User login

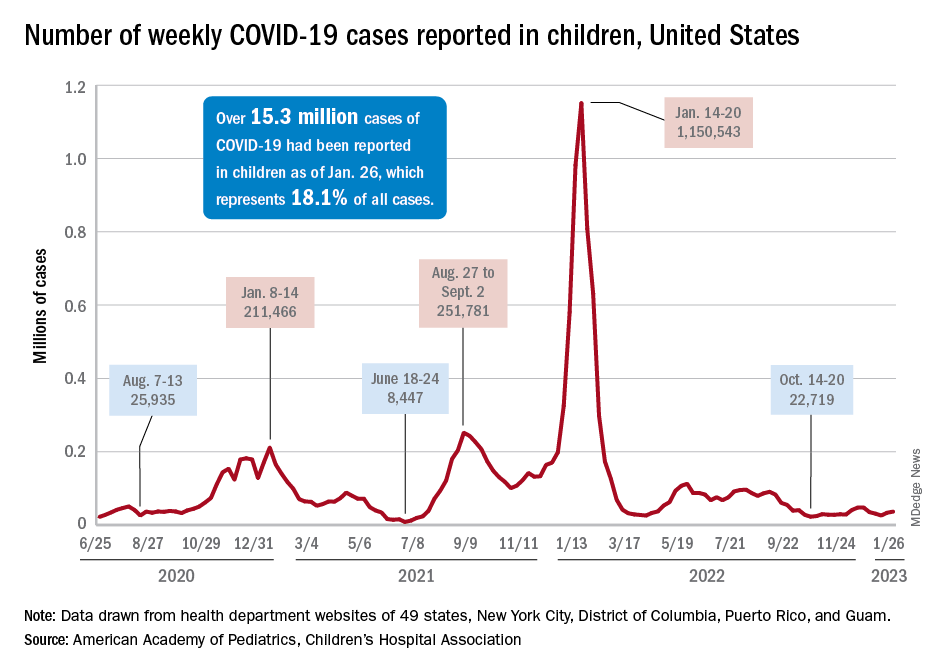

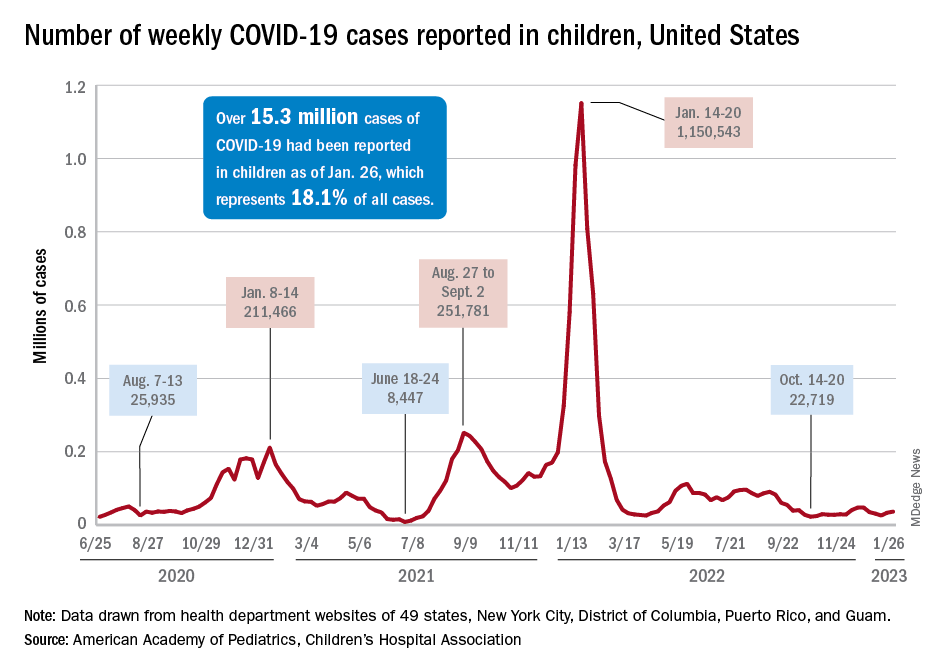

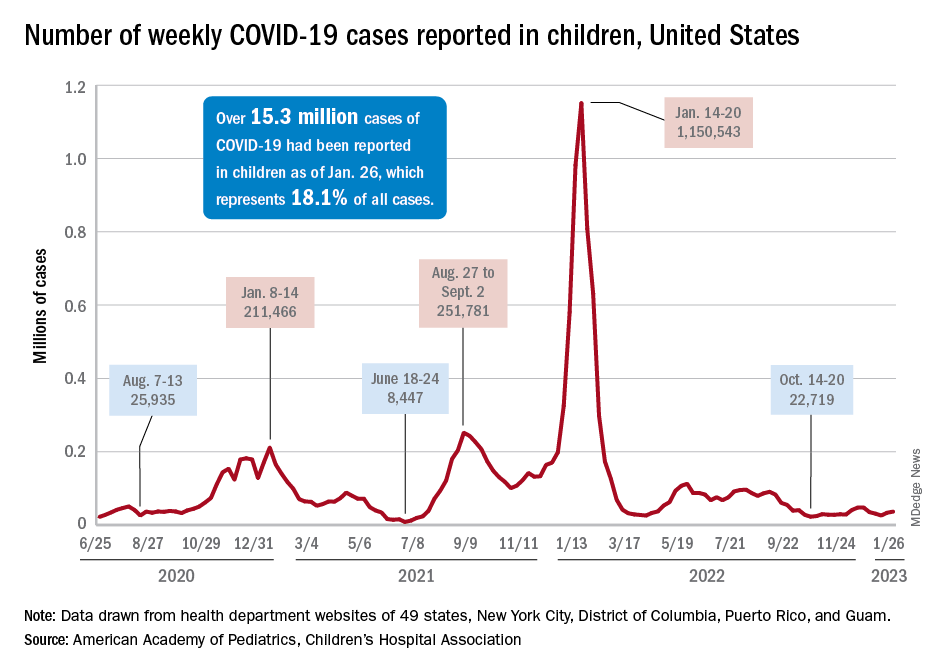

Children and COVID: Weekly cases may have doubled in early January

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Managing respiratory symptoms in the ‘tripledemic’ era

Is it COVID-19, flu, or even RSV? I recently described just such a patient, an obese woman with type 2 diabetes, presenting with fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue. I asked readers whether they agreed with my management of this patient.

Thank you for your comments as we continue to react to high rates of URIs. Your comments highlight the importance of local resources and practice habits when managing patients with URI.

It was clear that readers value testing to distinguish between infections. However, access to testing is highly variable around the world and is likely to be routinely used only in high-income countries. The Kaiser Family Foundation performed a cost analysis of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 and found, not surprisingly, wide variability in the cost of testing. Medicare covers tests at rates of $36-$143 per test; a study of list prices for SARS-CoV-2 tests at 93 hospitals found a median cost of $148 per test. And this does not include collection or facility fees. About 20% of tests cost more than $300.

These costs are prohibitive for many health systems. However, more devices have been introduced since that analysis, and competition and evolving technology should drive down prices. Generally, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for multiple pathogens is less expensive than ordering two or three separate molecular tests and is more convenient for patients and practices alike.

Other reader comments focused on the challenges of getting accurate data on viral epidemiology, and there is certainly a time lag between infection trends and public health reports. This is exacerbated by underreporting of symptoms and more testing at home using antigen tests.

But please do not give up on epidemiology! If a test such as PCR is 90% sensitive for identifying infection, the yield in terms of the number of individuals infected with a particular virus should be high, and that is true when infection is in broad circulation. If 20% of a population of 1,000 has an infection and the test sensitivity is 90%, the yield of testing is 180 true cases versus 20 false positives.

However, if just 2% of the population of 1,000 has the infection in this same scenario, then only 18 true cases are identified. The effect on public health is certainly less, and a lower prevalence rate means that confounding variables, such as how long an individual might shed viral particles and the method of sample collection, have an outsized effect on results. This reduces the validity of diagnostic tests.

Even trends on a national level can provide some insight regarding whom to test. Traditionally, our practice has been to not routinely test patients for influenza or RSV from late spring to early fall unless there was a compelling reason, such as recent travel to an area where these infections were more prevalent. The loss of temporality for these infections since 2020 has altered this approach and made us pay more attention to reports from public health organizations.

I also appreciate the discussion of how to treat Agnes’s symptoms as she waits to improve, and anyone who suffers with or treats a viral URI knows that there are few interventions effective for such symptoms as cough and congestion. A systematic review of 29 randomized controlled trials of over-the-counter medications for cough yielded mixed and largely negative results.

