User login

HIV testing dips during pandemic raise transmission concerns

raising concerns of a subsequent increase in transmission by people unaware of their HIV-positive status.

“Testing strategies need to be ramped up to cover this decrease in testing while adapting to the continuing COVID-19 environment,” reported Deesha Patel, MPH, and colleagues with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of HIV prevention, Atlanta, in research presented at the annual meeting of the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

According to their data from the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation system, the number of CDC-funded HIV tests declined by more than 1 million in 2020 amid the COVID-19 restrictions, with 1,228,142 tests reported that year, compared with 2,301,669 tests in 2019, a reduction of 46.6%.

The number of persons who were newly diagnosed with HIV, based on the tests, declined by 29.7%, from 7,692 newly diagnosed in 2019 to 5,409 persons in 2020, the authors reported.

The reasons for the reduction in new HIV diagnoses in 2020 could be multifactorial, possibly reflecting not just the reduced rates of testing but also possibly lower rates of transmission because of the lockdowns and social distancing, Mr. Patel said in an interview.

“Both [of those] interpretations are plausible, and the reductions are likely due to a combination of reasons,” she said.

Of note, the percentage of tests that were positive did not show a decline and was in fact slightly higher in 2020 (0.4%), compared with 2019 (0.3%; rate ratio, 1.32). But the increase may reflect that those seeking testing during the pandemic were more likely to be symptomatic.

“It is plausible that the smaller pool of people getting tested represented those with a higher likelihood of receiving a positive HIV test, [for instance] having a recent exposure, exhibiting symptoms,” Mr. Patel explained. “Furthermore, it is possible that some health departments specifically focused outreach efforts to serve persons with increased potential for HIV acquisition, thus identifying a higher proportion of persons with HIV.”

The declines in testing are nevertheless of particular concern in light of recent pre-COVID data indicating that as many as 13% of people who were infected with HIV were unaware of their positive status, placing them at high risk of transmitting the virus.

And on a broader level, the declines could negatively affect the goal to eradicate HIV through the federal Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative, which aims to reduce new HIV infections in the United States by 90% by 2030 through the scaling up of key HIV prevention and treatment strategies, Mr. Patel noted.

“The first pillar of EHE is to diagnose all people with HIV as early as possible, and to accomplish that, there needs to be sufficient HIV testing,” Mr. Patel explained. “With fewer HIV tests being conducted, there are missed opportunities to identify persons with newly diagnosed HIV, which affects the entire continuum of care, [including] linkage to medical care, receiving antiretroviral treatment, getting and keeping viral suppression, and reducing transmission.”

At the local level: Adaptations allowed for continued testing

In a separate report presented at the meeting detailing the experiences at a more local level, Joseph Olsen, MPH, and colleagues with CrescentCare, New Orleans, described a similar reduction of HIV testing in 2020 of 49% in their system, compared with the previous year, down from 7,952 rapid HIV tests in 2019 to 4,034 in 2020.

However, through efforts to continue to provide services during the pandemic, the program was able to link 182 patients to HIV care in 2020, which was up from 172 in 2019.

In addition to offering the rapid HIV testing in conjunction with COVID-19 testing at their urgent care centers, the center adapted to the pandemic’s challenges with strategies including a new at-home testing program; providing testing at a hotel shelter for the homeless; and testing as part of walk-in testing with a syringe access component.

Mr. Olsen credited the swift program adaptations with maintaining testing during the time of crisis.

“Without [those] measures, it would have been a near-zero number of tests provided,” he said in an interview. “It would have been easy to blame the pandemic and not try to find innovations to deliver services, but I credit our incredibly motivated team for wanting to make sure every possible resource was available.”

But now there are signs of possible fallout from the testing reductions that did occur, Mr. Olsen said.

“We are already seeing the increase with other sexually transmitted infections [STIs], and I expect that we will see this with HIV as well,” he said.

In response, clinicians should use diligence in providing HIV testing, Mr. Olsen asserted.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that anyone having sex should get tested for HIV. It’s as easy as that!” he said.

“If they are getting tested for any other STI, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone is pregnant, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone has never had an HIV test before in their life – and I would add if they haven’t had an HIV test since March of 2020 – make sure an HIV panel is added/discussed,” he said. “Doing this for everyone also reduces stigma around testing. It’s not because any one person or group or risk behavior is being targeted, it is just good public health practice.”

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Patel noted that the findings and conclusions of her poster are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

raising concerns of a subsequent increase in transmission by people unaware of their HIV-positive status.

“Testing strategies need to be ramped up to cover this decrease in testing while adapting to the continuing COVID-19 environment,” reported Deesha Patel, MPH, and colleagues with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of HIV prevention, Atlanta, in research presented at the annual meeting of the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

According to their data from the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation system, the number of CDC-funded HIV tests declined by more than 1 million in 2020 amid the COVID-19 restrictions, with 1,228,142 tests reported that year, compared with 2,301,669 tests in 2019, a reduction of 46.6%.

The number of persons who were newly diagnosed with HIV, based on the tests, declined by 29.7%, from 7,692 newly diagnosed in 2019 to 5,409 persons in 2020, the authors reported.

The reasons for the reduction in new HIV diagnoses in 2020 could be multifactorial, possibly reflecting not just the reduced rates of testing but also possibly lower rates of transmission because of the lockdowns and social distancing, Mr. Patel said in an interview.

“Both [of those] interpretations are plausible, and the reductions are likely due to a combination of reasons,” she said.

Of note, the percentage of tests that were positive did not show a decline and was in fact slightly higher in 2020 (0.4%), compared with 2019 (0.3%; rate ratio, 1.32). But the increase may reflect that those seeking testing during the pandemic were more likely to be symptomatic.

“It is plausible that the smaller pool of people getting tested represented those with a higher likelihood of receiving a positive HIV test, [for instance] having a recent exposure, exhibiting symptoms,” Mr. Patel explained. “Furthermore, it is possible that some health departments specifically focused outreach efforts to serve persons with increased potential for HIV acquisition, thus identifying a higher proportion of persons with HIV.”

The declines in testing are nevertheless of particular concern in light of recent pre-COVID data indicating that as many as 13% of people who were infected with HIV were unaware of their positive status, placing them at high risk of transmitting the virus.

And on a broader level, the declines could negatively affect the goal to eradicate HIV through the federal Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative, which aims to reduce new HIV infections in the United States by 90% by 2030 through the scaling up of key HIV prevention and treatment strategies, Mr. Patel noted.

“The first pillar of EHE is to diagnose all people with HIV as early as possible, and to accomplish that, there needs to be sufficient HIV testing,” Mr. Patel explained. “With fewer HIV tests being conducted, there are missed opportunities to identify persons with newly diagnosed HIV, which affects the entire continuum of care, [including] linkage to medical care, receiving antiretroviral treatment, getting and keeping viral suppression, and reducing transmission.”

At the local level: Adaptations allowed for continued testing

In a separate report presented at the meeting detailing the experiences at a more local level, Joseph Olsen, MPH, and colleagues with CrescentCare, New Orleans, described a similar reduction of HIV testing in 2020 of 49% in their system, compared with the previous year, down from 7,952 rapid HIV tests in 2019 to 4,034 in 2020.

However, through efforts to continue to provide services during the pandemic, the program was able to link 182 patients to HIV care in 2020, which was up from 172 in 2019.

In addition to offering the rapid HIV testing in conjunction with COVID-19 testing at their urgent care centers, the center adapted to the pandemic’s challenges with strategies including a new at-home testing program; providing testing at a hotel shelter for the homeless; and testing as part of walk-in testing with a syringe access component.

