User login

Simultaneous Bilateral Functional Radiography in Ulnar Collateral Ligament Lesion of the Thumb: An Original Technique

Gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is caused by an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. The mechanism of injury is forced radial and palmar abduction and hyperextension.

This lesion was initially described in 1955 by Campbell.1 It occurred in gamekeepers who worked in preserves in Scotland. The UCL was injured because of the way they killed rabbits—hence, gamekeeper’s thumb. Now these injuries are more common in skiers—skier’s thumb. In skiers, the mechanism of injury is the force exerted by the ski pole strap on the thumb during a fall. This injury is also seen in breakdancers.1,2

Different lesions can result, the most common being that of the UCL. The UCL lesion may be partial, with no joint instability,3,4 or total, with instability and subdislocation of the proximal phalanx.5-9 Rupture of the thumb adductor aponeurosis and displacement of the long extensor have been described as the cause of thumb instability.6-8

UCL rupture can occur in its extension or can cause a fracture-tearing in the proximal phalanx.9-12 Intra-articular fractures are sometimes found. The essential problem in UCL injuries is the impossibility of spontaneous healing once the rupture is complete, because of the Stener effect. (When the UCL ruptures, its proximal part retracts and runs above the fibrous expansion of the adductor muscle, which is interposed between the 2 parts of the ruptured UCL and prevents healing, even if the thumb is immobilized.) In these cases, only surgery can repair the lesion.2

In any thumb injury, particularly one caused by hyperabduction, a UCL lesion should be considered. The main problem is diagnosing sprain severity, which is evidenced by the degree of joint hypermobility. Radiologic examination should be performed in all cases to rule out fracture with tear, posterior capsular tear, palmar plate tear, and palmar subdislocation of the proximal phalanx, all of which are associated with UCL tearing.7-9

If the diagnosis is suspected, and radiographs show no fracture, comparative radiographs should be obtained in forced valgus.

Technique

We report on a simple, reliable, reproducible method that allows the patient’s thumbs to be compared, under the same force application conditions, on a single radiograph. This technique reduces the patient’s and examiner’s exposure to x-rays and is well tolerated by the patient. Anesthesia for the thumb is usually not necessary.

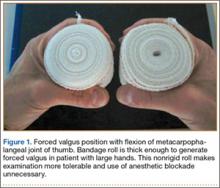

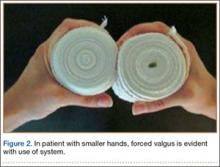

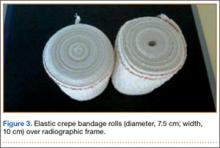

In each hand, the patient holds a cylindrical object, such as a drinking glass (standard diameter, 7.5-8.5 cm). We use an elastic crepe bandage roll (diameter, 7.5 cm; width, 10 cm). This roll is common in emergency departments (EDs) and easily accessible. The patient holds the rolls in his or her hands with the thumbs in the posteroanterior position (Figures 1–3) and places himself or herself on a 18×24-cm frame or directly on the radiography table.

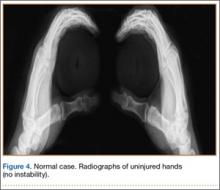

Both thumbs are captured on a single functional radiograph for comparison of forced valgus of the MCP joints, as in our example cases. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Control Case

The single functional radiograph of both thumbs showed no evidence of joint laxity on the valgus stress test (Figure 4).

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman landed on her left hand when she fell backward while supporting the hand on a piece of furniture. She presented to the ED with pain in the region of the thumb and thenar eminence. Posteroanterior and lateral radiograph projections showed no significant bone injury (Figure 5). Given the patient’s persistent pain, the traumatologist suspected damage to the thumb UCL, so a simultaneous bilateral functional radiographic projection was obtained. The projection showed joint laxity, implying damage to the thumb UCL. Repair and reinsertion of the UCL were performed using a bone harpoon suture.

Case 2

A 58-year-old man sustained a left hand injury when, using both hands, he tried to catch hold of a falling wooden plank. When he presented to the ED the following week, he was given a diagnosis of thumb contusion and forced hyperabduction and was wearing a metal strap for immobilization. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 6). Thumb UCL injury was suspected on the basis of the physical examination findings and the mechanism of injury. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed significant joint laxity. Surgical treatment with the pull-out technique was performed.

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman experienced forced traction from a dog leash and presented to the ED with pain in the right thumb region. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 7). Thumb UCL injury was suspected. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed slight joint laxity, a sprain was diagnosed, and plaster bandaging was applied. Figures 8A–8D show the accurate thumb positions for performing the functional radiograph in forced valgus. We call the technique J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection.

Discussion

Examination using the stress test to cause joint tilt is crucial in making an accurate diagnosis and deciding on the most appropriate therapeutic approach.10 Most authors accept that surgical management is required in joint tilts over 30º, as these involve complete UCL rupture.10-12

The MCP joint must be examined in flexion, when the main fascicle of the UCL is tight, and not in extension, when the main fascicle of the UCL is relaxed. If we examine the thumb in extension, radial deviations may occur that are not caused by joint instability. Tilt here must be compared with that of the healthy side.11

Early diagnosis and adequate management are essential, as unnoticed or undervalued injuries can progress to painful sequelae, associated with stiffness, instability, and osteoarthritis, with evident harm to the grip and pinch functions of the hand. In many cases, clinical evidence of MCP joint instability is difficult. The radiologic diagnosis is usually obtained with comparative radiographs in forced valgus of both thumbs.

The forced valgus maneuver typically is performed by the examiner, who must stay with the patient in the radiography room and wear radiologic protection. Incredibly, some patients must force the valgus themselves.

