User login

Case

A 64-year-old man presented to the ED seeking assistance in withdrawing from his prescription of oxycodone, which he had been taking to manage chronic pain due to rheumatoid arthritis. He stated that he had discontinued the oxycodone approximately 4 days prior to presentation and over the past 3 days, had been experiencing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and diaphoresis. He noted that his symptoms were identical to those he had during previous unsuccessful attempts to wean himself from the narcotic medication. He denied any fever, dysuria, penile discharge, or any skin changes. Further evaluation revealed a remote history of a cholecystectomy and an appendectomy.

During the initial examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. His vital signs were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; blood pressure, 107/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate, 22 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The abdominal examination revealed moderate diffuse tenderness, mild distension without guarding or rebound, and some well-healed surgical scars.

In light of the abnormal sonographic findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of a distal small bowel obstruction (SBO). Surgery services were consulted. As the patient’s current symptoms were believed to be the result of an SBO and not from narcotic withdrawal, surgery services instructed nothing by mouth and elected nonsurgical management. They placed a nasogastric tube and administered fluids and analgesics via IV. The patient was discharged 4 days after presentation to the ED, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Annually in the United States, less than 1% of all patients presenting to EDs are subsequently diagnosed with SBO.1 However, this disease comprises 15% of all surgical hospital admissions, costing upward of $1 billion in annual hospital charges.2 Moreover, patients with SBO suffer from a disproportionately high morbidity (eg, bowel strangulation, necrosis) and mortality than the general population,3-5 and delayed diagnosis is associated with a higher risk of bowel resection. One study by Bickell et al6 showed that only 4% of patients appropriately managed less than 24 hours after symptom onset required resection compared with 10% to 14% of patients managed more than 24 hours after symptom onset.

As most patients diagnosed with SBO are first seen in the ED, emergency physicians (EPs) have a distinctive role in lowering the likelihood of a poor outcome by making this diagnosis early.7 Multiple methods of diagnosing SBO are at the disposal of the clinician, including the history and physical examination, abdominal X-ray, ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The history and physical examination can be rapidly performed at the bedside in patients with suspected SBO. The factors typically associated with SBO include constipation, a previous history of abdominal surgeries, abnormal bowel sounds, and abdominal distension.3 However, these findings are not sufficient to accurately and adequately rule in or rule out disease.3,8,9

Diagnostic Imaging

While patient history and physical examination may be helpful in diagnosing SBO, imaging plays a critical role in the definitive diagnosis. The imaging modality that is the de facto gold standard for diagnosis is the CT scan.10 A meta-analysis by Taylor et al,3 which included 64-slice multidetector CT imaging studies (using both oral and IV contrast), demonstrated sensitivities of 93% to 96% and specificities of 93% to 100% in diagnosing SBO.

In patients in whom CT is contraindicated, MRI can be a useful alternative, with studies showing a similar diagnostic accuracy to 64-slice CT.13,14 Both CT and MRI are highly accurate in diagnosing SBO; however, there are disadvantages to their use. Such disadvantages include the inability to perform these studies at bedside; the length of time to perform these studies; the higher cost compared to other modalities; and, in CT, the adverse side effects of radiation and possible contrast reactions.

Bedside Ultrasound

Abdominal X-ray traditionally has been the initial choice in bedside imaging for SBO; however, a recent meta-analysis found this modality to have a summary sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 66%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.6, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.43 in diagnosing SBO.3 Based on these statistics, bedside ultrasound has recently ascended as a viable alternative to abdominal X-ray.

Although there is limited research regarding the accuracy of ultrasound to evaluate SBO, initial study results are encouraging. The previously cited meta-analysis by Taylor et al3 identified six ultrasound studies, two of which were performed in the ED. In one of these two studies, Unlüer et al10 performed a prospective study that enrolled 174 patients in the ED, 90 of whom were subsequently found to have an SBO. In addition, Unlüer et al’s study found that relatively inexperienced emergency medicine (EM) residents were able to use bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of SBO with a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 92.7%.

Another ED study by Jang et al15 enrolled 76 patients, 33 of whom were diagnosed with SBO using CT. In this study, the authors found ultrasound to have a 91% sensitivity and 84% specificity for dilated bowel, and a specificity of 98% and sensitivity of 27% for decreased peristalsis.15 Imaging in this study was performed by EM residents, who received only 10 minutes of didactic lecture.

