User login

I’m a physician battling long COVID. I can assure you it’s real

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Has the pandemic affected babies’ brain development?

There’s some good overall news in a large analysis that looked at whether a mother’s COVID-19 infection or birth during the pandemic could affect a baby’s brain development.

Researchers studied 21,419 infants who had neurodevelopmental screening during the pandemic (from January 2020 to January 2021) and compared them with babies born before the pandemic (2015-2019).

They found in an analysis of eight studies that, generally, brain development in infants ages 6-12 months old was not changed by COVID-19.

Communication skill scores lower than prepandemic

However, one area did see a significant difference when they looked at answers to the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 3rd edition (ASQ-3): Scores were lower in communication skills.

Compared with the prepandemic babies, the pandemic group of babies was more likely to have communication impairment (odds were 1.7 times higher).

Additionally, mothers’ SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with significant differences in any neurodevelopment sector in offspring, with one exception: Odds were 3.5 times higher for fine motor impairment in the pandemic baby group.

The babies in this study were either exposed in the womb to the SARS-CoV-2 infection or screened during the pandemic regardless of whether they were exposed to the virus.

The study, led by Kamran Hessami, MD, with the Maternal Fetal Care Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, was published in JAMA Network Open.

Potential reasons for lower communication skills

The study points to some factors of the pandemic that may be tied to impaired communication skills.

“Higher levels of COVID-19–related stress were reported for both mothers and fathers of infants aged 0-6 months and were associated with insensitive parenting practices, including decreased emotional responsiveness in only mothers, which could lessen the reciprocal exchanges that support language development in early childhood,” they write. “Additionally, opportunities to promote language and social development through new experiences outside the home, including visits with extended family and friends or attendance at a child care center, were lessened for many during the pandemic.”

Viviana M. Fajardo Martinez, MD, with neonatal/perinatal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, Health, told this publication her team is also studying child development before and after the pandemic over a 3-year period, and delayed communication skills is something she is seeing in clinic there.

She says some parents have been concerned, saying their babies aren’t talking enough or are behind in vocabulary.

Babies can catch up after 12 months

One thing she tells parents is that babies who are a bit delayed at 12 months can catch up.

Up to 18 months, they can catch up, she said, adding that they can be reevaluated then for improvement. If, at that point, the baby is not catching up, “that’s when we refer for early intervention,” she said.

Dr. Martinez also tells parents concerned about their infant’s communication skills that it’s important to talk, read, and sing to their child. She said amid pandemic stress, corners may have been cut in asking children to use language skills.

For instance, if a child points to an apple, a stressed parent may just give the child the apple instead of asking the child to request it by name and repeat the word several times.

She also said a limitation of this study is the use of the ASQ-3 questionnaire, which is filled out by parents. Answers are subjective, she notes, and sometimes differ between one child’s two parents. The questionnaire was commonly used during the pandemic because a more objective, professional evaluation has been more difficult.

However, a measure like the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Screening Test adds objectivity and will likely give a better picture as research progresses, Dr. Martinez said.

Some information missing

Andréane Lavallée, PhD, and Dani Dumitriu, MD, PhD, both with the department of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, write in an invited commentary that the overall positive message of the study “should not make researchers complacent” and results should be viewed with caution.

They point out that the precise effects of this novel virus are still unclear and the age group and variables studied may not tell the whole story.

“It should be noted that this systematic review did not consider timing of exposure during pregnancy, maternal infection severity, or exposure to various SARS-CoV-2 variants – all factors that could eventually be proven to contribute to subtle adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they write.

Additionally, past pandemics “such as the 1918 Spanish flu, 1964 rubella, and 2009 H1N1” have taught researchers to watch for increases in diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia in subsequent years.

“ASD is generally diagnosed at age 3-5 years (and often not until early teens), while schizophrenia is generally diagnosed in mid-to-late 20s,” the editorialists point out. The authors agree and emphasize the need for long-term studies.

Authors report no relevant financial relationships. Editorialist Dr. Dumitriu reports grants from National Institute of Mental Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation; and has received gift funds from Einhorn Collaborative during the conduct of the study to the Nurture Science Program, for which Dr Dumitriu serves as director. Dr. Dumitriu received personal fees from Medela outside the submitted work; and is the corresponding author for one of the studies (Shuffrey et al., 2022) included in the systematic review conducted by Dr. Hessami et al. Dr. Lavallée reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Martinez reports no relevant financial relationships.