Mr. Olsen credited the swift program adaptations with maintaining testing during the time of crisis.

“Without [those] measures, it would have been a near-zero number of tests provided,” he said in an interview. “It would have been easy to blame the pandemic and not try to find innovations to deliver services, but I credit our incredibly motivated team for wanting to make sure every possible resource was available.”

But now there are signs of possible fallout from the testing reductions that did occur, Mr. Olsen said.

“We are already seeing the increase with other sexually transmitted infections [STIs], and I expect that we will see this with HIV as well,” he said.

In response, clinicians should use diligence in providing HIV testing, Mr. Olsen asserted.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that anyone having sex should get tested for HIV. It’s as easy as that!” he said.

“If they are getting tested for any other STI, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone is pregnant, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone has never had an HIV test before in their life – and I would add if they haven’t had an HIV test since March of 2020 – make sure an HIV panel is added/discussed,” he said. “Doing this for everyone also reduces stigma around testing. It’s not because any one person or group or risk behavior is being targeted, it is just good public health practice.”

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Patel noted that the findings and conclusions of her poster are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

raising concerns of a subsequent increase in transmission by people unaware of their HIV-positive status.

“Testing strategies need to be ramped up to cover this decrease in testing while adapting to the continuing COVID-19 environment,” reported Deesha Patel, MPH, and colleagues with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of HIV prevention, Atlanta, in research presented at the annual meeting of the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS.

According to their data from the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation system, the number of CDC-funded HIV tests declined by more than 1 million in 2020 amid the COVID-19 restrictions, with 1,228,142 tests reported that year, compared with 2,301,669 tests in 2019, a reduction of 46.6%.

The number of persons who were newly diagnosed with HIV, based on the tests, declined by 29.7%, from 7,692 newly diagnosed in 2019 to 5,409 persons in 2020, the authors reported.

The reasons for the reduction in new HIV diagnoses in 2020 could be multifactorial, possibly reflecting not just the reduced rates of testing but also possibly lower rates of transmission because of the lockdowns and social distancing, Mr. Patel said in an interview.

“Both [of those] interpretations are plausible, and the reductions are likely due to a combination of reasons,” she said.

Of note, the percentage of tests that were positive did not show a decline and was in fact slightly higher in 2020 (0.4%), compared with 2019 (0.3%; rate ratio, 1.32). But the increase may reflect that those seeking testing during the pandemic were more likely to be symptomatic.

“It is plausible that the smaller pool of people getting tested represented those with a higher likelihood of receiving a positive HIV test, [for instance] having a recent exposure, exhibiting symptoms,” Mr. Patel explained. “Furthermore, it is possible that some health departments specifically focused outreach efforts to serve persons with increased potential for HIV acquisition, thus identifying a higher proportion of persons with HIV.”

The declines in testing are nevertheless of particular concern in light of recent pre-COVID data indicating that as many as 13% of people who were infected with HIV were unaware of their positive status, placing them at high risk of transmitting the virus.

And on a broader level, the declines could negatively affect the goal to eradicate HIV through the federal Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative, which aims to reduce new HIV infections in the United States by 90% by 2030 through the scaling up of key HIV prevention and treatment strategies, Mr. Patel noted.

“The first pillar of EHE is to diagnose all people with HIV as early as possible, and to accomplish that, there needs to be sufficient HIV testing,” Mr. Patel explained. “With fewer HIV tests being conducted, there are missed opportunities to identify persons with newly diagnosed HIV, which affects the entire continuum of care, [including] linkage to medical care, receiving antiretroviral treatment, getting and keeping viral suppression, and reducing transmission.”

At the local level: Adaptations allowed for continued testing

In a separate report presented at the meeting detailing the experiences at a more local level, Joseph Olsen, MPH, and colleagues with CrescentCare, New Orleans, described a similar reduction of HIV testing in 2020 of 49% in their system, compared with the previous year, down from 7,952 rapid HIV tests in 2019 to 4,034 in 2020.

However, through efforts to continue to provide services during the pandemic, the program was able to link 182 patients to HIV care in 2020, which was up from 172 in 2019.

In addition to offering the rapid HIV testing in conjunction with COVID-19 testing at their urgent care centers, the center adapted to the pandemic’s challenges with strategies including a new at-home testing program; providing testing at a hotel shelter for the homeless; and testing as part of walk-in testing with a syringe access component.

Mr. Olsen credited the swift program adaptations with maintaining testing during the time of crisis.

“Without [those] measures, it would have been a near-zero number of tests provided,” he said in an interview. “It would have been easy to blame the pandemic and not try to find innovations to deliver services, but I credit our incredibly motivated team for wanting to make sure every possible resource was available.”

But now there are signs of possible fallout from the testing reductions that did occur, Mr. Olsen said.

“We are already seeing the increase with other sexually transmitted infections [STIs], and I expect that we will see this with HIV as well,” he said.

In response, clinicians should use diligence in providing HIV testing, Mr. Olsen asserted.

“The take-home message for clinicians is that anyone having sex should get tested for HIV. It’s as easy as that!” he said.

“If they are getting tested for any other STI, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone is pregnant, make sure an HIV panel is added and discussed. If someone has never had an HIV test before in their life – and I would add if they haven’t had an HIV test since March of 2020 – make sure an HIV panel is added/discussed,” he said. “Doing this for everyone also reduces stigma around testing. It’s not because any one person or group or risk behavior is being targeted, it is just good public health practice.”

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Patel noted that the findings and conclusions of her poster are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Inadequate routine diabetes screening common in HIV

, research shows.

“Despite known risk in this patient population, most patients were not up to date with routine preventative screenings,” report Maya Hardman, PharmD, and colleagues with Southwest CARE Center, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in research presented at the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Routine preventative screenings can help identify chronic complications of diabetes early, if performed at the recommended intervals,” they write.

People with HIV are known to be at an increased risk of diabetes and the long-term complications of the disease, making the need for routine screening to prevent such complications all the more pressing due to their higher-risk health status.

Among the key routine diabetes care quality measures recommended by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) for people with HIV are testing for A1c once every 3 months, foot and eye exams every 12 months, urine albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) screenings every 12 months, and two controlled blood pressure readings every 12 months.

To investigate the rates of adherence to the HEDIS screening recommendations and identify predictors of poor compliance among people with HIV, Dr. Hardman and her colleagues evaluated data on 121 adult patients at the Southwest CARE Center who had been diagnosed with diabetes and HIV and were treated between 2019 and 2020.

The patients had a mean age of 57.5, and 9% were female. Their mean duration of being HIV positive was 19.8 years, and they had an intermediate Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score of 17.08%.

Despite their known diagnoses of having diabetes, as many as 93.4% were found not to be up to date on their routine preventive screenings.

Of the 121 patients, only 30 had received the recommended A1c screenings, 37 had the recommended UACR screenings, and just 18 had received the recommended foot exam screenings.

Only blood pressure screenings, reported in 90 of the 121 patients, were up to date in the majority of patients in the group.

In looking at factors associated with compliance with A1c screening, only age (OR, 0.95; P = .04) was a significant predictor.

The authors pointed out that routine screenings for diabetes complications are relatively easy to implement.

“Screening for these chronic complications is minimally invasive and can be provided by individuals trained in diabetes management during routine clinic appointments.”

The team’s ongoing research is evaluating the potential benefits of clinical pharmacy services in assisting with the screenings for patients with HIV.

Research underscoring the increased risk and poorer treatment outcomes of diabetes in people with HIV include a study comparing 337 people with HIV in 2005 with a cohort of 338 participants in 2015.

