User login

CRP as a biomarker for community-acquired pneumonia

Background: In the United States, CAP was responsible for nearly 50,000 deaths in 2017. Prompt and accurate diagnosis promotes early treatment and avoids unnecessary antibiotic treatment for nonpneumonia lower respiratory tract infection patients. Diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms, as well as available imaging. Inflammatory markers such as CRP, white blood cell count, and procalcitonin are readily available in the ED and outpatient settings.

Study design: Bivariate meta-analysis.

Setting: A systematic review of literature was done via PubMed search to identify prospective studies evaluating the accuracy of biomarkers in patients with cough or suspected CAP.

Synopsis: Fourteen studies met the criteria to be included in the meta-analysis. Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves generated reported area under the curve of 0.802 for CRP (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.85), 0.777 for leukocytosis (95% CI, 0.74-0.81), and 0.771 for procalcitonin (95% CI, 0.74-0.81). The combination of CRP greater than 49.5 mg/L and procalcitonin greater than 0.1 mcg/L had a positive likelihood ratio of 2.24 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.44.

The study had a some of limitations. The blinding of the person performing the index test to the reference standard and vice versa was not clear. Further, it was unclear if the person interpreting the reference standard was blinded to the index test in five studies and absent in one. Other limitations were inconsistent reporting of abnormal post hoc cutoffs and only two biomarkers being reported in a single study.

Combining a biomarker with signs and symptoms has the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy in the outpatient setting further. CRP was found to be most accurate regardless of the cutoff used; however, further studies without threshold effect will prove beneficial.

Bottom line: CRP is a more accurate and useful biomarker for outpatient CAP diagnosis than procalcitonin or leukocytosis.

Citation: Ebell MH et al. Accuracy of biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):195-206.

Dr. Castellanos is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: In the United States, CAP was responsible for nearly 50,000 deaths in 2017. Prompt and accurate diagnosis promotes early treatment and avoids unnecessary antibiotic treatment for nonpneumonia lower respiratory tract infection patients. Diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms, as well as available imaging. Inflammatory markers such as CRP, white blood cell count, and procalcitonin are readily available in the ED and outpatient settings.

Study design: Bivariate meta-analysis.

Setting: A systematic review of literature was done via PubMed search to identify prospective studies evaluating the accuracy of biomarkers in patients with cough or suspected CAP.

Synopsis: Fourteen studies met the criteria to be included in the meta-analysis. Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves generated reported area under the curve of 0.802 for CRP (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.85), 0.777 for leukocytosis (95% CI, 0.74-0.81), and 0.771 for procalcitonin (95% CI, 0.74-0.81). The combination of CRP greater than 49.5 mg/L and procalcitonin greater than 0.1 mcg/L had a positive likelihood ratio of 2.24 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.44.

The study had a some of limitations. The blinding of the person performing the index test to the reference standard and vice versa was not clear. Further, it was unclear if the person interpreting the reference standard was blinded to the index test in five studies and absent in one. Other limitations were inconsistent reporting of abnormal post hoc cutoffs and only two biomarkers being reported in a single study.

Combining a biomarker with signs and symptoms has the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy in the outpatient setting further. CRP was found to be most accurate regardless of the cutoff used; however, further studies without threshold effect will prove beneficial.

Bottom line: CRP is a more accurate and useful biomarker for outpatient CAP diagnosis than procalcitonin or leukocytosis.

Citation: Ebell MH et al. Accuracy of biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):195-206.

Dr. Castellanos is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Background: In the United States, CAP was responsible for nearly 50,000 deaths in 2017. Prompt and accurate diagnosis promotes early treatment and avoids unnecessary antibiotic treatment for nonpneumonia lower respiratory tract infection patients. Diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms, as well as available imaging. Inflammatory markers such as CRP, white blood cell count, and procalcitonin are readily available in the ED and outpatient settings.

Study design: Bivariate meta-analysis.

Setting: A systematic review of literature was done via PubMed search to identify prospective studies evaluating the accuracy of biomarkers in patients with cough or suspected CAP.

Synopsis: Fourteen studies met the criteria to be included in the meta-analysis. Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves generated reported area under the curve of 0.802 for CRP (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.85), 0.777 for leukocytosis (95% CI, 0.74-0.81), and 0.771 for procalcitonin (95% CI, 0.74-0.81). The combination of CRP greater than 49.5 mg/L and procalcitonin greater than 0.1 mcg/L had a positive likelihood ratio of 2.24 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.44.

The study had a some of limitations. The blinding of the person performing the index test to the reference standard and vice versa was not clear. Further, it was unclear if the person interpreting the reference standard was blinded to the index test in five studies and absent in one. Other limitations were inconsistent reporting of abnormal post hoc cutoffs and only two biomarkers being reported in a single study.

Combining a biomarker with signs and symptoms has the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy in the outpatient setting further. CRP was found to be most accurate regardless of the cutoff used; however, further studies without threshold effect will prove beneficial.

Bottom line: CRP is a more accurate and useful biomarker for outpatient CAP diagnosis than procalcitonin or leukocytosis.

Citation: Ebell MH et al. Accuracy of biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):195-206.

Dr. Castellanos is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UK HealthCare, Lexington, Ky.

Q&A: Get flu shot early this year? Same time as COVID vaccine?

With first-time COVID-19 immunizations continuing and the plan to offer booster vaccines to most Americans starting next month, what are the considerations for getting COVID-19 and flu shots at the same time?

This news organization asked Andrew T. Pavia, MD, for his advice. He is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a fellow of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Q: With COVID-19 cases surging, is it a good idea to get the flu shot early this season?

Dr. Pavia: I don’t think there is a rush to do it in August, but it is a good idea to get a flu shot this season. The consequences of getting the flu while COVID is circulating are serious.

Q: What are the implications?

There are some we know and some we don’t know. If you develop flu-like symptoms, you’re going to have to get tested. You’re going to have to stay home quite a bit longer if you get a definitive (positive COVID-19) test than you would simply with flu symptoms. Also, you’re probably going to miss work when your workplace is very stressed or your children are stressed by having COVID circulating in schools.

The part we know less about are the implications of getting the flu and COVID together. There is some reason to believe if you get them together, the illness will be more severe. We are seeing that with RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) and parainfluenza and COVID coinfections in children. They appear to be quite severe.

But for flu, we just don’t have the data yet. That’s because there really was no cocirculation of COVID and influenza with the exception of parts of China for a brief part of February and March.

Q: Will the planned administration of booster COVID-19 shots this fall affect the number of people who get the flu vaccine or how it’s distributed?

It creates a lot of logistical challenges, particularly for hospitals and other places that need to vaccinate a large number of their employees for flu and that will need to give COVID boosters at about the same time period. It also creates logistical challenges for doctors’ offices.

But we don’t know of any reason why you can’t give the two shots together.

Q: Is it possible flu season will be more severe because we isolated and wore masks, etc., last winter? Any science behind that?

The more you study flu, the less you can predict, and I’ve been studying flu for a long time. There are reasons that might suggest a severe flu season – there has been limited immunity, and some people are not wearing masks effectively and they are gathering again. Those are things we believe protected us from influenza last season.

But we have not seen flu emerge yet. Normally we look to Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa during their winter – which is our summer – to get some idea of what is over the horizon for the Northern Hemisphere. Flu activity in Australia has been very modest this year.

That might mean flu may not show up for a while, but I would be loathe to make a prediction.

Q: What are the chances we’ll see a flu outbreak like we’re seeing with RSV, which is normally a winter illness?

The fact that we had a summer RSV surge just gives you an idea of how the normal epidemiology of viral infections has been disrupted. It means anything could happen with influenza. It could show up late summer or fall or wait until next spring.

We really don’t understand how those interactions work. When a new flu strain emerges, it often ignores the traditional behavior and shows up in the spring or fall. It happened in the 2009 pandemic, it happened in 1918.

The one thing I would safely predict about the next flu wave is that it will surprise us.

Q: Are you hopeful that combination vaccines in development from a number of companies, such as Moderna, Novavax, and Vivaldi, will be effective?

It is beginning to look like COVID will be with us for the foreseeable future – maybe as a seasonal virus or maybe as an ongoing pandemic. We are going to need to protect (ourselves) simultaneously against the flu and COVID. A single shot is a great way to do that – nobody wants two needles; nobody wants two trips to get vaccinated.

An effective combination vaccine would be a really great tool.

We have to wait to see what the science shows us, because they are quite different viruses. We won’t know if a combination vaccine works well and has acceptable side effects until we do those studies.

Q. Do you know at this point whether the side effects from two vaccines would be additive? Is there any way to predict that?