The maneuver we have described clearly has complications, as it is painful, and some patients are uncooperative. Usually the thumb is anesthetized, and the examiner assumes the exposure to x-rays. The valgus deviation force that can be applied during stability testing may lead to further disruption of a partially torn ligament or displacement of a ruptured ligament if the overforced maneuver is performed.13,14 That does not occur with our technique. On the other hand, the forces applied to the thumbs must be symmetrical for comparison purposes. The way to prevent these inconveniences is to perform the forced valgus maneuver over both thumbs simultaneously, under the same force application conditions and on a single radiograph, without requiring the examiner to remain with the patient in the radiography room.

Heim15 designed a system for simultaneous functional radiographs, but an apparatus must be built to adapt it to the frame of the radiography table, and the technique involves hyperpronating both hands and bandaging them to the forearm—which is uncomfortable and bothersome for patients and, in our opinion, has a poor application in high-volume EDs.

The technique of having the patient hold a bandage roll (J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection) offers several advantages:

1. The thumb can be placed in flexion, tightening the main fascicle of the UCL, which is how the UCL must be examined.

2. Forced valgus is allowed. Holding a water glass involves opening the thumb and the necessary stability of the MCP joint of the thumb (grip function of thumb); this radiographic technique is functional.

3. The examiner need not stay with the patient in the radiography room or be exposed to x-rays.

4. The bandage roll is thick enough to generate forced valgus in a patient with large hands. The nonrigid roll makes the examination more tolerable and avoids overforced valgus, eliminating the need for anesthetic blockade.

5. The technique is accessible and simple. In fact, there is no need to remove the roll from its wrapping.

1. Campbell CS. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1955;37(1):148-149.

2. Stener B. Displacement of the ruptured ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: a clinical and anatomic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44(4):869-879.

3. Stener B. Hyperextension injuries to the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: rupture of ligaments, fracture of sesamoid bones, rupture of flexor pollicis brevis. An anatomical and clinical study. Acta Chir Scand. 1963;125:275-293.

4. Coonrad RW, Goldner JL. A study of the pathological findings and treatment in soft-tissue injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. With a clinical study of the normal range of motion in one thousand thumbs and a study of post mortem findings of ligamentous structures in relation to function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(3):439-451.

5. Parikh M, Nahigian S, Froimson A. Gamekeeper’s thumb. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(1):24-31.

6. Kaplan EB. The pathology and treatment of radial subluxation of the thumb with ulnar displacement of the head of the first metacarpal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43:541-546.

7. Yamanaka K, Yoshida K, Inoue H, Inoue A, Miyagi T. Locking of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(5):782-787.

8. Sennwald G, Segmüller G, Egli A. The late reconstruction of the ligament of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb [in English, French]. Ann Chir Main. 1987;6(1):15-24.

9. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

10. Louis DS, Huebner JJ Jr, Hankin FM. Rupture and displacement of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Preoperative diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(9):1320-1326.

11. Heyman P, Gelberman RH, Duncan K, Hipp JA. Injuries of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Biomechanical and prospective clinical studies on the usefulness of valgus stress testing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):165-171.

12. Ritting AW, Baldwin PC, Rodner CM. Ulnar collateral ligament injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(2):106-112.

13. Cooper JG, Johnstone AJ, Hider P, Ardagh MW. Local anaesthetic infiltration increases the accuracy of assessment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(2):132-136.

14. Noszian IM, Dinkhauser LM, Straub GM, Orthner E. Ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb. Dislocation caused by stress radiography in 2 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66(2):156-157.

15. Heim U. Simultaneous functional bilateral radiographies of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb in hyper-pronation [in French]. Ann Chir Main. 1982;1(2):183-186.

Gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is caused by an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. The mechanism of injury is forced radial and palmar abduction and hyperextension.

This lesion was initially described in 1955 by Campbell.1 It occurred in gamekeepers who worked in preserves in Scotland. The UCL was injured because of the way they killed rabbits—hence, gamekeeper’s thumb. Now these injuries are more common in skiers—skier’s thumb. In skiers, the mechanism of injury is the force exerted by the ski pole strap on the thumb during a fall. This injury is also seen in breakdancers.1,2

Different lesions can result, the most common being that of the UCL. The UCL lesion may be partial, with no joint instability,3,4 or total, with instability and subdislocation of the proximal phalanx.5-9 Rupture of the thumb adductor aponeurosis and displacement of the long extensor have been described as the cause of thumb instability.6-8

UCL rupture can occur in its extension or can cause a fracture-tearing in the proximal phalanx.9-12 Intra-articular fractures are sometimes found. The essential problem in UCL injuries is the impossibility of spontaneous healing once the rupture is complete, because of the Stener effect. (When the UCL ruptures, its proximal part retracts and runs above the fibrous expansion of the adductor muscle, which is interposed between the 2 parts of the ruptured UCL and prevents healing, even if the thumb is immobilized.) In these cases, only surgery can repair the lesion.2

In any thumb injury, particularly one caused by hyperabduction, a UCL lesion should be considered. The main problem is diagnosing sprain severity, which is evidenced by the degree of joint hypermobility. Radiologic examination should be performed in all cases to rule out fracture with tear, posterior capsular tear, palmar plate tear, and palmar subdislocation of the proximal phalanx, all of which are associated with UCL tearing.7-9

If the diagnosis is suspected, and radiographs show no fracture, comparative radiographs should be obtained in forced valgus.