There’s some good overall news in a large analysis that looked at whether a mother’s COVID-19 infection or birth during the pandemic could affect a baby’s brain development.

Researchers studied 21,419 infants who had neurodevelopmental screening during the pandemic (from January 2020 to January 2021) and compared them with babies born before the pandemic (2015-2019).

They found in an analysis of eight studies that, generally, brain development in infants ages 6-12 months old was not changed by COVID-19.

Communication skill scores lower than prepandemic

However, one area did see a significant difference when they looked at answers to the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 3rd edition (ASQ-3): Scores were lower in communication skills.

Compared with the prepandemic babies, the pandemic group of babies was more likely to have communication impairment (odds were 1.7 times higher).

Additionally, mothers’ SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with significant differences in any neurodevelopment sector in offspring, with one exception: Odds were 3.5 times higher for fine motor impairment in the pandemic baby group.

The babies in this study were either exposed in the womb to the SARS-CoV-2 infection or screened during the pandemic regardless of whether they were exposed to the virus.

The study, led by Kamran Hessami, MD, with the Maternal Fetal Care Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, was published in JAMA Network Open.

Potential reasons for lower communication skills

The study points to some factors of the pandemic that may be tied to impaired communication skills.

“Higher levels of COVID-19–related stress were reported for both mothers and fathers of infants aged 0-6 months and were associated with insensitive parenting practices, including decreased emotional responsiveness in only mothers, which could lessen the reciprocal exchanges that support language development in early childhood,” they write. “Additionally, opportunities to promote language and social development through new experiences outside the home, including visits with extended family and friends or attendance at a child care center, were lessened for many during the pandemic.”

Viviana M. Fajardo Martinez, MD, with neonatal/perinatal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, Health, told this publication her team is also studying child development before and after the pandemic over a 3-year period, and delayed communication skills is something she is seeing in clinic there.

She says some parents have been concerned, saying their babies aren’t talking enough or are behind in vocabulary.

Babies can catch up after 12 months

One thing she tells parents is that babies who are a bit delayed at 12 months can catch up.

Up to 18 months, they can catch up, she said, adding that they can be reevaluated then for improvement. If, at that point, the baby is not catching up, “that’s when we refer for early intervention,” she said.

Dr. Martinez also tells parents concerned about their infant’s communication skills that it’s important to talk, read, and sing to their child. She said amid pandemic stress, corners may have been cut in asking children to use language skills.

For instance, if a child points to an apple, a stressed parent may just give the child the apple instead of asking the child to request it by name and repeat the word several times.

She also said a limitation of this study is the use of the ASQ-3 questionnaire, which is filled out by parents. Answers are subjective, she notes, and sometimes differ between one child’s two parents. The questionnaire was commonly used during the pandemic because a more objective, professional evaluation has been more difficult.

However, a measure like the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Screening Test adds objectivity and will likely give a better picture as research progresses, Dr. Martinez said.

Some information missing

Andréane Lavallée, PhD, and Dani Dumitriu, MD, PhD, both with the department of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, write in an invited commentary that the overall positive message of the study “should not make researchers complacent” and results should be viewed with caution.

They point out that the precise effects of this novel virus are still unclear and the age group and variables studied may not tell the whole story.

“It should be noted that this systematic review did not consider timing of exposure during pregnancy, maternal infection severity, or exposure to various SARS-CoV-2 variants – all factors that could eventually be proven to contribute to subtle adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they write.

Additionally, past pandemics “such as the 1918 Spanish flu, 1964 rubella, and 2009 H1N1” have taught researchers to watch for increases in diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia in subsequent years.

“ASD is generally diagnosed at age 3-5 years (and often not until early teens), while schizophrenia is generally diagnosed in mid-to-late 20s,” the editorialists point out. The authors agree and emphasize the need for long-term studies.

Authors report no relevant financial relationships. Editorialist Dr. Dumitriu reports grants from National Institute of Mental Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation; and has received gift funds from Einhorn Collaborative during the conduct of the study to the Nurture Science Program, for which Dr Dumitriu serves as director. Dr. Dumitriu received personal fees from Medela outside the submitted work; and is the corresponding author for one of the studies (Shuffrey et al., 2022) included in the systematic review conducted by Dr. Hessami et al. Dr. Lavallée reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Martinez reports no relevant financial relationships.

