User login

Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate Crystal Deposition Disease (Pseudogout) of Lumbar Spine Mimicking Osteomyelitis-Discitis With Epidural Phlegmon

Denervated myocardium predicts risk of sudden cardiac death

VANCOUVER, B.C. – The volume of denervated myocardium after a heart attack predicts the likelihood of sudden cardiac death and the need for an implantable defibrillator, according to results from a prospective, 4-year observational study.

"In this study, we found that in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who are eligible for an ICD [implantable cardioverter defibrillator], the volume of denervated myocardium predicts sudden death. It’s independent of more traditional endpoints that have been used," such as B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. "Thus, molecular imaging may improve risk stratification for current ICD candidates," said investigator and cardiologist Dr. Michael E. Cain, dean of the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo (N.Y.).

The goal of the study is to better predict who will benefit from a defibrillator, he said at the 18th World Congress on Heart Disease.

He and his fellow investigators at the university found that about 30% of post-MI patients with more than 33% of their left ventricle denervated experienced arrhythmic death or – in those who had them – a defibrillator discharge for ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation greater than 240 beats per minute within 4 years of their heart attack; on average, about 6.7% met those endpoints each year.

In contrast, only about 5% of patients with less than 22% left ventricular sympathetic denervation met those endpoints, as did about 10% of those with 22%-33% left ventricular denervation, as assessed by myocardial response to a norepinephrine analogue on positron emission tomography. Denervated myocardium had a hazard ratio of 3.5 for sudden cardiac arrest or equivalent in the trial (P = .001).

Thirty-three of 204 post-MI patients experienced arrhythmic death or defibrillator discharge during the project. Most of the patients had undergone initial revascularization, and all were eligible for defibrillators at baseline. Overall, they were in their mid-60s, with left ventricular ejection fractions of about 26% and greater than NYHA class II heart failure. There were no significant demographic differences between patients who did and did not meet the study’s endpoints.

Prediction of sudden cardiac death events was even better when denervation was used in conjunction with three other factors: increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL, and lack of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist therapy.

Four-year event-free survival was about 98% in patients with none of those risk factors, about 85% in patients with one, and 50% in patients with two or more. The volume of infarcted or hibernating myocardium did not predict sudden cardiac arrest.

"The proven metric is left ventricle ejection fraction," but it and the many other methods that have been tried "have good negative predictive accuracy but not that good positive predictive accuracy, and so you are putting in defibrillators for people who don’t need them," he said.

For now, however, it would be "a leap of faith from a study that was prospective and observational" to actually use denervation "to determine therapies," he said.

Dr. Cain reported having no disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – The volume of denervated myocardium after a heart attack predicts the likelihood of sudden cardiac death and the need for an implantable defibrillator, according to results from a prospective, 4-year observational study.

"In this study, we found that in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who are eligible for an ICD [implantable cardioverter defibrillator], the volume of denervated myocardium predicts sudden death. It’s independent of more traditional endpoints that have been used," such as B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. "Thus, molecular imaging may improve risk stratification for current ICD candidates," said investigator and cardiologist Dr. Michael E. Cain, dean of the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo (N.Y.).

The goal of the study is to better predict who will benefit from a defibrillator, he said at the 18th World Congress on Heart Disease.

He and his fellow investigators at the university found that about 30% of post-MI patients with more than 33% of their left ventricle denervated experienced arrhythmic death or – in those who had them – a defibrillator discharge for ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation greater than 240 beats per minute within 4 years of their heart attack; on average, about 6.7% met those endpoints each year.

In contrast, only about 5% of patients with less than 22% left ventricular sympathetic denervation met those endpoints, as did about 10% of those with 22%-33% left ventricular denervation, as assessed by myocardial response to a norepinephrine analogue on positron emission tomography. Denervated myocardium had a hazard ratio of 3.5 for sudden cardiac arrest or equivalent in the trial (P = .001).

Thirty-three of 204 post-MI patients experienced arrhythmic death or defibrillator discharge during the project. Most of the patients had undergone initial revascularization, and all were eligible for defibrillators at baseline. Overall, they were in their mid-60s, with left ventricular ejection fractions of about 26% and greater than NYHA class II heart failure. There were no significant demographic differences between patients who did and did not meet the study’s endpoints.

Prediction of sudden cardiac death events was even better when denervation was used in conjunction with three other factors: increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL, and lack of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist therapy.

Four-year event-free survival was about 98% in patients with none of those risk factors, about 85% in patients with one, and 50% in patients with two or more. The volume of infarcted or hibernating myocardium did not predict sudden cardiac arrest.

"The proven metric is left ventricle ejection fraction," but it and the many other methods that have been tried "have good negative predictive accuracy but not that good positive predictive accuracy, and so you are putting in defibrillators for people who don’t need them," he said.

For now, however, it would be "a leap of faith from a study that was prospective and observational" to actually use denervation "to determine therapies," he said.

Dr. Cain reported having no disclosures.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – The volume of denervated myocardium after a heart attack predicts the likelihood of sudden cardiac death and the need for an implantable defibrillator, according to results from a prospective, 4-year observational study.

"In this study, we found that in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who are eligible for an ICD [implantable cardioverter defibrillator], the volume of denervated myocardium predicts sudden death. It’s independent of more traditional endpoints that have been used," such as B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. "Thus, molecular imaging may improve risk stratification for current ICD candidates," said investigator and cardiologist Dr. Michael E. Cain, dean of the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo (N.Y.).

The goal of the study is to better predict who will benefit from a defibrillator, he said at the 18th World Congress on Heart Disease.

He and his fellow investigators at the university found that about 30% of post-MI patients with more than 33% of their left ventricle denervated experienced arrhythmic death or – in those who had them – a defibrillator discharge for ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation greater than 240 beats per minute within 4 years of their heart attack; on average, about 6.7% met those endpoints each year.

In contrast, only about 5% of patients with less than 22% left ventricular sympathetic denervation met those endpoints, as did about 10% of those with 22%-33% left ventricular denervation, as assessed by myocardial response to a norepinephrine analogue on positron emission tomography. Denervated myocardium had a hazard ratio of 3.5 for sudden cardiac arrest or equivalent in the trial (P = .001).

Thirty-three of 204 post-MI patients experienced arrhythmic death or defibrillator discharge during the project. Most of the patients had undergone initial revascularization, and all were eligible for defibrillators at baseline. Overall, they were in their mid-60s, with left ventricular ejection fractions of about 26% and greater than NYHA class II heart failure. There were no significant demographic differences between patients who did and did not meet the study’s endpoints.

Prediction of sudden cardiac death events was even better when denervation was used in conjunction with three other factors: increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL, and lack of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist therapy.

Four-year event-free survival was about 98% in patients with none of those risk factors, about 85% in patients with one, and 50% in patients with two or more. The volume of infarcted or hibernating myocardium did not predict sudden cardiac arrest.

"The proven metric is left ventricle ejection fraction," but it and the many other methods that have been tried "have good negative predictive accuracy but not that good positive predictive accuracy, and so you are putting in defibrillators for people who don’t need them," he said.

For now, however, it would be "a leap of faith from a study that was prospective and observational" to actually use denervation "to determine therapies," he said.

Dr. Cain reported having no disclosures.

AT THE 18th WORLD CONGRESS ON HEART DISEASE

Major finding: About 30% of post-MI patients with more than 33% of their left ventricle denervated had sudden cardiac arrest.

Data source: Prospective, observational study in 204 post-MI patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Cain reported having no disclosures.

Progressive Hematoma in an Older Adult: Closed Internal Degloving Injury of the Knee

Incidental ovarian cysts: When to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer

Ovarian cysts, sometimes reported as ovarian masses or adnexal masses, are frequently found incidentally in women who have no symptoms. These cysts can be physiologic (having to do with ovulation) or neoplastic—either benign, borderline (having low malignant potential), or frankly malignant. Thus, these incidental lesions pose many diagnostic challenges to the clinician.

