User login

Church-based services may help close gaps in mental health care

Black individuals who received mental health services through a church-based program reported high levels of satisfaction, data from a small, qualitative study show.

“This model of providing mental health services adjacent to or supported by a trusted institution, with providers who may have a more nuanced and intimate knowledge of the experiences of and perceptions held by community members, may facilitate important therapy-mediating factors, such as trust,” wrote Angela Coombs, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Black Americans continue to face barriers to mental health services, and fewer than one-third of Black Americans with a mental health condition receive formal mental health care, Dr. Coombs and colleagues reported. Barriers to treatment include stigma and distrust of medical institutions, and strategies are needed to address these barriers to improve access. Consequently, “one approach includes the development of mental health programming and supports with trusted institutions, such as churches,” they said. Data are limited, however, on the perspectives of individuals who have used church-based services.

In the study, published in Psychiatric Services, Dr. Coombs and colleagues recruited 15 adults aged 27-69 years who were receiving or had received mental health services at the HOPE (Healing On Purpose and Evolving) Center, a freestanding mental health clinic affiliated with the First Corinthian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. At the time of the study in 2019, those attending the center (referred to as “innovators” rather than patients or clients to reduce stigma) received 10 free sessions of evidence-based psychotherapy.

Treatment included cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), religiously integrated CBT, and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) to individuals, couples, and families. Group psychotherapy also was an option. Clinicians at the HOPE Center included licensed social workers with doctoral and master’s-level degrees, as well as supervised social work student interns.

Study participants took part in a 30-minute interview, in person or by phone, with a female psychiatrist who was not employed by the HOPE Center or involved in treating the patients. There were 15 participants: 13 women and 2 men, with mean ages of 48 and 51 years, respectively; 14 identified as Black, non-Hispanic. Most (13 individuals) identified as heterosexual, 11 had never married, and 14 had some college or technical school education.

Notably, 11 participants reported attending church once a week, and 13 said they considered religion or spirituality highly important. Participants “reported that services that could integrate their spiritual beliefs with their current mental health challenges enhanced the therapeutic experience,” the researchers said.

Positive messaging about mental health care from the church and senior pastor also encouraged the participants to take advantage of the HOPE Center services.

As one participant said, “I’ve always believed that I can handle my own issues ... but listening to the pastor always talking about the [HOPE] Center and not to be ashamed if you have weaknesses, that’s when I said, ‘You know what, let me just start seeking mental health services because I really need [them].’ ”

, including recognizing cycles of unproductive behavior, processing traumatic experiences and learning self-love, and embracing meditation at home.

“A common theme among participants was that the HOPE Center provided them with tools to destress, process trauma, and manage anxiety,” the researchers wrote. In particular, several participants cited group sessions on teaching and practicing mindfulness as their favorite services. They described the HOPE Center as a positive, peaceful, and welcoming environment where they felt safe.

Cost issues were important as well. Participants noted that the HOPE Center’s ability to provide services that were free made it easier for them to attend. “Although participants said that it was helpful that the HOPE Center provided referrals to external providers and agencies for additional services, some said they wished that the HOPE Center would provide long-term therapy,” the researchers noted.

Overall, “most participants said that establishing more mental health resources within faith-based spaces could accelerate normalization of seeking and receiving mental health care within religious Black communities,” they said.

The study findings were limited by the absence of clinical data – and data on participants’ frequency and location of church attendance, the researchers noted. In addition, the positive results could be tied to selection bias, Dr. Coombs and colleagues said. Another possible limitation is the overrepresentation of cisgender women among the participants. Still, “the perspectives shared by participants suggest that this model of care may address several important barriers to care faced by some Black American populations,” the researchers wrote.

Bridging gap between spirituality and mental health

In an interview, Atasha Jordan, MD, said Black Americans with mental illnesses have long lacked equal access to mental health services. “However, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, published studies have shown that rates of mental illness increased concurrently with a rise in spirituality and faith. That said, we currently live in a time where mental health and spirituality are more likely to intersect,” noted Dr. Jordan, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

She said it is not surprising that the study participants felt more comfortable receiving mental health services at a clinic that was church affiliated.

“We have known for years that people of faith are more likely to seek comfort for psychological distress from clergy, rather than mental health professionals. Providing a more familiar entry point to mental health services through a church-affiliated mental health clinic helps to bridge the existing gap between spirituality and mental health,” Dr. Jordan said. “For many Black Americans, spirituality is a central component of culturally-informed mental health care.

“Mental health providers may find improved service utilization and outcomes for their patients by collaborating with faith-based organizations or investing time to learn spiritually-based psychotherapies.”

Recently published data, notably a study published May 1, 2021, in Psychiatric Services, continue to support the existing knowledge “that many patients with psychiatric illnesses want increased attention paid to spirituality during their mental health care,” Dr. Jordan noted. “Moreover, they showed that nonreligious clinicians may be more apt than religious clinicians to provide objective, spiritually-oriented mental health care. In this vein, further research aimed at understanding the most effective methods to address spiritual health in times of mental distress can help all mental health providers better meet their patients’ psychiatric and psychological needs.”