There is no way to predict. There are so many things that go into whether someone has side effects that we don’t understand. With fairly reactogenic vaccines like the mRNA vaccines, lots of people have no side effects whatsoever and others are really uncomfortable for 24 hours.

Flu is generally a better tolerated vaccine. There are still people who get muscle aches and very sore arms. I don’t think we can predict if getting two will be additive or just the same as getting one vaccine.

Q: Other than convenience and the benefit for people who are needle-phobic, are there any other advantages of combining them into one shot?

The logistics alone are enough to justify having one effective product if we can make one. It should reduce the overall cost of administration and reduce time off from work.

The combination vaccines given by pediatricians have been very successful. They reduce the number of needles for kids and make it much easier for parents and the pediatricians administering them. The same principle should apply to adults, who sometimes are less brave about needles than kids are.

Historically, combined vaccines in general have worked as well as vaccines given alone, but there have been exceptions. We just have to see what the products look like.

Q: For now, the flu vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine are single products. If you get them separately, is it better to put some time between the two?

We don’t know. There are studies that probably won’t be out in time to decide in September. They are looking at whether you get an equivalent immune response if you give them together or apart.

For now, I would say the advantage of getting them together is if you do get side effects, you’ll only get them once – one day to suffer through them. Also, it’s one trip to the doctor.

The potential advantage of separating them is that is how we developed and tested the vaccines. If you do react to them, side effects could be milder, but it will be on two separate days.

I would recommend doing whatever works so that you get both vaccines in a timely manner.

I’m going to get my flu shot as soon as it’s available. If I’m due for a COVID booster at that time, I would probably do them together.

Q: Do you foresee a point in the future when the predominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 will be one of the components of a flu vaccine, like we did in the past with H1N1, etc?

It really remains to be seen, but it is very conceivable it could happen. The same companies that developed COVID-19 vaccines are working on flu vaccines.

Q: Any other advice for people concerned about getting immunized against both COVID-19 and influenza in the coming months?

There is no side effect of the vaccine that begins to approach the risk you face from either disease. It’s really one of the best things you can do to protect yourself is to get vaccinated.

In the case of flu, the vaccine is only modestly effective, but it still saves tens of thousands of lives each year. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is a much better vaccine and a deadlier disease.

Dr. Pavia consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on influenza testing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With first-time COVID-19 immunizations continuing and the plan to offer booster vaccines to most Americans starting next month, what are the considerations for getting COVID-19 and flu shots at the same time?

This news organization asked Andrew T. Pavia, MD, for his advice. He is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a fellow of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Q: With COVID-19 cases surging, is it a good idea to get the flu shot early this season?

Dr. Pavia: I don’t think there is a rush to do it in August, but it is a good idea to get a flu shot this season. The consequences of getting the flu while COVID is circulating are serious.

Q: What are the implications?

There are some we know and some we don’t know. If you develop flu-like symptoms, you’re going to have to get tested. You’re going to have to stay home quite a bit longer if you get a definitive (positive COVID-19) test than you would simply with flu symptoms. Also, you’re probably going to miss work when your workplace is very stressed or your children are stressed by having COVID circulating in schools.

The part we know less about are the implications of getting the flu and COVID together. There is some reason to believe if you get them together, the illness will be more severe. We are seeing that with RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) and parainfluenza and COVID coinfections in children. They appear to be quite severe.

But for flu, we just don’t have the data yet. That’s because there really was no cocirculation of COVID and influenza with the exception of parts of China for a brief part of February and March.

Q: Will the planned administration of booster COVID-19 shots this fall affect the number of people who get the flu vaccine or how it’s distributed?

It creates a lot of logistical challenges, particularly for hospitals and other places that need to vaccinate a large number of their employees for flu and that will need to give COVID boosters at about the same time period. It also creates logistical challenges for doctors’ offices.

But we don’t know of any reason why you can’t give the two shots together.

Q: Is it possible flu season will be more severe because we isolated and wore masks, etc., last winter? Any science behind that?

The more you study flu, the less you can predict, and I’ve been studying flu for a long time. There are reasons that might suggest a severe flu season – there has been limited immunity, and some people are not wearing masks effectively and they are gathering again. Those are things we believe protected us from influenza last season.

But we have not seen flu emerge yet. Normally we look to Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa during their winter – which is our summer – to get some idea of what is over the horizon for the Northern Hemisphere. Flu activity in Australia has been very modest this year.

That might mean flu may not show up for a while, but I would be loathe to make a prediction.

Q: What are the chances we’ll see a flu outbreak like we’re seeing with RSV, which is normally a winter illness?

The fact that we had a summer RSV surge just gives you an idea of how the normal epidemiology of viral infections has been disrupted. It means anything could happen with influenza. It could show up late summer or fall or wait until next spring.

We really don’t understand how those interactions work. When a new flu strain emerges, it often ignores the traditional behavior and shows up in the spring or fall. It happened in the 2009 pandemic, it happened in 1918.

The one thing I would safely predict about the next flu wave is that it will surprise us.

Q: Are you hopeful that combination vaccines in development from a number of companies, such as Moderna, Novavax, and Vivaldi, will be effective?

It is beginning to look like COVID will be with us for the foreseeable future – maybe as a seasonal virus or maybe as an ongoing pandemic. We are going to need to protect (ourselves) simultaneously against the flu and COVID. A single shot is a great way to do that – nobody wants two needles; nobody wants two trips to get vaccinated.

An effective combination vaccine would be a really great tool.

We have to wait to see what the science shows us, because they are quite different viruses. We won’t know if a combination vaccine works well and has acceptable side effects until we do those studies.

Q. Do you know at this point whether the side effects from two vaccines would be additive? Is there any way to predict that?

There is no way to predict. There are so many things that go into whether someone has side effects that we don’t understand. With fairly reactogenic vaccines like the mRNA vaccines, lots of people have no side effects whatsoever and others are really uncomfortable for 24 hours.

Flu is generally a better tolerated vaccine. There are still people who get muscle aches and very sore arms. I don’t think we can predict if getting two will be additive or just the same as getting one vaccine.

Q: Other than convenience and the benefit for people who are needle-phobic, are there any other advantages of combining them into one shot?

The logistics alone are enough to justify having one effective product if we can make one. It should reduce the overall cost of administration and reduce time off from work.

The combination vaccines given by pediatricians have been very successful. They reduce the number of needles for kids and make it much easier for parents and the pediatricians administering them. The same principle should apply to adults, who sometimes are less brave about needles than kids are.

Historically, combined vaccines in general have worked as well as vaccines given alone, but there have been exceptions. We just have to see what the products look like.

Q: For now, the flu vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine are single products. If you get them separately, is it better to put some time between the two?

We don’t know. There are studies that probably won’t be out in time to decide in September. They are looking at whether you get an equivalent immune response if you give them together or apart.

For now, I would say the advantage of getting them together is if you do get side effects, you’ll only get them once – one day to suffer through them. Also, it’s one trip to the doctor.

The potential advantage of separating them is that is how we developed and tested the vaccines. If you do react to them, side effects could be milder, but it will be on two separate days.

I would recommend doing whatever works so that you get both vaccines in a timely manner.

I’m going to get my flu shot as soon as it’s available. If I’m due for a COVID booster at that time, I would probably do them together.

Q: Do you foresee a point in the future when the predominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 will be one of the components of a flu vaccine, like we did in the past with H1N1, etc?

It really remains to be seen, but it is very conceivable it could happen. The same companies that developed COVID-19 vaccines are working on flu vaccines.

Q: Any other advice for people concerned about getting immunized against both COVID-19 and influenza in the coming months?

There is no side effect of the vaccine that begins to approach the risk you face from either disease. It’s really one of the best things you can do to protect yourself is to get vaccinated.

In the case of flu, the vaccine is only modestly effective, but it still saves tens of thousands of lives each year. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is a much better vaccine and a deadlier disease.

Dr. Pavia consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on influenza testing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With first-time COVID-19 immunizations continuing and the plan to offer booster vaccines to most Americans starting next month, what are the considerations for getting COVID-19 and flu shots at the same time?

This news organization asked Andrew T. Pavia, MD, for his advice. He is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a fellow of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Q: With COVID-19 cases surging, is it a good idea to get the flu shot early this season?

Dr. Pavia: I don’t think there is a rush to do it in August, but it is a good idea to get a flu shot this season. The consequences of getting the flu while COVID is circulating are serious.

Q: What are the implications?

There are some we know and some we don’t know. If you develop flu-like symptoms, you’re going to have to get tested. You’re going to have to stay home quite a bit longer if you get a definitive (positive COVID-19) test than you would simply with flu symptoms. Also, you’re probably going to miss work when your workplace is very stressed or your children are stressed by having COVID circulating in schools.

