User login

Third COVID booster benefits cancer patients

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CANCER

No benefit of rivaroxaban in COVID outpatients: PREVENT-HD

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new U.S. randomized trial has failed to show benefit of a 35-day course of oral anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for the prevention of thrombotic events in outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19.

The PREVENT-HD trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Gregory Piazza, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“With the caveat that the trial was underpowered to provide a definitive conclusion, these data do not support routine antithrombotic prophylaxis in nonhospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19,” Dr. Piazza concluded.

PREVENT-HD is the largest randomized study to look at anticoagulation in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients and joins a long list of smaller trials that have also shown no benefit with this approach.

However, anticoagulation is recommended in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19.

Dr. Piazza noted that the issue of anticoagulation in COVID-19 has focused mainly on hospitalized patients, but most COVID-19 cases are treated as outpatients, who are also suspected to be at risk for venous and arterial thrombotic events, especially if they have additional risk factors. Histopathological evidence also suggests that at least part of the deterioration in lung function leading to hospitalization may be attributable to in situ pulmonary artery thrombosis.

The PREVENT-HD trial explored the question of whether early initiation of thromboprophylaxis dosing of rivaroxaban in higher-risk outpatients with COVID-19 may lower the incidence of venous and arterial thrombotic events, reduce in situ pulmonary thrombosis and the worsening of pulmonary function that may lead to hospitalization, and reduce all-cause mortality.

The trial included 1,284 outpatients with a positive test for COVID-19 and who were within 14 days of symptom onset. They also had to have at least one of the following additional risk factors: age over 60 years; prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), thrombophilia, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, cardiovascular disease or ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes, heart failure, obesity (body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2) or D-dimer > upper limit of normal. Around 35% of the study population had two or more of these risk factors.

Patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 35 days or placebo.

The primary efficacy endpoint was time to first occurrence of a composite of symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non–central nervous system systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization, and all-cause mortality up to day 35.

The primary safety endpoint was time to first occurrence of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) critical-site and fatal bleeding.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis (all participants taking at least one dose of study intervention) was also planned.

The trial was stopped early in April this year because of a lower than expected event incidence (3.2%), compared with the planned rate (8.5%), giving a very low likelihood of being able to achieve the required number of events.

Dr. Piazza said reasons contributing to the low event rate included a falling COVID-19 death and hospitalization rate nationwide, and increased use of effective vaccines.

Results of the main intention-to-treat analysis (in 1,284 patients) showed no significant difference in the primary efficacy composite endpoint, which occurred in 3.4% of the rivaroxaban group versus 3.0% of the placebo group.

In the modified intention-to-treat analysis (which included 1,197 patients who actually took at least one dose of the study medication) there was shift in the directionality of the point estimate (rivaroxaban 2.0% vs. placebo 2.7%), which Dr. Piazza said was related to a higher number of patients hospitalized before receiving study drug in the rivaroxaban group. However, the difference was still nonsignificant.

The first major secondary outcome of symptomatic VTE, arterial thrombotic events, and all-cause mortality occurred in 0.3% of rivaroxaban patients versus 1.1% of placebo patients, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

However, a post hoc exploratory analysis did show a significant reduction in the outcome of symptomatic VTE and arterial thrombotic events.

In terms of safety, there were no fatal critical-site bleeding events, and there was no difference in ISTH major bleeding, which occurred in one patient in the rivaroxaban group versus no patients in the placebo group.

There was, however, a significant increase in nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding with rivaroxaban, which occurred in nine patients (1.5%) versus one patient (0.2%) in the placebo group.

Trivial bleeding was also increased in the rivaroxaban group, occurring in 17 patients (2.8%) versus 5 patients (0.8%) in the placebo group.

Discussant for the study, Renato Lopes, MD, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., noted that the relationship between COVID-19 and thrombosis has been an important issue since the beginning of the pandemic, with many proposed mechanisms to explain the COVID-19–associated coagulopathy, which is a major cause of death and disability.

While observational data at the beginning of the pandemic suggested patients with COVID-19 might benefit from anticoagulation, looking at all the different randomized trials that have tested anticoagulation in COVID-19 outpatients, there is no treatment effect on the various different primary outcomes in those studies and also no effect on all-cause mortality, Dr. Lopes said.

He pointed out that PREVENT-HD was stopped prematurely with only about one-third of the planned number of patients enrolled, “just like every other outpatient COVID-19 trial.”

He also drew attention to the low rates of vaccination in the trial population, which does not reflect the current vaccination rate in the United States, and said the different direction of the results between the main intention-to-treat and modified intention-to-treat analyses deserve further investigation.

However, Dr. Lopes concluded, “The results of this trial, in line with the body of evidence in this field, do not support the routine use of any antithrombotic therapy for outpatients with COVID-19.”

The PREVENT-HD trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Piazza has reported receiving research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Janssen, Alexion, Amgen, and Boston Scientific, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Boston Scientific, Janssen, NAMSA, Prairie Education and Research Cooperative, Boston Clinical Research Institute, and Amgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2022

