User login

Practice Question Answers: Allergic Contact Dermatitis, Part 2

1. Which of the following is not a component of fragrance mix?

a. abietic acid

b. α-amylcinnamaldehyde

c. geraniol

d. hydroxycitronellal

e. oakmoss

2. A patient is referred for patch testing for suspected allergic contact dermatitis and is found to have positivity to disperse blue dye 106. The patient should avoid all of the following except:

a. black-colored clothing

b. pure acetate clothing

c. pure polyester clothing

d. purple-colored clothing

e. red-colored clothing

3. A patient with a documented contact allergy to ethylenediamine dihydrochloride should avoid all of the following systemic medications except:

a. aminophylline

b. disulfiram

c. hydroxyzine

d. meclizine

e. promethazine

4. Formaldehyde can cross-react with all of the following except:

a. diazolidinyl urea

b. DMDM hydantoin

c. imidazolidinyl urea

d. para-aminobenzoic acid

e. quaternium-15

5. Colophony can be found in all of the following trees except:

a. cedars

b. firs

c. junipers

d. maples

e. pines

1. Which of the following is not a component of fragrance mix?

a. abietic acid

b. α-amylcinnamaldehyde

c. geraniol

d. hydroxycitronellal

e. oakmoss

2. A patient is referred for patch testing for suspected allergic contact dermatitis and is found to have positivity to disperse blue dye 106. The patient should avoid all of the following except:

a. black-colored clothing

b. pure acetate clothing

c. pure polyester clothing

d. purple-colored clothing

e. red-colored clothing

3. A patient with a documented contact allergy to ethylenediamine dihydrochloride should avoid all of the following systemic medications except:

a. aminophylline

b. disulfiram

c. hydroxyzine

d. meclizine

e. promethazine

4. Formaldehyde can cross-react with all of the following except:

a. diazolidinyl urea

b. DMDM hydantoin

c. imidazolidinyl urea

d. para-aminobenzoic acid

e. quaternium-15

5. Colophony can be found in all of the following trees except:

a. cedars

b. firs

c. junipers

d. maples

e. pines

1. Which of the following is not a component of fragrance mix?

a. abietic acid

b. α-amylcinnamaldehyde

c. geraniol

d. hydroxycitronellal

e. oakmoss

2. A patient is referred for patch testing for suspected allergic contact dermatitis and is found to have positivity to disperse blue dye 106. The patient should avoid all of the following except:

a. black-colored clothing

b. pure acetate clothing

c. pure polyester clothing

d. purple-colored clothing

e. red-colored clothing

3. A patient with a documented contact allergy to ethylenediamine dihydrochloride should avoid all of the following systemic medications except:

a. aminophylline

b. disulfiram

c. hydroxyzine

d. meclizine

e. promethazine

4. Formaldehyde can cross-react with all of the following except:

a. diazolidinyl urea

b. DMDM hydantoin

c. imidazolidinyl urea

d. para-aminobenzoic acid

e. quaternium-15

5. Colophony can be found in all of the following trees except:

a. cedars

b. firs

c. junipers

d. maples

e. pines

Allergic Contact Dermatitis, Part 2

Applications of Lasers in Medical Dermatology

The use of lasers in dermatology has had a major impact on the treatment of many dermatologic conditions. In this column practical applications of lasers in medical dermatology will be discussed to give dermatology residents a broad overview of both established indications and the reasoning behind the usage of lasers in treating these skin conditions. The applications for lasers in aesthetic dermatology are numerous and are constantly being refined and developed; they have been discussed extensively in the literature. Given the vast variety of uses of lasers in dermatology today, a comprehensive review of this topic would likely span several volumes. This article will focus on recent evidence regarding the use of lasers in medical dermatology, specifically laser treatment of selected common dermatoses and cutaneous malignancies.

Laser Treatment of Skin Diseases

Many common dermatoses seen in the dermatologist’s office (eg, discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE], morphea, alopecia) already have an established therapeutic ladder, with most patients responding to either first- or second-line therapies; however, a number of patients present with refractory disease that can be difficult to treat due to either treatment resistance or other contraindications to therapy. With the advent and development of modern lasers, we are now able to target many of these conditions and provide a viable safe treatment option for these patients. Although many physicians may be familiar with the use of the excimer laser in the treatment of psoriasis,1 a long-standing and well-accepted treatment modality for this condition, many novel applications for different types of lasers have been developed.

First, it is important to consider what a laser is able to accomplish to modulate the skin. With ablative lasers such as the CO2 laser, it is possible to destroy superficial layers of the skin (ie, the epidermis). It would stand to reason that this approach would be ideal for treating epidermal processes such as viral warts; in fact, this modality has been used for this indication for more than 3 decades, with the earliest references coming from the podiatric and urologic literature.2,3 Despite conflicting reports of the risk for human papillomavirus aerosolization and subsequent contamination of the treatment area,4,5 CO2 laser therapy has been advocated as a nonsurgical approach to difficult-to-treat cases of viral warts.

On the other hand, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) can target blood vessels because the wavelength corresponds to the absorption spectrum of hemoglobin and penetrates to the level of the dermis, while the pulse duration can be set to be shorter than the thermal relaxation time of a small cutaneous blood vessel.6 In clinical practice, the PDL has been used for the treatment of vascular lesions including hemangiomas, nevus flammeus, and other vascular proliferations.7-9 However, the PDL also can be used to target the vessels in cutaneous inflammatory diseases that feature vascular dilation and/or perivascular inflammation as a prominent feature.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may be difficult to treat, with recalcitrant lesions displaying continued inflammation leading to chronic scarring and dyspigmentation. A small study (N=12) presented the efficacy of the PDL in the treatment of DLE lesions, suggesting that it has good efficacy in treating recalcitrant lesions with significant reduction in the cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index after 6 weeks of treatment and 6 weeks of follow-up (P<.0001) with decreased erythema and scaling.10 It is important to note, however, that scarring, dyspigmentation, and atrophy were not affected, which suggests that early intervention may be optimal to prevent development of these sequelae. More interestingly, a more recent study expounded on this idea and attempted to examine pathophysiologic mechanisms behind this observed improvement. Evaluation of biopsy specimens before and after treatment and immunohistochemistry revealed that PDL treatment of cutaneous DLE lesions led to a decrease in vascular endothelial proteins—intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1—with a coincident reduction in the dermal lymphocytic infiltrate in treated lesions.11 These results offer a somewhat satisfying view on the correlation between the theory and basic science of laser therapy and the subsequent clinical benefits afforded by laser treatment. A case series provided further evidence that PDL or intense pulsed light can ameliorate the cutaneous lesions of DLE in 16 patients in whom all other treatments had failed.12

