limited information regarding CDI and pediatric oncology patients.

Recognized factors for contracting CDI include the presence of other illnesses, a weakened immune system because of drugs or disease, enteral nutrition, usage of medicines such as proton pump inhibitors which decrease gastric acid production, and classically, treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics.

Dr. Murphy’s study included patients aged 1-18 years, all of whom had a cancer diagnosis and a positive stool culture for C. difficile. Presenting symptoms were three or more loose stools per day or acute onset ileus. The study evaluated data for the years 2000-2017 and included 11,366 children; 207 CDI (0.98%) cases were identified among pediatric oncology patients during the study period. This compares with historical data showing an incidence of 0.14% among hospitalized children in general.

Malignancy data were then subdivided into three groups: hematologic, nonneural solid tumors (NNST), and neural tumors. Hematologic malignancies had a CDI prevalence higher than the average for oncologic patients at 5.4%. Inside this group those suffering with acute myeloid leukemia had a rate of 10.5%. In the NNST and neural tumor groups, CDI rates were lower and closer to the overall average.

Dr. Murphy then looked at her patient population in more detail. Poor clinical outcomes (PCOs) were defined as severe, refractory, recurrent, or multiple infections. Severe CDI included features such as toxic megacolon, gastrointestinal perforation, or need for surgical intervention. Refractory CDI were defined as continuation of symptoms beyond 7 days of appropriate therapy, and recurrent CDI were classed as reinfection within 8 weeks of a previous CDI. Ultimately, 51% of patients in this study died. Patients with severe CDI experienced increased mortality (P = .02). There was no difference shown when looking at the type of cancer, age, gender, or patient ethnicity.

Next, Dr. Murphy looked for associations. Hematologic and biochemical testing identified that elevated creatinine was statistically associated with the likelihood of PCOs, compared with leukocytosis and neutropenia, particularly in the NNST group. Treatment modality also was studied. Here radiation therapy was the only treatment shown to increase PCOs in patients with CDI. One-fifth (22%) of radiation therapy recipients experienced multiple CDI, compared with 12% of the total population.

In commenting on her paper, Louis Bent, MD, from the Netherlands raised the issue of deaths in septic patients. What was the origin of the responsible organism, for example from the GI tract or from central lines, and were patients receiving appropriate antibiotic treatment?

Dr. Kelly responded that sepsis was generally believed to occur as a result of infection with mixed bacterial translocation through the bowel wall, notably Escherichia coli. Patients were usually on a cocktail of antibiotics targeting CDI, but also other infections illustrating the serious nature of the situation.

Dr. Murphy had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

FROM ESPID 2020

Should we use antibiotics to treat sore throats?

The use of antibiotics to treat a sore throat remains contentious, with guidelines from around the world providing contradictory advice. This topic generated a lively debate at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Lauri Ivaska, MD, of the department of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at Turku (Finland) University Hospital, argued for the use of antibiotics, while Borbála Zsigmond, MD, of Heim Pál Children’s Hospital in Budapest, made the case against their use. Interestingly, this debate occurred against the background of a poll conducted before the debate, which found that only 11% of the audience voted in favor of using antibiotics to treat sore throats.

Both speakers began by exploring their approach to the treatment of a recent clinical case involving a 4-year-old girl presenting with sore throat. Dr. Ivaska stressed the difference between a sore throat, pharyngitis, and tonsillitis: the latter two refer to a physical finding, while the former is a subjective symptom.

International guidelines differ on the subject

The debate moved to discussing the international guidelines for treating pharyngitis and tonsillitis. Dr. Zsigmond believes that these are flawed and unhelpful, arguing that they differ depending on what part of the world a physician is practicing in. For example, the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend using best clinical judgment and then backing this up by testing. If testing proves positive for group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS), the physician should universally treat. By comparison, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Sore Throat Guideline Group focuses on severity rather than the cause of the infection. If the case is deemed to be serious, antibiotics can be prescribed without a positive test.

Sore throat is frequently associated with a common cold. In a recent study, more that 80% of students with an acute viral respiratory tract infection had soreness at the beginning of their illness.

Reporting from his own research, Dr. Ivaska argued that viruses can be detected in almost two-thirds of children with pharyngitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. He thinks antibiotics should be reserved for those 30%-40% of patients with a confirmed GAS infection. The potential role of Fusobacterium necrophorum was raised, but there is no evidence of the benefits of antibiotic treatment in such cases.

There are diagnostic aids for GAS infection

It was suggested that, instead of concentrating on sore throat, the debate should be about whether to use antibiotics to treat GAS infection. But how can the diagnosis be confirmed simply in a clinical setting? Dr. Ivaska recommended adopting diagnostic aids such as Centor, McIsaac, and FeverPAIN, which award scores for several common disease features – the higher the score, the more likely a patient is to be suffering from a GAS infection.

Dr. Zsigmond also likes scoring symptoms but believes they are often inaccurate, especially in young children. She pointed to a report that examined the use of the Centor tool among 441 children attending a pediatric ED. The authors concluded that the Centor criteria were ineffective in predicting a positive GAS culture in throat swabs taken from symptomatic patients.

When are antibiotics warranted?

It is widely accepted that antibiotics should be avoided for viral infections. Returning to the case described at the start of this debate, Dr. Zsigmond calculated that her patient with a 2-day history of sore throat, elevated temperature, pussy tonsils, and enlarged cervical lymph glands but no cough or rhinitis had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and a Centor score of 4, meaning that, according to the European guidelines, she should receive antibiotic treatment. However, viral swabs proved positive for adenovirus.

Dr. Ivaska responded with his recent experiences of a similar case, where a 5-year-old boy had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and Centor score of 3. Cultures from his throat were GAS positive, illustrating the problem of differentiating between bacterial and viral infections.

But does a GAS-positive pharyngeal culture necessarily mean that antibiotic treatment is indicated? Dr. Ivaska believes it does, citing the importance of preventing serious complications such as rheumatic fever. Dr. Zsigmind countered by pointing out the low levels of acute rheumatic fever in developed nations. In her own country, Hungary, there has not been a case in the last 30 years. Giving antibiotics for historical reasons cannot, in her view, be justified.

Dr. Ivaska responded that perhaps this is because of early treatment in children with sore throats.

Another complication of tonsillitis is quinsy. Dr. Zsigmond cited a study showing that there is no statistically significant evidence demonstrating that antibiotics prevent quinsy. She attributed this to quinsy appearing quickly, typically within 2 days. Delay in seeking help means that the window to treat is often missed. However, should symptoms present early, there is no statistical evidence that prior antibiotic use can prevent quinsy. Also, given the rarity of this condition, prevention would mean excessive use of antibiotics.

Are there other possible benefits of antibiotic treatment in patients with a sore throat? Dr. Ivaska referred to a Cochrane review that found a shortening in duration of throat soreness and fever. Furthermore, compared with placebo, antibiotics reduced the incidence of suppurative complications such as acute otitis media and sinusitis following a sore throat. Other studies have also pointed to the potential benefits of reduced transmission in families where one member with pharyngitis was GAS positive.

As the debate ended, Dr. Zsigmond reported evidence of global antibiotic overprescribing for sore throat ranging from 53% in Europe to 94% in Australia. She also highlighted risks such as altered gut flora, drug resistance, and rashes.

Robin Marlow from the University of Bristol (England), PhD, MBBS, commented that “one of the most enjoyable parts of the ESPID meeting is hearing different viewpoints rationally explained from across the world. As [antibiotic prescription for a sore throat is] a clinical conundrum that faces pediatricians every day, I thought this debate was a really great example of how, despite our different health care systems and ways of working, we are all striving together to improve children’s health using the best evidence available.”