Overcoming stigma, mistrust

During the pandemic, clinicians have seen an increase in mental health distress in the form of anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms, Lorenzo Norris, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“Historically, African Americans have faced numerous barriers to mental health care, including stigma and mistrust of medical institutions,” Dr. Norris said. “At this time, perhaps more than in recent decades, novel ways of eliminating and navigating these barriers must be explored in an evidence-based fashion that will inform future interventions.”

Dr. Norris also found that the study findings make sense.

“Historically, the Black church has been a central institution in the community,” he said. “In my personal experience, the church served in a variety of roles, including but not limited to advocacy, employment, social services, peer support, and notably a trusted source of advice pertaining to health. In addition, Black churches may be in an ideal position to serve as culturally sensitive facilitators to build trust,” he said.

The study’s message for clinicians, according to Dr. Norris, is to “carefully consider partnering with faith-based organizations and community leaders if you want to supplement your efforts at decreasing mental health care disparities in the African American community.”

He pointed out, however, that in addition to the small number of participants, the study did not examine clinical outcomes. “So we must be careful how much we take from the initial conclusions,” Dr. Norris said.

Additional research is needed on a much larger scale to add support to the study findings, he said. “This study focused on one church and its particular program,” Dr. Norris noted. “There is likely a great deal of heterogeneity with Black churches and definitely among church members they serve,” he said. “Although it may be tempting to go with an ‘of course it will work’ approach, it is best to have additional qualitative and quantitative research of a much larger scale, with clinical controls that examine the ability of Black churches to address barriers African Americans face in receiving and utilizing mental health services,” he concluded.

Dr. Jordan disclosed receiving a 2021-2022 American Psychiatric Association/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Minority Fellowship Program grant to study mental health literacy in the Black church. Dr. Norris disclosed serving as CEO of the Cleveland Clergy Alliance, a nonprofit organization providing outreach assistance as a mechanism to help seniors and the disabled population through community programming. The study authors reported no disclosures.

Black individuals who received mental health services through a church-based program reported high levels of satisfaction, data from a small, qualitative study show.

“This model of providing mental health services adjacent to or supported by a trusted institution, with providers who may have a more nuanced and intimate knowledge of the experiences of and perceptions held by community members, may facilitate important therapy-mediating factors, such as trust,” wrote Angela Coombs, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Black Americans continue to face barriers to mental health services, and fewer than one-third of Black Americans with a mental health condition receive formal mental health care, Dr. Coombs and colleagues reported. Barriers to treatment include stigma and distrust of medical institutions, and strategies are needed to address these barriers to improve access. Consequently, “one approach includes the development of mental health programming and supports with trusted institutions, such as churches,” they said. Data are limited, however, on the perspectives of individuals who have used church-based services.

In the study, published in Psychiatric Services, Dr. Coombs and colleagues recruited 15 adults aged 27-69 years who were receiving or had received mental health services at the HOPE (Healing On Purpose and Evolving) Center, a freestanding mental health clinic affiliated with the First Corinthian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. At the time of the study in 2019, those attending the center (referred to as “innovators” rather than patients or clients to reduce stigma) received 10 free sessions of evidence-based psychotherapy.

Treatment included cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), religiously integrated CBT, and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) to individuals, couples, and families. Group psychotherapy also was an option. Clinicians at the HOPE Center included licensed social workers with doctoral and master’s-level degrees, as well as supervised social work student interns.

Study participants took part in a 30-minute interview, in person or by phone, with a female psychiatrist who was not employed by the HOPE Center or involved in treating the patients. There were 15 participants: 13 women and 2 men, with mean ages of 48 and 51 years, respectively; 14 identified as Black, non-Hispanic. Most (13 individuals) identified as heterosexual, 11 had never married, and 14 had some college or technical school education.

Notably, 11 participants reported attending church once a week, and 13 said they considered religion or spirituality highly important. Participants “reported that services that could integrate their spiritual beliefs with their current mental health challenges enhanced the therapeutic experience,” the researchers said.

Positive messaging about mental health care from the church and senior pastor also encouraged the participants to take advantage of the HOPE Center services.

As one participant said, “I’ve always believed that I can handle my own issues ... but listening to the pastor always talking about the [HOPE] Center and not to be ashamed if you have weaknesses, that’s when I said, ‘You know what, let me just start seeking mental health services because I really need [them].’ ”

, including recognizing cycles of unproductive behavior, processing traumatic experiences and learning self-love, and embracing meditation at home.

“A common theme among participants was that the HOPE Center provided them with tools to destress, process trauma, and manage anxiety,” the researchers wrote. In particular, several participants cited group sessions on teaching and practicing mindfulness as their favorite services. They described the HOPE Center as a positive, peaceful, and welcoming environment where they felt safe.

Cost issues were important as well. Participants noted that the HOPE Center’s ability to provide services that were free made it easier for them to attend. “Although participants said that it was helpful that the HOPE Center provided referrals to external providers and agencies for additional services, some said they wished that the HOPE Center would provide long-term therapy,” the researchers noted.

Overall, “most participants said that establishing more mental health resources within faith-based spaces could accelerate normalization of seeking and receiving mental health care within religious Black communities,” they said.