The part we know less about are the implications of getting the flu and COVID together. There is some reason to believe if you get them together, the illness will be more severe. We are seeing that with RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) and parainfluenza and COVID coinfections in children. They appear to be quite severe.

But for flu, we just don’t have the data yet. That’s because there really was no cocirculation of COVID and influenza with the exception of parts of China for a brief part of February and March.

Q: Will the planned administration of booster COVID-19 shots this fall affect the number of people who get the flu vaccine or how it’s distributed?

It creates a lot of logistical challenges, particularly for hospitals and other places that need to vaccinate a large number of their employees for flu and that will need to give COVID boosters at about the same time period. It also creates logistical challenges for doctors’ offices.

But we don’t know of any reason why you can’t give the two shots together.

Q: Is it possible flu season will be more severe because we isolated and wore masks, etc., last winter? Any science behind that?

The more you study flu, the less you can predict, and I’ve been studying flu for a long time. There are reasons that might suggest a severe flu season – there has been limited immunity, and some people are not wearing masks effectively and they are gathering again. Those are things we believe protected us from influenza last season.

But we have not seen flu emerge yet. Normally we look to Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa during their winter – which is our summer – to get some idea of what is over the horizon for the Northern Hemisphere. Flu activity in Australia has been very modest this year.

That might mean flu may not show up for a while, but I would be loathe to make a prediction.

Q: What are the chances we’ll see a flu outbreak like we’re seeing with RSV, which is normally a winter illness?

The fact that we had a summer RSV surge just gives you an idea of how the normal epidemiology of viral infections has been disrupted. It means anything could happen with influenza. It could show up late summer or fall or wait until next spring.

We really don’t understand how those interactions work. When a new flu strain emerges, it often ignores the traditional behavior and shows up in the spring or fall. It happened in the 2009 pandemic, it happened in 1918.

The one thing I would safely predict about the next flu wave is that it will surprise us.

Q: Are you hopeful that combination vaccines in development from a number of companies, such as Moderna, Novavax, and Vivaldi, will be effective?

It is beginning to look like COVID will be with us for the foreseeable future – maybe as a seasonal virus or maybe as an ongoing pandemic. We are going to need to protect (ourselves) simultaneously against the flu and COVID. A single shot is a great way to do that – nobody wants two needles; nobody wants two trips to get vaccinated.

An effective combination vaccine would be a really great tool.

We have to wait to see what the science shows us, because they are quite different viruses. We won’t know if a combination vaccine works well and has acceptable side effects until we do those studies.

Q. Do you know at this point whether the side effects from two vaccines would be additive? Is there any way to predict that?

There is no way to predict. There are so many things that go into whether someone has side effects that we don’t understand. With fairly reactogenic vaccines like the mRNA vaccines, lots of people have no side effects whatsoever and others are really uncomfortable for 24 hours.

Flu is generally a better tolerated vaccine. There are still people who get muscle aches and very sore arms. I don’t think we can predict if getting two will be additive or just the same as getting one vaccine.

Q: Other than convenience and the benefit for people who are needle-phobic, are there any other advantages of combining them into one shot?

The logistics alone are enough to justify having one effective product if we can make one. It should reduce the overall cost of administration and reduce time off from work.

The combination vaccines given by pediatricians have been very successful. They reduce the number of needles for kids and make it much easier for parents and the pediatricians administering them. The same principle should apply to adults, who sometimes are less brave about needles than kids are.

Historically, combined vaccines in general have worked as well as vaccines given alone, but there have been exceptions. We just have to see what the products look like.

Q: For now, the flu vaccine and COVID-19 vaccine are single products. If you get them separately, is it better to put some time between the two?

We don’t know. There are studies that probably won’t be out in time to decide in September. They are looking at whether you get an equivalent immune response if you give them together or apart.

For now, I would say the advantage of getting them together is if you do get side effects, you’ll only get them once – one day to suffer through them. Also, it’s one trip to the doctor.

The potential advantage of separating them is that is how we developed and tested the vaccines. If you do react to them, side effects could be milder, but it will be on two separate days.

I would recommend doing whatever works so that you get both vaccines in a timely manner.

I’m going to get my flu shot as soon as it’s available. If I’m due for a COVID booster at that time, I would probably do them together.

Q: Do you foresee a point in the future when the predominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 will be one of the components of a flu vaccine, like we did in the past with H1N1, etc?

It really remains to be seen, but it is very conceivable it could happen. The same companies that developed COVID-19 vaccines are working on flu vaccines.

Q: Any other advice for people concerned about getting immunized against both COVID-19 and influenza in the coming months?

There is no side effect of the vaccine that begins to approach the risk you face from either disease. It’s really one of the best things you can do to protect yourself is to get vaccinated.

In the case of flu, the vaccine is only modestly effective, but it still saves tens of thousands of lives each year. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is a much better vaccine and a deadlier disease.

Dr. Pavia consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on influenza testing.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC launches new center to watch for future outbreaks

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is setting up a new hub to watch for early warning signs of future infectious outbreaks, the agency announced on Aug. 18.

Epidemiologists learn about emerging outbreaks by tracking information, and the quality of their analysis depends on their access to high-quality data. Gaps in existing systems became obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic as experts were challenged by the crisis.

The new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics will, in part, work like a meteorological office that tracks weather-related changes, only the center will track possible flareups in infectious disease.

The day after he took office, President Joe Biden pledged to modernize the country’s system for public health data. First funding for the initiative will come from the American Rescue Plan.

“We are excited to have the expertise and ability to model and forecast public health concerns and share information in real-time to activate governmental, private sector, and public actions in anticipation of threats both domestically and abroad,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a statement.

Devastating toll of COVID-19

Many world leaders are now responding to the destruction of the health crisis and are investing in new infrastructure. A July report from a G-20 panel calls for $75 billion in international financing for pandemic prevention and preparedness –twice as much as current spending levels.

Testifying in a congressional hearing, epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, voiced the importance of never being caught unprepared again.

“We were unprepared to manage the emergence and swift global spread of the novel coronavirus, and we were late to recognize when it reached our shores. Those delays set us on a worse trajectory than we might have otherwise faced,” she said.

Dr. Rivers will join the new center’s leadership team as associate director working alongside Marc Lipsitch, PhD, director for science.

“The new center will meet a longstanding need for a national focal point to analyze data and forecast the trajectory of pandemics with the express goal of informing and improving decisions with the best available evidence,” Dr. Lipsitch said in the CDC’s news release announcing the new center.

Experts will map what data sources are needed to assist disease modelers and public health emergency responders tracking emerging problems that they can share with decision-makers. They will expand tracking capability and data sharing using open-source software and application programming with existing and new data streams from the public health ecosystem and elsewhere.

Dylan George, PhD, who will be the center’s director for operations, said in the CDC news release that the center will provide critical information to communities so they can respond.

“Pandemics threaten our families and communities at speed and scale – our response needs to move at speed and scale, too,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is setting up a new hub to watch for early warning signs of future infectious outbreaks, the agency announced on Aug. 18.

Epidemiologists learn about emerging outbreaks by tracking information, and the quality of their analysis depends on their access to high-quality data. Gaps in existing systems became obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic as experts were challenged by the crisis.

The new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics will, in part, work like a meteorological office that tracks weather-related changes, only the center will track possible flareups in infectious disease.

The day after he took office, President Joe Biden pledged to modernize the country’s system for public health data. First funding for the initiative will come from the American Rescue Plan.

“We are excited to have the expertise and ability to model and forecast public health concerns and share information in real-time to activate governmental, private sector, and public actions in anticipation of threats both domestically and abroad,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a statement.

Devastating toll of COVID-19

Many world leaders are now responding to the destruction of the health crisis and are investing in new infrastructure. A July report from a G-20 panel calls for $75 billion in international financing for pandemic prevention and preparedness –twice as much as current spending levels.

Testifying in a congressional hearing, epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, voiced the importance of never being caught unprepared again.

“We were unprepared to manage the emergence and swift global spread of the novel coronavirus, and we were late to recognize when it reached our shores. Those delays set us on a worse trajectory than we might have otherwise faced,” she said.

Dr. Rivers will join the new center’s leadership team as associate director working alongside Marc Lipsitch, PhD, director for science.

“The new center will meet a longstanding need for a national focal point to analyze data and forecast the trajectory of pandemics with the express goal of informing and improving decisions with the best available evidence,” Dr. Lipsitch said in the CDC’s news release announcing the new center.

Experts will map what data sources are needed to assist disease modelers and public health emergency responders tracking emerging problems that they can share with decision-makers. They will expand tracking capability and data sharing using open-source software and application programming with existing and new data streams from the public health ecosystem and elsewhere.

