User login

‘Anxiety sensitivity’ tied to psychodermatologic disorders

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

Shedding Light on Onychomadesis

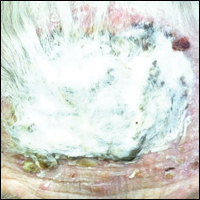

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

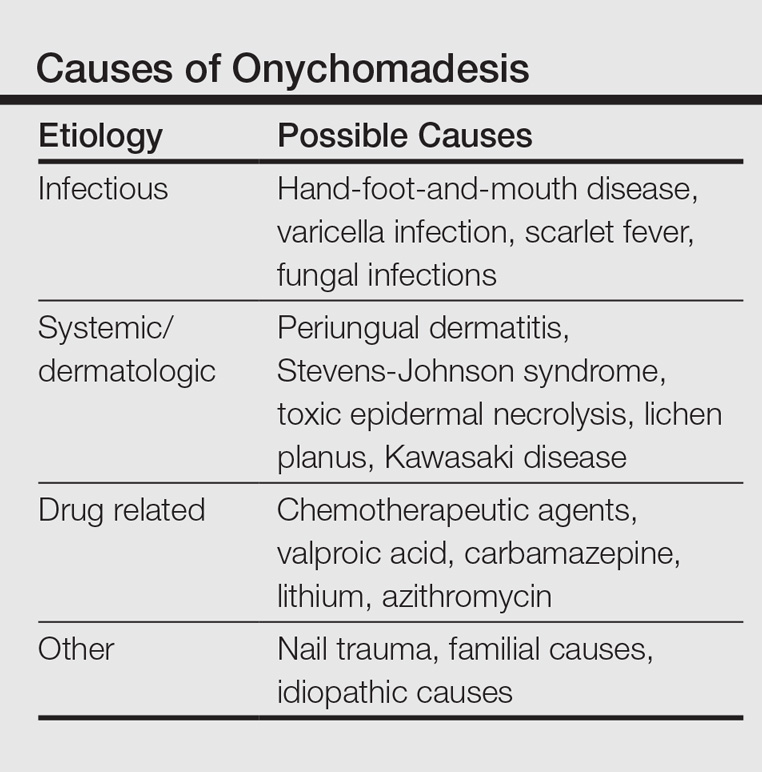

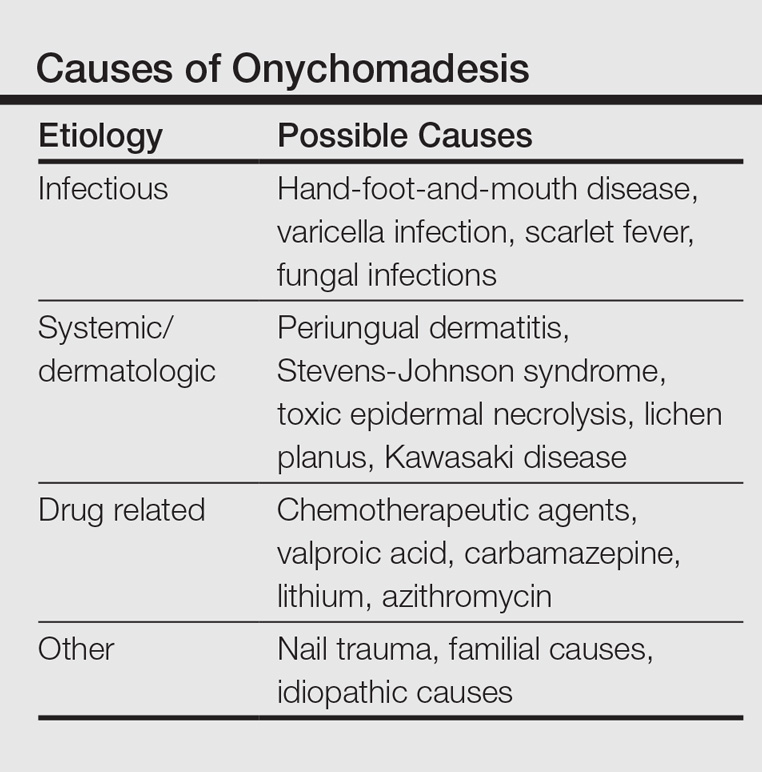

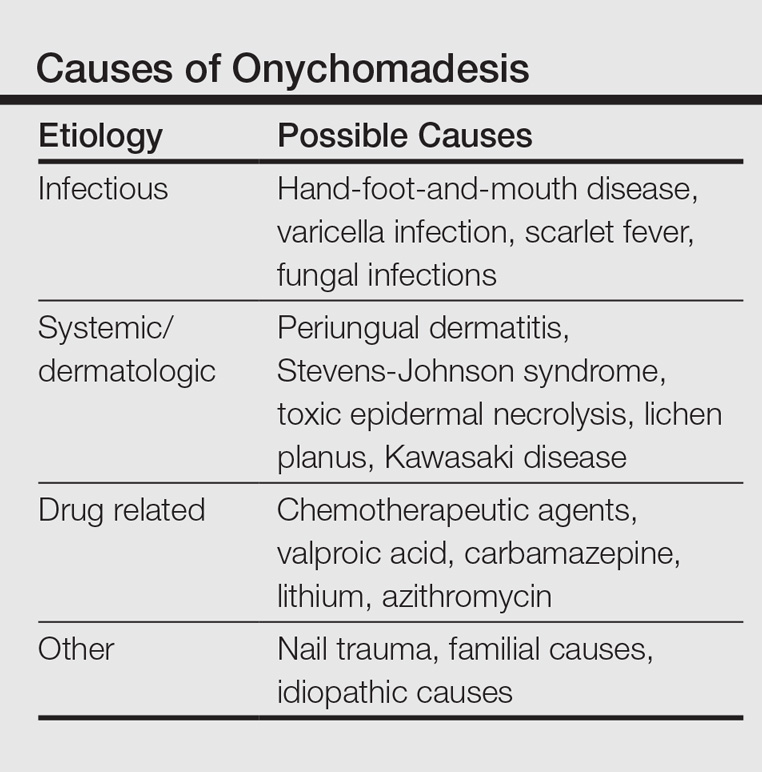

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

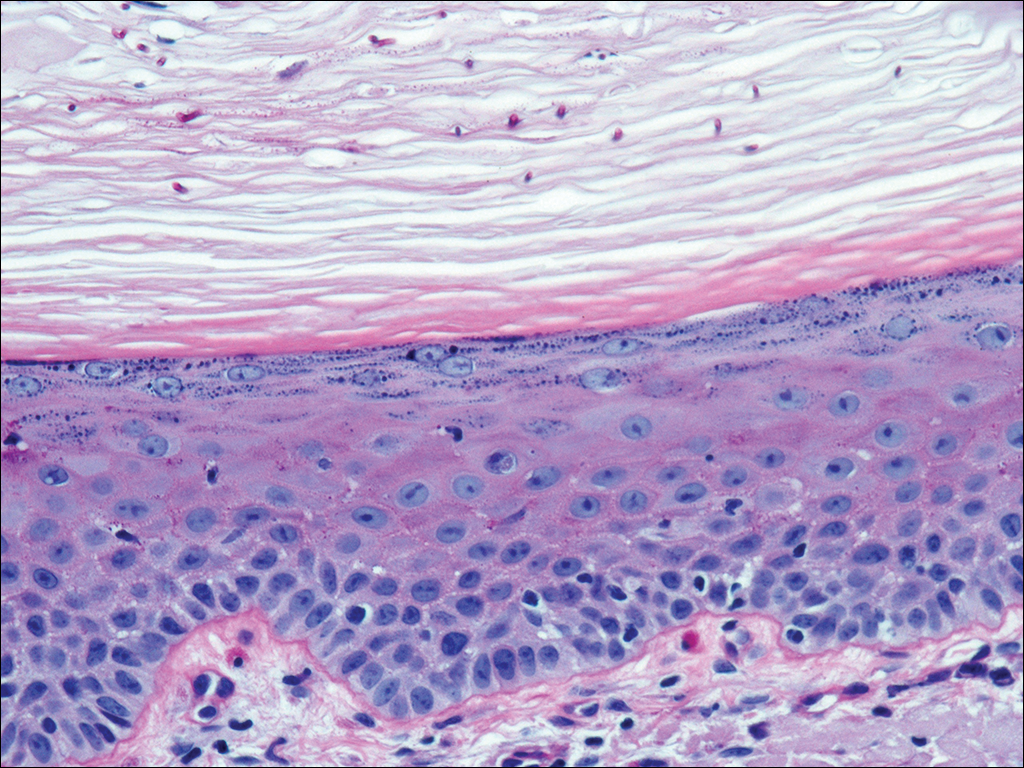

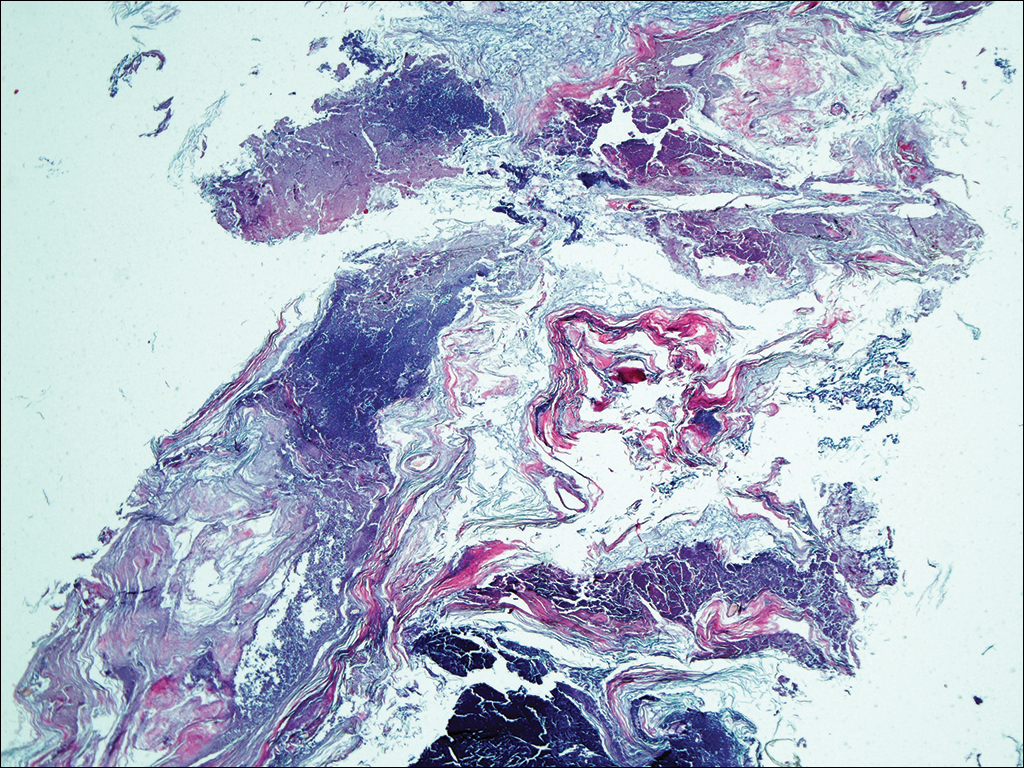

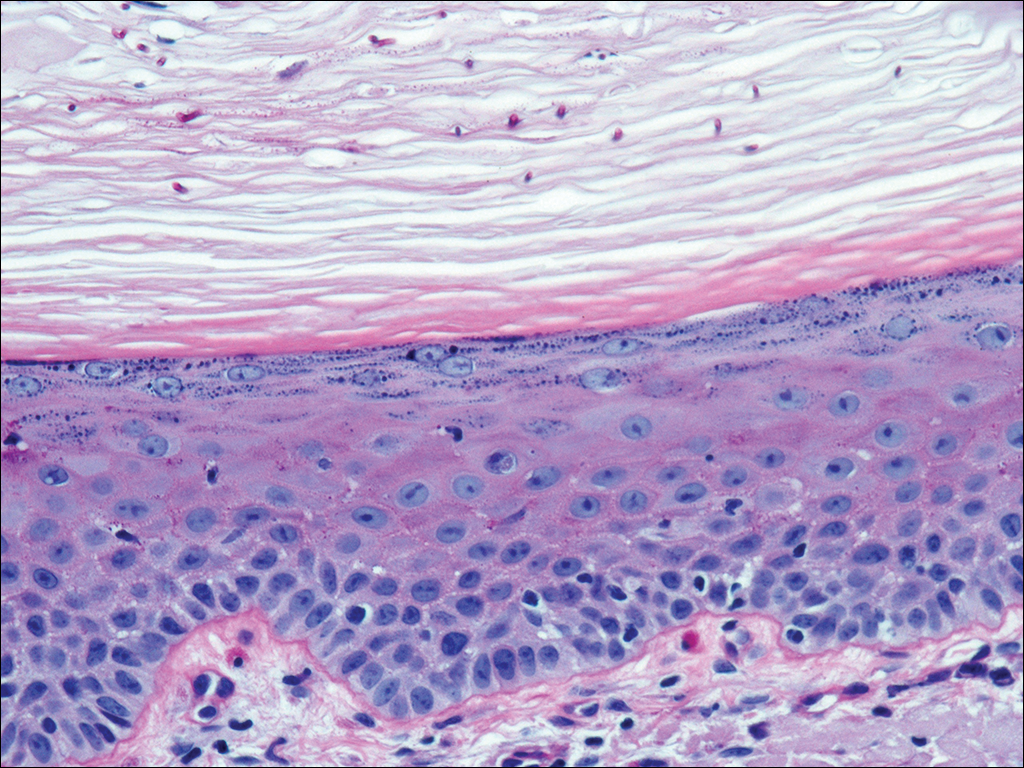

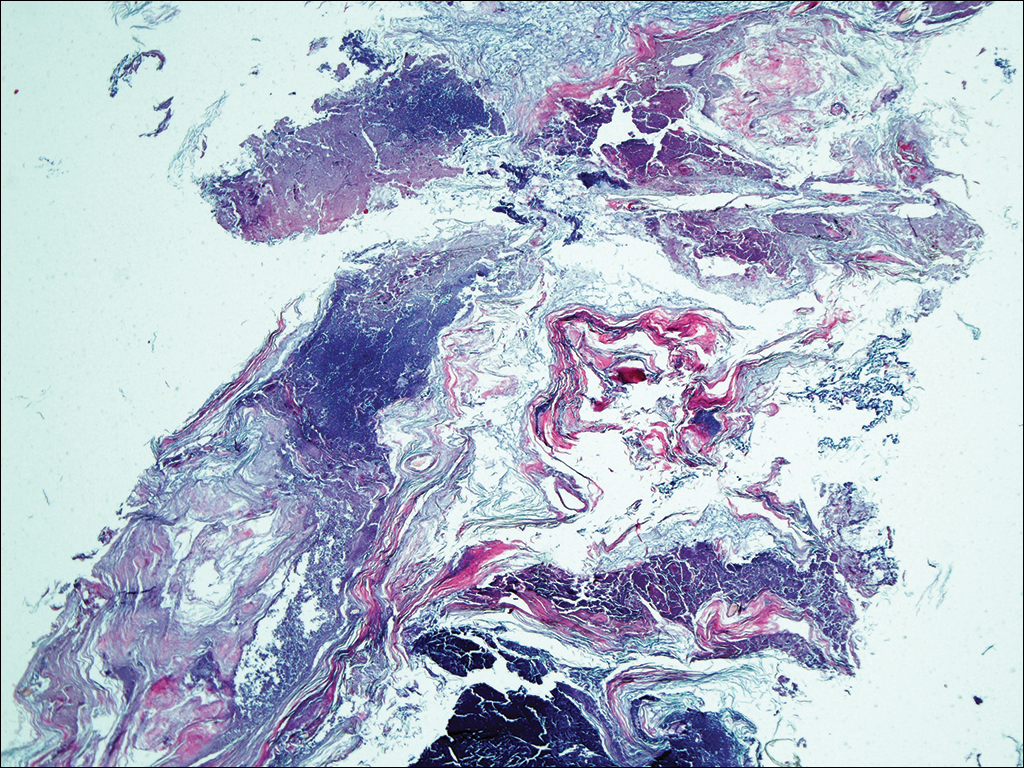

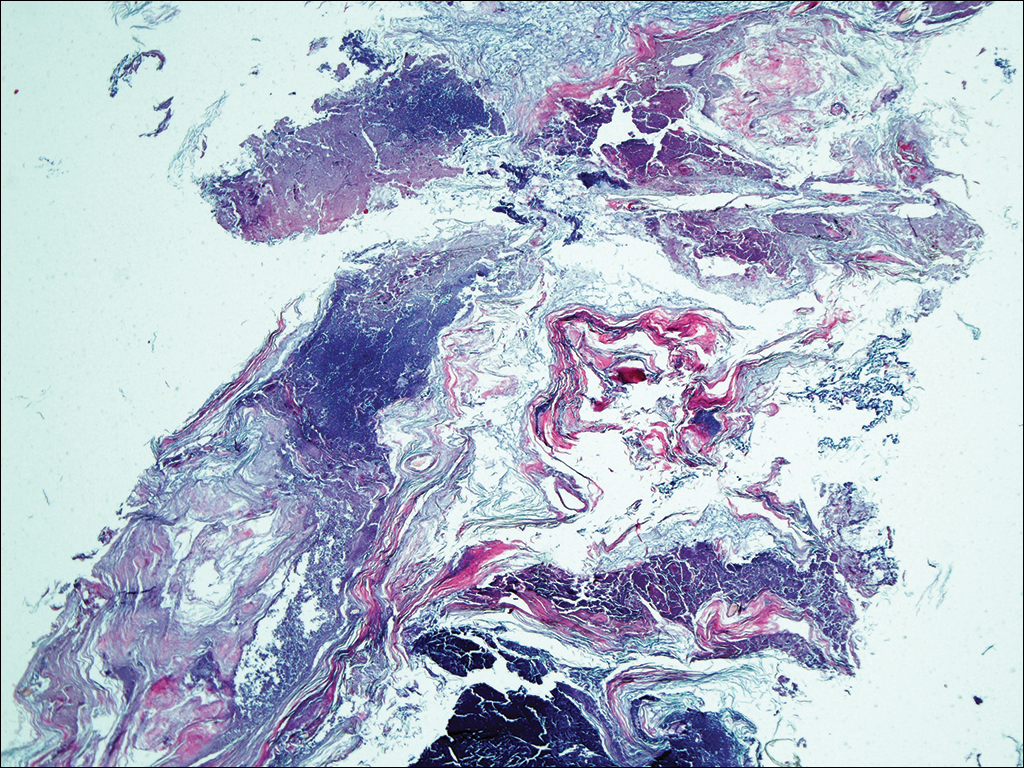

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

Onychomadesis is an acute, noninflammatory, painless, proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. It occurs due to an abrupt stoppage of nail production by matrix cells, producing temporary cessation of nail growth with or without subsequent complete shedding of nails.1-10 Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.4,11 Onychomadesis may be related to systemic and dermatologic diseases, drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids), nail trauma, fever, or infection,5 and a connection between onychomadesis and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) was first described by Clementz et al12 following outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Epidemiology

Onychomadesis has been observed in children of all ages including neonates. Neonatal onychomadesis is thought to be related to perinatal stressors and birth trauma, with possible exacerbation by superimposed candidiasis.10 Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al1 noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.1

