User login

An Unusual Presentation of Congenital Dermal Melanocytosis Fitting the Rare Diagnosis of Dermal Melanocyte Hamartoma

To the Editor:

Dermal melanocytosis is thought to be the result of a defect in melanoblast migration during embryogenesis and is characterized by the presence of functional fusiform and dendritic melanocytes in the dermis. Congenital dermal melanocytosis is classified into various subtypes based on the distribution, morphology, natural history of lesions, and distinctive histologic findings. We present an unusual case of congenital dermal melanocytosis that might fit the rare entity of dermal melanocyte hamartoma (DMH).

|

| Figure 1. Uniform grayish blue patches over the torso with sharp demarcation lines that followed a dermatomal distribution. |

|

| Figure 2. Three conspicuous darker blue macules (arrows) within a bluish patch. |

|

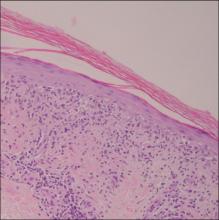

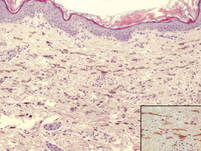

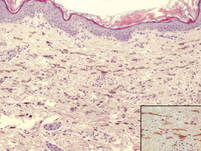

| Figure 3. Intradermal dendritic pigmented melanocytes localized in the upper dermis and arranged parallel to the skin surface (H&E, original magnification ×100 [inset, original magnification ×400]). |

A 4-month-old girl presented with bilateral bluish patches over the trunk and upper extremities. The lesions were present since birth, and remained entirely unchanged during a follow-up period of 18 months. Mental and physical development was normal. There was no family history of pigmentary disorders. On physical examination uniform grayish blue patches were seen over the torso and upper extremities. The patches seemed to follow a dermatomal distribution along the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). Several well-circumscribed, much darker blue macules were scattered within the bluish patches (Figure 2). The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Complete blood cell count and blood chemistry values were within reference range. Skin biopsy specimens from both the grayish blue patches and the conspicuous darker blue macules showed a fair amount of dermal bipolar dendritic pigmented melanocytes arranged parallel to the skin surface with no apparent disturbance of collagen bundles (Figure 3). No melanophages were seen. The clinical, histologic, and laboratory findings were consistent with a diagnosis of congenital dermal melanocytosis. An underlying lysosomal storage disease was ruled out through metabolic screening that included liver function tests, abdominal sonography, and neurologic and ophthalmologic examinations.

The clinical spectrum of congenital dermal melanocytosis includes several clinical entities such as mongolian spots, Ota nevus, Ito nevus, blue nevi, and DMH.1 The differentiation between these different types of dermal melanocytosis can be challenging, especially when the process of melanocytosis is extensive. Among the several types of congenital dermal melanocytosis, Ota or Ito nevi can be ruled out in our patient based on the clinical presentation.

The term dermal melanocyte hamartoma was introduced by Burkhart and Gohara.2 It is characterized by congenital dermal melanocytosis that follows a dermatomal pattern. The original case report included speckled, darker blue macules with a background of grayish blue patches similar to our patient.2 Melanocytes in DMH typically are located in the upper half of the reticular dermis, as opposed to extensive mongolian spots in which ectopic melanocytes usually are found in the lower half of the dermis. The pigmentation in our patient did not change during 22 months of follow-up, which is more consistent with the diagnosis of DMH versus extensive mongolian spots. Our patient did not present with any systemic anomalies. However, a case of congenital melanocytosis and neuroectodermal malformation has been described in the literature.3

Little is known about the etiology of dermal melanocytosis. Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein q polypeptide gene, GNAQ, or guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha 11 gene, GNA11, were found to cause dermal melanocytosis in mice.4 Also, GNAQ mutations have been demonstrated in humans with dermal melanocytosis as well as uveal melanoma.5 Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of dermal melanocytosis is expected to lead to a more accurate classification of dermal pigmentation disorders.

1. Stanford DG, Georgouras KE. Dermal melanocytosis: a clinical spectrum. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:19-25.

2. Burkhart CG, Gohara A. Dermal melanocyte hamartoma: a distinctive new form of dermal melanocytosis.

Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:102-104.

3. Schwartz RA, Cohen-Addad N, Lambert MW, et al. Congenital melanocytosis with myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus. Cutis. 1986;37:37-39.

4. Van Raamsdonk CD, Fitch KR, Fuchs H, et al. Effects of G-protein mutations on skin color. Nat Genet. 2004;36:961-968.

5. Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue nevi. Nature. 2009;457:599-602.

To the Editor:

Dermal melanocytosis is thought to be the result of a defect in melanoblast migration during embryogenesis and is characterized by the presence of functional fusiform and dendritic melanocytes in the dermis. Congenital dermal melanocytosis is classified into various subtypes based on the distribution, morphology, natural history of lesions, and distinctive histologic findings. We present an unusual case of congenital dermal melanocytosis that might fit the rare entity of dermal melanocyte hamartoma (DMH).

|

| Figure 1. Uniform grayish blue patches over the torso with sharp demarcation lines that followed a dermatomal distribution. |

|

| Figure 2. Three conspicuous darker blue macules (arrows) within a bluish patch. |

|

| Figure 3. Intradermal dendritic pigmented melanocytes localized in the upper dermis and arranged parallel to the skin surface (H&E, original magnification ×100 [inset, original magnification ×400]). |

A 4-month-old girl presented with bilateral bluish patches over the trunk and upper extremities. The lesions were present since birth, and remained entirely unchanged during a follow-up period of 18 months. Mental and physical development was normal. There was no family history of pigmentary disorders. On physical examination uniform grayish blue patches were seen over the torso and upper extremities. The patches seemed to follow a dermatomal distribution along the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). Several well-circumscribed, much darker blue macules were scattered within the bluish patches (Figure 2). The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Complete blood cell count and blood chemistry values were within reference range. Skin biopsy specimens from both the grayish blue patches and the conspicuous darker blue macules showed a fair amount of dermal bipolar dendritic pigmented melanocytes arranged parallel to the skin surface with no apparent disturbance of collagen bundles (Figure 3). No melanophages were seen. The clinical, histologic, and laboratory findings were consistent with a diagnosis of congenital dermal melanocytosis. An underlying lysosomal storage disease was ruled out through metabolic screening that included liver function tests, abdominal sonography, and neurologic and ophthalmologic examinations.

The clinical spectrum of congenital dermal melanocytosis includes several clinical entities such as mongolian spots, Ota nevus, Ito nevus, blue nevi, and DMH.1 The differentiation between these different types of dermal melanocytosis can be challenging, especially when the process of melanocytosis is extensive. Among the several types of congenital dermal melanocytosis, Ota or Ito nevi can be ruled out in our patient based on the clinical presentation.