Dylan George, PhD, who will be the center’s director for operations, said in the CDC news release that the center will provide critical information to communities so they can respond.

“Pandemics threaten our families and communities at speed and scale – our response needs to move at speed and scale, too,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is setting up a new hub to watch for early warning signs of future infectious outbreaks, the agency announced on Aug. 18.

Epidemiologists learn about emerging outbreaks by tracking information, and the quality of their analysis depends on their access to high-quality data. Gaps in existing systems became obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic as experts were challenged by the crisis.

The new Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics will, in part, work like a meteorological office that tracks weather-related changes, only the center will track possible flareups in infectious disease.

The day after he took office, President Joe Biden pledged to modernize the country’s system for public health data. First funding for the initiative will come from the American Rescue Plan.

“We are excited to have the expertise and ability to model and forecast public health concerns and share information in real-time to activate governmental, private sector, and public actions in anticipation of threats both domestically and abroad,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a statement.

Devastating toll of COVID-19

Many world leaders are now responding to the destruction of the health crisis and are investing in new infrastructure. A July report from a G-20 panel calls for $75 billion in international financing for pandemic prevention and preparedness –twice as much as current spending levels.

Testifying in a congressional hearing, epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers, PhD, from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, voiced the importance of never being caught unprepared again.

“We were unprepared to manage the emergence and swift global spread of the novel coronavirus, and we were late to recognize when it reached our shores. Those delays set us on a worse trajectory than we might have otherwise faced,” she said.

Dr. Rivers will join the new center’s leadership team as associate director working alongside Marc Lipsitch, PhD, director for science.

“The new center will meet a longstanding need for a national focal point to analyze data and forecast the trajectory of pandemics with the express goal of informing and improving decisions with the best available evidence,” Dr. Lipsitch said in the CDC’s news release announcing the new center.

Experts will map what data sources are needed to assist disease modelers and public health emergency responders tracking emerging problems that they can share with decision-makers. They will expand tracking capability and data sharing using open-source software and application programming with existing and new data streams from the public health ecosystem and elsewhere.

Dylan George, PhD, who will be the center’s director for operations, said in the CDC news release that the center will provide critical information to communities so they can respond.

“Pandemics threaten our families and communities at speed and scale – our response needs to move at speed and scale, too,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Cutaneous Chaetomium globosum Infection in a Vedolizumab-Treated Patient

To the Editor:

Broader availability and utilization of novel biologic treatments has heralded the emergence of unusual infections, including skin and soft tissue infections. These unusual infections may not be seen in clinical trials due to their overall rare incidence. In modern society, exposure to unusual pathogens can occur in locations far from their natural habitat.1 Tissue culture remains the gold standard, as histopathology and smears may not identify the organisms. Tissue culture of these less-common pathogens is challenging and may require multiple samples and specialized laboratory evaluations.2 In some cases, a skin biopsy with histopathologic examination is an efficient means to confirm or exclude a dermatologic manifestation of an inflammatory disease. This information can quickly change the course of treatment, especially for those on immunosuppressive medications.3 We report a case of unusual cutaneous infection with Chaetomium globosum in a patient concomitantly treated with vedolizumab, a gut-specific integrin inhibitor, alongside traditional immunosuppressive therapy.

