User login

Low hyaluronidase doses may be adequate for addressing filler asymmetry

, and in some cases, slightly larger doses may move things along more rapidly, according to the authors of a small split-arm clinical trial.

“These findings offer clinicians a means to modify and fine-tune filler-associated skin contour without resorting to high-dose injections that completely remove all filler from the treatment site,” wrote the authors, led by Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology and chief of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The study, conducted during 2013-2014, analyzed the impact of various small doses of hyaluronidase on two types of fillers that had been administered into the upper inner arms of nine women (seven white, two black; mean age, 46 years). Another participant withdrew because of a fear of needles.

In one arm in each woman, researchers injected four aliquots of Juvéderm Ultra XC (0.4 mL each). Then, at 1, 2, and 3 weeks, they administered 1.5 U, 3.0 U, or 9.0 U hyaluronidase per 0.1 mL or saline control (at a constant volume of 0.1 mL) into each site. In the other arms, researchers performed the same protocol, but with Restylane-L. A 5-point scale was used to rate detectability of each site ranging from 0 (undetectable) and 1 (faintly perceptible) to 4 (“very” perceptible).

A blinded physician visually rated the effects of saline versus hyaluronidase at 4 weeks and found a significant difference between assessments of the hyaluronidase-treated sites and saline control sites at 4 weeks, favoring the hyaluronidase sites for visual detection (mean difference, 1.15; P less than .001) and palpability (mean difference, 1.22; P less than .001). Participant self-assessments at 4 weeks produced similar results for visual detection (mean difference, 0.87; P = .006) and palpability (mean difference, 1.59; P less than .001).

Similar differences favoring hyaluronidase persisted at 4 months.

The researchers also found that 9.0-U treatments of hyaluronidase led to significantly less palpability than 1.5-U treatments at 4 weeks and 4 months. The researchers noticed a larger dose-related difference for hyaluronidase for Restylane-L sites, and they noted that all the filler nodules diminished over time regardless of the study treatment.

“The clinical relevance of these findings is clear,” they concluded. “Minor filler-associated asymmetries, nodules, and textural abnormalities may be corrected safely and effectively with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase. Rather than dissolving all the offending filler, waiting, and then reinjecting fresh filler weeks or months later, dermatologists may precisely sculpt already injected excess filler by titration with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase to the desired skin contour.”

Other types of hyaluronidase may work in different ways, the study authors noted, and larger doses may be needed to treat longer-lasting types of fillers.

In an accompanying commentary, Derek H. Jones, MD, of Skin Care and Laser Physicians of Beverly Hills, Calif., praised the study, which he wrote, “proves that smaller, less-concentrated doses of hyaluronidase are capable of removing small amounts of HA [hyaluronic acid] without removing the entire implant.”

Dr. Jones added that he uses 10 U of Vitrase (hyaluronidase) for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm that he estimates should be removed. He also uses 5 U of Vitrase for each 0.1 cc of Restylane, and 30 U for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm Voluma.

“When attempting to remove smaller or partial amounts of HA implant,” he added, “I often dilute Vitrase with normal saline to go from 20 U/0.1 cc to 10 U/0.1 cc or less.”

Northwestern University funded the study. Dr. Alam, the lead author, reported various disclosures, and the university disclosed that its clinical trials branch receives various government and corporate grants. The other authors reported no disclosures. Dr. Jones disclosed serving as an investigator, consultant, and/or speaker for Allergan, Merz, and Galderma.

SOURCE: Alam M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0515.

, and in some cases, slightly larger doses may move things along more rapidly, according to the authors of a small split-arm clinical trial.

“These findings offer clinicians a means to modify and fine-tune filler-associated skin contour without resorting to high-dose injections that completely remove all filler from the treatment site,” wrote the authors, led by Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology and chief of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The study, conducted during 2013-2014, analyzed the impact of various small doses of hyaluronidase on two types of fillers that had been administered into the upper inner arms of nine women (seven white, two black; mean age, 46 years). Another participant withdrew because of a fear of needles.

In one arm in each woman, researchers injected four aliquots of Juvéderm Ultra XC (0.4 mL each). Then, at 1, 2, and 3 weeks, they administered 1.5 U, 3.0 U, or 9.0 U hyaluronidase per 0.1 mL or saline control (at a constant volume of 0.1 mL) into each site. In the other arms, researchers performed the same protocol, but with Restylane-L. A 5-point scale was used to rate detectability of each site ranging from 0 (undetectable) and 1 (faintly perceptible) to 4 (“very” perceptible).

A blinded physician visually rated the effects of saline versus hyaluronidase at 4 weeks and found a significant difference between assessments of the hyaluronidase-treated sites and saline control sites at 4 weeks, favoring the hyaluronidase sites for visual detection (mean difference, 1.15; P less than .001) and palpability (mean difference, 1.22; P less than .001). Participant self-assessments at 4 weeks produced similar results for visual detection (mean difference, 0.87; P = .006) and palpability (mean difference, 1.59; P less than .001).

Similar differences favoring hyaluronidase persisted at 4 months.

The researchers also found that 9.0-U treatments of hyaluronidase led to significantly less palpability than 1.5-U treatments at 4 weeks and 4 months. The researchers noticed a larger dose-related difference for hyaluronidase for Restylane-L sites, and they noted that all the filler nodules diminished over time regardless of the study treatment.

“The clinical relevance of these findings is clear,” they concluded. “Minor filler-associated asymmetries, nodules, and textural abnormalities may be corrected safely and effectively with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase. Rather than dissolving all the offending filler, waiting, and then reinjecting fresh filler weeks or months later, dermatologists may precisely sculpt already injected excess filler by titration with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase to the desired skin contour.”

Other types of hyaluronidase may work in different ways, the study authors noted, and larger doses may be needed to treat longer-lasting types of fillers.

In an accompanying commentary, Derek H. Jones, MD, of Skin Care and Laser Physicians of Beverly Hills, Calif., praised the study, which he wrote, “proves that smaller, less-concentrated doses of hyaluronidase are capable of removing small amounts of HA [hyaluronic acid] without removing the entire implant.”

Dr. Jones added that he uses 10 U of Vitrase (hyaluronidase) for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm that he estimates should be removed. He also uses 5 U of Vitrase for each 0.1 cc of Restylane, and 30 U for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm Voluma.

“When attempting to remove smaller or partial amounts of HA implant,” he added, “I often dilute Vitrase with normal saline to go from 20 U/0.1 cc to 10 U/0.1 cc or less.”

Northwestern University funded the study. Dr. Alam, the lead author, reported various disclosures, and the university disclosed that its clinical trials branch receives various government and corporate grants. The other authors reported no disclosures. Dr. Jones disclosed serving as an investigator, consultant, and/or speaker for Allergan, Merz, and Galderma.

SOURCE: Alam M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0515.

, and in some cases, slightly larger doses may move things along more rapidly, according to the authors of a small split-arm clinical trial.

