User login

Myth busting: SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

MYTH: I shouldn’t get the vaccine because of potential long-term side effects

We know that 68 million people in the United States and 244 million people worldwide have already received messenger RNA (mRNA) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna). So for the short-term side effects we already know more than we would know about most vaccines.

What about the long-term side effects? There are myths that these vaccines somehow could cause autoimmunity. This came from three publications where the possibility of mRNA vaccines to produce autoimmunity was brought up as a discussion point.1-3 There was no evidence given in these publications, it was raised only as a hypothetical possibility.

There’s no evidence that mRNA or replication-defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) produce autoimmunity. Moreover, the mRNA and replication-defective DNA, once it’s inside of the muscle cell, is gone within a few days. What’s left after ribosome processing is the spike (S) protein as an immunogen. We’ve been vaccinating with proteins for 50 years and we haven’t seen autoimmunity.

MYTH: The vaccines aren’t safe because they were developed so quickly

These vaccines were developed at “warp speed” – that doesn’t mean they were developed without all the same safety safeguards that the Food and Drug Administration requires. The reason it happened so fast is because the seriousness of the pandemic allowed us, as a community, to enroll the patients into the studies fast. In a matter of months, we had all the studies filled. In a normal circumstance, that might take 2 or 3 years. And all of the regulatory agencies – the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – were ready to take the information and put a panel of specialists together and immediately review the data. No safety steps were missed. The same process that’s always required of phase 1, of phase 2, and then at phase 3 were accomplished.

The novelty of these vaccines was that they could be made so quickly. Messenger RNA vaccines can be made in a matter of days and then manufactured in a matter of 2 months. The DNA vaccines has a similar timeline trajectory.

MYTH: There’s no point in getting the vaccines because we still have to wear masks

Right now, out of an abundance of caution, until it’s proven that we don’t have to wear masks, it’s being recommended that we do so for the safety of others. Early data suggest that this will be temporary. In time, I suspect it will be shown that, after we receive the vaccine, it will be shown that we are not contagious to others and we’ll be able to get rid of our masks.

MYTH: I already had COVID-19 so I don’t need the vaccine

Some people have already caught the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes this infection and so they feel that they’re immune and they don’t need to get the vaccine. Time will tell if that’s the case. Right now, we don’t know for sure. Early data suggest that a single dose of vaccine in persons who have had the infection may be sufficient. Over time, what happens in the vaccine field is we measure the immunity from the vaccine, and from people who’ve gotten the infection, and we find that there’s a measurement in the blood that correlates with protection. Right now, we don’t know that correlate of protection level. So, out of an abundance of caution, it’s being recommended that, even if you had the disease, maybe you didn’t develop enough immunity, and it’s better to get the vaccine than to get the illness a second time.

MYTH: The vaccines can give me SARS-CoV-2 infection

The new vaccines for COVID-19, released under emergency use Authorization, are mRNA and DNA vaccines. They are a blueprint for the Spike (S) protein of the virus. In order to become a protein, the mRNA, once it’s inside the cell, is processed by ribosomes. The product of the ribosome processing is a protein that cannot possibly cause harm as a virus. It’s a little piece of mRNA inside of a lipid nanoparticle, which is just a casing to protect the mRNA from breaking down until it’s injected in the body. The replication defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) are packaged inside of virus cells (adenoviruses). The DNA vaccines involve a three-step process:

- 1. The adenovirus, containing replication-defective DNA that encodes mRNA for the Spike (S) protein, is taken up by the host cells where it must make its way to the nucleus of the muscle cell.

- 2. The DNA is injected into the host cell nucleus and in the nucleus the DNA is decoded to an mRNA.

- 3. The mRNA is released from the nucleus and transported to the cell cytoplasm where the ribosomes process the mRNA in an identical manner as mRNA vaccines.

MYTH: The COVID-19 vaccines can alter my DNA

The mRNA and replication-defective DNA vaccines never interact with your DNA. mRNA vaccines never enter the nucleus. Replication-defective DNA vaccines cannot replicate and do not interact with host DNA. The vaccines can’t change your DNA.

Here is a link to YouTube videos I made on this topic: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLve-0UW04UMRKHfFbXyEpLY8GCm2WyJHD.

Here is a photo of me receiving my first SARS-CoV-2 shot (Moderna) in January 2021. I received my second shot in February. I am a lot less anxious. I hope my vaccine card will be a ticket to travel in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

2. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

3. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

MYTH: I shouldn’t get the vaccine because of potential long-term side effects

We know that 68 million people in the United States and 244 million people worldwide have already received messenger RNA (mRNA) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna). So for the short-term side effects we already know more than we would know about most vaccines.

What about the long-term side effects? There are myths that these vaccines somehow could cause autoimmunity. This came from three publications where the possibility of mRNA vaccines to produce autoimmunity was brought up as a discussion point.1-3 There was no evidence given in these publications, it was raised only as a hypothetical possibility.

There’s no evidence that mRNA or replication-defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) produce autoimmunity. Moreover, the mRNA and replication-defective DNA, once it’s inside of the muscle cell, is gone within a few days. What’s left after ribosome processing is the spike (S) protein as an immunogen. We’ve been vaccinating with proteins for 50 years and we haven’t seen autoimmunity.

MYTH: The vaccines aren’t safe because they were developed so quickly

These vaccines were developed at “warp speed” – that doesn’t mean they were developed without all the same safety safeguards that the Food and Drug Administration requires. The reason it happened so fast is because the seriousness of the pandemic allowed us, as a community, to enroll the patients into the studies fast. In a matter of months, we had all the studies filled. In a normal circumstance, that might take 2 or 3 years. And all of the regulatory agencies – the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – were ready to take the information and put a panel of specialists together and immediately review the data. No safety steps were missed. The same process that’s always required of phase 1, of phase 2, and then at phase 3 were accomplished.

The novelty of these vaccines was that they could be made so quickly. Messenger RNA vaccines can be made in a matter of days and then manufactured in a matter of 2 months. The DNA vaccines has a similar timeline trajectory.

MYTH: There’s no point in getting the vaccines because we still have to wear masks

Right now, out of an abundance of caution, until it’s proven that we don’t have to wear masks, it’s being recommended that we do so for the safety of others. Early data suggest that this will be temporary. In time, I suspect it will be shown that, after we receive the vaccine, it will be shown that we are not contagious to others and we’ll be able to get rid of our masks.

