User login

‘Dealing with a different beast’: Why Delta has doctors worried

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catherine O’Neal, MD, an infectious disease physician, took to the podium of the Louisiana governor’s press conference recently and did not mince words.

“The Delta variant is not last year’s virus, and it’s become incredibly apparent to healthcare workers that we are dealing with a different beast,” she said.

Louisiana is one of the least vaccinated states in the country. In the United States as a whole, 48.6% of the population is fully vaccinated. In Louisiana, it’s just 36%, and Delta is bearing down.

Dr. O’Neal spoke about the pressure that rising COVID cases were already putting on her hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge. She talked about watching her peers, 30- and 40-year-olds, become severely ill with the latest iteration of the new coronavirus — the Delta variant — which is sweeping through the United States with astonishing speed, causing new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths to rise again.

Dr. O’Neal talked about parents who might not be alive to see their children go off to college in a few weeks. She talked about increasing hospital admissions for infected kids and pregnant women on ventilators.

“I want to be clear after seeing what we’ve seen the last two weeks. We only have two choices: We are either going to get vaccinated and end the pandemic, or we’re going to accept death and a lot of it,” Dr. O’Neal said, her voice choked by emotion.

Where Delta goes, death follows

Delta was first identified in India, where it caused a devastating surge in the spring. In a population that was largely unvaccinated, researchers think it may have caused as many as three million deaths. In just a few months’ time, it has sped across the globe.

, which was first identified in the United Kingdom).

Where a single infected person might have spread older versions of the virus to two or three others, mathematician and epidemiologist Adam Kucharski, PhD, an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, thinks that number — called the basic reproduction number — might be around six for Delta, meaning that, on average, each infected person spreads the virus to six others.

“The Delta variant is the most able and fastest and fittest of those viruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, in a recent press briefing.

Early evidence suggests it may also cause more severe disease in people who are not vaccinated.

“There’s clearly increased risk of ICU admission, hospitalization, and death,” said Ashleigh Tuite, PhD, MPH, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

In a study published ahead of peer review, Dr. Tuite and her coauthor, David Fisman, MD, MPH, reviewed the health outcomes for more than 200,000 people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario between February and June of 2021. Starting in February, Ontario began screening all positive COVID tests for mutations in the N501Y region for signs of mutation.

Compared with versions of the coronavirus that circulated in 2020, having an Alpha, Beta, or Gamma variant modestly increased the odds that an infected person would become sicker. The Delta variant raised the risk even higher, more than doubling the odds that an infected person would need to be hospitalized or could die from their infection.

Emerging evidence from England and Scotland, analyzed by Public Health England, also shows an increased risk for hospitalization with Delta. The increases are in line with the Canadian data. Experts caution that the picture may change over time as more evidence is gathered.

“What is causing that? We don’t know,” Dr. Tuite said.

Enhanced virus

The Delta variants (there’s actually more than one in the same viral family) have about 15 different mutations compared with the original virus. Two of these, L452R and E484Q, are mutations to the spike protein that were first flagged as problematic in other variants because they appear to help the virus escape the antibodies we make to fight it.

It has another mutation away from its binding site that’s also getting researchers’ attention — P681R.

This mutation appears to enhance the “springiness” of the parts of the virus that dock onto our cells, said Alexander Greninger, MD, PhD, assistant director of the UW Medicine Clinical Virology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. So it’s more likely to be in the right position to infect our cells if we come into contact with it.

Another theory is that P681R may also enhance the virus’s ability to fuse cells together into clumps that have several different nuclei. These balls of fused cells are called syncytia.

“So it turns into a big factory for making viruses,” said Kamran Kadkhoda, PhD, medical director of immunopathology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This capability is not unique to Delta or even to the new coronavirus. Earlier versions and other viruses can do the same thing, but according to a recent paper in Nature, the syncytia that Delta creates are larger than the ones created by previous variants.

Scientists aren’t sure what these supersized syncytia mean, exactly, but they have some theories. They may help the virus copy itself more quickly, so a person’s viral load builds up quickly. That may enhance the ability of the virus to transmit from person to person.

And at least one recent study from China supports this idea. That study, which was posted ahead of peer review on the website Virological.org, tracked 167 people infected with Delta back to a single index case.

China has used extensive contact tracing to identify people that may have been exposed to the virus and sequester them quickly to tamp down its spread. Once a person is isolated or quarantined, they are tested daily with gold-standard PCR testing to determine whether or not they were infected.

Researchers compared the characteristics of Delta cases with those of people infected in 2020 with previous versions of the virus.

This study found that people infected by Delta tested positive more quickly than their predecessors did. In 2020, it took an average of 6 days for someone to test positive after an exposure. With Delta, it took an average of about 4 days.

When people tested positive, they had more than 1,000 times more virus in their bodies, suggesting that the Delta variant has a higher growth rate in the body.

This gives Delta a big advantage. According to Angie Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, who posted a thread about the study on Twitter, if people are shedding 1,000 times more virus, it is much more likely that close contacts will be exposed to enough of it to become infected themselves.

And if they’re shedding earlier in the course of their infections, the virus has more opportunity to spread.

This may help explain why Delta is so much more contagious.

Beyond transmission, Delta’s ability to form syncytia may have two other important consequences. It may help the virus hide from our immune system, and it may make the virus more damaging to the body.

Commonly, when a virus infects a cell, it will corrupt the cell’s protein-making machinery to crank out more copies of itself. When the cell dies, these new copies are released into the plasma outside the cell where they can float over and infect new cells. It’s in this extracellular space where a virus can also be attacked by the neutralizing antibodies our immune system makes to fight it off.

“Antibodies don’t penetrate inside the cell. If these viruses are going from one cell to another by just fusing to each other, antibodies become less useful,” Dr. Kadkhoda said.

