User login

Do healthy patients need routine laboratory testing before elective noncardiac surgery?

A 63-year-old physician is referred for preoperative evaluation before arthroscopic repair of a torn medial meniscus. Her exercise tolerance was excellent before the knee injury, including running without cardiopulmonary symptoms. She is otherwise healthy except for hypertension that is well controlled on amlodipine. She has no known history of liver or kidney disease, bleeding disorder, recent illness, or complications with anesthesia. She inquires as to whether “routine blood testing” is needed before the procedure.

What laboratory studies, if any, should be ordered?

UNLIKELY TO BE OF BENEFIT

Preoperative laboratory testing is not necessary in this otherwise healthy, asymptomatic patient. In the absence of clinical indications, routine testing before elective, low-risk procedures often increases both the cost of care and the potential anxiety caused by abnormal results that provide no substantial benefit to the patient or the clinician.

Preoperative diagnostic tests should be ordered only to identify and optimize disorders that alter the likelihood of perioperative and postoperative adverse outcomes and to establish a baseline assessment. Yet clinicians often perceive that laboratory testing is required by their organization or by other providers.

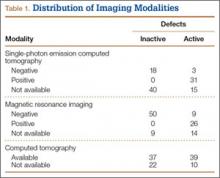

A comprehensive history and physical examination are the cornerstones of the effective preoperative evaluation. Preferably, the history and examination should guide further testing rather than ordering a battery of standard tests for all patients. However, selective preoperative laboratory testing may be useful in certain situations, such as in patients undergoing high-risk procedures and those with known underlying conditions or factors that may affect operative management (Table 1).

Unfortunately, high-quality evidence for this selective approach is lacking. According to one observational study,1 when laboratory testing is appropriate, it is reasonable to use test results already obtained and normal within the preceding 4 months unless the patient has had an interim change in health status.

Definitions of risk stratification (eg, urgency of surgical procedure, graded risk according to type of operation) and tools such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index can be found in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines2 and may be useful to distinguish healthy patients from those with significant comorbidities, as well as to distinguish low-risk, elective procedures from those that impart higher risk.

Professional societies and guidelines in many countries have criticized the habitual practice of extensive, nonselective laboratory testing.3–6 Yet despite lack of evidence of benefit, routine preoperative testing is still often done. At an estimated cost of more than $18 billion in the United States annually,7 preoperative testing deserves attention, especially in this time of ballooning healthcare costs and increased focus on effective and efficient care.

EVIDENCE AND GUIDELINES

Numerous studies have established that routine laboratory testing rarely changes the preoperative management of the patient or improves surgical outcomes. Narr et al8 found that 160 (4%) of 3,782 patients who underwent ambulatory surgery had abnormal test results, and only 10 required treatment. In this study, there was no association between abnormal test results and perioperative management or postoperative adverse events.

In a systematic review, Smetana and Macpherson9 noted that the incidence of laboratory test abnormalities that led to a change in management ranged from 0.1% to 2.6%. Notably, clinicians ignore 30% to 60% of abnormal preoperative laboratory results, a practice that may create additional medicolegal risk.7

Little evidence exists that helps in the development of guidelines for preoperative laboratory testing. Most guidelines are based on expert opinion, case series, and consensus. As an example of the heterogeneity this creates, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Ontario Preoperative Testing Group, and the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society provide different recommended indications for preoperative laboratory testing in patients with “advanced age” but do not define a clear minimum age for this cohort.10

However, one area that does have substantial data is cataract surgery. Patients in their usual state of health who are to undergo this procedure do not require preoperative testing, a claim supported by high-quality evidence including a 2012 Cochrane systematic review.11

Munro et al5 performed a systematic review of the evidence behind preoperative laboratory testing, concluding that the power of preoperative tests to predict adverse postoperative outcomes in asymptomatic patients is either weak or nonexistent. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines of 2003,6 the Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation of the American Society of Anesthesiologists of 2012,12 the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guideline of 2012,13 and a systematic review conducted by Johansson et al14 found no evidence from high-quality studies to support the claim that routine preoperative testing is beneficial in healthy adults undergoing noncardiac surgery, but that certain patient populations may benefit from selective testing.

A randomized controlled trial evaluated the elimination of preoperative testing in patients undergoing low-risk ambulatory surgery and found no difference in perioperative adverse events in the control and intervention arms.15 Similar studies achieved the same results.

The Choosing Wisely campaign

The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has partnered with medical specialty societies to create lists of common practice patterns that should be questioned and possibly discontinued. These lists are collectively called the Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org). Avoiding routine preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing low-risk surgery without clinical indications can be found in the lists for the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the American Society for Clinical Pathology, and the Society of General Internal Medicine.

THE POSSIBLE HARMS OF TESTING

The prevalence of unrecognized disease that influences the risk of surgery in healthy patients is low, and thus the predictive value of abnormal test values in these patients is low. This leads to substantial false-positivity, which is of uncertain clinical significance and which may in turn cause a cascade of further testing. Not surprisingly, the probability of an abnormal test result increases dramatically with the number of tests ordered, a fact that magnifies the problem of false-positive results.

The costs and harms associated with testing are both direct and indirect. Direct effects include increased healthcare costs of further testing or potentially unnecessary treatment as well as risk associated with additional testing, though these are not common, as there is a low (< 3%) incidence of a change in preoperative management based on an abnormal test result. Likewise, normal results do not appear to substantially reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.9

Indirect effects, which are particularly challenging to measure, may include time lost from employment to pursue further evaluation and anxiety surrounding abnormal results.

THE CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Based on over 2 decades of data, our 63-year-old patient should not undergo “routine” preoperative laboratory testing before her upcoming elective, low-risk, noncardiac procedure. Her hypertension is well controlled, and she is taking no medications that may lead to clinically significant metabolic derangements or significant changes in surgical outcome. There are no convincing clinical indications for further laboratory investigation. Further, the results are unlikely to affect the preoperative management and rate of adverse events; the direct and indirect costs may be substantial; and there is a small but tangible risk of harm.

Given the myriad factors that influence unnecessary preoperative testing, a focus on systems-level solutions is paramount. Key steps may include creation and adoption of clear and consistent guidelines, development of clinical care pathways, physician education and modification of practice, interdisciplinary communication and information sharing, economic analysis, and outcomes assessment.

- Macpherson DS, Snow R, Lofgren RP. Preoperative screening: value of previous tests. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:969–973.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2014; 130:e278–e333.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of medical testing for cataract surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:168–175.

- The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Preoperative routines. Stockholm, 1989.

- Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess 1997; 1:1–62.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Preoperative tests: The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, 2003.

- Roizen MF. More preoperative assessment by physicians and less by laboratory tests. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:204–205.

- Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening in healthy Mayo patients: cost-effective elimination of tests and unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66:155–159.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003; 87:7–40.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg 2012; 256:518–528.

- Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, Katz J, Schein O. Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 3:CD007293.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health care guideline: preoperative evaluation. 10th ed. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2012.

- Johansson T, Fritsch G, Flamm M, et al. Effectiveness of non-cardiac preoperative testing in non-cardiac elective surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110:926–939.

- Chung F, Yuan H, Yin L, Vairavanathan S, Wong DT. Elimination of preoperative testing in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:467–475.

A 63-year-old physician is referred for preoperative evaluation before arthroscopic repair of a torn medial meniscus. Her exercise tolerance was excellent before the knee injury, including running without cardiopulmonary symptoms. She is otherwise healthy except for hypertension that is well controlled on amlodipine. She has no known history of liver or kidney disease, bleeding disorder, recent illness, or complications with anesthesia. She inquires as to whether “routine blood testing” is needed before the procedure.

What laboratory studies, if any, should be ordered?

UNLIKELY TO BE OF BENEFIT

Preoperative laboratory testing is not necessary in this otherwise healthy, asymptomatic patient. In the absence of clinical indications, routine testing before elective, low-risk procedures often increases both the cost of care and the potential anxiety caused by abnormal results that provide no substantial benefit to the patient or the clinician.

Preoperative diagnostic tests should be ordered only to identify and optimize disorders that alter the likelihood of perioperative and postoperative adverse outcomes and to establish a baseline assessment. Yet clinicians often perceive that laboratory testing is required by their organization or by other providers.

A comprehensive history and physical examination are the cornerstones of the effective preoperative evaluation. Preferably, the history and examination should guide further testing rather than ordering a battery of standard tests for all patients. However, selective preoperative laboratory testing may be useful in certain situations, such as in patients undergoing high-risk procedures and those with known underlying conditions or factors that may affect operative management (Table 1).

Unfortunately, high-quality evidence for this selective approach is lacking. According to one observational study,1 when laboratory testing is appropriate, it is reasonable to use test results already obtained and normal within the preceding 4 months unless the patient has had an interim change in health status.

Definitions of risk stratification (eg, urgency of surgical procedure, graded risk according to type of operation) and tools such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index can be found in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines2 and may be useful to distinguish healthy patients from those with significant comorbidities, as well as to distinguish low-risk, elective procedures from those that impart higher risk.

Professional societies and guidelines in many countries have criticized the habitual practice of extensive, nonselective laboratory testing.3–6 Yet despite lack of evidence of benefit, routine preoperative testing is still often done. At an estimated cost of more than $18 billion in the United States annually,7 preoperative testing deserves attention, especially in this time of ballooning healthcare costs and increased focus on effective and efficient care.

EVIDENCE AND GUIDELINES

Numerous studies have established that routine laboratory testing rarely changes the preoperative management of the patient or improves surgical outcomes. Narr et al8 found that 160 (4%) of 3,782 patients who underwent ambulatory surgery had abnormal test results, and only 10 required treatment. In this study, there was no association between abnormal test results and perioperative management or postoperative adverse events.

In a systematic review, Smetana and Macpherson9 noted that the incidence of laboratory test abnormalities that led to a change in management ranged from 0.1% to 2.6%. Notably, clinicians ignore 30% to 60% of abnormal preoperative laboratory results, a practice that may create additional medicolegal risk.7

Little evidence exists that helps in the development of guidelines for preoperative laboratory testing. Most guidelines are based on expert opinion, case series, and consensus. As an example of the heterogeneity this creates, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Ontario Preoperative Testing Group, and the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society provide different recommended indications for preoperative laboratory testing in patients with “advanced age” but do not define a clear minimum age for this cohort.10

However, one area that does have substantial data is cataract surgery. Patients in their usual state of health who are to undergo this procedure do not require preoperative testing, a claim supported by high-quality evidence including a 2012 Cochrane systematic review.11

Munro et al5 performed a systematic review of the evidence behind preoperative laboratory testing, concluding that the power of preoperative tests to predict adverse postoperative outcomes in asymptomatic patients is either weak or nonexistent. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines of 2003,6 the Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation of the American Society of Anesthesiologists of 2012,12 the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guideline of 2012,13 and a systematic review conducted by Johansson et al14 found no evidence from high-quality studies to support the claim that routine preoperative testing is beneficial in healthy adults undergoing noncardiac surgery, but that certain patient populations may benefit from selective testing.

A randomized controlled trial evaluated the elimination of preoperative testing in patients undergoing low-risk ambulatory surgery and found no difference in perioperative adverse events in the control and intervention arms.15 Similar studies achieved the same results.

The Choosing Wisely campaign

The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has partnered with medical specialty societies to create lists of common practice patterns that should be questioned and possibly discontinued. These lists are collectively called the Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org). Avoiding routine preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing low-risk surgery without clinical indications can be found in the lists for the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the American Society for Clinical Pathology, and the Society of General Internal Medicine.

THE POSSIBLE HARMS OF TESTING

The prevalence of unrecognized disease that influences the risk of surgery in healthy patients is low, and thus the predictive value of abnormal test values in these patients is low. This leads to substantial false-positivity, which is of uncertain clinical significance and which may in turn cause a cascade of further testing. Not surprisingly, the probability of an abnormal test result increases dramatically with the number of tests ordered, a fact that magnifies the problem of false-positive results.

The costs and harms associated with testing are both direct and indirect. Direct effects include increased healthcare costs of further testing or potentially unnecessary treatment as well as risk associated with additional testing, though these are not common, as there is a low (< 3%) incidence of a change in preoperative management based on an abnormal test result. Likewise, normal results do not appear to substantially reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.9

Indirect effects, which are particularly challenging to measure, may include time lost from employment to pursue further evaluation and anxiety surrounding abnormal results.

THE CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Based on over 2 decades of data, our 63-year-old patient should not undergo “routine” preoperative laboratory testing before her upcoming elective, low-risk, noncardiac procedure. Her hypertension is well controlled, and she is taking no medications that may lead to clinically significant metabolic derangements or significant changes in surgical outcome. There are no convincing clinical indications for further laboratory investigation. Further, the results are unlikely to affect the preoperative management and rate of adverse events; the direct and indirect costs may be substantial; and there is a small but tangible risk of harm.

Given the myriad factors that influence unnecessary preoperative testing, a focus on systems-level solutions is paramount. Key steps may include creation and adoption of clear and consistent guidelines, development of clinical care pathways, physician education and modification of practice, interdisciplinary communication and information sharing, economic analysis, and outcomes assessment.