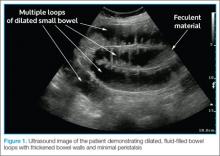

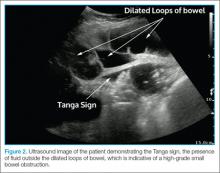

The criteria used in the abovementioned studies varied slightly. The study by Jang et al15 used either fluid-filled dilated bowel >2.5 cm or decreased/absent forward bowel peristalsis, while the study by Unlüer et al10 defined sonographic SBO as two of the three following criteria: greater than 3 dilated loops of either jejunum (>25 mm), or of ileum (>15 mm), increased peristalsis or a collapsed colonic lumen. In cases of higher-grade obstruction, the Tanga sign, fluid seen outside of the dilated loops of bowel, has also been reported (Figure 2).16

Conclusion

There are several distinct advantages to using bedside ultrasound in cases of suspected SBO, including its lack of ionizing radiation, the ability to perform the scan rapidly, and the high accuracy rate in detecting this condition—even in the hands of providers with minimal training. In addition to its cost-effectiveness, ultrasound may be preferred in patients with relative contraindications to CT, such as pregnant patients and patients with contrast allergies. Even in patients in whom there is no contraindication to CT, ultrasound may be used to safely and quickly identify and risk-stratify those who require further imaging versus those who can be safely discharged home—or possibly even finding alternative diagnoses of acute abdominal pain (eg, acute cholecystitis, ureterolithiasis, abdominal aortic aneurysm).

Dr Avila is an attending physician and ultrasound fellow in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr Smith is the director of emergency ultrasound in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga. Dr Whittle is the director of research in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35 year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med. 201;29(7):711-716.

- Rocha FG, Theman TA, Matros E, Ledbetter SM, Zinner MJ, Ferzoco SJ. Nonoperative management of patients with a diagnosis of high-grade small bowel obstruction by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2009;144(11):1000-1004.

- Taylor M, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L, Soreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Complications and death after surgical treatment of small bowel obstruction: a 35-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2000;231(4):529-537.

- Cheadle WG, Garr EE, Richardson JD. The importance of early diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 1988;54(9):565-569.

- Bickell NA, Federman AD, Aufses AH Jr. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(2):170-176.

- Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and computer assistance to diagnosis of acute small-bowel obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(8):715-721.

- Böhner H, Yang Q, Franke C, Verreet PR, Ohmann C. Simple data from history and physical examination help to exclude bowel obstruction and to avoid radiographic studies in patients with acute abdominal pain. Eur J Surg. 1998;164(10):777-784.

- Unlüer EE, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca FK. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

- Pongpornsup S, Tarachat K, Srisajjakul S. Accuracy of 64-slice multi-detector computed tomography in diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(12):1651-1661.

- Shakil O, Zafar SN, Zia-ur-Rehman, Saleem S, Khan R, Pal KM. The role of computed tomography for identifying mechanical bowel obstruction in a Pakistani population. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(9):871-874.

- Beall DP, Fortman BJ, Lawler BC, Regan F. Imaging bowel obstruction: a comparison between fast magnetic resonance imaging and helical computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(8):719-724.

- Regan F, Beall DP, Bohlman ME, Khazan R, Sufi A, Schaefer DC. Fast MR imaging and the detection of small-bowel obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1465-1469.

- Jang TB, Schindler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(8):676-678.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

Case

A 64-year-old man presented to the ED seeking assistance in withdrawing from his prescription of oxycodone, which he had been taking to manage chronic pain due to rheumatoid arthritis. He stated that he had discontinued the oxycodone approximately 4 days prior to presentation and over the past 3 days, had been experiencing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and diaphoresis. He noted that his symptoms were identical to those he had during previous unsuccessful attempts to wean himself from the narcotic medication. He denied any fever, dysuria, penile discharge, or any skin changes. Further evaluation revealed a remote history of a cholecystectomy and an appendectomy.

During the initial examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. His vital signs were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; blood pressure, 107/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate, 22 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The abdominal examination revealed moderate diffuse tenderness, mild distension without guarding or rebound, and some well-healed surgical scars.

In light of the abnormal sonographic findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of a distal small bowel obstruction (SBO). Surgery services were consulted. As the patient’s current symptoms were believed to be the result of an SBO and not from narcotic withdrawal, surgery services instructed nothing by mouth and elected nonsurgical management. They placed a nasogastric tube and administered fluids and analgesics via IV. The patient was discharged 4 days after presentation to the ED, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Annually in the United States, less than 1% of all patients presenting to EDs are subsequently diagnosed with SBO.1 However, this disease comprises 15% of all surgical hospital admissions, costing upward of $1 billion in annual hospital charges.2 Moreover, patients with SBO suffer from a disproportionately high morbidity (eg, bowel strangulation, necrosis) and mortality than the general population,3-5 and delayed diagnosis is associated with a higher risk of bowel resection. One study by Bickell et al6 showed that only 4% of patients appropriately managed less than 24 hours after symptom onset required resection compared with 10% to 14% of patients managed more than 24 hours after symptom onset.

