User login

Another look at overdiagnosis/remission of asthma

I appreciated the PURL, “Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis?” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707) that reminded clinicians to taper asthma controller medications in asymptomatic patients. The articles cited1,2 by Drs. Stevermer and Hayes documented that one-third of the adults enrolled in the respective study with physician-diagnosed asthma did not have objective evidence for asthma and were either over-diagnosed or had remitted. These articles also contained evidence that: 1) over-diagnosis was likely much more common than remission,1 and 2) there was a significant temporal trend towards increasing over-diagnosis/remission during the last several decades. The authors of the cited article1 suggested that the temporal trend could be explained by increased public awareness of respiratory symptoms, more aggressive marketing of asthma medications, and a lack of objective measurement of reversible airway obstruction in primary care. These assertions deserve careful consideration as we strive to diagnose asthma appropriately.

Over-diagnosis/remission is almost certainly not as prevalent (33%) as the authors of the cited articles1,2 reported. The reason is simple selection bias: 1) the cited study2 excluded asthma patients who smoked >10 pack-years (it enrolled 701 asthma patients and excluded 812 asthma patients with a >10 pack-year smoking history), and 2) this study likely did not include asthma patients with the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, which is treated as asthma and comprises an additional 30% of our patients with chronic airflow limitation (the asthma-COPD spectrum).3 Asthma patients who smoke and/or have the overlap syndrome are prone to severe asthma that is refractory to inhaled corticosteroids.3,4

In addition to making the correct diagnosis, it is equally important to be aware of efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma that primary care clinicians can easily use. There is now good evidence that azithromycin is efficacious for severe refractory asthma5 and should be considered prior to referral for immunomodulatory asthma therapies.6

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, Wis

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al; Canadian Respiratory Clinical Research Consortium. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

3. Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64:728-735.

4. Stapleton M, Howard-Thompson A, George C, et al. Smoking and asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24;313-322.

5. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017:390659-668.

6. Hahn DL, Grasmick M, Hetzel S, et al; AZMATICS (AZithroMycin-Asthma Trial In Community Settings) Study Group. Azithromycin for bronchial asthma in adults: an effectiveness trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:442-459.

Continue to: Authors' response...

Authors’ response:

We appreciate Dr. Hahn’s observations about the PURL1 on overdiagnosis of asthma. This article focused on the results of a prospective, multicenter cohort study2 that evaluated the feasibility of tapering, and in many patients, stopping asthma medications. We agree that if the study had included people diagnosed with asthma who also had smoked at least 10 pack-years or who also had COPD, the proportion of those who would eventually no longer meet diagnostic criteria for asthma would be lower than in this study. We are uncertain of the relative proportion of cases that were overdiagnosis, when compared with true remission of disease, as only 43% of those no longer meeting the diagnostic criteria for asthma had evidence of prior lung function testing, whether by formal spirometry, serial peak function testing, or bronchial challenge testing.

We agree that using efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma is essential, but the selection of those therapies was outside the scope of this PURL.

James J. Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Alisa Hayes, MD

Columbia, Mo

1. Stevermer JJ, Hayes A. Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis? J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

I appreciated the PURL, “Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis?” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707) that reminded clinicians to taper asthma controller medications in asymptomatic patients. The articles cited1,2 by Drs. Stevermer and Hayes documented that one-third of the adults enrolled in the respective study with physician-diagnosed asthma did not have objective evidence for asthma and were either over-diagnosed or had remitted. These articles also contained evidence that: 1) over-diagnosis was likely much more common than remission,1 and 2) there was a significant temporal trend towards increasing over-diagnosis/remission during the last several decades. The authors of the cited article1 suggested that the temporal trend could be explained by increased public awareness of respiratory symptoms, more aggressive marketing of asthma medications, and a lack of objective measurement of reversible airway obstruction in primary care. These assertions deserve careful consideration as we strive to diagnose asthma appropriately.

Over-diagnosis/remission is almost certainly not as prevalent (33%) as the authors of the cited articles1,2 reported. The reason is simple selection bias: 1) the cited study2 excluded asthma patients who smoked >10 pack-years (it enrolled 701 asthma patients and excluded 812 asthma patients with a >10 pack-year smoking history), and 2) this study likely did not include asthma patients with the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, which is treated as asthma and comprises an additional 30% of our patients with chronic airflow limitation (the asthma-COPD spectrum).3 Asthma patients who smoke and/or have the overlap syndrome are prone to severe asthma that is refractory to inhaled corticosteroids.3,4

In addition to making the correct diagnosis, it is equally important to be aware of efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma that primary care clinicians can easily use. There is now good evidence that azithromycin is efficacious for severe refractory asthma5 and should be considered prior to referral for immunomodulatory asthma therapies.6

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, Wis

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al; Canadian Respiratory Clinical Research Consortium. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

3. Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64:728-735.

4. Stapleton M, Howard-Thompson A, George C, et al. Smoking and asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24;313-322.

5. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017:390659-668.

6. Hahn DL, Grasmick M, Hetzel S, et al; AZMATICS (AZithroMycin-Asthma Trial In Community Settings) Study Group. Azithromycin for bronchial asthma in adults: an effectiveness trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:442-459.

Continue to: Authors' response...

Authors’ response:

We appreciate Dr. Hahn’s observations about the PURL1 on overdiagnosis of asthma. This article focused on the results of a prospective, multicenter cohort study2 that evaluated the feasibility of tapering, and in many patients, stopping asthma medications. We agree that if the study had included people diagnosed with asthma who also had smoked at least 10 pack-years or who also had COPD, the proportion of those who would eventually no longer meet diagnostic criteria for asthma would be lower than in this study. We are uncertain of the relative proportion of cases that were overdiagnosis, when compared with true remission of disease, as only 43% of those no longer meeting the diagnostic criteria for asthma had evidence of prior lung function testing, whether by formal spirometry, serial peak function testing, or bronchial challenge testing.

We agree that using efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma is essential, but the selection of those therapies was outside the scope of this PURL.

James J. Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Alisa Hayes, MD

Columbia, Mo

1. Stevermer JJ, Hayes A. Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis? J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

I appreciated the PURL, “Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis?” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707) that reminded clinicians to taper asthma controller medications in asymptomatic patients. The articles cited1,2 by Drs. Stevermer and Hayes documented that one-third of the adults enrolled in the respective study with physician-diagnosed asthma did not have objective evidence for asthma and were either over-diagnosed or had remitted. These articles also contained evidence that: 1) over-diagnosis was likely much more common than remission,1 and 2) there was a significant temporal trend towards increasing over-diagnosis/remission during the last several decades. The authors of the cited article1 suggested that the temporal trend could be explained by increased public awareness of respiratory symptoms, more aggressive marketing of asthma medications, and a lack of objective measurement of reversible airway obstruction in primary care. These assertions deserve careful consideration as we strive to diagnose asthma appropriately.