The vast majority of cysts are benign, but a few are malignant, and ovarian malignancies have a notoriously poor survival rate. The diagnosis can only be obtained surgically, as aspiration and biopsy are not definitive and may be harmful. Therefore, the clinician must try to balance the risks of surgery for what may be a benign lesion with the risk of delaying diagnosis of a malignancy.

In this article we provide an approach to evaluating these cysts, with guidance on when the patient can be reassured and when referral is needed.

THE DILEMMA OF OVARIAN CYSTS

Ovarian cysts are common

Premenopausal women can be expected to make at least a small cyst or follicle almost every month. The point prevalence for significant cysts has been reported to be almost 8% in premenopausal women.1

Surprisingly, the prevalence in postmenopausal women is as high as 14% to 18%, with a yearly incidence of 8%. From 30% to 54% of postmenopausal ovarian cysts persist for years.2,3

Little is known about the cause of most cysts

Little is known about the cause of most ovarian cysts. Functional or physiologic cysts are thought to be variations in the ovulatory process. They do not seem to be precursors to ovarian cancer.

Most benign neoplastic cysts are also not thought to be precancerous, with the possible exception of the mucinous kind.4 Ovarian cysts do not increase the risk of ovarian cancer later in life,3,9 and removing benign cysts has not been shown to decrease the risk of death from ovarian cancer.10

Most ovarian cysts and masses are benign

Simple ovarian cysts are much more likely to be benign than malignant. Complex and solid ovarian masses are also more likely to be benign, regardless of menopausal status, but more malignancies are found in this group.

With any kind of mass, the chances of malignancy increase with age. Children and adolescents are not discussed in this article; they should be referred to a specialist.

Ovarian cancer often has a poor prognosis

This “silent” cancer is most often discovered and treated when it has already spread, contributing to a reported 5-year survival rate of only 33% to 46%.11–13 Ideally, ovarian cancer would be found and removed while still confined to the ovary, when the 5-year survival rate is greater than 90%.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a precursor lesion for most ovarian cancers, and there is no good way of finding it in the stage 1 phase, so detecting this cancer before it spreads remains an elusive goal.11,14

Surgery is required to diagnose difficult cases

There is no perfect test for the preoperative assessment of a cystic ovarian mass. Every method has drawbacks (Table 1).15–18 Therefore, the National Institutes of Health estimates that 5% to 10% of women in the United States will undergo surgical exploration for an ovarian cyst in their lifetime. Only 13% to 21% of these cysts will be malignant.5

ASSESSING AN INCIDENTALLY DISCOVERED OVARIAN MASS

Certain factors in the history, physical examination, and blood work may suggest the cyst is either benign or malignant and may influence the subsequent assessment. However, in most cases, the best next step is to perform transvaginal ultrasonography, which we will discuss later in this paper.

History

Age is a major risk factor for ovarian cancer; the median age at diagnosis is 63 years.9 In the reproductive-age group, ovarian cysts are much more likely to be functional than neoplastic. Epithelial cancers are rare before the age of 40, but other cancer types such as borderline, germ cell, and sex cord stromal tumors may occur.19

In every age group a cyst is more likely to be benign than malignant, although, as noted above, the probability of malignancy increases with age.

Symptoms. Most ovarian cysts, benign or malignant, are asymptomatic and are found only incidentally.

The most commonly reported symptoms are pelvic or lower-abdominal pressure or pain. Acutely painful conditions include ovarian torsion, hemorrhage into the cyst, cyst rupture with or without intra-abdominal hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess.

Some patients who have ovarian cancer report vague symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency, abdominal distention or bloating, and difficulty eating or early satiety.20 Although the positive predictive value of this symptom constellation is only about 1%, its usefulness increases if these symptoms arose recently (within the past year) and occur than 12 days a month.21

Family history of ovarian, breast, endometrial, or colon cancer is of particular interest. The greater the number of affected relatives and the closer the degree of relation, the greater the risk; in some cases the relative risk is 40 times greater.22 Breast-ovarian cancer syndromes, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, and family cancer syndrome, as well as extremely high-risk pedigrees such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome, all place women at significantly higher risk. Daughters tend to develop cancer at a younger age than their affected mothers.

However, only 10% of ovarian cancers occur in patients who have a family history of it, leaving 90% as sporadic occurrences.

Other history. Factors protective against ovarian cancer include use of oral contraceptives at any time, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, having had children, breastfeeding, a low-fat diet, and possibly use of aspirin and acetaminophen.23,24

Risk factors for malignancy include advanced age; nulliparity; family history of ovarian or breast cancer; personal history of breast cancer; talc use; asbestos exposure; white ethnicity; pelvic irradiation; smoking; alcohol use; possibly the previous use of fertility drugs, estrogen, or androgen; history of mumps; urban location; early menarche; and late menopause.24

Physical examination

Vital signs. Fever can indicate an infectious process or torsion of the ovary. A sudden onset of low blood pressure or rapid pulse can indicate a hemorrhagic condition such as ectopic pregnancy or ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

Bimanual pelvic examination is notoriously inaccurate for detecting and characterizing ovarian cysts. In one prospective study, examiners blinded to the reason for surgery evaluated women under anesthesia. The authors concluded that bimanual examination was of limited value even under the best circumstances.15 Pelvic examination can be even more difficult in patients who are obese, are virginal, have vaginal atrophy, or are in pain.

Useful information that can be obtained through the bimanual examination includes the exact location of pelvic tenderness, the relative firmness of an identified mass, and the existence of nodularity in the posterior cul-de-sac, suggesting advanced ovarian cancer.

Tumor markers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is the most studied and widely used of the ovarian cancer tumor markers. When advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is associated with a markedly elevated level, the value correlates with tumor burden.25

Unfortunately, only about half of early-stage ovarian cancers and 75% to 80% of advanced ovarian cancers express this marker.26 Especially in premenopausal women, there are many pelvic conditions that can falsely elevate CA125. Therefore, its sensitivity and specificity for predicting ovarian cancer are suboptimal. Nevertheless, CA125 is often used to help stratify risk when assessing known ovarian cysts and masses.

The value considered abnormal in postmenopausal women is 35 U/mL or greater, while in premenopausal women the cutoff is less well defined. The lower the cutoff level is set, the more sensitive the test. Recent recommendations advise 50 U/mL or 67 U/mL, rather than the 200 U/mL recommended in the 2002 joint guidelines of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.27,28

However, specificity is likely to be lower with these lower cutoff values. Conditions that can elevate CA125 levels include almost anything that irritates the peritoneum, including pregnancy, menstruation, fibroids, endometriosis, infection, and ovarian hyperstimulation, as well as medical conditions such as liver or renal disease, colitis, diverticulitis, congestive heart failure, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and ascites.

Following serial CA125 levels may be more sensitive than trying to establish a single cutoff value.29 CA125 should not be used as a screening tool in average-risk women.26

OVA1. Several biomarker panels have been developed and evaluated for risk assessment in women with pelvic masses. OVA1, a proprietary panel of tests (Vermillion; Austin, TX) received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2009. It includes CA125 and four other proteins, from which it calculates a probability score (high or low) using a proprietary formula.

In prospective studies, OVA1 was more sensitive than clinical assessment or CA125 alone.30 The higher sensitivity and negative predictive value were counterbalanced by a lower specificity and positive predictive value.31 Its cost ($650) is not always covered by insurance. OVA1 is not a screening tool.

EVALUATION WITH ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice in assessing adnexal cysts and masses, and therefore it is the best next step after taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining blood work.32 In cases in which an incidental ovarian mass is discovered on computed tomography (CT), further characterization by ultrasonography will likely yield helpful information.