The study showed the prevalence of type 2 diabetes had increased to 15.1% in 2015 from 6.8% 10 years earlier, for a relative risk of 2.4 compared with the general population.

“The alarmingly high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in HIV requires improved screening, targeted to older patients and those with a longer duration of exposure to antiretrovirals,” the authors wrote.

“Effective diabetes prevention and management strategies are needed urgently to reduce this risk; such interventions should target both conventional risk factors, such as abdominal obesity and HIV-specific risk factors such as weight gain following initiation of antiretrovirals.”

Of note, the 2015 cohort was significantly older and had higher BMI and higher hypertension than the 2005 cohort.

First author Alastair Duncan, PhD, principal dietitian at Guy’s & St. Thomas’ Hospital and lecturer, King’s College London, noted that since that 2015 study was published, concerns particularly with weight gain in the HIV population have only increased.

“Weight gain appears to be more of an issue [now],” he told this news organization in an interview.

“As in the general population, people living with HIV experienced significant weight gain during COVID-related lockdowns. Added to the high number of people living with HIV being treated with integrase inhibitors, weight gain remains a challenge.”

Meanwhile, “there are not enough studies comparing people living with HIV with the general population,” Dr. Duncan added. “We need to conduct studies where participants are matched.”

Sudipa Sarkar, MD, who co-authored a report on the issue of diabetes and HIV this year but was not involved in the study presented at USCHA, noted that the setting of care could play an important role in the quality of screening for diabetes that people with HIV receive.

“It may depend on factors such as whether a patient is being followed regularly by an HIV care provider and the larger health care system that the patient is in,” Dr. Sarkar, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, told this news organization.

“For example, one might find differences between a patient being seen in a managed care group versus not.”

The issue of how the strikingly high rates of inadequate screening in the current study compare with routine screening in the general diabetes population “is a good question and warrants more research,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Sarkar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, research shows.

“Despite known risk in this patient population, most patients were not up to date with routine preventative screenings,” report Maya Hardman, PharmD, and colleagues with Southwest CARE Center, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in research presented at the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Routine preventative screenings can help identify chronic complications of diabetes early, if performed at the recommended intervals,” they write.

People with HIV are known to be at an increased risk of diabetes and the long-term complications of the disease, making the need for routine screening to prevent such complications all the more pressing due to their higher-risk health status.

Among the key routine diabetes care quality measures recommended by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) for people with HIV are testing for A1c once every 3 months, foot and eye exams every 12 months, urine albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) screenings every 12 months, and two controlled blood pressure readings every 12 months.

To investigate the rates of adherence to the HEDIS screening recommendations and identify predictors of poor compliance among people with HIV, Dr. Hardman and her colleagues evaluated data on 121 adult patients at the Southwest CARE Center who had been diagnosed with diabetes and HIV and were treated between 2019 and 2020.

The patients had a mean age of 57.5, and 9% were female. Their mean duration of being HIV positive was 19.8 years, and they had an intermediate Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score of 17.08%.

Despite their known diagnoses of having diabetes, as many as 93.4% were found not to be up to date on their routine preventive screenings.

Of the 121 patients, only 30 had received the recommended A1c screenings, 37 had the recommended UACR screenings, and just 18 had received the recommended foot exam screenings.

Only blood pressure screenings, reported in 90 of the 121 patients, were up to date in the majority of patients in the group.

In looking at factors associated with compliance with A1c screening, only age (OR, 0.95; P = .04) was a significant predictor.

The authors pointed out that routine screenings for diabetes complications are relatively easy to implement.

“Screening for these chronic complications is minimally invasive and can be provided by individuals trained in diabetes management during routine clinic appointments.”

The team’s ongoing research is evaluating the potential benefits of clinical pharmacy services in assisting with the screenings for patients with HIV.

Research underscoring the increased risk and poorer treatment outcomes of diabetes in people with HIV include a study comparing 337 people with HIV in 2005 with a cohort of 338 participants in 2015.

The study showed the prevalence of type 2 diabetes had increased to 15.1% in 2015 from 6.8% 10 years earlier, for a relative risk of 2.4 compared with the general population.

“The alarmingly high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in HIV requires improved screening, targeted to older patients and those with a longer duration of exposure to antiretrovirals,” the authors wrote.

“Effective diabetes prevention and management strategies are needed urgently to reduce this risk; such interventions should target both conventional risk factors, such as abdominal obesity and HIV-specific risk factors such as weight gain following initiation of antiretrovirals.”

Of note, the 2015 cohort was significantly older and had higher BMI and higher hypertension than the 2005 cohort.

First author Alastair Duncan, PhD, principal dietitian at Guy’s & St. Thomas’ Hospital and lecturer, King’s College London, noted that since that 2015 study was published, concerns particularly with weight gain in the HIV population have only increased.

“Weight gain appears to be more of an issue [now],” he told this news organization in an interview.

“As in the general population, people living with HIV experienced significant weight gain during COVID-related lockdowns. Added to the high number of people living with HIV being treated with integrase inhibitors, weight gain remains a challenge.”

Meanwhile, “there are not enough studies comparing people living with HIV with the general population,” Dr. Duncan added. “We need to conduct studies where participants are matched.”

Sudipa Sarkar, MD, who co-authored a report on the issue of diabetes and HIV this year but was not involved in the study presented at USCHA, noted that the setting of care could play an important role in the quality of screening for diabetes that people with HIV receive.

“It may depend on factors such as whether a patient is being followed regularly by an HIV care provider and the larger health care system that the patient is in,” Dr. Sarkar, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, told this news organization.

“For example, one might find differences between a patient being seen in a managed care group versus not.”

The issue of how the strikingly high rates of inadequate screening in the current study compare with routine screening in the general diabetes population “is a good question and warrants more research,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Sarkar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, research shows.

“Despite known risk in this patient population, most patients were not up to date with routine preventative screenings,” report Maya Hardman, PharmD, and colleagues with Southwest CARE Center, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in research presented at the United States Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Routine preventative screenings can help identify chronic complications of diabetes early, if performed at the recommended intervals,” they write.

People with HIV are known to be at an increased risk of diabetes and the long-term complications of the disease, making the need for routine screening to prevent such complications all the more pressing due to their higher-risk health status.

Among the key routine diabetes care quality measures recommended by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) for people with HIV are testing for A1c once every 3 months, foot and eye exams every 12 months, urine albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) screenings every 12 months, and two controlled blood pressure readings every 12 months.

To investigate the rates of adherence to the HEDIS screening recommendations and identify predictors of poor compliance among people with HIV, Dr. Hardman and her colleagues evaluated data on 121 adult patients at the Southwest CARE Center who had been diagnosed with diabetes and HIV and were treated between 2019 and 2020.

The patients had a mean age of 57.5, and 9% were female. Their mean duration of being HIV positive was 19.8 years, and they had an intermediate Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score of 17.08%.

Despite their known diagnoses of having diabetes, as many as 93.4% were found not to be up to date on their routine preventive screenings.

Of the 121 patients, only 30 had received the recommended A1c screenings, 37 had the recommended UACR screenings, and just 18 had received the recommended foot exam screenings.

Only blood pressure screenings, reported in 90 of the 121 patients, were up to date in the majority of patients in the group.

In looking at factors associated with compliance with A1c screening, only age (OR, 0.95; P = .04) was a significant predictor.

The authors pointed out that routine screenings for diabetes complications are relatively easy to implement.

“Screening for these chronic complications is minimally invasive and can be provided by individuals trained in diabetes management during routine clinic appointments.”

The team’s ongoing research is evaluating the potential benefits of clinical pharmacy services in assisting with the screenings for patients with HIV.

