User login

Treating the effects of bruxism with botulinum toxin

Bruxism is grinding and clenching of the teeth with unconscious contractions of the temporal and masseter muscles while awake or during sleep. Bruxism occurs in 8%-16% of the population and is often an underdiagnosed condition that not only leads to dental problems but also to pain in the teeth, jaw, temporomandibular joint, and neck; headaches; and potentially, to tooth loss.

Although the pathogenesis of bruxism remains unclear, multiple factors, such as physical or psychological stress, malocclusion, sleep disorders and medication side effects, can cause bruxism. Treatment can be difficult given psychogenic and neurogenic components, and bruxism can be resistant to medical and behavioral therapy. There are various treatment options for bruxism, including oral splints; medications, such as muscle relaxants; antidepressants; and botulinum toxin. Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin injections into the masseter and temporalis muscles result in relaxation of the muscles and improvement of bruxism and the pain associated with chronic clenching and grinding.

In a recent study by Al-Wayli, 50 subjects who reported nocturnal bruxism were randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus conventional treatment (pharmacotherapy or oral splints). After 3 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year, patients who received botulinum toxin had significantly less pain after only one treatment than did the traditional treatment group. Similarly, in a study by Lee et al., subjects randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus a placebo saline injections showed not only decreased pain but also decreased bruxism seen with nocturnal electromyography.

In our clinic, Botulinum toxin when injected into the temporalis and masseter muscles also helps with tension headaches and migraines related to clenching of the jaw. Albeit effective, the dose of botulinum toxin used in the aforementioned studies ranged between 25 U and 40 U of botulinum toxin and were lower than what we have found to be effective. Our patients receive 50 U botulinum toxin in each masseter muscle (100 U total). In a small minority of our patients, the temporalis muscle also needed 15-20 U per side as well. Clinical improvement starts within 3-5 days, and patients can expect to have relaxation of the muscle and decreased pain for 6 months. Side effects include mild swelling and bruising. Rarely, if the injection is not performed properly, the risorius muscle may be paralyzed, leading to an asymmetric smile. In addition, if the botulinum toxin is underdosed, the pain may not completely subside and the patient may report some symptoms returning within a couple of weeks of the initial treatment. Most patients also report thinning of the face and jaw, which is a much anticipated and appreciated result. Masseter hypertrophy with and without bruxism is treated similarly with botulinum toxin to sculpt the lower face.

Bruxism is a growing problem leading to facial pain, headaches, migraines, and significant dental pathology. Traditional treatments have been ineffective at treating the pain and masseter hypertrophy associated with chronic grinding and clenching. Botulinum toxin is a safe, effective, treatment with little downtime or side effects for treating both the neurogenic and muscular components of bruxism.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Wayli H. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017 Jan 1;9(1):e112-e117.

Asutay F et al. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:6264146. doi: 10.1155/2017/6264146.

Lee SJ et al. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Jan;89(1):16-23.

Santamato A et al. J Chiropr Med. 2010 Sep;9(3):132-7.

Shetty S et al. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010 Sep;10(3):141-8.

Tan EK et al. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Feb;131(2):211-6.

Bruxism is grinding and clenching of the teeth with unconscious contractions of the temporal and masseter muscles while awake or during sleep. Bruxism occurs in 8%-16% of the population and is often an underdiagnosed condition that not only leads to dental problems but also to pain in the teeth, jaw, temporomandibular joint, and neck; headaches; and potentially, to tooth loss.

Although the pathogenesis of bruxism remains unclear, multiple factors, such as physical or psychological stress, malocclusion, sleep disorders and medication side effects, can cause bruxism. Treatment can be difficult given psychogenic and neurogenic components, and bruxism can be resistant to medical and behavioral therapy. There are various treatment options for bruxism, including oral splints; medications, such as muscle relaxants; antidepressants; and botulinum toxin. Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin injections into the masseter and temporalis muscles result in relaxation of the muscles and improvement of bruxism and the pain associated with chronic clenching and grinding.

In a recent study by Al-Wayli, 50 subjects who reported nocturnal bruxism were randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus conventional treatment (pharmacotherapy or oral splints). After 3 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year, patients who received botulinum toxin had significantly less pain after only one treatment than did the traditional treatment group. Similarly, in a study by Lee et al., subjects randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus a placebo saline injections showed not only decreased pain but also decreased bruxism seen with nocturnal electromyography.

In our clinic, Botulinum toxin when injected into the temporalis and masseter muscles also helps with tension headaches and migraines related to clenching of the jaw. Albeit effective, the dose of botulinum toxin used in the aforementioned studies ranged between 25 U and 40 U of botulinum toxin and were lower than what we have found to be effective. Our patients receive 50 U botulinum toxin in each masseter muscle (100 U total). In a small minority of our patients, the temporalis muscle also needed 15-20 U per side as well. Clinical improvement starts within 3-5 days, and patients can expect to have relaxation of the muscle and decreased pain for 6 months. Side effects include mild swelling and bruising. Rarely, if the injection is not performed properly, the risorius muscle may be paralyzed, leading to an asymmetric smile. In addition, if the botulinum toxin is underdosed, the pain may not completely subside and the patient may report some symptoms returning within a couple of weeks of the initial treatment. Most patients also report thinning of the face and jaw, which is a much anticipated and appreciated result. Masseter hypertrophy with and without bruxism is treated similarly with botulinum toxin to sculpt the lower face.

Bruxism is a growing problem leading to facial pain, headaches, migraines, and significant dental pathology. Traditional treatments have been ineffective at treating the pain and masseter hypertrophy associated with chronic grinding and clenching. Botulinum toxin is a safe, effective, treatment with little downtime or side effects for treating both the neurogenic and muscular components of bruxism.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Wayli H. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017 Jan 1;9(1):e112-e117.

Asutay F et al. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:6264146. doi: 10.1155/2017/6264146.

Lee SJ et al. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Jan;89(1):16-23.

Santamato A et al. J Chiropr Med. 2010 Sep;9(3):132-7.

Shetty S et al. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010 Sep;10(3):141-8.

Tan EK et al. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Feb;131(2):211-6.

Bruxism is grinding and clenching of the teeth with unconscious contractions of the temporal and masseter muscles while awake or during sleep. Bruxism occurs in 8%-16% of the population and is often an underdiagnosed condition that not only leads to dental problems but also to pain in the teeth, jaw, temporomandibular joint, and neck; headaches; and potentially, to tooth loss.

Although the pathogenesis of bruxism remains unclear, multiple factors, such as physical or psychological stress, malocclusion, sleep disorders and medication side effects, can cause bruxism. Treatment can be difficult given psychogenic and neurogenic components, and bruxism can be resistant to medical and behavioral therapy. There are various treatment options for bruxism, including oral splints; medications, such as muscle relaxants; antidepressants; and botulinum toxin. Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin injections into the masseter and temporalis muscles result in relaxation of the muscles and improvement of bruxism and the pain associated with chronic clenching and grinding.

In a recent study by Al-Wayli, 50 subjects who reported nocturnal bruxism were randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus conventional treatment (pharmacotherapy or oral splints). After 3 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year, patients who received botulinum toxin had significantly less pain after only one treatment than did the traditional treatment group. Similarly, in a study by Lee et al., subjects randomized to receive botulinum toxin versus a placebo saline injections showed not only decreased pain but also decreased bruxism seen with nocturnal electromyography.