Pelvic ultrasonography can be performed transabdominally or transvaginally. Vaginal ultrasonography gives the clearest images in most patients. Abdominal scanning is indicated for large masses, when vaginal access is difficult (as in virginal patients or those with vaginal atrophy) or when the mass is out of the focal length of the vaginal probe. A full bladder is usually required for the best transabdominal images.

The value of the images obtained depends on the experience of the ultrasonographer and reader and on the equipment. Also, there is currently no widely used standard for reporting the findings33—descriptions are individualized, leading some authors to recommend that the clinician personally review the films to get the most accurate picture.19

Size

Size alone cannot be used to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Simple cysts up to 10 cm are most likely benign regardless of menopausal status.2,34 However, in a complex or solid mass, size correlates somewhat with the chance of malignancy, with notable exceptions, such as the famously large sizes of some solid fibromas or mucinous cystadenomas. Also, size may correlate with risk of other complications such as torsion or symptomatic rupture.

Complexity

Simple cysts have clear fluid, thin smooth walls, no loculations or septae, and enhanced through-transmission of echo waves.32,33

Complexity is described in terms of septations, wall thickness, internal echoes, and solid nodules. Increasing complexity does correlate with increased risk of malignancy.

Worrisome findings

The most worrisome findings are:

- Solid areas that are not hyperechoic, especially when there is blood flow to them

- Thick septations, more than 2 or 3 mm wide, especially if there is blood flow within them

- Excrescences on the inner or outer aspect of a cystic area

- Ascites

- Other pelvic or omental masses.

Benign conditions

Several benign conditions have characteristic complex findings on ultrasonography (Table 2), whereas other findings can be indeterminate (Table 3) or worrisome for malignancy (Table 4).

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts can be complex with an internal reticular pattern due to organizing clot and fibrin strands. A “ring of fire” vascular pattern is often seen around the cyst bed.

Dermoids (mature cystic teratomas) may have hyperechoic elements with acoustic shadowing and no internal Doppler flow. They can have a complex appearance due to fat, hair, and sebum within the cyst. Dermoid cysts have a pathognomonic appearance on CT with a clear fat-fluid level.

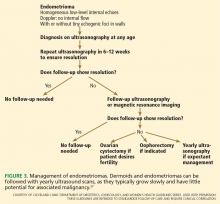

Endometriomas classically have a homogeneous “ground-glass” appearance or low-level echoes, without internal color Doppler flow, wall nodules, or other malignant features.

Fibroids may be pedunculated and may appear to be complex or solid adnexal masses.

Hydrosalpinges may present as tortuous tubular-shaped cystic masses. There may be incomplete septations or indentations seen on opposite sides (the “waist” sign).

Paratubal and paraovarian cysts are usually simple round cysts that can be demonstrated as separate from the ovary. Sometimes these appear complex as well.

Peritoneal inclusion cysts, also known as pseudocysts, are seen in patients with intra-abdominal adhesions. Often multiple septations are seen through clear fluid, with the cyst conforming to the shape of other pelvic structures.

Torsion of the ovary may occur with either benign or malignant masses. Torsion can be diagnosed when venous flow is absent on Doppler. The presence of flow, however, doesn’t rule out torsion, as torsion is often intermittent. The twisted ovary is most often enlarged and can have an edematous appearance. Although typically benign, these should be referred for urgent surgical treatment.

Vascularity

Doppler imaging is being extensively studied. The general principle is that malignant masses will be more vascular, with a high-volume, low-resistance pattern of flow. This can result in a pulsatility index of less than 1 or a resistive index of less than 0.4. In practice, however, there is significant overlap between high and low pulsatility indices and resistive indices in benign and malignant cysts. Low resistance can also be found in endometriomas, corpus luteum cysts, inflammatory masses, and vascular benign neoplasms. A normal (high) resistive index does not rule out malignancy.32,33

One Doppler finding that does seem to correlate with malignancy is the presence of any flow within a solid nodule or wall excrescence.

3D ultrasonography

As the use of 3D ultrasonography increases, studies are yielding different results as to its utility in describing ovarian masses. 3D ultrasonography may be useful in finding centrally located vessels so that Doppler can be applied.32

OTHER IMAGING

Although ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice in the evaluation of adnexal masses owing to its high sensitivity, availability, and low cost, studies have shown that up to 20% of adnexal masses can be reported as indeterminate by ultrasonography (Table 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as a very valuable tool when ultrasonography is inconclusive or limited.35 Although MRI is very accurate (Table 1), it is not considered a first-line imaging test because it is more expensive, less available, and more inconvenient for the patient than ultrasonography.

MRI provides additional information on the composition of soft-tissue tumors. Usually, MRI is ordered with contrast, unless there are contraindications to it. The radiologist will evaluate morphologic features, signal intensity, and enhancement of solid areas. Techniques such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (following the distribution of contrast material over time), in- and out-of-phase T1 imaging (looking for fat, such as in dermoids), and the newer diffusion-weighted imaging may further improve characterization.

In one study of MRI as second-line imaging, contrast-enhanced MRI contributed to a greater change in the probability of ovarian cancer than did CT, Doppler ultrasonography, or MRI without contrast.36 This may result in a reduction in unnecessary surgeries and in an increase in proper referrals in cases of suspected malignancy.

Computed tomography

Disadvantages of CT include radiation exposure and poor discrimination of soft tissue. It can, however, differentiate fat or calcifications that may be found in dermoids. While CT is not often used to describe an ovarian lesion, it may be used preoperatively to stage an ovarian cancer or to look for a primary intra-abdominal cancer when an ovarian mass may represent metastasis.32

MANAGING AN INCIDENTAL OVARIAN CYST OR CYSTIC MASS

Combining information from the history, physical examination, imaging, and blood work to assign a level of risk of malignancy is not straightforward. The clinician must weigh several imperfect tests, each with its own sensitivity and specificity, against the background of the individual patient’s likelihood of malignancy. Whereas a 4-cm simple cyst in a premenopausal woman can be assigned to a low-risk category and a complex mass with flow to a solid component in a postmenopausal woman can be assigned to a high-risk category, many lesions are more difficult to assess.

Several systems have been proposed for analyzing data and standardizing risk assessment. There are a number of scoring systems based on ultrasonographic morphology and several mathematical regression models that include menopausal status and tumor markers. But each has drawbacks, and none is definitively superior to expert opinion.16,17,37,38

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis39 calculated sensitivity and specificity for several imaging tests, scoring systems, and blood tumor markers. Some results are presented in Table 1.

The management of an ovarian cyst depends on symptoms, likelihood of torsion or rupture, and the level of concern for malignancy. At the lower-risk end of the spectrum, reassurance or observation over time may be appropriate. A general gynecologist can evaluate indeterminate or symptomatic ovarian cysts. Patients with masses frankly suspicious for malignancy are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

Expectant management for low-risk lesions

Low-risk lesions such as simple cysts, endometriomas, and dermoids have a less than 1% chance of malignancy. Most patients who have them require only reassurance or follow-up with serial ultrasonography. Oral contraceptives may prevent new cysts from forming. Aspiration is not recommended.

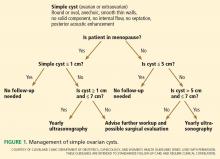

In 2010, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound issued a consensus statement regarding re-imaging of simple ovarian cysts.33

In premenopausal women, they recommend no further testing for cysts 5 cm or smaller, yearly follow-up for cysts larger than 5 cm and up to and including 7 cm, and MRI or surgical evaluation for cysts larger than 7 cm, as it is difficult to completely image a large cyst with ultrasonography.