The study findings were limited by the absence of clinical data – and data on participants’ frequency and location of church attendance, the researchers noted. In addition, the positive results could be tied to selection bias, Dr. Coombs and colleagues said. Another possible limitation is the overrepresentation of cisgender women among the participants. Still, “the perspectives shared by participants suggest that this model of care may address several important barriers to care faced by some Black American populations,” the researchers wrote.

Bridging gap between spirituality and mental health

In an interview, Atasha Jordan, MD, said Black Americans with mental illnesses have long lacked equal access to mental health services. “However, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, published studies have shown that rates of mental illness increased concurrently with a rise in spirituality and faith. That said, we currently live in a time where mental health and spirituality are more likely to intersect,” noted Dr. Jordan, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

She said it is not surprising that the study participants felt more comfortable receiving mental health services at a clinic that was church affiliated.

“We have known for years that people of faith are more likely to seek comfort for psychological distress from clergy, rather than mental health professionals. Providing a more familiar entry point to mental health services through a church-affiliated mental health clinic helps to bridge the existing gap between spirituality and mental health,” Dr. Jordan said. “For many Black Americans, spirituality is a central component of culturally-informed mental health care.

“Mental health providers may find improved service utilization and outcomes for their patients by collaborating with faith-based organizations or investing time to learn spiritually-based psychotherapies.”

Recently published data, notably a study published May 1, 2021, in Psychiatric Services, continue to support the existing knowledge “that many patients with psychiatric illnesses want increased attention paid to spirituality during their mental health care,” Dr. Jordan noted. “Moreover, they showed that nonreligious clinicians may be more apt than religious clinicians to provide objective, spiritually-oriented mental health care. In this vein, further research aimed at understanding the most effective methods to address spiritual health in times of mental distress can help all mental health providers better meet their patients’ psychiatric and psychological needs.”

Overcoming stigma, mistrust

During the pandemic, clinicians have seen an increase in mental health distress in the form of anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms, Lorenzo Norris, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“Historically, African Americans have faced numerous barriers to mental health care, including stigma and mistrust of medical institutions,” Dr. Norris said. “At this time, perhaps more than in recent decades, novel ways of eliminating and navigating these barriers must be explored in an evidence-based fashion that will inform future interventions.”

Dr. Norris also found that the study findings make sense.

“Historically, the Black church has been a central institution in the community,” he said. “In my personal experience, the church served in a variety of roles, including but not limited to advocacy, employment, social services, peer support, and notably a trusted source of advice pertaining to health. In addition, Black churches may be in an ideal position to serve as culturally sensitive facilitators to build trust,” he said.

The study’s message for clinicians, according to Dr. Norris, is to “carefully consider partnering with faith-based organizations and community leaders if you want to supplement your efforts at decreasing mental health care disparities in the African American community.”

He pointed out, however, that in addition to the small number of participants, the study did not examine clinical outcomes. “So we must be careful how much we take from the initial conclusions,” Dr. Norris said.

Additional research is needed on a much larger scale to add support to the study findings, he said. “This study focused on one church and its particular program,” Dr. Norris noted. “There is likely a great deal of heterogeneity with Black churches and definitely among church members they serve,” he said. “Although it may be tempting to go with an ‘of course it will work’ approach, it is best to have additional qualitative and quantitative research of a much larger scale, with clinical controls that examine the ability of Black churches to address barriers African Americans face in receiving and utilizing mental health services,” he concluded.

Dr. Jordan disclosed receiving a 2021-2022 American Psychiatric Association/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Minority Fellowship Program grant to study mental health literacy in the Black church. Dr. Norris disclosed serving as CEO of the Cleveland Clergy Alliance, a nonprofit organization providing outreach assistance as a mechanism to help seniors and the disabled population through community programming. The study authors reported no disclosures.

Black individuals who received mental health services through a church-based program reported high levels of satisfaction, data from a small, qualitative study show.

“This model of providing mental health services adjacent to or supported by a trusted institution, with providers who may have a more nuanced and intimate knowledge of the experiences of and perceptions held by community members, may facilitate important therapy-mediating factors, such as trust,” wrote Angela Coombs, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Black Americans continue to face barriers to mental health services, and fewer than one-third of Black Americans with a mental health condition receive formal mental health care, Dr. Coombs and colleagues reported. Barriers to treatment include stigma and distrust of medical institutions, and strategies are needed to address these barriers to improve access. Consequently, “one approach includes the development of mental health programming and supports with trusted institutions, such as churches,” they said. Data are limited, however, on the perspectives of individuals who have used church-based services.

In the study, published in Psychiatric Services, Dr. Coombs and colleagues recruited 15 adults aged 27-69 years who were receiving or had received mental health services at the HOPE (Healing On Purpose and Evolving) Center, a freestanding mental health clinic affiliated with the First Corinthian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. At the time of the study in 2019, those attending the center (referred to as “innovators” rather than patients or clients to reduce stigma) received 10 free sessions of evidence-based psychotherapy.

Treatment included cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), religiously integrated CBT, and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) to individuals, couples, and families. Group psychotherapy also was an option. Clinicians at the HOPE Center included licensed social workers with doctoral and master’s-level degrees, as well as supervised social work student interns.