In our clinic, Botulinum toxin when injected into the temporalis and masseter muscles also helps with tension headaches and migraines related to clenching of the jaw. Albeit effective, the dose of botulinum toxin used in the aforementioned studies ranged between 25 U and 40 U of botulinum toxin and were lower than what we have found to be effective. Our patients receive 50 U botulinum toxin in each masseter muscle (100 U total). In a small minority of our patients, the temporalis muscle also needed 15-20 U per side as well. Clinical improvement starts within 3-5 days, and patients can expect to have relaxation of the muscle and decreased pain for 6 months. Side effects include mild swelling and bruising. Rarely, if the injection is not performed properly, the risorius muscle may be paralyzed, leading to an asymmetric smile. In addition, if the botulinum toxin is underdosed, the pain may not completely subside and the patient may report some symptoms returning within a couple of weeks of the initial treatment. Most patients also report thinning of the face and jaw, which is a much anticipated and appreciated result. Masseter hypertrophy with and without bruxism is treated similarly with botulinum toxin to sculpt the lower face.

Bruxism is a growing problem leading to facial pain, headaches, migraines, and significant dental pathology. Traditional treatments have been ineffective at treating the pain and masseter hypertrophy associated with chronic grinding and clenching. Botulinum toxin is a safe, effective, treatment with little downtime or side effects for treating both the neurogenic and muscular components of bruxism.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Al-Wayli H. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017 Jan 1;9(1):e112-e117.

Asutay F et al. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:6264146. doi: 10.1155/2017/6264146.

Lee SJ et al. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Jan;89(1):16-23.

Santamato A et al. J Chiropr Med. 2010 Sep;9(3):132-7.

Shetty S et al. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010 Sep;10(3):141-8.

Tan EK et al. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Feb;131(2):211-6.