Escape artist

Recent studies show that Delta is also able to escape antibodies made in response to vaccination more effectively than the Alpha, or B.1.1.7 strain. The effect was more pronounced in older adults, who tend to have weaker responses to vaccines in general.

This evasion of the immune system is particularly problematic for people who are only partially vaccinated. Data from the United Kingdom show that a single dose of vaccine is only about 31% effective at preventing illness with Delta, and 75% effective at preventing hospitalization.

After two doses, the vaccines are still highly effective — even against Delta — reaching 80% protection for illness, and 94% for hospitalization, which is why U.S. officials are begging people to get both doses of their shots, and do it as quickly as possible.

Finally, the virus’s ability to form syncytia may leave greater damage behind in the body’s tissues and organs.

“Especially in the lungs,” Dr. Kadkhoda said. The lungs are very fragile tissues. Their tiny air sacs — the alveoli — are only a single-cell thick. They have to be very thin to exchange oxygen in the blood.

“Any damage like that can severely affect any oxygen exchange and the normal housekeeping activities of that tissue,” he said. “In those vital organs, it may be very problematic.”

The research is still early, but studies in animals and cell lines are backing up what doctors say they are seeing in hospitalized patients.

A recent preprint study from researchers in Japan found that hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight — a proxy for how sick they were — compared with hamsters infected with an older version of the virus. The researchers attribute this to the viruses› ability to fuse cells together to form syncytia.

Another investigation, from researchers in India, infected two groups of hamsters — one with the original “wild type” strain of the virus, the other with the Delta variant of the new coronavirus.

As in the Japanese study, the hamsters infected with Delta lost more weight. When the researchers performed necropsies on the animals, they found more lung damage and bleeding in hamsters infected with Delta. This study was also posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

German researchers working with pseudotyped versions of the new coronavirus — viruses that have been genetically changed to make them safer to work with — watched what happened after they used these pseudoviruses to infect lung, colon, and kidney cells in the lab.

They, too, found that cells infected with the Delta variant formed more and larger syncytia compared with cells infected with the wild type strain of the virus. The authors write that their findings suggest Delta could “cause more tissue damage, and thus be more pathogenic, than previous variants.”Researchers say it’s important to remember that, while interesting, this research isn’t conclusive. Hamsters and cells aren’t humans. More studies are needed to prove these theories.

Scientists say that what we already know about Delta makes vaccination more important than ever.

“The net effect is really that, you know, this is worrisome in people who are unvaccinated and then people who have breakthrough infections, but it’s not…a reason to panic or to throw up our hands and say you know, this pandemic is never going to end,” Dr. Tuite said, “[b]ecause what we do see is that the vaccines continue to be highly protective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy still weighs heavy for some rheumatic disease patients

With 49% of the U.S. population fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, a new study highlights the degree of vaccine hesitancy among patients with rheumatic disease to get the vaccine.

The international study, published in May 2021 in Rheumatology, suggests that, of 1,258 patients surveyed worldwide, approximately 40% of patients said they would decline the vaccine.

“Sometimes it’s helpful to talk through their concerns,” said Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH, a University of Alabama at Birmingham rheumatologist who leads the American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 vaccine task force. Dr. Curtis recently reviewed the current literature on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

COVID-19 vaccinations for patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIIRD) is not straightforward. The immune response can be blunted by existing treatments and disease flares can occur.

The latest version of COVID-19 vaccination guidance for patients with RMDs from the ACR addresses vaccine use and implementation strategies. The guidance was issued as conditional or provisional because of the lack of evidence. Its principals are largely based on accepted practice for other vaccines. The guidance is routinely updated as new evidence becomes available. In his presentation at GRAPPA, Dr. Curtis reviewed the latest version of the guidance, which he emphasized is a guidance only and not meant to replace clinical judgment or shared decision-making with patients.

“This is a platform for you to start from as you are thinking about and discussing with your patient what might be best for him or her,” he said.

Concerns about impact of disease activity, treatments on effectiveness

Dr. Curtis highlighted some controversial aspects of COVID-19 vaccines, including heterogeneity of rheumatic diseases and treatment. Patients with AIIRD, including psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritis, RA, and lupus, are at higher risk for hospitalized COVID-19 and worse outcomes, and as such, they are prioritized for vaccination by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, for AIIRD patients, the immune response to COVID-19 vaccination can be “blunted,” according to one study. This may be because of glucocorticoid use or high disease activity. Immunomodulatory therapies, such as methotrexate, rituximab, and abatacept, are known to diminish vaccine response in general. The evidence is less clear for tumor necrosis factor and Janus kinase inhibitors, but they are thought to have the same impact on vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Curtis said. But in these cases, if the effect of a COVID-19 vaccine drops from 90% to 70%, the benefits of vaccination still far outweighs the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“Although we don’t have strong data with clinical outcomes for autoimmune disease or inflammatory disease patients, I’ll run a hypothetical and say: ‘Look, if this vaccine starts 90%-95% effective, even if it’s only 70% effective in somebody with lupus or vasculitis or someone who is taking a higher dose of steroids, I’ll take 70% over nothing if you chose to be vaccinated,’ ” he said.

The benefit of vaccination also outweighs the potential risk of disease flare, he said. The risk is real, but to date, no studies have pointed to a significant risk of disease flare or worsening. However, there have been reported cases of myocardial infarction.

Autoimmune manifestations after vaccination vs. after infection

Researchers writing in the June 29, 2021, issue of JAMA Cardiology described case reports of acute myocarditis in 23 people who received the BNT162b2-mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech) or mRNA-1273 (Moderna) messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines. Plus, there been subsequent reports of myocarditis in other patients, wrote David K. Shay, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Shay is a member of the CDC COVID-19 Response Team.

“What do we know about this possible association between myocarditis and immunization with mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, and what remains unclear? Acute onset of chest pain 3-5 days after vaccine administration, usually after a second dose, is a typical feature of reported cases and suggests an immune-mediated mechanism,” he said.