“These findings offer clinicians a means to modify and fine-tune filler-associated skin contour without resorting to high-dose injections that completely remove all filler from the treatment site,” wrote the authors, led by Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology and chief of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The study, conducted during 2013-2014, analyzed the impact of various small doses of hyaluronidase on two types of fillers that had been administered into the upper inner arms of nine women (seven white, two black; mean age, 46 years). Another participant withdrew because of a fear of needles.

In one arm in each woman, researchers injected four aliquots of Juvéderm Ultra XC (0.4 mL each). Then, at 1, 2, and 3 weeks, they administered 1.5 U, 3.0 U, or 9.0 U hyaluronidase per 0.1 mL or saline control (at a constant volume of 0.1 mL) into each site. In the other arms, researchers performed the same protocol, but with Restylane-L. A 5-point scale was used to rate detectability of each site ranging from 0 (undetectable) and 1 (faintly perceptible) to 4 (“very” perceptible).

A blinded physician visually rated the effects of saline versus hyaluronidase at 4 weeks and found a significant difference between assessments of the hyaluronidase-treated sites and saline control sites at 4 weeks, favoring the hyaluronidase sites for visual detection (mean difference, 1.15; P less than .001) and palpability (mean difference, 1.22; P less than .001). Participant self-assessments at 4 weeks produced similar results for visual detection (mean difference, 0.87; P = .006) and palpability (mean difference, 1.59; P less than .001).

Similar differences favoring hyaluronidase persisted at 4 months.

The researchers also found that 9.0-U treatments of hyaluronidase led to significantly less palpability than 1.5-U treatments at 4 weeks and 4 months. The researchers noticed a larger dose-related difference for hyaluronidase for Restylane-L sites, and they noted that all the filler nodules diminished over time regardless of the study treatment.

“The clinical relevance of these findings is clear,” they concluded. “Minor filler-associated asymmetries, nodules, and textural abnormalities may be corrected safely and effectively with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase. Rather than dissolving all the offending filler, waiting, and then reinjecting fresh filler weeks or months later, dermatologists may precisely sculpt already injected excess filler by titration with low-volume, low-dose hyaluronidase to the desired skin contour.”

Other types of hyaluronidase may work in different ways, the study authors noted, and larger doses may be needed to treat longer-lasting types of fillers.

In an accompanying commentary, Derek H. Jones, MD, of Skin Care and Laser Physicians of Beverly Hills, Calif., praised the study, which he wrote, “proves that smaller, less-concentrated doses of hyaluronidase are capable of removing small amounts of HA [hyaluronic acid] without removing the entire implant.”

Dr. Jones added that he uses 10 U of Vitrase (hyaluronidase) for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm that he estimates should be removed. He also uses 5 U of Vitrase for each 0.1 cc of Restylane, and 30 U for each 0.1 cc of Juvéderm Voluma.

“When attempting to remove smaller or partial amounts of HA implant,” he added, “I often dilute Vitrase with normal saline to go from 20 U/0.1 cc to 10 U/0.1 cc or less.”

Northwestern University funded the study. Dr. Alam, the lead author, reported various disclosures, and the university disclosed that its clinical trials branch receives various government and corporate grants. The other authors reported no disclosures. Dr. Jones disclosed serving as an investigator, consultant, and/or speaker for Allergan, Merz, and Galderma.

SOURCE: Alam M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0515.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Low doses of hyaluronidase can effectively remove unwanted hyaluronic acid filler.

Major finding: At 4 weeks, palpability favored hyaluronidase vs. saline (mean difference, 1.22; P less than .001).

Study details: A split-arm, parallel-group randomized clinical trial of nine women. Arms were given one of two types of filler injections and saline or various doses of hyaluronidase.

Disclosures: Northwestern University funded the study. One author reported various financial disclosures.

Source: Alam M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0515.

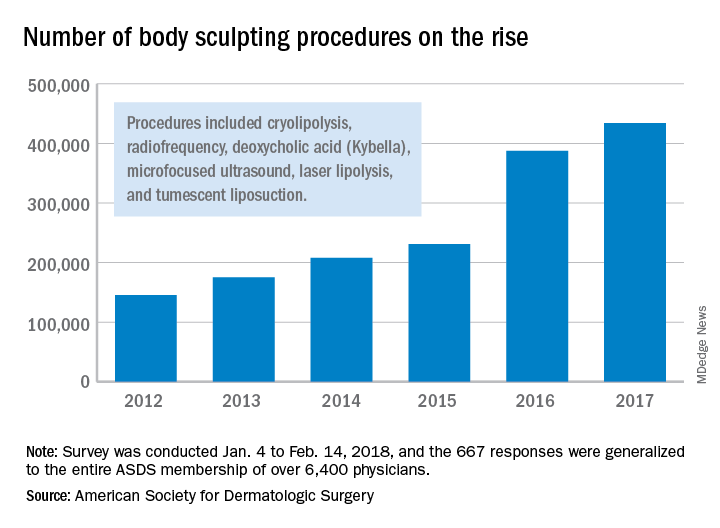

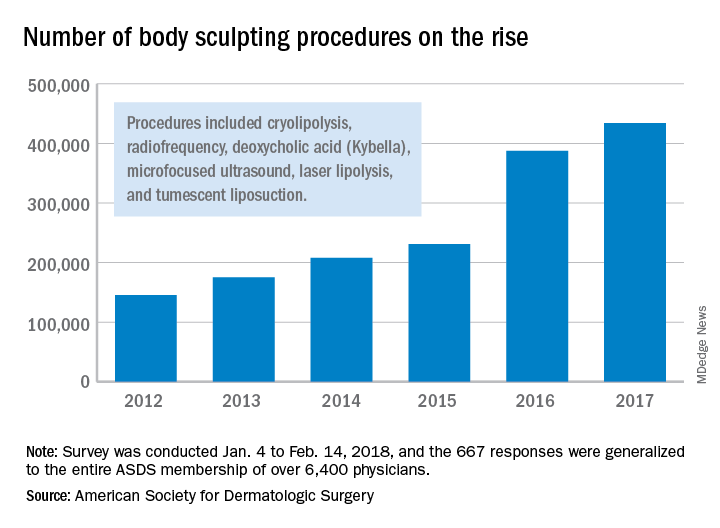

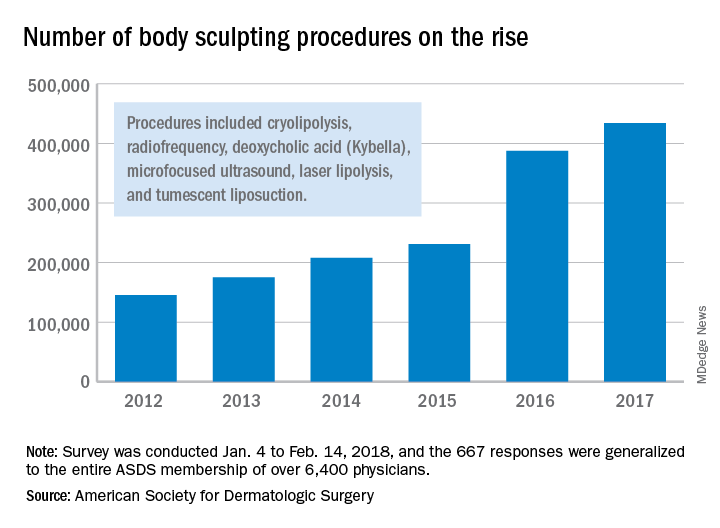

Cryolipolysis leads surge in body sculpting

during 2012-2017, according to a survey from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

A total of 434,000 body sculpting procedures were performed by ASDS members in 2017, compared with 146,000 in 2012, the ASDS reported based on data from 667 survey respondents, which were generalized to the society’s membership of over 6,400 physicians.