Study participants took part in a 30-minute interview, in person or by phone, with a female psychiatrist who was not employed by the HOPE Center or involved in treating the patients. There were 15 participants: 13 women and 2 men, with mean ages of 48 and 51 years, respectively; 14 identified as Black, non-Hispanic. Most (13 individuals) identified as heterosexual, 11 had never married, and 14 had some college or technical school education.

Notably, 11 participants reported attending church once a week, and 13 said they considered religion or spirituality highly important. Participants “reported that services that could integrate their spiritual beliefs with their current mental health challenges enhanced the therapeutic experience,” the researchers said.

Positive messaging about mental health care from the church and senior pastor also encouraged the participants to take advantage of the HOPE Center services.

As one participant said, “I’ve always believed that I can handle my own issues ... but listening to the pastor always talking about the [HOPE] Center and not to be ashamed if you have weaknesses, that’s when I said, ‘You know what, let me just start seeking mental health services because I really need [them].’ ”

, including recognizing cycles of unproductive behavior, processing traumatic experiences and learning self-love, and embracing meditation at home.

“A common theme among participants was that the HOPE Center provided them with tools to destress, process trauma, and manage anxiety,” the researchers wrote. In particular, several participants cited group sessions on teaching and practicing mindfulness as their favorite services. They described the HOPE Center as a positive, peaceful, and welcoming environment where they felt safe.

Cost issues were important as well. Participants noted that the HOPE Center’s ability to provide services that were free made it easier for them to attend. “Although participants said that it was helpful that the HOPE Center provided referrals to external providers and agencies for additional services, some said they wished that the HOPE Center would provide long-term therapy,” the researchers noted.

Overall, “most participants said that establishing more mental health resources within faith-based spaces could accelerate normalization of seeking and receiving mental health care within religious Black communities,” they said.

The study findings were limited by the absence of clinical data – and data on participants’ frequency and location of church attendance, the researchers noted. In addition, the positive results could be tied to selection bias, Dr. Coombs and colleagues said. Another possible limitation is the overrepresentation of cisgender women among the participants. Still, “the perspectives shared by participants suggest that this model of care may address several important barriers to care faced by some Black American populations,” the researchers wrote.

Bridging gap between spirituality and mental health

In an interview, Atasha Jordan, MD, said Black Americans with mental illnesses have long lacked equal access to mental health services. “However, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, published studies have shown that rates of mental illness increased concurrently with a rise in spirituality and faith. That said, we currently live in a time where mental health and spirituality are more likely to intersect,” noted Dr. Jordan, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

She said it is not surprising that the study participants felt more comfortable receiving mental health services at a clinic that was church affiliated.

“We have known for years that people of faith are more likely to seek comfort for psychological distress from clergy, rather than mental health professionals. Providing a more familiar entry point to mental health services through a church-affiliated mental health clinic helps to bridge the existing gap between spirituality and mental health,” Dr. Jordan said. “For many Black Americans, spirituality is a central component of culturally-informed mental health care.

“Mental health providers may find improved service utilization and outcomes for their patients by collaborating with faith-based organizations or investing time to learn spiritually-based psychotherapies.”

Recently published data, notably a study published May 1, 2021, in Psychiatric Services, continue to support the existing knowledge “that many patients with psychiatric illnesses want increased attention paid to spirituality during their mental health care,” Dr. Jordan noted. “Moreover, they showed that nonreligious clinicians may be more apt than religious clinicians to provide objective, spiritually-oriented mental health care. In this vein, further research aimed at understanding the most effective methods to address spiritual health in times of mental distress can help all mental health providers better meet their patients’ psychiatric and psychological needs.”

Overcoming stigma, mistrust

During the pandemic, clinicians have seen an increase in mental health distress in the form of anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms, Lorenzo Norris, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“Historically, African Americans have faced numerous barriers to mental health care, including stigma and mistrust of medical institutions,” Dr. Norris said. “At this time, perhaps more than in recent decades, novel ways of eliminating and navigating these barriers must be explored in an evidence-based fashion that will inform future interventions.”

Dr. Norris also found that the study findings make sense.

“Historically, the Black church has been a central institution in the community,” he said. “In my personal experience, the church served in a variety of roles, including but not limited to advocacy, employment, social services, peer support, and notably a trusted source of advice pertaining to health. In addition, Black churches may be in an ideal position to serve as culturally sensitive facilitators to build trust,” he said.

The study’s message for clinicians, according to Dr. Norris, is to “carefully consider partnering with faith-based organizations and community leaders if you want to supplement your efforts at decreasing mental health care disparities in the African American community.”

He pointed out, however, that in addition to the small number of participants, the study did not examine clinical outcomes. “So we must be careful how much we take from the initial conclusions,” Dr. Norris said.

Additional research is needed on a much larger scale to add support to the study findings, he said. “This study focused on one church and its particular program,” Dr. Norris noted. “There is likely a great deal of heterogeneity with Black churches and definitely among church members they serve,” he said. “Although it may be tempting to go with an ‘of course it will work’ approach, it is best to have additional qualitative and quantitative research of a much larger scale, with clinical controls that examine the ability of Black churches to address barriers African Americans face in receiving and utilizing mental health services,” he concluded.