Research underscoring the increased risk and poorer treatment outcomes of diabetes in people with HIV include a study comparing 337 people with HIV in 2005 with a cohort of 338 participants in 2015.

The study showed the prevalence of type 2 diabetes had increased to 15.1% in 2015 from 6.8% 10 years earlier, for a relative risk of 2.4 compared with the general population.

“The alarmingly high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in HIV requires improved screening, targeted to older patients and those with a longer duration of exposure to antiretrovirals,” the authors wrote.

“Effective diabetes prevention and management strategies are needed urgently to reduce this risk; such interventions should target both conventional risk factors, such as abdominal obesity and HIV-specific risk factors such as weight gain following initiation of antiretrovirals.”

Of note, the 2015 cohort was significantly older and had higher BMI and higher hypertension than the 2005 cohort.

First author Alastair Duncan, PhD, principal dietitian at Guy’s & St. Thomas’ Hospital and lecturer, King’s College London, noted that since that 2015 study was published, concerns particularly with weight gain in the HIV population have only increased.

“Weight gain appears to be more of an issue [now],” he told this news organization in an interview.

“As in the general population, people living with HIV experienced significant weight gain during COVID-related lockdowns. Added to the high number of people living with HIV being treated with integrase inhibitors, weight gain remains a challenge.”

Meanwhile, “there are not enough studies comparing people living with HIV with the general population,” Dr. Duncan added. “We need to conduct studies where participants are matched.”

Sudipa Sarkar, MD, who co-authored a report on the issue of diabetes and HIV this year but was not involved in the study presented at USCHA, noted that the setting of care could play an important role in the quality of screening for diabetes that people with HIV receive.

“It may depend on factors such as whether a patient is being followed regularly by an HIV care provider and the larger health care system that the patient is in,” Dr. Sarkar, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, told this news organization.

“For example, one might find differences between a patient being seen in a managed care group versus not.”

The issue of how the strikingly high rates of inadequate screening in the current study compare with routine screening in the general diabetes population “is a good question and warrants more research,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Sarkar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 asymptomatic infection rate remains high

Based on data from a meta-analysis of 95 studies that included nearly 30,000,000 individuals, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic COVID-19 infections was 0.25% in the tested population and 40.5% among confirmed cases.

, wrote Qiuyue Ma, PhD, and colleagues of Peking University, Beijing.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open the researchers identified 44 cross-sectional studies, 41 cohort studies, seven case series, and three case series on transmission studies. A total of 74 studies were conducted in developed countries, including those in Europe, North America, and Asia. Approximately one-third (37) of the studies were conducted among health care workers or in-hospital patients, 17 among nursing home staff or residents, and 14 among community residents. In addition, 13 studies involved pregnant women, eight involved air or cruise ship travelers, and six involved close contacts of individuals with confirmed infections.

The meta-analysis included 29,776,306 tested individuals; 11,516 of them had asymptomatic infections.

Overall, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the tested population was 0.25%. In an analysis of different study populations, the percentage was higher in nursing home residents or staff (4.52%), air or cruise ship travelers (2.02%), and pregnant women (2.34%), compared against the pooled percentage.

The pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the confirmed population was 40.50%, and this percentage was higher in pregnant women (54.11%), air or cruise ship travelers (52.91%), and nursing home residents or staff (47.53%).

The pooled percentage in the tested population was higher than the overall percentage when the mean age of the study population was 60 years or older (3.69%). By contrast, in the confirmed population, the pooled percentage was higher than the overall percentage when the study population was younger than 20 years (60.2%) or aged 20 to 39 years (49.5%).

The researchers noted in their discussion that the varying percentage of asymptomatic individuals according to community prevalence might impact the heterogeneity of the included studies. They also noted the high number of studies conducted in nursing home populations, groups in which asymptomatic individuals were more likely to be tested.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for missed studies that were not published at the time of the meta-analysis, as well as the exclusion of studies written in Chinese, the researchers noted. Other limitations included lack of follow-up on presymptomatic and covert infections, and the focus on specific populations, factors that may limit the degree to which the results can be generalized.

However, the results highlight the need to screen for asymptomatic infections, especially in countries where COVID-19 has been better controlled, the researchers said. Management strategies for asymptomatic infections, when identified, should include isolation and contact tracing similar to strategies used with confirmed cases, they added.

More testing needed to catch cases early

“During the initial phase of [the] COVID-19 pandemic, testing was not widely available in the United States or the rest of the world,” Setu Patolia, MD, of Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Missouri, said in an interview. Much of the world still lacks access to COVID-19 testing, and early in the pandemic only severely symptomatic patients were tested, he said. “With new variants, particularly the Omicron variant, which may have mild or minimally symptomatic disease, asymptomatic carriers play an important role in propagation of the pandemic,” he explained. “It is important to know the asymptomatic carrier rate among the general population for the future control of [the] pandemic,” he added.

Dr. Patolia said he was surprised by the study finding that one in 400 people in the general population could be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19.

“Also, nursing home patients are more at risk of complications of COVID, and I expected that they would have a higher rate of symptomatic disease as compared to [the] general population,” said Dr. Patolia. He was also surprised by the high rate of asymptomatic infections in travelers.

“Physicians should be more aware about the asymptomatic carrier rate, particularly in travelers and nursing home patients,” he noted. “Travelers carry high risk of transferring infection from one region to another region of the world, and physicians should advise them to get tested despite the absence of symptoms,” Dr. Patolia emphasized. “Similarly, once any nursing home patient has been diagnosed with COVID-19, physicians should be more careful with the rest of the nursing home patients and test them despite the absence of the symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Patolia also recommended that pregnant women wear masks to help prevent disease transmission when visiting a doctor’s office or labor unit.

Looking ahead, there is a need for cheaper at-home testing kits so that all vulnerable populations can be tested fast and frequently, Dr. Patolia said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Patolia has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Based on data from a meta-analysis of 95 studies that included nearly 30,000,000 individuals, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic COVID-19 infections was 0.25% in the tested population and 40.5% among confirmed cases.

, wrote Qiuyue Ma, PhD, and colleagues of Peking University, Beijing.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open the researchers identified 44 cross-sectional studies, 41 cohort studies, seven case series, and three case series on transmission studies. A total of 74 studies were conducted in developed countries, including those in Europe, North America, and Asia. Approximately one-third (37) of the studies were conducted among health care workers or in-hospital patients, 17 among nursing home staff or residents, and 14 among community residents. In addition, 13 studies involved pregnant women, eight involved air or cruise ship travelers, and six involved close contacts of individuals with confirmed infections.

The meta-analysis included 29,776,306 tested individuals; 11,516 of them had asymptomatic infections.

Overall, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the tested population was 0.25%. In an analysis of different study populations, the percentage was higher in nursing home residents or staff (4.52%), air or cruise ship travelers (2.02%), and pregnant women (2.34%), compared against the pooled percentage.

The pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the confirmed population was 40.50%, and this percentage was higher in pregnant women (54.11%), air or cruise ship travelers (52.91%), and nursing home residents or staff (47.53%).

The pooled percentage in the tested population was higher than the overall percentage when the mean age of the study population was 60 years or older (3.69%). By contrast, in the confirmed population, the pooled percentage was higher than the overall percentage when the study population was younger than 20 years (60.2%) or aged 20 to 39 years (49.5%).

The researchers noted in their discussion that the varying percentage of asymptomatic individuals according to community prevalence might impact the heterogeneity of the included studies. They also noted the high number of studies conducted in nursing home populations, groups in which asymptomatic individuals were more likely to be tested.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for missed studies that were not published at the time of the meta-analysis, as well as the exclusion of studies written in Chinese, the researchers noted. Other limitations included lack of follow-up on presymptomatic and covert infections, and the focus on specific populations, factors that may limit the degree to which the results can be generalized.