“An increase in media coverage and in celebrities acknowledging their procedures are growing awareness among the general public and improving the comfort level of diverse audiences to explore treatments,” ASDS president Lisa Donofrio, MD, said in a written statement. The survey was conducted from Jan. 4 to Feb. 14, 2018.

during 2012-2017, according to a survey from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

A total of 434,000 body sculpting procedures were performed by ASDS members in 2017, compared with 146,000 in 2012, the ASDS reported based on data from 667 survey respondents, which were generalized to the society’s membership of over 6,400 physicians.

“An increase in media coverage and in celebrities acknowledging their procedures are growing awareness among the general public and improving the comfort level of diverse audiences to explore treatments,” ASDS president Lisa Donofrio, MD, said in a written statement. The survey was conducted from Jan. 4 to Feb. 14, 2018.

during 2012-2017, according to a survey from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

A total of 434,000 body sculpting procedures were performed by ASDS members in 2017, compared with 146,000 in 2012, the ASDS reported based on data from 667 survey respondents, which were generalized to the society’s membership of over 6,400 physicians.

“An increase in media coverage and in celebrities acknowledging their procedures are growing awareness among the general public and improving the comfort level of diverse audiences to explore treatments,” ASDS president Lisa Donofrio, MD, said in a written statement. The survey was conducted from Jan. 4 to Feb. 14, 2018.

Sesamol

The protective effects of the antioxidative compound sesamol against radiation were reported as early as 1991.1 The water-soluble lignan sesamol, a natural phenolic compound derived from Sesamum indicum (sesame) seed oil, has since become known as a potent antioxidant with significant anticancer potential.2,3 As a constituent found in food oils such as sesame and sunflower oil, sesamol has been studied for the dietary benefits that it has been said to impart. Sesame oil, in particular, has been used in Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, as well as in folk medicine in Nigeria and other African countries.Data on its antioxidant and chemopreventive properties also have prompted investigations into its potential in the dermatologic realm because sesamol has demonstrated an increasingly wide array of cutaneous applications.

Antibacterial effects

In 2007, Bankole et al. ascertained the synergistic antimicrobial properties of the essential oils and lignans found in the leaf extracts of S. radiatum and S. indicum. Phytochemical screening of methanolic extracts revealed the presence of phenolic compounds such as the potent antioxidants sesamol, sesamolin, and sesamin, as well as carboxylic acids. Methanolic and ethanolic extracts were shown to exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects against all of the pathogens tested except Streptococcus pneumoniae (methanolic extracts) and Staphylococcus aureus (ethanolic extracts). The investigators concluded that their results buttressed long-held traditional claims in multiple regions in Nigeria where consumption of sesame leaf extracts has been known to confer antibacterial effects with effectiveness reported for common skin infections.4

Anticancer activity

Kapadia et al. studied the dietary components resveratrol, sesamol, sesame oil, and sunflower oil in various protocols, including a murine two-stage skin cancer model, for their potential as cancer chemopreventive agents. In this 2002 study, the mouse skin tumor model, sesamol was found to provide a 50% reduction in skin papillomas at 20 weeks after promotion with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate. The researchers concluded that all of the dietary constituents appeared to provide chemopreventive effects.5

In 2010, Ramachandran et al. observed that pretreating human skin dermal fibroblast adult cells with sesamol before irradiation with UVB yielded significant reductions in cytotoxicity, intracellular reactive oxygen species levels, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis. In noting increases in enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant activity in sesamol-pretreated UVB-exposed fibroblasts, the investigators ascribed the apparent protective effects of sesamol to its antioxidant scavenging of reactive oxygen species.6

Seven years later, Bhardwaj et al. evaluated the chemopreventive efficacy of free and encapsulated sesamol in a 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene–induced skin cancer animal model. The investigators found that in both forms sesamol significantly reduced tumor burden and lipid peroxidation while raising antioxidant levels. This resulted in the inhibition of skin tumor development and promotion. Apoptosis in tumor cells also was found to result from the down-regulation of Bcl-2 and stimulation of Bcl-2–associated X protein expression from administration of both free and encapsulated sesamol. Furthermore, the irritant qualities of sesamol were mitigated by encapsulation, which also aided in direct targeting of the skin.2

Potential cosmeceutical applications: Anti-aging and skin-whitening activity

In 2006, Sharma and Kaur demonstrated in mouse skin, through biochemical and histopathologic evaluations, that a topical sesamol formulation was effective in preventing photodamage (such as alterations in skin integrity, lesions, ulcers) from chronic UV exposure. They suggested the merits of further testing and consideration of sesamol as an antiaging agent.7

Almost a decade later, Srisayam et al. conducted a systematic study of the antimelanogenic and skin protective activities of sesamol. They found that sesamol exhibited significant scavenging activity of the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl hydrate radical with an IC50 value less than 14.48 mcm. The antioxidant also suppressed lipid peroxidation (IC50 value of 6.15 mcm), and displayed a whitening effect via mushroom tyrosinase inhibition as well as inhibition of cellular tyrosinase. In noting the potent antioxidant and antityrosinase activity in comparison to the positive control – kojic acid and beta-arbutin – the researchers highlighted the potential cosmeceutical applications of sesamol.8

Baek and Lee showed in 2015 that sesamol potently suppressed melanin biosynthesis by down-regulating tyrosinase activity and regulating gene expression of melanogenesis-related proteins via microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) activity modulation. They concluded that sesamol warrants attention in the cosmetic realm as a new skin-whitening agent.9

Formulation issues

Earlier that year, Geetha et al. confirmed the apoptotic characteristics of sesamol in in vitro antiproliferative and DNA-fragmentation studies in HL60 cell lines. Because of its small size, low molecular weight, and easy permeability, its viability in topical applications is considered minimal. The investigators addressed this issue by preparing sesamol-loaded solid-lipid nanoparticles, which, when applied in a cream base in mice, revealed significant retention in the skin. Its use in in vivo anticancer studies performed on tumor production induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate and initiated by benzo(a)pyrene in mouse epidermis resulted in the normalization of skin cancers.10

More recently, Puglia et al. set out to improve the delivery of the benefits of sesamol to the skin by developing a nanostructured lipid carrier for topical administration. They synthesized two different carrier systems and performed an in vitro percutaneous absorption study in excised human skin to determine antioxidant activity. The carrier systems differed by oil phase: One contained Miglyol 812 (nanostructured lipid carrier–M) and the other contained sesame oil (nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS). Greater encapsulation efficiency was reported when sesame oil was employed as the oil phase, but both products displayed the capacity in vitro to control the rate of sesamol diffusion through the skin, compared with reference preparations. Both formulations also showed the extended antioxidant activity of sesamol, particularly the nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS.3

Conclusion

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014). She also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Sato Y et al. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1991 Jan;111(1):51-8.