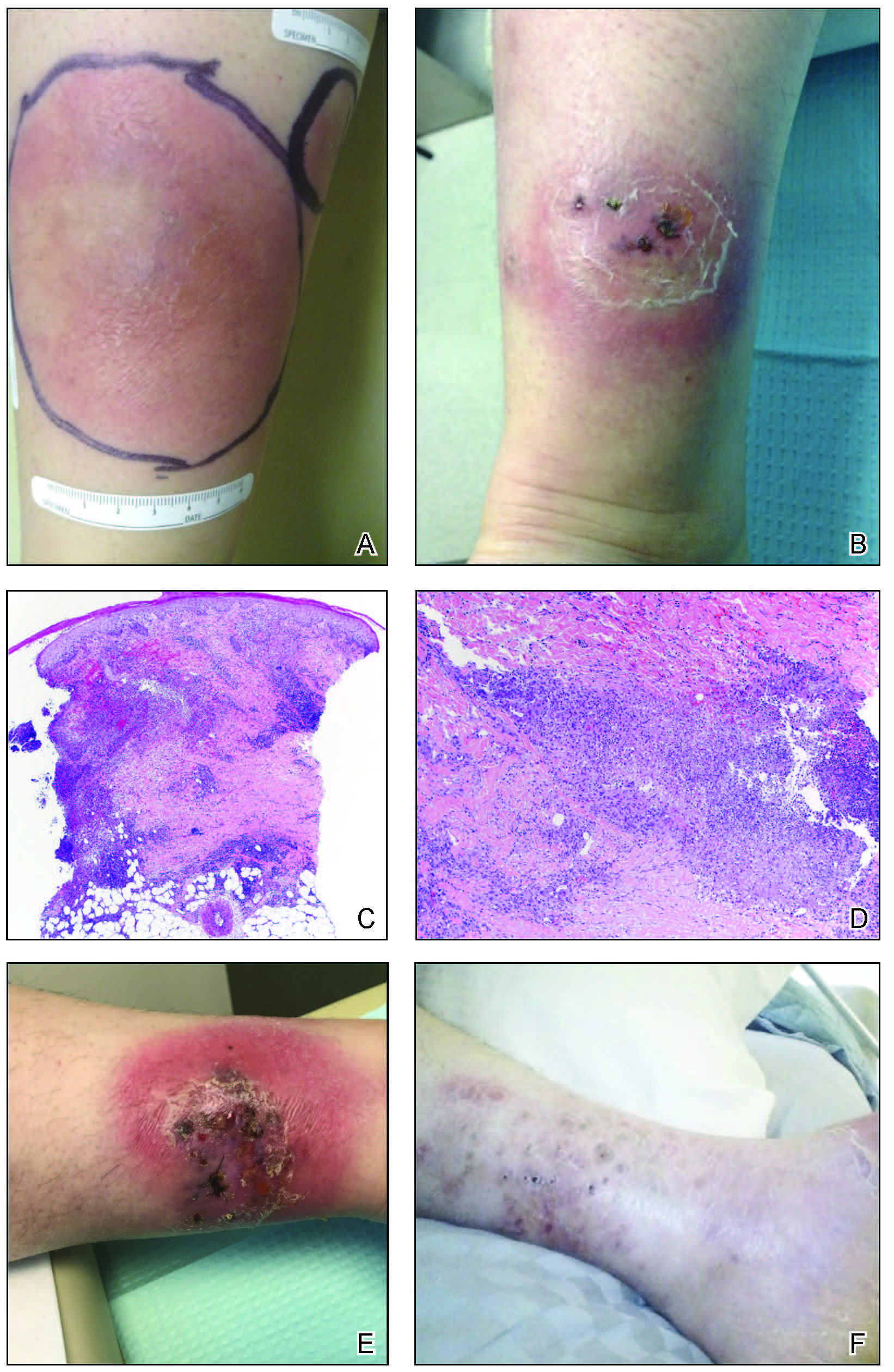

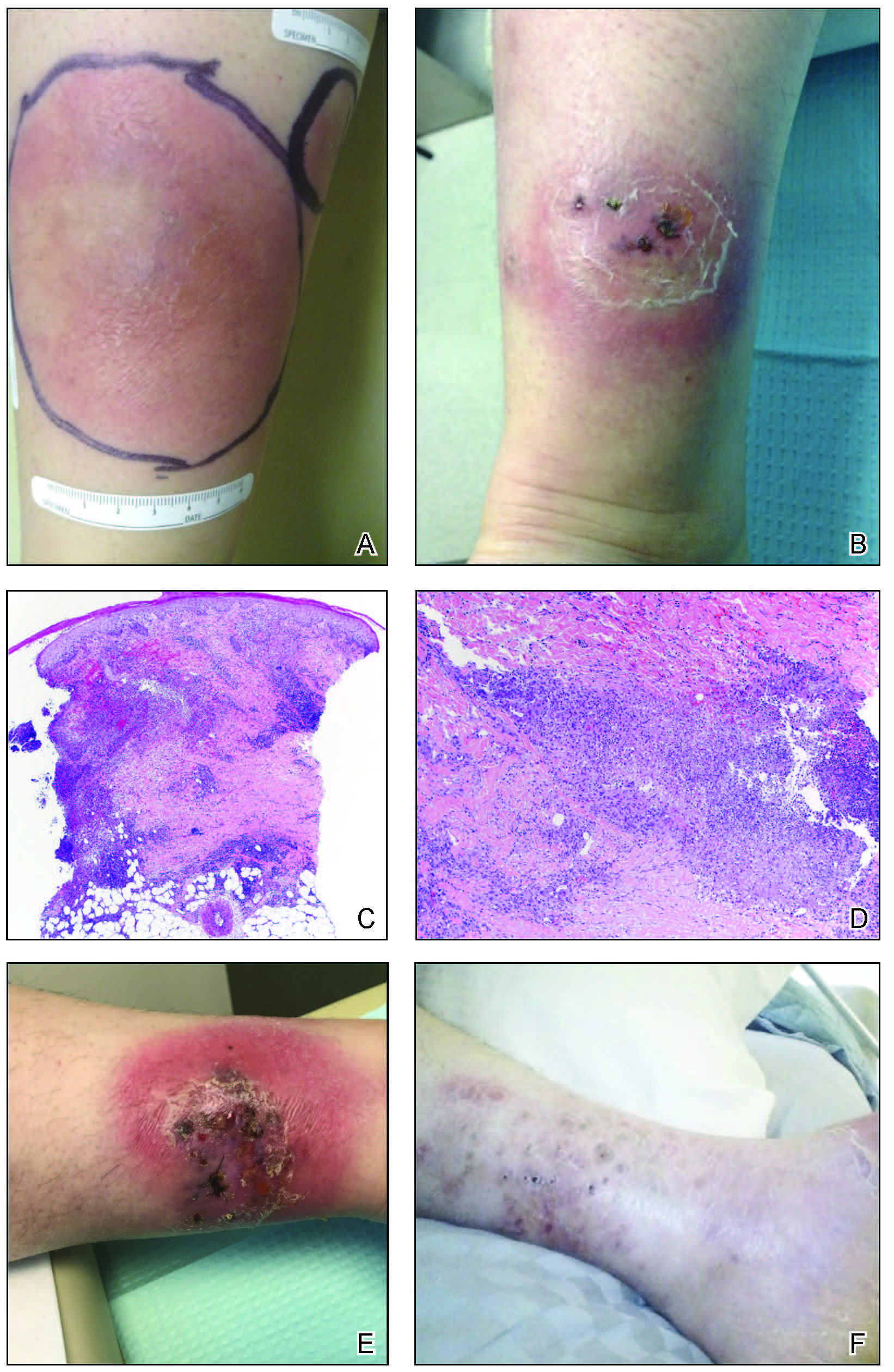

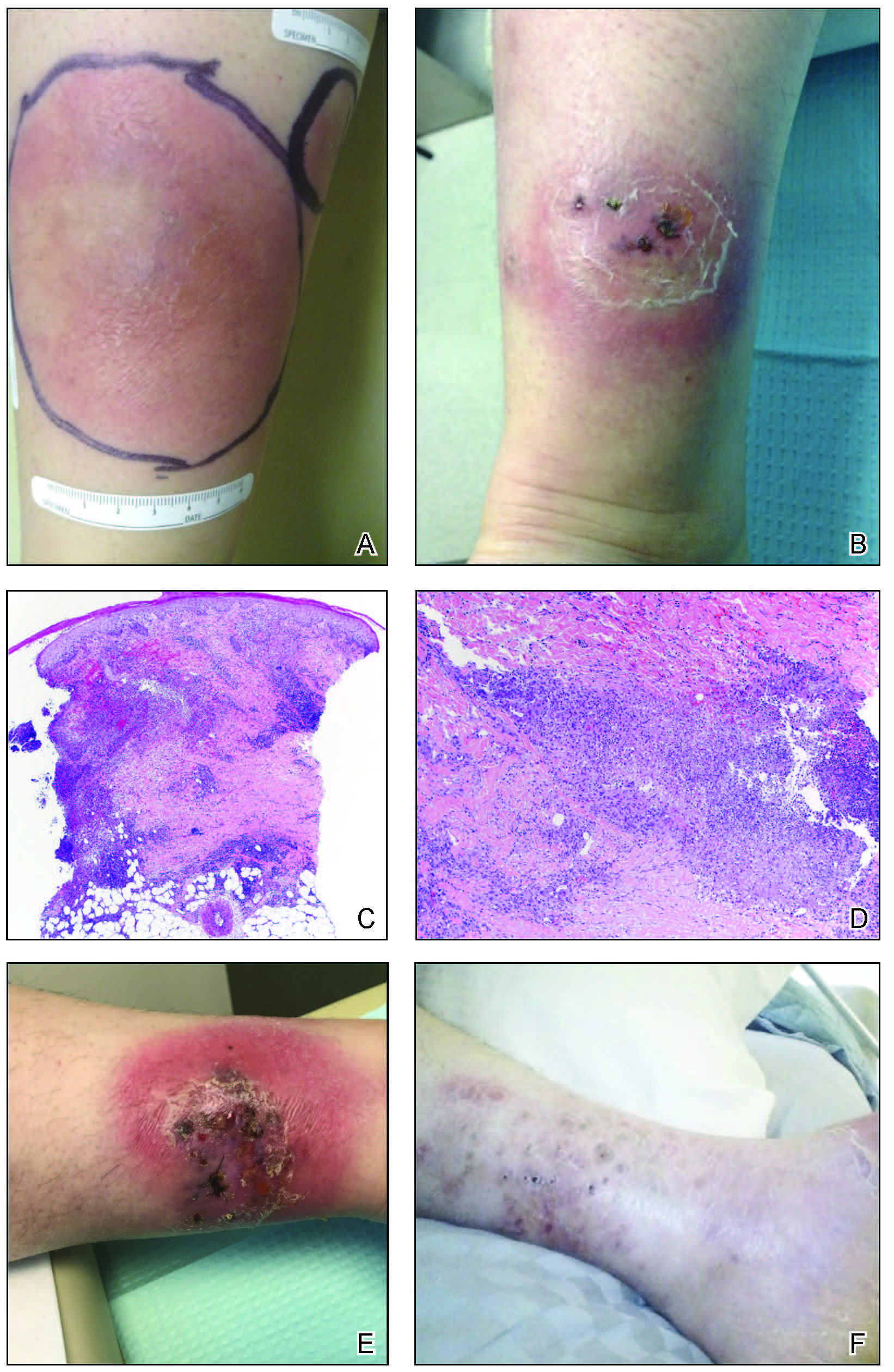

A 33-year-old woman with Crohn disease on vedolizumab and mercaptopurine was referred to the dermatology clinic with firm, tender, erythematous lesions on the legs of 1 month’s duration (Figure, A). She had a history of inflammatory bowel disease with perianal fistula, sacroiliitis, uveitis, guttate psoriasis, and erythema nodosum. She denied recent medication changes, foreign travel, swimming in freshwater or a hot tub, chills, fever, malaise, night sweats, and weight loss. Physical examination revealed several tender, indurated, erythematous plaques across the legs, ranging in size from 4 to 12 cm. The plaques had central hyperpigmentation, atrophy, and scant scale without ulceration, drainage, or pustules. The largest plaque demonstrated a well-defined area of central fluctuance. Prednisone (60 mg) with taper was initiated for presumed recurrence of erythema nodosum with close follow-up.

Five weeks later, most indurated plaques healed, leaving depressed scars; however, at 10 mg of prednisone she developed 2 additional nodules on the shin that, unlike earlier plaques, developed a central pustule and drained. The prednisone dose was increased to control the new areas and tapered thereafter to 20 mg daily. Despite the overall improvement, 2 plaques remained on the left side of the shin. Initially, erythema nodosum recurrence was considered, given the setting of inflammatory bowel disease and recent more classic presentation4; however, the disease progression and lack of response to standard treatment suggested an alternate pathology. Further history revealed that the patient had a pedicure 3 weeks prior to initial symptom onset. A swab was sent for routine bacterial culture at an outside clinic; no infectious agents were identified.

Three weeks later, the patient's condition had worsened again with increased edema, pain with standing, and more drainage (Figure, B). She did not report fevers or joint swelling. A punch biopsy was performed for tissue culture and histopathologic evaluation, which revealed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation and excluded erythema nodosum. Special stains for organisms were negative (Figure, C and D). Two weeks later, tissue culture began growing an unspecified mold. Mercaptopurine and prednisone were immediately discontinued. The patient remained on vedolizumab, started itraconazole (200 mg), and was referred to an infectious disease (ID) specialist. The sample was eventually identified as C globosum (Figure, E) at a specialized facility (University of Texas, San Antonio). Despite several weeks of itraconazole therapy, the patient developed edema surrounding the knee. Upon evaluation by orthopedics, the patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis in the left knee and ankle. The knee fluid was drained, and cultures were negative. At recommendation of the ID physician, the itraconazole dosage was doubled given the limited clinical response. After several weeks at the increased dosage, she began to experience slow improvement (Figure, F). Because Chaetomium species infections are rare and have limited response to many antifungal agents,5 no standard treatment protocol was available. Initial recommendations for treatment were for 1 year, based on the experience and expertise of the ID physician. Treatment with itraconazole was continued for 10 months, at which point the patient chose to discontinue therapy prior to her follow-up appointments. The patient had no evidence of infection recurrence 2 months after discontinuing therapy.