As most patients diagnosed with SBO are first seen in the ED, emergency physicians (EPs) have a distinctive role in lowering the likelihood of a poor outcome by making this diagnosis early.7 Multiple methods of diagnosing SBO are at the disposal of the clinician, including the history and physical examination, abdominal X-ray, ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The history and physical examination can be rapidly performed at the bedside in patients with suspected SBO. The factors typically associated with SBO include constipation, a previous history of abdominal surgeries, abnormal bowel sounds, and abdominal distension.3 However, these findings are not sufficient to accurately and adequately rule in or rule out disease.3,8,9

Diagnostic Imaging

While patient history and physical examination may be helpful in diagnosing SBO, imaging plays a critical role in the definitive diagnosis. The imaging modality that is the de facto gold standard for diagnosis is the CT scan.10 A meta-analysis by Taylor et al,3 which included 64-slice multidetector CT imaging studies (using both oral and IV contrast), demonstrated sensitivities of 93% to 96% and specificities of 93% to 100% in diagnosing SBO.

In patients in whom CT is contraindicated, MRI can be a useful alternative, with studies showing a similar diagnostic accuracy to 64-slice CT.13,14 Both CT and MRI are highly accurate in diagnosing SBO; however, there are disadvantages to their use. Such disadvantages include the inability to perform these studies at bedside; the length of time to perform these studies; the higher cost compared to other modalities; and, in CT, the adverse side effects of radiation and possible contrast reactions.

Bedside Ultrasound

Abdominal X-ray traditionally has been the initial choice in bedside imaging for SBO; however, a recent meta-analysis found this modality to have a summary sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 66%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.6, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.43 in diagnosing SBO.3 Based on these statistics, bedside ultrasound has recently ascended as a viable alternative to abdominal X-ray.

Although there is limited research regarding the accuracy of ultrasound to evaluate SBO, initial study results are encouraging. The previously cited meta-analysis by Taylor et al3 identified six ultrasound studies, two of which were performed in the ED. In one of these two studies, Unlüer et al10 performed a prospective study that enrolled 174 patients in the ED, 90 of whom were subsequently found to have an SBO. In addition, Unlüer et al’s study found that relatively inexperienced emergency medicine (EM) residents were able to use bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of SBO with a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 92.7%.

Another ED study by Jang et al15 enrolled 76 patients, 33 of whom were diagnosed with SBO using CT. In this study, the authors found ultrasound to have a 91% sensitivity and 84% specificity for dilated bowel, and a specificity of 98% and sensitivity of 27% for decreased peristalsis.15 Imaging in this study was performed by EM residents, who received only 10 minutes of didactic lecture.

The criteria used in the abovementioned studies varied slightly. The study by Jang et al15 used either fluid-filled dilated bowel >2.5 cm or decreased/absent forward bowel peristalsis, while the study by Unlüer et al10 defined sonographic SBO as two of the three following criteria: greater than 3 dilated loops of either jejunum (>25 mm), or of ileum (>15 mm), increased peristalsis or a collapsed colonic lumen. In cases of higher-grade obstruction, the Tanga sign, fluid seen outside of the dilated loops of bowel, has also been reported (Figure 2).16

Conclusion

There are several distinct advantages to using bedside ultrasound in cases of suspected SBO, including its lack of ionizing radiation, the ability to perform the scan rapidly, and the high accuracy rate in detecting this condition—even in the hands of providers with minimal training. In addition to its cost-effectiveness, ultrasound may be preferred in patients with relative contraindications to CT, such as pregnant patients and patients with contrast allergies. Even in patients in whom there is no contraindication to CT, ultrasound may be used to safely and quickly identify and risk-stratify those who require further imaging versus those who can be safely discharged home—or possibly even finding alternative diagnoses of acute abdominal pain (eg, acute cholecystitis, ureterolithiasis, abdominal aortic aneurysm).

Dr Avila is an attending physician and ultrasound fellow in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr Smith is the director of emergency ultrasound in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga. Dr Whittle is the director of research in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga.

Case

A 64-year-old man presented to the ED seeking assistance in withdrawing from his prescription of oxycodone, which he had been taking to manage chronic pain due to rheumatoid arthritis. He stated that he had discontinued the oxycodone approximately 4 days prior to presentation and over the past 3 days, had been experiencing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and diaphoresis. He noted that his symptoms were identical to those he had during previous unsuccessful attempts to wean himself from the narcotic medication. He denied any fever, dysuria, penile discharge, or any skin changes. Further evaluation revealed a remote history of a cholecystectomy and an appendectomy.

