User login

Exploring the Utility of Artificial Intelligence During COVID-19 in Dermatology Practice

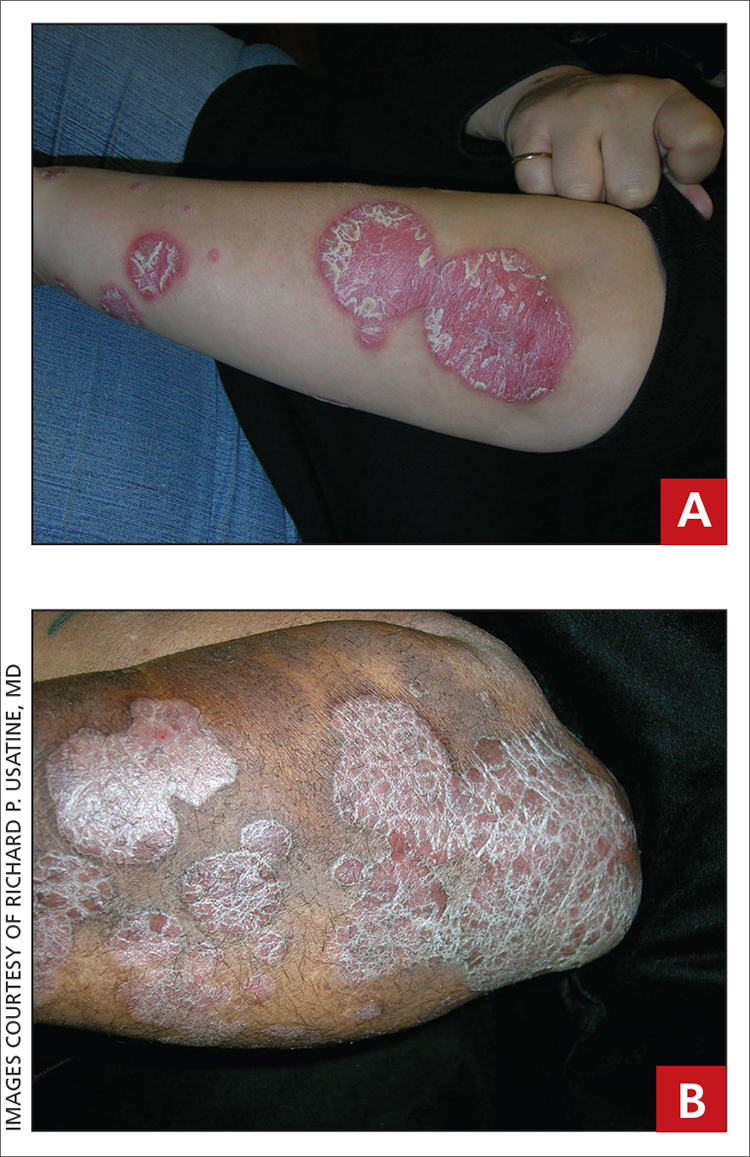

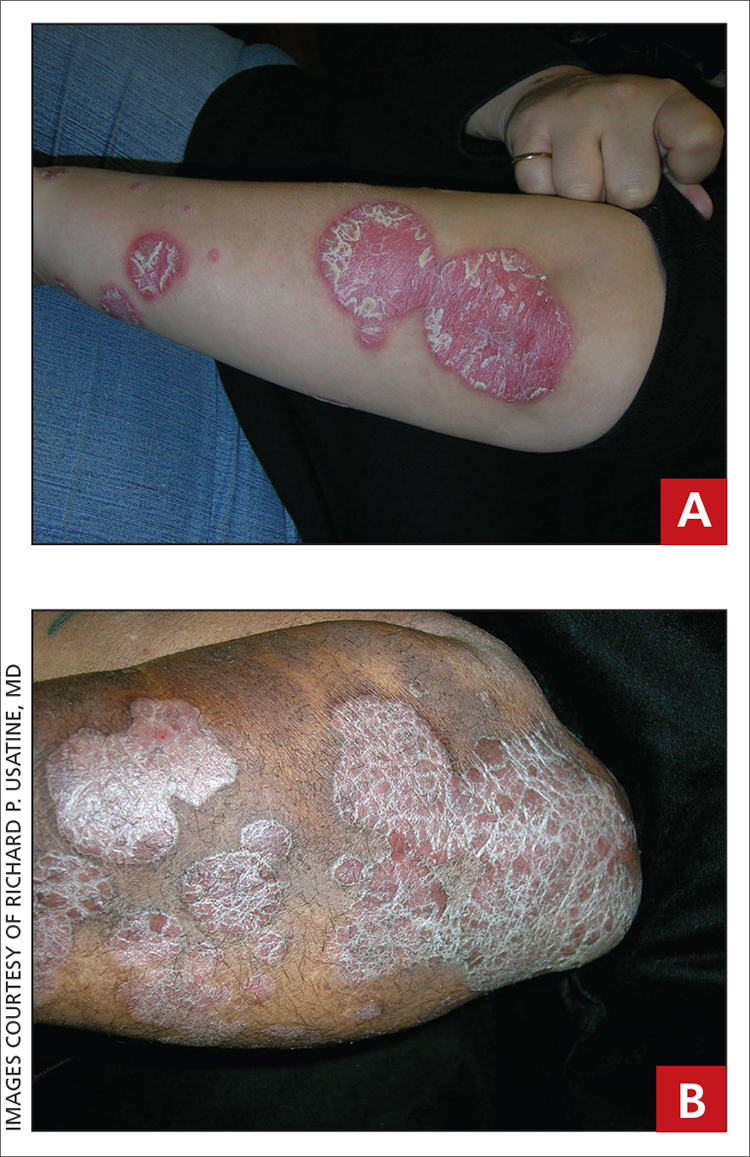

With the need to adapt to the given challenges associated with COVID-19, artificial intelligence (AI) serves as a potential tool in providing access to medical-based diagnosis in a novel way. Artificial intelligence is defined as intelligence harnessed by machines that have the ability to perform what is called cognitive thinking and to mimic the problem-solving abilities of the human mind. Virtual AI in dermatology entails neural network–based guidance that includes developing algorithms to detect skin pathology through photographs.1 To use AI in dermatology, recognition of visual patterns must be established to give diagnoses. These neural networks have been used to classify skin diseases, including cancer, actinic keratosis, and warts.2

AI for Skin Cancer

The use of AI to classify melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer has been studied extensively, including the following 2 research projects.

Convolutional Neural Network

In 2017, Stanford University published a study in which a deep-learning algorithm known as a convolutional neural network was used to classify skin lesions.3 The network was trained using a dataset of 129,450 clinical images of 2032 diseases. Its performance was compared to that of 21 board-certified dermatologists on biopsy-proven clinical images with 2 classifications of cases: (1) keratinocyte carcinoma as opposed to benign seborrheic keratosis and (2) malignant melanoma as opposed to benign nevi—the first representing the most common skin cancers, and the second, the deadliest skin cancers. The study showed that the machine could accurately identify and classify skin cancers compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. The study did not include demographic information, which limits its external validity.3

Dermoscopic Image Classification

A 2019 study by Brinker and colleagues4 showed the superiority of automated dermoscopic melanoma image classifications compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. For the study, 804 biopsy-proven images of melanoma and nevi (1:1 ratio) were randomly presented to dermatologists for their evaluation and recommended treatment (yielding 19,296 recommendations). The dermatologists classified the lesions with a sensitivity of 67.2% and specificity of 62.2%; the trained convolutional neural network attained both higher sensitivity (82.3%) and higher specificity (77.9%).4

Smartphone Diagnosis of Melanoma

An application of AI has been to use smartphone apps for the diagnosis of melanoma. The most utilized and novel algorithm-based smartphone app that assesses skin lesions for malignancy characteristics is SkinVision. With a simple download from Apple’s App Store, this technology allows a person to check their skin spots by taking a photograph and receiving algorithmic risk-assessment feedback. This inexpensive software ($51.78 a year) also allows a patient’s physician to assess the photograph and then validate their assessment by comparing it with the algorithmic analysis that the program provides.5