The presenters had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

The use of antibiotics to treat a sore throat remains contentious, with guidelines from around the world providing contradictory advice. This topic generated a lively debate at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Lauri Ivaska, MD, of the department of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at Turku (Finland) University Hospital, argued for the use of antibiotics, while Borbála Zsigmond, MD, of Heim Pál Children’s Hospital in Budapest, made the case against their use. Interestingly, this debate occurred against the background of a poll conducted before the debate, which found that only 11% of the audience voted in favor of using antibiotics to treat sore throats.

Both speakers began by exploring their approach to the treatment of a recent clinical case involving a 4-year-old girl presenting with sore throat. Dr. Ivaska stressed the difference between a sore throat, pharyngitis, and tonsillitis: the latter two refer to a physical finding, while the former is a subjective symptom.

International guidelines differ on the subject

The debate moved to discussing the international guidelines for treating pharyngitis and tonsillitis. Dr. Zsigmond believes that these are flawed and unhelpful, arguing that they differ depending on what part of the world a physician is practicing in. For example, the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend using best clinical judgment and then backing this up by testing. If testing proves positive for group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS), the physician should universally treat. By comparison, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Sore Throat Guideline Group focuses on severity rather than the cause of the infection. If the case is deemed to be serious, antibiotics can be prescribed without a positive test.

Sore throat is frequently associated with a common cold. In a recent study, more that 80% of students with an acute viral respiratory tract infection had soreness at the beginning of their illness.

Reporting from his own research, Dr. Ivaska argued that viruses can be detected in almost two-thirds of children with pharyngitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. He thinks antibiotics should be reserved for those 30%-40% of patients with a confirmed GAS infection. The potential role of Fusobacterium necrophorum was raised, but there is no evidence of the benefits of antibiotic treatment in such cases.

There are diagnostic aids for GAS infection

It was suggested that, instead of concentrating on sore throat, the debate should be about whether to use antibiotics to treat GAS infection. But how can the diagnosis be confirmed simply in a clinical setting? Dr. Ivaska recommended adopting diagnostic aids such as Centor, McIsaac, and FeverPAIN, which award scores for several common disease features – the higher the score, the more likely a patient is to be suffering from a GAS infection.

Dr. Zsigmond also likes scoring symptoms but believes they are often inaccurate, especially in young children. She pointed to a report that examined the use of the Centor tool among 441 children attending a pediatric ED. The authors concluded that the Centor criteria were ineffective in predicting a positive GAS culture in throat swabs taken from symptomatic patients.

When are antibiotics warranted?

It is widely accepted that antibiotics should be avoided for viral infections. Returning to the case described at the start of this debate, Dr. Zsigmond calculated that her patient with a 2-day history of sore throat, elevated temperature, pussy tonsils, and enlarged cervical lymph glands but no cough or rhinitis had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and a Centor score of 4, meaning that, according to the European guidelines, she should receive antibiotic treatment. However, viral swabs proved positive for adenovirus.

Dr. Ivaska responded with his recent experiences of a similar case, where a 5-year-old boy had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and Centor score of 3. Cultures from his throat were GAS positive, illustrating the problem of differentiating between bacterial and viral infections.

But does a GAS-positive pharyngeal culture necessarily mean that antibiotic treatment is indicated? Dr. Ivaska believes it does, citing the importance of preventing serious complications such as rheumatic fever. Dr. Zsigmind countered by pointing out the low levels of acute rheumatic fever in developed nations. In her own country, Hungary, there has not been a case in the last 30 years. Giving antibiotics for historical reasons cannot, in her view, be justified.

Dr. Ivaska responded that perhaps this is because of early treatment in children with sore throats.

Another complication of tonsillitis is quinsy. Dr. Zsigmond cited a study showing that there is no statistically significant evidence demonstrating that antibiotics prevent quinsy. She attributed this to quinsy appearing quickly, typically within 2 days. Delay in seeking help means that the window to treat is often missed. However, should symptoms present early, there is no statistical evidence that prior antibiotic use can prevent quinsy. Also, given the rarity of this condition, prevention would mean excessive use of antibiotics.

Are there other possible benefits of antibiotic treatment in patients with a sore throat? Dr. Ivaska referred to a Cochrane review that found a shortening in duration of throat soreness and fever. Furthermore, compared with placebo, antibiotics reduced the incidence of suppurative complications such as acute otitis media and sinusitis following a sore throat. Other studies have also pointed to the potential benefits of reduced transmission in families where one member with pharyngitis was GAS positive.

As the debate ended, Dr. Zsigmond reported evidence of global antibiotic overprescribing for sore throat ranging from 53% in Europe to 94% in Australia. She also highlighted risks such as altered gut flora, drug resistance, and rashes.

Robin Marlow from the University of Bristol (England), PhD, MBBS, commented that “one of the most enjoyable parts of the ESPID meeting is hearing different viewpoints rationally explained from across the world. As [antibiotic prescription for a sore throat is] a clinical conundrum that faces pediatricians every day, I thought this debate was a really great example of how, despite our different health care systems and ways of working, we are all striving together to improve children’s health using the best evidence available.”

The presenters had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

The use of antibiotics to treat a sore throat remains contentious, with guidelines from around the world providing contradictory advice. This topic generated a lively debate at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Lauri Ivaska, MD, of the department of pediatrics and adolescent medicine at Turku (Finland) University Hospital, argued for the use of antibiotics, while Borbála Zsigmond, MD, of Heim Pál Children’s Hospital in Budapest, made the case against their use. Interestingly, this debate occurred against the background of a poll conducted before the debate, which found that only 11% of the audience voted in favor of using antibiotics to treat sore throats.

Both speakers began by exploring their approach to the treatment of a recent clinical case involving a 4-year-old girl presenting with sore throat. Dr. Ivaska stressed the difference between a sore throat, pharyngitis, and tonsillitis: the latter two refer to a physical finding, while the former is a subjective symptom.

International guidelines differ on the subject

The debate moved to discussing the international guidelines for treating pharyngitis and tonsillitis. Dr. Zsigmond believes that these are flawed and unhelpful, arguing that they differ depending on what part of the world a physician is practicing in. For example, the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend using best clinical judgment and then backing this up by testing. If testing proves positive for group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS), the physician should universally treat. By comparison, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Sore Throat Guideline Group focuses on severity rather than the cause of the infection. If the case is deemed to be serious, antibiotics can be prescribed without a positive test.

Sore throat is frequently associated with a common cold. In a recent study, more that 80% of students with an acute viral respiratory tract infection had soreness at the beginning of their illness.

Reporting from his own research, Dr. Ivaska argued that viruses can be detected in almost two-thirds of children with pharyngitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. He thinks antibiotics should be reserved for those 30%-40% of patients with a confirmed GAS infection. The potential role of Fusobacterium necrophorum was raised, but there is no evidence of the benefits of antibiotic treatment in such cases.

There are diagnostic aids for GAS infection

It was suggested that, instead of concentrating on sore throat, the debate should be about whether to use antibiotics to treat GAS infection. But how can the diagnosis be confirmed simply in a clinical setting? Dr. Ivaska recommended adopting diagnostic aids such as Centor, McIsaac, and FeverPAIN, which award scores for several common disease features – the higher the score, the more likely a patient is to be suffering from a GAS infection.

Dr. Zsigmond also likes scoring symptoms but believes they are often inaccurate, especially in young children. She pointed to a report that examined the use of the Centor tool among 441 children attending a pediatric ED. The authors concluded that the Centor criteria were ineffective in predicting a positive GAS culture in throat swabs taken from symptomatic patients.

When are antibiotics warranted?

It is widely accepted that antibiotics should be avoided for viral infections. Returning to the case described at the start of this debate, Dr. Zsigmond calculated that her patient with a 2-day history of sore throat, elevated temperature, pussy tonsils, and enlarged cervical lymph glands but no cough or rhinitis had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and a Centor score of 4, meaning that, according to the European guidelines, she should receive antibiotic treatment. However, viral swabs proved positive for adenovirus.