The term dermal melanocyte hamartoma was introduced by Burkhart and Gohara.2 It is characterized by congenital dermal melanocytosis that follows a dermatomal pattern. The original case report included speckled, darker blue macules with a background of grayish blue patches similar to our patient.2 Melanocytes in DMH typically are located in the upper half of the reticular dermis, as opposed to extensive mongolian spots in which ectopic melanocytes usually are found in the lower half of the dermis. The pigmentation in our patient did not change during 22 months of follow-up, which is more consistent with the diagnosis of DMH versus extensive mongolian spots. Our patient did not present with any systemic anomalies. However, a case of congenital melanocytosis and neuroectodermal malformation has been described in the literature.3

Little is known about the etiology of dermal melanocytosis. Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein q polypeptide gene, GNAQ, or guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha 11 gene, GNA11, were found to cause dermal melanocytosis in mice.4 Also, GNAQ mutations have been demonstrated in humans with dermal melanocytosis as well as uveal melanoma.5 Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of dermal melanocytosis is expected to lead to a more accurate classification of dermal pigmentation disorders.

To the Editor:

Dermal melanocytosis is thought to be the result of a defect in melanoblast migration during embryogenesis and is characterized by the presence of functional fusiform and dendritic melanocytes in the dermis. Congenital dermal melanocytosis is classified into various subtypes based on the distribution, morphology, natural history of lesions, and distinctive histologic findings. We present an unusual case of congenital dermal melanocytosis that might fit the rare entity of dermal melanocyte hamartoma (DMH).

|

| Figure 1. Uniform grayish blue patches over the torso with sharp demarcation lines that followed a dermatomal distribution. |

|

| Figure 2. Three conspicuous darker blue macules (arrows) within a bluish patch. |

|

| Figure 3. Intradermal dendritic pigmented melanocytes localized in the upper dermis and arranged parallel to the skin surface (H&E, original magnification ×100 [inset, original magnification ×400]). |

A 4-month-old girl presented with bilateral bluish patches over the trunk and upper extremities. The lesions were present since birth, and remained entirely unchanged during a follow-up period of 18 months. Mental and physical development was normal. There was no family history of pigmentary disorders. On physical examination uniform grayish blue patches were seen over the torso and upper extremities. The patches seemed to follow a dermatomal distribution along the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). Several well-circumscribed, much darker blue macules were scattered within the bluish patches (Figure 2). The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Complete blood cell count and blood chemistry values were within reference range. Skin biopsy specimens from both the grayish blue patches and the conspicuous darker blue macules showed a fair amount of dermal bipolar dendritic pigmented melanocytes arranged parallel to the skin surface with no apparent disturbance of collagen bundles (Figure 3). No melanophages were seen. The clinical, histologic, and laboratory findings were consistent with a diagnosis of congenital dermal melanocytosis. An underlying lysosomal storage disease was ruled out through metabolic screening that included liver function tests, abdominal sonography, and neurologic and ophthalmologic examinations.

The clinical spectrum of congenital dermal melanocytosis includes several clinical entities such as mongolian spots, Ota nevus, Ito nevus, blue nevi, and DMH.1 The differentiation between these different types of dermal melanocytosis can be challenging, especially when the process of melanocytosis is extensive. Among the several types of congenital dermal melanocytosis, Ota or Ito nevi can be ruled out in our patient based on the clinical presentation.

The term dermal melanocyte hamartoma was introduced by Burkhart and Gohara.2 It is characterized by congenital dermal melanocytosis that follows a dermatomal pattern. The original case report included speckled, darker blue macules with a background of grayish blue patches similar to our patient.2 Melanocytes in DMH typically are located in the upper half of the reticular dermis, as opposed to extensive mongolian spots in which ectopic melanocytes usually are found in the lower half of the dermis. The pigmentation in our patient did not change during 22 months of follow-up, which is more consistent with the diagnosis of DMH versus extensive mongolian spots. Our patient did not present with any systemic anomalies. However, a case of congenital melanocytosis and neuroectodermal malformation has been described in the literature.3

Little is known about the etiology of dermal melanocytosis. Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein q polypeptide gene, GNAQ, or guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha 11 gene, GNA11, were found to cause dermal melanocytosis in mice.4 Also, GNAQ mutations have been demonstrated in humans with dermal melanocytosis as well as uveal melanoma.5 Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of dermal melanocytosis is expected to lead to a more accurate classification of dermal pigmentation disorders.

1. Stanford DG, Georgouras KE. Dermal melanocytosis: a clinical spectrum. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:19-25.

2. Burkhart CG, Gohara A. Dermal melanocyte hamartoma: a distinctive new form of dermal melanocytosis.

Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:102-104.

3. Schwartz RA, Cohen-Addad N, Lambert MW, et al. Congenital melanocytosis with myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus. Cutis. 1986;37:37-39.

4. Van Raamsdonk CD, Fitch KR, Fuchs H, et al. Effects of G-protein mutations on skin color. Nat Genet. 2004;36:961-968.

5. Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue nevi. Nature. 2009;457:599-602.

1. Stanford DG, Georgouras KE. Dermal melanocytosis: a clinical spectrum. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:19-25.

2. Burkhart CG, Gohara A. Dermal melanocyte hamartoma: a distinctive new form of dermal melanocytosis.

Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:102-104.

3. Schwartz RA, Cohen-Addad N, Lambert MW, et al. Congenital melanocytosis with myelomeningocele and hydrocephalus. Cutis. 1986;37:37-39.

4. Van Raamsdonk CD, Fitch KR, Fuchs H, et al. Effects of G-protein mutations on skin color. Nat Genet. 2004;36:961-968.

5. Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue nevi. Nature. 2009;457:599-602.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis From Ketoconazole

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

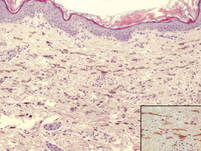

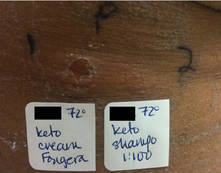

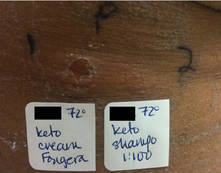

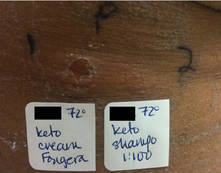

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

- Contact allergy to topical ketoconazole is rare and its cross-reactivity with other imidazole antifungals is unpredictable.

- Patch testing to personal products often is important for detecting rare allergies.

Patching Psoriasis

Patch testing is one of the major diagnostic tools in the evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis. One limitation of patch testing is the use of steroids prior to testing. Because steroids may suppress a positive test reaction, the use of topical steroids on the test site or oral steroids should be discontinued for at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Therefore, it is interesting to consider the effect of biologics on the reliability of patch testing.

Kim et al (Dermatitis. 2014;25:182-190) evaluated the prevalence of positive patch tests in psoriasis patients receiving biologics and whether these results differed from those of psoriasis patients who were not receiving biologics. An institutional review board–approved retrospective chart review was performed for individuals with psoriasis who were patch tested from January 2002 to 2012 at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Patients were selected if they had a history of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and patch testing as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes 696.1, 696.0, and 95044, respectively, in their medical records. Patients were patch tested using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard and cosmetics series. Readings were performed at 48 hours and 72 to 96 hours. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grading system was used to grade reactions.

The chart review included 15 psoriasis patients who were on biologics (cases) and 16 psoriasis patients who were not on biologics (control subjects). The biologics used were ustekinumab (n=7), etanercept (n=4), adalimumab (n=3), and infliximab (n=1). The authors determined that 80% (12/15) of cases had at least 1 positive reaction compared with 81% (13/16) of control subjects, 67% (10/15) of cases had 2+ positive reactions compared with 63% (10/16) of control subjects, and 27% (4/15) of cases had 3+ positive reactions compared with 38% (6/16) of control subjects. These differences were not statistically significant.

