User login

Inpatient care for HS higher for Black and Hispanic patients

National Inpatient Sample.

The differences occurred despite Black and Hispanic patients being younger at the time of admission than White patients, and may reflect increased disease severity and management challenges in these patients with skin of color, Nishadh Sutaria, BS, a medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium. “They may also reflect social inequities in access to dermatologists, with racial and ethnic minorities using inpatient services in lieu of outpatient care.”

Mr. Sutaria and coinvestigators, led by Shawn Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, identified 8,040 HS admissions for White patients, 16,490 Black patients, and 2,405 for Hispanic patients during the 5-year period.

Black and Hispanic patients were significantly younger than White patients, with a mean age of 38.1 years and 35 years, respectively, compared with 42 years for White patients (P < .001 in each case). Compared with White patients, Black patients had more procedures (2.03 vs. 1.84, P = .006), a longer length of stay (5.82 days vs. 4.97 days, P = .001), and higher cost of care ($46,119 vs. $39,862, P = .010). Compared with White patients, Hispanic patients had higher cost of care ($52,334 vs. $39,862, P = .004).

“In these models, Black patients stayed almost a full day longer and accrued a charge of $8,000 more than White patients, and Hispanic patients stayed about a half-day longer and accrued a charge of almost $15,000 more than White patients,” Mr. Sutaria said.

In a multilinear regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and insurance type, Black race correlated with more procedures, higher length of stay, and higher cost of care, and Hispanic ethnicity with more procedures and higher cost of care.

Prior research has shown that Black patients may be disproportionately affected by HS. A 2017 analysis of electronic health record data for tens of millions of patients nationally, for instance, showed an incidence of HS that was over 2.5 times greater in Blacks than Whites. And a recent analysis of electronic data in Wisconsin for patients with an HS diagnosis and 3 or more encounters for the disease showed that Blacks are more likely to have HS that is Hurley Stage 3, the most severe type.

Increased severity “has not been explicitly shown in Hispanic patients,” Dr. Kwatra said in an interview, “[but] there is a strong relationship between obesity/metabolic syndrome with HS. Because Hispanic patients have higher rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it’s [thought] that they may have more severe HS.”

HS patients with skin of color are underrepresented in clinical trials, he said. “Severe HS can be difficult to treat because there are few effective treatments,” he said, noting that adalimumab is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy.

The National Inpatient Sample is a publicly available, all-payer inpatient care database developed for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Mr. Sutaria is a dermatology research fellow working under the guidance of Dr. Kwatra.

National Inpatient Sample.

The differences occurred despite Black and Hispanic patients being younger at the time of admission than White patients, and may reflect increased disease severity and management challenges in these patients with skin of color, Nishadh Sutaria, BS, a medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium. “They may also reflect social inequities in access to dermatologists, with racial and ethnic minorities using inpatient services in lieu of outpatient care.”

Mr. Sutaria and coinvestigators, led by Shawn Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, identified 8,040 HS admissions for White patients, 16,490 Black patients, and 2,405 for Hispanic patients during the 5-year period.

Black and Hispanic patients were significantly younger than White patients, with a mean age of 38.1 years and 35 years, respectively, compared with 42 years for White patients (P < .001 in each case). Compared with White patients, Black patients had more procedures (2.03 vs. 1.84, P = .006), a longer length of stay (5.82 days vs. 4.97 days, P = .001), and higher cost of care ($46,119 vs. $39,862, P = .010). Compared with White patients, Hispanic patients had higher cost of care ($52,334 vs. $39,862, P = .004).

“In these models, Black patients stayed almost a full day longer and accrued a charge of $8,000 more than White patients, and Hispanic patients stayed about a half-day longer and accrued a charge of almost $15,000 more than White patients,” Mr. Sutaria said.

In a multilinear regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and insurance type, Black race correlated with more procedures, higher length of stay, and higher cost of care, and Hispanic ethnicity with more procedures and higher cost of care.

Prior research has shown that Black patients may be disproportionately affected by HS. A 2017 analysis of electronic health record data for tens of millions of patients nationally, for instance, showed an incidence of HS that was over 2.5 times greater in Blacks than Whites. And a recent analysis of electronic data in Wisconsin for patients with an HS diagnosis and 3 or more encounters for the disease showed that Blacks are more likely to have HS that is Hurley Stage 3, the most severe type.

Increased severity “has not been explicitly shown in Hispanic patients,” Dr. Kwatra said in an interview, “[but] there is a strong relationship between obesity/metabolic syndrome with HS. Because Hispanic patients have higher rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it’s [thought] that they may have more severe HS.”

HS patients with skin of color are underrepresented in clinical trials, he said. “Severe HS can be difficult to treat because there are few effective treatments,” he said, noting that adalimumab is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy.

The National Inpatient Sample is a publicly available, all-payer inpatient care database developed for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Mr. Sutaria is a dermatology research fellow working under the guidance of Dr. Kwatra.

National Inpatient Sample.

The differences occurred despite Black and Hispanic patients being younger at the time of admission than White patients, and may reflect increased disease severity and management challenges in these patients with skin of color, Nishadh Sutaria, BS, a medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium. “They may also reflect social inequities in access to dermatologists, with racial and ethnic minorities using inpatient services in lieu of outpatient care.”

Mr. Sutaria and coinvestigators, led by Shawn Kwatra, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, identified 8,040 HS admissions for White patients, 16,490 Black patients, and 2,405 for Hispanic patients during the 5-year period.

Black and Hispanic patients were significantly younger than White patients, with a mean age of 38.1 years and 35 years, respectively, compared with 42 years for White patients (P < .001 in each case). Compared with White patients, Black patients had more procedures (2.03 vs. 1.84, P = .006), a longer length of stay (5.82 days vs. 4.97 days, P = .001), and higher cost of care ($46,119 vs. $39,862, P = .010). Compared with White patients, Hispanic patients had higher cost of care ($52,334 vs. $39,862, P = .004).

“In these models, Black patients stayed almost a full day longer and accrued a charge of $8,000 more than White patients, and Hispanic patients stayed about a half-day longer and accrued a charge of almost $15,000 more than White patients,” Mr. Sutaria said.

In a multilinear regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and insurance type, Black race correlated with more procedures, higher length of stay, and higher cost of care, and Hispanic ethnicity with more procedures and higher cost of care.

Prior research has shown that Black patients may be disproportionately affected by HS. A 2017 analysis of electronic health record data for tens of millions of patients nationally, for instance, showed an incidence of HS that was over 2.5 times greater in Blacks than Whites. And a recent analysis of electronic data in Wisconsin for patients with an HS diagnosis and 3 or more encounters for the disease showed that Blacks are more likely to have HS that is Hurley Stage 3, the most severe type.

Increased severity “has not been explicitly shown in Hispanic patients,” Dr. Kwatra said in an interview, “[but] there is a strong relationship between obesity/metabolic syndrome with HS. Because Hispanic patients have higher rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome, it’s [thought] that they may have more severe HS.”

HS patients with skin of color are underrepresented in clinical trials, he said. “Severe HS can be difficult to treat because there are few effective treatments,” he said, noting that adalimumab is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy.

The National Inpatient Sample is a publicly available, all-payer inpatient care database developed for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Mr. Sutaria is a dermatology research fellow working under the guidance of Dr. Kwatra.

FROM SOC SOCIETY 2021

Atopic Dermatitis

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

Revised dispatch system boosts bystander CPR in those with limited English

The improved Los Angeles medical dispatch system prompted more callers with limited English proficiency to initiate telecommunicator-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (T-CPR), compared with the previous system, a new study shows.

The Los Angeles Tiered Dispatch System (LA-TDS), adopted in late 2014, used simplified questions aimed at identifying cardiac arrest, compared with the city’s earlier Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS).

The result was substantially decreased call processing times, decreased “undertriage” of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), and improved overall T-CPR rates (Resuscitation. 2020 Oct;155:74-81).

But now, a secondary analysis of the data shows there was a much higher jump in T-CPR rates among a small subset of callers with limited English proficiency, compared with those proficient in English (JAMA Network Open. 2021;4[6]:e216827).

“This was an unanticipated, significant, and disproportionate change, but fortunately a very good change,” lead author Stephen Sanko, MD, said in an interview.

While the T-CPR rate among English-proficient callers increased from 55% with the MPDS to 67% with the LA-TDS (odds ratio, 1.66; P = .007), it rose from 28% to 69% (OR, 5.66; P = .003) among callers with limited English proficiency. In the adjusted analysis, the new LA-TDS was associated with a 69% higher prevalence of T-CPR among English-proficient callers, compared with a 350% greater prevalence among callers with limited English proficiency.