However, the results highlight the need to screen for asymptomatic infections, especially in countries where COVID-19 has been better controlled, the researchers said. Management strategies for asymptomatic infections, when identified, should include isolation and contact tracing similar to strategies used with confirmed cases, they added.

More testing needed to catch cases early

“During the initial phase of [the] COVID-19 pandemic, testing was not widely available in the United States or the rest of the world,” Setu Patolia, MD, of Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Missouri, said in an interview. Much of the world still lacks access to COVID-19 testing, and early in the pandemic only severely symptomatic patients were tested, he said. “With new variants, particularly the Omicron variant, which may have mild or minimally symptomatic disease, asymptomatic carriers play an important role in propagation of the pandemic,” he explained. “It is important to know the asymptomatic carrier rate among the general population for the future control of [the] pandemic,” he added.

Dr. Patolia said he was surprised by the study finding that one in 400 people in the general population could be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19.

“Also, nursing home patients are more at risk of complications of COVID, and I expected that they would have a higher rate of symptomatic disease as compared to [the] general population,” said Dr. Patolia. He was also surprised by the high rate of asymptomatic infections in travelers.

“Physicians should be more aware about the asymptomatic carrier rate, particularly in travelers and nursing home patients,” he noted. “Travelers carry high risk of transferring infection from one region to another region of the world, and physicians should advise them to get tested despite the absence of symptoms,” Dr. Patolia emphasized. “Similarly, once any nursing home patient has been diagnosed with COVID-19, physicians should be more careful with the rest of the nursing home patients and test them despite the absence of the symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Patolia also recommended that pregnant women wear masks to help prevent disease transmission when visiting a doctor’s office or labor unit.

Looking ahead, there is a need for cheaper at-home testing kits so that all vulnerable populations can be tested fast and frequently, Dr. Patolia said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Patolia has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Based on data from a meta-analysis of 95 studies that included nearly 30,000,000 individuals, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic COVID-19 infections was 0.25% in the tested population and 40.5% among confirmed cases.

, wrote Qiuyue Ma, PhD, and colleagues of Peking University, Beijing.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open the researchers identified 44 cross-sectional studies, 41 cohort studies, seven case series, and three case series on transmission studies. A total of 74 studies were conducted in developed countries, including those in Europe, North America, and Asia. Approximately one-third (37) of the studies were conducted among health care workers or in-hospital patients, 17 among nursing home staff or residents, and 14 among community residents. In addition, 13 studies involved pregnant women, eight involved air or cruise ship travelers, and six involved close contacts of individuals with confirmed infections.

The meta-analysis included 29,776,306 tested individuals; 11,516 of them had asymptomatic infections.

Overall, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the tested population was 0.25%. In an analysis of different study populations, the percentage was higher in nursing home residents or staff (4.52%), air or cruise ship travelers (2.02%), and pregnant women (2.34%), compared against the pooled percentage.

The pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections among the confirmed population was 40.50%, and this percentage was higher in pregnant women (54.11%), air or cruise ship travelers (52.91%), and nursing home residents or staff (47.53%).

The pooled percentage in the tested population was higher than the overall percentage when the mean age of the study population was 60 years or older (3.69%). By contrast, in the confirmed population, the pooled percentage was higher than the overall percentage when the study population was younger than 20 years (60.2%) or aged 20 to 39 years (49.5%).

The researchers noted in their discussion that the varying percentage of asymptomatic individuals according to community prevalence might impact the heterogeneity of the included studies. They also noted the high number of studies conducted in nursing home populations, groups in which asymptomatic individuals were more likely to be tested.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the potential for missed studies that were not published at the time of the meta-analysis, as well as the exclusion of studies written in Chinese, the researchers noted. Other limitations included lack of follow-up on presymptomatic and covert infections, and the focus on specific populations, factors that may limit the degree to which the results can be generalized.

However, the results highlight the need to screen for asymptomatic infections, especially in countries where COVID-19 has been better controlled, the researchers said. Management strategies for asymptomatic infections, when identified, should include isolation and contact tracing similar to strategies used with confirmed cases, they added.

More testing needed to catch cases early

“During the initial phase of [the] COVID-19 pandemic, testing was not widely available in the United States or the rest of the world,” Setu Patolia, MD, of Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Missouri, said in an interview. Much of the world still lacks access to COVID-19 testing, and early in the pandemic only severely symptomatic patients were tested, he said. “With new variants, particularly the Omicron variant, which may have mild or minimally symptomatic disease, asymptomatic carriers play an important role in propagation of the pandemic,” he explained. “It is important to know the asymptomatic carrier rate among the general population for the future control of [the] pandemic,” he added.

Dr. Patolia said he was surprised by the study finding that one in 400 people in the general population could be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19.

“Also, nursing home patients are more at risk of complications of COVID, and I expected that they would have a higher rate of symptomatic disease as compared to [the] general population,” said Dr. Patolia. He was also surprised by the high rate of asymptomatic infections in travelers.

“Physicians should be more aware about the asymptomatic carrier rate, particularly in travelers and nursing home patients,” he noted. “Travelers carry high risk of transferring infection from one region to another region of the world, and physicians should advise them to get tested despite the absence of symptoms,” Dr. Patolia emphasized. “Similarly, once any nursing home patient has been diagnosed with COVID-19, physicians should be more careful with the rest of the nursing home patients and test them despite the absence of the symptoms,” he added.

Dr. Patolia also recommended that pregnant women wear masks to help prevent disease transmission when visiting a doctor’s office or labor unit.

Looking ahead, there is a need for cheaper at-home testing kits so that all vulnerable populations can be tested fast and frequently, Dr. Patolia said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Patolia has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Appendicitis: Up-front antibiotics OK in select patients

a comprehensive review of the literature suggests.

“I think this is a wonderful thing that we have for our patients now, because think about the patient who had a heart attack yesterday and has appendicitis today – you don’t want to operate on that patient – so this gives us a wonderful option in an environment where sometimes surgery is just bad timing,” Theodore Pappas, MD, professor of surgery, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

“It’s not that every 25-year-old who comes in should get antibiotics instead of surgery. It’s really better to say that this gives us flexibility for patients who we may not want to operate on immediately, and now we have a great option,” he stressed.

The study was published Dec. 14, 2021, in JAMA.

Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the world, as the authors pointed out.

“We think it’s going to be 60%-70% of patients who are good candidates for consideration of antibiotics,” they speculated.

Current evidence

The review summarizes current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis based on a total of 71 articles including 10 systematic reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 11 practice guidelines. “Appendicitis is classified as uncomplicated or complicated,” the authors explained. Uncomplicated appendicitis is acute appendicitis in the absence of clinical or radiographic signs of perforation.

In contrast, complicated appendicitis is when there is appendiceal rupture with subsequent abscess of phlegmon formation, the definitive diagnosis of which can be confirmed by CT scan. “In cases of diagnostic uncertainty imaging should be performed,” investigators cautioned – usually with ultrasound and CT scans.

If uncomplicated appendicitis is confirmed, three different guidelines now support the role of an antibiotics-first approach, including guidelines from the American Association for Surgery of Trauma. For this group of patients, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage that can be transitioned to outpatient treatment is commonly used. For example, patients may be initially treated with intravenous ertapenem monotherapy or intravenous cephalosporin plus metronidazole, then on discharge put on oral fluoroquinolones plus metronidazole.

