User login

The Intersection of Clinical Quality Improvement Research and Implementation Science

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

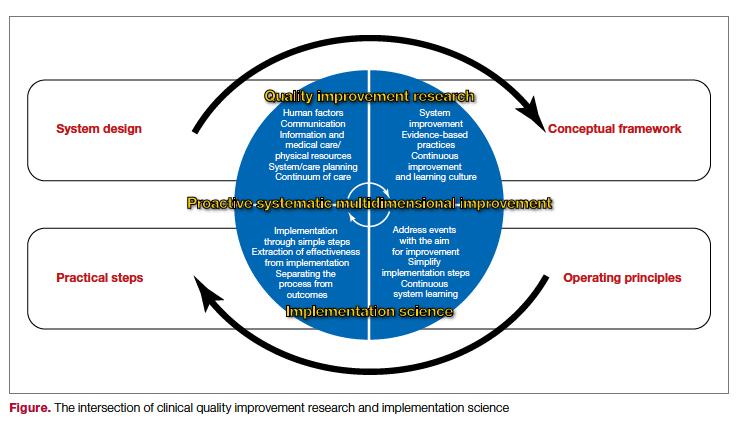

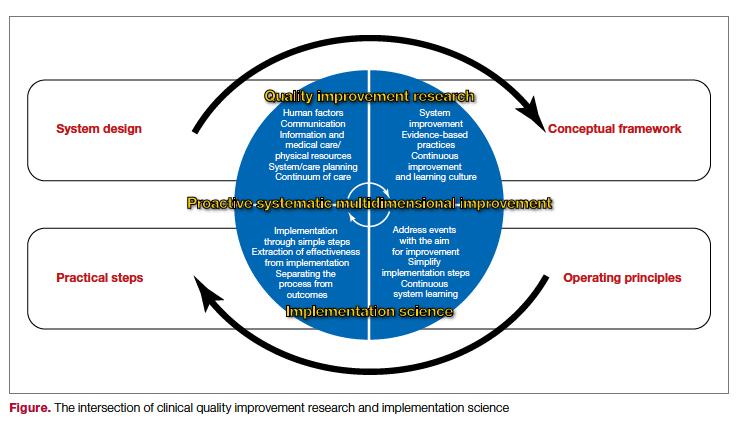

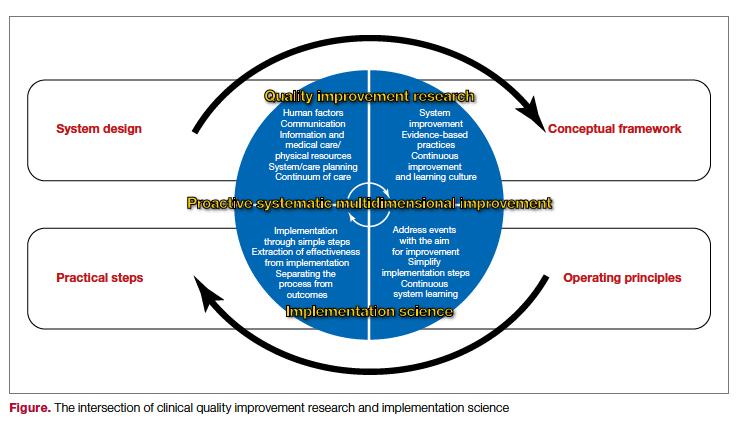

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

The Institute of Medicine brought much-needed attention to the need for process improvement in medicine with its seminal report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which was issued in 1999, leading to the quality movement’s call to close health care performance gaps in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.1,2 Quality improvement science in medicine has evolved over the past 2 decades to include a broad spectrum of approaches, from agile improvement to continuous learning and improvement. Current efforts focus on Lean-based process improvement along with a reduction in variation in clinical practice to align practice with the principles of evidence-based medicine in a patient-centered approach.3 Further, the definition of quality improvement under the Affordable Care Act was framed as an equitable, timely, value-based, patient-centered approach to achieving population-level health goals.4 Thus, the science of quality improvement drives the core principles of care delivery improvement, and the rigorous evidence needed to expand innovation is embedded within the same framework.5,6 In clinical practice, quality improvement projects aim to define gaps and then specific steps are undertaken to improve the evidence-based practice of a specific process. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of the practice by reducing waste within a particular domain. Thus, quality improvement and implementation research eventually unify how clinical practice is advanced concurrently to bridge identified gaps.7

System redesign through a patient-centered framework forms the core of an overarching strategy to support system-level processes. Both require a deep understanding of the fields of quality improvement science and implementation science.8 Furthermore, aligning clinical research needs, system aims, patients’ values, and clinical care give the new design a clear path forward. Patient-centered improvement includes the essential elements of system redesign around human factors, including communication, physical resources, and updated information during episodes of care. The patient-centered improvement design is juxtaposed with care planning and establishing continuum of care processes.9 It is essential to note that safety is rooted within the quality domain as a top priority in medicine.10 The best implementation methods and approaches are discussed and debated, and the improvement progress continues on multiple fronts.11 Patient safety systems are implemented simultaneously during the redesign phase. Moreover, identifying and testing the health care delivery methods in the era of competing strategic priorities to achieve the desirable clinical outcomes highlights the importance of implementation, while contemplating the methods of dissemination, scalability, and sustainability of the best evidence-based clinical practice.

The cycle of quality improvement research completes the system implementation efforts. The conceptual framework of quality improvement includes multiple areas of care and transition, along with applying the best clinical practices in a culture that emphasizes continuous improvement and learning. At the same time, the operating principles should include continuous improvement in a simple and continuous system of learning as a core concept. Our proposed implementation approach involves taking simple and practical steps while separating the process from the outcomes measures, extracting effectiveness throughout the process. It is essential to keep in mind that building a proactive and systematic improvement environment requires a framework for safety, reliability, and effective care, as well as the alignment of the physical system, communication, and professional environment and culture (Figure).

