User login

Medicaid Insurance Is Associated With Larger Curves in Patients Who Require Scoliosis Surgery

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

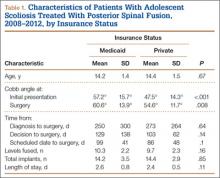

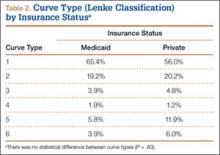

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.

17. Kasper MJ, Robbins L, Root L, Peterson MG, Allegrante JP. A musculoskeletal outreach screening, treatment, and education program for urban minority children. Arthritis Care Res. 1993;6(3):126-133.

18. Berman S, Dolins J, Tang SF, Yudkowsky B. Factors that influence the willingness of private primary care pediatricians to accept more Medicaid patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):239-248.

19. Sommers BD. Protecting low-income children’s access to care: are physician visits associated with reduced patient dropout from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e36-e42.

20. Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):304-310.

21. Sedlis SP, Fisher VJ, Tice D, Esposito R, Madmon L, Steinberg EH. Racial differences in performance of invasive cardiac procedures in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):899-901.

22. Mitchell JB, McCormack LA. Time trends in late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer. Differences by race/ethnicity and income. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1220-1224.

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

Rising health care costs have led many health insurers to limit benefits, which may be a problem for children in need of specialty care. Uninsured children have poorer access to specialty care than insured children. Children with public health coverage have better access to specialty care than uninsured children but inferior access compared with privately insured children.1,2 It is well documented that children with government insurance have limited access to orthopedic care for fractures, ligamentous knee injuries, and other injuries.1,3-5 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) differs from many other conditions managed by pediatric orthopedists, as it may be progressive, with management becoming increasingly more complex as the curve magnitude increases.6 The ability to access care earlier in the disease process may allow for earlier nonoperative interventions, such as bracing. For patients who require spinal fusion, earlier diagnosis and referral to a specialist could potentially result in shorter fusions and preserve distal motion segments. The ability to access the health care system in a timely fashion would therefore be of utmost importance for patients with scoliosis.

The literature on AIS is lacking in studies focused on care access based on insurance coverage and the potential impact that this may have on curve progression.7-9 We conducted a study to determine whether there is a difference between patients with and without private insurance who present to a busy urban pediatric orthopedic practice for management of scoliosis that eventually resulted in surgical treatment.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients (age, 10-18 years) who underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for newly diagnosed AIS between 2008 and 2012. We excluded patients treated with growing spine instrumentation (growing rods), patients younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at presentation, and patients without adequate radiographs or clinical data, including insurance status. To focus on newly diagnosed scoliosis, we also excluded patients who had been seen for second opinions or whose scoliosis had been managed elsewhere in the past. Patients with syndromic, neuromuscular, or congenital scoliosis were also excluded.

Medical records were checked to ascertain time from initial evaluation to decision for surgery, time from recommendation for surgery until actual procedure, and insurance status. Distance traveled was figured from patients’ home addresses. Cobb angles were calculated from initial preoperative and final preoperative posteroanterior (PA) radiographs. Curves as seen on PA, lateral, and maximal effort, supine bending thoracic and lumbar radiographs from the initial preoperative visit were classified using the system of Lenke and colleagues.10 Hospital records were queried to determine number of levels fused at surgery, number of implants placed, and length of stay. Patients were evaluated without prior screening of insurance status and without prior consultation with referring physicians. Surgical procedures were scheduled on a first-come, first-served basis without preference for insurance status.

Results

We identified 135 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed AIS treated with PSF by our group between January 2008 and December 2012 (Table 1). Sixty-one percent had private insurance; 39% had Medicaid. There was no difference in age or ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score between groups. Mean (SD) Cobb angle at initial presentation was 47.5° (14.3°) (range, 18.0°-86.0°) for the private insurance group and 57.2° (15.7°) (range, 23.0°-95.0°) for the Medicaid group (P < .0001). At time of surgery, mean (SD) Cobb angles were 54.6° (11.7°) and 60.6° (13.9°) for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively (P = .008). There was no difference in curve types (Lenke and colleagues10 classification) between groups (Table 2, P = .83). Medicaid patients traveled a shorter mean (SD) distance for care, 56.3 (57.0) miles, versus 73.7 (66.7) miles (P = .05). There was no statistical difference (P = .14) in mean (SD) surgical wait time from surgery recommendation to actual surgery, 103.1 (62.4) days and 128.8 (137.5) days for the private insurance and Medicaid groups, respectively. The difference between patient groups in mean (SD) number of levels fused did not reach statistical significance (P = .16), 10.3 (2.2) levels for the Medicaid group and 9.7 (2.3) levels for the private insurance group. Mean (SD) estimated blood loss was higher for Medicaid patients, 445.7 (415.9) mL versus 335.1 (271.5) mL (P = .06), though there was no difference in use of posterior column osteotomies between groups. There was no difference (P = .11) in mean (SD) length of hospital stay between Medicaid patients, 2.6 (0.8) days, and private insurance patients, 2.4 (0.5) days.