Antibiotics that cover streptococci, nonresistant Enterobacteriaceae, and the anaerobes are usually adequate, they added. “The recommended duration of antibiotics is 10 days,” they noted. In most of the clinical trials comparing antibiotics first to surgery, the primary endpoint was treatment failure at 1 year, in other words, recurrence of symptoms during that year-long period. Across a number of clinical trials, that recurrence rate ranged from a low of 15% to a high of 41%.

In contrast, recurrence rarely occurs after surgical appendectomy. Early treatment failure, defined as clinical deterioration or lack of clinical improvement within 24-72 hours following initiation of antibiotics, is much less likely to occur, with a reported rate of between 8% and 12% of patients. The only long-term follow-up of an antibiotics-first approach in uncomplicated appendicitis was done in the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) trial, where at 5 years, the recurrence rate of acute appendicitis was 39% (95% confidence interval, 33.1%-45.3%) in patients initially treated with antibiotics alone.

Typically, there have been no differences in the length of hospital stay in most of the clinical trials reviewed. As Dr. Pappas explained, following a standard appendectomy, patients are typically sent home within 24 hours of undergoing surgery. On the other hand, if treated with intravenous antibiotics first, patients are usually admitted overnight then switched to oral antibiotics on discharge – suggesting that there is little difference in the time spent in hospital between the two groups.

However, there are groups of patients who predictably will not do well on antibiotics first, he cautioned. For example, patients who present with a high fever, shaking and chills, and severe abdominal pain do not have a mild case of appendicitis. Neither do patients who may not look sick but on CT scan, they have a hard piece of stool jammed into the end of the appendix that’s causing the blockage: These patients are also more likely to fail antibiotics, Dr. Pappas added.

“There is also a group of patients who have a much more dilated appendix with some fluid around it,” he noted, “and these patients are less likely to be managed with antibiotics successfully as well.” Lastly, though not part of this review and for whom an antibiotics-first protocol has long been in place, there is a subset of patients who have a perforated appendix, and that perforation has been walled off in a pocket of pus.

“These patients are treated with an antibiotic first because if you operate on them, it’s a mess, whereas if patients are reasonably stable, you can drain the abscess and then put them on antibiotics, and then you can decide 6-8 weeks later if you are going to take the appendix out,” Dr. Pappas said, adding: “Most of the time, what should be happening is the surgeon should consult with the patient and then they can weigh in – here are the options and here’s what I recommend.

“But patients will pick what they pick, and surgery is a very compelling argument: It’s laparoscopic surgery, patients are home in 24 hours, and the complication rate [and the recurrence rate] are incredibly low, so you have to think through all sorts of issues and when you come to a certain conclusion, it has to make a lot of sense to the patient,” Dr. Pappas emphasized.

Asked to comment on the findings, Ram Nirula, MD, D. Rees and Eleanor T. Jensen Presidential Chair in Surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, noted that, as with all things in medicine, nothing is 100%.

“There are times where antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis may be appropriate, and times where appendectomy is most appropriate,” he said in an interview. Most of the evidence now shows that the risk of treatment failure following nonoperative management for uncomplicated appendicitis is significant, ranging from 15% to 40%, as Dr. Nirula reaffirmed.

A more recent randomized controlled trial from the CODA collaborative found that quality of life was similar for patients who got up-front antibiotics as for those who got surgery at 30 days, but the failure rate was high, particularly for those with appendicolith (what review authors would have classified as complicated appendicitis).

Moreover, when looking at this subset of patients, quality of life and patient satisfaction in the antibiotic treatment group were lower than it was for surgical controls, as Dr. Nirula also pointed out. While length of hospital stay was similar, overall health care resource utilization was higher in the antibiotic group. “So, if it were me, I would want my appendix removed at this stage in my life, however, for those who are poor surgical candidates, I would favor antibiotics,” Dr. Nirula stressed. He added that the presence of an appendicolith makes the argument for surgery more compelling, although he would still try antibiotics in patients with an appendicolith who are poor surgical candidates.

Dr. Pappas reported serving as a paid consultant for Transenterix. Dr. Nirula disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a comprehensive review of the literature suggests.

“I think this is a wonderful thing that we have for our patients now, because think about the patient who had a heart attack yesterday and has appendicitis today – you don’t want to operate on that patient – so this gives us a wonderful option in an environment where sometimes surgery is just bad timing,” Theodore Pappas, MD, professor of surgery, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

“It’s not that every 25-year-old who comes in should get antibiotics instead of surgery. It’s really better to say that this gives us flexibility for patients who we may not want to operate on immediately, and now we have a great option,” he stressed.

The study was published Dec. 14, 2021, in JAMA.

Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the world, as the authors pointed out.

“We think it’s going to be 60%-70% of patients who are good candidates for consideration of antibiotics,” they speculated.

Current evidence

The review summarizes current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis based on a total of 71 articles including 10 systematic reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 11 practice guidelines. “Appendicitis is classified as uncomplicated or complicated,” the authors explained. Uncomplicated appendicitis is acute appendicitis in the absence of clinical or radiographic signs of perforation.

In contrast, complicated appendicitis is when there is appendiceal rupture with subsequent abscess of phlegmon formation, the definitive diagnosis of which can be confirmed by CT scan. “In cases of diagnostic uncertainty imaging should be performed,” investigators cautioned – usually with ultrasound and CT scans.

If uncomplicated appendicitis is confirmed, three different guidelines now support the role of an antibiotics-first approach, including guidelines from the American Association for Surgery of Trauma. For this group of patients, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage that can be transitioned to outpatient treatment is commonly used. For example, patients may be initially treated with intravenous ertapenem monotherapy or intravenous cephalosporin plus metronidazole, then on discharge put on oral fluoroquinolones plus metronidazole.

Antibiotics that cover streptococci, nonresistant Enterobacteriaceae, and the anaerobes are usually adequate, they added. “The recommended duration of antibiotics is 10 days,” they noted. In most of the clinical trials comparing antibiotics first to surgery, the primary endpoint was treatment failure at 1 year, in other words, recurrence of symptoms during that year-long period. Across a number of clinical trials, that recurrence rate ranged from a low of 15% to a high of 41%.

In contrast, recurrence rarely occurs after surgical appendectomy. Early treatment failure, defined as clinical deterioration or lack of clinical improvement within 24-72 hours following initiation of antibiotics, is much less likely to occur, with a reported rate of between 8% and 12% of patients. The only long-term follow-up of an antibiotics-first approach in uncomplicated appendicitis was done in the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) trial, where at 5 years, the recurrence rate of acute appendicitis was 39% (95% confidence interval, 33.1%-45.3%) in patients initially treated with antibiotics alone.

Typically, there have been no differences in the length of hospital stay in most of the clinical trials reviewed. As Dr. Pappas explained, following a standard appendectomy, patients are typically sent home within 24 hours of undergoing surgery. On the other hand, if treated with intravenous antibiotics first, patients are usually admitted overnight then switched to oral antibiotics on discharge – suggesting that there is little difference in the time spent in hospital between the two groups.

However, there are groups of patients who predictably will not do well on antibiotics first, he cautioned. For example, patients who present with a high fever, shaking and chills, and severe abdominal pain do not have a mild case of appendicitis. Neither do patients who may not look sick but on CT scan, they have a hard piece of stool jammed into the end of the appendix that’s causing the blockage: These patients are also more likely to fail antibiotics, Dr. Pappas added.

“There is also a group of patients who have a much more dilated appendix with some fluid around it,” he noted, “and these patients are less likely to be managed with antibiotics successfully as well.” Lastly, though not part of this review and for whom an antibiotics-first protocol has long been in place, there is a subset of patients who have a perforated appendix, and that perforation has been walled off in a pocket of pus.