During the initial examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. His vital signs were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; blood pressure, 107/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate, 22 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. The abdominal examination revealed moderate diffuse tenderness, mild distension without guarding or rebound, and some well-healed surgical scars.

In light of the abnormal sonographic findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of a distal small bowel obstruction (SBO). Surgery services were consulted. As the patient’s current symptoms were believed to be the result of an SBO and not from narcotic withdrawal, surgery services instructed nothing by mouth and elected nonsurgical management. They placed a nasogastric tube and administered fluids and analgesics via IV. The patient was discharged 4 days after presentation to the ED, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Discussion

Annually in the United States, less than 1% of all patients presenting to EDs are subsequently diagnosed with SBO.1 However, this disease comprises 15% of all surgical hospital admissions, costing upward of $1 billion in annual hospital charges.2 Moreover, patients with SBO suffer from a disproportionately high morbidity (eg, bowel strangulation, necrosis) and mortality than the general population,3-5 and delayed diagnosis is associated with a higher risk of bowel resection. One study by Bickell et al6 showed that only 4% of patients appropriately managed less than 24 hours after symptom onset required resection compared with 10% to 14% of patients managed more than 24 hours after symptom onset.

As most patients diagnosed with SBO are first seen in the ED, emergency physicians (EPs) have a distinctive role in lowering the likelihood of a poor outcome by making this diagnosis early.7 Multiple methods of diagnosing SBO are at the disposal of the clinician, including the history and physical examination, abdominal X-ray, ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The history and physical examination can be rapidly performed at the bedside in patients with suspected SBO. The factors typically associated with SBO include constipation, a previous history of abdominal surgeries, abnormal bowel sounds, and abdominal distension.3 However, these findings are not sufficient to accurately and adequately rule in or rule out disease.3,8,9

Diagnostic Imaging

While patient history and physical examination may be helpful in diagnosing SBO, imaging plays a critical role in the definitive diagnosis. The imaging modality that is the de facto gold standard for diagnosis is the CT scan.10 A meta-analysis by Taylor et al,3 which included 64-slice multidetector CT imaging studies (using both oral and IV contrast), demonstrated sensitivities of 93% to 96% and specificities of 93% to 100% in diagnosing SBO.

In patients in whom CT is contraindicated, MRI can be a useful alternative, with studies showing a similar diagnostic accuracy to 64-slice CT.13,14 Both CT and MRI are highly accurate in diagnosing SBO; however, there are disadvantages to their use. Such disadvantages include the inability to perform these studies at bedside; the length of time to perform these studies; the higher cost compared to other modalities; and, in CT, the adverse side effects of radiation and possible contrast reactions.

Bedside Ultrasound

Abdominal X-ray traditionally has been the initial choice in bedside imaging for SBO; however, a recent meta-analysis found this modality to have a summary sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 66%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.6, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.43 in diagnosing SBO.3 Based on these statistics, bedside ultrasound has recently ascended as a viable alternative to abdominal X-ray.

Although there is limited research regarding the accuracy of ultrasound to evaluate SBO, initial study results are encouraging. The previously cited meta-analysis by Taylor et al3 identified six ultrasound studies, two of which were performed in the ED. In one of these two studies, Unlüer et al10 performed a prospective study that enrolled 174 patients in the ED, 90 of whom were subsequently found to have an SBO. In addition, Unlüer et al’s study found that relatively inexperienced emergency medicine (EM) residents were able to use bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of SBO with a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 92.7%.

Another ED study by Jang et al15 enrolled 76 patients, 33 of whom were diagnosed with SBO using CT. In this study, the authors found ultrasound to have a 91% sensitivity and 84% specificity for dilated bowel, and a specificity of 98% and sensitivity of 27% for decreased peristalsis.15 Imaging in this study was performed by EM residents, who received only 10 minutes of didactic lecture.