In summary, system design for quality improvement research should incorporate the principles and conceptual framework that embody effective implementation strategies, with a focus on operational and practical steps. Continuous improvement will be reached through the multidimensional development of current health care system metrics and the incorporation of implementation science methods.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

3. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1182-1184. doi:10.1001/jama.299.10.1182

4. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6):944-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491

5. Fan E, Needham DM. The science of quality improvement. JAMA. 2008;300(4):390-391. doi:10.1001/jama.300.4.390-b

6. Alexander JA, Hearld LR. The science of quality improvement implementation: developing capacity to make a difference. Med Care. 2011:S6-20. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e1709c

7. Rohweder C, Wangen M, Black M, et al. Understanding quality improvement collaboratives through an implementation science lens. Prev Med. 2019;129:105859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105859

8. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848-2851. doi:10.1001/jama.296.23.2848

9. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i85-90. doi:10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i85

10. Leape LL, Berwick DM, Bates DW. What practices will most improve safety? Evidence-based medicine meets patient safety. JAMA. 2002;288(4):501-507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.501

11. Auerbach AD, Landefeld CS, Shojania KG. The tension between needing to improve care and knowing how to do it. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):608-613. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb070738

Fall Injury Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Effect of a Multifactorial Intervention and a Home Hazard Removal Program

Study 1 Overview (Bhasin et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a multifactorial intervention for fall prevention on fall injury in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This was a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial conducted in 86 primary care practices across 10 health care systems.

Setting and participants: The primary care sites were selected based on the prespecified criteria of size, ability to implement the intervention, proximity to other practices, accessibility to electronic health records, and access to community-based exercise programs. The primary care practices were randomly assigned to intervention or control.

Eligibility criteria for participants at those practices included age 70 years or older, dwelling in the community, and having an increased risk of falls, as determined by a history of fall-related injury in the past year, 2 or more falls in the past year, or being afraid of falling because of problems with balance or walking. Exclusion criteria were inability to provide consent or lack of proxy consent for participants who were determined to have cognitive impairment based on screening, and inability to speak English or Spanish. A total of 2802 participants were enrolled in the intervention group, and 2649 participants were enrolled in the control group.

Intervention: The intervention contained 5 components: a standardized assessment of 7 modifiable risk factors for fall injuries; standardized protocol-driven recommendations for management of risk factors; an individualized care plan focused on 1 to 3 risk factors; implementation of care plans, including referrals to community-based programs; and follow-up care conducted by telephone or in person. The modifiable risk factors included impairment of strength, gait, or balance; use of medications related to falls; postural hypotension; problems with feet or footwear; visual impairment; osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency; and home safety hazards. The intervention was delivered by nurses who had completed online training modules and face-to-face training sessions focused on the intervention and motivational interviewing along with continuing education, in partnership with participants and their primary care providers. In the control group, participants received enhanced usual care, including an informational pamphlet, and were encouraged to discuss fall prevention with their primary care provider, including the results of their screening evaluation.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the first serious fall injury in a time-to-event analysis, defined as a fall resulting in a fracture (other than thoracic or lumbar vertebral fracture), joint dislocation, cut requiring closure, head injury requiring hospitalization, sprain or strain, bruising or swelling, or other serious injury. The secondary outcome was first patient-reported fall injury, also in a time-to-event analysis, ascertained by telephone interviews conducted every 4 months. Other outcomes included hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and other health care utilization. Adjudication of fall events and injuries was conducted by a team blinded to treatment assignment and verified using administrative claims data, encounter data, or electronic health record review.

Main results: The intervention and control groups were similar in terms of sex and age: 62.5% vs 61.5% of participants were women, and mean (SD) age was 79.9 (5.7) years and 79.5 (5.8) years, respectively. Other demographic characteristics were similar between groups. For the primary outcome, the rate of first serious injury was 4.9 per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 5.3 per 100 person-years in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.80-1.06; P = .25). For the secondary outcome of patient-reported fall injury, there were 25.6 events per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 28.6 in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P =0.004). Rates of hospitalization and other secondary outcomes were similar between groups.

Conclusion: The multifactorial STRIDE intervention did not reduce the rate of serious fall injury when compared to enhanced usual care. The intervention did result in lower rates of fall injury by patient report, but no other significant outcomes were seen.

Study 2 Overview (Stark et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a behavioral home hazard removal intervention for fall prevention on risk of fall in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This randomized clinical trial was conducted at a single site in St. Louis, Missouri. Participants were community-dwelling older adults who received services from the Area Agency on Aging (AAA). Inclusion criteria included age 65 years and older, having 1 or more falls in the previous 12 months or being worried about falling by self report, and currently receiving services from an AAA. Exclusion criteria included living in an institution or being severely cognitively impaired and unable to follow directions or report falls. Participants who met the criteria were contacted by phone and invited to participate. A total of 310 participants were enrolled in the study, with an equal number of participants assigned to the intervention and control groups.

Intervention: The intervention included hazard identification and removal after a comprehensive assessment of participants, their behaviors, and the environment; this assessment took place during the first visit, which lasted approximately 80 minutes. A home hazard removal plan was developed, and in the second session, which lasted approximately 40 minutes, remediation of hazards was carried out. A third session for home modification that lasted approximately 30 minutes was conducted, if needed. At 6 months after the intervention, a booster session to identify and remediate any new home hazards and address issues was conducted. Specific interventions, as identified by the assessment, included minor home repair such as grab bars, adaptive equipment, task modification, and education. Shared decision making that enabled older adults to control changes in their homes, self-management strategies to improve awareness, and motivational enhancement strategies to improve acceptance were employed. Scripted algorithms and checklists were used to deliver the intervention. For usual care, an annual assessment and referrals to community services, if needed, were conducted in the AAA.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the number of days to first fall in 12 months. Falls were defined as unintentional movements to the floor, ground, or object below knee level, and falls were recorded through a daily journal for 12 months. Participants were contacted by phone if they did not return the journal or reported a fall. Participants were interviewed to verify falls and determine whether a fall was injurious. Secondary outcomes included rate of falls per person per 12 months; daily activity performance measured using the Older Americans Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living scale; falls self-efficacy, which measures confidence performing daily activities without falling; and quality of life using the SF-36 at 12 months.