Technique

We report on a simple, reliable, reproducible method that allows the patient’s thumbs to be compared, under the same force application conditions, on a single radiograph. This technique reduces the patient’s and examiner’s exposure to x-rays and is well tolerated by the patient. Anesthesia for the thumb is usually not necessary.

In each hand, the patient holds a cylindrical object, such as a drinking glass (standard diameter, 7.5-8.5 cm). We use an elastic crepe bandage roll (diameter, 7.5 cm; width, 10 cm). This roll is common in emergency departments (EDs) and easily accessible. The patient holds the rolls in his or her hands with the thumbs in the posteroanterior position (Figures 1–3) and places himself or herself on a 18×24-cm frame or directly on the radiography table.

Both thumbs are captured on a single functional radiograph for comparison of forced valgus of the MCP joints, as in our example cases. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Control Case

The single functional radiograph of both thumbs showed no evidence of joint laxity on the valgus stress test (Figure 4).

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman landed on her left hand when she fell backward while supporting the hand on a piece of furniture. She presented to the ED with pain in the region of the thumb and thenar eminence. Posteroanterior and lateral radiograph projections showed no significant bone injury (Figure 5). Given the patient’s persistent pain, the traumatologist suspected damage to the thumb UCL, so a simultaneous bilateral functional radiographic projection was obtained. The projection showed joint laxity, implying damage to the thumb UCL. Repair and reinsertion of the UCL were performed using a bone harpoon suture.

Case 2

A 58-year-old man sustained a left hand injury when, using both hands, he tried to catch hold of a falling wooden plank. When he presented to the ED the following week, he was given a diagnosis of thumb contusion and forced hyperabduction and was wearing a metal strap for immobilization. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 6). Thumb UCL injury was suspected on the basis of the physical examination findings and the mechanism of injury. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed significant joint laxity. Surgical treatment with the pull-out technique was performed.

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman experienced forced traction from a dog leash and presented to the ED with pain in the right thumb region. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 7). Thumb UCL injury was suspected. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed slight joint laxity, a sprain was diagnosed, and plaster bandaging was applied. Figures 8A–8D show the accurate thumb positions for performing the functional radiograph in forced valgus. We call the technique J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection.

Discussion

Examination using the stress test to cause joint tilt is crucial in making an accurate diagnosis and deciding on the most appropriate therapeutic approach.10 Most authors accept that surgical management is required in joint tilts over 30º, as these involve complete UCL rupture.10-12

The MCP joint must be examined in flexion, when the main fascicle of the UCL is tight, and not in extension, when the main fascicle of the UCL is relaxed. If we examine the thumb in extension, radial deviations may occur that are not caused by joint instability. Tilt here must be compared with that of the healthy side.11

Early diagnosis and adequate management are essential, as unnoticed or undervalued injuries can progress to painful sequelae, associated with stiffness, instability, and osteoarthritis, with evident harm to the grip and pinch functions of the hand. In many cases, clinical evidence of MCP joint instability is difficult. The radiologic diagnosis is usually obtained with comparative radiographs in forced valgus of both thumbs.

The forced valgus maneuver typically is performed by the examiner, who must stay with the patient in the radiography room and wear radiologic protection. Incredibly, some patients must force the valgus themselves.

The maneuver we have described clearly has complications, as it is painful, and some patients are uncooperative. Usually the thumb is anesthetized, and the examiner assumes the exposure to x-rays. The valgus deviation force that can be applied during stability testing may lead to further disruption of a partially torn ligament or displacement of a ruptured ligament if the overforced maneuver is performed.13,14 That does not occur with our technique. On the other hand, the forces applied to the thumbs must be symmetrical for comparison purposes. The way to prevent these inconveniences is to perform the forced valgus maneuver over both thumbs simultaneously, under the same force application conditions and on a single radiograph, without requiring the examiner to remain with the patient in the radiography room.

Heim15 designed a system for simultaneous functional radiographs, but an apparatus must be built to adapt it to the frame of the radiography table, and the technique involves hyperpronating both hands and bandaging them to the forearm—which is uncomfortable and bothersome for patients and, in our opinion, has a poor application in high-volume EDs.

The technique of having the patient hold a bandage roll (J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection) offers several advantages:

1. The thumb can be placed in flexion, tightening the main fascicle of the UCL, which is how the UCL must be examined.

2. Forced valgus is allowed. Holding a water glass involves opening the thumb and the necessary stability of the MCP joint of the thumb (grip function of thumb); this radiographic technique is functional.

3. The examiner need not stay with the patient in the radiography room or be exposed to x-rays.

4. The bandage roll is thick enough to generate forced valgus in a patient with large hands. The nonrigid roll makes the examination more tolerable and avoids overforced valgus, eliminating the need for anesthetic blockade.

5. The technique is accessible and simple. In fact, there is no need to remove the roll from its wrapping.

Gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is caused by an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. The mechanism of injury is forced radial and palmar abduction and hyperextension.