Dr. Jordan disclosed receiving a 2021-2022 American Psychiatric Association/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Minority Fellowship Program grant to study mental health literacy in the Black church. Dr. Norris disclosed serving as CEO of the Cleveland Clergy Alliance, a nonprofit organization providing outreach assistance as a mechanism to help seniors and the disabled population through community programming. The study authors reported no disclosures.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

CDC panel updates info on rare side effect after J&J vaccine

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exploring your fishpond: Steps toward managing anxiety in the age of COVID

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.

It also helps with anxiety to reach out and help someone else. Is there a neighbor you’re concerned about? By and large, this is something many communities have done well. The challenge is we’ve been avoiding each other physically for a long time. So, some of the standard ways of helping each other out, like volunteering at a food bank, have been a little problematic. But there are ways to have minimal people on staff to reduce exposure.

One thing I recommend with any type of anxiety is to learn how to control your breathing. Take breaths through the nose several times a day and teach yourself how to slow down. Another thing that helps many people is contact with animals – especially horses, dogs, and cats. You may not be able to adopt an animal, but you could work at a rescue shelter or other facilities. People can benefit from the nonverbal cues of an animal. A friend of mine got a shelter cat. It sleeps with her and licks her when she feels anxious.

Meditation and yoga are also useful. This is not for everyone, but it’s a way to turn down the level of “buzz” or anxiety. Don’t overdo it on caffeine or other things that increase anxiety. I would stay away from illicit drugs, as they increase anxiety.

Q: What do you say to patients to give them a sense of hope?

A: A lot of people aren’t ready to return to normal; they want to keep the social isolation, the masks, the working from home. We need to show patients what they have control over to minimize their own risk. For example, if they want to wear a mask, then they should wear one. Patients also really like the option of telehealth appointments.

Another way to cope is to identify what’s better about the way things are now and concentrate on those improvements. Here in Maryland, the traffic is so much better in the morning than it once was. There are things I don’t miss, like going to the airport and waiting 5 hours for a flight.

Q: What advice can you give psychiatrists who are experiencing anxiety?

A: We must manage our own anxiety so we can help our patients. Strategies I’ve mentioned are also helpful to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (such as) taking a walk, getting exercise, controlling what you can control. For me, it’s getting dressed, going to work, seeing patients. Having a daily structure, a routine, is important. Many people struggled with this at first. They were working from home and didn’t get much done; they did too much videogaming. It helps to set regular appointments if you’re working from home.

Pre-COVID, many of us got a lot out of our professional meetings. We saw friends there. Now they’re either canceled or we’re doing them virtually, which isn’t the same thing. I think our profession could do a better job of reaching out to each other. We’re used to seeing each other once or twice a year at conventions. I’ve since found it hard to reach out to my colleagues via email. And everyone is tired of Zoom.

If they’re local, ask them to do a safe outdoor activity, a happy hour, a walk. If they’re not, maybe engage with them through a postcard or a phone call.

My colleagues and I go for walks at lunch. There’s a fishpond nearby and we talk to the fish and get a little silly. We sometimes take fish nets with us. People ask what the fish nets are for and we’ll say, “we’re chasing COVID away.”

Dr. Ritchie reported no conflicts of interest.

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.

It also helps with anxiety to reach out and help someone else. Is there a neighbor you’re concerned about? By and large, this is something many communities have done well. The challenge is we’ve been avoiding each other physically for a long time. So, some of the standard ways of helping each other out, like volunteering at a food bank, have been a little problematic. But there are ways to have minimal people on staff to reduce exposure.

One thing I recommend with any type of anxiety is to learn how to control your breathing. Take breaths through the nose several times a day and teach yourself how to slow down. Another thing that helps many people is contact with animals – especially horses, dogs, and cats. You may not be able to adopt an animal, but you could work at a rescue shelter or other facilities. People can benefit from the nonverbal cues of an animal. A friend of mine got a shelter cat. It sleeps with her and licks her when she feels anxious.

Meditation and yoga are also useful. This is not for everyone, but it’s a way to turn down the level of “buzz” or anxiety. Don’t overdo it on caffeine or other things that increase anxiety. I would stay away from illicit drugs, as they increase anxiety.

Q: What do you say to patients to give them a sense of hope?

A: A lot of people aren’t ready to return to normal; they want to keep the social isolation, the masks, the working from home. We need to show patients what they have control over to minimize their own risk. For example, if they want to wear a mask, then they should wear one. Patients also really like the option of telehealth appointments.

Another way to cope is to identify what’s better about the way things are now and concentrate on those improvements. Here in Maryland, the traffic is so much better in the morning than it once was. There are things I don’t miss, like going to the airport and waiting 5 hours for a flight.

Q: What advice can you give psychiatrists who are experiencing anxiety?

A: We must manage our own anxiety so we can help our patients. Strategies I’ve mentioned are also helpful to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (such as) taking a walk, getting exercise, controlling what you can control. For me, it’s getting dressed, going to work, seeing patients. Having a daily structure, a routine, is important. Many people struggled with this at first. They were working from home and didn’t get much done; they did too much videogaming. It helps to set regular appointments if you’re working from home.

Pre-COVID, many of us got a lot out of our professional meetings. We saw friends there. Now they’re either canceled or we’re doing them virtually, which isn’t the same thing. I think our profession could do a better job of reaching out to each other. We’re used to seeing each other once or twice a year at conventions. I’ve since found it hard to reach out to my colleagues via email. And everyone is tired of Zoom.