Given the limitation of the small number of patients evaluated, the authors concluded that biologics do not appear to influence the abilities of patients with psoriasis to mount a positive patch test.

What’s the issue?

This study is small, but the findings do give an indication that the biologic agents utilized for psoriasis do not suppress patch test reactions. These data are not typically what we collect in this population, but it is nice to know. What has been your experience in patch testing patients on biologic therapy?

Patch testing is one of the major diagnostic tools in the evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis. One limitation of patch testing is the use of steroids prior to testing. Because steroids may suppress a positive test reaction, the use of topical steroids on the test site or oral steroids should be discontinued for at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Therefore, it is interesting to consider the effect of biologics on the reliability of patch testing.

Kim et al (Dermatitis. 2014;25:182-190) evaluated the prevalence of positive patch tests in psoriasis patients receiving biologics and whether these results differed from those of psoriasis patients who were not receiving biologics. An institutional review board–approved retrospective chart review was performed for individuals with psoriasis who were patch tested from January 2002 to 2012 at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Patients were selected if they had a history of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and patch testing as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes 696.1, 696.0, and 95044, respectively, in their medical records. Patients were patch tested using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard and cosmetics series. Readings were performed at 48 hours and 72 to 96 hours. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grading system was used to grade reactions.

The chart review included 15 psoriasis patients who were on biologics (cases) and 16 psoriasis patients who were not on biologics (control subjects). The biologics used were ustekinumab (n=7), etanercept (n=4), adalimumab (n=3), and infliximab (n=1). The authors determined that 80% (12/15) of cases had at least 1 positive reaction compared with 81% (13/16) of control subjects, 67% (10/15) of cases had 2+ positive reactions compared with 63% (10/16) of control subjects, and 27% (4/15) of cases had 3+ positive reactions compared with 38% (6/16) of control subjects. These differences were not statistically significant.

Given the limitation of the small number of patients evaluated, the authors concluded that biologics do not appear to influence the abilities of patients with psoriasis to mount a positive patch test.

What’s the issue?

This study is small, but the findings do give an indication that the biologic agents utilized for psoriasis do not suppress patch test reactions. These data are not typically what we collect in this population, but it is nice to know. What has been your experience in patch testing patients on biologic therapy?

Patch testing is one of the major diagnostic tools in the evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis. One limitation of patch testing is the use of steroids prior to testing. Because steroids may suppress a positive test reaction, the use of topical steroids on the test site or oral steroids should be discontinued for at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Therefore, it is interesting to consider the effect of biologics on the reliability of patch testing.

Kim et al (Dermatitis. 2014;25:182-190) evaluated the prevalence of positive patch tests in psoriasis patients receiving biologics and whether these results differed from those of psoriasis patients who were not receiving biologics. An institutional review board–approved retrospective chart review was performed for individuals with psoriasis who were patch tested from January 2002 to 2012 at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Patients were selected if they had a history of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and patch testing as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes 696.1, 696.0, and 95044, respectively, in their medical records. Patients were patch tested using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard and cosmetics series. Readings were performed at 48 hours and 72 to 96 hours. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grading system was used to grade reactions.

The chart review included 15 psoriasis patients who were on biologics (cases) and 16 psoriasis patients who were not on biologics (control subjects). The biologics used were ustekinumab (n=7), etanercept (n=4), adalimumab (n=3), and infliximab (n=1). The authors determined that 80% (12/15) of cases had at least 1 positive reaction compared with 81% (13/16) of control subjects, 67% (10/15) of cases had 2+ positive reactions compared with 63% (10/16) of control subjects, and 27% (4/15) of cases had 3+ positive reactions compared with 38% (6/16) of control subjects. These differences were not statistically significant.

Given the limitation of the small number of patients evaluated, the authors concluded that biologics do not appear to influence the abilities of patients with psoriasis to mount a positive patch test.

What’s the issue?

This study is small, but the findings do give an indication that the biologic agents utilized for psoriasis do not suppress patch test reactions. These data are not typically what we collect in this population, but it is nice to know. What has been your experience in patch testing patients on biologic therapy?

A New Appraisal of Dermatologic Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus

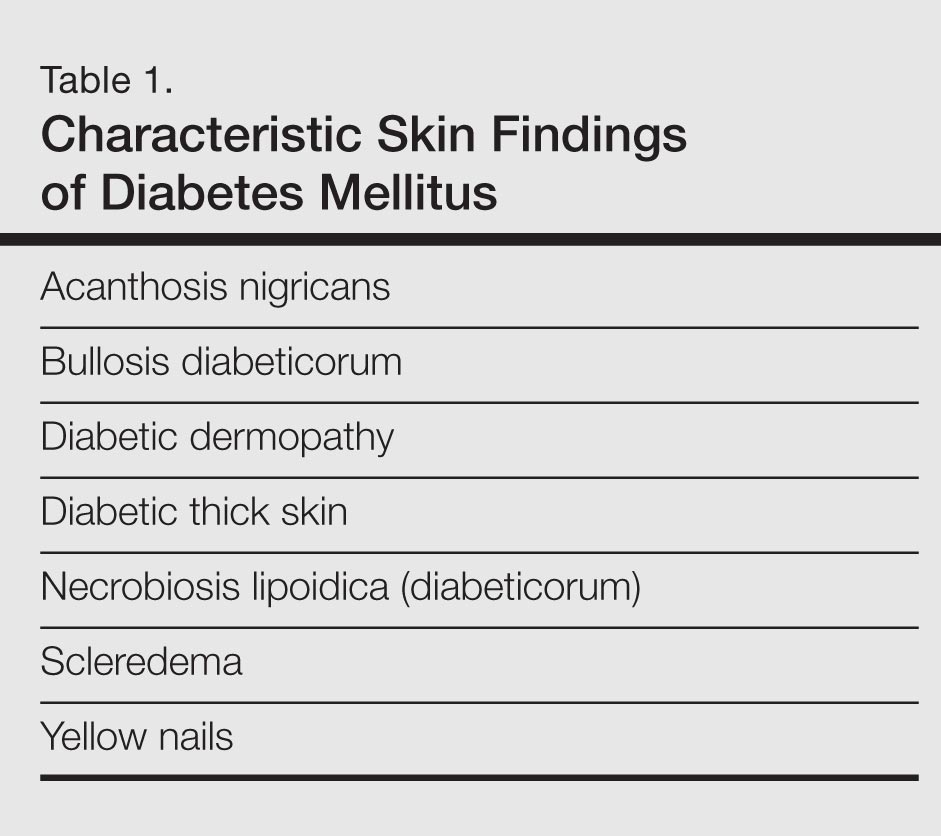

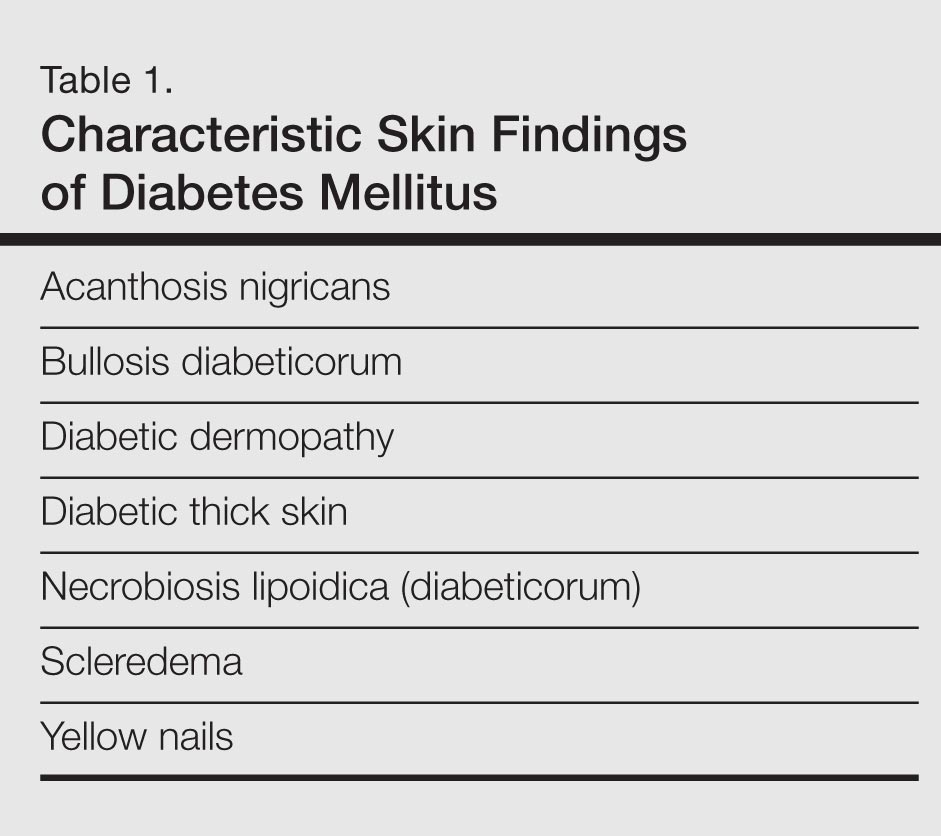

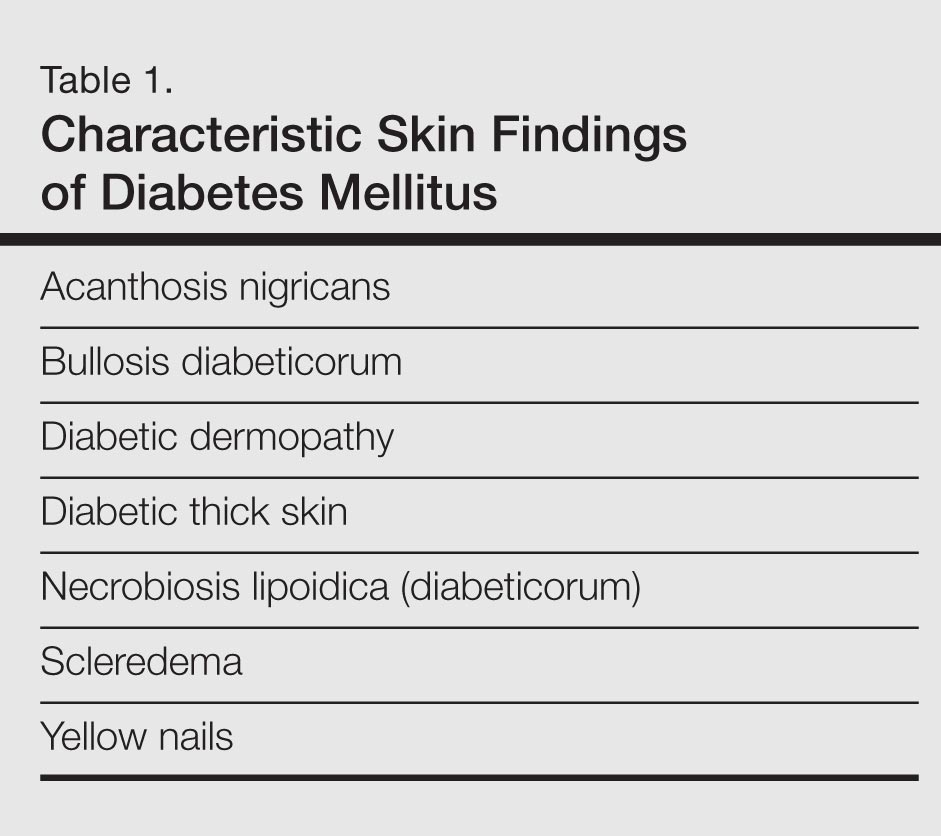

Diabetes mellitus is a morbid and costly condition that carries a high burden of disease for patients (both with and without a diagnosis) and for society as a whole. The economic burden of diabetes in the United States recently was estimated at nearly $250 billion annually,1 and this number continues to rise. The cutaneous manifestations of diabetes are diverse and far-reaching, ranging from benign cosmetic concerns to severe dermatologic conditions. Given the wide range of etiology for diabetes mellitus and its existence on a spectrum of severity, it is perhaps not surprising that some of these entities are the subject of debate (vis-à-vis the strength of association between these skin conditions and diabetes) and can manifest in different forms. However, it is clear that the cutaneous manifestations of diabetes are equally as important to consider and manage as the systemic complications of the disease. In analyzing associations with diabetes, it is important to note that given such a high incidence of diabetes among the general population and its close association with other disease states, such as the metabolic syndrome, studies aimed at determining direct relationships to this entity must be well controlled for confounding factors, which may not even always be possible. Regardless, it is important for dermatologists and dermatology residents to recognize and understand the protean cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus, and this column will explore skin findings that are characteristic of diabetes (Table 1) as well as other dermatoses with a reported but less clear association with diabetes (Table 2).

Skin Findings Characteristic of Diabetes

Diabetic Thick Skin

The association between diabetes and thick skin is well described as either a mobility-limiting affliction of the joints of the hands (cheiroarthropathy) or as an asymptomatic thickening of the skin. It has been estimated that 8% to 36% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes develop some form of skin thickening2; one series also found this association to be true for patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM).3 Skin thickening is readily observable on clinical presentation or ultrasonography, with increasing thickness in many cases associated with long-term disease progression. This increasing thickness was shown histopathologically to be a direct result of activated fibroblasts and increased collagen polymerization, with some similar features to progressive systemic sclerosis.4 Interestingly, even clinically normal skin showed some degree of fibroblast activation in diabetic patients, but collagen fibers in each case were smaller in diameter than those found in progressive systemic sclerosis. This finding clearly has implications on quality of life, as a lack of hand mobility due to the cheiroarthropathy can be severely disabling. Underlining the need for strict glycemic control, it has been suggested that tight control of blood sugar levels can lead to improvement in diabetic thick skin; however, reports of improvement are based on a small sample population.5 Huntley papules are localized to areas on the dorsum of the hands overlying the joints, demonstrating hyperkeratosis and enlarged dermal papillae.6 They also can be found in a minority of patients without diabetes. Interestingly, diabetic thick skin also has been associated with neurologic disorders in diabetes.7 Diabetic thick skin was found to be significantly (P<.05) correlated with diabetic neuropathy, independent of duration of diabetes, age, or glycosylated hemoglobin levels, though no causal or etiologic link between these entities has been proven.