The cases of myocarditis are concerning, Dr. Curtis said, but the risk is very low with relatively few cases reported among 161 million fully vaccinated people in the United States.

“Certainly, we’re not seeking to minimize that, but the risk of getting COVID and some of the downstream sequelae (autoimmune manifestations) almost certainly outweigh the risks for some of the autoimmune manifestations or worsening [condition],” he said.

A nationwide cohort study from Denmark of 58,052 patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease published in December 2020 in Rheumatology, found that patients with COVID-19 who had an inflammatory rheumatic disease were more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with COVID-19 patients without rheumatic disease. Patients with rheumatic disease had a higher risk of a severe COVID-19 outcome, but it was not a statistically significant difference, said Dr. Curtis, adding that the individual factors such as age and treatment currently received largely determines the risk. The strongest associations between hospitalization for COVID-19 and rheumatic disease were found among patients with RA, vasculitis, and connective tissue disease. Dr. Curtis noted that his own new study results show that risk of death from a COVID-19 infection is higher for patients who have RA or psoriatic arthritis.

There have been published case reports of patients who have developed new-onset lupus, vasculitis, Kawasaki disease, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune cytopenias, and other manifestations after a COVID-19 infection. “These authors suggest that perhaps there is a transient influence on the immune system that leads to a loss of self-tolerance to antigens,” Dr. Curtis said. “Some patients may have an underlying predisposition to autoimmunity in which infections just unmask as we sometimes see with other infections – chronic hepatitis for example.”

Antibody tests not recommended

In its COVID-19 guidance, the ACR, like the Food and Drug Administration, recommends health care providers not to routinely order antibody tests for IgM or IgG to assess immunity after a person has been vaccinated or to assess the need for vaccination in an unvaccinated person. More research is needed to determine if antibodies provide protection, and if so, for how long and how much. Plus, the antibody testing process is not clear cut, so ordering the wrong test is possible, Dr. Curtis said. The tests should clearly differentiate between spike proteins or nucleocapsid proteins.

“The bottom line is that you might be ordering the wrong lab test. Even if you’re ordering the right lab test, I would assert that you probably don’t know what to do with the result. I would then ask you, ‘Does it mean they are protected? Does it mean they are not protected? What are you going to do with the results?’ ” he asked.

Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, a specialist in infectious diseases at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said that, at this point, it’s too early to know what antibody tests mean. “I think it is tempting to test some people, especially patients on B-cell depletion therapy and those on mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Outside of those two types of [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] users, I wouldn’t be tempted to test. We don’t know how well protected they are, but we assume they are protected to some extent,” he said. “They’re probably partially protected and as such, they should take the same precautions they were taking a year ago: masking and avoidance. I think that’s just how it’s going to be for those folks for another year until we get this thing sorted out.”

Modifications to existing rheumatic disease therapies

In its COVID-19 vaccine guidance, the ACR issued recommendations for some common rheumatic disease therapeutics before and/or after the COVID-19 vaccine is administered. The modifications are limited to MMF, methotrexate, JAK inhibitors, subcutaneous abatacept, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs. The recommendations include: hold mycophenolate for 1 week after vaccination if disease is stable; for patients with well-controlled disease, hold methotrexate for 1 week after each of the two mRNA vaccine doses; for patients with well-controlled disease receiving the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, hold methotrexate for 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine; hold JAK inhibitors for 1 week after each dose; for abatacept subcutaneous, hold treatment for 1 week before and after the first dose; and in patients with stable disease, hold acetaminophen and NSAIDs for 24 hours before vaccination, because taking either before vaccination could blunt the vaccine response, Dr. Curtis said.

Holding medication, such as methotrexate, could risk having a flare-up of disease. One study showed the rate of disease flare-up because of withholding standard treatment may be up to 11%, compared with 5.1% in patients who did not hold treatment, he said.

“The point is, if you hold some of these therapies, whether methotrexate or tofacitinib, arthritis will get a little bit worse,” Dr. Curtis said.

A study published on the preprint server medRxiv found that immunosuppressive therapies blunted the response of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, most significantly with glucocorticoids and B-cell therapies.

“That’s what’s led to a lot of the guidance statements about holding treatments for a week or 2 for rituximab. If you’re giving it at 6-month intervals, you want to schedule the vaccine dose or series at about month 5, or a month before the next cycle,” he said.

Talking with patients about COVID-19 vaccination

In talking with patients about vaccine safety, Dr. Curtis recommends addressing a few common misperceptions. First, COVID-19 viruses were not created with a live-attenuated virus (which would be contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients). “You can put patients’ mind at ease that none of the vaccine candidates or platforms – even those that say viral vector – put patients at risk for contracting the infection. These are nonreplicating. So, it’s like you extracted the engine that would allow this virus to replicate,” he said.

Of three COVID-19 vaccinations available in the United States, is one better than the other? The ACR COVID-19 vaccine task force did not reach a consensus on safety profiles of the vaccines because, without head-to-head comparisons, it’s impossible to know, he said.

In talking with patients, review the protocol for continuing with prescribed treatment modalities before the patient receives a COVID-19 vaccine. Safety concerns and concerns about the possibility of having a disease flare-up should be addressed, he said.

With 49% of the U.S. population fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, a new study highlights the degree of vaccine hesitancy among patients with rheumatic disease to get the vaccine.

The international study, published in May 2021 in Rheumatology, suggests that, of 1,258 patients surveyed worldwide, approximately 40% of patients said they would decline the vaccine.

“Sometimes it’s helpful to talk through their concerns,” said Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH, a University of Alabama at Birmingham rheumatologist who leads the American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 vaccine task force. Dr. Curtis recently reviewed the current literature on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

COVID-19 vaccinations for patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIIRD) is not straightforward. The immune response can be blunted by existing treatments and disease flares can occur.