In the expanding landscape of targeted biologic therapies for chronic inflammatory disease, physicians of various specialties are increasingly encountering unanticipated cutaneous eruptions and infections. Chaetomium is a dematiaceous mold found primarily in soil, water, decaying plants, paper, or dung. Based on its habitat, populations at risk for infection with Chaetomium species include farmers (plant and animal husbandry), children who play on the ground, and people with inadequate foot protection.1,2Chaetomium globosum has been identified in indoor environments, such as moldy rugs and mattresses. In one report, it was cultured from the environmental air in a bone marrow transplant patient’s room after the patient presented with delayed infection.6 Although human infection is uncommon, clinical isolation of Chaetomium species has occurred mainly in superficial samples from the skin, hair, nails, eyes, and respiratory tract.1 It been reported as a causative agent of onychomycosis in several immunocompetent patients7,8 but rarely is a cause of deep-skin infection. Chaetomium is thought to cause superficial infections, as it uses extracellular keratinases1 to degrade protective keratin structures, such as human nails. Infections in the brain, blood, and lymph nodes also have been noted but are quite rare. Deep skin infections present as painful papules and nodules to nonhealing ulcers that develop into inflammatory granulomas on the extremities.3 Local edema and yellow-brown crust often is present and fevers have been reported. Hyphae may be identified in skin biopsy.8 We posit that our patient may have been exposed to Chaetomium during her pedicure, as recirculating baths in nail salons have been a reported site of other infectious organisms, such as atypical mycobacteria.9

Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. It targets the α4β7 integrin, a specific modulator of gut-trafficking lymphocytes. In vedolizumab’s clinical trial for Crohn disease, there was no increased incidence of life-threatening, severe infection.10,11 Often, new biologic treatments are used with known immunosuppressive medications. Mercaptopurine and prednisone are implicated in infections; however, recovery from the immune suppression usually is seen at 1 month after discontinuation.12 Our patient continued to worsen for several weeks and required increased dosing of itraconazole, despite stopping both prednisone and mercaptopurine. It opens the question as to whether vedolizumab played a role in the recalcitrant disease.

This case illustrates the importance of a high index of suspicion for unusual infections in the setting of biologic therapy. An infectious etiology of a cutaneous eruption in an immunosuppressed patient should always be included in the differential diagnosis and actively pursued early on; tissue culture may shorten the treatment course and decrease severity of the disease. Although a direct link between the mechanism of action of vedolizumab and cutaneous infection is not clear, given the rare incidence of this infection, a report of such a case is important to the practicing clinician.

- de Hoog GS, Ahmed SA, Najafzadeh MJ, et al. Phylogenetic findings suggest possible new habitat and routes of infection of human eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2229. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002229

- Zhang H, Ran Y, Li D, et al. Clavispora lusitaniae and Chaetomium atrobrunneum as rare agents of cutaneous infection. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:373-380. doi:10.1007/s11046-009-9266-9

- Schieffelin JS, Garcia-Diaz JB, Loss GE, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients: clinical presentation, pathology, and treatment. Transpl Infect Dis Off J Transplant Soc. 2014;16:270-278. doi:10.1111/tid.12197

- Farhi D, Cosnes J, Zizi N, et al. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel diseases: a cohort study of 2402 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87:281-293. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318187cc9c

- Guarro J, Soler L, Rinaldi MG. Pathogenicity and antifungal susceptibility of Chaetomium species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 1995;14:613-618.

- Teixeira ABA, Trabasso P, Moretti-Branchini ML, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum in an allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipient. Mycopathologia. 2003;156:309-312.

- Falcón CS, Falcón MDMS, Ceballos JD, et al. Onychomycosis by Chaetomium spp. Mycoses. 2009;52:77-79. doi:10.1111/j.14390507.2008.01519.x

- Kim DM, Lee MH, Suh MK, et al. Onychomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:232-236. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.2.232

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

- Luthra P, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1227-1236. doi:10.1111/apt.13215

- Colombel J-F, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839-851. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079

- Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, et al. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081-1085.

To the Editor:

Broader availability and utilization of novel biologic treatments has heralded the emergence of unusual infections, including skin and soft tissue infections. These unusual infections may not be seen in clinical trials due to their overall rare incidence. In modern society, exposure to unusual pathogens can occur in locations far from their natural habitat.1 Tissue culture remains the gold standard, as histopathology and smears may not identify the organisms. Tissue culture of these less-common pathogens is challenging and may require multiple samples and specialized laboratory evaluations.2 In some cases, a skin biopsy with histopathologic examination is an efficient means to confirm or exclude a dermatologic manifestation of an inflammatory disease. This information can quickly change the course of treatment, especially for those on immunosuppressive medications.3 We report a case of unusual cutaneous infection with Chaetomium globosum in a patient concomitantly treated with vedolizumab, a gut-specific integrin inhibitor, alongside traditional immunosuppressive therapy.

A 33-year-old woman with Crohn disease on vedolizumab and mercaptopurine was referred to the dermatology clinic with firm, tender, erythematous lesions on the legs of 1 month’s duration (Figure, A). She had a history of inflammatory bowel disease with perianal fistula, sacroiliitis, uveitis, guttate psoriasis, and erythema nodosum. She denied recent medication changes, foreign travel, swimming in freshwater or a hot tub, chills, fever, malaise, night sweats, and weight loss. Physical examination revealed several tender, indurated, erythematous plaques across the legs, ranging in size from 4 to 12 cm. The plaques had central hyperpigmentation, atrophy, and scant scale without ulceration, drainage, or pustules. The largest plaque demonstrated a well-defined area of central fluctuance. Prednisone (60 mg) with taper was initiated for presumed recurrence of erythema nodosum with close follow-up.

Five weeks later, most indurated plaques healed, leaving depressed scars; however, at 10 mg of prednisone she developed 2 additional nodules on the shin that, unlike earlier plaques, developed a central pustule and drained. The prednisone dose was increased to control the new areas and tapered thereafter to 20 mg daily. Despite the overall improvement, 2 plaques remained on the left side of the shin. Initially, erythema nodosum recurrence was considered, given the setting of inflammatory bowel disease and recent more classic presentation4; however, the disease progression and lack of response to standard treatment suggested an alternate pathology. Further history revealed that the patient had a pedicure 3 weeks prior to initial symptom onset. A swab was sent for routine bacterial culture at an outside clinic; no infectious agents were identified.

Three weeks later, the patient's condition had worsened again with increased edema, pain with standing, and more drainage (Figure, B). She did not report fevers or joint swelling. A punch biopsy was performed for tissue culture and histopathologic evaluation, which revealed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation and excluded erythema nodosum. Special stains for organisms were negative (Figure, C and D). Two weeks later, tissue culture began growing an unspecified mold. Mercaptopurine and prednisone were immediately discontinued. The patient remained on vedolizumab, started itraconazole (200 mg), and was referred to an infectious disease (ID) specialist. The sample was eventually identified as C globosum (Figure, E) at a specialized facility (University of Texas, San Antonio). Despite several weeks of itraconazole therapy, the patient developed edema surrounding the knee. Upon evaluation by orthopedics, the patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis in the left knee and ankle. The knee fluid was drained, and cultures were negative. At recommendation of the ID physician, the itraconazole dosage was doubled given the limited clinical response. After several weeks at the increased dosage, she began to experience slow improvement (Figure, F). Because Chaetomium species infections are rare and have limited response to many antifungal agents,5 no standard treatment protocol was available. Initial recommendations for treatment were for 1 year, based on the experience and expertise of the ID physician. Treatment with itraconazole was continued for 10 months, at which point the patient chose to discontinue therapy prior to her follow-up appointments. The patient had no evidence of infection recurrence 2 months after discontinuing therapy.