A review of SkinVision conducted by Thissen and colleagues6 found that, in a hypothetical population of 1000 adults of whom 3% actually had melanoma, 4 of those 30 people would not have been flagged as at “high risk” by SkinVision. There also was a high false-positive rate with the app, with more than 200 people flagged as at high risk. The analysis pegged SkinVision as having a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 79%.6

In summary, systematic review of diagnostic accuracy has shown that, although there is accuracy in AI analyses, it should be used only as a guide for health care advice due to variability in algorithm performance.7

Utility of AI in Telehealth

Artificial intelligence algorithms could be created to ensure telehealth image accuracy, stratify risk, and track patient progress. With teledermatology visits on the rise during the COVID-19 pandemic, AI algorithms could ensure that photographs of appropriate quality are taken. Also, patients could be organized by risk factors with such algorithms, allowing physicians to save time on triage and stratification. Algorithms also could be used to track a telehealth patient’s treatment and progress.8

Furthermore, there is a need for an algorithm that has the ability to detect, quantify, and monitor changes in dermatologic conditions using images that patients have uploaded. This capability will lead to creation of a standardized quantification scale that will allow physicians to virtually track the progression of visible skin pathologies.

Hazards of Racial Bias in AI

Artificial intelligence is limited by racial disparity bias seen in computerized medicine. For years, the majority of dermatology research, especially in skin cancer, has been conducted on fairer-skinned populations. This bias has existed at the expense of darker-skinned patients, whose skin conditions and symptoms present differently,9 and reflects directly in available data sets that can be used to develop AI algorithms. Because these data are inadequate to the task, AI might misdiagnose skin cancer in people of color or miss an existing condition entirely.10 Consequently, the higher rate of skin cancer mortality that is reported in people of color is likely to persist with the rise of AI in dermatology.11 A more representative database of imaged skin lesions needs to be utilized to create a diversely representative and applicable data set for AI algorithms.12

Benefits of Conversational Agents

Another method by which AI could be incorporated into dermatology is through what is known as a conversational agent (CA)—AI software that engages in a dialogue with users by interpreting their voice and replying to them through text, image, or voice.13 Conversational agents facilitate remote patient management, allow clinicians to focus on other functions, and aid in data collection.14 A 2014 study showed that patients were significantly more likely to disclose history and emotions when informed they were interacting with a CA than with a human clinician (P=.007).15 Such benefits could be invaluable in dermatology, where emotions and patient perceptions of skin conditions play into the treatment process.

However, some evidence showed that CAs cannot respond to patients’ statements in all circumstances.16 It also is unclear how well CAs recognize nuanced statements that might signal potential harm. This fits into the greater theme of a major problem with AI: the lack of a reliable response in all circumstances.13

Final Thoughts

The practical implementations of AI in dermatology are still being explored. Given the uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and the future of patient care, AI might serve as an important asset in assisting with the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, physician productivity, and patient monitoring.

- Amisha, Malik P, Pathania M, et al. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2328-2331. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_440_19

- Han SS, Kim MS, Lim W, et al. Classification of the clinical images for benign and malignant cutaneous tumors using a deep learning algorithm. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1529-1538. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.028

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

- Brinker TJ, Hekler A, Enk AH, et al. Deep neural networks are superior to dermatologists in melanoma image classification. Eur J Cancer. 2019;119:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.023

- Regulated medical device for detecting skin cancer. SkinVision website. Accessed July 23, 2021. https://www.skinvision.com/hcp/

- Thissen M, Udrea A, Hacking M, et al. mHealth app for risk assessment of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions—a study on sensitivity and specificity in detecting malignancy. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:948-954. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0259

- Freeman K, Dinnes J, Chuchu N, et al. Algorithm based smartphone apps to assess risk of skin cancer in adults: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2020;368:m127. doi:10.1136/bmj.m127

- Puri P, Comfere N, Pittelkow MR, et al. COVID-19: an opportunity to build dermatology’s digital future. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14149. doi:10.1111/dth.14149

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Adamson AS, Smith A. Machine learning and health care disparities in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1247-1248. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2348

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:S0190-9622(13)01296-6

- Alabdulkareem A. Artificial intelligence and dermatologists: friends or foes? J Dermatol Dermatolog Surg. 2019;23:57-60. doi:10.4103/jdds.jdds_19_19

- McGreevey JD 3rd, Hanson CW 3rd, Koppel R. Clinical, legal, and ethical aspects of artificial intelligence-assisted conversational agents in health care. JAMA. 2020;324:552-553. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2724

- Piau A, Crissey R, Brechemier D, et al. A smartphone chatbot application to optimize monitoring of older patients with cancer. Int J Med Inform. 2019;128:18-23. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.013

- Lucas GM, Gratch J, King A, et al. It’s only a computer: virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput Human Behav. 2014;37:94-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.043

- Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, et al. Smartphone-based conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:619-625. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0400

With the need to adapt to the given challenges associated with COVID-19, artificial intelligence (AI) serves as a potential tool in providing access to medical-based diagnosis in a novel way. Artificial intelligence is defined as intelligence harnessed by machines that have the ability to perform what is called cognitive thinking and to mimic the problem-solving abilities of the human mind. Virtual AI in dermatology entails neural network–based guidance that includes developing algorithms to detect skin pathology through photographs.1 To use AI in dermatology, recognition of visual patterns must be established to give diagnoses. These neural networks have been used to classify skin diseases, including cancer, actinic keratosis, and warts.2

AI for Skin Cancer

The use of AI to classify melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer has been studied extensively, including the following 2 research projects.

Convolutional Neural Network

In 2017, Stanford University published a study in which a deep-learning algorithm known as a convolutional neural network was used to classify skin lesions.3 The network was trained using a dataset of 129,450 clinical images of 2032 diseases. Its performance was compared to that of 21 board-certified dermatologists on biopsy-proven clinical images with 2 classifications of cases: (1) keratinocyte carcinoma as opposed to benign seborrheic keratosis and (2) malignant melanoma as opposed to benign nevi—the first representing the most common skin cancers, and the second, the deadliest skin cancers. The study showed that the machine could accurately identify and classify skin cancers compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. The study did not include demographic information, which limits its external validity.3

Dermoscopic Image Classification

A 2019 study by Brinker and colleagues4 showed the superiority of automated dermoscopic melanoma image classifications compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. For the study, 804 biopsy-proven images of melanoma and nevi (1:1 ratio) were randomly presented to dermatologists for their evaluation and recommended treatment (yielding 19,296 recommendations). The dermatologists classified the lesions with a sensitivity of 67.2% and specificity of 62.2%; the trained convolutional neural network attained both higher sensitivity (82.3%) and higher specificity (77.9%).4

Smartphone Diagnosis of Melanoma

An application of AI has been to use smartphone apps for the diagnosis of melanoma. The most utilized and novel algorithm-based smartphone app that assesses skin lesions for malignancy characteristics is SkinVision. With a simple download from Apple’s App Store, this technology allows a person to check their skin spots by taking a photograph and receiving algorithmic risk-assessment feedback. This inexpensive software ($51.78 a year) also allows a patient’s physician to assess the photograph and then validate their assessment by comparing it with the algorithmic analysis that the program provides.5

A review of SkinVision conducted by Thissen and colleagues6 found that, in a hypothetical population of 1000 adults of whom 3% actually had melanoma, 4 of those 30 people would not have been flagged as at “high risk” by SkinVision. There also was a high false-positive rate with the app, with more than 200 people flagged as at high risk. The analysis pegged SkinVision as having a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 79%.6

In summary, systematic review of diagnostic accuracy has shown that, although there is accuracy in AI analyses, it should be used only as a guide for health care advice due to variability in algorithm performance.7

Utility of AI in Telehealth

Artificial intelligence algorithms could be created to ensure telehealth image accuracy, stratify risk, and track patient progress. With teledermatology visits on the rise during the COVID-19 pandemic, AI algorithms could ensure that photographs of appropriate quality are taken. Also, patients could be organized by risk factors with such algorithms, allowing physicians to save time on triage and stratification. Algorithms also could be used to track a telehealth patient’s treatment and progress.8

Furthermore, there is a need for an algorithm that has the ability to detect, quantify, and monitor changes in dermatologic conditions using images that patients have uploaded. This capability will lead to creation of a standardized quantification scale that will allow physicians to virtually track the progression of visible skin pathologies.