A 63-year-old physician is referred for preoperative evaluation before arthroscopic repair of a torn medial meniscus. Her exercise tolerance was excellent before the knee injury, including running without cardiopulmonary symptoms. She is otherwise healthy except for hypertension that is well controlled on amlodipine. She has no known history of liver or kidney disease, bleeding disorder, recent illness, or complications with anesthesia. She inquires as to whether “routine blood testing” is needed before the procedure.

What laboratory studies, if any, should be ordered?

UNLIKELY TO BE OF BENEFIT

Preoperative laboratory testing is not necessary in this otherwise healthy, asymptomatic patient. In the absence of clinical indications, routine testing before elective, low-risk procedures often increases both the cost of care and the potential anxiety caused by abnormal results that provide no substantial benefit to the patient or the clinician.

Preoperative diagnostic tests should be ordered only to identify and optimize disorders that alter the likelihood of perioperative and postoperative adverse outcomes and to establish a baseline assessment. Yet clinicians often perceive that laboratory testing is required by their organization or by other providers.

A comprehensive history and physical examination are the cornerstones of the effective preoperative evaluation. Preferably, the history and examination should guide further testing rather than ordering a battery of standard tests for all patients. However, selective preoperative laboratory testing may be useful in certain situations, such as in patients undergoing high-risk procedures and those with known underlying conditions or factors that may affect operative management (Table 1).

Unfortunately, high-quality evidence for this selective approach is lacking. According to one observational study,1 when laboratory testing is appropriate, it is reasonable to use test results already obtained and normal within the preceding 4 months unless the patient has had an interim change in health status.

Definitions of risk stratification (eg, urgency of surgical procedure, graded risk according to type of operation) and tools such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index can be found in the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines2 and may be useful to distinguish healthy patients from those with significant comorbidities, as well as to distinguish low-risk, elective procedures from those that impart higher risk.

Professional societies and guidelines in many countries have criticized the habitual practice of extensive, nonselective laboratory testing.3–6 Yet despite lack of evidence of benefit, routine preoperative testing is still often done. At an estimated cost of more than $18 billion in the United States annually,7 preoperative testing deserves attention, especially in this time of ballooning healthcare costs and increased focus on effective and efficient care.

EVIDENCE AND GUIDELINES

Numerous studies have established that routine laboratory testing rarely changes the preoperative management of the patient or improves surgical outcomes. Narr et al8 found that 160 (4%) of 3,782 patients who underwent ambulatory surgery had abnormal test results, and only 10 required treatment. In this study, there was no association between abnormal test results and perioperative management or postoperative adverse events.

In a systematic review, Smetana and Macpherson9 noted that the incidence of laboratory test abnormalities that led to a change in management ranged from 0.1% to 2.6%. Notably, clinicians ignore 30% to 60% of abnormal preoperative laboratory results, a practice that may create additional medicolegal risk.7

Little evidence exists that helps in the development of guidelines for preoperative laboratory testing. Most guidelines are based on expert opinion, case series, and consensus. As an example of the heterogeneity this creates, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the Ontario Preoperative Testing Group, and the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society provide different recommended indications for preoperative laboratory testing in patients with “advanced age” but do not define a clear minimum age for this cohort.10

However, one area that does have substantial data is cataract surgery. Patients in their usual state of health who are to undergo this procedure do not require preoperative testing, a claim supported by high-quality evidence including a 2012 Cochrane systematic review.11

Munro et al5 performed a systematic review of the evidence behind preoperative laboratory testing, concluding that the power of preoperative tests to predict adverse postoperative outcomes in asymptomatic patients is either weak or nonexistent. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines of 2003,6 the Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation of the American Society of Anesthesiologists of 2012,12 the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guideline of 2012,13 and a systematic review conducted by Johansson et al14 found no evidence from high-quality studies to support the claim that routine preoperative testing is beneficial in healthy adults undergoing noncardiac surgery, but that certain patient populations may benefit from selective testing.

A randomized controlled trial evaluated the elimination of preoperative testing in patients undergoing low-risk ambulatory surgery and found no difference in perioperative adverse events in the control and intervention arms.15 Similar studies achieved the same results.

The Choosing Wisely campaign

The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has partnered with medical specialty societies to create lists of common practice patterns that should be questioned and possibly discontinued. These lists are collectively called the Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org). Avoiding routine preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing low-risk surgery without clinical indications can be found in the lists for the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the American Society for Clinical Pathology, and the Society of General Internal Medicine.

THE POSSIBLE HARMS OF TESTING

The prevalence of unrecognized disease that influences the risk of surgery in healthy patients is low, and thus the predictive value of abnormal test values in these patients is low. This leads to substantial false-positivity, which is of uncertain clinical significance and which may in turn cause a cascade of further testing. Not surprisingly, the probability of an abnormal test result increases dramatically with the number of tests ordered, a fact that magnifies the problem of false-positive results.

The costs and harms associated with testing are both direct and indirect. Direct effects include increased healthcare costs of further testing or potentially unnecessary treatment as well as risk associated with additional testing, though these are not common, as there is a low (< 3%) incidence of a change in preoperative management based on an abnormal test result. Likewise, normal results do not appear to substantially reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.9

Indirect effects, which are particularly challenging to measure, may include time lost from employment to pursue further evaluation and anxiety surrounding abnormal results.

THE CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Based on over 2 decades of data, our 63-year-old patient should not undergo “routine” preoperative laboratory testing before her upcoming elective, low-risk, noncardiac procedure. Her hypertension is well controlled, and she is taking no medications that may lead to clinically significant metabolic derangements or significant changes in surgical outcome. There are no convincing clinical indications for further laboratory investigation. Further, the results are unlikely to affect the preoperative management and rate of adverse events; the direct and indirect costs may be substantial; and there is a small but tangible risk of harm.

Given the myriad factors that influence unnecessary preoperative testing, a focus on systems-level solutions is paramount. Key steps may include creation and adoption of clear and consistent guidelines, development of clinical care pathways, physician education and modification of practice, interdisciplinary communication and information sharing, economic analysis, and outcomes assessment.

- Macpherson DS, Snow R, Lofgren RP. Preoperative screening: value of previous tests. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:969–973.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2014; 130:e278–e333.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of medical testing for cataract surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:168–175.

- The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Preoperative routines. Stockholm, 1989.

- Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess 1997; 1:1–62.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Preoperative tests: The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, 2003.

- Roizen MF. More preoperative assessment by physicians and less by laboratory tests. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:204–205.

- Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening in healthy Mayo patients: cost-effective elimination of tests and unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66:155–159.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003; 87:7–40.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg 2012; 256:518–528.

- Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, Katz J, Schein O. Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 3:CD007293.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health care guideline: preoperative evaluation. 10th ed. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2012.

- Johansson T, Fritsch G, Flamm M, et al. Effectiveness of non-cardiac preoperative testing in non-cardiac elective surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110:926–939.