Antihistamines alone do not seem to work, and guaifenesin was successful in only one of three trials. Combinations of different drug classes appeared to be slightly more effective.

My personal favorite for the management of acute cough is something that kids generally love: honey. In a review of 14 studies, 9 of which were limited to pediatric patients, honey was associated with significant reductions in cough frequency, cough severity, and total symptom score. However, there was a moderate risk of bias in the included research, and evidence of honey’s benefit in placebo-controlled trials was limited. Honey used in this research came in a variety of forms, so the best dosage is uncertain.

Clearly, advancements are needed. Better symptom management in viral URI will almost certainly improve productivity across the population and will probably reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics as well. I have said for years that the scientists who can solve the Gordian knot of pediatric mucus deserve three Nobel prizes. I look forward to that golden day.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported a conflict of interest with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is it COVID-19, flu, or even RSV? I recently described just such a patient, an obese woman with type 2 diabetes, presenting with fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue. I asked readers whether they agreed with my management of this patient.

Thank you for your comments as we continue to react to high rates of URIs. Your comments highlight the importance of local resources and practice habits when managing patients with URI.

It was clear that readers value testing to distinguish between infections. However, access to testing is highly variable around the world and is likely to be routinely used only in high-income countries. The Kaiser Family Foundation performed a cost analysis of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 and found, not surprisingly, wide variability in the cost of testing. Medicare covers tests at rates of $36-$143 per test; a study of list prices for SARS-CoV-2 tests at 93 hospitals found a median cost of $148 per test. And this does not include collection or facility fees. About 20% of tests cost more than $300.

These costs are prohibitive for many health systems. However, more devices have been introduced since that analysis, and competition and evolving technology should drive down prices. Generally, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for multiple pathogens is less expensive than ordering two or three separate molecular tests and is more convenient for patients and practices alike.

Other reader comments focused on the challenges of getting accurate data on viral epidemiology, and there is certainly a time lag between infection trends and public health reports. This is exacerbated by underreporting of symptoms and more testing at home using antigen tests.

But please do not give up on epidemiology! If a test such as PCR is 90% sensitive for identifying infection, the yield in terms of the number of individuals infected with a particular virus should be high, and that is true when infection is in broad circulation. If 20% of a population of 1,000 has an infection and the test sensitivity is 90%, the yield of testing is 180 true cases versus 20 false positives.