“These patients are treated with an antibiotic first because if you operate on them, it’s a mess, whereas if patients are reasonably stable, you can drain the abscess and then put them on antibiotics, and then you can decide 6-8 weeks later if you are going to take the appendix out,” Dr. Pappas said, adding: “Most of the time, what should be happening is the surgeon should consult with the patient and then they can weigh in – here are the options and here’s what I recommend.

“But patients will pick what they pick, and surgery is a very compelling argument: It’s laparoscopic surgery, patients are home in 24 hours, and the complication rate [and the recurrence rate] are incredibly low, so you have to think through all sorts of issues and when you come to a certain conclusion, it has to make a lot of sense to the patient,” Dr. Pappas emphasized.

Asked to comment on the findings, Ram Nirula, MD, D. Rees and Eleanor T. Jensen Presidential Chair in Surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, noted that, as with all things in medicine, nothing is 100%.

“There are times where antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis may be appropriate, and times where appendectomy is most appropriate,” he said in an interview. Most of the evidence now shows that the risk of treatment failure following nonoperative management for uncomplicated appendicitis is significant, ranging from 15% to 40%, as Dr. Nirula reaffirmed.

A more recent randomized controlled trial from the CODA collaborative found that quality of life was similar for patients who got up-front antibiotics as for those who got surgery at 30 days, but the failure rate was high, particularly for those with appendicolith (what review authors would have classified as complicated appendicitis).

Moreover, when looking at this subset of patients, quality of life and patient satisfaction in the antibiotic treatment group were lower than it was for surgical controls, as Dr. Nirula also pointed out. While length of hospital stay was similar, overall health care resource utilization was higher in the antibiotic group. “So, if it were me, I would want my appendix removed at this stage in my life, however, for those who are poor surgical candidates, I would favor antibiotics,” Dr. Nirula stressed. He added that the presence of an appendicolith makes the argument for surgery more compelling, although he would still try antibiotics in patients with an appendicolith who are poor surgical candidates.

Dr. Pappas reported serving as a paid consultant for Transenterix. Dr. Nirula disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a comprehensive review of the literature suggests.

“I think this is a wonderful thing that we have for our patients now, because think about the patient who had a heart attack yesterday and has appendicitis today – you don’t want to operate on that patient – so this gives us a wonderful option in an environment where sometimes surgery is just bad timing,” Theodore Pappas, MD, professor of surgery, Duke University, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

“It’s not that every 25-year-old who comes in should get antibiotics instead of surgery. It’s really better to say that this gives us flexibility for patients who we may not want to operate on immediately, and now we have a great option,” he stressed.

The study was published Dec. 14, 2021, in JAMA.

Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the world, as the authors pointed out.

“We think it’s going to be 60%-70% of patients who are good candidates for consideration of antibiotics,” they speculated.

Current evidence

The review summarizes current evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis based on a total of 71 articles including 10 systematic reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 11 practice guidelines. “Appendicitis is classified as uncomplicated or complicated,” the authors explained. Uncomplicated appendicitis is acute appendicitis in the absence of clinical or radiographic signs of perforation.

In contrast, complicated appendicitis is when there is appendiceal rupture with subsequent abscess of phlegmon formation, the definitive diagnosis of which can be confirmed by CT scan. “In cases of diagnostic uncertainty imaging should be performed,” investigators cautioned – usually with ultrasound and CT scans.

If uncomplicated appendicitis is confirmed, three different guidelines now support the role of an antibiotics-first approach, including guidelines from the American Association for Surgery of Trauma. For this group of patients, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage that can be transitioned to outpatient treatment is commonly used. For example, patients may be initially treated with intravenous ertapenem monotherapy or intravenous cephalosporin plus metronidazole, then on discharge put on oral fluoroquinolones plus metronidazole.

Antibiotics that cover streptococci, nonresistant Enterobacteriaceae, and the anaerobes are usually adequate, they added. “The recommended duration of antibiotics is 10 days,” they noted. In most of the clinical trials comparing antibiotics first to surgery, the primary endpoint was treatment failure at 1 year, in other words, recurrence of symptoms during that year-long period. Across a number of clinical trials, that recurrence rate ranged from a low of 15% to a high of 41%.

In contrast, recurrence rarely occurs after surgical appendectomy. Early treatment failure, defined as clinical deterioration or lack of clinical improvement within 24-72 hours following initiation of antibiotics, is much less likely to occur, with a reported rate of between 8% and 12% of patients. The only long-term follow-up of an antibiotics-first approach in uncomplicated appendicitis was done in the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) trial, where at 5 years, the recurrence rate of acute appendicitis was 39% (95% confidence interval, 33.1%-45.3%) in patients initially treated with antibiotics alone.

Typically, there have been no differences in the length of hospital stay in most of the clinical trials reviewed. As Dr. Pappas explained, following a standard appendectomy, patients are typically sent home within 24 hours of undergoing surgery. On the other hand, if treated with intravenous antibiotics first, patients are usually admitted overnight then switched to oral antibiotics on discharge – suggesting that there is little difference in the time spent in hospital between the two groups.

However, there are groups of patients who predictably will not do well on antibiotics first, he cautioned. For example, patients who present with a high fever, shaking and chills, and severe abdominal pain do not have a mild case of appendicitis. Neither do patients who may not look sick but on CT scan, they have a hard piece of stool jammed into the end of the appendix that’s causing the blockage: These patients are also more likely to fail antibiotics, Dr. Pappas added.

“There is also a group of patients who have a much more dilated appendix with some fluid around it,” he noted, “and these patients are less likely to be managed with antibiotics successfully as well.” Lastly, though not part of this review and for whom an antibiotics-first protocol has long been in place, there is a subset of patients who have a perforated appendix, and that perforation has been walled off in a pocket of pus.

“These patients are treated with an antibiotic first because if you operate on them, it’s a mess, whereas if patients are reasonably stable, you can drain the abscess and then put them on antibiotics, and then you can decide 6-8 weeks later if you are going to take the appendix out,” Dr. Pappas said, adding: “Most of the time, what should be happening is the surgeon should consult with the patient and then they can weigh in – here are the options and here’s what I recommend.

“But patients will pick what they pick, and surgery is a very compelling argument: It’s laparoscopic surgery, patients are home in 24 hours, and the complication rate [and the recurrence rate] are incredibly low, so you have to think through all sorts of issues and when you come to a certain conclusion, it has to make a lot of sense to the patient,” Dr. Pappas emphasized.

Asked to comment on the findings, Ram Nirula, MD, D. Rees and Eleanor T. Jensen Presidential Chair in Surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, noted that, as with all things in medicine, nothing is 100%.

“There are times where antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis may be appropriate, and times where appendectomy is most appropriate,” he said in an interview. Most of the evidence now shows that the risk of treatment failure following nonoperative management for uncomplicated appendicitis is significant, ranging from 15% to 40%, as Dr. Nirula reaffirmed.

A more recent randomized controlled trial from the CODA collaborative found that quality of life was similar for patients who got up-front antibiotics as for those who got surgery at 30 days, but the failure rate was high, particularly for those with appendicolith (what review authors would have classified as complicated appendicitis).

Moreover, when looking at this subset of patients, quality of life and patient satisfaction in the antibiotic treatment group were lower than it was for surgical controls, as Dr. Nirula also pointed out. While length of hospital stay was similar, overall health care resource utilization was higher in the antibiotic group. “So, if it were me, I would want my appendix removed at this stage in my life, however, for those who are poor surgical candidates, I would favor antibiotics,” Dr. Nirula stressed. He added that the presence of an appendicolith makes the argument for surgery more compelling, although he would still try antibiotics in patients with an appendicolith who are poor surgical candidates.