Several other inflammatory dermatoses can be treated with PDL, though the evidence for most of these conditions is sporadic at best, consisting mostly of case reports and a few case series. Granuloma faciale is one such condition, with evidence of efficacy of the PDL dating back as far as 1999,13 though a more recent case series of 4 patients only showed response in 2 patients.14 Because granuloma faciale features vasculitis as a prominent feature in its pathology, targeting the blood vessels may be helpful, but it is important to remember that there is a complex interplay between multiple factors. For example, treatment with typical fluences used in dermatology can be proinflammatory, leading to tissue damage, necrosis, and posttreatment erythema. However, low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has been shown to downregulate proinflammatory mediators.15 Additionally, the presence of a large burden of inflammatory cells also may alter the effectiveness of the laser. Several case reports also the show effectiveness of both PDL and the CO2 laser in treating lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, especially lupus pernio.16-19 Of these 2 modalities, the use of the CO2 laser for effective remodeling of lupus pernio may be more intuitive; however, it is still important to note that the mechanism of action of several of these laser modalities is unclear with regard to the clinical benefit shown. Morphea and scleroderma also have been treated with laser therapy. It is essential to understand that in many cases, laser therapy may be targeted to treat the precise cutaneous manifestations of disease in each individual patient (eg, CO2 laser to treat disabling contractures and calcinosis cutis,20,21 PDL to treat telangiectases related to morphea22). Again, the most critical consideration is that the treatment modality should align with the cutaneous lesion being targeted.

A relatively recent development in the use of lasers has been LLLT, which refers to the use of lasers below levels where they would cause any thermal effects, thereby limiting tissue damage. Although the technology has existed for decades, there has been a recent flurry of reports extolling the many benefits of LLLT; however, the true physiologic effects of LLLT have yet to be determined, with many studies trying to elucidate its numerous effects on various signaling pathways, cell proliferation, and cellular respiration.23-26 Upon reviewing the literature, the list of cutaneous conditions that are being treated with LLLT is vast, spanning acne, vitiligo, wounds, burns, psoriasis, and alopecia, among others.15 It is important to consider that the definition of LLLT in the literature is rather broad with a wide range of wavelengths, fluences, and power densities. As such, the specific laser settings and protocols may vary considerably among different practitioners and therefore the treatment results also may vary. Nevertheless, many studies have hinted at promising results in the use of LLLT in conditions that may have previously been extremely difficult to treat (eg, alopecia). Earlier trials had demonstrated a faster resolution time in patients with alopecia areata when LLLT was added to a topical regimen27; however, the improvement was modest and lesions tended to improve with or without LLLT. Perhaps more compelling is the use of LLLT in treating androgenetic alopecia, a condition for which a satisfying facile treatment would truly carry great impact. Although physicians should be cautious of studies regarding LLLT and hair regrowth that are conducted by groups who may stand to benefit from producing such a device, the results are nonetheless notable, if only for the relative paucity of other therapeutic approaches toward this condition.28,29 A randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter trial showed significant improvements in median hair thickness and density with LLLT (P=.01 and P=.003, respectively), though global appearance did not change significantly.30

Laser Treatment of Skin Cancer

Lasers also have been used to treat cutaneous malignancies. Although they may be powerful in the treatment of these conditions, this treatment approach must be used with caution. As with any superficial treatment modality for skin cancer, it is difficult to ascertain if a lesion has been completely treated without any residual cancer cells, and therein lies the main caveat of laser treatment. With the use of a modality that causes a cutaneous response that may mask any underlying process, it is important to ensure that there is a reasonable degree of certainty that this treatment can effectively remove a cancerous lesion in its entirety while avoiding the theoretical risk that disturbing underlying vasculature and/or lymphatics may be modulating the ability of a cancer to metastasize. Thankfully, current evidence does not suggest that there are any downsides to laser treatment for malignancies. Clinically, we know that basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) often feature prominent vasculature, with telangiectases being used as a clinical marker to suggest the diagnosis of a BCC. Capitalizing on this aspect of the clinical lesion, PDL has been used to treat BCCs in 2 small studies with a response rate of approximately 75% for small BCCs in both studies.31,32 A recent randomized controlled trial showed significant superiority of PDL as compared to the control (P<.0001) in treatment of BCC, with nearly 80% (44/56) of cases showing histologically proven complete remission at 6-month follow-up.33 Thus, we have some promising data that suggest PDL may be a viable treatment option in BCC, especially in areas that are difficult to treat surgically.

Additionally, a newer treatment approach for BCC capitalizes on the ability of confocal microscopy to provide a feasible, bedside imaging modality to identify tumor margins. Confocal microscopy has been used as a road map to identify where and how to apply the laser treatment, thus allowing for a higher likelihood of complete destruction of the tumor, at least in theory.34 Although the concept of using confocal microscopy to guide laser treatment of skin cancer has been shown in smaller proof-of-concept case series, it remains to be seen if it is not only an efficacious approach that may be widely adopted but also whether it is pragmatic to do so, as the equipment and expertise involved in using confocal microscopy is not trivial.

Finally, lasers also have been used in the treatment of mycosis fungoides (MF), or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been suggested that this modality is an excellent treatment option as a skin-directed therapy for stage IA or IB MFs limited to the acral surfaces or MF palmaris et plantaris.35 The reasoning behind this approach was the effectiveness of narrowband UVB for early-stage MF, with an excimer laser operating at a similar wavelength (308 nm) and offering similar therapeutic benefits while limiting adverse effects to surrounding skin.36 More recently, the excimer laser was applied to a small population of 6 patients, with 3 achieving complete response, 1 with partial response, 1 with stable disease, and 1 with progressive disease. The authors were careful to point out that the excimer laser should not be thought of as a replacement for narrowband UVB in early-stage MF but rather as an adjunctive treatment of specific targeted lesional areas.36

Conclusion

Lasers are an important part of the dermatologist’s treatment arsenal. Although much attention has been focused on laser treatment for aesthetic indications, it is important not to overlook the fact that lasers also can be useful in the treatment of refractory skin diseases, as a first-line treatment in some conditions such as vascular lesions, or as an adjunctive treatment modality. There is a great deal of exciting research that may lead to new indications and a better understanding of how to best use these powerful tools, and the outlook is bright for the use of lasers in dermatology.

1. Bonis B, Kemeny L, Dobozy A, et al. 308 nm UVB excimer laser for psoriasis. Lancet. 1997;350:1522.

2. Fuselier HA Jr, McBurney EI, Brannan W, et al. Treatment of condylomata acuminata with carbon dioxide laser. Urology. 1980;15:265-266.

3. Mueller TJ, Carlson BA, Lindy MP. The use of the carbon dioxide surgical laser for the treatment of verrucae. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1980;70:136-141.

4. Weyandt GH, Tollmann F, Kristen P, et al. Low risk of contamination with human papilloma virus during treatment of condylomata acuminata with multilayer argon plasma coagulation and CO2 laser ablation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:141-144.

5. Ferenczy A, Bergeron C, Richart RM. Human papillomavirus DNA in CO2 laser-generated plume of smoke and its consequences to the surgeon. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:114-118.

6. Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Microvasculature can be selectively damaged using dye lasers: a basic theory and experimental evidence in human skin. Lasers Surg Med. 1981:263-276.