There’s some good overall news in a large analysis that looked at whether a mother’s COVID-19 infection or birth during the pandemic could affect a baby’s brain development.

Researchers studied 21,419 infants who had neurodevelopmental screening during the pandemic (from January 2020 to January 2021) and compared them with babies born before the pandemic (2015-2019).

They found in an analysis of eight studies that, generally, brain development in infants ages 6-12 months old was not changed by COVID-19.

Communication skill scores lower than prepandemic

However, one area did see a significant difference when they looked at answers to the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 3rd edition (ASQ-3): Scores were lower in communication skills.

Compared with the prepandemic babies, the pandemic group of babies was more likely to have communication impairment (odds were 1.7 times higher).

Additionally, mothers’ SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with significant differences in any neurodevelopment sector in offspring, with one exception: Odds were 3.5 times higher for fine motor impairment in the pandemic baby group.

The babies in this study were either exposed in the womb to the SARS-CoV-2 infection or screened during the pandemic regardless of whether they were exposed to the virus.

The study, led by Kamran Hessami, MD, with the Maternal Fetal Care Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, was published in JAMA Network Open.

Potential reasons for lower communication skills

The study points to some factors of the pandemic that may be tied to impaired communication skills.

“Higher levels of COVID-19–related stress were reported for both mothers and fathers of infants aged 0-6 months and were associated with insensitive parenting practices, including decreased emotional responsiveness in only mothers, which could lessen the reciprocal exchanges that support language development in early childhood,” they write. “Additionally, opportunities to promote language and social development through new experiences outside the home, including visits with extended family and friends or attendance at a child care center, were lessened for many during the pandemic.”

Viviana M. Fajardo Martinez, MD, with neonatal/perinatal medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, Health, told this publication her team is also studying child development before and after the pandemic over a 3-year period, and delayed communication skills is something she is seeing in clinic there.

She says some parents have been concerned, saying their babies aren’t talking enough or are behind in vocabulary.

Babies can catch up after 12 months

One thing she tells parents is that babies who are a bit delayed at 12 months can catch up.

Up to 18 months, they can catch up, she said, adding that they can be reevaluated then for improvement. If, at that point, the baby is not catching up, “that’s when we refer for early intervention,” she said.

Dr. Martinez also tells parents concerned about their infant’s communication skills that it’s important to talk, read, and sing to their child. She said amid pandemic stress, corners may have been cut in asking children to use language skills.

For instance, if a child points to an apple, a stressed parent may just give the child the apple instead of asking the child to request it by name and repeat the word several times.

She also said a limitation of this study is the use of the ASQ-3 questionnaire, which is filled out by parents. Answers are subjective, she notes, and sometimes differ between one child’s two parents. The questionnaire was commonly used during the pandemic because a more objective, professional evaluation has been more difficult.

However, a measure like the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Screening Test adds objectivity and will likely give a better picture as research progresses, Dr. Martinez said.

Some information missing

Andréane Lavallée, PhD, and Dani Dumitriu, MD, PhD, both with the department of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, write in an invited commentary that the overall positive message of the study “should not make researchers complacent” and results should be viewed with caution.

They point out that the precise effects of this novel virus are still unclear and the age group and variables studied may not tell the whole story.

“It should be noted that this systematic review did not consider timing of exposure during pregnancy, maternal infection severity, or exposure to various SARS-CoV-2 variants – all factors that could eventually be proven to contribute to subtle adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes,” they write.

Additionally, past pandemics “such as the 1918 Spanish flu, 1964 rubella, and 2009 H1N1” have taught researchers to watch for increases in diagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia in subsequent years.

“ASD is generally diagnosed at age 3-5 years (and often not until early teens), while schizophrenia is generally diagnosed in mid-to-late 20s,” the editorialists point out. The authors agree and emphasize the need for long-term studies.