MYTH: I already had COVID-19 so I don’t need the vaccine

Some people have already caught the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes this infection and so they feel that they’re immune and they don’t need to get the vaccine. Time will tell if that’s the case. Right now, we don’t know for sure. Early data suggest that a single dose of vaccine in persons who have had the infection may be sufficient. Over time, what happens in the vaccine field is we measure the immunity from the vaccine, and from people who’ve gotten the infection, and we find that there’s a measurement in the blood that correlates with protection. Right now, we don’t know that correlate of protection level. So, out of an abundance of caution, it’s being recommended that, even if you had the disease, maybe you didn’t develop enough immunity, and it’s better to get the vaccine than to get the illness a second time.

MYTH: The vaccines can give me SARS-CoV-2 infection

The new vaccines for COVID-19, released under emergency use Authorization, are mRNA and DNA vaccines. They are a blueprint for the Spike (S) protein of the virus. In order to become a protein, the mRNA, once it’s inside the cell, is processed by ribosomes. The product of the ribosome processing is a protein that cannot possibly cause harm as a virus. It’s a little piece of mRNA inside of a lipid nanoparticle, which is just a casing to protect the mRNA from breaking down until it’s injected in the body. The replication defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) are packaged inside of virus cells (adenoviruses). The DNA vaccines involve a three-step process:

- 1. The adenovirus, containing replication-defective DNA that encodes mRNA for the Spike (S) protein, is taken up by the host cells where it must make its way to the nucleus of the muscle cell.

- 2. The DNA is injected into the host cell nucleus and in the nucleus the DNA is decoded to an mRNA.

- 3. The mRNA is released from the nucleus and transported to the cell cytoplasm where the ribosomes process the mRNA in an identical manner as mRNA vaccines.

MYTH: The COVID-19 vaccines can alter my DNA

The mRNA and replication-defective DNA vaccines never interact with your DNA. mRNA vaccines never enter the nucleus. Replication-defective DNA vaccines cannot replicate and do not interact with host DNA. The vaccines can’t change your DNA.

Here is a link to YouTube videos I made on this topic: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLve-0UW04UMRKHfFbXyEpLY8GCm2WyJHD.

Here is a photo of me receiving my first SARS-CoV-2 shot (Moderna) in January 2021. I received my second shot in February. I am a lot less anxious. I hope my vaccine card will be a ticket to travel in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

2. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

3. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

MYTH: I shouldn’t get the vaccine because of potential long-term side effects

We know that 68 million people in the United States and 244 million people worldwide have already received messenger RNA (mRNA) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna). So for the short-term side effects we already know more than we would know about most vaccines.

What about the long-term side effects? There are myths that these vaccines somehow could cause autoimmunity. This came from three publications where the possibility of mRNA vaccines to produce autoimmunity was brought up as a discussion point.1-3 There was no evidence given in these publications, it was raised only as a hypothetical possibility.

There’s no evidence that mRNA or replication-defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) produce autoimmunity. Moreover, the mRNA and replication-defective DNA, once it’s inside of the muscle cell, is gone within a few days. What’s left after ribosome processing is the spike (S) protein as an immunogen. We’ve been vaccinating with proteins for 50 years and we haven’t seen autoimmunity.

MYTH: The vaccines aren’t safe because they were developed so quickly

These vaccines were developed at “warp speed” – that doesn’t mean they were developed without all the same safety safeguards that the Food and Drug Administration requires. The reason it happened so fast is because the seriousness of the pandemic allowed us, as a community, to enroll the patients into the studies fast. In a matter of months, we had all the studies filled. In a normal circumstance, that might take 2 or 3 years. And all of the regulatory agencies – the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – were ready to take the information and put a panel of specialists together and immediately review the data. No safety steps were missed. The same process that’s always required of phase 1, of phase 2, and then at phase 3 were accomplished.

The novelty of these vaccines was that they could be made so quickly. Messenger RNA vaccines can be made in a matter of days and then manufactured in a matter of 2 months. The DNA vaccines has a similar timeline trajectory.

MYTH: There’s no point in getting the vaccines because we still have to wear masks

Right now, out of an abundance of caution, until it’s proven that we don’t have to wear masks, it’s being recommended that we do so for the safety of others. Early data suggest that this will be temporary. In time, I suspect it will be shown that, after we receive the vaccine, it will be shown that we are not contagious to others and we’ll be able to get rid of our masks.

MYTH: I already had COVID-19 so I don’t need the vaccine

Some people have already caught the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes this infection and so they feel that they’re immune and they don’t need to get the vaccine. Time will tell if that’s the case. Right now, we don’t know for sure. Early data suggest that a single dose of vaccine in persons who have had the infection may be sufficient. Over time, what happens in the vaccine field is we measure the immunity from the vaccine, and from people who’ve gotten the infection, and we find that there’s a measurement in the blood that correlates with protection. Right now, we don’t know that correlate of protection level. So, out of an abundance of caution, it’s being recommended that, even if you had the disease, maybe you didn’t develop enough immunity, and it’s better to get the vaccine than to get the illness a second time.

MYTH: The vaccines can give me SARS-CoV-2 infection

The new vaccines for COVID-19, released under emergency use Authorization, are mRNA and DNA vaccines. They are a blueprint for the Spike (S) protein of the virus. In order to become a protein, the mRNA, once it’s inside the cell, is processed by ribosomes. The product of the ribosome processing is a protein that cannot possibly cause harm as a virus. It’s a little piece of mRNA inside of a lipid nanoparticle, which is just a casing to protect the mRNA from breaking down until it’s injected in the body. The replication defective DNA vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford and Johnson & Johnson) are packaged inside of virus cells (adenoviruses). The DNA vaccines involve a three-step process:

- 1. The adenovirus, containing replication-defective DNA that encodes mRNA for the Spike (S) protein, is taken up by the host cells where it must make its way to the nucleus of the muscle cell.

- 2. The DNA is injected into the host cell nucleus and in the nucleus the DNA is decoded to an mRNA.

- 3. The mRNA is released from the nucleus and transported to the cell cytoplasm where the ribosomes process the mRNA in an identical manner as mRNA vaccines.

MYTH: The COVID-19 vaccines can alter my DNA

The mRNA and replication-defective DNA vaccines never interact with your DNA. mRNA vaccines never enter the nucleus. Replication-defective DNA vaccines cannot replicate and do not interact with host DNA. The vaccines can’t change your DNA.

Here is a link to YouTube videos I made on this topic: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLve-0UW04UMRKHfFbXyEpLY8GCm2WyJHD.

Here is a photo of me receiving my first SARS-CoV-2 shot (Moderna) in January 2021. I received my second shot in February. I am a lot less anxious. I hope my vaccine card will be a ticket to travel in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

2. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

3. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

CDC data strengthen link between obesity and severe COVID

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Missed visits during pandemic cause ‘detrimental ripple effects’

according to a new report from the Urban Institute.