7. Morelli JG, Tan OT, Garden J, et al. Tunable dye laser (577 nm) treatment of port wine stains. Lasers Surg Med. 1986;6:94-99.

8. Reyes BA, Geronemus R. Treatment of port-wine stains during childhood with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1142-1148.

9. Ashinoff R, Geronemus RG. Capillary hemangiomas and treatment with the flash lamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:202-205.

10. Erceg A, Bovenschen HJ, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Efficacy and safety of pulsed dye laser treatment for cutaneous discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:626-632.

11. Diez MT, Boixeda P, Moreno C, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of cutaneous lupus erythematosus after pulsed dye laser treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:971-981.

12. Ekback MP, Troilius A. Laser therapy for refractory discoid lupus erythematosus when everything else has failed. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:260-265.

13. Welsh JH, Schroeder TL, Levy ML. Granuloma faciale in a child successfully treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:351-353.

14. Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

15. Avci P, Gupta A, Sadasivam M, et al. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) in skin: stimulating, healing, restoring. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32:41-52.

16. Roos S, Raulin C, Ockenfels HM, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions with the flashlamp pumped pulsed dye laser: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1139-1140.

17. Cliff S, Felix RH, Singh L, et al. The successful treatment of lupus pernio with the flashlamp pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:49-52.

18. O’Donoghue NB, Barlow RJ. Laser remodelling of nodular nasal lupus pernio. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:27-29.

19. Young HS, Chalmers RJ, Griffiths CE, et al. CO2 laser vaporization for disfiguring lupus pernio. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2002;4:87-90.

20. Kineston D, Kwan JM, Uebelhoer NS, et al. Use of a fractional ablative 10.6-mum carbon dioxide laser in the treatment of a morphea-related contracture. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1148-1150.

21. Chamberlain AJ, Walker NP. Successful palliation and significant remission of cutaneous calcinosis in CREST syndrome with carbon dioxide laser. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:968-970.

22. Ciatti S, Varga J, Greenbaum SS. The 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for the treatment of telangiectases in patients with scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:487-488.

23. Karu TI, Kolyakov SF. Exact action spectra for cellular responses relevant to phototherapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23:355-361.

24. Greco M, Guida G, Perlino E, et al. Increase in RNA and protein synthesis by mitochondria irradiated with helium-neon laser. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:1428-1434.

25. Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS. Photobiological modulation of cell attachment via cytochrome c oxidase. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:211-216.

26. Wong-Riley MT, Liang HL, Eells JT, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4761-4771.

27. Yamazaki M, Miura Y, Tsuboi R, et al. Linear polarized infrared irradiation using Super Lizer is an effective treatment for multiple-type alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:738-740.

28. Leavitt M, Charles G, Heyman E, et al. HairMax LaserComb laser phototherapy device in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled, multicentre trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:283-292.

29. Munck A, Gavazzoni MF, Trueb RM. Use of low-level laser therapy as monotherapy or concomitant therapy for male and female androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:45-49.

30. Kim H, Choi JW, Kim JY, et al. Low-level light therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled multicenter trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1177-1183.

31. Minars N, Blyumin-Karasik M. Treatment of basal cell carcinomas with pulsed dye laser: a case series [published online ahead of print December 13, 2012]. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:286480.

32. Jalian HR, Avram MM, Stankiewicz KJ, et al. Combined 585 nm pulsed-dye and 1,064 nm Nd:YAG lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:1-7.

33. Karsai S, Friedl H, Buhck H, et al. The role of the 595-nm pulsed dye laser in treating superficial basal cell carcinoma: outcome of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial [published online ahead of print July 12, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13266.

34. Chen CS, Sierra H, Cordova M, et al. Confocal microscopy-guided laser ablation for superficial and early nodular Basal cell carcinoma: a promising surgical alternative for superficial skin cancers. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:994-998.

35. Jin SP, Jeon YK, Cho KH, et al. Excimer laser therapy (308 nm) for mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris: a skin-directed and anatomically feasible treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:651-653.

36. Deaver D, Cauthen A, Cohen G, et al. Excimer laser in the treatment of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:1058-1060.

The use of lasers in dermatology has had a major impact on the treatment of many dermatologic conditions. In this column practical applications of lasers in medical dermatology will be discussed to give dermatology residents a broad overview of both established indications and the reasoning behind the usage of lasers in treating these skin conditions. The applications for lasers in aesthetic dermatology are numerous and are constantly being refined and developed; they have been discussed extensively in the literature. Given the vast variety of uses of lasers in dermatology today, a comprehensive review of this topic would likely span several volumes. This article will focus on recent evidence regarding the use of lasers in medical dermatology, specifically laser treatment of selected common dermatoses and cutaneous malignancies.

Laser Treatment of Skin Diseases

Many common dermatoses seen in the dermatologist’s office (eg, discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE], morphea, alopecia) already have an established therapeutic ladder, with most patients responding to either first- or second-line therapies; however, a number of patients present with refractory disease that can be difficult to treat due to either treatment resistance or other contraindications to therapy. With the advent and development of modern lasers, we are now able to target many of these conditions and provide a viable safe treatment option for these patients. Although many physicians may be familiar with the use of the excimer laser in the treatment of psoriasis,1 a long-standing and well-accepted treatment modality for this condition, many novel applications for different types of lasers have been developed.

First, it is important to consider what a laser is able to accomplish to modulate the skin. With ablative lasers such as the CO2 laser, it is possible to destroy superficial layers of the skin (ie, the epidermis). It would stand to reason that this approach would be ideal for treating epidermal processes such as viral warts; in fact, this modality has been used for this indication for more than 3 decades, with the earliest references coming from the podiatric and urologic literature.2,3 Despite conflicting reports of the risk for human papillomavirus aerosolization and subsequent contamination of the treatment area,4,5 CO2 laser therapy has been advocated as a nonsurgical approach to difficult-to-treat cases of viral warts.

On the other hand, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) can target blood vessels because the wavelength corresponds to the absorption spectrum of hemoglobin and penetrates to the level of the dermis, while the pulse duration can be set to be shorter than the thermal relaxation time of a small cutaneous blood vessel.6 In clinical practice, the PDL has been used for the treatment of vascular lesions including hemangiomas, nevus flammeus, and other vascular proliferations.7-9 However, the PDL also can be used to target the vessels in cutaneous inflammatory diseases that feature vascular dilation and/or perivascular inflammation as a prominent feature.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may be difficult to treat, with recalcitrant lesions displaying continued inflammation leading to chronic scarring and dyspigmentation. A small study (N=12) presented the efficacy of the PDL in the treatment of DLE lesions, suggesting that it has good efficacy in treating recalcitrant lesions with significant reduction in the cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index after 6 weeks of treatment and 6 weeks of follow-up (P<.0001) with decreased erythema and scaling.10 It is important to note, however, that scarring, dyspigmentation, and atrophy were not affected, which suggests that early intervention may be optimal to prevent development of these sequelae. More interestingly, a more recent study expounded on this idea and attempted to examine pathophysiologic mechanisms behind this observed improvement. Evaluation of biopsy specimens before and after treatment and immunohistochemistry revealed that PDL treatment of cutaneous DLE lesions led to a decrease in vascular endothelial proteins—intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1—with a coincident reduction in the dermal lymphocytic infiltrate in treated lesions.11 These results offer a somewhat satisfying view on the correlation between the theory and basic science of laser therapy and the subsequent clinical benefits afforded by laser treatment. A case series provided further evidence that PDL or intense pulsed light can ameliorate the cutaneous lesions of DLE in 16 patients in whom all other treatments had failed.12