Yellow Nails

Nail changes are well described in diabetes, ranging from periungual telangiectases to complications from infections, such as paronychia; however, a well-recognized finding, especially in elderly diabetic patients, is a characteristic yellowing of the nails, reported to affect up to 40% of patients with diabetes.8 The mechanism behind it likely includes accumulation of glycation end products, which also has been thought to lead to yellowing of the skin, and vascular impairment.9 These nails tend to exhibit slow growth, likely resulting from a nail matrix that is poorly supplied with blood, and also can be more curved than normal with longitudinal ridges (onychorrhexis).10 It is important, however, not to attribute yellow nails to diabetes without considering other causes of yellow nails, such as onychomycosis, yellow nail syndrome, and yellow nails associated with lymphedema or respiratory tract disease (eg, pleural effusion, bronchiectasis).11

Diabetic Dermopathy

Colloquially known as shin spots, diabetic dermopathy is perhaps the most common skin finding in this patient population, though it also can occur in up to 1 in 5 individuals without diabetes.12 Although it is very common, it is not a condition that should be overlooked, as numerous studies have shown an increase in microangiopathic complications such as retinopathy in patients with diabetic dermopathy.13,14 Although follow-up studies may be necessary to fully characterize the relationship between shin spots and diabetes, it certainly is reasonable to be more wary of diabetic patients presenting with many shin spots, as the general consensus is that these areas represent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and cutaneous atrophy in the setting of poor vascular supply, which should prompt analysis of other areas that might be affected by poor vasculature, such as an ophthalmologic examination. Antecedent and perhaps unnoticed trauma has been implicated given a possible underlying neuropathy, but this theory has not been supported by studies.

Bullosis Diabeticorum

Bullosis diabeticorum is a rare but well-described occurrence of self-resolving, nonscarring blisters that arise on the extremities of diabetic patients. This entity should be distinguished from other primary autoimmune blistering disorders and from simple mechanobullous lesions. Several types of bullosis diabeticorum have been described, with the most classic form showing an intraepidermal cleavage plane.15 These lesions tend to resolve in weeks but can be recurrent. The location of the pathology underlines its nonscarring nature, though similar lesions have been reported showing a cleavage plane in the lamina lucida of the dermoepidermal junction, which underlines the confusion in the literature surrounding diabetic bullae.16 Some may even use this term interchangeably with trauma or friction-induced blisters, which diabetics may be prone to develop due to peripheral neuropathy. Confounding reports have stated there is a correlation between bullosis diabeticorum and neuropathy as well as the acral location of these blisters. Although many authors cite the incidence of bullosis diabeticorum being 0.5%,17 no population-based studies have confirmed this figure and some have speculated that the actual incidence is higher.18 In the end, the term bullosis diabeticorum is probably best reserved for a rapidly appearing blister on the extremities of diabetic patients with at most minimal trauma, with a lesion containing sterile fluid and negative immunofluorescence. The mechanism for these blisters is thought to be microangiopathy, with scant blood supply to the skin causing it to be more prone to acantholysis and blister formation.19 This theory was reinforced in a study showing a reduced threshold for suction blister formation in diabetic patients.20 Care should be taken to prevent secondary infections at these sites.

Acanthosis Nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans, which consists of dark brown plaques in the flexural areas, especially the posterior neck and axillae, is a common finding in diabetic patients and is no doubt familiar to clinicians. The pathophysiology of these lesions has been well studied and is a prototype for the effects of insulin resistance in the skin. In this model, high concentrations of insulin binding to insulinlike growth factor receptor in the skin stimulate keratinocyte proliferation,21 leading to the clinical appearance and the histologic finding of hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis, which in turn is responsible for the observed hyperpigmentation. It is an important finding, especially in those without a known history of diabetes, as it can also signal an underlying endocrinopathy (eg, Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, polycystic ovary syndrome) or malignancy (ie, adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract). Several distinct mechanisms of insulin resistance have been described, including insulin resistance due to receptor defects, such as those seen with insulin resistance in NIDDM; autoimmune processes; and postreceptor defects in insulin action.22 Keratolytics and topical retinoids have been used to ameliorate the appearance of these lesions.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica (Diabeticorum)

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum was first described by Urback23 in 1932, but reports of similar lesions were described in nondiabetic patients soon after. The dermatologic community has since come to realize that perhaps a more accurate nomenclature is necrobiosis lipoidica to fully encompass this entity. Clinically, lesions appear as erythematous papules and plaques that expand into a larger well-circumscribed plaque with a waxy yellowish atrophic center, often with telangiectases, and usually presenting in the pretibial area. Lesions can become ulcerated in up to one-third of cases. Necrobiosis lipoidica also is defined by characteristic histologic findings, including important features such as palisaded granulomas arranged in a tierlike fashion, necrotizing vasculitis, collagen degradation, and panniculitis. Necrobiosis lipoidica is still relatively rare, developing in approximately 0.3% of patients with diabetes,24 though its relationship with insulin resistance and diabetes is strong. Approximately two-thirds of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes and an even higher number go on to develop diabetes or have a positive family history of diabetes.

Although these figures are interesting, the data are nearly a half-century-old, and it is unclear if these findings still hold true today. The etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica also remains elusive, with theories focusing on the role of microangiopathy, immunoglobulin deposition leading to vasculitis, structural abnormalities in collagen or fibroblasts, and trauma; however, the true nature of this condition is likely some combination of these factors.25 These lesions are difficult to treat, especially at an advanced stage. Management with topical steroids to limit the inflammatory progression of the lesions is the mainstay of therapy.

Scleredema

Scleredema adultorum (Buschke disease) refers to indurated plaques over the posterior neck and upper back. It is usually thought of as 3 distinct forms. The form that is known to occur in diabetic patients is sometimes referred to as scleredema diabeticorum; the other 2 occur as postinfectious, usually Streptococcus, or malignancy-related forms. The prevalence of scleredema diabeticorum among diabetic individuals most frequently is reported as 2.5%26; however, it is worth noting that other estimates have been as high as 14%.27 Although there has been some correlation between poorly controlled NIDDM, treatment and tight glucose control does not seem to readily resolve these lesions with only few conflicting case studies serving as evidence for and against this premise.28-30 The lesions often are recalcitrant toward a wide variety of treatment approaches. Histopathologic analysis generally reveals a thickened dermis with large collagen bundles, with clear spaces between the collagen representing mucin and increased numbers of mast cells. Proposed mechanisms include stimulation of collagen synthesis by fibroblasts and retarded collagen degradation, likely due to excess glucose.31

Dermatoses Demonstrating an Association With Diabetes

Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a dermatologic condition existing in numerous forms. The generalized form has been suggested to have some association with diabetes. The lesions of GA are classically round, flesh-colored to erythematous papules arising in the dermis that may start on the dorsal extremities where the localized form typically presents, though larger annular plaques or patches may exist in the generalized form. Histologically, GA has a characteristic granulomatous infiltrate and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis, depending on the stage of the evolution. Many studies dating back to the mid-20th century have attempted to elucidate a link between GA and diabetes, with numerous reports showing conflicting results across their study populations.32-36 This issue is further muddled by links between generalized GA and a host of other diseases, such as malignancy, thyroid disease, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. The usual course of GA is spontaneous resolution, including a peculiar phenomenon noted in the literature whereby biopsy of one of the lesions led to clearance of other lesions on the body.37 However, the generalized form may be more difficult to treat, with therapeutic approaches including topical steroids, light therapy, and systemic immunomodulators.