Clementz et al12 first proposed the association between onychomadesis and HFMD in 2000. Patients with a history of HFMD were found to be 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).4 A common pathogen for HFMD is coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6),13,14 but the mechanism of onychomadesis in HFMD remains unclear.5,7,13 Outbreaks of HFMD have been reported in Spain, Finland, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Singapore, and China.15 During an outbreak of HFMD in Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis following CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains.16 There also have been observed differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis by age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (range, 9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (range, 24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (range, 33–42 months), with an average of 4 nails shed per case.17 A study in Spain also found a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting, with 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.18

Etiology

Local trauma to the nail bed is the most common cause of single-digit onychomadesis.4 Multiple-digit involvement suggests a systemic etiology such as fever, erythroderma, and Kawasaki disease; use of drugs (eg, chemotherapeutic agents, anticonvulsants, lithium, retinoids); and viral infections such as HFMD and varicella at the infantile age (Table).5,9,19 Most drug-related nail changes are the outcome of acute toxicity to the proliferating nail matrix epithelium. If onychomadesis affects all nails at the same level, the patient’s history of medication use and other treatments taken 2 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the nail findings should be evaluated. Chemotherapeutic agents produce nail changes in a high proportion of patients, which often are related to drug dosage. These effects also are reproducible with re-administration of the drug.20 Onychomadesis also has been reported as a possible side effect of anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (VPA).21 One study evaluating the link between VPA and onychomadesis indicated that nail changes may be due to a disturbance of zinc metabolism.22 However, the pathomechanism of onychomadesis associated with VPA treatment remains unclear.21 Onychomadesis also has developed after an allergic drug reaction to oral penicillin V after treatment of a sore throat in a 23-month-old child.23

Nail involvement has been reported in 10% of cases of inflammatory conditions such as lichen planus21; however, it may be more common but underrecognized and underreported. Grover et al9 indicated that lichen planus–induced severe inflammation in the matrix of the nail unit leading to a temporary growth arrest was the possible mechanism leading to nail shedding. Prompt systemic and intramatricial steroid treatment of lichen planus is required to avoid potential scarring of the nail matrix and permanent damage.9