This lesion was initially described in 1955 by Campbell.1 It occurred in gamekeepers who worked in preserves in Scotland. The UCL was injured because of the way they killed rabbits—hence, gamekeeper’s thumb. Now these injuries are more common in skiers—skier’s thumb. In skiers, the mechanism of injury is the force exerted by the ski pole strap on the thumb during a fall. This injury is also seen in breakdancers.1,2

Different lesions can result, the most common being that of the UCL. The UCL lesion may be partial, with no joint instability,3,4 or total, with instability and subdislocation of the proximal phalanx.5-9 Rupture of the thumb adductor aponeurosis and displacement of the long extensor have been described as the cause of thumb instability.6-8

UCL rupture can occur in its extension or can cause a fracture-tearing in the proximal phalanx.9-12 Intra-articular fractures are sometimes found. The essential problem in UCL injuries is the impossibility of spontaneous healing once the rupture is complete, because of the Stener effect. (When the UCL ruptures, its proximal part retracts and runs above the fibrous expansion of the adductor muscle, which is interposed between the 2 parts of the ruptured UCL and prevents healing, even if the thumb is immobilized.) In these cases, only surgery can repair the lesion.2

In any thumb injury, particularly one caused by hyperabduction, a UCL lesion should be considered. The main problem is diagnosing sprain severity, which is evidenced by the degree of joint hypermobility. Radiologic examination should be performed in all cases to rule out fracture with tear, posterior capsular tear, palmar plate tear, and palmar subdislocation of the proximal phalanx, all of which are associated with UCL tearing.7-9

If the diagnosis is suspected, and radiographs show no fracture, comparative radiographs should be obtained in forced valgus.

Technique

We report on a simple, reliable, reproducible method that allows the patient’s thumbs to be compared, under the same force application conditions, on a single radiograph. This technique reduces the patient’s and examiner’s exposure to x-rays and is well tolerated by the patient. Anesthesia for the thumb is usually not necessary.

In each hand, the patient holds a cylindrical object, such as a drinking glass (standard diameter, 7.5-8.5 cm). We use an elastic crepe bandage roll (diameter, 7.5 cm; width, 10 cm). This roll is common in emergency departments (EDs) and easily accessible. The patient holds the rolls in his or her hands with the thumbs in the posteroanterior position (Figures 1–3) and places himself or herself on a 18×24-cm frame or directly on the radiography table.

Both thumbs are captured on a single functional radiograph for comparison of forced valgus of the MCP joints, as in our example cases. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Control Case

The single functional radiograph of both thumbs showed no evidence of joint laxity on the valgus stress test (Figure 4).

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman landed on her left hand when she fell backward while supporting the hand on a piece of furniture. She presented to the ED with pain in the region of the thumb and thenar eminence. Posteroanterior and lateral radiograph projections showed no significant bone injury (Figure 5). Given the patient’s persistent pain, the traumatologist suspected damage to the thumb UCL, so a simultaneous bilateral functional radiographic projection was obtained. The projection showed joint laxity, implying damage to the thumb UCL. Repair and reinsertion of the UCL were performed using a bone harpoon suture.

Case 2

A 58-year-old man sustained a left hand injury when, using both hands, he tried to catch hold of a falling wooden plank. When he presented to the ED the following week, he was given a diagnosis of thumb contusion and forced hyperabduction and was wearing a metal strap for immobilization. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 6). Thumb UCL injury was suspected on the basis of the physical examination findings and the mechanism of injury. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed significant joint laxity. Surgical treatment with the pull-out technique was performed.

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman experienced forced traction from a dog leash and presented to the ED with pain in the right thumb region. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 7). Thumb UCL injury was suspected. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed slight joint laxity, a sprain was diagnosed, and plaster bandaging was applied. Figures 8A–8D show the accurate thumb positions for performing the functional radiograph in forced valgus. We call the technique J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection.

Discussion

Examination using the stress test to cause joint tilt is crucial in making an accurate diagnosis and deciding on the most appropriate therapeutic approach.10 Most authors accept that surgical management is required in joint tilts over 30º, as these involve complete UCL rupture.10-12

The MCP joint must be examined in flexion, when the main fascicle of the UCL is tight, and not in extension, when the main fascicle of the UCL is relaxed. If we examine the thumb in extension, radial deviations may occur that are not caused by joint instability. Tilt here must be compared with that of the healthy side.11

Early diagnosis and adequate management are essential, as unnoticed or undervalued injuries can progress to painful sequelae, associated with stiffness, instability, and osteoarthritis, with evident harm to the grip and pinch functions of the hand. In many cases, clinical evidence of MCP joint instability is difficult. The radiologic diagnosis is usually obtained with comparative radiographs in forced valgus of both thumbs.

The forced valgus maneuver typically is performed by the examiner, who must stay with the patient in the radiography room and wear radiologic protection. Incredibly, some patients must force the valgus themselves.

The maneuver we have described clearly has complications, as it is painful, and some patients are uncooperative. Usually the thumb is anesthetized, and the examiner assumes the exposure to x-rays. The valgus deviation force that can be applied during stability testing may lead to further disruption of a partially torn ligament or displacement of a ruptured ligament if the overforced maneuver is performed.13,14 That does not occur with our technique. On the other hand, the forces applied to the thumbs must be symmetrical for comparison purposes. The way to prevent these inconveniences is to perform the forced valgus maneuver over both thumbs simultaneously, under the same force application conditions and on a single radiograph, without requiring the examiner to remain with the patient in the radiography room.

Heim15 designed a system for simultaneous functional radiographs, but an apparatus must be built to adapt it to the frame of the radiography table, and the technique involves hyperpronating both hands and bandaging them to the forearm—which is uncomfortable and bothersome for patients and, in our opinion, has a poor application in high-volume EDs.

The technique of having the patient hold a bandage roll (J.J.’s thumb radiographic projection) offers several advantages:

1. The thumb can be placed in flexion, tightening the main fascicle of the UCL, which is how the UCL must be examined.

2. Forced valgus is allowed. Holding a water glass involves opening the thumb and the necessary stability of the MCP joint of the thumb (grip function of thumb); this radiographic technique is functional.

3. The examiner need not stay with the patient in the radiography room or be exposed to x-rays.

4. The bandage roll is thick enough to generate forced valgus in a patient with large hands. The nonrigid roll makes the examination more tolerable and avoids overforced valgus, eliminating the need for anesthetic blockade.