2. Bhardwaj R et al. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17(5):726-33.

3. Puglia C et al. Planta Med. 2017 Mar;83(5):398-404.

4. Bankole MA et al. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2007; 4(4): 427-33.

5. Kapadia GJ et al. Pharmacol Res. 2002 Jun;45(6):499-505.

6. Ramachandran S et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010 Dec;302(10):733-44.

7. Sharma S and Kaur IP. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Mar;45(3):200-8.

8. Srisayam M et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2014 Mar-Apr;65(2):69-79.

9. Baek SH and Lee SH. Exp Dermatol. 2015 Oct;24(10):761-6.

10. Geetha T et al. J Drug Target. 2015 Feb;23(2):159-69.

The protective effects of the antioxidative compound sesamol against radiation were reported as early as 1991.1 The water-soluble lignan sesamol, a natural phenolic compound derived from Sesamum indicum (sesame) seed oil, has since become known as a potent antioxidant with significant anticancer potential.2,3 As a constituent found in food oils such as sesame and sunflower oil, sesamol has been studied for the dietary benefits that it has been said to impart. Sesame oil, in particular, has been used in Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, as well as in folk medicine in Nigeria and other African countries.Data on its antioxidant and chemopreventive properties also have prompted investigations into its potential in the dermatologic realm because sesamol has demonstrated an increasingly wide array of cutaneous applications.

Antibacterial effects

In 2007, Bankole et al. ascertained the synergistic antimicrobial properties of the essential oils and lignans found in the leaf extracts of S. radiatum and S. indicum. Phytochemical screening of methanolic extracts revealed the presence of phenolic compounds such as the potent antioxidants sesamol, sesamolin, and sesamin, as well as carboxylic acids. Methanolic and ethanolic extracts were shown to exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects against all of the pathogens tested except Streptococcus pneumoniae (methanolic extracts) and Staphylococcus aureus (ethanolic extracts). The investigators concluded that their results buttressed long-held traditional claims in multiple regions in Nigeria where consumption of sesame leaf extracts has been known to confer antibacterial effects with effectiveness reported for common skin infections.4

Anticancer activity

Kapadia et al. studied the dietary components resveratrol, sesamol, sesame oil, and sunflower oil in various protocols, including a murine two-stage skin cancer model, for their potential as cancer chemopreventive agents. In this 2002 study, the mouse skin tumor model, sesamol was found to provide a 50% reduction in skin papillomas at 20 weeks after promotion with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate. The researchers concluded that all of the dietary constituents appeared to provide chemopreventive effects.5

In 2010, Ramachandran et al. observed that pretreating human skin dermal fibroblast adult cells with sesamol before irradiation with UVB yielded significant reductions in cytotoxicity, intracellular reactive oxygen species levels, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis. In noting increases in enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant activity in sesamol-pretreated UVB-exposed fibroblasts, the investigators ascribed the apparent protective effects of sesamol to its antioxidant scavenging of reactive oxygen species.6

Seven years later, Bhardwaj et al. evaluated the chemopreventive efficacy of free and encapsulated sesamol in a 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene–induced skin cancer animal model. The investigators found that in both forms sesamol significantly reduced tumor burden and lipid peroxidation while raising antioxidant levels. This resulted in the inhibition of skin tumor development and promotion. Apoptosis in tumor cells also was found to result from the down-regulation of Bcl-2 and stimulation of Bcl-2–associated X protein expression from administration of both free and encapsulated sesamol. Furthermore, the irritant qualities of sesamol were mitigated by encapsulation, which also aided in direct targeting of the skin.2

Potential cosmeceutical applications: Anti-aging and skin-whitening activity

In 2006, Sharma and Kaur demonstrated in mouse skin, through biochemical and histopathologic evaluations, that a topical sesamol formulation was effective in preventing photodamage (such as alterations in skin integrity, lesions, ulcers) from chronic UV exposure. They suggested the merits of further testing and consideration of sesamol as an antiaging agent.7

Almost a decade later, Srisayam et al. conducted a systematic study of the antimelanogenic and skin protective activities of sesamol. They found that sesamol exhibited significant scavenging activity of the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl hydrate radical with an IC50 value less than 14.48 mcm. The antioxidant also suppressed lipid peroxidation (IC50 value of 6.15 mcm), and displayed a whitening effect via mushroom tyrosinase inhibition as well as inhibition of cellular tyrosinase. In noting the potent antioxidant and antityrosinase activity in comparison to the positive control – kojic acid and beta-arbutin – the researchers highlighted the potential cosmeceutical applications of sesamol.8

Baek and Lee showed in 2015 that sesamol potently suppressed melanin biosynthesis by down-regulating tyrosinase activity and regulating gene expression of melanogenesis-related proteins via microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) activity modulation. They concluded that sesamol warrants attention in the cosmetic realm as a new skin-whitening agent.9

Formulation issues

Earlier that year, Geetha et al. confirmed the apoptotic characteristics of sesamol in in vitro antiproliferative and DNA-fragmentation studies in HL60 cell lines. Because of its small size, low molecular weight, and easy permeability, its viability in topical applications is considered minimal. The investigators addressed this issue by preparing sesamol-loaded solid-lipid nanoparticles, which, when applied in a cream base in mice, revealed significant retention in the skin. Its use in in vivo anticancer studies performed on tumor production induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate and initiated by benzo(a)pyrene in mouse epidermis resulted in the normalization of skin cancers.10

More recently, Puglia et al. set out to improve the delivery of the benefits of sesamol to the skin by developing a nanostructured lipid carrier for topical administration. They synthesized two different carrier systems and performed an in vitro percutaneous absorption study in excised human skin to determine antioxidant activity. The carrier systems differed by oil phase: One contained Miglyol 812 (nanostructured lipid carrier–M) and the other contained sesame oil (nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS). Greater encapsulation efficiency was reported when sesame oil was employed as the oil phase, but both products displayed the capacity in vitro to control the rate of sesamol diffusion through the skin, compared with reference preparations. Both formulations also showed the extended antioxidant activity of sesamol, particularly the nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS.3

Conclusion

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014). She also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Sato Y et al. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1991 Jan;111(1):51-8.

2. Bhardwaj R et al. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17(5):726-33.

3. Puglia C et al. Planta Med. 2017 Mar;83(5):398-404.

4. Bankole MA et al. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2007; 4(4): 427-33.

5. Kapadia GJ et al. Pharmacol Res. 2002 Jun;45(6):499-505.

6. Ramachandran S et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010 Dec;302(10):733-44.

7. Sharma S and Kaur IP. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Mar;45(3):200-8.

8. Srisayam M et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2014 Mar-Apr;65(2):69-79.

9. Baek SH and Lee SH. Exp Dermatol. 2015 Oct;24(10):761-6.

10. Geetha T et al. J Drug Target. 2015 Feb;23(2):159-69.

The protective effects of the antioxidative compound sesamol against radiation were reported as early as 1991.1 The water-soluble lignan sesamol, a natural phenolic compound derived from Sesamum indicum (sesame) seed oil, has since become known as a potent antioxidant with significant anticancer potential.2,3 As a constituent found in food oils such as sesame and sunflower oil, sesamol has been studied for the dietary benefits that it has been said to impart. Sesame oil, in particular, has been used in Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, as well as in folk medicine in Nigeria and other African countries.Data on its antioxidant and chemopreventive properties also have prompted investigations into its potential in the dermatologic realm because sesamol has demonstrated an increasingly wide array of cutaneous applications.