Onychomadesis also has been reported following varicella infection (chickenpox). Podder et al19 reported the case of a 7-year-old girl who had recovered from a varicella infection 5 weeks prior and presented with onychomadesis of the right index fingernail with all other fingernails and toenails appearing normal. Kocak and Koçak5 reported onychomadesis in 2 sisters with varicella infection. There are few reported cases, so it is still unclear whether varicella infection is an inciting factor.19

One of the most studied viral infections linked to onychomadesis is HFMD, which is a common viral infection that mostly affects children younger than 10 years.1 The precise mechanism of onychomadesis for these viral infection events remains unclear.7,10,13 Several theories have been delineated, including nail matrix arrest from fever occurring during HFMD.6 However, this cause is unlikely, as fevers are typically low grade and present only for a few hours.4,6,13 Direct inflammation spreading from skin lesions of HFMD around the nails or maceration associated with finger blisters could cause onychomadesis.1,5,7 Haneke24 hypothesized that nail shedding may be the consequence of vesicles localized in the periungual tissue, but studies have shown incidence without prior lesions on the fingers and no relationship between nail matrix arrest and severity of HFMD.5,6,13 Bettoli et al25 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix might be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism. Osterback et al14 used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to detect CVA6 in fragmented nails from 2 children and 1 parent following an HFMD episode, suggesting that virus replication could damage the nail matrix, resulting in onychomadesis. Cabrerizo et al18 also suggested that virus replication directly damages the nail matrix based on the presence of CVA6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by HFMD, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible.8 Additional studies are needed to clarify the virus-associated mechanism of nail matrix arrest.6 Finally, frequent washing of hands15 resulting in maceration, Candida infection, and allergic contact dermatitis2 may be possible causes. It is unclear if onychomadesis following HFMD is related to viral replication, inflammation, or intensive hygienic measures, and further investigation is needed.2,15

Clinical Characteristics

The ventral floor is the site of the germinal matrix and is responsible for 90% of nail production. As a result, more of the nail plate substance is produced proximally, leading to a natural convex curvature from the proximal to distal nail.11 Beau lines are transverse ridging of the nail plates.6 Onychomadesis may be viewed as a more severe form of Beau lines, with complete separation and possible shedding of the nail plate (Figure).3,4 In both cases, an insult to the nail matrix is followed by recovery and production of the nail plate at the nail matrix.4 In Beau lines, slowing or disruption of cell growth from the proximal matrix results in a thinner nail plate, leading to transverse depressions. Onychomadesis has a similar pathophysiology but is associated with a complete halt in the nail plate production.3

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesis is made clinically.3,10 Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate,3,11 which allows for differentiation between Beau lines and complete nail shedding. Additionally, any signs of nail trauma need to be noted, as well as pain, swelling, or pruritus, as these symptoms also can guide in determining the etiology of the nail dystrophy. Ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis, as the defect can be identified beneath the proximal nail fold.3,26 When it occurs after HFMD or varicella, onychomadesis tends to present in 28 to 40 days following infection.4,6,10 Physicians should consider underlying associations. A review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to development of nail changes often will identify the causative disease.4 Each patient should be evaluated for recent nail trauma; medications; viral infection; and autoimmune, systemic, and inflammatory diseases.

Treatment

Onychomadesis typically is mild and self-limited.4,10 There is no specific treatment,10 but a conservative approach to management is recommended. Treatment of any underlying medical conditions or discontinuation of an offending medication may help to prevent recurrent onychomadesis.3 Supportive care along with protection of the nail bed by maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails is recommended.4 In some cases, onychomadesis has been treated with topical application of urea cream 40% under occlusion27 or halcinonide cream 0.1% under occlusion for 5 to 6 days,28 but these treatments have not been universally effective.3 External use of basic fibroblast growth factor to stimulate new regrowth of the nail plate has been advocated.3 It is important to reassure patients that as long as the underlying causes are eliminated and the nail matrix has not been permanently scarred, the nails should grow back within 12 weeks or sooner in children. Thus, typically only reassurance and counseling of parents/guardians is required for onychomadesis in children.1,2 However, the nails may be dystrophic or fail to regrow if there is poor peripheral circulation or permanent nail matrix damage.

Conclusion

Fortunately, onychomadesis is self-limited. Physicians should look for underlying causes of onychomadesis, including a history of viral infections such as HFMD and varicella as well as systemic diseases and use of medications. As long as any underlying disorder or condition has been resolved, spontaneous regrowth of healthy nails usually but not always occurs within 12 weeks or sooner in children.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

- Nag SS, Dutta A, Mandal RK. Delayed cutaneous findings of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:42-44.

- Tan ZH, Koh MJ. Nail shedding following hand, foot and mouth disease. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:665.

- Braswell MA, Daniel CR, Brodell RT. Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia: a unifying hypothesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:849-855.

- Clark CM, Silverberg NB, Weinberg JM. What is your diagnosis? onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Cutis. 2015;95:312, 319-320.

- Kocak AY, Koçak O. Onychomadesis in two sisters induced by varicella infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E108-E109.

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283.

- Shikuma E, Endo Y, Fujisawa A, et al. Onychomadesis developed only on the nails having cutaneous lesions of severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:324193.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778.

- Grover C, Vohra S. Onychomadesis with lichen planus: an under-recognized manifestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:420.

- Chu DH, Rubin AI. Diagnosis and management of nail disorders. In: Holland K, ed. The Pediatric Clinics of North America. Vol 61. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:301-302.

- Kowalewski C, Schwartz RA. Components, growth, and composition of the nail. In: Demis D, ed. Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Scarfì F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1392-1394.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study [published online November 26, 2015]. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:802046.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Podder I, Das A, Gharami RC. Onychomadesis following varicella infection: is it a mere co-incidence? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:626-627.

- Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail abnormalities. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:31-37.

- Poretti A, Lips U, Belvedere M, et al. Onychomadesis: a rare side-effect of valproic acid medication? Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:749-750.

- Grech V, Vella C. Generalized onycholoysis associated with sodium valproate therapy. Eur Neurol. 1999;42:64-65.

- Shah RK, Uddin M, Fatunde OJ. Onychomadesis secondary to penicillin allergy in a child. J Pediatr. 2012;161:166.

- Haneke E. Onychomadesis and hand, foot and mouth disease—is there a connection? Euro Surveill. 2010;15(37).

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, et al. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728-730.

- Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Guerrero R, et al. Anatomical changes in retronychia and onychomadesis detected using ultrasound. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1615-1620.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Mishra D, Singh G, Pandey SS. Possible carbamazepine-induced reversible onychomadesis. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:460-461.

Practice Points

- Onychomadesis in a child may be a cutaneous sign of systemic disease.

- In childhood, onychomadesis is sometimes linked with hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

- Spontaneous nail regrowth usually occurs within 12 weeks but may occur faster in children.

Common Hair Disorders

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on common hair disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet reviews information about the most common hair disorders, including clinical and histopathological features, trichoscopy, and management of these diseases.

Practice Questions

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on common hair disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet reviews information about the most common hair disorders, including clinical and histopathological features, trichoscopy, and management of these diseases.

Practice Questions

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on common hair disorders with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet reviews information about the most common hair disorders, including clinical and histopathological features, trichoscopy, and management of these diseases.