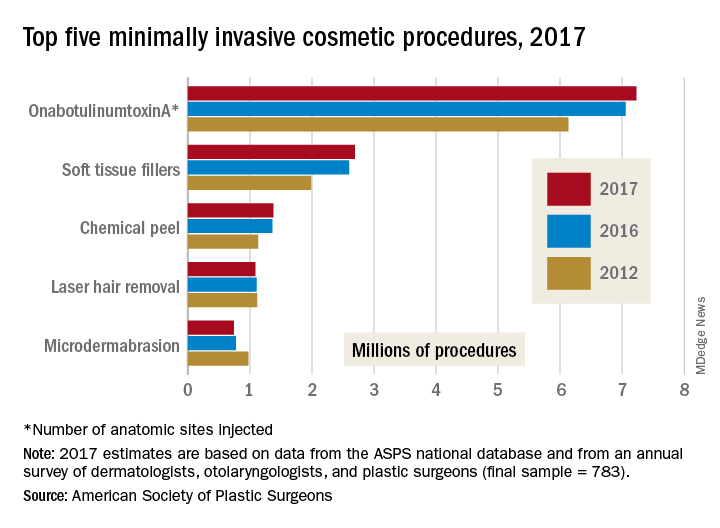

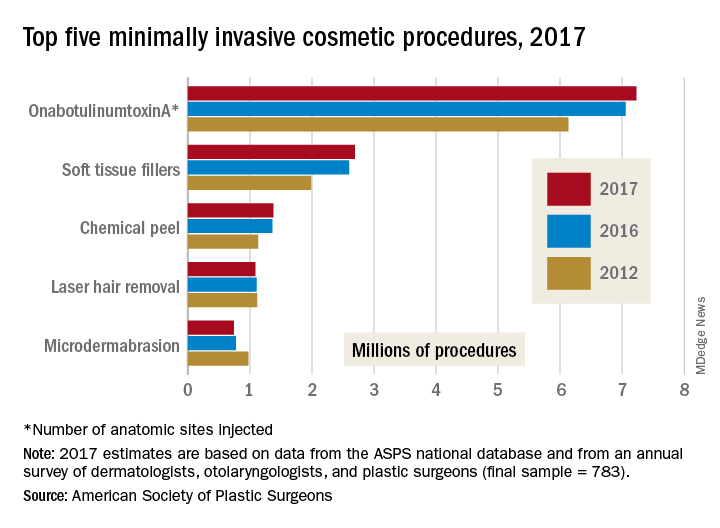

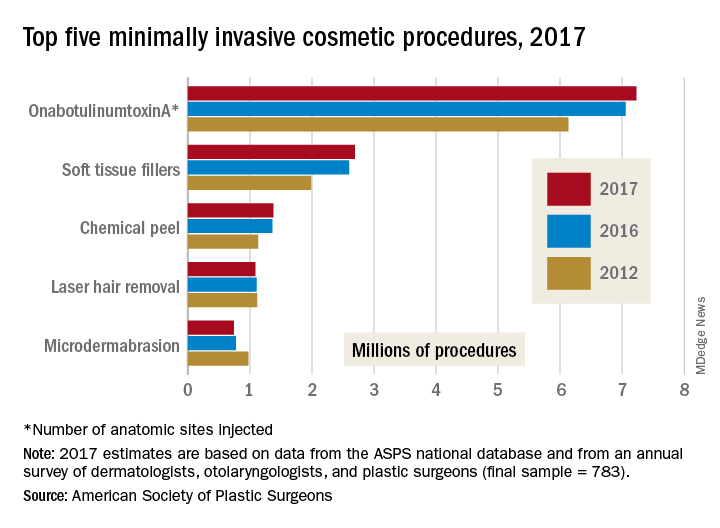

Cosmetic surgery patients want beauty ... and more

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

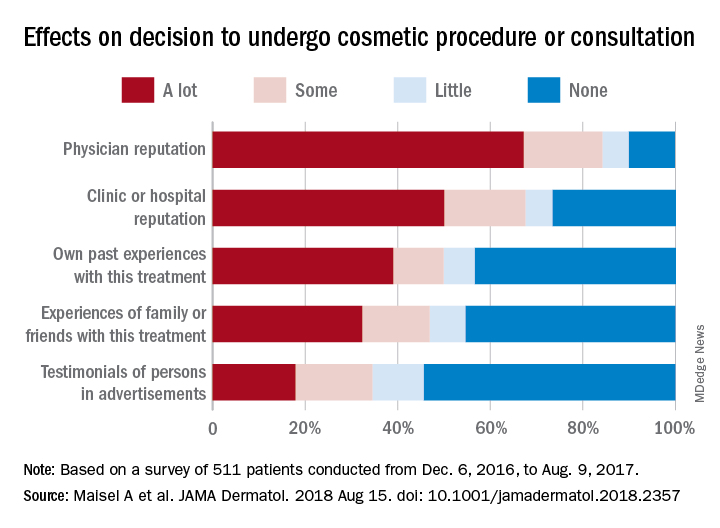

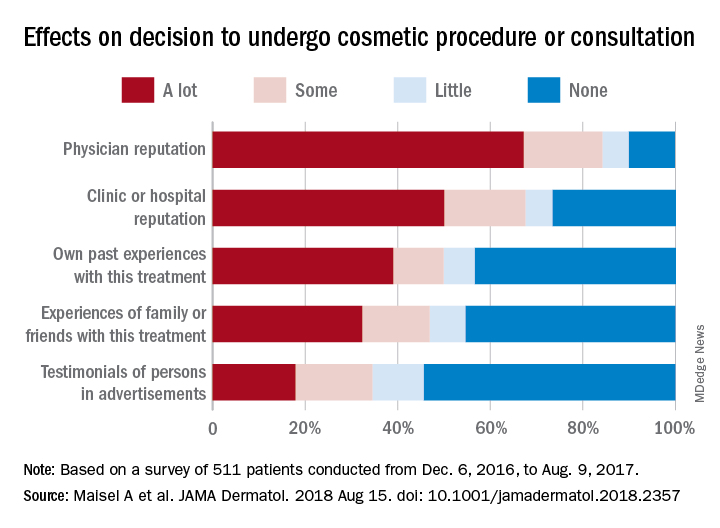

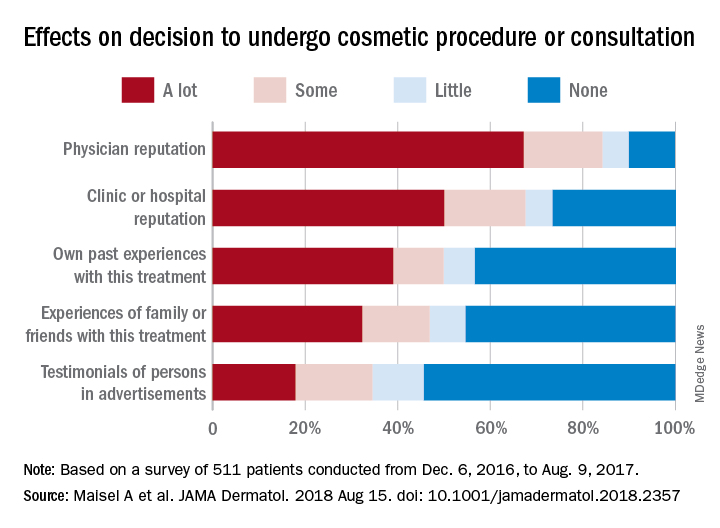

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

but motives involving mental and social well-being and physical health are common as well, according to a prospective national study involving more than 500 patients.

“Cosmetic procedures may also be necessary to correct significant physical disfigurement interfering with work or daily living. Most patients were concerned with how they looked at work and in protecting their physical health, and for some, this motive was the most important. Together, these data add to the growing body of evidence that treatments aimed at improving physical appearance can treat significant physical and psychological illness,” Amanda L. Maisel, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and her associates wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Among the motives related to appearance, 88.5% of patients said that they “wanted to look better, prettier, or more attractive for themselves,” compared with 64.4% who wanted to look good for others. Patients also were interested in “looking younger or fresher” (83.4%) and having “clear-looking or beautiful skin” (81.4%), the investigators said.

The most common mental or emotional motive was increased self-confidence (69.5%), followed by the desire to “feel happier or better overall or improve quality of life” at 67.2% and to “treat oneself, feel rewarded, or celebrate” at 61.3%. As for social well-being, 56.6% of patients “reported wanting to look good when running into people they knew” and 50.3% reported that they wanted “to feel less self-conscious around others.”

The leading motive involving physical health was “preventing worsening of their condition/symptoms,” which was reported by 53.3% of patients, the investigators reported.

They also examined how reputation and experience influenced patients’ decision to have cosmetic surgery. When asked to what degree a physician’s reputation affected their decision, 67.2% of respondents said a lot, 17% said that it had some effect, 5.7% said it had little effect, and 10% said none. Half of the patients surveyed said the clinic or hospital’s reputation had a lot of influence on their decision, compared with 39% for their own past experiences, 32.2% for experiences of family or friends, and 17.9% for testimonials of persons in advertisements, the researchers said.

The survey was conducted from Dec. 4, 2016, to Aug. 9, 2017, at 2 academic and 11 private dermatology practices. A total of 511 patients were involved, although not all individuals answered every question, so sample sizes varied. The study was supported by a research grant from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The senior investigator reported consulting for Pulse Biosciences that was unrelated to this research and being principal investigator for studies funded in part by Regeneron.

SOURCE: Maisel A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Laser Scar Management: Focused and High-Intensity Medical Exchange in Vietnam

Over the last decade the treatment of traumatic scars with lasers has emerged as a core component of multidisciplinary management. Military dermatologists have played a fundamental role in this shift by helping to develop new applications for existing technology and promulgate the techniques to reach additional providers and patients. Beyond scar management, the repurposing of adjunctive procedural techniques, such as sweat and hair reduction in amputees, also promises to enhance rehabilitation for many patients.

International engagement is a prominent and highly attractive feature of military practice, and military dermatologists routinely participate in disaster response missions, such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake,1 and ongoing planned operations, such as Pacific Partnership in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region led by the US Navy.2 In this article, I present a military perspective on the emerging niche of trauma dermatology and outline my more than 5 years of experience leveraging these skills to lead a multidisciplinary exchange in restorative medicine and burn scar management in Vietnam.

Trauma Dermatology

Over the course of the last decade, traumatic scar management has emerged as a staple of dermatologic surgery practice in some centers. Dermatologists hold the key to increasing patient access to effective outpatient care for symptomatic traumatic scars and other related issues using devices and techniques initially conceived for cosmetic applications.3 A major impetus for the considerable remodeling in our collective thoughts about traumatic scar management was the emergence of fractional laser technology in the mid-2000s. The remarkable, safe, reproducible, and durable benefits of fractional laser treatment of various scar types have created substantial momentum in recent years. The Naval Medical Center San Diego in California houses 1 of 3 centers of excellence in rehabilitation in the US military. Mastery of minimally invasive procedures to manage scars and other issues associated with trauma for the first time has established dermatologists as important partners in the overall rehabilitative effort.

My perspective on laser scar management has been previously described.4,5 Ablative fractional laser resurfacing is the backbone of rehabilitative scar management.6 Although the literature in this field is still relatively immature, higher-quality studies are accumulating rapidly as the burn and surgical communities adopt the procedure more widely.7-10 A considerable step forward in the dissemination of the procedure occurred recently with the development of category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for ablative laser treatment of traumatic scars.11 Category III CPT codes are temporary codes used for emerging procedures that have not yet been deemed medically necessary. Although individual insurance carriers can determine whether to cover these procedures and the corresponding level of reimbursement, regular use is important for ultimate elevation to category I codes by the American Medical Association over a 5-year observation period. The CPT codes 0479T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; first 100 cm2 or part thereof, or 1% of body surface area of infants and children) and 0480T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; each additional 100 cm2, or each additional 1% of body surface area of infants and children, or part thereof [list separately in addition to code for primary procedure]) are examples of these category III codes.11

Nonablative fractional lasers; vascular-specific devices for erythematous scars; and long- and short-pulsed pigment-specific devices for hair and traumatic tattoo treatment, respectively, round out the commonly used laser platforms. For example, laser hair reduction can help improve the fit and comfort of prosthetic devices and has been shown to improve the overall quality of life for amputees.12 Botulinum toxin can be an important component of treatment of excessive sweating induced by occlusive liners in prosthetics, and microwave eccrine ablation is an emerging potential option for longer-lasting sweat reduction in this population.13-15 In addition to providing direct dermatology care and education, having members of the specialty in uniform has been a key to adopting new practical solutions to unsolved problems.

Pacific Partnership

Pacific Partnership is the largest annual multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster preparedness mission in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region.16 It was started in 2006 following the tsunami that devastated parts of South and Southeast Asia in 2004. The recently concluded Pacific Partnership 2018 marked the 13th iteration of the annual mission led by the US Navy in collaboration with other partner nations, which in 2018 included Japan, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Singapore, Korea, and Peru, as well as nongovernmental organizations and international governmental agencies. Host nation mission locations vary somewhat from year to year, but 2018 included visits of the hospital ship USNS Mercy and more than 800 personnel to Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Medical/dental, engineering, and veterinary teams join with their counterparts in each host nation to conduct civic action projects, community health exchanges, medical care, and disaster response training activities.16

Rehabilitation As a Vehicle for Medical Exchange

Since approximately 2012 there has been an evolving paradigm in Pacific Partnership from an emphasis on maximizing direct patient care in changing locations to one focused on building lasting partnerships through subject matter expert exchange. Multidisciplinary scar management, including surgical and laser scar revision and physical and occupational therapy, is a very promising model for engagement. Potential advantages of this type of exchange include the following: developing nations have relatively high rates of burns and other forms of trauma as well as uneven access to acute and ongoing rehabilitative care; patients often are otherwise healthy and young; results are frequently profound and readily demonstrable; and it is a skill set that has become highly developed in the military system. Just as dermatologists are illustrating their utility in trauma rehabilitation at home, these procedural skills provide fertile ground for exchange overseas.