If they’re local, ask them to do a safe outdoor activity, a happy hour, a walk. If they’re not, maybe engage with them through a postcard or a phone call.

My colleagues and I go for walks at lunch. There’s a fishpond nearby and we talk to the fish and get a little silly. We sometimes take fish nets with us. People ask what the fish nets are for and we’ll say, “we’re chasing COVID away.”

Dr. Ritchie reported no conflicts of interest.

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.

It also helps with anxiety to reach out and help someone else. Is there a neighbor you’re concerned about? By and large, this is something many communities have done well. The challenge is we’ve been avoiding each other physically for a long time. So, some of the standard ways of helping each other out, like volunteering at a food bank, have been a little problematic. But there are ways to have minimal people on staff to reduce exposure.

One thing I recommend with any type of anxiety is to learn how to control your breathing. Take breaths through the nose several times a day and teach yourself how to slow down. Another thing that helps many people is contact with animals – especially horses, dogs, and cats. You may not be able to adopt an animal, but you could work at a rescue shelter or other facilities. People can benefit from the nonverbal cues of an animal. A friend of mine got a shelter cat. It sleeps with her and licks her when she feels anxious.

Meditation and yoga are also useful. This is not for everyone, but it’s a way to turn down the level of “buzz” or anxiety. Don’t overdo it on caffeine or other things that increase anxiety. I would stay away from illicit drugs, as they increase anxiety.

Q: What do you say to patients to give them a sense of hope?

A: A lot of people aren’t ready to return to normal; they want to keep the social isolation, the masks, the working from home. We need to show patients what they have control over to minimize their own risk. For example, if they want to wear a mask, then they should wear one. Patients also really like the option of telehealth appointments.

Another way to cope is to identify what’s better about the way things are now and concentrate on those improvements. Here in Maryland, the traffic is so much better in the morning than it once was. There are things I don’t miss, like going to the airport and waiting 5 hours for a flight.

Q: What advice can you give psychiatrists who are experiencing anxiety?

A: We must manage our own anxiety so we can help our patients. Strategies I’ve mentioned are also helpful to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (such as) taking a walk, getting exercise, controlling what you can control. For me, it’s getting dressed, going to work, seeing patients. Having a daily structure, a routine, is important. Many people struggled with this at first. They were working from home and didn’t get much done; they did too much videogaming. It helps to set regular appointments if you’re working from home.

Pre-COVID, many of us got a lot out of our professional meetings. We saw friends there. Now they’re either canceled or we’re doing them virtually, which isn’t the same thing. I think our profession could do a better job of reaching out to each other. We’re used to seeing each other once or twice a year at conventions. I’ve since found it hard to reach out to my colleagues via email. And everyone is tired of Zoom.

If they’re local, ask them to do a safe outdoor activity, a happy hour, a walk. If they’re not, maybe engage with them through a postcard or a phone call.

My colleagues and I go for walks at lunch. There’s a fishpond nearby and we talk to the fish and get a little silly. We sometimes take fish nets with us. People ask what the fish nets are for and we’ll say, “we’re chasing COVID away.”

Dr. Ritchie reported no conflicts of interest.