Main results: Most of the study participants were women (74%), and mean (SD) age was 75 (7.4) years. Study retention was similar between the intervention and control groups, with 82% completing the study in the intervention group compared with 81% in the control group. Fidelity to the intervention, as measured by a checklist by the interventionist, was 99%, and adherence to home modification, as measured by number of home modifications in use by self report, was high at 92% at 6 months and 91% at 12 months. For the primary outcome, fall hazard was not different between the intervention and control groups (hazard ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.66-1.27). For the secondary outcomes, the rate of falling was lower in the intervention group compared with the control group, with a relative risk of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.40-0.95). There was no difference in other secondary outcomes of daily activity performance, falls self-efficacy, or quality of life.

Conclusion: Despite high adherence to home modifications and fidelity to the intervention, this home hazard removal program did not reduce the risk of falling when compared to usual care. It did reduce the rate of falls, although no other effects were observed.

Commentary

Observational studies have identified factors that contribute to falls,1 and over the past 30 years a number of intervention trials designed to reduce the risk of falling have been conducted. A recent Cochrane review, published prior to the Bhasin et al and Stark et al trials, looked at the effect of multifactorial interventions for fall prevention across 62 trials that included 19,935 older adults living in the community. The review concluded that multifactorial interventions may reduce the rate of falls, but this conclusion was based on low-quality evidence and there was significant heterogeneity across the studies.2

The STRIDE randomized trial represents the latest effort to address the evidence gap around fall prevention, with the STRIDE investigators hoping this would be the definitive trial that leads to practice change in fall prevention. Smaller trials that have demonstrated effectiveness were brought to scale in this large randomized trial that included 86 practices and more than 5000 participants. The investigators used risk of injurious falls as the primary outcome, as this outcome is considered the most clinically meaningful for the study population. The results, however, were disappointing: the multifactorial intervention in STRIDE did not result in a reduction of risk of injurious falls. Challenges in the implementation of this large trial may have contributed to its results; falls care managers, key to this multifactorial intervention, reported difficulties in navigating complex relationships with patients, families, study staff, and primary care practices during the study. Barriers reported included clinical space limitations, variable buy-in from providers, and turnover of practice staff and providers.3 Such implementation factors may have resulted in the divergent results between smaller clinical trials and this large-scale trial conducted across multiple settings.

The second study, by Stark et al, examined a home modification program and its effect on risk of falls. A prior Cochrane review examining the effect of home safety assessment and modification indicates that these strategies are effective in reducing the rate of falls as well as the risk of falling.4 The results of the current trial showed a reduction in the rate of falls but not in the risk of falling; however, this study did not examine outcomes of serious injurious falls, which may be more clinically meaningful. The Stark et al study adds to the existing literature showing that home modification may have an impact on fall rates. One noteworthy aspect of the Stark et al trial is the high adherence rate to home modification in a community-based approach; perhaps the investigators’ approach can be translated to real-world use.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The role of exercise programs in reducing fall rates is well established,5 but neither of these studies focused on exercise interventions. STRIDE offered community-based exercise program referral, but there is variability in such programs and study staff reported challenges in matching participants with appropriate exercise programs.3 Further studies that examine combinations of multifactorial falls risk reduction, exercise, and home safety, with careful consideration of implementation challenges to assure fidelity and adherence to the intervention, are needed to ascertain the best strategy for fall prevention for older adults at risk.

Given the results of these trials, it is difficult to recommend one falls prevention intervention over another. Clinicians should continue to identify falls risk factors using standardized assessments and determine which factors are modifiable.

Practice Points

- Incorporating assessments of falls risk in primary care is feasible, and such assessments can identify important risk factors.

- Clinicians and health systems should identify avenues, such as developing programmatic approaches, to providing home safety assessment and intervention, exercise options, medication review, and modification of other risk factors.

- Ensuring delivery of these elements reliably through programmatic approaches with adequate follow-up is key to preventing falls in this population.

—William W. Hung, MD, MPH

1. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:1701-1707. doi:10.1056/NEJM198812293192604

2. Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, et al. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD012221. doi:0.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2

3. Reckrey JM, Gazarian P, Reuben DB, et al. Barriers to implementation of STRIDE, a national study to prevent fall-related injuries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(5):1334-1342. doi:10.1111/jgs.17056

4. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD007146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3

5. Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012424. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

Study 1 Overview (Bhasin et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a multifactorial intervention for fall prevention on fall injury in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This was a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial conducted in 86 primary care practices across 10 health care systems.

Setting and participants: The primary care sites were selected based on the prespecified criteria of size, ability to implement the intervention, proximity to other practices, accessibility to electronic health records, and access to community-based exercise programs. The primary care practices were randomly assigned to intervention or control.

Eligibility criteria for participants at those practices included age 70 years or older, dwelling in the community, and having an increased risk of falls, as determined by a history of fall-related injury in the past year, 2 or more falls in the past year, or being afraid of falling because of problems with balance or walking. Exclusion criteria were inability to provide consent or lack of proxy consent for participants who were determined to have cognitive impairment based on screening, and inability to speak English or Spanish. A total of 2802 participants were enrolled in the intervention group, and 2649 participants were enrolled in the control group.

Intervention: The intervention contained 5 components: a standardized assessment of 7 modifiable risk factors for fall injuries; standardized protocol-driven recommendations for management of risk factors; an individualized care plan focused on 1 to 3 risk factors; implementation of care plans, including referrals to community-based programs; and follow-up care conducted by telephone or in person. The modifiable risk factors included impairment of strength, gait, or balance; use of medications related to falls; postural hypotension; problems with feet or footwear; visual impairment; osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency; and home safety hazards. The intervention was delivered by nurses who had completed online training modules and face-to-face training sessions focused on the intervention and motivational interviewing along with continuing education, in partnership with participants and their primary care providers. In the control group, participants received enhanced usual care, including an informational pamphlet, and were encouraged to discuss fall prevention with their primary care provider, including the results of their screening evaluation.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the first serious fall injury in a time-to-event analysis, defined as a fall resulting in a fracture (other than thoracic or lumbar vertebral fracture), joint dislocation, cut requiring closure, head injury requiring hospitalization, sprain or strain, bruising or swelling, or other serious injury. The secondary outcome was first patient-reported fall injury, also in a time-to-event analysis, ascertained by telephone interviews conducted every 4 months. Other outcomes included hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and other health care utilization. Adjudication of fall events and injuries was conducted by a team blinded to treatment assignment and verified using administrative claims data, encounter data, or electronic health record review.