In the expanding landscape of targeted biologic therapies for chronic inflammatory disease, physicians of various specialties are increasingly encountering unanticipated cutaneous eruptions and infections. Chaetomium is a dematiaceous mold found primarily in soil, water, decaying plants, paper, or dung. Based on its habitat, populations at risk for infection with Chaetomium species include farmers (plant and animal husbandry), children who play on the ground, and people with inadequate foot protection.1,2Chaetomium globosum has been identified in indoor environments, such as moldy rugs and mattresses. In one report, it was cultured from the environmental air in a bone marrow transplant patient’s room after the patient presented with delayed infection.6 Although human infection is uncommon, clinical isolation of Chaetomium species has occurred mainly in superficial samples from the skin, hair, nails, eyes, and respiratory tract.1 It been reported as a causative agent of onychomycosis in several immunocompetent patients7,8 but rarely is a cause of deep-skin infection. Chaetomium is thought to cause superficial infections, as it uses extracellular keratinases1 to degrade protective keratin structures, such as human nails. Infections in the brain, blood, and lymph nodes also have been noted but are quite rare. Deep skin infections present as painful papules and nodules to nonhealing ulcers that develop into inflammatory granulomas on the extremities.3 Local edema and yellow-brown crust often is present and fevers have been reported. Hyphae may be identified in skin biopsy.8 We posit that our patient may have been exposed to Chaetomium during her pedicure, as recirculating baths in nail salons have been a reported site of other infectious organisms, such as atypical mycobacteria.9

Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. It targets the α4β7 integrin, a specific modulator of gut-trafficking lymphocytes. In vedolizumab’s clinical trial for Crohn disease, there was no increased incidence of life-threatening, severe infection.10,11 Often, new biologic treatments are used with known immunosuppressive medications. Mercaptopurine and prednisone are implicated in infections; however, recovery from the immune suppression usually is seen at 1 month after discontinuation.12 Our patient continued to worsen for several weeks and required increased dosing of itraconazole, despite stopping both prednisone and mercaptopurine. It opens the question as to whether vedolizumab played a role in the recalcitrant disease.

This case illustrates the importance of a high index of suspicion for unusual infections in the setting of biologic therapy. An infectious etiology of a cutaneous eruption in an immunosuppressed patient should always be included in the differential diagnosis and actively pursued early on; tissue culture may shorten the treatment course and decrease severity of the disease. Although a direct link between the mechanism of action of vedolizumab and cutaneous infection is not clear, given the rare incidence of this infection, a report of such a case is important to the practicing clinician.

To the Editor:

Broader availability and utilization of novel biologic treatments has heralded the emergence of unusual infections, including skin and soft tissue infections. These unusual infections may not be seen in clinical trials due to their overall rare incidence. In modern society, exposure to unusual pathogens can occur in locations far from their natural habitat.1 Tissue culture remains the gold standard, as histopathology and smears may not identify the organisms. Tissue culture of these less-common pathogens is challenging and may require multiple samples and specialized laboratory evaluations.2 In some cases, a skin biopsy with histopathologic examination is an efficient means to confirm or exclude a dermatologic manifestation of an inflammatory disease. This information can quickly change the course of treatment, especially for those on immunosuppressive medications.3 We report a case of unusual cutaneous infection with Chaetomium globosum in a patient concomitantly treated with vedolizumab, a gut-specific integrin inhibitor, alongside traditional immunosuppressive therapy.

A 33-year-old woman with Crohn disease on vedolizumab and mercaptopurine was referred to the dermatology clinic with firm, tender, erythematous lesions on the legs of 1 month’s duration (Figure, A). She had a history of inflammatory bowel disease with perianal fistula, sacroiliitis, uveitis, guttate psoriasis, and erythema nodosum. She denied recent medication changes, foreign travel, swimming in freshwater or a hot tub, chills, fever, malaise, night sweats, and weight loss. Physical examination revealed several tender, indurated, erythematous plaques across the legs, ranging in size from 4 to 12 cm. The plaques had central hyperpigmentation, atrophy, and scant scale without ulceration, drainage, or pustules. The largest plaque demonstrated a well-defined area of central fluctuance. Prednisone (60 mg) with taper was initiated for presumed recurrence of erythema nodosum with close follow-up.

Five weeks later, most indurated plaques healed, leaving depressed scars; however, at 10 mg of prednisone she developed 2 additional nodules on the shin that, unlike earlier plaques, developed a central pustule and drained. The prednisone dose was increased to control the new areas and tapered thereafter to 20 mg daily. Despite the overall improvement, 2 plaques remained on the left side of the shin. Initially, erythema nodosum recurrence was considered, given the setting of inflammatory bowel disease and recent more classic presentation4; however, the disease progression and lack of response to standard treatment suggested an alternate pathology. Further history revealed that the patient had a pedicure 3 weeks prior to initial symptom onset. A swab was sent for routine bacterial culture at an outside clinic; no infectious agents were identified.

Three weeks later, the patient's condition had worsened again with increased edema, pain with standing, and more drainage (Figure, B). She did not report fevers or joint swelling. A punch biopsy was performed for tissue culture and histopathologic evaluation, which revealed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation and excluded erythema nodosum. Special stains for organisms were negative (Figure, C and D). Two weeks later, tissue culture began growing an unspecified mold. Mercaptopurine and prednisone were immediately discontinued. The patient remained on vedolizumab, started itraconazole (200 mg), and was referred to an infectious disease (ID) specialist. The sample was eventually identified as C globosum (Figure, E) at a specialized facility (University of Texas, San Antonio). Despite several weeks of itraconazole therapy, the patient developed edema surrounding the knee. Upon evaluation by orthopedics, the patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis in the left knee and ankle. The knee fluid was drained, and cultures were negative. At recommendation of the ID physician, the itraconazole dosage was doubled given the limited clinical response. After several weeks at the increased dosage, she began to experience slow improvement (Figure, F). Because Chaetomium species infections are rare and have limited response to many antifungal agents,5 no standard treatment protocol was available. Initial recommendations for treatment were for 1 year, based on the experience and expertise of the ID physician. Treatment with itraconazole was continued for 10 months, at which point the patient chose to discontinue therapy prior to her follow-up appointments. The patient had no evidence of infection recurrence 2 months after discontinuing therapy.

In the expanding landscape of targeted biologic therapies for chronic inflammatory disease, physicians of various specialties are increasingly encountering unanticipated cutaneous eruptions and infections. Chaetomium is a dematiaceous mold found primarily in soil, water, decaying plants, paper, or dung. Based on its habitat, populations at risk for infection with Chaetomium species include farmers (plant and animal husbandry), children who play on the ground, and people with inadequate foot protection.1,2Chaetomium globosum has been identified in indoor environments, such as moldy rugs and mattresses. In one report, it was cultured from the environmental air in a bone marrow transplant patient’s room after the patient presented with delayed infection.6 Although human infection is uncommon, clinical isolation of Chaetomium species has occurred mainly in superficial samples from the skin, hair, nails, eyes, and respiratory tract.1 It been reported as a causative agent of onychomycosis in several immunocompetent patients7,8 but rarely is a cause of deep-skin infection. Chaetomium is thought to cause superficial infections, as it uses extracellular keratinases1 to degrade protective keratin structures, such as human nails. Infections in the brain, blood, and lymph nodes also have been noted but are quite rare. Deep skin infections present as painful papules and nodules to nonhealing ulcers that develop into inflammatory granulomas on the extremities.3 Local edema and yellow-brown crust often is present and fevers have been reported. Hyphae may be identified in skin biopsy.8 We posit that our patient may have been exposed to Chaetomium during her pedicure, as recirculating baths in nail salons have been a reported site of other infectious organisms, such as atypical mycobacteria.9

Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. It targets the α4β7 integrin, a specific modulator of gut-trafficking lymphocytes. In vedolizumab’s clinical trial for Crohn disease, there was no increased incidence of life-threatening, severe infection.10,11 Often, new biologic treatments are used with known immunosuppressive medications. Mercaptopurine and prednisone are implicated in infections; however, recovery from the immune suppression usually is seen at 1 month after discontinuation.12 Our patient continued to worsen for several weeks and required increased dosing of itraconazole, despite stopping both prednisone and mercaptopurine. It opens the question as to whether vedolizumab played a role in the recalcitrant disease.

This case illustrates the importance of a high index of suspicion for unusual infections in the setting of biologic therapy. An infectious etiology of a cutaneous eruption in an immunosuppressed patient should always be included in the differential diagnosis and actively pursued early on; tissue culture may shorten the treatment course and decrease severity of the disease. Although a direct link between the mechanism of action of vedolizumab and cutaneous infection is not clear, given the rare incidence of this infection, a report of such a case is important to the practicing clinician.

- de Hoog GS, Ahmed SA, Najafzadeh MJ, et al. Phylogenetic findings suggest possible new habitat and routes of infection of human eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2229. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002229

- Zhang H, Ran Y, Li D, et al. Clavispora lusitaniae and Chaetomium atrobrunneum as rare agents of cutaneous infection. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:373-380. doi:10.1007/s11046-009-9266-9

- Schieffelin JS, Garcia-Diaz JB, Loss GE, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients: clinical presentation, pathology, and treatment. Transpl Infect Dis Off J Transplant Soc. 2014;16:270-278. doi:10.1111/tid.12197

- Farhi D, Cosnes J, Zizi N, et al. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel diseases: a cohort study of 2402 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87:281-293. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318187cc9c

- Guarro J, Soler L, Rinaldi MG. Pathogenicity and antifungal susceptibility of Chaetomium species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 1995;14:613-618.