The latest version of COVID-19 vaccination guidance for patients with RMDs from the ACR addresses vaccine use and implementation strategies. The guidance was issued as conditional or provisional because of the lack of evidence. Its principals are largely based on accepted practice for other vaccines. The guidance is routinely updated as new evidence becomes available. In his presentation at GRAPPA, Dr. Curtis reviewed the latest version of the guidance, which he emphasized is a guidance only and not meant to replace clinical judgment or shared decision-making with patients.

“This is a platform for you to start from as you are thinking about and discussing with your patient what might be best for him or her,” he said.

Concerns about impact of disease activity, treatments on effectiveness

Dr. Curtis highlighted some controversial aspects of COVID-19 vaccines, including heterogeneity of rheumatic diseases and treatment. Patients with AIIRD, including psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritis, RA, and lupus, are at higher risk for hospitalized COVID-19 and worse outcomes, and as such, they are prioritized for vaccination by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, for AIIRD patients, the immune response to COVID-19 vaccination can be “blunted,” according to one study. This may be because of glucocorticoid use or high disease activity. Immunomodulatory therapies, such as methotrexate, rituximab, and abatacept, are known to diminish vaccine response in general. The evidence is less clear for tumor necrosis factor and Janus kinase inhibitors, but they are thought to have the same impact on vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Curtis said. But in these cases, if the effect of a COVID-19 vaccine drops from 90% to 70%, the benefits of vaccination still far outweighs the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“Although we don’t have strong data with clinical outcomes for autoimmune disease or inflammatory disease patients, I’ll run a hypothetical and say: ‘Look, if this vaccine starts 90%-95% effective, even if it’s only 70% effective in somebody with lupus or vasculitis or someone who is taking a higher dose of steroids, I’ll take 70% over nothing if you chose to be vaccinated,’ ” he said.

The benefit of vaccination also outweighs the potential risk of disease flare, he said. The risk is real, but to date, no studies have pointed to a significant risk of disease flare or worsening. However, there have been reported cases of myocardial infarction.

Autoimmune manifestations after vaccination vs. after infection

Researchers writing in the June 29, 2021, issue of JAMA Cardiology described case reports of acute myocarditis in 23 people who received the BNT162b2-mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech) or mRNA-1273 (Moderna) messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines. Plus, there been subsequent reports of myocarditis in other patients, wrote David K. Shay, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Shay is a member of the CDC COVID-19 Response Team.

“What do we know about this possible association between myocarditis and immunization with mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, and what remains unclear? Acute onset of chest pain 3-5 days after vaccine administration, usually after a second dose, is a typical feature of reported cases and suggests an immune-mediated mechanism,” he said.

The cases of myocarditis are concerning, Dr. Curtis said, but the risk is very low with relatively few cases reported among 161 million fully vaccinated people in the United States.

“Certainly, we’re not seeking to minimize that, but the risk of getting COVID and some of the downstream sequelae (autoimmune manifestations) almost certainly outweigh the risks for some of the autoimmune manifestations or worsening [condition],” he said.

A nationwide cohort study from Denmark of 58,052 patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease published in December 2020 in Rheumatology, found that patients with COVID-19 who had an inflammatory rheumatic disease were more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with COVID-19 patients without rheumatic disease. Patients with rheumatic disease had a higher risk of a severe COVID-19 outcome, but it was not a statistically significant difference, said Dr. Curtis, adding that the individual factors such as age and treatment currently received largely determines the risk. The strongest associations between hospitalization for COVID-19 and rheumatic disease were found among patients with RA, vasculitis, and connective tissue disease. Dr. Curtis noted that his own new study results show that risk of death from a COVID-19 infection is higher for patients who have RA or psoriatic arthritis.

There have been published case reports of patients who have developed new-onset lupus, vasculitis, Kawasaki disease, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune cytopenias, and other manifestations after a COVID-19 infection. “These authors suggest that perhaps there is a transient influence on the immune system that leads to a loss of self-tolerance to antigens,” Dr. Curtis said. “Some patients may have an underlying predisposition to autoimmunity in which infections just unmask as we sometimes see with other infections – chronic hepatitis for example.”

Antibody tests not recommended

In its COVID-19 guidance, the ACR, like the Food and Drug Administration, recommends health care providers not to routinely order antibody tests for IgM or IgG to assess immunity after a person has been vaccinated or to assess the need for vaccination in an unvaccinated person. More research is needed to determine if antibodies provide protection, and if so, for how long and how much. Plus, the antibody testing process is not clear cut, so ordering the wrong test is possible, Dr. Curtis said. The tests should clearly differentiate between spike proteins or nucleocapsid proteins.

“The bottom line is that you might be ordering the wrong lab test. Even if you’re ordering the right lab test, I would assert that you probably don’t know what to do with the result. I would then ask you, ‘Does it mean they are protected? Does it mean they are not protected? What are you going to do with the results?’ ” he asked.

Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, a specialist in infectious diseases at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said that, at this point, it’s too early to know what antibody tests mean. “I think it is tempting to test some people, especially patients on B-cell depletion therapy and those on mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Outside of those two types of [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] users, I wouldn’t be tempted to test. We don’t know how well protected they are, but we assume they are protected to some extent,” he said. “They’re probably partially protected and as such, they should take the same precautions they were taking a year ago: masking and avoidance. I think that’s just how it’s going to be for those folks for another year until we get this thing sorted out.”