Dr. Ivaska responded with his recent experiences of a similar case, where a 5-year-old boy had a FeverPAIN score of 4-5 and Centor score of 3. Cultures from his throat were GAS positive, illustrating the problem of differentiating between bacterial and viral infections.

But does a GAS-positive pharyngeal culture necessarily mean that antibiotic treatment is indicated? Dr. Ivaska believes it does, citing the importance of preventing serious complications such as rheumatic fever. Dr. Zsigmind countered by pointing out the low levels of acute rheumatic fever in developed nations. In her own country, Hungary, there has not been a case in the last 30 years. Giving antibiotics for historical reasons cannot, in her view, be justified.

Dr. Ivaska responded that perhaps this is because of early treatment in children with sore throats.

Another complication of tonsillitis is quinsy. Dr. Zsigmond cited a study showing that there is no statistically significant evidence demonstrating that antibiotics prevent quinsy. She attributed this to quinsy appearing quickly, typically within 2 days. Delay in seeking help means that the window to treat is often missed. However, should symptoms present early, there is no statistical evidence that prior antibiotic use can prevent quinsy. Also, given the rarity of this condition, prevention would mean excessive use of antibiotics.

Are there other possible benefits of antibiotic treatment in patients with a sore throat? Dr. Ivaska referred to a Cochrane review that found a shortening in duration of throat soreness and fever. Furthermore, compared with placebo, antibiotics reduced the incidence of suppurative complications such as acute otitis media and sinusitis following a sore throat. Other studies have also pointed to the potential benefits of reduced transmission in families where one member with pharyngitis was GAS positive.

As the debate ended, Dr. Zsigmond reported evidence of global antibiotic overprescribing for sore throat ranging from 53% in Europe to 94% in Australia. She also highlighted risks such as altered gut flora, drug resistance, and rashes.

Robin Marlow from the University of Bristol (England), PhD, MBBS, commented that “one of the most enjoyable parts of the ESPID meeting is hearing different viewpoints rationally explained from across the world. As [antibiotic prescription for a sore throat is] a clinical conundrum that faces pediatricians every day, I thought this debate was a really great example of how, despite our different health care systems and ways of working, we are all striving together to improve children’s health using the best evidence available.”

The presenters had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

FROM ESPID 2020

Vaccine-preventable infection risk high for pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients

Vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients cause significant morbidity, health care burden, and mortality.

Dana Danino, MD, and colleagues presented their evaluation of the prevalence and epidemiology of pediatric VPI-associated hospitalizations occurring within 5 years post HCT at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

“Pediatric HCT recipients are at increased risk of VPIs, and HCT recipients have poor outcomes from VPIs, compared with the general population,” explained Dr. Danino, of the department of pediatrics, and divisions of infectious diseases and host defense at the Ohio State University, Columbus. “However, the contemporary prevalence, risk factors, morbidity and mortality resulting from VPIs in children post HCT are not well known.”

Their epidemiological study, using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, identified all children under 18 years that underwent allogeneic or autologous HCT in an 8-year period. A total of 9,591 unique HCT recipients were identified.

The researchers demonstrated that 7.1% of this cohort were hospitalized for a VPI in the first 5 years post HCT. Dr. Danino explained that 67% of VPI hospitalizations occurred during the first year, at a median of 222 days, and 22% of VPIs occurred during the initial HCT admission.

As to the type of infection, Dr. Danino and colleagues found that, the prevalence of VPI hospitalizations were highest for influenza, followed by varicella and invasive pneumococcal infections. They identified no hospitalizations due to measles or rubella during the study period.

The study findings revealed that the influenza infections occurred a median 231 days post HCT; varicella infections occurred a median 190 days; and invasive pneumococcal infections occurred a median 311 days post HCT.

“When we did a multivariate analysis by time post HCT, we found that age at transplantation, primary immune deficiency as an indication for transplantation, and graft versus host disease were independent predictors of VPIs during the initial HCT admission,” said Dr. Danino.

Children with a VPI who spent longer in hospital were more likely to be admitted to an ICU and have higher mortality, compared with children without a VPI diagnosis.

“VPIs led to longer duration of hospitalization, higher rates of ICU admission, and higher mortality, compared to HCT recipients without VPIs,” Dr. Danino explained. It was not possible in this retrospective study to determine whether increased mortality was VPI related.

These results underline the seriousness of infections in vulnerable children after HCT. Dr. Danino concluded by saying that “efforts to optimize vaccination strategies early post HCT are warranted to decrease VPIs.”

Dr. Danino had nothing to disclose.

Vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients cause significant morbidity, health care burden, and mortality.

Dana Danino, MD, and colleagues presented their evaluation of the prevalence and epidemiology of pediatric VPI-associated hospitalizations occurring within 5 years post HCT at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

“Pediatric HCT recipients are at increased risk of VPIs, and HCT recipients have poor outcomes from VPIs, compared with the general population,” explained Dr. Danino, of the department of pediatrics, and divisions of infectious diseases and host defense at the Ohio State University, Columbus. “However, the contemporary prevalence, risk factors, morbidity and mortality resulting from VPIs in children post HCT are not well known.”

Their epidemiological study, using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, identified all children under 18 years that underwent allogeneic or autologous HCT in an 8-year period. A total of 9,591 unique HCT recipients were identified.

The researchers demonstrated that 7.1% of this cohort were hospitalized for a VPI in the first 5 years post HCT. Dr. Danino explained that 67% of VPI hospitalizations occurred during the first year, at a median of 222 days, and 22% of VPIs occurred during the initial HCT admission.

As to the type of infection, Dr. Danino and colleagues found that, the prevalence of VPI hospitalizations were highest for influenza, followed by varicella and invasive pneumococcal infections. They identified no hospitalizations due to measles or rubella during the study period.

The study findings revealed that the influenza infections occurred a median 231 days post HCT; varicella infections occurred a median 190 days; and invasive pneumococcal infections occurred a median 311 days post HCT.

“When we did a multivariate analysis by time post HCT, we found that age at transplantation, primary immune deficiency as an indication for transplantation, and graft versus host disease were independent predictors of VPIs during the initial HCT admission,” said Dr. Danino.

Children with a VPI who spent longer in hospital were more likely to be admitted to an ICU and have higher mortality, compared with children without a VPI diagnosis.

“VPIs led to longer duration of hospitalization, higher rates of ICU admission, and higher mortality, compared to HCT recipients without VPIs,” Dr. Danino explained. It was not possible in this retrospective study to determine whether increased mortality was VPI related.

These results underline the seriousness of infections in vulnerable children after HCT. Dr. Danino concluded by saying that “efforts to optimize vaccination strategies early post HCT are warranted to decrease VPIs.”

Dr. Danino had nothing to disclose.

Vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients cause significant morbidity, health care burden, and mortality.

Dana Danino, MD, and colleagues presented their evaluation of the prevalence and epidemiology of pediatric VPI-associated hospitalizations occurring within 5 years post HCT at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

“Pediatric HCT recipients are at increased risk of VPIs, and HCT recipients have poor outcomes from VPIs, compared with the general population,” explained Dr. Danino, of the department of pediatrics, and divisions of infectious diseases and host defense at the Ohio State University, Columbus. “However, the contemporary prevalence, risk factors, morbidity and mortality resulting from VPIs in children post HCT are not well known.”

Their epidemiological study, using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, identified all children under 18 years that underwent allogeneic or autologous HCT in an 8-year period. A total of 9,591 unique HCT recipients were identified.

The researchers demonstrated that 7.1% of this cohort were hospitalized for a VPI in the first 5 years post HCT. Dr. Danino explained that 67% of VPI hospitalizations occurred during the first year, at a median of 222 days, and 22% of VPIs occurred during the initial HCT admission.

As to the type of infection, Dr. Danino and colleagues found that, the prevalence of VPI hospitalizations were highest for influenza, followed by varicella and invasive pneumococcal infections. They identified no hospitalizations due to measles or rubella during the study period.