The Overseas Humanitarian Assistance Shared Information System is an online platform that allows users to apply for grants under the Asia-Pacific Regional Initiative. In 2013, I started the Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange with a grant under this program. A multidisciplinary team representing the specialties of dermatology, hand surgery, plastic surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and pulmonary critical care participated in the 2013 Asia Pacific Burn Congress hosted by the National Institute of Burns (NIB) in Hanoi, Vietnam, and then followed up with didactics and patient care alongside Vietnamese physicians in the management of disfiguring and debilitating scars from burns and other trauma. This pilot project consisted of three 2- to 3-week phases: 2 at the NIB in Hanoi and 1 with a delegation from the NIB visiting the Naval Medical Center San Diego. When initial project funds expired in 2014, the exchange was absorbed into Pacific Partnership 2014, which began a string of 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership engagements at Da Nang General Hospital in Vietnam. The 2 most recent exchanges, including the exchange associated with Pacific Partnership 2018, have taken place at Khanh Hoa General Hospital in Nha Trang, Vietnam. During this time the team has grown to include physical and occupational therapists as well as a wound care nurse.

The Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange consists of side-by-side laser and surgical scar revision performed with our Vietnamese hosts in their own hospital. Our Vietnamese partners perform a large volume of reconstructive surgeries in their usual practice, so it truly has been a bilateral exchange incorporating some advanced technology and techniques with an emphasis on longitudinal multidisciplinary care. Importantly, the procedures are supplemented with preoperative and postoperative care as well as instruction provided by physical and occupational therapy and wound care professionals working alongside host nation support staff. Because the areas of involvement often are extensive and a patient may only be seen once in this setting, laser and surgical procedures often are performed concurrently in the host nation operating room. Anesthesia support is provided by the host nation. Basic consumable surgical supplies (eg, sutures, gloves, marking pens, staplers) are supplemented with mission funds. Special adjuncts for the most severe contractures have included negative pressure wound therapy and a collagen-based bilayer matrix wound dressing. Laser treatments have been performed on the vast majority of patients with an ablative fractional CO2 laser and laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroid in hypertrophic areas. Of note, use of the laser has been provided to our hosts by the manufacturer for each of the 7 iterations of the exchange, and the wound dressing manufacturer also has donated some of their product to the exchange through the nongovernmental organization Project Hope for 2 missions. To date, more than 300 patients have safely received life-changing treatment during the exchange, with some receiving multiple treatments (Figure). Although multiple treatments over time are ideal, even a single treatment session can result in considerable and lasting improvements in function and symptoms.17 The hospital ship USNS Mercy has the same laser technology and has brought advanced scar treatment techniques to the far corners of the Pacific.

Measuring overall success—treatment and international relations—in this setting can be challenging. On an individual patient level, the benefits of restoring the ability to walk and work as well as reducing pain and itching are manifest and transformative for both the patient and family; however, aggregating this information into high-quality outcome data is difficult given the heterogeneous nature of traumatic injuries, which is compounded in the setting of international engagement where the intersection between patient and visiting provider may be singular or difficult to predict, funding is limited, language frequently is a barrier, and documentation, privacy, and medical research guidelines may be unfamiliar or contradictory. The cumulative impact of these types of exchanges on the relationship between nations also is critical but difficult to measure. It is common sense that deepening personal and professional relationships in the medical setting over time can increase trust and mutual understanding, perhaps setting the stage for broader engagement in other more sensitive areas. Trust and understanding are rather nebulous concepts, but earlier this year marked the first visit of an American aircraft carrier to Da Nang since 1975, following 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership missions in the same city, which does carry the patina of successful engagement on a systemic level.

Final Thoughts

Based on my personal experience, I provide the following tips for building a successful, focused, long-term medical exchange.

- Leverage your strengths and respect the strengths and style of practice of your hosts. A mind-set of exchange and not simply humanitarian care will be more successful. Your hosts are experts in a style of practice adapted to their surroundings and introducing new techniques that are grounded in the local practice patterns are more likely to be perpetuated.

- Collaboration with nongovernmental organizations and industry can be extremely helpful. Military and governmental organizations often are limited in funding, in the ways they can spend available funding, and in the receipt of donations. Appropriate coordination with civilian entities can elevate the exchange considerably by adding expertise and available assets as well as broadening the overall impact.

- Engage the support staff as well as the physicians. You will leverage contact with families and enhance care over the long-term.

- The benefits of multiple interactions over time are manifest, for both the patients and the participants. Personal and professional relationships are intertwined and naturally mature over time. Go for singles and doubles first before swinging for the fences.

- Multidisciplinary work overseas informs and enhances collaboration at home.

- Adding regional experts in international research and assessment to these specialized medical teams may better capture the impact of future exchanges of any flavor.

- The model of creating a focused exchange with independent funding followed by incorporation of successful concepts into larger missions seems to be a worthy and reproducible approach for future projects of any variety.

- Galeckas K. Dermatology aboard the USNS Comfort: disaster relief operations in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:15-19.

- Satter EK. The role of the dermatologist on military humanitarian missions. Cutis. 2010;85:85-89.

- Miletta NR, Donelan MB, Hivnor CM. Management of trauma and burn scars; the dermatologist's role in expanding patient access to care. Cutis. 2017;100:18-20.

- Shumaker PR. Laser treatment of traumatic scars: a military perspective. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:17-23.

- Shumaker PR, Beachkofsky T, Basnett A, et al. A military perspective. In: Krakowski AC, Shumaker PR, eds. The Scar Book: Formation, Mitigation, Rehabilitation and Prevention. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:327-338.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Greeson E, et al. Consensus report: laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional resurfacing. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Hultman CS, Friedstat JS, Edkins RE, et al. Laser resurfacing and remodeling of hypertrophic burn scars: the results of a large, prospective, before and after cohort study, with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg. 2014;260:519-532.

- Blome-Eberwein S, Gogal C, Weiss MJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of fractional CO2 laser treatment of mature burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:379-387.

- Issler-Fisher AC, Fisher OM, Smialkowski AO, et al. Ablative fractional CO2 laser for burn scar reconstruction: an extensive subjective and objective short-term outcome analysis of a prospective treatment cohort. Burns. 2017;43:573-582.

- Zuccaro J, Zlolkowski N, Fish J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of laser therapy for hypertrophic burn scars. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:767-779.

- Miller A. CPT 2018: What's new, part 2. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2018/january/cpt-2018-whats-new-part-2. Accessed July 24, 2018.

- Miletta NR, Kim S, Lezanski-Gujda A, et al. Improving health-related quality of life in wounded warriors: the promising benefits of laser hair removal to the residual limb-prosthetic interface. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1182-1187.

- Gratrix M, Hivnor C. Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis in patients with prosthetic limbs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1314-1315.

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- USNS Mercy deploys in support of Pacific Partnership 2018 [news release]. Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; February 26, 2018. https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1450292/usns-mercy-deploys-in-support-of-pacific-partnership-2018/. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Burns C, Basnett A, Valentine J, et al. Ablative fractional resurfacing: a powerful tool to help restore form and function during international medical exchange. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:471-474.