More Than a Health Fair: Preventive Health Care During COVID-19 Vaccine Events

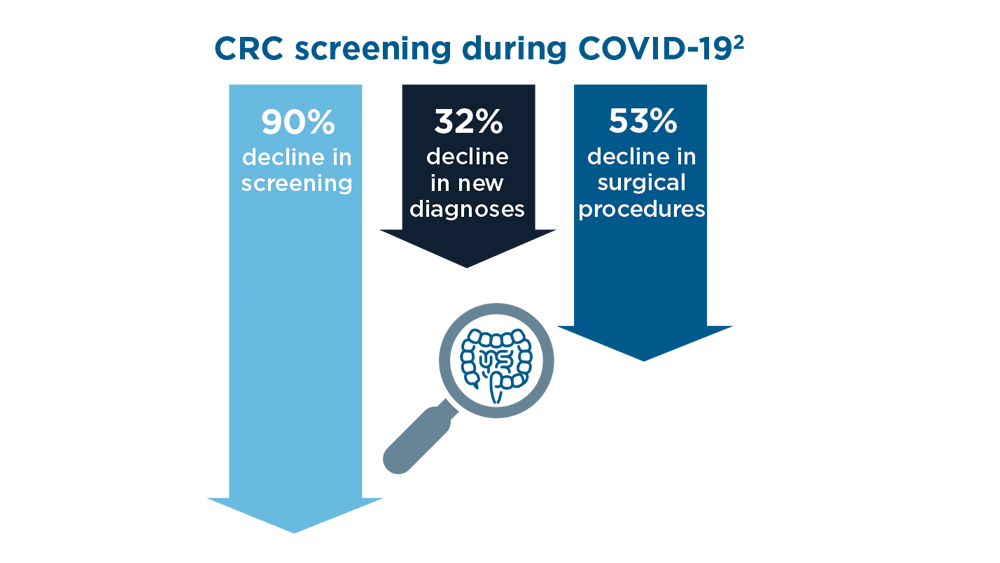

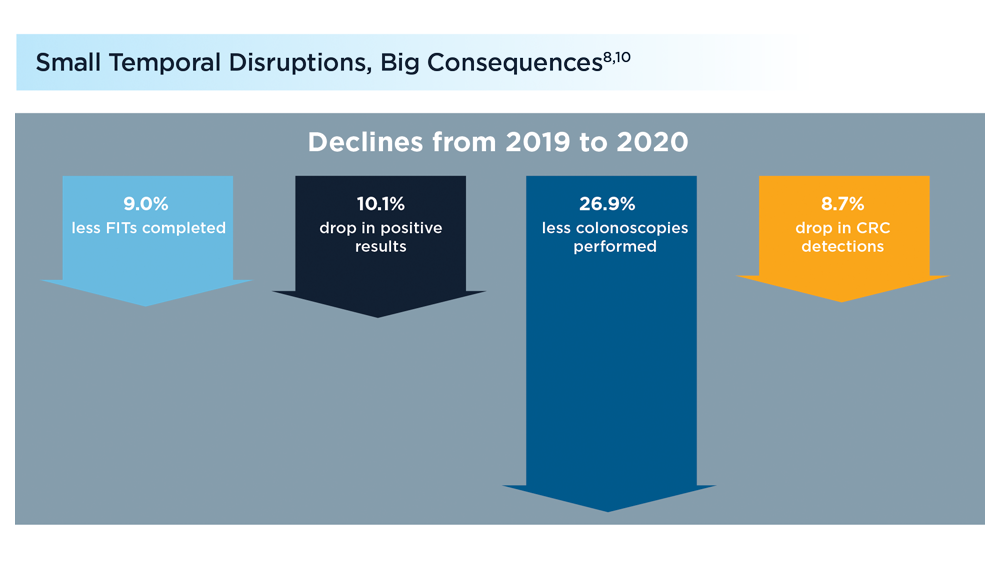

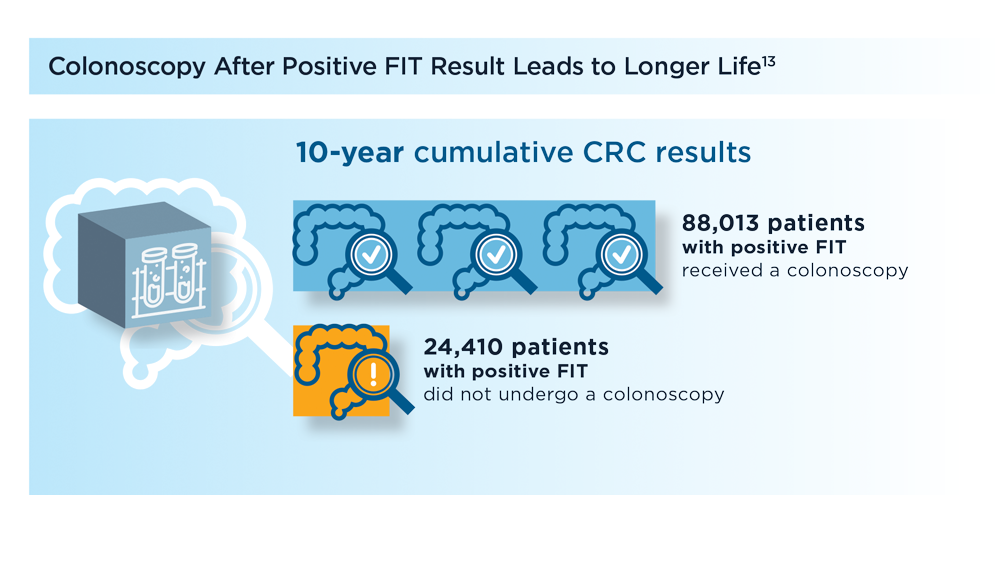

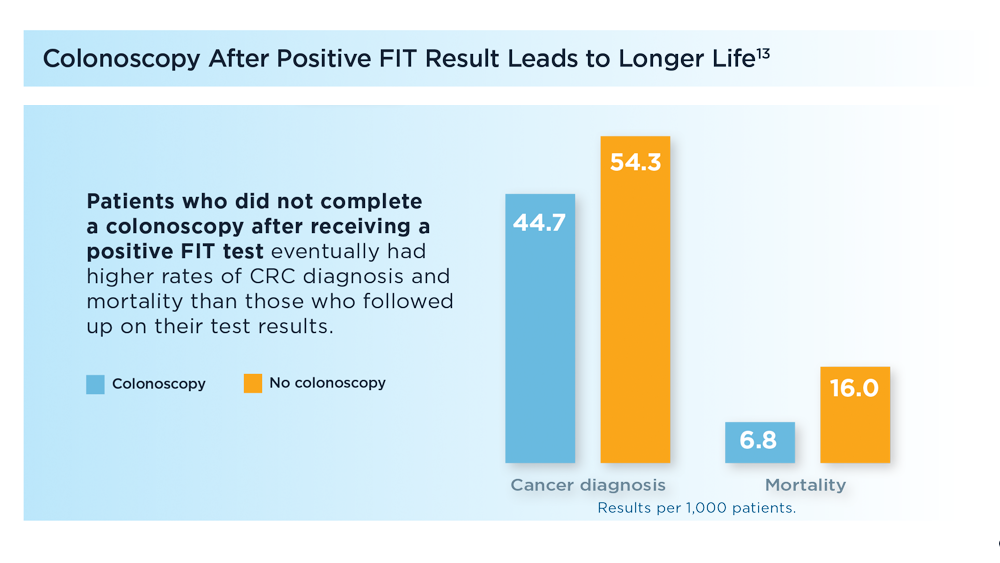

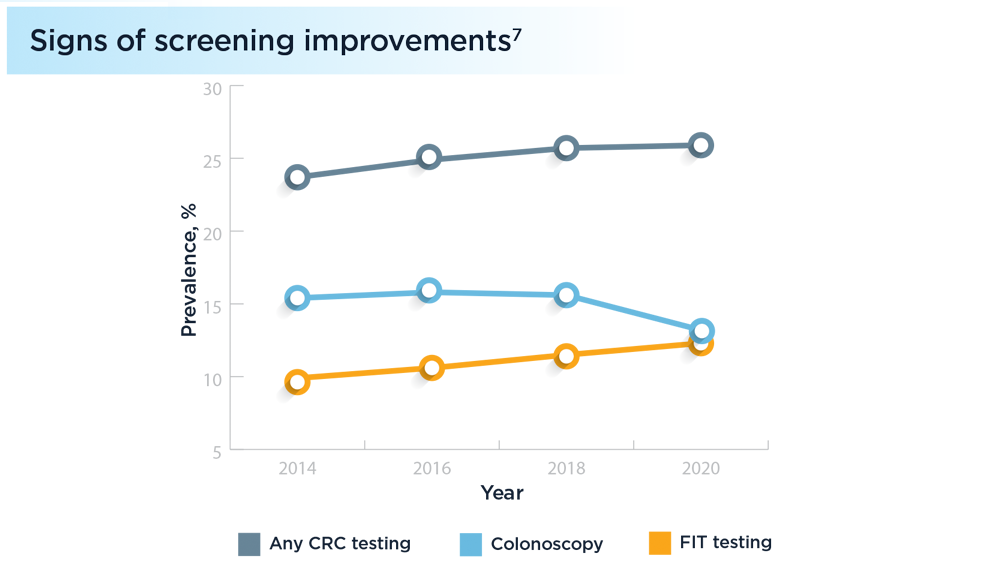

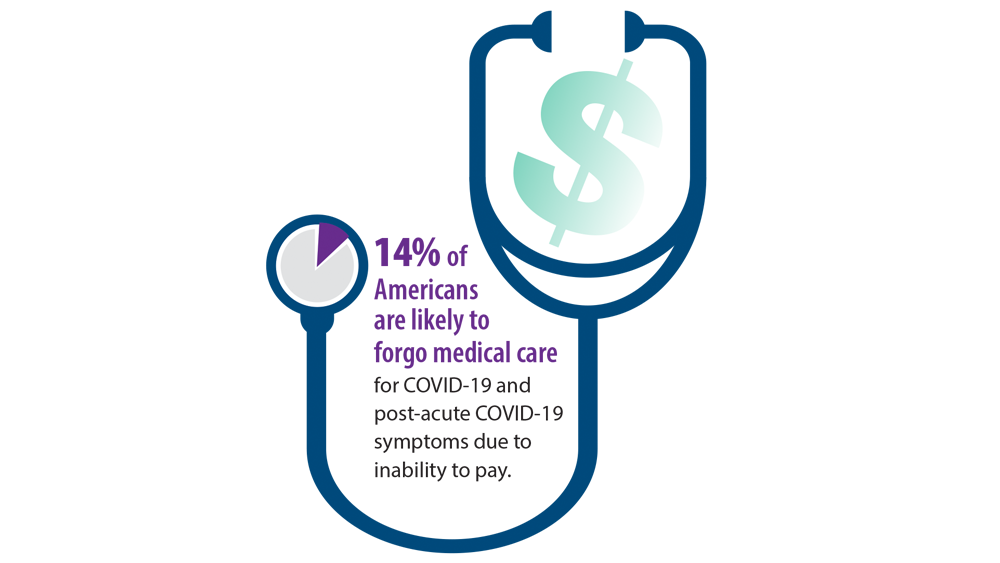

Shortly into the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Robert Califf, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, warned of a coming tsunami of chronic diseases, exacerbated by missed care during the pandemic.1 According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey, more than 30% of adults reported delaying or avoiding routine medical care in the first 6 months of 2020. This rate was highest in people with comorbidities.2 Multiple studies demonstrated declines in hypertension care, hemoglobin A1c testing, mammography, and colon cancer screening.3-5 There has been a resultant increase in colon cancer complications, wounds, and amputations.6,7 The United Kingdom is expected to have a 7.9% to 16.6% increase in future deaths due to breast and colorectal cancer (CRC).8 The World Health Organization estimates an excess 14.9 million people died in 2020 and 2021, either directly from or indirectly related to COVID-19.9

Due to the large-scale conversion from face-to-face care to telehealth modalities, COVID-19 vaccination events offered a unique opportunity to perform preventive health care that requires in-person visits, since most US adults have sought vaccination. However, vaccine events may not reach people most at risk for COVID-19 or chronic disease. Groups of Americans with lower vaccination rates were concerned about driving times and missing work to get the vaccine.10