Over-diagnosis/remission is almost certainly not as prevalent (33%) as the authors of the cited articles1,2 reported. The reason is simple selection bias: 1) the cited study2 excluded asthma patients who smoked >10 pack-years (it enrolled 701 asthma patients and excluded 812 asthma patients with a >10 pack-year smoking history), and 2) this study likely did not include asthma patients with the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, which is treated as asthma and comprises an additional 30% of our patients with chronic airflow limitation (the asthma-COPD spectrum).3 Asthma patients who smoke and/or have the overlap syndrome are prone to severe asthma that is refractory to inhaled corticosteroids.3,4

In addition to making the correct diagnosis, it is equally important to be aware of efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma that primary care clinicians can easily use. There is now good evidence that azithromycin is efficacious for severe refractory asthma5 and should be considered prior to referral for immunomodulatory asthma therapies.6

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Madison, Wis

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al; Canadian Respiratory Clinical Research Consortium. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

3. Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64:728-735.

4. Stapleton M, Howard-Thompson A, George C, et al. Smoking and asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24;313-322.

5. Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017:390659-668.

6. Hahn DL, Grasmick M, Hetzel S, et al; AZMATICS (AZithroMycin-Asthma Trial In Community Settings) Study Group. Azithromycin for bronchial asthma in adults: an effectiveness trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:442-459.

Continue to: Authors' response...

Authors’ response:

We appreciate Dr. Hahn’s observations about the PURL1 on overdiagnosis of asthma. This article focused on the results of a prospective, multicenter cohort study2 that evaluated the feasibility of tapering, and in many patients, stopping asthma medications. We agree that if the study had included people diagnosed with asthma who also had smoked at least 10 pack-years or who also had COPD, the proportion of those who would eventually no longer meet diagnostic criteria for asthma would be lower than in this study. We are uncertain of the relative proportion of cases that were overdiagnosis, when compared with true remission of disease, as only 43% of those no longer meeting the diagnostic criteria for asthma had evidence of prior lung function testing, whether by formal spirometry, serial peak function testing, or bronchial challenge testing.

We agree that using efficacious therapies for severe refractory asthma is essential, but the selection of those therapies was outside the scope of this PURL.

James J. Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Alisa Hayes, MD

Columbia, Mo

1. Stevermer JJ, Hayes A. Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis? J Fam Pract. 2018;67:704-707.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al; Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

Asthma patients with sinusitis, polyps fare poorly after sinus surgery

CORONADO, CALIF. – Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis decreases quality of life improvement after sinus surgery in patients with concurrent asthma, results from a retrospective study demonstrated.

They also have significantly higher Lund-Kennedy endoscopy and Lund-McKay CT scores, compared with control groups.

“Patients with concurrent asthma and chronic sinusitis require more aggressive management than nonasthmatics,” one of the study authors, Aykut A. Unsal, DO, said in an interview in advance of the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Additionally, the degree of improvement of not only their sinusitis but possibly their asthma following medical/surgical treatment will also be limited if that patient also suffers from nasal polyps and/or eosinophilia. These patients will ultimately become more difficult to manage.”

In order to examine the relationship of eosinophilia and nasal polyps on quality of life (QOL) in patients with asthma who have chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) who were treated with surgery, Dr. Unsal and his associates reviewed the records of 457 patients with a diagnosis of CRS who underwent sinus surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta. The researchers subdivided patients based on the presence or absence of an asthma diagnosis and further subdivided them based on tissue eosinophilia and nasal polyposis. Next, they compared the Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22), Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scores, and Lund-McKay CT scores preoperatively and postoperatively at 6 months – 1 year and at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. They performed a T-test analysis to determine statistical significance.

Of the 457 patients included in the analysis, 92 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (eCRScNP), 20 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (eCRSsNP), 8 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (neCRScNP), and 16 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (neCRSsNP). The researchers observed that patients in the eCRScNP group showed no difference in QOL preoperatively, but their QOL declined significantly at the 1- and 2-year analysis (P less than .03). No significant QOL improvement appeared in the eCRSsNP group until 4 years (P less than .008), and there was no significant QOL difference among the neCRS groups regardless of nasal polyposis. A statistical difference in endoscopy scores was seen among patients in the preoperative neCRScNP group (P less than .001) and in the eCRScNP group from preoperatively until 5 years postoperatively (P less than .03). Finally, statistical significance appeared in preoperative CT scores analysis among patients in the eCRScNP group (P less than .001).

Dr. Unsal and his associates launched the study expecting that all patients with asthma were not only going to have worse symptoms scores, but also more recalcitrant disease. “This is based on our clinical experience, as well as previous literature that has shown that patients with exacerbations of asthma or sinusitis can worsen the symptoms of the other comorbid disease,” he said. “The opposite is also true; effective treatment of chronic sinusitis has been shown to also improve asthma symptoms. Our findings partially validated what we expected, as asthma patients were typically worse by symptom, endoscopy, and CT scores across the board.

“What we discovered, however, was there was one population of patients where no differences demonstrated between the two groups preoperatively and postoperatively: Patients who were negative for both polyp disease and eosinophilia, considered the least severe sinus disease. Additionally, generally no statistical differences in disease and symptom severity were identified following surgery between the two groups if they had a moderately severe form of chronic sinusitis [patients who were either positive for polyps or positive for eosinophilia],” Dr. Unsal said.

He and his colleagues also found that the group with the most severe form (positive eosinophila and positive polyps) fared worse symptomatically and objectively both preoperatively and postoperatively, compared with the other groups.

Dr. Unsal acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including that the type of asthma each patient had (whether they were controlled intermittent or whether they had moderate or persistent asthma) was not recorded, “so we don’t actually know to what degree asthma severity played a role in sinus disease, nor the improvement in asthma severity following sinus surgery/medical therapy,” he said. “Lastly, we did lose several patients to follow-up in the later years so the data is not as robust in the very long term.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The meeting was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

CORONADO, CALIF. – Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis decreases quality of life improvement after sinus surgery in patients with concurrent asthma, results from a retrospective study demonstrated.

They also have significantly higher Lund-Kennedy endoscopy and Lund-McKay CT scores, compared with control groups.

“Patients with concurrent asthma and chronic sinusitis require more aggressive management than nonasthmatics,” one of the study authors, Aykut A. Unsal, DO, said in an interview in advance of the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Additionally, the degree of improvement of not only their sinusitis but possibly their asthma following medical/surgical treatment will also be limited if that patient also suffers from nasal polyps and/or eosinophilia. These patients will ultimately become more difficult to manage.”

In order to examine the relationship of eosinophilia and nasal polyps on quality of life (QOL) in patients with asthma who have chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) who were treated with surgery, Dr. Unsal and his associates reviewed the records of 457 patients with a diagnosis of CRS who underwent sinus surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta. The researchers subdivided patients based on the presence or absence of an asthma diagnosis and further subdivided them based on tissue eosinophilia and nasal polyposis. Next, they compared the Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22), Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scores, and Lund-McKay CT scores preoperatively and postoperatively at 6 months – 1 year and at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. They performed a T-test analysis to determine statistical significance.