The study findings revealed that the influenza infections occurred a median 231 days post HCT; varicella infections occurred a median 190 days; and invasive pneumococcal infections occurred a median 311 days post HCT.

“When we did a multivariate analysis by time post HCT, we found that age at transplantation, primary immune deficiency as an indication for transplantation, and graft versus host disease were independent predictors of VPIs during the initial HCT admission,” said Dr. Danino.

Children with a VPI who spent longer in hospital were more likely to be admitted to an ICU and have higher mortality, compared with children without a VPI diagnosis.

“VPIs led to longer duration of hospitalization, higher rates of ICU admission, and higher mortality, compared to HCT recipients without VPIs,” Dr. Danino explained. It was not possible in this retrospective study to determine whether increased mortality was VPI related.

These results underline the seriousness of infections in vulnerable children after HCT. Dr. Danino concluded by saying that “efforts to optimize vaccination strategies early post HCT are warranted to decrease VPIs.”

Dr. Danino had nothing to disclose.

FROM ESPID 2020

COVID-19 vaccines: Safe for immunocompromised patients?

Coronavirus vaccines have become a reality, as they are now being approved and authorized for use in a growing number of countries including the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has just issued emergency authorization for the use of the COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech. Close behind is the vaccine developed by Moderna, which has also applied to the FDA for emergency authorization.

The efficacy of a two-dose administration of the vaccine has been pegged at 95.0%, and the FDA has said that the 95% credible interval for the vaccine efficacy was 90.3%-97.6%. But as with many initial clinical trials, whether for drugs or vaccines, not all populations were represented in the trial cohort, including individuals who are immunocompromised. At the current time, it is largely unknown how safe or effective the vaccine may be in this large population, many of whom are at high risk for serious COVID-19 complications.

At a special session held during the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, said that individuals with compromised immune systems, whether because of chemotherapy or a bone marrow transplant, should plan to be vaccinated when the opportunity arises.

In response to a question from ASH President Stephanie J. Lee, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Dr. Fauci emphasized that, despite being excluded from clinical trials, this population should get vaccinated. “I think we should recommend that they get vaccinated,” he said. “I mean, it is clear that, if you are on immunosuppressive agents, history tells us that you’re not going to have as robust a response as if you had an intact immune system that was not being compromised. But some degree of immunity is better than no degree of immunity.”

That does seem to be the consensus among experts who spoke in interviews: that as long as these are not live attenuated vaccines, they hold no specific risk to an immunocompromised patient, other than any factors specific to the individual that could be a contraindication.

“Patients, family members, friends, and work contacts should be encouraged to receive the vaccine,” said William Stohl, MD, PhD, chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Clinicians should advise patients to obtain the vaccine sooner rather than later.”

Kevin C. Wang, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, agreed. “I am 100% with Dr. Fauci. Everyone should get the vaccine, even if it may not be as effective,” he said. “I would treat it exactly like the flu vaccines that we recommend folks get every year.”

Dr. Wang noted that he couldn’t think of any contraindications unless the immunosuppressed patients have a history of severe allergic reactions to prior vaccinations. “But I would even say patients with history of cancer, upon recommendation of their oncologists, are likely to be suitable candidates for the vaccine,” he added. “I would say clinicians should approach counseling the same way they counsel patients for the flu vaccine, and as far as I know, there are no concerns for systemic drugs commonly used in dermatology patients.”

However, guidance has not yet been issued from either the FDA or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regarding the use of the vaccine in immunocompromised individuals. Given the lack of data, the FDA has said that “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis,” and that individuals should consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has said that clinicians need more guidance on whether to use the vaccine in pregnant or breastfeeding women, the immunocompromised, or those who have a history of allergies. The CDC itself has not yet released its formal guidance on vaccine use.

COVID-19 vaccines

Vaccines typically require years of research and testing before reaching the clinic, but this year researchers embarked on a global effort to develop safe and effective coronavirus vaccines in record time. Both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines have only a few months of phase 3 clinical trial data, so much remains unknown about them, including their duration of effect and any long-term safety signals. In addition to excluding immunocompromised individuals, the clinical trials did not include children or pregnant women, so data are lacking for several population subgroups.

But these will not be the only vaccines available, as the pipeline is already becoming crowded. U.S. clinical trial data from a vaccine jointly being developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca, could potentially be ready, along with a request for FDA emergency use authorization, by late January 2021.

In addition, China and Russia have released vaccines, and there are currently 61 vaccines being investigated in clinical trials and at least 85 preclinical products under active investigation.