- Chung F, Yuan H, Yin L, Vairavanathan S, Wong DT. Elimination of preoperative testing in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:467–475.

- Macpherson DS, Snow R, Lofgren RP. Preoperative screening: value of previous tests. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:969–973.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2014; 130:e278–e333.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of medical testing for cataract surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:168–175.

- The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Preoperative routines. Stockholm, 1989.

- Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess 1997; 1:1–62.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Preoperative tests: The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, 2003.

- Roizen MF. More preoperative assessment by physicians and less by laboratory tests. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:204–205.

- Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening in healthy Mayo patients: cost-effective elimination of tests and unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66:155–159.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003; 87:7–40.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg 2012; 256:518–528.

- Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, Katz J, Schein O. Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 3:CD007293.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Health care guideline: preoperative evaluation. 10th ed. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2012.

- Johansson T, Fritsch G, Flamm M, et al. Effectiveness of non-cardiac preoperative testing in non-cardiac elective surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110:926–939.

- Chung F, Yuan H, Yin L, Vairavanathan S, Wong DT. Elimination of preoperative testing in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:467–475.

Why do clinicians continue to order ‘routine preoperative tests’ despite the evidence?

Guidelines and practice advisories issued by several medical societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists,1 American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC),2 and Society of General Internal Medicine,3 advise against routine preoperative testing for patients undergoing low-risk surgical procedures. Such testing often includes routine blood chemistry, complete blood cell counts, measures of the clotting system, and cardiac stress testing.

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Dr. Nathan Houchens reviews the evidence against these measures.4

Despite a substantial body of evidence going back more than 2 decades that includes prospective randomized controlled trials,5–10 physicians continue to order unnecessary, ineffective, and costly tests in the perioperative period.11 The process of abandoning current medical practice—a phenomenon known as medical reversal12—often takes years,13 because it is more difficult to convince physicians to discontinue a current behavior than to implement a new one.14 The study of what makes physicians accept new therapies and abandon old ones began more than half a century ago.15

More recently, Cabana et al16 created a framework to understand why physicians do not follow clinical practice guidelines. Among the reasons are lack of familiarity or agreement with the contents of the guideline, lack of outcome expectancy, inertia of previous practice, and external barriers to implementation.

The rapid proliferation of guidelines in the past 20 years has led to numerous conflicting recommendations, many of which are based primarily on expert opinion.17 Guidelines based solely on randomized trials have also come under fire.18,19

In the case of preoperative testing, the recommendations are generally evidence-based and consistent. Why then do physicians appear to disregard the evidence? We propose several reasons why they might do so.

SOME PHYSICIANS ARE UNFAMILIAR WITH THE EVIDENCE

The complexity of the evidence summarized in guidelines has increased exponentially in the last decade, but physician time to assess the evidence has not increased. For example, the number of references in the executive summary of the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines increased from 96 in 2002 to 252 in 2014. Most of the recommendations are backed by substantial amounts of high-quality evidence. For example, there are 17 prospective and 13 retrospective studies demonstrating that routine testing with the prothrombin time and the partial thromboplastin time is not helpful in asymptomatic patients.20

Although compliance with medical evidence varies among specialties,21 most physicians do not have time to keep up with the ever-increasing amount of information. Specifically in the area of cardiac risk assessment, there has been a rapid proliferation of tests that can be used to assess cardiac risk.22–28 In a Harris Interactive survey from 2008, physicians reported not applying medical evidence routinely. One-third believed they would do it more if they had the time.29 Without information technology support to provide medical information at the point of care,30 especially in small practices, using evidence may not be practical. Simply making the information available online and not promoting it actively does not improve utilization.31

As a consequence, physicians continue to order unnecessary tests, even though they may not feel confident interpreting the results.32

PHYSICIANS MAY NOT BELIEVE THE EVIDENCE

A lack of transparency in evidence-based guidelines and, sometimes, a lack of flexibility and relevance to clinical practice are important barriers to physicians’ acceptance of and adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.30

Even experts who write guidelines may not be swayed by the evidence. For example, a randomized prospective trial of almost 6,000 patients reported that coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery does not affect long-term mortality rates.33 Based on this study, the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines2 advised against revascularization before noncardiac surgery exclusively to reduce perioperative cardiac events. Yet the same guidelines do recommend assessing for myocardial ischemia in patients with elevated risk and poor or unknown functional capacity, using a pharmacologic stress test. Based on the extent of the stress test abnormalities, coronary angiography and revascularization are then suggested for patients willing to undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention.2

The 2014 European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Anaesthesiology guidelines directly recommend revascularization before high-risk surgery, depending on the extent of a stress-induced perfusion defect.34 This recommendation relies on data from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry, which included almost 25,000 patients who underwent coronary angiography from 1975 through 1979. At a mean follow-up of 4.1 years, 1,961 patients underwent high-risk surgery. In this observational cohort, patients who underwent CABG had a lower risk of death and myocardial infarction after surgery.35 The reliance of medical societies34 on data that are more than 30 years old—when operative mortality rates and the treatment of coronary artery disease have changed substantially in the interim and despite the fact that this study did not test whether preoperative revascularization can reduce postoperative mortality—reflects a certain resistance to accept the results of the more recent and relevant randomized trial.33

Other physicians may also prefer to rely on selective data or to simply defer to guidelines that support their beliefs. Some physicians find that evidence-based guidelines are impractical and rigid and reduce their autonomy.36 For many physicians, trials that use surrogate end points and short-term outcomes are not sufficiently compelling to make them abandon current practice.37 Finally, when members of the guideline committees have financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry, or when corporations interested in the outcomes provide financial support for a trial’s development, the likelihood of a recommendation being trusted and used by physicians is drastically reduced.38

PRACTICING DEFENSIVELY

Even if physicians are familiar with the evidence and believe it, they may choose not to act on it. One reason is fear of litigation.

In court, attorneys can use guidelines as well as articles from medical journals as both exculpatory and inculpatory evidence. But they more frequently rely on the standard of care, or what most physicians would do under similar circumstances. If a patient has a bad outcome, such as a perioperative myocardial infarction or life-threatening bleeding, the defendant may assert that testing was unwarranted because guidelines do not recommend it or because the probability of such an outcome was low. However, because the outcome occurred, the jury may not believe that the probability was low enough not to consider, especially if expert witnesses testify that the standard of care would be to order the test.

In areas of controversy, physicians generally believe that erring on the side of more testing is more defensible in court.39 Indeed, following established practice traditions, learned during residency,11,40 may absolve physicians in negligence claims if the way medical care was delivered is supported by recognized and respected physicians.41

As a consequence, physicians prefer to practice the same way their peers do rather than follow the evidence. Unfortunately, the more procedures physicians perform for low-risk patients, the more likely these tests will become accepted as the legal standard of care.42 In this vicious circle, the new standard of care can increase the risk of litigation for others.43 Although unnecessary testing that leads to harmful invasive tests or procedures can also result in malpractice litigation, physicians may not consider this possibility.