Of the 457 patients included in the analysis, 92 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (eCRScNP), 20 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (eCRSsNP), 8 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (neCRScNP), and 16 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (neCRSsNP). The researchers observed that patients in the eCRScNP group showed no difference in QOL preoperatively, but their QOL declined significantly at the 1- and 2-year analysis (P less than .03). No significant QOL improvement appeared in the eCRSsNP group until 4 years (P less than .008), and there was no significant QOL difference among the neCRS groups regardless of nasal polyposis. A statistical difference in endoscopy scores was seen among patients in the preoperative neCRScNP group (P less than .001) and in the eCRScNP group from preoperatively until 5 years postoperatively (P less than .03). Finally, statistical significance appeared in preoperative CT scores analysis among patients in the eCRScNP group (P less than .001).

Dr. Unsal and his associates launched the study expecting that all patients with asthma were not only going to have worse symptoms scores, but also more recalcitrant disease. “This is based on our clinical experience, as well as previous literature that has shown that patients with exacerbations of asthma or sinusitis can worsen the symptoms of the other comorbid disease,” he said. “The opposite is also true; effective treatment of chronic sinusitis has been shown to also improve asthma symptoms. Our findings partially validated what we expected, as asthma patients were typically worse by symptom, endoscopy, and CT scores across the board.

“What we discovered, however, was there was one population of patients where no differences demonstrated between the two groups preoperatively and postoperatively: Patients who were negative for both polyp disease and eosinophilia, considered the least severe sinus disease. Additionally, generally no statistical differences in disease and symptom severity were identified following surgery between the two groups if they had a moderately severe form of chronic sinusitis [patients who were either positive for polyps or positive for eosinophilia],” Dr. Unsal said.

He and his colleagues also found that the group with the most severe form (positive eosinophila and positive polyps) fared worse symptomatically and objectively both preoperatively and postoperatively, compared with the other groups.

Dr. Unsal acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including that the type of asthma each patient had (whether they were controlled intermittent or whether they had moderate or persistent asthma) was not recorded, “so we don’t actually know to what degree asthma severity played a role in sinus disease, nor the improvement in asthma severity following sinus surgery/medical therapy,” he said. “Lastly, we did lose several patients to follow-up in the later years so the data is not as robust in the very long term.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The meeting was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

CORONADO, CALIF. – Eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis decreases quality of life improvement after sinus surgery in patients with concurrent asthma, results from a retrospective study demonstrated.

They also have significantly higher Lund-Kennedy endoscopy and Lund-McKay CT scores, compared with control groups.

“Patients with concurrent asthma and chronic sinusitis require more aggressive management than nonasthmatics,” one of the study authors, Aykut A. Unsal, DO, said in an interview in advance of the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Additionally, the degree of improvement of not only their sinusitis but possibly their asthma following medical/surgical treatment will also be limited if that patient also suffers from nasal polyps and/or eosinophilia. These patients will ultimately become more difficult to manage.”

In order to examine the relationship of eosinophilia and nasal polyps on quality of life (QOL) in patients with asthma who have chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) who were treated with surgery, Dr. Unsal and his associates reviewed the records of 457 patients with a diagnosis of CRS who underwent sinus surgery in the department of otolaryngology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta. The researchers subdivided patients based on the presence or absence of an asthma diagnosis and further subdivided them based on tissue eosinophilia and nasal polyposis. Next, they compared the Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22), Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scores, and Lund-McKay CT scores preoperatively and postoperatively at 6 months – 1 year and at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. They performed a T-test analysis to determine statistical significance.

Of the 457 patients included in the analysis, 92 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (eCRScNP), 20 had asthma and eosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (eCRSsNP), 8 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps (neCRScNP), and 16 had asthma and noneosinophilic CRS without nasal polyps (neCRSsNP). The researchers observed that patients in the eCRScNP group showed no difference in QOL preoperatively, but their QOL declined significantly at the 1- and 2-year analysis (P less than .03). No significant QOL improvement appeared in the eCRSsNP group until 4 years (P less than .008), and there was no significant QOL difference among the neCRS groups regardless of nasal polyposis. A statistical difference in endoscopy scores was seen among patients in the preoperative neCRScNP group (P less than .001) and in the eCRScNP group from preoperatively until 5 years postoperatively (P less than .03). Finally, statistical significance appeared in preoperative CT scores analysis among patients in the eCRScNP group (P less than .001).

Dr. Unsal and his associates launched the study expecting that all patients with asthma were not only going to have worse symptoms scores, but also more recalcitrant disease. “This is based on our clinical experience, as well as previous literature that has shown that patients with exacerbations of asthma or sinusitis can worsen the symptoms of the other comorbid disease,” he said. “The opposite is also true; effective treatment of chronic sinusitis has been shown to also improve asthma symptoms. Our findings partially validated what we expected, as asthma patients were typically worse by symptom, endoscopy, and CT scores across the board.

“What we discovered, however, was there was one population of patients where no differences demonstrated between the two groups preoperatively and postoperatively: Patients who were negative for both polyp disease and eosinophilia, considered the least severe sinus disease. Additionally, generally no statistical differences in disease and symptom severity were identified following surgery between the two groups if they had a moderately severe form of chronic sinusitis [patients who were either positive for polyps or positive for eosinophilia],” Dr. Unsal said.

He and his colleagues also found that the group with the most severe form (positive eosinophila and positive polyps) fared worse symptomatically and objectively both preoperatively and postoperatively, compared with the other groups.

Dr. Unsal acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including that the type of asthma each patient had (whether they were controlled intermittent or whether they had moderate or persistent asthma) was not recorded, “so we don’t actually know to what degree asthma severity played a role in sinus disease, nor the improvement in asthma severity following sinus surgery/medical therapy,” he said. “Lastly, we did lose several patients to follow-up in the later years so the data is not as robust in the very long term.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The meeting was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons.

REPORTING FROM THE TRIOLOGICAL CSWM

Key clinical point: Patients with asthma and the most severe form of chronic rhinosinusitis fare poorly on quality of life measures following sinus surgery.

Major finding: QOL in patients who had asthma and eosinophilic CRS with nasal polyps declined significantly at the 1- and 2-year analysis (P less than .03).

Study details: A single-center review of 457 patients with CRS who underwent sinus surgery.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

In pediatric asthma, jet nebulizers beat breath enhanced

In children with moderate to severe acute asthma, albuterol delivered by a conventional jet nebulizer led to more improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) than delivery via a breath-enhanced nebulizer.

Only one previous study has compared the two types of nebulizers in children with acute asthma. It showed that the new technology is noninferior to the older device, but it had a small sample size and did not examine spirometry data.

Mike Gardiner, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and Matthew H. Wilkinson, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, conducted a randomized, observer-blind study to look at effectiveness of these two nebulizers in a larger population of pediatric users. The results were published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

At a large, urban pediatric emergency department, researchers randomized 107 children (aged 6-18 years) presenting with a moderate to severe asthma exacerbation to receive one or the other nebulizer.