Several other inflammatory dermatoses can be treated with PDL, though the evidence for most of these conditions is sporadic at best, consisting mostly of case reports and a few case series. Granuloma faciale is one such condition, with evidence of efficacy of the PDL dating back as far as 1999,13 though a more recent case series of 4 patients only showed response in 2 patients.14 Because granuloma faciale features vasculitis as a prominent feature in its pathology, targeting the blood vessels may be helpful, but it is important to remember that there is a complex interplay between multiple factors. For example, treatment with typical fluences used in dermatology can be proinflammatory, leading to tissue damage, necrosis, and posttreatment erythema. However, low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has been shown to downregulate proinflammatory mediators.15 Additionally, the presence of a large burden of inflammatory cells also may alter the effectiveness of the laser. Several case reports also the show effectiveness of both PDL and the CO2 laser in treating lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, especially lupus pernio.16-19 Of these 2 modalities, the use of the CO2 laser for effective remodeling of lupus pernio may be more intuitive; however, it is still important to note that the mechanism of action of several of these laser modalities is unclear with regard to the clinical benefit shown. Morphea and scleroderma also have been treated with laser therapy. It is essential to understand that in many cases, laser therapy may be targeted to treat the precise cutaneous manifestations of disease in each individual patient (eg, CO2 laser to treat disabling contractures and calcinosis cutis,20,21 PDL to treat telangiectases related to morphea22). Again, the most critical consideration is that the treatment modality should align with the cutaneous lesion being targeted.

A relatively recent development in the use of lasers has been LLLT, which refers to the use of lasers below levels where they would cause any thermal effects, thereby limiting tissue damage. Although the technology has existed for decades, there has been a recent flurry of reports extolling the many benefits of LLLT; however, the true physiologic effects of LLLT have yet to be determined, with many studies trying to elucidate its numerous effects on various signaling pathways, cell proliferation, and cellular respiration.23-26 Upon reviewing the literature, the list of cutaneous conditions that are being treated with LLLT is vast, spanning acne, vitiligo, wounds, burns, psoriasis, and alopecia, among others.15 It is important to consider that the definition of LLLT in the literature is rather broad with a wide range of wavelengths, fluences, and power densities. As such, the specific laser settings and protocols may vary considerably among different practitioners and therefore the treatment results also may vary. Nevertheless, many studies have hinted at promising results in the use of LLLT in conditions that may have previously been extremely difficult to treat (eg, alopecia). Earlier trials had demonstrated a faster resolution time in patients with alopecia areata when LLLT was added to a topical regimen27; however, the improvement was modest and lesions tended to improve with or without LLLT. Perhaps more compelling is the use of LLLT in treating androgenetic alopecia, a condition for which a satisfying facile treatment would truly carry great impact. Although physicians should be cautious of studies regarding LLLT and hair regrowth that are conducted by groups who may stand to benefit from producing such a device, the results are nonetheless notable, if only for the relative paucity of other therapeutic approaches toward this condition.28,29 A randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter trial showed significant improvements in median hair thickness and density with LLLT (P=.01 and P=.003, respectively), though global appearance did not change significantly.30

Laser Treatment of Skin Cancer

Lasers also have been used to treat cutaneous malignancies. Although they may be powerful in the treatment of these conditions, this treatment approach must be used with caution. As with any superficial treatment modality for skin cancer, it is difficult to ascertain if a lesion has been completely treated without any residual cancer cells, and therein lies the main caveat of laser treatment. With the use of a modality that causes a cutaneous response that may mask any underlying process, it is important to ensure that there is a reasonable degree of certainty that this treatment can effectively remove a cancerous lesion in its entirety while avoiding the theoretical risk that disturbing underlying vasculature and/or lymphatics may be modulating the ability of a cancer to metastasize. Thankfully, current evidence does not suggest that there are any downsides to laser treatment for malignancies. Clinically, we know that basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) often feature prominent vasculature, with telangiectases being used as a clinical marker to suggest the diagnosis of a BCC. Capitalizing on this aspect of the clinical lesion, PDL has been used to treat BCCs in 2 small studies with a response rate of approximately 75% for small BCCs in both studies.31,32 A recent randomized controlled trial showed significant superiority of PDL as compared to the control (P<.0001) in treatment of BCC, with nearly 80% (44/56) of cases showing histologically proven complete remission at 6-month follow-up.33 Thus, we have some promising data that suggest PDL may be a viable treatment option in BCC, especially in areas that are difficult to treat surgically.

Additionally, a newer treatment approach for BCC capitalizes on the ability of confocal microscopy to provide a feasible, bedside imaging modality to identify tumor margins. Confocal microscopy has been used as a road map to identify where and how to apply the laser treatment, thus allowing for a higher likelihood of complete destruction of the tumor, at least in theory.34 Although the concept of using confocal microscopy to guide laser treatment of skin cancer has been shown in smaller proof-of-concept case series, it remains to be seen if it is not only an efficacious approach that may be widely adopted but also whether it is pragmatic to do so, as the equipment and expertise involved in using confocal microscopy is not trivial.

Finally, lasers also have been used in the treatment of mycosis fungoides (MF), or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been suggested that this modality is an excellent treatment option as a skin-directed therapy for stage IA or IB MFs limited to the acral surfaces or MF palmaris et plantaris.35 The reasoning behind this approach was the effectiveness of narrowband UVB for early-stage MF, with an excimer laser operating at a similar wavelength (308 nm) and offering similar therapeutic benefits while limiting adverse effects to surrounding skin.36 More recently, the excimer laser was applied to a small population of 6 patients, with 3 achieving complete response, 1 with partial response, 1 with stable disease, and 1 with progressive disease. The authors were careful to point out that the excimer laser should not be thought of as a replacement for narrowband UVB in early-stage MF but rather as an adjunctive treatment of specific targeted lesional areas.36

Conclusion

Lasers are an important part of the dermatologist’s treatment arsenal. Although much attention has been focused on laser treatment for aesthetic indications, it is important not to overlook the fact that lasers also can be useful in the treatment of refractory skin diseases, as a first-line treatment in some conditions such as vascular lesions, or as an adjunctive treatment modality. There is a great deal of exciting research that may lead to new indications and a better understanding of how to best use these powerful tools, and the outlook is bright for the use of lasers in dermatology.