Hazards of Racial Bias in AI

Artificial intelligence is limited by racial disparity bias seen in computerized medicine. For years, the majority of dermatology research, especially in skin cancer, has been conducted on fairer-skinned populations. This bias has existed at the expense of darker-skinned patients, whose skin conditions and symptoms present differently,9 and reflects directly in available data sets that can be used to develop AI algorithms. Because these data are inadequate to the task, AI might misdiagnose skin cancer in people of color or miss an existing condition entirely.10 Consequently, the higher rate of skin cancer mortality that is reported in people of color is likely to persist with the rise of AI in dermatology.11 A more representative database of imaged skin lesions needs to be utilized to create a diversely representative and applicable data set for AI algorithms.12

Benefits of Conversational Agents

Another method by which AI could be incorporated into dermatology is through what is known as a conversational agent (CA)—AI software that engages in a dialogue with users by interpreting their voice and replying to them through text, image, or voice.13 Conversational agents facilitate remote patient management, allow clinicians to focus on other functions, and aid in data collection.14 A 2014 study showed that patients were significantly more likely to disclose history and emotions when informed they were interacting with a CA than with a human clinician (P=.007).15 Such benefits could be invaluable in dermatology, where emotions and patient perceptions of skin conditions play into the treatment process.

However, some evidence showed that CAs cannot respond to patients’ statements in all circumstances.16 It also is unclear how well CAs recognize nuanced statements that might signal potential harm. This fits into the greater theme of a major problem with AI: the lack of a reliable response in all circumstances.13

Final Thoughts

The practical implementations of AI in dermatology are still being explored. Given the uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and the future of patient care, AI might serve as an important asset in assisting with the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, physician productivity, and patient monitoring.

With the need to adapt to the given challenges associated with COVID-19, artificial intelligence (AI) serves as a potential tool in providing access to medical-based diagnosis in a novel way. Artificial intelligence is defined as intelligence harnessed by machines that have the ability to perform what is called cognitive thinking and to mimic the problem-solving abilities of the human mind. Virtual AI in dermatology entails neural network–based guidance that includes developing algorithms to detect skin pathology through photographs.1 To use AI in dermatology, recognition of visual patterns must be established to give diagnoses. These neural networks have been used to classify skin diseases, including cancer, actinic keratosis, and warts.2

AI for Skin Cancer

The use of AI to classify melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer has been studied extensively, including the following 2 research projects.

Convolutional Neural Network

In 2017, Stanford University published a study in which a deep-learning algorithm known as a convolutional neural network was used to classify skin lesions.3 The network was trained using a dataset of 129,450 clinical images of 2032 diseases. Its performance was compared to that of 21 board-certified dermatologists on biopsy-proven clinical images with 2 classifications of cases: (1) keratinocyte carcinoma as opposed to benign seborrheic keratosis and (2) malignant melanoma as opposed to benign nevi—the first representing the most common skin cancers, and the second, the deadliest skin cancers. The study showed that the machine could accurately identify and classify skin cancers compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. The study did not include demographic information, which limits its external validity.3

Dermoscopic Image Classification

A 2019 study by Brinker and colleagues4 showed the superiority of automated dermoscopic melanoma image classifications compared to the work of board-certified dermatologists. For the study, 804 biopsy-proven images of melanoma and nevi (1:1 ratio) were randomly presented to dermatologists for their evaluation and recommended treatment (yielding 19,296 recommendations). The dermatologists classified the lesions with a sensitivity of 67.2% and specificity of 62.2%; the trained convolutional neural network attained both higher sensitivity (82.3%) and higher specificity (77.9%).4

Smartphone Diagnosis of Melanoma

An application of AI has been to use smartphone apps for the diagnosis of melanoma. The most utilized and novel algorithm-based smartphone app that assesses skin lesions for malignancy characteristics is SkinVision. With a simple download from Apple’s App Store, this technology allows a person to check their skin spots by taking a photograph and receiving algorithmic risk-assessment feedback. This inexpensive software ($51.78 a year) also allows a patient’s physician to assess the photograph and then validate their assessment by comparing it with the algorithmic analysis that the program provides.5

A review of SkinVision conducted by Thissen and colleagues6 found that, in a hypothetical population of 1000 adults of whom 3% actually had melanoma, 4 of those 30 people would not have been flagged as at “high risk” by SkinVision. There also was a high false-positive rate with the app, with more than 200 people flagged as at high risk. The analysis pegged SkinVision as having a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 79%.6

In summary, systematic review of diagnostic accuracy has shown that, although there is accuracy in AI analyses, it should be used only as a guide for health care advice due to variability in algorithm performance.7

Utility of AI in Telehealth

Artificial intelligence algorithms could be created to ensure telehealth image accuracy, stratify risk, and track patient progress. With teledermatology visits on the rise during the COVID-19 pandemic, AI algorithms could ensure that photographs of appropriate quality are taken. Also, patients could be organized by risk factors with such algorithms, allowing physicians to save time on triage and stratification. Algorithms also could be used to track a telehealth patient’s treatment and progress.8

Furthermore, there is a need for an algorithm that has the ability to detect, quantify, and monitor changes in dermatologic conditions using images that patients have uploaded. This capability will lead to creation of a standardized quantification scale that will allow physicians to virtually track the progression of visible skin pathologies.

Hazards of Racial Bias in AI

Artificial intelligence is limited by racial disparity bias seen in computerized medicine. For years, the majority of dermatology research, especially in skin cancer, has been conducted on fairer-skinned populations. This bias has existed at the expense of darker-skinned patients, whose skin conditions and symptoms present differently,9 and reflects directly in available data sets that can be used to develop AI algorithms. Because these data are inadequate to the task, AI might misdiagnose skin cancer in people of color or miss an existing condition entirely.10 Consequently, the higher rate of skin cancer mortality that is reported in people of color is likely to persist with the rise of AI in dermatology.11 A more representative database of imaged skin lesions needs to be utilized to create a diversely representative and applicable data set for AI algorithms.12

Benefits of Conversational Agents

Another method by which AI could be incorporated into dermatology is through what is known as a conversational agent (CA)—AI software that engages in a dialogue with users by interpreting their voice and replying to them through text, image, or voice.13 Conversational agents facilitate remote patient management, allow clinicians to focus on other functions, and aid in data collection.14 A 2014 study showed that patients were significantly more likely to disclose history and emotions when informed they were interacting with a CA than with a human clinician (P=.007).15 Such benefits could be invaluable in dermatology, where emotions and patient perceptions of skin conditions play into the treatment process.

However, some evidence showed that CAs cannot respond to patients’ statements in all circumstances.16 It also is unclear how well CAs recognize nuanced statements that might signal potential harm. This fits into the greater theme of a major problem with AI: the lack of a reliable response in all circumstances.13

Final Thoughts

The practical implementations of AI in dermatology are still being explored. Given the uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and the future of patient care, AI might serve as an important asset in assisting with the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, physician productivity, and patient monitoring.