However, if just 2% of the population of 1,000 has the infection in this same scenario, then only 18 true cases are identified. The effect on public health is certainly less, and a lower prevalence rate means that confounding variables, such as how long an individual might shed viral particles and the method of sample collection, have an outsized effect on results. This reduces the validity of diagnostic tests.

Even trends on a national level can provide some insight regarding whom to test. Traditionally, our practice has been to not routinely test patients for influenza or RSV from late spring to early fall unless there was a compelling reason, such as recent travel to an area where these infections were more prevalent. The loss of temporality for these infections since 2020 has altered this approach and made us pay more attention to reports from public health organizations.

I also appreciate the discussion of how to treat Agnes’s symptoms as she waits to improve, and anyone who suffers with or treats a viral URI knows that there are few interventions effective for such symptoms as cough and congestion. A systematic review of 29 randomized controlled trials of over-the-counter medications for cough yielded mixed and largely negative results.

Antihistamines alone do not seem to work, and guaifenesin was successful in only one of three trials. Combinations of different drug classes appeared to be slightly more effective.

My personal favorite for the management of acute cough is something that kids generally love: honey. In a review of 14 studies, 9 of which were limited to pediatric patients, honey was associated with significant reductions in cough frequency, cough severity, and total symptom score. However, there was a moderate risk of bias in the included research, and evidence of honey’s benefit in placebo-controlled trials was limited. Honey used in this research came in a variety of forms, so the best dosage is uncertain.

Clearly, advancements are needed. Better symptom management in viral URI will almost certainly improve productivity across the population and will probably reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics as well. I have said for years that the scientists who can solve the Gordian knot of pediatric mucus deserve three Nobel prizes. I look forward to that golden day.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported a conflict of interest with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is it COVID-19, flu, or even RSV? I recently described just such a patient, an obese woman with type 2 diabetes, presenting with fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue. I asked readers whether they agreed with my management of this patient.

Thank you for your comments as we continue to react to high rates of URIs. Your comments highlight the importance of local resources and practice habits when managing patients with URI.

It was clear that readers value testing to distinguish between infections. However, access to testing is highly variable around the world and is likely to be routinely used only in high-income countries. The Kaiser Family Foundation performed a cost analysis of testing for SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 and found, not surprisingly, wide variability in the cost of testing. Medicare covers tests at rates of $36-$143 per test; a study of list prices for SARS-CoV-2 tests at 93 hospitals found a median cost of $148 per test. And this does not include collection or facility fees. About 20% of tests cost more than $300.

These costs are prohibitive for many health systems. However, more devices have been introduced since that analysis, and competition and evolving technology should drive down prices. Generally, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for multiple pathogens is less expensive than ordering two or three separate molecular tests and is more convenient for patients and practices alike.

Other reader comments focused on the challenges of getting accurate data on viral epidemiology, and there is certainly a time lag between infection trends and public health reports. This is exacerbated by underreporting of symptoms and more testing at home using antigen tests.

But please do not give up on epidemiology! If a test such as PCR is 90% sensitive for identifying infection, the yield in terms of the number of individuals infected with a particular virus should be high, and that is true when infection is in broad circulation. If 20% of a population of 1,000 has an infection and the test sensitivity is 90%, the yield of testing is 180 true cases versus 20 false positives.

However, if just 2% of the population of 1,000 has the infection in this same scenario, then only 18 true cases are identified. The effect on public health is certainly less, and a lower prevalence rate means that confounding variables, such as how long an individual might shed viral particles and the method of sample collection, have an outsized effect on results. This reduces the validity of diagnostic tests.

Even trends on a national level can provide some insight regarding whom to test. Traditionally, our practice has been to not routinely test patients for influenza or RSV from late spring to early fall unless there was a compelling reason, such as recent travel to an area where these infections were more prevalent. The loss of temporality for these infections since 2020 has altered this approach and made us pay more attention to reports from public health organizations.

I also appreciate the discussion of how to treat Agnes’s symptoms as she waits to improve, and anyone who suffers with or treats a viral URI knows that there are few interventions effective for such symptoms as cough and congestion. A systematic review of 29 randomized controlled trials of over-the-counter medications for cough yielded mixed and largely negative results.

Antihistamines alone do not seem to work, and guaifenesin was successful in only one of three trials. Combinations of different drug classes appeared to be slightly more effective.

My personal favorite for the management of acute cough is something that kids generally love: honey. In a review of 14 studies, 9 of which were limited to pediatric patients, honey was associated with significant reductions in cough frequency, cough severity, and total symptom score. However, there was a moderate risk of bias in the included research, and evidence of honey’s benefit in placebo-controlled trials was limited. Honey used in this research came in a variety of forms, so the best dosage is uncertain.

Clearly, advancements are needed. Better symptom management in viral URI will almost certainly improve productivity across the population and will probably reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics as well. I have said for years that the scientists who can solve the Gordian knot of pediatric mucus deserve three Nobel prizes. I look forward to that golden day.