Antibacterial effects

In 2007, Bankole et al. ascertained the synergistic antimicrobial properties of the essential oils and lignans found in the leaf extracts of S. radiatum and S. indicum. Phytochemical screening of methanolic extracts revealed the presence of phenolic compounds such as the potent antioxidants sesamol, sesamolin, and sesamin, as well as carboxylic acids. Methanolic and ethanolic extracts were shown to exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects against all of the pathogens tested except Streptococcus pneumoniae (methanolic extracts) and Staphylococcus aureus (ethanolic extracts). The investigators concluded that their results buttressed long-held traditional claims in multiple regions in Nigeria where consumption of sesame leaf extracts has been known to confer antibacterial effects with effectiveness reported for common skin infections.4

Anticancer activity

Kapadia et al. studied the dietary components resveratrol, sesamol, sesame oil, and sunflower oil in various protocols, including a murine two-stage skin cancer model, for their potential as cancer chemopreventive agents. In this 2002 study, the mouse skin tumor model, sesamol was found to provide a 50% reduction in skin papillomas at 20 weeks after promotion with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate. The researchers concluded that all of the dietary constituents appeared to provide chemopreventive effects.5

In 2010, Ramachandran et al. observed that pretreating human skin dermal fibroblast adult cells with sesamol before irradiation with UVB yielded significant reductions in cytotoxicity, intracellular reactive oxygen species levels, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis. In noting increases in enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant activity in sesamol-pretreated UVB-exposed fibroblasts, the investigators ascribed the apparent protective effects of sesamol to its antioxidant scavenging of reactive oxygen species.6

Seven years later, Bhardwaj et al. evaluated the chemopreventive efficacy of free and encapsulated sesamol in a 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene–induced skin cancer animal model. The investigators found that in both forms sesamol significantly reduced tumor burden and lipid peroxidation while raising antioxidant levels. This resulted in the inhibition of skin tumor development and promotion. Apoptosis in tumor cells also was found to result from the down-regulation of Bcl-2 and stimulation of Bcl-2–associated X protein expression from administration of both free and encapsulated sesamol. Furthermore, the irritant qualities of sesamol were mitigated by encapsulation, which also aided in direct targeting of the skin.2

Potential cosmeceutical applications: Anti-aging and skin-whitening activity

In 2006, Sharma and Kaur demonstrated in mouse skin, through biochemical and histopathologic evaluations, that a topical sesamol formulation was effective in preventing photodamage (such as alterations in skin integrity, lesions, ulcers) from chronic UV exposure. They suggested the merits of further testing and consideration of sesamol as an antiaging agent.7

Almost a decade later, Srisayam et al. conducted a systematic study of the antimelanogenic and skin protective activities of sesamol. They found that sesamol exhibited significant scavenging activity of the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl hydrate radical with an IC50 value less than 14.48 mcm. The antioxidant also suppressed lipid peroxidation (IC50 value of 6.15 mcm), and displayed a whitening effect via mushroom tyrosinase inhibition as well as inhibition of cellular tyrosinase. In noting the potent antioxidant and antityrosinase activity in comparison to the positive control – kojic acid and beta-arbutin – the researchers highlighted the potential cosmeceutical applications of sesamol.8

Baek and Lee showed in 2015 that sesamol potently suppressed melanin biosynthesis by down-regulating tyrosinase activity and regulating gene expression of melanogenesis-related proteins via microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) activity modulation. They concluded that sesamol warrants attention in the cosmetic realm as a new skin-whitening agent.9

Formulation issues

Earlier that year, Geetha et al. confirmed the apoptotic characteristics of sesamol in in vitro antiproliferative and DNA-fragmentation studies in HL60 cell lines. Because of its small size, low molecular weight, and easy permeability, its viability in topical applications is considered minimal. The investigators addressed this issue by preparing sesamol-loaded solid-lipid nanoparticles, which, when applied in a cream base in mice, revealed significant retention in the skin. Its use in in vivo anticancer studies performed on tumor production induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate and initiated by benzo(a)pyrene in mouse epidermis resulted in the normalization of skin cancers.10

More recently, Puglia et al. set out to improve the delivery of the benefits of sesamol to the skin by developing a nanostructured lipid carrier for topical administration. They synthesized two different carrier systems and performed an in vitro percutaneous absorption study in excised human skin to determine antioxidant activity. The carrier systems differed by oil phase: One contained Miglyol 812 (nanostructured lipid carrier–M) and the other contained sesame oil (nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS). Greater encapsulation efficiency was reported when sesame oil was employed as the oil phase, but both products displayed the capacity in vitro to control the rate of sesamol diffusion through the skin, compared with reference preparations. Both formulations also showed the extended antioxidant activity of sesamol, particularly the nanostructured lipid carrier–PLUS.3

Conclusion

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014). She also wrote a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC.

References

1. Sato Y et al. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1991 Jan;111(1):51-8.

2. Bhardwaj R et al. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17(5):726-33.

3. Puglia C et al. Planta Med. 2017 Mar;83(5):398-404.

4. Bankole MA et al. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2007; 4(4): 427-33.

5. Kapadia GJ et al. Pharmacol Res. 2002 Jun;45(6):499-505.

6. Ramachandran S et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010 Dec;302(10):733-44.

7. Sharma S and Kaur IP. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Mar;45(3):200-8.

8. Srisayam M et al. J Cosmet Sci. 2014 Mar-Apr;65(2):69-79.

9. Baek SH and Lee SH. Exp Dermatol. 2015 Oct;24(10):761-6.

10. Geetha T et al. J Drug Target. 2015 Feb;23(2):159-69.

Tattoos: From Ancient Practice to Modern Treatment Dilemma

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

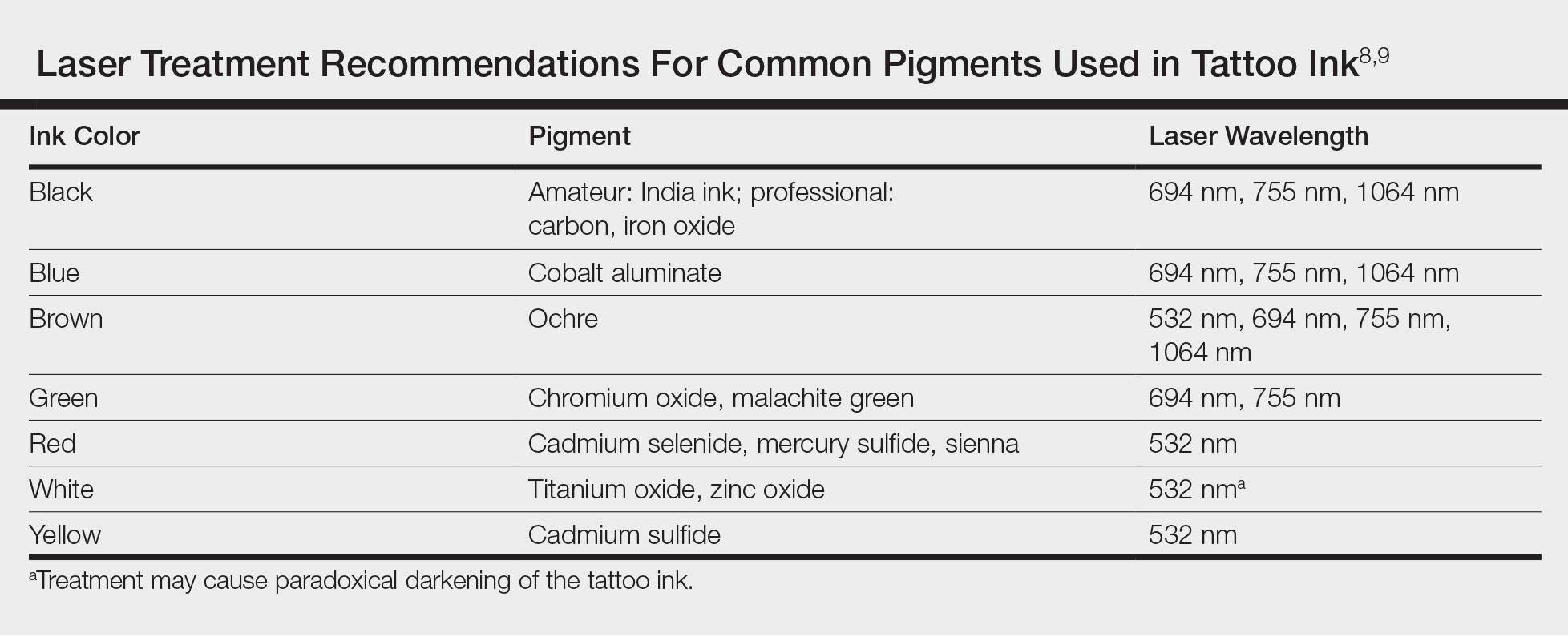

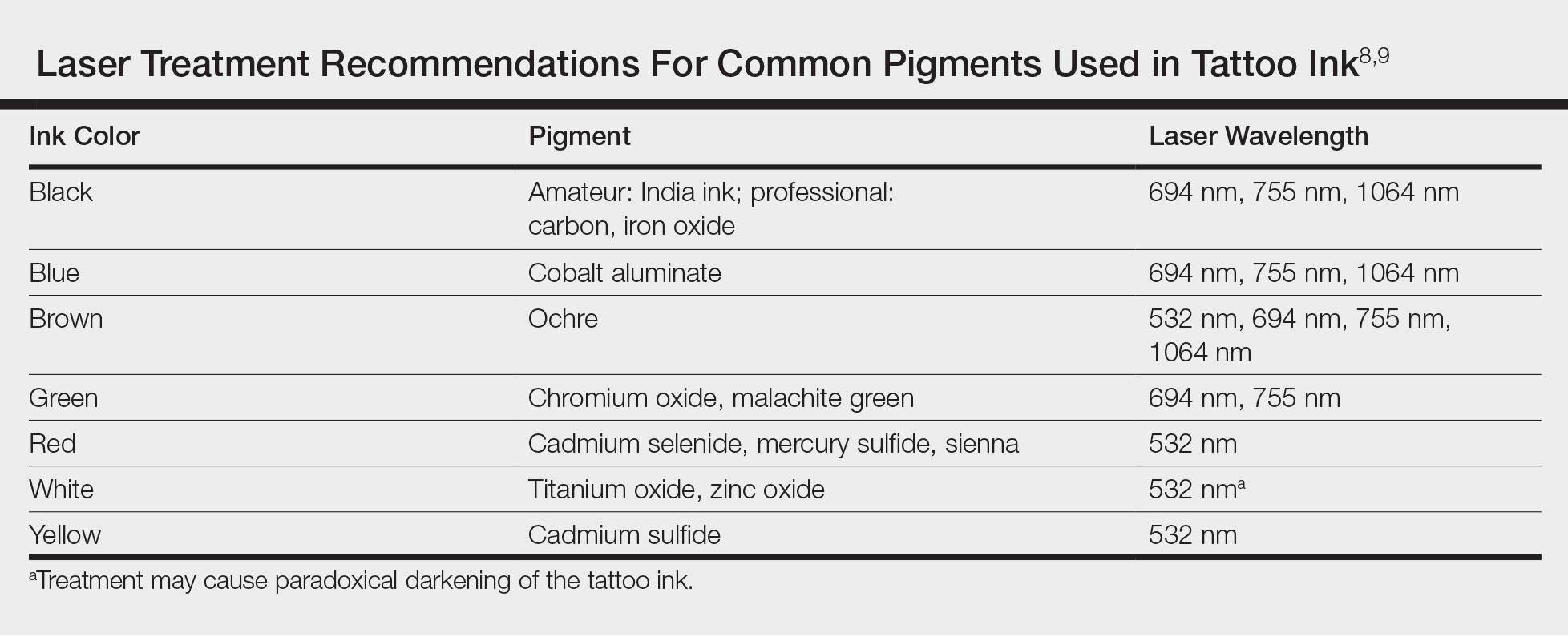

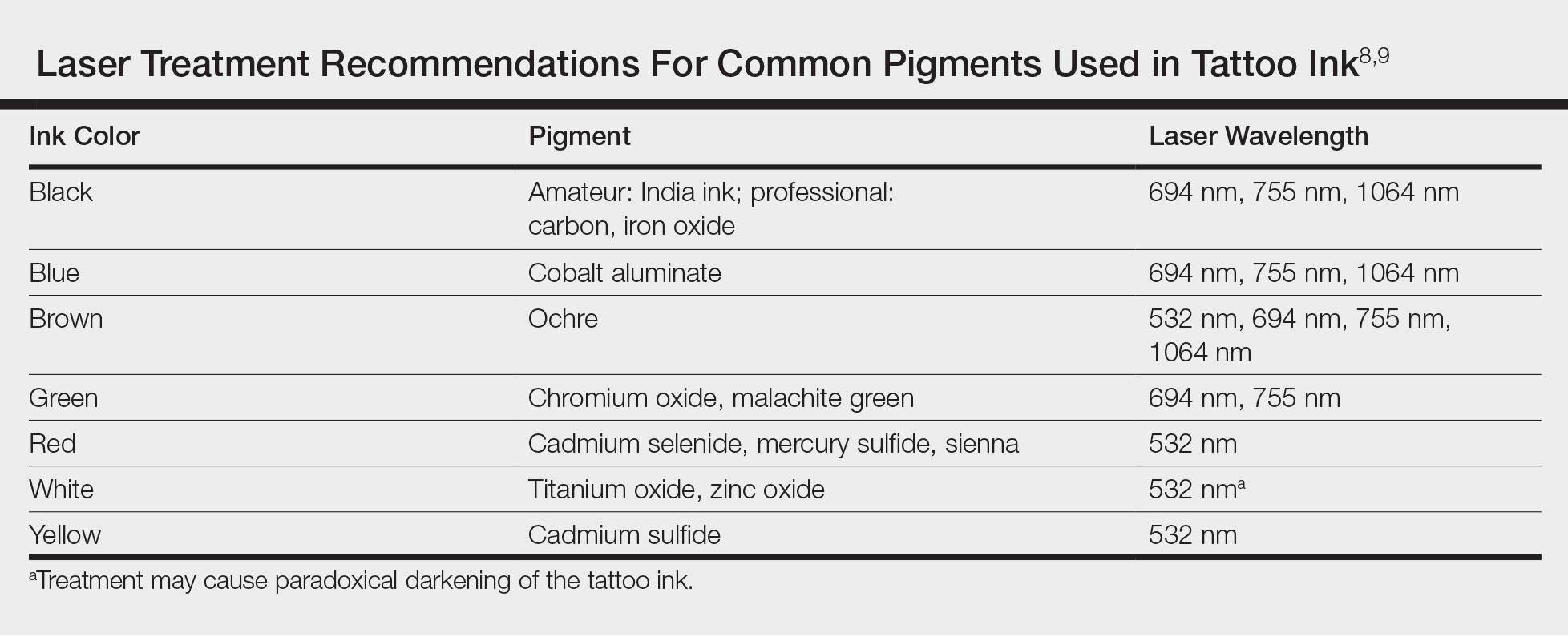

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

As dermatologists, we possess a vast knowledge of the epidermis. Some patients may choose to use the epidermis as a canvas for their art in the form of tattoos; however, tattoos can complicate dermatology visits in a myriad of ways. From patients seeking tattoo removal (a complicated task even with the most advanced laser treatments) to those whose native skin is obscured by a tattoo during melanoma screening, it is no wonder that many dermatologists become frustrated at the very mention of the word tattoo.

Tattoos have a long and complicated history entrenched in class divisions, gender identity, and culture. Although its origins are not well documented, many researchers believe that tattooing began in Egypt as early as 4000 BCE.1 From there, the practice spread east into South Asia and west to the British Isles and Scotland. The Iberians in the British Isles, the Picts in Scotland, the Gauls in Western Europe, and the Teutons in Germany all practiced tattooing, and the Romans were known to use tattooing to mark convicts and slaves.1 By 787 AD, tattooing was prevalent enough to warrant an official ban by Pope Hadrian I at the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea.2 The growing power of Christianity most likely contributed to the elimination of tattooing in the West, although many soldiers who fought in the Crusades received tattoos during their travels.3

Despite the long history of tattoos in both the East and West, Captain James Cook often is credited with discovering tattooing in the eighteenth century during his explorations in the Pacific.4 In Tahiti in 1769 and Hawaii in 1778, Cook encountered heavily tattooed populations who deposited dye into the skin by tapping sharpened instruments.3 These Polynesian tattoos, which were associated with healing and protective powers, often depicted genealogies and were composed of images of lines, stars, geometric designs, animals, and humans. Explorers in Polynesia who came after Cook noted that tattoo designs began to include rifles, cannons, and dates of chief’s deaths—an indication of the cultural exchange that occurred between Cook’s crew and the natives.3 The first tattooed peoples were displayed in the United States at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876.2 Later, at the 1901 World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, the first full “freak show” emerged, and tattooed “natives” were displayed.5 Since they were introduced in the West, tattoos have been associated with an element of the exotic in the United States.