Modifications to existing rheumatic disease therapies

In its COVID-19 vaccine guidance, the ACR issued recommendations for some common rheumatic disease therapeutics before and/or after the COVID-19 vaccine is administered. The modifications are limited to MMF, methotrexate, JAK inhibitors, subcutaneous abatacept, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs. The recommendations include: hold mycophenolate for 1 week after vaccination if disease is stable; for patients with well-controlled disease, hold methotrexate for 1 week after each of the two mRNA vaccine doses; for patients with well-controlled disease receiving the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, hold methotrexate for 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine; hold JAK inhibitors for 1 week after each dose; for abatacept subcutaneous, hold treatment for 1 week before and after the first dose; and in patients with stable disease, hold acetaminophen and NSAIDs for 24 hours before vaccination, because taking either before vaccination could blunt the vaccine response, Dr. Curtis said.

Holding medication, such as methotrexate, could risk having a flare-up of disease. One study showed the rate of disease flare-up because of withholding standard treatment may be up to 11%, compared with 5.1% in patients who did not hold treatment, he said.

“The point is, if you hold some of these therapies, whether methotrexate or tofacitinib, arthritis will get a little bit worse,” Dr. Curtis said.

A study published on the preprint server medRxiv found that immunosuppressive therapies blunted the response of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, most significantly with glucocorticoids and B-cell therapies.

“That’s what’s led to a lot of the guidance statements about holding treatments for a week or 2 for rituximab. If you’re giving it at 6-month intervals, you want to schedule the vaccine dose or series at about month 5, or a month before the next cycle,” he said.

Talking with patients about COVID-19 vaccination

In talking with patients about vaccine safety, Dr. Curtis recommends addressing a few common misperceptions. First, COVID-19 viruses were not created with a live-attenuated virus (which would be contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients). “You can put patients’ mind at ease that none of the vaccine candidates or platforms – even those that say viral vector – put patients at risk for contracting the infection. These are nonreplicating. So, it’s like you extracted the engine that would allow this virus to replicate,” he said.

Of three COVID-19 vaccinations available in the United States, is one better than the other? The ACR COVID-19 vaccine task force did not reach a consensus on safety profiles of the vaccines because, without head-to-head comparisons, it’s impossible to know, he said.

In talking with patients, review the protocol for continuing with prescribed treatment modalities before the patient receives a COVID-19 vaccine. Safety concerns and concerns about the possibility of having a disease flare-up should be addressed, he said.

With 49% of the U.S. population fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, a new study highlights the degree of vaccine hesitancy among patients with rheumatic disease to get the vaccine.

The international study, published in May 2021 in Rheumatology, suggests that, of 1,258 patients surveyed worldwide, approximately 40% of patients said they would decline the vaccine.

“Sometimes it’s helpful to talk through their concerns,” said Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH, a University of Alabama at Birmingham rheumatologist who leads the American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 vaccine task force. Dr. Curtis recently reviewed the current literature on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

COVID-19 vaccinations for patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIIRD) is not straightforward. The immune response can be blunted by existing treatments and disease flares can occur.

The latest version of COVID-19 vaccination guidance for patients with RMDs from the ACR addresses vaccine use and implementation strategies. The guidance was issued as conditional or provisional because of the lack of evidence. Its principals are largely based on accepted practice for other vaccines. The guidance is routinely updated as new evidence becomes available. In his presentation at GRAPPA, Dr. Curtis reviewed the latest version of the guidance, which he emphasized is a guidance only and not meant to replace clinical judgment or shared decision-making with patients.

“This is a platform for you to start from as you are thinking about and discussing with your patient what might be best for him or her,” he said.

Concerns about impact of disease activity, treatments on effectiveness

Dr. Curtis highlighted some controversial aspects of COVID-19 vaccines, including heterogeneity of rheumatic diseases and treatment. Patients with AIIRD, including psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritis, RA, and lupus, are at higher risk for hospitalized COVID-19 and worse outcomes, and as such, they are prioritized for vaccination by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, for AIIRD patients, the immune response to COVID-19 vaccination can be “blunted,” according to one study. This may be because of glucocorticoid use or high disease activity. Immunomodulatory therapies, such as methotrexate, rituximab, and abatacept, are known to diminish vaccine response in general. The evidence is less clear for tumor necrosis factor and Janus kinase inhibitors, but they are thought to have the same impact on vaccine effectiveness, Dr. Curtis said. But in these cases, if the effect of a COVID-19 vaccine drops from 90% to 70%, the benefits of vaccination still far outweighs the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“Although we don’t have strong data with clinical outcomes for autoimmune disease or inflammatory disease patients, I’ll run a hypothetical and say: ‘Look, if this vaccine starts 90%-95% effective, even if it’s only 70% effective in somebody with lupus or vasculitis or someone who is taking a higher dose of steroids, I’ll take 70% over nothing if you chose to be vaccinated,’ ” he said.

The benefit of vaccination also outweighs the potential risk of disease flare, he said. The risk is real, but to date, no studies have pointed to a significant risk of disease flare or worsening. However, there have been reported cases of myocardial infarction.

Autoimmune manifestations after vaccination vs. after infection

Researchers writing in the June 29, 2021, issue of JAMA Cardiology described case reports of acute myocarditis in 23 people who received the BNT162b2-mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech) or mRNA-1273 (Moderna) messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines. Plus, there been subsequent reports of myocarditis in other patients, wrote David K. Shay, MD, MPH, in an accompanying editorial. Dr. Shay is a member of the CDC COVID-19 Response Team.

“What do we know about this possible association between myocarditis and immunization with mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, and what remains unclear? Acute onset of chest pain 3-5 days after vaccine administration, usually after a second dose, is a typical feature of reported cases and suggests an immune-mediated mechanism,” he said.

The cases of myocarditis are concerning, Dr. Curtis said, but the risk is very low with relatively few cases reported among 161 million fully vaccinated people in the United States.

“Certainly, we’re not seeking to minimize that, but the risk of getting COVID and some of the downstream sequelae (autoimmune manifestations) almost certainly outweigh the risks for some of the autoimmune manifestations or worsening [condition],” he said.