Authors report no relevant financial relationships. Editorialist Dr. Dumitriu reports grants from National Institute of Mental Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation; and has received gift funds from Einhorn Collaborative during the conduct of the study to the Nurture Science Program, for which Dr Dumitriu serves as director. Dr. Dumitriu received personal fees from Medela outside the submitted work; and is the corresponding author for one of the studies (Shuffrey et al., 2022) included in the systematic review conducted by Dr. Hessami et al. Dr. Lavallée reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Martinez reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Finerenone: ‘Striking’ cut in pneumonia, COVID-19 risks

The nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone (Kerendia) unexpectedly showed that it might protect against incident infective pneumonia and COVID-19. The finding was based on secondary analyses run on more than 13,000 people enrolled in the two pivotal trials for finerenone.

Finerenone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for slowing progressive renal dysfunction and preventing cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

‘Striking reduction in the risk of pneumonia’

The “striking reduction in risk of pneumonia” in a new analysis suggests that “the propagation of pulmonary infection into lobar or bronchial consolidation may be reduced by finerenone,” write Bertram Pitt, MD, and coauthors in a report published on October 26 in JAMA Network Open.

They also suggest that if further studies confirm that finerenone treatment reduces complications from pneumonia and COVID-19, it would have “significant medical implications,” especially because of the limited treatment options now available for complications from COVID-19.

The new analyses used the FIDELITY dataset, a prespecified merging of results from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials, which together enrolled 13,026 people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, as determined on the basis of the patients’ having a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of at least 30 mg/g.

The primary outcomes of these trials showed that treatment with finerenone led to significant slowing of the progression of CKD and a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events, compared with placebo during median follow-up of 3 years.

The new, secondary analyses focused on the 6.0% of participants in whom there was evidence of pneumonia and the 1.6% in whom there was evidence of having COVID-19. Pneumonia was the most common serious adverse event in the two trials, a finding consistent with the documented risk for pneumonia faced by people with CKD.

Finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction in pneumonia

When analyzed by treatment, the incidence of pneumonia was 4.7% among those who received finerenone and 6.7% among those who received placebo. This translated into a significant relative risk reduction of 29% associated with finerenone treatment.

Analysis of COVID-19 adverse events showed a 1.3% incidence among those who received finerenone and a 1.8% incidence among those in the placebo group, which translated into a significant 27% relative risk reduction linked with finerenone treatment.

In contrast, the data showed no reduced incidence of several other respiratory infections among the finerenone recipients, including nasopharyngitis, bronchitis, and influenza. The data also showed no signal that pneumonia or COVID-19 was more severe among the people who did not receive finerenone, nor did finerenone treatment appear to affect pneumonia recovery.

Analysis based on adverse events reports

These secondary analyses are far from definitive. The authors relied on pneumonia and COVID-19 being reported as adverse events. Each investigator diagnosed pneumonia at their discretion, and the trials did not specify diagnostic criteria. The authors also acknowledge that testing for COVID-19 was “not widespread” and that one of the two pivotal trials largely ran prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic so that only 6 participants developed COVID-19 symptoms out of more than 5,700 enrolled.

The authors hypothesize that several actions of finerenone might potentially help mediate an effect on pneumonia and COVID-19: improvements in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis, upregulation of expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2, and amelioration of right heart pressure and pulmonary congestion. Also, antagonizing the mineralocorticoid receptor on monocytes and macrophages may block macrophage infiltration and accumulation of active macrophages, which can mediate the pulmonary tissue damage caused by COVID-19.

The FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and the FIDELITY combined database were sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Pitt has received personal fees from Bayer and personal fees and stock options from numerous other companies. Several coauthors reported having a financial relationship with Bayer, as well as with other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone (Kerendia) unexpectedly showed that it might protect against incident infective pneumonia and COVID-19. The finding was based on secondary analyses run on more than 13,000 people enrolled in the two pivotal trials for finerenone.

Finerenone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for slowing progressive renal dysfunction and preventing cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

‘Striking reduction in the risk of pneumonia’

The “striking reduction in risk of pneumonia” in a new analysis suggests that “the propagation of pulmonary infection into lobar or bronchial consolidation may be reduced by finerenone,” write Bertram Pitt, MD, and coauthors in a report published on October 26 in JAMA Network Open.

They also suggest that if further studies confirm that finerenone treatment reduces complications from pneumonia and COVID-19, it would have “significant medical implications,” especially because of the limited treatment options now available for complications from COVID-19.