Dr. Pappas reported serving as a paid consultant for Transenterix. Dr. Nirula disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

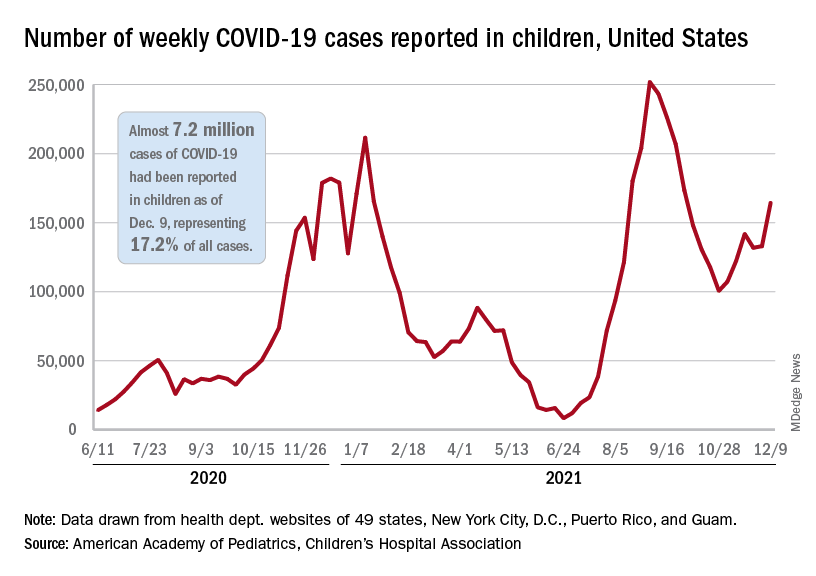

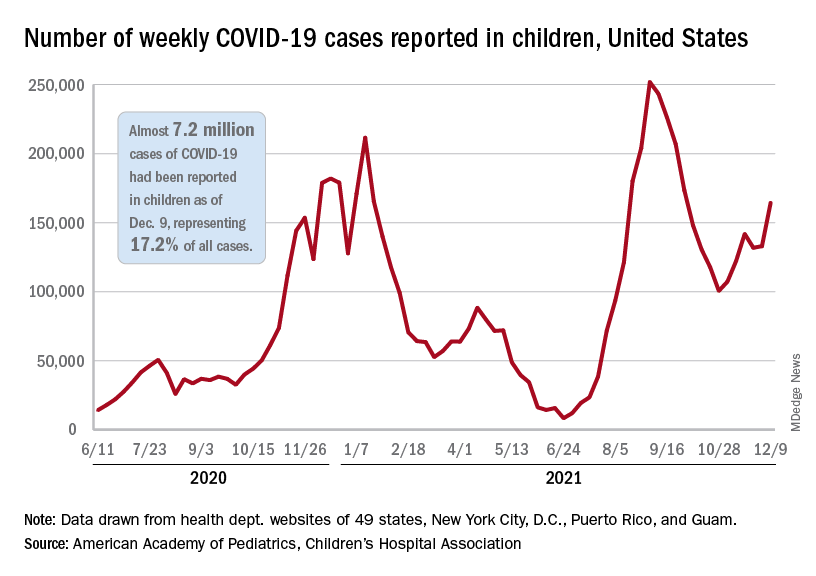

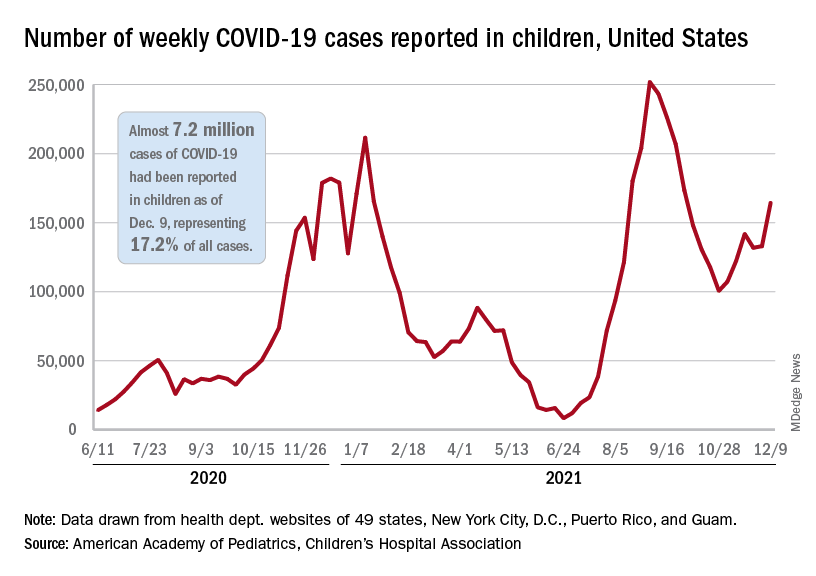

Children and COVID: Weekly cases resume their climb

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

The 7.2 million cumulative cases in children as of Dec. 9 represent 17.2% of all cases reported in the United States since the start of the pandemic, with available state reports showing that proportion ranges from 12.3% in Florida to 26.1% in Vermont. Alaska has the highest incidence of COVID at 19,000 cases per 100,000 children, and Hawaii has the lowest (5,300 per 100,000) among the states currently reporting, the AAP and CHA said.

State reporting on vaccinations shows that 37% of children aged 5-11 years in Massachusetts have received at least one dose, the highest of any state, while West Virginia is lowest at just 4%. The highest vaccination rate for children aged 12-17 goes to Massachusetts at 84%, with Wyoming lowest at 37%, the AAP said in a separate report.

Nationally, new vaccinations fell by a third during the week of Dec. 7-13, compared with the previous week, with the largest decline (34.7%) coming from the 5- to 11-year-olds, who still represented the majority (almost 84%) of the 430,000 new child vaccinations received, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker. Corresponding declines for the last week were 27.5% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 22.7% for those aged 16-17.

Altogether, 21.2 million children aged 5-17 had received at least one dose and 16.0 million were fully vaccinated as of Dec. 13. By age group, 19.2% of children aged 5-11 years have gotten at least one dose and 9.6% are fully vaccinated, compared with 62.1% and 52.3%, respectively, among children aged 12-17, the CDC said.

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

The 7.2 million cumulative cases in children as of Dec. 9 represent 17.2% of all cases reported in the United States since the start of the pandemic, with available state reports showing that proportion ranges from 12.3% in Florida to 26.1% in Vermont. Alaska has the highest incidence of COVID at 19,000 cases per 100,000 children, and Hawaii has the lowest (5,300 per 100,000) among the states currently reporting, the AAP and CHA said.

State reporting on vaccinations shows that 37% of children aged 5-11 years in Massachusetts have received at least one dose, the highest of any state, while West Virginia is lowest at just 4%. The highest vaccination rate for children aged 12-17 goes to Massachusetts at 84%, with Wyoming lowest at 37%, the AAP said in a separate report.

Nationally, new vaccinations fell by a third during the week of Dec. 7-13, compared with the previous week, with the largest decline (34.7%) coming from the 5- to 11-year-olds, who still represented the majority (almost 84%) of the 430,000 new child vaccinations received, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker. Corresponding declines for the last week were 27.5% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 22.7% for those aged 16-17.

Altogether, 21.2 million children aged 5-17 had received at least one dose and 16.0 million were fully vaccinated as of Dec. 13. By age group, 19.2% of children aged 5-11 years have gotten at least one dose and 9.6% are fully vaccinated, compared with 62.1% and 52.3%, respectively, among children aged 12-17, the CDC said.

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.