A nationwide cohort study from Denmark of 58,052 patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease published in December 2020 in Rheumatology, found that patients with COVID-19 who had an inflammatory rheumatic disease were more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with COVID-19 patients without rheumatic disease. Patients with rheumatic disease had a higher risk of a severe COVID-19 outcome, but it was not a statistically significant difference, said Dr. Curtis, adding that the individual factors such as age and treatment currently received largely determines the risk. The strongest associations between hospitalization for COVID-19 and rheumatic disease were found among patients with RA, vasculitis, and connective tissue disease. Dr. Curtis noted that his own new study results show that risk of death from a COVID-19 infection is higher for patients who have RA or psoriatic arthritis.

There have been published case reports of patients who have developed new-onset lupus, vasculitis, Kawasaki disease, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune cytopenias, and other manifestations after a COVID-19 infection. “These authors suggest that perhaps there is a transient influence on the immune system that leads to a loss of self-tolerance to antigens,” Dr. Curtis said. “Some patients may have an underlying predisposition to autoimmunity in which infections just unmask as we sometimes see with other infections – chronic hepatitis for example.”

Antibody tests not recommended

In its COVID-19 guidance, the ACR, like the Food and Drug Administration, recommends health care providers not to routinely order antibody tests for IgM or IgG to assess immunity after a person has been vaccinated or to assess the need for vaccination in an unvaccinated person. More research is needed to determine if antibodies provide protection, and if so, for how long and how much. Plus, the antibody testing process is not clear cut, so ordering the wrong test is possible, Dr. Curtis said. The tests should clearly differentiate between spike proteins or nucleocapsid proteins.

“The bottom line is that you might be ordering the wrong lab test. Even if you’re ordering the right lab test, I would assert that you probably don’t know what to do with the result. I would then ask you, ‘Does it mean they are protected? Does it mean they are not protected? What are you going to do with the results?’ ” he asked.

Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, a specialist in infectious diseases at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said that, at this point, it’s too early to know what antibody tests mean. “I think it is tempting to test some people, especially patients on B-cell depletion therapy and those on mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Outside of those two types of [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] users, I wouldn’t be tempted to test. We don’t know how well protected they are, but we assume they are protected to some extent,” he said. “They’re probably partially protected and as such, they should take the same precautions they were taking a year ago: masking and avoidance. I think that’s just how it’s going to be for those folks for another year until we get this thing sorted out.”

Modifications to existing rheumatic disease therapies

In its COVID-19 vaccine guidance, the ACR issued recommendations for some common rheumatic disease therapeutics before and/or after the COVID-19 vaccine is administered. The modifications are limited to MMF, methotrexate, JAK inhibitors, subcutaneous abatacept, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs. The recommendations include: hold mycophenolate for 1 week after vaccination if disease is stable; for patients with well-controlled disease, hold methotrexate for 1 week after each of the two mRNA vaccine doses; for patients with well-controlled disease receiving the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, hold methotrexate for 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine; hold JAK inhibitors for 1 week after each dose; for abatacept subcutaneous, hold treatment for 1 week before and after the first dose; and in patients with stable disease, hold acetaminophen and NSAIDs for 24 hours before vaccination, because taking either before vaccination could blunt the vaccine response, Dr. Curtis said.

Holding medication, such as methotrexate, could risk having a flare-up of disease. One study showed the rate of disease flare-up because of withholding standard treatment may be up to 11%, compared with 5.1% in patients who did not hold treatment, he said.

“The point is, if you hold some of these therapies, whether methotrexate or tofacitinib, arthritis will get a little bit worse,” Dr. Curtis said.

A study published on the preprint server medRxiv found that immunosuppressive therapies blunted the response of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, most significantly with glucocorticoids and B-cell therapies.

“That’s what’s led to a lot of the guidance statements about holding treatments for a week or 2 for rituximab. If you’re giving it at 6-month intervals, you want to schedule the vaccine dose or series at about month 5, or a month before the next cycle,” he said.

Talking with patients about COVID-19 vaccination

In talking with patients about vaccine safety, Dr. Curtis recommends addressing a few common misperceptions. First, COVID-19 viruses were not created with a live-attenuated virus (which would be contraindicated for immunosuppressed patients). “You can put patients’ mind at ease that none of the vaccine candidates or platforms – even those that say viral vector – put patients at risk for contracting the infection. These are nonreplicating. So, it’s like you extracted the engine that would allow this virus to replicate,” he said.

Of three COVID-19 vaccinations available in the United States, is one better than the other? The ACR COVID-19 vaccine task force did not reach a consensus on safety profiles of the vaccines because, without head-to-head comparisons, it’s impossible to know, he said.

In talking with patients, review the protocol for continuing with prescribed treatment modalities before the patient receives a COVID-19 vaccine. Safety concerns and concerns about the possibility of having a disease flare-up should be addressed, he said.