Children treated with the conventional jet nebulizer had a greater improvement in FEV1 (+13.8% vs. +9.1% of predicted; P = .04). The improvements were similar in a subgroup analysis of 57 subjects who met ATS/ERS (American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society) spirometry guidelines (+14.5% vs. +8.5% of predicted; P = .03).

The researchers found no significant differences in changes in Pediatric Asthma Score, Pediatric Asthma Severity Score, ED length of stay, or admission rate. There was no significant difference in side effects between the two groups.

Breath-enhanced nebulizers use a holding chamber to store continuously nebulized medication, and one-way valves that direct exhaled air away from the holding chamber. The system reduces medication loss during exhalation and delivers a bolus of medication.

In lung models and healthy adult controls, breath-enhanced nebulizers achieved more effective lung deposition of aerosol. The authors speculate that the reduced clinical effect of the breath-enhanced nebulizer could be because the design of the mouthpiece, which allows a nonaerosolized “dead space” volume to be inhaled first. This volume may have a greater clinical impact in children than in adults.

Children experiencing asthma also have a rapid and shallow breathing pattern, which could also lead to a larger contribution of “dead space” to the overall dose, thus reducing drug exposure.

The study, Comparison of Breath-Enhanced and T-Piece Nebulizers in Children With Acute Asthma (NCT02566902) was funded by the University of Texas Southwestern, Austin. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gardiner M, Wilkinson M. J Pediatr. 2019;204:245-9.

In children with moderate to severe acute asthma, albuterol delivered by a conventional jet nebulizer led to more improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) than delivery via a breath-enhanced nebulizer.

Only one previous study has compared the two types of nebulizers in children with acute asthma. It showed that the new technology is noninferior to the older device, but it had a small sample size and did not examine spirometry data.

Mike Gardiner, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and Matthew H. Wilkinson, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, conducted a randomized, observer-blind study to look at effectiveness of these two nebulizers in a larger population of pediatric users. The results were published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

At a large, urban pediatric emergency department, researchers randomized 107 children (aged 6-18 years) presenting with a moderate to severe asthma exacerbation to receive one or the other nebulizer.

Children treated with the conventional jet nebulizer had a greater improvement in FEV1 (+13.8% vs. +9.1% of predicted; P = .04). The improvements were similar in a subgroup analysis of 57 subjects who met ATS/ERS (American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society) spirometry guidelines (+14.5% vs. +8.5% of predicted; P = .03).

The researchers found no significant differences in changes in Pediatric Asthma Score, Pediatric Asthma Severity Score, ED length of stay, or admission rate. There was no significant difference in side effects between the two groups.

Breath-enhanced nebulizers use a holding chamber to store continuously nebulized medication, and one-way valves that direct exhaled air away from the holding chamber. The system reduces medication loss during exhalation and delivers a bolus of medication.

In lung models and healthy adult controls, breath-enhanced nebulizers achieved more effective lung deposition of aerosol. The authors speculate that the reduced clinical effect of the breath-enhanced nebulizer could be because the design of the mouthpiece, which allows a nonaerosolized “dead space” volume to be inhaled first. This volume may have a greater clinical impact in children than in adults.

Children experiencing asthma also have a rapid and shallow breathing pattern, which could also lead to a larger contribution of “dead space” to the overall dose, thus reducing drug exposure.

The study, Comparison of Breath-Enhanced and T-Piece Nebulizers in Children With Acute Asthma (NCT02566902) was funded by the University of Texas Southwestern, Austin. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gardiner M, Wilkinson M. J Pediatr. 2019;204:245-9.

In children with moderate to severe acute asthma, albuterol delivered by a conventional jet nebulizer led to more improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) than delivery via a breath-enhanced nebulizer.

Only one previous study has compared the two types of nebulizers in children with acute asthma. It showed that the new technology is noninferior to the older device, but it had a small sample size and did not examine spirometry data.

Mike Gardiner, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and Matthew H. Wilkinson, MD, of the department of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, conducted a randomized, observer-blind study to look at effectiveness of these two nebulizers in a larger population of pediatric users. The results were published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

At a large, urban pediatric emergency department, researchers randomized 107 children (aged 6-18 years) presenting with a moderate to severe asthma exacerbation to receive one or the other nebulizer.

Children treated with the conventional jet nebulizer had a greater improvement in FEV1 (+13.8% vs. +9.1% of predicted; P = .04). The improvements were similar in a subgroup analysis of 57 subjects who met ATS/ERS (American Thoracic Society/ European Respiratory Society) spirometry guidelines (+14.5% vs. +8.5% of predicted; P = .03).

The researchers found no significant differences in changes in Pediatric Asthma Score, Pediatric Asthma Severity Score, ED length of stay, or admission rate. There was no significant difference in side effects between the two groups.

Breath-enhanced nebulizers use a holding chamber to store continuously nebulized medication, and one-way valves that direct exhaled air away from the holding chamber. The system reduces medication loss during exhalation and delivers a bolus of medication.

In lung models and healthy adult controls, breath-enhanced nebulizers achieved more effective lung deposition of aerosol. The authors speculate that the reduced clinical effect of the breath-enhanced nebulizer could be because the design of the mouthpiece, which allows a nonaerosolized “dead space” volume to be inhaled first. This volume may have a greater clinical impact in children than in adults.

Children experiencing asthma also have a rapid and shallow breathing pattern, which could also lead to a larger contribution of “dead space” to the overall dose, thus reducing drug exposure.

The study, Comparison of Breath-Enhanced and T-Piece Nebulizers in Children With Acute Asthma (NCT02566902) was funded by the University of Texas Southwestern, Austin. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gardiner M, Wilkinson M. J Pediatr. 2019;204:245-9.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: New nebulizers worked better in adults, but pediatric populations may pose a challenge.

Major finding: FEV1 improved +13.8% in standard inhalers vs. +9.1% in breath-enhanced analyzers.

Study details: Randomized, controlled trial (n = 107).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the University of Texas Southwestern, Austin. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Gardiner M, Wilkinson M. J Pediatr. 2019;204:245-9.