- Amisha, Malik P, Pathania M, et al. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2328-2331. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_440_19

- Han SS, Kim MS, Lim W, et al. Classification of the clinical images for benign and malignant cutaneous tumors using a deep learning algorithm. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1529-1538. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.028

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

- Brinker TJ, Hekler A, Enk AH, et al. Deep neural networks are superior to dermatologists in melanoma image classification. Eur J Cancer. 2019;119:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.023

- Regulated medical device for detecting skin cancer. SkinVision website. Accessed July 23, 2021. https://www.skinvision.com/hcp/

- Thissen M, Udrea A, Hacking M, et al. mHealth app for risk assessment of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions—a study on sensitivity and specificity in detecting malignancy. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:948-954. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0259

- Freeman K, Dinnes J, Chuchu N, et al. Algorithm based smartphone apps to assess risk of skin cancer in adults: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2020;368:m127. doi:10.1136/bmj.m127

- Puri P, Comfere N, Pittelkow MR, et al. COVID-19: an opportunity to build dermatology’s digital future. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14149. doi:10.1111/dth.14149

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Adamson AS, Smith A. Machine learning and health care disparities in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1247-1248. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2348

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:S0190-9622(13)01296-6

- Alabdulkareem A. Artificial intelligence and dermatologists: friends or foes? J Dermatol Dermatolog Surg. 2019;23:57-60. doi:10.4103/jdds.jdds_19_19

- McGreevey JD 3rd, Hanson CW 3rd, Koppel R. Clinical, legal, and ethical aspects of artificial intelligence-assisted conversational agents in health care. JAMA. 2020;324:552-553. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2724

- Piau A, Crissey R, Brechemier D, et al. A smartphone chatbot application to optimize monitoring of older patients with cancer. Int J Med Inform. 2019;128:18-23. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.013

- Lucas GM, Gratch J, King A, et al. It’s only a computer: virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput Human Behav. 2014;37:94-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.043

- Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, et al. Smartphone-based conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:619-625. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0400

- Amisha, Malik P, Pathania M, et al. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2328-2331. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_440_19

- Han SS, Kim MS, Lim W, et al. Classification of the clinical images for benign and malignant cutaneous tumors using a deep learning algorithm. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1529-1538. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.028

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

- Brinker TJ, Hekler A, Enk AH, et al. Deep neural networks are superior to dermatologists in melanoma image classification. Eur J Cancer. 2019;119:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.023

- Regulated medical device for detecting skin cancer. SkinVision website. Accessed July 23, 2021. https://www.skinvision.com/hcp/

- Thissen M, Udrea A, Hacking M, et al. mHealth app for risk assessment of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions—a study on sensitivity and specificity in detecting malignancy. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:948-954. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0259

- Freeman K, Dinnes J, Chuchu N, et al. Algorithm based smartphone apps to assess risk of skin cancer in adults: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2020;368:m127. doi:10.1136/bmj.m127

- Puri P, Comfere N, Pittelkow MR, et al. COVID-19: an opportunity to build dermatology’s digital future. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14149. doi:10.1111/dth.14149

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Adamson AS, Smith A. Machine learning and health care disparities in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1247-1248. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2348

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:S0190-9622(13)01296-6

- Alabdulkareem A. Artificial intelligence and dermatologists: friends or foes? J Dermatol Dermatolog Surg. 2019;23:57-60. doi:10.4103/jdds.jdds_19_19

- McGreevey JD 3rd, Hanson CW 3rd, Koppel R. Clinical, legal, and ethical aspects of artificial intelligence-assisted conversational agents in health care. JAMA. 2020;324:552-553. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2724

- Piau A, Crissey R, Brechemier D, et al. A smartphone chatbot application to optimize monitoring of older patients with cancer. Int J Med Inform. 2019;128:18-23. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.013

- Lucas GM, Gratch J, King A, et al. It’s only a computer: virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput Human Behav. 2014;37:94-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.043

- Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, et al. Smartphone-based conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:619-625. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0400

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should amass pictures of dermatologic conditions in skin of color to contribute to growing awareness and knowledge of presentation of disease in this population.

- Dermatologists should use artificial intelligence as a tool for delivering more efficient and beneficial patient care.

Medical residents need breastfeeding support too

As working mothers with babies in tow when the COVID-19 crisis struck, countless uncertainties threatened our already precarious work-life balance. We suddenly had many questions:

“If my daycare closes, what will I do for childcare?”

“How do I navigate diaper changes, feedings, and naps with my hectic remote work schedule?”

“If I’m constantly interrupted during the day, should I skip sleep to catch up on work and not let my colleagues down?”

As professionals who work closely with medical trainees, we knew our parenting dilemmas were being experienced even more acutely by our frontline worker colleagues.

Medical training is an increasingly common time to start a family. In a recent study, 34% of trainees in Harvard-affiliated residency programs became parents during training, and another 52% planned to do so. Trainees have higher breastfeeding initiation rates but lower continuation rates than the general population. Early nursing cessation among trainees is well documented nationally and is most often attributed to work-related barriers. These barriers range from insufficient time and limited access to facilities to a lack of support and discrimination by supervisors and peers.

This trend does not discriminate by specialty. Even among training programs known to be “family friendly,” the average duration of nursing is just 4.5 months. Residents of color are disproportionately affected by inadequate support. Studies show that Black parents breastfeed at lower rates than White parents. This has been largely attributed to structural racism and implicit bias, such as Black parents receiving less assistance initiating nursing after delivery. Adequate lactation support and inclusivity are also lacking for transgender parents who choose to breastfeed or chestfeed.

The very nature of residency training, which includes shifts that can span more than 24 hours, conflicts with many health-promoting behaviors like sleeping and eating well. However, its interference with lactation is correlated with gender. Women are disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of unmet lactation goals. These include work-life imbalance, career dissatisfaction, and negative emotions. In a study of pediatric residents, one in four did not achieve their breastfeeding goals. Respondents reported feeling “sad, devastated, defeated, disappointed, guilty, embarrassed, frustrated, angry, like a failure, and inadequate.” Among physician mothers more broadly, discrimination related to pregnancy, parental leave, and nursing is associated with higher self-reported burnout.

Navigating nursing during residency training has more than just emotional and psychological consequences – it also has professional ones. Pursuing personal lactation goals can delay residency program completion and board certification, influence specialty selection, negatively impact research productivity, impede career advancement, and lead to misgivings about career choice.

Trainees and their families are not the only ones harmed by inadequate support in residency programs. Patients and their families are affected, too. Research suggests that physicians’ personal breastfeeding practices affect the advice they give to patients. Those who receive lactation support are more likely to help patients meet their own goals. In the previously mentioned study of pediatric residents, more than 90% of the 400 respondents said their own or their partner’s nursing experience affected their interaction with lactating patients in their clinic or hospital.

Increased lactation support is a straightforward, low-cost, high-impact intervention. It benefits trainee well-being, satisfaction, workflow, and future patient care. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mandated in July 2019 that all residency programs provide adequate lactation facilities – including refrigeration capabilities and proximity for safe patient care. However, to our knowledge, rates of compliance with this new policy and citation for noncompliance have yet to be seen. Regardless, facilities alone are not enough. Residency programs should develop and enforce formal lactation policies.

Several institutions have successfully piloted such policies in recent years. One in particular from the University of Michigan’s surgery residency program inspired the development of a lactation policy within the internal medicine residency at our institution. These policies designate appropriate spaces at each clinical rotation site, clarify that residents are encouraged to take pumping breaks as needed – in coordination with clinical teams so as not to compromise patient care – and communicate support from supervisors.

Our program also established an informal peer mentoring program. Residents with experience pumping at work pair up with newer trainees. The policy benefits residents who wish to chestfeed or breastfeed, normalizes lactation, and empowers trainees by diminishing the need to ask for individual accommodations. It also costs the program nothing.

As more women enter medicine and more trainees become parents during residency, the need for support in this area will only continue to grow. The widespread lack of such resources, and the fact that clean and private facilities are only now being mandated, is symbolic. If even this basic need is rarely acknowledged or met, what other resident needs are being neglected?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As working mothers with babies in tow when the COVID-19 crisis struck, countless uncertainties threatened our already precarious work-life balance. We suddenly had many questions:

“If my daycare closes, what will I do for childcare?”

“How do I navigate diaper changes, feedings, and naps with my hectic remote work schedule?”

“If I’m constantly interrupted during the day, should I skip sleep to catch up on work and not let my colleagues down?”

As professionals who work closely with medical trainees, we knew our parenting dilemmas were being experienced even more acutely by our frontline worker colleagues.

Medical training is an increasingly common time to start a family. In a recent study, 34% of trainees in Harvard-affiliated residency programs became parents during training, and another 52% planned to do so. Trainees have higher breastfeeding initiation rates but lower continuation rates than the general population. Early nursing cessation among trainees is well documented nationally and is most often attributed to work-related barriers. These barriers range from insufficient time and limited access to facilities to a lack of support and discrimination by supervisors and peers.

This trend does not discriminate by specialty. Even among training programs known to be “family friendly,” the average duration of nursing is just 4.5 months. Residents of color are disproportionately affected by inadequate support. Studies show that Black parents breastfeed at lower rates than White parents. This has been largely attributed to structural racism and implicit bias, such as Black parents receiving less assistance initiating nursing after delivery. Adequate lactation support and inclusivity are also lacking for transgender parents who choose to breastfeed or chestfeed.

The very nature of residency training, which includes shifts that can span more than 24 hours, conflicts with many health-promoting behaviors like sleeping and eating well. However, its interference with lactation is correlated with gender. Women are disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of unmet lactation goals. These include work-life imbalance, career dissatisfaction, and negative emotions. In a study of pediatric residents, one in four did not achieve their breastfeeding goals. Respondents reported feeling “sad, devastated, defeated, disappointed, guilty, embarrassed, frustrated, angry, like a failure, and inadequate.” Among physician mothers more broadly, discrimination related to pregnancy, parental leave, and nursing is associated with higher self-reported burnout.

Navigating nursing during residency training has more than just emotional and psychological consequences – it also has professional ones. Pursuing personal lactation goals can delay residency program completion and board certification, influence specialty selection, negatively impact research productivity, impede career advancement, and lead to misgivings about career choice.

Trainees and their families are not the only ones harmed by inadequate support in residency programs. Patients and their families are affected, too. Research suggests that physicians’ personal breastfeeding practices affect the advice they give to patients. Those who receive lactation support are more likely to help patients meet their own goals. In the previously mentioned study of pediatric residents, more than 90% of the 400 respondents said their own or their partner’s nursing experience affected their interaction with lactating patients in their clinic or hospital.

Increased lactation support is a straightforward, low-cost, high-impact intervention. It benefits trainee well-being, satisfaction, workflow, and future patient care. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mandated in July 2019 that all residency programs provide adequate lactation facilities – including refrigeration capabilities and proximity for safe patient care. However, to our knowledge, rates of compliance with this new policy and citation for noncompliance have yet to be seen. Regardless, facilities alone are not enough. Residency programs should develop and enforce formal lactation policies.

Several institutions have successfully piloted such policies in recent years. One in particular from the University of Michigan’s surgery residency program inspired the development of a lactation policy within the internal medicine residency at our institution. These policies designate appropriate spaces at each clinical rotation site, clarify that residents are encouraged to take pumping breaks as needed – in coordination with clinical teams so as not to compromise patient care – and communicate support from supervisors.

Our program also established an informal peer mentoring program. Residents with experience pumping at work pair up with newer trainees. The policy benefits residents who wish to chestfeed or breastfeed, normalizes lactation, and empowers trainees by diminishing the need to ask for individual accommodations. It also costs the program nothing.

As more women enter medicine and more trainees become parents during residency, the need for support in this area will only continue to grow. The widespread lack of such resources, and the fact that clean and private facilities are only now being mandated, is symbolic. If even this basic need is rarely acknowledged or met, what other resident needs are being neglected?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As working mothers with babies in tow when the COVID-19 crisis struck, countless uncertainties threatened our already precarious work-life balance. We suddenly had many questions:

“If my daycare closes, what will I do for childcare?”

“How do I navigate diaper changes, feedings, and naps with my hectic remote work schedule?”

“If I’m constantly interrupted during the day, should I skip sleep to catch up on work and not let my colleagues down?”

As professionals who work closely with medical trainees, we knew our parenting dilemmas were being experienced even more acutely by our frontline worker colleagues.

Medical training is an increasingly common time to start a family. In a recent study, 34% of trainees in Harvard-affiliated residency programs became parents during training, and another 52% planned to do so. Trainees have higher breastfeeding initiation rates but lower continuation rates than the general population. Early nursing cessation among trainees is well documented nationally and is most often attributed to work-related barriers. These barriers range from insufficient time and limited access to facilities to a lack of support and discrimination by supervisors and peers.

This trend does not discriminate by specialty. Even among training programs known to be “family friendly,” the average duration of nursing is just 4.5 months. Residents of color are disproportionately affected by inadequate support. Studies show that Black parents breastfeed at lower rates than White parents. This has been largely attributed to structural racism and implicit bias, such as Black parents receiving less assistance initiating nursing after delivery. Adequate lactation support and inclusivity are also lacking for transgender parents who choose to breastfeed or chestfeed.

The very nature of residency training, which includes shifts that can span more than 24 hours, conflicts with many health-promoting behaviors like sleeping and eating well. However, its interference with lactation is correlated with gender. Women are disproportionately affected by the negative outcomes of unmet lactation goals. These include work-life imbalance, career dissatisfaction, and negative emotions. In a study of pediatric residents, one in four did not achieve their breastfeeding goals. Respondents reported feeling “sad, devastated, defeated, disappointed, guilty, embarrassed, frustrated, angry, like a failure, and inadequate.” Among physician mothers more broadly, discrimination related to pregnancy, parental leave, and nursing is associated with higher self-reported burnout.

Navigating nursing during residency training has more than just emotional and psychological consequences – it also has professional ones. Pursuing personal lactation goals can delay residency program completion and board certification, influence specialty selection, negatively impact research productivity, impede career advancement, and lead to misgivings about career choice.

Trainees and their families are not the only ones harmed by inadequate support in residency programs. Patients and their families are affected, too. Research suggests that physicians’ personal breastfeeding practices affect the advice they give to patients. Those who receive lactation support are more likely to help patients meet their own goals. In the previously mentioned study of pediatric residents, more than 90% of the 400 respondents said their own or their partner’s nursing experience affected their interaction with lactating patients in their clinic or hospital.

Increased lactation support is a straightforward, low-cost, high-impact intervention. It benefits trainee well-being, satisfaction, workflow, and future patient care. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mandated in July 2019 that all residency programs provide adequate lactation facilities – including refrigeration capabilities and proximity for safe patient care. However, to our knowledge, rates of compliance with this new policy and citation for noncompliance have yet to be seen. Regardless, facilities alone are not enough. Residency programs should develop and enforce formal lactation policies.

Several institutions have successfully piloted such policies in recent years. One in particular from the University of Michigan’s surgery residency program inspired the development of a lactation policy within the internal medicine residency at our institution. These policies designate appropriate spaces at each clinical rotation site, clarify that residents are encouraged to take pumping breaks as needed – in coordination with clinical teams so as not to compromise patient care – and communicate support from supervisors.

Our program also established an informal peer mentoring program. Residents with experience pumping at work pair up with newer trainees. The policy benefits residents who wish to chestfeed or breastfeed, normalizes lactation, and empowers trainees by diminishing the need to ask for individual accommodations. It also costs the program nothing.

As more women enter medicine and more trainees become parents during residency, the need for support in this area will only continue to grow. The widespread lack of such resources, and the fact that clean and private facilities are only now being mandated, is symbolic. If even this basic need is rarely acknowledged or met, what other resident needs are being neglected?

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A sizzling hybrid meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons

The 47th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), like so many things in our modern world, endured many changes and had to stay nimble and evolve to changing times. In the end, however, SGS was able to adapt and succeed, just like a skilled gynecologic surgeon in the operating room, to deliver a fresh new type of meeting.