- Teixeira ABA, Trabasso P, Moretti-Branchini ML, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum in an allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipient. Mycopathologia. 2003;156:309-312.

- Falcón CS, Falcón MDMS, Ceballos JD, et al. Onychomycosis by Chaetomium spp. Mycoses. 2009;52:77-79. doi:10.1111/j.14390507.2008.01519.x

- Kim DM, Lee MH, Suh MK, et al. Onychomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:232-236. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.2.232

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

- Luthra P, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1227-1236. doi:10.1111/apt.13215

- Colombel J-F, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839-851. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079

- Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, et al. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081-1085.

- de Hoog GS, Ahmed SA, Najafzadeh MJ, et al. Phylogenetic findings suggest possible new habitat and routes of infection of human eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2229. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002229

- Zhang H, Ran Y, Li D, et al. Clavispora lusitaniae and Chaetomium atrobrunneum as rare agents of cutaneous infection. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:373-380. doi:10.1007/s11046-009-9266-9

- Schieffelin JS, Garcia-Diaz JB, Loss GE, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients: clinical presentation, pathology, and treatment. Transpl Infect Dis Off J Transplant Soc. 2014;16:270-278. doi:10.1111/tid.12197

- Farhi D, Cosnes J, Zizi N, et al. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel diseases: a cohort study of 2402 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87:281-293. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318187cc9c

- Guarro J, Soler L, Rinaldi MG. Pathogenicity and antifungal susceptibility of Chaetomium species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 1995;14:613-618.

- Teixeira ABA, Trabasso P, Moretti-Branchini ML, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum in an allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipient. Mycopathologia. 2003;156:309-312.

- Falcón CS, Falcón MDMS, Ceballos JD, et al. Onychomycosis by Chaetomium spp. Mycoses. 2009;52:77-79. doi:10.1111/j.14390507.2008.01519.x

- Kim DM, Lee MH, Suh MK, et al. Onychomycosis caused by Chaetomium globosum. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:232-236. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.2.232

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

- Luthra P, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1227-1236. doi:10.1111/apt.13215

- Colombel J-F, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839-851. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079

- Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, et al. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081-1085.

Practice Points

- Tissue culture remains the gold standard for deep fungal infections.

- Physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for alternate diagnoses when a disease progresses along an unexpected course.

- Biologic medications may have low-incidence side effects that emerge in postmarket use.

COVID-19 booster shots to start in September: Officials

at a press briefing August 18.

Those who received the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines would be eligible to get a booster shot 8 months after they received the second dose of those vaccines, officials said. Information on boosters for those who got the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine will be forthcoming.

“We anticipate a booster will [also] likely be needed,” said U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD. The J&J vaccine was not available in the U.S. until March, he said, and ‘’we expect more data on J&J in the coming weeks, so that plan is coming.”

The plan for boosters for the two mRNA vaccines is pending the FDA’s conducting of an independent review and authorizing the third dose of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, as well as an advisory committee of the CDC making the recommendation.

“We know that even highly effective vaccines become less effective over time,” Dr. Murthy said. “Having reviewed the most current data, it is now our clinical judgment that the time to lay out a plan for the COVID-19 boosters is now.”

Research released Aug. 18 shows waning effectiveness of the two mRNA vaccines.

At the briefing, Dr. Murthy and others continually reassured listeners that while effectiveness against infection declines, the vaccines continue to protect against severe infections, hospitalizations, and death.

“If you are fully vaccinated, you still have a high degree of protection against the worst outcomes,” Dr. Murthy said.

Data driving the plan

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, cited three research studies published Aug. 18 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that helped to drive the decision to recommend boosters.

Analysis of nursing home COVID-19 data from the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network showed a significant decline in the effectiveness of the full mRNA vaccine against lab-confirmed COVID-19 infection, from 74.7% before the Delta variant (March 1-May 9, 2021) to 53% when the Delta variant became predominant in the United States. The analysis during the Delta dominant period included 85,000 weekly reports from nearly 15,000 facilities.

Another study looked at more than 10 million New York adults who had been fully vaccinated with either the Moderna, Pfizer, or J&J vaccine by July 25. During the period from May 3 to July 25, overall, the age-adjusted vaccine effectiveness against infection decreased from 91.7% to 79.8%.

Vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization remains high, another study found. An analysis of 1,129 patients who had gotten two doses of an mRNA vaccine showed vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization after 24 weeks. It was 86% at weeks 2-12 and 84% at weeks 13-24.

Immunologic facts

Immunologic information also points to the need for a booster, said Anthony Fauci, MD, the chief medical advisor to the president and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Antibody levels decline over time,” he said, “and higher antibody levels are associated with higher efficacy of the vaccine. Higher levels of antibody may be needed to protect against Delta.”

A booster increased antibody levels by ‘’at least tenfold and possibly more,” he said. And higher levels of antibody may be required to protect against Delta. Taken together, he said, the data support the use of a booster to increase the overall level of protection.

Booster details

“We will make sure it is convenient and easy to get the booster shot,” said Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator. As with the previous immunization, he said, the booster will be free, and no one will be asked about immigration status.

The plan for booster shots is an attempt to stay ahead of the virus, officials stressed

Big picture

Not everyone agrees with the booster dose idea. At a World Health Organization briefing Aug. 18, WHO’s Chief Scientist Soumya Swaminathan, MD, an Indian pediatrician, said that the right thing to do right now ‘’is to wait for the science to tell us when boosters, which groups of people, and which vaccines need boosters.”

Like others, she also broached the ‘’moral and ethical argument of giving people third doses, when they’re already well protected and while the rest of the world is waiting for their primary immunization.”

Dr. Swaminathan does see a role for boosters to protect immunocompromised people but noted that ‘’that’s a small number of people.” Widespread boosters ‘’will only lead to more variants, to more escape variants, and perhaps we’re heading into more dire situations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

at a press briefing August 18.

Those who received the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines would be eligible to get a booster shot 8 months after they received the second dose of those vaccines, officials said. Information on boosters for those who got the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine will be forthcoming.

“We anticipate a booster will [also] likely be needed,” said U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD. The J&J vaccine was not available in the U.S. until March, he said, and ‘’we expect more data on J&J in the coming weeks, so that plan is coming.”

The plan for boosters for the two mRNA vaccines is pending the FDA’s conducting of an independent review and authorizing the third dose of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, as well as an advisory committee of the CDC making the recommendation.

“We know that even highly effective vaccines become less effective over time,” Dr. Murthy said. “Having reviewed the most current data, it is now our clinical judgment that the time to lay out a plan for the COVID-19 boosters is now.”

Research released Aug. 18 shows waning effectiveness of the two mRNA vaccines.

At the briefing, Dr. Murthy and others continually reassured listeners that while effectiveness against infection declines, the vaccines continue to protect against severe infections, hospitalizations, and death.

“If you are fully vaccinated, you still have a high degree of protection against the worst outcomes,” Dr. Murthy said.

Data driving the plan

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, cited three research studies published Aug. 18 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that helped to drive the decision to recommend boosters.

Analysis of nursing home COVID-19 data from the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network showed a significant decline in the effectiveness of the full mRNA vaccine against lab-confirmed COVID-19 infection, from 74.7% before the Delta variant (March 1-May 9, 2021) to 53% when the Delta variant became predominant in the United States. The analysis during the Delta dominant period included 85,000 weekly reports from nearly 15,000 facilities.

Another study looked at more than 10 million New York adults who had been fully vaccinated with either the Moderna, Pfizer, or J&J vaccine by July 25. During the period from May 3 to July 25, overall, the age-adjusted vaccine effectiveness against infection decreased from 91.7% to 79.8%.

Vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization remains high, another study found. An analysis of 1,129 patients who had gotten two doses of an mRNA vaccine showed vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization after 24 weeks. It was 86% at weeks 2-12 and 84% at weeks 13-24.

Immunologic facts

Immunologic information also points to the need for a booster, said Anthony Fauci, MD, the chief medical advisor to the president and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“Antibody levels decline over time,” he said, “and higher antibody levels are associated with higher efficacy of the vaccine. Higher levels of antibody may be needed to protect against Delta.”

A booster increased antibody levels by ‘’at least tenfold and possibly more,” he said. And higher levels of antibody may be required to protect against Delta. Taken together, he said, the data support the use of a booster to increase the overall level of protection.

Booster details