Distance and travel time may be a particular challenge in Hawaii. Oahu is considered rural by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA); some communities are 80 minutes away from the VA Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS) main facility. Oahu has approximately 150 veterans experiencing homelessness who may not have transportation to vaccine events. Additionally, VAPIHCS serves veterans that may be at higher risk of not receiving COVID-19 vaccination. Racial and ethnic minority residents have lower vaccination rates, yet are at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and complications, and through the pandemic, this vaccination gap worsened.11,12 More than 10% of the population of Hawaii is Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and this population is at elevated risk for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and COVID-19 mortality.13-16

Health Fair Program

The VA provides clinical reminders in its electronic health record (EHR) that are specified by age, gender assigned at birth, and comorbidities. The clinical reminder program is intended to provide clinically relevant reminders for preventive care at the point of care. Veterans with overdue clinical reminders can be identified by name and address, allowing for the creation of health fair events that were directed towards communities with veterans with clinical reminders, including COVID-19 vaccination need. A team of health care professionals from VAPIHCS conceived of a health fair program to increase the reach of vaccine events and include preventive care in partnership with the VAPIHCS Vet Center Program, local communities, U.S.VETS, and the Hawaii Institute of Health Services (HIHS). We sought to determine which services could be offered in community settings; large vaccine events; and at homeless emergency, transitional, or permanent housing. We tracked veterans who received care in the different locations of the directed health fair.