Among the adults who postponed or missed care, 32.6% said the gap worsened one or more health conditions or limited their ability to work or perform daily activities. The findings highlight “the detrimental ripple effects of delaying or forgoing care on overall health, functioning, and well-being,” researchers write.

The survey, conducted among 4,007 U.S. adults aged 18-64 in September 2020, found that adults with one or more chronic conditions were more likely than adults without chronic conditions to have delayed or missed care (40.7% vs. 26.4%). Adults with a mental health condition were particularly likely to have delayed or gone without care, write Dulce Gonzalez, MPP, a research associate in the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute, and colleagues.

Doctors are already seeing the consequences of the missed visits, says Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, president of the American College of Physicians.

Two of her patients with chronic conditions missed appointments last year. By the time they resumed care in 2021, their previsit lab tests showed significant kidney deterioration.

“Lo and behold, their kidneys were in failure. … One was in the hospital for 3 days and the other one was in for 5 days,” said Dr. Fincher, who practices general internal medicine in Georgia.

Dr. Fincher’s office has been proactive about calling patients with chronic diseases who missed follow-up visits or laboratory testing or who may have run out of medication, she said.

In her experience, delays mainly have been because of patients postponing visits. “We have stayed open the whole time now,” Dr. Fincher said. Her office offers telemedicine visits and in-person visits with safety precautions.

Still, some patients have decided to postpone care during the pandemic instead of asking their primary care doctor what they should do.

“We do know that chronic problems left without appropriate follow-up can create worse problems for them in terms of stroke, heart attack, and end organ damage,” Dr. Fincher said.

Lost lives

Future studies may help researchers understand the effects of delayed and missed care during the pandemic, said Russell S. Phillips, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Although it is still early, and more data on patient outcomes will need to be collected, I anticipate that the ... delays in diagnosis, in cancer screening, and in management of chronic illness will result in lost lives and will emphasize the important role that primary care plays in saving lives,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the first several months of the pandemic, there were fewer diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, and depression, Dr. Phillips said.

“In addition, and most importantly, the mortality rate for non-COVID conditions increased, suggesting that patients were not seeking care for symptoms of stroke or heart attack, which can be fatal if untreated,” he said. “We have also seen substantial decreases in cancer screening tests such as colonoscopy, and modeling studies suggest this will cost more lives based on delayed diagnoses of cancer.”

Vaccinating patients against COVID-19 may help primary care practices and patients get back on track, Dr. Phillips suggested.

In the meantime, some patients remain reluctant to come in. “Volumes are still lower than prepandemic, so it is challenging to overcome what is likely to be pent-up demand,” he told this news organization in an email. “Additionally, the continued burden of evaluating, testing, and monitoring patients with COVID or COVID-like symptoms makes it difficult to focus on chronic illness.”

Care most often skipped

The Urban Institute survey asked respondents about delays in prescription drugs, general doctor and specialist visits, going to a hospital, preventive health screenings or medical tests, treatment or follow-up care, dental care, mental health care or counseling, treatment or counseling for alcohol or drug use, and other types of medical care.

Dental care was the most common type of care that adults delayed or did not receive because of the pandemic (25.3%), followed by general doctor or specialist visits (20.6%) and preventive health screenings or medical tests (15.5%).

Black adults were more likely than White or Hispanic/Latinx adults to have delayed or forgone care (39.7% vs. 34.3% and 35.5%), the researchers found. Compared with adults with higher incomes, adults with lower incomes were more likely to have missed multiple types of care (26.6% vs. 20.3%).

The report by the Urban Institute researchers was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Phillips is an adviser to two telemedicine companies, Bicycle Health and Grow Health. Dr. Fincher has disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new report from the Urban Institute.

Among the adults who postponed or missed care, 32.6% said the gap worsened one or more health conditions or limited their ability to work or perform daily activities. The findings highlight “the detrimental ripple effects of delaying or forgoing care on overall health, functioning, and well-being,” researchers write.

The survey, conducted among 4,007 U.S. adults aged 18-64 in September 2020, found that adults with one or more chronic conditions were more likely than adults without chronic conditions to have delayed or missed care (40.7% vs. 26.4%). Adults with a mental health condition were particularly likely to have delayed or gone without care, write Dulce Gonzalez, MPP, a research associate in the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute, and colleagues.

Doctors are already seeing the consequences of the missed visits, says Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, president of the American College of Physicians.

Two of her patients with chronic conditions missed appointments last year. By the time they resumed care in 2021, their previsit lab tests showed significant kidney deterioration.

“Lo and behold, their kidneys were in failure. … One was in the hospital for 3 days and the other one was in for 5 days,” said Dr. Fincher, who practices general internal medicine in Georgia.

Dr. Fincher’s office has been proactive about calling patients with chronic diseases who missed follow-up visits or laboratory testing or who may have run out of medication, she said.

In her experience, delays mainly have been because of patients postponing visits. “We have stayed open the whole time now,” Dr. Fincher said. Her office offers telemedicine visits and in-person visits with safety precautions.

Still, some patients have decided to postpone care during the pandemic instead of asking their primary care doctor what they should do.

“We do know that chronic problems left without appropriate follow-up can create worse problems for them in terms of stroke, heart attack, and end organ damage,” Dr. Fincher said.

Lost lives

Future studies may help researchers understand the effects of delayed and missed care during the pandemic, said Russell S. Phillips, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Although it is still early, and more data on patient outcomes will need to be collected, I anticipate that the ... delays in diagnosis, in cancer screening, and in management of chronic illness will result in lost lives and will emphasize the important role that primary care plays in saving lives,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the first several months of the pandemic, there were fewer diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, and depression, Dr. Phillips said.

“In addition, and most importantly, the mortality rate for non-COVID conditions increased, suggesting that patients were not seeking care for symptoms of stroke or heart attack, which can be fatal if untreated,” he said. “We have also seen substantial decreases in cancer screening tests such as colonoscopy, and modeling studies suggest this will cost more lives based on delayed diagnoses of cancer.”

Vaccinating patients against COVID-19 may help primary care practices and patients get back on track, Dr. Phillips suggested.

In the meantime, some patients remain reluctant to come in. “Volumes are still lower than prepandemic, so it is challenging to overcome what is likely to be pent-up demand,” he told this news organization in an email. “Additionally, the continued burden of evaluating, testing, and monitoring patients with COVID or COVID-like symptoms makes it difficult to focus on chronic illness.”

Care most often skipped

The Urban Institute survey asked respondents about delays in prescription drugs, general doctor and specialist visits, going to a hospital, preventive health screenings or medical tests, treatment or follow-up care, dental care, mental health care or counseling, treatment or counseling for alcohol or drug use, and other types of medical care.

Dental care was the most common type of care that adults delayed or did not receive because of the pandemic (25.3%), followed by general doctor or specialist visits (20.6%) and preventive health screenings or medical tests (15.5%).