Benralizumab maintains effectiveness in severe asthma at 2 years

out to 2 years, according findings of the BORA trial, an extension study of the phase 3 SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. The study follows up and reinforces previously reported 1-year data and was reported by William W. Busse, MD, of University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his colleagues in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

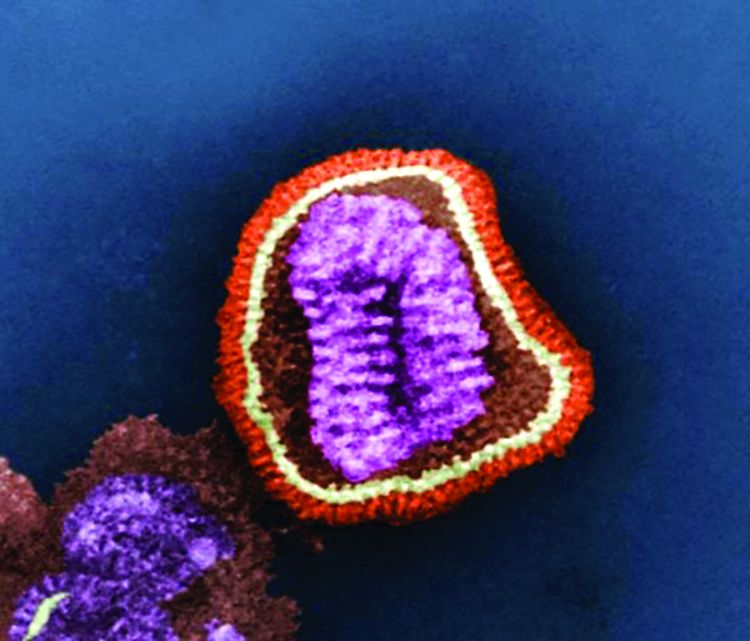

Benralizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5 receptor alpha. It causes rapid deletion of eosinophils through cell-mediated cytotoxicity. A 30-mg dose of benralizumab every 8 weeks is approved for severe asthma treatment in Canada, Europe, Japan, the United States, and other countries.

In the second year of treatment, there were no new adverse events associated with depleted eosinophils, and the frequency of opportunistic infections was similar to that observed in the first year.

Eosinophilic inflammation occurs in about half of asthma cases and is associated with greater severity.

The 48-week SIROCCO trial, the 56-week CALIMA trial, and the 28-week ZONDA trial tested the effect of benralizumab 30 mg given every 4 weeks or 8 weeks, combined with high-dosage inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists. The 8-week dose of the drug reduced annual exacerbations by 51%, compared with placebo in the SIROCCO trial and by 28% in the CALIMA trial. In the ZONDA trial, benralizumab reduced oral glucocorticoid use by 75%, compared with placebo, and by 25% from baseline.

The BORA extension trial included participants in the previous three trials. In the current report, researchers presented results from the analysis from BORA participants recruited from the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. Data from participants from all three trials will be reported in the future.

The analysis included 1,576 patients who continued to receive benralizumab after being assigned to the treatment arm in SIROCCO or CALIMA, or who had received placebo were randomized to benralizumab on the 4-week (n = 783; 265 from placebo) or 8-week dose (n = 793; 281 from placebo) schedule.

A total of 166 patients, or about 10% in each group, discontinued treatment. The frequency of any serious adverse event (SAE) ranged between 10% and 11% in all groups. SAEs associated with infections ranged from 1% to 3%, indicating that there were no significant differences in SAE frequencies between those who were originally assigned to placebo and those who originally received benralizumab. That suggests no safety differences between receiving the drug for 1 year or 2 years.

A total of 1,046 subjects had blood eosinophil counts of 300 cells per mcL or greater at baseline; 72% of these patients had no asthma exacerbations during the BORA study. This was true for 74% of patients in the 8-week treatment arm.

The crude asthma exacerbation rate for patients who received benralizumab in SIROCCO or CALIMA was 0.48 in the 4-week arm, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.56) and 0.46 in the 8-week arm (95% CI, 0.39-0.53). For patients who started out on placebo, the crude exacerbation rate during BORA was 0.53 in the 4-week group (95% CI, 0.43-0.65) and 0.57 in the 8-week group (95% CI, 0.47-0.68).

Patients who started on benralizumab had similar exacerbation frequencies during year 1 and year 2.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. The authors have received fees from AstraZeneca and other pharmaceutical companies, and some are employees of AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Busse WW et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jan 1;7(1):46-59.

out to 2 years, according findings of the BORA trial, an extension study of the phase 3 SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. The study follows up and reinforces previously reported 1-year data and was reported by William W. Busse, MD, of University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his colleagues in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Benralizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5 receptor alpha. It causes rapid deletion of eosinophils through cell-mediated cytotoxicity. A 30-mg dose of benralizumab every 8 weeks is approved for severe asthma treatment in Canada, Europe, Japan, the United States, and other countries.

In the second year of treatment, there were no new adverse events associated with depleted eosinophils, and the frequency of opportunistic infections was similar to that observed in the first year.

Eosinophilic inflammation occurs in about half of asthma cases and is associated with greater severity.

The 48-week SIROCCO trial, the 56-week CALIMA trial, and the 28-week ZONDA trial tested the effect of benralizumab 30 mg given every 4 weeks or 8 weeks, combined with high-dosage inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists. The 8-week dose of the drug reduced annual exacerbations by 51%, compared with placebo in the SIROCCO trial and by 28% in the CALIMA trial. In the ZONDA trial, benralizumab reduced oral glucocorticoid use by 75%, compared with placebo, and by 25% from baseline.

The BORA extension trial included participants in the previous three trials. In the current report, researchers presented results from the analysis from BORA participants recruited from the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. Data from participants from all three trials will be reported in the future.

The analysis included 1,576 patients who continued to receive benralizumab after being assigned to the treatment arm in SIROCCO or CALIMA, or who had received placebo were randomized to benralizumab on the 4-week (n = 783; 265 from placebo) or 8-week dose (n = 793; 281 from placebo) schedule.

A total of 166 patients, or about 10% in each group, discontinued treatment. The frequency of any serious adverse event (SAE) ranged between 10% and 11% in all groups. SAEs associated with infections ranged from 1% to 3%, indicating that there were no significant differences in SAE frequencies between those who were originally assigned to placebo and those who originally received benralizumab. That suggests no safety differences between receiving the drug for 1 year or 2 years.

A total of 1,046 subjects had blood eosinophil counts of 300 cells per mcL or greater at baseline; 72% of these patients had no asthma exacerbations during the BORA study. This was true for 74% of patients in the 8-week treatment arm.

The crude asthma exacerbation rate for patients who received benralizumab in SIROCCO or CALIMA was 0.48 in the 4-week arm, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.56) and 0.46 in the 8-week arm (95% CI, 0.39-0.53). For patients who started out on placebo, the crude exacerbation rate during BORA was 0.53 in the 4-week group (95% CI, 0.43-0.65) and 0.57 in the 8-week group (95% CI, 0.47-0.68).

Patients who started on benralizumab had similar exacerbation frequencies during year 1 and year 2.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. The authors have received fees from AstraZeneca and other pharmaceutical companies, and some are employees of AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Busse WW et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jan 1;7(1):46-59.

out to 2 years, according findings of the BORA trial, an extension study of the phase 3 SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. The study follows up and reinforces previously reported 1-year data and was reported by William W. Busse, MD, of University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his colleagues in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Benralizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets interleukin-5 receptor alpha. It causes rapid deletion of eosinophils through cell-mediated cytotoxicity. A 30-mg dose of benralizumab every 8 weeks is approved for severe asthma treatment in Canada, Europe, Japan, the United States, and other countries.