Main results: The intervention and control groups were similar in terms of sex and age: 62.5% vs 61.5% of participants were women, and mean (SD) age was 79.9 (5.7) years and 79.5 (5.8) years, respectively. Other demographic characteristics were similar between groups. For the primary outcome, the rate of first serious injury was 4.9 per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 5.3 per 100 person-years in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.80-1.06; P = .25). For the secondary outcome of patient-reported fall injury, there were 25.6 events per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 28.6 in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P =0.004). Rates of hospitalization and other secondary outcomes were similar between groups.

Conclusion: The multifactorial STRIDE intervention did not reduce the rate of serious fall injury when compared to enhanced usual care. The intervention did result in lower rates of fall injury by patient report, but no other significant outcomes were seen.

Study 2 Overview (Stark et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a behavioral home hazard removal intervention for fall prevention on risk of fall in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This randomized clinical trial was conducted at a single site in St. Louis, Missouri. Participants were community-dwelling older adults who received services from the Area Agency on Aging (AAA). Inclusion criteria included age 65 years and older, having 1 or more falls in the previous 12 months or being worried about falling by self report, and currently receiving services from an AAA. Exclusion criteria included living in an institution or being severely cognitively impaired and unable to follow directions or report falls. Participants who met the criteria were contacted by phone and invited to participate. A total of 310 participants were enrolled in the study, with an equal number of participants assigned to the intervention and control groups.

Intervention: The intervention included hazard identification and removal after a comprehensive assessment of participants, their behaviors, and the environment; this assessment took place during the first visit, which lasted approximately 80 minutes. A home hazard removal plan was developed, and in the second session, which lasted approximately 40 minutes, remediation of hazards was carried out. A third session for home modification that lasted approximately 30 minutes was conducted, if needed. At 6 months after the intervention, a booster session to identify and remediate any new home hazards and address issues was conducted. Specific interventions, as identified by the assessment, included minor home repair such as grab bars, adaptive equipment, task modification, and education. Shared decision making that enabled older adults to control changes in their homes, self-management strategies to improve awareness, and motivational enhancement strategies to improve acceptance were employed. Scripted algorithms and checklists were used to deliver the intervention. For usual care, an annual assessment and referrals to community services, if needed, were conducted in the AAA.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the number of days to first fall in 12 months. Falls were defined as unintentional movements to the floor, ground, or object below knee level, and falls were recorded through a daily journal for 12 months. Participants were contacted by phone if they did not return the journal or reported a fall. Participants were interviewed to verify falls and determine whether a fall was injurious. Secondary outcomes included rate of falls per person per 12 months; daily activity performance measured using the Older Americans Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living scale; falls self-efficacy, which measures confidence performing daily activities without falling; and quality of life using the SF-36 at 12 months.

Main results: Most of the study participants were women (74%), and mean (SD) age was 75 (7.4) years. Study retention was similar between the intervention and control groups, with 82% completing the study in the intervention group compared with 81% in the control group. Fidelity to the intervention, as measured by a checklist by the interventionist, was 99%, and adherence to home modification, as measured by number of home modifications in use by self report, was high at 92% at 6 months and 91% at 12 months. For the primary outcome, fall hazard was not different between the intervention and control groups (hazard ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.66-1.27). For the secondary outcomes, the rate of falling was lower in the intervention group compared with the control group, with a relative risk of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.40-0.95). There was no difference in other secondary outcomes of daily activity performance, falls self-efficacy, or quality of life.

Conclusion: Despite high adherence to home modifications and fidelity to the intervention, this home hazard removal program did not reduce the risk of falling when compared to usual care. It did reduce the rate of falls, although no other effects were observed.

Commentary

Observational studies have identified factors that contribute to falls,1 and over the past 30 years a number of intervention trials designed to reduce the risk of falling have been conducted. A recent Cochrane review, published prior to the Bhasin et al and Stark et al trials, looked at the effect of multifactorial interventions for fall prevention across 62 trials that included 19,935 older adults living in the community. The review concluded that multifactorial interventions may reduce the rate of falls, but this conclusion was based on low-quality evidence and there was significant heterogeneity across the studies.2

The STRIDE randomized trial represents the latest effort to address the evidence gap around fall prevention, with the STRIDE investigators hoping this would be the definitive trial that leads to practice change in fall prevention. Smaller trials that have demonstrated effectiveness were brought to scale in this large randomized trial that included 86 practices and more than 5000 participants. The investigators used risk of injurious falls as the primary outcome, as this outcome is considered the most clinically meaningful for the study population. The results, however, were disappointing: the multifactorial intervention in STRIDE did not result in a reduction of risk of injurious falls. Challenges in the implementation of this large trial may have contributed to its results; falls care managers, key to this multifactorial intervention, reported difficulties in navigating complex relationships with patients, families, study staff, and primary care practices during the study. Barriers reported included clinical space limitations, variable buy-in from providers, and turnover of practice staff and providers.3 Such implementation factors may have resulted in the divergent results between smaller clinical trials and this large-scale trial conducted across multiple settings.

The second study, by Stark et al, examined a home modification program and its effect on risk of falls. A prior Cochrane review examining the effect of home safety assessment and modification indicates that these strategies are effective in reducing the rate of falls as well as the risk of falling.4 The results of the current trial showed a reduction in the rate of falls but not in the risk of falling; however, this study did not examine outcomes of serious injurious falls, which may be more clinically meaningful. The Stark et al study adds to the existing literature showing that home modification may have an impact on fall rates. One noteworthy aspect of the Stark et al trial is the high adherence rate to home modification in a community-based approach; perhaps the investigators’ approach can be translated to real-world use.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The role of exercise programs in reducing fall rates is well established,5 but neither of these studies focused on exercise interventions. STRIDE offered community-based exercise program referral, but there is variability in such programs and study staff reported challenges in matching participants with appropriate exercise programs.3 Further studies that examine combinations of multifactorial falls risk reduction, exercise, and home safety, with careful consideration of implementation challenges to assure fidelity and adherence to the intervention, are needed to ascertain the best strategy for fall prevention for older adults at risk.