Black adults were more likely than White or Hispanic/Latinx adults to have delayed or forgone care (39.7% vs. 34.3% and 35.5%), the researchers found. Compared with adults with higher incomes, adults with lower incomes were more likely to have missed multiple types of care (26.6% vs. 20.3%).

The report by the Urban Institute researchers was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Phillips is an adviser to two telemedicine companies, Bicycle Health and Grow Health. Dr. Fincher has disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new report from the Urban Institute.

Among the adults who postponed or missed care, 32.6% said the gap worsened one or more health conditions or limited their ability to work or perform daily activities. The findings highlight “the detrimental ripple effects of delaying or forgoing care on overall health, functioning, and well-being,” researchers write.

The survey, conducted among 4,007 U.S. adults aged 18-64 in September 2020, found that adults with one or more chronic conditions were more likely than adults without chronic conditions to have delayed or missed care (40.7% vs. 26.4%). Adults with a mental health condition were particularly likely to have delayed or gone without care, write Dulce Gonzalez, MPP, a research associate in the Health Policy Center at the Urban Institute, and colleagues.

Doctors are already seeing the consequences of the missed visits, says Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, president of the American College of Physicians.

Two of her patients with chronic conditions missed appointments last year. By the time they resumed care in 2021, their previsit lab tests showed significant kidney deterioration.

“Lo and behold, their kidneys were in failure. … One was in the hospital for 3 days and the other one was in for 5 days,” said Dr. Fincher, who practices general internal medicine in Georgia.

Dr. Fincher’s office has been proactive about calling patients with chronic diseases who missed follow-up visits or laboratory testing or who may have run out of medication, she said.

In her experience, delays mainly have been because of patients postponing visits. “We have stayed open the whole time now,” Dr. Fincher said. Her office offers telemedicine visits and in-person visits with safety precautions.

Still, some patients have decided to postpone care during the pandemic instead of asking their primary care doctor what they should do.

“We do know that chronic problems left without appropriate follow-up can create worse problems for them in terms of stroke, heart attack, and end organ damage,” Dr. Fincher said.

Lost lives

Future studies may help researchers understand the effects of delayed and missed care during the pandemic, said Russell S. Phillips, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Although it is still early, and more data on patient outcomes will need to be collected, I anticipate that the ... delays in diagnosis, in cancer screening, and in management of chronic illness will result in lost lives and will emphasize the important role that primary care plays in saving lives,” Dr. Phillips said.

During the first several months of the pandemic, there were fewer diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, and depression, Dr. Phillips said.

“In addition, and most importantly, the mortality rate for non-COVID conditions increased, suggesting that patients were not seeking care for symptoms of stroke or heart attack, which can be fatal if untreated,” he said. “We have also seen substantial decreases in cancer screening tests such as colonoscopy, and modeling studies suggest this will cost more lives based on delayed diagnoses of cancer.”

Vaccinating patients against COVID-19 may help primary care practices and patients get back on track, Dr. Phillips suggested.

In the meantime, some patients remain reluctant to come in. “Volumes are still lower than prepandemic, so it is challenging to overcome what is likely to be pent-up demand,” he told this news organization in an email. “Additionally, the continued burden of evaluating, testing, and monitoring patients with COVID or COVID-like symptoms makes it difficult to focus on chronic illness.”

Care most often skipped

The Urban Institute survey asked respondents about delays in prescription drugs, general doctor and specialist visits, going to a hospital, preventive health screenings or medical tests, treatment or follow-up care, dental care, mental health care or counseling, treatment or counseling for alcohol or drug use, and other types of medical care.

Dental care was the most common type of care that adults delayed or did not receive because of the pandemic (25.3%), followed by general doctor or specialist visits (20.6%) and preventive health screenings or medical tests (15.5%).

Black adults were more likely than White or Hispanic/Latinx adults to have delayed or forgone care (39.7% vs. 34.3% and 35.5%), the researchers found. Compared with adults with higher incomes, adults with lower incomes were more likely to have missed multiple types of care (26.6% vs. 20.3%).

The report by the Urban Institute researchers was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Phillips is an adviser to two telemedicine companies, Bicycle Health and Grow Health. Dr. Fincher has disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Postoperative Neurologic Deficits in a Veteran With Recent COVID-19

Anesthesia providers should be aware of COVID-19 sensitive stroke code practices and maintain heightened vigilance for the need to implement perioperative stroke mitigation strategies.

The risk of perioperative stroke in noncardiac, nonneurologic, nonvascular surgery ranges from 0.1 to 1.9% and is associated with increased mortality.1,2 Stroke mechanisms include both ischemia (large and small vessel occlusion, cardioembolism, anemic-tissue hypoxia, cerebral hypoperfusion) and hemorrhage.1 Risk factors for perioperative stroke include prior cerebral vascular accident (CVA), hypertension, aged > 62 years, acute renal insufficiency, dialysis, and recent myocardial infarction (MI).2

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020.3 COVID-19 has certainly affected the veteran population; between February and May 2020, more than 60,000 veterans were tested for COVID-19 with a positive rate of about 9%.4 While primarily affecting the respiratory system, there are increasing reports of COVID-19 neurologic manifestations: headache, hypogeusia, hyposomia, seizure, encephalitis, and acute stroke.5 In an early case series from Wuhan, China, 36% of 214 patients with COVID-19 reported neurologic complications, and acute CVAs were more common in patients with severe (compared to milder) viral disease presentations (5.7% vs 0.8%).6 Large vessel stroke was a presenting feature in another report of 5 patients aged < 50 years.7

The mechanism of ischemic stroke in the setting of COVID-19 is unclear.8 Indeed, stroke and COVID-19 share similar risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus [DM], older age), and immobile critically ill patients may already be prone to developing stroke.5,9 However, COVID-19 is associated with arterial and venous thromboembolism, elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, and antiphospholipid antibody production. This prothrombotic state may be linked to cytokine-induced endothelial damage, mononuclear cell activation, tissue factor expression, and ultimately thrombin propagation and platelet activation.8

The rates of perioperative stroke may change as more patients with COVID-19 present for surgery, and the anesthesiology care team must prioritize mitigation efforts in high-risk patients, including veterans. Reducing the elevated stroke burden within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a public health priority.10 We present the case of a veteran with prior CVA and recent positive COVID-19 testing who experienced transient weakness and dysarthria following plastic surgery. The patient discussed provided written Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act consent for publication of this report.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old male veteran presented to the Minneapolis VA Medical Center in Minnesota with chronic left foot ulceration necessitating debridement and flap coverage. His medical history was significant for hypertension, type 2 DM, anemia of chronic disease, and coronary artery disease (left ventricular ejection fraction, 50%). Additionally, he had prior ischemic strokes in the oculomotor nucleus (in 2004 with internuclear ophthalmoplegia) and left ventral medulla (in 2019 with right hemiparesis). During his 2019 poststroke rehabilitation, he was diagnosed with mild neurocognitive deficit not attributable to his strokes. The patient’s medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, atorvastatin, clopidogrel (lifelong for secondary stroke prevention), metformin, and glipizide. The debridement procedure was initially delayed 3 weeks due to positive routine preoperative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal testing, though he reported no respiratory symptoms or fever. During the delay, the primary team prescribed daily oral rivaroxaban for thrombosis prophylaxis in addition to clopidogrel. One week prior to surgery, his repeat COVID-19 test was negative and prophylactic anticoagulation stopped.