When we chose the meeting theme, “Working together: How collaboration enables us to better help our patients,” we anticipated a meeting discussing medical colleagues and consultants. In our forever-changed world, we knew we needed to reinterpret this to a broader social context. Our special lectures and panel discussions sought to open attendees’ eyes to disparities in health care for people of color and women.

While we highlighted the realities faced by colleagues in medicine, the topics addressed also were designed to grow awareness about struggles our patients encounter as well. Social disparities are sobering, long-standing, and sometimes require creative collaborations to achieve successful outcomes for all patients. The faculty of one of our postgraduate courses reviews in this special 2-part section to

The meeting also kicked off with a postgraduate course on fibroid management, with workshops on harnessing the power of social media and lessons on leadership from a female Fortune 500 CEO, Lori Ryerkerk, offered as well. As the scientific program launched, we were once again treated to strong science on gynecologic surgery, with only a small dip in abstract submissions, despite the challenges of research during a pandemic. Mark Walters, MD, gave the inaugural lecture in his name on the crucial topic of surgical education and teaching. We also heard a special report from the SGS SOCOVID research group, led by Dr. Rosanne Kho, on gynecologic surgery during the pandemic. We also convened a virtual panel for our hybrid attendees on the benefits to patients of a multidisciplinary approach to gynecologic surgery, presented here by Cecile Ferrando, MD.

As our practices continue to grow and evolve, the introduction of innovative technologies can pose a new challenge, as Miles Murphy, MD, and members of the panel on novel gynecologic office procedures will present in this series next month.

The TeLinde keynote speaker was Janet Dombrowski, who works as a coach for many surgeons in various disciplines across the country. She spoke to the resilience gained through community and collaboration.

While our meeting theme dated to the “before” pandemic era, those who were able to be in attendance in person can attest to the value we can all place now on community and personal interactions. With experience strengthened by science, I hope this meeting summary serves to highlight the many ways in which we can collaborate to improve outcomes for ourselves in medicine and for patients.

The 47th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), like so many things in our modern world, endured many changes and had to stay nimble and evolve to changing times. In the end, however, SGS was able to adapt and succeed, just like a skilled gynecologic surgeon in the operating room, to deliver a fresh new type of meeting.

When we chose the meeting theme, “Working together: How collaboration enables us to better help our patients,” we anticipated a meeting discussing medical colleagues and consultants. In our forever-changed world, we knew we needed to reinterpret this to a broader social context. Our special lectures and panel discussions sought to open attendees’ eyes to disparities in health care for people of color and women.

While we highlighted the realities faced by colleagues in medicine, the topics addressed also were designed to grow awareness about struggles our patients encounter as well. Social disparities are sobering, long-standing, and sometimes require creative collaborations to achieve successful outcomes for all patients. The faculty of one of our postgraduate courses reviews in this special 2-part section to

The meeting also kicked off with a postgraduate course on fibroid management, with workshops on harnessing the power of social media and lessons on leadership from a female Fortune 500 CEO, Lori Ryerkerk, offered as well. As the scientific program launched, we were once again treated to strong science on gynecologic surgery, with only a small dip in abstract submissions, despite the challenges of research during a pandemic. Mark Walters, MD, gave the inaugural lecture in his name on the crucial topic of surgical education and teaching. We also heard a special report from the SGS SOCOVID research group, led by Dr. Rosanne Kho, on gynecologic surgery during the pandemic. We also convened a virtual panel for our hybrid attendees on the benefits to patients of a multidisciplinary approach to gynecologic surgery, presented here by Cecile Ferrando, MD.

As our practices continue to grow and evolve, the introduction of innovative technologies can pose a new challenge, as Miles Murphy, MD, and members of the panel on novel gynecologic office procedures will present in this series next month.

The TeLinde keynote speaker was Janet Dombrowski, who works as a coach for many surgeons in various disciplines across the country. She spoke to the resilience gained through community and collaboration.

While our meeting theme dated to the “before” pandemic era, those who were able to be in attendance in person can attest to the value we can all place now on community and personal interactions. With experience strengthened by science, I hope this meeting summary serves to highlight the many ways in which we can collaborate to improve outcomes for ourselves in medicine and for patients.

The 47th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), like so many things in our modern world, endured many changes and had to stay nimble and evolve to changing times. In the end, however, SGS was able to adapt and succeed, just like a skilled gynecologic surgeon in the operating room, to deliver a fresh new type of meeting.

When we chose the meeting theme, “Working together: How collaboration enables us to better help our patients,” we anticipated a meeting discussing medical colleagues and consultants. In our forever-changed world, we knew we needed to reinterpret this to a broader social context. Our special lectures and panel discussions sought to open attendees’ eyes to disparities in health care for people of color and women.

While we highlighted the realities faced by colleagues in medicine, the topics addressed also were designed to grow awareness about struggles our patients encounter as well. Social disparities are sobering, long-standing, and sometimes require creative collaborations to achieve successful outcomes for all patients. The faculty of one of our postgraduate courses reviews in this special 2-part section to

The meeting also kicked off with a postgraduate course on fibroid management, with workshops on harnessing the power of social media and lessons on leadership from a female Fortune 500 CEO, Lori Ryerkerk, offered as well. As the scientific program launched, we were once again treated to strong science on gynecologic surgery, with only a small dip in abstract submissions, despite the challenges of research during a pandemic. Mark Walters, MD, gave the inaugural lecture in his name on the crucial topic of surgical education and teaching. We also heard a special report from the SGS SOCOVID research group, led by Dr. Rosanne Kho, on gynecologic surgery during the pandemic. We also convened a virtual panel for our hybrid attendees on the benefits to patients of a multidisciplinary approach to gynecologic surgery, presented here by Cecile Ferrando, MD.

As our practices continue to grow and evolve, the introduction of innovative technologies can pose a new challenge, as Miles Murphy, MD, and members of the panel on novel gynecologic office procedures will present in this series next month.

The TeLinde keynote speaker was Janet Dombrowski, who works as a coach for many surgeons in various disciplines across the country. She spoke to the resilience gained through community and collaboration.

While our meeting theme dated to the “before” pandemic era, those who were able to be in attendance in person can attest to the value we can all place now on community and personal interactions. With experience strengthened by science, I hope this meeting summary serves to highlight the many ways in which we can collaborate to improve outcomes for ourselves in medicine and for patients.

Physicians wearing white coats rated more experienced

Physicians wearing white coats were rated as significantly more experienced and professional than peers wearing casual attire. Regardless of their attire, however, female physicians were more likely to be judged as appearing less professional and were more likely to be misidentified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses, found research published in JAMA Network Open.

“A white coat with scrubs attire was most preferred for surgeons (mean preference index, 1.3), whereas a white coat with business attire was preferred for family physicians and dermatologists (mean preference indexes, 1.6 and 1.2, respectively; P < .001),” Helen Xun, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote. “A male model wearing business inner wear with a white coat, fleece jacket, or softshell jacket was perceived as significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire (mean professionalism score: male, 65.8; female, 56.2; mean difference in professionalism score: white coat, 12.06; fleece, 7.89; softshell, 8.82; P < .001). ... A male model wearing hospital scrubs or fashion scrubs alone was also perceived as more professional than a female model in the same attire.”

While casual attire, such as fleece or softshell jackets emblazoned with the names of the institution and wearer, has become more popular attire for physicians in recent years, the researchers noted theirs is the first published research to identify associations between gender, attire, and how people distinguish between various health care roles. The study authors launched their web-based survey from May to June 2020 and asked people aged 18 years and older to rate a series of photographs of deidentified models wearing health care attire. Inner wear choices were business attire versus scrubs with and without outer wear options of a long white coat, gray fleece jacket, or black softshell jackets. Survey respondents ranked the images on a 6-point Likert scale with 1 being the least experienced, professional, and friendly and 6 being the most experienced, professional, and friendly. Survey respondents also viewed individual images of male or female models and were asked to rate their professionalism on a scale of 0-100 – with 100 as the “most professional” as well as to identify their profession as either physician, surgeon, nurse, medical technician, or physician assistant.