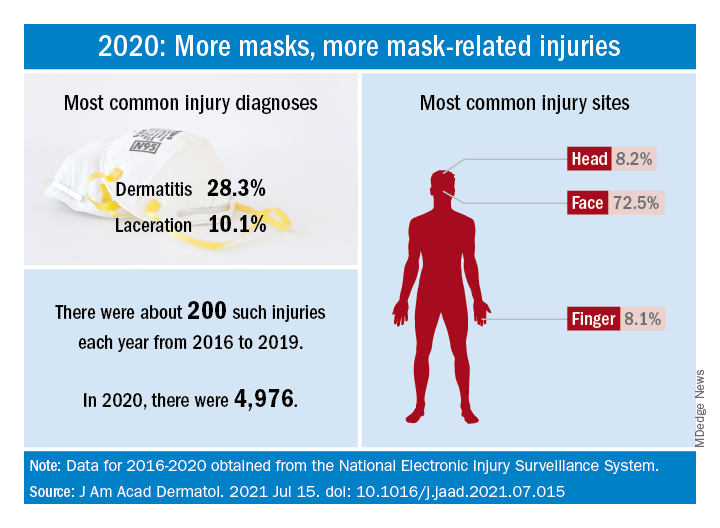

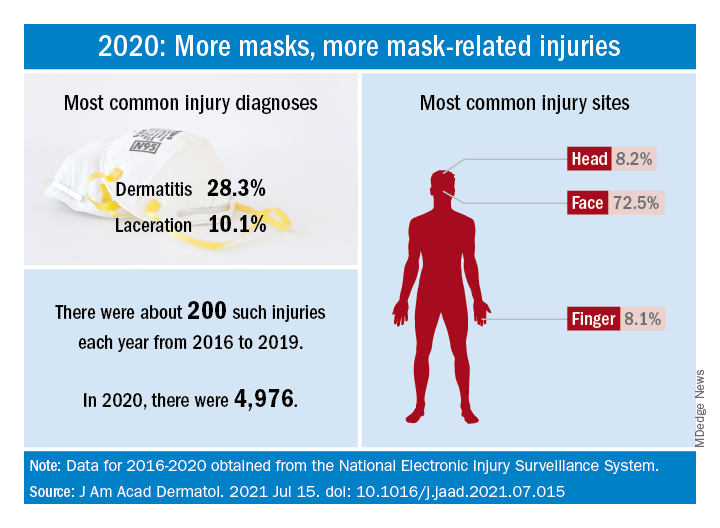

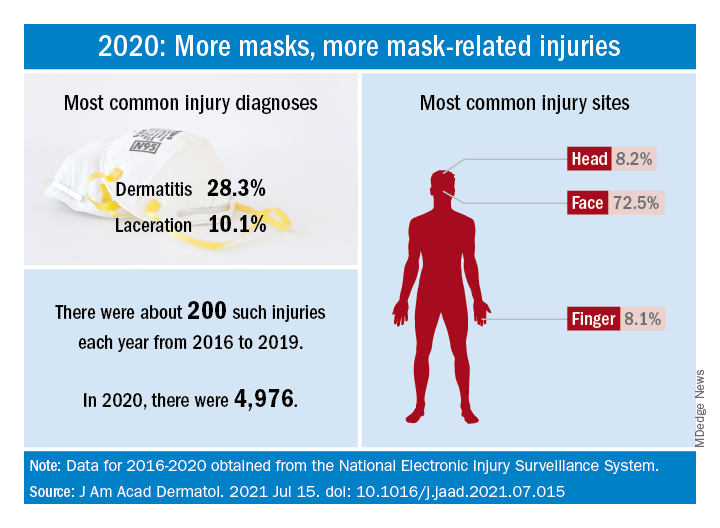

Face mask–related injuries rose dramatically in 2020

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Twofold increased risk for death from COVID-19 in psych patients

compared with those without a psychiatric diagnosis, according to the results of the largest study of its kind to date.

These findings, the investigators noted, highlight the need to prioritize vaccination in patients with preexisting mental health disorders.

“We have proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that there are increased risks” among psychiatric patients who get COVID-19, study investigator Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, psychiatrist and postdoctoral researcher, University Psychiatric Hospital Campus Duffel and University of Antwerp (Belgium), told this news organization.

“Doctors need to look at these patients the same way they would other high-risk people, for example those with diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” all of whom should be protected against COVID-19, Dr. De Picker added.

The study was published online July 15, 2021, in Lancet Psychiatry.

Risk by mental illness type

The systematic review included 33 studies from 22 countries that reported risk estimates for mortality, hospitalization, and ICU admission in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The meta-analysis included 23 of these studies with a total of 1.47 million participants. Of these, 43,938 had a psychiatric disorder.

The primary outcome was mortality after COVID-19. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization and ICU admission after COVID-19. Researchers adjusted for age, sex, and other covariates.

Results showed the presence of any comorbid mental illness was associated with an increased risk for death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (odds ratio, 2.00; 95% confidence interval, 1.58-2.54; P < .0001).

When researchers stratified mortality risk by psychiatric disorder type, the most robust associations were for psychotic and mood disorders. Substance use disorders, intellectual disabilities, and developmental disorders were associated with higher mortality only in crude estimates. There was no increased death risk associated with anxiety disorders.

“That there are differences between the various types of disorders was an interesting finding,” said Dr. De Picker, adding that previous research “just lumped together all diagnostic categories.”

Potential mechanisms

The study did not explore why psychiatric illness raise the risk for death in the setting of COVID-19, so potential mechanisms are purely speculative. However, the investigators believe it may reflect biological processes such as immune-inflammatory alterations.

Psychotic disorders and mood disorders in particular, are associated with immune changes, including immunogenetic abnormalities, raised cytokine concentrations, autoantibodies, acute-phase proteins, and aberrant counts of leukocyte cell types, said Dr. De Picker.

She likened this to elderly people being at increased risk following COVID-19 because their immune system is compromised and less able to fight infection.

There are likely other factors at play, said Dr. De Picker. These could include social isolation and lifestyle factors like poor diet, physical inactivity, high alcohol and tobacco use, and sleep disturbances.

In addition, psychiatric patients have a higher prevalence of comorbidities including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease, which could also play a role.

The increased mortality might also reflect reduced access to care. “Some of these patients may be living in difficult socioeconomic conditions,” said Dr. De Picker.

She noted that, while the in-hospital mortality was not increased, the risk was significantly increased in samples that were outside of the hospital. This reinforces the need for providing close monitoring and early referral to hospital for psychiatric patients with COVID-19.

Mortality varied significantly among countries, with the lowest risk in Europe and the United States. This difference might be attributable to differences in health care systems and access to care, said Dr. De Picker.

Overall, the risk for hospitalization was about double for COVID patients with a mental illness, but when stratified by disorder, there was only a significantly increased risk for substance use and mood disorders. “But mood disorders were not even significant any more after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbid conditions, and we don’t see an increased risk for psychotic disorders whereas they had the highest mortality risks,” said Dr. De Picker.

Psych meds a risk factor?

The studies were primarily based on electronic medical records, so investigators were unable to carry out “a fine grain analysis” into clinical factors affecting outcomes, she noted.