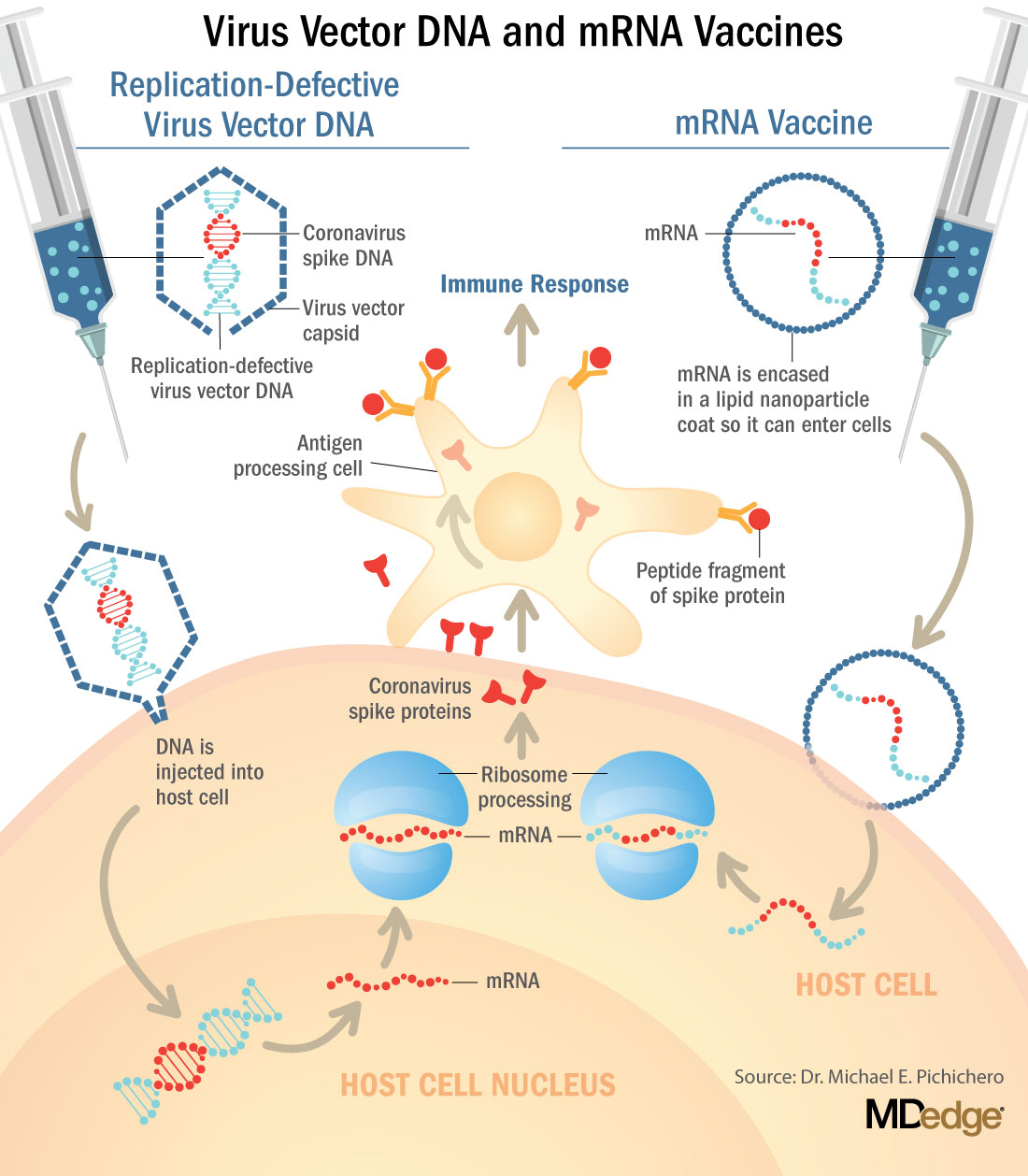

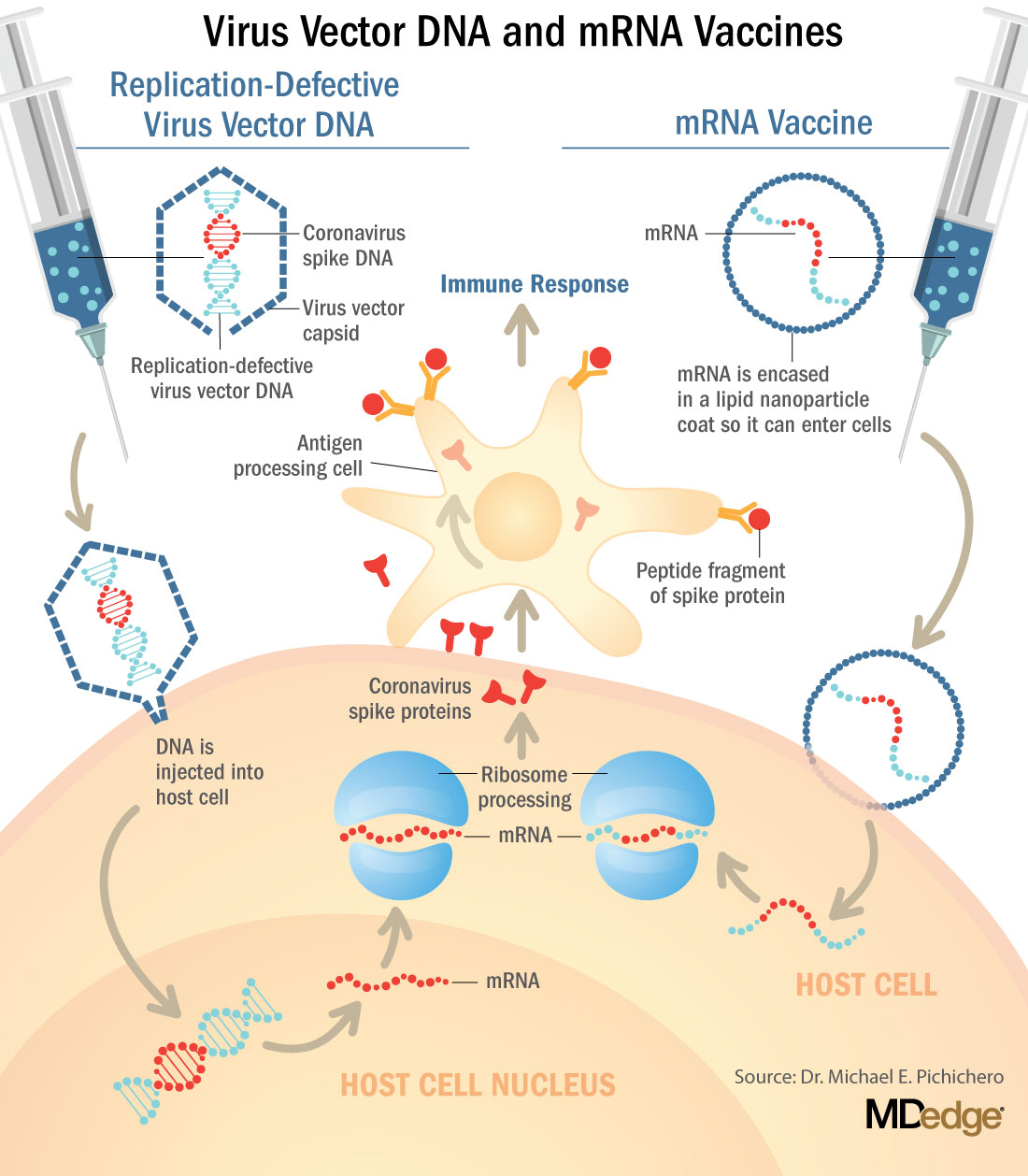

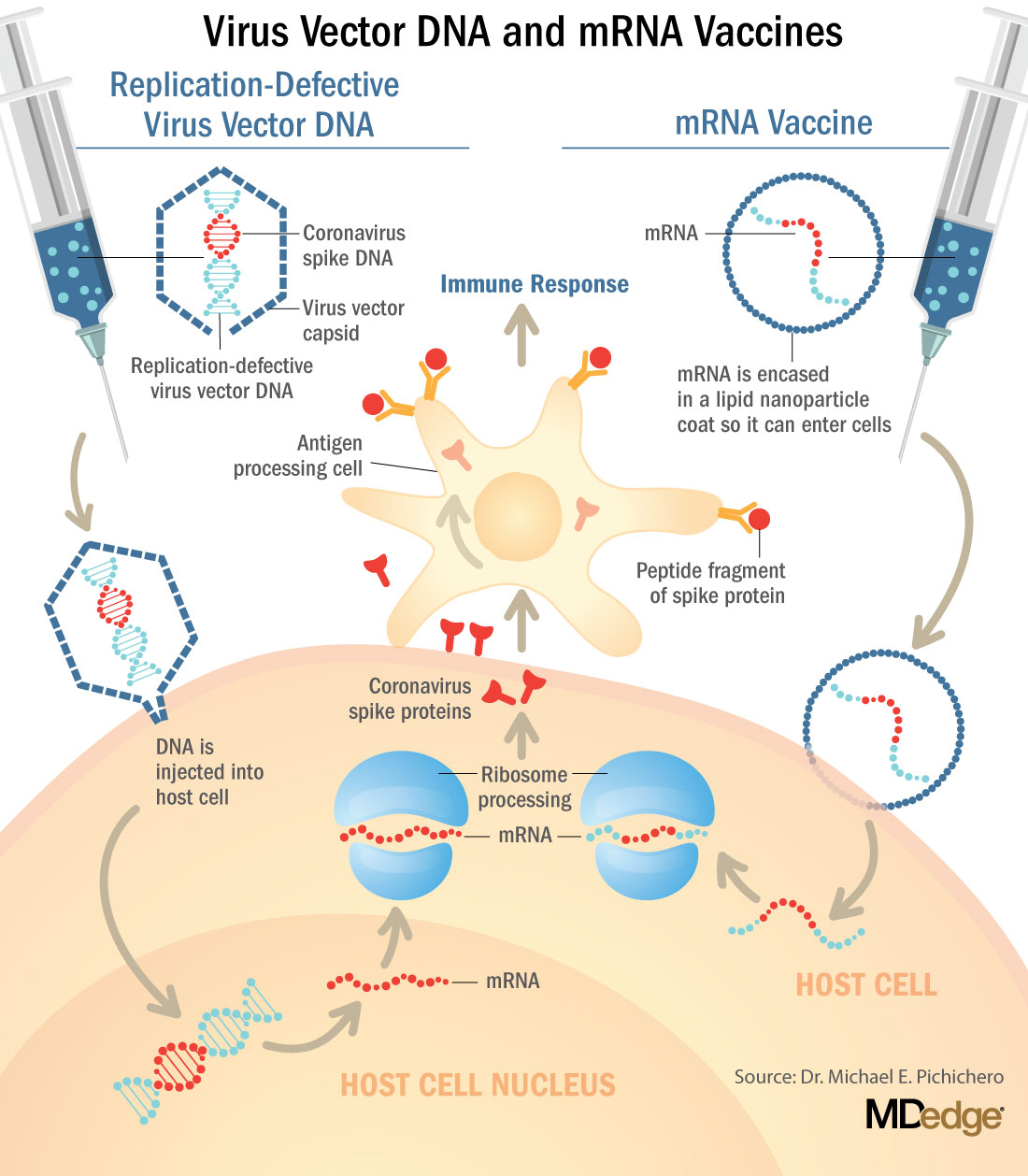

The vaccine candidates are using both conventional and novel mechanisms of action to elicit an immune response in patients. Conventional methods include attenuated inactivated (killed) virus and recombinant viral protein vaccines to develop immunity. Novel approaches include replication-deficient, adenovirus vector-based vaccines that contain the viral protein, and mRNA-based vaccines, such as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, that encode for a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

“The special vaccine concern for immunocompromised individuals is introduction of a live virus,” Dr. Stohl said. “Neither the Moderna nor Pfizer vaccines are live viruses, so there should be no special contraindication for such individuals.”