Practice Questions

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. A 40-year-old woman presents to the clinic with a burning sensation and tenderness on the scalp. At physical examination you notice erythematous papules and pustules on the vertex scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. CCSA

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. traction alopecia

2. A 60-year-old woman presents with receding hair loss on the frontal and bitemporal scalp. She has noticed hair loss on her eyebrows. She has a history of oral ulcers. On physical examination there is mild erythema and perifollicular scales on the frontal hairline. A hair pull test is positive in this area. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. androgenetic alopecia

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. frontal fibrosing alopecia

d. telogen effluvium

e. trichotillomania

3. A 5-year-old girl with a history of seasonal allergies and eczema presents with recurrent patchy hair loss on the scalp of 6 months’ duration. Her mother has noticed rapidly progressive hair loss affecting the whole scalp. On trichoscopy, you find yellow dots, broken hairs, and tapering hairs. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. telogen effluvium

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

4. A 30-year-old white woman with history of obsessive-compulsive disorder presents to the clinic with hair loss for the last 3 years. She says she has noticed worsening of the hair loss when she is under stress. She also bites her nails. On physical examination you identify an irregular patch of alopecia with broken hairs on the occipital scalp. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. alopecia areata

b. androgenetic alopecia

c. lichen planopilaris

d. traction alopecia

e. trichotillomania

5. A 45-year-old black woman who has a family history of hair loss in her mother presents with tenderness and burning sensation on the vertex scalp. She reports the hair loss was worse after she got a hair relaxer 6 months prior. She uses braids on her scalp and she has not had a relaxer since then. The most likely diagnosis is:

a. CCSA

b. chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

c. folliculitis decalvans

d. lichen planopilaris

e. trichotillomania

Over-the-counter and Natural Remedies for Onychomycosis: Do They Really Work?