5. The technique is accessible and simple. In fact, there is no need to remove the roll from its wrapping.

1. Campbell CS. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1955;37(1):148-149.

2. Stener B. Displacement of the ruptured ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: a clinical and anatomic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44(4):869-879.

3. Stener B. Hyperextension injuries to the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: rupture of ligaments, fracture of sesamoid bones, rupture of flexor pollicis brevis. An anatomical and clinical study. Acta Chir Scand. 1963;125:275-293.

4. Coonrad RW, Goldner JL. A study of the pathological findings and treatment in soft-tissue injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. With a clinical study of the normal range of motion in one thousand thumbs and a study of post mortem findings of ligamentous structures in relation to function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(3):439-451.

5. Parikh M, Nahigian S, Froimson A. Gamekeeper’s thumb. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(1):24-31.

6. Kaplan EB. The pathology and treatment of radial subluxation of the thumb with ulnar displacement of the head of the first metacarpal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43:541-546.

7. Yamanaka K, Yoshida K, Inoue H, Inoue A, Miyagi T. Locking of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(5):782-787.

8. Sennwald G, Segmüller G, Egli A. The late reconstruction of the ligament of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb [in English, French]. Ann Chir Main. 1987;6(1):15-24.

9. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

10. Louis DS, Huebner JJ Jr, Hankin FM. Rupture and displacement of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Preoperative diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(9):1320-1326.

11. Heyman P, Gelberman RH, Duncan K, Hipp JA. Injuries of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Biomechanical and prospective clinical studies on the usefulness of valgus stress testing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):165-171.

12. Ritting AW, Baldwin PC, Rodner CM. Ulnar collateral ligament injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(2):106-112.

13. Cooper JG, Johnstone AJ, Hider P, Ardagh MW. Local anaesthetic infiltration increases the accuracy of assessment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(2):132-136.

14. Noszian IM, Dinkhauser LM, Straub GM, Orthner E. Ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb. Dislocation caused by stress radiography in 2 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66(2):156-157.

15. Heim U. Simultaneous functional bilateral radiographies of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb in hyper-pronation [in French]. Ann Chir Main. 1982;1(2):183-186.

1. Campbell CS. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1955;37(1):148-149.

2. Stener B. Displacement of the ruptured ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: a clinical and anatomic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44(4):869-879.

3. Stener B. Hyperextension injuries to the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb: rupture of ligaments, fracture of sesamoid bones, rupture of flexor pollicis brevis. An anatomical and clinical study. Acta Chir Scand. 1963;125:275-293.

4. Coonrad RW, Goldner JL. A study of the pathological findings and treatment in soft-tissue injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. With a clinical study of the normal range of motion in one thousand thumbs and a study of post mortem findings of ligamentous structures in relation to function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(3):439-451.

5. Parikh M, Nahigian S, Froimson A. Gamekeeper’s thumb. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(1):24-31.

6. Kaplan EB. The pathology and treatment of radial subluxation of the thumb with ulnar displacement of the head of the first metacarpal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43:541-546.

7. Yamanaka K, Yoshida K, Inoue H, Inoue A, Miyagi T. Locking of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(5):782-787.

8. Sennwald G, Segmüller G, Egli A. The late reconstruction of the ligament of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb [in English, French]. Ann Chir Main. 1987;6(1):15-24.

9. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

10. Louis DS, Huebner JJ Jr, Hankin FM. Rupture and displacement of the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Preoperative diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(9):1320-1326.

11. Heyman P, Gelberman RH, Duncan K, Hipp JA. Injuries of the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Biomechanical and prospective clinical studies on the usefulness of valgus stress testing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):165-171.

12. Ritting AW, Baldwin PC, Rodner CM. Ulnar collateral ligament injury of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(2):106-112.

13. Cooper JG, Johnstone AJ, Hider P, Ardagh MW. Local anaesthetic infiltration increases the accuracy of assessment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(2):132-136.

14. Noszian IM, Dinkhauser LM, Straub GM, Orthner E. Ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb. Dislocation caused by stress radiography in 2 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66(2):156-157.

15. Heim U. Simultaneous functional bilateral radiographies of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb in hyper-pronation [in French]. Ann Chir Main. 1982;1(2):183-186.

ICM exposure associated with higher risk of thyroid dysfunction

After adjusting for variables, patients with iodinated contrast media (ICM) exposure had a significantly higher risk of thyroid dysfunction (hazard ratio, 1.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.66), compared with that of patients in the non-ICM exposure group, wrote the authors of a newly published study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Lead author Dr. Edy Kornelius and associates examined 19,642 cases and 78,568 matched controls, recruited from the general population in Taiwan, in a 6-year cohort study. A total of 383 ICM-exposed patients had thyroid dysfunction (cumulative risk: 1.9%), compared with 1,252 patients without ICM exposure (cumulative risk: 1.5%). The number needed to harm (NNH) was 1 for every 250 people, the investigators noted.

In the subgroup analysis, the adjusted hazard ratios of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.04-1.44) and 2.00 (95% CI, 1.65-2.44) when compared with controls. Patients with a higher Charlson’s Comorbidity Index were generally at a higher risk of thyroid dysfunction.

“In this study, we found a 22% increased risk of hyperthyroidism in ICM-exposed patients,” the authors wrote. “Although ICM-related imaging and interventional studies improve the disease diagnosis rate and quality of health, physicians should be aware of the complications of ICM and should apply it cautiously in clinical practice.”

For the full article, click here: J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015 (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-2329).

After adjusting for variables, patients with iodinated contrast media (ICM) exposure had a significantly higher risk of thyroid dysfunction (hazard ratio, 1.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.66), compared with that of patients in the non-ICM exposure group, wrote the authors of a newly published study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Lead author Dr. Edy Kornelius and associates examined 19,642 cases and 78,568 matched controls, recruited from the general population in Taiwan, in a 6-year cohort study. A total of 383 ICM-exposed patients had thyroid dysfunction (cumulative risk: 1.9%), compared with 1,252 patients without ICM exposure (cumulative risk: 1.5%). The number needed to harm (NNH) was 1 for every 250 people, the investigators noted.

In the subgroup analysis, the adjusted hazard ratios of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.04-1.44) and 2.00 (95% CI, 1.65-2.44) when compared with controls. Patients with a higher Charlson’s Comorbidity Index were generally at a higher risk of thyroid dysfunction.

“In this study, we found a 22% increased risk of hyperthyroidism in ICM-exposed patients,” the authors wrote. “Although ICM-related imaging and interventional studies improve the disease diagnosis rate and quality of health, physicians should be aware of the complications of ICM and should apply it cautiously in clinical practice.”

For the full article, click here: J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015 (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-2329).

After adjusting for variables, patients with iodinated contrast media (ICM) exposure had a significantly higher risk of thyroid dysfunction (hazard ratio, 1.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.66), compared with that of patients in the non-ICM exposure group, wrote the authors of a newly published study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Lead author Dr. Edy Kornelius and associates examined 19,642 cases and 78,568 matched controls, recruited from the general population in Taiwan, in a 6-year cohort study. A total of 383 ICM-exposed patients had thyroid dysfunction (cumulative risk: 1.9%), compared with 1,252 patients without ICM exposure (cumulative risk: 1.5%). The number needed to harm (NNH) was 1 for every 250 people, the investigators noted.

In the subgroup analysis, the adjusted hazard ratios of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism were 1.22 (95% CI, 1.04-1.44) and 2.00 (95% CI, 1.65-2.44) when compared with controls. Patients with a higher Charlson’s Comorbidity Index were generally at a higher risk of thyroid dysfunction.

“In this study, we found a 22% increased risk of hyperthyroidism in ICM-exposed patients,” the authors wrote. “Although ICM-related imaging and interventional studies improve the disease diagnosis rate and quality of health, physicians should be aware of the complications of ICM and should apply it cautiously in clinical practice.”

For the full article, click here: J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015 (doi:10.1210/JC.2015-2329).

Madelung Deformity and Extensor Tendon Rupture

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

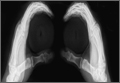

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

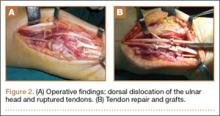

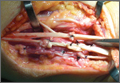

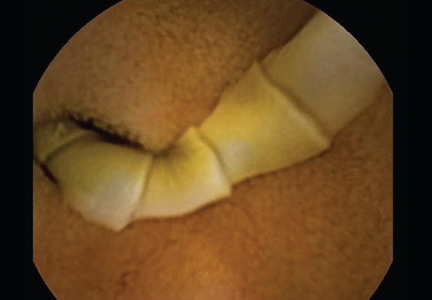

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

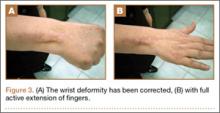

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

Image-Based Techniques for Percutaneous Iliosacral Screw Start-Site Localization

Iliosacral (SI) screws remain the standard of care for the vast majority of posterior pelvic ring disruptions.1,2 However, despite their routine use, the procedure remains technically demanding with repeated cases of aberrant screw placement and complications.3,4 Sacral morphology is extremely variable within a patient population and affects accurate placement and trajectory of percutaneous screws.5 Classically, it is taught that the external starting position/landmark is at an intersection point of the greater trochanter and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). While this “one size fits all” approach will certainly help to coordinate a start position, it is our experience that multiple stab incisions are necessary to find the optimal start site. To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side, guided by the lateral image.5 This article provides a novel image-based technique to be used with, or as a replacement for, the traditional technique.

Techniques

The patient is brought to the operating room and placed supine on a radiolucent operating table. If the closed reduction of the pelvic ring is successful or can be achieved via anterior manipulation/traction, posterior percutaneous pinning is planned. Either a rolled towel or a bag of saline is used as a bolster and placed midline underneath the sacrum and lumbar spine to help “bump” the pelvis and improve the range of motion for the surgeon’s drill. The patient is brought to the edge of the table when possible (ie, a posterior ring injury requiring fixation from only 1 side) to further enhance drill motion. If bilateral screws are planned, surgeons must be careful not to position 1 side at the expense of screw placement on the contralateral side. Nitrous-based anesthetic agents are avoided, because they may collect in the bowel and obscure good radiographic visualization. Arms are placed perpendicular to the body to facilitate the inlet view. Pre-preparation anteroposterior pelvis, inlet, and outlet views are obtained to assure ability to accurately and safely assess landmarks on all projections, and to mark the C-arm position and angles. This process helps decrease “useless” radiographs obtained during the procedure. Acceptable inlet radiographs show the anterior cortex of the S1 body superimposed on the S2 body. Acceptable outlet radiographs show the superior pubic symphysis at the level of the S2 foramen and visualization of the S1/S2 sacral foramen.6 The patient is then prepared in the standard fashion. Reduction maneuvers are performed and, if acceptable alignment is achieved, posterior percutaneous screw placement begins.

Technique 1

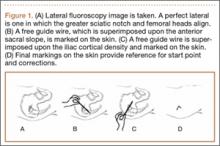

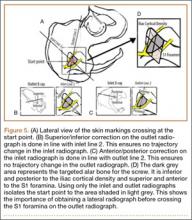

To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side using the lateral image. The fluoroscopic machine is set up in a lateral position.5 A free guide wire is superimposed upon the iliac cortical density and anterior sacral slope, which is marked on the skin (Figure 1). The superior portion of S1, as well as the posterior sacral slope, can be marked as well. This process has outlined the sacrum and provides an external landmark for the “safe zone” for screw placement. The operation proceeds in the standard fashion using inlet, outlet, and lateral radiographs. However, the externally drawn sacrum can aid as a reference during guide-pin placement.

Technique 2

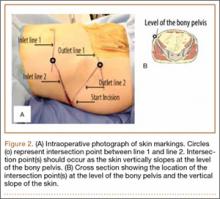

This technique takes into account bone anatomy and soft-tissue coverage. It is helpful to think of the abdomen/pelvis as a box. The anterior abdomen represents the top of the box and the lateral buttock represents the side of the box. The corner of the imaginary box is where the abdomen begins to slope down and transitions laterally to become the buttock. This will be referenced as the “down-sloping point” and typically corresponds to the level of the iliac crest (Figure 2).

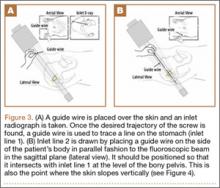

To begin, a standard cannulated screw guide wire is placed flush on the skin of the abdomen. An inlet fluoroscopy image is taken with the guide pin on the abdomen. Imagine that the resulting image represents the planned screw trajectory (Figure 3A). When the position of the guide wire is deemed adequate, a line is marked on the abdomen, using a pen, directly adjacent to the guide wire. This line represents inlet line 1 (Figure 2). The line must continue laterally until the down-sloping point. The sagittal angle of the imaginary inlet fluoroscopic beam is noted, and a guide wire is placed in the same sagittal orientation flush with the skin on the lateral buttock (Figure 3B). The guide wire must be placed so that it intersects with the first line at the down-sloping point. The skin on the lateral aspect of buttock is marked with a second line, which represents inlet line 2 (Figure 2).

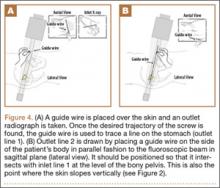

The same process is repeated using an outlet view to create outlet lines 1 and 2 (Figures 4A, 4B). At this point there are 4 lines drawn on the patient (Figure 2). A stab incision is made at the intersection of the 2 lines drawn on the lateral buttock; this represents the skin start point, labeled “start incision” (Figure 2). The procedure continues in standard fashion.

The 4 external reference lines serve multiple purposes. First, the lines mark the true lateral start point for the pin at the level of the skin. This contrasts with the standard technique in which bony landmarks are marked on the skin and the surgeon must estimate a point on the skin that will provide an appropriate trajectory to the bony start point on the ilium. Further, the lines can also be used to reorient the cartesian plane so that adjustments can be isolated to a single plane, ensuring movements only alter the position on a single radiographic view (Figure 5).

Discussion

Despite the widespread use of percutaneous screw placement for posterior pelvic ring injuries, this remains a technically demanding surgery. Recent data suggest patient pelvic anatomy is extremely varied, especially the sacrum.7 Further, screw trajectories vary depending on surgical goals, fracture pattern, and number of screws. Taken together, this implies that there is no perfect universal starting site along the external ilium. Therefore, while classic teaching states to begin screw insertion within the vicinity of the intersection of the greater trochanter and the ASIS, it is our experience that this location is often not ideal.

The inlet, outlet, and lateral radiographs are all vital to assess correct trajectory of the guide pin and drill prior to final screw insertion, but the start site remains a critical step to assure a successful surgical outcome. We present 2 techniques, used together or separately, that allow the surgeon to place the initial guide pin more accurately for percutanous iliosacral screws. Though not specifically examined in this study, we think technique 2 has the potential to save operative time and use less fluoroscopic imaging because a lateral image is not required until later in the case. Technique 2 identifies the start point at the level of the skin. This is in contrast to technique 1, which identifies the desired sacral target and requires a surgeon to select a skin start site that will provide an optimal trajectory towards the desired target. Judging trajectory can be difficult, particularly in obese patients, and technique 2 eliminates this extra variable.

It is also important to consider that criteria-based nonorthogonal imaging is required for percutaneous screw placement. In these cases, it is more difficult to judge trajectory corrections because the fluoroscopic beam cannot guide perpendicular corrections as it can in operations that use orthogonal imaging. Adjustments made perpendicular to the fluoroscopic beam will change trajectory in multiple planes.8 Moreover, because the standard cartesian frame of reference is rotated, understanding the location of the sacrum in space can be especially challenging. When using the first technique, sacral landmarks are delineated, and a virtual sacrum drawn on the patient’s exterior helps with orientation. In the second technique, the ideal pin placement is mapped, and the external reference lines guide uniplanar changes. For example, the line drawn co-planar with the inlet view is essentially marking the sacral slope. Therefore, by following this line, uniplanar changes in the cranial and caudal direction are achieved on the outlet view (Figure 5). Because this line is also in reference to the already known ideal pin placement, ideal pin placement can be maintained in 1 radiographic projection while changing the start site in the appropriate direction. In a similar fashion, the co-planar line identified on the inlet view can be used on the outlet image to affect uniplanar changes in the anteroposterior direction. This technique effectively minimizes disorientation when placing percutaneous SI screws. This can be particularly beneficial when placing screws in the prone position.

Conclusion

We have shown 2 techniques that are routinely used at our institution to help identify an accurate starting position for percutaneous screw placement in posterior pelvic ring injuries. Even experienced traumatologists can more quickly and accurately identify the correct stab incisions leading to more confidently placed screws. Further, we believe understanding the usage of fluoroscopy and the concepts involved in drawing the lines enhance trainees’ comprehension of the complex anatomy of the sacrum.

1. Matta JM, Saucedo T. Internal fixation of pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;242:83-97.

2. Routt ML Jr, Kregor PJ, Simonian PT, Mayo KA. Early results of percutaneous iliosacral screws placed with the patient in the supine position. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):207-214.

3. Sagi HC, Lindvall EM. Inadvertent intraforaminal iliosacral screw placement despite apparent appropriate positioning on intraoperative fluoroscopy.

J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(2):130-133.

4. Routt ML Jr, Simonian PT, Mills WJ. Iliosacral screw fixation: early complications of the percutaneous technique. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(8):584-589.

5. Routt ML Jr, Simonian PT, Agnew SG, Mann FA. Radiographic recognition of the sacral alar slope for optimal placement of iliosacral screws: a cadaveric and clinical study. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(3):171-177.

6. Gardner MJ, Ferrell ED, Nork SE, Segina DN, Routt ML Jr. Percutaneous placement of iliosacral screws without electrodiagnostic monitoring. J Trauma. 2009;66(5):1411-1415.

7. Miller AN, Routt ML Jr. Variations in sacral morphology and implications for iliosacral screw fixation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(1):8-16.

8. Graves ML, Routt ML. Iliosacral screw placement: are uniplanar changes realistic based on standard fluoroscopic imaging? J Orthop Trauma. 2011;71(1):204-208.

Iliosacral (SI) screws remain the standard of care for the vast majority of posterior pelvic ring disruptions.1,2 However, despite their routine use, the procedure remains technically demanding with repeated cases of aberrant screw placement and complications.3,4 Sacral morphology is extremely variable within a patient population and affects accurate placement and trajectory of percutaneous screws.5 Classically, it is taught that the external starting position/landmark is at an intersection point of the greater trochanter and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). While this “one size fits all” approach will certainly help to coordinate a start position, it is our experience that multiple stab incisions are necessary to find the optimal start site. To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side, guided by the lateral image.5 This article provides a novel image-based technique to be used with, or as a replacement for, the traditional technique.

Techniques

The patient is brought to the operating room and placed supine on a radiolucent operating table. If the closed reduction of the pelvic ring is successful or can be achieved via anterior manipulation/traction, posterior percutaneous pinning is planned. Either a rolled towel or a bag of saline is used as a bolster and placed midline underneath the sacrum and lumbar spine to help “bump” the pelvis and improve the range of motion for the surgeon’s drill. The patient is brought to the edge of the table when possible (ie, a posterior ring injury requiring fixation from only 1 side) to further enhance drill motion. If bilateral screws are planned, surgeons must be careful not to position 1 side at the expense of screw placement on the contralateral side. Nitrous-based anesthetic agents are avoided, because they may collect in the bowel and obscure good radiographic visualization. Arms are placed perpendicular to the body to facilitate the inlet view. Pre-preparation anteroposterior pelvis, inlet, and outlet views are obtained to assure ability to accurately and safely assess landmarks on all projections, and to mark the C-arm position and angles. This process helps decrease “useless” radiographs obtained during the procedure. Acceptable inlet radiographs show the anterior cortex of the S1 body superimposed on the S2 body. Acceptable outlet radiographs show the superior pubic symphysis at the level of the S2 foramen and visualization of the S1/S2 sacral foramen.6 The patient is then prepared in the standard fashion. Reduction maneuvers are performed and, if acceptable alignment is achieved, posterior percutaneous screw placement begins.

Technique 1

To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side using the lateral image. The fluoroscopic machine is set up in a lateral position.5 A free guide wire is superimposed upon the iliac cortical density and anterior sacral slope, which is marked on the skin (Figure 1). The superior portion of S1, as well as the posterior sacral slope, can be marked as well. This process has outlined the sacrum and provides an external landmark for the “safe zone” for screw placement. The operation proceeds in the standard fashion using inlet, outlet, and lateral radiographs. However, the externally drawn sacrum can aid as a reference during guide-pin placement.

Technique 2

This technique takes into account bone anatomy and soft-tissue coverage. It is helpful to think of the abdomen/pelvis as a box. The anterior abdomen represents the top of the box and the lateral buttock represents the side of the box. The corner of the imaginary box is where the abdomen begins to slope down and transitions laterally to become the buttock. This will be referenced as the “down-sloping point” and typically corresponds to the level of the iliac crest (Figure 2).

To begin, a standard cannulated screw guide wire is placed flush on the skin of the abdomen. An inlet fluoroscopy image is taken with the guide pin on the abdomen. Imagine that the resulting image represents the planned screw trajectory (Figure 3A). When the position of the guide wire is deemed adequate, a line is marked on the abdomen, using a pen, directly adjacent to the guide wire. This line represents inlet line 1 (Figure 2). The line must continue laterally until the down-sloping point. The sagittal angle of the imaginary inlet fluoroscopic beam is noted, and a guide wire is placed in the same sagittal orientation flush with the skin on the lateral buttock (Figure 3B). The guide wire must be placed so that it intersects with the first line at the down-sloping point. The skin on the lateral aspect of buttock is marked with a second line, which represents inlet line 2 (Figure 2).