Lichen Planus

A recent small population study in Turkey demonstrated a strong relationship between lichen planus and abnormal glucose tolerance. In this study of 30 patients with lichen planus, approximately half (14/30) had abnormal glucose metabolism and a quarter (8/30) had known diabetes, but larger studies are needed to clarify this relationship.38 Prior to this report, a link between oral lichen planus and diabetes had been shown in larger case series.39,40 Clinically, one may see white plaques with a characteristic lacy reticular pattern in the mouth. At other cutaneous sites, lichen planus generally appears as pruritic, purple, flat-topped polygonal papules. The clinical finding of lichen planus also is linked with many other disease states, most notably hepatitis C virus, but also thymoma, liver disease, and inflammatory bowel disease, among other associations.41

Vitiligo

As an autoimmune entity, it stands to reason that vitiligo may be seen more commonly associated with insulin-dependent diabetes, which has been shown to hold true in one study, while no association was found between later-onset NIDDM and vitiligo.42 Given the nonspecific nature of this association and the relatively common presentation of vitiligo, no special consideration is likely needed when examining a patient with vitiligo, but its presence should remind the clinician that these autoimmune entities tend to travel together.

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis

Although the classic presentation of acquired perforating dermatosis (Kyrle disease) is linked to renal failure, diabetes also has been connected to its presentation. Extremely rare outside of the setting of chronic renal failure, acquired perforating dermatosis occurs in up to 10% of dialysis patients.43,44 It is characterized by papules with a central keratin plug, representing transepidermal elimination of keratin, collagen, and other cellular material; its etiology has not been elucidated. The connection between acquired perforating dermatosis and diabetes is not completely clear; it would seem that renal failure is a prerequisite for itspresentation. A large proportion of renal failure necessitating hemodialysis occurs in patients with diabetic nephropathy, which may explain the coincidence of diabetes, renal failure, and acquired perforating dermatosis.45 The presentation of this cutaneous finding should not, however, affect treatment of the underlying conditions. Symptom relief in the form of topical steroids can be used as a first-line treatment of these often pruritic lesions.

Eruptive Xanthomas

The link between diabetes and eruptive xanthomas seems to be a rather tenuous one, hinging on the fact that many diabetic patients have abnormalities in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. A central feature of eruptive xanthomas is an elevation in triglycerides, which can occur in diabetes. Indeed, it has been estimated that only 0.1% of diabetics will develop eruptive xanthomas,46 and its main importance may be to prompt the physician to treat the hypertriglyceridemia and consider other concerning possibilities such as acute pancreatitis.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic condition that has been shown to have a far-reaching impact both on patients’ quality of life and cardiovascular risk profiles. Data have emerged linking psoriasis with diabetes as an independent risk factor47; although this retrospective study had its limitations, it certainly is interesting to note that patients with psoriasis may have an increased risk for developing diabetes. Perhaps more importantly, though, this study also implied that patients with severe psoriasis may present with diabetes that is more difficult to control, evidenced by increased treatment with systemic therapies as opposed to milder forms of intervention such as diet control.47 There almost certainly are other confounding factors and further studies would serve to reveal the strength of this association, but it is certainly an intriguing concept. Echoing these findings, a more recent nationwide study from Denmark demonstrated that psoriasis is associated with increased incidence of new-onset diabetes, adjusting for numerous confounding factors.48 The relationship between psoriasis and diabetes is worth noting as evidence continues to emerge.

Conclusion

Given the diverse cutaneous manifestations of diabetes, it is important to distinguish those that are directly related to diabetes from those that suggest there may be another underlying process. For example, a new patient presenting to a primary care physician with acanthosis nigricans and yellow nails should immediately trigger a test for a hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level to investigate for diabetes; however, clinicians also should be wary of patients with acanthosis nigricans who report early satiety, as this asso-ciation may be a sign of underlying malignancy. Conversely, the presence of yellow nails in a patient with chronic diabetes should not be ignored. The physician should consider onychomycosis and query the patient about possible respiratory symptoms. In the case of a multisystem disease such as diabetes, it may be challenging to reconcile seemingly disparate skin findings, but having a framework to approach the cutaneous manifestations of diabetes can help to properly identify and treat an individual patient’s afflictions.

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012 [published online instead of print March 16, 2013]. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033-1046.

- Collier A, Matthews DM, Kellett HA, et al. Change in skin thickness associated with cheiroarthropathy in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292:936.

- Fitzcharles MA, Duby S, Waddell RW, et al. Limitation of joint mobility (cheiroarthropathy) in adult noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:251-254.

- Hanna W, Friesen D, Bombardier C, et al. Pathologic features of diabetic thick skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:546-553.

- Lieberman LS, Rosenbloom AL, Riley WJ, et al. Reduced skin thickness with pump administration of insulin. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:940-941.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Borgia F, et al. Finger pebbles in a diabetic patient: Huntley's papules. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:755-756.

- Forst T, Kann P, Pfützner A, et al. Association between "diabetic thick skin syndrome" and neurological disorders in diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 1994;31:73-77.

- Nikoleishvili LR, Kurashvili RB, Virsaladze DK, et al. Characteristic changes of skin and its accessories in type 2 diabetes mellitus [in Russian]. Georgian Med News. 2006:43-46.

- Lithner F. Purpura, pigmentation and yellow nails of the lower extremities in diabetics. Acta Med Scand. 1976;199:203-208.

- Greene RA, Scher RK. Nail changes associated with diabetes mellitus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1015-1021.

- Hiller E, Rosenow EC 3rd, Olsen AM. Pulmonary manifestations of the yellow nail syndrome. Chest. 1972;61:452-458.

- Feingold KR, Elias PM. Endocrine-skin interactions. cutaneous manifestations of pituitary disease, thyroid disease, calcium disorders, and diabetes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:921-940.

- Abdollahi A, Daneshpazhooh M, Amirchaghmaghi E, et al. Dermopathy and retinopathy in diabetes: is there an association? Dermatology, 2007;214:133-136.

- Morgan AJ, Schwartz RA. Diabetic dermopathy: A subtle sign with grave implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:447-451.

- Perez MI, Kohn SR. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:519-531.

- Cantwell AR, Martz W. Idiopathic bullae in diabetics. Bullosis diabeticorum. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:42-44.

- Larsen K, Jensen T, Karlsmark T, Holstein PE. Incidence of bullosis diabeticorum – a controversial cause of chronic foot ulceration. Int Wound J. 2008;5:591-596.

- Lipsky BA, Baker PD, Ahroni JH. Diabetic bullae: 12 cases of a purportedly rare cutaneous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:196-200.

- Basarab T, Munn SE, McGrath J, et al. Bullosis diabeticorum. a case report and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:218-220.

- Bernstein JE, Levine LE, Medenica MM, et al. Reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation in insulin-dependent diabetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:790-791.

- Cruz PD Jr, Hud JA Jr. Excess insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor receptors: proposed mechanism for acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98(suppl 6):S82-S85.