The use of lasers in dermatology has had a major impact on the treatment of many dermatologic conditions. In this column practical applications of lasers in medical dermatology will be discussed to give dermatology residents a broad overview of both established indications and the reasoning behind the usage of lasers in treating these skin conditions. The applications for lasers in aesthetic dermatology are numerous and are constantly being refined and developed; they have been discussed extensively in the literature. Given the vast variety of uses of lasers in dermatology today, a comprehensive review of this topic would likely span several volumes. This article will focus on recent evidence regarding the use of lasers in medical dermatology, specifically laser treatment of selected common dermatoses and cutaneous malignancies.

Laser Treatment of Skin Diseases

Many common dermatoses seen in the dermatologist’s office (eg, discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE], morphea, alopecia) already have an established therapeutic ladder, with most patients responding to either first- or second-line therapies; however, a number of patients present with refractory disease that can be difficult to treat due to either treatment resistance or other contraindications to therapy. With the advent and development of modern lasers, we are now able to target many of these conditions and provide a viable safe treatment option for these patients. Although many physicians may be familiar with the use of the excimer laser in the treatment of psoriasis,1 a long-standing and well-accepted treatment modality for this condition, many novel applications for different types of lasers have been developed.

First, it is important to consider what a laser is able to accomplish to modulate the skin. With ablative lasers such as the CO2 laser, it is possible to destroy superficial layers of the skin (ie, the epidermis). It would stand to reason that this approach would be ideal for treating epidermal processes such as viral warts; in fact, this modality has been used for this indication for more than 3 decades, with the earliest references coming from the podiatric and urologic literature.2,3 Despite conflicting reports of the risk for human papillomavirus aerosolization and subsequent contamination of the treatment area,4,5 CO2 laser therapy has been advocated as a nonsurgical approach to difficult-to-treat cases of viral warts.

On the other hand, the pulsed dye laser (PDL) can target blood vessels because the wavelength corresponds to the absorption spectrum of hemoglobin and penetrates to the level of the dermis, while the pulse duration can be set to be shorter than the thermal relaxation time of a small cutaneous blood vessel.6 In clinical practice, the PDL has been used for the treatment of vascular lesions including hemangiomas, nevus flammeus, and other vascular proliferations.7-9 However, the PDL also can be used to target the vessels in cutaneous inflammatory diseases that feature vascular dilation and/or perivascular inflammation as a prominent feature.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may be difficult to treat, with recalcitrant lesions displaying continued inflammation leading to chronic scarring and dyspigmentation. A small study (N=12) presented the efficacy of the PDL in the treatment of DLE lesions, suggesting that it has good efficacy in treating recalcitrant lesions with significant reduction in the cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index after 6 weeks of treatment and 6 weeks of follow-up (P<.0001) with decreased erythema and scaling.10 It is important to note, however, that scarring, dyspigmentation, and atrophy were not affected, which suggests that early intervention may be optimal to prevent development of these sequelae. More interestingly, a more recent study expounded on this idea and attempted to examine pathophysiologic mechanisms behind this observed improvement. Evaluation of biopsy specimens before and after treatment and immunohistochemistry revealed that PDL treatment of cutaneous DLE lesions led to a decrease in vascular endothelial proteins—intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1—with a coincident reduction in the dermal lymphocytic infiltrate in treated lesions.11 These results offer a somewhat satisfying view on the correlation between the theory and basic science of laser therapy and the subsequent clinical benefits afforded by laser treatment. A case series provided further evidence that PDL or intense pulsed light can ameliorate the cutaneous lesions of DLE in 16 patients in whom all other treatments had failed.12

Several other inflammatory dermatoses can be treated with PDL, though the evidence for most of these conditions is sporadic at best, consisting mostly of case reports and a few case series. Granuloma faciale is one such condition, with evidence of efficacy of the PDL dating back as far as 1999,13 though a more recent case series of 4 patients only showed response in 2 patients.14 Because granuloma faciale features vasculitis as a prominent feature in its pathology, targeting the blood vessels may be helpful, but it is important to remember that there is a complex interplay between multiple factors. For example, treatment with typical fluences used in dermatology can be proinflammatory, leading to tissue damage, necrosis, and posttreatment erythema. However, low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has been shown to downregulate proinflammatory mediators.15 Additionally, the presence of a large burden of inflammatory cells also may alter the effectiveness of the laser. Several case reports also the show effectiveness of both PDL and the CO2 laser in treating lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, especially lupus pernio.16-19 Of these 2 modalities, the use of the CO2 laser for effective remodeling of lupus pernio may be more intuitive; however, it is still important to note that the mechanism of action of several of these laser modalities is unclear with regard to the clinical benefit shown. Morphea and scleroderma also have been treated with laser therapy. It is essential to understand that in many cases, laser therapy may be targeted to treat the precise cutaneous manifestations of disease in each individual patient (eg, CO2 laser to treat disabling contractures and calcinosis cutis,20,21 PDL to treat telangiectases related to morphea22). Again, the most critical consideration is that the treatment modality should align with the cutaneous lesion being targeted.

A relatively recent development in the use of lasers has been LLLT, which refers to the use of lasers below levels where they would cause any thermal effects, thereby limiting tissue damage. Although the technology has existed for decades, there has been a recent flurry of reports extolling the many benefits of LLLT; however, the true physiologic effects of LLLT have yet to be determined, with many studies trying to elucidate its numerous effects on various signaling pathways, cell proliferation, and cellular respiration.23-26 Upon reviewing the literature, the list of cutaneous conditions that are being treated with LLLT is vast, spanning acne, vitiligo, wounds, burns, psoriasis, and alopecia, among others.15 It is important to consider that the definition of LLLT in the literature is rather broad with a wide range of wavelengths, fluences, and power densities. As such, the specific laser settings and protocols may vary considerably among different practitioners and therefore the treatment results also may vary. Nevertheless, many studies have hinted at promising results in the use of LLLT in conditions that may have previously been extremely difficult to treat (eg, alopecia). Earlier trials had demonstrated a faster resolution time in patients with alopecia areata when LLLT was added to a topical regimen27; however, the improvement was modest and lesions tended to improve with or without LLLT. Perhaps more compelling is the use of LLLT in treating androgenetic alopecia, a condition for which a satisfying facile treatment would truly carry great impact. Although physicians should be cautious of studies regarding LLLT and hair regrowth that are conducted by groups who may stand to benefit from producing such a device, the results are nonetheless notable, if only for the relative paucity of other therapeutic approaches toward this condition.28,29 A randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter trial showed significant improvements in median hair thickness and density with LLLT (P=.01 and P=.003, respectively), though global appearance did not change significantly.30

Laser Treatment of Skin Cancer

Lasers also have been used to treat cutaneous malignancies. Although they may be powerful in the treatment of these conditions, this treatment approach must be used with caution. As with any superficial treatment modality for skin cancer, it is difficult to ascertain if a lesion has been completely treated without any residual cancer cells, and therein lies the main caveat of laser treatment. With the use of a modality that causes a cutaneous response that may mask any underlying process, it is important to ensure that there is a reasonable degree of certainty that this treatment can effectively remove a cancerous lesion in its entirety while avoiding the theoretical risk that disturbing underlying vasculature and/or lymphatics may be modulating the ability of a cancer to metastasize. Thankfully, current evidence does not suggest that there are any downsides to laser treatment for malignancies. Clinically, we know that basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) often feature prominent vasculature, with telangiectases being used as a clinical marker to suggest the diagnosis of a BCC. Capitalizing on this aspect of the clinical lesion, PDL has been used to treat BCCs in 2 small studies with a response rate of approximately 75% for small BCCs in both studies.31,32 A recent randomized controlled trial showed significant superiority of PDL as compared to the control (P<.0001) in treatment of BCC, with nearly 80% (44/56) of cases showing histologically proven complete remission at 6-month follow-up.33 Thus, we have some promising data that suggest PDL may be a viable treatment option in BCC, especially in areas that are difficult to treat surgically.