On the day of surgery, the patient was hemodynamically stable: heart rate 86 beats/min, blood pressure 167/93 mm Hg (baseline 120-150 mm Hg systolic pressure), respiratory rate 16 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 99% without supplemental oxygen, temperature 97.1 °F. He received amlodipine and clopidogrel, but not lisinopril, that morning. No focal neurologic deficits were appreciated on preoperative examination, and resolution of symptoms related to the 2 prior MIs was confirmed. Preoperative glucose was 163 mg/dL. Femoral and sciatic peripheral nerve blocks were done for postoperative analgesia. A preinduction arterial line was placed and 2 mg of midazolam was administered for anxiolysis. Induction of general anesthesia with oral endotracheal intubation proceeded uneventfully; he was positioned prone.

Given his stroke risk factors, mean arterial pressure was maintained > 70 mm Hg for the duration of surgery. No vasoactive infusions were necessary and no β-blocking agents were administered. Insulin infusion was required; the maximum-recorded glucose was 219 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas samples were routinely drawn; acid-base balance was well maintained, PaO2 was > 185 mm Hg, and PaCO2 ranged from 29.4 to 38.5 mm Hg. The patient received 2 units of packed red blood cells for nadir hemoglobin of 7.5 mg/dL. At surgery end, we fully reversed neuromuscular blockade with suggamadex. The patient was returned to a supine position and extubated uneventfully after demonstrating the ability to follow commands.

During postanesthesia care unit (PACU) handoff, the patient exhibited acute speech impairment. He was able to state his name on repetition but seemed confused and sedated. Prompt formal neurology evaluation (stroke code) was sought. Initial National Institutes of Health (NIH) stroke scale score was 8 (1 for level of consciousness, 1 for minor right facial droop, 1 for right arm drift, 3 for right leg with no effort against gravity, 1 for right partial sensory loss, and 1 for mild dysarthria). The patient was oriented only to self. Other findings included mild right facial droop and dysarthria. On a 5-point strength scale, he scored 4 for the right deltoid, biceps, triceps, wrist extensors, right knee flexion, right dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion, 2 for right hip flexion, and ≥ 4 for right knee extension. Positive sensory findings were notable for decreased pin prick sensation on the right limbs.

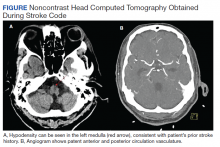

We obtained emergent head computed tomography (CT) that was negative for acute abnormalities; CT angiography was negative for large vessel occlusion or clinically significant stenosis (Figure). On returning to the PACU from the CT scanner, the patient regained symmetric strength in both arms, right leg was antigravity, and his speech had normalized. Prior to PACU discharge 2 hours later, the patient was back to his prehospitalization neurologic function and NIH stroke scale was 0. Given this rapid clinical resolution, no acute stroke interventions were done, though permissive hypertension was recommended by the neurologist during PACU recovery.

The neurology team concluded that the patient’s symptoms were likely secondary to recrudescence of previous stroke symptoms in the setting of brief postoperative delirium (POD). However, we could not exclude transient ischemic attack or new cardioembolism, therefore patient was started on dual antiplatelet therapy for 3 weeks. Unfortunately, elective confirmatory magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not sought to confirm new ischemic changes due hospital COVID-19 restrictions on nonessential scanning. Neurology did not recommend carotid duplex ultrasound given patent vasculature on the head and neck CT angiography. Finally, the patient had undergone surface echocardiography 3 weeks prior to surgery that showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% without significant valvular abnormalities, thrombus, or interatrial shunting, so repeated study was deferred.

Formal neurology consultation did not extend beyond postoperative day 1. One month after surgery, the anesthesiology team visited the patient during inpatient rehabilitation; he had not developed further focal neurologic symptoms or delirium. His strength was equal bilaterally and no speech deficits were noted. Unfortunately, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for continued foot wound drainage 2 months postoperatively, though no focal neurologic deficits were documented on his medical admission history and physical. No long term sequalae of his COVID-19 infection have been suspected.

Discussion

We report a veteran with prior stroke and COVID-19 who experienced postoperative speech and motor deficit despite deliberate risk factor mitigation. This case calls for increased vigilance by anesthesia providers to employ proper perioperative stroke management and anticoagulation strategies, and to be prepared for prompt intervention with COVID-19-sensitive practices should the need for advanced airway management or thrombectomy arises.

The exact etiology of the postoperative neurologic deficit in our patient is unknown. The most likely possibility is that this represents poststroke recrudescence (PSR), knowing he had a previous left medullary infarct that presented similarly.11 PSR is a phenomenon in which prior stroke symptoms recur acutely and transiently in the setting of physiologic stressors—also known as locus minoris resistantiae.12 Triggers include γ aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediating anesthetic agents such as midazolam, opioids (eg, fentanyl or hydromorphone), infection, or relative cerebral hypoperfusion.11,13,14 The focality of our patient’s presentation favors PSR in the context of brief POD; of note, these entities share similar risk factors.15 Our patient did indeed receive low-dose preoperative midazolam in the context of mild preoperative neurocognitive deficit, which may have predisposed him to POD.