This project was determined to be a quality improvement initiative by the VAPIHCS Office of Research and Development. It was jointly planned by the VAPIHCS pharmacy, infectious diseases, Vet Center Program, and homeless team to make the COVID-19 vaccines available to more rural and to veterans experiencing homelessness, and in response to a decline in facility face-to-face visits. Monthly meetings were held to select sites within zip codes with higher numbers of open clinical reminders and lower vaccination uptake. Informatics developed a list of clinical reminders by zip code for care performed at face-to-face visits.

Partners

The Vet Center Program, suicide prevention coordinator, and the homeless outreach team have a mandate to perform outreach events.17,18 These services collaborate with community partners to locate sites for events. The team was able to leverage these contacts to set up sites for events. The Vet Center Program readjustment counselor and the suicide prevention coordinator provide mental health counseling. The Vet Center counsels on veteran benefits. They supplied a mobile van with WiFi, counseling and examination spaces, and refrigeration, which became the mobile clinic for the preventive care offered at events. The homeless program works with multiple community partners. They contract with HIHS and U.S.VETS to provide emergency and permanent housing for veterans. Each event is reviewed with HIHS and U.S.VETS staff for permission to be on site. The suicide prevention coordinator or the Vet Center readjustment counselor and the homeless team became regular attendees of events. The homeless team provided resources for housing or food insecurity.

Preventive Health Measures

The VA clinical reminder system supports caregivers for both preventive health care and chronic condition management.19 Clinical reminders appear as due in the EHR, and reminder reports can be run by clinical informatics to determine groups of patients who have not had a reminder completed. The following reminders were completed: vaccinations (including COVID-19), CRC screening, diabetic foot check and teaching of foot care, diabetic retinal consultations, laboratory studies (lipids, hemoglobin A1c, microalbumin), mammogram and pap smear referrals, mental health reminders, homeless and food insecurity screening, HIV and hepatitis C testing, and blood pressure (BP) measurement. Health records were reviewed 3 months after each event to determine whether they were completed by the veteran. Additionally, we determined whether BP was controlled (< 130/80 mm Hg).

Settings

Large urban event. The first setting for the health fair was a large vaccination event near the VAPIHCS center in April 2021. Attendance was solicited by VEText, phone calls, and social media advertisements. At check-in, veterans with relevant open clinical reminders were invited to receive preventive health care during the 15-minute monitoring period after the COVID-19 vaccine. The Vet Center Program stationed the mobile van outside the vaccination event, where a physician and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) did assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests for about 4 hours. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Community Settings. Nine events occurred at least monthly between March and September 2021 at 4 different sites in Oahu. Texts and phone calls were used to solicit attendance; there was no prior publicity on social media. Community events required scheduling resources; this required about 30 hours of medical staff assistant time. Seven sites were visited for about 3 hours each. A physician, pharmacy technician, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Homeless veteran outreach. Five events occurred at 2 homeless veteran housing sites between August 2021 and January 2022. These sites were emergency housing sites (2 events) and transitional and permanent housing (2 events). U.S.VETS and HIHS contacted veterans living in those settings to promote the event. A physician, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans that had never signed up for VA health care. Each event lasted approximate 3 hours.

Process Quality Improvement

After the CDC changed recommendations to allow concurrent vaccination with the COVID-19 vaccine, we added other vaccinations to the events. This occurred during the course of community events. In June of 2021, there was a health advisory concerning hepatitis A among people experiencing homelessness in Oahu, so hepatitis vaccinations were added for events for veterans.20

Veterans Served

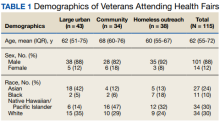

The EHR was used to determine demographics, open clinical reminders, and attendance at follow-up. Simple descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel. A total of 115 veterans were seen for preventive health visits, and 404 clinical reminders were completed. Seven hundred veterans attended the large centrally located vaccine event and 43 agreed to have a preventive health visit. Thirty-eight veterans had a preventive health visit at homeless outreach events and 34 veterans had a preventive health visit at the community events. Veterans at community

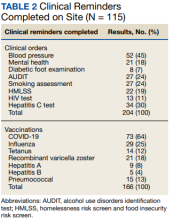

Of the 166 vaccines given, 73 were for COVID-19. Besides vaccination,

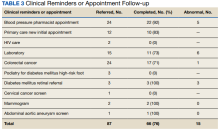

Veteran follow-up or completion

Discussion

This program provided evidence that adding preventive screenings to vaccine events may help reach veterans who may have missed important preventive care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The involvement of clinical informatics service allowed the outreach to be targeted to communities with incomplete clinical reminders. Interventions that could not be completed at the event had high levels of follow-up by veterans with important findings. The presence of a physician or nurse and a CPS allowed for point-of-care testing, as well as entering orders for medication, laboratory tests, and consultations. The attendance by representatives from the Vet Center, suicide prevention, and homeless services allowed counseling regarding benefits, and mental health follow-up. We believe that we were able to reach communities of veterans with unmet preventive needs and had higher risk of severe COVID-19, given the high numbers with open clinical reminders, the number of vaccines provided, and the high percentage of racial and ethnic minority veterans at events in the community. Our program experience provides some evidence that mobile and pop-up vaccination clinics may be beneficial for screening and managing chronic diseases, as proposed elsewhere.21-24

Strengths of this intervention include that we were able to show a high level of follow-up for recommended medical care as well as the results of our interventions. We have found no similar articles that provide data on completion of follow-up appointments after a health fair. A prior study showed only 23% to 63% of participants at a health fair reported having a recommended follow-up discussion with doctors, but the study reported no outcome of completed cancer screenings.25

Limitations

Weaknesses include the fact that health fair events may reach only healthy people, since attendees generally report better health and better health behaviors than nonattendees.26,27 We felt this was more problematic for the large-scale urban event and that offering rural events and events in homeless housing improved the reach. Future efforts will involve the use of social media and mailings to solicit attendance. To improve follow-up, future work will include adding to the events: phlebotomy or expanded point-of-care testing; specialty care telehealth capability; cervical cancer screen self-collection; and tele-retinal services.