Additionally, a newer treatment approach for BCC capitalizes on the ability of confocal microscopy to provide a feasible, bedside imaging modality to identify tumor margins. Confocal microscopy has been used as a road map to identify where and how to apply the laser treatment, thus allowing for a higher likelihood of complete destruction of the tumor, at least in theory.34 Although the concept of using confocal microscopy to guide laser treatment of skin cancer has been shown in smaller proof-of-concept case series, it remains to be seen if it is not only an efficacious approach that may be widely adopted but also whether it is pragmatic to do so, as the equipment and expertise involved in using confocal microscopy is not trivial.

Finally, lasers also have been used in the treatment of mycosis fungoides (MF), or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It has been suggested that this modality is an excellent treatment option as a skin-directed therapy for stage IA or IB MFs limited to the acral surfaces or MF palmaris et plantaris.35 The reasoning behind this approach was the effectiveness of narrowband UVB for early-stage MF, with an excimer laser operating at a similar wavelength (308 nm) and offering similar therapeutic benefits while limiting adverse effects to surrounding skin.36 More recently, the excimer laser was applied to a small population of 6 patients, with 3 achieving complete response, 1 with partial response, 1 with stable disease, and 1 with progressive disease. The authors were careful to point out that the excimer laser should not be thought of as a replacement for narrowband UVB in early-stage MF but rather as an adjunctive treatment of specific targeted lesional areas.36

Conclusion

Lasers are an important part of the dermatologist’s treatment arsenal. Although much attention has been focused on laser treatment for aesthetic indications, it is important not to overlook the fact that lasers also can be useful in the treatment of refractory skin diseases, as a first-line treatment in some conditions such as vascular lesions, or as an adjunctive treatment modality. There is a great deal of exciting research that may lead to new indications and a better understanding of how to best use these powerful tools, and the outlook is bright for the use of lasers in dermatology.

1. Bonis B, Kemeny L, Dobozy A, et al. 308 nm UVB excimer laser for psoriasis. Lancet. 1997;350:1522.

2. Fuselier HA Jr, McBurney EI, Brannan W, et al. Treatment of condylomata acuminata with carbon dioxide laser. Urology. 1980;15:265-266.

3. Mueller TJ, Carlson BA, Lindy MP. The use of the carbon dioxide surgical laser for the treatment of verrucae. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1980;70:136-141.

4. Weyandt GH, Tollmann F, Kristen P, et al. Low risk of contamination with human papilloma virus during treatment of condylomata acuminata with multilayer argon plasma coagulation and CO2 laser ablation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:141-144.

5. Ferenczy A, Bergeron C, Richart RM. Human papillomavirus DNA in CO2 laser-generated plume of smoke and its consequences to the surgeon. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:114-118.

6. Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Microvasculature can be selectively damaged using dye lasers: a basic theory and experimental evidence in human skin. Lasers Surg Med. 1981:263-276.

7. Morelli JG, Tan OT, Garden J, et al. Tunable dye laser (577 nm) treatment of port wine stains. Lasers Surg Med. 1986;6:94-99.

8. Reyes BA, Geronemus R. Treatment of port-wine stains during childhood with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1142-1148.

9. Ashinoff R, Geronemus RG. Capillary hemangiomas and treatment with the flash lamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:202-205.

10. Erceg A, Bovenschen HJ, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Efficacy and safety of pulsed dye laser treatment for cutaneous discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:626-632.

11. Diez MT, Boixeda P, Moreno C, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of cutaneous lupus erythematosus after pulsed dye laser treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:971-981.

12. Ekback MP, Troilius A. Laser therapy for refractory discoid lupus erythematosus when everything else has failed. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:260-265.

13. Welsh JH, Schroeder TL, Levy ML. Granuloma faciale in a child successfully treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:351-353.

14. Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

15. Avci P, Gupta A, Sadasivam M, et al. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) in skin: stimulating, healing, restoring. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32:41-52.

16. Roos S, Raulin C, Ockenfels HM, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions with the flashlamp pumped pulsed dye laser: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1139-1140.

17. Cliff S, Felix RH, Singh L, et al. The successful treatment of lupus pernio with the flashlamp pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:49-52.

18. O’Donoghue NB, Barlow RJ. Laser remodelling of nodular nasal lupus pernio. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:27-29.

19. Young HS, Chalmers RJ, Griffiths CE, et al. CO2 laser vaporization for disfiguring lupus pernio. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2002;4:87-90.

20. Kineston D, Kwan JM, Uebelhoer NS, et al. Use of a fractional ablative 10.6-mum carbon dioxide laser in the treatment of a morphea-related contracture. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1148-1150.

21. Chamberlain AJ, Walker NP. Successful palliation and significant remission of cutaneous calcinosis in CREST syndrome with carbon dioxide laser. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:968-970.

22. Ciatti S, Varga J, Greenbaum SS. The 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for the treatment of telangiectases in patients with scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:487-488.

23. Karu TI, Kolyakov SF. Exact action spectra for cellular responses relevant to phototherapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23:355-361.

24. Greco M, Guida G, Perlino E, et al. Increase in RNA and protein synthesis by mitochondria irradiated with helium-neon laser. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:1428-1434.

25. Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS. Photobiological modulation of cell attachment via cytochrome c oxidase. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:211-216.

26. Wong-Riley MT, Liang HL, Eells JT, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4761-4771.

27. Yamazaki M, Miura Y, Tsuboi R, et al. Linear polarized infrared irradiation using Super Lizer is an effective treatment for multiple-type alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:738-740.

28. Leavitt M, Charles G, Heyman E, et al. HairMax LaserComb laser phototherapy device in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled, multicentre trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:283-292.

29. Munck A, Gavazzoni MF, Trueb RM. Use of low-level laser therapy as monotherapy or concomitant therapy for male and female androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:45-49.

30. Kim H, Choi JW, Kim JY, et al. Low-level light therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled multicenter trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1177-1183.