Discussion

According to an extensive body of literature, patients with government insurance have limited access to specialty care.1,11,12 Medicaid-insured children in need of orthopedic care are no exception. Sabharwal and colleagues13 examined a database of pediatric fracture cases and found that 52% of the privately insured patients and 22% of the publicly insured patients received orthopedic care (P = .013).13 When Pierce and colleagues14 called 42 orthopedic practices regarding a fictitious 14-year-old patient with an anterior cruciate ligament tear, 38 offered an appointment within 2 weeks to a privately insured patient, and 6 offered such an appointment to a publicly insured patient. Skaggs and colleagues4 surveyed 230 orthopedic practices nationally and found that Medicaid-insured children had limited access to orthopedic care; 41 practices (18%) would not see a child with Medicaid under any circumstances. Using a fictitious case of a 10-year-old boy with a forearm fracture, Iobst and colleagues3 tried making an appointment at 100 orthopedic offices. Eight gave an appointment within 1 week to a Medicaid-insured patient, and 36 gave an appointment to a privately insured patient.3

There are few data regarding insurance status and scoliosis care in children. Spinal deformity differs from simple fractures and ligamentous injuries, as timely care may result in a less invasive treatment (bracing) if the curvature is caught early. Goldstein and colleagues9 recently evaluated 642 patients who presented for scoliosis evaluation over a 10-year period. There was no difference in curve magnitudes between patients with and without Medicaid insurance. Thirty-two percent of these patients were evaluated for a second opinion, and the authors chose not to subdivide patients on the basis of curve severity and treatment needed, noting only no difference between groups. There was no discussion of the potential difference between patients with and without private insurance with respect to surgically versus nonsurgically treated curves. We wanted to focus specifically on patients who required surgical intervention, as our experience has been that many patients with government insurance present with either very mild scoliosis (10°) or very large curves that were not identified because of lack of primary care access or inadequate school screening. Although summing these 2 groups would result in a similar average, they would represent a different cohort than patients with curves along a bell curve. Furthermore, it is the group of patients who would require surgical intervention that is so critical to identify early in order to intervene.

Our data suggest a difference in presenting curves between patients with and without private insurance. The approximately 10° difference between patient groups in this study could potentially represent the difference between bracing and surgery. Furthermore, Miyanji and colleagues6 evaluated the relationship between Cobb angle and health care consumption and correlated larger curve magnitudes with more levels fused, longer surgeries, and higher rates of transfusion. Specifically, every 10° increase in curve magnitude resulted in 7.8 more minutes of operative time, 0.3 extra levels fused, and 1.5 times increased risk for requiring a blood transfusion.

Cho and Egorova15 recently evaluated insurance status with respect to surgical outcomes using a national inpatient database and found that 42.4% of surgeries for AIS in children with Medicaid had fusions involving 9 or more levels, whereas only 33.6% of privately insured patients had fusions of 9 or more levels. There was no difference in osteotomy or reoperation for pseudarthrosis between groups, but there was a slightly higher rate of infectious (1.1% vs 0.6%) and hemorrhagic (2.5% vs 1.7%) complications in the Medicaid group. Hospital stay was longer in patients with Medicaid, though complications were not different between groups.