Over the last decade the treatment of traumatic scars with lasers has emerged as a core component of multidisciplinary management. Military dermatologists have played a fundamental role in this shift by helping to develop new applications for existing technology and promulgate the techniques to reach additional providers and patients. Beyond scar management, the repurposing of adjunctive procedural techniques, such as sweat and hair reduction in amputees, also promises to enhance rehabilitation for many patients.

International engagement is a prominent and highly attractive feature of military practice, and military dermatologists routinely participate in disaster response missions, such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake,1 and ongoing planned operations, such as Pacific Partnership in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region led by the US Navy.2 In this article, I present a military perspective on the emerging niche of trauma dermatology and outline my more than 5 years of experience leveraging these skills to lead a multidisciplinary exchange in restorative medicine and burn scar management in Vietnam.

Trauma Dermatology

Over the course of the last decade, traumatic scar management has emerged as a staple of dermatologic surgery practice in some centers. Dermatologists hold the key to increasing patient access to effective outpatient care for symptomatic traumatic scars and other related issues using devices and techniques initially conceived for cosmetic applications.3 A major impetus for the considerable remodeling in our collective thoughts about traumatic scar management was the emergence of fractional laser technology in the mid-2000s. The remarkable, safe, reproducible, and durable benefits of fractional laser treatment of various scar types have created substantial momentum in recent years. The Naval Medical Center San Diego in California houses 1 of 3 centers of excellence in rehabilitation in the US military. Mastery of minimally invasive procedures to manage scars and other issues associated with trauma for the first time has established dermatologists as important partners in the overall rehabilitative effort.

My perspective on laser scar management has been previously described.4,5 Ablative fractional laser resurfacing is the backbone of rehabilitative scar management.6 Although the literature in this field is still relatively immature, higher-quality studies are accumulating rapidly as the burn and surgical communities adopt the procedure more widely.7-10 A considerable step forward in the dissemination of the procedure occurred recently with the development of category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for ablative laser treatment of traumatic scars.11 Category III CPT codes are temporary codes used for emerging procedures that have not yet been deemed medically necessary. Although individual insurance carriers can determine whether to cover these procedures and the corresponding level of reimbursement, regular use is important for ultimate elevation to category I codes by the American Medical Association over a 5-year observation period. The CPT codes 0479T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; first 100 cm2 or part thereof, or 1% of body surface area of infants and children) and 0480T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; each additional 100 cm2, or each additional 1% of body surface area of infants and children, or part thereof [list separately in addition to code for primary procedure]) are examples of these category III codes.11

Nonablative fractional lasers; vascular-specific devices for erythematous scars; and long- and short-pulsed pigment-specific devices for hair and traumatic tattoo treatment, respectively, round out the commonly used laser platforms. For example, laser hair reduction can help improve the fit and comfort of prosthetic devices and has been shown to improve the overall quality of life for amputees.12 Botulinum toxin can be an important component of treatment of excessive sweating induced by occlusive liners in prosthetics, and microwave eccrine ablation is an emerging potential option for longer-lasting sweat reduction in this population.13-15 In addition to providing direct dermatology care and education, having members of the specialty in uniform has been a key to adopting new practical solutions to unsolved problems.

Pacific Partnership

Pacific Partnership is the largest annual multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster preparedness mission in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region.16 It was started in 2006 following the tsunami that devastated parts of South and Southeast Asia in 2004. The recently concluded Pacific Partnership 2018 marked the 13th iteration of the annual mission led by the US Navy in collaboration with other partner nations, which in 2018 included Japan, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Singapore, Korea, and Peru, as well as nongovernmental organizations and international governmental agencies. Host nation mission locations vary somewhat from year to year, but 2018 included visits of the hospital ship USNS Mercy and more than 800 personnel to Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Medical/dental, engineering, and veterinary teams join with their counterparts in each host nation to conduct civic action projects, community health exchanges, medical care, and disaster response training activities.16

Rehabilitation As a Vehicle for Medical Exchange

Since approximately 2012 there has been an evolving paradigm in Pacific Partnership from an emphasis on maximizing direct patient care in changing locations to one focused on building lasting partnerships through subject matter expert exchange. Multidisciplinary scar management, including surgical and laser scar revision and physical and occupational therapy, is a very promising model for engagement. Potential advantages of this type of exchange include the following: developing nations have relatively high rates of burns and other forms of trauma as well as uneven access to acute and ongoing rehabilitative care; patients often are otherwise healthy and young; results are frequently profound and readily demonstrable; and it is a skill set that has become highly developed in the military system. Just as dermatologists are illustrating their utility in trauma rehabilitation at home, these procedural skills provide fertile ground for exchange overseas.

The Overseas Humanitarian Assistance Shared Information System is an online platform that allows users to apply for grants under the Asia-Pacific Regional Initiative. In 2013, I started the Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange with a grant under this program. A multidisciplinary team representing the specialties of dermatology, hand surgery, plastic surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and pulmonary critical care participated in the 2013 Asia Pacific Burn Congress hosted by the National Institute of Burns (NIB) in Hanoi, Vietnam, and then followed up with didactics and patient care alongside Vietnamese physicians in the management of disfiguring and debilitating scars from burns and other trauma. This pilot project consisted of three 2- to 3-week phases: 2 at the NIB in Hanoi and 1 with a delegation from the NIB visiting the Naval Medical Center San Diego. When initial project funds expired in 2014, the exchange was absorbed into Pacific Partnership 2014, which began a string of 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership engagements at Da Nang General Hospital in Vietnam. The 2 most recent exchanges, including the exchange associated with Pacific Partnership 2018, have taken place at Khanh Hoa General Hospital in Nha Trang, Vietnam. During this time the team has grown to include physical and occupational therapists as well as a wound care nurse.

The Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange consists of side-by-side laser and surgical scar revision performed with our Vietnamese hosts in their own hospital. Our Vietnamese partners perform a large volume of reconstructive surgeries in their usual practice, so it truly has been a bilateral exchange incorporating some advanced technology and techniques with an emphasis on longitudinal multidisciplinary care. Importantly, the procedures are supplemented with preoperative and postoperative care as well as instruction provided by physical and occupational therapy and wound care professionals working alongside host nation support staff. Because the areas of involvement often are extensive and a patient may only be seen once in this setting, laser and surgical procedures often are performed concurrently in the host nation operating room. Anesthesia support is provided by the host nation. Basic consumable surgical supplies (eg, sutures, gloves, marking pens, staplers) are supplemented with mission funds. Special adjuncts for the most severe contractures have included negative pressure wound therapy and a collagen-based bilayer matrix wound dressing. Laser treatments have been performed on the vast majority of patients with an ablative fractional CO2 laser and laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroid in hypertrophic areas. Of note, use of the laser has been provided to our hosts by the manufacturer for each of the 7 iterations of the exchange, and the wound dressing manufacturer also has donated some of their product to the exchange through the nongovernmental organization Project Hope for 2 missions. To date, more than 300 patients have safely received life-changing treatment during the exchange, with some receiving multiple treatments (Figure). Although multiple treatments over time are ideal, even a single treatment session can result in considerable and lasting improvements in function and symptoms.17 The hospital ship USNS Mercy has the same laser technology and has brought advanced scar treatment techniques to the far corners of the Pacific.

Measuring overall success—treatment and international relations—in this setting can be challenging. On an individual patient level, the benefits of restoring the ability to walk and work as well as reducing pain and itching are manifest and transformative for both the patient and family; however, aggregating this information into high-quality outcome data is difficult given the heterogeneous nature of traumatic injuries, which is compounded in the setting of international engagement where the intersection between patient and visiting provider may be singular or difficult to predict, funding is limited, language frequently is a barrier, and documentation, privacy, and medical research guidelines may be unfamiliar or contradictory. The cumulative impact of these types of exchanges on the relationship between nations also is critical but difficult to measure. It is common sense that deepening personal and professional relationships in the medical setting over time can increase trust and mutual understanding, perhaps setting the stage for broader engagement in other more sensitive areas. Trust and understanding are rather nebulous concepts, but earlier this year marked the first visit of an American aircraft carrier to Da Nang since 1975, following 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership missions in the same city, which does carry the patina of successful engagement on a systemic level.