In the second year of treatment, there were no new adverse events associated with depleted eosinophils, and the frequency of opportunistic infections was similar to that observed in the first year.

Eosinophilic inflammation occurs in about half of asthma cases and is associated with greater severity.

The 48-week SIROCCO trial, the 56-week CALIMA trial, and the 28-week ZONDA trial tested the effect of benralizumab 30 mg given every 4 weeks or 8 weeks, combined with high-dosage inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists. The 8-week dose of the drug reduced annual exacerbations by 51%, compared with placebo in the SIROCCO trial and by 28% in the CALIMA trial. In the ZONDA trial, benralizumab reduced oral glucocorticoid use by 75%, compared with placebo, and by 25% from baseline.

The BORA extension trial included participants in the previous three trials. In the current report, researchers presented results from the analysis from BORA participants recruited from the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials. Data from participants from all three trials will be reported in the future.

The analysis included 1,576 patients who continued to receive benralizumab after being assigned to the treatment arm in SIROCCO or CALIMA, or who had received placebo were randomized to benralizumab on the 4-week (n = 783; 265 from placebo) or 8-week dose (n = 793; 281 from placebo) schedule.

A total of 166 patients, or about 10% in each group, discontinued treatment. The frequency of any serious adverse event (SAE) ranged between 10% and 11% in all groups. SAEs associated with infections ranged from 1% to 3%, indicating that there were no significant differences in SAE frequencies between those who were originally assigned to placebo and those who originally received benralizumab. That suggests no safety differences between receiving the drug for 1 year or 2 years.

A total of 1,046 subjects had blood eosinophil counts of 300 cells per mcL or greater at baseline; 72% of these patients had no asthma exacerbations during the BORA study. This was true for 74% of patients in the 8-week treatment arm.

The crude asthma exacerbation rate for patients who received benralizumab in SIROCCO or CALIMA was 0.48 in the 4-week arm, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.56) and 0.46 in the 8-week arm (95% CI, 0.39-0.53). For patients who started out on placebo, the crude exacerbation rate during BORA was 0.53 in the 4-week group (95% CI, 0.43-0.65) and 0.57 in the 8-week group (95% CI, 0.47-0.68).

Patients who started on benralizumab had similar exacerbation frequencies during year 1 and year 2.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. The authors have received fees from AstraZeneca and other pharmaceutical companies, and some are employees of AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Busse WW et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jan 1;7(1):46-59.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The antibody had similar safety, efficacy in year 2 as in year 1.

Major finding: The crude asthma exacerbation rate for patients who received benralizumab in SIROCCO or CALIMA was 0.48 in the 4-week arm and 0.46 in the 8-week arm; the crude exacerbation rate during BORA was 0.53 in the 4-week group and 0.57 in the 8-week group.

Study details: Extension of randomized, clinical trial (n = 1,576).

Disclosures: AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. The authors have received fees from AstraZeneca and other pharmaceutical companies, and some are employees of AstraZeneca.

Source: Busse WW et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Jan 1;7(1):46-59.

Secondhand vaping aerosols linked to childhood asthma exacerbations

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Just like exposure to secondhand smoke, , according to a review of the 11,830 kids with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Every year, the Florida Department of Health surveys public school children aged 11-17 years about various tobacco issues. In 2016, almost 12% of the asthmatic children in the survey said they vaped. Almost half were exposed to secondhand smoke, and a third reported exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols within the past 30 days. Overall, 21% reported an asthma attack in the past 12 months.

Using data from the Florida survey, the investigators crunched the numbers and found that secondhand aerosol exposure increased the odds of an asthma attack by 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.47).

“Health professionals may wish to counsel asthmatic youth and their families regarding the potential risks of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery system] use and exposure to ENDS aerosols.” Providers “may also consider including ENDS aerosol exposure as a possible trigger in asthma self-management/action plans and updating asthma home environment assessments to include exposure to ENDS aerosols,” said investigators led by medical student Jennifer Bayly, a research fellow at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in Bethesda, Md.

About 4% of adults in the United States and 11% of high school students vape, and almost 10% of U.S. adolescents reported living with an ENDS user in 2014. Given the data, “it is likely that a substantial number of asthmatic youth are exposed,” the investigators said.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking e-cigarettes to asthma. There’s moderate evidence for increased cough and wheezing in adolescents who use e-cigarettes, plus an association with e-cigarette use and increased asthma exacerbations. The new study, however, is likely the first to look specifically at secondhand exposure among asthmatic children. Ingredients in vaping aerosols, including flavorings, propylene glycol, and vegetable glycerin, are physiologically active in the lungs, and may be lung irritants.

Overall, about half of the respondents were female, and two-thirds were 11-13 years old. About a third identified as Hispanic, a third as white, and just over a fifth as black. Three-quarters of the sample lived in large or midsized metropolitan areas, and close to two-thirds in stand-alone homes. Participants were considered exposed to secondhand aerosols if they reported that in the past month they were in a room or car with someone who was vaping.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

FROM CHEST®

Key clinical point: It’s important to screen asthmatic children for exposure to secondhand vaping aerosols, and minimize exposure.

Major finding: Secondhand aerosols increased the odds of an asthma attack 27%, independent of exposure to secondhand smoke and whether children smoked or vaped themselves.

Study details: Analysis of 11,830 children with asthma in the 2016 Florida Youth Tobacco survey.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: Bayly JE et al. CHEST®. 2018 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.005.

Biologics options for pediatric asthma continue to grow

ORLANDO – The goal of treatment is the same for all asthma cases, regardless of severity: “to enable a patient to achieve and maintain control over their asthma,” according to Stanley J. Szefler, MD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

That goal includes “reducing the risk of exacerbations, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and progression as well as reducing impairments, including symptoms, functional limitations, poor quality of life, and other manifestations of asthma,” Dr. Szefler, also director of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado pediatric asthma research program, told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Severe asthma challenges

These aims are more difficult with severe asthma, defined by the World Health Organization as “the current level of clinical control and risks which can result in frequent severe exacerbations and/or adverse reactions to medications and/or chronic morbidity,” Dr. Szefler explained. Severe asthma includes untreated severe asthma, difficult-to-treat asthma, and treatment-resistant severe asthma, whether controlled on high-dose medication or not.

Allergen sensitization, viral respiratory infections, and respiratory irritants (such as air pollution and smoking) are common features of severe asthma in children. Also common are challenges specific to management: poor medication adherence, poor technique for inhaled medications, and undertreatment. Poor management can lead to repeated exacerbations, adverse effects from drugs, disease progression, possible development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and early mortality.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute EPR-3 guidelines for treatment of pediatric asthma recommend a stepwise approach to therapy, starting with short-acting beta2-agonists as needed (SABA p.r.n.). The clinician then assesses the patient’s symptoms, exacerbations, side effects, quality of life, and lung function to determine whether the asthma is well managed or requires inhaled corticosteroids, or another therapy in moving through the steps. Each step also involves patient education, environmental control, and management of the child’s comorbidities.