31. Minars N, Blyumin-Karasik M. Treatment of basal cell carcinomas with pulsed dye laser: a case series [published online ahead of print December 13, 2012]. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:286480.

32. Jalian HR, Avram MM, Stankiewicz KJ, et al. Combined 585 nm pulsed-dye and 1,064 nm Nd:YAG lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:1-7.

33. Karsai S, Friedl H, Buhck H, et al. The role of the 595-nm pulsed dye laser in treating superficial basal cell carcinoma: outcome of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial [published online ahead of print July 12, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13266.

34. Chen CS, Sierra H, Cordova M, et al. Confocal microscopy-guided laser ablation for superficial and early nodular Basal cell carcinoma: a promising surgical alternative for superficial skin cancers. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:994-998.

35. Jin SP, Jeon YK, Cho KH, et al. Excimer laser therapy (308 nm) for mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris: a skin-directed and anatomically feasible treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:651-653.

36. Deaver D, Cauthen A, Cohen G, et al. Excimer laser in the treatment of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:1058-1060.

1. Bonis B, Kemeny L, Dobozy A, et al. 308 nm UVB excimer laser for psoriasis. Lancet. 1997;350:1522.

2. Fuselier HA Jr, McBurney EI, Brannan W, et al. Treatment of condylomata acuminata with carbon dioxide laser. Urology. 1980;15:265-266.

3. Mueller TJ, Carlson BA, Lindy MP. The use of the carbon dioxide surgical laser for the treatment of verrucae. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1980;70:136-141.

4. Weyandt GH, Tollmann F, Kristen P, et al. Low risk of contamination with human papilloma virus during treatment of condylomata acuminata with multilayer argon plasma coagulation and CO2 laser ablation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:141-144.

5. Ferenczy A, Bergeron C, Richart RM. Human papillomavirus DNA in CO2 laser-generated plume of smoke and its consequences to the surgeon. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:114-118.

6. Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Microvasculature can be selectively damaged using dye lasers: a basic theory and experimental evidence in human skin. Lasers Surg Med. 1981:263-276.

7. Morelli JG, Tan OT, Garden J, et al. Tunable dye laser (577 nm) treatment of port wine stains. Lasers Surg Med. 1986;6:94-99.

8. Reyes BA, Geronemus R. Treatment of port-wine stains during childhood with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1142-1148.

9. Ashinoff R, Geronemus RG. Capillary hemangiomas and treatment with the flash lamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:202-205.

10. Erceg A, Bovenschen HJ, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Efficacy and safety of pulsed dye laser treatment for cutaneous discoid lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:626-632.

11. Diez MT, Boixeda P, Moreno C, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of cutaneous lupus erythematosus after pulsed dye laser treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:971-981.

12. Ekback MP, Troilius A. Laser therapy for refractory discoid lupus erythematosus when everything else has failed. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:260-265.

13. Welsh JH, Schroeder TL, Levy ML. Granuloma faciale in a child successfully treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:351-353.

14. Cheung ST, Lanigan SW. Granuloma faciale treated with the pulsed-dye laser: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:373-375.

15. Avci P, Gupta A, Sadasivam M, et al. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) in skin: stimulating, healing, restoring. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2013;32:41-52.

16. Roos S, Raulin C, Ockenfels HM, et al. Successful treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions with the flashlamp pumped pulsed dye laser: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1139-1140.

17. Cliff S, Felix RH, Singh L, et al. The successful treatment of lupus pernio with the flashlamp pulsed dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999;1:49-52.

18. O’Donoghue NB, Barlow RJ. Laser remodelling of nodular nasal lupus pernio. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:27-29.

19. Young HS, Chalmers RJ, Griffiths CE, et al. CO2 laser vaporization for disfiguring lupus pernio. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2002;4:87-90.

20. Kineston D, Kwan JM, Uebelhoer NS, et al. Use of a fractional ablative 10.6-mum carbon dioxide laser in the treatment of a morphea-related contracture. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1148-1150.

21. Chamberlain AJ, Walker NP. Successful palliation and significant remission of cutaneous calcinosis in CREST syndrome with carbon dioxide laser. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:968-970.

22. Ciatti S, Varga J, Greenbaum SS. The 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for the treatment of telangiectases in patients with scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:487-488.

23. Karu TI, Kolyakov SF. Exact action spectra for cellular responses relevant to phototherapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23:355-361.

24. Greco M, Guida G, Perlino E, et al. Increase in RNA and protein synthesis by mitochondria irradiated with helium-neon laser. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:1428-1434.

25. Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS. Photobiological modulation of cell attachment via cytochrome c oxidase. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:211-216.

26. Wong-Riley MT, Liang HL, Eells JT, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4761-4771.

27. Yamazaki M, Miura Y, Tsuboi R, et al. Linear polarized infrared irradiation using Super Lizer is an effective treatment for multiple-type alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:738-740.

28. Leavitt M, Charles G, Heyman E, et al. HairMax LaserComb laser phototherapy device in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled, multicentre trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:283-292.

29. Munck A, Gavazzoni MF, Trueb RM. Use of low-level laser therapy as monotherapy or concomitant therapy for male and female androgenetic alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:45-49.

30. Kim H, Choi JW, Kim JY, et al. Low-level light therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled multicenter trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1177-1183.

31. Minars N, Blyumin-Karasik M. Treatment of basal cell carcinomas with pulsed dye laser: a case series [published online ahead of print December 13, 2012]. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:286480.

32. Jalian HR, Avram MM, Stankiewicz KJ, et al. Combined 585 nm pulsed-dye and 1,064 nm Nd:YAG lasers for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46:1-7.

33. Karsai S, Friedl H, Buhck H, et al. The role of the 595-nm pulsed dye laser in treating superficial basal cell carcinoma: outcome of a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial [published online ahead of print July 12, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13266.

34. Chen CS, Sierra H, Cordova M, et al. Confocal microscopy-guided laser ablation for superficial and early nodular Basal cell carcinoma: a promising surgical alternative for superficial skin cancers. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:994-998.

35. Jin SP, Jeon YK, Cho KH, et al. Excimer laser therapy (308 nm) for mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris: a skin-directed and anatomically feasible treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:651-653.

36. Deaver D, Cauthen A, Cohen G, et al. Excimer laser in the treatment of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:1058-1060.

Sulfur Spring Dermatitis

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

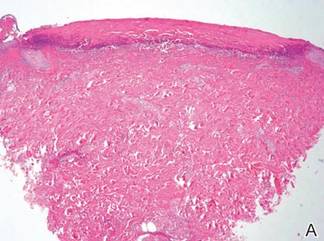

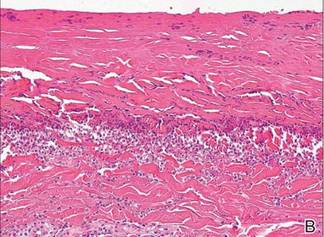

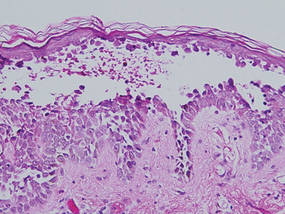

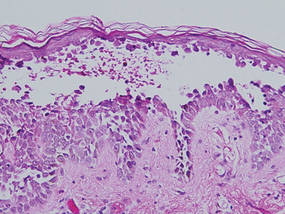

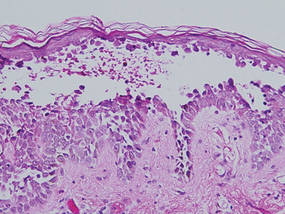

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.

2. Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:132-140.

3. Leslie KS, Millington GW, Levell NJ. Sulphur and skin: from Satan to Saddam! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:94-98.

4. Millikan LE. Unapproved treatments or indications in dermatology: physical therapy including balneotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:125-129.

5. Nirei H, Furuno K, Kusuda T. Medical geology in Japan. In: Selinus O, Finkelman RB, Centeno JA, eds. Medical Geology: A Regional Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:329-354.

6. Liu CM, Song SR, Chen YL, et al. Characteristics and origins of hot springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in northern Taiwan. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci. 2011;22:475-489.

7. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

8. Weedon D. Reaction to physical agents. In: Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health; 2010:525-540.

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

Sulfur spring dermatitis is characterized by multiple punched-out erosions and pits. In prior case reports, patients often presented with painful swollen lesions that developed within 24 hours of bathing in hot sulfur springs.1 Because spa therapy and thermal spring baths are common in modern society, dermatologists should be aware of sulfur spring dermatitis as a potential adverse effect.

Case Report

A healthy 65-year-old man presented with painful skin lesions on the legs that developed after bathing for 25 minutes in a hot sulfur spring 1 day prior. The patient had no history of dermatologic disease. He reported a 10-year history of bathing in a hot sulfur spring for 20 minutes every 3 days in the winter. This time, he bathed 5 minutes longer than usual. No skin condition was noted prior to bathing, but he reported feeling a tickling sensation and scratching the legs while he was immersed in the water. One hour after bathing, he noted confluent, punched-out, round ulcers with peripheral erythema on the thighs and shins (Figure 1).

|

|

A skin biopsy revealed sharply demarcated, homogeneous coagulation necrosis of the epidermis. Many neutrophils were present under the necrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and acid-fast stains were negative for infectious organisms, and a skin tissue culture yielded negative results. Intensive wound care was started with nitrofurazone ointment 0.2%. The ulcers healed gradually in the following months with scar formation and hyperpigmentation.

Comment

Thermal sulfur baths are a form of balneotherapy promoted in many cultures for improvement of skin conditions; however, certain uncommon skin problems may occur after bathing in hot sulfur springs.2 In particular, sulfur spring dermatitis is a potential adverse effect.

Thermal sulfur water is known to exert anti-inflammatory, keratoplastic, and antipruriginous effects. As a result, it often is used in many cultures as an alternative treatment of various skin conditions.2-4 Moreover, thermal sulfur baths are popular in northeastern Asian countries for their effects on mental health.5 Hot springs in northern Taiwan, which contain large amounts of hydrogen sulfide, sulfate, and sulfur differ from other thermal springs in that they are rather acidic in nature and release geothermal energy from volcanic activity.6 In addition to hot sulfur springs, there are neutral salt and CO2 springs in Taiwan.5 However, spring dermatitis has only been associated with bathing in hot sulfur springs due to high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide that break down keratin and cause dissolution of the stratum corneum.7

The incidence of sulfur spring dermatitis is unknown. Although the largest known case series reported 44 cases occurring within a decade in Taiwan,1 it is rarely seen in our daily practice. Previously reported cases of sulfur spring dermatitis noted clinical findings of swelling of the affected area followed by punched-out erosions with surrounding erythema. Most lesions gradually healed with dry brownish crusts. A patch test with sulfur spring water and sulfur compounds showed negative results; therefore, the mechanism is unlikely to be allergic reaction.1 The clinical differential diagnosis includes factitious ulcers as well as viral and fungal infections. A tissue culture should be performed to exclude infectious conditions.

This characteristic skin disease does not present in all individuals after bathing in hot sulfur springs. Lesions may present anywhere on the body with a predilection for skin folds, including the penis and scrotum. Preexisting skin conditions such as pruritus and xerosis are considered to be contributing factors. The possible etiology of sulfur spring dermatitis may be acid irritation from the unstable amount of soluble sulfur in the water, which is enhanced by the heat.1 In our patient, no prior skin disease was noted, but he scratched the skin on the thighs while bathing, which may have contributed to the development of lesions in this area rather than in the skin folds.

The skin biopsy specimen demonstrated epidermal coagulation necrosis, mild superficial dermal damage, and preservation of the pilosebaceous appendages. The ulcers were painful during healing and resolved with scarring and hyperpigmentation. The histopathologic findings and clinical course in our patient were similar to cases of superficial second-degree burns.8 It is possible that the keratoplastic effect of sulfur at high concentrations along with thermal water caused the skin condition.

Conclusion

Individuals who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of potential adverse effects such as sulfur spring dermatitis, especially those with preexisting skin disorders.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.

2. Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:132-140.

3. Leslie KS, Millington GW, Levell NJ. Sulphur and skin: from Satan to Saddam! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:94-98.

4. Millikan LE. Unapproved treatments or indications in dermatology: physical therapy including balneotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:125-129.

5. Nirei H, Furuno K, Kusuda T. Medical geology in Japan. In: Selinus O, Finkelman RB, Centeno JA, eds. Medical Geology: A Regional Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:329-354.

6. Liu CM, Song SR, Chen YL, et al. Characteristics and origins of hot springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in northern Taiwan. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci. 2011;22:475-489.

7. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

8. Weedon D. Reaction to physical agents. In: Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health; 2010:525-540.

1. Sun CC, Sue MS. Sulfur spring dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:31-34.

2. Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:132-140.

3. Leslie KS, Millington GW, Levell NJ. Sulphur and skin: from Satan to Saddam! J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:94-98.

4. Millikan LE. Unapproved treatments or indications in dermatology: physical therapy including balneotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:125-129.

5. Nirei H, Furuno K, Kusuda T. Medical geology in Japan. In: Selinus O, Finkelman RB, Centeno JA, eds. Medical Geology: A Regional Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:329-354.

6. Liu CM, Song SR, Chen YL, et al. Characteristics and origins of hot springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in northern Taiwan. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci. 2011;22:475-489.

7. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM. Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:553-558.

8. Weedon D. Reaction to physical agents. In: Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health; 2010:525-540.

Practice Points

- The clinical findings of sulfur spring dermatitis are similar to those of a superficial second-degree burn.

- Careful evaluation of the patient’s clinical history and recognition of characteristic findings are important for correct diagnosis.

- Patients with preexisting skin disorders who engage in thermal sulfur baths should be aware of the potential adverse effect of sulfur spring dermatitis.

Bilateral Onychodystrophy in a Boy With a History of Isolated Lichen Striatus