The criteria used in the abovementioned studies varied slightly. The study by Jang et al15 used either fluid-filled dilated bowel >2.5 cm or decreased/absent forward bowel peristalsis, while the study by Unlüer et al10 defined sonographic SBO as two of the three following criteria: greater than 3 dilated loops of either jejunum (>25 mm), or of ileum (>15 mm), increased peristalsis or a collapsed colonic lumen. In cases of higher-grade obstruction, the Tanga sign, fluid seen outside of the dilated loops of bowel, has also been reported (Figure 2).16

Conclusion

There are several distinct advantages to using bedside ultrasound in cases of suspected SBO, including its lack of ionizing radiation, the ability to perform the scan rapidly, and the high accuracy rate in detecting this condition—even in the hands of providers with minimal training. In addition to its cost-effectiveness, ultrasound may be preferred in patients with relative contraindications to CT, such as pregnant patients and patients with contrast allergies. Even in patients in whom there is no contraindication to CT, ultrasound may be used to safely and quickly identify and risk-stratify those who require further imaging versus those who can be safely discharged home—or possibly even finding alternative diagnoses of acute abdominal pain (eg, acute cholecystitis, ureterolithiasis, abdominal aortic aneurysm).

Dr Avila is an attending physician and ultrasound fellow in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr Smith is the director of emergency ultrasound in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga. Dr Whittle is the director of research in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35 year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med. 201;29(7):711-716.

- Rocha FG, Theman TA, Matros E, Ledbetter SM, Zinner MJ, Ferzoco SJ. Nonoperative management of patients with a diagnosis of high-grade small bowel obstruction by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2009;144(11):1000-1004.

- Taylor M, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L, Soreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Complications and death after surgical treatment of small bowel obstruction: a 35-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2000;231(4):529-537.

- Cheadle WG, Garr EE, Richardson JD. The importance of early diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 1988;54(9):565-569.

- Bickell NA, Federman AD, Aufses AH Jr. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(2):170-176.

- Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and computer assistance to diagnosis of acute small-bowel obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(8):715-721.

- Böhner H, Yang Q, Franke C, Verreet PR, Ohmann C. Simple data from history and physical examination help to exclude bowel obstruction and to avoid radiographic studies in patients with acute abdominal pain. Eur J Surg. 1998;164(10):777-784.

- Unlüer EE, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca FK. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

- Pongpornsup S, Tarachat K, Srisajjakul S. Accuracy of 64-slice multi-detector computed tomography in diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(12):1651-1661.

- Shakil O, Zafar SN, Zia-ur-Rehman, Saleem S, Khan R, Pal KM. The role of computed tomography for identifying mechanical bowel obstruction in a Pakistani population. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(9):871-874.

- Beall DP, Fortman BJ, Lawler BC, Regan F. Imaging bowel obstruction: a comparison between fast magnetic resonance imaging and helical computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(8):719-724.

- Regan F, Beall DP, Bohlman ME, Khazan R, Sufi A, Schaefer DC. Fast MR imaging and the detection of small-bowel obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1465-1469.

- Jang TB, Schindler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(8):676-678.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

- Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35 year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med. 201;29(7):711-716.

- Rocha FG, Theman TA, Matros E, Ledbetter SM, Zinner MJ, Ferzoco SJ. Nonoperative management of patients with a diagnosis of high-grade small bowel obstruction by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 2009;144(11):1000-1004.

- Taylor M, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-544.

- Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L, Soreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Complications and death after surgical treatment of small bowel obstruction: a 35-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2000;231(4):529-537.

- Cheadle WG, Garr EE, Richardson JD. The importance of early diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 1988;54(9):565-569.

- Bickell NA, Federman AD, Aufses AH Jr. Influence of time on risk of bowel resection in complete small bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):847-854.

- Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(2):170-176.

- Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and computer assistance to diagnosis of acute small-bowel obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(8):715-721.

- Böhner H, Yang Q, Franke C, Verreet PR, Ohmann C. Simple data from history and physical examination help to exclude bowel obstruction and to avoid radiographic studies in patients with acute abdominal pain. Eur J Surg. 1998;164(10):777-784.

- Unlüer EE, Yavaşi O, Eroğlu O, Yilmaz C, Akarca FK. Ultrasonography by emergency medicine and radiology residents for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):260-264.

- Pongpornsup S, Tarachat K, Srisajjakul S. Accuracy of 64-slice multi-detector computed tomography in diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(12):1651-1661.

- Shakil O, Zafar SN, Zia-ur-Rehman, Saleem S, Khan R, Pal KM. The role of computed tomography for identifying mechanical bowel obstruction in a Pakistani population. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(9):871-874.

- Beall DP, Fortman BJ, Lawler BC, Regan F. Imaging bowel obstruction: a comparison between fast magnetic resonance imaging and helical computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(8):719-724.

- Regan F, Beall DP, Bohlman ME, Khazan R, Sufi A, Schaefer DC. Fast MR imaging and the detection of small-bowel obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1465-1469.

- Jang TB, Schindler D, Kaji AH. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(8):676-678.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.