In postmenopausal women, if the cyst is 1 cm in diameter or smaller, no further studies need to be done. For simple cysts larger than 1 cm and up to and including 7 cm, yearly re-imaging is recommended. And for cysts larger than 7 cm, MRI or surgery is indicated. The American College of Radiology recommends repeat ultrasonography and CA125 testing for cysts 3 cm and larger but doesn’t specify an interval.32

A cyst that is otherwise simple but has a single thin septation (< 3 mm) or a small calcification in the wall is almost always benign. Such a cyst should be followed as if it were a simple cyst, as indicated by patient age and cyst size.

There are no official guidelines as to when to stop serial imaging,22,32 but a recent paper suggested one or two ultrasonographic examinations to confirm size and morphologic stability.19 Once a lesion has resolved, there is no need for further imaging (Figures 1–3).

Birth control pills for suppression of new cysts. Oral contraceptives do not hasten the resolution of ovarian cysts, according to a 2011 Cochrane review.40 Some practitioners will, nevertheless, prescribe them in an attempt to prevent new cysts from confusing the picture.

Aspiration is not recommended for either diagnosis or treatment. It can only be considered in patients at high risk who are not surgical candidates. Results of cytologic study of specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration cannot reliably determine the presence or absence of malignancy.41 There is also a theoretical risk of spreading cancer from an early-stage lesion. A retrospective study has suggested that spillage of cyst contents during surgery in early ovarian cancer is associated with a worse prognosis.42

From a therapeutic point of view, studies have shown the same resolution rate at 6 months for aspirated cysts vs those followed expectantly.43 Another study found a recurrence rate of 25% within 1 year of aspiration.44

Referral for medium-risk or indeterminant-risk ovarian masses

Patients who have medium- or indeterminaterisk ovarian masses (Table 3) should be referred to a gynecologist. Further testing will help stratify the risk of malignancy. This can include tumor marker blood tests, MRI, or CT, the addition of Doppler or 3D ultrasonography, serial ultrasonography, or surgical exploration.

If repeat ultrasonography is chosen, the interval will likely be 6 to 12 weeks. Surgery may consist of removing only the cyst itself, or the whole ovary with or without the tube, or sometimes both ovaries. Purely diagnostic laparoscopy is rarely performed, as direct visualization of a lesion is rarely helpful. Frozen section should be employed, and the operating gynecologist should have oncologic backup, since the surgery is performed to rule out malignancy.

In the case of a benign-appearing cyst larger than 6 cm, thought must be given as to whether it is likely to rupture or twist. Rupture of a large cyst can lead to pain and in some cases to hemorrhage. Contents of a ruptured dermoid cyst can cause chemical peritonitis. Torsion of an ovary can result in loss of the ovary through compromised perfusion. A general gynecologist can decide with the patient whether preemptive surgery is indicated.

Operative evaluation for high-risk masses

Patients with high-risk ovarian masses (Table 4) are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist for operative evaluation. If features are seen that indicate malignancy, such as thick septations, solid areas with blood flow, ascites, or other pelvic masses, surgery is indicated. The surgical approach may be through laparoscopy or laparotomy.45 It should be noted that even in the face of worrisome features on ultrasonography, many masses turn out to be benign.

In 2011, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology issued new guidelines recommending oncologic referral of patients with high-risk masses. Elevated CA125, ascites, a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, or evidence of metastasis in postmenopausal women requires oncologic evaluation.26 For premenopausal women, a very elevated CA125, ascites, or metastasis requires referral (Table 4).26

Direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist is underutilized. A recent study found that fewer than half of primary care physicians said that they would refer a classic suspicious case directly to a subspecialist.46 It is estimated that only 33% of ovarian cancers are first operated on by a gynecologic oncologist.47

A 2011 Cochrane review confirmed a survival benefit for women with cancer who are operated on by gynecologic oncologists primarily, rather than by a general gynecologist and then referred.48 A gynecologic oncologist is most likely to perform proper staging and debulking at the time of initial diagnosis.49

Special situations require consultation

Ovarian cysts in pregnancy are most often benign,50 but malignancy is always a possibility. Functional cysts and dermoids are the most common. These may remain asymptomatic or may rupture or twist or cause difficulty with delivering the baby. Surgical intervention, if needed, should be performed in the second trimester if possible. A multidisciplinary approach and referral to a perinatologist and gynecologic oncologist are advised.

Symptomatic ovarian cysts that may need surgical intervention are the purview of the general gynecologist. If the risk of a surgical emergency is judged to be low, a symptomatic patient may be supported with pain medication and may be managed on an outpatient basis. Immediate surgical consultation is appropriate if the patient appears toxic or in shock. Depending on the clinical picture, there may be a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, ruptured hemorrhagic cyst, or ovarian torsion, any of which may need immediate surgical intervention.

If a symptomatic mass is highly suspicious for cancer, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted directly.

WHEN TO REASSURE, REASSESS, REFER

Ovarian masses often pose diagnostic and management dilemmas. Reassurance can be offered to women with small simple cysts. Interval follow-up with ultrasonography is appropriate for cysts that are most likely to be benign. If malignancy is suspected based on ultrasonography, other imaging, blood testing, or expert opinion, referral to a surgical gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist is recommended. If malignancy is strongly suspected, direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist offers the best chance of survival if cancer is actually present.

Reassure

- When simple cysts are less than 1 cm in postmenopausal women

- When simple cysts are less than 5 cm in premenopausal patients.

Reassess

- With yearly ultrasonography in cases of very low risk

- With repeat ultrasonography in 6 to 12 weeks when the diagnosis is not clear but the cyst is likely benign.

Refer

- To a gynecologist for symptomatic cysts, cysts larger than 6 cm, and cysts that require ancillary testing

- To a gynecologic oncologist for findings worrisome for cancer, such as thick septations, solid areas with flow, ascites, evidence of metastasis, or high cancer antigen 125 levels.

- Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Transvaginal sonographic ovarian findings in a random sample of women 25–40 years old. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 13:345–350.

- Modesitt SC, Pavlik EJ, Ueland FR, DePriest PD, Kryscio RJ, van Nagell JR. Risk of malignancy in unilocular ovarian cystic tumors less than 10 centimeters in diameter. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:594–599.

- Greenlee RT, Kessel B, Williams CR, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and natural history of simple ovarian cysts among women > 55 years old in a large cancer screening trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202:373.e1–373.e9.

- Jordan SJ, Green AC, Whiteman DC, Webb PM; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Risk factors for benign, borderline and invasive mucinous ovarian tumors: epidemiological evidence of a neoplastic continuum? Gynecol Oncol 2007; 107:223–230.

- NIH consensus conference. Ovarian cancer. Screening, treatment, and follow-up. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer. JAMA 1995; 273:491–497.

- The reduction in risk of ovarian cancer associated with oral-contraceptive use. The Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:650–655.

- Young RL, Snabes MC, Frank ML, Reilly M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of the impact of low-dose and triphasic oral contraceptives on follicular development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167:678–682.

- Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E, et al. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the Nurses’ Health Study. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113:1027–1037.

- Sharma A, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, et al; UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Assessing the malignant potential of ovarian inclusion cysts in postmenopausal women within the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2012; 119:207–219.

- Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al; PLCO Project Team. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2011; 305:2295–2303.

- Clarke-Pearson DL. Clinical practice. Screening for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:170–177.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). Cancer statistics on ovarian cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed May 9, 2013.

- American Cancer Society. Survival by ovarian cancer stage. www.cancer.org/Cancer/OvarianCancer/DetailedGuide/ovarian-cancer-survival-rates. Accessed May 9, 2013.

- Brown PO, Palmer C. The preclinical natural history of serous ovarian cancer: defining the target for early detection. PLoS Med 2009; 6:e1000114.

- Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Limitations of the pelvic examination for evaluation of the female pelvic organs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005; 88:84–88.