Given the results of these trials, it is difficult to recommend one falls prevention intervention over another. Clinicians should continue to identify falls risk factors using standardized assessments and determine which factors are modifiable.

Practice Points

- Incorporating assessments of falls risk in primary care is feasible, and such assessments can identify important risk factors.

- Clinicians and health systems should identify avenues, such as developing programmatic approaches, to providing home safety assessment and intervention, exercise options, medication review, and modification of other risk factors.

- Ensuring delivery of these elements reliably through programmatic approaches with adequate follow-up is key to preventing falls in this population.

—William W. Hung, MD, MPH

Study 1 Overview (Bhasin et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a multifactorial intervention for fall prevention on fall injury in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This was a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial conducted in 86 primary care practices across 10 health care systems.

Setting and participants: The primary care sites were selected based on the prespecified criteria of size, ability to implement the intervention, proximity to other practices, accessibility to electronic health records, and access to community-based exercise programs. The primary care practices were randomly assigned to intervention or control.

Eligibility criteria for participants at those practices included age 70 years or older, dwelling in the community, and having an increased risk of falls, as determined by a history of fall-related injury in the past year, 2 or more falls in the past year, or being afraid of falling because of problems with balance or walking. Exclusion criteria were inability to provide consent or lack of proxy consent for participants who were determined to have cognitive impairment based on screening, and inability to speak English or Spanish. A total of 2802 participants were enrolled in the intervention group, and 2649 participants were enrolled in the control group.

Intervention: The intervention contained 5 components: a standardized assessment of 7 modifiable risk factors for fall injuries; standardized protocol-driven recommendations for management of risk factors; an individualized care plan focused on 1 to 3 risk factors; implementation of care plans, including referrals to community-based programs; and follow-up care conducted by telephone or in person. The modifiable risk factors included impairment of strength, gait, or balance; use of medications related to falls; postural hypotension; problems with feet or footwear; visual impairment; osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency; and home safety hazards. The intervention was delivered by nurses who had completed online training modules and face-to-face training sessions focused on the intervention and motivational interviewing along with continuing education, in partnership with participants and their primary care providers. In the control group, participants received enhanced usual care, including an informational pamphlet, and were encouraged to discuss fall prevention with their primary care provider, including the results of their screening evaluation.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the first serious fall injury in a time-to-event analysis, defined as a fall resulting in a fracture (other than thoracic or lumbar vertebral fracture), joint dislocation, cut requiring closure, head injury requiring hospitalization, sprain or strain, bruising or swelling, or other serious injury. The secondary outcome was first patient-reported fall injury, also in a time-to-event analysis, ascertained by telephone interviews conducted every 4 months. Other outcomes included hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and other health care utilization. Adjudication of fall events and injuries was conducted by a team blinded to treatment assignment and verified using administrative claims data, encounter data, or electronic health record review.

Main results: The intervention and control groups were similar in terms of sex and age: 62.5% vs 61.5% of participants were women, and mean (SD) age was 79.9 (5.7) years and 79.5 (5.8) years, respectively. Other demographic characteristics were similar between groups. For the primary outcome, the rate of first serious injury was 4.9 per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 5.3 per 100 person-years in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.80-1.06; P = .25). For the secondary outcome of patient-reported fall injury, there were 25.6 events per 100 person-years in the intervention group and 28.6 in the control group, with a hazard ratio of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99; P =0.004). Rates of hospitalization and other secondary outcomes were similar between groups.

Conclusion: The multifactorial STRIDE intervention did not reduce the rate of serious fall injury when compared to enhanced usual care. The intervention did result in lower rates of fall injury by patient report, but no other significant outcomes were seen.

Study 2 Overview (Stark et al)

Objective: To examine the effect of a behavioral home hazard removal intervention for fall prevention on risk of fall in community-dwelling older adults.

Design: This randomized clinical trial was conducted at a single site in St. Louis, Missouri. Participants were community-dwelling older adults who received services from the Area Agency on Aging (AAA). Inclusion criteria included age 65 years and older, having 1 or more falls in the previous 12 months or being worried about falling by self report, and currently receiving services from an AAA. Exclusion criteria included living in an institution or being severely cognitively impaired and unable to follow directions or report falls. Participants who met the criteria were contacted by phone and invited to participate. A total of 310 participants were enrolled in the study, with an equal number of participants assigned to the intervention and control groups.

Intervention: The intervention included hazard identification and removal after a comprehensive assessment of participants, their behaviors, and the environment; this assessment took place during the first visit, which lasted approximately 80 minutes. A home hazard removal plan was developed, and in the second session, which lasted approximately 40 minutes, remediation of hazards was carried out. A third session for home modification that lasted approximately 30 minutes was conducted, if needed. At 6 months after the intervention, a booster session to identify and remediate any new home hazards and address issues was conducted. Specific interventions, as identified by the assessment, included minor home repair such as grab bars, adaptive equipment, task modification, and education. Shared decision making that enabled older adults to control changes in their homes, self-management strategies to improve awareness, and motivational enhancement strategies to improve acceptance were employed. Scripted algorithms and checklists were used to deliver the intervention. For usual care, an annual assessment and referrals to community services, if needed, were conducted in the AAA.

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome of the study was the number of days to first fall in 12 months. Falls were defined as unintentional movements to the floor, ground, or object below knee level, and falls were recorded through a daily journal for 12 months. Participants were contacted by phone if they did not return the journal or reported a fall. Participants were interviewed to verify falls and determine whether a fall was injurious. Secondary outcomes included rate of falls per person per 12 months; daily activity performance measured using the Older Americans Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living scale; falls self-efficacy, which measures confidence performing daily activities without falling; and quality of life using the SF-36 at 12 months.