“The emergency communication process between a caller and 911 telecommunicator is more complex than we thought, and likely constitutes a unique subsubspecialty that interacts with fields as diverse as medicine, health equity, linguistics, sociology, consumer behavior and others,” said Dr. Sanko, who is from the division of emergency medical services at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

“Yet in spite of this complexity, we’re starting to be able to reproducibly classify elements of the emergency conversation that we believe are tied to outcomes we all care about. ... Modulators of health disparities are present as early as the dispatch conversation, and, importantly, they can be intervened upon to promote improved outcomes,” he continued.

The retrospective cohort study was a predefined secondary analysis of a previously published study comparing telecommunicator management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest over 3 months with the MPDS versus 3 months with the LA-TDS. The primary outcome was the number of patients who received telecommunicator-assisted chest compressions from callers with limited English proficiency.

Of the 597 emergency calls that met the inclusion criteria, 289 (48%) were in the MPDS cohort and 308 (52%) were in the LA-TDS cohort. In the MPDS cohort, 263 callers had English proficiency and 26 had limited proficiency; in the latter cohort, those figures were 273 and 35, respectively.

There were no significant differences between cohorts in the use of real-time translation services, which were employed 27%-31% of the time.

The reason for the overall T-CPR improvement is likely that the LA-TDS was tailored to the community needs, said Dr. Sanko. “Most people, including doctors, think of 911 dispatch as something simple and straightforward, like ordering a pizza or calling a ride share. [But] LA-TDS is a ‘home grown’ dispatch system whose structure, questions, and emergency instructions were all developed by EMS medical directors and telecommunicators with extensive experience in our community.”

That being said, the researchers acknowledge that the reason behind the bigger T-CPR boost in LEP callers remains unclear. Although the link between language and system was statistically significant, they noted “it was not an a priori hypothesis and appeared to be largely attributable to the low T-CPR rates for callers with limited English proficiency using MPDS.” Additionally, such callers were “remarkably under-represented” in the sample, “which included approximately 600 calls over two quarters in a large city,” said Dr Sanko.

“We hypothesize that a more direct structure, earlier commitment to treating patients with abnormal life status indicators as being suspected cardiac arrest cases, and earlier reassurance may have improved caller confidence that telecommunicators knew what they were doing. This in turn may have translated into an increased likelihood of bystander caller willingness to perform immediate life-saving maneuvers.”

Despite a number of limitations, “the study is important and highlights instructive topics for discussion that suggest potential next-step opportunities,” noted Richard Chocron, MD, PhD, Miranda Lewis, MD, and Thomas Rea, MD, MPH, in an invited commentary that accompanied the publication. Dr. Chocron is from the Paris University, Paris Research Cardiovascular Center, INSERM; Dr. Lewis is from the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in Paris; and Dr. Rea is from the Division of Emergency Medical Services, Public Health–Seattle & King County. Both Dr. Lewis and Dr. Rea are also at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“Sanko et al. found that approximately 10% of all emergency calls were classified as limited English proficiency calls in a community in which 19% of the population was considered to have limited English proficiency,” they added. “This finding suggests the possibility that populations with limited English proficiency are less likely to activate 911 for incidence of cardiac arrest. If true, this finding would compound the health disparity observed among those with limited English proficiency. This topic is important in that it transcends the role of EMS personnel and engages a broad spectrum of societal stakeholders. We must listen, learn, and ultimately deliver public safety resources to groups who have not been well served by conventional approaches.”

None of the authors or editorialists reported any conflicts of interest.

The improved Los Angeles medical dispatch system prompted more callers with limited English proficiency to initiate telecommunicator-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (T-CPR), compared with the previous system, a new study shows.

The Los Angeles Tiered Dispatch System (LA-TDS), adopted in late 2014, used simplified questions aimed at identifying cardiac arrest, compared with the city’s earlier Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS).

The result was substantially decreased call processing times, decreased “undertriage” of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), and improved overall T-CPR rates (Resuscitation. 2020 Oct;155:74-81).

But now, a secondary analysis of the data shows there was a much higher jump in T-CPR rates among a small subset of callers with limited English proficiency, compared with those proficient in English (JAMA Network Open. 2021;4[6]:e216827).

“This was an unanticipated, significant, and disproportionate change, but fortunately a very good change,” lead author Stephen Sanko, MD, said in an interview.

While the T-CPR rate among English-proficient callers increased from 55% with the MPDS to 67% with the LA-TDS (odds ratio, 1.66; P = .007), it rose from 28% to 69% (OR, 5.66; P = .003) among callers with limited English proficiency. In the adjusted analysis, the new LA-TDS was associated with a 69% higher prevalence of T-CPR among English-proficient callers, compared with a 350% greater prevalence among callers with limited English proficiency.

“The emergency communication process between a caller and 911 telecommunicator is more complex than we thought, and likely constitutes a unique subsubspecialty that interacts with fields as diverse as medicine, health equity, linguistics, sociology, consumer behavior and others,” said Dr. Sanko, who is from the division of emergency medical services at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

“Yet in spite of this complexity, we’re starting to be able to reproducibly classify elements of the emergency conversation that we believe are tied to outcomes we all care about. ... Modulators of health disparities are present as early as the dispatch conversation, and, importantly, they can be intervened upon to promote improved outcomes,” he continued.

The retrospective cohort study was a predefined secondary analysis of a previously published study comparing telecommunicator management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest over 3 months with the MPDS versus 3 months with the LA-TDS. The primary outcome was the number of patients who received telecommunicator-assisted chest compressions from callers with limited English proficiency.

Of the 597 emergency calls that met the inclusion criteria, 289 (48%) were in the MPDS cohort and 308 (52%) were in the LA-TDS cohort. In the MPDS cohort, 263 callers had English proficiency and 26 had limited proficiency; in the latter cohort, those figures were 273 and 35, respectively.

There were no significant differences between cohorts in the use of real-time translation services, which were employed 27%-31% of the time.

The reason for the overall T-CPR improvement is likely that the LA-TDS was tailored to the community needs, said Dr. Sanko. “Most people, including doctors, think of 911 dispatch as something simple and straightforward, like ordering a pizza or calling a ride share. [But] LA-TDS is a ‘home grown’ dispatch system whose structure, questions, and emergency instructions were all developed by EMS medical directors and telecommunicators with extensive experience in our community.”

That being said, the researchers acknowledge that the reason behind the bigger T-CPR boost in LEP callers remains unclear. Although the link between language and system was statistically significant, they noted “it was not an a priori hypothesis and appeared to be largely attributable to the low T-CPR rates for callers with limited English proficiency using MPDS.” Additionally, such callers were “remarkably under-represented” in the sample, “which included approximately 600 calls over two quarters in a large city,” said Dr Sanko.

“We hypothesize that a more direct structure, earlier commitment to treating patients with abnormal life status indicators as being suspected cardiac arrest cases, and earlier reassurance may have improved caller confidence that telecommunicators knew what they were doing. This in turn may have translated into an increased likelihood of bystander caller willingness to perform immediate life-saving maneuvers.”

Despite a number of limitations, “the study is important and highlights instructive topics for discussion that suggest potential next-step opportunities,” noted Richard Chocron, MD, PhD, Miranda Lewis, MD, and Thomas Rea, MD, MPH, in an invited commentary that accompanied the publication. Dr. Chocron is from the Paris University, Paris Research Cardiovascular Center, INSERM; Dr. Lewis is from the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in Paris; and Dr. Rea is from the Division of Emergency Medical Services, Public Health–Seattle & King County. Both Dr. Lewis and Dr. Rea are also at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“Sanko et al. found that approximately 10% of all emergency calls were classified as limited English proficiency calls in a community in which 19% of the population was considered to have limited English proficiency,” they added. “This finding suggests the possibility that populations with limited English proficiency are less likely to activate 911 for incidence of cardiac arrest. If true, this finding would compound the health disparity observed among those with limited English proficiency. This topic is important in that it transcends the role of EMS personnel and engages a broad spectrum of societal stakeholders. We must listen, learn, and ultimately deliver public safety resources to groups who have not been well served by conventional approaches.”

None of the authors or editorialists reported any conflicts of interest.

The improved Los Angeles medical dispatch system prompted more callers with limited English proficiency to initiate telecommunicator-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (T-CPR), compared with the previous system, a new study shows.

The Los Angeles Tiered Dispatch System (LA-TDS), adopted in late 2014, used simplified questions aimed at identifying cardiac arrest, compared with the city’s earlier Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS).

The result was substantially decreased call processing times, decreased “undertriage” of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), and improved overall T-CPR rates (Resuscitation. 2020 Oct;155:74-81).

But now, a secondary analysis of the data shows there was a much higher jump in T-CPR rates among a small subset of callers with limited English proficiency, compared with those proficient in English (JAMA Network Open. 2021;4[6]:e216827).

“This was an unanticipated, significant, and disproportionate change, but fortunately a very good change,” lead author Stephen Sanko, MD, said in an interview.