The mean difference in the magnitude of the curves treated in our study was not more than 10° between patients with and without Medicaid, perhaps explaining the lack of a statistically significant difference in number of levels fused between groups. Although the groups were similar with respect to the percentage requiring posterior column spinal osteotomies, we noted a difference in estimated blood loss between groups, likely explained by the fact that a junior surgeon was added just before initiation of the study period, potentially skewing the estimated blood loss as this surgeon gained experience. Payer status has been correlated to length of hospital stay in children with scoliosis. Vitale and colleagues8 reviewed the effect of payer status on surgical outcomes in 3606 scoliosis patients from a statewide database in California and concluded that, compared with patients having all other payment sources, Medicaid patients had higher odds for complications and longer hospital stay. Our hospital has adopted a highly coordinated care pathway that allows for discharge on postoperative day 2, likely explaining the lack of any difference in postoperative stay.16

The disparity in curve magnitudes among patients with and without private insurance is striking and probably multifactorial. Very likely, the combination of schools with limited screening programs within urban or rural school systems,17 restricted access to pediatricians,18,19 and longer waits to see orthopedic specialists20 all contribute to this disparity. It should be noted that school screening is mandatory in our state. This discrepancy may be related to a previously established tendency in minority populations toward waiting longer to seek care and refusing surgical recommendations, though we were unable to query socioeconomic factors such as race and household income.21,22 It is clearly important to increase access to care for underinsured patients with scoliosis. A comprehensive approach, including providing better education in the schools, establishing communication with referring primary care providers, and increasing access through more physicians or physician extenders, is likely needed. Orthopedists should perhaps treat scoliosis evaluation with the same sense of urgency given to minor fractures, and primary care providers should try to ensure that appropriate referrals for scoliosis are made. Also curious was the shorter travel distance for Medicaid patients versus private insurance patients in this study. We hypothesize this is related to our urban location and its large Medicaid population.

Our study had several limitations. Our electronic medical records (EMR) system does not store data related to the time a patient calls for an initial appointment, limiting our ability to determine how long patients waited for their initial consultation. Furthermore, the decision to undergo surgery is multifactorial and cannot be simplified into time from initial recommendation to surgery, as some patients delay surgery because of school or other obligations. These data should be reasonably consistent over time, as patients seen in the early spring in both groups may delay surgery until the summer, and those diagnosed in June may prefer earlier surgery.

Summary

Children with AIS are at risk for curve progression. Therefore, delays in providing timely care may result in worsening scoliosis. Compared with private insurance patients, Medicaid patients presented with larger curve magnitudes. Further study is needed to better delineate ways to improve care access for patients with scoliosis in communities with larger Medicaid populations.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.

17. Kasper MJ, Robbins L, Root L, Peterson MG, Allegrante JP. A musculoskeletal outreach screening, treatment, and education program for urban minority children. Arthritis Care Res. 1993;6(3):126-133.

18. Berman S, Dolins J, Tang SF, Yudkowsky B. Factors that influence the willingness of private primary care pediatricians to accept more Medicaid patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):239-248.

19. Sommers BD. Protecting low-income children’s access to care: are physician visits associated with reduced patient dropout from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e36-e42.

20. Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):304-310.

21. Sedlis SP, Fisher VJ, Tice D, Esposito R, Madmon L, Steinberg EH. Racial differences in performance of invasive cardiac procedures in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):899-901.

22. Mitchell JB, McCormack LA. Time trends in late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer. Differences by race/ethnicity and income. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1220-1224.

1. Skaggs DL. Less access to care for children with Medicaid. Orthopedics. 2003;26(12):1184, 1186.

2. Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194.

3. Iobst C, King W, Baitner A, Tidwell M, Swirsky S, Skaggs DL. Access to care for children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(3):244-247.

4. Skaggs DL, Lehmann CL, Rice C, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with Medicaid versus private insurance: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(3):400-404.

5. Skaggs DL, Oda JE, Lerman L, et al. Insurance status and delay in orthotic treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(1):94-97.

6. Miyanji F, Slobogean GP, Samdani AF, et al. Is larger scoliosis curve magnitude associated with increased perioperative health-care resource utilization? A multicenter analysis of 325 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):809-813.

7. Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13(2):116-123.

8. Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hyman JE, Skaggs DL, Roye DP, Vitale MG. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: a review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):393-399.

9. Goldstein RY, Joiner ER, Skaggs DL. Insurance status does not predict curve magnitude in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at first presentation to an orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(1):39-42.

10. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

11. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine. 2009;34(18):1956-1962.

12. Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America’s children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 2):989-997.

13. Sabharwal S, Zhao C, McClemens E, Kaufmann A. Pediatric orthopaedic patients presenting to a university emergency department after visiting another emergency department: demographics and health insurance status. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):690-694.