The new analyses used the FIDELITY dataset, a prespecified merging of results from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials, which together enrolled 13,026 people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, as determined on the basis of the patients’ having a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of at least 30 mg/g.

The primary outcomes of these trials showed that treatment with finerenone led to significant slowing of the progression of CKD and a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events, compared with placebo during median follow-up of 3 years.

The new, secondary analyses focused on the 6.0% of participants in whom there was evidence of pneumonia and the 1.6% in whom there was evidence of having COVID-19. Pneumonia was the most common serious adverse event in the two trials, a finding consistent with the documented risk for pneumonia faced by people with CKD.

Finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction in pneumonia

When analyzed by treatment, the incidence of pneumonia was 4.7% among those who received finerenone and 6.7% among those who received placebo. This translated into a significant relative risk reduction of 29% associated with finerenone treatment.

Analysis of COVID-19 adverse events showed a 1.3% incidence among those who received finerenone and a 1.8% incidence among those in the placebo group, which translated into a significant 27% relative risk reduction linked with finerenone treatment.

In contrast, the data showed no reduced incidence of several other respiratory infections among the finerenone recipients, including nasopharyngitis, bronchitis, and influenza. The data also showed no signal that pneumonia or COVID-19 was more severe among the people who did not receive finerenone, nor did finerenone treatment appear to affect pneumonia recovery.

Analysis based on adverse events reports

These secondary analyses are far from definitive. The authors relied on pneumonia and COVID-19 being reported as adverse events. Each investigator diagnosed pneumonia at their discretion, and the trials did not specify diagnostic criteria. The authors also acknowledge that testing for COVID-19 was “not widespread” and that one of the two pivotal trials largely ran prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic so that only 6 participants developed COVID-19 symptoms out of more than 5,700 enrolled.

The authors hypothesize that several actions of finerenone might potentially help mediate an effect on pneumonia and COVID-19: improvements in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis, upregulation of expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2, and amelioration of right heart pressure and pulmonary congestion. Also, antagonizing the mineralocorticoid receptor on monocytes and macrophages may block macrophage infiltration and accumulation of active macrophages, which can mediate the pulmonary tissue damage caused by COVID-19.

The FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and the FIDELITY combined database were sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Pitt has received personal fees from Bayer and personal fees and stock options from numerous other companies. Several coauthors reported having a financial relationship with Bayer, as well as with other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone (Kerendia) unexpectedly showed that it might protect against incident infective pneumonia and COVID-19. The finding was based on secondary analyses run on more than 13,000 people enrolled in the two pivotal trials for finerenone.

Finerenone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for slowing progressive renal dysfunction and preventing cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

‘Striking reduction in the risk of pneumonia’

The “striking reduction in risk of pneumonia” in a new analysis suggests that “the propagation of pulmonary infection into lobar or bronchial consolidation may be reduced by finerenone,” write Bertram Pitt, MD, and coauthors in a report published on October 26 in JAMA Network Open.

They also suggest that if further studies confirm that finerenone treatment reduces complications from pneumonia and COVID-19, it would have “significant medical implications,” especially because of the limited treatment options now available for complications from COVID-19.

The new analyses used the FIDELITY dataset, a prespecified merging of results from the FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials, which together enrolled 13,026 people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, as determined on the basis of the patients’ having a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of at least 30 mg/g.

The primary outcomes of these trials showed that treatment with finerenone led to significant slowing of the progression of CKD and a significant reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events, compared with placebo during median follow-up of 3 years.

The new, secondary analyses focused on the 6.0% of participants in whom there was evidence of pneumonia and the 1.6% in whom there was evidence of having COVID-19. Pneumonia was the most common serious adverse event in the two trials, a finding consistent with the documented risk for pneumonia faced by people with CKD.

Finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction in pneumonia

When analyzed by treatment, the incidence of pneumonia was 4.7% among those who received finerenone and 6.7% among those who received placebo. This translated into a significant relative risk reduction of 29% associated with finerenone treatment.

Analysis of COVID-19 adverse events showed a 1.3% incidence among those who received finerenone and a 1.8% incidence among those in the placebo group, which translated into a significant 27% relative risk reduction linked with finerenone treatment.