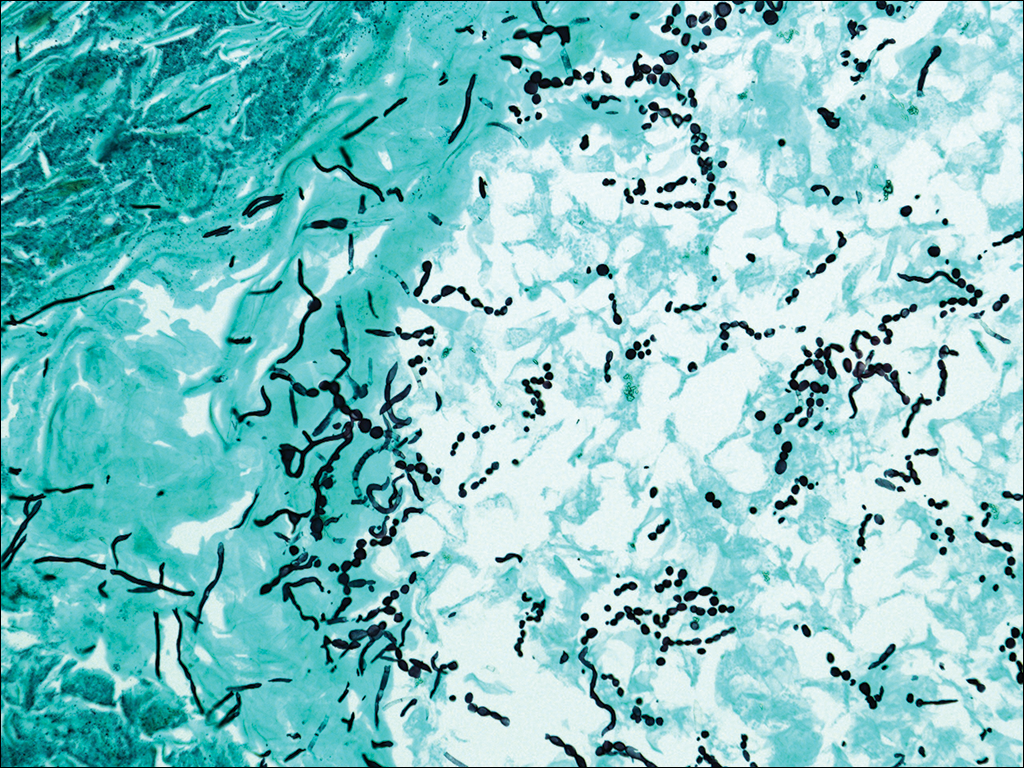

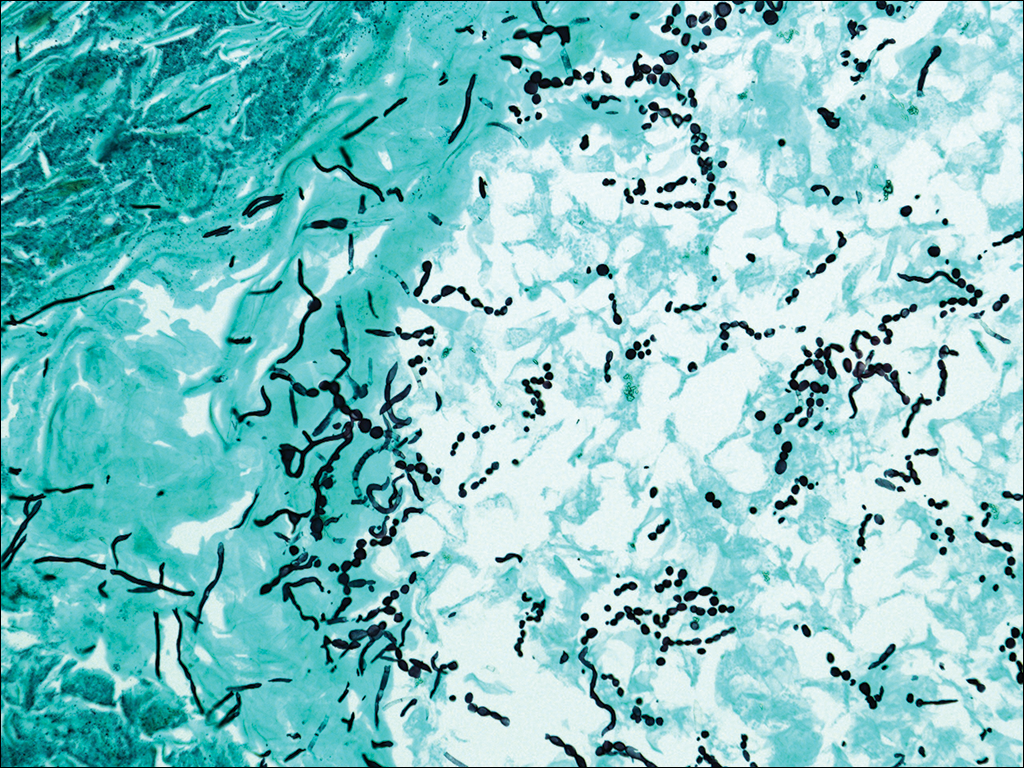

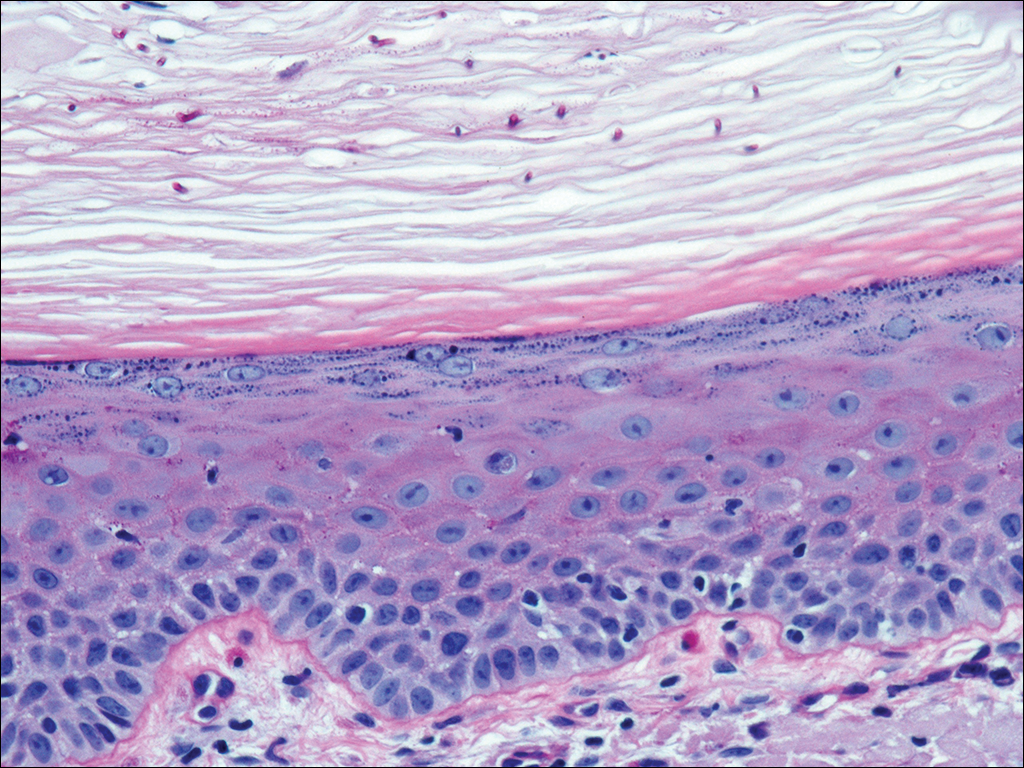

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail unit by dermatophytes, yeasts, and nondermatophyte molds. It is characterized by a white or yellow discoloration of the nail plate; hyperkeratosis of the nail bed; distal detachment of the nail plate from its bed (onycholysis); and nail plate dystrophy, including thickening, crumbling, and ridging. Onychomycosis is an important problem, representing 30% of all superficial fungal infections and an estimated 50% of all nail diseases.1 Reported prevalence rates of onychomycosis in the United States and worldwide are varied, but the mean prevalence based on population-based studies in Europe and North America is estimated to be 4.3%.2 It is more common in older individuals, with an incidence rate of 20% in those older than 60 years and 50% in those older than 70 years.3 Onychomycosis is more common in patients with diabetes and 1.9 to 2.8 times higher than the general population.4 Dermatophytes are responsible for the majority of cases of onychomycosis, particularly Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes.5

Onychomycosis is divided into different subtypes based on clinical presentation, which in turn are characterized by varying infecting organisms and prognoses. The subtypes of onychomycosis are distal and lateral subungual (DLSO), proximal subungual, superficial, endonyx, mixed pattern, total dystrophic, and secondary. Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis are by far the most common presentation and begins when the infecting organism invades the hyponychium and distal or lateral nail bed. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common organism and T mentagrophytes is second, but Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans also are possibilities. Proximal subungual onychomycosis is far less frequent than DLSO and is usually caused by T rubrum. The fungus invades the proximal nail folds and penetrates the newly growing nail plate.6 This pattern is more common in immunosuppressed patients and should prompt testing for human immunodeficiency virus.7 Total dystrophic onychomycosis is the end stage of fungal nail plate invasion, may follow DLSO or proximal subungual onychomycosis, and is difficult to treat.6

Onychomycosis causes pain, paresthesia, and difficulty with ambulation.8 In patients with peripheral neuropathy and vascular problems, including diabetes, onychomycosis can increase the risk for foot ulcers, with amputation in severe cases.9 Patients also may present with aesthetic concerns that may impact their quality of life.10

Given the effect on quality of life along with medical risks associated with onychomycosis, a safe and successful treatment modality with a low risk of recurrence is desirable. Unfortunately, treatment of nail fungus is quite challenging for a number of reasons. First, the thickness of the nail and/or the fungal mass may be a barrier to the delivery of topical and systemic drugs at the source of the infection. In addition, the nail plate does not have intrinsic immunity. Also, recurrence after treatment is common due to residual hyphae or spores that were not previously eliminated.11 Finally, many topical medications require long treatment courses, which may limit patient compliance, especially in patients who want to use nail polish for cosmesis or camouflage.

Currently Approved Therapies for Onychomycosis

Several definitions are needed to better interpret the results of onychomycosis clinical trials. Complete cure is defined as a negative potassium hydroxide preparation and negative fungal culture with a completely normal appearance of the nail. Mycological cure is defined as potassium hydroxide microscopy and fungal culture negative. Clinical cure is stated as 0% nail plate involvement but at times is reported as less than 5% and less than 10% involvement.

Terbinafine and itraconazole are the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved systemic therapies, and ciclopirox, efinaconazole, and tavaborole are the only FDA-approved topicals. Advantages of systemic agents generally are higher cure rates and shorter treatment courses, thus better compliance. Disadvantages include greater incidence of systemic side effects and drug-drug interactions as well as the need for laboratory monitoring. Pros of topical therapies are low potential for adverse effects, no drug-drug interactions, and no monitoring of blood work. Cons include lower efficacy, long treatment courses, and poor patient compliance.