14. Pierce TR, Mehlman CT, Tamai J, Skaggs DL. Access to care for the adolescent anterior cruciate ligament patient with Medicaid versus private insurance. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(3):245-248.

15. Cho SK, Egorova NN. The association between insurance status and complications, length of stay, and costs for pediatric idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2015;40(4):247-256.

16. Fletcher ND, Shourbaji N, Mitchell PM, Oswald TS, Devito DP, Bruce RW Jr. Clinical and economic implications of early discharge following posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2014;8(3):257-263.

17. Kasper MJ, Robbins L, Root L, Peterson MG, Allegrante JP. A musculoskeletal outreach screening, treatment, and education program for urban minority children. Arthritis Care Res. 1993;6(3):126-133.

18. Berman S, Dolins J, Tang SF, Yudkowsky B. Factors that influence the willingness of private primary care pediatricians to accept more Medicaid patients. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 pt 1):239-248.

19. Sommers BD. Protecting low-income children’s access to care: are physician visits associated with reduced patient dropout from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e36-e42.

20. Bisgaier J, Polsky D, Rhodes KV. Academic medical centers and equity in specialty care access for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):304-310.

21. Sedlis SP, Fisher VJ, Tice D, Esposito R, Madmon L, Steinberg EH. Racial differences in performance of invasive cardiac procedures in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):899-901.

22. Mitchell JB, McCormack LA. Time trends in late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer. Differences by race/ethnicity and income. Med Care. 1997;35(12):1220-1224.

Open Carpal Tunnel Release With Use of a Nasal Turbinate Speculum

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11

Endoscopic CTR (ECTR) techniques were developed in an effort to reduce complications, scar sensitivity, and pillar pain and facilitate more rapid return to work.12-17 Outcome studies have demonstrated that both open and endoscopic releases yield patient-reported subjective improvements over preoperative symptoms.18-22 A randomized, controlled trial by Trumble and colleagues23 in 2002 found that ECTR led to improved patient outcomes in the early postoperative period (first 3 months), though differences in outcomes were reduced at final follow-up. More recently (2007), a Cochrane review of 33 trials concluded there was no strong evidence favoring use of alternative techniques over OCTR.3 Further, OCTR has been found to be technically less demanding and associated with decreased complications and costs.24

Indications

The benefit of median nerve decompression at the wrist for CTS is clear.6,7 Indications for surgery in patients with CTS include persistent symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, objective sensory disturbance or motor weakness, and thenar atrophy. Symptomatic response to corticosteroid injection is predictive of success after carpal tunnel surgery.25 More than 87% of patients who gain symptomatic relief from corticosteroid injection have an excellent surgical outcome.

Technique

OCTR allows direct visualization of the TCL and the distal volar forearm fascia (DVFF) and evaluation for the presence of anomalous branching patterns of the median nerve. OCTR traditionally was performed through a 4- to 5-cm longitudinal incision extending from the wrist crease proximally to the Kaplan cardinal line distally. The mini-open technique is identical with the exception of incision length. We routinely use a 2.5- to 3-cm incision. Regardless of incision length, each OCTR should proceed through the same reproducible steps.

We perform OCTR under tourniquet control. Choice of anesthesia is surgeon and patient preference. We prefer local anesthesia with conscious sedation. After conscious sedation is administered, we infiltrate the carpal tunnel and surrounding subcutaneous tissue with 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

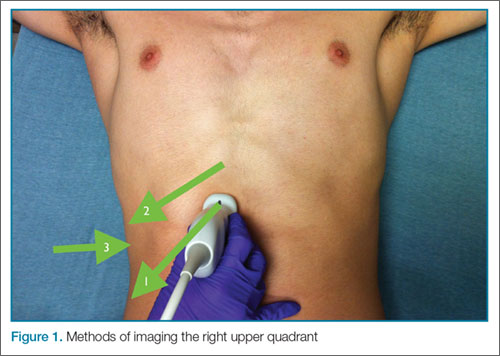

A 2.5- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the radial border of the ring finger from the Kaplan cardinal line26 and extending about 3 cm proximally toward the wrist flexion crease ulnar to the palmaris longus if present (Figure 1).

After the skin is incised longitudinally, the subcutaneous fat is mobilized and cutaneous sensory branches identified and protected. The underlying superficial palmar fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. The underlying midportion of the TCL is now visualized.