Conclusions

This program provided evidence that directed, preventive screening can be performed in outreach settings paired with vaccine events. These vaccination events in rural and homeless settings reached communities with demonstrable COVID-19 vaccination and other preventive care needs. This approach could be used to help veterans catch up on needed preventive care.

Acknowledgments

Veterans Affairs Pacific Islands Health Care System: Anthony Chance, LCSW; Nicholas Chang, PharmD; Andrew Dahlburg, LCSW; Wilminia G. Ellorimo-Gil, RN; Paul Guillory, RN; Wendy D. Joy; Arthur Minor, LCSW; Avalua Smith; Jessica Spurrier, RN. Veterans Health Administration Vet Center Program: Rolly O. Alvarado; Edmond G. DeGuzman; Richard T. Teel. Hawaii Institute for Human Services. U.S.VETS.

1. Califf RM. Avoiding the coming tsunami of common, chronic disease: What the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic can teach us. Circulation. 2021;143(19):1831-1834. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.053461

2. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

3. European Society of Hypertension Corona-virus Disease 19 Task Force. The corona-virus disease 2019 pandemic compromised routine care for hypertension: a survey conducted among excellence centers of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2021;39(1):190-195. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002703

4. Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J, et al. Changes in health services use among commercially insured US populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024984. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24984

5. Song H, Bergman A, Chen AT, et al. Disruptions in preventive care: mammograms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(1):95-101. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13596

6. Shinkwin M, Silva L, Vogel I, et al. COVID-19 and the emergency presentation of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(8):2014-2019. doi:10.1111/codi.15662

7. Rogers LC, Snyder RJ, Joseph WS. Diabetes-related amputations: a pandemic within a pandemic. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2020;20-248. doi:10.7547/20-248

8. Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023-1034. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0

9. World Health Organization. 14.9 million excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. May 5, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2022-14.9-million-excess-deaths-were-associated-with-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-2020-and-2021

10. Padamsee TJ, Bond RM, Dixon GN, et al. Changes in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black and White individuals in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2144470. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44470

11. Barry V, Dasgupta S, Weller DL, et al. Patterns in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, by social vulnerability and urbanicity - United States, December 14, 2020-May 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(22):818-824. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7022e1

12. Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18-39 years - United States, March-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):928-933. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2

13. United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Hawaii. July 7, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/HI

14. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse. Diabetes - Adult. November 23, 2021. Updated July 31, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://hhdw.org/report/indicator/summary/DXDiabetesAA.html

15. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse. High Blood Pressure, Adult. November 23, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://hhdw.org/report/indicator/summary/DXBPHighAA.html

16. Penaia CS, Morey BN, Thomas KB, et al. Disparities in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander COVID-19 mortality: a community-driven data response. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(S2):S49-S52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.306370

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1500.02 Readjustment Counseling Services (RCS) Vet Center Program. January 26, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9168

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1162.08 Health Care for Veterans Homeless Outreach Services. February 18, 2022. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9673

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical Reminders Version 2.0. Clinician Guide. October 2006. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vdl/documents/clinical/cprs-clinical_reminders/pxrm_2_4_um.pdf

20. Hawaii Department of Health. Hepatitis A Cases on Oahu and Maui. June 21, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/files/2021/06/Medical-Advisory-HepA-June-21-2021.pdf

21. Hamel L, Lopes L, Sparks G, et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: January 2022. January 28, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-january-2022

22. Mast C, Munoz del Rio A. Delayed cancer screenings—a second look. Epic Research Network. July 17, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://epicresearch.org/articles/delayed-cancer-screenings-a-second-look

23. Shaukat A, Church T. Colorectal cancer screening in the USA in the wake of COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(8):726-727. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30191-6

24. Crespo J, Lazarus JV, Iruzubieta P, García F, García-Samaniego J; Alliance for the elimination of viral hepatitis in Spain. Let’s leverage SARS-CoV2 vaccination to screen for hepatitis C in Spain, in Europe, around the world. J Hepatol. 2021;75(1):224-226. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2021.03.009

25. Escoffery C, Liang S, Rodgers K, et al. Process evaluation of health fairs promoting cancer screenings. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):865. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3867-3

26. Waller PR, Crow C, Sands D, Becker H. Health related attitudes and health promoting behaviors: differences between health fair attenders and a community group. Am J Health Promot. 1988;3(1):17-32. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-3.1.17

27. Price JH, O’Connell J, Kukulka G. Preventive health behaviors related to the ten leading causes of mortality of health-fair attenders and nonattenders. Psychol Rep. 1985;56(1):131-135. doi:10.2466/pr0.1985.56.1.131

Shortly into the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Robert Califf, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, warned of a coming tsunami of chronic diseases, exacerbated by missed care during the pandemic.1 According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey, more than 30% of adults reported delaying or avoiding routine medical care in the first 6 months of 2020. This rate was highest in people with comorbidities.2 Multiple studies demonstrated declines in hypertension care, hemoglobin A1c testing, mammography, and colon cancer screening.3-5 There has been a resultant increase in colon cancer complications, wounds, and amputations.6,7 The United Kingdom is expected to have a 7.9% to 16.6% increase in future deaths due to breast and colorectal cancer (CRC).8 The World Health Organization estimates an excess 14.9 million people died in 2020 and 2021, either directly from or indirectly related to COVID-19.9

Due to the large-scale conversion from face-to-face care to telehealth modalities, COVID-19 vaccination events offered a unique opportunity to perform preventive health care that requires in-person visits, since most US adults have sought vaccination. However, vaccine events may not reach people most at risk for COVID-19 or chronic disease. Groups of Americans with lower vaccination rates were concerned about driving times and missing work to get the vaccine.10

Distance and travel time may be a particular challenge in Hawaii. Oahu is considered rural by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA); some communities are 80 minutes away from the VA Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS) main facility. Oahu has approximately 150 veterans experiencing homelessness who may not have transportation to vaccine events. Additionally, VAPIHCS serves veterans that may be at higher risk of not receiving COVID-19 vaccination. Racial and ethnic minority residents have lower vaccination rates, yet are at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and complications, and through the pandemic, this vaccination gap worsened.11,12 More than 10% of the population of Hawaii is Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and this population is at elevated risk for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and COVID-19 mortality.13-16

Health Fair Program

The VA provides clinical reminders in its electronic health record (EHR) that are specified by age, gender assigned at birth, and comorbidities. The clinical reminder program is intended to provide clinically relevant reminders for preventive care at the point of care. Veterans with overdue clinical reminders can be identified by name and address, allowing for the creation of health fair events that were directed towards communities with veterans with clinical reminders, including COVID-19 vaccination need. A team of health care professionals from VAPIHCS conceived of a health fair program to increase the reach of vaccine events and include preventive care in partnership with the VAPIHCS Vet Center Program, local communities, U.S.VETS, and the Hawaii Institute of Health Services (HIHS). We sought to determine which services could be offered in community settings; large vaccine events; and at homeless emergency, transitional, or permanent housing. We tracked veterans who received care in the different locations of the directed health fair.

This project was determined to be a quality improvement initiative by the VAPIHCS Office of Research and Development. It was jointly planned by the VAPIHCS pharmacy, infectious diseases, Vet Center Program, and homeless team to make the COVID-19 vaccines available to more rural and to veterans experiencing homelessness, and in response to a decline in facility face-to-face visits. Monthly meetings were held to select sites within zip codes with higher numbers of open clinical reminders and lower vaccination uptake. Informatics developed a list of clinical reminders by zip code for care performed at face-to-face visits.

Partners

The Vet Center Program, suicide prevention coordinator, and the homeless outreach team have a mandate to perform outreach events.17,18 These services collaborate with community partners to locate sites for events. The team was able to leverage these contacts to set up sites for events. The Vet Center Program readjustment counselor and the suicide prevention coordinator provide mental health counseling. The Vet Center counsels on veteran benefits. They supplied a mobile van with WiFi, counseling and examination spaces, and refrigeration, which became the mobile clinic for the preventive care offered at events. The homeless program works with multiple community partners. They contract with HIHS and U.S.VETS to provide emergency and permanent housing for veterans. Each event is reviewed with HIHS and U.S.VETS staff for permission to be on site. The suicide prevention coordinator or the Vet Center readjustment counselor and the homeless team became regular attendees of events. The homeless team provided resources for housing or food insecurity.

Preventive Health Measures

The VA clinical reminder system supports caregivers for both preventive health care and chronic condition management.19 Clinical reminders appear as due in the EHR, and reminder reports can be run by clinical informatics to determine groups of patients who have not had a reminder completed. The following reminders were completed: vaccinations (including COVID-19), CRC screening, diabetic foot check and teaching of foot care, diabetic retinal consultations, laboratory studies (lipids, hemoglobin A1c, microalbumin), mammogram and pap smear referrals, mental health reminders, homeless and food insecurity screening, HIV and hepatitis C testing, and blood pressure (BP) measurement. Health records were reviewed 3 months after each event to determine whether they were completed by the veteran. Additionally, we determined whether BP was controlled (< 130/80 mm Hg).

Settings

Large urban event. The first setting for the health fair was a large vaccination event near the VAPIHCS center in April 2021. Attendance was solicited by VEText, phone calls, and social media advertisements. At check-in, veterans with relevant open clinical reminders were invited to receive preventive health care during the 15-minute monitoring period after the COVID-19 vaccine. The Vet Center Program stationed the mobile van outside the vaccination event, where a physician and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) did assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests for about 4 hours. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Community Settings. Nine events occurred at least monthly between March and September 2021 at 4 different sites in Oahu. Texts and phone calls were used to solicit attendance; there was no prior publicity on social media. Community events required scheduling resources; this required about 30 hours of medical staff assistant time. Seven sites were visited for about 3 hours each. A physician, pharmacy technician, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Homeless veteran outreach. Five events occurred at 2 homeless veteran housing sites between August 2021 and January 2022. These sites were emergency housing sites (2 events) and transitional and permanent housing (2 events). U.S.VETS and HIHS contacted veterans living in those settings to promote the event. A physician, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans that had never signed up for VA health care. Each event lasted approximate 3 hours.

Process Quality Improvement

After the CDC changed recommendations to allow concurrent vaccination with the COVID-19 vaccine, we added other vaccinations to the events. This occurred during the course of community events. In June of 2021, there was a health advisory concerning hepatitis A among people experiencing homelessness in Oahu, so hepatitis vaccinations were added for events for veterans.20

Veterans Served

The EHR was used to determine demographics, open clinical reminders, and attendance at follow-up. Simple descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel. A total of 115 veterans were seen for preventive health visits, and 404 clinical reminders were completed. Seven hundred veterans attended the large centrally located vaccine event and 43 agreed to have a preventive health visit. Thirty-eight veterans had a preventive health visit at homeless outreach events and 34 veterans had a preventive health visit at the community events. Veterans at community

Of the 166 vaccines given, 73 were for COVID-19. Besides vaccination,

Veteran follow-up or completion

Discussion

This program provided evidence that adding preventive screenings to vaccine events may help reach veterans who may have missed important preventive care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The involvement of clinical informatics service allowed the outreach to be targeted to communities with incomplete clinical reminders. Interventions that could not be completed at the event had high levels of follow-up by veterans with important findings. The presence of a physician or nurse and a CPS allowed for point-of-care testing, as well as entering orders for medication, laboratory tests, and consultations. The attendance by representatives from the Vet Center, suicide prevention, and homeless services allowed counseling regarding benefits, and mental health follow-up. We believe that we were able to reach communities of veterans with unmet preventive needs and had higher risk of severe COVID-19, given the high numbers with open clinical reminders, the number of vaccines provided, and the high percentage of racial and ethnic minority veterans at events in the community. Our program experience provides some evidence that mobile and pop-up vaccination clinics may be beneficial for screening and managing chronic diseases, as proposed elsewhere.21-24

Strengths of this intervention include that we were able to show a high level of follow-up for recommended medical care as well as the results of our interventions. We have found no similar articles that provide data on completion of follow-up appointments after a health fair. A prior study showed only 23% to 63% of participants at a health fair reported having a recommended follow-up discussion with doctors, but the study reported no outcome of completed cancer screenings.25

Limitations

Weaknesses include the fact that health fair events may reach only healthy people, since attendees generally report better health and better health behaviors than nonattendees.26,27 We felt this was more problematic for the large-scale urban event and that offering rural events and events in homeless housing improved the reach. Future efforts will involve the use of social media and mailings to solicit attendance. To improve follow-up, future work will include adding to the events: phlebotomy or expanded point-of-care testing; specialty care telehealth capability; cervical cancer screen self-collection; and tele-retinal services.

Conclusions

This program provided evidence that directed, preventive screening can be performed in outreach settings paired with vaccine events. These vaccination events in rural and homeless settings reached communities with demonstrable COVID-19 vaccination and other preventive care needs. This approach could be used to help veterans catch up on needed preventive care.

Acknowledgments

Veterans Affairs Pacific Islands Health Care System: Anthony Chance, LCSW; Nicholas Chang, PharmD; Andrew Dahlburg, LCSW; Wilminia G. Ellorimo-Gil, RN; Paul Guillory, RN; Wendy D. Joy; Arthur Minor, LCSW; Avalua Smith; Jessica Spurrier, RN. Veterans Health Administration Vet Center Program: Rolly O. Alvarado; Edmond G. DeGuzman; Richard T. Teel. Hawaii Institute for Human Services. U.S.VETS.

Shortly into the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Robert Califf, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, warned of a coming tsunami of chronic diseases, exacerbated by missed care during the pandemic.1 According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey, more than 30% of adults reported delaying or avoiding routine medical care in the first 6 months of 2020. This rate was highest in people with comorbidities.2 Multiple studies demonstrated declines in hypertension care, hemoglobin A1c testing, mammography, and colon cancer screening.3-5 There has been a resultant increase in colon cancer complications, wounds, and amputations.6,7 The United Kingdom is expected to have a 7.9% to 16.6% increase in future deaths due to breast and colorectal cancer (CRC).8 The World Health Organization estimates an excess 14.9 million people died in 2020 and 2021, either directly from or indirectly related to COVID-19.9

Due to the large-scale conversion from face-to-face care to telehealth modalities, COVID-19 vaccination events offered a unique opportunity to perform preventive health care that requires in-person visits, since most US adults have sought vaccination. However, vaccine events may not reach people most at risk for COVID-19 or chronic disease. Groups of Americans with lower vaccination rates were concerned about driving times and missing work to get the vaccine.10

Distance and travel time may be a particular challenge in Hawaii. Oahu is considered rural by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA); some communities are 80 minutes away from the VA Pacific Islands Health Care System (VAPIHCS) main facility. Oahu has approximately 150 veterans experiencing homelessness who may not have transportation to vaccine events. Additionally, VAPIHCS serves veterans that may be at higher risk of not receiving COVID-19 vaccination. Racial and ethnic minority residents have lower vaccination rates, yet are at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and complications, and through the pandemic, this vaccination gap worsened.11,12 More than 10% of the population of Hawaii is Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and this population is at elevated risk for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and COVID-19 mortality.13-16

Health Fair Program

The VA provides clinical reminders in its electronic health record (EHR) that are specified by age, gender assigned at birth, and comorbidities. The clinical reminder program is intended to provide clinically relevant reminders for preventive care at the point of care. Veterans with overdue clinical reminders can be identified by name and address, allowing for the creation of health fair events that were directed towards communities with veterans with clinical reminders, including COVID-19 vaccination need. A team of health care professionals from VAPIHCS conceived of a health fair program to increase the reach of vaccine events and include preventive care in partnership with the VAPIHCS Vet Center Program, local communities, U.S.VETS, and the Hawaii Institute of Health Services (HIHS). We sought to determine which services could be offered in community settings; large vaccine events; and at homeless emergency, transitional, or permanent housing. We tracked veterans who received care in the different locations of the directed health fair.

This project was determined to be a quality improvement initiative by the VAPIHCS Office of Research and Development. It was jointly planned by the VAPIHCS pharmacy, infectious diseases, Vet Center Program, and homeless team to make the COVID-19 vaccines available to more rural and to veterans experiencing homelessness, and in response to a decline in facility face-to-face visits. Monthly meetings were held to select sites within zip codes with higher numbers of open clinical reminders and lower vaccination uptake. Informatics developed a list of clinical reminders by zip code for care performed at face-to-face visits.

Partners

The Vet Center Program, suicide prevention coordinator, and the homeless outreach team have a mandate to perform outreach events.17,18 These services collaborate with community partners to locate sites for events. The team was able to leverage these contacts to set up sites for events. The Vet Center Program readjustment counselor and the suicide prevention coordinator provide mental health counseling. The Vet Center counsels on veteran benefits. They supplied a mobile van with WiFi, counseling and examination spaces, and refrigeration, which became the mobile clinic for the preventive care offered at events. The homeless program works with multiple community partners. They contract with HIHS and U.S.VETS to provide emergency and permanent housing for veterans. Each event is reviewed with HIHS and U.S.VETS staff for permission to be on site. The suicide prevention coordinator or the Vet Center readjustment counselor and the homeless team became regular attendees of events. The homeless team provided resources for housing or food insecurity.

Preventive Health Measures

The VA clinical reminder system supports caregivers for both preventive health care and chronic condition management.19 Clinical reminders appear as due in the EHR, and reminder reports can be run by clinical informatics to determine groups of patients who have not had a reminder completed. The following reminders were completed: vaccinations (including COVID-19), CRC screening, diabetic foot check and teaching of foot care, diabetic retinal consultations, laboratory studies (lipids, hemoglobin A1c, microalbumin), mammogram and pap smear referrals, mental health reminders, homeless and food insecurity screening, HIV and hepatitis C testing, and blood pressure (BP) measurement. Health records were reviewed 3 months after each event to determine whether they were completed by the veteran. Additionally, we determined whether BP was controlled (< 130/80 mm Hg).

Settings

Large urban event. The first setting for the health fair was a large vaccination event near the VAPIHCS center in April 2021. Attendance was solicited by VEText, phone calls, and social media advertisements. At check-in, veterans with relevant open clinical reminders were invited to receive preventive health care during the 15-minute monitoring period after the COVID-19 vaccine. The Vet Center Program stationed the mobile van outside the vaccination event, where a physician and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) did assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests for about 4 hours. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Community Settings. Nine events occurred at least monthly between March and September 2021 at 4 different sites in Oahu. Texts and phone calls were used to solicit attendance; there was no prior publicity on social media. Community events required scheduling resources; this required about 30 hours of medical staff assistant time. Seven sites were visited for about 3 hours each. A physician, pharmacy technician, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans who had never signed up for VA health care.

Homeless veteran outreach. Five events occurred at 2 homeless veteran housing sites between August 2021 and January 2022. These sites were emergency housing sites (2 events) and transitional and permanent housing (2 events). U.S.VETS and HIHS contacted veterans living in those settings to promote the event. A physician, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and CPS conducted assessments, completed reminders, and entered follow-up requests. A medical support assistant registered veterans that had never signed up for VA health care. Each event lasted approximate 3 hours.

Process Quality Improvement

After the CDC changed recommendations to allow concurrent vaccination with the COVID-19 vaccine, we added other vaccinations to the events. This occurred during the course of community events. In June of 2021, there was a health advisory concerning hepatitis A among people experiencing homelessness in Oahu, so hepatitis vaccinations were added for events for veterans.20

Veterans Served

The EHR was used to determine demographics, open clinical reminders, and attendance at follow-up. Simple descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel. A total of 115 veterans were seen for preventive health visits, and 404 clinical reminders were completed. Seven hundred veterans attended the large centrally located vaccine event and 43 agreed to have a preventive health visit. Thirty-eight veterans had a preventive health visit at homeless outreach events and 34 veterans had a preventive health visit at the community events. Veterans at community

Of the 166 vaccines given, 73 were for COVID-19. Besides vaccination,

Veteran follow-up or completion

Discussion

This program provided evidence that adding preventive screenings to vaccine events may help reach veterans who may have missed important preventive care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The involvement of clinical informatics service allowed the outreach to be targeted to communities with incomplete clinical reminders. Interventions that could not be completed at the event had high levels of follow-up by veterans with important findings. The presence of a physician or nurse and a CPS allowed for point-of-care testing, as well as entering orders for medication, laboratory tests, and consultations. The attendance by representatives from the Vet Center, suicide prevention, and homeless services allowed counseling regarding benefits, and mental health follow-up. We believe that we were able to reach communities of veterans with unmet preventive needs and had higher risk of severe COVID-19, given the high numbers with open clinical reminders, the number of vaccines provided, and the high percentage of racial and ethnic minority veterans at events in the community. Our program experience provides some evidence that mobile and pop-up vaccination clinics may be beneficial for screening and managing chronic diseases, as proposed elsewhere.21-24

Strengths of this intervention include that we were able to show a high level of follow-up for recommended medical care as well as the results of our interventions. We have found no similar articles that provide data on completion of follow-up appointments after a health fair. A prior study showed only 23% to 63% of participants at a health fair reported having a recommended follow-up discussion with doctors, but the study reported no outcome of completed cancer screenings.25

Limitations

Weaknesses include the fact that health fair events may reach only healthy people, since attendees generally report better health and better health behaviors than nonattendees.26,27 We felt this was more problematic for the large-scale urban event and that offering rural events and events in homeless housing improved the reach. Future efforts will involve the use of social media and mailings to solicit attendance. To improve follow-up, future work will include adding to the events: phlebotomy or expanded point-of-care testing; specialty care telehealth capability; cervical cancer screen self-collection; and tele-retinal services.

Conclusions

This program provided evidence that directed, preventive screening can be performed in outreach settings paired with vaccine events. These vaccination events in rural and homeless settings reached communities with demonstrable COVID-19 vaccination and other preventive care needs. This approach could be used to help veterans catch up on needed preventive care.

Acknowledgments

Veterans Affairs Pacific Islands Health Care System: Anthony Chance, LCSW; Nicholas Chang, PharmD; Andrew Dahlburg, LCSW; Wilminia G. Ellorimo-Gil, RN; Paul Guillory, RN; Wendy D. Joy; Arthur Minor, LCSW; Avalua Smith; Jessica Spurrier, RN. Veterans Health Administration Vet Center Program: Rolly O. Alvarado; Edmond G. DeGuzman; Richard T. Teel. Hawaii Institute for Human Services. U.S.VETS.

1. Califf RM. Avoiding the coming tsunami of common, chronic disease: What the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic can teach us. Circulation. 2021;143(19):1831-1834. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.053461

2. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

3. European Society of Hypertension Corona-virus Disease 19 Task Force. The corona-virus disease 2019 pandemic compromised routine care for hypertension: a survey conducted among excellence centers of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2021;39(1):190-195. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002703

4. Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J, et al. Changes in health services use among commercially insured US populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024984. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24984

5. Song H, Bergman A, Chen AT, et al. Disruptions in preventive care: mammograms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(1):95-101. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13596

6. Shinkwin M, Silva L, Vogel I, et al. COVID-19 and the emergency presentation of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(8):2014-2019. doi:10.1111/codi.15662

7. Rogers LC, Snyder RJ, Joseph WS. Diabetes-related amputations: a pandemic within a pandemic. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2020;20-248. doi:10.7547/20-248

8. Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023-1034. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0

9. World Health Organization. 14.9 million excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. May 5, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2022-14.9-million-excess-deaths-were-associated-with-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-2020-and-2021

10. Padamsee TJ, Bond RM, Dixon GN, et al. Changes in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black and White individuals in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2144470. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44470

11. Barry V, Dasgupta S, Weller DL, et al. Patterns in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, by social vulnerability and urbanicity - United States, December 14, 2020-May 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(22):818-824. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7022e1

12. Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18-39 years - United States, March-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):928-933. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2

13. United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Hawaii. July 7, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/HI

14. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse. Diabetes - Adult. November 23, 2021. Updated July 31, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://hhdw.org/report/indicator/summary/DXDiabetesAA.html

15. Hawaii Health Data Warehouse. High Blood Pressure, Adult. November 23, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://hhdw.org/report/indicator/summary/DXBPHighAA.html

16. Penaia CS, Morey BN, Thomas KB, et al. Disparities in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander COVID-19 mortality: a community-driven data response. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(S2):S49-S52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.306370

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1500.02 Readjustment Counseling Services (RCS) Vet Center Program. January 26, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9168

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1162.08 Health Care for Veterans Homeless Outreach Services. February 18, 2022. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9673