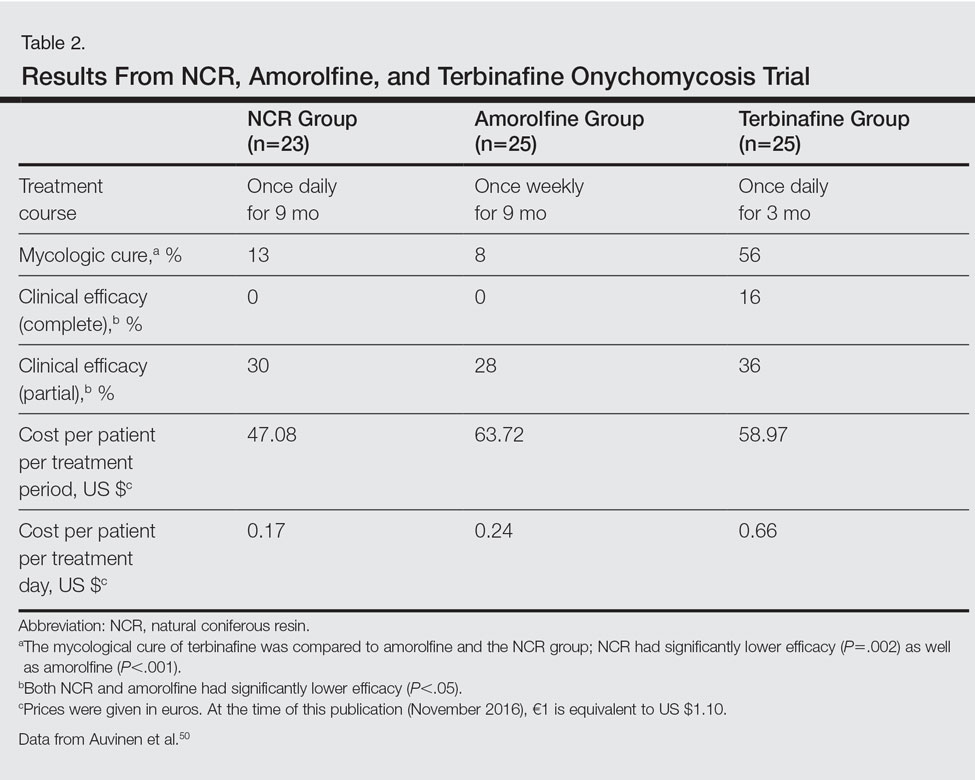

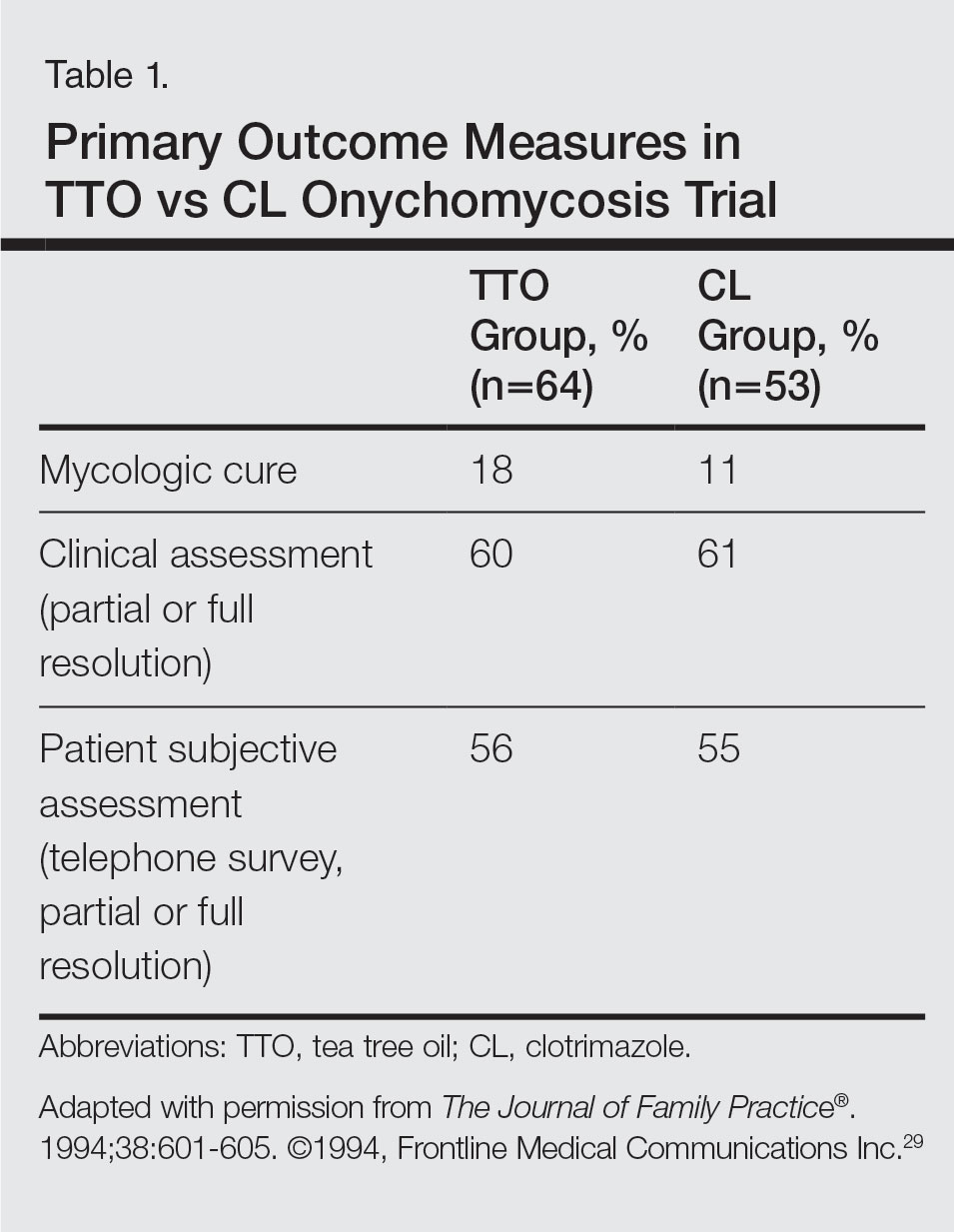

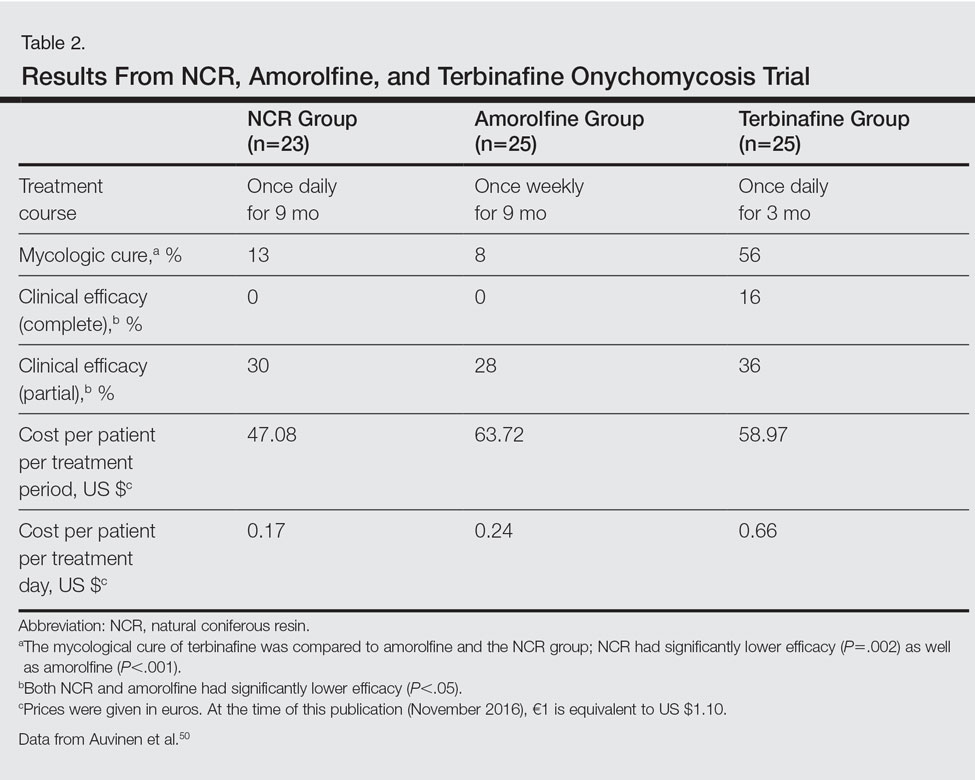

Terbinafine, an allylamine, taken orally once daily (250 mg) for 12 weeks for toenails and 6 weeks for fingernails currently is the preferred systemic treatment of onychomycosis, with complete cure rates of 38% and 59% and mycological cure rates of 70% and 79% for toenails and fingernails, respectively.12 Itraconazole, an azole, is dosed orally at 200 mg daily for 3 months for toenails, with a complete cure rate of 14% and mycological cure rate of 54%.13 For fingernail onychomycosis only, itraconazole is dosed at 200 mg twice daily for 1 week, followed by a treatment-free period of 3 weeks, and then another 1-week course at thesame dose. The complete cure rate is 47% and the mycological cure is 61% for this pulse regimen.13