- Romano G, Moretti G, Di Benedetto A, et al. Skin lesions in diabetes mellitus: prevalence and clinical correlations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39:101-106.

- Urback E. Eine neue diabetische Stoffwechseldermatose: Nekrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. Arch. f. Dermat. u Syph. 1932;166:273.

- Muller SA, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. a clinical and pathological investigation of 171 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:272-281.

- Engel MF, Smith JG Jr. The pathogenesis of necrobiosis lipoidica. necrobiosis lipoidica, a form fruste of diabetes mellitus. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:791-797.

- Cole GW, Headley J, Skowsky R. Scleredema diabeticorum: a common and distinct cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:189-192.

- Sattar MA, Diab S, Sugathan TN, et al. Scleroedema diabeticorum: a minor but often unrecognized complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1988;5:465-468.

- Rho YW, Suhr KB, Lee JH, et al. A clinical observation of scleredema adultorum and its relationship to diabetes. J Dermatol. 1998;25:103-107.

- Baillot-Rudoni S, Apostol D, Vaillant G, et al. Implantable pump therapy restores metabolic control and quality of life in type 1 diabetic patients with Buschke's nonsystemic scleroderma. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1710.

- Meguerditchian C, Jacquet P, Béliard S, et al. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: an under recognized skin complication of diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:481-484.

- Behm B, Schreml S, Landthaler M, et al. Skin signs in diabetes mellitus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1203-1211.

- Nebesio CL, Lewis C, Chuang TY. Lack of an association between granuloma annulare and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:122-124.

- Stankler L, Leslie G. Generalized granuloma annulare. a report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1976;95:509-513.

- Williamson DM, Dykes JR. Carbohydrate metabolism in granuloma annulare. J Invest Dermatol. 1972;58:400-404.

- Dabski K, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare: clinical and laboratory findings in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:39-47.

- Veraldi S, Bencini PL, Drudi E, et al. Laboratory abnormalities in granuloma annulare: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:652-653.

- Levin NA, Patterson JW, Yao LL, et al. Resolution of patch-type granuloma annulare lesions after biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:426-429.

- Seyhan M, Ozcan H, Sahin I, et al. High prevalence of glucose metabolism disturbance in patients with lichen planus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:198-202.

- Romero MA, Seoane J, Varela-Centelles P, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus amongst oral lichen planus patients. clinical and pathological characteristics. Med Oral. 2002;7:121-129.

- Albrecht M, Banoczy J, Dinya E, et al. Occurrence of oral leukoplakia and lichen planus in diabetes mellitus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:364-366.

- Lehman JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE. Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:682-694.

- Gould IM, Gray RS, Urbaniak SJ, et al. Vitiligo in diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 1985;113:153-155.

- White CR Jr, Heskel NS, Pokorny DJ. Perforating folliculitis of hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:109-116.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT 3rd, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Muller SA. Dermatologic disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 1966;41:689-703.

- Azfar RS, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Increased risk of diabetes mellitus and likelihood of receiving diabetes mellitus treatment in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:995-1000.

- Khalid U, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, et al. Psoriasis and new-onset diabetes: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2402-2407.

Diabetes mellitus is a morbid and costly condition that carries a high burden of disease for patients (both with and without a diagnosis) and for society as a whole. The economic burden of diabetes in the United States recently was estimated at nearly $250 billion annually,1 and this number continues to rise. The cutaneous manifestations of diabetes are diverse and far-reaching, ranging from benign cosmetic concerns to severe dermatologic conditions. Given the wide range of etiology for diabetes mellitus and its existence on a spectrum of severity, it is perhaps not surprising that some of these entities are the subject of debate (vis-à-vis the strength of association between these skin conditions and diabetes) and can manifest in different forms. However, it is clear that the cutaneous manifestations of diabetes are equally as important to consider and manage as the systemic complications of the disease. In analyzing associations with diabetes, it is important to note that given such a high incidence of diabetes among the general population and its close association with other disease states, such as the metabolic syndrome, studies aimed at determining direct relationships to this entity must be well controlled for confounding factors, which may not even always be possible. Regardless, it is important for dermatologists and dermatology residents to recognize and understand the protean cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus, and this column will explore skin findings that are characteristic of diabetes (Table 1) as well as other dermatoses with a reported but less clear association with diabetes (Table 2).

Skin Findings Characteristic of Diabetes

Diabetic Thick Skin

The association between diabetes and thick skin is well described as either a mobility-limiting affliction of the joints of the hands (cheiroarthropathy) or as an asymptomatic thickening of the skin. It has been estimated that 8% to 36% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes develop some form of skin thickening2; one series also found this association to be true for patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM).3 Skin thickening is readily observable on clinical presentation or ultrasonography, with increasing thickness in many cases associated with long-term disease progression. This increasing thickness was shown histopathologically to be a direct result of activated fibroblasts and increased collagen polymerization, with some similar features to progressive systemic sclerosis.4 Interestingly, even clinically normal skin showed some degree of fibroblast activation in diabetic patients, but collagen fibers in each case were smaller in diameter than those found in progressive systemic sclerosis. This finding clearly has implications on quality of life, as a lack of hand mobility due to the cheiroarthropathy can be severely disabling. Underlining the need for strict glycemic control, it has been suggested that tight control of blood sugar levels can lead to improvement in diabetic thick skin; however, reports of improvement are based on a small sample population.5 Huntley papules are localized to areas on the dorsum of the hands overlying the joints, demonstrating hyperkeratosis and enlarged dermal papillae.6 They also can be found in a minority of patients without diabetes. Interestingly, diabetic thick skin also has been associated with neurologic disorders in diabetes.7 Diabetic thick skin was found to be significantly (P<.05) correlated with diabetic neuropathy, independent of duration of diabetes, age, or glycosylated hemoglobin levels, though no causal or etiologic link between these entities has been proven.

Yellow Nails

Nail changes are well described in diabetes, ranging from periungual telangiectases to complications from infections, such as paronychia; however, a well-recognized finding, especially in elderly diabetic patients, is a characteristic yellowing of the nails, reported to affect up to 40% of patients with diabetes.8 The mechanism behind it likely includes accumulation of glycation end products, which also has been thought to lead to yellowing of the skin, and vascular impairment.9 These nails tend to exhibit slow growth, likely resulting from a nail matrix that is poorly supplied with blood, and also can be more curved than normal with longitudinal ridges (onychorrhexis).10 It is important, however, not to attribute yellow nails to diabetes without considering other causes of yellow nails, such as onychomycosis, yellow nail syndrome, and yellow nails associated with lymphedema or respiratory tract disease (eg, pleural effusion, bronchiectasis).11

Diabetic Dermopathy

Colloquially known as shin spots, diabetic dermopathy is perhaps the most common skin finding in this patient population, though it also can occur in up to 1 in 5 individuals without diabetes.12 Although it is very common, it is not a condition that should be overlooked, as numerous studies have shown an increase in microangiopathic complications such as retinopathy in patients with diabetic dermopathy.13,14 Although follow-up studies may be necessary to fully characterize the relationship between shin spots and diabetes, it certainly is reasonable to be more wary of diabetic patients presenting with many shin spots, as the general consensus is that these areas represent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and cutaneous atrophy in the setting of poor vascular supply, which should prompt analysis of other areas that might be affected by poor vasculature, such as an ophthalmologic examination. Antecedent and perhaps unnoticed trauma has been implicated given a possible underlying neuropathy, but this theory has not been supported by studies.