While the T-CPR rate among English-proficient callers increased from 55% with the MPDS to 67% with the LA-TDS (odds ratio, 1.66; P = .007), it rose from 28% to 69% (OR, 5.66; P = .003) among callers with limited English proficiency. In the adjusted analysis, the new LA-TDS was associated with a 69% higher prevalence of T-CPR among English-proficient callers, compared with a 350% greater prevalence among callers with limited English proficiency.

“The emergency communication process between a caller and 911 telecommunicator is more complex than we thought, and likely constitutes a unique subsubspecialty that interacts with fields as diverse as medicine, health equity, linguistics, sociology, consumer behavior and others,” said Dr. Sanko, who is from the division of emergency medical services at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

“Yet in spite of this complexity, we’re starting to be able to reproducibly classify elements of the emergency conversation that we believe are tied to outcomes we all care about. ... Modulators of health disparities are present as early as the dispatch conversation, and, importantly, they can be intervened upon to promote improved outcomes,” he continued.

The retrospective cohort study was a predefined secondary analysis of a previously published study comparing telecommunicator management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest over 3 months with the MPDS versus 3 months with the LA-TDS. The primary outcome was the number of patients who received telecommunicator-assisted chest compressions from callers with limited English proficiency.

Of the 597 emergency calls that met the inclusion criteria, 289 (48%) were in the MPDS cohort and 308 (52%) were in the LA-TDS cohort. In the MPDS cohort, 263 callers had English proficiency and 26 had limited proficiency; in the latter cohort, those figures were 273 and 35, respectively.

There were no significant differences between cohorts in the use of real-time translation services, which were employed 27%-31% of the time.

The reason for the overall T-CPR improvement is likely that the LA-TDS was tailored to the community needs, said Dr. Sanko. “Most people, including doctors, think of 911 dispatch as something simple and straightforward, like ordering a pizza or calling a ride share. [But] LA-TDS is a ‘home grown’ dispatch system whose structure, questions, and emergency instructions were all developed by EMS medical directors and telecommunicators with extensive experience in our community.”

That being said, the researchers acknowledge that the reason behind the bigger T-CPR boost in LEP callers remains unclear. Although the link between language and system was statistically significant, they noted “it was not an a priori hypothesis and appeared to be largely attributable to the low T-CPR rates for callers with limited English proficiency using MPDS.” Additionally, such callers were “remarkably under-represented” in the sample, “which included approximately 600 calls over two quarters in a large city,” said Dr Sanko.

“We hypothesize that a more direct structure, earlier commitment to treating patients with abnormal life status indicators as being suspected cardiac arrest cases, and earlier reassurance may have improved caller confidence that telecommunicators knew what they were doing. This in turn may have translated into an increased likelihood of bystander caller willingness to perform immediate life-saving maneuvers.”

Despite a number of limitations, “the study is important and highlights instructive topics for discussion that suggest potential next-step opportunities,” noted Richard Chocron, MD, PhD, Miranda Lewis, MD, and Thomas Rea, MD, MPH, in an invited commentary that accompanied the publication. Dr. Chocron is from the Paris University, Paris Research Cardiovascular Center, INSERM; Dr. Lewis is from the Georges Pompidou European Hospital in Paris; and Dr. Rea is from the Division of Emergency Medical Services, Public Health–Seattle & King County. Both Dr. Lewis and Dr. Rea are also at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“Sanko et al. found that approximately 10% of all emergency calls were classified as limited English proficiency calls in a community in which 19% of the population was considered to have limited English proficiency,” they added. “This finding suggests the possibility that populations with limited English proficiency are less likely to activate 911 for incidence of cardiac arrest. If true, this finding would compound the health disparity observed among those with limited English proficiency. This topic is important in that it transcends the role of EMS personnel and engages a broad spectrum of societal stakeholders. We must listen, learn, and ultimately deliver public safety resources to groups who have not been well served by conventional approaches.”

None of the authors or editorialists reported any conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Improving racial and gender equity in pediatric HM programs

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Relationship-Centered Care in the Physician-Patient Interaction: Improving Your Understanding of Metacognitive Interventions

Communication and relationships cannot be taken for granted, particularly in the physician-patient relationship, where life-altering diagnoses may be given. With one diagnosis, someone’s life may be changed, and both physicians and patients need to be cognizant of the importance of a strong relationship and clear communication.

In the current US health care system, both physicians and patients often are not getting their needs met, and studies that include factors of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status suggest that physician-patient relationship barriers contribute to racial disparities in health care.1,2 Although patient-centered care is a widely recognized and upheld model, relationship-centered care between physician and patient involves focusing on the patient and the physician-patient relationship through recognizing personhood, affect (being empathic), and reciprocal influence.3,4 Although it is not necessarily intuitive because it can appear to be yet another task for busy physicians, relationship-centered care improves health care delivery for both physicians and patients through decreased physician burnout, reduced medical errors, and better patient outcomes and satisfaction.5,6

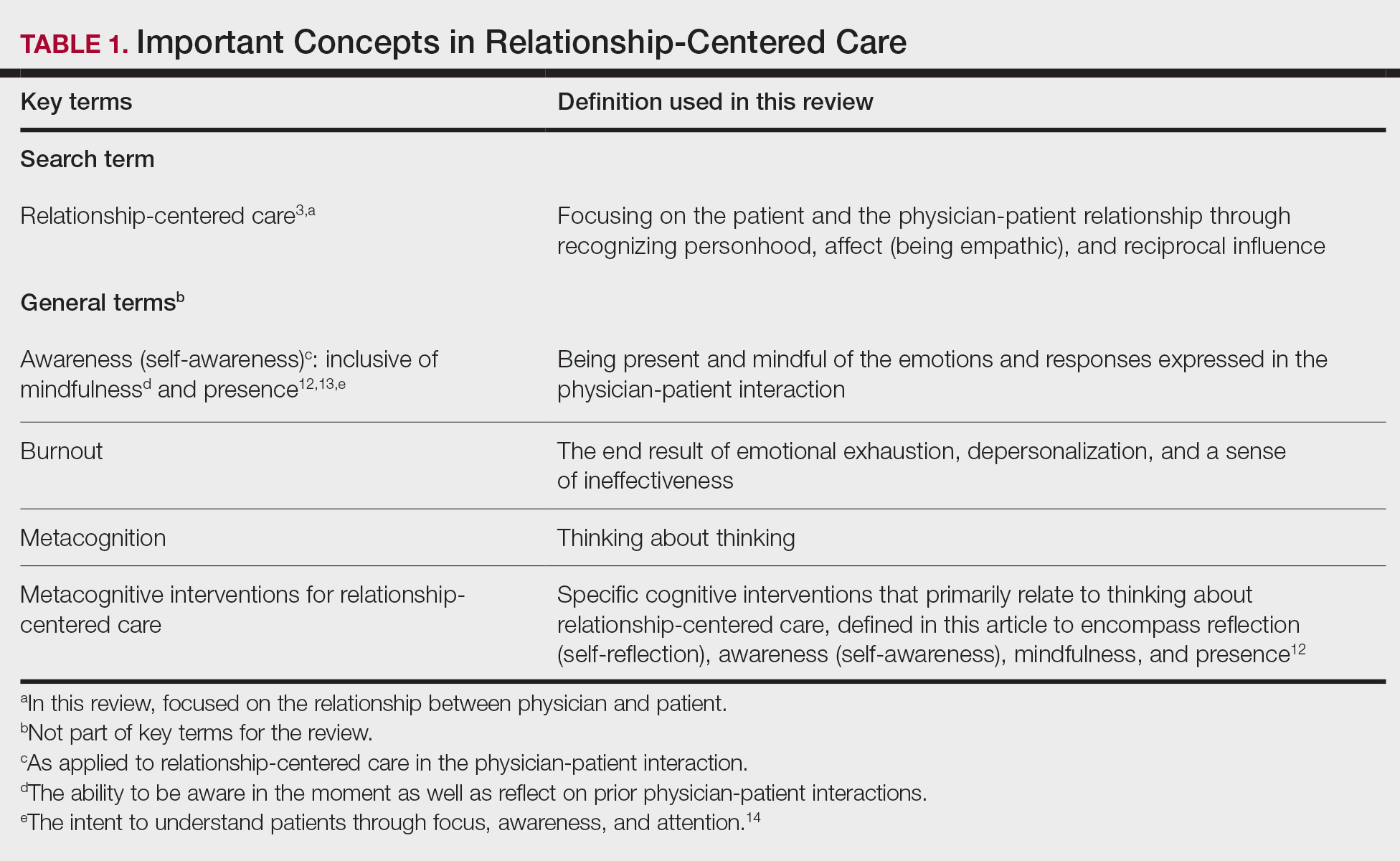

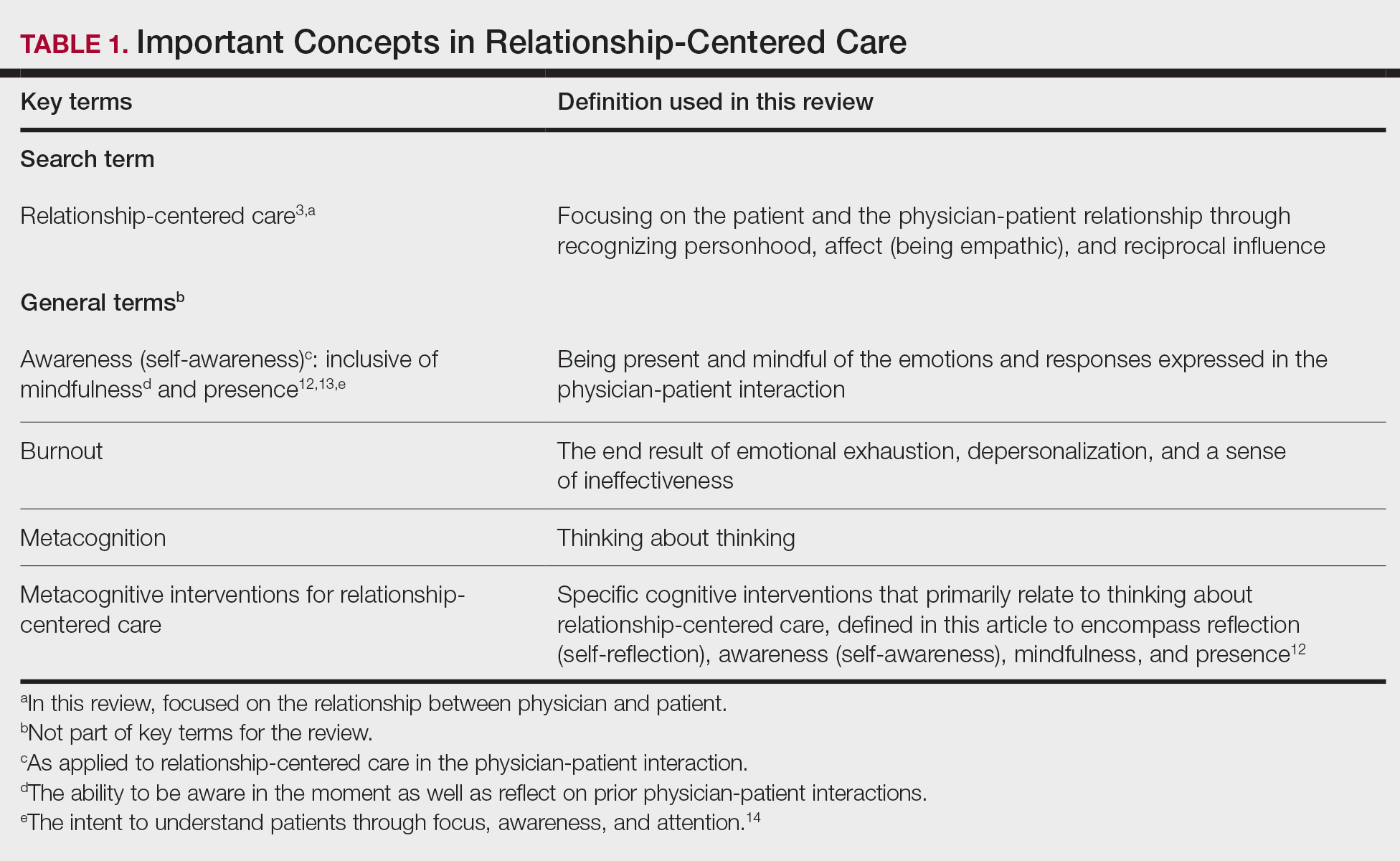

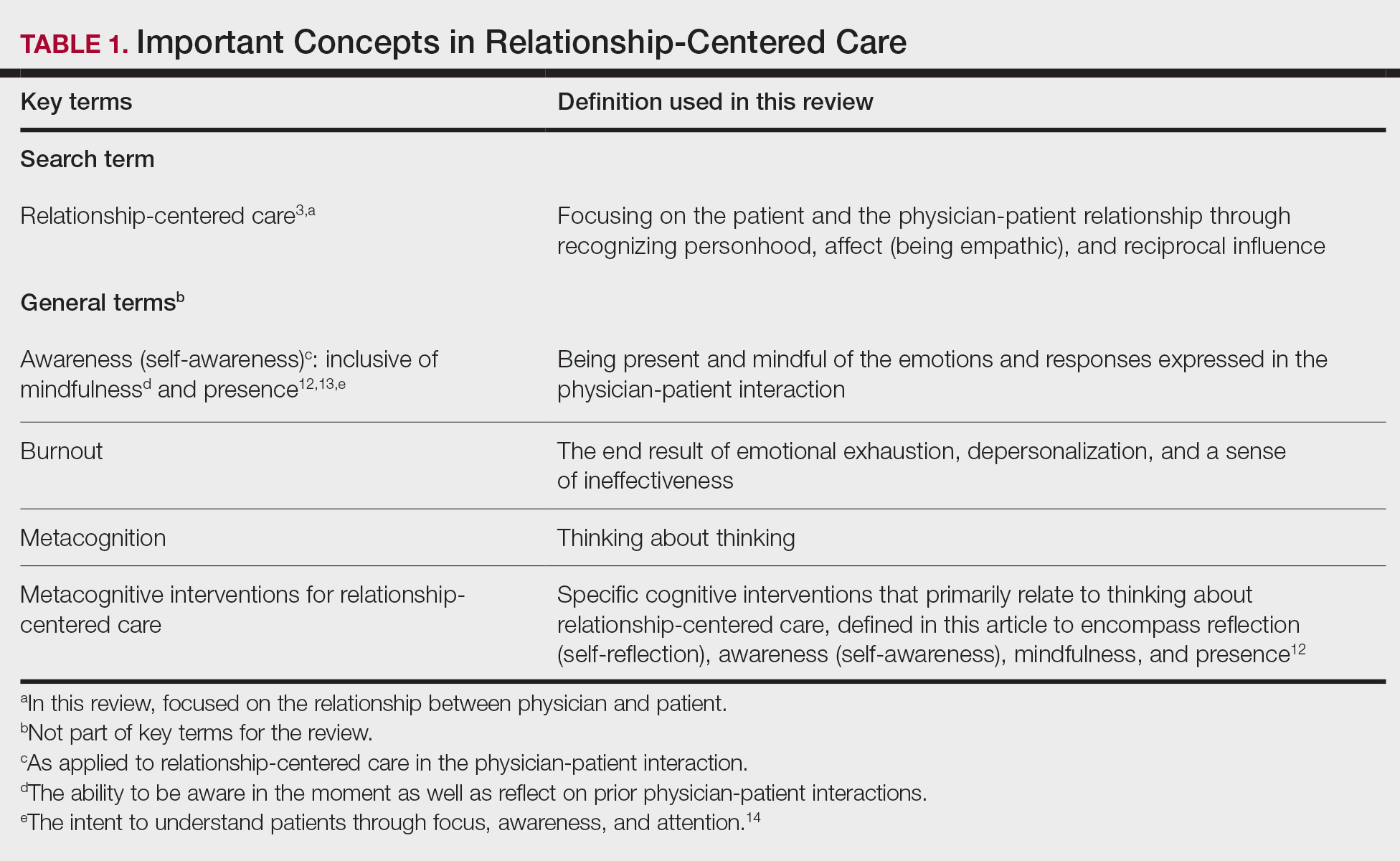

Every physician, patient, and physician-patient relationship is different; unlike the standard questions directed at a routine patient history focused on gathering data, there is no one-size-fits-all relationship-centered conversation.7-10 As with any successful interaction between 2 people, there is a certain amount of necessary self-awareness (Table 1)11 that allows for improvisation and appropriate responsiveness to what is seen, heard, and felt. Rather than attending solely to disease states, the focus of relationship-centered care is on patients, interpersonal interaction, and promoting health and well-being.15

This review summarizes the existing literature on relationship-centered care, introduces the use of metacognition (Table 1), and suggests creating simple habits to promote such care. The following databases were searched from inception through November 23, 2020, using the term relationship-centered care: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Academic Search Premier (EBSCOhost), and ERIC (ProQuest). A total of 1772 records were retrieved through searches, and after deduplication of 1116 studies, 350 records were screened through a 2-part process. Articles were first screened by title and abstract for relevance to the relationship between physician and patient, with 185 studies deemed irrelevant (eg, pertaining to the relationship of veterinarian to animal). The remaining 165 studies were assessed for eligibility, with 69 further studies excluded for various reasons. The screening process resulted in 96 articles considered in this review.

Definitions/key terms, as used in this article, are listed in Table 1.

Background of Relationship-Centered Care

Given time constraints, the diagnosis and treatment of medical problems often are the focus of physicians. Although proper medical diagnosis and treatment are important, and their delivery is made possible by the physician having the appropriate knowledge, a physician-patient relationship that focuses solely on disease without acknowledging the patient creates a system that ultimately neglects both patients and physicians.15 This prevailing physician-patient relationship paradigm is suboptimal, and a proposed remedy is relationship-centered care, which focuses on relationships among the human beings in health care interactions.3 Relationship-centered care has 4 principles: (1) the personhood of each party must be recognized, (2) emotion is part of relationships, (3) relationships are reciprocal and not just one way, and (4) creating these types of relationships is morally valuable3 and beneficial to patient care.16

Assessment of the Need for Relationship-Centered Care

Relationship-centered care has been studied in physician-patient interactions in various health care settings.17-23 For at least 2 decades, relationship-centered care has been set forth as a model,4,24,25 but there are challenges. Physicians tend to overrate or underrate their communication skills in patient interactions.26,27 A given physician’s preferences often still seem to supersede those of the patient.3,28,29 The impetus to develop relationship-centered care skills generally needs to be internally driven,4,30 as, ultimately, physicians and patients have varying needs.4,31 However, providing physicians with a potential structure is helpful.32

A Solution: Metacognition in the Physician-Patient Interaction

Metacognition is important to integrating basic science knowledge into medical learning and practice,33,34 and it is no less important in translating interpersonal knowledge to the physician-patient interaction. Decreased metacognitive effort35 may underpin the decline in empathy seen with increasing medical training.36,37 Understanding how metacognitive practices foster relationship-centered care is important for teaching, developing, and maintaining that care.

Metacognition is already embedded in the fabric of the physician-patient interaction.33,34 The complex interplay of the physician-patient interview, patient examination, and integration of physical as well as ancillary data requires higher-order thinking and the ability to parse out that thinking successfully. As a concrete example, coming to a diagnosis requires thinking about what has been presented during the physician-patient interaction and considering what supports and suggests the disease while a list of potential differential diagnosis alternatives is being generated. Physicians are trained to apply this clinical reasoning approach to their patient care.

Conversely, although communication skills are a key component of doctoring,38 both between physician and patient as well as among other colleagues and staff, many physicians have never received formal training in communication skills,26,32,39 though it is now an integral part of medical school curricula.40 When such training is mandatory, less than 1% of physicians continue to believe that there was no benefit, even from a single 8-hour communications skills training session.41 Communication cannot be taught comprehensively in 8 hours; thus, the benefit of such training may be the end result of metacognition and increased self-awareness (Table 1).42,43

Building Relationship-Centered Care Through Metacognitive Attention

Metacognition as manifested by such self-awareness can build relationship-centered care.4 Self-awareness can be taught through mentorship or role models.44 Journaling,40 meditation, and appreciation of beauty and the arts45 can contribute, as well as more formal training programs,32,38,42 as offered by the Academy of Communication in Healthcare. Creating opportunities for patient empowerment also supports relationship-centered care, as does applying knowledge of implicit bias.46

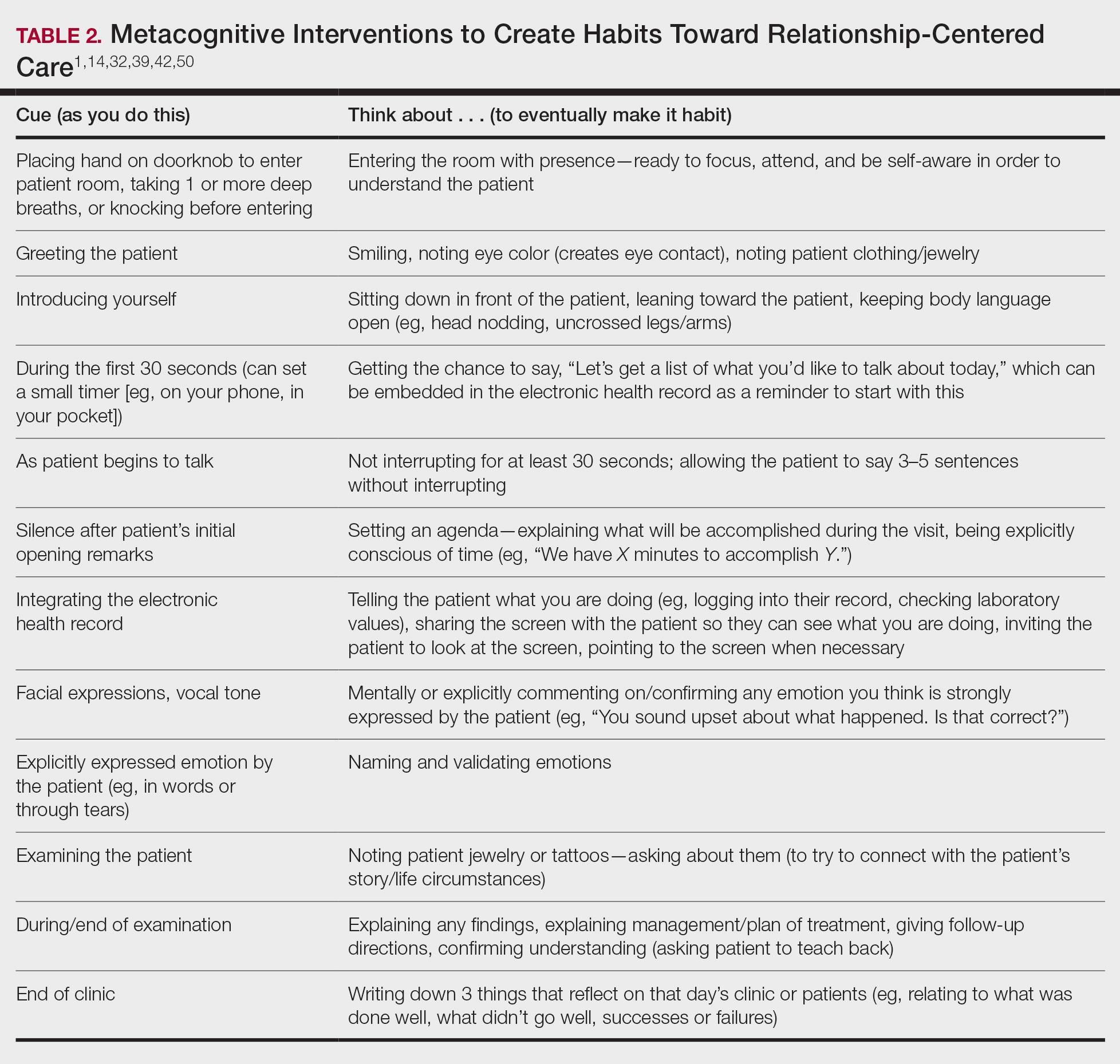

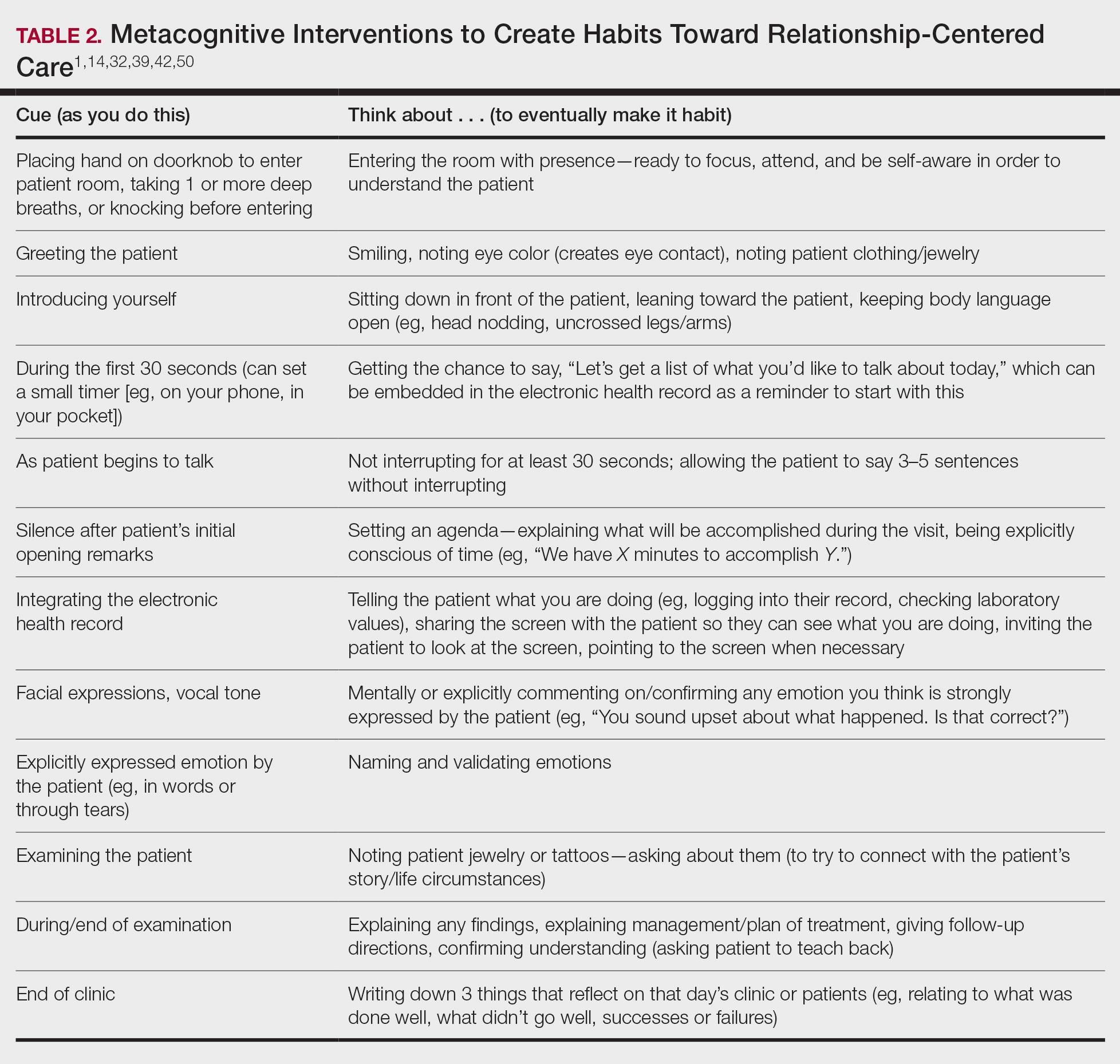

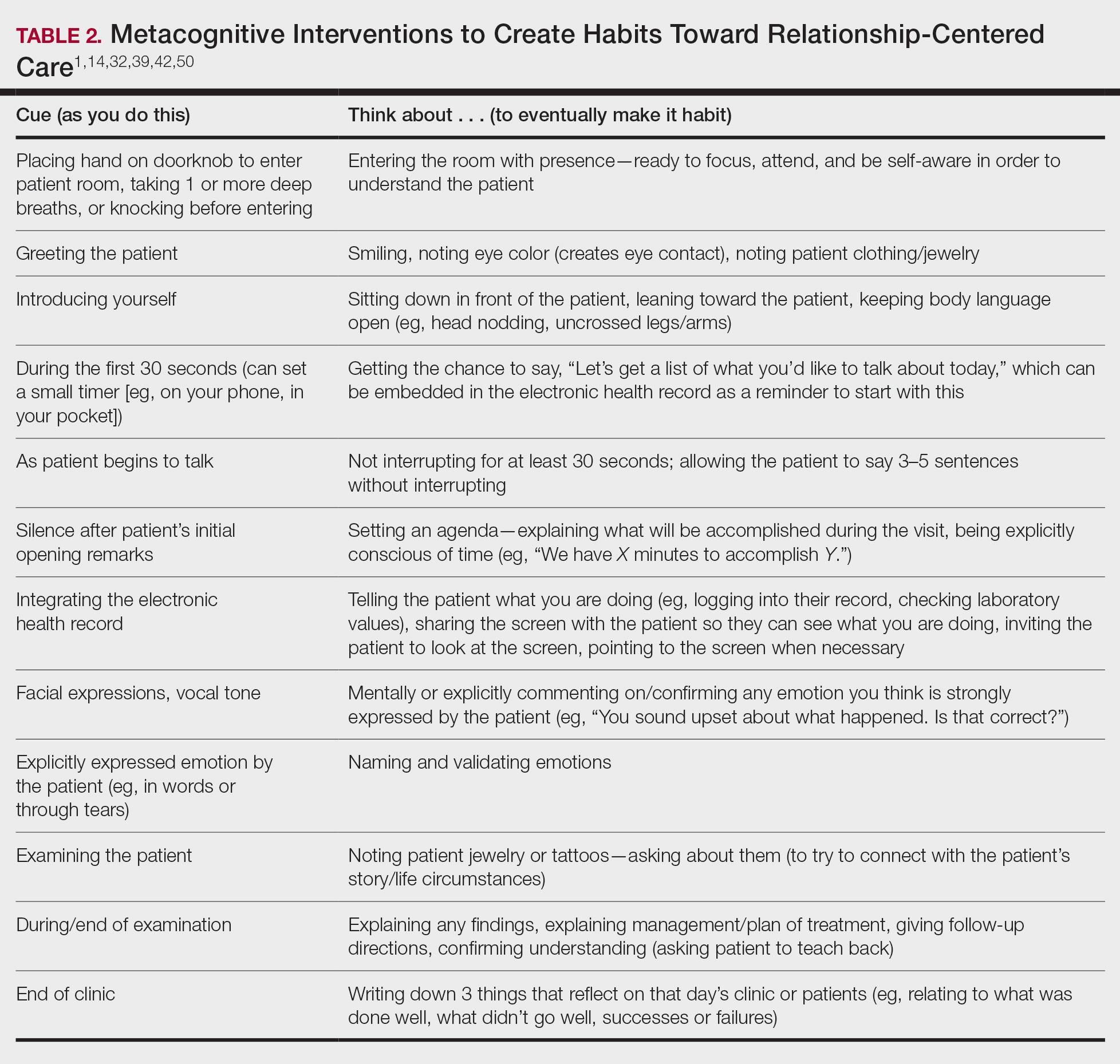

Even without formal training, relationship-centered care can be built through attention to cues9—visual (eg, sitting down, other body language),47,48 auditory (eg, knocking, language, tone, conversational flow),48,49 and emotional (eg, clinical empathy, emotional intelligence)(Table 2). Such attention is familiar to everyone, not just physicians or patients, through interactions outside of health care; inattention may be due to the hidden curriculum or culture of medicine40 as well as real-time changes, such as the introduction of the electronic health record.51 Inattention to these cues also may be a result of context-specific knowledge, in which a physician’s real-life communication skills are not applied to the unique context of patient care.

Although the theoretical foundation of relationship-centered care is relatively complex,9 a simple formula that has improved patient experience is “The Big 3,” which entails (1) simply knocking before entering the examination room, (2) sitting, and (3) asking, “What is your main concern?”30 Another relatively simple technique would be to involve the patient with the electronic health record by sharing the screen with them.52 Learning about narrative medicine and developing skills to appreciate each patient’s story is another method to increase relationship-centered care,40,53 as is emotional intelligence.54 These interventions are simple to implement, and good relationship-centered care will save time, help manage patient visits more effectively, and aid in avoiding the urgent new concern that the patient adds at the end of the visit.55 The positive effect of these different interventions highlights that small changes (Table 2) can shift the prevailing culture of medicine to become more relationship centered.56

Metacognitive Attention Can Generate Habit

Taking metacognition a step further, these small interventions can become habit11,14,39 through self-awareness, deliberate practice, and feedback.43 Habit is generated by linking a given intervention to another defined cue. For example, placing a hand on a doorknob to enter an examination room can be the cue to generate a habit of entering with presence.14 Alternatively, before entering an examination room, taking 3 deep breaths can be the cue to trigger presence.14 Habits can be created in just 3 weeks,57 and other proposed cues to generate habits toward relationship-centered care are listed in Table 2. By creating habit through metacognitive attention, relationship-centered care will become something that happens subconsciously without further burdening physicians with another task. Asking patients for permission to record video of an interaction also can create opportunities for self-awareness and self-evaluation through rewatching the video.58

Final Thoughts

Physicians already have the tools to create relationship-centered care in physician-patient interactions. A critical mental shift is to develop habits and apply thinking patterns toward understanding and responding appropriately to patients of all ethnicities and their emotions in the physician-patient interaction. This shift is aided by metacognitive awareness (Table 1) and the development of useful habits (Table 2).

- Sanders L, Fortin AH VI, Schiff GD. Connecting with patients—the missing links. JAMA. 2020;323:33-34.

- Peck BM, Denney M. Disparities in the conduct of the medical encounter: the effects of physician and patient race and gender. SAGE Open. 2012;2:1-14.

- Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-centered care. a constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 1):S3-S8.

- Tresolini CP, Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. Pew Health Professions Commission; 1994.

- Hojat M. Empathy in Health Professions Education and Patient Care. Springer; 2016.

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, et al. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Burn Res. 2017;6:18-29.

- Frankel RM, Quill T. Integrating biopsychosocial and relationship-centered care into mainstream medical practice: a challenge that continues to produce positive results. Fam Syst Health. 2005;23:413-421.

- Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1163-1165.

- Ventres WB, Frankel RM. Shared presence in physician-patient communication: a graphic representation. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:270-279.

- Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, et al. Delving below the surface: understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 1):S21-S27.

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833-839.

- Dobie S. Viewpoint: reflections on a well-traveled path: self-awareness, mindful practice, and relationship-centered care as foundations for medical education. Acad Med. 2007;82:422-427.

- Rabow MW. Meaning and relationship-centered care: recommendations for clinicians attending to the spiritual distress of patients at the end of life. Ethics Med Public Health. 2019;9:57-62.

- Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323:70-81.

- Rakel DP, Guerrera MP, Bayles BP, et al. CAM education: promoting a salutogenic focus in health care. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:87-93.

- Olaisen RH, Schluchter MD, Flocke SA, et al. Assessing the longitudinal impact of physician-patient relationship on functional health. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:422-429.

- Berg GM, Ekengren F, Lee FA, et al. Patient satisfaction with surgeons in a trauma population: testing a structural equation model using perceptions of interpersonal and technical care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1316-1322.

- Nassar A, Weimer-Elder B, Kline M, et al. Developing an inpatient relationship-centered communication curriculum for surgical teams: pilot study. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(4 suppl 2):E48.

- Caldicott CV, Dunn KA, Frankel RM. Can patients tell when they are unwanted? “turfing” in residency training. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:104-111.

- Tucker Edmonds B, Mogul M, Shea JA. Understanding low-income African American women’s expectations, preferences, and priorities in prenatal care. Fam Community Health. 2015;38:149-157.

- Sundstrom B, Szabo C, Dempsey A. “My body. my choice:” a qualitative study of the influence of trust and locus of control on postpartum contraceptive choice. J Health Commun. 2018;23:162-169.

- Block S, Billings JA. Nurturing humanism through teaching palliative care. Acad Med. 1998;73:763-765.

- Hebert RS, Schulz R, Copeland VC, et al. Preparing family caregivers for death and bereavement. insights from caregivers of terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:3-12.

- Nundy S, Oswald J. Relationship-centered care: a new paradigm for population health management. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2:216-219.

- Sprague S. Relationship centered care. J S C Med Assoc. 2009;105:135-136.

- Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, et al. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 1):S28-S34.

- Kenny DA, Veldhuijzen W, van der Weijden T, et al. Interpersonal perception in the context of doctor-patient relationships: a dyadic analysis of doctor-patient communication. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:763-768.

- Tarzian AJ, Neal MT, O’Neil JA. Attitudes, experiences, and beliefs affecting end-of-life decision-making among homeless individuals. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:36-48.

- Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:5-15.

- Sharieff GQ. MD to MD coaching: improving physician-patient experience scores: what works, what doesn’t. J Patient Exp. 2017;4:210-212.

- Duggan AP, Bradshaw YS, Swergold N, et al. When rapport building extends beyond affiliation: communication overaccommodation toward patients with disabilities. Perm J. 2011;15:23-30.

- Hirschmann K, Rosler G, Fortin AH VI. “For me, this has been transforming”: a qualitative analysis of interprofessional relationship-centered communication skills training. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:1007-1014.

- Hennrikus EF, Skolka MP, Hennrikus N. Applying metacognition through patient encounters and illness scripts to create a conceptual framework for basic science integration, storage, and retrieval. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5:2382120518777770.

- Eichbaum QG. Thinking about thinking and emotion: the metacognitive approach to the medical humanities that integrates the humanities with the basic and clinical sciences. Perm J. 2014;18:64-75.

- Stansfield RB, Schwartz A, O’Brien CL, et al. Development of a metacognitive effort construct of empathy during clinical training: a longitudinal study of the factor structure of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21:5-17.

- Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182-1191.

- Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86:996-1009.

- Chou CL, Hirschmann K, Fortin AHT, et al. The impact of a faculty learning community on professional and personal development: the facilitator training program of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. Acad Med. 2014;89:1051-1056.

- Rider EA. Advanced communication strategies for relationship-centered care. Pediatr Ann. 2011;40:447-453.

- Reichman JAH. Narrative competence, mindfulness,and relationship-centered care in medical education: an innovative approach to teaching medical interviewing. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2015;75(8-A(E)).

- Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:755-761.

- Hatem DS, Barrett SV, Hewson M, et al. Teaching the medical interview: methods and key learning issues in a faculty development course. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1718-1724.

- Gilligan TD, Baile WF. ASCO patient-clinician communication guideline: fostering relationship-centered care. ASCO Connection. November 20, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2021. https://connection.asco.org/blogs/asco-patient-clinician-communication-guideline-fostering-relationship-centered-care

- Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. The hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;(suppl 1):S16-S20.

- Puchalski CM, Guenther M. Restoration and re-creation: spirituality in the lives of healthcare professionals. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:254-258.

- Williams SW, Hanson LC, Boyd C, et al. Communication, decision making, and cancer: what African Americans want physicians to know. J Palliative Med. 2008;11:1221-1226.

- Lindsley I, Woodhead S, Micallef C, et al. The concept of body language in the medical consultation. Psychiatr Danub. 2015;27(suppl 1):S41-S47.

- Hall JA, Harrigan JA, Rosenthal R. Nonverbal behavior in clinician-patient interaction. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4:21-37.

- Ness DE, Kiesling SF. Language and connectedness in the medical and psychiatric interview. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:139-144.

- Miller WL. The clinical hand: a curricular map for relationship-centered care. Fam Med. 2004;36:330-335.

- Wald HS, George P, Reis SP, et al. Electronic health record training in undergraduate medical education: bridging theory to practice with curricula for empowering patient- and relationship-centered care in the computerized setting. Acad Med. 2014;89:380-386.

- Silverman H, Ho YX, Kaib S, et al. A novel approach to supporting relationship-centered care through electronic health record ergonomic training in preclerkship medical education. Acad Med. 2014;89:1230-1234.

- Weiss T, Swede MJ. Transforming preprofessional health education through relationship-centered care and narrative medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:222-233.

- Blanch-Hartigan D. An effective training to increase accurate recognition of patient emotion cues. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:274-280.

- White J, Levinson W, Roter D. “Oh, by the way ...”: the closing moments of the medical visit. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:24-28.

- Suchman AL, Williamson PR, Litzelman DK, et al. Toward an informal curriculum that teaches professionalism. Transforming the social environment of a medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:501-504.

- Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, et al. How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;40:998-1009.

- Little P, White P, Kelly J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention targeting predominantly non-verbal communication in general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65:E351-E356.

Communication and relationships cannot be taken for granted, particularly in the physician-patient relationship, where life-altering diagnoses may be given. With one diagnosis, someone’s life may be changed, and both physicians and patients need to be cognizant of the importance of a strong relationship and clear communication.

In the current US health care system, both physicians and patients often are not getting their needs met, and studies that include factors of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status suggest that physician-patient relationship barriers contribute to racial disparities in health care.1,2 Although patient-centered care is a widely recognized and upheld model, relationship-centered care between physician and patient involves focusing on the patient and the physician-patient relationship through recognizing personhood, affect (being empathic), and reciprocal influence.3,4 Although it is not necessarily intuitive because it can appear to be yet another task for busy physicians, relationship-centered care improves health care delivery for both physicians and patients through decreased physician burnout, reduced medical errors, and better patient outcomes and satisfaction.5,6

Every physician, patient, and physician-patient relationship is different; unlike the standard questions directed at a routine patient history focused on gathering data, there is no one-size-fits-all relationship-centered conversation.7-10 As with any successful interaction between 2 people, there is a certain amount of necessary self-awareness (Table 1)11 that allows for improvisation and appropriate responsiveness to what is seen, heard, and felt. Rather than attending solely to disease states, the focus of relationship-centered care is on patients, interpersonal interaction, and promoting health and well-being.15

This review summarizes the existing literature on relationship-centered care, introduces the use of metacognition (Table 1), and suggests creating simple habits to promote such care. The following databases were searched from inception through November 23, 2020, using the term relationship-centered care: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Academic Search Premier (EBSCOhost), and ERIC (ProQuest). A total of 1772 records were retrieved through searches, and after deduplication of 1116 studies, 350 records were screened through a 2-part process. Articles were first screened by title and abstract for relevance to the relationship between physician and patient, with 185 studies deemed irrelevant (eg, pertaining to the relationship of veterinarian to animal). The remaining 165 studies were assessed for eligibility, with 69 further studies excluded for various reasons. The screening process resulted in 96 articles considered in this review.

Definitions/key terms, as used in this article, are listed in Table 1.