- Myers ER, Bastian LA, Havrilesky LJ, et al. Management of Adnexal Mass. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.130 (Prepared by the Duke Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0025.) AHRQ Publication No. 06-E004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2006.

- Ameye L, Timmerman D, Valentin L, et al. Clinically oriented three-step strategy for assessment of adnexal pathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012; 40:582–591.

- Covens AL, Dodge JE, Lacchetti C, et al; Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group. Surgical management of a suspicious adnexal mass: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 126:149–156.

- Liu JH, Zanotti KM. Management of the adnexal mass. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:1413–1428.

- Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer 2007; 109:221–227.

- Rossing MA, Wicklund KG, Cushing-Haugen KL, Weiss NS. Predictive value of symptoms for early detection of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102:222–229.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 110:201–214.

- BestPractice BMJ Evidence Centre. Ovarian cysts-Diagnosis-History & examination—Risk factors. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/660/diagnosis.html. Accessed June 2, 2013.

- American Cancer Society. Ovarian-cancer risk factors. www.cancer.org/Cancer/OvarianCancer/DetailedGuide/ovarian-cancer-survival-rates. Accessed May 9, 2013.

- Bast RC, Klug TL, St John E, et al. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 1983; 309:883–887.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No. 477: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:742–746.

- Im SS, Gordon AN, Buttin BM, et al. Validation of referral guidelines for women with pelvic masses. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 105:35–41.

- Dearking AC, Aletti GD, McGree ME, Weaver AL, Sommerfield MK, Cliby WA. How relevant are ACOG and SGO guidelines for referral of adnexal mass? Obstet Gynecol 2007; 110:841–848.

- Skates SJ, Menon U, MacDonald N, et al. Calculation of the risk of ovarian cancer from serial CA-125 values for preclinical detection in postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21(suppl 10):206s–210s.

- Ueland FR, Desimone CP, Seamon LG, et al. Effectiveness of a multivariate index assay in the preoperative assessment of ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:1289–1297.

- Ware Miller R, Smith A, DeSimone CP, et al. Performance of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ ovarian tumor referral guidelines with a multivariate index assay. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 117:1298–1306.

- Lev-Toaff AS, Horrow MM, Andreotti RF, et al. Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria clinically suspected adnexal mass. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology (ACR), 2009. www.guidelines.gov/content.aspx?id=15780&search=adnexal+mass. Accessed May 9, 2013.

- Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology 2010; 256:943–954.

- Alcázar JL, Castillo G, Jurado M, García GL. Is expectant management of sonographically benign adnexal cysts an option in selected asymptomatic premenopausal women? Hum Reprod 2005; 20:3231–3234.

- Medeiros LR, Freitas LB, Rosa DD, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in ovarian tumor: a systematic quantitative review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204:67.e1–67.e10.

- Kinkel K, Lu Y, Mehdizade A, Pelte MF, Hricak H. Indeterminate ovarian mass at US: incremental value of second imaging test for characterization—meta-analysis and Bayesian analysis. Radiology 2005; 236:85–94.

- Timmerman D, Ameye L, Fischerova D, et al. Simple ultrasound rules to distinguish between benign and malignant adnexal masses before surgery: prospective validation by IOTA group. BMJ 2010; 341:c6839.

- Valentin L, Ameye L, Savelli L, et al. Adnexal masses difficult to classify as benign or malignant using subjective assessment of gray-scale and Doppler ultrasound findings: logistic regression models do not help. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38:456–465.

- Dodge JE, Covens AL, Lacchetti C, et al; Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group. Preoperative identification of a suspicious adnexal mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 126:157–166.

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 9:CD006134.

- Higgins RV, Matkins JF, Marroum MC. Comparison of fine-needle aspiration cytologic findings of ovarian cysts with ovarian histologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180:550–553.

- Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet 2001; 357:176–182.

- Zanetta G, Lissoni A, Torri V, et al. Role of puncture and aspiration in expectant management of simple ovarian cysts: a randomised study. BMJ 1996; 313:1110–1113.

- Bonilla-Musoles F, Ballester MJ, Simon C, Serra V, Raga F. Is avoidance of surgery possible in patients with perimenopausal ovarian tumors using transvaginal ultrasound and duplex color Doppler sonography? J Ultrasound Med 1993; 12:33–39.

- Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Bozzetti MC, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for FIGO Stage I ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 4:CD005344.

- Goff BA, Miller JW, Matthews B, et al. Involvement of gynecologic oncologists in the treatment of patients with a suspicious ovarian mass. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 118:854–862.

- Earle CC, Schrag D, Neville BA, et al. Effect of surgeon specialty on processes of care and outcomes for ovarian cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98:172–180.

- Giede KC, Kieser K, Dodge J, Rosen B. Who should operate on patients with ovarian cancer? An evidence-based review. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 99:447–461.

- Cress RD, Bauer K, O’Malley CD, et al. Surgical staging of early stage epithelial ovarian cancer: results from the CDC-NPCR ovarian patterns of care study. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 121:94–99.

- Horowitz NS. Management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2011; 54:519–527.

Ovarian cysts, sometimes reported as ovarian masses or adnexal masses, are frequently found incidentally in women who have no symptoms. These cysts can be physiologic (having to do with ovulation) or neoplastic—either benign, borderline (having low malignant potential), or frankly malignant. Thus, these incidental lesions pose many diagnostic challenges to the clinician.

The vast majority of cysts are benign, but a few are malignant, and ovarian malignancies have a notoriously poor survival rate. The diagnosis can only be obtained surgically, as aspiration and biopsy are not definitive and may be harmful. Therefore, the clinician must try to balance the risks of surgery for what may be a benign lesion with the risk of delaying diagnosis of a malignancy.

In this article we provide an approach to evaluating these cysts, with guidance on when the patient can be reassured and when referral is needed.

THE DILEMMA OF OVARIAN CYSTS

Ovarian cysts are common

Premenopausal women can be expected to make at least a small cyst or follicle almost every month. The point prevalence for significant cysts has been reported to be almost 8% in premenopausal women.1

Surprisingly, the prevalence in postmenopausal women is as high as 14% to 18%, with a yearly incidence of 8%. From 30% to 54% of postmenopausal ovarian cysts persist for years.2,3

Little is known about the cause of most cysts

Little is known about the cause of most ovarian cysts. Functional or physiologic cysts are thought to be variations in the ovulatory process. They do not seem to be precursors to ovarian cancer.

Most benign neoplastic cysts are also not thought to be precancerous, with the possible exception of the mucinous kind.4 Ovarian cysts do not increase the risk of ovarian cancer later in life,3,9 and removing benign cysts has not been shown to decrease the risk of death from ovarian cancer.10

Most ovarian cysts and masses are benign

Simple ovarian cysts are much more likely to be benign than malignant. Complex and solid ovarian masses are also more likely to be benign, regardless of menopausal status, but more malignancies are found in this group.

With any kind of mass, the chances of malignancy increase with age. Children and adolescents are not discussed in this article; they should be referred to a specialist.

Ovarian cancer often has a poor prognosis

This “silent” cancer is most often discovered and treated when it has already spread, contributing to a reported 5-year survival rate of only 33% to 46%.11–13 Ideally, ovarian cancer would be found and removed while still confined to the ovary, when the 5-year survival rate is greater than 90%.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a precursor lesion for most ovarian cancers, and there is no good way of finding it in the stage 1 phase, so detecting this cancer before it spreads remains an elusive goal.11,14

Surgery is required to diagnose difficult cases

There is no perfect test for the preoperative assessment of a cystic ovarian mass. Every method has drawbacks (Table 1).15–18 Therefore, the National Institutes of Health estimates that 5% to 10% of women in the United States will undergo surgical exploration for an ovarian cyst in their lifetime. Only 13% to 21% of these cysts will be malignant.5

ASSESSING AN INCIDENTALLY DISCOVERED OVARIAN MASS

Certain factors in the history, physical examination, and blood work may suggest the cyst is either benign or malignant and may influence the subsequent assessment. However, in most cases, the best next step is to perform transvaginal ultrasonography, which we will discuss later in this paper.

History

Age is a major risk factor for ovarian cancer; the median age at diagnosis is 63 years.9 In the reproductive-age group, ovarian cysts are much more likely to be functional than neoplastic. Epithelial cancers are rare before the age of 40, but other cancer types such as borderline, germ cell, and sex cord stromal tumors may occur.19

In every age group a cyst is more likely to be benign than malignant, although, as noted above, the probability of malignancy increases with age.

Symptoms. Most ovarian cysts, benign or malignant, are asymptomatic and are found only incidentally.

The most commonly reported symptoms are pelvic or lower-abdominal pressure or pain. Acutely painful conditions include ovarian torsion, hemorrhage into the cyst, cyst rupture with or without intra-abdominal hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess.

Some patients who have ovarian cancer report vague symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency, abdominal distention or bloating, and difficulty eating or early satiety.20 Although the positive predictive value of this symptom constellation is only about 1%, its usefulness increases if these symptoms arose recently (within the past year) and occur than 12 days a month.21

Family history of ovarian, breast, endometrial, or colon cancer is of particular interest. The greater the number of affected relatives and the closer the degree of relation, the greater the risk; in some cases the relative risk is 40 times greater.22 Breast-ovarian cancer syndromes, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, and family cancer syndrome, as well as extremely high-risk pedigrees such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome, all place women at significantly higher risk. Daughters tend to develop cancer at a younger age than their affected mothers.

However, only 10% of ovarian cancers occur in patients who have a family history of it, leaving 90% as sporadic occurrences.

Other history. Factors protective against ovarian cancer include use of oral contraceptives at any time, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, having had children, breastfeeding, a low-fat diet, and possibly use of aspirin and acetaminophen.23,24

Risk factors for malignancy include advanced age; nulliparity; family history of ovarian or breast cancer; personal history of breast cancer; talc use; asbestos exposure; white ethnicity; pelvic irradiation; smoking; alcohol use; possibly the previous use of fertility drugs, estrogen, or androgen; history of mumps; urban location; early menarche; and late menopause.24

Physical examination

Vital signs. Fever can indicate an infectious process or torsion of the ovary. A sudden onset of low blood pressure or rapid pulse can indicate a hemorrhagic condition such as ectopic pregnancy or ruptured hemorrhagic cyst.

Bimanual pelvic examination is notoriously inaccurate for detecting and characterizing ovarian cysts. In one prospective study, examiners blinded to the reason for surgery evaluated women under anesthesia. The authors concluded that bimanual examination was of limited value even under the best circumstances.15 Pelvic examination can be even more difficult in patients who are obese, are virginal, have vaginal atrophy, or are in pain.

Useful information that can be obtained through the bimanual examination includes the exact location of pelvic tenderness, the relative firmness of an identified mass, and the existence of nodularity in the posterior cul-de-sac, suggesting advanced ovarian cancer.

Tumor markers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is the most studied and widely used of the ovarian cancer tumor markers. When advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is associated with a markedly elevated level, the value correlates with tumor burden.25

Unfortunately, only about half of early-stage ovarian cancers and 75% to 80% of advanced ovarian cancers express this marker.26 Especially in premenopausal women, there are many pelvic conditions that can falsely elevate CA125. Therefore, its sensitivity and specificity for predicting ovarian cancer are suboptimal. Nevertheless, CA125 is often used to help stratify risk when assessing known ovarian cysts and masses.

The value considered abnormal in postmenopausal women is 35 U/mL or greater, while in premenopausal women the cutoff is less well defined. The lower the cutoff level is set, the more sensitive the test. Recent recommendations advise 50 U/mL or 67 U/mL, rather than the 200 U/mL recommended in the 2002 joint guidelines of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.27,28

However, specificity is likely to be lower with these lower cutoff values. Conditions that can elevate CA125 levels include almost anything that irritates the peritoneum, including pregnancy, menstruation, fibroids, endometriosis, infection, and ovarian hyperstimulation, as well as medical conditions such as liver or renal disease, colitis, diverticulitis, congestive heart failure, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and ascites.

Following serial CA125 levels may be more sensitive than trying to establish a single cutoff value.29 CA125 should not be used as a screening tool in average-risk women.26

OVA1. Several biomarker panels have been developed and evaluated for risk assessment in women with pelvic masses. OVA1, a proprietary panel of tests (Vermillion; Austin, TX) received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2009. It includes CA125 and four other proteins, from which it calculates a probability score (high or low) using a proprietary formula.

In prospective studies, OVA1 was more sensitive than clinical assessment or CA125 alone.30 The higher sensitivity and negative predictive value were counterbalanced by a lower specificity and positive predictive value.31 Its cost ($650) is not always covered by insurance. OVA1 is not a screening tool.

EVALUATION WITH ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice in assessing adnexal cysts and masses, and therefore it is the best next step after taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining blood work.32 In cases in which an incidental ovarian mass is discovered on computed tomography (CT), further characterization by ultrasonography will likely yield helpful information.

Pelvic ultrasonography can be performed transabdominally or transvaginally. Vaginal ultrasonography gives the clearest images in most patients. Abdominal scanning is indicated for large masses, when vaginal access is difficult (as in virginal patients or those with vaginal atrophy) or when the mass is out of the focal length of the vaginal probe. A full bladder is usually required for the best transabdominal images.

The value of the images obtained depends on the experience of the ultrasonographer and reader and on the equipment. Also, there is currently no widely used standard for reporting the findings33—descriptions are individualized, leading some authors to recommend that the clinician personally review the films to get the most accurate picture.19

Size

Size alone cannot be used to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Simple cysts up to 10 cm are most likely benign regardless of menopausal status.2,34 However, in a complex or solid mass, size correlates somewhat with the chance of malignancy, with notable exceptions, such as the famously large sizes of some solid fibromas or mucinous cystadenomas. Also, size may correlate with risk of other complications such as torsion or symptomatic rupture.

Complexity

Simple cysts have clear fluid, thin smooth walls, no loculations or septae, and enhanced through-transmission of echo waves.32,33

Complexity is described in terms of septations, wall thickness, internal echoes, and solid nodules. Increasing complexity does correlate with increased risk of malignancy.

Worrisome findings

The most worrisome findings are:

- Solid areas that are not hyperechoic, especially when there is blood flow to them

- Thick septations, more than 2 or 3 mm wide, especially if there is blood flow within them

- Excrescences on the inner or outer aspect of a cystic area

- Ascites

- Other pelvic or omental masses.

Benign conditions

Several benign conditions have characteristic complex findings on ultrasonography (Table 2), whereas other findings can be indeterminate (Table 3) or worrisome for malignancy (Table 4).

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts can be complex with an internal reticular pattern due to organizing clot and fibrin strands. A “ring of fire” vascular pattern is often seen around the cyst bed.

Dermoids (mature cystic teratomas) may have hyperechoic elements with acoustic shadowing and no internal Doppler flow. They can have a complex appearance due to fat, hair, and sebum within the cyst. Dermoid cysts have a pathognomonic appearance on CT with a clear fat-fluid level.

Endometriomas classically have a homogeneous “ground-glass” appearance or low-level echoes, without internal color Doppler flow, wall nodules, or other malignant features.

Fibroids may be pedunculated and may appear to be complex or solid adnexal masses.

Hydrosalpinges may present as tortuous tubular-shaped cystic masses. There may be incomplete septations or indentations seen on opposite sides (the “waist” sign).

Paratubal and paraovarian cysts are usually simple round cysts that can be demonstrated as separate from the ovary. Sometimes these appear complex as well.

Peritoneal inclusion cysts, also known as pseudocysts, are seen in patients with intra-abdominal adhesions. Often multiple septations are seen through clear fluid, with the cyst conforming to the shape of other pelvic structures.

Torsion of the ovary may occur with either benign or malignant masses. Torsion can be diagnosed when venous flow is absent on Doppler. The presence of flow, however, doesn’t rule out torsion, as torsion is often intermittent. The twisted ovary is most often enlarged and can have an edematous appearance. Although typically benign, these should be referred for urgent surgical treatment.

Vascularity

Doppler imaging is being extensively studied. The general principle is that malignant masses will be more vascular, with a high-volume, low-resistance pattern of flow. This can result in a pulsatility index of less than 1 or a resistive index of less than 0.4. In practice, however, there is significant overlap between high and low pulsatility indices and resistive indices in benign and malignant cysts. Low resistance can also be found in endometriomas, corpus luteum cysts, inflammatory masses, and vascular benign neoplasms. A normal (high) resistive index does not rule out malignancy.32,33

One Doppler finding that does seem to correlate with malignancy is the presence of any flow within a solid nodule or wall excrescence.

3D ultrasonography

As the use of 3D ultrasonography increases, studies are yielding different results as to its utility in describing ovarian masses. 3D ultrasonography may be useful in finding centrally located vessels so that Doppler can be applied.32

OTHER IMAGING

Although ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice in the evaluation of adnexal masses owing to its high sensitivity, availability, and low cost, studies have shown that up to 20% of adnexal masses can be reported as indeterminate by ultrasonography (Table 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as a very valuable tool when ultrasonography is inconclusive or limited.35 Although MRI is very accurate (Table 1), it is not considered a first-line imaging test because it is more expensive, less available, and more inconvenient for the patient than ultrasonography.

MRI provides additional information on the composition of soft-tissue tumors. Usually, MRI is ordered with contrast, unless there are contraindications to it. The radiologist will evaluate morphologic features, signal intensity, and enhancement of solid areas. Techniques such as dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (following the distribution of contrast material over time), in- and out-of-phase T1 imaging (looking for fat, such as in dermoids), and the newer diffusion-weighted imaging may further improve characterization.

In one study of MRI as second-line imaging, contrast-enhanced MRI contributed to a greater change in the probability of ovarian cancer than did CT, Doppler ultrasonography, or MRI without contrast.36 This may result in a reduction in unnecessary surgeries and in an increase in proper referrals in cases of suspected malignancy.

Computed tomography

Disadvantages of CT include radiation exposure and poor discrimination of soft tissue. It can, however, differentiate fat or calcifications that may be found in dermoids. While CT is not often used to describe an ovarian lesion, it may be used preoperatively to stage an ovarian cancer or to look for a primary intra-abdominal cancer when an ovarian mass may represent metastasis.32

MANAGING AN INCIDENTAL OVARIAN CYST OR CYSTIC MASS

Combining information from the history, physical examination, imaging, and blood work to assign a level of risk of malignancy is not straightforward. The clinician must weigh several imperfect tests, each with its own sensitivity and specificity, against the background of the individual patient’s likelihood of malignancy. Whereas a 4-cm simple cyst in a premenopausal woman can be assigned to a low-risk category and a complex mass with flow to a solid component in a postmenopausal woman can be assigned to a high-risk category, many lesions are more difficult to assess.

Several systems have been proposed for analyzing data and standardizing risk assessment. There are a number of scoring systems based on ultrasonographic morphology and several mathematical regression models that include menopausal status and tumor markers. But each has drawbacks, and none is definitively superior to expert opinion.16,17,37,38

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis39 calculated sensitivity and specificity for several imaging tests, scoring systems, and blood tumor markers. Some results are presented in Table 1.

The management of an ovarian cyst depends on symptoms, likelihood of torsion or rupture, and the level of concern for malignancy. At the lower-risk end of the spectrum, reassurance or observation over time may be appropriate. A general gynecologist can evaluate indeterminate or symptomatic ovarian cysts. Patients with masses frankly suspicious for malignancy are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

Expectant management for low-risk lesions

Low-risk lesions such as simple cysts, endometriomas, and dermoids have a less than 1% chance of malignancy. Most patients who have them require only reassurance or follow-up with serial ultrasonography. Oral contraceptives may prevent new cysts from forming. Aspiration is not recommended.

In 2010, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound issued a consensus statement regarding re-imaging of simple ovarian cysts.33

In premenopausal women, they recommend no further testing for cysts 5 cm or smaller, yearly follow-up for cysts larger than 5 cm and up to and including 7 cm, and MRI or surgical evaluation for cysts larger than 7 cm, as it is difficult to completely image a large cyst with ultrasonography.

In postmenopausal women, if the cyst is 1 cm in diameter or smaller, no further studies need to be done. For simple cysts larger than 1 cm and up to and including 7 cm, yearly re-imaging is recommended. And for cysts larger than 7 cm, MRI or surgery is indicated. The American College of Radiology recommends repeat ultrasonography and CA125 testing for cysts 3 cm and larger but doesn’t specify an interval.32

A cyst that is otherwise simple but has a single thin septation (< 3 mm) or a small calcification in the wall is almost always benign. Such a cyst should be followed as if it were a simple cyst, as indicated by patient age and cyst size.

There are no official guidelines as to when to stop serial imaging,22,32 but a recent paper suggested one or two ultrasonographic examinations to confirm size and morphologic stability.19 Once a lesion has resolved, there is no need for further imaging (Figures 1–3).

Birth control pills for suppression of new cysts. Oral contraceptives do not hasten the resolution of ovarian cysts, according to a 2011 Cochrane review.40 Some practitioners will, nevertheless, prescribe them in an attempt to prevent new cysts from confusing the picture.

Aspiration is not recommended for either diagnosis or treatment. It can only be considered in patients at high risk who are not surgical candidates. Results of cytologic study of specimens obtained by fine-needle aspiration cannot reliably determine the presence or absence of malignancy.41 There is also a theoretical risk of spreading cancer from an early-stage lesion. A retrospective study has suggested that spillage of cyst contents during surgery in early ovarian cancer is associated with a worse prognosis.42

From a therapeutic point of view, studies have shown the same resolution rate at 6 months for aspirated cysts vs those followed expectantly.43 Another study found a recurrence rate of 25% within 1 year of aspiration.44

Referral for medium-risk or indeterminant-risk ovarian masses

Patients who have medium- or indeterminaterisk ovarian masses (Table 3) should be referred to a gynecologist. Further testing will help stratify the risk of malignancy. This can include tumor marker blood tests, MRI, or CT, the addition of Doppler or 3D ultrasonography, serial ultrasonography, or surgical exploration.

If repeat ultrasonography is chosen, the interval will likely be 6 to 12 weeks. Surgery may consist of removing only the cyst itself, or the whole ovary with or without the tube, or sometimes both ovaries. Purely diagnostic laparoscopy is rarely performed, as direct visualization of a lesion is rarely helpful. Frozen section should be employed, and the operating gynecologist should have oncologic backup, since the surgery is performed to rule out malignancy.

In the case of a benign-appearing cyst larger than 6 cm, thought must be given as to whether it is likely to rupture or twist. Rupture of a large cyst can lead to pain and in some cases to hemorrhage. Contents of a ruptured dermoid cyst can cause chemical peritonitis. Torsion of an ovary can result in loss of the ovary through compromised perfusion. A general gynecologist can decide with the patient whether preemptive surgery is indicated.

Operative evaluation for high-risk masses

Patients with high-risk ovarian masses (Table 4) are best referred to a gynecologic oncologist for operative evaluation. If features are seen that indicate malignancy, such as thick septations, solid areas with blood flow, ascites, or other pelvic masses, surgery is indicated. The surgical approach may be through laparoscopy or laparotomy.45 It should be noted that even in the face of worrisome features on ultrasonography, many masses turn out to be benign.

In 2011, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology issued new guidelines recommending oncologic referral of patients with high-risk masses. Elevated CA125, ascites, a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, or evidence of metastasis in postmenopausal women requires oncologic evaluation.26 For premenopausal women, a very elevated CA125, ascites, or metastasis requires referral (Table 4).26

Direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist is underutilized. A recent study found that fewer than half of primary care physicians said that they would refer a classic suspicious case directly to a subspecialist.46 It is estimated that only 33% of ovarian cancers are first operated on by a gynecologic oncologist.47

A 2011 Cochrane review confirmed a survival benefit for women with cancer who are operated on by gynecologic oncologists primarily, rather than by a general gynecologist and then referred.48 A gynecologic oncologist is most likely to perform proper staging and debulking at the time of initial diagnosis.49

Special situations require consultation

Ovarian cysts in pregnancy are most often benign,50 but malignancy is always a possibility. Functional cysts and dermoids are the most common. These may remain asymptomatic or may rupture or twist or cause difficulty with delivering the baby. Surgical intervention, if needed, should be performed in the second trimester if possible. A multidisciplinary approach and referral to a perinatologist and gynecologic oncologist are advised.

Symptomatic ovarian cysts that may need surgical intervention are the purview of the general gynecologist. If the risk of a surgical emergency is judged to be low, a symptomatic patient may be supported with pain medication and may be managed on an outpatient basis. Immediate surgical consultation is appropriate if the patient appears toxic or in shock. Depending on the clinical picture, there may be a ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, ruptured hemorrhagic cyst, or ovarian torsion, any of which may need immediate surgical intervention.

If a symptomatic mass is highly suspicious for cancer, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted directly.

WHEN TO REASSURE, REASSESS, REFER

Ovarian masses often pose diagnostic and management dilemmas. Reassurance can be offered to women with small simple cysts. Interval follow-up with ultrasonography is appropriate for cysts that are most likely to be benign. If malignancy is suspected based on ultrasonography, other imaging, blood testing, or expert opinion, referral to a surgical gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist is recommended. If malignancy is strongly suspected, direct referral to a gynecologic oncologist offers the best chance of survival if cancer is actually present.

Reassure

- When simple cysts are less than 1 cm in postmenopausal women

- When simple cysts are less than 5 cm in premenopausal patients.

Reassess

- With yearly ultrasonography in cases of very low risk

- With repeat ultrasonography in 6 to 12 weeks when the diagnosis is not clear but the cyst is likely benign.

Refer

- To a gynecologist for symptomatic cysts, cysts larger than 6 cm, and cysts that require ancillary testing

- To a gynecologic oncologist for findings worrisome for cancer, such as thick septations, solid areas with flow, ascites, evidence of metastasis, or high cancer antigen 125 levels.

Ovarian cysts, sometimes reported as ovarian masses or adnexal masses, are frequently found incidentally in women who have no symptoms. These cysts can be physiologic (having to do with ovulation) or neoplastic—either benign, borderline (having low malignant potential), or frankly malignant. Thus, these incidental lesions pose many diagnostic challenges to the clinician.

The vast majority of cysts are benign, but a few are malignant, and ovarian malignancies have a notoriously poor survival rate. The diagnosis can only be obtained surgically, as aspiration and biopsy are not definitive and may be harmful. Therefore, the clinician must try to balance the risks of surgery for what may be a benign lesion with the risk of delaying diagnosis of a malignancy.

In this article we provide an approach to evaluating these cysts, with guidance on when the patient can be reassured and when referral is needed.

THE DILEMMA OF OVARIAN CYSTS

Ovarian cysts are common

Premenopausal women can be expected to make at least a small cyst or follicle almost every month. The point prevalence for significant cysts has been reported to be almost 8% in premenopausal women.1

Surprisingly, the prevalence in postmenopausal women is as high as 14% to 18%, with a yearly incidence of 8%. From 30% to 54% of postmenopausal ovarian cysts persist for years.2,3

Little is known about the cause of most cysts

Little is known about the cause of most ovarian cysts. Functional or physiologic cysts are thought to be variations in the ovulatory process. They do not seem to be precursors to ovarian cancer.

Most benign neoplastic cysts are also not thought to be precancerous, with the possible exception of the mucinous kind.4 Ovarian cysts do not increase the risk of ovarian cancer later in life,3,9 and removing benign cysts has not been shown to decrease the risk of death from ovarian cancer.10

Most ovarian cysts and masses are benign

Simple ovarian cysts are much more likely to be benign than malignant. Complex and solid ovarian masses are also more likely to be benign, regardless of menopausal status, but more malignancies are found in this group.

With any kind of mass, the chances of malignancy increase with age. Children and adolescents are not discussed in this article; they should be referred to a specialist.

Ovarian cancer often has a poor prognosis

This “silent” cancer is most often discovered and treated when it has already spread, contributing to a reported 5-year survival rate of only 33% to 46%.11–13 Ideally, ovarian cancer would be found and removed while still confined to the ovary, when the 5-year survival rate is greater than 90%.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a precursor lesion for most ovarian cancers, and there is no good way of finding it in the stage 1 phase, so detecting this cancer before it spreads remains an elusive goal.11,14

Surgery is required to diagnose difficult cases

There is no perfect test for the preoperative assessment of a cystic ovarian mass. Every method has drawbacks (Table 1).15–18 Therefore, the National Institutes of Health estimates that 5% to 10% of women in the United States will undergo surgical exploration for an ovarian cyst in their lifetime. Only 13% to 21% of these cysts will be malignant.5

ASSESSING AN INCIDENTALLY DISCOVERED OVARIAN MASS

Certain factors in the history, physical examination, and blood work may suggest the cyst is either benign or malignant and may influence the subsequent assessment. However, in most cases, the best next step is to perform transvaginal ultrasonography, which we will discuss later in this paper.

History

Age is a major risk factor for ovarian cancer; the median age at diagnosis is 63 years.9 In the reproductive-age group, ovarian cysts are much more likely to be functional than neoplastic. Epithelial cancers are rare before the age of 40, but other cancer types such as borderline, germ cell, and sex cord stromal tumors may occur.19

In every age group a cyst is more likely to be benign than malignant, although, as noted above, the probability of malignancy increases with age.

Symptoms. Most ovarian cysts, benign or malignant, are asymptomatic and are found only incidentally.

The most commonly reported symptoms are pelvic or lower-abdominal pressure or pain. Acutely painful conditions include ovarian torsion, hemorrhage into the cyst, cyst rupture with or without intra-abdominal hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease with tubo-ovarian abscess.

Some patients who have ovarian cancer report vague symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency, abdominal distention or bloating, and difficulty eating or early satiety.20 Although the positive predictive value of this symptom constellation is only about 1%, its usefulness increases if these symptoms arose recently (within the past year) and occur than 12 days a month.21

Family history of ovarian, breast, endometrial, or colon cancer is of particular interest. The greater the number of affected relatives and the closer the degree of relation, the greater the risk; in some cases the relative risk is 40 times greater.22 Breast-ovarian cancer syndromes, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, and family cancer syndrome, as well as extremely high-risk pedigrees such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome, all place women at significantly higher risk. Daughters tend to develop cancer at a younger age than their affected mothers.

However, only 10% of ovarian cancers occur in patients who have a family history of it, leaving 90% as sporadic occurrences.

Other history. Factors protective against ovarian cancer include use of oral contraceptives at any time, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, having had children, breastfeeding, a low-fat diet, and possibly use of aspirin and acetaminophen.23,24