Main results: Most of the study participants were women (74%), and mean (SD) age was 75 (7.4) years. Study retention was similar between the intervention and control groups, with 82% completing the study in the intervention group compared with 81% in the control group. Fidelity to the intervention, as measured by a checklist by the interventionist, was 99%, and adherence to home modification, as measured by number of home modifications in use by self report, was high at 92% at 6 months and 91% at 12 months. For the primary outcome, fall hazard was not different between the intervention and control groups (hazard ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.66-1.27). For the secondary outcomes, the rate of falling was lower in the intervention group compared with the control group, with a relative risk of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.40-0.95). There was no difference in other secondary outcomes of daily activity performance, falls self-efficacy, or quality of life.

Conclusion: Despite high adherence to home modifications and fidelity to the intervention, this home hazard removal program did not reduce the risk of falling when compared to usual care. It did reduce the rate of falls, although no other effects were observed.

Commentary

Observational studies have identified factors that contribute to falls,1 and over the past 30 years a number of intervention trials designed to reduce the risk of falling have been conducted. A recent Cochrane review, published prior to the Bhasin et al and Stark et al trials, looked at the effect of multifactorial interventions for fall prevention across 62 trials that included 19,935 older adults living in the community. The review concluded that multifactorial interventions may reduce the rate of falls, but this conclusion was based on low-quality evidence and there was significant heterogeneity across the studies.2

The STRIDE randomized trial represents the latest effort to address the evidence gap around fall prevention, with the STRIDE investigators hoping this would be the definitive trial that leads to practice change in fall prevention. Smaller trials that have demonstrated effectiveness were brought to scale in this large randomized trial that included 86 practices and more than 5000 participants. The investigators used risk of injurious falls as the primary outcome, as this outcome is considered the most clinically meaningful for the study population. The results, however, were disappointing: the multifactorial intervention in STRIDE did not result in a reduction of risk of injurious falls. Challenges in the implementation of this large trial may have contributed to its results; falls care managers, key to this multifactorial intervention, reported difficulties in navigating complex relationships with patients, families, study staff, and primary care practices during the study. Barriers reported included clinical space limitations, variable buy-in from providers, and turnover of practice staff and providers.3 Such implementation factors may have resulted in the divergent results between smaller clinical trials and this large-scale trial conducted across multiple settings.

The second study, by Stark et al, examined a home modification program and its effect on risk of falls. A prior Cochrane review examining the effect of home safety assessment and modification indicates that these strategies are effective in reducing the rate of falls as well as the risk of falling.4 The results of the current trial showed a reduction in the rate of falls but not in the risk of falling; however, this study did not examine outcomes of serious injurious falls, which may be more clinically meaningful. The Stark et al study adds to the existing literature showing that home modification may have an impact on fall rates. One noteworthy aspect of the Stark et al trial is the high adherence rate to home modification in a community-based approach; perhaps the investigators’ approach can be translated to real-world use.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

The role of exercise programs in reducing fall rates is well established,5 but neither of these studies focused on exercise interventions. STRIDE offered community-based exercise program referral, but there is variability in such programs and study staff reported challenges in matching participants with appropriate exercise programs.3 Further studies that examine combinations of multifactorial falls risk reduction, exercise, and home safety, with careful consideration of implementation challenges to assure fidelity and adherence to the intervention, are needed to ascertain the best strategy for fall prevention for older adults at risk.

Given the results of these trials, it is difficult to recommend one falls prevention intervention over another. Clinicians should continue to identify falls risk factors using standardized assessments and determine which factors are modifiable.

Practice Points

- Incorporating assessments of falls risk in primary care is feasible, and such assessments can identify important risk factors.

- Clinicians and health systems should identify avenues, such as developing programmatic approaches, to providing home safety assessment and intervention, exercise options, medication review, and modification of other risk factors.

- Ensuring delivery of these elements reliably through programmatic approaches with adequate follow-up is key to preventing falls in this population.

—William W. Hung, MD, MPH

1. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:1701-1707. doi:10.1056/NEJM198812293192604

2. Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, et al. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD012221. doi:0.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2

3. Reckrey JM, Gazarian P, Reuben DB, et al. Barriers to implementation of STRIDE, a national study to prevent fall-related injuries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(5):1334-1342. doi:10.1111/jgs.17056

4. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD007146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3

5. Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012424. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

1. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:1701-1707. doi:10.1056/NEJM198812293192604

2. Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, et al. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD012221. doi:0.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2

3. Reckrey JM, Gazarian P, Reuben DB, et al. Barriers to implementation of STRIDE, a national study to prevent fall-related injuries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(5):1334-1342. doi:10.1111/jgs.17056

4. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD007146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3

5. Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012424. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

FDA allows import of 2 million cans of baby formula from U.K.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is easing rules to allow infant formula imports from the United Kingdom, which would bring about 2 million cans to the U.S. in coming weeks.

Kendal Nutricare will be able to offer certain infant formula products under the Kendamil brand to ease the nationwide formula shortage.

“Importantly, we anticipate additional infant formula products may be safely and quickly imported in the U.S. in the near-term, based on ongoing discussions with manufacturers and suppliers worldwide,” Robert Califf, MD, the FDA commissioner, said in a statement.

Kendal Nutricare has more than 40,000 cans in stock for immediate dispatch, the FDA said, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is talking to the company about the best ways to get the products to the U.S. as quickly as possible.

Kendamil has set up a website for consumers to receive updates and find products once they arrive in the U.S.

After an evaluation, the FDA said it had no safety or nutrition concerns about the products. The evaluation reviewed the company’s microbiological testing, labeling, and information about facility production and inspection history.

On May 24, the FDA announced that Abbott Nutrition will release about 300,000 cans of its EleCare specialty amino acid-based formula to families that need urgent, life-sustaining supplies. The products had more tests for microbes before release.

Although some EleCare products were included in Abbott’s infant formula recall earlier this year, the cans that will be released were in different lots, have never been released, and have been maintained in storage, the FDA said.