FINANCIAL INCENTIVES

The threat of malpractice litigation provides a negative financial incentive to keep performing unnecessary tests, but there are a number of positive incentives as well.

First, physicians often feel compelled to order tests when they believe that physicians referring the patients want the tests done, or when they fear that not completing the tests could delay or cancel the scheduled surgery.40 Refusing to order the test could result in a loss of future referrals. In contrast, ordering tests allows them to meet expectations, preserve trust, and appear more valuable to referring physicians and their patients.

Insurance companies are complicit in these practices. Paying for unnecessary tests can create direct financial incentives for physicians or institutions that own on-site laboratories or diagnostic imaging equipment. Evidence shows that under those circumstances physicians do order more tests. Self-referral and referral to facilities where physicians have a financial interest is associated with increased healthcare costs.44 In addition to direct revenues for the tests performed, physicians may also bill for test interpretation, follow-up visits, and additional procedures generated from test results.

This may be one explanation why the ordering of cardiac tests (stress testing, echocardiography, vascular ultrasonography) by US physicians varies widely from state to state.45

RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE INAPPROPRIATE TESTING

To counter these influences, we propose a multifaceted intervention that includes the following:

- Establish preoperative clinics staffed by experts. Despite the large volume of potentially relevant evidence, the number of articles directly supporting or refuting preoperative laboratory testing is small enough that physicians who routinely engage in preoperative assessment should easily master the evidence.

- Identify local leaders who can convince colleagues of the evidence. Distribute evidence summaries or guidelines with references to major articles that support each recommendation.

- Work with clinical practice committees to establish new standards of care within the hospital. Establish hospital care paths to dictate and support local standards of care. Measure individual physician performance and offer feedback with the goal of reducing utilization.

- National societies should recommend that insurance companies remove inappropriate financial incentives. If companies deny payment for inappropriate testing, physicians will stop ordering it. Even requirements for preauthorization of tests should reduce utilization. The Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org) would be a good place to start.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al; American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e77–e137.

- Society of General Internal Medicine. Don’t perform routine pre-operative testing before low-risk surgical procedures. Choosing Wisely. An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. September 12, 2013. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/society-general-internal-medicine-routine-preoperative-testing-before-low-risk-surgery/. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Houchens N. Should healthy patients undergoing low-risk, elective, noncardiac surgery undergo routine preoperative laboratory testing? Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:664–666.

- Rohrer MJ, Michelotti MC, Nahrwold DL. A prospective evaluation of the efficacy of preoperative coagulation testing. Ann Surg 1988; 208:554–557.

- Eagle KA, Coley CM, Newell JB, et al. Combining clinical and thallium data optimizes preoperative assessment of cardiac risk before major vascular surgery. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:859–866.

- Mangano DT, London MJ, Tubau JF, et al. Dipyridamole thallium-201 scintigraphy as a preoperative screening test. A reexamination of its predictive potential. Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. Circulation 1991; 84:493–502.

- Stratmann HG, Younis LT, Wittry MD, Amato M, Mark AL, Miller DD. Dipyridamole technetium 99m sestamibi myocardial tomography for preoperative cardiac risk stratification before major or minor nonvascular surgery. Am Heart J 1996; 132:536–541.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of Medical Testing for Cataract Surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:168–175.

- Hashimoto J, Nakahara T, Bai J, Kitamura N, Kasamatsu T, Kubo A. Preoperative risk stratification with myocardial perfusion imaging in intermediate and low-risk non-cardiac surgery. Circ J 2007; 71:1395–1400.

- Smetana GW. The conundrum of unnecessary preoperative testing. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1359–1361.

- Prasad V, Cifu A. Medical reversal: why we must raise the bar before adopting new technologies. Yale J Biol Med 2011; 84:471–478.

- Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JP. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA 2007; 298:2517–2526.

- Moscucci M. Medical reversal, clinical trials, and the “late” open artery hypothesis in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1643–1644.

- Coleman J, Menzel H, Katz E. Social processes in physicians’ adoption of a new drug. J Chronic Dis 1959; 9:1–19.

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282:1458–1465.

- Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA 2009; 301:831–841.

- Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al; CONSORT. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012; 10:28–55.

- Gattinoni L, Giomarelli P. Acquiring knowledge in intensive care: merits and pitfalls of randomized controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41:1460–1464.

- Levy JH, Szlam F, Wolberg AS, Winkler A. Clinical use of the activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time for screening: a review of the literature and current guidelines for testing. Clin Lab Med 2014; 34:453–477.

- Dale W, Hemmerich J, Moliski E, Schwarze ML, Tung A. Effect of specialty and recent experience on perioperative decision-making for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60:1889–1894.

- Underwood SR, Anagnostopoulos C, Cerqueira M, et al; British Cardiac Society, British Nuclear Cardiology Society, British Nuclear Medicine Society, Royal College of Physicians of London, Royal College of Physicians of London. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy: the evidence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2004; 31:261–291.

- Das MK, Pellikka PA, Mahoney DW, et al. Assessment of cardiac risk before nonvascular surgery: dobutamine stress echocardiography in 530 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:1647–1653.

- Meijboom WB, Mollet NR, Van Mieghem CA, et al. Pre-operative computed tomography coronary angiography to detect significant coronary artery disease in patients referred for cardiac valve surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:1658–1665.

- Russo V, Gostoli V, Lovato L, et al. Clinical value of multidetector CT coronary angiography as a preoperative screening test before non-coronary cardiac surgery. Heart 2007; 93:1591–1598.

- Schuetz GM, Zacharopoulou NM, Schlattmann P, Dewey M. Meta-analysis: noninvasive coronary angiography using computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:167–177.

- Bluemke DA, Achenbach S, Budoff M, et al. Noninvasive coronary artery imaging: magnetic resonance angiography and multidetector computed tomography angiography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention of the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Circulation 2008; 118:586–606.

- Nagel E, Lehmkuhl HB, Bocksch W, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of ischemia-induced wall motion abnormalities with the use of high-dose dobutamine stress MRI: comparison with dobutamine stress echocardiography. Circulation 1999; 99:763–770.

- Taylor H. Physicians’ use of clinical guidelines—and how to increase it. Healthcare News 2008; 8:32–55. www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/HI_HealthCareNews2008Vol8_Iss04.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Kenefick H, Lee J, Fleishman V. Improving physician adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Barriers and stragies for change. New England Healthcare Institute, February 2008. www.nehi.net/writable/publication_files/file/cpg_report_final.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Williams J, Cheung WY, Price DE, et al. Clinical guidelines online: do they improve compliance? Postgrad Med J 2004; 80:415–419.