Though less likely, our patient’s presentation could have been explained by a new cerebrovascular event—transient ischemic attack vs new MI. Speech and right-sided motor/sensory deficits can localize to the left middle cerebral artery or small penetrating arteries of the left brainstem or deep white matter. MRI was not performed to exclude this possibility due to hospital-wide COVID-19 precautions minimizing nonessential MRIs unlikely to change clinical management. We speculate, however, that due to recent SARS-CoV-2 infection, our patient may have been at higher risk for cerebrovascular events due to subclinical endothelial damage and/or microclot in predisposed neurovasculature. Though our patient had interval COVID-19 negative tests, the timeframe of coronavirus procoagulant effects is unknown.16

There are well-established guidelines for perioperative stroke management published by the Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care (SNACC).17 This case exemplifies many recommendations including tight hemodynamic and glucose control, optimized oxygen delivery, avoidance of intraoperative β blockade, and prompt neurologic consultation. Additionally, special precaution was taken to ensure continuation of antiplatelet therapy on the day of surgery; in light of COVID-19 prothrombosis risk we considered this essential. Low-dose enoxaparin was also instituted on postoperative day 1. Prophylactic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended for hospitalized COVID-19–positive patients, though perioperatively, this must be weighed against hemorrhagic stroke transformation and surgical bleeding.8,16 Interestingly, the benefit of LMWH may partly relate to its anti-inflammatory effects, of which higher levels are observed in COVID-19.16,18

Though substantial health care provider energy and hospital resource utilization is presently focused on controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of appropriate stroke code processes must not be neglected. Recently, SNACC released anesthetic guidelines for endovascular ischemic stroke management that reflect COVID-19 precautions; highlights include personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, risk-benefit analysis of general anesthesia (with early decision to intubate) vs sedation techniques for thrombectomy, and airway management strategies to minimize aerosolization exposure.19 Finally, negative pressure rooms relative to PACU and operating room locations need to be known and marked, as well as the necessary airway equipment and PPE to transfer patients safely to and from angiography suites.

Conclusions

We discuss a surgical patient with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection at elevated stroke risk that experienced recurrence of neurologic deficits postoperatively. This case informs anesthesia providers of the broad differential diagnosis for focal neurological deficits to include PSR and the possible contribution of COVID-19 to elevated acute stroke risk. Perioperative physicians, including VHA practitioners, with knowledge of current COVID-19 practices are primed to coordinate multidisciplinary efforts during stroke codes and ensuring appropriate anticoagulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank perioperative care teams across the world caring for COVID-19 patients safely.

1. Vlisides P, Mashour GA. Perioperative stroke. Can J Anaesth. 2016;63(2):193-204. doi:10.1007/s12630-015-0494-9

2. Mashour GA, Shanks AM, Kheterpal S. Perioperative stroke and associated mortality after noncardiac, nonneurologic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(6):1289-1296. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318216e7f4

3. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157-160. Published 2020 Mar 19. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

4. Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, et al. Covid-19 by Race and Ethnicity: A National Cohort Study of 6 Million United States Veterans. Preprint. medRxiv. 2020;2020.05.12.20099135. Published 2020 May 18. doi:10.1101/2020.05.12.20099135

5. Montalvan V, Lee J, Bueso T, De Toledo J, Rivas K. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: A systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;194:105921. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921

6. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683-690. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

7. Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2009787

8. Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(8):889-891. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586

9. Needham EJ, Chou SH, Coles AJ, Menon DK. Neurological Implications of COVID-19 Infections. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32(3):667-671. doi:10.1007/s12028-020-00978-4

10. Lich KH, Tian Y, Beadles CA, et al. Strategic planning to reduce the burden of stroke among veterans: using simulation modeling to inform decision making. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2078-2084. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004694

11. Topcuoglu MA, Saka E, Silverman SB, Schwamm LH, Singhal AB. Recrudescence of Deficits After Stroke: Clinical and Imaging Phenotype, Triggers, and Risk Factors. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(9):1048-1055. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1668

12. Jun-O’connell AH, Henninger N, Moonis M, Silver B, Ionete C, Goddeau RP. Recrudescence of old stroke deficits among transient neurological attacks. Neurohospitalist. 2019;9(4):183-189. doi:10.1177/194187441982928813. Karnik HS, Jain RA. Anesthesia for patients with prior stroke. J Neuroanaesthesiology Crit Care. 2018;5(3):150-157. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1673549

14. Minhas JS, Rook W, Panerai RB, et al. Pathophysiological and clinical considerations in the perioperative care of patients with a previous ischaemic stroke: a multidisciplinary narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124(2):183-196. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.10.021

15. Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium [published correction appears in Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018 Sep;35(9):718-719]. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34(4):192-214. doi:10.1097/EJA.0000000000000594

16. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810

17. Mashour GA, Moore LE, Lele AV, Robicsek SA, Gelb AW. Perioperative care of patients at high risk for stroke during or after non-cardiac, non-neurologic surgery: consensus statement from the Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care*. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26(4):273-285. doi:10.1097/ana.0000000000000087

18. Ghannam M, Alshaer Q, Al-Chalabi M, Zakarna L, Robertson J, Manousakis G. Neurological involvement of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2020;267(11):3135-3153. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09990-2

19. Sharma D, Rasmussen M, Han R, et al. Anesthetic Management of Endovascular Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke During COVID-19 Pandemic: Consensus Statement From Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology & Critical Care (SNACC): Endorsed by Society of Vascular & Interventional Neurology (SVIN), Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), Neurocritical Care Society (NCS), European Society of Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) and American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) and Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) Cerebrovascular Section. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2020;32(3):193-201. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000688

Anesthesia providers should be aware of COVID-19 sensitive stroke code practices and maintain heightened vigilance for the need to implement perioperative stroke mitigation strategies.

Anesthesia providers should be aware of COVID-19 sensitive stroke code practices and maintain heightened vigilance for the need to implement perioperative stroke mitigation strategies.

The risk of perioperative stroke in noncardiac, nonneurologic, nonvascular surgery ranges from 0.1 to 1.9% and is associated with increased mortality.1,2 Stroke mechanisms include both ischemia (large and small vessel occlusion, cardioembolism, anemic-tissue hypoxia, cerebral hypoperfusion) and hemorrhage.1 Risk factors for perioperative stroke include prior cerebral vascular accident (CVA), hypertension, aged > 62 years, acute renal insufficiency, dialysis, and recent myocardial infarction (MI).2

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020.3 COVID-19 has certainly affected the veteran population; between February and May 2020, more than 60,000 veterans were tested for COVID-19 with a positive rate of about 9%.4 While primarily affecting the respiratory system, there are increasing reports of COVID-19 neurologic manifestations: headache, hypogeusia, hyposomia, seizure, encephalitis, and acute stroke.5 In an early case series from Wuhan, China, 36% of 214 patients with COVID-19 reported neurologic complications, and acute CVAs were more common in patients with severe (compared to milder) viral disease presentations (5.7% vs 0.8%).6 Large vessel stroke was a presenting feature in another report of 5 patients aged < 50 years.7

The mechanism of ischemic stroke in the setting of COVID-19 is unclear.8 Indeed, stroke and COVID-19 share similar risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus [DM], older age), and immobile critically ill patients may already be prone to developing stroke.5,9 However, COVID-19 is associated with arterial and venous thromboembolism, elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, and antiphospholipid antibody production. This prothrombotic state may be linked to cytokine-induced endothelial damage, mononuclear cell activation, tissue factor expression, and ultimately thrombin propagation and platelet activation.8