Acknowledged by many to be the first professional tattooist in the United States, Martin Hildebrandt opened his shop in New York City, New York, in 1846.2 Initially, only sailors and soldiers were tattooed, which contributed to the concept of the so-called “tattooed serviceman.”5 However, after the Spanish-American War, tattoos became a fad among the high society in Europe. Tattooing at this time was still performed through the ancient Polynesian tapping method, making it both time-consuming and expensive. Tattoos generally were always placed in a private location, leading to popular speculation at the time about whom in the aristocracy possessed a tattoo, with some even speculating that Queen Victoria may have had a tattoo.1 However, this brief trend among the aristocracy came to an end when Samuel O’Reilly, an American tattoo artist, patented the first electric tattooing machine in 1891.6 His invention made tattooing faster, cheaper, and less painful, thereby making tattooing available to a much wider audience. In the United States, men in the military often were tattooed, especially during World Wars I and II, when patriotic themes and tattoos of important women in their lives (eg, the word Mom, the name of a sweetheart) became popular.

It is a popular belief that a tattoo renaissance occurred in the United States in the 1970s, sparked by an influx of Indonesian and Asian artistic styles. Today, tattoos are ubiquitous. A 2012 poll showed that 21% of adults in the United States have a tattoo.7 There are now 4 main types of tattoos: cosmetic (eg, permanent makeup), traumatic (eg, injury on asphalt), medical (eg, to mark radiation sites), and decorative—either amateur (often done by hand) or professional (done in tattoo parlors with electric tattooing needles).8

Laser Tattoo Removal

Today tattoos are easy and relatively cheap to get, and for most people they are not regarded as an important cultural milestone like they were in early Polynesian culture. As a result, dermatologists often may encounter patients seeking to have these permanent designs removed from their skin. Previously, tattoo removal was attempted using destructive processes such as scarification and cryotherapy and generally resulted in poor cosmetics outcomes. Today, lasers are at the forefront of tattoo removal. Traditional lasers use pulse durations in the nanosecond range, with newer generation lasers in the picosecond range delivering much shorter pulse durations, effectively delivering the same level of energy over less time. It is important to select the correct laser for optimal destruction of various tattoo ink colors (Table).8,9

Controversy persists as to whether tattoo pigment destruction by lasers is caused by thermal or acoustic damage.10 It may be a combination of both, with rapid heating of the particles leading to a local shockwave as the energy collapses.11 The goal of tattoo removal is to create smaller granules of pigment that can be taken up by the patient’s lymphatic system. The largest granule that can be taken up by the lymphatic system is 0.4 μm.10

In laser treatment of any skin condition, the laser energy is delivered in a pulse duration that should be less than the thermal relaxation time of the chromophores (water, melanin, hemoglobin, or tattoo pigment are the main targets within the skin).12 Most tattoo chromophores are 30 nm to 300 nm, with a thermal relaxation time of less than 10 nanoseconds.10,12 As the number of treatments progresses, laser settings should be adjusted for smaller ink particles. Patients should be warned about pain, side effects, and the need for multiple treatments. Common side effects of laser tattoo removal include purpura, pinpoint bleeding, erythema, edema, crusting, and blistering.8

After laser treatment, cytoplasmic water in the cell is converted into steam leading to cavitation of the lysosome, which presents as whitening of the skin. The whitening causes optical scatter, thereby preventing immediate retreatment of the area.11 The R20 laser tattoo removal method discussed by Kossida et al,13 advises practitioners to wait 20 minutes between treatments to allow the air bubbles from the conversion of water to steam to disappear. Kossida et al13 demonstrated more effective removal in tattoos that were treated with this method compared to standard treatment. The recognition that trapped air bubbles delay multiple treatment cycles has led to the experimental use of perfluorodecalin, a fluorocarbon liquid capable of dissolving the air bubbles, for immediate retreatment.14 By dissolving the trapped air and eliminating the white color, multiple treatments can be completed during 1 session.