Final Thoughts

Based on my personal experience, I provide the following tips for building a successful, focused, long-term medical exchange.

- Leverage your strengths and respect the strengths and style of practice of your hosts. A mind-set of exchange and not simply humanitarian care will be more successful. Your hosts are experts in a style of practice adapted to their surroundings and introducing new techniques that are grounded in the local practice patterns are more likely to be perpetuated.

- Collaboration with nongovernmental organizations and industry can be extremely helpful. Military and governmental organizations often are limited in funding, in the ways they can spend available funding, and in the receipt of donations. Appropriate coordination with civilian entities can elevate the exchange considerably by adding expertise and available assets as well as broadening the overall impact.

- Engage the support staff as well as the physicians. You will leverage contact with families and enhance care over the long-term.

- The benefits of multiple interactions over time are manifest, for both the patients and the participants. Personal and professional relationships are intertwined and naturally mature over time. Go for singles and doubles first before swinging for the fences.

- Multidisciplinary work overseas informs and enhances collaboration at home.

- Adding regional experts in international research and assessment to these specialized medical teams may better capture the impact of future exchanges of any flavor.

- The model of creating a focused exchange with independent funding followed by incorporation of successful concepts into larger missions seems to be a worthy and reproducible approach for future projects of any variety.

Over the last decade the treatment of traumatic scars with lasers has emerged as a core component of multidisciplinary management. Military dermatologists have played a fundamental role in this shift by helping to develop new applications for existing technology and promulgate the techniques to reach additional providers and patients. Beyond scar management, the repurposing of adjunctive procedural techniques, such as sweat and hair reduction in amputees, also promises to enhance rehabilitation for many patients.

International engagement is a prominent and highly attractive feature of military practice, and military dermatologists routinely participate in disaster response missions, such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake,1 and ongoing planned operations, such as Pacific Partnership in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region led by the US Navy.2 In this article, I present a military perspective on the emerging niche of trauma dermatology and outline my more than 5 years of experience leveraging these skills to lead a multidisciplinary exchange in restorative medicine and burn scar management in Vietnam.

Trauma Dermatology

Over the course of the last decade, traumatic scar management has emerged as a staple of dermatologic surgery practice in some centers. Dermatologists hold the key to increasing patient access to effective outpatient care for symptomatic traumatic scars and other related issues using devices and techniques initially conceived for cosmetic applications.3 A major impetus for the considerable remodeling in our collective thoughts about traumatic scar management was the emergence of fractional laser technology in the mid-2000s. The remarkable, safe, reproducible, and durable benefits of fractional laser treatment of various scar types have created substantial momentum in recent years. The Naval Medical Center San Diego in California houses 1 of 3 centers of excellence in rehabilitation in the US military. Mastery of minimally invasive procedures to manage scars and other issues associated with trauma for the first time has established dermatologists as important partners in the overall rehabilitative effort.

My perspective on laser scar management has been previously described.4,5 Ablative fractional laser resurfacing is the backbone of rehabilitative scar management.6 Although the literature in this field is still relatively immature, higher-quality studies are accumulating rapidly as the burn and surgical communities adopt the procedure more widely.7-10 A considerable step forward in the dissemination of the procedure occurred recently with the development of category III Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for ablative laser treatment of traumatic scars.11 Category III CPT codes are temporary codes used for emerging procedures that have not yet been deemed medically necessary. Although individual insurance carriers can determine whether to cover these procedures and the corresponding level of reimbursement, regular use is important for ultimate elevation to category I codes by the American Medical Association over a 5-year observation period. The CPT codes 0479T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; first 100 cm2 or part thereof, or 1% of body surface area of infants and children) and 0480T (fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars for functional improvement; each additional 100 cm2, or each additional 1% of body surface area of infants and children, or part thereof [list separately in addition to code for primary procedure]) are examples of these category III codes.11

Nonablative fractional lasers; vascular-specific devices for erythematous scars; and long- and short-pulsed pigment-specific devices for hair and traumatic tattoo treatment, respectively, round out the commonly used laser platforms. For example, laser hair reduction can help improve the fit and comfort of prosthetic devices and has been shown to improve the overall quality of life for amputees.12 Botulinum toxin can be an important component of treatment of excessive sweating induced by occlusive liners in prosthetics, and microwave eccrine ablation is an emerging potential option for longer-lasting sweat reduction in this population.13-15 In addition to providing direct dermatology care and education, having members of the specialty in uniform has been a key to adopting new practical solutions to unsolved problems.

Pacific Partnership

Pacific Partnership is the largest annual multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster preparedness mission in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region.16 It was started in 2006 following the tsunami that devastated parts of South and Southeast Asia in 2004. The recently concluded Pacific Partnership 2018 marked the 13th iteration of the annual mission led by the US Navy in collaboration with other partner nations, which in 2018 included Japan, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Singapore, Korea, and Peru, as well as nongovernmental organizations and international governmental agencies. Host nation mission locations vary somewhat from year to year, but 2018 included visits of the hospital ship USNS Mercy and more than 800 personnel to Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Medical/dental, engineering, and veterinary teams join with their counterparts in each host nation to conduct civic action projects, community health exchanges, medical care, and disaster response training activities.16

Rehabilitation As a Vehicle for Medical Exchange

Since approximately 2012 there has been an evolving paradigm in Pacific Partnership from an emphasis on maximizing direct patient care in changing locations to one focused on building lasting partnerships through subject matter expert exchange. Multidisciplinary scar management, including surgical and laser scar revision and physical and occupational therapy, is a very promising model for engagement. Potential advantages of this type of exchange include the following: developing nations have relatively high rates of burns and other forms of trauma as well as uneven access to acute and ongoing rehabilitative care; patients often are otherwise healthy and young; results are frequently profound and readily demonstrable; and it is a skill set that has become highly developed in the military system. Just as dermatologists are illustrating their utility in trauma rehabilitation at home, these procedural skills provide fertile ground for exchange overseas.

The Overseas Humanitarian Assistance Shared Information System is an online platform that allows users to apply for grants under the Asia-Pacific Regional Initiative. In 2013, I started the Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange with a grant under this program. A multidisciplinary team representing the specialties of dermatology, hand surgery, plastic surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and pulmonary critical care participated in the 2013 Asia Pacific Burn Congress hosted by the National Institute of Burns (NIB) in Hanoi, Vietnam, and then followed up with didactics and patient care alongside Vietnamese physicians in the management of disfiguring and debilitating scars from burns and other trauma. This pilot project consisted of three 2- to 3-week phases: 2 at the NIB in Hanoi and 1 with a delegation from the NIB visiting the Naval Medical Center San Diego. When initial project funds expired in 2014, the exchange was absorbed into Pacific Partnership 2014, which began a string of 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership engagements at Da Nang General Hospital in Vietnam. The 2 most recent exchanges, including the exchange associated with Pacific Partnership 2018, have taken place at Khanh Hoa General Hospital in Nha Trang, Vietnam. During this time the team has grown to include physical and occupational therapists as well as a wound care nurse.