The rates of perioperative stroke may change as more patients with COVID-19 present for surgery, and the anesthesiology care team must prioritize mitigation efforts in high-risk patients, including veterans. Reducing the elevated stroke burden within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a public health priority.10 We present the case of a veteran with prior CVA and recent positive COVID-19 testing who experienced transient weakness and dysarthria following plastic surgery. The patient discussed provided written Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act consent for publication of this report.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old male veteran presented to the Minneapolis VA Medical Center in Minnesota with chronic left foot ulceration necessitating debridement and flap coverage. His medical history was significant for hypertension, type 2 DM, anemia of chronic disease, and coronary artery disease (left ventricular ejection fraction, 50%). Additionally, he had prior ischemic strokes in the oculomotor nucleus (in 2004 with internuclear ophthalmoplegia) and left ventral medulla (in 2019 with right hemiparesis). During his 2019 poststroke rehabilitation, he was diagnosed with mild neurocognitive deficit not attributable to his strokes. The patient’s medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, atorvastatin, clopidogrel (lifelong for secondary stroke prevention), metformin, and glipizide. The debridement procedure was initially delayed 3 weeks due to positive routine preoperative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal testing, though he reported no respiratory symptoms or fever. During the delay, the primary team prescribed daily oral rivaroxaban for thrombosis prophylaxis in addition to clopidogrel. One week prior to surgery, his repeat COVID-19 test was negative and prophylactic anticoagulation stopped.

On the day of surgery, the patient was hemodynamically stable: heart rate 86 beats/min, blood pressure 167/93 mm Hg (baseline 120-150 mm Hg systolic pressure), respiratory rate 16 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 99% without supplemental oxygen, temperature 97.1 °F. He received amlodipine and clopidogrel, but not lisinopril, that morning. No focal neurologic deficits were appreciated on preoperative examination, and resolution of symptoms related to the 2 prior MIs was confirmed. Preoperative glucose was 163 mg/dL. Femoral and sciatic peripheral nerve blocks were done for postoperative analgesia. A preinduction arterial line was placed and 2 mg of midazolam was administered for anxiolysis. Induction of general anesthesia with oral endotracheal intubation proceeded uneventfully; he was positioned prone.

Given his stroke risk factors, mean arterial pressure was maintained > 70 mm Hg for the duration of surgery. No vasoactive infusions were necessary and no β-blocking agents were administered. Insulin infusion was required; the maximum-recorded glucose was 219 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas samples were routinely drawn; acid-base balance was well maintained, PaO2 was > 185 mm Hg, and PaCO2 ranged from 29.4 to 38.5 mm Hg. The patient received 2 units of packed red blood cells for nadir hemoglobin of 7.5 mg/dL. At surgery end, we fully reversed neuromuscular blockade with suggamadex. The patient was returned to a supine position and extubated uneventfully after demonstrating the ability to follow commands.

During postanesthesia care unit (PACU) handoff, the patient exhibited acute speech impairment. He was able to state his name on repetition but seemed confused and sedated. Prompt formal neurology evaluation (stroke code) was sought. Initial National Institutes of Health (NIH) stroke scale score was 8 (1 for level of consciousness, 1 for minor right facial droop, 1 for right arm drift, 3 for right leg with no effort against gravity, 1 for right partial sensory loss, and 1 for mild dysarthria). The patient was oriented only to self. Other findings included mild right facial droop and dysarthria. On a 5-point strength scale, he scored 4 for the right deltoid, biceps, triceps, wrist extensors, right knee flexion, right dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion, 2 for right hip flexion, and ≥ 4 for right knee extension. Positive sensory findings were notable for decreased pin prick sensation on the right limbs.

We obtained emergent head computed tomography (CT) that was negative for acute abnormalities; CT angiography was negative for large vessel occlusion or clinically significant stenosis (Figure). On returning to the PACU from the CT scanner, the patient regained symmetric strength in both arms, right leg was antigravity, and his speech had normalized. Prior to PACU discharge 2 hours later, the patient was back to his prehospitalization neurologic function and NIH stroke scale was 0. Given this rapid clinical resolution, no acute stroke interventions were done, though permissive hypertension was recommended by the neurologist during PACU recovery.

The neurology team concluded that the patient’s symptoms were likely secondary to recrudescence of previous stroke symptoms in the setting of brief postoperative delirium (POD). However, we could not exclude transient ischemic attack or new cardioembolism, therefore patient was started on dual antiplatelet therapy for 3 weeks. Unfortunately, elective confirmatory magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not sought to confirm new ischemic changes due hospital COVID-19 restrictions on nonessential scanning. Neurology did not recommend carotid duplex ultrasound given patent vasculature on the head and neck CT angiography. Finally, the patient had undergone surface echocardiography 3 weeks prior to surgery that showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% without significant valvular abnormalities, thrombus, or interatrial shunting, so repeated study was deferred.

Formal neurology consultation did not extend beyond postoperative day 1. One month after surgery, the anesthesiology team visited the patient during inpatient rehabilitation; he had not developed further focal neurologic symptoms or delirium. His strength was equal bilaterally and no speech deficits were noted. Unfortunately, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for continued foot wound drainage 2 months postoperatively, though no focal neurologic deficits were documented on his medical admission history and physical. No long term sequalae of his COVID-19 infection have been suspected.

Discussion

We report a veteran with prior stroke and COVID-19 who experienced postoperative speech and motor deficit despite deliberate risk factor mitigation. This case calls for increased vigilance by anesthesia providers to employ proper perioperative stroke management and anticoagulation strategies, and to be prepared for prompt intervention with COVID-19-sensitive practices should the need for advanced airway management or thrombectomy arises.

The exact etiology of the postoperative neurologic deficit in our patient is unknown. The most likely possibility is that this represents poststroke recrudescence (PSR), knowing he had a previous left medullary infarct that presented similarly.11 PSR is a phenomenon in which prior stroke symptoms recur acutely and transiently in the setting of physiologic stressors—also known as locus minoris resistantiae.12 Triggers include γ aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediating anesthetic agents such as midazolam, opioids (eg, fentanyl or hydromorphone), infection, or relative cerebral hypoperfusion.11,13,14 The focality of our patient’s presentation favors PSR in the context of brief POD; of note, these entities share similar risk factors.15 Our patient did indeed receive low-dose preoperative midazolam in the context of mild preoperative neurocognitive deficit, which may have predisposed him to POD.