Transverse Carpal Ligament Release

Occasionally, the investing fascia along the ulnar edge of the thenar musculature is mobilized radialward (if the thenar musculature is well developed) to visualize the proximal limb of the TCL. Injury to any anomalous motor branch of the median nerve is avoided by directly visualizing and then incising the TCL (Figure 2). The TCL is incised along its ulnar border just radial to the hook of hamate from distal to proximal in line with the radial border of the ring finger. Staying near the ulnar attachment of the TCL keeps the plane of ligament division farther away from the median nerve and its recurrent motor branches. Although the ulnar neurovascular bundle typically resides ulnar to the hook of hamate in the canal of Guyon, the surgeon must be aware that it can be located radial to the hook in some instances.27,28 In the elderly, the ulnar artery may be tortuous and enter the field and require retraction. The TCL is incised distally until the sentinel fat pad, which marks the superficial palmar arterial arch, is visualized. This bed of adipose tissue marks the distal edge of the TCL.29

Proximally, subcutaneous tissues above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF are mobilized to about 2 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease to create a plane for the fine long nasal turbinate speculum. The nasal turbinate speculum is then inserted into this plane above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF (Figure 3). Once inserted to the level of the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF, the speculum is opened.

Topside visualization is now encountered with the ulnar neurovascular bundle protected by the ulnar blade of the speculum. A long-handle scalpel is used to incise the TCL and the DVFF under direct visualization from proximal to distal in line with the previously completed distal release (Figure 4). As the nasal turbinate speculum is stretching the TCL and putting it under tension, the TCL can be heard splitting as it is being incised. Once the TCL and the DVFF are divided, the speculum is slowly closed and removed. Wide diastasis of the radial and ulnar leaflets of the TCL and the DVFF is directly visualized. Complete decompression of the median nerve from the distal forearm fascia to the superficial palmar arch is confirmed.

Adhesions between the undersurface of the radial leaflet and the flexor tendons and median nerve are mobilized. The median nerve is assessed for “hourglass” morphology or atrophy. The flexor tendons can be swept radialward with a free elevator to inspect the floor of the carpal tunnel. Flexor tenosynovectomy is not routinely performed. The incision is closed with interrupted simple sutures using 4-0 nylon.

Study Results

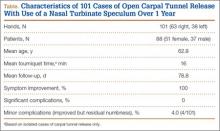

This study was conducted at Hand Surgery PC, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Tufts University School of Medicine. Over a 10-month interval, 101 consecutive mini-OCTRs (63 right hands, 38 left hands) were performed with this proximal release modification in 88 patients (51 females, 37 males) by Dr. Ruchelsman and Dr. Belsky (Table). CTRs performed in the setting of wrist and/or carpal trauma were excluded. Mean age was 62.8 years. Mean follow-up was 11.3 weeks (~3 months). For isolated cases of CTR, mean tourniquet time was 16 minutes. CTS symptoms were relieved in all patients with a high degree of satisfaction as measured with history and examination findings at follow-up visits. There were no major complications (eg, infection, neural or vascular damage, severe residual pain). Four patients reported minor residual numbness in the fingers at latest follow-up but nevertheless had major improvement over preoperative baseline. These 4 patients had preoperative electromyograms or nerve conduction studies documenting the extent of their disease. There was 1 case of minor wound complication. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a 1-cm wound opening, which closed with local wound care. The patient did not develop any drainage, infection, bleeding, or neurologic symptoms.

Discussion

Open release of the TCL—the gold standard of surgical treatment for CTS—produces reliable symptom relief in the vast majority of patients.25,30 Given that the most common complication of carpal tunnel surgery is incomplete release of the TCL,31,32 this technique, which uses a nasal turbinate speculum to better visualize the median nerve, could potentially reduce the reoperation rate. The nasal turbinate speculum allows the surgeon to see the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF. In addition, as the complete release can be visualized, there is minimal chance of injury.

The 2007 Cochrane review3 found no strong evidence supporting replacing OCTR with endoscopic techniques. Previous investigators have questioned the utility of ECTR given that it is higher in cost and more resource-intensive than OCTR1,33,34 and is associated with higher rates of certain complications.5,22,35-37 A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials found a higher rate of reversible nerve damage with an odds ratio of 3.1 for ECTR versus OCTR.35 A more recent (2006) review of more than 80 studies found transient neurapraxias in 1.45% of ECTR cases and 0.25% of OCTR cases.5 The same study reported overall complication rates (reversible and major neurovascular structural injuries) of 0.74% for OCTR and 1.63% for ECTR (P < .005). Another limitation of ECTR is that endoscopic techniques require a higher degree of surgical skill, which makes teaching residents and fellows more challenging.