In contrast, the data showed no reduced incidence of several other respiratory infections among the finerenone recipients, including nasopharyngitis, bronchitis, and influenza. The data also showed no signal that pneumonia or COVID-19 was more severe among the people who did not receive finerenone, nor did finerenone treatment appear to affect pneumonia recovery.

Analysis based on adverse events reports

These secondary analyses are far from definitive. The authors relied on pneumonia and COVID-19 being reported as adverse events. Each investigator diagnosed pneumonia at their discretion, and the trials did not specify diagnostic criteria. The authors also acknowledge that testing for COVID-19 was “not widespread” and that one of the two pivotal trials largely ran prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic so that only 6 participants developed COVID-19 symptoms out of more than 5,700 enrolled.

The authors hypothesize that several actions of finerenone might potentially help mediate an effect on pneumonia and COVID-19: improvements in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis, upregulation of expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2, and amelioration of right heart pressure and pulmonary congestion. Also, antagonizing the mineralocorticoid receptor on monocytes and macrophages may block macrophage infiltration and accumulation of active macrophages, which can mediate the pulmonary tissue damage caused by COVID-19.

The FIDELIO-DKD and FIGARO-DKD trials and the FIDELITY combined database were sponsored by Bayer, the company that markets finerenone (Kerendia). Dr. Pitt has received personal fees from Bayer and personal fees and stock options from numerous other companies. Several coauthors reported having a financial relationship with Bayer, as well as with other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is it flu, RSV, or COVID? Experts fear the ‘tripledemic’

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ivermectin for COVID-19: Final nail in the coffin

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

It began in a petri dish.

Ivermectin, a widely available, cheap, and well-tolerated drug on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for its critical role in treating river blindness, was shown to dramatically reduce the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture.

You know the rest of the story. Despite the fact that the median inhibitory concentration in cell culture is about 100-fold higher than what one can achieve with oral dosing in humans, anecdotal reports of miraculous cures proliferated.

Cohort studies suggested that people who got ivermectin did very well in terms of COVID outcomes.

A narrative started to develop online – one that is still quite present today – that authorities were suppressing the good news about ivermectin in order to line their own pockets and those of the execs at Big Pharma. The official Twitter account of the Food and Drug Administration clapped back, reminding the populace that we are not horses or cows.

And every time a study came out that seemed like the nail in the coffin for the so-called horse paste, it rose again, vampire-like, feasting on the blood of social media outrage.

The truth is that, while excitement for ivermectin mounted online, it crashed quite quickly in scientific circles. Most randomized trials showed no effect of the drug. A couple of larger trials which seemed to show dramatic effects were subsequently shown to be fraudulent.

Then the TOGETHER trial was published. The 1,400-patient study from Brazil, which treated outpatients with COVID-19, found no significant difference in hospitalization or ER visits – the primary outcome – between those randomized to ivermectin vs. placebo or another therapy.

But still, Brazil. Different population than the United States. Different health systems. And very different rates of Strongyloides infections (this is a parasite that may be incidentally treated by ivermectin, leading to improvement independent of the drug’s effect on COVID). We all wanted a U.S. trial.