“These EleCare product lots were not part of the recall but have been on hold due to concerns that they were produced under unsanitary conditions observed at Abbott Nutrition’s Sturgis, Michigan, facility,” the FDA wrote.

The FDA encourages parents and caregivers to talk with their health care providers to weigh the potential risk of bacterial infection with the critical need for the product, based on its special dietary formulation for infants with severe food allergies or gut disorders.

The FDA also said that Abbott confirmed the EleCare products will be the first formula produced at the Sturgis facility when it restarts production soon. Other specialty metabolic formulas will follow.

Abbott plans to restart production at the Sturgis facility on June 4, the company said in a statement, noting that the early batches of EleCare would be available to consumers around June 20.

The products being released now are EleCare (for infants under 1 year) and EleCare Jr. (for ages 1 and older). Those who want to request products should contact their health care providers or call Abbott directly at 800-881-0876.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is easing rules to allow infant formula imports from the United Kingdom, which would bring about 2 million cans to the U.S. in coming weeks.

Kendal Nutricare will be able to offer certain infant formula products under the Kendamil brand to ease the nationwide formula shortage.

“Importantly, we anticipate additional infant formula products may be safely and quickly imported in the U.S. in the near-term, based on ongoing discussions with manufacturers and suppliers worldwide,” Robert Califf, MD, the FDA commissioner, said in a statement.

Kendal Nutricare has more than 40,000 cans in stock for immediate dispatch, the FDA said, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is talking to the company about the best ways to get the products to the U.S. as quickly as possible.

Kendamil has set up a website for consumers to receive updates and find products once they arrive in the U.S.

After an evaluation, the FDA said it had no safety or nutrition concerns about the products. The evaluation reviewed the company’s microbiological testing, labeling, and information about facility production and inspection history.

On May 24, the FDA announced that Abbott Nutrition will release about 300,000 cans of its EleCare specialty amino acid-based formula to families that need urgent, life-sustaining supplies. The products had more tests for microbes before release.

Although some EleCare products were included in Abbott’s infant formula recall earlier this year, the cans that will be released were in different lots, have never been released, and have been maintained in storage, the FDA said.

“These EleCare product lots were not part of the recall but have been on hold due to concerns that they were produced under unsanitary conditions observed at Abbott Nutrition’s Sturgis, Michigan, facility,” the FDA wrote.

The FDA encourages parents and caregivers to talk with their health care providers to weigh the potential risk of bacterial infection with the critical need for the product, based on its special dietary formulation for infants with severe food allergies or gut disorders.

The FDA also said that Abbott confirmed the EleCare products will be the first formula produced at the Sturgis facility when it restarts production soon. Other specialty metabolic formulas will follow.

Abbott plans to restart production at the Sturgis facility on June 4, the company said in a statement, noting that the early batches of EleCare would be available to consumers around June 20.

The products being released now are EleCare (for infants under 1 year) and EleCare Jr. (for ages 1 and older). Those who want to request products should contact their health care providers or call Abbott directly at 800-881-0876.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is easing rules to allow infant formula imports from the United Kingdom, which would bring about 2 million cans to the U.S. in coming weeks.

Kendal Nutricare will be able to offer certain infant formula products under the Kendamil brand to ease the nationwide formula shortage.

“Importantly, we anticipate additional infant formula products may be safely and quickly imported in the U.S. in the near-term, based on ongoing discussions with manufacturers and suppliers worldwide,” Robert Califf, MD, the FDA commissioner, said in a statement.

Kendal Nutricare has more than 40,000 cans in stock for immediate dispatch, the FDA said, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is talking to the company about the best ways to get the products to the U.S. as quickly as possible.

Kendamil has set up a website for consumers to receive updates and find products once they arrive in the U.S.

After an evaluation, the FDA said it had no safety or nutrition concerns about the products. The evaluation reviewed the company’s microbiological testing, labeling, and information about facility production and inspection history.

On May 24, the FDA announced that Abbott Nutrition will release about 300,000 cans of its EleCare specialty amino acid-based formula to families that need urgent, life-sustaining supplies. The products had more tests for microbes before release.

Although some EleCare products were included in Abbott’s infant formula recall earlier this year, the cans that will be released were in different lots, have never been released, and have been maintained in storage, the FDA said.

“These EleCare product lots were not part of the recall but have been on hold due to concerns that they were produced under unsanitary conditions observed at Abbott Nutrition’s Sturgis, Michigan, facility,” the FDA wrote.

The FDA encourages parents and caregivers to talk with their health care providers to weigh the potential risk of bacterial infection with the critical need for the product, based on its special dietary formulation for infants with severe food allergies or gut disorders.

The FDA also said that Abbott confirmed the EleCare products will be the first formula produced at the Sturgis facility when it restarts production soon. Other specialty metabolic formulas will follow.

Abbott plans to restart production at the Sturgis facility on June 4, the company said in a statement, noting that the early batches of EleCare would be available to consumers around June 20.

The products being released now are EleCare (for infants under 1 year) and EleCare Jr. (for ages 1 and older). Those who want to request products should contact their health care providers or call Abbott directly at 800-881-0876.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

CDC signs off on COVID boosters in children ages 5-11

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, signed off May 19 on an advisory panel’s recommendation that children ages 5 to 11 years should receive a Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster dose at least 5 months after completion of the primary series.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 11:1, with one abstention, on a question about whether it recommended these additional shots in this age group.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 17 amended the emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine to cover a single booster dose for administration to individuals 5 through 11 years of age.

At the request of CDC staff, ACIP members considered whether there should be softer wording for this recommendation, stating that children in this age group “may” receive a booster. This kind of phrasing would better reflect uncertainty about the course of COVID in the months ahead and allow flexibility for a stronger recommendation in the fall.

ACIP panelists and members of key groups argued strongly for a “should” recommendation, despite the uncertainties.

They also called for stronger efforts to make sure eligible children received their initial COVID-19 shots. Data gathered between November and April show only 14.4% of children ages 5 to 11 in rural areas have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination, with top rates of 39.8% in large urban communities and 36% in larger suburban regions, CDC staff said.