Live vaccine should be avoided in immunocompromised patients, and currently, live SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are only being developed in India and Turkey.

It is not unusual for vaccine trials to begin with cohorts that exclude participants with various health conditions, including those who are immunocompromised. These groups are generally then evaluated in phase 4 trials, or postmarketing surveillance. While the precise number of immunosuppressed adults in the United States is not known, the numbers are believed to be rising because of increased life expectancy among immunosuppressed adults as a result of advances in treatment and new and wider indications for therapies that can affect the immune system.

According to data from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 2.7% of U.S. adults are immunosuppressed. This population covers a broad array of health conditions and medical specialties; people living with inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, such as inflammatory rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, lupus); inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis); psoriasis; multiple sclerosis; organ transplant recipients; patients undergoing chemotherapy; and life-long immunosuppression attributable to HIV infection.

As the vaccines begin to roll out and become available, how should clinicians advise their patients, in the absence of any clinical trial data?

Risk vs. benefit

Gilaad Kaplan, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Calgary (Alta.), noted that the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) community has dealt with tremendous anxiety during the pandemic because many are immunocompromised because of the medications they use to treat their disease.

“For example, many patients with IBD are on biologics like anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapies, which are also used in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,” he said. “Understandably, individuals with IBD on immunosuppressive medications are concerned about the risk of severe complications due to COVID-19.”

The entire IBD community, along with the world, celebrated the announcement that multiple vaccines are protective against SARS-CoV-2, he noted. “Vaccines offer the potential to reduce the spread of COVID-19, allowing society to revert back to normalcy,” Dr. Kaplan said. “Moreover, for vulnerable populations, including those who are immunocompromised, vaccines offer the potential to directly protect them from the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.”

That said, even though the news of vaccines are extremely promising, some cautions must be raised regarding their use in immunocompromised populations, such as persons with IBD. “The current trials, to my knowledge, did not include immunocompromised individuals and thus, we can only extrapolate from what we know from other trials of different vaccines,” he explained. “We know from prior vaccines studies that the immune response following vaccination is less robust in those who are immunocompromised as compared to a healthy control population.”

Dr. Kaplan also pointed to recent reports of allergic reactions that have been reported in healthy individuals. “We don’t know whether side effects, like allergic reactions, may be different in unstudied populations,” he said. “Thus, the medical and scientific community should prioritize clinical studies of safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised populations.”

So, what does this mean for an individual with an immune-mediated inflammatory disease like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis who is immunocompromised? Dr. Kaplan explained that it is a balance between the potential harm of being infected with COVID-19 and the uncertainty of receiving a vaccine in an understudied population. For those who are highly susceptible to dying from COVID-19, such as an older adult with IBD, or someone who faces high exposure, such as a health care worker, the potential protection of the vaccine greatly outweighs the uncertainty.

“However, for individuals who are at otherwise lower risk – for example, young and able to work from home – then waiting a few extra months for postmarketing surveillance studies in immunocompromised populations may be a reasonable approach, as long as these individuals are taking great care to avoid infection,” he said.

No waiting needed

Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, feels that the newly approved vaccine should be safe for most of his patients.

“Patients with psoriatic disease should get the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible based on eligibility as determined by the CDC and local public health officials,” he said. “It is not a live vaccine, and therefore patients on biologics or other immune-modulating or immune-suppressing treatment can receive it.”

However, the impact of psoriasis treatment on immune response to the mRNA-based vaccines is not known. Dr. Gelfand noted that, extrapolating from the vaccine literature, there is some evidence that methotrexate reduces response to the influenza vaccine. “However, the clinical significance of this finding is not clear,” he said. “Since the mRNA vaccine needs to be taken twice, a few weeks apart, I do not recommend interrupting or delaying treatment for psoriatic disease while undergoing vaccination for COVID-19.”

Given the reports of allergic reactions, he added that it is advisable for patients with a history of life-threatening allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis or who have been advised to carry an epinephrine autoinjector, to talk with their health care provider to determine if COVID-19 vaccination is medically appropriate.

The National Psoriasis Foundation has issued guidance on COVID-19, explained Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and social sciences & health policy at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who is also a member of the committee that is working on those guidelines and keeping them up to date. “We are in the process of updating the guidelines with information on COVID vaccines,” he said.

He agreed that there are no contraindications for psoriasis patients to receive the vaccine, regardless of whether they are on immunosuppressive treatment, even though definitive data are lacking. “Fortunately, there’s a lot of good data coming out of Italy that patients with psoriasis on biologics do not appear to be at increased risk of getting COVID or of having worse outcomes from COVID,” he said.

Patients are going to ask about the vaccines, and when counseling them, clinicians should discuss the available data, the residual uncertainty, and patients’ concerns should be considered, Dr. Feldman explained. “There may be some concern that steroids and cyclosporine would reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, but there is no concern that any of the drugs would cause increased risk from nonlive vaccines.”

He added that there is evidence that “patients on biologics who receive nonlive vaccines do develop antibody responses and are immunized.”

Boosting efficacy

Even prior to making their announcement, the American College of Rheumatology had said that they would endorse the vaccine for all patients, explained rheumatologist Brett Smith, DO, from Blount Memorial Physicians Group and East Tennessee Children’s Hospital, Alcoa. “The vaccine is safe for all patients, but the problem may be that it’s not as effective,” he said. “But we don’t know that because it hasn’t been tested.”

With other vaccines, biologic medicines are held for 2 weeks before and afterwards, to get the best response. “But some patients don’t want to stop the medication,” Dr. Smith said. “They are afraid that their symptoms will return.”

As for counseling patients as to whether they should receive this vaccine, he explained that he typically doesn’t try to sway patients one way or another until they are really high risk. “When I counsel, it really depends on the individual situation. And for this vaccine, we have to be open to the fact that many people have already made up their mind.”

There are a lot of questions regarding the vaccine. One is the short time frame of development. “Vaccines typically take 6-10 years to come on the market, and this one is now available after a 3-month study,” Dr. Smith said. “Some have already decided that it’s too new for them.”

The process is also new, and patients need to understand that it doesn’t contain an active virus and “you can’t catch coronavirus from it.”

Dr. Smith also explained that, because the vaccine may be less effective in a person using biologic therapies, there is currently no information available on repeat vaccination. “These are all unanswered questions,” he said. “If the antibodies wane in a short time, can we be revaccinated and in what time frame? We just don’t know that yet.”

Marcelo Bonomi, MD, a medical oncologist from The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, explained that one way to ensure a more optimal response to the vaccine would be to wait until the patient has finished chemotherapy.* “The vaccine can be offered at that time, and in the meantime, they can take other steps to avoid infection,” he said. “If they are very immunosuppressed, it isn’t worth trying to give the vaccine.”

Cancer patients should be encouraged to stay as healthy as possible, and to wear masks and social distance. “It’s a comprehensive approach. Eat healthy, avoid alcohol and tobacco, and exercise. [These things] will help boost the immune system,” Dr. Bonomi said. “Family members should be encouraged to get vaccinated, which will help them avoid infection and exposing the patient.”