- Wians F. Clinical laboratory tests: which, why, and what do the results mean? Lab Medicine 2009; 40:105–113.

- McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2795–2804.

- Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, et al; Authors/Task Force Members. 2014 ESC/ESA guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2383–2431.

- Eagle KA, Rihal CS, Mickel MC, Holmes DR, Foster ED, Gersh BJ. Cardiac risk of noncardiac surgery: influence of coronary disease and type of surgery in 3368 operations. CASS Investigators and University of Michigan Heart Care Program. Coronary Artery Surgery Study. Circulation 1997; 96:1882–1887.

- Farquhar CM, Kofa EW, Slutsky JR. Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Med J Aust 2002; 177:502–506.

- Prasad V, Cifu A, Ioannidis JP. Reversals of established medical practices: evidence to abandon ship. JAMA 2012; 307:37–38.

- Steinbrook R. Guidance for guidelines. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:331–333.

- Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Too little? Too much? Primary care physicians’ views on US health care: a brief report. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1582–1585.

- Brown SR, Brown J. Why do physicians order unnecessary preoperative tests? A qualitative study. Fam Med 2011; 43:338–343.

- LeCraw LL. Use of clinical practice guidelines in medical malpractice litigation. J Oncol Pract 2007; 3:254.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005; 293:2609–2617.

- Budetti PP. Tort reform and the patient safety movement: seeking common ground. JAMA 2005; 293:2660–2662.

- Bishop TF, Federman AD, Ross JS. Laboratory test ordering at physician offices with and without on-site laboratories. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25:1057–1063.

- Rosenthal E. Medical costs rise as retirees winter in Florida. The New York Times, Jan 31, 2015. http://nyti.ms/1vmjfa5. Accessed August 31, 2015.

Guidelines and practice advisories issued by several medical societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists,1 American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC),2 and Society of General Internal Medicine,3 advise against routine preoperative testing for patients undergoing low-risk surgical procedures. Such testing often includes routine blood chemistry, complete blood cell counts, measures of the clotting system, and cardiac stress testing.

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Dr. Nathan Houchens reviews the evidence against these measures.4

Despite a substantial body of evidence going back more than 2 decades that includes prospective randomized controlled trials,5–10 physicians continue to order unnecessary, ineffective, and costly tests in the perioperative period.11 The process of abandoning current medical practice—a phenomenon known as medical reversal12—often takes years,13 because it is more difficult to convince physicians to discontinue a current behavior than to implement a new one.14 The study of what makes physicians accept new therapies and abandon old ones began more than half a century ago.15

More recently, Cabana et al16 created a framework to understand why physicians do not follow clinical practice guidelines. Among the reasons are lack of familiarity or agreement with the contents of the guideline, lack of outcome expectancy, inertia of previous practice, and external barriers to implementation.

The rapid proliferation of guidelines in the past 20 years has led to numerous conflicting recommendations, many of which are based primarily on expert opinion.17 Guidelines based solely on randomized trials have also come under fire.18,19

In the case of preoperative testing, the recommendations are generally evidence-based and consistent. Why then do physicians appear to disregard the evidence? We propose several reasons why they might do so.

SOME PHYSICIANS ARE UNFAMILIAR WITH THE EVIDENCE

The complexity of the evidence summarized in guidelines has increased exponentially in the last decade, but physician time to assess the evidence has not increased. For example, the number of references in the executive summary of the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines increased from 96 in 2002 to 252 in 2014. Most of the recommendations are backed by substantial amounts of high-quality evidence. For example, there are 17 prospective and 13 retrospective studies demonstrating that routine testing with the prothrombin time and the partial thromboplastin time is not helpful in asymptomatic patients.20

Although compliance with medical evidence varies among specialties,21 most physicians do not have time to keep up with the ever-increasing amount of information. Specifically in the area of cardiac risk assessment, there has been a rapid proliferation of tests that can be used to assess cardiac risk.22–28 In a Harris Interactive survey from 2008, physicians reported not applying medical evidence routinely. One-third believed they would do it more if they had the time.29 Without information technology support to provide medical information at the point of care,30 especially in small practices, using evidence may not be practical. Simply making the information available online and not promoting it actively does not improve utilization.31

As a consequence, physicians continue to order unnecessary tests, even though they may not feel confident interpreting the results.32

PHYSICIANS MAY NOT BELIEVE THE EVIDENCE

A lack of transparency in evidence-based guidelines and, sometimes, a lack of flexibility and relevance to clinical practice are important barriers to physicians’ acceptance of and adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.30

Even experts who write guidelines may not be swayed by the evidence. For example, a randomized prospective trial of almost 6,000 patients reported that coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery does not affect long-term mortality rates.33 Based on this study, the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines2 advised against revascularization before noncardiac surgery exclusively to reduce perioperative cardiac events. Yet the same guidelines do recommend assessing for myocardial ischemia in patients with elevated risk and poor or unknown functional capacity, using a pharmacologic stress test. Based on the extent of the stress test abnormalities, coronary angiography and revascularization are then suggested for patients willing to undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention.2

The 2014 European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Anaesthesiology guidelines directly recommend revascularization before high-risk surgery, depending on the extent of a stress-induced perfusion defect.34 This recommendation relies on data from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry, which included almost 25,000 patients who underwent coronary angiography from 1975 through 1979. At a mean follow-up of 4.1 years, 1,961 patients underwent high-risk surgery. In this observational cohort, patients who underwent CABG had a lower risk of death and myocardial infarction after surgery.35 The reliance of medical societies34 on data that are more than 30 years old—when operative mortality rates and the treatment of coronary artery disease have changed substantially in the interim and despite the fact that this study did not test whether preoperative revascularization can reduce postoperative mortality—reflects a certain resistance to accept the results of the more recent and relevant randomized trial.33

Other physicians may also prefer to rely on selective data or to simply defer to guidelines that support their beliefs. Some physicians find that evidence-based guidelines are impractical and rigid and reduce their autonomy.36 For many physicians, trials that use surrogate end points and short-term outcomes are not sufficiently compelling to make them abandon current practice.37 Finally, when members of the guideline committees have financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry, or when corporations interested in the outcomes provide financial support for a trial’s development, the likelihood of a recommendation being trusted and used by physicians is drastically reduced.38

PRACTICING DEFENSIVELY

Even if physicians are familiar with the evidence and believe it, they may choose not to act on it. One reason is fear of litigation.