The novel nasal turbinate speculum technique presented here is easily reproducible and allows first-time surgeons to visualize all important structures. Given that this technique does not require an endoscope or an endoscope-viewing tower, it is likely more cost-effective and requires less time for turnover between cases. Patients obtain good relief of their CTS symptoms with this technique, and most return to their daily activities within weeks after operation.

1. Ono S, Clapham PJ, Chung KC. Optimal management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3(4):255-261.

2. Concannon MJ, Brownfield ML, Puckett CL. The incidence of recurrence after endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1662-1665.

3. Scholten RJ, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BM, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003905.

4. In memoriam Sir James Learmonth, K.C.V.O., C.B.E., hon. F.R.C.S. (1895-1967). Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1967;41(5):438-439.

5. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

6. Jarvik JG, Comstock BA, Kliot M, et al. Surgery versus non-surgical therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomised parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9695):1074-1081.

7. Verdugo RJ, Salinas RA, Castillo JL, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD001552.

8. Garland H, Langworth EP, Taverner D, et al. Surgical treatment for the carpal tunnel syndrome. Lancet. 1964;1(7343):1129-1130.

9. Gerritsen AA, de Vet HC, Scholten RJ, et al. Splinting vs surgery in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1245-1251.

10. Gelberman RH, Hergenroeder PT, Hargens AR, et al. The carpal tunnel syndrome. A study of carpal canal pressures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(3):380-383.

11. Sucher BM. Myofascial manipulative release of carpal tunnel syndrome: documentation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93(12):1273-1278.

12. Pereira EE, Miranda DA, Sere I, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a 2-portal-modified technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2010;14(4):263-265.

13. Louis DS, Greene TL, Noellert RC. Complications of carpal tunnel surgery. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(3):352-356.

14. Mirza MA, King ET Jr, Tanveer S. Palmar uniportal extrabursal endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(1):82-90.

15. Brown MG, Keyser B, Rothenberg ES. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):1009-1011.

16. Agee JM, McCarroll HR Jr, Tortosa RD, et al. Endoscopic release of the carpal tunnel: a randomized prospective multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):987-995.

17. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, et al. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

18. Ghaly RF, Saban KL, Haley DA, et al. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release surgery: report of patient satisfaction. Neurol Res. 2000;22(6):551-555.

19. Lee WP, Plancher KD, Strickland JW. Carpal tunnel release with a small palmar incision. Hand Clin. 1996;12(2):271-284.

20. Biyani A, Downes EM. An open twin incision technique of carpal tunnel decompression with reduced incidence of scar tenderness. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18(3):331-334.

21. Brown RA, Gelberman RH, Seiler JG 3rd, et al. Carpal tunnel release. A prospective, randomized assessment of open and endoscopic methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(9):1265-1275.

22. Chow JC. Endoscopic release of the carpal ligament for carpal tunnel syndrome: 22-month clinical result. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):288-296.

23. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, et al. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1107-1115.

24. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, et al. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.

25. Edgell SE, McCabe SJ, Breidenbach WC, et al. Predicting the outcome of carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(2):255-261.

26. Vella JC, Hartigan BJ, Stern PJ. Kaplan’s cardinal line. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):912-918.

27. Kwon JY, Kim JY, Hong JT, et al. Position change of the neurovascular structures around the carpal tunnel with dynamic wrist motion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50(4):377-380.

28. Netscher D, Polsen C, Thornby J, et al. Anatomic delineation of the ulnar nerve and ulnar artery in relation to the carpal tunnel by axial magnetic resonance imaging scanning. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(2):273-276.

29. Madhav TJ, To P, Stern PJ. The palmar fat pad is a reliable intraoperative landmark during carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(7):1204-1209.

30. Kulick MI, Gordillo G, Javidi T, et al. Long-term analysis of patients having surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(1):59-66.

31. Bland JD. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36(2):167-171.

32. MacDonald RI, Lichtman DM, Hanlon JJ, et al. Complications of surgical release for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(1):70-76.