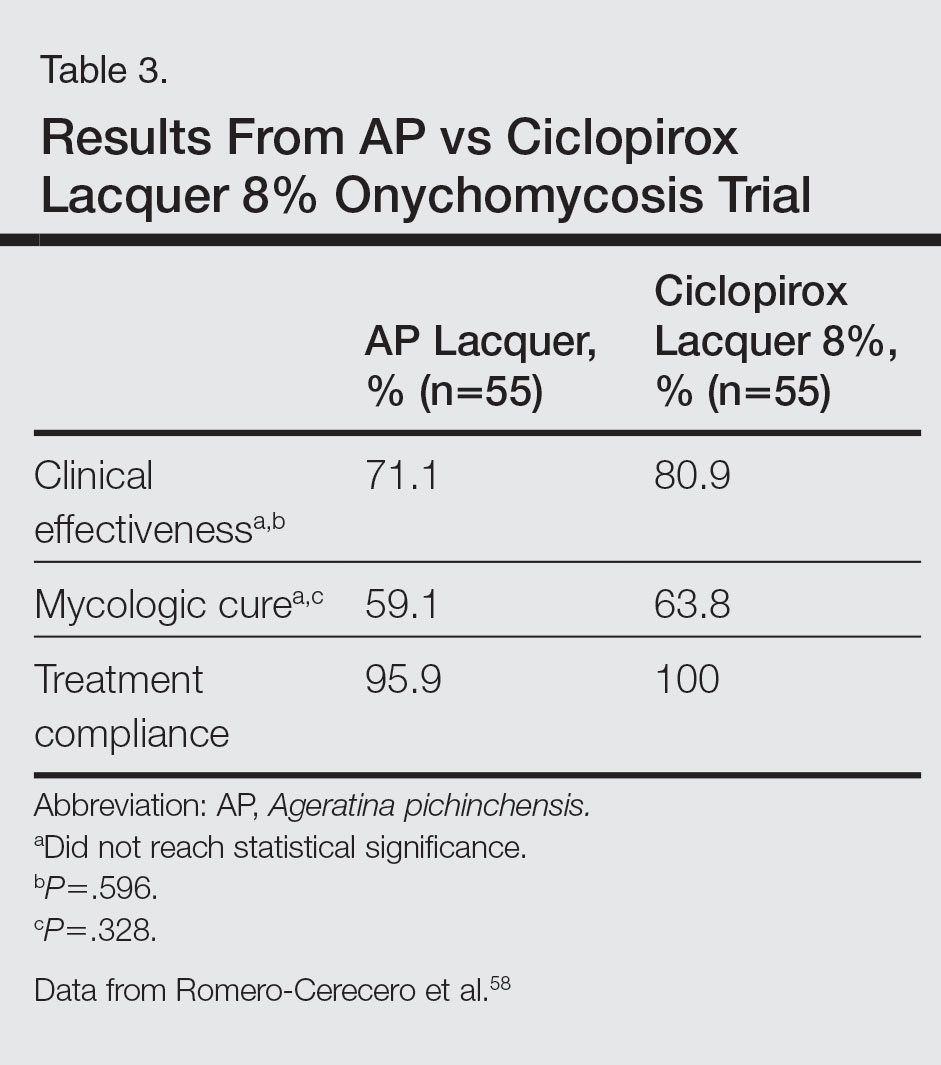

Ciclopirox is a hydroxypyridone and the 8% nail lacquer formulation was approved in 1999, making it the first topical medication to gain FDA approval for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis. Based on 2 clinical trials, complete cure rates for toenails are 5.5% and 8.5% and mycological cure rates are 29% and 36% at 48 weeks with removal of residual lacquer and debridement.14 Efinaconazole is an azole and the 10% solution was FDA approved for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in 2014.15 In 2 clinical trials, complete cure rates were 17.8% and 15.2% and mycological cure rates were 55.2% and 53.4% with once daily toenail application for 48 weeks.16 Tavaborole is a benzoxaborole and the 5% solution also was approved for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in 2014.17 Two clinical trials reported complete cure rates of 6.5% and 9.1% and mycological cure rates of 31.1% and 35.9% with once daily toenail application for 48 weeks.18

Given the poor efficacy, systemic side effects, potential for drug-drug interactions, long-term treatment courses, and cost associated with current systemic and/or topical treatments, there has been a renewed interest in natural remedies and over-the-counter (OTC) therapies for onychomycosis. This review summarizes the in vitro and in vivo data, mechanisms of action, and clinical efficacy of various natural and OTC agents for the treatment of onychomycosis. Specifically, we summarize the data on tea tree oil (TTO), a popular topical cough suppressant (TCS), natural coniferous resin (NCR) lacquer, Ageratina pichinchensis (AP) extract, and ozonized sunflower oil.

Tea Tree Oil

Background

Tea tree oil is a volatile oil whose medicinal use dates back to the early 20th century when the Bundjabung aborigines of North and New South Wales extracted TTO from the dried leaves of the Melaleuca alternifolia plant and used it to treat superficial wounds.19 Tea tree oil has been shown to be an effective treatment of tinea pedis,20 and it is widely used in Australia as well as in Europe and North America.21 Tea tree oil also has been investigated as an antifungal agent for the treatment of onychomycosis, both in vitro22-28 and in clinical trials.29,30

In Vitro Data

Because TTO is composed of more than 100 active components,23 the antifungal activity of these individual components was investigated against 14 fungal isolates, including C albicans, T mentagrophytes, and Aspergillus species. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for α-pinene was less than 0.004% for T mentagrophytes and the components with the greatest MIC and minimum fungicidal concentration for the fungi tested were terpinen-4-ol and α-terpineol, respectively.22 The antifungal activity of TTO also was tested using disk diffusion assay experiments with 58 clinical isolates of fungi including C albicans, T rubrum, T mentagrophytes, and Aspergillus niger.24 Tea tree oil was most effective at inhibiting T rubrum followed by T mentagrophytes,24 which are the 2 most common etiologies of onychomycosis.5 In another report, the authors determined the MIC of TTO utilizing 4 different experiments with T rubrum as the infecting organism. Because TTO inhibited the growth of T rubrum at all concentrations greater than 0.1%, they found that the MIC was 0.1%.25 Given the lack of adequate nail penetration of most topical therapies, TTO in nanocapsules (TTO-NC), TTO nanoemulsions, and normal emulsions were tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit the growth of T rubrum inoculated into nail shavings. Colony growth decreased significantly within the first week of treatment, with TTO-NC showing maximum efficacy (P<.001). This study showed that TTO, particularly TTO-NC, was effective in inhibiting the growth of T rubrum in vitro and that using nanocapsule technology may increase nail penetration and bioavailability.31

Much of what we know about TTO’s antifungal mechanism of action comes from experiments involving C albicans. To date, it has not been studied in T rubrum or T mentagrophytes, the 2 most common etiologies of onychomycosis.5 In C albicans, TTO causes altered permeability of plasma membranes,32 dose-dependent alteration of respiration,33 decreased glucose-induced acidification of media surrounding fungi,32 and reversible inhibition of germ tube formation.19,34

Clinical Trials