The Burn Scar Treatment/Restorative Medicine exchange consists of side-by-side laser and surgical scar revision performed with our Vietnamese hosts in their own hospital. Our Vietnamese partners perform a large volume of reconstructive surgeries in their usual practice, so it truly has been a bilateral exchange incorporating some advanced technology and techniques with an emphasis on longitudinal multidisciplinary care. Importantly, the procedures are supplemented with preoperative and postoperative care as well as instruction provided by physical and occupational therapy and wound care professionals working alongside host nation support staff. Because the areas of involvement often are extensive and a patient may only be seen once in this setting, laser and surgical procedures often are performed concurrently in the host nation operating room. Anesthesia support is provided by the host nation. Basic consumable surgical supplies (eg, sutures, gloves, marking pens, staplers) are supplemented with mission funds. Special adjuncts for the most severe contractures have included negative pressure wound therapy and a collagen-based bilayer matrix wound dressing. Laser treatments have been performed on the vast majority of patients with an ablative fractional CO2 laser and laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroid in hypertrophic areas. Of note, use of the laser has been provided to our hosts by the manufacturer for each of the 7 iterations of the exchange, and the wound dressing manufacturer also has donated some of their product to the exchange through the nongovernmental organization Project Hope for 2 missions. To date, more than 300 patients have safely received life-changing treatment during the exchange, with some receiving multiple treatments (Figure). Although multiple treatments over time are ideal, even a single treatment session can result in considerable and lasting improvements in function and symptoms.17 The hospital ship USNS Mercy has the same laser technology and has brought advanced scar treatment techniques to the far corners of the Pacific.

Measuring overall success—treatment and international relations—in this setting can be challenging. On an individual patient level, the benefits of restoring the ability to walk and work as well as reducing pain and itching are manifest and transformative for both the patient and family; however, aggregating this information into high-quality outcome data is difficult given the heterogeneous nature of traumatic injuries, which is compounded in the setting of international engagement where the intersection between patient and visiting provider may be singular or difficult to predict, funding is limited, language frequently is a barrier, and documentation, privacy, and medical research guidelines may be unfamiliar or contradictory. The cumulative impact of these types of exchanges on the relationship between nations also is critical but difficult to measure. It is common sense that deepening personal and professional relationships in the medical setting over time can increase trust and mutual understanding, perhaps setting the stage for broader engagement in other more sensitive areas. Trust and understanding are rather nebulous concepts, but earlier this year marked the first visit of an American aircraft carrier to Da Nang since 1975, following 4 consecutive annual Pacific Partnership missions in the same city, which does carry the patina of successful engagement on a systemic level.

Final Thoughts

Based on my personal experience, I provide the following tips for building a successful, focused, long-term medical exchange.

- Leverage your strengths and respect the strengths and style of practice of your hosts. A mind-set of exchange and not simply humanitarian care will be more successful. Your hosts are experts in a style of practice adapted to their surroundings and introducing new techniques that are grounded in the local practice patterns are more likely to be perpetuated.

- Collaboration with nongovernmental organizations and industry can be extremely helpful. Military and governmental organizations often are limited in funding, in the ways they can spend available funding, and in the receipt of donations. Appropriate coordination with civilian entities can elevate the exchange considerably by adding expertise and available assets as well as broadening the overall impact.

- Engage the support staff as well as the physicians. You will leverage contact with families and enhance care over the long-term.

- The benefits of multiple interactions over time are manifest, for both the patients and the participants. Personal and professional relationships are intertwined and naturally mature over time. Go for singles and doubles first before swinging for the fences.

- Multidisciplinary work overseas informs and enhances collaboration at home.

- Adding regional experts in international research and assessment to these specialized medical teams may better capture the impact of future exchanges of any flavor.

- The model of creating a focused exchange with independent funding followed by incorporation of successful concepts into larger missions seems to be a worthy and reproducible approach for future projects of any variety.

- Galeckas K. Dermatology aboard the USNS Comfort: disaster relief operations in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:15-19.

- Satter EK. The role of the dermatologist on military humanitarian missions. Cutis. 2010;85:85-89.

- Miletta NR, Donelan MB, Hivnor CM. Management of trauma and burn scars; the dermatologist's role in expanding patient access to care. Cutis. 2017;100:18-20.

- Shumaker PR. Laser treatment of traumatic scars: a military perspective. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:17-23.

- Shumaker PR, Beachkofsky T, Basnett A, et al. A military perspective. In: Krakowski AC, Shumaker PR, eds. The Scar Book: Formation, Mitigation, Rehabilitation and Prevention. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:327-338.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Greeson E, et al. Consensus report: laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional resurfacing. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Hultman CS, Friedstat JS, Edkins RE, et al. Laser resurfacing and remodeling of hypertrophic burn scars: the results of a large, prospective, before and after cohort study, with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg. 2014;260:519-532.

- Blome-Eberwein S, Gogal C, Weiss MJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of fractional CO2 laser treatment of mature burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:379-387.

- Issler-Fisher AC, Fisher OM, Smialkowski AO, et al. Ablative fractional CO2 laser for burn scar reconstruction: an extensive subjective and objective short-term outcome analysis of a prospective treatment cohort. Burns. 2017;43:573-582.

- Zuccaro J, Zlolkowski N, Fish J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of laser therapy for hypertrophic burn scars. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:767-779.

- Miller A. CPT 2018: What's new, part 2. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2018/january/cpt-2018-whats-new-part-2. Accessed July 24, 2018.

- Miletta NR, Kim S, Lezanski-Gujda A, et al. Improving health-related quality of life in wounded warriors: the promising benefits of laser hair removal to the residual limb-prosthetic interface. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1182-1187.

- Gratrix M, Hivnor C. Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis in patients with prosthetic limbs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1314-1315.

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- USNS Mercy deploys in support of Pacific Partnership 2018 [news release]. Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; February 26, 2018. https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1450292/usns-mercy-deploys-in-support-of-pacific-partnership-2018/. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Burns C, Basnett A, Valentine J, et al. Ablative fractional resurfacing: a powerful tool to help restore form and function during international medical exchange. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:471-474.

- Galeckas K. Dermatology aboard the USNS Comfort: disaster relief operations in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:15-19.

- Satter EK. The role of the dermatologist on military humanitarian missions. Cutis. 2010;85:85-89.

- Miletta NR, Donelan MB, Hivnor CM. Management of trauma and burn scars; the dermatologist's role in expanding patient access to care. Cutis. 2017;100:18-20.

- Shumaker PR. Laser treatment of traumatic scars: a military perspective. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:17-23.

- Shumaker PR, Beachkofsky T, Basnett A, et al. A military perspective. In: Krakowski AC, Shumaker PR, eds. The Scar Book: Formation, Mitigation, Rehabilitation and Prevention. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:327-338.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Greeson E, et al. Consensus report: laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional resurfacing. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Hultman CS, Friedstat JS, Edkins RE, et al. Laser resurfacing and remodeling of hypertrophic burn scars: the results of a large, prospective, before and after cohort study, with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg. 2014;260:519-532.

- Blome-Eberwein S, Gogal C, Weiss MJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of fractional CO2 laser treatment of mature burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:379-387.

- Issler-Fisher AC, Fisher OM, Smialkowski AO, et al. Ablative fractional CO2 laser for burn scar reconstruction: an extensive subjective and objective short-term outcome analysis of a prospective treatment cohort. Burns. 2017;43:573-582.

- Zuccaro J, Zlolkowski N, Fish J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of laser therapy for hypertrophic burn scars. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:767-779.

- Miller A. CPT 2018: What's new, part 2. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2018/january/cpt-2018-whats-new-part-2. Accessed July 24, 2018.

- Miletta NR, Kim S, Lezanski-Gujda A, et al. Improving health-related quality of life in wounded warriors: the promising benefits of laser hair removal to the residual limb-prosthetic interface. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1182-1187.