33. Atroshi I, Larsson GU, Ornstein E, Hofer M, Johnsson R, Ranstam J. Outcomes of endoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome among employed patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7556):1473.

34. Ferdinand RD, MacLean JG. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(3):375-379.

35. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1137-1146.

36. Murphy RX Jr, Jennings JF, Wukich DK. Major neurovascular complications of endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19(1):114-118.

37. Palmer DH, Paulson JC, Lane-Larsen CL, et al. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a comparison of two techniques with open release. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(5):498-508.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11

Endoscopic CTR (ECTR) techniques were developed in an effort to reduce complications, scar sensitivity, and pillar pain and facilitate more rapid return to work.12-17 Outcome studies have demonstrated that both open and endoscopic releases yield patient-reported subjective improvements over preoperative symptoms.18-22 A randomized, controlled trial by Trumble and colleagues23 in 2002 found that ECTR led to improved patient outcomes in the early postoperative period (first 3 months), though differences in outcomes were reduced at final follow-up. More recently (2007), a Cochrane review of 33 trials concluded there was no strong evidence favoring use of alternative techniques over OCTR.3 Further, OCTR has been found to be technically less demanding and associated with decreased complications and costs.24

Indications

The benefit of median nerve decompression at the wrist for CTS is clear.6,7 Indications for surgery in patients with CTS include persistent symptoms despite nonoperative treatment, objective sensory disturbance or motor weakness, and thenar atrophy. Symptomatic response to corticosteroid injection is predictive of success after carpal tunnel surgery.25 More than 87% of patients who gain symptomatic relief from corticosteroid injection have an excellent surgical outcome.

Technique

OCTR allows direct visualization of the TCL and the distal volar forearm fascia (DVFF) and evaluation for the presence of anomalous branching patterns of the median nerve. OCTR traditionally was performed through a 4- to 5-cm longitudinal incision extending from the wrist crease proximally to the Kaplan cardinal line distally. The mini-open technique is identical with the exception of incision length. We routinely use a 2.5- to 3-cm incision. Regardless of incision length, each OCTR should proceed through the same reproducible steps.

We perform OCTR under tourniquet control. Choice of anesthesia is surgeon and patient preference. We prefer local anesthesia with conscious sedation. After conscious sedation is administered, we infiltrate the carpal tunnel and surrounding subcutaneous tissue with 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

A 2.5- to 3-cm longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the radial border of the ring finger from the Kaplan cardinal line26 and extending about 3 cm proximally toward the wrist flexion crease ulnar to the palmaris longus if present (Figure 1).

After the skin is incised longitudinally, the subcutaneous fat is mobilized and cutaneous sensory branches identified and protected. The underlying superficial palmar fascia is incised in line with the skin incision. The underlying midportion of the TCL is now visualized.

Transverse Carpal Ligament Release

Occasionally, the investing fascia along the ulnar edge of the thenar musculature is mobilized radialward (if the thenar musculature is well developed) to visualize the proximal limb of the TCL. Injury to any anomalous motor branch of the median nerve is avoided by directly visualizing and then incising the TCL (Figure 2). The TCL is incised along its ulnar border just radial to the hook of hamate from distal to proximal in line with the radial border of the ring finger. Staying near the ulnar attachment of the TCL keeps the plane of ligament division farther away from the median nerve and its recurrent motor branches. Although the ulnar neurovascular bundle typically resides ulnar to the hook of hamate in the canal of Guyon, the surgeon must be aware that it can be located radial to the hook in some instances.27,28 In the elderly, the ulnar artery may be tortuous and enter the field and require retraction. The TCL is incised distally until the sentinel fat pad, which marks the superficial palmar arterial arch, is visualized. This bed of adipose tissue marks the distal edge of the TCL.29

Proximally, subcutaneous tissues above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF are mobilized to about 2 cm proximal to the wrist flexion crease to create a plane for the fine long nasal turbinate speculum. The nasal turbinate speculum is then inserted into this plane above the proximal limb of the TCL and DVFF (Figure 3). Once inserted to the level of the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF, the speculum is opened.

Topside visualization is now encountered with the ulnar neurovascular bundle protected by the ulnar blade of the speculum. A long-handle scalpel is used to incise the TCL and the DVFF under direct visualization from proximal to distal in line with the previously completed distal release (Figure 4). As the nasal turbinate speculum is stretching the TCL and putting it under tension, the TCL can be heard splitting as it is being incised. Once the TCL and the DVFF are divided, the speculum is slowly closed and removed. Wide diastasis of the radial and ulnar leaflets of the TCL and the DVFF is directly visualized. Complete decompression of the median nerve from the distal forearm fascia to the superficial palmar arch is confirmed.