Background of Relationship-Centered Care

Given time constraints, the diagnosis and treatment of medical problems often are the focus of physicians. Although proper medical diagnosis and treatment are important, and their delivery is made possible by the physician having the appropriate knowledge, a physician-patient relationship that focuses solely on disease without acknowledging the patient creates a system that ultimately neglects both patients and physicians.15 This prevailing physician-patient relationship paradigm is suboptimal, and a proposed remedy is relationship-centered care, which focuses on relationships among the human beings in health care interactions.3 Relationship-centered care has 4 principles: (1) the personhood of each party must be recognized, (2) emotion is part of relationships, (3) relationships are reciprocal and not just one way, and (4) creating these types of relationships is morally valuable3 and beneficial to patient care.16

Assessment of the Need for Relationship-Centered Care

Relationship-centered care has been studied in physician-patient interactions in various health care settings.17-23 For at least 2 decades, relationship-centered care has been set forth as a model,4,24,25 but there are challenges. Physicians tend to overrate or underrate their communication skills in patient interactions.26,27 A given physician’s preferences often still seem to supersede those of the patient.3,28,29 The impetus to develop relationship-centered care skills generally needs to be internally driven,4,30 as, ultimately, physicians and patients have varying needs.4,31 However, providing physicians with a potential structure is helpful.32

A Solution: Metacognition in the Physician-Patient Interaction

Metacognition is important to integrating basic science knowledge into medical learning and practice,33,34 and it is no less important in translating interpersonal knowledge to the physician-patient interaction. Decreased metacognitive effort35 may underpin the decline in empathy seen with increasing medical training.36,37 Understanding how metacognitive practices foster relationship-centered care is important for teaching, developing, and maintaining that care.

Metacognition is already embedded in the fabric of the physician-patient interaction.33,34 The complex interplay of the physician-patient interview, patient examination, and integration of physical as well as ancillary data requires higher-order thinking and the ability to parse out that thinking successfully. As a concrete example, coming to a diagnosis requires thinking about what has been presented during the physician-patient interaction and considering what supports and suggests the disease while a list of potential differential diagnosis alternatives is being generated. Physicians are trained to apply this clinical reasoning approach to their patient care.

Conversely, although communication skills are a key component of doctoring,38 both between physician and patient as well as among other colleagues and staff, many physicians have never received formal training in communication skills,26,32,39 though it is now an integral part of medical school curricula.40 When such training is mandatory, less than 1% of physicians continue to believe that there was no benefit, even from a single 8-hour communications skills training session.41 Communication cannot be taught comprehensively in 8 hours; thus, the benefit of such training may be the end result of metacognition and increased self-awareness (Table 1).42,43

Building Relationship-Centered Care Through Metacognitive Attention

Metacognition as manifested by such self-awareness can build relationship-centered care.4 Self-awareness can be taught through mentorship or role models.44 Journaling,40 meditation, and appreciation of beauty and the arts45 can contribute, as well as more formal training programs,32,38,42 as offered by the Academy of Communication in Healthcare. Creating opportunities for patient empowerment also supports relationship-centered care, as does applying knowledge of implicit bias.46

Even without formal training, relationship-centered care can be built through attention to cues9—visual (eg, sitting down, other body language),47,48 auditory (eg, knocking, language, tone, conversational flow),48,49 and emotional (eg, clinical empathy, emotional intelligence)(Table 2). Such attention is familiar to everyone, not just physicians or patients, through interactions outside of health care; inattention may be due to the hidden curriculum or culture of medicine40 as well as real-time changes, such as the introduction of the electronic health record.51 Inattention to these cues also may be a result of context-specific knowledge, in which a physician’s real-life communication skills are not applied to the unique context of patient care.

Although the theoretical foundation of relationship-centered care is relatively complex,9 a simple formula that has improved patient experience is “The Big 3,” which entails (1) simply knocking before entering the examination room, (2) sitting, and (3) asking, “What is your main concern?”30 Another relatively simple technique would be to involve the patient with the electronic health record by sharing the screen with them.52 Learning about narrative medicine and developing skills to appreciate each patient’s story is another method to increase relationship-centered care,40,53 as is emotional intelligence.54 These interventions are simple to implement, and good relationship-centered care will save time, help manage patient visits more effectively, and aid in avoiding the urgent new concern that the patient adds at the end of the visit.55 The positive effect of these different interventions highlights that small changes (Table 2) can shift the prevailing culture of medicine to become more relationship centered.56

Metacognitive Attention Can Generate Habit

Taking metacognition a step further, these small interventions can become habit11,14,39 through self-awareness, deliberate practice, and feedback.43 Habit is generated by linking a given intervention to another defined cue. For example, placing a hand on a doorknob to enter an examination room can be the cue to generate a habit of entering with presence.14 Alternatively, before entering an examination room, taking 3 deep breaths can be the cue to trigger presence.14 Habits can be created in just 3 weeks,57 and other proposed cues to generate habits toward relationship-centered care are listed in Table 2. By creating habit through metacognitive attention, relationship-centered care will become something that happens subconsciously without further burdening physicians with another task. Asking patients for permission to record video of an interaction also can create opportunities for self-awareness and self-evaluation through rewatching the video.58

Final Thoughts

Physicians already have the tools to create relationship-centered care in physician-patient interactions. A critical mental shift is to develop habits and apply thinking patterns toward understanding and responding appropriately to patients of all ethnicities and their emotions in the physician-patient interaction. This shift is aided by metacognitive awareness (Table 1) and the development of useful habits (Table 2).

Communication and relationships cannot be taken for granted, particularly in the physician-patient relationship, where life-altering diagnoses may be given. With one diagnosis, someone’s life may be changed, and both physicians and patients need to be cognizant of the importance of a strong relationship and clear communication.

In the current US health care system, both physicians and patients often are not getting their needs met, and studies that include factors of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status suggest that physician-patient relationship barriers contribute to racial disparities in health care.1,2 Although patient-centered care is a widely recognized and upheld model, relationship-centered care between physician and patient involves focusing on the patient and the physician-patient relationship through recognizing personhood, affect (being empathic), and reciprocal influence.3,4 Although it is not necessarily intuitive because it can appear to be yet another task for busy physicians, relationship-centered care improves health care delivery for both physicians and patients through decreased physician burnout, reduced medical errors, and better patient outcomes and satisfaction.5,6

Every physician, patient, and physician-patient relationship is different; unlike the standard questions directed at a routine patient history focused on gathering data, there is no one-size-fits-all relationship-centered conversation.7-10 As with any successful interaction between 2 people, there is a certain amount of necessary self-awareness (Table 1)11 that allows for improvisation and appropriate responsiveness to what is seen, heard, and felt. Rather than attending solely to disease states, the focus of relationship-centered care is on patients, interpersonal interaction, and promoting health and well-being.15

This review summarizes the existing literature on relationship-centered care, introduces the use of metacognition (Table 1), and suggests creating simple habits to promote such care. The following databases were searched from inception through November 23, 2020, using the term relationship-centered care: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), Academic Search Premier (EBSCOhost), and ERIC (ProQuest). A total of 1772 records were retrieved through searches, and after deduplication of 1116 studies, 350 records were screened through a 2-part process. Articles were first screened by title and abstract for relevance to the relationship between physician and patient, with 185 studies deemed irrelevant (eg, pertaining to the relationship of veterinarian to animal). The remaining 165 studies were assessed for eligibility, with 69 further studies excluded for various reasons. The screening process resulted in 96 articles considered in this review.

Definitions/key terms, as used in this article, are listed in Table 1.

Background of Relationship-Centered Care

Given time constraints, the diagnosis and treatment of medical problems often are the focus of physicians. Although proper medical diagnosis and treatment are important, and their delivery is made possible by the physician having the appropriate knowledge, a physician-patient relationship that focuses solely on disease without acknowledging the patient creates a system that ultimately neglects both patients and physicians.15 This prevailing physician-patient relationship paradigm is suboptimal, and a proposed remedy is relationship-centered care, which focuses on relationships among the human beings in health care interactions.3 Relationship-centered care has 4 principles: (1) the personhood of each party must be recognized, (2) emotion is part of relationships, (3) relationships are reciprocal and not just one way, and (4) creating these types of relationships is morally valuable3 and beneficial to patient care.16

Assessment of the Need for Relationship-Centered Care

Relationship-centered care has been studied in physician-patient interactions in various health care settings.17-23 For at least 2 decades, relationship-centered care has been set forth as a model,4,24,25 but there are challenges. Physicians tend to overrate or underrate their communication skills in patient interactions.26,27 A given physician’s preferences often still seem to supersede those of the patient.3,28,29 The impetus to develop relationship-centered care skills generally needs to be internally driven,4,30 as, ultimately, physicians and patients have varying needs.4,31 However, providing physicians with a potential structure is helpful.32

A Solution: Metacognition in the Physician-Patient Interaction

Metacognition is important to integrating basic science knowledge into medical learning and practice,33,34 and it is no less important in translating interpersonal knowledge to the physician-patient interaction. Decreased metacognitive effort35 may underpin the decline in empathy seen with increasing medical training.36,37 Understanding how metacognitive practices foster relationship-centered care is important for teaching, developing, and maintaining that care.