Risks of Laser Tattoo Removal

It is important to emphasize that there are potential risks associated with laser treatment for tattoo removal, many of which we are only just beginning to understand. Common side effects of laser treatment for tattoo removal include blisters, pain, bleeding, hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation; however, there also are rare potential risks. Tattoo ink can paradoxically darken when it contains metals such as titanium or zinc, as often is found in tan or white inks.15 The laser energy causes a shift of the metal from an oxidized to a reduced state, leading to a darker rather than lighter tattoo upon application of the laser. There also have been documented cases of intraprocedural anaphylaxis, delayed urticaria, as well as generalized eczematous reactions.16-18 In these cases, the patients had never experienced any allergic symptoms prior to the laser tattoo removal procedure.

Additionally, patients with active allergy to the pigments used in tattoo ink provide a therapeutic dilemma, as laser treatment may potentially systematize the tattoo ink, leading to a more widespread allergic reaction. A case of a generalized eczematous reaction after carbon dioxide laser therapy in a patient with documented tattoo allergy has been reported.19 More research is needed to fully understand the nature of immediate as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions associated with laser tattoo removal.

Final Thoughts

With thousands of years of established traditions, it is unlikely that tattooing will go away anytime soon. Fortunately, lasers are providing us with an effective and safe method of removal.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

- Caplan J, ed. Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. Bodies of Inscription: Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2000.

- DeMello M. “Not just for bikers anymore”: popular representations of american tattooing. J Popular Culture. 1995;29:37-52.

- Anastasia DJM. Living marked: tattooed women and perceptions of beauty and femininity. In: Segal MT, ed. Interactions and Intersections of Gendered Bodies at Work, at Home, and at Play. Bingly, UK: Emerald; 2010.

- Mifflin M. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: June Books; 1997.

- Atkinson M. Pretty in ink: conformity, resistance, and negotiation in women’s tattooing. Sex Roles. 2002;47:219-235.

- Braverman S. One in five US adults now has a tattoo. Harris Poll website. https://theharrispoll.com/new-york-n-y-february-23-2012-there-is-a-lot-of-culture-and-lore-associated-with-tattoos-from-ancient-art-to-modern-expressionism-and-there-are-many-reasons-people-choose-to-get-or-not-get-p/. Published February 23, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- Ho SG, Goh CL. Laser tattoo removal: a clinical update. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:9-15.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24.

- Shah SD, Aurangabadkar SJ. Newer trends in laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:25-29.

- Hsu VM, Aldahan AS, Mlacker S, et al. The picosecond laser for tattoo removal. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31:1733-1737.

- Kossida T, Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, et al. Optimal tattoo removal in a single laser session based on the method of repeated exposures.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:271-277.

- Biesman BS, O’Neil MP, Costner C. Rapid, high-fluence multipass Q-switched laser treatment of tattoos with a transparent perfluorodecalin-infused patch: a pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:613-618.

- Bernstein EF. Laser tattoo removal. Semin Plast Surg. 2007;21:175-192.

- Wilken R, Ho D, Petukhova T, et al. Intraoperative localized urticarial reaction during Q-switched Nd:YAG laser tattoo removal. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:303-306.

- Hibler BP, Rossi AM. A case of delayed anaphylaxis after laser tattoo removal. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:80-81.

- Bernstein EF. A widespread allergic reaction to black tattoo ink caused by laser treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:180-182.

- Meesters AA, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Generalized eczematous reaction after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy for tattoo allergy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:456-458.

Collagen drinks – do they really work?

The question is, do they really do anything? Previously, most collagen supplements in the beauty industry came in the form of a topical cream or an injectable, with collagen being the main filler of choice before hyaluronic acid fillers became available. Today, collagen supplementation in the form of oral pills and drinks is rampant. These drinks and “vitamins” are purported to improve skin and provide a more youthful appearance, both from an immediate and preventative standpoint. Some of the drinks come from companies in Japan and beyond. According to market forecasts, the collagen supplement industry is anticipated to be worth $6.63 billion by 2025, up from $3.71 billion in 2016. An email advertisement this month from NewBeauty magazine claims one brand of collagen supplementation “with grape seed extract [as] an effective collagen drink for the skin.” Each 1.7 oz. bottle contains 13,000 mg of marine hydrolyzed collagen with six antiaging ingredients that – the ad claims – will help visibly transform your skin to a fuller, firmer, younger look in as soon as 21 days.

Diet absolutely plays a role in our overall health and skin appearance. But can these concentrated collagen drinks provide an increased benefit?

We know from prior experience with injecting collagen in the lips – namely from bovine (such as Zyderm and Zyplast) or human-derived (such as Cosmoderm and CosmoPlast) sources – that it provided beautiful and often natural-appearing results, which, however, did not last. If longevity is an issue with collagen injections, assuming proper absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and subsequent integration into skin, how long should we expect the results from drinking collagen to last in skin, if any? If it does work and is something that improves skin when used on a continuous basis, is there an endpoint at which the benefit is maximized or where an excess of collagen could be detrimental?

Collagen disorders are those where there is inflammation or deficiency in collagen. Could supplementation improve these diseases? Or could supplementation exacerbate or bring on these disorders if consumed in excess? In collagen vascular diseases, such as scleroderma, where apparent autoimmune inflammation of collagen occurs, would supplementation exacerbate the disease by bringing about more collagen to attack, or would it improve the condition by providing new collagen where there may be a defect? Would it help in conditions of collagen deficiency, such as osteogenesis imperfecta?

Many questions about collagen drinks and supplementation remain to be answered. Photoprotection from an early age and a healthy diet that supports production of our bodies’ own natural collagen are the best measures for skin health. With the surplus of collagen drinks and supplements now on the market, objective studies should be conducted and are warranted to answer these question for ourselves and our patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

The question is, do they really do anything? Previously, most collagen supplements in the beauty industry came in the form of a topical cream or an injectable, with collagen being the main filler of choice before hyaluronic acid fillers became available. Today, collagen supplementation in the form of oral pills and drinks is rampant. These drinks and “vitamins” are purported to improve skin and provide a more youthful appearance, both from an immediate and preventative standpoint. Some of the drinks come from companies in Japan and beyond. According to market forecasts, the collagen supplement industry is anticipated to be worth $6.63 billion by 2025, up from $3.71 billion in 2016. An email advertisement this month from NewBeauty magazine claims one brand of collagen supplementation “with grape seed extract [as] an effective collagen drink for the skin.” Each 1.7 oz. bottle contains 13,000 mg of marine hydrolyzed collagen with six antiaging ingredients that – the ad claims – will help visibly transform your skin to a fuller, firmer, younger look in as soon as 21 days.

Diet absolutely plays a role in our overall health and skin appearance. But can these concentrated collagen drinks provide an increased benefit?