Dr. Vega is a clinical professor of family medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He reported a conflict of interest with McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biden to end COVID emergencies in May

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

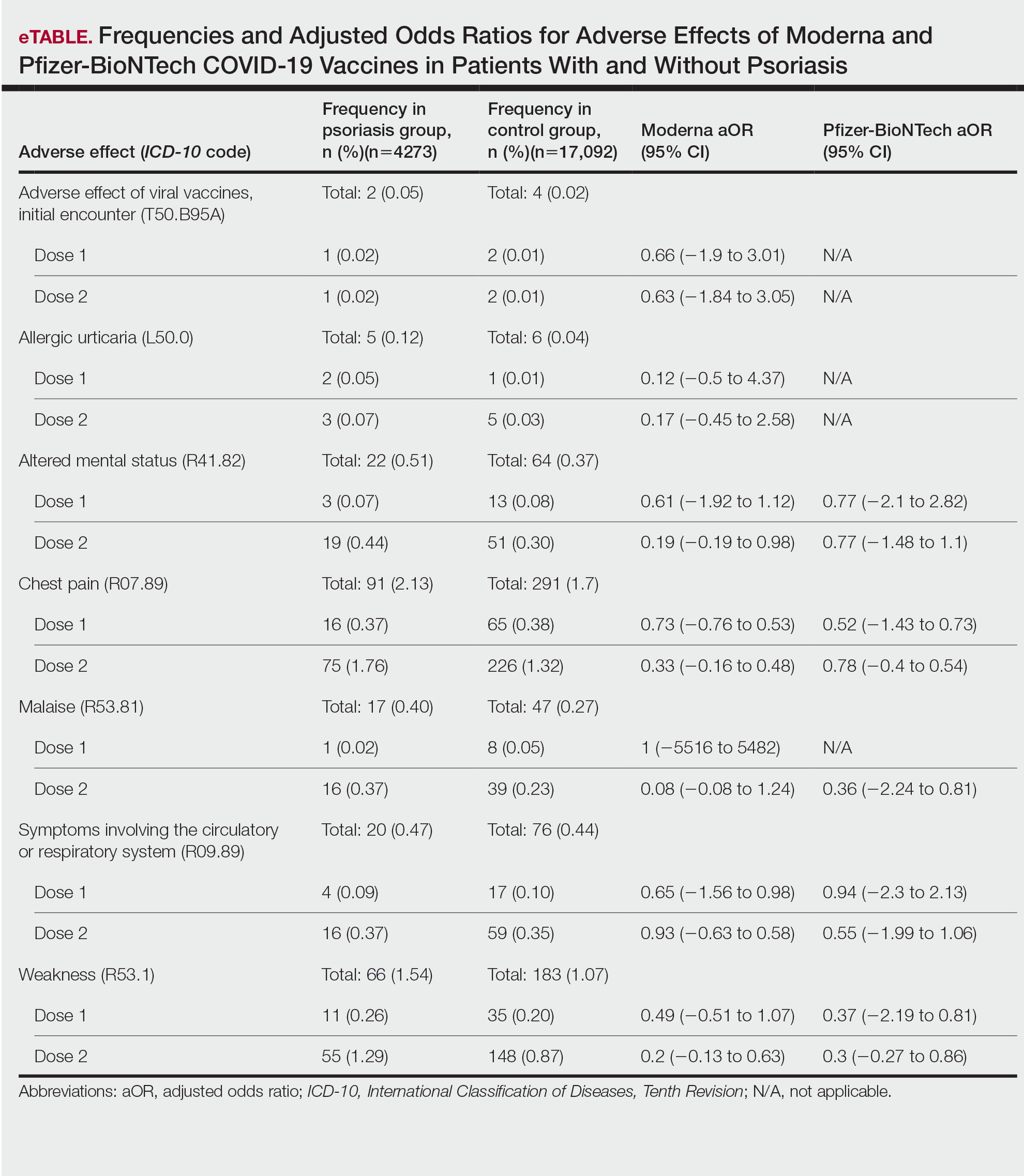

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

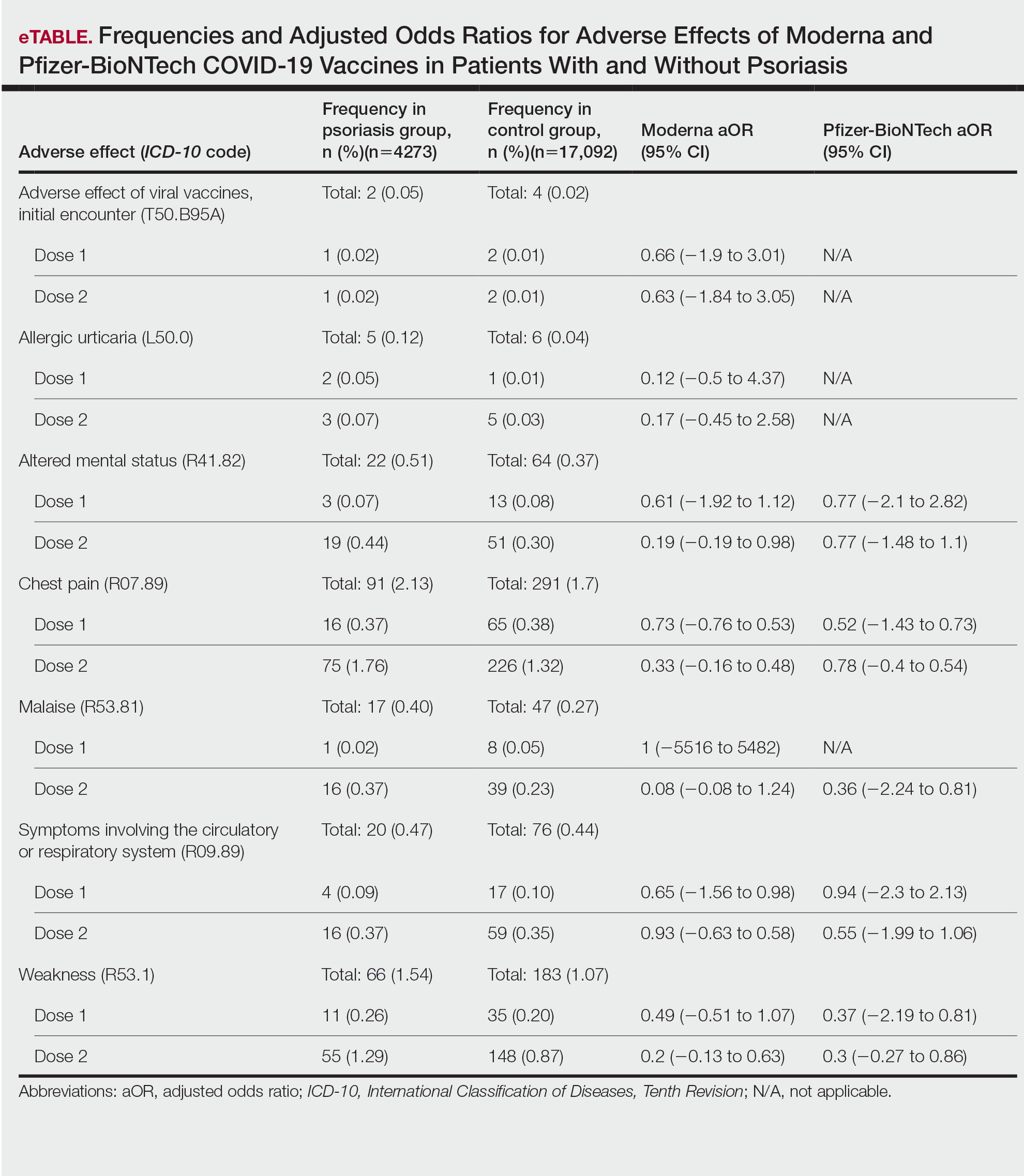

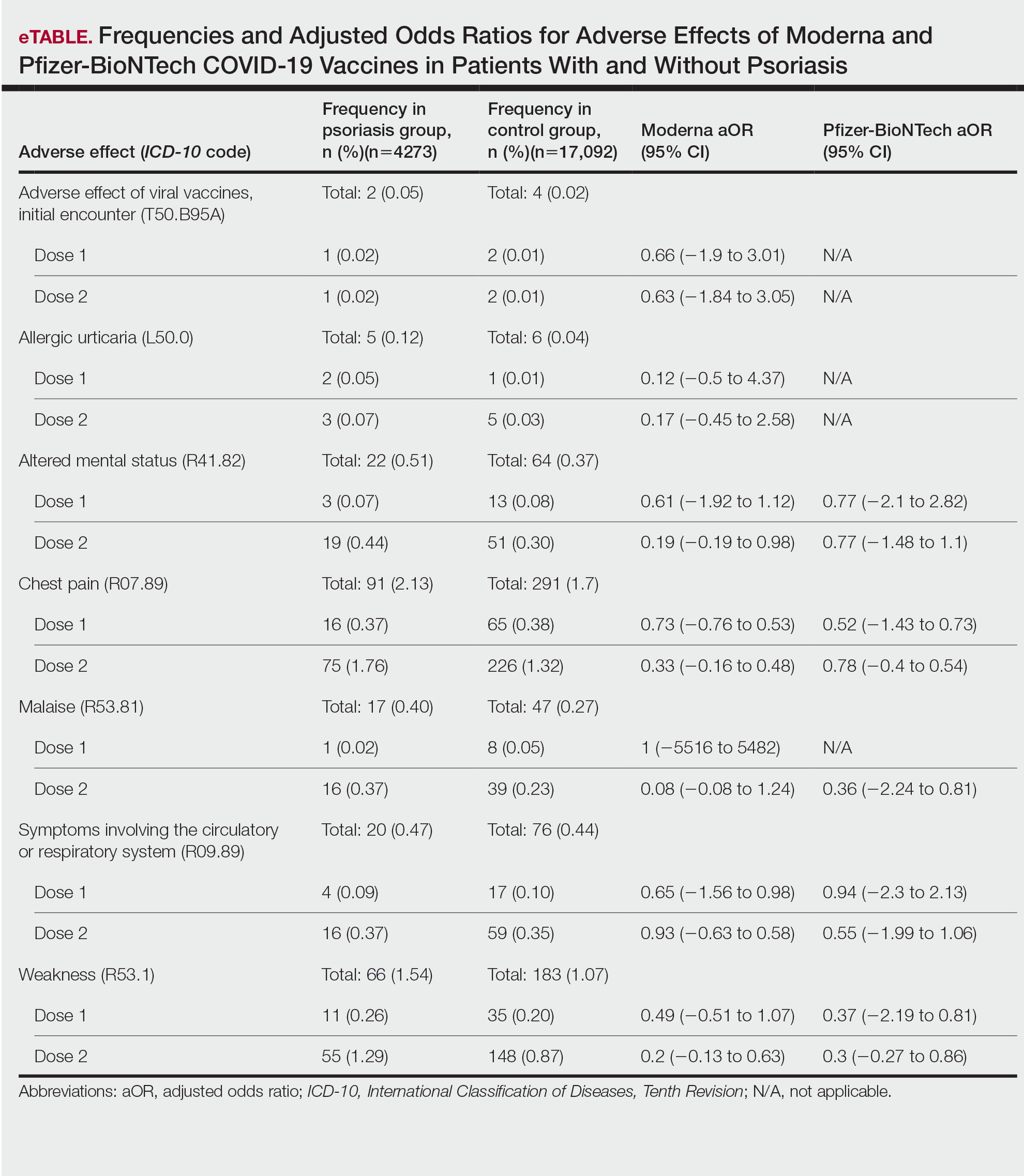

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

PRACTICE POINTS

- Patients who have psoriasis do not appear to have an increased incidence of adverse effects from messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines.

- Clinicians can safely recommend COVID-19 vaccines to patients who have psoriasis.

Long COVID affecting more than one-third of college students, faculty

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

FDA panel backs shift toward one-dose COVID shot

The FDA is looking to give clearer direction to vaccine makers about future development of COVID-19 vaccines. The plan is to narrow down the current complex landscape of options for vaccinations, and thus help increase use of these shots.

COVID remains a serious threat, causing about 4,000 deaths a week recently, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 21 members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) on Jan. 26 voted unanimously “yes” on a single question posed by the FDA:

“Does the committee recommend harmonizing the vaccine strain composition of primary series and booster doses in the U.S. to a single composition, e.g., the composition for all vaccines administered currently would be a bivalent vaccine (Original plus Omicron BA.4/BA.5)?”

In other words, would it be better to have one vaccine potentially combining multiple strains of the virus, instead of multiple vaccines – such as a two-shot primary series then a booster containing different combinations of viral strains.

The FDA will consider the panel’s advice as it outlines new strategies for keeping ahead of the evolving virus.

In explaining their support for the FDA plan, panel members said they hoped that a simpler regime would aid in persuading more people to get COVID vaccines.

Pamela McInnes, DDS, MSc, noted that it’s difficult to explain to many people that the vaccine works to protect them from more severe illness if they contract COVID after getting vaccinated.

“That is a real challenge,” said Dr. McInness, retired deputy director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health.

“The message that you would have gotten more sick and landed in the hospital resonates with me, but I’m not sure if it resonates with” many people who become infected, she said.

The plan

In the briefing document for the meeting, the FDA outlined a plan for transitioning from the current complex landscape of COVID-19 vaccines to a single vaccine composition for the primary series and booster vaccination.

This would require harmonizing the strain composition of all COVID-19 vaccines; simplifying the immunization schedule for future vaccination campaigns to administer a two-dose series in certain young children and in older adults and persons with compromised immunity, and only one dose in all other individuals; and establishing a process for vaccine strain selection recommendations, similar in many ways to that used for seasonal influenza vaccines, based on prevailing and predicted variants that would take place by June to allow for vaccine production by September.

During the discussion, though, questions arose about the June target date. Given the production schedule for some vaccines, that date might need to shift, said Jerry Weir, PhD, director of the division of viral products at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“We’re all just going to have to maintain flexibility,” Dr. Weir said, adding that there is not yet a “good pattern” established for updating these vaccines.

Increasing vaccination rates

There was broad consensus about the need to boost public support for COVID-19 vaccinations. While about 81% of the U.S. population has had at least one dose of this vaccine, only 15.3% have had an updated bivalent booster dose, according to the CDC.

“Anything that results in better public communication would be extremely valuable,” said committee member Henry H. Bernstein, DO, MHCM, of the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

But it’s unclear what expectations will be prioritized for the COVID vaccine program, he said.

“Realistically, I don’t think we can have it all – less infection, less transmission, less severe disease, and less long COVID,” Dr. Bernstein said. “And that seems to be a major challenge for public messaging.”

Panelists press for more data

Other committee members also pressed for clearer targets in evaluating the goals for COVID vaccines, and for more robust data.

Like his fellow VRBPAC members, Cody Meissner, MD, of Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, N.H., supported a move toward harmonizing the strains used in different companies’ vaccines. But he added that it wasn’t clear yet how frequently they should be administered.

“We need to see what happens with disease burden,” Dr. Meissner said. “We may or may not need annual vaccination. It’s just awfully early, it seems to me, in this process to answer that question.”

Among those serving on VRBPAC was one of the FDA’s more vocal critics on these points, Paul A. Offit, MD, a vaccine expert from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Offit, for example, joined former FDA officials in writing a November opinion article for the Washington Post, arguing that the evidence for boosters for healthy younger adults was not strong.

At the Jan. 26 meeting, he supported the drive toward simplification of COVID vaccine schedules, while arguing for more data about how well these products are working.

“This virus is going to be with us for years, if not decades, and there will always be vulnerable groups who are going to be hospitalized and killed by the virus,” Dr. Offit said.

The CDC needs to provide more information about the characteristics of people being hospitalized with COVID infections, including their ages and comorbidities as well as details about their vaccine history, he said. In addition, academic researchers should provide a clearer picture of what immunological predictors are at play in increasing people’s risk from COVID.

“Then and only then can we really best make the decision about who gets vaccinated with what and when,” Dr. Offit said.

VRBPAC member Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, also urged the FDA to press for a collection of more robust and detailed information about the immune response to COVID-19 vaccinations, such as a deeper look at what’s happening with antibodies.

“I hope FDA will continue to reflect on how to best take this information forward, and encourage – or require – sponsors to gather more information in a standardized way across these different arms of the human immune system,” Dr. Levy said. “So we keep learning and keep doing this better.”

In recapping the panel’s suggestions at the end of the meeting, Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, addressed the requests made during the day’s meeting about better data on how the vaccines work.

“We heard loud and clear that we need to use a data-driven approach to get to the simplest possible scheme that we can for vaccination,” Dr. Marks said. “And it should be as simple as possible but not oversimplified, a little bit like they say about Mozart’s music.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The FDA is looking to give clearer direction to vaccine makers about future development of COVID-19 vaccines. The plan is to narrow down the current complex landscape of options for vaccinations, and thus help increase use of these shots.

COVID remains a serious threat, causing about 4,000 deaths a week recently, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 21 members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) on Jan. 26 voted unanimously “yes” on a single question posed by the FDA:

“Does the committee recommend harmonizing the vaccine strain composition of primary series and booster doses in the U.S. to a single composition, e.g., the composition for all vaccines administered currently would be a bivalent vaccine (Original plus Omicron BA.4/BA.5)?”

In other words, would it be better to have one vaccine potentially combining multiple strains of the virus, instead of multiple vaccines – such as a two-shot primary series then a booster containing different combinations of viral strains.

The FDA will consider the panel’s advice as it outlines new strategies for keeping ahead of the evolving virus.

In explaining their support for the FDA plan, panel members said they hoped that a simpler regime would aid in persuading more people to get COVID vaccines.

Pamela McInnes, DDS, MSc, noted that it’s difficult to explain to many people that the vaccine works to protect them from more severe illness if they contract COVID after getting vaccinated.

“That is a real challenge,” said Dr. McInness, retired deputy director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health.

“The message that you would have gotten more sick and landed in the hospital resonates with me, but I’m not sure if it resonates with” many people who become infected, she said.

The plan

In the briefing document for the meeting, the FDA outlined a plan for transitioning from the current complex landscape of COVID-19 vaccines to a single vaccine composition for the primary series and booster vaccination.

This would require harmonizing the strain composition of all COVID-19 vaccines; simplifying the immunization schedule for future vaccination campaigns to administer a two-dose series in certain young children and in older adults and persons with compromised immunity, and only one dose in all other individuals; and establishing a process for vaccine strain selection recommendations, similar in many ways to that used for seasonal influenza vaccines, based on prevailing and predicted variants that would take place by June to allow for vaccine production by September.

During the discussion, though, questions arose about the June target date. Given the production schedule for some vaccines, that date might need to shift, said Jerry Weir, PhD, director of the division of viral products at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“We’re all just going to have to maintain flexibility,” Dr. Weir said, adding that there is not yet a “good pattern” established for updating these vaccines.

Increasing vaccination rates

There was broad consensus about the need to boost public support for COVID-19 vaccinations. While about 81% of the U.S. population has had at least one dose of this vaccine, only 15.3% have had an updated bivalent booster dose, according to the CDC.

“Anything that results in better public communication would be extremely valuable,” said committee member Henry H. Bernstein, DO, MHCM, of the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

But it’s unclear what expectations will be prioritized for the COVID vaccine program, he said.

“Realistically, I don’t think we can have it all – less infection, less transmission, less severe disease, and less long COVID,” Dr. Bernstein said. “And that seems to be a major challenge for public messaging.”

Panelists press for more data

Other committee members also pressed for clearer targets in evaluating the goals for COVID vaccines, and for more robust data.

Like his fellow VRBPAC members, Cody Meissner, MD, of Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, N.H., supported a move toward harmonizing the strains used in different companies’ vaccines. But he added that it wasn’t clear yet how frequently they should be administered.

“We need to see what happens with disease burden,” Dr. Meissner said. “We may or may not need annual vaccination. It’s just awfully early, it seems to me, in this process to answer that question.”

Among those serving on VRBPAC was one of the FDA’s more vocal critics on these points, Paul A. Offit, MD, a vaccine expert from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Offit, for example, joined former FDA officials in writing a November opinion article for the Washington Post, arguing that the evidence for boosters for healthy younger adults was not strong.

At the Jan. 26 meeting, he supported the drive toward simplification of COVID vaccine schedules, while arguing for more data about how well these products are working.

“This virus is going to be with us for years, if not decades, and there will always be vulnerable groups who are going to be hospitalized and killed by the virus,” Dr. Offit said.

The CDC needs to provide more information about the characteristics of people being hospitalized with COVID infections, including their ages and comorbidities as well as details about their vaccine history, he said. In addition, academic researchers should provide a clearer picture of what immunological predictors are at play in increasing people’s risk from COVID.

“Then and only then can we really best make the decision about who gets vaccinated with what and when,” Dr. Offit said.

VRBPAC member Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, also urged the FDA to press for a collection of more robust and detailed information about the immune response to COVID-19 vaccinations, such as a deeper look at what’s happening with antibodies.

“I hope FDA will continue to reflect on how to best take this information forward, and encourage – or require – sponsors to gather more information in a standardized way across these different arms of the human immune system,” Dr. Levy said. “So we keep learning and keep doing this better.”

In recapping the panel’s suggestions at the end of the meeting, Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, addressed the requests made during the day’s meeting about better data on how the vaccines work.

“We heard loud and clear that we need to use a data-driven approach to get to the simplest possible scheme that we can for vaccination,” Dr. Marks said. “And it should be as simple as possible but not oversimplified, a little bit like they say about Mozart’s music.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The FDA is looking to give clearer direction to vaccine makers about future development of COVID-19 vaccines. The plan is to narrow down the current complex landscape of options for vaccinations, and thus help increase use of these shots.

COVID remains a serious threat, causing about 4,000 deaths a week recently, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 21 members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) on Jan. 26 voted unanimously “yes” on a single question posed by the FDA:

“Does the committee recommend harmonizing the vaccine strain composition of primary series and booster doses in the U.S. to a single composition, e.g., the composition for all vaccines administered currently would be a bivalent vaccine (Original plus Omicron BA.4/BA.5)?”

In other words, would it be better to have one vaccine potentially combining multiple strains of the virus, instead of multiple vaccines – such as a two-shot primary series then a booster containing different combinations of viral strains.

The FDA will consider the panel’s advice as it outlines new strategies for keeping ahead of the evolving virus.

In explaining their support for the FDA plan, panel members said they hoped that a simpler regime would aid in persuading more people to get COVID vaccines.

Pamela McInnes, DDS, MSc, noted that it’s difficult to explain to many people that the vaccine works to protect them from more severe illness if they contract COVID after getting vaccinated.

“That is a real challenge,” said Dr. McInness, retired deputy director of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health.

“The message that you would have gotten more sick and landed in the hospital resonates with me, but I’m not sure if it resonates with” many people who become infected, she said.

The plan

In the briefing document for the meeting, the FDA outlined a plan for transitioning from the current complex landscape of COVID-19 vaccines to a single vaccine composition for the primary series and booster vaccination.

This would require harmonizing the strain composition of all COVID-19 vaccines; simplifying the immunization schedule for future vaccination campaigns to administer a two-dose series in certain young children and in older adults and persons with compromised immunity, and only one dose in all other individuals; and establishing a process for vaccine strain selection recommendations, similar in many ways to that used for seasonal influenza vaccines, based on prevailing and predicted variants that would take place by June to allow for vaccine production by September.

During the discussion, though, questions arose about the June target date. Given the production schedule for some vaccines, that date might need to shift, said Jerry Weir, PhD, director of the division of viral products at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“We’re all just going to have to maintain flexibility,” Dr. Weir said, adding that there is not yet a “good pattern” established for updating these vaccines.

Increasing vaccination rates

There was broad consensus about the need to boost public support for COVID-19 vaccinations. While about 81% of the U.S. population has had at least one dose of this vaccine, only 15.3% have had an updated bivalent booster dose, according to the CDC.

“Anything that results in better public communication would be extremely valuable,” said committee member Henry H. Bernstein, DO, MHCM, of the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y.

But it’s unclear what expectations will be prioritized for the COVID vaccine program, he said.

“Realistically, I don’t think we can have it all – less infection, less transmission, less severe disease, and less long COVID,” Dr. Bernstein said. “And that seems to be a major challenge for public messaging.”

Panelists press for more data

Other committee members also pressed for clearer targets in evaluating the goals for COVID vaccines, and for more robust data.

Like his fellow VRBPAC members, Cody Meissner, MD, of Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover, N.H., supported a move toward harmonizing the strains used in different companies’ vaccines. But he added that it wasn’t clear yet how frequently they should be administered.

“We need to see what happens with disease burden,” Dr. Meissner said. “We may or may not need annual vaccination. It’s just awfully early, it seems to me, in this process to answer that question.”

Among those serving on VRBPAC was one of the FDA’s more vocal critics on these points, Paul A. Offit, MD, a vaccine expert from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Offit, for example, joined former FDA officials in writing a November opinion article for the Washington Post, arguing that the evidence for boosters for healthy younger adults was not strong.

At the Jan. 26 meeting, he supported the drive toward simplification of COVID vaccine schedules, while arguing for more data about how well these products are working.

“This virus is going to be with us for years, if not decades, and there will always be vulnerable groups who are going to be hospitalized and killed by the virus,” Dr. Offit said.

The CDC needs to provide more information about the characteristics of people being hospitalized with COVID infections, including their ages and comorbidities as well as details about their vaccine history, he said. In addition, academic researchers should provide a clearer picture of what immunological predictors are at play in increasing people’s risk from COVID.

“Then and only then can we really best make the decision about who gets vaccinated with what and when,” Dr. Offit said.

VRBPAC member Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, also urged the FDA to press for a collection of more robust and detailed information about the immune response to COVID-19 vaccinations, such as a deeper look at what’s happening with antibodies.

“I hope FDA will continue to reflect on how to best take this information forward, and encourage – or require – sponsors to gather more information in a standardized way across these different arms of the human immune system,” Dr. Levy said. “So we keep learning and keep doing this better.”

In recapping the panel’s suggestions at the end of the meeting, Peter Marks, MD, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, addressed the requests made during the day’s meeting about better data on how the vaccines work.

“We heard loud and clear that we need to use a data-driven approach to get to the simplest possible scheme that we can for vaccination,” Dr. Marks said. “And it should be as simple as possible but not oversimplified, a little bit like they say about Mozart’s music.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA wants annual COVID boosters, just like annual flu shots

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are trending downward, according to the data tracker from the New York Times. Cases are down 28%, with 47,290 tallied daily. Hospitalizations are down 22%, with 37,474 daily. Deaths are down 4%, with an average of 489 per day as of Jan. 22.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are trending downward, according to the data tracker from the New York Times. Cases are down 28%, with 47,290 tallied daily. Hospitalizations are down 22%, with 37,474 daily. Deaths are down 4%, with an average of 489 per day as of Jan. 22.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.