User login

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

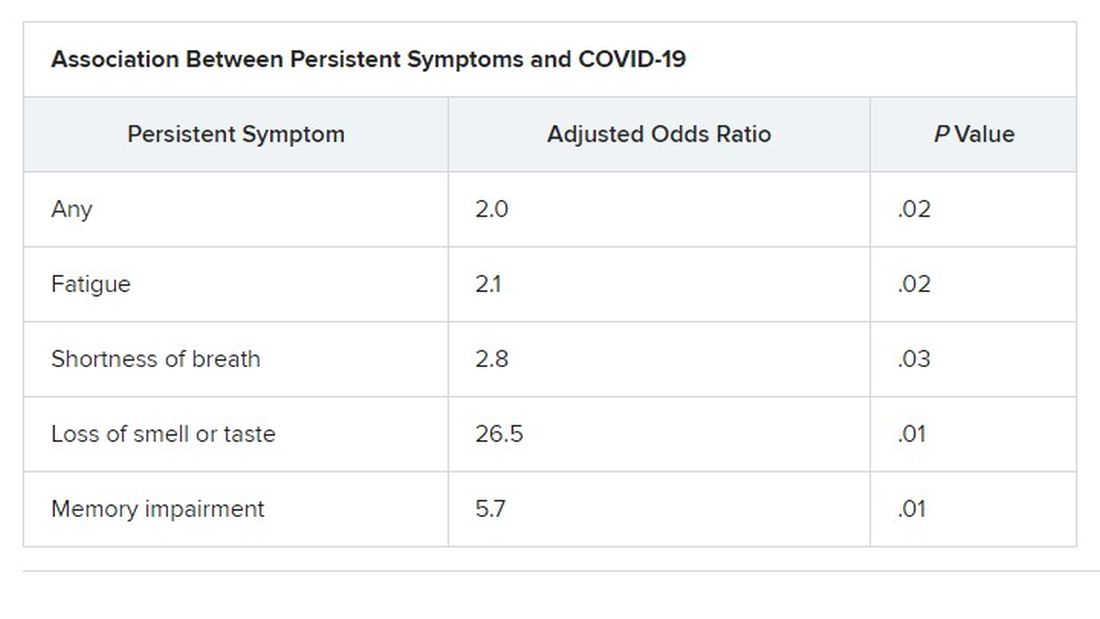

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

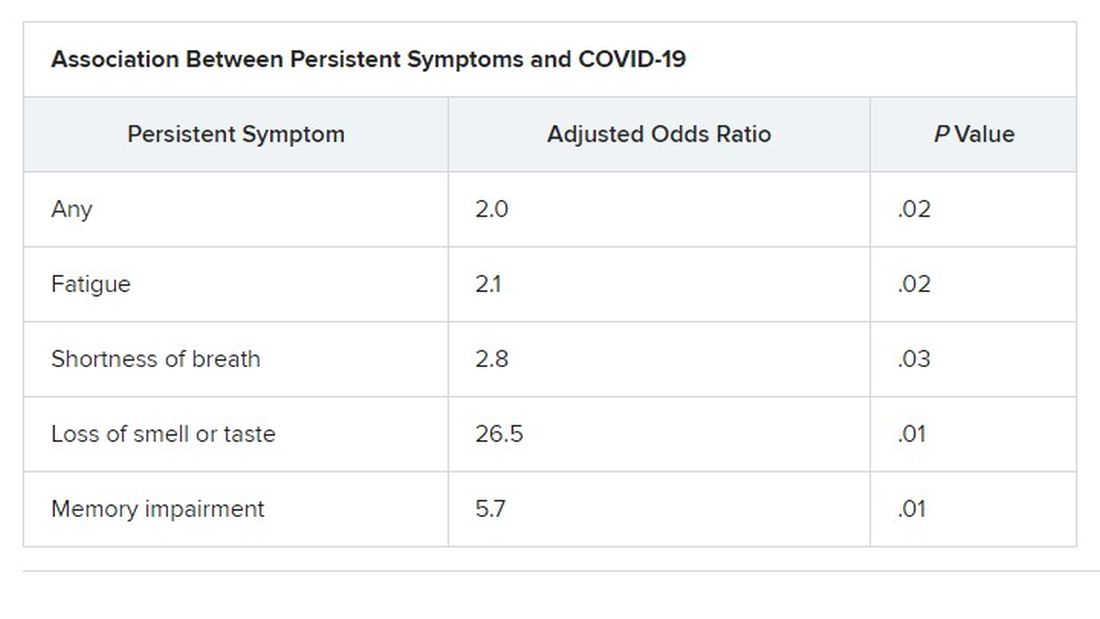

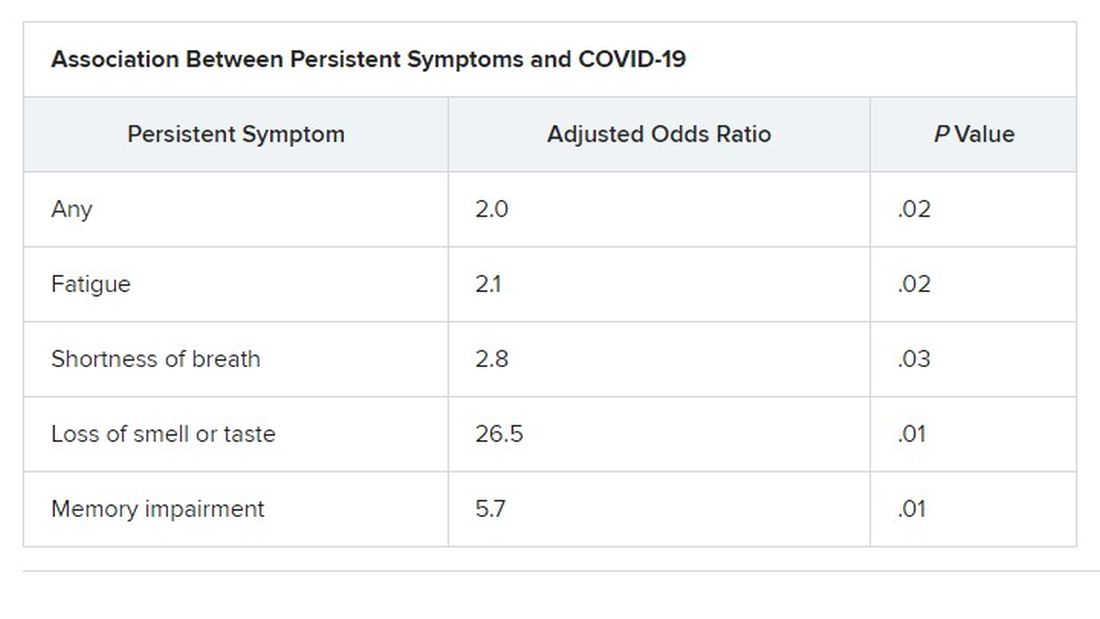

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN CONGRESS OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY & INFECTIOUS DISEASES