Though less likely, our patient’s presentation could have been explained by a new cerebrovascular event—transient ischemic attack vs new MI. Speech and right-sided motor/sensory deficits can localize to the left middle cerebral artery or small penetrating arteries of the left brainstem or deep white matter. MRI was not performed to exclude this possibility due to hospital-wide COVID-19 precautions minimizing nonessential MRIs unlikely to change clinical management. We speculate, however, that due to recent SARS-CoV-2 infection, our patient may have been at higher risk for cerebrovascular events due to subclinical endothelial damage and/or microclot in predisposed neurovasculature. Though our patient had interval COVID-19 negative tests, the timeframe of coronavirus procoagulant effects is unknown.16

There are well-established guidelines for perioperative stroke management published by the Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care (SNACC).17 This case exemplifies many recommendations including tight hemodynamic and glucose control, optimized oxygen delivery, avoidance of intraoperative β blockade, and prompt neurologic consultation. Additionally, special precaution was taken to ensure continuation of antiplatelet therapy on the day of surgery; in light of COVID-19 prothrombosis risk we considered this essential. Low-dose enoxaparin was also instituted on postoperative day 1. Prophylactic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended for hospitalized COVID-19–positive patients, though perioperatively, this must be weighed against hemorrhagic stroke transformation and surgical bleeding.8,16 Interestingly, the benefit of LMWH may partly relate to its anti-inflammatory effects, of which higher levels are observed in COVID-19.16,18

Though substantial health care provider energy and hospital resource utilization is presently focused on controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of appropriate stroke code processes must not be neglected. Recently, SNACC released anesthetic guidelines for endovascular ischemic stroke management that reflect COVID-19 precautions; highlights include personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization, risk-benefit analysis of general anesthesia (with early decision to intubate) vs sedation techniques for thrombectomy, and airway management strategies to minimize aerosolization exposure.19 Finally, negative pressure rooms relative to PACU and operating room locations need to be known and marked, as well as the necessary airway equipment and PPE to transfer patients safely to and from angiography suites.

Conclusions

We discuss a surgical patient with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection at elevated stroke risk that experienced recurrence of neurologic deficits postoperatively. This case informs anesthesia providers of the broad differential diagnosis for focal neurological deficits to include PSR and the possible contribution of COVID-19 to elevated acute stroke risk. Perioperative physicians, including VHA practitioners, with knowledge of current COVID-19 practices are primed to coordinate multidisciplinary efforts during stroke codes and ensuring appropriate anticoagulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank perioperative care teams across the world caring for COVID-19 patients safely.

The risk of perioperative stroke in noncardiac, nonneurologic, nonvascular surgery ranges from 0.1 to 1.9% and is associated with increased mortality.1,2 Stroke mechanisms include both ischemia (large and small vessel occlusion, cardioembolism, anemic-tissue hypoxia, cerebral hypoperfusion) and hemorrhage.1 Risk factors for perioperative stroke include prior cerebral vascular accident (CVA), hypertension, aged > 62 years, acute renal insufficiency, dialysis, and recent myocardial infarction (MI).2

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020.3 COVID-19 has certainly affected the veteran population; between February and May 2020, more than 60,000 veterans were tested for COVID-19 with a positive rate of about 9%.4 While primarily affecting the respiratory system, there are increasing reports of COVID-19 neurologic manifestations: headache, hypogeusia, hyposomia, seizure, encephalitis, and acute stroke.5 In an early case series from Wuhan, China, 36% of 214 patients with COVID-19 reported neurologic complications, and acute CVAs were more common in patients with severe (compared to milder) viral disease presentations (5.7% vs 0.8%).6 Large vessel stroke was a presenting feature in another report of 5 patients aged < 50 years.7

The mechanism of ischemic stroke in the setting of COVID-19 is unclear.8 Indeed, stroke and COVID-19 share similar risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus [DM], older age), and immobile critically ill patients may already be prone to developing stroke.5,9 However, COVID-19 is associated with arterial and venous thromboembolism, elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, and antiphospholipid antibody production. This prothrombotic state may be linked to cytokine-induced endothelial damage, mononuclear cell activation, tissue factor expression, and ultimately thrombin propagation and platelet activation.8

The rates of perioperative stroke may change as more patients with COVID-19 present for surgery, and the anesthesiology care team must prioritize mitigation efforts in high-risk patients, including veterans. Reducing the elevated stroke burden within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a public health priority.10 We present the case of a veteran with prior CVA and recent positive COVID-19 testing who experienced transient weakness and dysarthria following plastic surgery. The patient discussed provided written Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act consent for publication of this report.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old male veteran presented to the Minneapolis VA Medical Center in Minnesota with chronic left foot ulceration necessitating debridement and flap coverage. His medical history was significant for hypertension, type 2 DM, anemia of chronic disease, and coronary artery disease (left ventricular ejection fraction, 50%). Additionally, he had prior ischemic strokes in the oculomotor nucleus (in 2004 with internuclear ophthalmoplegia) and left ventral medulla (in 2019 with right hemiparesis). During his 2019 poststroke rehabilitation, he was diagnosed with mild neurocognitive deficit not attributable to his strokes. The patient’s medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, atorvastatin, clopidogrel (lifelong for secondary stroke prevention), metformin, and glipizide. The debridement procedure was initially delayed 3 weeks due to positive routine preoperative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal testing, though he reported no respiratory symptoms or fever. During the delay, the primary team prescribed daily oral rivaroxaban for thrombosis prophylaxis in addition to clopidogrel. One week prior to surgery, his repeat COVID-19 test was negative and prophylactic anticoagulation stopped.

On the day of surgery, the patient was hemodynamically stable: heart rate 86 beats/min, blood pressure 167/93 mm Hg (baseline 120-150 mm Hg systolic pressure), respiratory rate 16 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 99% without supplemental oxygen, temperature 97.1 °F. He received amlodipine and clopidogrel, but not lisinopril, that morning. No focal neurologic deficits were appreciated on preoperative examination, and resolution of symptoms related to the 2 prior MIs was confirmed. Preoperative glucose was 163 mg/dL. Femoral and sciatic peripheral nerve blocks were done for postoperative analgesia. A preinduction arterial line was placed and 2 mg of midazolam was administered for anxiolysis. Induction of general anesthesia with oral endotracheal intubation proceeded uneventfully; he was positioned prone.

Given his stroke risk factors, mean arterial pressure was maintained > 70 mm Hg for the duration of surgery. No vasoactive infusions were necessary and no β-blocking agents were administered. Insulin infusion was required; the maximum-recorded glucose was 219 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas samples were routinely drawn; acid-base balance was well maintained, PaO2 was > 185 mm Hg, and PaCO2 ranged from 29.4 to 38.5 mm Hg. The patient received 2 units of packed red blood cells for nadir hemoglobin of 7.5 mg/dL. At surgery end, we fully reversed neuromuscular blockade with suggamadex. The patient was returned to a supine position and extubated uneventfully after demonstrating the ability to follow commands.