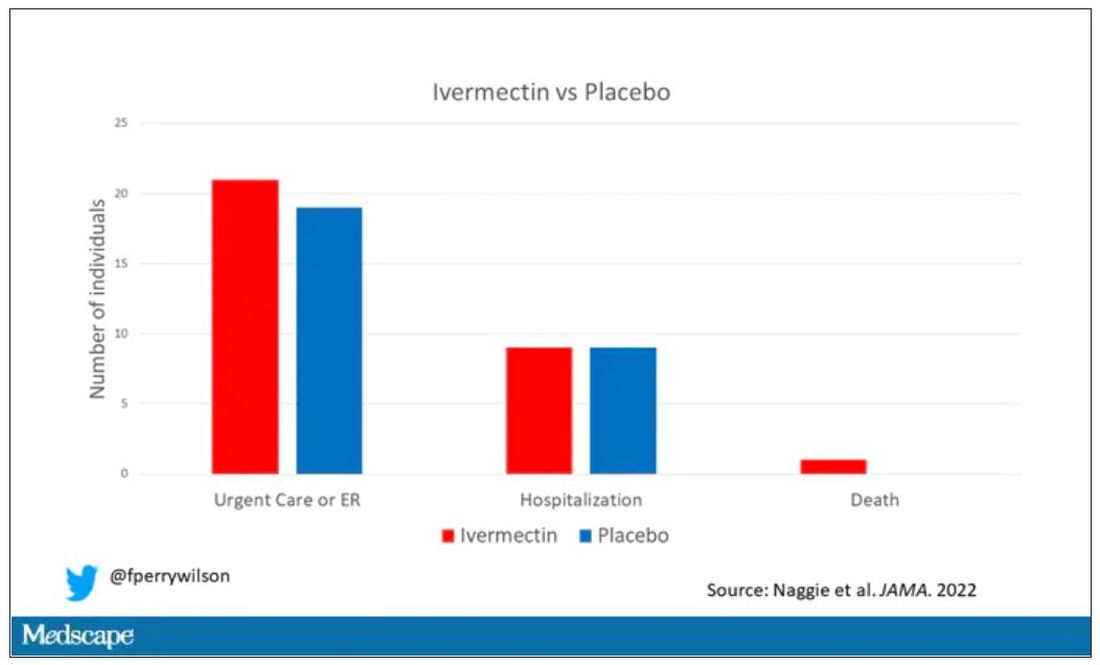

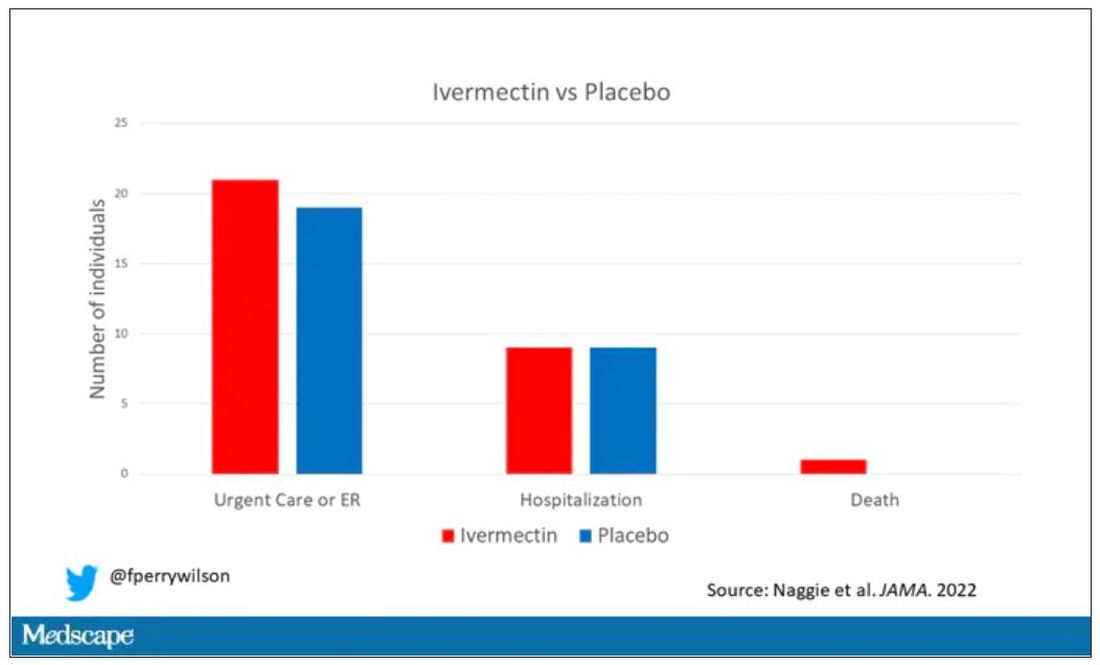

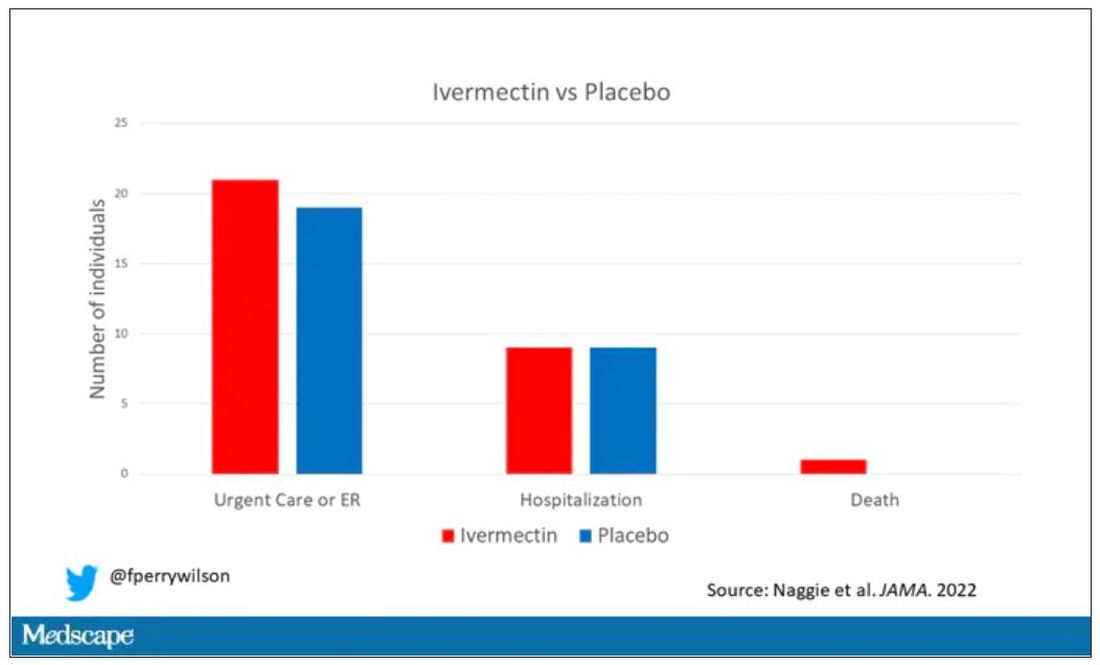

And now we have it. ACTIV-6 was published Oct. 21 in JAMA, a study randomizing outpatients with COVID-19 from 93 sites around the United States to ivermectin or placebo.

A total of 1,591 individuals – median age 47, 60% female – with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized from June 2021 to February 2022. About half had been vaccinated.

The primary outcome was straightforward: time to clinical recovery. The time to recovery, defined as having three symptom-free days, was 12 days in the ivermectin group and 13 days in the placebo group – that’s within the margin of error.

But overall, everyone in the trial did fairly well. Serious outcomes, like death, hospitalization, urgent care, or ER visits, occurred in 32 people in the ivermectin group and 28 in the placebo group. Death itself was rare – just one occurred in the trial, in someone receiving ivermectin.OK, are we done with this drug yet? Is this nice U.S. randomized trial enough to convince people that results from a petri dish don’t always transfer to humans, regardless of the presence or absence of an evil pharmaceutical cabal?

No, of course not. At this point, I can predict the responses. The dose wasn’t high enough. It wasn’t given early enough. The patients weren’t sick enough, or they were too sick. This is motivated reasoning, plain and simple. It’s not to say that there isn’t a chance that this drug has some off-target effects on COVID that we haven’t adequately measured, but studies like ACTIV-6 effectively rule out the idea that it’s a miracle cure. And you know what? That’s OK. Miracle cures are vanishingly rare. Most things that work in medicine work OK; they make us a little better, and we learn why they do that and improve on them, and try again and again. It’s not flashy; it doesn’t have that allure of secret knowledge. But it’s what separates science from magic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator; his science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

It began in a petri dish.

Ivermectin, a widely available, cheap, and well-tolerated drug on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for its critical role in treating river blindness, was shown to dramatically reduce the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture.

You know the rest of the story. Despite the fact that the median inhibitory concentration in cell culture is about 100-fold higher than what one can achieve with oral dosing in humans, anecdotal reports of miraculous cures proliferated.

Cohort studies suggested that people who got ivermectin did very well in terms of COVID outcomes.

A narrative started to develop online – one that is still quite present today – that authorities were suppressing the good news about ivermectin in order to line their own pockets and those of the execs at Big Pharma. The official Twitter account of the Food and Drug Administration clapped back, reminding the populace that we are not horses or cows.

And every time a study came out that seemed like the nail in the coffin for the so-called horse paste, it rose again, vampire-like, feasting on the blood of social media outrage.