Antipsychotics were consistently associated with an increased risk for mortality (adjusted OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.81-3.25), as were anxiolytics (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.15-1.88).

“There are some theoretical reasons why we believe there could be a risk associated with these drugs,” said Dr. De Picker. For example, antipsychotics can increase the risk for cardiac arrhythmias and thromboembolic events, and cause interactions with drugs used to treat COVID-19.

As for anxiolytics, especially benzodiazepines, these drugs are associated with respiratory risk and with all-cause mortality. “So you could imagine that someone who is infected with a respiratory virus and [is] then using these drugs on top of that would have a worse outcome,” said Dr. De Picker.

In contrast to antipsychotics and anxiolytics, antidepressants did not increase mortality risk.

Dr. De Picker noted a new study by French researchers showing a protective effect of certain serotonergic antidepressants on COVID outcomes, including mortality.

There was no robust evidence of an increased risk for ICU admission for patients with mental disorders. However, the authors noted some studies included small samples of patients with psychiatric disorders, “contributing to a low certainty of evidence for ICU admission.”

Dr. De Picker criticized COVID vaccine policies that don’t prioritize patients with psychiatric disorders. In many countries, groups that were initially green-lighted for the vaccine included health care workers, the elderly, and those with underlying conditions such as diabetes, obesity and even mild hypertension – but not mental illness, which is also an underlying risk.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jonathan E. Alpert, MD, PhD, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Council on Research, called it “outstanding” and the largest of its kind.

“There have been a number of studies that have come to similar conclusions, that people with psychiatric illness are at greater risk for poorer outcomes, but because any given study had a relatively limited sample, perhaps from one health system or one country, there were some inconsistencies,” said Dr. Alpert.

“This is the strongest report so far that has made the point that people with psychiatric illness are a vulnerable population for a negative outcome from COVID, including the most worrisome – mortality.”

The study helps drive home a “very important public health lesson” that applies to COVID-19 but goes “beyond,” said Dr. Alpert.

“As a society, we need to keep in mind that people with serious mental disorders are a vulnerable population for poorer outcomes in most general medical conditions,” he stressed, “whether it’s cancer or heart disease or diabetes, and special efforts need to be made to reach out to those populations.”

Dr. Alpert agreed that, at the start of the pandemic, psychiatric patients in the United States were not prioritized for vaccination, and although psychiatric patients may initially have found it difficult to navigate the health care system to learn where and how to get a COVID shot, today that barrier has mostly been removed.

“Our patients are at least as willing as any other subgroup to get the vaccine, and that includes people with psychotic disorders,” he said.

The study was supported by the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Immuno-NeuroPsychiatry network and Fondazione Centro San Raffaele (Milan). Dr. De Picker reported receiving grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen outside the submitted work. She is a member of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Immuno-NeuroPsychiatry Thematic Working Group.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with those without a psychiatric diagnosis, according to the results of the largest study of its kind to date.

These findings, the investigators noted, highlight the need to prioritize vaccination in patients with preexisting mental health disorders.

“We have proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that there are increased risks” among psychiatric patients who get COVID-19, study investigator Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, psychiatrist and postdoctoral researcher, University Psychiatric Hospital Campus Duffel and University of Antwerp (Belgium), told this news organization.

“Doctors need to look at these patients the same way they would other high-risk people, for example those with diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” all of whom should be protected against COVID-19, Dr. De Picker added.

The study was published online July 15, 2021, in Lancet Psychiatry.

Risk by mental illness type

The systematic review included 33 studies from 22 countries that reported risk estimates for mortality, hospitalization, and ICU admission in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The meta-analysis included 23 of these studies with a total of 1.47 million participants. Of these, 43,938 had a psychiatric disorder.

The primary outcome was mortality after COVID-19. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization and ICU admission after COVID-19. Researchers adjusted for age, sex, and other covariates.

Results showed the presence of any comorbid mental illness was associated with an increased risk for death after SARS-CoV-2 infection (odds ratio, 2.00; 95% confidence interval, 1.58-2.54; P < .0001).

When researchers stratified mortality risk by psychiatric disorder type, the most robust associations were for psychotic and mood disorders. Substance use disorders, intellectual disabilities, and developmental disorders were associated with higher mortality only in crude estimates. There was no increased death risk associated with anxiety disorders.

“That there are differences between the various types of disorders was an interesting finding,” said Dr. De Picker, adding that previous research “just lumped together all diagnostic categories.”

Potential mechanisms

The study did not explore why psychiatric illness raise the risk for death in the setting of COVID-19, so potential mechanisms are purely speculative. However, the investigators believe it may reflect biological processes such as immune-inflammatory alterations.

Psychotic disorders and mood disorders in particular, are associated with immune changes, including immunogenetic abnormalities, raised cytokine concentrations, autoantibodies, acute-phase proteins, and aberrant counts of leukocyte cell types, said Dr. De Picker.

She likened this to elderly people being at increased risk following COVID-19 because their immune system is compromised and less able to fight infection.

There are likely other factors at play, said Dr. De Picker. These could include social isolation and lifestyle factors like poor diet, physical inactivity, high alcohol and tobacco use, and sleep disturbances.