The study team included 487 (93.3%) of 522 completed surveys in their analyses. Respondents’ mean age was 36.2 years; 260 (53.4%) were female; 372 (76.4%) were White; 33 (6.8%) were Black or African American. Younger respondents and those living in the Western United States who had more exposure to physician casual attire appeared more accepting of it, the authors wrote.

“I remember attending my white-coat ceremony as a medical student, and the symbolism of it all representing me entering the profession. It felt very emotional and heavy and I felt very proud to be there. I also remember taking a ‘selfie’ in my long white coat as a doctor for the first time before my first shift as a resident. But, I’ve also been wearing that same white coat, and a large badge with a ‘DOCTOR’ label on it, and been mistaken by a patient or parent for something other than the physician,” Alexandra M. Sims, a pediatrician and health equity researcher in Cincinnati, said in an interview. “So, I’d really hope that the take-home here is not simply that we must wear our white coats to be considered more professional. I think we have to unpack and dismantle how we’ve even built this notion of ‘professionalism’ in the first place. Women, people of color, and other marginalized groups were certainly not a part of the defining, but we must be a part of the reimagining of an equitable health care profession in this new era.”

As sartorial trends usher in more casual attire, clinicians should redouble efforts to build rapport and enhance communication with patients, such as clarifying team members’ roles when introducing themselves. Dr. Xun and coauthors noted that addressing gender bias is important for all clinicians – not just women – and point to the need for institutional and organizational support for disciplines where gender bias is “especially prevalent,” like surgery. “This responsibility should not be undertaken only by the individuals that experience the biases, which may result in additional cumulative career disadvantages. The promotion of equality and diversity begins with recognition, characterization, and evidence-supported interventions and is a community operation,” Dr. Xun and colleagues concluded.

“I do not equate attire to professionalism or experience, nor is it connected to my satisfaction with the physician. For myself and my daughter, it is the experience of care that ultimately influences our perceptions regarding the professionalism of the physician,” Hala H. Durrah, MTA, parent to a chronically ill child with special health care needs and a Patient and Family Engagement Consultant, said in an interview. “My respect for a physician will ultimately be determined by how my daughter and I were treated, not just from a clinical perspective, but how we felt during those interactions.”

Physicians wearing white coats were rated as significantly more experienced and professional than peers wearing casual attire. Regardless of their attire, however, female physicians were more likely to be judged as appearing less professional and were more likely to be misidentified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses, found research published in JAMA Network Open.

“A white coat with scrubs attire was most preferred for surgeons (mean preference index, 1.3), whereas a white coat with business attire was preferred for family physicians and dermatologists (mean preference indexes, 1.6 and 1.2, respectively; P < .001),” Helen Xun, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote. “A male model wearing business inner wear with a white coat, fleece jacket, or softshell jacket was perceived as significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire (mean professionalism score: male, 65.8; female, 56.2; mean difference in professionalism score: white coat, 12.06; fleece, 7.89; softshell, 8.82; P < .001). ... A male model wearing hospital scrubs or fashion scrubs alone was also perceived as more professional than a female model in the same attire.”

While casual attire, such as fleece or softshell jackets emblazoned with the names of the institution and wearer, has become more popular attire for physicians in recent years, the researchers noted theirs is the first published research to identify associations between gender, attire, and how people distinguish between various health care roles. The study authors launched their web-based survey from May to June 2020 and asked people aged 18 years and older to rate a series of photographs of deidentified models wearing health care attire. Inner wear choices were business attire versus scrubs with and without outer wear options of a long white coat, gray fleece jacket, or black softshell jackets. Survey respondents ranked the images on a 6-point Likert scale with 1 being the least experienced, professional, and friendly and 6 being the most experienced, professional, and friendly. Survey respondents also viewed individual images of male or female models and were asked to rate their professionalism on a scale of 0-100 – with 100 as the “most professional” as well as to identify their profession as either physician, surgeon, nurse, medical technician, or physician assistant.

The study team included 487 (93.3%) of 522 completed surveys in their analyses. Respondents’ mean age was 36.2 years; 260 (53.4%) were female; 372 (76.4%) were White; 33 (6.8%) were Black or African American. Younger respondents and those living in the Western United States who had more exposure to physician casual attire appeared more accepting of it, the authors wrote.

“I remember attending my white-coat ceremony as a medical student, and the symbolism of it all representing me entering the profession. It felt very emotional and heavy and I felt very proud to be there. I also remember taking a ‘selfie’ in my long white coat as a doctor for the first time before my first shift as a resident. But, I’ve also been wearing that same white coat, and a large badge with a ‘DOCTOR’ label on it, and been mistaken by a patient or parent for something other than the physician,” Alexandra M. Sims, a pediatrician and health equity researcher in Cincinnati, said in an interview. “So, I’d really hope that the take-home here is not simply that we must wear our white coats to be considered more professional. I think we have to unpack and dismantle how we’ve even built this notion of ‘professionalism’ in the first place. Women, people of color, and other marginalized groups were certainly not a part of the defining, but we must be a part of the reimagining of an equitable health care profession in this new era.”

As sartorial trends usher in more casual attire, clinicians should redouble efforts to build rapport and enhance communication with patients, such as clarifying team members’ roles when introducing themselves. Dr. Xun and coauthors noted that addressing gender bias is important for all clinicians – not just women – and point to the need for institutional and organizational support for disciplines where gender bias is “especially prevalent,” like surgery. “This responsibility should not be undertaken only by the individuals that experience the biases, which may result in additional cumulative career disadvantages. The promotion of equality and diversity begins with recognition, characterization, and evidence-supported interventions and is a community operation,” Dr. Xun and colleagues concluded.

“I do not equate attire to professionalism or experience, nor is it connected to my satisfaction with the physician. For myself and my daughter, it is the experience of care that ultimately influences our perceptions regarding the professionalism of the physician,” Hala H. Durrah, MTA, parent to a chronically ill child with special health care needs and a Patient and Family Engagement Consultant, said in an interview. “My respect for a physician will ultimately be determined by how my daughter and I were treated, not just from a clinical perspective, but how we felt during those interactions.”

Physicians wearing white coats were rated as significantly more experienced and professional than peers wearing casual attire. Regardless of their attire, however, female physicians were more likely to be judged as appearing less professional and were more likely to be misidentified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses, found research published in JAMA Network Open.

“A white coat with scrubs attire was most preferred for surgeons (mean preference index, 1.3), whereas a white coat with business attire was preferred for family physicians and dermatologists (mean preference indexes, 1.6 and 1.2, respectively; P < .001),” Helen Xun, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues wrote. “A male model wearing business inner wear with a white coat, fleece jacket, or softshell jacket was perceived as significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire (mean professionalism score: male, 65.8; female, 56.2; mean difference in professionalism score: white coat, 12.06; fleece, 7.89; softshell, 8.82; P < .001). ... A male model wearing hospital scrubs or fashion scrubs alone was also perceived as more professional than a female model in the same attire.”

While casual attire, such as fleece or softshell jackets emblazoned with the names of the institution and wearer, has become more popular attire for physicians in recent years, the researchers noted theirs is the first published research to identify associations between gender, attire, and how people distinguish between various health care roles. The study authors launched their web-based survey from May to June 2020 and asked people aged 18 years and older to rate a series of photographs of deidentified models wearing health care attire. Inner wear choices were business attire versus scrubs with and without outer wear options of a long white coat, gray fleece jacket, or black softshell jackets. Survey respondents ranked the images on a 6-point Likert scale with 1 being the least experienced, professional, and friendly and 6 being the most experienced, professional, and friendly. Survey respondents also viewed individual images of male or female models and were asked to rate their professionalism on a scale of 0-100 – with 100 as the “most professional” as well as to identify their profession as either physician, surgeon, nurse, medical technician, or physician assistant.