Jim Boonyaratanakornkit, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist who cares for cancer patients at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, agreed. “Giving a vaccine right after a transplant is a futile endeavor,” he said. “We need to wait 6 months to have an immune response.”

He pointed out there may be a continuing higher number of cases, with high levels peaking in Washington in February and March. “Close friends and family should be vaccinated if possible,” he said, “which will help interrupt transmission.”

The vaccines are using new platforms that are totally different, and there is no clear data as to how long the antibodies will persist. “We know that they last for at least 4 months,” said Dr. Boonyaratanakornkit. “We don’t know what level of antibody will protect them from COVID-19 infection. Current studies are being conducted, but we don’t have that information for anyone yet.”

*Correction, 1/7/21: An earlier version of this article misattributed quotes from Dr. Marcelo Bonomi.

Coronavirus vaccines have become a reality, as they are now being approved and authorized for use in a growing number of countries including the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has just issued emergency authorization for the use of the COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech. Close behind is the vaccine developed by Moderna, which has also applied to the FDA for emergency authorization.

The efficacy of a two-dose administration of the vaccine has been pegged at 95.0%, and the FDA has said that the 95% credible interval for the vaccine efficacy was 90.3%-97.6%. But as with many initial clinical trials, whether for drugs or vaccines, not all populations were represented in the trial cohort, including individuals who are immunocompromised. At the current time, it is largely unknown how safe or effective the vaccine may be in this large population, many of whom are at high risk for serious COVID-19 complications.

At a special session held during the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, said that individuals with compromised immune systems, whether because of chemotherapy or a bone marrow transplant, should plan to be vaccinated when the opportunity arises.

In response to a question from ASH President Stephanie J. Lee, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Dr. Fauci emphasized that, despite being excluded from clinical trials, this population should get vaccinated. “I think we should recommend that they get vaccinated,” he said. “I mean, it is clear that, if you are on immunosuppressive agents, history tells us that you’re not going to have as robust a response as if you had an intact immune system that was not being compromised. But some degree of immunity is better than no degree of immunity.”

That does seem to be the consensus among experts who spoke in interviews: that as long as these are not live attenuated vaccines, they hold no specific risk to an immunocompromised patient, other than any factors specific to the individual that could be a contraindication.

“Patients, family members, friends, and work contacts should be encouraged to receive the vaccine,” said William Stohl, MD, PhD, chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Clinicians should advise patients to obtain the vaccine sooner rather than later.”

Kevin C. Wang, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, agreed. “I am 100% with Dr. Fauci. Everyone should get the vaccine, even if it may not be as effective,” he said. “I would treat it exactly like the flu vaccines that we recommend folks get every year.”

Dr. Wang noted that he couldn’t think of any contraindications unless the immunosuppressed patients have a history of severe allergic reactions to prior vaccinations. “But I would even say patients with history of cancer, upon recommendation of their oncologists, are likely to be suitable candidates for the vaccine,” he added. “I would say clinicians should approach counseling the same way they counsel patients for the flu vaccine, and as far as I know, there are no concerns for systemic drugs commonly used in dermatology patients.”

However, guidance has not yet been issued from either the FDA or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regarding the use of the vaccine in immunocompromised individuals. Given the lack of data, the FDA has said that “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis,” and that individuals should consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has said that clinicians need more guidance on whether to use the vaccine in pregnant or breastfeeding women, the immunocompromised, or those who have a history of allergies. The CDC itself has not yet released its formal guidance on vaccine use.

COVID-19 vaccines

Vaccines typically require years of research and testing before reaching the clinic, but this year researchers embarked on a global effort to develop safe and effective coronavirus vaccines in record time. Both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines have only a few months of phase 3 clinical trial data, so much remains unknown about them, including their duration of effect and any long-term safety signals. In addition to excluding immunocompromised individuals, the clinical trials did not include children or pregnant women, so data are lacking for several population subgroups.

But these will not be the only vaccines available, as the pipeline is already becoming crowded. U.S. clinical trial data from a vaccine jointly being developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca, could potentially be ready, along with a request for FDA emergency use authorization, by late January 2021.

In addition, China and Russia have released vaccines, and there are currently 61 vaccines being investigated in clinical trials and at least 85 preclinical products under active investigation.

The vaccine candidates are using both conventional and novel mechanisms of action to elicit an immune response in patients. Conventional methods include attenuated inactivated (killed) virus and recombinant viral protein vaccines to develop immunity. Novel approaches include replication-deficient, adenovirus vector-based vaccines that contain the viral protein, and mRNA-based vaccines, such as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, that encode for a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

“The special vaccine concern for immunocompromised individuals is introduction of a live virus,” Dr. Stohl said. “Neither the Moderna nor Pfizer vaccines are live viruses, so there should be no special contraindication for such individuals.”

Live vaccine should be avoided in immunocompromised patients, and currently, live SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are only being developed in India and Turkey.

It is not unusual for vaccine trials to begin with cohorts that exclude participants with various health conditions, including those who are immunocompromised. These groups are generally then evaluated in phase 4 trials, or postmarketing surveillance. While the precise number of immunosuppressed adults in the United States is not known, the numbers are believed to be rising because of increased life expectancy among immunosuppressed adults as a result of advances in treatment and new and wider indications for therapies that can affect the immune system.

According to data from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 2.7% of U.S. adults are immunosuppressed. This population covers a broad array of health conditions and medical specialties; people living with inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, such as inflammatory rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, lupus); inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis); psoriasis; multiple sclerosis; organ transplant recipients; patients undergoing chemotherapy; and life-long immunosuppression attributable to HIV infection.

As the vaccines begin to roll out and become available, how should clinicians advise their patients, in the absence of any clinical trial data?

Risk vs. benefit

Gilaad Kaplan, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of Calgary (Alta.), noted that the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) community has dealt with tremendous anxiety during the pandemic because many are immunocompromised because of the medications they use to treat their disease.

“For example, many patients with IBD are on biologics like anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapies, which are also used in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,” he said. “Understandably, individuals with IBD on immunosuppressive medications are concerned about the risk of severe complications due to COVID-19.”

The entire IBD community, along with the world, celebrated the announcement that multiple vaccines are protective against SARS-CoV-2, he noted. “Vaccines offer the potential to reduce the spread of COVID-19, allowing society to revert back to normalcy,” Dr. Kaplan said. “Moreover, for vulnerable populations, including those who are immunocompromised, vaccines offer the potential to directly protect them from the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.”

That said, even though the news of vaccines are extremely promising, some cautions must be raised regarding their use in immunocompromised populations, such as persons with IBD. “The current trials, to my knowledge, did not include immunocompromised individuals and thus, we can only extrapolate from what we know from other trials of different vaccines,” he explained. “We know from prior vaccines studies that the immune response following vaccination is less robust in those who are immunocompromised as compared to a healthy control population.”

Dr. Kaplan also pointed to recent reports of allergic reactions that have been reported in healthy individuals. “We don’t know whether side effects, like allergic reactions, may be different in unstudied populations,” he said. “Thus, the medical and scientific community should prioritize clinical studies of safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised populations.”

So, what does this mean for an individual with an immune-mediated inflammatory disease like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis who is immunocompromised? Dr. Kaplan explained that it is a balance between the potential harm of being infected with COVID-19 and the uncertainty of receiving a vaccine in an understudied population. For those who are highly susceptible to dying from COVID-19, such as an older adult with IBD, or someone who faces high exposure, such as a health care worker, the potential protection of the vaccine greatly outweighs the uncertainty.

“However, for individuals who are at otherwise lower risk – for example, young and able to work from home – then waiting a few extra months for postmarketing surveillance studies in immunocompromised populations may be a reasonable approach, as long as these individuals are taking great care to avoid infection,” he said.

No waiting needed

Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, feels that the newly approved vaccine should be safe for most of his patients.