FROM THE GRAPPA 2021 ANNUAL MEETING

Children and COVID: New vaccinations increase as cases continue to climb

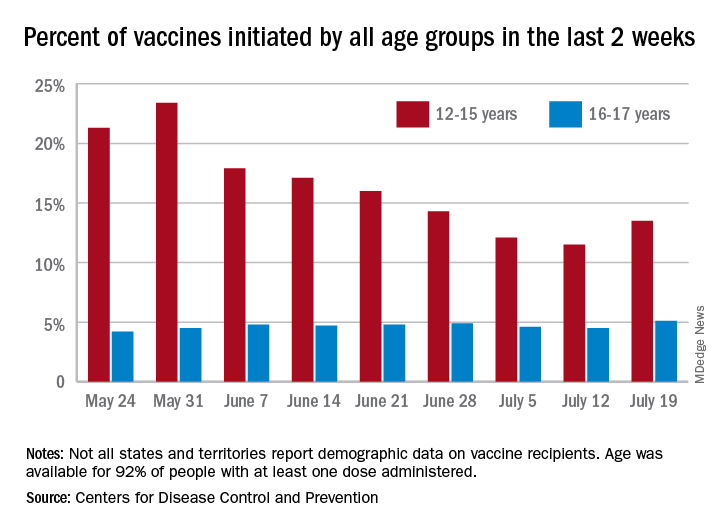

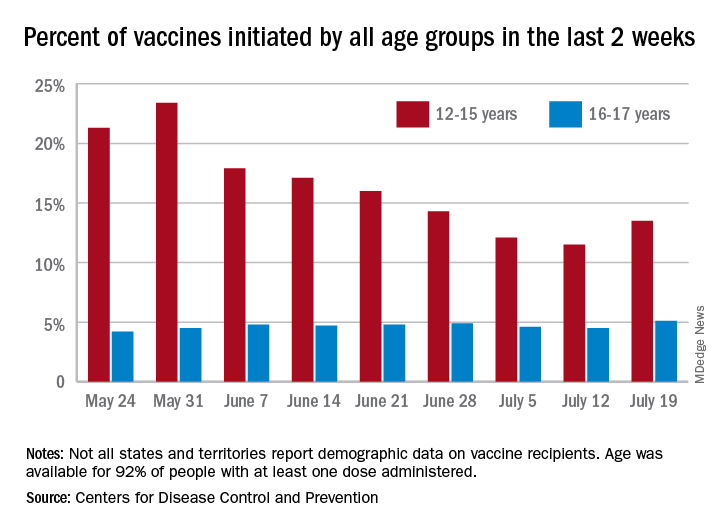

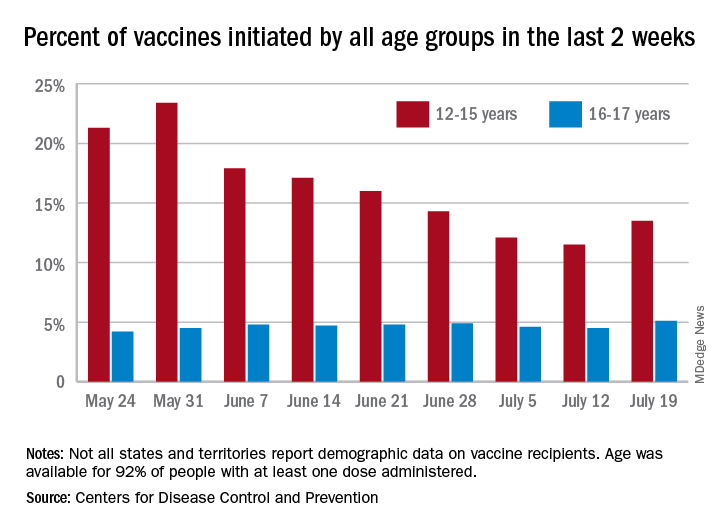

Children aged 12-15 years represented 13.5% of all first vaccinations received during the 2 weeks ending July 19, compared with 11.5% for the 2 weeks ending July 12, marking the first increase since the end of May. First vaccinations in 16- and 17-year-olds, who make up a much smaller share of the U.S. population, also went up, topping 5%, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker.

The total number of vaccine initiations was almost 250,000 for the week ending July 19, after dropping to a low of 201,000 the previous week. Before that, first vaccinations had fallen in 5 of the previous 6 weeks, going from 1.4 million on May 24 to 307,000 on July 5, the CDC said.

New cases of COVID-19, unfortunately, continued to follow the trend among the larger population: As of July 15, weekly cases in children were up by 179% since dropping to 8,400 on June 24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in a joint report. The 23,551 new cases in children for the week ending July 15 were 15.9% of all cases reported.

With those new cases, the total number of children infected with COVID-19 comes to almost 4.1 million since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said. The CDC data indicate that just over 5.35 million children aged 12-15 years and 3.53 million 16- and 17-year-olds have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 6.8 million children aged 12-17 are fully vaccinated.

Fully vaccinated children represent 26.4% of all 12- to 15-year-olds and 38.3% of the 16- 17-year-olds as of July 19. The corresponding numbers for those who have received at least one dose are 35.2% (ages 12-15) and 46.8% (16-17), the CDC said.

The AAP recently recommended in-person learning with universal masking in schools this fall “because a significant portion of the student population is not yet eligible for vaccines. ... Many schools will not have a system to monitor vaccine status of students, teachers and staff, and some communities overall have low vaccination uptake where the virus may be circulating more prominently.”

Children aged 12-15 years represented 13.5% of all first vaccinations received during the 2 weeks ending July 19, compared with 11.5% for the 2 weeks ending July 12, marking the first increase since the end of May. First vaccinations in 16- and 17-year-olds, who make up a much smaller share of the U.S. population, also went up, topping 5%, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker.

The total number of vaccine initiations was almost 250,000 for the week ending July 19, after dropping to a low of 201,000 the previous week. Before that, first vaccinations had fallen in 5 of the previous 6 weeks, going from 1.4 million on May 24 to 307,000 on July 5, the CDC said.

New cases of COVID-19, unfortunately, continued to follow the trend among the larger population: As of July 15, weekly cases in children were up by 179% since dropping to 8,400 on June 24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in a joint report. The 23,551 new cases in children for the week ending July 15 were 15.9% of all cases reported.

With those new cases, the total number of children infected with COVID-19 comes to almost 4.1 million since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said. The CDC data indicate that just over 5.35 million children aged 12-15 years and 3.53 million 16- and 17-year-olds have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 6.8 million children aged 12-17 are fully vaccinated.

Fully vaccinated children represent 26.4% of all 12- to 15-year-olds and 38.3% of the 16- 17-year-olds as of July 19. The corresponding numbers for those who have received at least one dose are 35.2% (ages 12-15) and 46.8% (16-17), the CDC said.