The study team included 487 (93.3%) of 522 completed surveys in their analyses. Respondents’ mean age was 36.2 years; 260 (53.4%) were female; 372 (76.4%) were White; 33 (6.8%) were Black or African American. Younger respondents and those living in the Western United States who had more exposure to physician casual attire appeared more accepting of it, the authors wrote.

“I remember attending my white-coat ceremony as a medical student, and the symbolism of it all representing me entering the profession. It felt very emotional and heavy and I felt very proud to be there. I also remember taking a ‘selfie’ in my long white coat as a doctor for the first time before my first shift as a resident. But, I’ve also been wearing that same white coat, and a large badge with a ‘DOCTOR’ label on it, and been mistaken by a patient or parent for something other than the physician,” Alexandra M. Sims, a pediatrician and health equity researcher in Cincinnati, said in an interview. “So, I’d really hope that the take-home here is not simply that we must wear our white coats to be considered more professional. I think we have to unpack and dismantle how we’ve even built this notion of ‘professionalism’ in the first place. Women, people of color, and other marginalized groups were certainly not a part of the defining, but we must be a part of the reimagining of an equitable health care profession in this new era.”

As sartorial trends usher in more casual attire, clinicians should redouble efforts to build rapport and enhance communication with patients, such as clarifying team members’ roles when introducing themselves. Dr. Xun and coauthors noted that addressing gender bias is important for all clinicians – not just women – and point to the need for institutional and organizational support for disciplines where gender bias is “especially prevalent,” like surgery. “This responsibility should not be undertaken only by the individuals that experience the biases, which may result in additional cumulative career disadvantages. The promotion of equality and diversity begins with recognition, characterization, and evidence-supported interventions and is a community operation,” Dr. Xun and colleagues concluded.

“I do not equate attire to professionalism or experience, nor is it connected to my satisfaction with the physician. For myself and my daughter, it is the experience of care that ultimately influences our perceptions regarding the professionalism of the physician,” Hala H. Durrah, MTA, parent to a chronically ill child with special health care needs and a Patient and Family Engagement Consultant, said in an interview. “My respect for a physician will ultimately be determined by how my daughter and I were treated, not just from a clinical perspective, but how we felt during those interactions.”

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

COVID-19 leaves wake of medical debt among U.S. adults

Despite the passage of four major relief bills in 2020 and 2021 and federal efforts to offset pandemic- and job-related coverage loss, many people continued to face financial challenges, especially those with a low income and those who are Black or Latino.

The survey, which included responses from 5,450 adults, revealed that 10% of adults aged 19-64 were uninsured during the first half of 2021, a rate lower than what was recorded in 2020 and 2019 in both federal and private surveys. However, uninsured rates were highest among those with low income, those younger than 50 years old, and Black and Latino adults.

For most adults who lost employee health insurance, the coverage gap was relatively brief, with 54% saying their coverage gap lasted 3-4 months. Only 16% of adults said coverage gaps lasted a year or longer.

“The good news is that this survey is suggesting that the coverage losses during the pandemic may have been offset by federal efforts to help people get and maintain health insurance coverage,” lead author Sara Collins, PhD, Commonwealth Fund vice president for health care coverage, access, and tracking, said in an interview.

“The bad news is that a third of Americans continue to struggle with medical bills and medical debt, even among those who have health insurance coverage,” Dr. Collins added.

Indeed, the survey found that about one-third of insured adults reported a medical bill problem or that they were paying off medical debt, as did approximately half of those who were uninsured. Medical debt caused 35% of respondents to use up most or all of their savings to pay it off.

Meanwhile, 27% of adults said medical bills left them unable to pay for necessities such as food, heat, or rent. What surprised Dr. Collins was that 43% of adults said they received a lower credit rating as a result of their medical debt, and 35% said they had taken on more credit card debt to pay off these bills.

“The fact that it’s bleeding over into people’s financial security in terms of their credit scores, I think is something that really needs to be looked at by policymakers,” Dr. Collins said.

When analyzed by race/ethnicity, the researchers found that 55% of Black adults and 44% of Latino/Hispanic adults reported medical bills and debt problems, compared with 32% of White adults. In addition, 47% of those living below the poverty line also reported problems with medical bills.

According to the survey, 45% of respondents were directly affected by the pandemic in at least one of three ways – testing positive or getting sick from COVID-19, losing income, or losing employer coverage – with Black and Latinx adults and those with lower incomes at greater risk.

George Abraham, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, said the Commonwealth Fund’s findings were not surprising because it has always been known that underrepresented populations struggle for access to care because of socioeconomic factors. He said these populations were more vulnerable in terms of more severe infections and disease burden during the pandemic.

“[This study] validates what primary care physicians have been saying all along in regard to our patients’ access to care and their ability to cover health care costs,” said Dr. Abraham, who was not involved with the study. “This will hopefully be an eye-opener and wake-up call that reiterates that we still do not have equitable access to care and vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected.”

He believes that, although people are insured, many of them may contend with medical debt when they fall ill because they can’t afford the premiums.

“Even though they may have been registered for health coverage, they may not have active coverage at the time of illness simply because they weren’t able to make their last premium payments because they’ve been down, because they lost their job, or whatever else,” Dr. Abraham explained. “On paper, they appear to have health care coverage. But in reality, clearly, that coverage does not match their needs or it’s not affordable.”

For Dr. Abraham, the study emphasizes the need to continue support for health care reform, including pricing it so that insurance is available for those with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, Washington, said high-deductible health plans need to be “reined in” because they can lead to greater debt, particularly among vulnerable populations.

“Hopefully this will encourage policymakers to look more closely at the problem of medical debt as a contributing factor to financial instability,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “Federal relief is important, so is expanding access to comprehensive, affordable health care coverage.”

Dr. Collins said there should also be a way to raise awareness of the health care marketplace and coverage options so that people have an easier time getting insured.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the passage of four major relief bills in 2020 and 2021 and federal efforts to offset pandemic- and job-related coverage loss, many people continued to face financial challenges, especially those with a low income and those who are Black or Latino.

The survey, which included responses from 5,450 adults, revealed that 10% of adults aged 19-64 were uninsured during the first half of 2021, a rate lower than what was recorded in 2020 and 2019 in both federal and private surveys. However, uninsured rates were highest among those with low income, those younger than 50 years old, and Black and Latino adults.

For most adults who lost employee health insurance, the coverage gap was relatively brief, with 54% saying their coverage gap lasted 3-4 months. Only 16% of adults said coverage gaps lasted a year or longer.

“The good news is that this survey is suggesting that the coverage losses during the pandemic may have been offset by federal efforts to help people get and maintain health insurance coverage,” lead author Sara Collins, PhD, Commonwealth Fund vice president for health care coverage, access, and tracking, said in an interview.

“The bad news is that a third of Americans continue to struggle with medical bills and medical debt, even among those who have health insurance coverage,” Dr. Collins added.

Indeed, the survey found that about one-third of insured adults reported a medical bill problem or that they were paying off medical debt, as did approximately half of those who were uninsured. Medical debt caused 35% of respondents to use up most or all of their savings to pay it off.

Meanwhile, 27% of adults said medical bills left them unable to pay for necessities such as food, heat, or rent. What surprised Dr. Collins was that 43% of adults said they received a lower credit rating as a result of their medical debt, and 35% said they had taken on more credit card debt to pay off these bills.

“The fact that it’s bleeding over into people’s financial security in terms of their credit scores, I think is something that really needs to be looked at by policymakers,” Dr. Collins said.

When analyzed by race/ethnicity, the researchers found that 55% of Black adults and 44% of Latino/Hispanic adults reported medical bills and debt problems, compared with 32% of White adults. In addition, 47% of those living below the poverty line also reported problems with medical bills.

According to the survey, 45% of respondents were directly affected by the pandemic in at least one of three ways – testing positive or getting sick from COVID-19, losing income, or losing employer coverage – with Black and Latinx adults and those with lower incomes at greater risk.