It is not until steps 5 and 6 that the guidelines advise considering the biologic omalizumab for patients who have allergies. But other biologic options exist as well. Four biologics currently approved for treating asthma include omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab, and reslizumab, but reslizumab is approved only for patients at least 18 years old.

Biologics for pediatric asthma

Omalizumab, which targets IgE, is appropriate for patients at least 6 years old in whom inhaled corticosteroids could not adequately control the symptoms of moderate to-severe persistent asthma. Dosing of omalizumab is a subcutaneous injection every 2-4 weeks based on pretreatment serum IgE and body weight using a dosing table that starts at 0.016 mg/kg/IgE (IU/mL). Maximum dose is 375 mg every 2 weeks in the United States and 600 mg every 2 weeks in the European Union.

The advantages of an anti-IgE drug are its use only once a month and its substantial effect on reducing exacerbations in a clearly identified population. However, these drugs are costly and require supervised administration, Dr. Szefler noted. They also carry a risk of anaphylaxis in less than 0.2% of patients, requiring the patient to be monitored after first administration and to carry an injectable epinephrine after omalizumab administration as a precaution for late-occurring anaphylaxis.

Mepolizumab is an anti–interleukin (IL)–5 drug used in patients at least 12 years old with severe persistent asthma that’s inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids. Peripheral blood counts of eosinophilia determine if a patient has an eosinophilic phenotype, which has the best response to mepolizumab. People with at least 150 cells per microliter at baseline or at least 300 cells per microliter within the past year have shown a good response to mepolizumab. Dosing is 100 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks.

For patients with atopic asthma, mepolizumab is effective in reducing the daily oral corticosteroid dose and the number of both annual exacerbations and exacerbations requiring hospitalization or an emergency visit. Other benefits of mepolizumab include increasing the time to a first exacerbation, the pre- and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and overall quality of life.

Patient reductions in exacerbations while taking mepolizumab were associated with eosinophil count but not IgE, atopic status, FEV1 or bronchodilator response in the DREAM study (Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380[9842]:651-9.).

Two safety considerations with mepolizumab include an increased risk of shingles and the risk of a preexisting helminth infection getting worse. Providers should screen for helminth infection and might consider a herpes zoster vaccination prior to starting therapy, Dr. Szefler said.

Benralizumab is an anti-IL5Ra for use in people at least 12 years old with severe persistent asthma and an eosinophilic phenotype (at least 300 cells per microliter). Dosing begins with three subcutaneous injections of 30 mg every 4 weeks, followed by administration every 8 weeks thereafter.

Benralizumab’s clinical effects include reduced exacerbations and oral corticosteroid use, and improved asthma symptom scores and prebronchodilator FEV1. Higher serum eosinophils and a history of more frequent exacerbations are both biomarkers for reduced exacerbations with benralizumab treatment.

Dupilumab: New kid on the block

The newest biologic for asthma is dupilumab, approved Oct. 19, 2018, by the Food and Drug Administration as the only asthma biologic that patients can administer at home. Dupilumab is an anti–IL-4 and anti–IL-13 biologic whose most recent study results showed a severe exacerbations rate 50% lower than placebo (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 28;378[26]:2486-96.). Patients with higher baseline levels of eosinophils had the best response, although some patients showed hypereosinophilia following dupilumab therapy.

The study had a low number of adolescents enrolled, however, and more data on predictive biomarkers are needed. Dupilumab also requires a twice-monthly administration.

“It could be potentially better than those currently available due to additional effect on FEV1,” Dr. Szefler said, but cost and safety may determine how dupilumab is recommended and used, including possible use for early intervention.

As development in biologics for pediatric asthma continues to grow, questions about best practices for management remain, such as what age is best for starting biologics, what strategies are most safe and effective, and what risks and benefits exist for each strategy. Questions also remain regarding the risk factors for asthma and what early intervention strategies might change the disease’s natural history.

“Look at asthma in children as a chronic disease that can result in potentially preventable adverse respiratory outcomes in adulthood,” Dr. Szefler said. He recommended monitoring children’s lung function over time and using “measures of clinical outcomes, lung function, and biomarkers to assess potential benefits of biologic therapy.”

Dr. Szefler has served on the advisory board for Regeneron and Sanofi, and he has consulted for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Propeller Health.

ORLANDO – The goal of treatment is the same for all asthma cases, regardless of severity: “to enable a patient to achieve and maintain control over their asthma,” according to Stanley J. Szefler, MD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

That goal includes “reducing the risk of exacerbations, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and progression as well as reducing impairments, including symptoms, functional limitations, poor quality of life, and other manifestations of asthma,” Dr. Szefler, also director of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado pediatric asthma research program, told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Severe asthma challenges

These aims are more difficult with severe asthma, defined by the World Health Organization as “the current level of clinical control and risks which can result in frequent severe exacerbations and/or adverse reactions to medications and/or chronic morbidity,” Dr. Szefler explained. Severe asthma includes untreated severe asthma, difficult-to-treat asthma, and treatment-resistant severe asthma, whether controlled on high-dose medication or not.

Allergen sensitization, viral respiratory infections, and respiratory irritants (such as air pollution and smoking) are common features of severe asthma in children. Also common are challenges specific to management: poor medication adherence, poor technique for inhaled medications, and undertreatment. Poor management can lead to repeated exacerbations, adverse effects from drugs, disease progression, possible development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and early mortality.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute EPR-3 guidelines for treatment of pediatric asthma recommend a stepwise approach to therapy, starting with short-acting beta2-agonists as needed (SABA p.r.n.). The clinician then assesses the patient’s symptoms, exacerbations, side effects, quality of life, and lung function to determine whether the asthma is well managed or requires inhaled corticosteroids, or another therapy in moving through the steps. Each step also involves patient education, environmental control, and management of the child’s comorbidities.

It is not until steps 5 and 6 that the guidelines advise considering the biologic omalizumab for patients who have allergies. But other biologic options exist as well. Four biologics currently approved for treating asthma include omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab, and reslizumab, but reslizumab is approved only for patients at least 18 years old.

Biologics for pediatric asthma

Omalizumab, which targets IgE, is appropriate for patients at least 6 years old in whom inhaled corticosteroids could not adequately control the symptoms of moderate to-severe persistent asthma. Dosing of omalizumab is a subcutaneous injection every 2-4 weeks based on pretreatment serum IgE and body weight using a dosing table that starts at 0.016 mg/kg/IgE (IU/mL). Maximum dose is 375 mg every 2 weeks in the United States and 600 mg every 2 weeks in the European Union.

The advantages of an anti-IgE drug are its use only once a month and its substantial effect on reducing exacerbations in a clearly identified population. However, these drugs are costly and require supervised administration, Dr. Szefler noted. They also carry a risk of anaphylaxis in less than 0.2% of patients, requiring the patient to be monitored after first administration and to carry an injectable epinephrine after omalizumab administration as a precaution for late-occurring anaphylaxis.