The AAP recently recommended in-person learning with universal masking in schools this fall “because a significant portion of the student population is not yet eligible for vaccines. ... Many schools will not have a system to monitor vaccine status of students, teachers and staff, and some communities overall have low vaccination uptake where the virus may be circulating more prominently.”

Children aged 12-15 years represented 13.5% of all first vaccinations received during the 2 weeks ending July 19, compared with 11.5% for the 2 weeks ending July 12, marking the first increase since the end of May. First vaccinations in 16- and 17-year-olds, who make up a much smaller share of the U.S. population, also went up, topping 5%, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker.

The total number of vaccine initiations was almost 250,000 for the week ending July 19, after dropping to a low of 201,000 the previous week. Before that, first vaccinations had fallen in 5 of the previous 6 weeks, going from 1.4 million on May 24 to 307,000 on July 5, the CDC said.

New cases of COVID-19, unfortunately, continued to follow the trend among the larger population: As of July 15, weekly cases in children were up by 179% since dropping to 8,400 on June 24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in a joint report. The 23,551 new cases in children for the week ending July 15 were 15.9% of all cases reported.

With those new cases, the total number of children infected with COVID-19 comes to almost 4.1 million since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said. The CDC data indicate that just over 5.35 million children aged 12-15 years and 3.53 million 16- and 17-year-olds have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 6.8 million children aged 12-17 are fully vaccinated.

Fully vaccinated children represent 26.4% of all 12- to 15-year-olds and 38.3% of the 16- 17-year-olds as of July 19. The corresponding numbers for those who have received at least one dose are 35.2% (ages 12-15) and 46.8% (16-17), the CDC said.

The AAP recently recommended in-person learning with universal masking in schools this fall “because a significant portion of the student population is not yet eligible for vaccines. ... Many schools will not have a system to monitor vaccine status of students, teachers and staff, and some communities overall have low vaccination uptake where the virus may be circulating more prominently.”

HIV increases risk for severe COVID-19

according to a report from the World Health Organization on COVID-19 outcomes among people living with HIV. The study primarily included people from South Africa but also some data from other parts of the world, including the United States.

However, the report, presented at the 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021), couldn’t answer some crucial questions clinicians have been wondering about since the COVID-19 pandemic began. For example, was the increase in COVID risk a result of the presence of HIV or because of the immune compromise caused by untreated HIV?

The report didn’t include data on viral load or CD counts, both used to evaluate the health of a person’s immune system. On effective treatment, people living with HIV have a lifespan close to their HIV-negative peers. And effective treatment causes undetectable viral loads which, when maintained for 6 months or more, eliminates transmission of HIV to sexual partners.

What’s clear is that in people with HIV, as in people without HIV, older people, men, and people with diabetes, hypertension, or obesity had the worst outcomes and were most likely to die from COVID-19.

For David Malebranche, MD, MPH, an internal medicine doctor who provides primary care for people in Atlanta, and who was not involved in the study, the WHO study didn’t add anything new. He already recommends the COVID-19 vaccine for all of his patients, HIV-positive or not.

“We don’t have any information from this about the T-cell counts [or] the rates of viral suppression, which I think is tremendously important,” he told this news organization. “To bypass that and not include that in any of the discussion puts the results in a questionable place for me.”

The results come from the WHO Clinical Platform, which culls data from WHO member country surveillance as well as manual case reports from all over the world. By April 29, data on 268,412 people hospitalized with COVID-19 from 37 countries were reported to the platform. Of those, 22,640 people are from the U.S.

A total of 15,522 participants worldwide were living with HIV, 664 in the United States. All U.S. cases were reported from the New York City Health and Hospitals system, Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, and BronxCare Health System in New York City. Almost all of the remaining participants lived in South Africa – 14,682 of the 15,522, or 94.5%.

Of the 15,522 people living with HIV in the overall group, 37.1% of participants were male, and their median age was 45 years. More than 1 in 3 (36.2%) were admitted with severe or critical COVID-19, and nearly one quarter – 23.1% – with a known outcome died. More than half had one or more chronic conditions, including those that themselves are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes, such as hypertension (in 33.2% of the participants), diabetes (22.7%), and BMIs above 30 (16.9%). In addition, 8.9% were smokers, 6.6% had chronic pulmonary disease, and 4.3% had chronic heart disease.

After adjusting for those chronic conditions, age, and sex, people living with HIV had a 6% higher rate of severe or critical COVID-19 illness. When investigators adjusted the analysis additionally to differentiate outcomes based on not just the presence of comorbid conditions but the number of them a person had, that increased risk rose to 13%. HIV itself is a comorbid condition, though it wasn’t counted as one in this adjusted analysis.

It didn’t matter whether researchers looked at risk for severe outcomes or deaths after removing the significant co-occurring conditions or if they looked at number of chronic illnesses (aside from HIV), said Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, medical officer at the World Health Organization and co-author of the analysis.

“Both models show almost identical [adjusted odds ratios], meaning that HIV was independently significantly associated with severe/critical presentation,” she told this news organization.

As for death, the analysis showed that, overall, people living with HIV were 30% more likely to die of COVID-19 compared with those not living with HIV. And while this held true even when they adjusted the data for comorbidities, people with HIV were more likely to die if they were over age 65 (risk increased by 82%), male (risk increased by 21%), had diabetes (risk increased by 50%), or had hypertension (risk increased by 26%).

When they broke down the data by WHO region – Africa, Europe, the Americas – investigators found that the increased risk for death held true in Africa. But there were not enough data from the other regions to model mortality risk. What’s more, when they broke the data down by country and excluded South Africa, they found that the elevated risk for death in people living with HIV did not reach statistical significance. Dr. Bertagnolio said she suspects that the small sample sizes from other regions made it impossible to detect a difference, but one could still be present.