In court, attorneys can use guidelines as well as articles from medical journals as both exculpatory and inculpatory evidence. But they more frequently rely on the standard of care, or what most physicians would do under similar circumstances. If a patient has a bad outcome, such as a perioperative myocardial infarction or life-threatening bleeding, the defendant may assert that testing was unwarranted because guidelines do not recommend it or because the probability of such an outcome was low. However, because the outcome occurred, the jury may not believe that the probability was low enough not to consider, especially if expert witnesses testify that the standard of care would be to order the test.

In areas of controversy, physicians generally believe that erring on the side of more testing is more defensible in court.39 Indeed, following established practice traditions, learned during residency,11,40 may absolve physicians in negligence claims if the way medical care was delivered is supported by recognized and respected physicians.41

As a consequence, physicians prefer to practice the same way their peers do rather than follow the evidence. Unfortunately, the more procedures physicians perform for low-risk patients, the more likely these tests will become accepted as the legal standard of care.42 In this vicious circle, the new standard of care can increase the risk of litigation for others.43 Although unnecessary testing that leads to harmful invasive tests or procedures can also result in malpractice litigation, physicians may not consider this possibility.

FINANCIAL INCENTIVES

The threat of malpractice litigation provides a negative financial incentive to keep performing unnecessary tests, but there are a number of positive incentives as well.

First, physicians often feel compelled to order tests when they believe that physicians referring the patients want the tests done, or when they fear that not completing the tests could delay or cancel the scheduled surgery.40 Refusing to order the test could result in a loss of future referrals. In contrast, ordering tests allows them to meet expectations, preserve trust, and appear more valuable to referring physicians and their patients.

Insurance companies are complicit in these practices. Paying for unnecessary tests can create direct financial incentives for physicians or institutions that own on-site laboratories or diagnostic imaging equipment. Evidence shows that under those circumstances physicians do order more tests. Self-referral and referral to facilities where physicians have a financial interest is associated with increased healthcare costs.44 In addition to direct revenues for the tests performed, physicians may also bill for test interpretation, follow-up visits, and additional procedures generated from test results.

This may be one explanation why the ordering of cardiac tests (stress testing, echocardiography, vascular ultrasonography) by US physicians varies widely from state to state.45

RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE INAPPROPRIATE TESTING

To counter these influences, we propose a multifaceted intervention that includes the following:

- Establish preoperative clinics staffed by experts. Despite the large volume of potentially relevant evidence, the number of articles directly supporting or refuting preoperative laboratory testing is small enough that physicians who routinely engage in preoperative assessment should easily master the evidence.

- Identify local leaders who can convince colleagues of the evidence. Distribute evidence summaries or guidelines with references to major articles that support each recommendation.

- Work with clinical practice committees to establish new standards of care within the hospital. Establish hospital care paths to dictate and support local standards of care. Measure individual physician performance and offer feedback with the goal of reducing utilization.

- National societies should recommend that insurance companies remove inappropriate financial incentives. If companies deny payment for inappropriate testing, physicians will stop ordering it. Even requirements for preauthorization of tests should reduce utilization. The Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org) would be a good place to start.

Guidelines and practice advisories issued by several medical societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists,1 American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC),2 and Society of General Internal Medicine,3 advise against routine preoperative testing for patients undergoing low-risk surgical procedures. Such testing often includes routine blood chemistry, complete blood cell counts, measures of the clotting system, and cardiac stress testing.

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Dr. Nathan Houchens reviews the evidence against these measures.4

Despite a substantial body of evidence going back more than 2 decades that includes prospective randomized controlled trials,5–10 physicians continue to order unnecessary, ineffective, and costly tests in the perioperative period.11 The process of abandoning current medical practice—a phenomenon known as medical reversal12—often takes years,13 because it is more difficult to convince physicians to discontinue a current behavior than to implement a new one.14 The study of what makes physicians accept new therapies and abandon old ones began more than half a century ago.15

More recently, Cabana et al16 created a framework to understand why physicians do not follow clinical practice guidelines. Among the reasons are lack of familiarity or agreement with the contents of the guideline, lack of outcome expectancy, inertia of previous practice, and external barriers to implementation.

The rapid proliferation of guidelines in the past 20 years has led to numerous conflicting recommendations, many of which are based primarily on expert opinion.17 Guidelines based solely on randomized trials have also come under fire.18,19

In the case of preoperative testing, the recommendations are generally evidence-based and consistent. Why then do physicians appear to disregard the evidence? We propose several reasons why they might do so.

SOME PHYSICIANS ARE UNFAMILIAR WITH THE EVIDENCE

The complexity of the evidence summarized in guidelines has increased exponentially in the last decade, but physician time to assess the evidence has not increased. For example, the number of references in the executive summary of the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines increased from 96 in 2002 to 252 in 2014. Most of the recommendations are backed by substantial amounts of high-quality evidence. For example, there are 17 prospective and 13 retrospective studies demonstrating that routine testing with the prothrombin time and the partial thromboplastin time is not helpful in asymptomatic patients.20

Although compliance with medical evidence varies among specialties,21 most physicians do not have time to keep up with the ever-increasing amount of information. Specifically in the area of cardiac risk assessment, there has been a rapid proliferation of tests that can be used to assess cardiac risk.22–28 In a Harris Interactive survey from 2008, physicians reported not applying medical evidence routinely. One-third believed they would do it more if they had the time.29 Without information technology support to provide medical information at the point of care,30 especially in small practices, using evidence may not be practical. Simply making the information available online and not promoting it actively does not improve utilization.31

As a consequence, physicians continue to order unnecessary tests, even though they may not feel confident interpreting the results.32

PHYSICIANS MAY NOT BELIEVE THE EVIDENCE

A lack of transparency in evidence-based guidelines and, sometimes, a lack of flexibility and relevance to clinical practice are important barriers to physicians’ acceptance of and adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.30

Even experts who write guidelines may not be swayed by the evidence. For example, a randomized prospective trial of almost 6,000 patients reported that coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery does not affect long-term mortality rates.33 Based on this study, the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines2 advised against revascularization before noncardiac surgery exclusively to reduce perioperative cardiac events. Yet the same guidelines do recommend assessing for myocardial ischemia in patients with elevated risk and poor or unknown functional capacity, using a pharmacologic stress test. Based on the extent of the stress test abnormalities, coronary angiography and revascularization are then suggested for patients willing to undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention.2

The 2014 European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Anaesthesiology guidelines directly recommend revascularization before high-risk surgery, depending on the extent of a stress-induced perfusion defect.34 This recommendation relies on data from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study registry, which included almost 25,000 patients who underwent coronary angiography from 1975 through 1979. At a mean follow-up of 4.1 years, 1,961 patients underwent high-risk surgery. In this observational cohort, patients who underwent CABG had a lower risk of death and myocardial infarction after surgery.35 The reliance of medical societies34 on data that are more than 30 years old—when operative mortality rates and the treatment of coronary artery disease have changed substantially in the interim and despite the fact that this study did not test whether preoperative revascularization can reduce postoperative mortality—reflects a certain resistance to accept the results of the more recent and relevant randomized trial.33

Other physicians may also prefer to rely on selective data or to simply defer to guidelines that support their beliefs. Some physicians find that evidence-based guidelines are impractical and rigid and reduce their autonomy.36 For many physicians, trials that use surrogate end points and short-term outcomes are not sufficiently compelling to make them abandon current practice.37 Finally, when members of the guideline committees have financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry, or when corporations interested in the outcomes provide financial support for a trial’s development, the likelihood of a recommendation being trusted and used by physicians is drastically reduced.38

PRACTICING DEFENSIVELY

Even if physicians are familiar with the evidence and believe it, they may choose not to act on it. One reason is fear of litigation.

In court, attorneys can use guidelines as well as articles from medical journals as both exculpatory and inculpatory evidence. But they more frequently rely on the standard of care, or what most physicians would do under similar circumstances. If a patient has a bad outcome, such as a perioperative myocardial infarction or life-threatening bleeding, the defendant may assert that testing was unwarranted because guidelines do not recommend it or because the probability of such an outcome was low. However, because the outcome occurred, the jury may not believe that the probability was low enough not to consider, especially if expert witnesses testify that the standard of care would be to order the test.

In areas of controversy, physicians generally believe that erring on the side of more testing is more defensible in court.39 Indeed, following established practice traditions, learned during residency,11,40 may absolve physicians in negligence claims if the way medical care was delivered is supported by recognized and respected physicians.41

As a consequence, physicians prefer to practice the same way their peers do rather than follow the evidence. Unfortunately, the more procedures physicians perform for low-risk patients, the more likely these tests will become accepted as the legal standard of care.42 In this vicious circle, the new standard of care can increase the risk of litigation for others.43 Although unnecessary testing that leads to harmful invasive tests or procedures can also result in malpractice litigation, physicians may not consider this possibility.

FINANCIAL INCENTIVES

The threat of malpractice litigation provides a negative financial incentive to keep performing unnecessary tests, but there are a number of positive incentives as well.

First, physicians often feel compelled to order tests when they believe that physicians referring the patients want the tests done, or when they fear that not completing the tests could delay or cancel the scheduled surgery.40 Refusing to order the test could result in a loss of future referrals. In contrast, ordering tests allows them to meet expectations, preserve trust, and appear more valuable to referring physicians and their patients.

Insurance companies are complicit in these practices. Paying for unnecessary tests can create direct financial incentives for physicians or institutions that own on-site laboratories or diagnostic imaging equipment. Evidence shows that under those circumstances physicians do order more tests. Self-referral and referral to facilities where physicians have a financial interest is associated with increased healthcare costs.44 In addition to direct revenues for the tests performed, physicians may also bill for test interpretation, follow-up visits, and additional procedures generated from test results.

This may be one explanation why the ordering of cardiac tests (stress testing, echocardiography, vascular ultrasonography) by US physicians varies widely from state to state.45

RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE INAPPROPRIATE TESTING

To counter these influences, we propose a multifaceted intervention that includes the following:

- Establish preoperative clinics staffed by experts. Despite the large volume of potentially relevant evidence, the number of articles directly supporting or refuting preoperative laboratory testing is small enough that physicians who routinely engage in preoperative assessment should easily master the evidence.

- Identify local leaders who can convince colleagues of the evidence. Distribute evidence summaries or guidelines with references to major articles that support each recommendation.

- Work with clinical practice committees to establish new standards of care within the hospital. Establish hospital care paths to dictate and support local standards of care. Measure individual physician performance and offer feedback with the goal of reducing utilization.

- National societies should recommend that insurance companies remove inappropriate financial incentives. If companies deny payment for inappropriate testing, physicians will stop ordering it. Even requirements for preauthorization of tests should reduce utilization. The Choosing Wisely campaign (www.choosingwisely.org) would be a good place to start.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al; American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e77–e137.

- Society of General Internal Medicine. Don’t perform routine pre-operative testing before low-risk surgical procedures. Choosing Wisely. An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. September 12, 2013. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/society-general-internal-medicine-routine-preoperative-testing-before-low-risk-surgery/. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- Houchens N. Should healthy patients undergoing low-risk, elective, noncardiac surgery undergo routine preoperative laboratory testing? Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:664–666.

- Rohrer MJ, Michelotti MC, Nahrwold DL. A prospective evaluation of the efficacy of preoperative coagulation testing. Ann Surg 1988; 208:554–557.

- Eagle KA, Coley CM, Newell JB, et al. Combining clinical and thallium data optimizes preoperative assessment of cardiac risk before major vascular surgery. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:859–866.

- Mangano DT, London MJ, Tubau JF, et al. Dipyridamole thallium-201 scintigraphy as a preoperative screening test. A reexamination of its predictive potential. Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. Circulation 1991; 84:493–502.

- Stratmann HG, Younis LT, Wittry MD, Amato M, Mark AL, Miller DD. Dipyridamole technetium 99m sestamibi myocardial tomography for preoperative cardiac risk stratification before major or minor nonvascular surgery. Am Heart J 1996; 132:536–541.

- Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. Study of Medical Testing for Cataract Surgery. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:168–175.

- Hashimoto J, Nakahara T, Bai J, Kitamura N, Kasamatsu T, Kubo A. Preoperative risk stratification with myocardial perfusion imaging in intermediate and low-risk non-cardiac surgery. Circ J 2007; 71:1395–1400.

- Smetana GW. The conundrum of unnecessary preoperative testing. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1359–1361.

- Prasad V, Cifu A. Medical reversal: why we must raise the bar before adopting new technologies. Yale J Biol Med 2011; 84:471–478.

- Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JP. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA 2007; 298:2517–2526.

- Moscucci M. Medical reversal, clinical trials, and the “late” open artery hypothesis in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1643–1644.

- Coleman J, Menzel H, Katz E. Social processes in physicians’ adoption of a new drug. J Chronic Dis 1959; 9:1–19.

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282:1458–1465.

- Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA 2009; 301:831–841.

- Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al; CONSORT. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012; 10:28–55.

- Gattinoni L, Giomarelli P. Acquiring knowledge in intensive care: merits and pitfalls of randomized controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41:1460–1464.

- Levy JH, Szlam F, Wolberg AS, Winkler A. Clinical use of the activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time for screening: a review of the literature and current guidelines for testing. Clin Lab Med 2014; 34:453–477.

- Dale W, Hemmerich J, Moliski E, Schwarze ML, Tung A. Effect of specialty and recent experience on perioperative decision-making for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60:1889–1894.