- Gratrix M, Hivnor C. Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis in patients with prosthetic limbs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1314-1315.

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- USNS Mercy deploys in support of Pacific Partnership 2018 [news release]. Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; February 26, 2018. https://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1450292/usns-mercy-deploys-in-support-of-pacific-partnership-2018/. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Burns C, Basnett A, Valentine J, et al. Ablative fractional resurfacing: a powerful tool to help restore form and function during international medical exchange. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:471-474.

Five common pitfalls of retailing skin care

Others believe that providing patients with the correct skin care product recommendations for their skin’s needs is a crucial step to improving outcomes and educating patients.

There is a wide range of challenges related to skin care retail that many physicians face. I will be running a course on Skin Care Retail at the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery meeting in October in Scottsdale, Ariz., if you want to learn more or share your opinions. I have surveyed plastic surgeons and dermatologists via LinkedIn about what they believe are some of the biggest pitfalls to retailing skin care. Here, I will share some of their insights and suggestions for overcoming these obstacles.

1. Patients are more knowledgeable about skin care than ever before

Facing an increasing number of over-the-counter skin care products available, as well as buzzwords like “organic ingredients” and “vegan,” patients are now bombarded with information from a variety of different sources. Because of this, patients come to the doctor with preconceived ideas that can affect compliance if their specific needs and beliefs are not properly addressed.

For New York plastic surgeon Sonita M. Sadio, MD, this is one of the reasons why she chooses not to sell skin care in her office.

“My practice is highly consultative, and ongoing skin care recommendations are a significant part of what I do to optimize patient outcomes,” Dr. Sadio said. “Patients are well-educated about skin care today. They know their ingredients and insist on clean formulations, free of certain ingredients, such as ‘cruelty-free’ and ‘vegan.’ Others feel deprived if they are not using an expensive product in elegant packaging. Still, others insist on drugstore favorites or ‘eco’ offerings and have their own sense of what that means. My job is to optimize the clinical outcome while also meeting these patients needs to ensure compliance.”

Not all doctors have the time, knowledge or desire to personally design each patient’s skin care regimen. Many delegate this to the staff. However, it is impossible to ensure that your staff matches patients to the proper products unless they have had extensive training on both skin care products and how to match them to the patient’s skin issues.

2. Patients are wary when the doctors sells only one product brand

Many studies have shown that, although consumers desire a choice when making purchases, they get overwhelmed if they are presented with too many options. One study showed that it is optimal to carry at least 3 brands of products. For this reason, limiting the skin care you sell to one brand or doing your own private label is not optimal.

New York dermatologist Rebecca Tamez, MD, pointed out the same problem when selling practice-specific skin care. “At my previous job, we sold skin care products directly to patients. I had no issues selling products that were readily available in drugstores or online (such as Vanicream and EltaMD). We usually sold these around the same cost as the drugstore or Amazon. However, it was harder to sell the practice-specific skin care line. I feel patients were more wary of these products.”

3. Doctors do not want to feel like salespeople

If you have read my Dermatology News columns in the past, you may know that I think it is unethical for dermatologists to not offer specific skin care advice to their patients. If patients do not get ethical and scientific recommendations from us, they will follow the advice of a friend or salesperson or purchase based on often inflated marketing claims.

Dermatologists often tell me: “I am not a cosmetic dermatologist so I do not sell skin care.” I feel strongly that general dermatologists should be giving specific written skin care recommendations for their patients too. Acne, rosacea, melasma, eczema, psoriasis, keratosis pilaris, and many other conditions will improve faster with an efficacious skin care regimen, assuming the patient is compliant with the instructions. Retailing skin care improves compliance by eliminating a few barriers to beginning the skin care regimen. I believe that the mindset of dermatologists needs to change: It is not about selling products to patients, it is about educating them on what to use and offering the products out of convenience and the desire to improve compliance.

Meadowbrook, Pa., dermatologist Michael A. Tomeo, MD, explained an obstacle faced by many dermatologists:

“I suspect, like many of my colleagues,” said Dr. Tomeo, “that I am held back in terms of salesmanship, having been trained in the traditional way. Physicians of my generation were taught to be ethical and professional and to focus on academic and clinical excellence, and salesmanship and advertising one’s services were frowned upon. It takes time to reset one’s former proclivities. Cosmeceuticals and nutraceuticals are revolutionizing the skin care world, and as experts in all things skin, we need to be well informed and offer our patients safe, effective, and cutting-edge treatments.”

4. Providers are concerned about product costs and time constraints

Providing excellent patient care and improving outcomes is at the forefront of our business, but financial concerns and time constraints prevent some doctors from offering skin care to their patients.

Rochester Hills, Mich., plastic surgeon Richard Hainer, MD, has found that “skin care is often too complex with too many products and is not very profitable.” For those reasons, Dr. Hainer has chosen not to retail skin care in his practice.

Nampa, Idaho, dermatologist Ryan S. Owsley, MD, explained that “the required minimum purchases by some of the product lines can leave the practice with expired product if it is not selling a particular line well. Cost can also be an issue for some patients in the area we are located.”

As a burn survivor and burn surgeon, Mark McDonough, MD, from Orlando “has a long history with skin care and rejuvenation. I did have a private label skin care line, including a moisturizer, a hydroquinone product, a retinol cream, and a sunscreen,” Dr. McDonough said. “However, and regrettably, I have not kept up with marketing and promotion, with most of my energy invested in trauma and disease survivors through a book, a blog, and my platform through my website.”

Doing your own product line is costly and spending the time and resources to promote it is not always possible. Buying the minimum order of products is often expensive, and you will not be able to sell them without a proven methodology in place. New products enter the market frequently, and it is expensive to always carry the latest technologies because new minimum orders must be met with each new brand that you add.

5. Selling skin care requires ongoing education

Properly recommending and retailing skin care involves physician, staff, and patient education. Unfortunately, most practices rely on training from the cosmeceutical sales reps who obviously have a brand bias. There is minimal unbiased “brand agnostic” skin care training for dermatologists and their staff. In fact, the AAD meeting has only a few skin care lectures in the program. Plastic surgeon Gaurav Bharti, MD, of Charlotte, N.C., explained that “motivating staff to help with retail skin care can be challenging. The first step is to get the staff familiar with the products with open discussions with the representatives. The next step has been to have the staff actually use the products and believe in them. Once they believe in the product, we have used an incentivization model that’s simple, transparent, and predictable.”

We are all too busy to spend adequate time with our patients, so it is critical that our staff be able to properly recommended skin care for us. We have to ensure that our staff is taking an ethical and scientific approach to skin care retail rather than a financial one. Rigorous staff training on how to match skin care products to skin type is the key to improving outcomes with skin care recommendations.

In a similar sense, Cincinnati plastic surgeon Richard Williams, MD, commented that “aestheticians often succumb to the desires of our patients to carry too many products in inventory, for which they do not have enough knowledge of the product’s benefits. This can be a very frustrating challenge.”

Conclusion

Although there are many obstacles to retailing skin care in your medical practice, the benefits that it provides to both your patients (improved outcomes) and your practice (increased profitability) far outweigh the challenges. I solved these pitfalls in my own practice by developing a standardized staff training program and skin care diagnostic software that is now used by over 100 medical practices. If you want to start retaining skin care, my advice is develop a training plan and a methodology for the recommendation and patient education process before you spend a lot of money on the required minimum product order. Feel free to contact me for advice. Alternatively, if you already do a great job of retailing skin care and want to provide tips to include in my American Society for Dermatologic Surgery course, contact me on LinkedIn or [email protected]. You can also find blogs I have written on skin care retail advice at STSFranchise.com.