Bullosis Diabeticorum

Bullosis diabeticorum is a rare but well-described occurrence of self-resolving, nonscarring blisters that arise on the extremities of diabetic patients. This entity should be distinguished from other primary autoimmune blistering disorders and from simple mechanobullous lesions. Several types of bullosis diabeticorum have been described, with the most classic form showing an intraepidermal cleavage plane.15 These lesions tend to resolve in weeks but can be recurrent. The location of the pathology underlines its nonscarring nature, though similar lesions have been reported showing a cleavage plane in the lamina lucida of the dermoepidermal junction, which underlines the confusion in the literature surrounding diabetic bullae.16 Some may even use this term interchangeably with trauma or friction-induced blisters, which diabetics may be prone to develop due to peripheral neuropathy. Confounding reports have stated there is a correlation between bullosis diabeticorum and neuropathy as well as the acral location of these blisters. Although many authors cite the incidence of bullosis diabeticorum being 0.5%,17 no population-based studies have confirmed this figure and some have speculated that the actual incidence is higher.18 In the end, the term bullosis diabeticorum is probably best reserved for a rapidly appearing blister on the extremities of diabetic patients with at most minimal trauma, with a lesion containing sterile fluid and negative immunofluorescence. The mechanism for these blisters is thought to be microangiopathy, with scant blood supply to the skin causing it to be more prone to acantholysis and blister formation.19 This theory was reinforced in a study showing a reduced threshold for suction blister formation in diabetic patients.20 Care should be taken to prevent secondary infections at these sites.

Acanthosis Nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans, which consists of dark brown plaques in the flexural areas, especially the posterior neck and axillae, is a common finding in diabetic patients and is no doubt familiar to clinicians. The pathophysiology of these lesions has been well studied and is a prototype for the effects of insulin resistance in the skin. In this model, high concentrations of insulin binding to insulinlike growth factor receptor in the skin stimulate keratinocyte proliferation,21 leading to the clinical appearance and the histologic finding of hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis, which in turn is responsible for the observed hyperpigmentation. It is an important finding, especially in those without a known history of diabetes, as it can also signal an underlying endocrinopathy (eg, Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, polycystic ovary syndrome) or malignancy (ie, adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract). Several distinct mechanisms of insulin resistance have been described, including insulin resistance due to receptor defects, such as those seen with insulin resistance in NIDDM; autoimmune processes; and postreceptor defects in insulin action.22 Keratolytics and topical retinoids have been used to ameliorate the appearance of these lesions.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica (Diabeticorum)

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum was first described by Urback23 in 1932, but reports of similar lesions were described in nondiabetic patients soon after. The dermatologic community has since come to realize that perhaps a more accurate nomenclature is necrobiosis lipoidica to fully encompass this entity. Clinically, lesions appear as erythematous papules and plaques that expand into a larger well-circumscribed plaque with a waxy yellowish atrophic center, often with telangiectases, and usually presenting in the pretibial area. Lesions can become ulcerated in up to one-third of cases. Necrobiosis lipoidica also is defined by characteristic histologic findings, including important features such as palisaded granulomas arranged in a tierlike fashion, necrotizing vasculitis, collagen degradation, and panniculitis. Necrobiosis lipoidica is still relatively rare, developing in approximately 0.3% of patients with diabetes,24 though its relationship with insulin resistance and diabetes is strong. Approximately two-thirds of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes and an even higher number go on to develop diabetes or have a positive family history of diabetes.

Although these figures are interesting, the data are nearly a half-century-old, and it is unclear if these findings still hold true today. The etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica also remains elusive, with theories focusing on the role of microangiopathy, immunoglobulin deposition leading to vasculitis, structural abnormalities in collagen or fibroblasts, and trauma; however, the true nature of this condition is likely some combination of these factors.25 These lesions are difficult to treat, especially at an advanced stage. Management with topical steroids to limit the inflammatory progression of the lesions is the mainstay of therapy.

Scleredema

Scleredema adultorum (Buschke disease) refers to indurated plaques over the posterior neck and upper back. It is usually thought of as 3 distinct forms. The form that is known to occur in diabetic patients is sometimes referred to as scleredema diabeticorum; the other 2 occur as postinfectious, usually Streptococcus, or malignancy-related forms. The prevalence of scleredema diabeticorum among diabetic individuals most frequently is reported as 2.5%26; however, it is worth noting that other estimates have been as high as 14%.27 Although there has been some correlation between poorly controlled NIDDM, treatment and tight glucose control does not seem to readily resolve these lesions with only few conflicting case studies serving as evidence for and against this premise.28-30 The lesions often are recalcitrant toward a wide variety of treatment approaches. Histopathologic analysis generally reveals a thickened dermis with large collagen bundles, with clear spaces between the collagen representing mucin and increased numbers of mast cells. Proposed mechanisms include stimulation of collagen synthesis by fibroblasts and retarded collagen degradation, likely due to excess glucose.31

Dermatoses Demonstrating an Association With Diabetes

Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a dermatologic condition existing in numerous forms. The generalized form has been suggested to have some association with diabetes. The lesions of GA are classically round, flesh-colored to erythematous papules arising in the dermis that may start on the dorsal extremities where the localized form typically presents, though larger annular plaques or patches may exist in the generalized form. Histologically, GA has a characteristic granulomatous infiltrate and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis, depending on the stage of the evolution. Many studies dating back to the mid-20th century have attempted to elucidate a link between GA and diabetes, with numerous reports showing conflicting results across their study populations.32-36 This issue is further muddled by links between generalized GA and a host of other diseases, such as malignancy, thyroid disease, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. The usual course of GA is spontaneous resolution, including a peculiar phenomenon noted in the literature whereby biopsy of one of the lesions led to clearance of other lesions on the body.37 However, the generalized form may be more difficult to treat, with therapeutic approaches including topical steroids, light therapy, and systemic immunomodulators.

Lichen Planus

A recent small population study in Turkey demonstrated a strong relationship between lichen planus and abnormal glucose tolerance. In this study of 30 patients with lichen planus, approximately half (14/30) had abnormal glucose metabolism and a quarter (8/30) had known diabetes, but larger studies are needed to clarify this relationship.38 Prior to this report, a link between oral lichen planus and diabetes had been shown in larger case series.39,40 Clinically, one may see white plaques with a characteristic lacy reticular pattern in the mouth. At other cutaneous sites, lichen planus generally appears as pruritic, purple, flat-topped polygonal papules. The clinical finding of lichen planus also is linked with many other disease states, most notably hepatitis C virus, but also thymoma, liver disease, and inflammatory bowel disease, among other associations.41

Vitiligo

As an autoimmune entity, it stands to reason that vitiligo may be seen more commonly associated with insulin-dependent diabetes, which has been shown to hold true in one study, while no association was found between later-onset NIDDM and vitiligo.42 Given the nonspecific nature of this association and the relatively common presentation of vitiligo, no special consideration is likely needed when examining a patient with vitiligo, but its presence should remind the clinician that these autoimmune entities tend to travel together.

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis