User login

Long COVID ‘brain fog’ confounds doctors, but new research offers hope

Kate Whitley was petrified of COVID-19 from the beginning of the pandemic because she has Hashimoto disease, an autoimmune disorder that she knew put her at high risk for complications.

She was right to be worried. Two months after contracting the infection in September 2022, the 42-year-old Nashville resident was diagnosed with long COVID. For Ms. Whitley, the resulting brain fog has been the most challenging factor. She is the owner of a successful paper goods store, and she can’t remember basic aspects of her job. She can’t tolerate loud noises and gets so distracted that she has trouble remembering what she was doing.

Ms. Whitley doesn’t like the term “brain fog” because it doesn’t begin to describe the dramatic disruption to her life over the past 7 months.

Brain fog is among the most common symptoms of long COVID, and also one of the most poorly understood. A reported 46% of those diagnosed with long COVID complain of brain fog or a loss of memory. Many clinicians agree that the term is vague and often doesn’t truly represent the condition. That, in turn, makes it harder for doctors to diagnose and treat it. There are no standard tests for it, nor are there guidelines for symptom management or treatment.

“There’s a lot of imprecision in the term because it might mean different things to different patients,” said James C. Jackson, PsyD, a neuropsychiatrist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and author of a new book, “Clearing the Fog: From Surviving to Thriving With Long COVID – A Practical Guide.”

Dr. Jackson, who began treating Ms. Whitley in February 2023, said that it makes more sense to call brain fog a brain impairment or an acquired brain injury (ABI) because it doesn’t occur gradually. COVID damages the brain and causes injury. For those with long COVID who were previously in the intensive care unit and may have undergone ventilation, hypoxic brain injury may result from the lack of oxygen to the brain.

Even among those with milder cases of acute COVID, there’s some evidence that persistent neuroinflammation in the brain caused by an activated immune system may also cause damage.

In both cases, the results can be debilitating. Ms. Whitley also has dysautonomia – a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that can cause dizziness, sweating, and headaches along with fatigue and heart palpitations.

She said that she’s so forgetful that when she sees people socially, she’s nervous of what she’ll say. “I feel like I’m constantly sticking my foot in my mouth because I can’t remember details of other people’s lives,” she said.

Although brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia are marked by a slow decline, ABI occurs more suddenly and may include a loss of executive function and attention.

“With a brain injury, you’re doing fine, and then some event happens (in this case COVID), and immediately after that, your cognitive function is different,” said Dr. Jackson.

Additionally, ABI is an actual diagnosis, whereas brain fog is not.

“With a brain injury, there’s a treatment pathway for cognitive rehabilitation,” said Dr. Jackson.

Treatments may include speech, cognitive, and occupational therapy as well as meeting with a neuropsychiatrist for treatment of the mental and behavioral disorders that may result. Dr. Jackson said that while many patients aren’t functioning cognitively or physically at 100%, they can make enough strides that they don’t have to give up things such as driving and, in some cases, their jobs.

Other experts agree that long COVID may damage the brain. An April 2022 study published in the journal Nature found strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause brain-related abnormalities, for example, a reduction in gray matter in certain parts of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala.

Additionally, white matter, which is found deeper in the brain and is responsible for the exchange of information between different parts of the brain, may also be at risk of damage as a result of the virus, according to a November 2022 study published in the journal SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine.

Calling it a “fog” makes it easier for clinicians and the general public to dismiss its severity, said Tyler Reed Bell, PhD, a researcher who specializes in viruses that cause brain injury. He is a fellow in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. Brain fog can make driving and returning to work especially dangerous. Because of difficulty focusing, patients are much more likely to make mistakes that cause accidents.

“The COVID virus is very invasive to the brain,” Dr. Bell said.

Others contend this may be a rush to judgment. Karla L. Thompson, PhD, lead neuropsychologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s COVID Recovery Clinic, agrees that in more serious cases of COVID that cause a lack of oxygen to the brain, it’s reasonable to call it a brain injury. But brain fog can also be associated with other long COVID symptoms, not just damage to the brain.

Chronic fatigue and poor sleep are both commonly reported symptoms of long COVID that negatively affect brain function, she said. Sleep disturbances, cardiac problems, dysautonomia, and emotional distress could also affect the way the brain functions post COVID. Finding the right treatment requires identifying all the factors contributing to cognitive impairment.

Part of the problem in treating long COVID brain fog is that diagnostic technology is not sensitive enough to detect inflammation that could be causing damage.

Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, said her team is working on identifying biomarkers that could detect brain inflammation in a way similar to the manner researchers have identified biomarkers to help diagnose chronic fatigue syndrome. Additionally, a new study published last month in JAMA for the first time clearly defined 12 symptoms of long COVID, and brain fog was listed among them. All of this contributes to the development of clear diagnostic criteria.

“It will make a big difference once we have some consistency among clinicians in diagnosing the condition,” said Dr. McComsey.

Ms. Whitley is thankful for the treatment that she’s received thus far. She’s seeing a cognitive rehabilitation therapist, who assesses her memory, cognition, and attention span and gives her tools to break up simple tasks, such as driving, so that they don’t feel overwhelming. She’s back behind the wheel and back to work.

But perhaps most importantly, Ms. Whitley joined a support group, led by Dr. Jackson, that includes other people experiencing the same symptoms she is. When she was at her darkest, they understood.

“Talking to other survivors has been the only solace in all this,” Ms. Whitley said. “Together, we grieve all that’s been lost.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Kate Whitley was petrified of COVID-19 from the beginning of the pandemic because she has Hashimoto disease, an autoimmune disorder that she knew put her at high risk for complications.

She was right to be worried. Two months after contracting the infection in September 2022, the 42-year-old Nashville resident was diagnosed with long COVID. For Ms. Whitley, the resulting brain fog has been the most challenging factor. She is the owner of a successful paper goods store, and she can’t remember basic aspects of her job. She can’t tolerate loud noises and gets so distracted that she has trouble remembering what she was doing.

Ms. Whitley doesn’t like the term “brain fog” because it doesn’t begin to describe the dramatic disruption to her life over the past 7 months.

Brain fog is among the most common symptoms of long COVID, and also one of the most poorly understood. A reported 46% of those diagnosed with long COVID complain of brain fog or a loss of memory. Many clinicians agree that the term is vague and often doesn’t truly represent the condition. That, in turn, makes it harder for doctors to diagnose and treat it. There are no standard tests for it, nor are there guidelines for symptom management or treatment.

“There’s a lot of imprecision in the term because it might mean different things to different patients,” said James C. Jackson, PsyD, a neuropsychiatrist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and author of a new book, “Clearing the Fog: From Surviving to Thriving With Long COVID – A Practical Guide.”

Dr. Jackson, who began treating Ms. Whitley in February 2023, said that it makes more sense to call brain fog a brain impairment or an acquired brain injury (ABI) because it doesn’t occur gradually. COVID damages the brain and causes injury. For those with long COVID who were previously in the intensive care unit and may have undergone ventilation, hypoxic brain injury may result from the lack of oxygen to the brain.

Even among those with milder cases of acute COVID, there’s some evidence that persistent neuroinflammation in the brain caused by an activated immune system may also cause damage.

In both cases, the results can be debilitating. Ms. Whitley also has dysautonomia – a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that can cause dizziness, sweating, and headaches along with fatigue and heart palpitations.

She said that she’s so forgetful that when she sees people socially, she’s nervous of what she’ll say. “I feel like I’m constantly sticking my foot in my mouth because I can’t remember details of other people’s lives,” she said.

Although brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia are marked by a slow decline, ABI occurs more suddenly and may include a loss of executive function and attention.

“With a brain injury, you’re doing fine, and then some event happens (in this case COVID), and immediately after that, your cognitive function is different,” said Dr. Jackson.

Additionally, ABI is an actual diagnosis, whereas brain fog is not.

“With a brain injury, there’s a treatment pathway for cognitive rehabilitation,” said Dr. Jackson.

Treatments may include speech, cognitive, and occupational therapy as well as meeting with a neuropsychiatrist for treatment of the mental and behavioral disorders that may result. Dr. Jackson said that while many patients aren’t functioning cognitively or physically at 100%, they can make enough strides that they don’t have to give up things such as driving and, in some cases, their jobs.

Other experts agree that long COVID may damage the brain. An April 2022 study published in the journal Nature found strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause brain-related abnormalities, for example, a reduction in gray matter in certain parts of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala.

Additionally, white matter, which is found deeper in the brain and is responsible for the exchange of information between different parts of the brain, may also be at risk of damage as a result of the virus, according to a November 2022 study published in the journal SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine.

Calling it a “fog” makes it easier for clinicians and the general public to dismiss its severity, said Tyler Reed Bell, PhD, a researcher who specializes in viruses that cause brain injury. He is a fellow in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. Brain fog can make driving and returning to work especially dangerous. Because of difficulty focusing, patients are much more likely to make mistakes that cause accidents.

“The COVID virus is very invasive to the brain,” Dr. Bell said.

Others contend this may be a rush to judgment. Karla L. Thompson, PhD, lead neuropsychologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s COVID Recovery Clinic, agrees that in more serious cases of COVID that cause a lack of oxygen to the brain, it’s reasonable to call it a brain injury. But brain fog can also be associated with other long COVID symptoms, not just damage to the brain.

Chronic fatigue and poor sleep are both commonly reported symptoms of long COVID that negatively affect brain function, she said. Sleep disturbances, cardiac problems, dysautonomia, and emotional distress could also affect the way the brain functions post COVID. Finding the right treatment requires identifying all the factors contributing to cognitive impairment.

Part of the problem in treating long COVID brain fog is that diagnostic technology is not sensitive enough to detect inflammation that could be causing damage.

Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, said her team is working on identifying biomarkers that could detect brain inflammation in a way similar to the manner researchers have identified biomarkers to help diagnose chronic fatigue syndrome. Additionally, a new study published last month in JAMA for the first time clearly defined 12 symptoms of long COVID, and brain fog was listed among them. All of this contributes to the development of clear diagnostic criteria.

“It will make a big difference once we have some consistency among clinicians in diagnosing the condition,” said Dr. McComsey.

Ms. Whitley is thankful for the treatment that she’s received thus far. She’s seeing a cognitive rehabilitation therapist, who assesses her memory, cognition, and attention span and gives her tools to break up simple tasks, such as driving, so that they don’t feel overwhelming. She’s back behind the wheel and back to work.

But perhaps most importantly, Ms. Whitley joined a support group, led by Dr. Jackson, that includes other people experiencing the same symptoms she is. When she was at her darkest, they understood.

“Talking to other survivors has been the only solace in all this,” Ms. Whitley said. “Together, we grieve all that’s been lost.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Kate Whitley was petrified of COVID-19 from the beginning of the pandemic because she has Hashimoto disease, an autoimmune disorder that she knew put her at high risk for complications.

She was right to be worried. Two months after contracting the infection in September 2022, the 42-year-old Nashville resident was diagnosed with long COVID. For Ms. Whitley, the resulting brain fog has been the most challenging factor. She is the owner of a successful paper goods store, and she can’t remember basic aspects of her job. She can’t tolerate loud noises and gets so distracted that she has trouble remembering what she was doing.

Ms. Whitley doesn’t like the term “brain fog” because it doesn’t begin to describe the dramatic disruption to her life over the past 7 months.

Brain fog is among the most common symptoms of long COVID, and also one of the most poorly understood. A reported 46% of those diagnosed with long COVID complain of brain fog or a loss of memory. Many clinicians agree that the term is vague and often doesn’t truly represent the condition. That, in turn, makes it harder for doctors to diagnose and treat it. There are no standard tests for it, nor are there guidelines for symptom management or treatment.

“There’s a lot of imprecision in the term because it might mean different things to different patients,” said James C. Jackson, PsyD, a neuropsychiatrist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and author of a new book, “Clearing the Fog: From Surviving to Thriving With Long COVID – A Practical Guide.”

Dr. Jackson, who began treating Ms. Whitley in February 2023, said that it makes more sense to call brain fog a brain impairment or an acquired brain injury (ABI) because it doesn’t occur gradually. COVID damages the brain and causes injury. For those with long COVID who were previously in the intensive care unit and may have undergone ventilation, hypoxic brain injury may result from the lack of oxygen to the brain.

Even among those with milder cases of acute COVID, there’s some evidence that persistent neuroinflammation in the brain caused by an activated immune system may also cause damage.

In both cases, the results can be debilitating. Ms. Whitley also has dysautonomia – a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that can cause dizziness, sweating, and headaches along with fatigue and heart palpitations.

She said that she’s so forgetful that when she sees people socially, she’s nervous of what she’ll say. “I feel like I’m constantly sticking my foot in my mouth because I can’t remember details of other people’s lives,” she said.

Although brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia are marked by a slow decline, ABI occurs more suddenly and may include a loss of executive function and attention.

“With a brain injury, you’re doing fine, and then some event happens (in this case COVID), and immediately after that, your cognitive function is different,” said Dr. Jackson.

Additionally, ABI is an actual diagnosis, whereas brain fog is not.

“With a brain injury, there’s a treatment pathway for cognitive rehabilitation,” said Dr. Jackson.

Treatments may include speech, cognitive, and occupational therapy as well as meeting with a neuropsychiatrist for treatment of the mental and behavioral disorders that may result. Dr. Jackson said that while many patients aren’t functioning cognitively or physically at 100%, they can make enough strides that they don’t have to give up things such as driving and, in some cases, their jobs.

Other experts agree that long COVID may damage the brain. An April 2022 study published in the journal Nature found strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause brain-related abnormalities, for example, a reduction in gray matter in certain parts of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala.

Additionally, white matter, which is found deeper in the brain and is responsible for the exchange of information between different parts of the brain, may also be at risk of damage as a result of the virus, according to a November 2022 study published in the journal SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine.

Calling it a “fog” makes it easier for clinicians and the general public to dismiss its severity, said Tyler Reed Bell, PhD, a researcher who specializes in viruses that cause brain injury. He is a fellow in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. Brain fog can make driving and returning to work especially dangerous. Because of difficulty focusing, patients are much more likely to make mistakes that cause accidents.

“The COVID virus is very invasive to the brain,” Dr. Bell said.

Others contend this may be a rush to judgment. Karla L. Thompson, PhD, lead neuropsychologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s COVID Recovery Clinic, agrees that in more serious cases of COVID that cause a lack of oxygen to the brain, it’s reasonable to call it a brain injury. But brain fog can also be associated with other long COVID symptoms, not just damage to the brain.

Chronic fatigue and poor sleep are both commonly reported symptoms of long COVID that negatively affect brain function, she said. Sleep disturbances, cardiac problems, dysautonomia, and emotional distress could also affect the way the brain functions post COVID. Finding the right treatment requires identifying all the factors contributing to cognitive impairment.

Part of the problem in treating long COVID brain fog is that diagnostic technology is not sensitive enough to detect inflammation that could be causing damage.

Grace McComsey, MD, who leads the long COVID RECOVER study at University Hospitals Health System in Cleveland, said her team is working on identifying biomarkers that could detect brain inflammation in a way similar to the manner researchers have identified biomarkers to help diagnose chronic fatigue syndrome. Additionally, a new study published last month in JAMA for the first time clearly defined 12 symptoms of long COVID, and brain fog was listed among them. All of this contributes to the development of clear diagnostic criteria.

“It will make a big difference once we have some consistency among clinicians in diagnosing the condition,” said Dr. McComsey.

Ms. Whitley is thankful for the treatment that she’s received thus far. She’s seeing a cognitive rehabilitation therapist, who assesses her memory, cognition, and attention span and gives her tools to break up simple tasks, such as driving, so that they don’t feel overwhelming. She’s back behind the wheel and back to work.

But perhaps most importantly, Ms. Whitley joined a support group, led by Dr. Jackson, that includes other people experiencing the same symptoms she is. When she was at her darkest, they understood.

“Talking to other survivors has been the only solace in all this,” Ms. Whitley said. “Together, we grieve all that’s been lost.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Postacute effects of COVID on par with those of sepsis, flu

A large observational study examined population-wide data for 13 postacute conditions in patients who had been hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection and found that all but one of these conditions, venous thromboembolism, occurred at comparable rates in those hospitalized for sepsis and influenza.

“For us, the main takeaway was that patients hospitalized for severe illness in general really require ongoing treatment and support after they’re discharged. That type of care is often very challenging to coordinate for people in a sometimes siloed and fragmented health care system,” study author Kieran Quinn, MD, PhD, a clinician at Sinai Health in Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview.

The study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Postacute effects

The investigators compared clinical and health administrative data from 26,499 Ontarians hospitalized with COVID-19 with data from three additional cohorts who had been hospitalized with influenza (17,516 patients) and sepsis. The sepsis cohort was divided into two groups, those hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic (52,878 patients) and a historical control population (282,473 patients).

These comparators allowed the researchers to compare COVID-19 with other severe infectious illnesses and control for any changes in health care delivery that may have occurred during the pandemic. The addition of sepsis cohorts was needed for the latter purpose, since influenza rates dropped significantly after the onset of the pandemic.

The study outcomes (including cardiovascular, neurological, and mental health conditions and rheumatoid arthritis) were selected based on previous associations with COVID-19 infections, as well as their availability in the data, according to Dr. Quinn. The investigators used diagnostic codes recorded in Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences database. The investigators observed some of the studied conditions in their own patients. “Many of us on the research team are practicing clinicians who care for people living with long COVID,” said Dr. Quinn.

Compared with cohorts with other serious infections, those hospitalized with COVID-19 were not at increased risk for selected cardiovascular or neurological disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, or mental health conditions within 1 year following hospitalization. Incident venous thromboembolic disease, however, was more common after hospitalization for COVID-19 than after hospitalization for influenza (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.77).

The study results corroborate previous findings that influenza and sepsis can have serious long-term health effects, such as heart failure, dementia, and depression, and found that the same was true for COVID-19 infections. For all three infections, patients at high risk require additional support after their initial discharge.

Defining long COVID

Although there was no increased risk with COVID-19 for most conditions, these results do not mean that the postacute effects of the infection, often called “long COVID,” are not significant, Dr. Quinn emphasized. The researcher believes that it’s important to listen to the many patients reporting symptoms and validate their experiences.

There needs to be greater consensus among the global health community on what constitutes long COVID. While the research led by Dr. Quinn focuses on postacute health conditions, some definitions of long COVID, such as that of the World Health Organization, refer only to ongoing symptoms of the original infection.

While there is now a diagnostic code for treating long COVID in Ontario, the data available to the researchers did not include information on some common symptoms of post-COVID condition, like chronic fatigue. In the data used, there was not an accurate way to identify patients who had developed conditions like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, said Dr. Quinn.

In addition to creating clear definitions and determining the best treatments, prevention is essential, said Dr. Quinn. Prior studies have shown that vaccination helps prevent ICU admission for COVID-19.

‘Important questions remain’

Commenting on the finding, Aravind Ganesh, MD, DPhil, a neurologist at the University of Calgary (Alta.), said that by including control populations, the study addressed an important limitation of previous research. Dr. Ganesh, who was not involved in the study, said that the controls help to determine the cause of associations found in other studies, including his own research on long-term symptoms following outpatient care for COVID-19.

“I think what this tells us is that maybe a lot of the issues that we’ve been seeing as complications attributable to COVID are, in fact, complications attributable to serious illness,” said Dr. Ganesh. He also found the association with venous thromboembolism interesting because the condition is recognized as a key risk factor for COVID-19 outcomes.

Compared with smaller randomized control trials, the population-level data provided a much larger sample size for the study. However, this design comes with limitations as well, Dr. Ganesh noted. The study relies on the administrative data of diagnostic codes and misses symptoms that aren’t associated with a diagnosis. In addition, because the cohorts were not assigned randomly, it may not account for preexisting risk factors.

While the study demonstrates associations with physical and mental health conditions, the cause of postacute effects from COVID-19, influenza, and sepsis is still unclear. “Important questions remain,” said Dr. Ganesh. “Why is it that these patients are experiencing these symptoms?”

The study was supported by ICES and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Quinn reported part-time employment at Public Health Ontario and stock in Pfizer and BioNTech. Dr. Ganesh reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large observational study examined population-wide data for 13 postacute conditions in patients who had been hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection and found that all but one of these conditions, venous thromboembolism, occurred at comparable rates in those hospitalized for sepsis and influenza.

“For us, the main takeaway was that patients hospitalized for severe illness in general really require ongoing treatment and support after they’re discharged. That type of care is often very challenging to coordinate for people in a sometimes siloed and fragmented health care system,” study author Kieran Quinn, MD, PhD, a clinician at Sinai Health in Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview.

The study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Postacute effects

The investigators compared clinical and health administrative data from 26,499 Ontarians hospitalized with COVID-19 with data from three additional cohorts who had been hospitalized with influenza (17,516 patients) and sepsis. The sepsis cohort was divided into two groups, those hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic (52,878 patients) and a historical control population (282,473 patients).

These comparators allowed the researchers to compare COVID-19 with other severe infectious illnesses and control for any changes in health care delivery that may have occurred during the pandemic. The addition of sepsis cohorts was needed for the latter purpose, since influenza rates dropped significantly after the onset of the pandemic.

The study outcomes (including cardiovascular, neurological, and mental health conditions and rheumatoid arthritis) were selected based on previous associations with COVID-19 infections, as well as their availability in the data, according to Dr. Quinn. The investigators used diagnostic codes recorded in Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences database. The investigators observed some of the studied conditions in their own patients. “Many of us on the research team are practicing clinicians who care for people living with long COVID,” said Dr. Quinn.

Compared with cohorts with other serious infections, those hospitalized with COVID-19 were not at increased risk for selected cardiovascular or neurological disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, or mental health conditions within 1 year following hospitalization. Incident venous thromboembolic disease, however, was more common after hospitalization for COVID-19 than after hospitalization for influenza (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.77).

The study results corroborate previous findings that influenza and sepsis can have serious long-term health effects, such as heart failure, dementia, and depression, and found that the same was true for COVID-19 infections. For all three infections, patients at high risk require additional support after their initial discharge.

Defining long COVID

Although there was no increased risk with COVID-19 for most conditions, these results do not mean that the postacute effects of the infection, often called “long COVID,” are not significant, Dr. Quinn emphasized. The researcher believes that it’s important to listen to the many patients reporting symptoms and validate their experiences.

There needs to be greater consensus among the global health community on what constitutes long COVID. While the research led by Dr. Quinn focuses on postacute health conditions, some definitions of long COVID, such as that of the World Health Organization, refer only to ongoing symptoms of the original infection.

While there is now a diagnostic code for treating long COVID in Ontario, the data available to the researchers did not include information on some common symptoms of post-COVID condition, like chronic fatigue. In the data used, there was not an accurate way to identify patients who had developed conditions like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, said Dr. Quinn.

In addition to creating clear definitions and determining the best treatments, prevention is essential, said Dr. Quinn. Prior studies have shown that vaccination helps prevent ICU admission for COVID-19.

‘Important questions remain’

Commenting on the finding, Aravind Ganesh, MD, DPhil, a neurologist at the University of Calgary (Alta.), said that by including control populations, the study addressed an important limitation of previous research. Dr. Ganesh, who was not involved in the study, said that the controls help to determine the cause of associations found in other studies, including his own research on long-term symptoms following outpatient care for COVID-19.

“I think what this tells us is that maybe a lot of the issues that we’ve been seeing as complications attributable to COVID are, in fact, complications attributable to serious illness,” said Dr. Ganesh. He also found the association with venous thromboembolism interesting because the condition is recognized as a key risk factor for COVID-19 outcomes.

Compared with smaller randomized control trials, the population-level data provided a much larger sample size for the study. However, this design comes with limitations as well, Dr. Ganesh noted. The study relies on the administrative data of diagnostic codes and misses symptoms that aren’t associated with a diagnosis. In addition, because the cohorts were not assigned randomly, it may not account for preexisting risk factors.

While the study demonstrates associations with physical and mental health conditions, the cause of postacute effects from COVID-19, influenza, and sepsis is still unclear. “Important questions remain,” said Dr. Ganesh. “Why is it that these patients are experiencing these symptoms?”

The study was supported by ICES and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Quinn reported part-time employment at Public Health Ontario and stock in Pfizer and BioNTech. Dr. Ganesh reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large observational study examined population-wide data for 13 postacute conditions in patients who had been hospitalized with a COVID-19 infection and found that all but one of these conditions, venous thromboembolism, occurred at comparable rates in those hospitalized for sepsis and influenza.

“For us, the main takeaway was that patients hospitalized for severe illness in general really require ongoing treatment and support after they’re discharged. That type of care is often very challenging to coordinate for people in a sometimes siloed and fragmented health care system,” study author Kieran Quinn, MD, PhD, a clinician at Sinai Health in Toronto, and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, said in an interview.

The study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Postacute effects

The investigators compared clinical and health administrative data from 26,499 Ontarians hospitalized with COVID-19 with data from three additional cohorts who had been hospitalized with influenza (17,516 patients) and sepsis. The sepsis cohort was divided into two groups, those hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic (52,878 patients) and a historical control population (282,473 patients).

These comparators allowed the researchers to compare COVID-19 with other severe infectious illnesses and control for any changes in health care delivery that may have occurred during the pandemic. The addition of sepsis cohorts was needed for the latter purpose, since influenza rates dropped significantly after the onset of the pandemic.

The study outcomes (including cardiovascular, neurological, and mental health conditions and rheumatoid arthritis) were selected based on previous associations with COVID-19 infections, as well as their availability in the data, according to Dr. Quinn. The investigators used diagnostic codes recorded in Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences database. The investigators observed some of the studied conditions in their own patients. “Many of us on the research team are practicing clinicians who care for people living with long COVID,” said Dr. Quinn.

Compared with cohorts with other serious infections, those hospitalized with COVID-19 were not at increased risk for selected cardiovascular or neurological disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, or mental health conditions within 1 year following hospitalization. Incident venous thromboembolic disease, however, was more common after hospitalization for COVID-19 than after hospitalization for influenza (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.77).

The study results corroborate previous findings that influenza and sepsis can have serious long-term health effects, such as heart failure, dementia, and depression, and found that the same was true for COVID-19 infections. For all three infections, patients at high risk require additional support after their initial discharge.

Defining long COVID

Although there was no increased risk with COVID-19 for most conditions, these results do not mean that the postacute effects of the infection, often called “long COVID,” are not significant, Dr. Quinn emphasized. The researcher believes that it’s important to listen to the many patients reporting symptoms and validate their experiences.

There needs to be greater consensus among the global health community on what constitutes long COVID. While the research led by Dr. Quinn focuses on postacute health conditions, some definitions of long COVID, such as that of the World Health Organization, refer only to ongoing symptoms of the original infection.

While there is now a diagnostic code for treating long COVID in Ontario, the data available to the researchers did not include information on some common symptoms of post-COVID condition, like chronic fatigue. In the data used, there was not an accurate way to identify patients who had developed conditions like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, said Dr. Quinn.

In addition to creating clear definitions and determining the best treatments, prevention is essential, said Dr. Quinn. Prior studies have shown that vaccination helps prevent ICU admission for COVID-19.

‘Important questions remain’

Commenting on the finding, Aravind Ganesh, MD, DPhil, a neurologist at the University of Calgary (Alta.), said that by including control populations, the study addressed an important limitation of previous research. Dr. Ganesh, who was not involved in the study, said that the controls help to determine the cause of associations found in other studies, including his own research on long-term symptoms following outpatient care for COVID-19.

“I think what this tells us is that maybe a lot of the issues that we’ve been seeing as complications attributable to COVID are, in fact, complications attributable to serious illness,” said Dr. Ganesh. He also found the association with venous thromboembolism interesting because the condition is recognized as a key risk factor for COVID-19 outcomes.

Compared with smaller randomized control trials, the population-level data provided a much larger sample size for the study. However, this design comes with limitations as well, Dr. Ganesh noted. The study relies on the administrative data of diagnostic codes and misses symptoms that aren’t associated with a diagnosis. In addition, because the cohorts were not assigned randomly, it may not account for preexisting risk factors.

While the study demonstrates associations with physical and mental health conditions, the cause of postacute effects from COVID-19, influenza, and sepsis is still unclear. “Important questions remain,” said Dr. Ganesh. “Why is it that these patients are experiencing these symptoms?”

The study was supported by ICES and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Quinn reported part-time employment at Public Health Ontario and stock in Pfizer and BioNTech. Dr. Ganesh reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

COVID-19 Incidence After Emergency Department Visit

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, patient encounters with the health care system plummeted.1-3 The perceived increased risk of contracting COVID-19 while obtaining care was thought to be a contributing factor. In outpatient settings, one study noted a 63% decrease in visits to otolaryngology visits in Massachusetts, and another noted a 33% decrease in dental office visits at the onset of the pandemic in 2020 compared with the same time frame in 2019.2,4 Along with mask mandates and stay-at-home orders, various institutions sought to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 through different protocols, including the use of social distancing, limitation of visitors, and telehealth. Despite some of these measures, nosocomial infections were not uncommon. For example, one hospital in the United Kingdom reported that 15% of COVID-19 inpatient cases in a 6-week period in 2020 were probably or definitely hospital acquired. These patients had a 36% case fatality rate.5

Unlike outpatient treatment centers, however, the emergency department (ED) is mandated by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act to provide a medical screening examination and to stabilize emergency medical conditions to all patients presenting to the ED. Thus, high numbers of undifferentiated and symptomatic patients are forced to congregate in EDs, increasing the risk of transmission of COVID-19. This perception of increased risk led to a 42% decrease in ED visits during March and April 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Correspondingly, there was a 20% decrease in code stroke activations at a hospital in Canada and a 38% decrease in ST-elevation myocardial infarction activations across 9 United States hospital systems.6,7

Limited studies have been conducted to date to determine whether contracting COVID-19 while in the ED is a risk. One retrospective case-control study evaluating 39 EDs in the US showed that ED colocation with known patients with COVID-19 was not associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 transmission.5 However, this study also recognized that infection control strategies widely varied by location and date.

In this study, we report the incidence of COVID-19 infections within 21 days after the initial visit for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection to the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) ED and compared it with that of COVID-19 infections for tests performed within the VAGLAHS.

Program Description

As a quality improvement measure, the

Patients with specific symptoms noted during triage, such as those associated with COVID-19 diagnosis, respiratory infections, fever, and/or myalgias, were isolated in their own patient room. Electronic tablets were used for persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 to communicate with family and/or medical staff who did not need to enter the patient’s room. Two-hour disinfection protocols were instituted for high-risk patients who were moved during the course of their treatment (ie, transfer to another bed for admission or discharge). All staff was specifically trained in personal protective equipment (PPE) donning and doffing, and 2-physician airway teams were implemented to ensure proper PPE use and safe COVID-19 intubations.

COVID-19 Infections

Electronic health records of patients who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not related to COVID-19 were reviewed from

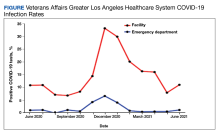

A total of 8708 patients who came to the ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection and had a COVID-19 test within 21 days of the ED visit met the inclusion criteria. The overall average positivity rate at the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection was 1.1% from June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021. The positivity rate by month ranged from 0% to 6.7% for this period (Figure).

Discussion

Implementing COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED helped minimize exposure and subsequent infection of COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection. Contextualizing this with the overall average monthly positivity rate of veterans in the VAGLAHS catchment area (10.9%) or Los Angeles County (7.9%) between June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021, veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection were less likely to test positive for COVID-19 within 21 days (1.1%), suggesting that the extensive measures taken at the VAGLAHS ED were effective.8

Many health care systems in the US and abroad have experimented with different transmission mitigation strategies in the ED. These tactics have included careful resource allocation when PPE shortages occur, incorporation of airway teams with appropriate safety measures to reduce nosocomial spread to health care workers, and use of a cohorting plan to separate persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 from other patients.9-15 Additionally, forward screening areas were incorporated similar to the COVID-19 tent that was instituted at the VAGLAHS ED to manage patients who were referred to the ED for COVID-19 testing during the beginning of the pandemic, which prevented symptomatic patients from congregating with asymptomatic patients.14,15

Encouragingly, some of these studies reported no cases of nosocomial transmission in the ED.11,13 In a separate study, 14 clusters of COVID-19 cases were identified at one VA health care system in which nosocomial transmission was suspected, including one in the ED.16 Using contact tracing, no patients and 9 employees were found to have contracted COVID-19 in that cluster. Overall, among all clusters examined within the health care system, either by contact tracing or by whole-genome sequencing, the authors found that transmission from health care personnel to patients was rare. Despite different methodologies, we also similarly found that ED patients in our VA facility were unlikely to become infected with COVID-19.

While the low incidence of positive COVID-19 tests cannot be attributed to any one method, our data provide a working blueprint for enhanced ED precautions in future surges of COVID-19 or other airborne diseases, including that of future pandemics.

Limitations

Notably, although the VA is the largest health care system in the US, a considerable number of veterans may present to non-VA EDs to seek care, and thus their data are not included here; these veterans may live farther from a VA facility or experience higher barriers to care than veterans who exclusively or almost exclusively seek care within the VA. As a result, we are unable to account for COVID-19 tests completed outside the VA. Moreover, the wild type SARS-CoV-2 virus was dominant during the time frame chosen for this assessment, and data may not be generalizable to other variants (eg, omicron) that are known to be more highly transmissible.17 Lastly, although our observation was performed at a single VA ED and may not apply to other facilities, especially in light of different mitigation strategies, our findings still provide support for approaches to minimizing patient and staff exposure to COVID-19 in ED settings.