CDC staff also said nearly 40% of parents in rural areas reported that their children’s pediatricians did not recommend COVID-19 vaccinations, compared with only 8% of parents in urban communities. These figures concerned ACIP members and liaisons from medical associations who take part in the panel’s deliberations but not in its votes.

“People will hear the word ‘m-a-y’ as ‘m-e-h’,” said Patricia Stinchfield, RN, MS, who served as the liaison for National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners to ACIP. “I think we need to add urgency” to efforts to increase use of COVID vaccinations, she said.

Voting no on Thursday was Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, of Vanderbilt University. She explained after the vote that she is in favor of having young children vaccinated, but she’s concerned about the low rates of initial uptake of the COVID-19 shots.

“Boosters are great once we’ve gotten everyone their first round,” she said. “That needs to be our priority in this.”

Sandra Fryhofer, MD, the American Medical Association’s liaison to ACIP, stressed the add-on benefits from more widespread vaccination of children against COVID. Dr. Fryhofer said she serves adults in her practice as an internal medicine physician, with many of her patients being at high risk for complications from COVID.

Too many people are assuming the spread of infections in the community has lessened the risk of the virus, Dr. Fryhofer said.

“Not everyone’s had COVID yet, and my patients will be likely to get COVID if their grandchildren get it. We’re going through pandemic fatigue in this country,” she said. “Unfortunately, masks are now more off than on. Winter’s coming. They’re more variants” of the virus likely to emerge.

The data emerging so far suggests COVID vaccines will become a three-dose medicine, as is already accepted for other shots like hepatitis B vaccine, Dr. Fryhofer said.

Data gathered to date show the vaccine decreases risk of hospitalization for COVID and for complications such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), she said.

“The bottom line is children in this age group are getting COVID,” Dr. Fryhofer said of the 5- to 11-year-olds. “Some do fine. Some are getting real sick. Some are hospitalized, some have died.”

At the meeting, CDC staff cited data from a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine in March showing that vaccination had reduced the risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 among children 5 to 11 years of age by two-thirds during the Omicron period; most children with critical COVID-19 were unvaccinated.

COVID-19 led to 66 deaths among children ages 5 to 11 in the October 2020 to October 2021 timeframe, said ACIP member Matthew F. Daley, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Colorado during a presentation to his fellow panel members.

Parents may underestimate children’s risk from COVID and thus hold off on vaccinations, stressed AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD, in a statement issued after the meeting.

“It is concerning that only 1 in 3 children between the ages of 5 and 11 in the United States have received two doses of the vaccine, in part because parents believe them to be at lower risk for severe disease than adults,” Dr. Harmon said. “But the Omicron variant brought about change that should alter that calculus.”

Responding to early data

As Dr. Fryhofer put it, the medical community has been learning in “real time” about how COVID vaccines work and how to use them.

The EUA granted on May 17 for booster shots for children ages 5 to 11 was based on an analysis of immune response data in a subset of children from an ongoing randomized placebo-controlled trial, the FDA said.

Antibody responses were evaluated in 67 study participants who received a booster dose 7 to 9 months after completing a two-dose primary series of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. The EUA for the booster shot was intended to respond to emerging data that suggest that vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 wanes after the second dose of the vaccine, the FDA said.

CDC seeks help tracking vaccine complications

At the ACIP meeting, a top CDC vaccine-safety official, Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, asked physicians to make sure their patients know about the agency’s V-Safe program for gathering reports from the public about their experiences with COVID vaccines. This is intended to help the CDC monitor for side effects of these medications.

“We need your help,” he said during a presentation about adverse events reported to date in children ages 5 to 11 who took the Pfizer vaccine.

About 18.1 million doses of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine have been administered to children ages 5 to 11 years in the United States so far. Most of the reports of adverse events following vaccination were not serious, he said. But there were 20 reports of myocarditis verified to meet CDC case definition among children ages 5 to 11 years.

One case involved a death with histopathologic evidence of myocarditis on autopsy. The CDC continues to assist with case review, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, signed off May 19 on an advisory panel’s recommendation that children ages 5 to 11 years should receive a Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine booster dose at least 5 months after completion of the primary series.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 11:1, with one abstention, on a question about whether it recommended these additional shots in this age group.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 17 amended the emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine to cover a single booster dose for administration to individuals 5 through 11 years of age.

At the request of CDC staff, ACIP members considered whether there should be softer wording for this recommendation, stating that children in this age group “may” receive a booster. This kind of phrasing would better reflect uncertainty about the course of COVID in the months ahead and allow flexibility for a stronger recommendation in the fall.

ACIP panelists and members of key groups argued strongly for a “should” recommendation, despite the uncertainties.

They also called for stronger efforts to make sure eligible children received their initial COVID-19 shots. Data gathered between November and April show only 14.4% of children ages 5 to 11 in rural areas have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination, with top rates of 39.8% in large urban communities and 36% in larger suburban regions, CDC staff said.

CDC staff also said nearly 40% of parents in rural areas reported that their children’s pediatricians did not recommend COVID-19 vaccinations, compared with only 8% of parents in urban communities. These figures concerned ACIP members and liaisons from medical associations who take part in the panel’s deliberations but not in its votes.

“People will hear the word ‘m-a-y’ as ‘m-e-h’,” said Patricia Stinchfield, RN, MS, who served as the liaison for National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners to ACIP. “I think we need to add urgency” to efforts to increase use of COVID vaccinations, she said.

Voting no on Thursday was Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, of Vanderbilt University. She explained after the vote that she is in favor of having young children vaccinated, but she’s concerned about the low rates of initial uptake of the COVID-19 shots.

“Boosters are great once we’ve gotten everyone their first round,” she said. “That needs to be our priority in this.”

Sandra Fryhofer, MD, the American Medical Association’s liaison to ACIP, stressed the add-on benefits from more widespread vaccination of children against COVID. Dr. Fryhofer said she serves adults in her practice as an internal medicine physician, with many of her patients being at high risk for complications from COVID.

Too many people are assuming the spread of infections in the community has lessened the risk of the virus, Dr. Fryhofer said.