“Patients with psoriatic disease should get the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible based on eligibility as determined by the CDC and local public health officials,” he said. “It is not a live vaccine, and therefore patients on biologics or other immune-modulating or immune-suppressing treatment can receive it.”

However, the impact of psoriasis treatment on immune response to the mRNA-based vaccines is not known. Dr. Gelfand noted that, extrapolating from the vaccine literature, there is some evidence that methotrexate reduces response to the influenza vaccine. “However, the clinical significance of this finding is not clear,” he said. “Since the mRNA vaccine needs to be taken twice, a few weeks apart, I do not recommend interrupting or delaying treatment for psoriatic disease while undergoing vaccination for COVID-19.”

Given the reports of allergic reactions, he added that it is advisable for patients with a history of life-threatening allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis or who have been advised to carry an epinephrine autoinjector, to talk with their health care provider to determine if COVID-19 vaccination is medically appropriate.

The National Psoriasis Foundation has issued guidance on COVID-19, explained Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and social sciences & health policy at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., who is also a member of the committee that is working on those guidelines and keeping them up to date. “We are in the process of updating the guidelines with information on COVID vaccines,” he said.

He agreed that there are no contraindications for psoriasis patients to receive the vaccine, regardless of whether they are on immunosuppressive treatment, even though definitive data are lacking. “Fortunately, there’s a lot of good data coming out of Italy that patients with psoriasis on biologics do not appear to be at increased risk of getting COVID or of having worse outcomes from COVID,” he said.

Patients are going to ask about the vaccines, and when counseling them, clinicians should discuss the available data, the residual uncertainty, and patients’ concerns should be considered, Dr. Feldman explained. “There may be some concern that steroids and cyclosporine would reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, but there is no concern that any of the drugs would cause increased risk from nonlive vaccines.”

He added that there is evidence that “patients on biologics who receive nonlive vaccines do develop antibody responses and are immunized.”

Boosting efficacy

Even prior to making their announcement, the American College of Rheumatology had said that they would endorse the vaccine for all patients, explained rheumatologist Brett Smith, DO, from Blount Memorial Physicians Group and East Tennessee Children’s Hospital, Alcoa. “The vaccine is safe for all patients, but the problem may be that it’s not as effective,” he said. “But we don’t know that because it hasn’t been tested.”

With other vaccines, biologic medicines are held for 2 weeks before and afterwards, to get the best response. “But some patients don’t want to stop the medication,” Dr. Smith said. “They are afraid that their symptoms will return.”

As for counseling patients as to whether they should receive this vaccine, he explained that he typically doesn’t try to sway patients one way or another until they are really high risk. “When I counsel, it really depends on the individual situation. And for this vaccine, we have to be open to the fact that many people have already made up their mind.”

There are a lot of questions regarding the vaccine. One is the short time frame of development. “Vaccines typically take 6-10 years to come on the market, and this one is now available after a 3-month study,” Dr. Smith said. “Some have already decided that it’s too new for them.”

The process is also new, and patients need to understand that it doesn’t contain an active virus and “you can’t catch coronavirus from it.”

Dr. Smith also explained that, because the vaccine may be less effective in a person using biologic therapies, there is currently no information available on repeat vaccination. “These are all unanswered questions,” he said. “If the antibodies wane in a short time, can we be revaccinated and in what time frame? We just don’t know that yet.”

Marcelo Bonomi, MD, a medical oncologist from The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, explained that one way to ensure a more optimal response to the vaccine would be to wait until the patient has finished chemotherapy.* “The vaccine can be offered at that time, and in the meantime, they can take other steps to avoid infection,” he said. “If they are very immunosuppressed, it isn’t worth trying to give the vaccine.”

Cancer patients should be encouraged to stay as healthy as possible, and to wear masks and social distance. “It’s a comprehensive approach. Eat healthy, avoid alcohol and tobacco, and exercise. [These things] will help boost the immune system,” Dr. Bonomi said. “Family members should be encouraged to get vaccinated, which will help them avoid infection and exposing the patient.”

Jim Boonyaratanakornkit, MD, PhD, an infectious disease specialist who cares for cancer patients at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, agreed. “Giving a vaccine right after a transplant is a futile endeavor,” he said. “We need to wait 6 months to have an immune response.”

He pointed out there may be a continuing higher number of cases, with high levels peaking in Washington in February and March. “Close friends and family should be vaccinated if possible,” he said, “which will help interrupt transmission.”

The vaccines are using new platforms that are totally different, and there is no clear data as to how long the antibodies will persist. “We know that they last for at least 4 months,” said Dr. Boonyaratanakornkit. “We don’t know what level of antibody will protect them from COVID-19 infection. Current studies are being conducted, but we don’t have that information for anyone yet.”

*Correction, 1/7/21: An earlier version of this article misattributed quotes from Dr. Marcelo Bonomi.

Coronavirus vaccines have become a reality, as they are now being approved and authorized for use in a growing number of countries including the United States. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has just issued emergency authorization for the use of the COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech. Close behind is the vaccine developed by Moderna, which has also applied to the FDA for emergency authorization.

The efficacy of a two-dose administration of the vaccine has been pegged at 95.0%, and the FDA has said that the 95% credible interval for the vaccine efficacy was 90.3%-97.6%. But as with many initial clinical trials, whether for drugs or vaccines, not all populations were represented in the trial cohort, including individuals who are immunocompromised. At the current time, it is largely unknown how safe or effective the vaccine may be in this large population, many of whom are at high risk for serious COVID-19 complications.

At a special session held during the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Anthony Fauci, MD, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, said that individuals with compromised immune systems, whether because of chemotherapy or a bone marrow transplant, should plan to be vaccinated when the opportunity arises.

In response to a question from ASH President Stephanie J. Lee, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Dr. Fauci emphasized that, despite being excluded from clinical trials, this population should get vaccinated. “I think we should recommend that they get vaccinated,” he said. “I mean, it is clear that, if you are on immunosuppressive agents, history tells us that you’re not going to have as robust a response as if you had an intact immune system that was not being compromised. But some degree of immunity is better than no degree of immunity.”

That does seem to be the consensus among experts who spoke in interviews: that as long as these are not live attenuated vaccines, they hold no specific risk to an immunocompromised patient, other than any factors specific to the individual that could be a contraindication.

“Patients, family members, friends, and work contacts should be encouraged to receive the vaccine,” said William Stohl, MD, PhD, chief of the division of rheumatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Clinicians should advise patients to obtain the vaccine sooner rather than later.”

Kevin C. Wang, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, agreed. “I am 100% with Dr. Fauci. Everyone should get the vaccine, even if it may not be as effective,” he said. “I would treat it exactly like the flu vaccines that we recommend folks get every year.”

Dr. Wang noted that he couldn’t think of any contraindications unless the immunosuppressed patients have a history of severe allergic reactions to prior vaccinations. “But I would even say patients with history of cancer, upon recommendation of their oncologists, are likely to be suitable candidates for the vaccine,” he added. “I would say clinicians should approach counseling the same way they counsel patients for the flu vaccine, and as far as I know, there are no concerns for systemic drugs commonly used in dermatology patients.”

However, guidance has not yet been issued from either the FDA or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention regarding the use of the vaccine in immunocompromised individuals. Given the lack of data, the FDA has said that “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis,” and that individuals should consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has said that clinicians need more guidance on whether to use the vaccine in pregnant or breastfeeding women, the immunocompromised, or those who have a history of allergies. The CDC itself has not yet released its formal guidance on vaccine use.

COVID-19 vaccines

Vaccines typically require years of research and testing before reaching the clinic, but this year researchers embarked on a global effort to develop safe and effective coronavirus vaccines in record time. Both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines have only a few months of phase 3 clinical trial data, so much remains unknown about them, including their duration of effect and any long-term safety signals. In addition to excluding immunocompromised individuals, the clinical trials did not include children or pregnant women, so data are lacking for several population subgroups.