Mepolizumab is an anti–interleukin (IL)–5 drug used in patients at least 12 years old with severe persistent asthma that’s inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids. Peripheral blood counts of eosinophilia determine if a patient has an eosinophilic phenotype, which has the best response to mepolizumab. People with at least 150 cells per microliter at baseline or at least 300 cells per microliter within the past year have shown a good response to mepolizumab. Dosing is 100 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks.

For patients with atopic asthma, mepolizumab is effective in reducing the daily oral corticosteroid dose and the number of both annual exacerbations and exacerbations requiring hospitalization or an emergency visit. Other benefits of mepolizumab include increasing the time to a first exacerbation, the pre- and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and overall quality of life.

Patient reductions in exacerbations while taking mepolizumab were associated with eosinophil count but not IgE, atopic status, FEV1 or bronchodilator response in the DREAM study (Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380[9842]:651-9.).

Two safety considerations with mepolizumab include an increased risk of shingles and the risk of a preexisting helminth infection getting worse. Providers should screen for helminth infection and might consider a herpes zoster vaccination prior to starting therapy, Dr. Szefler said.

Benralizumab is an anti-IL5Ra for use in people at least 12 years old with severe persistent asthma and an eosinophilic phenotype (at least 300 cells per microliter). Dosing begins with three subcutaneous injections of 30 mg every 4 weeks, followed by administration every 8 weeks thereafter.

Benralizumab’s clinical effects include reduced exacerbations and oral corticosteroid use, and improved asthma symptom scores and prebronchodilator FEV1. Higher serum eosinophils and a history of more frequent exacerbations are both biomarkers for reduced exacerbations with benralizumab treatment.

Dupilumab: New kid on the block

The newest biologic for asthma is dupilumab, approved Oct. 19, 2018, by the Food and Drug Administration as the only asthma biologic that patients can administer at home. Dupilumab is an anti–IL-4 and anti–IL-13 biologic whose most recent study results showed a severe exacerbations rate 50% lower than placebo (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 28;378[26]:2486-96.). Patients with higher baseline levels of eosinophils had the best response, although some patients showed hypereosinophilia following dupilumab therapy.

The study had a low number of adolescents enrolled, however, and more data on predictive biomarkers are needed. Dupilumab also requires a twice-monthly administration.

“It could be potentially better than those currently available due to additional effect on FEV1,” Dr. Szefler said, but cost and safety may determine how dupilumab is recommended and used, including possible use for early intervention.

As development in biologics for pediatric asthma continues to grow, questions about best practices for management remain, such as what age is best for starting biologics, what strategies are most safe and effective, and what risks and benefits exist for each strategy. Questions also remain regarding the risk factors for asthma and what early intervention strategies might change the disease’s natural history.

“Look at asthma in children as a chronic disease that can result in potentially preventable adverse respiratory outcomes in adulthood,” Dr. Szefler said. He recommended monitoring children’s lung function over time and using “measures of clinical outcomes, lung function, and biomarkers to assess potential benefits of biologic therapy.”

Dr. Szefler has served on the advisory board for Regeneron and Sanofi, and he has consulted for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Propeller Health.

ORLANDO – The goal of treatment is the same for all asthma cases, regardless of severity: “to enable a patient to achieve and maintain control over their asthma,” according to Stanley J. Szefler, MD, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

That goal includes “reducing the risk of exacerbations, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and progression as well as reducing impairments, including symptoms, functional limitations, poor quality of life, and other manifestations of asthma,” Dr. Szefler, also director of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado pediatric asthma research program, told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Severe asthma challenges

These aims are more difficult with severe asthma, defined by the World Health Organization as “the current level of clinical control and risks which can result in frequent severe exacerbations and/or adverse reactions to medications and/or chronic morbidity,” Dr. Szefler explained. Severe asthma includes untreated severe asthma, difficult-to-treat asthma, and treatment-resistant severe asthma, whether controlled on high-dose medication or not.

Allergen sensitization, viral respiratory infections, and respiratory irritants (such as air pollution and smoking) are common features of severe asthma in children. Also common are challenges specific to management: poor medication adherence, poor technique for inhaled medications, and undertreatment. Poor management can lead to repeated exacerbations, adverse effects from drugs, disease progression, possible development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and early mortality.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute EPR-3 guidelines for treatment of pediatric asthma recommend a stepwise approach to therapy, starting with short-acting beta2-agonists as needed (SABA p.r.n.). The clinician then assesses the patient’s symptoms, exacerbations, side effects, quality of life, and lung function to determine whether the asthma is well managed or requires inhaled corticosteroids, or another therapy in moving through the steps. Each step also involves patient education, environmental control, and management of the child’s comorbidities.

It is not until steps 5 and 6 that the guidelines advise considering the biologic omalizumab for patients who have allergies. But other biologic options exist as well. Four biologics currently approved for treating asthma include omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab, and reslizumab, but reslizumab is approved only for patients at least 18 years old.

Biologics for pediatric asthma

Omalizumab, which targets IgE, is appropriate for patients at least 6 years old in whom inhaled corticosteroids could not adequately control the symptoms of moderate to-severe persistent asthma. Dosing of omalizumab is a subcutaneous injection every 2-4 weeks based on pretreatment serum IgE and body weight using a dosing table that starts at 0.016 mg/kg/IgE (IU/mL). Maximum dose is 375 mg every 2 weeks in the United States and 600 mg every 2 weeks in the European Union.

The advantages of an anti-IgE drug are its use only once a month and its substantial effect on reducing exacerbations in a clearly identified population. However, these drugs are costly and require supervised administration, Dr. Szefler noted. They also carry a risk of anaphylaxis in less than 0.2% of patients, requiring the patient to be monitored after first administration and to carry an injectable epinephrine after omalizumab administration as a precaution for late-occurring anaphylaxis.

Mepolizumab is an anti–interleukin (IL)–5 drug used in patients at least 12 years old with severe persistent asthma that’s inadequately controlled with inhaled corticosteroids. Peripheral blood counts of eosinophilia determine if a patient has an eosinophilic phenotype, which has the best response to mepolizumab. People with at least 150 cells per microliter at baseline or at least 300 cells per microliter within the past year have shown a good response to mepolizumab. Dosing is 100 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks.

For patients with atopic asthma, mepolizumab is effective in reducing the daily oral corticosteroid dose and the number of both annual exacerbations and exacerbations requiring hospitalization or an emergency visit. Other benefits of mepolizumab include increasing the time to a first exacerbation, the pre- and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and overall quality of life.

Patient reductions in exacerbations while taking mepolizumab were associated with eosinophil count but not IgE, atopic status, FEV1 or bronchodilator response in the DREAM study (Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380[9842]:651-9.).

Two safety considerations with mepolizumab include an increased risk of shingles and the risk of a preexisting helminth infection getting worse. Providers should screen for helminth infection and might consider a herpes zoster vaccination prior to starting therapy, Dr. Szefler said.