Conclusions

Implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED may have minimized exposure to COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 and did not put one at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Taken together, our data suggest that patients should not avoid seeking emergency care out of fear of contracting COVID-19 if EDs have adequately instituted mitigation techniques.

1. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al; National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699-704. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1

2. Fan T, Workman AD, Miller LE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on otolaryngology community practice in Massachusetts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(3):424-430. doi:10.1177/0194599820983732

3. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

4. Kranz AM, Chen A, Gahlon G, Stein BD. 2020 trends in dental office visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(7):535-541,e1. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2021.02.01

5. Ridgway JP, Robicsek AA. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) acquisition among emergency department patients: a retrospective case control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(1):105-107. doi:10.1017/ice.2020.1224

6. Bres Bullrich M, Fridman S, Mandzia JL, et al. COVID-19: stroke admissions, emergency department visits, and prevention clinic referrals. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47(5):693-696. doi:10.1017/cjn.2020.101

7. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871-2872. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011

8. LA County COVID-19 Surveillance Dashboard. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://covid19.lacounty.gov/dashboards

9. Wallace DW, Burleson SL, Heimann MA, et al. An adapted emergency department triage algorithm for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:1374-1379. doi:10.1002/emp2.12210

10. Montrief T, Ramzy M, Long B, Gottlieb M, Hercz D. COVID-19 respiratory support in the emergency department setting. Am Journal Emerg Med. 2020;38(10):2160-2168. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.001

11. Alqahtani F, Alanazi M, Alassaf W, et al. Preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the emergency department by implementing a separate pathway for patients with respiratory conditions. J Complement Integr Med. 2022;19(2):383-388. doi:10.1515/jcim-2020-0422

12. Odorizzi S, Clark E, Nemnom MJ, et al. Flow impacts of hot/cold zone infection control procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic in the emergency department. CJEM. 2022;24(4):390-396. doi:10.1007/s43678-022-00278-0

13. Wee LE, Fua TP, Chua YY, et al. Containing COVID-19 in the emergency department: the role of improved case detection and segregation of suspect cases. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):379-387. doi:10.1111/acem.13984

14. Tan RMR, Ong GYK, Chong SL, Ganapathy S, Tyebally A, Lee KP. Dynamic adaptation to COVID-19 in a Singapore paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(5):252-254. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-20963

15. Quah LJJ, Tan BKK, Fua TP, et al. Reorganising the emergency department to manage the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12245-020-00294-w

16. Jinadatha C, Jones LD, Choi H, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in inpatient and outpatient settings in a Veterans Affairs health care system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab328. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab328

17. Riediker M, Briceno-Ayala L, Ichihara G, et al. Higher viral load and infectivity increase risk of aerosol transmission for Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152:w30133. doi:10.4414/smw.2022.w30133

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, patient encounters with the health care system plummeted.1-3 The perceived increased risk of contracting COVID-19 while obtaining care was thought to be a contributing factor. In outpatient settings, one study noted a 63% decrease in visits to otolaryngology visits in Massachusetts, and another noted a 33% decrease in dental office visits at the onset of the pandemic in 2020 compared with the same time frame in 2019.2,4 Along with mask mandates and stay-at-home orders, various institutions sought to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 through different protocols, including the use of social distancing, limitation of visitors, and telehealth. Despite some of these measures, nosocomial infections were not uncommon. For example, one hospital in the United Kingdom reported that 15% of COVID-19 inpatient cases in a 6-week period in 2020 were probably or definitely hospital acquired. These patients had a 36% case fatality rate.5

Unlike outpatient treatment centers, however, the emergency department (ED) is mandated by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act to provide a medical screening examination and to stabilize emergency medical conditions to all patients presenting to the ED. Thus, high numbers of undifferentiated and symptomatic patients are forced to congregate in EDs, increasing the risk of transmission of COVID-19. This perception of increased risk led to a 42% decrease in ED visits during March and April 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Correspondingly, there was a 20% decrease in code stroke activations at a hospital in Canada and a 38% decrease in ST-elevation myocardial infarction activations across 9 United States hospital systems.6,7

Limited studies have been conducted to date to determine whether contracting COVID-19 while in the ED is a risk. One retrospective case-control study evaluating 39 EDs in the US showed that ED colocation with known patients with COVID-19 was not associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 transmission.5 However, this study also recognized that infection control strategies widely varied by location and date.

In this study, we report the incidence of COVID-19 infections within 21 days after the initial visit for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection to the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) ED and compared it with that of COVID-19 infections for tests performed within the VAGLAHS.

Program Description

As a quality improvement measure, the

Patients with specific symptoms noted during triage, such as those associated with COVID-19 diagnosis, respiratory infections, fever, and/or myalgias, were isolated in their own patient room. Electronic tablets were used for persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 to communicate with family and/or medical staff who did not need to enter the patient’s room. Two-hour disinfection protocols were instituted for high-risk patients who were moved during the course of their treatment (ie, transfer to another bed for admission or discharge). All staff was specifically trained in personal protective equipment (PPE) donning and doffing, and 2-physician airway teams were implemented to ensure proper PPE use and safe COVID-19 intubations.

COVID-19 Infections

Electronic health records of patients who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not related to COVID-19 were reviewed from

A total of 8708 patients who came to the ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection and had a COVID-19 test within 21 days of the ED visit met the inclusion criteria. The overall average positivity rate at the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection was 1.1% from June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021. The positivity rate by month ranged from 0% to 6.7% for this period (Figure).

Discussion

Implementing COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED helped minimize exposure and subsequent infection of COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection. Contextualizing this with the overall average monthly positivity rate of veterans in the VAGLAHS catchment area (10.9%) or Los Angeles County (7.9%) between June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021, veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection were less likely to test positive for COVID-19 within 21 days (1.1%), suggesting that the extensive measures taken at the VAGLAHS ED were effective.8

Many health care systems in the US and abroad have experimented with different transmission mitigation strategies in the ED. These tactics have included careful resource allocation when PPE shortages occur, incorporation of airway teams with appropriate safety measures to reduce nosocomial spread to health care workers, and use of a cohorting plan to separate persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 from other patients.9-15 Additionally, forward screening areas were incorporated similar to the COVID-19 tent that was instituted at the VAGLAHS ED to manage patients who were referred to the ED for COVID-19 testing during the beginning of the pandemic, which prevented symptomatic patients from congregating with asymptomatic patients.14,15

Encouragingly, some of these studies reported no cases of nosocomial transmission in the ED.11,13 In a separate study, 14 clusters of COVID-19 cases were identified at one VA health care system in which nosocomial transmission was suspected, including one in the ED.16 Using contact tracing, no patients and 9 employees were found to have contracted COVID-19 in that cluster. Overall, among all clusters examined within the health care system, either by contact tracing or by whole-genome sequencing, the authors found that transmission from health care personnel to patients was rare. Despite different methodologies, we also similarly found that ED patients in our VA facility were unlikely to become infected with COVID-19.

While the low incidence of positive COVID-19 tests cannot be attributed to any one method, our data provide a working blueprint for enhanced ED precautions in future surges of COVID-19 or other airborne diseases, including that of future pandemics.

Limitations

Notably, although the VA is the largest health care system in the US, a considerable number of veterans may present to non-VA EDs to seek care, and thus their data are not included here; these veterans may live farther from a VA facility or experience higher barriers to care than veterans who exclusively or almost exclusively seek care within the VA. As a result, we are unable to account for COVID-19 tests completed outside the VA. Moreover, the wild type SARS-CoV-2 virus was dominant during the time frame chosen for this assessment, and data may not be generalizable to other variants (eg, omicron) that are known to be more highly transmissible.17 Lastly, although our observation was performed at a single VA ED and may not apply to other facilities, especially in light of different mitigation strategies, our findings still provide support for approaches to minimizing patient and staff exposure to COVID-19 in ED settings.

Conclusions

Implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED may have minimized exposure to COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 and did not put one at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Taken together, our data suggest that patients should not avoid seeking emergency care out of fear of contracting COVID-19 if EDs have adequately instituted mitigation techniques.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, patient encounters with the health care system plummeted.1-3 The perceived increased risk of contracting COVID-19 while obtaining care was thought to be a contributing factor. In outpatient settings, one study noted a 63% decrease in visits to otolaryngology visits in Massachusetts, and another noted a 33% decrease in dental office visits at the onset of the pandemic in 2020 compared with the same time frame in 2019.2,4 Along with mask mandates and stay-at-home orders, various institutions sought to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 through different protocols, including the use of social distancing, limitation of visitors, and telehealth. Despite some of these measures, nosocomial infections were not uncommon. For example, one hospital in the United Kingdom reported that 15% of COVID-19 inpatient cases in a 6-week period in 2020 were probably or definitely hospital acquired. These patients had a 36% case fatality rate.5

Unlike outpatient treatment centers, however, the emergency department (ED) is mandated by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act to provide a medical screening examination and to stabilize emergency medical conditions to all patients presenting to the ED. Thus, high numbers of undifferentiated and symptomatic patients are forced to congregate in EDs, increasing the risk of transmission of COVID-19. This perception of increased risk led to a 42% decrease in ED visits during March and April 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Correspondingly, there was a 20% decrease in code stroke activations at a hospital in Canada and a 38% decrease in ST-elevation myocardial infarction activations across 9 United States hospital systems.6,7

Limited studies have been conducted to date to determine whether contracting COVID-19 while in the ED is a risk. One retrospective case-control study evaluating 39 EDs in the US showed that ED colocation with known patients with COVID-19 was not associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 transmission.5 However, this study also recognized that infection control strategies widely varied by location and date.

In this study, we report the incidence of COVID-19 infections within 21 days after the initial visit for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection to the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) ED and compared it with that of COVID-19 infections for tests performed within the VAGLAHS.

Program Description

As a quality improvement measure, the

Patients with specific symptoms noted during triage, such as those associated with COVID-19 diagnosis, respiratory infections, fever, and/or myalgias, were isolated in their own patient room. Electronic tablets were used for persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 to communicate with family and/or medical staff who did not need to enter the patient’s room. Two-hour disinfection protocols were instituted for high-risk patients who were moved during the course of their treatment (ie, transfer to another bed for admission or discharge). All staff was specifically trained in personal protective equipment (PPE) donning and doffing, and 2-physician airway teams were implemented to ensure proper PPE use and safe COVID-19 intubations.

COVID-19 Infections

Electronic health records of patients who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not related to COVID-19 were reviewed from

A total of 8708 patients who came to the ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection and had a COVID-19 test within 21 days of the ED visit met the inclusion criteria. The overall average positivity rate at the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection was 1.1% from June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021. The positivity rate by month ranged from 0% to 6.7% for this period (Figure).

Discussion

Implementing COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED helped minimize exposure and subsequent infection of COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED with symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection. Contextualizing this with the overall average monthly positivity rate of veterans in the VAGLAHS catchment area (10.9%) or Los Angeles County (7.9%) between June 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021, veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 infection were less likely to test positive for COVID-19 within 21 days (1.1%), suggesting that the extensive measures taken at the VAGLAHS ED were effective.8

Many health care systems in the US and abroad have experimented with different transmission mitigation strategies in the ED. These tactics have included careful resource allocation when PPE shortages occur, incorporation of airway teams with appropriate safety measures to reduce nosocomial spread to health care workers, and use of a cohorting plan to separate persons under investigation and patients with COVID-19 from other patients.9-15 Additionally, forward screening areas were incorporated similar to the COVID-19 tent that was instituted at the VAGLAHS ED to manage patients who were referred to the ED for COVID-19 testing during the beginning of the pandemic, which prevented symptomatic patients from congregating with asymptomatic patients.14,15

Encouragingly, some of these studies reported no cases of nosocomial transmission in the ED.11,13 In a separate study, 14 clusters of COVID-19 cases were identified at one VA health care system in which nosocomial transmission was suspected, including one in the ED.16 Using contact tracing, no patients and 9 employees were found to have contracted COVID-19 in that cluster. Overall, among all clusters examined within the health care system, either by contact tracing or by whole-genome sequencing, the authors found that transmission from health care personnel to patients was rare. Despite different methodologies, we also similarly found that ED patients in our VA facility were unlikely to become infected with COVID-19.

While the low incidence of positive COVID-19 tests cannot be attributed to any one method, our data provide a working blueprint for enhanced ED precautions in future surges of COVID-19 or other airborne diseases, including that of future pandemics.

Limitations

Notably, although the VA is the largest health care system in the US, a considerable number of veterans may present to non-VA EDs to seek care, and thus their data are not included here; these veterans may live farther from a VA facility or experience higher barriers to care than veterans who exclusively or almost exclusively seek care within the VA. As a result, we are unable to account for COVID-19 tests completed outside the VA. Moreover, the wild type SARS-CoV-2 virus was dominant during the time frame chosen for this assessment, and data may not be generalizable to other variants (eg, omicron) that are known to be more highly transmissible.17 Lastly, although our observation was performed at a single VA ED and may not apply to other facilities, especially in light of different mitigation strategies, our findings still provide support for approaches to minimizing patient and staff exposure to COVID-19 in ED settings.

Conclusions

Implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures in the VAGLAHS ED may have minimized exposure to COVID-19 for veterans who visited the VAGLAHS ED for symptoms not associated with COVID-19 and did not put one at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Taken together, our data suggest that patients should not avoid seeking emergency care out of fear of contracting COVID-19 if EDs have adequately instituted mitigation techniques.

1. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al; National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699-704. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1

2. Fan T, Workman AD, Miller LE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on otolaryngology community practice in Massachusetts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(3):424-430. doi:10.1177/0194599820983732

3. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

4. Kranz AM, Chen A, Gahlon G, Stein BD. 2020 trends in dental office visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(7):535-541,e1. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2021.02.01

5. Ridgway JP, Robicsek AA. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) acquisition among emergency department patients: a retrospective case control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(1):105-107. doi:10.1017/ice.2020.1224

6. Bres Bullrich M, Fridman S, Mandzia JL, et al. COVID-19: stroke admissions, emergency department visits, and prevention clinic referrals. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47(5):693-696. doi:10.1017/cjn.2020.101

7. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871-2872. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011

8. LA County COVID-19 Surveillance Dashboard. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://covid19.lacounty.gov/dashboards

9. Wallace DW, Burleson SL, Heimann MA, et al. An adapted emergency department triage algorithm for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:1374-1379. doi:10.1002/emp2.12210

10. Montrief T, Ramzy M, Long B, Gottlieb M, Hercz D. COVID-19 respiratory support in the emergency department setting. Am Journal Emerg Med. 2020;38(10):2160-2168. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.001

11. Alqahtani F, Alanazi M, Alassaf W, et al. Preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the emergency department by implementing a separate pathway for patients with respiratory conditions. J Complement Integr Med. 2022;19(2):383-388. doi:10.1515/jcim-2020-0422

12. Odorizzi S, Clark E, Nemnom MJ, et al. Flow impacts of hot/cold zone infection control procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic in the emergency department. CJEM. 2022;24(4):390-396. doi:10.1007/s43678-022-00278-0

13. Wee LE, Fua TP, Chua YY, et al. Containing COVID-19 in the emergency department: the role of improved case detection and segregation of suspect cases. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):379-387. doi:10.1111/acem.13984

14. Tan RMR, Ong GYK, Chong SL, Ganapathy S, Tyebally A, Lee KP. Dynamic adaptation to COVID-19 in a Singapore paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(5):252-254. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-20963

15. Quah LJJ, Tan BKK, Fua TP, et al. Reorganising the emergency department to manage the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12245-020-00294-w

16. Jinadatha C, Jones LD, Choi H, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in inpatient and outpatient settings in a Veterans Affairs health care system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab328. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab328

17. Riediker M, Briceno-Ayala L, Ichihara G, et al. Higher viral load and infectivity increase risk of aerosol transmission for Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152:w30133. doi:10.4414/smw.2022.w30133

1. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al; National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699-704. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1

2. Fan T, Workman AD, Miller LE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on otolaryngology community practice in Massachusetts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(3):424-430. doi:10.1177/0194599820983732

3. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

4. Kranz AM, Chen A, Gahlon G, Stein BD. 2020 trends in dental office visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(7):535-541,e1. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2021.02.01

5. Ridgway JP, Robicsek AA. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) acquisition among emergency department patients: a retrospective case control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(1):105-107. doi:10.1017/ice.2020.1224

6. Bres Bullrich M, Fridman S, Mandzia JL, et al. COVID-19: stroke admissions, emergency department visits, and prevention clinic referrals. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47(5):693-696. doi:10.1017/cjn.2020.101

7. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871-2872. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011

8. LA County COVID-19 Surveillance Dashboard. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://covid19.lacounty.gov/dashboards

9. Wallace DW, Burleson SL, Heimann MA, et al. An adapted emergency department triage algorithm for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:1374-1379. doi:10.1002/emp2.12210

10. Montrief T, Ramzy M, Long B, Gottlieb M, Hercz D. COVID-19 respiratory support in the emergency department setting. Am Journal Emerg Med. 2020;38(10):2160-2168. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.08.001

11. Alqahtani F, Alanazi M, Alassaf W, et al. Preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the emergency department by implementing a separate pathway for patients with respiratory conditions. J Complement Integr Med. 2022;19(2):383-388. doi:10.1515/jcim-2020-0422

12. Odorizzi S, Clark E, Nemnom MJ, et al. Flow impacts of hot/cold zone infection control procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic in the emergency department. CJEM. 2022;24(4):390-396. doi:10.1007/s43678-022-00278-0

13. Wee LE, Fua TP, Chua YY, et al. Containing COVID-19 in the emergency department: the role of improved case detection and segregation of suspect cases. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):379-387. doi:10.1111/acem.13984

14. Tan RMR, Ong GYK, Chong SL, Ganapathy S, Tyebally A, Lee KP. Dynamic adaptation to COVID-19 in a Singapore paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(5):252-254. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-20963

15. Quah LJJ, Tan BKK, Fua TP, et al. Reorganising the emergency department to manage the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12245-020-00294-w

16. Jinadatha C, Jones LD, Choi H, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in inpatient and outpatient settings in a Veterans Affairs health care system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab328. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab328

17. Riediker M, Briceno-Ayala L, Ichihara G, et al. Higher viral load and infectivity increase risk of aerosol transmission for Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152:w30133. doi:10.4414/smw.2022.w30133

Dermatology Author Gender Trends During the COVID-19 Pandemic

To the Editor:

Peer-reviewed publications are important determinants for promotions, academic leadership, and grants in dermatology.1 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dermatology research productivity remains an area of investigation. We sought to determine authorship trends for males and females during the pandemic.

A cross-sectional retrospective study of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor and Google Scholar H5-index—was conducted to identify manuscripts with submission date specified prepandemic (May 1, 2019–October 31, 2019) and during the pandemic (May 1, 2020–October 31, 2020). Submission date, first/last author name, sex, and affiliated country were extracted. Single authors were designated as first authors. Gender API (https://gender-api.com/en/) classified gender. A χ2 test (P<.05) compared differences in proportions of female first/last authors from 2019 to 2020.

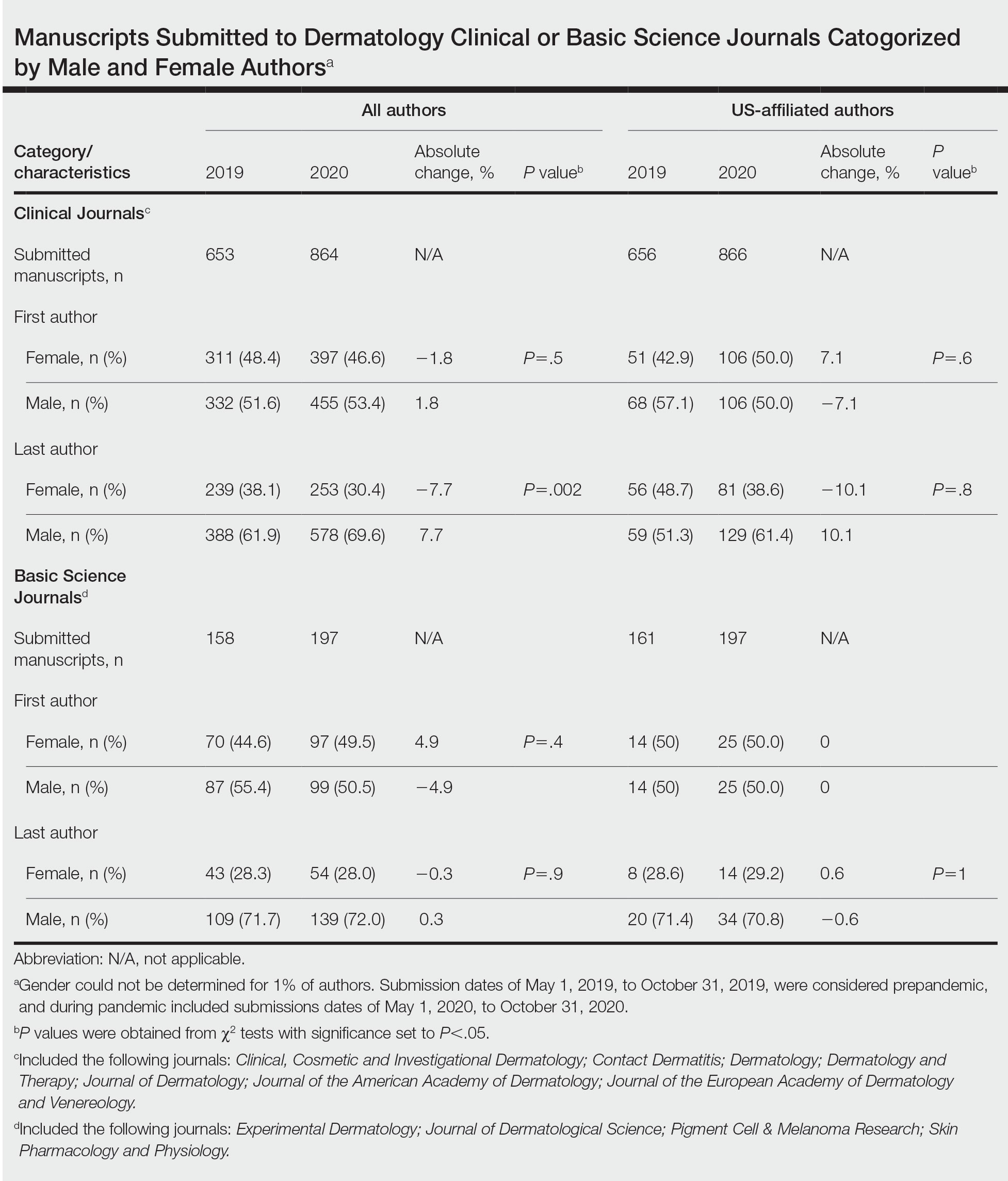

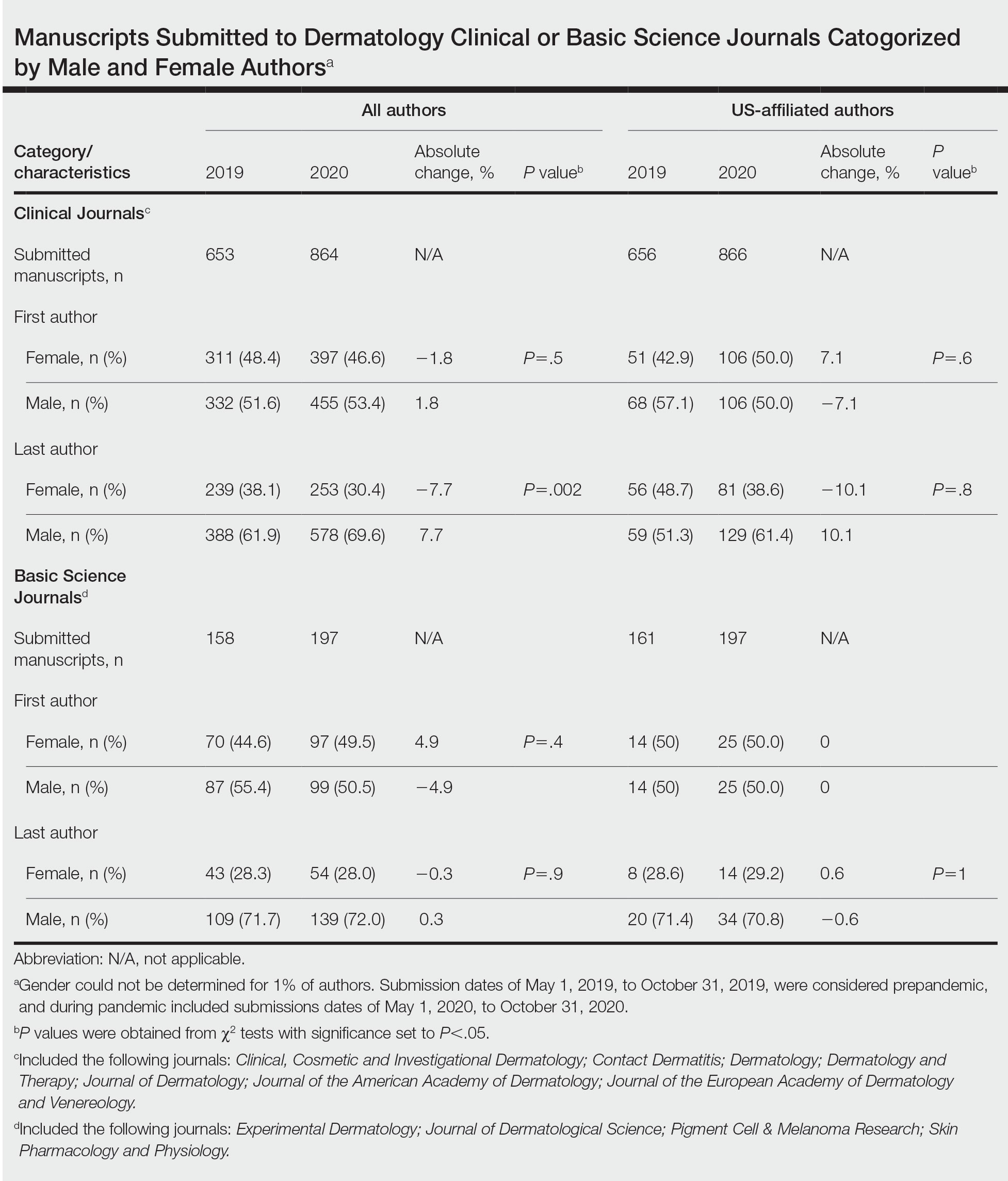

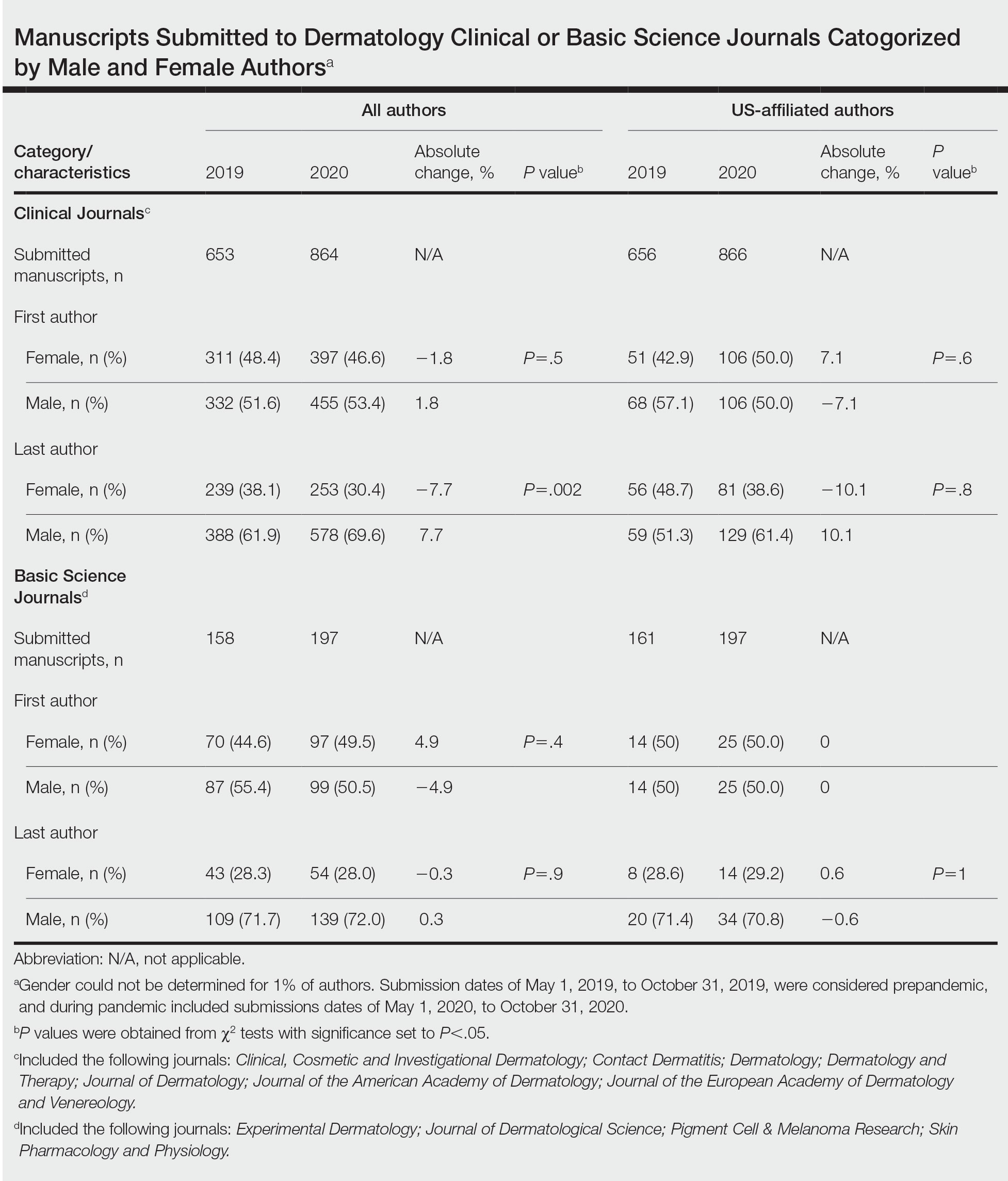

Overall, 811 and 1061 articles submitted in 2019 and 2020, respectively, were included. There were 1517 articles submitted to clinical journals and 355 articles submitted to basic science journals (Table). For the 7 clinical journals included, there was a 7.7% decrease in the proportion of female last authors in 2020 vs 2019 (P=.002), with the largest decrease between August and September 2020. Although other comparisons did not yield statistically significant differences (P>.05 all)(Table), several trends were observed. For clinical journals, there was a 1.8% decrease in the proportion of female first authors. For the 4 basic science journals included, there was a 4.9% increase and a 0.3% decrease in percentages of female first and last authors, respectively, for 2020 vs 2019.

Our findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted female authors’ productivity in clinical dermatology publications. In a survey-based study for 2010 to 2011, female physician-researchers (n=437) spent 8.5 more hours per week on domestic activities and childcare and were more likely to take time off for childcare if their partner worked full time compared with males (n=612)(42.6% vs 12.4%, respectively).2 Our observation that female last authors had a significant decrease in publications may suggest that this population had a disproportionate burden of domestic labor and childcare during the pandemic. It is possible that last authors, who generally are more senior researchers, may be more likely to have childcare, eldercare, and other types of domestic responsibilities. Similarly, in a study of surgery submissions (n=1068), there were 6%, 7%, and 4% decreases in percentages of female last, corresponding, and first authors, respectively, from 2019 to 2020.3Our study had limitations. Only 11 journals were analyzed because others did not have specified submission dates. Some journals only provided submission information for a subset of articles (eg, those published in the In Press section), which may have accounted for the large discrepancy in submission numbers for 2019 to 2020. Gender could not be determined for 1% of authors and was limited to female and male. Although our study submission time frame (May–October 2020) aimed at identifying research conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these studies may have been conducted months or years before the pandemic. Future studies should focus on longer and more comprehensive time frames. Finally, estimated dates of stay-at-home orders fail to consider differences within countries.

The proportion of female US-affiliated first and last authors publishing in dermatology journals increased from 12% to 48% in 1976 and from 6% to 31% in 2006,4 which is encouraging. However, a gender gap persists, with one-third of National Institutes of Health grants in dermatology and one-fourth of research project grants in dermatology awarded to women.5 Consequences of the pandemic on academic productivity may include fewer women represented in higher academic ranks, lower compensation, and lower career satisfaction compared with men.1 We urge academic institutions and funding agencies to recognize and take action to mitigate long-term sequelae. Extended grant end dates and submission periods, funding opportunities dedicated to women, and prioritization of female-authored submissions are some strategies that can safeguard equitable career progression in dermatology research.

- Stewart C, Lipner SR. Gender and race trends in academic rank of dermatologists at top U.S. institutions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:283-285. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2020.04.010

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by highachieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:344-353. doi:10.7326/M13-0974

- Kibbe MR. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:803-804. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3917

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.044

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in national institutes of health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0271

To the Editor:

Peer-reviewed publications are important determinants for promotions, academic leadership, and grants in dermatology.1 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dermatology research productivity remains an area of investigation. We sought to determine authorship trends for males and females during the pandemic.