Adhesions between the undersurface of the radial leaflet and the flexor tendons and median nerve are mobilized. The median nerve is assessed for “hourglass” morphology or atrophy. The flexor tendons can be swept radialward with a free elevator to inspect the floor of the carpal tunnel. Flexor tenosynovectomy is not routinely performed. The incision is closed with interrupted simple sutures using 4-0 nylon.

Study Results

This study was conducted at Hand Surgery PC, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Tufts University School of Medicine. Over a 10-month interval, 101 consecutive mini-OCTRs (63 right hands, 38 left hands) were performed with this proximal release modification in 88 patients (51 females, 37 males) by Dr. Ruchelsman and Dr. Belsky (Table). CTRs performed in the setting of wrist and/or carpal trauma were excluded. Mean age was 62.8 years. Mean follow-up was 11.3 weeks (~3 months). For isolated cases of CTR, mean tourniquet time was 16 minutes. CTS symptoms were relieved in all patients with a high degree of satisfaction as measured with history and examination findings at follow-up visits. There were no major complications (eg, infection, neural or vascular damage, severe residual pain). Four patients reported minor residual numbness in the fingers at latest follow-up but nevertheless had major improvement over preoperative baseline. These 4 patients had preoperative electromyograms or nerve conduction studies documenting the extent of their disease. There was 1 case of minor wound complication. Three weeks after surgery, the patient had a 1-cm wound opening, which closed with local wound care. The patient did not develop any drainage, infection, bleeding, or neurologic symptoms.

Discussion

Open release of the TCL—the gold standard of surgical treatment for CTS—produces reliable symptom relief in the vast majority of patients.25,30 Given that the most common complication of carpal tunnel surgery is incomplete release of the TCL,31,32 this technique, which uses a nasal turbinate speculum to better visualize the median nerve, could potentially reduce the reoperation rate. The nasal turbinate speculum allows the surgeon to see the confluence of the TCL and the DVFF. In addition, as the complete release can be visualized, there is minimal chance of injury.

The 2007 Cochrane review3 found no strong evidence supporting replacing OCTR with endoscopic techniques. Previous investigators have questioned the utility of ECTR given that it is higher in cost and more resource-intensive than OCTR1,33,34 and is associated with higher rates of certain complications.5,22,35-37 A 2004 meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials found a higher rate of reversible nerve damage with an odds ratio of 3.1 for ECTR versus OCTR.35 A more recent (2006) review of more than 80 studies found transient neurapraxias in 1.45% of ECTR cases and 0.25% of OCTR cases.5 The same study reported overall complication rates (reversible and major neurovascular structural injuries) of 0.74% for OCTR and 1.63% for ECTR (P < .005). Another limitation of ECTR is that endoscopic techniques require a higher degree of surgical skill, which makes teaching residents and fellows more challenging.

The novel nasal turbinate speculum technique presented here is easily reproducible and allows first-time surgeons to visualize all important structures. Given that this technique does not require an endoscope or an endoscope-viewing tower, it is likely more cost-effective and requires less time for turnover between cases. Patients obtain good relief of their CTS symptoms with this technique, and most return to their daily activities within weeks after operation.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a disorder characterized by entrapment of the median nerve at the wrist, which may lead to symptoms of pain, paresthesia, and, ultimately, thenar muscle atrophy. Surgical intervention is indicated with persistent or progressive symptoms despite nonoperative management. Timely surgical decompression aims to halt progression of this disorder and prevent permanent peripheral nerve injury.

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery in the United States, with about 400,000 operations performed annually.1,2 Several methods of decompressing the carpal tunnel have been described.3 These include standard open CTR (OCTR), mini-open approaches, and various endoscopic techniques. OCTR was initially described by Sir James Learmonth in 1933,4 and it remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic CTS. Uniform excellent results with high patient satisfaction and low complication rates have been reported in several series.5-9 Common to all techniques is complete proximal-to-distal division of the transverse carpal ligament (TCL). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that TCL transection and the resulting diastasis between the radial and ulnar leaflets cause a significant increase in the volume of the carpal tunnel, leading to decreased pressure.10,11